Sep 13, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 2

Matthew Peck, Diana M. Doumas, Aida Midgett

Researchers have utilized the Bystander Intervention Model to conceptualize bullying bystander behavior. The five-step model includes Notice the Event, Interpret the Event as an Emergency, Accept Responsibility, Know How to Act, and Decision to Intervene. The purpose of this study was to examine outcomes of an evidence-based bystander training within the context of the Bystander Intervention Model among middle school students (N = 79). We used a quasi-experimental design to examine differences in outcomes between bystanders and non-bystanders. We also assessed which of the steps were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior. Results indicated a significant increase in Know How to Act for both groups. In contrast, we found increases in Notice the Event, Decision to Intervene, and defending behavior among bystanders only. Finally, Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior. We discuss implications of these findings for counselors.

Keywords: Bystander Intervention Model, bullying, bystander training, defending behavior, middle school

School bullying is a significant problem in the United States, with one out of four students reporting being a target of bullying (U.S. Department of Education, 2019). Bullying is defined as any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths, who are not siblings or currently dating, that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance, and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). Bullying peaks in middle school, with 28% of middle school students reporting being a target of school bullying (CDC, 2020). According to a meta-analysis examining consequences of bullying victimization, among middle school students, targets of bullying reported a wide range of socio-emotional consequences, including anxiety, post-traumatic stress, depressive symptoms, poor mental and general health, non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Moore et al., 2017). Researchers have also established mental health risks associated with witnessing bullying among middle school students, including anxiety and depressive symptoms (Doumas & Midgett, 2021; Midgett & Doumas, 2019).

The Role of Bystanders

The majority of students (80%) have reported observing bullying as a bystander (Wu et al., 2016). A bystander is a student who witnesses a bullying situation but is not the target or the perpetrator (Twemlow et al., 2004). Bystanders can respond to bullying in several ways, including encouraging the bully by directly acting as “assistants” or indirectly acting as “reinforcers,” walking away from bullying situations acting as “outsiders,” or attempting to intervene to help the target by acting as “defenders” (Salmivalli et al., 1996). As such, bystanders play an important role in inhibiting or exacerbating bullying situations. Although most students intentionally or unintentionally reinforce bullying by acting as “assistants,” “reinforcers,” or “outsiders” (Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004), a single high-status student or group of students acting as “defenders” can shift attention and power away from the perpetrator (Salmivalli et al., 2011), thereby discontinuing reinforcement, modeling prosocial behavior, and providing social support for targets. Thus, there is a need to train bystanders to intervene to both reduce bullying and buffer both bystanders and targets from the negative consequences associated with witnessing bullying.

Researchers have found that mobilizing bystanders to intervene to stop bullying is an important part of bullying prevention (Polanin et al., 2012). Bullying decreases when bystanders intervene as “defenders” (Salmivalli et al., 2011); however, many students reported they lack the skills to intervene (Bauman et al., 2020) and only 20% reported using defending behavior when they witness bullying (Salmivalli et al., 2005). Researchers investigating bullying bystander behavior have identified factors associated with defending targets, including perceived pressure to intervene (Porter & Smith-Adcock, 2016), basic moral sensitivity to bullying (Thornberg & Jungert, 2013), self-efficacy (Thornberg & Jungert, 2013; van der Ploeg et al., 2017), and empathy (van der Ploeg et al., 2017). However, these studies have focused primarily on one or two specific factors in relation to defending, rather than the process that leads to defending behavior. Because bullying involves many interacting factors, a comprehensive model is needed to understand the complex social behavior of bystander intervention in bullying.

The Bystander Intervention Model

The Bystander Intervention Model (Latané & Darley, 1970) provides a conceptual framework of necessary conditions for bystanders to intervene to help targets of bullying. This model outlines five sequential steps that a bystander must undergo in order to take action: (a) notice the event, (b) interpret the event as an emergency that requires help, (c) accept responsibility for intervening, (d) know how to intervene or provide help, and (e) implement intervention decisions. Nickerson and colleagues (2014) developed a measure, the Bystander Intervention Model in Bullying Questionnaire, as a way to assess the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model in bullying and sexual harassment situations among high school students. Results of structural equation modeling analyses revealed a good model fit, with engagement in each step of the Bystander Intervention Model being influenced by engagement in the previous step, providing a measurement model that can inform bullying intervention efforts. Researchers have also examined an adapted version of the Bystander Intervention Model in Bullying Questionnaire for middle school students, with confirmatory factor analysis supporting the five-step model and demonstrating positive correlations between engagement in each step of the Bystander Intervention Model and defending behavior in bullying situations (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). Applying the Bystander Intervention Model to school-based bullying prevention programs can inform program development and evaluation, with the goal of helping counselors understand how to equip students with skills to engage in all steps of the model, enhancing program outcomes through an increase in defending behavior. To date, however, no researchers have examined bystander training within the context of the Bystander Intervention Model.

The STAC Intervention

STAC (Midgett et al., 2015), which stands for four bystander intervention strategies—Stealing the Show, Turning It Over, Accompanying Others, and Coaching Compassion—is a brief bullying bystander intervention. The program is designed to provide education about bullying, including the definition of bullying and its negative associated consequences; emphasize the importance of intervening in bullying situations; and teach students prosocial skills they can use to intervene as a “defender” when they witness bullying. As a school-based program, STAC was developed to be delivered by school counselors during classroom lessons (Midgett et al., 2015). Research indicates STAC is effective in reducing bullying victimization (Moran et al., 2019) and bullying perpetration (Midgett et al., 2020; Moran et al., 2019) among middle school students. Additionally, researchers have found that middle school students trained in the STAC program reported a decrease in depressive symptoms (Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett et al., 2020), social anxiety (Midgett & Doumas, 2020), and passive suicide ideation (Midgett et al., 2020), while also experiencing a positive sense of self after implementing the STAC strategies (Midgett, Moody, et al., 2017).

Alignment Between the Bystander Intervention Model and the STAC Intervention

The STAC intervention includes didactic and experiential components that are aligned with the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model. First, the facilitators of the STAC program provide education about bullying, what it is and what it is not, and the negative associated consequences of bullying. This information can promote student engagement in the first two steps of the Bystander Intervention Model (i.e., Notice the Event and Interpret the Event as an Emergency). Next, facilitators of the STAC program emphasize the importance of intervening in bullying situations, which can promote student engagement in the third step of the Bystander Intervention Model (i.e., Accept Responsibility). Finally, facilitators of the STAC program train students to use prosocial skills they can use as bystanders to intervene as a “defender” when they witness bullying. The program also includes skills practice for strategy implementation through role-play activities and booster sessions. Skills training and practice are aligned with the last two steps of the Bystander Intervention Model (i.e., Know How to Intervene and Decision to Intervene). Although research indicates that middle school students trained in the STAC program report increases in knowledge and confidence (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett, Doumas, et al., 2017; Moran et al., 2019) and use of the STAC strategies post-training (Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Moran et al., 2019), to date, no research has examined the impact of the STAC intervention on student engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model or how engagement in the five steps is related to post–STAC training defending behavior.

