Dec 5, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 3

Fei Shen, Ying Zhang, Xiafei Wang

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has consistently been shown to have deleterious effects on survivors’ interpersonal and intrapersonal relationships. Despite the negative outcomes of IPV, distress after IPV varies widely, and not all IPV survivors show a significant degree of distress. The present study examined the impact of IPV on adult attachment and self-esteem, as well as the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationships between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem using path analysis. A total of 1,708 adult participants were included in this study. As hypothesized, we found that IPV survivors had significantly higher levels of anxious and avoidant adult attachment than participants without a history of IPV. Additionally, childhood attachment buffered the relationship between IPV and self-esteem. We did not find that childhood attachment moderated the relationship between IPV and adult attachment. These results provide insight on attachment-based interventions that can mitigate the negative effects of IPV on people’s perceptions of self.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, childhood attachment, adult attachment, self-esteem, moderation

More than 10 million adults experience intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization annually in the United States (Black et al., 2011); therefore, it undoubtedly remains a prominent public health concern. IPV victimization has been consistently associated with deleterious effects on survivors’ physical and mental health. It is well established that IPV survivors demonstrated increased risks for chronic pain, injury, insomnia, disabilities, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and suicidality (Burke et al., 2005; Gilbert et al., 2023; Matheson et al., 2015; McLaughlin et al., 2012). Historically, empirical studies on trauma and violence have focused on psychopathology and symptoms (McLaughlin et al., 2012; Sayed et al., 2015). However, there is limited research on exploring the link between IPV victimization and intrapersonal and interpersonal relationship outcomes. Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) not only provides a rich theoretical framework for conceptualizing an individual’s psychopathology, but also establishes a foundation for understanding the intrapersonal and relational sequelae of IPV (Levendosky et al., 2012; Sutton, 2019). IPV survivors often experience a violation of trust and a sense of betrayal in the aftermath and develop ineffective coping mechanisms (e.g., distancing themselves emotionally), which could potentially impact their new intimate relationships (St. Vil et al., 2021).

Despite the negative outcomes of IPV victimization, the levels of distress following such incidents can vary (Scott & Babcock, 2010). Although evidence has implicated numerous risk factors related to IPV victimization (e.g., childhood trauma, gender inequity; Jewkes et al., 2017; Meeker et al., 2020), limited effort has been put forth to recognize protective factors that contribute to IPV survivors’ coping and healing processes. Childhood attachment has been proposed as a potential protective factor for IPV survivors’ coping with traumatic experiences and a moderator for buffering the negative psychological outcomes of IPV (Pang & Thomas, 2020), which provides a meaningful foundation for us to further investigate childhood attachment as a moderator buffering relational outcomes. To our knowledge, no study to date has investigated the potential moderating role of childhood attachment security on the association between IPV, interpersonal outcomes (e.g., adult attachment), and intrapersonal outcomes (e.g., self-esteem) in a non-clinical sample. Understanding the moderating role of childhood attachment can potentially provide further directions toward protecting survivors from negative outcomes and creating interventions that foster healthier interpersonal relationships. In tackling the gaps in the literature, we aim to: (a) investigate the impact of IPV on adult attachment and self-esteem; and (b) examine the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationships between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem.

Theoretical Framework—Attachment Theory

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969) offers an explanation of how the relationship between children and their primary caregiver(s) develops and how it impacts children’s subsequent developmental process. According to Bowlby (1973), children develop mental representations of themselves and others, known as internal working models, through their interactions with their primary caregiver(s). Children with secure attachment are more likely to form positive self-perceptions and relationships with others (Bowlby, 1969). In contrast, children who develop insecure attachment are more likely to struggle with coping with distress and form poor relationships with others, resulting from caregivers responding to their needs insensitively.

Although evidence suggests the continuity of attachment from childhood to adulthood (Bowlby, 1969), there are distinctions between these two variables based on individuals’ attachment needs, developmental stages, and characteristics of different relationships. As children grow into adolescents and emerging adults, they often continue to maintain connections with their primary caregivers while exploring new social roles outside of the family and forming close relationships with peers and romantic partners to develop adult attachment (Moretti & Peled, 2004). Secure adult attachment is generally characterized by flexibility, the ability to work independently and cooperatively with others, the ability to seek support from intimate partners, and the capacity to manage loss in a healthy manner (Brennan et al., 1998). Adult romantic relationships are thought to be underlined by two fundamental attachment-related dimensions: anxiety and avoidance. Adults with anxious attachment tend to experience worry and fear regarding abandonment or rejection by their partner, leading them to seek constant reassurance and validation from their partner. On the other hand, avoidant-attached individuals often feel uncomfortable with being close to their partner, which can lead them to withdraw from intimacy and emotional closeness in the relationship (Brennan et al., 1998). Thus, understanding the similarities and differences of attachment categories as well as dynamics of the attachment system is warranted (Lopez & Brennan, 2000).

Childhood Attachment, IPV Victimization, and Adult Attachment

Various researchers have extensively investigated the significant association between attachment developed with romantic partners and its involvement in IPV dynamics (Bradshaw & Garbarino, 2004; Duru et al., 2019; Levendosky et al., 2012). However, most studies explored the relationship between adult attachment and IPV perpetration (Gormley & Lopez, 2010; McClure & Parmenter, 2020). Specifically, individuals with insecure attachment present intense fear of abandonment or rejection and activate their aggressive behaviors to control their partners (Gormley & Lopez, 2010). Regarding IPV victimization circumstances, few studies have examined attachment security among IPV survivors. Specifically, simultaneously exploring attachment with primary caregivers in childhood and attachment with romantic partners in adulthood could capture the complexity of the impact of IPV victimization experiences on relational and emotional outcomes. Ponti and Tani (2019) investigated both childhood attachment and adult attachment among 60 women who experienced IPV and indicated that the attachment to the mother could influence IPV victimization both directly and indirectly through the mediation effect of adult attachment with romantic partners. In other words, attachment with the mother could serve as a protector for not entering a violent romantic relationship or healthily managing the aftermath of traumatic experiences.

Childhood attachment has been identified as a potential moderator that may contribute to the variations of the healing process among IPV survivors in a small but growing number of studies (e.g., Scott & Babcock, 2010). Pang and Thomas (2020) examined the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationship between exposure to domestic violence in adolescence and psychological outcomes and adult life satisfaction with a sample of 351 adult college students. They found that childhood attachment moderated the relationship between IPV exposure and adult life satisfaction but not psychological outcomes. This study provides empirical support for the moderating role of childhood attachment on early IPV exposure and later adult psychological and relationship outcomes. Given the context in which IPV occurs in the intimate relationships, not addressing the association between childhood attachment and adult attachment together would not fully capture the complexity of the attachment process in the adult population. It is possible that the relationship between IPV victimization and adult attachment security would be attenuated in conditions of childhood attachment. Therefore, the moderation effect of childhood attachment in the context of IPV needs to be empirically substantiated.

Childhood Attachment, IPV Victimization, and Self-Esteem

Self-esteem generally refers to a person’s overall evaluation and attitude toward themself (Rosenberg, 1965). Experiencing IPV was found to have detrimental effects on an individual’s self-esteem; IPV survivors often have lower levels of self-esteem than non-abused individuals (Childress, 2013; Karakurt et al., 2014; Tariq, 2013). Experiencing IPV (e.g., emotional and psychological abuse) can lead to feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, making it difficult for survivors to maintain autonomy and make decisions that are in their best interest (Tariq, 2013). IPV survivors consistently reported feeling burdened with a sense of guilt, shame, and self-blame for being victimized (Lindgren & Renck, 2008). Unfortunately, this can contribute to a vicious cycle, as survivors who have low self-esteem are less likely to take steps to leave abusive relationships (Karakurt et al., 2014), which leads to further victimization (Eddleston et al., 1998). Understanding the link between IPV victimization and self-esteem is crucial, as rebuilding self-esteem can also help survivors develop stronger relationships with others, gain strength toward ending abusive relationships, reduce risks of mental health problems, and feel more empowered to seek help and support (Karakurt et al., 2022).

