Donghun Lee, Sojeong Nam, Jeongwoon Jeong, GoEun Na, Jungeun Lee

Despite advanced definitions and continued research on counselor burnout, attempts to investigate an expanded structure of counselor burnout remain limited. Using a serial mediation, the current study conducted a path analysis of a hypothesized process model using the five dimensions of the Counselor Burnout Inventory. Our research findings support the hypothesized sequential process model of counselor burnout, confirming full mediating effects of Deterioration in Personal Life, Exhaustion, and Incompetence in a serial order on the relationship between Negative Work Environment and Devaluing Client. Suggestions for future research and practical implications for counselors, supervisors, and directors are discussed.

Keywords: counselor burnout, serial mediation, path analysis, process model, Counselor Burnout Inventory

Burnout has received significant attention in counseling research because of the unique nature of counseling work (Bardhoshi et al., 2019; Bardhoshi & Um, 2021; Fye et al., 2020; J. J. Kim et al., 2018; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Early studies on burnout focused on defining burnout as a phenomenon. Freudenberger (1975), recognized as one of the pioneers in examining the burnout phenomenon, emphasized a loss of motivation and emotional exhaustion, defining it as “failing, wearing out, or becoming exhausted through excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources” (p. 73). Osborn (2004) placed an emphasis on physical and psychological reactions to job stress, describing burnout as “the process of physical and emotional depletion resulting from conditions at work or, more concisely, prolonged job stress” (p. 319). Maslach and colleagues have attempted to find a broader definition of burnout in their studies (Maslach & Jackson, 1981a, 1981b; Maslach et al., 1997, 2001; Maslach & Leiter, 2016) by conceptualizing three core dimensions of burnout—emotional exhaustion, a sense of reduced personal accomplishment, and depersonalization—as a syndrome of individuals exposed to long-term emotional and interpersonal stressors related to their job.

Many researchers have investigated burnout phenomenon, particularly among counselors, over several decades (Emerson & Markos, 1996; Evans & Villavisanis, 1997; W. C. McCarthy & Frieze, 1999; Malach-Pines & Yafe-Yanai, 2001). These studies have manifested additional focus on counselors’ actual performance in working with clients by describing counselor burnout as a state in which counselors experience considerable difficulties in performing proper functions and providing effective counseling. Kesler (1990) emphasized counselors’ internal psychological process in her definition of counselor burnout, defining it as a decreased sense of personal accomplishment in which an individual blames themself for their emotional and physical exhaustion, career fatigues, cynical attitudes toward clients, withdrawal from clients, and chronic depression and/or increased anxiety.

Further efforts have been made to better understand counselor burnout by examining the relationships of the three core dimensions—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. There is a common argument across burnout studies that emotional exhaustion is the central quality of burnout and the most obvious manifestation of the syndrome (Golembiewski & Munzenrider, 1988; R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Leiter & Maslach, 1988, 1999; Maslach, 1993, 1998). Researchers have articulated the relationships by positing that emotional exhaustion may first trigger depersonalization and depersonalization can then cause decreased personal accomplishment (Golembiewski & Munzenrider, 1988; R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Leiter & Maslach, 1988). Slightly different findings have suggested that exhaustion may simultaneously lead to depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Maslach, 1993). Some research has provided distinctive relationships among the three dimensions, indicating that emotional exhaustion may result from increased depersonalization (Golembiewski et al., 1986; Taris et al., 2005) and decreased personal accomplishment (Golembiewski et al., 1986).

In response to the need to establish a broader definition of counselor burnout, S. M. Lee and colleagues (2007) expanded the three-dimension model, previously introduced by Maslach and colleagues (1997), to consider organizational and personal sources of burnout. They added two dimensions—negative work environment and deterioration in personal life—to the three core dimensions of burnout, which advanced the model to a five-dimensional burnout model (S. M. Lee et al., 2007). Using the five dimensions, S. M. Lee and colleagues introduced the Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI). The CBI is the first scale aimed at measuring professional counselors’ burnout symptoms, integrating the expanded theoretical constructs of burnout with the five dimensions representative of the counseling profession (i.e., Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Client, and Deterioration in Personal Life). Several studies that have explored the psychometric characteristics of the CBI with diverse counselor populations working in a wide range of settings have demonstrated the solid validity and reliability of the CBI (Bardhoshi et al., 2019; J. Lee et al., 2010; S. M. Lee et al., 2007). For example, Bardhoshi et al. (2019) conducted a meta-analysis of 12 studies that utilized the CBI to examine its psychometric characteristics. Their psychometric synthesis reported robust internal consistency, external validity, and structural validity of the five dimensions of burnout across diverse groups of professional counselors, supporting the CBI’s suitability as a tool for understanding the multidimensional burnout phenomenon.