The Present Study

The purpose of this study is to expand the literature by examining changes in engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model among middle school students. First, using a quasi-experimental design, we aim to examine changes in engagement between bystanders and non-bystanders. We also aim to assess which of the five steps are associated with post-training defending behavior. Researchers have demonstrated that each of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model correlates with defending behavior among middle school students (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). To date, however, no study has examined if bystander training increases engagement in the five steps of the model and if the five steps are related to defending behavior after bystander training. The STAC bystander intervention teaches bystanders to act as defenders by providing education about bullying and equipping students with the knowledge and skills to intervene in bullying situations (Midgett et al., 2015). To date, however, no researchers have examined the impact of the STAC intervention on student engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model or how engagement in the five steps is related to defending behavior after bystander training. To address this gap, we used a quasi-experimental design to answer the following research questions:

Research Question 1: Are there differences in student engagement in the five steps of the

Bystander Intervention Model from baseline (T1) to the 6-week

follow-up (T2) between bystanders and non-bystanders?

Research Question 2: Is there a difference in defending behavior from baseline (T1) to the

6-week follow-up (T2) between bystanders and non-bystanders?

Research Question 3: Engagement in which of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention

Model uniquely predicts defending behavior at the 6-week follow-up (T2)?

Methods

Participants

The sampling frame for recruitment included all students in grades 6–8 at a single private school in the Northwest. The school had a total enrollment of 362 students in grades K–8, with a student body comprised of 80% of students identifying as White, 14% Hispanic, 3% Two or More Races, 1% Asian American, 1% Black/African American, and < 1% Native American or Native Hawaiian. The researchers invited all students in grades 6–8 to participate (N = 127). Inclusion criteria included being enrolled in sixth, seventh, or eighth grade; speaking and reading English; and having parental consent and student assent to participate. Exclusion criteria included inability to speak or read English and not having parental consent or not assenting to participate. Of the 127 students invited, 90 (70.9%) parents/guardians provided informed consent and 87 students (68.5%) assented to participate; 79 of those students (90.8%) completed the 6-week (T2) follow-up assessment. Among participants, 62.1% self-identified as female and 37.9% self-identified as male. Participant age ranged from 11–14 years (M = 12.22 and SD = 0.92), with reported race/ethnicity of 63.3% White, 8.9% Hispanic, 2.5% Black/African American, 3.8% Asian American, 15.2% Two or More Races, and 6.3% Other. There were no differences in gender, c2(1) = .01, p = .98; grade, c2(2) = .61, p = .74; race/ethnicity, c2(5) = 4.41, p = .49; or age, t (85) = .41, p = .52, between students who completed the follow-up assessment and those who did not.

Procedure

The university IRB approved all study procedures. A member of our research team explained the purpose of the training and study procedures to all students during classtime, invited students to participate, and provided students with an informed consent form to take home to parents/guardians. Immediately prior to collecting baseline data (T1), our team members collected assent forms from students who had a signed informed consent form. Our team members conducted the STAC training in two 45-minute modules, followed by two weekly 15-minute booster sessions. Students completed a 6-week follow-up survey (T2). Trainers conducted the STAC intervention through six groups (two per grade level) ranging from 20–30 students per group. All students participated in the training; however, only those with informed consent and assent participated in the data collection. All procedures occurred during classroom time.

The STAC Program

Didactic Component. In the STAC program, trainers present educational information that includes (a) an overview of bullying; (b) different types of bullying (i.e., physical, verbal, relational, and cyberbullying); (c) characteristics of students who bully; (d) reasons students bully; (e) negative consequences associated with being a target, perpetrator, and/or bystander; (f) the role of the bystander and the importance of acting as a “defender”; (g) perceived barriers for intervening; and (h) the STAC strategies described below.

Stealing the Show. “Stealing the show” is a strategy aimed at interrupting a bullying situation by using humor, storytelling, or other forms of distraction to get the attention off of the bullying situation and the target. Students learn how to identify bullying situations that are appropriate to intervene in using this strategy. Students are trained not to use “stealing the show” to intervene during physical or cyberbullying.

Turning It Over. “Turning it over” involves seeking out a trusted adult to intervene in difficult bullying situations. Students learn how to identify bullying situations that require adult intervention, specifically physical bullying, cyberbullying, and/or any bullying situation they do not feel comfortable intervening in directly.

Accompanying Others. “Accompanying others” is a strategy aimed at offering support to the target of bullying. Students learn to comfort targets either directly by asking them if they would like to talk about the incident or indirectly by spending time with them.

Coaching Compassion. “Coaching compassion” is a strategy aimed at helping the perpetrator of bullying to develop empathy for students who are targets. Students learn to safely and gently confront those who are perpetrators by engaging them in a conversation about the impacts of bullying and communicating that bullying behavior is never acceptable. Trainers teach students to use this strategy only when they are friends with the perpetrator, are older than the perpetrator, or believe they have higher social status and will be respected by the perpetrator.

Experiential Component. Students participate in small group role-plays to practice each of the four STAC strategies across varying bullying scenarios. These scenarios include different types of bullying, such as spreading rumors, verbal and physical bullying, and cyberbullying. Each small group presents a role-play to the larger group and trainers provide both positive and constructive feedback to help students use the strategy more effectively in the future.

Booster Sessions. Students participate in two booster sessions to reinforce learning and skill acquisition. During the booster session, trainers review the STAC strategies, encourage students to share their experiences using the strategies, and brainstorm ways to help students be more effective defenders. The trainers invite students to share bullying situations that they have observed, including those in which they did not intervene, and then brainstorm with other students how they could intervene in the future.

Intervention Fidelity. The developer of STAC trained the trainers previously, and both trainers had experience delivering the STAC intervention prior to this study. The first author, Matthew Peck, served as one of two trainers during the intervention training used in this study; the other was a graduate student not involved in the later development of this article. The third author, Aida Midgett, was present during the training to ensure it was delivered with fidelity. Midgett completed a dichotomous rating scale (Yes or No) to evaluate whether the trainers accurately taught the material and whether they deviated from the intervention protocol, and determined that the trainers delivered the STAC training with high levels of fidelity.

Measures

Demographic Survey

Participants completed a demographic survey including questions about gender, grade, age, and race/ethnicity. Participants indicated their gender, grade, and age through open-ended questions and provided their race/ethnicity through response choices.

Bystander Intervention Model Steps

We assessed the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model using the 16-item Bystander Intervention in Bullying Questionnaire (Nickerson et al., 2014). The original scale was developed for high school students and focused on bullying and sexual harassment. Jenkins and Nickerson (2016) adapted the scale for middle school students to focus on bullying only. The questionnaire is comprised of five scales: Notice the Event (3 items), Interpret the Event as an Emergency (3 items), Accept Responsibility (3 items), Know How to Act (3 items), and Decision to Intervene (4 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items include: “I am aware that students at my school are bullied” (Notice), “I think bullying is hurtful and damaging to others” (Interpret), “I feel personally responsible to intervene and assist in resolving bullying incidents” (Accept), “I have the skills to support a student who is being treated disrespectfully” (Know), and “I would say something to a student who is acting mean or disrespectful to a more vulnerable student” (Intervene). Confirmatory factor analyses support the five-factor structure, and convergent validity analyses using the Defending subscale of the Bullying Participant Behaviors Questionnaire (Summers & Demaray, 2008) has been demonstrated by providing positive correlations ranging from .26 to .35 among middle school students (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). Researchers have also demonstrated high internal consistency for the subscales among middle school students, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .77 to .87 for the five subscales (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). For the current sample, the scales had acceptable internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .66 to .71. For the Interpret subscale, we deleted one item (i.e., “It is evident to me that someone who is being bullied needs help”) to reach an acceptable level of internal consistency (α = .66) for the scale.