The development of the self can be seen to unfold in the context of attachment and the internalization of important others’ perceptions and expectations. Numerous studies have shed some light on the association between childhood attachment and self-esteem, suggesting that secure attachment with primary caregivers can serve as a key protective factor for developing higher levels of self-esteem (Shen et al., 2021; Wilkinson, 2004). In contrast, individuals who reported insecure attachment with their primary caregivers tended to demonstrate lower levels of self-esteem (Gamble & Roberts, 2005). However, interpersonal trauma such as IPV can produce long-term dysfunctions of self (Childress, 2013). Although no study has directly explored the moderating role of childhood attachment buffering the relationship between IPV and self-esteem, several studies have indicated that parental support serves as a moderator role in the relationship between interpersonal violence and self-esteem (Duru et al., 2019). Indeed, if a person had secure attachment experiences in childhood, they may have developed a positive sense of self-worth and the belief that they deserve love and respect, which could buffer the negative effects of IPV on their self-esteem. Considering the existing literature and theoretical explanations as a whole, it seems reasonable to postulate that childhood attachment might serve as a potential moderator of the association between IPV and self-esteem.

Taken together, the literature consistently supports the significance of exploring protective factors contributing to IPV survivors’ healing process, yet no study to date has investigated the potential moderating role of childhood attachment on the association between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem in a non-clinical diverse sample. In tackling these gaps, we pose two research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How is IPV associated with adult attachment and self-esteem?

RQ2: How does childhood attachment moderate the relationships between IPV, adult

attachment, and self-esteem?

We hypothesized that: 1) IPV victimization is significantly positively associated with adult attachment (i.e., anxious attachment, avoidant attachment) and negatively associated with self-esteem; 2) Childhood attachment moderates the relationship between IPV victimization and adult attachment (i.e., anxious attachment, avoidant attachment); and 3) Childhood attachment moderates the relationship between IPV victimization and self-esteem.

Method

Sampling Procedures

With approval from the university IRB, research recruitment information was posted on various social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Craigslist, university announcement boards). Individuals who were 18 years of age or older and able to fill out the questionnaire in English were eligible for the study. Participants were directed to an online Qualtrics survey to voluntarily complete the informed consent and the measures listed in the following section. At the end of the survey, participants were prompted to enter their email addresses to win one of 10 $15 e-gift cards. Their email addresses were not included for data analysis.

Participants

Of the 2,373 voluntary adult participants who took the survey, 1,708 (71.76%) individuals were retained for the final analysis, including 507 (29.68%) participants who experienced IPV in adulthood and 1,191 (69.73%) participants without a history of IPV in adulthood. We eliminated participants who either did not consent to the study (n = 36, 1.51%), were younger than 18 years old (n = 33, 1.39%), or did not complete 95% of the survey questions (n = 596, 25.11%). We examined whether those who were excluded from the sample because of missing or invalid data differed from those who were retained. There was a significant difference in age between the included sample (M = 28.89, SD = 12.38) and excluded sample (M = 32.10, SD = 13.51); t (2,255) = −3.48, p = 0.001. Therefore, excluding participants with missing data was less likely to significantly impact our results. Table 1 shows that 76.23% of the participants were female. The age range of the sample was broad, from 18 to 89 years old, with an average age of 30.

Table 1

Demographic and Key Variables Information (N = 1,708)

| Variables |

N |

Percent |

Range |

M(SD) |

| Childhood attachment |

1,708 |

100% |

1–5 |

3.34(0.92) |

| IPV status

IPV

Non-IPV |

1,698

507

1,191 |

99.41%

29.68%

69.73% |

0–1 |

|

| Self-Esteem |

1,704 |

99.77% |

3–40 |

26.98(7.46) |

| Anxious Attachment |

1,708 |

100% |

1–7 |

4.11(1.26) |

| Avoidant Attachment |

1,708 |

100% |

1–7 |

3.71(1.16) |

| Control Variables |

|

|

|

|

| Gender

Male

Female |

1,683

381

1,302 |

98.54%

22.31%

76.23% |

|

|

| Household Income

Less than $5,000

$5,000–$9,999

$10,000–$14,999

$15,000–$19,999

$20,000–$24,999

$25,000–$29,999

$30,000–$39,999

$40,000–$49,999

$50,000–$74,999

$75,000–$99,999

$100,000–$149,999

$150,000 or more |

1,514

183

96

119

83

98

78

128

141

239

143

139

67 |

88.64%

10.70%

5.60%

7.00%

4.90%

5.70%

4.60%

7.50%

8.30%

14.00%

8.40%

8.10%

3.90% |

|

|

Measures

Childhood Attachment

The parental attachment subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) was used to measure childhood attachment. Participants rated their attachment to their parent(s) or caregiver(s) who had the most influence on them during their childhood. The subscale consists of 25 items divided into three dimensions, including 10 items on Trust (e.g., “My mother/father trusts my judgment”), nine items on Communication (e.g., “I can count on my mother/father when I need to get something off my chest”), and six items on Alienation (e.g., “I don’t get much attention from my mother/father”). Participants rated the items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never or never true) to 5 (almost always or always true). Responses were averaged, with a higher score reflecting more secure childhood attachment. This subscale has demonstrated relatively high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .93 (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), and construct validity (Cherrier et al., 2023; Gomez & McLaren, 2007). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this subscale was .96.

Intimate Partner Violence

Participants’ experiences of IPV were assessed through the question “Have you ever experienced intimate partner violence (physical, sexual, or psychological harm) by a current or former partner or spouse since the age of 18?” Responses were coded as 1 = Yes, 0 = No.

Adult Attachment

Adult attachment was measured using the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR; Brennan et al., 1998). The ECR consists of 36 items with 18 items assessing each of the two dimensions: anxious attachment (e.g., “I worry about being abandoned”) and avoidant attachment (e.g., “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner/friends”). To reduce confounding factors with childhood attachment with their parent(s) or primary caregiver(s), we only assessed adult attachment with close friends and/or romantic partners. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Two scores were computed by averaging items on each subscale, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of anxious or avoidant attachment. Two subscales demonstrated high construct validity in various studies (Gormley & Lopez, 2010; Ponti & Tani, 2019) and a relatively high consistency for anxiety (α = .91) and avoidance (α = .94; Brennan et al., 1998). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the present study were .93 for anxiety and .92 for avoidance.

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965) is a 10-item self-report measure of overall feelings of self-worth or self-acceptance (e.g., “I am satisfied with myself”). All items were coded using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Items were summed, with a higher score indicating a higher level of self-esteem. RSES has been frequently used in various studies, demonstrating high reliability and validity (Brennan & Morris, 1997; Rosenberg, 1979). The Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .89.

Control Variables

To make more accurate estimates, we included control variables that are potentially associated with IPV exposures, such as gender and household income. Gender was dummy coded as 1 = Male, 2 = Female.

