Sep 4, 2014 | Article, Volume 2 - Issue 1

Keith Morgen, Geri Miller, LoriAnn S. Stretch

This article addresses the obstacles of effectively integrating addiction counseling into a nationwide definition of professional counseling scope of practice. The article covers an overview of issues, specific licensure and credentialing frameworks (LPC, CADC, LCADC) in two U.S. states, and recommendations to effectively bridge the gap between professional and addiction counseling. Historical origins and an overview of addiction counseling are presented.

Keywords: addiction, licensure, credentialing, LPC, CADC, LCADC

The question of professional identity within the counseling profession, first considered during the founding of the American Personnel and Guidance Association (Sweeney, 1995), still exists today (Calley & Hawley, 2008; Cashwell, Kleist, & Schofield, 2009; Mellin, Hunt, & Nichols, 2011; Myers, Sweeney, & White, 2002; Nassar-McMillan & Niles, 2011; Remley & Herlihy, 2009). One possible reason for the continual debate around professional identity may lie in the multitude of specialty fields (e.g., addiction, career, and school) within counseling (Gale & Austin, 2003; Myers, 1995; O’Brien, 2010). Remley (1995) underscores that unlike psychology, psychiatry and social work, counseling is the only mental health profession that licenses specialty areas. Specialty areas such as career and school counseling only denote a practice area or population; whereas addiction counseling actually entails a DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorder (i.e., Substance Use Disorders; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). No other Axis I or Axis II disorder receives such attention.

Addiction is considered a part of professional counseling as implied by the latest CACREP standards (2009). However, a separate licensure track exists for the profession of addiction counseling. If the practice of addiction counseling really is a part of counseling (as implied by the latest 2009 CACREP standards), then the time has come to recalibrate the rest of the counseling profession to better fit an inclusive and unifying professional counseling identity that includes addiction counseling. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to start the dialogue regarding the mixed messages on the issue of counselor identity and specialization for addiction counseling (Morgen, Miller, Culbreth, & Juhnke, 2011; Tabor, Camisa, Yu, & Doncheski, 2011). The article is divided into an overview of issues, specific licensure and credentialing frameworks in two sample states (New Jersey and North Carolina), and recommendations in response to the concerns discussed.

Overview of Issues

Henriksen, Nelson, and Watts (2010) criticize the counseling specialty system by arguing that counseling specialties do not define counseling but merely denote a practice area, and that counseling specialty licensure/credentialing implies that only a small proportion of the counseling profession is qualified to work with this population. The addiction area is one such area of specialization that comes with a separate licensure/credentialing process. The authors believe that in regard to addiction counseling, the additional supervisory and training hours required for addiction licensure/credentialing (in addition to the supervisory and training hours required for licensure as a professional counselor) implies that addiction content falls outside the professional counseling scope of practice.

For instance, if the graduate counseling program does not possess an addiction track, a cursory review of curriculum at CACREP and non-CACREP programs found the typical option of one addiction course as an elective. However, curricular reviews of numerous programs find few to no electives on other DSM-IV-TR disorders (e.g., mood, anxiety). Thus, the authors argue this produces a confusing mixed message in that licensure as a professional counselor covers practice areas that typically receive minimal exclusive attention (e.g., one-week discussion on anxiety disorders in a maladaptive behavior course), yet an area where one (or more) electives are typically offered for in-depth study of a disorder (such as addiction) comes with an entirely unique and separate licensure process.

The presence of a separate licensure/credentialing process for addiction counseling seems antiquated considering the extensive training required for a graduate counseling degree. Furthermore, most states consider addiction work within the professional counselor scope of practice (Tabor et al., 2011). Thus, the pioneering issue this paper addresses is whether it is time to thoughtfully reconsider how addiction is conceptualized in professional counseling (beyond the inclusion in the most recent CACREP standards) and recalibrate the education and licensure processes accordingly. In order to begin this dialogue a brief review of the history of the licensure/credentialing process of addiction counselors needs to be provided.

Historical Origins of the Issue

Historically across most states, the advent of addiction counseling licensure/credentialing standards occurred parallel with the professionalization of the counseling field (i.e., the master’s-level state licensure laws). States mandated that graduate school-level professionals conduct counseling, leaving many long-time and effective addiction counselors (many of whom possessed only a high school diploma or GED) out of the counseling mainstream. Consequently, addiction licensure/credentialing boards were established to achieve two goals. The first goal was to professionalize the addiction counseling field in a manner similar to professional counseling via mandated supervised practice hours and education across a subscribed addiction curriculum. The second goal was to provide a mechanism to grandfather into the profession those addiction counselors who had long worked in the field and provided outstanding services. Without the grandfather clause, many of these addiction counselors would have lost their profession or would have needed to put their career on pause as they obtained the required education and/or training.

The professionalization of addiction counseling, including licensure and credentialing, strengthened the field and provided a higher quality of care to those struggling with addiction. Unfortunately, a system also was established that over 30 years reinforced the notion that addiction falls outside the scope of practice for professional counseling (i.e., the presence of a separate licensure and certification processes focused on addiction counseling). While the addiction counseling field did need professionalization, perhaps the original high standards (e.g. upwards of 3,000 hours of clinical practice with supervision) now require recalibration that takes into account a new era where counselor training for those engaged in addiction work extends far beyond a high school diploma or GED.

Professionalization or Deterrent?

The authors’ perspective in this paper is that imbedded in the current licensure and credentialing process for addiction counseling is the message that LPCs cannot or should not do addiction work. The message comes from a confusing mixed array of information. Using the graduate trainee (the next generation of counseling professional) as an example, it becomes clear as to how future LPCs may shy away from addiction work. For instance, in the classroom graduate students read about how counseling includes working in the addiction area (as per the latest CACREP standards). Graduate students are trained in a graduate counseling curriculum that offers advanced addiction course electives and the possibility of doing practicums or internships at an addiction facility. Many of these graduate students may even attend school in a state where addiction work is covered in the professional counseling scope of practice. But, these students also see professional counselors with separate addiction licenses (e.g., LPC and LCADC) and employment announcements requesting/requiring an addiction license. Even the National Board of Certified Counselors (NBCC) Master Addiction Counselor Credential (MAC) focused on this one DSM-IV-TR disorder class (with no other NBCC credential so narrowly focused on one DSM-IV-TR disorder). Because the student does not see an NBCC credential for mood disorders or sees a licensure for anxiety disorders, the imbedded message is strengthened.

The mixed messages coupled with the burdensome task of meeting the mandates for two professional bodies (professional counseling and addiction) may drive some new counselors from the addiction field. For example, at the end of a panel discussion on this topic at the 2011 American Counseling Association Conference (Morgen et al., 2011), a new graduate of a professional counseling master’s program said she would like to start accruing practice hours in a substance use disorders clinic as she had completed some internship hours there and took a course on substance use disorders. However, the facility where she wanted to work required her to obtain an addiction license in addition to her professional counseling license. She subsequently indicated that she did not have the time, money, or the energy to do both and was thus looking outside the substance use disorders field for employment. This anecdote clearly demonstrates how newly graduated counseling professionals (especially those working in the provisional licensure period) may be inhibited from entering the addiction counseling field.

How many qualified, talented and motivated students are we turning away from the addiction counseling field due to these extra training requirements unique to working with the specific DSM-IV-TR Axis I Substance Use Disorder diagnosis at a time when there is an ever-growing need for services (e.g., addiction in returning veterans or the chronically unemployed)? Effective training of LPCs who work with addiction requires coordination between educational training institutions and actual practice that reflects reasonable experienced-based requirements for working in the area of addiction as well as respect for the graduate-level degree (e.g., master’s or doctorate) and training the counselor has already received. Such coordination varies from state to state and without a guarantee of such coordination the danger is that well-intentioned, well-trained counselors will enter the field technically qualified to counsel individuals, but philosophically lacking the integration of theory and practice necessary for treating addiction. This could mean, for example, that the counselor is more vulnerable to enabling the active addictive process and thereby not providing counseling in the best interest of the client.

In an effort to initiate the dialogue on how to perhaps recalibrate the system, it first seems warranted to review the professional and addiction counseling licensure laws and policies within two states. The authors intend to (over the next few years) review the state laws and policies for all 50 states. However, for the purposes of this initial paper, New Jersey and North Carolina will be discussed below.