Defending Behavior

We utilized the 3-item Defender subscale of the Participants Roles Questionnaire (PRQ; Salmivalli et al., 2005) to measure defending behaviors students may use to intervene when witnessing bullying. The subscale includes the following items: “I comfort the victim or encourage him/her to tell the teacher about the bullying,” “I tell the others to stop bullying,” and “I try to make the others stop bullying.” Items are rated on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 2 (often). Confirmatory factor analyses support the five-factor structure of the PRQ measure, and construct validity has been demonstrated through significant associations between self-reported roles and sociometric status (e.g., popular, rejected, and average), χ2 = 117.7–141.6, all p values < .001, and peer nominations, χ2 = 57.9–88.2, all p values < .001 (Goossens et al., 2006). Among middle school students, the Defender subscale has good internal reliability ranging from α = .79–.93 (Camodeca & Goossens, 2005; Salmivalli et al., 2005). For

the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was high (α = .80).

Bystander Status

We assessed bystander status by asking participants, “Have you seen bullying at school in the past month?” with response choices Yes and No. The item was developed by the second author, Diana M. Doumas, to assess whether or not students had the opportunity to respond to a bullying incident. Students who reported Yes were classified as bystanders (i.e., the student witnessed bullying and had the opportunity to respond) and students who reported No were classified as non-bystanders (i.e., students who did not witness bullying and, therefore, did not have the opportunity to respond). The item has face validity and researchers have utilized this item previously to measure bystander status among middle school students (Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Moran et al., 2019). In this study, the 30.4% of students who reported Yes to this item at the follow-up assessment (T2) were classified as bystanders, and the 59.6% of students who reported No were classified as non-bystanders.

Data Analyses

We conducted all analyses using SPSS version 28.0. We imputed missing data and examined all variables for skew and kurtosis. We used a general linear model (GLM) repeated measures multivariate analyses of covariance (RM-MANCOVA) to examine changes in engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model between bystanders and non-bystanders across time for the outcome variables Notice the Event, Interpret the Event as an Emergency, Accept Responsibility, Know How to Act, and Decision to Intervene. The independent variables were Time (baseline [T1]; follow-up [T2]) and Bystander Status (bystander; non-bystander). We also controlled for gender, age, and witnessing bullying at baseline. We conducted post-hoc GLM repeated measures analyses of covariance (RM-ANCOVAs) for each outcome variable. We plotted simple slopes to examine the direction and degree of the significant interactions testing moderator effects (Aiken & West, 1991). We only interpreted significant main effects in the absence of significant interaction effects. For changes in defending behavior, we used a GLM RM-ANCOVA. The independent variables and control variables paralleled the RM-MANCOVA analysis. We conducted a linear multiple regression to examine engagement of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model as predictors of post-training defending behavior. The five steps were entered simultaneously in the regression analysis. We calculated bivariate correlations among the criterion and predictor variables prior to conducting the main regression analyses. We examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) for predictors to assess multicollinearity. We calculated effect size for the ANCOVA models using partial eta squared (ηp2) with .01 considered small, .06 considered medium, and .14 considered large (Cohen, 1969) and for the regression model using R2 with .01 considered small, .09 considered medium, and .25 considered large (Cohen, 1969). A p-value of < .05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations for the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model and defending behavior are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Skew and kurtosis were satisfactory and did not substantially deviate from the normal distribution for all variables. Bivariate correlations for the criterion and predictor variables are presented in Table 3. Although several of the correlations between the predictor variables were significant at p < .01, the VIF ranged between 1.08–2.69, with corresponding tolerance levels ranging from .37–.93. The VIF is well below the rule of thumb of VIF < 10 (Erford, 2015), suggesting acceptable levels of multicollinearity among the predictor variables.

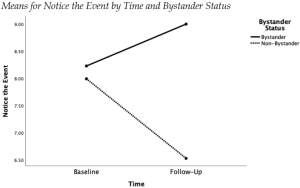

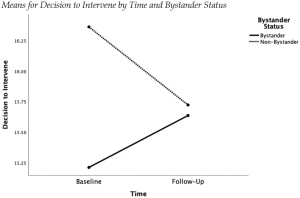

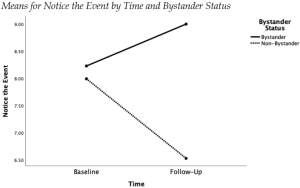

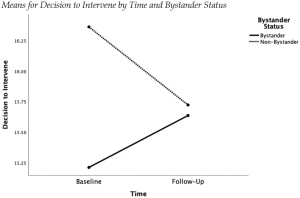

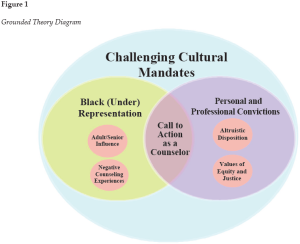

Changes in the Bystander Intervention Model

Results of the RM-MANCOVA indicated a significant main effect for Time, Wilks’ lambda = .86, F(5, 70) = 2.32, p =.05, ηp2 = .14., and a significant interaction effect for Time x Bystander Status, Wilks’ lambda = .77, F(5, 70) = 4.15, p =.002, ηp2 = .23. As seen in Table 1, post-hoc RM-ANCOVAs indicated a significant main effect for Time x Know How to Act (p < .02) and Decision to Intervene (p < .01), as well as significant interaction effects for Time x Bystander Status for Notice the Event (p < .001) and Decision to Intervene (p < .05). Results indicate that Know How to Act increased from baseline (T1) to the follow-up assessment (T2) for both bystanders and non-bystanders. Examination of the significant Time x Bystander Status interaction effects revealed that bystanders reported an increase in Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene, whereas non-bystanders reported a decrease in engagement in these steps of the Bystander Intervention Model (see Figures 1 and 2).

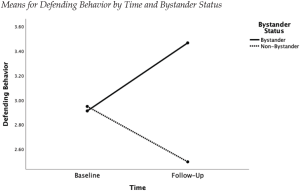

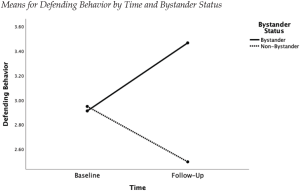

Changes in Defending Behavior

As seen in Table 2, results of the RM-ANCOVA indicated a significant interaction effect for Time x Bystander Status for defending behavior (p < .04). As seen in Figure 3, bystanders reported an increase in defending behavior from T1 to T2, whereas non-bystanders reported a decrease in defending behavior from T1 to T2.