Data Analysis

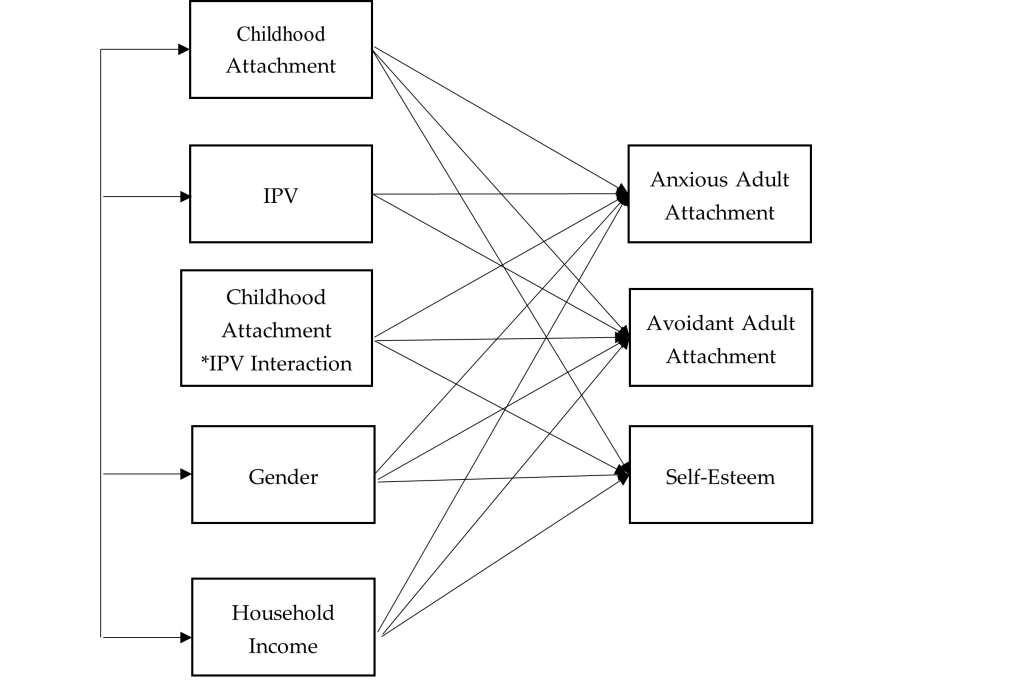

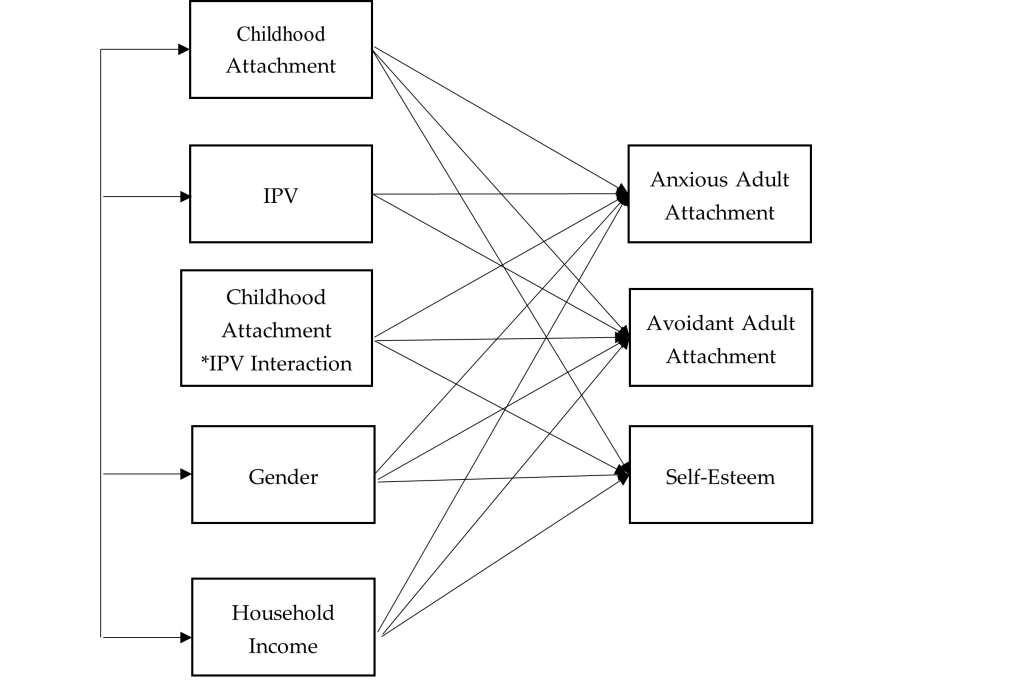

We used SPSS 27 for data preparation and Mplus 8 for data analysis. Missing data were treated with the full information maximum likelihood in Mplus as recommended (Acock, 2005). We examined all the bivariate relationships between all the variables within our study including IPV, childhood attachment, adult attachment (anxious and avoidant attachment), self-esteem, and control variables (i.e., gender and household income). We conducted path analysis to examine the moderating role of childhood attachment between IPV, self-esteem, and adult attachment (see Figure 1). We computed an interaction term by multiplying the predictor (IPV) and the moderator (childhood attachment). A moderation relationship is identified if the interaction item significantly predicts the dependent variables (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The goodness of model fit was evaluated by recommended indices with a non-significant chi-square value, RMSEA < .08, CFI > .90, TLI > .90, and SRMR < .05 (Hooper et al., 2008).

Figure 1

Path Analysis: Moderating Effect of Childhood Attachment on the Relationship Between IPV, Self-Esteem, and Adult Attachment

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the study variables are demonstrated in Tables 1 and 2. Our model demonstrated good fit to the data, with χ2(4) = 41.90, p = .001, RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.05, .08], CFI = .99, TLI = .99, SRMR = .02.

The standardized coefficients of the path model revealed that IPV survivors tended to have higher levels of anxious adult attachment (b = .67, p < .001) and avoidant adult attachment (b = .62, p < .001), and lower levels of self-esteem (b = −.29, p < .001) compared with participants without a history of IPV (see Table 3). Individuals with more secure childhood attachment tended to have lower levels of anxious adult attachment (b = −.38, p < .001) and avoidant adult attachment (b = −.31, p < .001), and higher levels of self-esteem (b = .22, p < .001). We found that childhood attachment buffered the relationship between IPV and self-esteem (b = .12, p < .001). Specifically, IPV survivors with more secure childhood attachment demonstrated higher levels of self-esteem. Although the moderation effect was statistically significant, the magnitude of the effect was small. Moreover, IPV survivors with more secure childhood attachment did not demonstrate significant differences on anxious or avoidant adult attachment compared to participants without a history of IPV.

Table 2

Bivariate Correlation Matrix of Variables

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| 1. Anxious Adult Attachment |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Avoidant Adult Attachment |

.40*** |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. Self-Esteem |

−.18*** |

−.15*** |

– |

|

|

|

|

| 4. Childhood Attachment |

−.45*** |

−.47*** |

.18*** |

– |

|

|

|

| 5. IPV |

.26*** |

.54*** |

−.17*** |

−.31*** |

– |

|

|

| 6. Gender |

−.10*** |

−.06** |

.14*** |

−.01 |

−.08*** |

– |

|

| 7. Household Income |

.03 |

.08*** |

−.05* |

−.08** |

−.06* |

−.01 |

– |

*p < .05 (two-tailed). **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 3

Unstandardized and Standardized Path Coefficients (Standard Errors) for Path Analysis

| Parameter Estimates |

|

Anxious Adult

Attachment |

Avoidant Adult

Attachment |

Self-esteem |

| Childhood Attachment |

Unstandardized |

−.37(.01)*** |

−.33(.02)*** |

.26(.04)*** |

| |

Standardized |

−.38(.01)*** |

−.31(.02)*** |

.22(.03)*** |

| IPV |

Unstandardized |

.61(.01)*** |

.62(.02)*** |

−.33(.04)*** |

| |

Standardized |

.67(.01)*** |

.62(.02)*** |

−.29(.03)*** |

| IPV*Childhood Attachment

Interaction |

Unstandardized |

.00(.00) |

.01(.01) |

.10(.02)*** |

| Standardized |

.01(.01) |

.01(.01) |

.12(.02)*** |

| Control Variables |

| Gender |

Unstandardized |

−.03(.01)** |

−.08(.03)** |

.18(.06)** |

| |

Standardized |

−.02(.01)** |

−.04(.01)** |

.07(.02)** |

| Household Income |

Unstandardized |

.01(.00)*** |

.01(.00)*** |

−.02(.01)** |

| |

Standardized |

.02(.01)*** |

.04(.01)*** |

−.06(.02)** |

*p < .05 (two-tailed). **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Female participants tended to have lower levels of anxious (b = −.02, p < .01) or avoidant adult attachment (b = −.04, p < .01), and higher levels of self-esteem (b = .07, p < .01). Individuals with higher household income reported higher levels of anxious adult attachment (b = .02, p < .001), avoidant adult attachment (b = .04, p < .001), and lower levels of self-esteem (b = −.06, p < .01).