Specific State Issues

New Jersey

New Jersey operates a professional counseling license (LPC) with a minimum education of a graduate counseling degree, a certified alcohol and drug abuse counselor credential (CADC) requiring a minimum education of bachelor’s degree, associate degree, high school diploma or GED, and a licensed clinical and alcohol and drug abuse counselor (LCADC) with a minimum education of a graduate counseling degree and qualification for the CADC. The LPC is governed by the Professional Counselor Examiners Committee (imbedded within the Marriage and Family Therapy Board), whereas the CADC/LCADC is governed by the Alcohol and Drug Counselor Committee.

According to the regulations for professional counseling, New Jersey defines counseling in part as “using currently accepted diagnostic classifications including, but not limited to the DSM-IV” (NJ Board of Marriage and Family Therapy Examiners, 2009, 13:34-10.2, p. 34-22). Substance use disorders fall within Axis I of the DSM-IV-TR, thus work with substance use disorders seems in line with the professional regulations of the LPC. Further evidence of this fact exists within the LCADC regulations (NJ Alcohol and Drug Counselor Committee, 13:34C-2.6, p. 34C-10) that states the following individuals are exempt from the LCADC licensure requirement:

A person doing work of an alcohol or drug counseling nature, or advertising those

services, when acting within the scope of the person’s profession or occupation and

doing work consistent with the person’s training, including physicians, clinical social

workers, professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, nurses

or any other profession or occupation licensed by the State, or students within accredited

programs of these professions, if the person does not hold oneself out to the public as

possessing a license or certification issued pursuant to the Act or this chapter.

As long as an LPC does not advertise oneself as an addiction or substance abuse counselor, they are completely free to practice counseling with individuals presenting with addiction.

However, new counselors and LPCs who wish to accrue hours toward addiction licensure/credentialing face obstacles within the hiring process for addiction-focused positions. For example, despite the clear language in the LPC and CADC/LCADC regulations, advertised positions in the addiction counseling field in New Jersey typically include language stating “actively pursuing CADC/LCADC” or “must hold a New Jersey CADC/LCADC.” These requirements (which again, contradict the language of the New Jersey LPC and LCADC regulations) are typically in place due to a mandate of the program funding source (e.g., state or federal). Private practice counselors (who do not operate any funded programs with the above-mentioned requirements) are free to practice addiction work if qualified. However, most (if not all) of the addiction counseling positions where a new professional counseling graduate can accrue hours are housed in some type of treatment facility that very likely must adhere to the LCADC mandate, thereby limiting access to positions for those seeking to accrue LPC hours within the addiction counseling field.

In New Jersey, the typical master’s student who wants to accrue hours for licensure as an LPC must produce approximately 4,500 supervised counseling hours. This process comes immediately after the challenging two to three years of graduate study and passing the National Counselor Exam (NCE). However, to obtain the LCADC these students must complete an additional and separate 3,000 supervised addiction counseling hours, 270 clock hours of education focused on counseling and addiction, and 300 hours of supervised practical training in core counseling areas such as screening, intake, assessment, etc. The primary and most time-consuming problem lies in the need to accrue the supervised addiction counseling hours. Since the supervised counseling hours cannot be combined (e.g., there is no language in either the LPC or LCADC regulations permitting or denying the “double-dipping” of an hour for inclusion in both the LPC and LCADC hours accrual for licensure; this alone is confusing and indicates a need for clarification), the trainee working towards licensure who wishes to work in an addiction facility must accrue thousands of extra hours or opt to only work towards the LCADC. No other DSM-IV-TR disorder class comes with this burdensome extra mandated training requirement.

Recent efforts to integrate the mental health and addiction licensure processes in New Jersey are in motion, but still in an early phase. Much of this work is coming from a project sponsored by the New Jersey Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services designed to train the next generation of dual-licensed and trained (mental health and addiction) practitioners. However, this need to streamline the process is only present because of the dual licenses already in place. Furthermore, the premise of the program (though an excellent contribution) still propels the notion that addiction falls outside the scope of LPC practice and there needs to be a process to merge the two together. Despite the benefits of this new initiative, the end result is still the same: two different licenses. Again, this is the only DSM-IV-TR disorder that receives this treatment.

North Carolina

North Carolina has a well-coordinated system for addiction counselors. All professionals who want to be licensed to work in the addiction counseling field need to go through the same board, the NC Substance Abuse Professional Practice Board (the Board), which is “recognized as the registering, certifying, and licensing authority for substance abuse professionals” (Practice Act, 2005, Senate Bill 705, North Carolina General Assembly, § 90 113.32). One board eliminates competition between boards and the related issues that arise. In fact, the Licensed Professional Counselors Act (LPC law) specifically exempts substance abuse counselors from the counseling law by declaring that nothing in the LPC law “shall prevent a person from performing substance abuse counseling or substance abuse prevention consulting” (NC Board of Licensed Professional Counselors, 2009, § 90-332.1.d). Having one board brings together individuals from various professions in a concerted effort to address the issues related to addiction counseling and to advocate for the field at a state level. This framework has the strength of cooperation between different professional groups and the absence of competition within a state.

This cooperation is enhanced by a tiered system (licensure and credentialing). Individuals may apply for licensure as a Licensed Clinical Addictions Specialist. With regard to entry at the licensure level, there are four main routes or criteria (Criteria A, Criteria B, Criteria C, and Criteria D). Although initially the system may be confusing to determine the criteria under which one fits, the advantage is that there is greater flexibility for the individual applying for licensure. This flexibility is the result of minimum requirement variation in the areas of education, training, experience, and supervision (Criteria A, B, & C), as well as professional discipline (e.g., psychology, social work, counseling—Criteria D). For specific guidelines and clarification of this summary, the reader is referred to: http://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/ByArticle/Chapter_90/Article_5C.html.

In terms of similarities for the individual applying for licensure, there are two aspects that remain the same under Criteria A, B, and C: the submission of three letters of reference (there is some variation allowed for the individuals who can write these letters) and a passing score on a master’s level written examination administered by the Board. The variations under these criteria are as follows. In the area of education, Criteria A and B require a minimum of a master’s degree with a clinical application in a human services field from a regionally accredited college or university. In addition, in terms of training, Criteria A requires 180 hours of substance abuse specific training from either a regionally accredited college or university, which may include unlimited independent study or from training events of which no more than fifty percent (50%) shall be in independent study. Criteria C combines the education and training requirement in the minimum requirement of a master’s degree in a human services field with both a clinical application and a substance abuse specialty from a regionally accredited college or university that includes 180 hours of substance abuse specific education and training. In the area of experience, Criteria A requires two years postgraduate supervised substance abuse counseling experience, while Criteria B requires the applicant to be certified as a substance abuse counselor. Finally, regarding supervision, Criteria A requires documentation of a minimum of 300 hours of supervised practical training and provision of a board-approved supervision contract between the applicant and an applicant supervisor, while Criteria C requires one year of postgraduate supervised substance abuse counseling experience. Criteria D simply requires that the applicant has a substance abuse certification from a professional discipline that has been granted deemed status by the Board (i.e., possession of a certification to practice addictions work under another discipline, such as social work, and that certification is recognized by the counseling board).

Note that the Board also offers numerous credentials through certification for non-master’s-level professionals. These include the Certified Substance Abuse Counselor (CSAC), Certified Substance Abuse Prevention Consultant (CSAPC), Certified Criminal Justice Addictions Professional (CCJP) and the Substance Abuse Residential Facility Director (CSARFD) credentials. In terms of the CSAC and the CSAPC, the applicant needs to be of good moral character, not be (or have been) engaged in any practice or conduct that would be grounds for disciplinary action, have a minimum of a high school diploma or a high school equivalency certificate, sign a form attesting to the intention to adhere fully to the Board’s ethical standards, and submit a complete criminal history record check.

Additionally, a CSAC who completes a clinical master’s degree program in a human services field can seek the LCAS via Criteria B as outlined above. This criterion recognizes the fact that the CSAC has already completed a 300-hour supervised clinical practicum and has substance abuse specific work experience. In addition to submitting proof of one’s master’s degree, all one has to do to obtain the LCAS via this criteria is to submit three letters of reference from LCAS’s and/or master’s level CSAC’s and pass the LCAS examination.

This tiered system allows the counselor to enter the field with or without a masters’ degree and allows the master’s=level counselor to have an accelerated process if they acquire clinical application experience enhancing the possibility they are both technically and philosophically prepared to work in the addiction counseling field. The requirement of the clinical application experience may be a barrier for some counselors, but the intent is to serve the best interests of the public.