The Relationship Between the Bystander Intervention Model and Defending Behavior

As seen in Table 3, bivariate correlations revealed a positive association between post-training defending behavior and Notice the Event (p < .01), Accept Responsibility (p < .05), Know How to Act (p < .05), and Decision to Intervene (p < .01). We next conducted a linear multiple regression analysis to examine the unique effect of each of the five steps on post-training defending behavior. The full regression equation was significant, R2 = .18, F(53, 7) = 4.39, p = .002. As seen in Table 4, Notice the Event (p < .01) and Decision to Intervene (p < .05) were significant predictors of post-training defending behavior.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Results of the RM-MANCOVAs for Engagement in the Five Steps of the Bystander Intervention Model by Time and Bystander Status

|

Bystander

(n = 24) |

Non-Bystander

(n = 55) |

Total

(n = 79) |

Time |

Time x Bystander Status |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

F(5, 70) |

p |

ηp2 |

F(5, 70) |

p |

ηp2 |

| Notice the Event |

|

|

1.12 |

.29 |

.02 |

14.10*** |

.001 |

.16 |

| Baseline |

8.75 (2.21) |

7.76 (2.35) |

8.06 (2.34) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

9.50 (2.23) |

6.31 (2.36) |

7.28 (2.74) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Interpret as Emergency |

|

|

1.68 |

.20 |

.02 |

0.08 |

.78 |

.001 |

| Baseline |

8.98 (1.05) |

8.58 (1.47) |

8.70 (1.36) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

8.54 (1.56) |

8.36 (1.46) |

8.42 (1.48) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Accept Responsibility |

|

|

0.81 |

.37 |

.01 |

2.62 |

.11 |

.03 |

| Baseline |

11.12 (2.26) |

11.63 (2.17) |

11.49 (2.19) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

11.38 (1.91) |

11.09 (2.25) |

11.18 (2.14) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Know How to Act |

|

|

5.31* |

.02 |

.07 |

1.75 |

.19 |

.02 |

| Baseline |

10.63 (1.81) |

10.95 (2.26) |

10.85 (2.12) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

11.63 (2.34) |

11.54 (1.78) |

11.56 (1.95) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Decision to Intervene |

|

|

6.73** |

.01 |

.08 |

4.12* |

.05 |

.05 |

| Baseline |

15.46 (2.47) |

16.25 (2.24) |

16.01 (2.32) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

15.71 (2.35) |

15.69 (2.43) |

15.70 (2.39) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| *p < .05, **p < .01,***p < .001. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics and Results of the RM-ANCOVA for Defending Behavior by Time and Bystander Status

|

Bystander

(n = 24) |

Non-Bystander

(n = 55) |

Total

(n = 79) |

Time |

Time x Bystander Status |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

F(1, 74) |

p |

ηp2 |

F(1, 74) |

p |

ηp2 |

| Defending Behavior |

|

|

1.36 |

.25 |

.02 |

4.61* |

.04 |

.06 |

| Baseline |

3.17 (1.46) |

2.84 (1.81) |

2.94 (1.71) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

3.67 (1.66) |

2.41 (1.89) |

2.79 (1.90) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

*p < .05.

Table 3

Bivariate Correlations for Defending Behavior and the Five Steps of the Bystander Intervention Model

| Measure |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| 1. Defending Behavior |

__ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Notice the Event |

.31** |

__ |

|

|

|

|

| 3. Interpret as an Emergency |

.04 |

.09 |

__ |

|

|

|

| 4. Accept Responsibility |

.23* |

.11 |

.30** |

__ |

|

|

| 5. Know How to Act |

.26* |

−.07 |

.01 |

.67** |

__ |

|

| 6. Decision to Intervene |

.38** |

.11 |

.29** |

.56** |

.63** |

__ |

*p < .05, **p < .01.

Table 4

Summary of Linear Multiple Regression Analyses for the Five Steps of the Bystander Intervention Model

| Variable |

B |

SE B |

β |

t(73) |

95% CI |

| Notice the Event |

.20 |

.07 |

.29** |

2.70 |

[.05, .35] |

| Interpret as an Emergency |

−.10 |

.15 |

−.08 |

−0.68 |

[−.40, .20] |

| Accept Responsibility |

−.02 |

.14 |

−.02 |

−0.12 |

[−.29, .25] |

| Know How to Act |

.08 |

.16 |

.08 |

0.49 |

[−.25, .41] |

| Decision to Intervene |

.27 |

.12 |

.33* |

2.30 |

[.04, .50] |

Note. SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

Figure 1

Means for Notice the Event by Time and Bystander Status

Note. Simple slopes are shown depicting the direction and degree of the significant interaction testing moderator effects (p = .001). Bystanders reported an increase in Notice the Event and non-bystanders reported a decrease in Notice the Event.

Figure 2

Means for Decision to Intervene by Time and Bystander Status

Note. Simple slopes are shown depicting the direction and degree of the significant interaction testing moderator effects (p = .05). Bystanders reported an increase in Decision to Intervene and non-bystanders reported a decrease in Decision to Intervene.

Figure 3

Means for Defending Behavior by Time and Bystander Status

Note. Simple slopes are shown depicting the direction and degree of the significant interaction testing moderator effects (p = .05). Bystanders reported an increase in defending behavior and non-bystanders reported a decrease in defending behavior.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to extend the literature on bystander interventions by examining the STAC intervention in the context of the Bystander Intervention Model. This is the first study to identify positive changes in engagement in steps of the Bystander Intervention Model following implementation of a bystander bullying intervention (i.e., STAC) and to illustrate how engagement in the steps of the model relates to post-training defending behavior. Overall, results indicate students trained in STAC reported changes in engagement in three of the five steps of the model and an increase in defending behavior from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up assessment (T2). Further, two of the five steps of the model were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior.

Findings indicate that there were significant changes in the Bystander Intervention Model steps of Notice the Event, Know How to Act, and Decision to Intervene from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2). For Know How to Act, there was a significant increase for both bystanders and non-bystanders from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up assessment (T2). These findings parallel prior research on the STAC intervention that indicates students trained in the program report an increase in knowledge and confidence to intervene in bullying situations (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett, Moody, et al., 2017; Moran et al., 2019). For Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene, we found differences between bystanders and non-bystanders over time, such that there was an increase in engagement in these steps among students who reported witnessing bullying but a decrease among students who did not report witnessing bullying after training. Findings among bystanders are consistent with previous research demonstrating that students trained in the STAC intervention report an increase in ability to identify bullying (Midgett, Doumas, et al., 2017), awareness of bullying situations (Johnston et al., 2018), and confidence to intervene (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett, Doumas, et al., 2017; Moran et al., 2019). In contrast, non-bystanders may have reported a decrease in these steps because they did not witness bullying after training.

We did not find significant differences from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2) for either group in engagement in the steps Interpret the Event as an Emergency and Accept Responsibility. For Interpret the Event as an Emergency, a possible explanation for this finding is that students reported high scores on this step at baseline. After removing one item on the scale to achieve adequate internal reliability, the maximum score on the scale was 10.00, with a baseline mean of 8.98 for bystanders and 8.58 for non-bystanders. Thus, students in this sample already had a high understanding of the significance of bullying and the importance of helping targets of bullying, which may have been communicated to them prior to our study when the school decided to implement a bullying intervention program. For Accept Responsibility, while the STAC program was designed to provide students with knowledge, skills, and confidence to intervene in bullying situations, the training content is less focused on taking personal responsibility when witnessing bullying. Thus, this may be an important area for future development, emphasizing the importance of each student taking personal responsibility for acting as a “defender” and that by doing that, each student has an important role in reducing bullying and shifting school climate in a positive direction.