Discussion

Although most existing literature predominantly focuses on revealing how the attachment style of the IPV perpetrators may influence their behavior (Velotti et al., 2018), our study contributes to the field by exploring the potential association between IPV victimization and adult attachment. Using a non-clinical sample, this study identified a positive association between IPV victimization and adult insecure attachment, including both anxious and avoidant dimensions. Meanwhile, a negative association was observed between IPV victimization and self-esteem. These findings concur with the tenets of attachment theory, which posits that individuals who experienced IPV would have a sense of betrayal of trust within intimate relationships. Rather than serving a secure attachment base in intimate adult relationships, IPV experience altered internal models of self as a victim and the other as perpetrator if the individuals stay in the abusive relationships for long enough (Levendosky et al., 2012). IPV survivors may adopt maladaptive coping strategies to mitigate the distress stemming from such intimate relationships. Consequently, these individuals might manifest anxious or avoidant attachment (Levendosky et al., 2012). At the same time, our results indicating reduced self-esteem among IPV victims resonates with previous studies, underscoring the detrimental effects of IPV on self-esteem (Childress, 2013; Karakurt et al., 2014). Enduring undeserved maltreatment from partners can persistently undermine an individual’s sense of self-efficacy and competency (Tariq, 2013).

Our findings do not identify childhood attachment as a significant moderating factor between IPV victimization and insecure attachment in adulthood. There is currently no study to compare with this finding, as the present study is the first to investigate the moderating role of childhood attachment on the relationship between adult IPV victimization and adult attachment.

Although previous research implied that childhood attachment can mitigate the adverse effects of IPV on psychological health and adult life satisfaction (Pang & Thomas, 2020), those studies assessed IPV experiences during an individual’s childhood. Nevertheless, we speculate that IPV targets an individual’s sense of security, which is predominantly influenced by adult romantic relationships (Dutton & White, 2012). This IPV-related sense of security distinguishes itself from childhood attachment, which primarily arises from interactions between parents and children. For instance, the fear associated with intimate relationships and feelings of betrayal, as a result of sustained physical and emotional abuse from an intimate partner, may not be readily alleviated by the sense of security instilled by one’s primary caregivers during childhood. Survivors who were abused by their partner may attempt to manage their distress by deactivating their attachment system, which would reflect more insecure working models of self and others, less self-confidence, and lack of trust in others (Kobayashi et al., 2021).

Conversely, our research determined that childhood attachment acts as a moderator between IPV victimization and self-esteem, aligning with previous studies showing parental support as a vital protective mechanism for the self-esteem of individuals subjected to interpersonal violence (Duru et al., 2019). As posited by attachment theory, secure childhood attachment fosters a robust self-concept, equipping individuals with the belief that they are valuable and deserving of love (Bowlby, 1969). This foundational belief may serve as an effective counterbalance, attenuating the damage to self-esteem precipitated by IPV. We acknowledge that although the moderating effect of childhood attachment on the relationship between IPV victimization and self-esteem was statistically significant, the magnitude standardized coefficients were fairly low. One possible explanation could be that when transitioning to adulthood, individuals expand their social relationships with their peers, romantic partners, and offspring, which may increasingly take on their attachment organizations (Allen et al., 2018; Guarnieri et al., 2015). Future studies could further explore the level of effectiveness of childhood attachment mitigating the negative impact of IPV experience on interpersonal and intrapersonal outcomes in adulthood.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the present study adds important contributions to the literature on IPV victimization and attachment, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the dichotomous question of IPV could not fully capture all of the complexity of IPV victimization experiences. Future research should consider other factors related to IPV, including severity of the violence, types of IPV, age of onset, frequency, and duration. Second, retrospective reporting of childhood attachment with the primary caregiver(s) may lead to bias, or distortion in the recall of traumatic events from family of origin. However, previous studies have shown that retrospective reports only have a small amount of bias and that it is not strong enough to invalidate the results for adverse childhood experiences (Hardt & Rutter, 2004).

A growing body of literature has identified adult attachment as a risk factor of IPV (Doumas et al., 2008); here, we were not able to determine the causal relationship between adult attachment and IPV. We did conduct a path analysis using childhood attachment and adult attachment to predict IPV and self-esteem, but the model did not demonstrate a good fit. It is possible that attachment and IPV do not have a simple causal relationship; other childhood trauma experiences may contribute to the complexity of the IPV (Li et al., 2019).

Finally, not knowing the types of attachment in childhood limited our exploration regarding the changes of attachment styles from childhood to adulthood. The cross-sectional design of assessing childhood attachment and adult attachment concurrently did not provide sufficient evidence to determine the cause and effect. Bowlby (1969) believed that there is a continuity between childhood attachment and adult attachment over the life course. An individual’s security in adult relationships may be a partial reflection of their experiences with primary caregivers in early childhood (Ammaniti et al., 2000). However, one of the common misconceptions about attachment theory is that attachment is always stable from infancy to adulthood (Hazan & Shaver, 1994). It is possible that adults’ attachment patterns would change if their relational experiences were disturbed by relational trauma such as IPV (West & George, 1999) or childhood trauma (Shen & Soloski, 2024), which partially explains that childhood attachment is not a significant moderator between IPV and adult attachment from our findings. Future research could conduct longitudinal studies to examine the changes of attachment and how childhood trauma and IPV influences attachment over time.

Implications

The findings of the present study provide insights that may inform clinical interventions for adult survivors who have experienced IPV to rebuild trusting interpersonal relationships and relationships with self. First, IPV experiences were significantly associated with anxious and avoidant adult attachment. During a traumatic experience, such as IPV, the attachment security system is activated, and survivors are in a surviving mode and tend to seek protection. Unfortunately, IPV involves power, control, and betrayal within an intimate relationship, which may damage internal working models of self and others if they stay for long enough (Levendosky et al., 2012). Thus, clinical interventions could focus on altering survivors’ negative internal working models to increase security within non-abusive close relationships. Close friends and family members could remain as a secure base for IPV survivors while they rebuild their personal and social lives that IPV have damaged. Additionally, therapeutic relationships could potentially serve as a secure base for survivors to explore their attachment behaviors. Survivors with avoidant attachment demonstrate deactivation attachment behaviors (Brenner et al., 2021), such as minimizing the impact of their trauma experiences, having a tendency to perceive and present themselves as strong, or avoiding discussing their trauma experiences to avoid the possible pain (Muller, 2009). Therefore, clinicians need to hold a safe space to challenge survivors with avoidant attachment to reactivate their attachment systems, such as by validating their avoidance and ambivalence or facilitating conversations to turn toward trauma-related experiences and emotions instead of turning away. Survivors with anxious attachment, on the other hand, demonstrate hyperactivation attachment behaviors, including fear of rejection and abandonment, hypersensitivity to and preoccupation with relationships and intimacy, utilization of negative emotional regulation strategies, as well as difficulties with leaving abusive relationships (Kural & Kovacs, 2022; Velotti et al., 2018). Clinicians could teach anxious-attached survivors some effective coping strategies, including self-regulation skills, creating boundaries, establishing safety plans, maintaining relationships with others, and increasing self-compassion (Rizo et al., 2017), which may help them to perceive themselves as worthy, lovable, and less dependent on others.

Furthermore, group counseling is a powerful way to learn about trusting oneself and others and to improve interpersonal relationship skills. Clients’ attachment patterns will be activated through interactions with the group members and the facilitators. Clients with anxious attachment tend to react to group members’ rejections, while clients with avoidant attachment tend to demonstrate withdrawal behaviors (e.g., disengagement; Zorzella et al., 2014). Therefore, when working with these clients, clinicians should stimulate the change of internal working models by using the group as a secure base to foster corrective emotional exchanges that challenge group members’ maladaptive beliefs about themselves and others (Marmarosh et al., 2013).

One of the important findings of the current study is that childhood attachment with the primary caregiver(s) buffered the relationship between IPV and self-esteem. From a clinical point of view, the result may bring hope for adult survivors of interpersonal violence regarding their healing process; primary caregivers could still serve as a secure base to offer a crucial opportunity to strengthen the internal working models that would positively affect later adjustment. Counselors could assess survivors’ attachment with their primary caregivers and give them autonomy to determine if it is beneficial to get their non-abusive primary caregivers involved in the treatment to provide support. Although the moderation result from the present study was statistically significant, the magnitude of moderating effect was small. During adulthood, individuals expand their relationship networks with their peers (e.g., friends) and romantic partners, as these relationships become more central in their daily life (Guarnieri et al., 2015). Therefore, the effectiveness of childhood attachment mitigating the adverse effect of IPV in adulthood clinically needs to be further investigated.