Finally, there is collaboration between the Board and specific university degree programs regarding the type and quality of the courses, thus increasing the chance that counselors are effectively trained to work in the addiction counseling field. While there is not “board approval” on the content areas, programs are approved for addiction counseling. Students who graduate from these master’s degree programs may seek the LCAS license via Criteria C (outlined above). The Board maintains a current list of school programs approved for application under Criteria C on its website: http://www.ncsappb.org/certificationssteve/criteriaschools2.htm.

While North Carolina’s tiered system of licensure and credentialing allows for greater flexibility for the individual applying to work in the addiction counseling field, the system can be overwhelming and does contribute to the perception that addiction counseling is a separate profession with separate education, training, supervision and practice. Kaplan and Gladding (2011), King (2011), and Gladding, Kaplan, Linde, Mascari, and Tarvydas (2011) have advocated along with others about the importance of a unified counseling identity with common skills, training and practice (particularly among counseling specialties).

Recommendations

Overall, there appears to be a need for a recalibration of the experienced-based training required for LPCs at a national level that will enhance their entrance into the field of addiction counseling. Currently, states that do not allow for multiple entries into the field have a tiered system of entry, or an approval mandate of the type or quality of the addiction training program, that may inhibit LPCs from practicing in the addiction counseling field. In states where there are significant barriers, professional counselors (fully licensed or in-training) entering the addiction counseling profession with a graduate degree may be required to complete additional training requirements that were created during a time when the addiction counseling professional possibly possessed no more than a high school diploma or GED, and such credentialing requirements (e.g., thousands of supervised hours) were imposed as a mechanism to professionalize the field. Considering the graduate counseling degree (and associated supervised counseling hours) held by a LPC or counselor-in-training accruing licensure hours, these mandates currently seem excessive and possibly even redundant. Presently, the North Carolina system may be one of the few in the United States that provides the fewest barriers for LPCs entering the addiction counseling field.

In the following section, two remedies for the licensure/credentialing problems are presented. Although myriad issues complicate the process (e.g., counselors are called different titles in different states and different state requirements are present for licensure/credentialing as an addiction counselor), the following suggestions in some conceptualization may spur more tangible action. Any formal action should likely come from a national committee set up through the American Counseling Association (ACA) and in conjunction with the ACA addiction division, The International Association of Addictions and Offender Counselors (IAAOC), as well as CACREP, and national bodies such as the National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors (NAADAC) and the International Certification and Reciprocity Consortium (IC&RC). Committee representatives from these parties could examine the coordination of experience and training. Such a committee could develop guidelines for balancing these concerns for states to use in their individual recalibration of requirements.

Possible Solution #1: Nationally Recognized Tiered System of Addiction Counselor Credentialing

One of the difficulties in terms of the current state of addiction credentialing in the U.S. is the absence of uniform national curriculum training standards in the addiction field. Also, there are two main national credentialing groups: NAADAC and the IC&RC. Issues arise because affiliation with one of the two main credentialing groups and credentialing variations between these organizations can result in issues in terms of competition and the nature of the boards and exams required for credentialing. Miller, Scarborough, Clark, Leonard, and Keziah (2010) recommend the following with regard to addiction counseling: (a) portability of credentials, (b) competition reduction between credentialing groups and state boards, (c) national standards for addiction education and training, and (d) a standardized national licensure/credentialing process. Unfortunately, these recommendations have not yet been fully implemented.

One possible solution is to develop a tiered system of addiction counseling credentials at a national level that takes into account professional experience as well as educational training. There needs to be a balance between the idea that anyone with a general counseling degree can do addiction counseling and the idea that only a few select counselors can do the work. Furthermore, this balance should be firmly based upon the ACA Ethical Code that indicates that counselors only practice within their area(s) of competence (2005).

For example, graduates of professional counseling programs (e.g., those working towards LPC status) who have taken a nationally-approved addiction counseling curriculum and have completed practicum/internship experiences could be designated as having addiction credentials in addition to the LPC (i.e., a nationally approved addiction concentration). Therefore, graduate counseling coursework that includes addiction counseling education and practical experiences would enable new graduates to move seamlessly into the addiction counseling profession without the need for additional supervision hours or educational components (i.e., beyond the required supervised counseling hours and educational components required for the LPC). The system would eliminate the need for a professional counselor to acquire an additional and separate addiction license/certification. In addition, the national standards could promote portability of credentials. This compromise works to maintain the licensed/certified addiction counseling credentials in each state while also providing the LPC with the documented expertise required for many addiction facility positions. This tiered system also could facilitate enhanced training during the process of accruing hours for licensure by better focusing the training hours upon the interface between addiction and other mental health issues as opposed to the current parallel and disparate relationship between addiction and other mental health issues.

Possible Solution #2: Nationally Recognized Addiction Counseling Concentration Curriculum

There are issues regarding standardization of training that need to be addressed within the context of academia. In essence, what are the theoretical and practical skills required of an addiction counselor nationwide? There are numerous initial places to look into the process of establishing a nationally recognized addiction counseling concentration, such as the 2009 CACREP standards for addiction counseling and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment’s (2006) Addiction Counseling Competencies: The Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes of Professional Practice. By using these (and other) standards, all counseling programs (regardless of CACREP accreditation) can follow a standard recommended education experience for students who desire the addiction credential discussed in the first possible solution. Curricular issues would likely include standalone addiction courses, infusion of addiction content into other courses, faculty expertise in the addiction area and practicum and internship hours focused on addiction counseling practice.

In addition, the NCE and National Clinical Mental Health Counselor Examination (NCMHCE) would require some recalibration to take into account the curricular changes to a professional counseling education that includes the addiction counseling concentration. One caution is that any discussion of these and other training issues may produce opposing forces within academia, the counseling profession, the addiction counseling profession, state licensing/credentialing boards (both professional counseling and addiction) and individual counselor education professors and college/university departments. Again, that is why a national committee comprised of all involved parties is necessary to navigate this challenging process.

Concluding Comments

Two students graduate with a master’s degree in counseling. Both took elective courses in their area of interest; one in mood disorders, the other in addiction, and both did an internship in a counseling setting focused on their interest area. Upon graduation, the student with an interest in mood disorders can easily be brought onto the clinical roster of a mood disorders clinic and immediately start accruing hours towards licensure. Their provisional license is all that is required during the training period. Unfortunately, the graduate with an interest in addiction may face competing licensure and/or credentialing requirements between professional and addiction counseling, mandated extra training coupled with thousands of extra supervised hours, and/or the possibility of a denial of employment without the appropriate addiction credential.

The purpose of this article is to start the dialogue on how to effectively incorporate addiction counseling into the scope of practice and accepted role of the professional counselor. We firmly believe that effective counseling focused on addiction issues requires specific and rigorous counselor training. However, we also believe the current national practice of training and credentialing for addiction counseling must change. State-by-state, burdensome (and in some instances outdated) rules and regulations are keeping countless qualified, capable, and motivated counselors from entering the addiction field. The time has come to recalibrate the rest of the counseling profession to better fit an inclusive and unifying professional counseling identity that includes addiction counseling.

References

American Counseling Association. (2005). Code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling Related Educational Programs (2009). CACREP standards. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Calley, N., & Hawley, L. (2008). The professional identity of counselor educators. The Clinical Supervisor, 27(1), 3–16. doi:10.1080/07325220802221454

Cashwell, C., Kleist, D., & Schofield, T. (2009, August). A call for professional unity. Counseling Today, 52(2), 60–61.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2006). Addiction counseling competencies: The knowledge, skills, and attitudes of professional practice. Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) Series 21. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 06-4171. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Gale, A., & Austin, B. (2003). Professionalism’s challenges to professional counselors’ collective identity. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81(1), 3–10.

Gladding, S. T., Kaplan, D., Linde, L., Mascari, J. B., & Tarvydas, V. (2011, March). 20/20: A vision for the future of counseling – The new consensus definition of counseling. Educational session presented as the ACA 2011 Conference, New Orleans, LA.

Henriksen, R. C., Nelson, J., & Watts, R. E. (2010). Specialty training in counselor education programs: An exploratory study. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory, and Research, 38(1), 39–51.

Kaplan, D. M., & Gladding, S. T. (2011). A vision for the future of counseling: The 20/20 principles for unifying and strengthening the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 367–372.

King, J. H. (2011). The role of ethics in defining a counseling professional identity. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation proposal, Capella University, United States: Minnesota.