Findings also reveal differences in defending behavior from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2) based on bystander status. Specifically, students who witnessed bullying post-training reported an increase in defending behavior, whereas students who did not witness bullying behavior post-training reported a decrease in defending behavior. Findings among the student bystanders are consistent with research demonstrating that more than 90% of middle school students who witness bullying post-training use the STAC strategies to intervene in bullying situations (Midgett & Doumas, 2020;

Moran et al., 2019). The decrease in defending behavior among students who did not witness bullying post-training can likely be explained by the lack of opportunity to utilize defending behavior.

Finally, we examined engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model as predictors of post-training defending behavior. Although prior research indicates that engagement in each of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model correlate positively with defending behavior among middle school students (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016), this is the first study to examine the unique effect of engagement in each of the five steps on post–bystander training defending behavior. Results of the regression analysis indicated that Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were significant predictors of defending behavior. These findings are particularly promising, as engagement in the steps Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene both increased from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2) for students who witnessed bullying after training. Thus, among students who witness bullying as bystanders, the STAC intervention was effective in increasing engagement in the two steps of the bystander model that are uniquely associated with defending behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study extends research on the Bystander Intervention Model, as it is the first study to examine engagement in the steps of the model in the context of a bystander intervention, there are some limitations. First, the sampling frame included a single recruitment location at a private school in the Northwest, and our final sample was relatively small and composed of English-speaking students who were primarily White. Thus, we cannot generalize our findings to students enrolled in ethnically diverse, public middle schools. Further, because the current study did not include a control group, we cannot make causal attributions about our findings. Future studies with larger, more diverse samples using a randomized controlled design should be conducted to increase generalizability and address causality. Additionally, only one third of students in the current sample reported witnessing bullying post-training. Although prior research indicates 80% of students reported witnessing bullying in the past year, our measure of bystander status was limited to witnessing bullying in the past month, as we aimed to capture witnessing bullying post-training. Future research with a longer follow-up would be useful, as the sample of bystanders would likely be larger with more time between the STAC training and follow-up assessment. Additionally, the item we used to assess bystander status was developed by one of our authors and, although it has face validity, the construct validity of the item has not yet been established. Next, Cronbach’s alphas for the Bystander Intervention Model in Bullying Questionnaire scales were lower than found in initial validation research. Additionally, although all Cronbach’s alphas were ultimately in the acceptable range, we needed to eliminate an item from the Interpret the Event as an Emergency scale to achieve adequate internal consistency. Finally, our findings were based on self-report data, potentially leading to biased reporting. Thus, including objective measures of observable “defending” behavior would strengthen the findings.

Implications

The current study provides important implications for counselors related to supporting the role of bystanders in bullying prevention. First, findings add to the growing body of literature supporting the STAC intervention as an effective school-based bullying prevention program. Because 28% of middle school students report being bullied (CDC, 2020), and bullying victimization (Moore et al., 2017) and witnessing bullying (Doumas & Midgett, 2021; Midgett & Doumas, 2019) are associated with significant mental health risks, it is imperative that students are equipped with skills they can use to act as “defenders.” Middle school counselors can implement STAC as a brief, school-wide intervention through core curriculum classroom lessons as part of a school counseling curriculum.

Second, by focusing on specific steps within the Bystander Intervention Model, counselors can break down the complex process of bullying bystander behavior and have a better understanding of what enables students to intervene when they witness bullying. Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were both unique predictors of defending behavior among bystanders post-training. Thus, when delivering the STAC intervention, school counselors can increase awareness of bullying by providing education related to the definition of bullying, including what bullying is and is not, as well as the different types of bullying. School counselors can also encourage students to decide to intervene when they witness bullying by providing the skills and confidence needed to intervene using one of the four STAC strategies. Booster sessions may be particularly helpful in promoting the decision to intervene, as school counselors can use this time to reinforce student strategy use.

Next, we did not find changes in engagement in the steps Interpret the Event as an Emergency or Accept Responsibility. The STAC intervention provides education on the negative consequences associated with bullying; this information could be highlighted by counselors within the STAC training to emphasize the magnitude of the problem of bullying and underscore the importance of identifying bullying as an emergency that needs to be addressed. Additionally, when discussing bystander roles, counselors can tie in the concept of why school personnel need students to help address bullying, focusing on the importance of each student taking personal responsibility for making a difference at school by acting as a defender. When conducting the STAC training, it may also be important to engage students who have not witnessed bullying. Although most students witness bullying at some point during adolescence, not all students have witnessed bullying, or witnessed bullying recently. Thus, it may be important to address this in the training, suggesting that even if a student has not witnessed bullying, it is important to learn about bullying and being a “defender,” as they may witness bullying in the future.

This study also provides implications for counselors working with youth outside of the school setting. Counselors can conceptualize bystander behavior using the Bystander Intervention Model, assessing engagement in each step of the model and providing education to enhance engagement in each step as needed. Counselors can teach youth about bullying behavior and the different types of bullying, provide information about the consequences of bullying to educate youth on the importance of interpreting bullying as a serious problem, and discuss the importance of taking personal responsibility when witnessing bullying. Consistent with Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977), counselors can use the STAC framework to equip youth with skills they can use to intervene when they witness bullying, which can provide opportunities for them to develop and strengthen their self-efficacy through social modeling and mastery experiences to overcome potential challenges. Because self-efficacy influences the decision-making process, the ability to act in the face of difficulty, and the amount of emotional distress experienced while completing a difficult task (Bandura, 2012), self-efficacy can be an important factor in mobilizing youth to engage in the steps of the Bystander Intervention Model. By working with youth on these steps, counselors can empower youth to intervene when they witness bullying and provide youth with prosocial skills they can use to intervene effectively.

Further, this study provides implications for counselor educators. Efforts to reduce bullying and the associated long-standing negative effects on students are widespread in the field, whether working inside schools or in clinical settings. Conversations related to bystander bullying intervention, however, do not seem to have entered counselor education classrooms on a wide scale. Counselor educators can share findings from this study in their courses to educate counseling students on how to provide youth who witness bullying with useful strategies that empower them to confront future instances of school bullying and cyberbullying. The Bystander Intervention Model and the STAC intervention can be infused into the counselor education curriculum to prepare counselors-in-training to work with youth as allies in the prevention of school bullying.

Conclusion

This was the first study to examine if a bullying bystander intervention increases student engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model and if engagement in the five steps of the model is related to post-training defending behavior. Results indicate that from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2), both bystanders and non-bystanders trained in the STAC intervention reported changes in Know How to Act, whereas only bystanders reported increases in Notice the Event, Decision to Intervene, and defending behavior. Further, Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior. Results underscore the importance of guiding students through the bystander process in bullying prevention and provide additional support for the effectiveness of the STAC intervention.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606

Bauman, S., Yoon, J., Iurino, C., & Hackett, L. (2020). Experiences of adolescent witnesses to peer victimization: The bystander effect. Journal of School Psychology, 80, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.03.002

Camodeca, M., & Goossens, F. A. (2005). Children’s opinions on effective strategies to cope with bullying: The importance of bullying role and perspective. Educational Research, 47(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188042000337587

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). #StopBullying. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/stop-bullying/index.html

Cohen, J. (1969). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Academic Press.