Conclusion

The present study empirically examines the moderation role of childhood attachment on the association between IPV, adult attachment, and self-esteem. Specifically, we found that childhood attachment was a significant moderator buffering the relationship between the experience of IPV and self-esteem. A theoretical and empirical understanding of the role of attachment in the context of IPV has implications for researchers and clinicians working with survivors and their families.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 1012–1028.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x

Allen, J. P., Grande, L., Tan, J., & Leob, E. (2018). Parent and peer predictors of change in attachment security from adolescence to adulthood. Child Development, 89(4), 1120–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12840

Ammaniti, M., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Speranza, A. M., & Tambelli, R. (2000). Internal working models of attachment during late childhood and early adolescence: An exploration of stability and change. Attachment & Human Development, 2(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730010001587

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M. R. (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss, Vol. 2: Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

Bradshaw, C. P., & Garbarino, J. (2004). Social cognition as a mediator of the influence of family and community violence on adolescent development: Implications for intervention. In J. Devine, J. Gilligan, K. A. Miczek, R. Shaikh, & D. Pfaff (Eds.), Youth violence: Scientific approaches to prevention (pp. 85–105). New York Academy of Sciences.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford.

Brennan, K. A., & Morris, K. A. (1997). Attachment styles, self-esteem, and patterns of seeking feedback from romantic partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297231003

Brenner, I., Bachner-Melman, R., Lev-Ari, L., Levi-Ogolnic, M., Tolmacz, R., & Ben-Amitay, G. (2021). Attachment, sense of entitlement in romantic relationships, and sexual revictimization among adult CSA survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(19–20), NP10720–NP10743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519875558

Burke, J. G., Thieman, L. K., Gielen, A. C., O’Campo, P., & McDonnell, K. A. (2005). Intimate partner violence, substance use, and HIV among low-income women: Taking a closer look. Violence Against Women, 11(9), 1140–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801205276943

Cherrier, C., Courtois, R., Rusch, E., & Potard, C. (2023). Parental attachment, self-esteem, social problem-solving, intimate partner violence victimization in emerging adulthood. The Journal of Psychology, 157(7), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2023.2242561

Childress, S. (2013). A meta-summary of qualitative findings on the lived experience among culturally diverse domestic violence survivors. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(9), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.791735

Doumas, D. M., Pearson, C. L., Elgin, J. E., & McKinley, L. L. (2008). Adult attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: The “mispairing” of partners’ attachment styles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(5), 616–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260507313526

Duru, E., Balkis, M., & Turkdoğan, T. (2019). Relational violence, social support, self-esteem, depression and anxiety: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2404–2414.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01509-2

Dutton, D. G., & White, K. R. (2012). Attachment insecurity and intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.07.003

Gamble, S. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2005). Adolescents’ perceptions of primary caregivers and cognitive style: The roles of attachment security and gender. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29, 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-005-3160-7

Gilbert, L. K., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M., & Kresnow, M. (2023). Intimate partner violence and health conditions among U. S. adults—National Intimate Partner Violence Survey, 2010–2012. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 237–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221080147

Gomez, R., & McLaren, S. (2007). The inter-relations of mother and father attachment, self-esteem and aggression during late adolescence. Aggressive Behavior, 33(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20181

Gormley, B., & Lopez, F. G. (2010). Psychological abuse perpetration in college dating relationships: Contributions of gender, stress, and adult attachment orientations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(2), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509334404

Guarnieri, S., Smorti, M., & Tani, F. (2015). Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Social Indicators Research, 121(3), 833–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0655-1

Hardt, J., & Rutter, M. (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1994). Deeper into attachment theory. Psychological Inquiry, 5(1), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0501_15

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Jewkes, R., Fulu, E., Tabassam Naved, R., Chirwa, E., Dunkle, K., Haardörfer, R., Garcia-Moreno, C., & the UN Multi-country Study on Men and Violence Study Team. (2017). Women’s and men’s reports of past-year prevalence of intimate partner violence and rape and women’s risk factors for intimate partner violence: A multicountry cross-sectional study in Asia and the Pacific. PloS Medicine, 14(9), e1002381. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002381

Karakurt, G., Koç, E., Katta, P., Jones, N., & Bolen, S. D. (2022). Treatments for female victims of intimate partner violence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 793021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.793021

Karakurt, G., Smith, D., & Whiting, J. (2014). Impact of intimate partner violence on women’s mental health. Journal of Family Violence, 29(7), 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9633-2

Kobayashi, J. E., Levendosky, A. A., Bogat, G. A., & Weatherill, R. P. (2021). Romantic attachment as a mediator of the relationships between interpersonal trauma and prenatal representations. Psychology of Violence, 11(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000361

Kural, A. I., & Kovacs, M. (2022). The role of anxious attachment in the continuation of abusive relationships: The potential for strengthening a secure attachment schema as a tool of empowerment. Acta Psychologica, 225, 103537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103537

Levendosky, A. A., Lannert, B., & Yalch, M. (2012). The effects of intimate partner violence on women and child survivors: An attachment perspective. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 40(3), 397–433.

https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2012.40.3.397

Li, S., Zhao, F., & Yu, G. (2019). Childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.012

Lindgren, M. S., & Renck, B. (2008). “It is still so deep-seated, the fear”: Psychological stress reactions as consequences of intimate partner violence. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(3), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01215.x

Lopez, F. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). Dynamic processes underlying adult attachment organization: Toward an attachment theoretical perspective on the healthy and effective self. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.3.283

Marmarosh, C. L., Markin, R. D., & Spiegel, E. B. (2013). Attachment in group psychotherapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14186-000

Matheson, F. I., Daoud, N., Hamilton-Wright, S., Borenstein, H., Pedersen, C., & O’Campo, P. (2015). Where did she go? The transformation of self-esteem, self-identity, and mental well-being among women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Women’s Health Issues, 25(5), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.04.006

McClure, M. M., & Parmenter, M. (2020). Childhood trauma, trait anxiety, and anxious attachment as predictors of intimate partner violence in college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(23–24), 6067–6082. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517721894

McLaughlin, J., O’Carroll, R. E., & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Intimate partner abuse and suicidality: A systemic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(8), 677–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.08.002

Meeker, K. A., Hayes, B. E., Randa, R., & Saunders, J. (2020). Examining risk factors of intimate partner violence victimization in Central America: A snapshot of Guatemala and Honduras. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 68(5), 468–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X20981049

Moretti, M. M., & Peled, M. (2004). Adolescent-parent attachment: Bonds that support healthy development. Paediatrics & Child Health, 9(8), 551–555. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/9.8.551

Muller, R. T. (2009). Trauma and dismissing (avoidant) attachment: Intervention strategies in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015135

Pang, L. H. G., & Thomas, S. J. (2020). Exposure to domestic violence during adolescence: Coping strategies and attachment styles as early moderators and their relationship to functioning during adulthood. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 13(2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00279-9

Ponti, L., & Tani, F. (2019). Attachment bonds as risk factors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1425–1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01361-4

Rizo, C. F., Givens, A., & Lombardi, B. (2017). A systematic review of coping among heterosexual female IPV survivors in the United States with a focus on the conceptualization and measurement of coping. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.03.006

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. Basic Books.