Mellin, E. A., Hunt, B., & Nichols, L. M. (2011). Counselor professional identity: Findings and implications for counseling and interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(2), 140–147.

Miller, G. (2010). Learning the language of addiction counseling (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Miller, G., Scarborough, J., Clark, C., Leonard, J. C., & Keziah, T. B. (2010). The need for national credentialing standards for addiction counselors. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 30, 50–57.

Morgen, K., Miller, G., Culbreth, J., & Juhnke, G. (2011, March). Analysis of professional and addiction counseling licensure requirements, scope of practice, and training: National findings. Educational session presented at the American Counseling Association Conference & Exposition, New Orleans, LA.

Myers, J. (1995). Specialties in counseling: Rich heritage or force for fragmentation? Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(2), 115–116.

Myers, J., Sweeney, T., & White, V. (2002). Advocacy for counseling and counselors: A professional imperative. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80(4), 394.

Nassar-McMillan, S. C., & Niles, S. G. (2011). Developing your identity as a professional counselor. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

New Jersey Alcohol and Drug Counselor Committee. NJSA 45:2D-1 through 45:2D-18, 13:34C-1.1 through 13:34C-6.4.

New Jersey Board of Marriage and Family Therapy Examiners, NJSA 45:8B-13 and 34, Professional Counselor Regulations 13:34-9.1 through 13:34–19.6.

North Carolina Board of Licensed Professional Counselors, Licensed Professional Counselors Act § 90-332.1 (2009).

North Carolina Substance Abuse Professional Practice Board, North Carolina Substance Abuse Professional Practice Act § 90 113.32 (2005).

Remley Jr., T. (1995). A proposed alternative to the licensing of specialties in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(2), 126–129.

Remley, T., & Herlihy, B. (2009). Ethical, legal, and professional issues in counseling (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Sweeney, T. (1995). Accreditation, credentialing, professionalization: The role of specialties. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(2), 117–125.

Tabor, J., Camisa, K., Yu, F., & Doncheski, M. (2011, March). Addressing nationwide Inconsistencies in the scope of practice for licensed professional counselors regarding substance abuse counseling. Poster presented at the American Counseling Association Conference and Exposition, New Orleans, LA.

Keith Morgen, NCC, teaches at Centenary College, Geri Miller teaches at Appalachian State University and LoriAnn S. Stretch teaches at Walden University. The authors thank Anna Misenheimer, Executive Director of the North Carolina Substance Abuse Professional Practice Board, for serving as a reader of the early drafts of this paper. Her feedback was critical in our sharpening the preliminary focus of the paper. Correspondence can be addressed to Keith Morgen, Centenary College, 400 Jefferson Street, Box 403, Hackettstown, New Jersey, 07840, morgenk@centenarycollege.edu.

Sep 3, 2014 | Article, Volume 2 - Issue 1

W. P. Anderson Jr., Sandra I. Lopez-Baez

Little is known about levels of personal growth attributed by students to typical college life experiences. This paper documents two studies of student self-reported and posttraumatic growth and compares growth levels across populations. Both studies measure student attributions of cause to academic and non-academic experiences, respectively. It is suggested that future research on the outcome of college life experiences can use a similar approach with a variety of variables.

Keywords: college life, personal growth, posttraumatic growth, life experiences, attributions of cause, outcome of college

The results of a rapidly growing number of studies document high levels of adversarial growth attributed by survivors in retrospect to coping with negative life experiences (Linley & Joseph, 2004) including war, bereavement, or loss of a child. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) by Tedeschi & Calhoun (1996) has been the most popular measure of adversarial growth to date (Joseph, Linley, & Harris, 2005; Linley & Joseph, 2004; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). In this context, adversarial refers to the negative nature of an experience of interest to researchers. Growth refers to personal growth defined as the positive psychological changes described by assessment-instrument items, changes such as the building of interpersonal relationships, a greater appreciation of the value of life, and a realization of new possibilities in life (examples after Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Thus, adversarial growth is personal growth attributed by participants to a naturalistic negative event of particular interest to researchers. We stumbled on the PTGI and the relationship between adversarial and personal growth while searching for an instrument for measuring personal growth attributed in retrospect to the sum of naturalistic experiences (both positive and negative) occurring during a time period of interest to researchers.

The growth of immediate interest to us is not adversarial, but rather the total personal growth of college students because our long-term goal is to determine how educators can best facilitate growth, whether adversarial or otherwise. Developmental theorists (Chickering, 1969; Chickering & Reiser, 1973; Pascarella & Terenzine, 1991; Perry, 1970) have suggested that students grow in response to the combination of typical experiences of college life. Although researchers have used a variety of instruments to measure both academic and personal growth (for recent examples see Hassan, 2008; Higgins, Lauzon, Yew, Brasweth, & Morley, 2009), little is known about how college-student growth compares to adversarial growth because comparisons require measures obtained with the same instrument. Therefore, we want to measure college-student growth with an instrument that has been used to measure adversarial growth. Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) implied that the PTGI might be suitable for our purposes by characterizing its items as capturing the core of personal growth (without distinguishing between adversarial and personal growth). We decided to use the PTGI after noting that the developers themselves conducted the first study of non-adversarial growth based on the PTGI by using it to measure levels of personal growth described by college students in a small (n = 32) non-trauma comparison group (see study 3 in Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996).

We conducted the second and third studies of interest (N = 347, N = 117) by using the PTGI to measure levels of college student personal growth, whether adversarial or otherwise attributed to a single semester of college life (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008, 2011). All three previous studies documented mean levels of student personal growth near the midpoint of the range reported for posttraumatic studies (range 46.00–83.47 for 14 studies summarized by Linley & Joseph, 2004). In our second study, we elicited brief explanations from students to learn how they accounted for their growth (see Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011). Explanations were in the form of percentage attributions of total personal growth to student-identified naturalistic experiences and to a researcher-identified 3-hour course designed to facilitate growth (student explanations like: college internship accounted for 30% of my total personal growth, finding a job for 40%, 3-hour course of interest to researchers for 15%, miscellaneous other experiences for the remaining 15%). We refer to these explanations as attributions of cause. Student attributions of cause to academic experiences supported the appealing idea (to counselors and educators) that personal growth as defined and measured by the PTGI can be intentionally facilitated by activities designed to do so.

The two studies described in the current paper are the fourth and fifth based on the PTGI to measure college-student personal growth that was not strictly adversarial. Both samples are generally similar to those of our previous studies (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008, 2011). The current studies extend the results of our previous ones by (1) measuring the growth attributed by sample members to substantially longer periods of college life and (2) eliciting separate attributions of cause for academic and non-academic experiences, respectively. The primary purpose of Study 1 was to examine the internal validity of student data collected with the PTGI by comparing the descriptive statistics among the results of Study 1 with those of the three previous studies described above (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008, 2011; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). The primary purpose of Study 2 was to measure graduating college-senior attributions of annual personal growth, in retrospect to their freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior years, respectively. Study 2 was descriptive.

Study 1: Cumulative Growth

Research questions 1 and 2 are designed to collect descriptive data. Research question 3 is designed to collect information about the internal validity of our data by testing hypotheses on the basis of comparisons of the results of Study 1 with the results of previous studies (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008, 2011).

Research question 1. What levels of cumulative personal growth do participants describe for their college undergraduate years (descriptive statistics for PTGI scores)?

Research question 2. What cumulative percentage attributions of cause do participants describe for academic experiences (college credit) and non-academic (all other) experiences, respectively, during their college undergraduate years (descriptive statistics for attributions of cause)?

Research question 3. To what extent do the results of comparable studies reflect internal validity (comparisons of statistical results across studies)?

Method

Participants

We recruited participants from among the 147 students in a 3-hour elective course, Problems of Personal Adjustment, taught by the first author at a southeastern university. The course covered topics of psychological adjustment and included activities to facilitate student personal growth. Data was collected at the end of the fall semester of 2007. Most students were third- and fourth-year undergraduates in the College of Arts and Sciences or the School of Commerce. A total of 137 students elected to participate (response rate 93.20%). After 15 questionnaires with missing data were eliminated, sample size was 122 (67 men, 55 women). Most participants were Caucasian (4 African Americans, 4 Hispanics, Asians, and Asian Americans) with a mean age of 21.05 (.79) years and a mean college career of 6.54 (1.34) completed semesters. Students were given extra credit for electing to participate.