Doumas, D. M., & Midgett, A. (2021). The association between witnessing cyberbullying and depressive symptoms and social anxiety among elementary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 58(3), 622–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22467

Erford, B. T. (2015). Research and evaluation in counseling (2nd ed). Cengage.

Goossens, F. A., Olthof, T., & Dekker, P. H. (2006). New participant role scales: Comparison between various criteria for assigning roles and indications for their validity. Aggressive Behavior, 32(4), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20133

Jenkins, L. N., & Nickerson, A. B. (2016). Bullying participant roles and gender as predictors of bystander intervention. Aggressive Behavior, 43(3), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21688

Johnston, A. D., Midgett, A., Doumas, D. M., & Moody, S. (2018). A mixed methods evaluation of the “aged-up” STAC bullying bystander intervention for high school students. The Professional Counselor, 8(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.15241/adj.8.1.73

Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? Prentice Hall.

Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2019). Witnessing bullying at school: The association between being a bystander and anxiety and depressive symptoms. School Mental Health, 11, 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09312-6

Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2020). Acceptability and short-term outcomes of a brief, bystander intervention program to decrease bullying in an ethnically blended school in low-income community. Contemporary School Psychology, 24, 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00321-w

Midgett, A., Doumas, D. M., Peralta, C., Bond, L., & Flay, B. (2020). Impact of a brief, bystander bullying prevention program on depressive symptoms and passive suicidal ideation: A program evaluation model for school personnel. Journal of Prevention and Health Promotion, 1(1), 80–103.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2632077020942959

Midgett, A., Doumas, D., Sears, D., Lundquist, A., & Hausheer, R. (2015). A bystander bullying psychoeducation program with middle school students: A preliminary report. The Professional Counselor, 5(4), 486–500. https://doi.org/10.15241/am.5.4.486

Midgett, A., Doumas, D., Trull, R., & Johnston, A. D. (2017). A randomized controlled study evaluating a brief, bystander bullying intervention with junior high school students. Journal of School Counseling, 15(9). http://www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v15n9.pdf

Midgett, A., Moody, S. J., Rilley, B., & Lyter, S. (2017). The phenomenological experience of student-advocates trained as defenders to stop school bullying. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12044

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

Moran, M., Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2019). Evaluation of a brief, bystander bullying intervention (STAC) for ethnically blended middle schools in low-income communities. Professional School Counseling, 23(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20940641

Nickerson, A. B., Aloe, A. M., Livingston, J. A., & Feeley, T. H. (2014). Measurement of the bystander intervention model for bullying and sexual harassment. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.003

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Porter, J. R., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2016). Children’s tendency to defend victims of school bullying. Professional School Counseling, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-20.1.1

Salmivalli, C., Kaukiainen, A., & Voeten, M. (2005). Anti-bullying intervention: Implementation and outcome. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(3), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X26011

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-T

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488

Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(5), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.597090

Summers, K. H., & Demaray, M. K. (2008). Bullying participant behaviors questionnaire. Northern Illinois University.

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003

Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Sacco, F. C. (2004). The role of the bystander in the social architecture of bullying and violence in schools and communities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036(1), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1330.014

U.S. Department of Education: National Center for Educational Statistics. (2019). Student reports of bullying: Results from the 2017 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCES 2017-015). https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019054.pdf

van der Ploeg, R., Kretschmer, T., Salmivalli, C., & Veenstra, R. (2017). Defending victims: What does it take to intervene in bullying and how is it rewarded by peers? Journal of School Psychology, 65(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.06.002

Wu, W.-C., Luu, S., & Luh, D.-L. (2016). Defending behaviors, bullying roles, and their associations with mental health in junior high school students: A population-based study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1066. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3721-6

Matthew Peck, PhD, LPC, is an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas. Diana M. Doumas, PhD, LPC, is Distinguished Professor of Counselor Education at Boise State University. Aida Midgett, PhD, LPC, is a professor at Boise State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Matthew Peck, 100 Graduate Education Building, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, mattpeck@uark.edu.

Sep 13, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 2

Sapna B. Chopra, Rebekah Smart, Yuying Tsong, Olga L. Mejía, Eric W. Price

This mixed methods program evaluation study was designed to assist faculty in better understanding students’ multicultural and social justice training experiences, with the goal of improving program curriculum and instruction. It also offers a model for counselor educators to assess student experiences and to make changes that center social justice. A total of 139 first-semester students and advanced practicum students responded to an online survey. The Consensual Qualitative Research-Modified (CQR-M) method was used to analyze brief written narratives. The Multicultural Counseling Competence and Training Survey (MCCTS) and the Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment Survey (ACSA) were used to triangulate the qualitative data. Qualitative findings revealed student growth in awareness, knowledge, skills, and action, particularly for advanced students, with many students reporting a desire for more social justice instruction. Some students of color reported microaggressions and concerns that training centers White students. Quantitative analyses generally supported the qualitative findings and showed advanced students reporting higher multicultural and advocacy competencies compared to beginning students. Implications for counselor education are discussed.

Keywords: social justice, program evaluation, training, multicultural counseling, counselor education

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the long-standing inequities it brought to light, many universities began examining the ways that injustice unfolds within their institutions (Mull, 2020). Arredondo et al. (2020) noted that counseling and counselor education continue to uphold white supremacy and center the experiences of White people within theories, training, and research. White supremacy culture promotes Whiteness as the norm and standard, intersects with and reinforces other forms of oppression, and shows up in institutions in both overt and covert ways, such as emphasis on individualism, avoidance of conflict, and prioritizing White comfort (Okun, 2021). Arredondo et al. (2020) called for counselor educators to engage in social justice advocacy and to unpack covert White supremacy in training programs. The present study investigated the multicultural and social justice training experiences of students in a Western United States counseling program so that counseling faculty can be empowered to uncover biases and better integrate social justice in the curriculum.

Counselor education programs are products of the larger sociopolitical environment and dominant patriarchal, cis-heteronormative, Eurocentric culture that often fails to “challenge the hegemonic views that marginalize groups of people” which “perpetuate deficit-based ideologies” (Goodman et al., 2015, p. 148). For example, the focus on the individual in traditional counseling theories can reinforce oppression by failing to address the role of systemic oppression in a client’s distress (Singh et al., 2020). Counseling theory textbooks usually provide an ancillary section at the end of each chapter focusing on multicultural issues (Cross & Reinhardt, 2017). White supremacy culture is so ubiquitous that it is typically invisible to those immersed within it (DiAngelo, 2018). It is not surprising then that counseling is often viewed as a White, middle-class endeavor, and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) clients frequently perceive that they should leave their cultural identities and experiences outside the counseling session (Turner, 2018). Counselor educators have been encouraged to reflect on how Eurocentric curricula and pedagogy may marginalize students and seek liberatory teaching practices that promote critical consciousness (Sharma & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021).