Sayed, S., Iacoviello, B. M., & Charney, D. S. (2015). Risk factors for the development of psychopathology following trauma. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17, 70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0612-y

Scott, S., & Babcock, J. C. (2010). Attachment as a moderator between intimate partner violence and PTSD symptoms. Journal of Family Violence, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9264-1

Shen, F., Liu, Y, & Brat, M. (2021). Attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress: A multiple-mediator model. The Professional Counselor, 11(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.15241/fs.11.2.129

Shen, F., & Soloski, K. L. (2024). Examining the moderating role of childhood attachment for the relationship between child sexual abuse and adult attachment. Journal of Family Violence, 39, 347–357.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00456-9

St. Vil, N. M., Carter, T., & Johnson, S. (2021). Betrayal trauma and barriers to forming new intimate relationships among survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7–8), NP3495–NP3509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518779596

Sutton, T. E. (2019). Review of attachment theory: Familial predictors, continuity and change, and intrapersonal and relational outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2018.1458001

Tariq, Q. (2013). Impact of intimate partner violence on self esteem of women in Pakistan. American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.11634/232907811604271

Velotti, P., Beomonte Zobel, S., Rogier, G., & Tambelli, R. (2018). Exploring relationships: A systematic review on intimate partner violence and attachment. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01166

West, M., & George, C. (1999). Abuse and violence in intimate adult relationships: New perspectives from attachment theory. Attachment & Human Development, 1(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616739900134201

Wilkinson, R. B. (2004). The role of parental and peer attachment in the psychological health and self-esteem of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048063.59425.20

Zorzella, K. P. M., Muller, R. T., & Classen, C. C. (2014). Trauma group therapy: The role of attachment and therapeutic alliance. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 64(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2014.64.1.24

Fei Shen, PhD, LMFT, is an assistant professor at Kean University. Ying Zhang, PhD, is an assistant professor at Clarkson University. Xiafei Wang, PhD, is an assistant professor at Syracuse University. Correspondence may be addressed to Fei Shen, 1000 Morris Ave., Union, NJ 07083, fshen@kean.edu.

Dec 5, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 3

Russ Curtis, Lisen C. Roberts, Paul Stonehouse, Melodie H. Frick

Tattoo art is one of the earliest forms of self-expression, but the advent of colonialism, and its accompanying religious convictions, halted the practice in many Indigenous lands and led to widespread bias against tattooed people—a bias maintained to the present. How might the counseling profession respond to this residual bias and intentionally invoke a cultural shift destigmatizing tattoos? Through an extensive literature review, this article provides a more comprehensive understanding of tattoo-related mental health correlates, biases, and theories that enhance the effectiveness of counseling and parallel trends in the counseling profession that emphasize sociocultural influences on wellness. As a result of this survey, the authors propose a new theory of tattoo motivation, the unencumbered self theory of tattoos, which advances existing tattoo theory and aligns with current counseling trends by postulating that tattoos symbolize the uniquely human desire to transcend norms and laws imposed by external influences.

Keywords: tattoo, bias, mental health, theory, counseling

Imagine you are the parent of a 13-year-old girl. While at a parent–teacher conference, you learn your daughter is struggling with disruptive behavior and angry outbursts during class. The teacher asks if you would support your daughter seeing the school counselor and adds that the counselor is in the school building and available to speak with parents. You approach the counselor’s office, gently knock, and are welcomed by a warm, feminine-presenting adult. As the counselor offers their hand to shake, you notice an entirely tattooed forearm, and as you greet their eyes, more ink is evident on their neck.

What feelings, assumptions, or concerns emerge as you put yourself in the place of the parent in the above vignette? Despite the recent popularization of tattoos, a bias remains. Current research indicates that nearly half of adults in the United States between the ages of 18–34 have at least one tattoo (Roggenkamp et al., 2017), and the tattoo business is one of the fastest-growing enterprises, producing over a billion dollars in annual revenue (Zuckerman, 2020). This trend in tattoo art transcends the United States and is evident throughout the world (Ernst et al., 2022; Khair, 2022; Roberts, 2016). Nevertheless, bias against tattooed people remains, and women and people of color receive the brunt of this discrimination (Baumann et al., 2016; Guéguen, 2013; Kaufmann & Armstrong, 2022; Khair, 2022; Roberts, 2016). Given this meteoric resurgence in tattoo art and the discrimination that clings to it, implications for counseling practice inevitably exist.

Professional questions relevant to the counseling practice include: Is there a relationship between a desire for a tattoo and mental health? What motivates a person to seek a tattoo? In what ways may a tattoo bias subconsciously shape a counselor’s interactions with a client? How might the counseling community communicate a spirit of inclusion to the tattooed? To address these questions, this article employs the following structure. First, we provide a context for this bias by briefly examining the history and cultural perspectives of tattoos. Second, to establish the importance of this issue, we empirically demonstrate the reality of tattoo bias. Third, with this history of bias in mind, we comb the literature for research that explores the relationship between mental health and tattoos. Fourth, these relationships offer a frame of reference for our survey of established tattoo motivation theories, to which we propose an additional theory, the unencumbered self theory of tattoos, and reveal its significance within a clinical setting via a case study. Fifth, before concluding the article, we demonstrate how our inquiry’s content might be applied by enumerating our argument’s implications for the counseling profession.

Historical and Cultural Perspectives of Tattoos

The word tattoo originates from the Samoan term tatau, meaning “to tap lines on the body.” The practice of tattooing is known to have existed as early as 7000 BC, as seen on Egyptian mummies (Rohith et al., 2020). Otzi the Ice Man, dating back to 3000 BC, was discovered in 1991 with tattoos on his arms and wrist that are thought to have been applied for therapeutic purposes, a potential precursor to acupuncture (Schmid, 2013). Prior to the colonization of Indigenous lands by European countries, many tribes practiced the art of tattoo to symbolize adulthood, tribal membership, and status (Dance, 2019; Thomas et al., 2005). However, with the emergence of European imperialism, colonizers taught Indigenous people that tattoos were an abomination, scripturally prohibited, and therefore immoral. For instance, in The Holy Bible (New International Version, 1978, Leviticus 19:28) and The Qur’an (2004, Surah 7:46), specific passages forbid marking the skin.

Despite these condemnations, the practice of tattooing was not eradicated. Many cultures continued their tattoo traditions, and modern culture has adopted new traditions, which are even now expanding throughout the world (Ernst et al., 2022; Khair, 2022; Roberts, 2016). Although there is much intergroup variability, cultural identity can influence the motivation for and type of preferred tattoo. In India, for instance, tattoos often depict unique patterns specific to different tribal regions in the country. Specifically, in urbanized Indian geographic areas, there is increasing integration of tribal pattern tattoos with Western-influenced designs (Rohith et al., 2020). In Samoan culture, men receive an intricate tattoo called a pe’a while women receive a malu, both to indicate maturity (Dance, 2019). Lest the cultural importance of Indigenous tattoos be doubted, their misappropriation has resulted in litigation, thereby challenging attorneys to consider the property rights of tattoo designs (Tan, 2013).

Profoundly relevant to counseling, tattoos are often representational and symbolize something of importance. In a recent qualitative study of tattooed Middle Eastern women, Khair (2022) discovered themes related to taking ownership of their bodies in a patriarchal society and symbolism of their strength and desire to break free of patriarchal rules and religious mandates. In the United States, a study of mixed-race Americans’ tattoos revealed the most common tattoo themes include animal images and text of personally meaningful messages (Sims, 2018). In yet another group, White supremacists often get swastikas, crossed hammers, Confederate flags, and embellished Celtic crosses (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2006). Similarly, in Czech Republic prisons, the skull tattoo is a symbol representing neo-Nazi extremism, which then informs prison officials of inmates potentially becoming radicalized (Vegrichtová, 2018).

Exploring the intersection of religion and tattoos, Morello’s (2021) qualitative analysis of 21 people in three South American cities revealed that tattoos were more accepted among Catholics than evangelicals. Explained below, Morello classified the types of Christian tattoos as reversal, devotional, foundational, and then a nonreligious fourth category termed relational. According to participants, reversal tattoos symbolized regaining control of disempowering events, such as when Christians historically tattooed themselves to show Roman enslavers their devotion to Christ. Devotional tattoos were comprised of images and symbols representing religious themes (e.g., a cross), often used as a source of strength and identity. Foundational tattoos represent significant moments in life, such as major life transitions (e.g., the date of one’s conversion) or mystical experiences. Morello’s last category is akin to devotional tattoos, but the relational category was created to represent devotion to loved ones, such as images or symbols of one’s children.