Measures

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Each of the 21 PTGI items (Cronbach alpha = .90, test-retest r = .71) describes a single positive psychological change (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Examples (with corresponding subscale and number of subscale items) include: “A sense of closeness with others” (Relating to Others, 7 items), “I developed new interests” (New Possibilities, 5 items), “A feeling of self-reliance” (Personal Strength, 4 items), “A better understanding of spiritual matters” (Spiritual Change, 2 items), and “My priorities about what is important in life” (Appreciation of Life, 3 items). Participants of trauma studies are instructed to describe the degree of each change resulting from their trauma. Responses are positions on a 6-point Likert-type scale anchored by 0 (no change) and 5 (great change). Total score range is 0 to 105 (per-item basis 0 to 5.00). Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) reported evidence for concurrent and discriminant validity (their second study 1996) and construct validity (their third study). We have previously reported mean levels of college-student growth of 59.07 (SD = 15.77, N = 347; Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008) and 60.42 (SD = 16.61, N = 117; Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011).

Blank table. We use a blank, 2-column table to elicit attributions of cause (see Appendix A). In column 1, participants list life experiences thought to have contributed most to their growth during their college years. Participants list estimates of corresponding percentage contributions to total growth in column 2. For purposes of this study, we tailored the table to provide subtotals of attributions of cause to academic experiences (lines 1–5) and non-academic experiences (lines 6–10). We pre-labeled Lines 4, 5, and 10. Line 4 refers to the course taught by the principal author from which participants were recruited.

Procedure

Like subjects in our two previous studies, participants were instructed to complete a preliminary exercise to stimulate thinking about personal growth by answering questions that distinguished between level and salience of growth. We do not report the results because the research questions of the current study do not involve salience.

After completing the preliminary exercise, participants were given the following instructions for completing the PTGI (after study 3, Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996):

Consider the degree to which each change listed below [21 items] has occurred in your life during your years as an undergraduate, whether or not the change was directly related to university class work. For each change, select the best response from the following scale [6 Likert-type options of Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996] and write the number in the space provided.

Participants provided attributions of cause by completing the form in Appendix A. Participants were instructed to complete lines 1–10 of column 1 (brief descriptions of experiences thought to have contributed most to total growth) and column 2 (corresponding percentage contributions). Participants also provided 1-line qualitative explanations of how each experience on lines 1–10 of column 1 contributed to their growth (entries not analyzed because not required by research questions).

Results

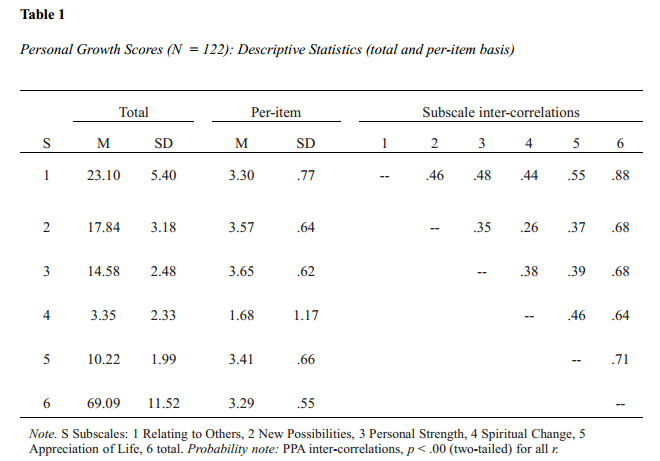

Cronbach alphas for each subscale calculated from the data of Study 1 are: .87 (all), .82 (Relating to Others), .65 (New Possibilities), .56 (Personal Strength), .82 (Spiritual Change), and .54 (Appreciation of Life). The mean female PTGI score of 71.71 (11.72) is greater than the mean male score of 66.94 (10.98), t (120) = 2.32, p = .022 < α = .05 (2-tail), d = .42. Male and female scores were combined because no significant gender differences were found by t-tests of corresponding subscale means (Bonferroni-corrected α = .01).

Research Question 1

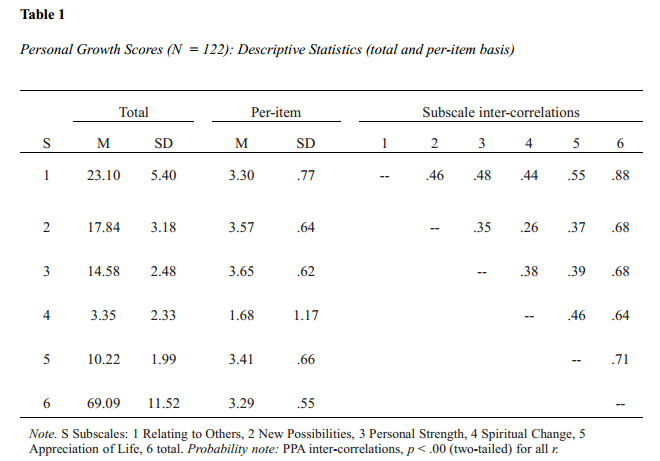

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for participant PTGI scores on a total and per-item basis. Magnitudes of Cronbach alphas reported above can be seen to reflect the variations in magnitude among the standard deviations reported for per-item subscale scores in Table 1 (larger Cronbach alphas are associated with larger standard deviations). This observation suggests that restricted ranges among our data for Personal Strength and Appreciation of Life account for the low values of alpha for each subscale.

The mean total of 69.09 (SD = 11.52) is greater than the midpoint of 52.50 for the maximum range of 0–105 and greater than the midpoint of 64.74 for the range of 46.00–83.47 reported for trauma studies (Linley & Joseph, 2004). The per-item mean of 3.29 (SD = .55) exceeds 3 or “moderate growth” on the 0 to 5 response scale (scale midpoint = 2.50). The per-item means for four of the five subscales are between 3.30 (SD = .77) and 3.65 (SD = .62), inclusive. The per-item mean for Spiritual Change is lower, 1.68 (SD = 1.17).

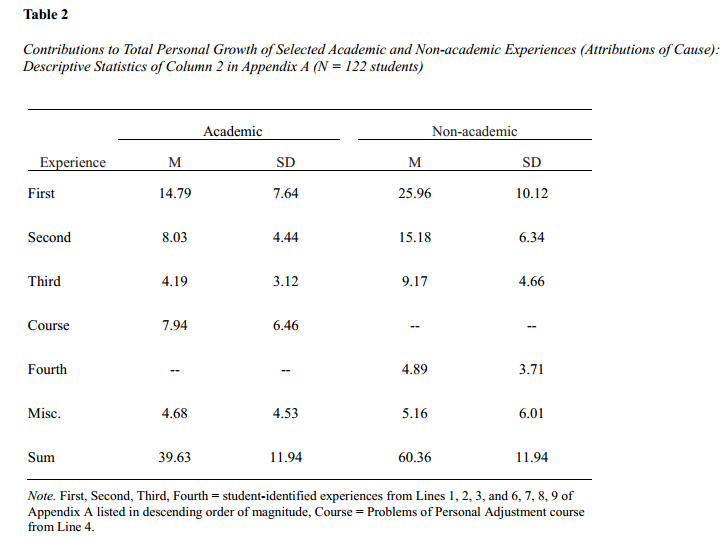

Research Question 2

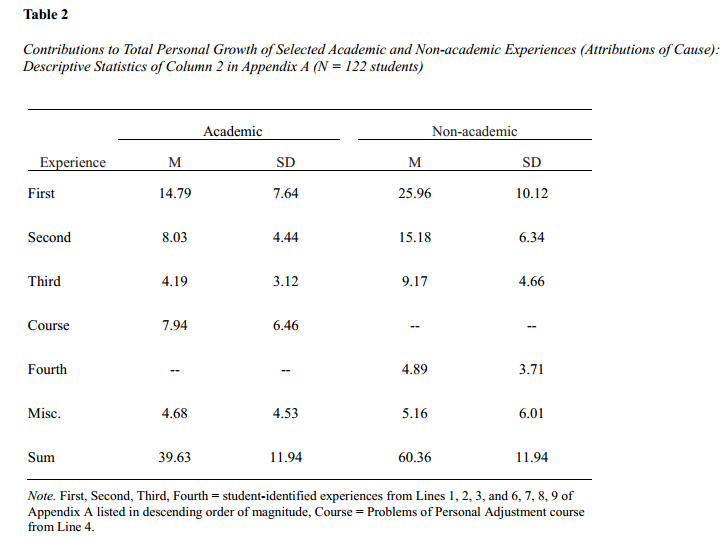

Table 2 contains descriptive statistics for participant percentage attributions of cause to academic and non-academic experiences, respectively (from column 2 of Appendix A). Both subtotals are large although the non-academic subtotal is larger by a ratio of approximately 3:2. The three academic experiences thought by each participant to have contributed most to his or her growth account for 30.76% (14.79 + 8.03 + 7.94%) of the mean subtotal of 39.63% (SD = 11.94) of total personal growth. Illustrative examples include internships, terms abroad, and three-credit semester courses. Participants attribute the third largest contribution (7.94%) to a course designed to facilitate growth. Three non-academic experiences account for 50.31% (25.96 + 15.18 + 9.17%) of the mean subtotal 60.36% (SD = 11.94). Examples include illnesses, extracurricular activities, deaths of family members, and positive and negative changes in significant relationships.