Students’ Perceptions of Their Growth, Learning Process, and Critiques of Their Training

Studies of mostly White graduate students show gains in expanding awareness of their own biases and privilege, knowledge about other cultures and experiences of oppression, as well as the importance of empowering and advocating for clients (Beer et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2015; Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019; Singh et al., 2010). Others indicated the benefits of integrating feminist principles in treatment (Hoover & Morrow, 2016; Singh et al., 2010). Consciousness-raising and self-reflection were key parts of multicultural and social justice learning (Collins et al., 2015; Hoover & Morrow, 2016), and could be emotionally challenging. Indeed, Goodman et al. (2018) identified a theme of internal grappling reflecting students’ experiences of intellectual and emotional struggle; others noted students’ experiences of overwhelm and isolation (Singh et al., 2010), as well as resistance, such as withdrawing or dismissing information that challenged their existing belief system (Seward, 2019). Researchers have also documented student complaints about their social justice training; for example, that social justice is not well integrated or that there was inadequate coverage of skills and action (Collins et al., 2015). Kozan and Blustein (2018) found that even among programs that espouse social justice, there was a lack of training in macro level advocacy skills. Barriers to engaging in advocacy included: lack of time (Field et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2010), emotional exhaustion stemming from observations of the harms caused by systemic inequities (Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019), and ill-informed supervisors (Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019).

The studies reviewed thus relied on samples of mainly White, cisgender, heterosexual women. Some noted that education on social justice is often centered on helping White students expand their awareness (Haskins & Singh, 2015). In one study focused on challenges faced by students of color, participants expressed frustration with the lack of diversity among their professors, classmates, and curriculum (Seward, 2019). Participants also experienced marginalization and disconnection when professors and students made offensive or culturally uninformed comments and when course content focused on teaching students with privileged identities. Students from marginalized communities also face isolation in academic settings and sometimes question the multicultural competence of their professors (Haskins & Singh, 2015), which in turn contributes to the underrepresentation of students of color in counseling and psychology (Arney et al., 2019).

The Present Study

Counselor educators must critically examine their curriculum, course materials, and overall learning climate for students (Haskins & Singh, 2015). Listening to students’ experiences and perceptions of their training offers faculty an opportunity to model cultural humility, gain useful feedback, and make necessary changes. Given the increased recognition of racial trauma and societal inequities, it is critical that counseling programs engage with students of diverse backgrounds as they seek to shift their pedagogy. Historically, academic institutions have responded to student demands with performative action rather than meaningful change (Zetzer, 2021). This mixed methods study is part of a larger process of counseling faculty working to invite student feedback and question internalized assumptions and biases in order to implement real change. The goal of program evaluation is to investigate strengths and weaknesses in order to improve the program (Royse et al., 2010). According to the 2024 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) standards, program evaluation is essential to assess and improve the program (CACREP, 2023). Thus, the purpose of this program evaluation study was to understand students’ self-assessment and experiences with the counseling program’s curriculum in the area of multicultural and social justice advocacy, with the overarching goal of program curriculum and instruction improvement. This article offers counselor educators a model of how to assess program effectiveness in multicultural and social justice teaching and practical suggestions based on the findings. The research questions were: What are beginning and advanced students’ self-perceptions regarding their multicultural and social justice advocacy competencies? What are beginning and advanced students’ perceptions of the multicultural and social justice advocacy competencies training they are receiving in their program?

Method

We employed a mixed method, embedded design in which the quantitative data offered a supportive and secondary role to the qualitative results (Creswell et al., 2003). Qualitative and mixed methods research designs are particularly useful in program evaluation (Royse et al., 2010). Mixed method approaches also offer value in research that centers social justice advocacy, as the integration of diverse methodological techniques within a single study fosters the understanding of multiple perspectives and facilitates a deeper comprehension of intricate issues (Ponterotto et al., 2013). We used an online survey to collect written narratives (qualitative) and survey data (quantitative) from two counseling courses: a beginning counseling course in the first semester (beginning students), and an advanced practicum course, taken by those who had completed at least part of their year-long practicum (advanced students).

Participants

Participants were counseling students enrolled in a CACREP-accredited program at a large West Coast public university in the United States that is both a federally designated Hispanic-serving institution and an Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander–serving institution. Responses were collected from two courses, which included 94 beginning students (84% response rate) and 62 advanced students (71% response rate). Twelve percent of the advanced practicum students also completed the survey when they were first-semester (beginning) students. The mean age of the 139 participants was 27.7 (SD = 7.11), ranging from 20 to 58 years. Racial identifications were 40.3% White, 33.1% Latinx, 14.4% Asian, 7.2% Biracial or Multiracial, 2.9% Black, 0.7% Middle Eastern, 0.7% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 0.7% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The majority identified as women (82.0%), followed by 14.4% as men, and 2.9% as nonbinary/queer. Students self-identified as heterosexual (71.2%), bisexual (11.5%), lesbian/gay (6.5%), queer (4.3%), pansexual (1.4%), and about 1% each as asexual, heteroflexible, and unsure. About 19.4% of students were enrolled in a bilingual/bicultural (Spanish/Latinx) emphasis within the program.

Procedure

After receiving university IRB approval, graduate students enrolled in the first-semester beginning counseling course (fall 2018 and 2019) or the advanced practicum course (summer 2019 and 2020) were asked to complete an online survey through Qualtrics with both quantitative measures and open-ended questions as part of their preparation for class discussion. Students were informed that this homework would not be graded and was not intended to “test” their knowledge but rather would serve as an opportunity to reflect on their experience of the program’s multicultural and social justice training. Students were also given the option to participate in the current study by giving permission for their answers to be used. Those who consented were asked to continue to complete the demographic questionnaire. In accordance with the American Counseling Association Code of Ethics (2014), students were informed that there would be no repercussions for not participating. A faculty member outside the counseling program managed the collection of and access to the raw data in order to protect the identities of the students and ensure that their participation or lack of participation in the study could not affect their grade for the course or standing in the program. All students, regardless of participation status, were given the option to enter an opportunity drawing for a small cash prize ($20 for data collection in 2018 and 2019, $25 for 2020) through a separate link not connected to their survey responses.

Data Collection

We collected brief written qualitative data and responses to two quantitative measures from both beginning and advanced students.

Qualitative Data

The faculty developed open-ended questions that would elicit student feedback on their multicultural and social justice training. Prior to beginning the counseling program, first-semester students were asked two questions about their experiences and impressions: How would you describe your knowledge about and interest in multiculturalism/diversity and social justice from a personal and/or academic perspective? and How would you describe your initial impressions or experience of the focus on multicultural and social justice in the program so far? They were also asked, if it was relevant, to include their experience in the Latinx counseling emphasis program component. Advanced students, who were seeing clients, were asked the same questions and also asked to: Consider/describe how this experience of multiculturalism and social justice in the program may impact you personally and professionally (particularly in work with clients) in the future.

Quantitative Data

Two instruments were selected to quantitatively assess students’ perceptions of their own multicultural and advocacy competencies. The Multicultural Counseling Competence and Training Survey (MCCTS; Holcomb-McCoy & Myers, 1999) is designed to assess counselors’ perceptions of their multicultural competence and the effectiveness of their training. The survey contains 32 statements for which participants answer on a 4-point Likert scale (not competent, somewhat competent, competent, extremely competent). Sample items include: “I can discuss family therapy from a cultural/ethnic perspective” and “I am able to discuss how my culture has influenced the way I think.” The reliability coefficients for each of the five components of the MCCTS ranged from .66 to .92: Multicultural Knowledge (.92), Multicultural Awareness (.92), Definitions of Terms (.79), Knowledge of Racial Identity Development Theories (.66), and Multicultural Skills (.91; Holcomb-McCoy & Myers, 1999). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .75 to .96.

The Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment Survey (ACSA; Ratts & Ford, 2010) assesses for competency and effectiveness across six domains: (a) client/student empowerment, (b) community collaboration, (c) public information, (d) client/student advocacy, (e) systems advocacy, and (f) social/political advocacy. It contains 30 statements that ask participants to respond with “almost always,” “sometimes,” or “almost never.” Sample questions include “I help clients identify external barriers that affect their development” and “I lobby legislators and policy makers to create social change.” Although Ratts and Ford (2010) did not provide psychometrics of the original ACSA, it was validated with mental health counselors (Bvunzawabaya, 2012), suggesting an adequate internal consistency for the overall measure, but not the specific domains. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .69 to.79 for the six domains, and .94 for the overall scale. For the purposes of this study, we were not interested in specific domains and used the overall scale to assess students’ overall social justice/advocacy competencies.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Data Analysis

To analyze the qualitative data, we used Consensual Qualitative Research-Modified (CQR-M; Spangler et al., 2012), which was based on Hill et al.’s (2005) CQR but modified for larger numbers of participants with briefer responses. In contrast to the in-depth analysis of a small number of interviews, CQR-M was ideal for our data, which consisted of brief written responses from 139 participants. CQR-M involves a consensus process rather than interrater reliability among judges, who discuss and code the narratives, and relies on a bottom-up approach, in which categories

(i.e., themes) are derived directly from the data rather than using a pre-existing thematic structure. Frequencies (i.e., how many participants were represented in each category) are then calculated. We analyzed the beginning and advanced students’ responses separately, as the questions were adjusted for their time spent in the program.

After immersing themselves in the data, the first two authors, Sapna B. Chopra and Rebekah Smart, met to outline a preliminary coding structure, then met repeatedly to revise the coding into more abstract categories and subcategories. The computer program NVivo was used to organize the coding process and determine frequencies. After all data were coded, the fifth author, Eric W. Price, served as auditor and provided feedback on the overall coding structure. Both the consensus process and use of an auditor are helpful in countering biases and preconceptions. Brief quantitative data, as used in this study, can be used effectively as a means of triangulation (Spangler et al., 2012).

Quantitative Data Analysis

To examine for significant differences in the self-perceptions of multicultural competencies and advocacy competencies between White and BIPOC students as well as between beginning and advanced students, a two-way (2×2) ANOVA was conducted with the overall MCCT as the criterion variable and student levels (beginning, advanced) and race (White, BIPOC) as the two independent variables. In addition, two (5×2) multivariate analyses of variances (MANOVAs) were conducted with the five factors of multicultural competencies (knowledge, awareness, definition of terms, racial identity, and skills) as criterion variables and with student levels (beginning, advanced) and student races (White, BIPOC) as independent variables in each analysis. Data for beginning and advanced students were analyzed separately to assess whether time in the counseling program helped to expand their interest and commitment to social justice.

Research Team

We were intentional in examining our own social identities and potential biases throughout the research process. Chopra is a second-generation South Asian American, heterosexual, cisgender woman. Smart is a White European American, heterosexual, cisgender woman. Yuying Tsong identifies as a genderqueer first-generation Taiwanese and Chinese American immigrant. Olga L. Mejía is an Indigenous-identified Mexican immigrant, bisexual, cisgender woman. Price is a White, gay, cisgender male. All have experience as counselor educators and in qualitative research methods, and all have been actively engaged in decolonizing their syllabi and incorporating multicultural and social justice into their pedagogy.

Results

The research process was guided by the overarching question: What are beginning and advanced counseling students’ perceptions of their multicultural and social justice competencies and training and how can their feedback be used to improve their counselor education program? We explore the qualitative findings first, as the primary data for the study, followed by the quantitative data.

Qualitative Findings for Beginning Counseling Students

Two higher-order categories emerged from the beginning students’ narratives: developing competencies and learning process so far.

Developing Competencies

Students’ descriptions of the competencies they were developing included themes of awareness, knowledge, and skills and action. Some students entered the program with an already heightened awareness, while others were making new discoveries. Awareness included subthemes of humility (24.5%), awareness of own privilege (6.4%), and awareness of bias (3.2%). “There’s a lot to learn” was a typical sentiment, particularly from White students. One White female student wrote: “I definitely need more and I believe that open discussions, even hard ones would be some of the best ways to go about this.” A large group expressed knowledge of oppression and systemic inequities (33%); a smaller group referenced intersectionality (3.2%). Within skills and action, some students expressed specific intentions in allyship (11.7%); a number of students expressed commitment to social action but felt unsure how to engage in social justice (11.7%).

Learning Process So Far

Central themes in this category were support for growth, concerns in training, and internal challenges. Some students felt excited and supported, while some were cautiously optimistic or concerned. Support for growth was a strong theme that reflected excited and enthusiastic to learn (22.3%); appreciation for the Latinx emphasis (18.1%); and receiving support from professors and program (17.0%). For example, one Mexican student in the Latinx emphasis who noted that mental health was rarely discussed in her family shared: “For me to see that there is a program that teaches students how to communicate to individuals who are unsure of what counseling is about, gave me a sense of happiness and relief.”

A few students were adopting a wait-and-see attitude and expressed some concerns about their training. Although the percentage for these subthemes is low, they provide an important experience that we want to amplify. This theme had multiple subthemes. The subtheme concerns from students of color included centering White students (3.2%), microaggressions (3.2%), and lack of representation (1.1%). A student who identified as a Mexican immigrant shared experiences of microaggressions, including classmates using a hurtful derogatory phrase referring to immigrants with no comment from the professor until the student raised the issue. Concerns in training also included the subtheme concerns with how material is presented in classes (7.0%). For some, the concern related to the potential for harm in classes in which White and BIPOC students were encouraged to process issues of privilege and oppression. For example, one Asian Pacific Islander student wrote that although they appreciated the emphasis on social justice, “Time always runs out and I believe it’s careless and dangerous to cut off these types of conversations in a rushed manner.” A small minority seemed to suggest a backlash to the emphasis on social justice, stating that the content was presented in ways that were too “politically correct,” “biased,” or “repetitive.”

Multiple subthemes emerged from the theme of internal challenges. Both BIPOC and White students shared feeling afraid to speak up (5.3%). BIPOC students expressed struggling with confidence or wanting to avoid conflict, while White students’ fear of speaking up was also connected to discomfort and uncertainty as a White person (2.1%). A small minority of White students did not express explicit discomfort but seemed to engage in a color-blind strategy, as indicated in the theme of people are people (2.1%): “I find people are people, regardless of any differences, and love hearing the good and bad about everybody’s experiences.” Some students of color expressed limited knowledge about cultures other than one’s own (4.3%). For example, an Asian American student stated that they had gravitated to “those who were most similar to me” growing up. Lastly, a few students shared feeling overwhelmed and exhausted (3.2%).

Qualitative Findings for Advanced Counseling Students

Four higher-order themes emerged: competencies in process, multiculturalism and diversity in the program, social justice in the program, and the learning process.

Competencies in Process