In a related study examining the beliefs of religious women with and without tattoos, Morello et al. (2021) identified several common themes. This mixed methods study of 48 women in a conservative Christian college indicated that tattoos were not considered taboo by their religious friends and family and that tattooed participants spent considerable time determining which tattoo to receive. Predominant reasons for obtaining tattoos included social justice, friendship, and spiritual values. Summarizing previous research, individuals primarily choose tattoos to express their identity and uniqueness or to take ownership of their bodies. However, as discussed in the following section, there exists a bias against tattooed individuals.

Tattoo Bias

Unfortunately, with any practice that diverges from dominant cultural values, there is bias (Broussard & Harton, 2018). Although evidence indicates less discrimination against tattoos in the 21st century, negative judgments still exist explicitly and implicitly (Broussard & Harton, 2018; Williams et al., 2014; Zestcott et al., 2018). For example, Kaufmann and Armstrong (2022) found that law enforcement and the medical community hold negative sentiments toward tattooed people. They found that medical professionals who expressed negative judgments about their tattooed patients were likely to have patients not return. In fact, patients reported better rapport and increased trust with medical professionals who asked about the meaning of their tattoos. In other words, negative judgment toward, and lack of acknowledgment of, tattoos were detrimental to building the trust needed to provide optimal and consistent care (Kaufmann & Armstrong, 2022).

Unjustly, women and people of color with tattoos experience more significant discrimination than men or White people (Baumann et al., 2016; Camacho & Brown, 2018; Guégen, 2013; Solanke, 2017). For example, women encounter prejudice when failing to gain employment due to having visible tattoos regardless of having excellent job qualifications (Al-Twal & Abuhassan, 2024; Henle et al., 2022). Moreover, women of color have experienced job discrimination by being questioned if they have visible or nonvisible tattoos (i.e., inkism), being forbidden from having or being required to cover tattoos regardless of cultural relevance (e.g., covering a traditional Māori tattoo), or being required to prove that they do not have tattoos—as alleged in a legal complaint against a Singaporean airline that required female attendants to wear a swimsuit and demonstrate to their employers that they did not have tattoos (Solanke, 2017, Chapter 8). Women with tattoos also experience ambivalent sexism due to rejecting the feminine apologetic (i.e., not acting or dressing in stereotypical feminine ways); they are also perceived as wanting attention and sexually promiscuous (Heckerl, 2021). For instance, Guéguen (2013) found that women on the beach displaying a lower-back butterfly tattoo were significantly more likely to be approached by men compared to women without the tattoo, and the men interviewed indicated that they thought they had a better chance of getting a date and having sex with the tattooed women than the nontattooed women (Guéguen, 2013). In other words, men in this study had the biased perception that women with tattoos were more sexually promiscuous than nontattooed women.

This bias appears within incarceration rates as well. In a study conducted by Camacho and Brown (2018), they found that arrestees with neck tattoos were more likely to receive felony charges specifically for larceny offenses. Among these groups, Black individuals with neck tattoos were more likely than others to face felony charges (Camacho & Brown, 2018). It is also noteworthy that law enforcement catalog the tattoos of arrestees in the Registry of Distinct Marks (Miranda, 2020), which is kept in their permanent record and could potentially bias future incarceration and convictions due to the criminogenic stigmatization of individuals with tattoos (Martone, 2023; Rima et al., 2023).

Neck tattoos specifically appear to elicit bias (Baumann et al., 2016). Given two sets of photos of male and female faces, with a neck tattoo and without a visible tattoo, participants were asked to choose among the photos that they would most like to have as their surgeon. In a separate condition, participants were asked to choose who they would most like to have as their car mechanic. In both experiments, participants preferred to have a nontattooed person as their surgeon or mechanic. However, the preference was more substantial for a nontattooed surgeon than a nontattooed mechanic. Female participants assessed the tattooed faces more positively than male participants, but still preferred the nontattooed faces (Baumann et al., 2016).

Roberts (2016) suggested that although tattoos are becoming more prevalent worldwide, they are not yet entirely accepted. As such, employment discrimination occurs for people with visible tattoos. Roberts (2016) suggested employers discriminate primarily because of the fear of customer complaints and the concomitant loss of business. They further suggested that small businesses in rural areas, which tend to be more conservative, may be even more likely to refuse employment to tattooed workers.

Clients’ Perception of Tattooed Counselors

To date, very few published studies examine the perceptions of tattoos within the mental health professional arena. One exception, however, is a recent publication examining the perception of potential mental health clients of psychologists with or without tattoos. Zidenberg et al. (2022) recruited 534 participants to determine if there were negative perceptions of psychologists who had tattoos. First, participants were presented with a mock profile of a fictional clinical psychologist. Each participant was randomly assigned to view one of three images of the psychologist: with no tattoo, a neutral tattoo (a flower), or a provocative tattoo (a skull with flames). Participants then rated the counselor on perceived competence and their personal feelings toward her.

Contrary to the researchers’ initial expectations, the psychologist’s photo with the provocative tattoo was rated more likable, interesting, and confident and less lazy than the psychologist with a neutral or no tattoo. Interestingly, the psychologist’s photo without a tattoo was rated as more professional, but this did not equate to participants’ believing that the psychologist would thus provide better care. The researchers speculated that while nontattooed people are viewed as more professional, they are not necessarily who clients believe will give the best mental health care. They further hypothesized that professionalism may convey a bias of being “better than” the clients and thereby might be perceived as less authentic. Moreover, participants in this study believed they would get better help from a more “authentic” psychologist, and that the provocative tattoo communicated a sense of authenticity (Zidenberg et al., 2022).

Mental Health and Tattoos

Although early studies (e.g., Grumet, 1983) concluded that tattoos were a sign of maladjustment, contemporary research indicates that tattooed people are as healthy as nontattooed people (Mortensen et al., 2019; Pajor et al., 2015). In general, today the mere presence of a tattoo is not correlated with mental or behavioral issues (Roggenkamp et al., 2017). In fact, most people in many cultures conscientiously obtain tattoos to express themselves and honor people and causes they deeply care about (Khair, 2022; Naudé et al., 2019; Shuaib, 2020). Nevertheless, in one study of a German community (N = 1,060), which sampled people aged 14–44, 40.6% who reported childhood abuse or neglect had at least one tattoo, compared to 29.4% tattooed participants who reported no significant abuse (Ernst et al., 2022). However, Ernst et al. (2022) cautioned that the mere presence of a tattoo is not perfectly correlated with childhood abuse. Aesthetic embellishment of the body is the most common reason for getting tattoos, and it should not be considered an automatic indication of childhood abuse (Ernst et al., 2022).

Evidence suggests that the number of tattoos as well as their placement and content better indicate potential maladjustment than the mere presence of an easily concealed tattoo. Specifically, Mortensen et al. (2019) found that participants (N = 2008 adults) who had four or more tattoos were 15.4% more likely to report having been diagnosed with a mental health problem compared to 5.8% of participants with only one tattoo. Further, 13.4% of the participants with visible tattoos reported having a mental health diagnosis, and 28.2% of the participants who self-reported having an offensive tattoo also reported having a mental health diagnosis. In other words, multiple and visible tattoos may be more closely correlated with mental and behavioral issues than the mere presence of tattoos. However, contrary to Mortensen et al. (2019), in their study of life satisfaction with a sample of 449 participants (16–58 years old), Pajor et al. (2015) used the Multidimensional Self-Esteem Inventory (MSEI; O’Brien & Epstein, 1988), a psychological assessment tool with 116 items graded on a 5-point scale and designed to measure various aspects of self-esteem. Results indicated that tattooed people reported significantly higher competence than nontattooed: 37.2 versus 33.6 (p < .001). Tattooed participants also scored significantly higher on a measure of personal power, 35.6 versus 33.5 (p < .01), and significantly lower scores on a measure of anxiety and insomnia, 1.50 versus 1.75 (p < .05). Thus, although numerous visible tattoos could potentially indicate mental or behavioral issues, the research is not conclusive, suggesting the need for counselors to open-mindedly assess each client’s motivations for obtaining tattoos.