Research Question 3

Numerical PTGI scores and percentage attributions of cause are subjective assessments by participants, as are most self-reports. Our research purposes require data with a degree of internal validity (veridicality or truthfulness; that is, correspondence between self-reports and actual subjective impressions). Internal validity can be assessed by comparing results of analyses across samples of multiple studies. For purposes of the following comparisons, we will use words to number our previous studies and a numeral to designate Study 1 of the current paper. Thus, our sample one (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008) was a group of 347 students who described total growth in 2005 and 2006 for their preceding semester, M = 59.07 (SD = 15.77). Our sample two (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011) was a group of 117 students who described total growth and attributions of cause in May of 2007 for their preceding semester, M= 60.42 (SD = 16.61). Our sample 1 is that of the current study. Samples are characterized by similar demographic characteristics.

Comparison one. Members of samples one and two described total growth for a single semester. Therefore, we expected samples one and two to have similar mean PTGI scores (null 1: unequal mean PTGI scores). A visual inspection finds similar means. Null 1 is rejected on the basis of that visual inspection, Cohen’s d of .08 (minimal effect size), and 95% C. I. of – 4.71 to 2.01 that includes 0.00 (SE difference = 1.71). As expected, mean total scores of samples one and two are similar.

Comparison two. Members of sample 1 described total growth over more semesters than did members of samples one or two. Therefore, we expected our sample 1 mean PTGI score to be higher than the mean of either sample one or sample two (nulls 2 and 3: sample 1 mean less than or equal to means of samples one and two, respectively). Nulls 2 and 3 are rejected on the basis of a 1-way ANOVA F (2, 593) = 20.02, p = .000, η2 = .064 with an independent variable of 3 groups and dependent variable of student PTGI scores; and Bonferroni post-hoc t-tests of student PTGI scores: sample one and sample 1, t (467) = 6.44, p = 0.000 < α = .0167 (2-tail), d = .73; sample two and sample 1, t (237) = 4.70, p = 0.000 < α = .0167 (2-tail), d = .61; sample one and sample two, t (462) = .79, p = .430 > α = .0167 (2-tail), d = .08. As expected, the sample 1 mean of 69.09 is greater than the means of both sample one and sample two.

Comparison three. Visual inspection of the subscale per-item mean scores of sample one (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008) and sample two (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011) found that four of the per-item means in each sample are approximately equal and that all four are greater than the corresponding mean Spiritual Change score by 1.50 to 2.00 scale divisions. Therefore, we expected the subscale scores of our sample 1 to exhibit the same pattern. Visual inspection (Table 1) finds that they do. Thus, as expected, the five subscale per-item mean scores of each of our three samples are characterized by four comparatively high and approximately equal subscale mean scores and a comparatively low mean Spiritual Change score.

Comparison four. Members of all three samples completed the same 3-credit course (during different semesters) designed to facilitate personal growth. Members of sample two and sample 1 were asked for attributions of cause for the course (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011). The resulting attributions of cause to a course designed to facilitate growth are themselves evidence of internal validity. We expected members of sample two to attribute a larger percentage of total growth for one semester to the class than members of sample 1 attributed for the longer period of several semesters (directional null 4: sample two mean attributions of cause to course less than or equal to corresponding mean of sample 1). Null 4 is rejected on the basis of an independent t (237) = 12.18, p = .000 < α = .05 (1-tail), d = 1.56. As expected, the sample two mean attribution of cause to the course of 25.28 (14.28)% is greater than the corresponding sample 1 mean attribution of 7.94 (6.46)%.

Comparison five. Concurrent validity is the extent to which different measures of the same construct agree. We formulated Comparison five only after we saw an opportunity to investigate concurrent validity among the data of sample 1 by measuring the correspondence between high and low Spiritual Change scores in sample 1 and the presence or absence of corresponding written attributions of cause, respectively (null 5: no agreement). We defined high participant Spiritual Change scores as per-item mean scores of at least 3.50 scale divisions (at least 1 division above scale midpoint 2.50). Sample 1 contains 11 high scorers (2 students scored 5.00, 1 scored 4.50, 3 scored 4.00, 5 scored 3.50). We defined low Spiritual Change scores as per-item mean scores no larger than 1.50 scale divisions. Sample 1 contains 64 low scorers (14 students scored .00, 17 scored .50, 20 scored 1.00, and 13 scored 1.50). We added 19 questionnaires selected at random from those of the 64 low scorers to provide a sample of 30 questionnaires for analysis.

We examined each sample member’s written attributions of cause for evidence of spiritual growth. We defined evidence of spiritual growth narrowly by the wording of the Spiritual Change items (PTGI items 5 and 18). Thus, we defined evidence of spiritual growth as student descriptions of one or more attributions of cause with at least one explicit reference to religion or spirituality including references to worship, God (or other deity or deities), prayer, or religious writings; but not references to ethics, morality, or meaning of life in the absence of the required explicit references. (Example attributions interpreted as evidence include: my faith deepened, came to accept God’s will, learned more about Bible; but not: grew in commitment to boyfriend, learned importance of moral behavior, decided on career choice, or obtained new understanding of life). We easily reached consensus on all identifications because of the simple and specific definition of evidence adopted beforehand. Attributions by 6 of the 11 high scorers and 2 of the 19 low scores contained at least one reference to spiritual growth. Half of the 8 attributions with references to spiritual growth referred to religious studies classes.

High and low Spiritual Change scores corresponded to the presence or absence, respectively, of attributions of cause for 24 of 30 sample 1 members, percentage agreement = 80.00%. Spearman r is a measure of agreement between two series of nominal data that does not take into account the probability of chance matches. The probability of chance matches is high among data of interest because the sample is characterized by many low scores and many non-positive attributions of cause. Cohen’s κ (1960) is a measure of agreement between two series of nominal data that accounts for the probabilities of chance matches. Cohen’s κ was originally developed to assess inter-rater agreement and is widely used for that purpose. We used it instead to measure agreement after accounting for chance between two series of nominal data rated jointly by consensus. Kappa values have a range 0 to 1 and are interpreted like positive correlation coefficients. Null 5 is rejected on the basis of a Spearman r = .51, p = .005 (1-tail) and κ = .44, approximate SE = .19, approximate p = .013.

Discussion

Measures

This study is based on a mixed-methods design with two measures for data collection. The first is the PTGI, a self-report instrument developed from standard psychometric techniques. Posttraumatic researchers use the PTGI to measure personal growth attributed to a trauma of interest to researchers. We use the PTGI as described by the instrument developers (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996) to measure total personal growth attributed to the sum of experiences during a time period of interest. Our second measure is an open table for obtaining participant attributions of cause for total personal growth. Participants complete the table with written descriptions of personal experiences and estimates of corresponding percentage contributions. The table design is adapted from one introduced in a previous study (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011).

Validity

The purposes of the current study require a degree of veridicality (truthfulness), a form of internal validity. Researchers have reported little evidence of any kind for the validity of subscale scores beyond the results of exploratory factor analysis (see review in Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008). This is perhaps the reason why researchers have drawn few conclusions about growth from subscale scores in their results. Our comparisons one to three in the current study demonstrate the existence of predicted relationships among total PTGI scores of three samples and therefore a degree of internal validity for the collection of individual items and total PTGI scores. Comparison four demonstrates the existence of a predicted relationship between the attributions of cause from two studies and therefore a degree of internal validity for data obtained with the table-based approach. Comparison five demonstrates a degree of concurrent validity for both the subscale of Spiritual Change and the table-based approach.

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory as a Measure of Personal Growth

The PTGI was developed as a measure of posttraumatic growth. Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) described their instrument as reflecting the core of personal growth. The results of the current study offer strong support for Tedeschi and Calhoun’s description because the results report high levels of personal growth for students without regard to prior experiences of trauma. We believe that if the PTGI can be used to measure the personal growth of samples of populations as dissimilar as college students and trauma survivors, then the PTGI can probably be used as a measure of personal growth under other circumstances in future studies.

College-Student Growth and Posttraumatic Growth

Magnitude. Theorists have identified the college-student undergraduate years as a time of personal growth in response to both academic and non-academic experiences (Chickering, 1969; Chickering & Reisser, 1993; Perry, 1970) in terms that suggest the definition of personal growth embodied in the items of the PTGI. Researchers have generally confirmed theorist predictions of student growth (c.f., Hassan, 2008; Higgins et al., 2009), but not with measures that allow for comparison of personal growth in response to trauma. Therefore, we are not surprised that the results of the current study reflect student growth. We are surprised, however, by the magnitude of that growth, m = 69.09 (SD = 11.52) because it is so near the maximum of the range reported in previous studies of posttraumatic growth (Linley & Joseph, 2004). We believe that this comparison helps readers appreciate the magnitude of growth described by each population.

Factor structure and subscales. The developers of the PTGI reported a 5-factor structure for the items of their instrument on the basis of an exploratory factor analysis (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996) and developed five corresponding subscales of unequal length. Subsequent posttraumatic studies have reported 2- and 3-factor structures (see review in Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008). Taken together, we interpret these EFA results as evidence that the factor structure of posttraumatic growth is not highly differentiated or stable across different samples. The results of several EFA described in our first study (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008) demonstrated that the factor structure of a sample of student scores also lacked differentiation and stability, and therefore resembled that of posttraumatic growth.

Posttraumatic researchers have typically reported descriptive statistics for the total PTGI score and for the original five subscales. We report our results this way in Table 1, but also include recalculations on a per-item average basis (total score and subscale scores divided by number of corresponding items). The per-item format allows for comparisons of scores for subscales of unequal length. The reader can verify by inspection of Table 1 that all of our subscale scores round to 3.50 (to nearest .5 scale units) except the score for Spiritual Change, which rounds to 1.50. We have observed a similar pattern among the results of our previous studies (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008, 2011).

During preparation of this manuscript, we conducted an informal visual comparison (not based on comparative statistics) of intra-sample per-item subscale scores listed in the results of posttraumatic studies cited by Linley and Joseph (2004) and observed that most subscale scores in each sample were of almost equal magnitude. Most of the few exceptions were low subscale scores (greater than 1.00 per-item average scale value) for Spiritual Change. We do not interpret our observation of this pattern as empirical evidence of anything; however, the observation makes us wonder about the empirical relationship between Spiritual Change and the other four subscales and highlights the importance of assessing the internal validity of Spiritual Change to lay the groundwork for any future studies of the internal structure of growth.

Spiritual Change and spiritual growth. Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) described the PTGI subscales as measures of five domains of personal growth. The results of our comparison three (see results section) reflect a pattern among mean subscale scores in which the per-item mean score for the Spiritual Change subscale is relatively low. This pattern is empirical evidence that growth does not occur uniformly across all domains at the same time, at least for spiritual growth as measured by Spiritual Change. The occurrence of the similar pattern we observed in the samples of many studies invites the following attempt to explain the pattern. An explanation might be especially important to educators and administrators of religious colleges and universities who actively seek to promote spiritual growth of students.

Developmental factors are probably at least partly responsible for the larger Spiritual Change scores in posttraumatic studies. Trauma study participants have generally been older than participants in samples of college students. Perhaps older people like those in many of the trauma-study samples are more likely than college undergraduates to describe spiritual growth. Perhaps spiritual growth is more characteristic of growth in response to trauma than of growth in response to college life. However, these two possibilities do not completely account for the pattern of interest (similar per-item subscale scores for four subscales and lower subscale score for Spiritual Change) because the pattern is not as pronounced among the five per-item subscale means reported by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) for their non-trauma comparison group of college undergraduates. The results of our comparison five (see results section) suggest another developmental factor. Comparison five is based on the narrow definition of spiritual growth embodied in the 2-item Spiritual Change scale. Participant interpretations of item content necessarily influence patterns among subscale scores. In particular, differences in religious background could contribute to different interpretations of Spiritual Change items. We recruited our sample members 12 years after Tedeschi and Calhoun recruited theirs, and we recruited ours from a different university in a different part of the United States. Perhaps our sample members have different religious backgrounds than the members of Tedeschi and Calhoun’s sample.

Intentional facilitation of growth. Personal growth can occur in response to very different kinds of experiences, from coping with horrible trauma to caring deeply for friends and significant others. Most of these experiences, certainly most of the traumatic ones, seem to arise spontaneously. This conclusion is important to philosophers and developmental theorists because it suggests that personal growth is central to the human condition. Developmental theorists have suggested that personal growth also can occur in response to planned academic activities. This prediction is important to educators and others concerned with how to facilitate growth.

Students in the current study sample attributed 40% of their personal growth to academic activities (see Table 1). We interpret these results as strong support for the prediction of personal growth in response to academic activities. Students in the current study and in the sample of our second study (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011) also attributed substantial growth to a single 3-hour course designed to facilitate personal growth. We interpret these results as support for the prediction that substantial levels of personal growth can be facilitated by specific academic activities designed to do so.

Current study results include attributions of cause for a single academic course designed in part to facilitate growth. The course is generally similar to that described by Hassan (2008) in a study of growth attributed to a health education course. The percentage attributions of cause to the course described in the current study (Table 2) are consistent with percentages reported in our previous study (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2011). The results of that preceding study and the study of Hassan (2008) strongly suggest that personal growth can be intentionally facilitated if not taught explicitly. The results of the current study suggest that substantial growth is attributed by students to coursework in general.

Current study results include subtotals of attributions of cause for academic and non-academic experiences, respectively. Sample members report attributions of almost 40% of total personal growth to academic coursework and provide further evidence that personal growth can be intentionally facilitated.

Study 2: Annual Growth

Taken as a whole, the results of Study 1 and three previous studies (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996; Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008, 2011) suggest that college students like those in the samples attribute substantial personal growth to both academic and non-academic experiences of their college years. These conclusions lead us to wonder just how much growth graduating seniors attribute to each college year. We believe the answer is of interest to college educators and administrators charged with fostering student growth. Answering this question requires a descriptive study of a representative sample drawn from a population of interest. Study 2 uses a simple descriptive design to answer the question for the population of students similar to those in the sample of Study 1.

Research Question

What levels of personal growth do members of a sample of college seniors attribute to each year of their 4-year college careers and what percentages do they attribute to academic and non-academic experiences, respectively?

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from graduating college seniors enrolled during the spring semesters of 2009 and 2010 in the course described in Study 1. Students earned extra course credit for participating. A total of 117 participants were recruited (70 of the 84 graduating seniors among the 142 students enrolled in the spring of 2009 and 47 of the 67 graduating seniors among the 144 students enrolled in the spring of 2010). A total of 108 participants (59 women and 49 men) remained after eliminating 9 questionnaires with missing data. Most participants were Caucasian (5 African American, 9 Hispanics, Asians, Asian Americans and other). Mean age was 21.64 (SD = .48) years. Academic concentrations (and number of students) were: college of arts and sciences (77), commerce school (18), college of engineering (12) and school of architecture (1). Participants completed the survey at the end of the last class meeting, approximately three weeks before graduation.

Measures

We used the PTGI to measure total personal growth. We used the table in Appendix B to elicit attributions of cause. Participants completed the table with annual estimates (in percent) of their personal growth, growth from academic experiences, and growth from non-academic experiences. We also asked participants to identify on a separate page (not shown in Appendix B) the experiences that they thought contributed most to their growth each year and to identify these experiences as either academic or non-academic.

Procedure

The first two pages of the Study 1 and Study 2 questionnaires (warm-up exercise and PTGI) were identical. Study 2 participants followed the instructions in Appendix B to provide attributions of cause.