Contrary to previous hypotheses, tattoos are rarely a form of self-harm (i.e., cutting, self-mutilation). For example, Aizenman and Jensen (2007) analyzed a sample of college students (N = 1,330; ages 17–39) to determine mental health differences between students who self-injure and those with tattoos. The majority of tattooed students reported receiving tattoos as a way to express their individuality, while students who self-injured were motivated by feelings of insecurity and loss of control. Participants also completed assessments measuring depression and self-esteem. In terms of general wellness, the self-injury group (no tattoos) reported higher mean depression scores compared to both the tattoo group’s score and the nontattooed (no self-injury) score. The self-injury group also reported lower mean self-esteem scores compared to both the tattooed and the nontattooed groups. Noteworthy is the fact that there was no significant difference between the tattooed and nontattooed groups in terms of depression and self-esteem, which further suggests that tattooed college students are no more likely to experience mental health issues than nontattooed college students.

In a more recent study to determine whether tattooing was a form of self-injury, Solís-Bravo et al. (2019) found that from a sample of 438 adolescent males, 11.5% reported engaging in nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), but only 1.8% indicated receiving a tattoo with the explicit intention of feeling pain. However, they also found that 62.5% of the students with tattoos self-injured compared to 10.6% of students without tattoos. Thus, with this small subsample of tattooed NSSI students, it was suggested that tattooed adolescents should be screened for potential mental health issues. Yet, considering that only eight students in this sample reported getting a tattoo to feel pain, further replication of this work is needed before confirming a conclusive relationship between tattoos and NSSI (Solís-Bravo et al., 2019).

Exploring the correlation between tattoos and premature mortality (e.g., violent death, drug overdose), Stephenson and Byard (2019) found that there was a trend for people with tattoos to die at a younger age and to experience an unnatural death compared to nontattooed people. However, these results were not statistically significant, indicating that there was no meaningful difference between age and cause of death between tattooed and nontattooed people.

More contemporary research examined the relationship between body image and tattoo acquisition (Jabłońska & Mirucka, 2023). Using a sample of 327 Polish tattooed women to examine a relationship between body image and tattoos, 45.26% reported acceptance of their appearance and a deep connection to their bodies. Researchers speculated that they received tattoos as a way to adorn their bodies and express their individuality. Another 36% reported an unstable body image, meaning they perceived both positive and negative aspects of their bodies. It was speculated that this group used tattoos to conceal perceived flaws. The remaining 18.65% held a negative body image. Although the majority of their sample held either positive or mixed body image estimations, the researchers’ speculation as to why subjects received tattoos makes it difficult to infer correlation between tattoos and well-being. Nevertheless, nearly half the sample reported appreciation for their bodies and a desire to accentuate their positive self-image with body art.

Relatedly, some trauma survivors get tattoos to symbolize what they experienced and how they have grown (Crompton et al., 2021). The semicolon is one example of this, indicating that while one life chapter may have been traumatic, that is not the end of the story. Using tattoos to navigate trauma is further supported by Kidron (2012), who noted that some descendants of Holocaust survivors replicated the number tattoo on their arms to illustrate the connection to their grandparent, redefining the tattoos from markers of trauma to markers of survival and expanding their interfamilial bond and cultural identity.

In summary, studies indicate that the mere presence of a tattoo is not significantly correlated with mental or behavioral issues. Counselors should avoid assuming that tattooed clients have mental health issues, even if multiple visible tattoos are sometimes linked with adverse health outcomes or behaviors. Because tattoos are so often attached to identity, body image, and important life events, counselors should thoroughly explore with clients why they obtained such tattoos and what they symbolize. In order to assist with such exploration, the next section identifies a number of recognized tattoo motivation theories.

Tattoo Motivation Theories

To determine effective strategies to reduce tattoo bias and counsel tattooed clients, it is important to understand the motivations and theoretical premises of why people get tattoos. This section describes recognized tattoo motivation theories. Recent findings in tattoo research cited within this article highlight the limitations of these theories and prompted us to propose our own, the unencumbered self theory of tattoos, which focuses on sociocultural influences. From this new perspective, we hope counselors will have a clearer understanding of the motivations behind getting a tattoo, which will in turn increase understanding of tattoo culture and what this implies about clients and counseling practice. To illustrate how these theoretical models might be of use in a clinical setting, in the subsequent section we provide a case study in which we discuss, compare, and contrast theories and exemplify the need for a new understanding of tattoo motivation.

Psychodynamic Theory of Tattoo

The first hypothesis for tattooing is rooted in psychodynamic theory. This theory posits that tattoos are an outward manifestation of intrapersonal conflict or unresolved psychological concerns (Grumet, 1983; Karacaoglan, 2012; Lane, 2014). The belief is that permanent skin marking serves as a visible mnemonic that prompts a defense mechanism that helps alleviate the anxiety caused by conflict within the id, ego, and superego. In other words, the symbolism embodied within the marking of the skin iteratively releases blocked psychic energy, causing temporary relief from various difficult symptoms.

Psychodynamic theory is problematic because it fails to address the alternative motivations for getting tattoos, namely, the aforementioned social–cultural perspective. Moreover, Freud’s psychoanalytic approach is rooted in Western civilization’s understanding of internal processes and is therefore heavily influenced by a European, White, male perspective of psychic processes, thus ignoring the effects of oppression and inequality on personal identity, mental health, and behavior. As was indicated in the previous research review, and as we will see in subsequent sections, current tattoo research does not support the notion that tattoos are merely the result of unconscious conflict.

Human Canvas and Upping the Ante Theories of Tattoo

Moving beyond the arguably deficit ideology of the psychodynamic theory of tattoos, Carmen et al. (2012) proposed two evolutionary theories of tattoo motivation that transcend obvious reasons like self-expression and group membership. The first theory, human canvas, argues that it is our innate longing to express the most authentic desires of our psyche through symbolic thought, originally on cave walls and later on our bodies. Their second theory, upping the ante, postulated that with increasing longevity and improved health care, the opportunities for attracting mates are more competitive, and people must devise new ways to stand out to attract mates, much like a peacock spreading its feathers.

The human canvas and upping the ante theories of tattoos are at least to some degree supported by current research (e.g., Wohlrab et al., 2007), and both theories advance our understanding of the motivation behind tattoos beyond psychodynamic theory. Indeed, people spend considerable time and thought choosing their tattoos for personal self-expression (Kaufmann & Armstrong, 2022) and to symbolize cultural traditions, sexual expression, and the love of art (Wohlrab et al., 2007). Although these theories advance tattoo theory, they fail to consider the even deeper meaning which suggests that tattoos are a way to regain bodily control and express displeasure with mandated values imposed by external influences. In essence, it is clear that tattoos are a form of self-expression, potentially to increase personal uniqueness and attractiveness, but this fails to explain what people are hoping to express. Thus, informed by contemporary tattoo research, we propose a new and expanded theory that attempts to explain the rationale behind tattoo acquisition through a wider societal lens.

The Unencumbered Self Theory of Tattoo

The unencumbered self theory of tattoos advances existing tattoo theory and aligns with current counseling trends by postulating that tattoos symbolize the uniquely human desire to transcend norms and laws imposed by external influences such as imperialism. After an exhaustive review of the tattoo literature, it is evident that the motivation to reclaim personal power from oppressive systems is one reason some people get tattoos, and this motivation is not explicitly stated within existing theories. While most closely aligned with the human canvas theory, the unencumbered self theory of tattoos differs in one subtle but essential way. The human canvas theory postulates that tattoos are a general form of self-expression (e.g., hobbies, memorials, identity, individuality). At the same time, the unencumbered self theory of tattoos suggests that specific individuals acquire tattoos as a deliberate assertion of autonomy and a repudiation of arbitrary societal norms. Take, for example, a client of Cherokee heritage who gets a tattoo depicting Cherokee syllabary. The human canvas theory would hold that this tattoo is motivated by the client’s desire to identify with her cultural heritage. The unencumbered self theory of tattoos acknowledges her desire to identify with her cultural heritage, but this desire is motivated by the need to disengage from the oppressive systems that successfully squelched her people’s values for so long.