Results

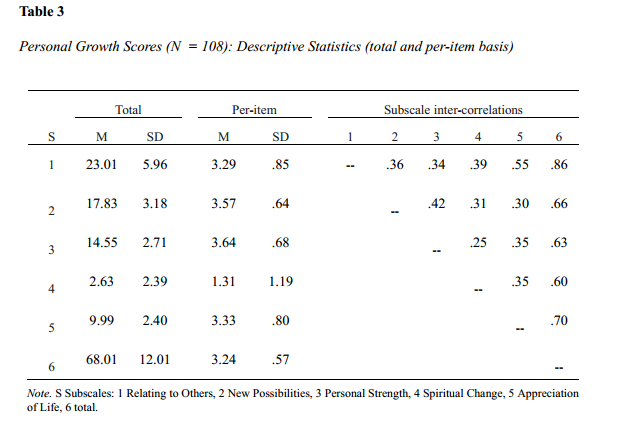

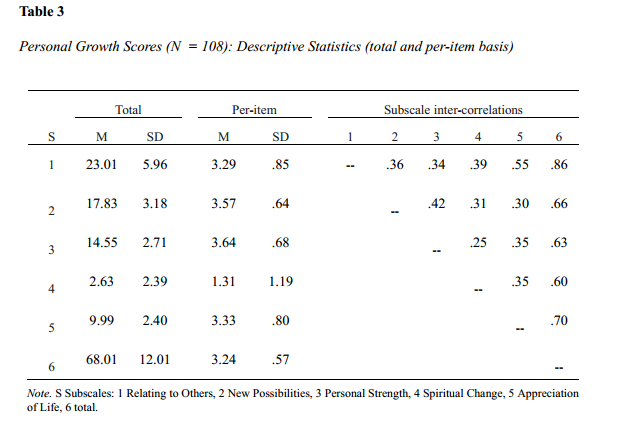

Subscale Cronbach alphas for our data are .85 (Relating to Others), .57 (New Possibilities), .59 (Personal Strength), .88 (Spiritual Change), and .77 (Appreciation of Life). The male mean PTGI score of 65.71 (SD = 12.27) is less than the female mean of 70.02 (SD = 11.50), but not significantly less, t (106) = 1.93, p = .056, α = .05 (2-tail). A single significant gender difference was found among subscale scores between the male mean RTO score, M = 21.27 (SD = 6.05) and the corresponding female mean, M = 24.46 (SD = 5.51), t (106) = 2.87, p = .005, α = .01 (Bonferroni-corrected 2-tail). Subsequent analyses of PTGI scores in the sample of the current study are based on the combined scores shown in Table 3.

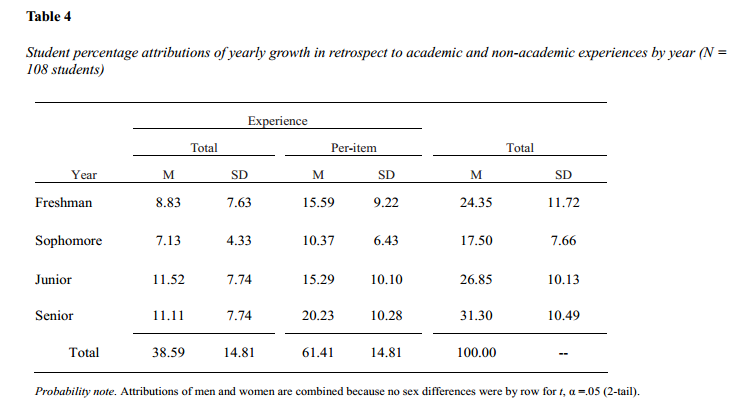

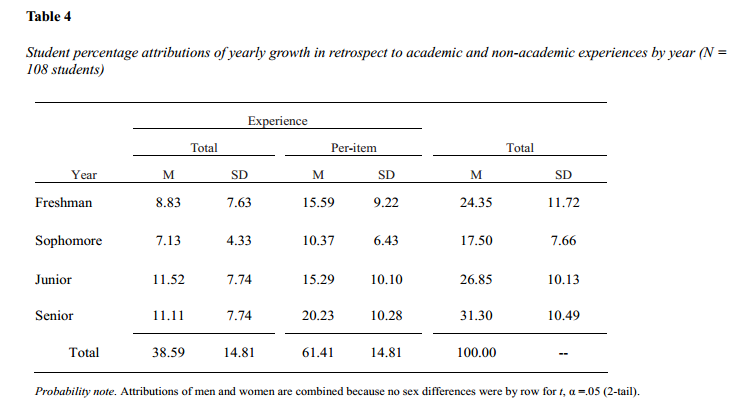

No gender differences were suggested by the results of independent t-tests of corresponding male and female percentages of total, academic, or non-academic growth, respectively, for any college year, α = .0125 (Bonferroni-corrected 2-tail for each set of 4 analyses). Therefore, subsequent analyses of percentages of growth are based on the combined scores in Table 4.

Table 3 contains the descriptive statistics for the sample of Study 2. A visual comparison of the contents of Table 3 with those of Table 1 shows that all corresponding entries are approximately equal. Table 4 documents mean attributions of substantial levels of personal growth to both academic and non-academic experiences for each of four years. The mean attribution to non-academic experiences exceeds the mean attribution to academic experiences for every year. The greatest mean growth is attributed to the senior year; the least is attributed to the sophomore year.

Participants were asked to identify the year of occurrence of the single experience (as defined by participants) to which they attributed the most personal growth (question not shown in Appendix B). Year and corresponding frequencies of selection by participants are: freshman (22), sophomore (9), junior (35), and senior (42). Participants also were asked to identify whether the experience that contributed most to growth was academic or non-academic. Type of experience and frequencies of selection are: academic (27) and non-academic (81). Finally, participants were asked to describe (in words) the experience that contributed most to their growth. Illustrative descriptions include: “getting a job,” “finding a new girlfriend,” “death of a friend,” “learning to live with fraternity brothers,” and “finishing my undergraduate thesis.”

Discussion

Measures

The current study is the fourth we have conducted based on the PTGI for measuring student personal growth and the third based on a table for collecting attributions of cause in the form of quantitative percentages and qualitative descriptions. We believe the results of the four studies support the utility of both measures for measuring growth and the flexibility of both for measuring growth under different circumstances.

College-Student Personal Growth

The mean PTGI score and standard deviation described by the 108 college seniors with a college career of exactly 8 semesters in the sample of Study 2, M = 68.01 (SD = 12.01) are almost identical to the corresponding statistics described by the 122 college students with a mean college career of 6.54 (SD = 1.34) semesters in the sample of Study 1, M = 69.09 (SD = 11.52). We had expected the mean PTGI score of Sample 2 to exceed that of Sample 1 because the results of our previous studies reflected higher mean scores for more college semesters (Anderson & Lopez-Baez, 2008, 2011; Study 1 of this paper). The simplest way to explain the similarity between the total scores of Study 1 and Study 2 is to remind ourselves that we are comparing data from a cohort as opposed to longitudinal studies, and remind ourselves that college student growth varies widely among students in each sample as illustrated by the large standard deviations for total PTGI scores in each of our studies. The results reflected in Table 4 suggest that the college seniors in our sample attributed substantial growth to both academic and non-academic experiences during all four college years. We believe this pattern is evidence that college faculty and staff can influence the personal growth of many students during every year of a student cohort’s progression toward graduation.

General Discussion

We believe Study 1 provides substantial information about the validity of total PTGI scores and also of subscale scores for Spiritual Change. For this reason, we believe the results of Study 1 are of interest to researchers using the PTGI to measure adversarial or personal growth. The high levels of personal growth attributed by students to the sum of their college years and attributions of cause to academic activities will probably interest college administrators and educators.

The same results led us to wonder how student growth and attributions of cause might be distributed over each college year. For this reason, Study 2 seemed a natural extension of Study 1. The descriptive results of Study 2 are among the first to reflect levels of growth attributed by graduating seniors in retrospect to each year of their undergraduate careers. We believe these results will also interest college personnel concerned with facilitating student growth.

We developed the table-based approach used in Studies 1 and 2 to measure attributions of cause. Researchers can adapt the approach for use in future studies of personal growth. We believe that researchers with other research interests can use a similar approach to study a wide variety of other variables.

Limitations

The two studies described in the current paper are based on self-reports. Thus, the results of both are subject to the many potential validity threats associated with self-reports including additional threats to the historical validity of retrospective self-reports. Our research purposes require data with sufficient internal validity. Comparisons of the results of our three studies reflect a degree of internal validity as described in Study 1. However, PTGI scores might be associated with ceiling effects if higher levels of growth are attributed to longer time periods at diminishing rates, and percentage attributions might be associated with recency effects if more vivid recall of recent experiences leads to larger attributions of growth. Finally, because our samples are representative of populations of similar students, but not university students in general, our conclusions do not necessarily apply beyond the population represented by our samples.

Future Research