The Current Study

Despite such advanced definitions and continued research on counselor burnout, attempts to understand the expanded structure of counselor burnout using all five dimensions remain limited. The CBI has demonstrated its fitness in burnout research using the five dimensions, especially to explore the relationships among the dimensions and to understand the sequential process of them. Understanding this underlying sequential process will allow counseling professionals to detect burnout-related symptoms earlier and develop prevention and intervention plans accordingly (Gil-Monte et al., 1998;

R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Noh et al., 2013).

Therefore, the current study aimed to evaluate a hypothesized sequential process model of the five dimensions of counselor burnout syndrome using the CBI, which consists of (a) Negative Work Environment, (b) Deterioration in Personal Life, (c) Exhaustion, (d) Incompetence, and (e) Devaluing Client. Our overarching goal was to enrich the literature by providing a foundation on which to develop an integrative theoretical process model of counselor burnout. The following research questions guided the current study:

1) What are the relationships among the five dimensions of counselor burnout measured by the CBI?

2) Is the relation between Negative Work Environment and Devaluing Client mediated by Deterioration in Personal Life, Exhaustion, and Incompetence in a serial order?

Conceptual Framework

The current study presents a hypothesized sequential process of counselor burnout using the five dimensions of burnout measured by the CBI. Below we provide the rationale for our proposed serial order of counselor burnout, which is: 1) Negative Work Environment, 2) Deterioration in Personal Life, 3) Exhaustion, 4) Incompetence, and 5) Devaluing Client.

The first dimension, Negative Work Environment, reflects counselors’ attitudes and feelings toward their work environments beyond personal and interpersonal issues (S. M. Lee et al., 2007). Previous studies identified organizational factors as an early indicator of burnout among counselors, such as excessive work demands, role ambiguity and conflict, lack of recognition, limited supervisor and colleague support, poor relationships at work, and unfair decision-making (Demerouti et al., 2001; N. Kim & Lambie, 2018; Leiter & Maslach, 1988; Maslach & Leiter, 2008; C. McCarthy et al., 2010; Walsh & Walsh, 2002). These factors were found to be correlated with feelings of burnout and were identified as predictive factors for counselor burnout (N. Kim & Lambie, 2018).

The second dimension of the CBI, Deterioration in Personal Life, recognized as another early indicator of burnout, significantly predicts a wide range of burnout syndromes. This dimension refers to the counselors’ failure to maintain well-being in their personal lives by spending insufficient time with family and friends and having poor boundaries between work and personal life. Deterioration in Personal Life was positively associated with the Exhaustion subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), accounting for the high number of counselors’ levels of burnout (S. M. Lee et al., 2007). In terms of the sequential order between the two major indicators of counselor burnout, we posited that a negative work environment precedes deterioration in personal life. A negative work environment, with characteristics such as excessive workload, role ambiguity and conflict, and a lack of supervisor and colleague support, may restrict counselors’ personal lives by reducing personal time for their own wellness. When personal time conflicts with an unfavorable work environment and demand, counselors may not easily find a balance between work and life, thus experiencing reduced quality of life and emotional and physical exhaustion as consequences.

Exhaustion, the third dimension of burnout, represents counselors’ physical and emotional depletions that result from excessive workloads and conflictive relationships at work. Exhaustion is the central quality of burnout (Maslach & Leiter, 2008), accompanied by feelings of being drained and emotionally overextended (Maslach, 1998). As many researchers have argued that exhaustion precedes other dimensions of burnout (Leiter & Maslach, 1999; Maslach et al., 1997, 2001; Maslach & Leiter, 2016), the core idea penetrating throughout their arguments is that emotional exhaustion occurs first, followed by reduced personal accomplishment and depersonalization.

Therefore, we proposed that the fourth and fifth dimensions—Incompetence and Devaluing Client, respectively—may be consequences that stem from counselors’ emotional and physical exhaustion. In the CBI, Incompetence refers to a counselor’s internal feeling of incompetence while evaluating their effectiveness as a professional counselor, and it represents their belief that they are an incompetent counselor or that they are failing to make a positive change in their clients. Previous studies have provided evidence that emotional exhaustion increases professional incompetence or inefficacy (R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Park & Lee, 2013; van Dierendonck et al., 2001). R. T. Lee and Ashforth (1993) insisted that emotional exhaustion increases the possibility of reducing one’s personal accomplishment while also directly causing depersonalization. The last dimension, Devaluing Client, is a counselor’s attitude and perception of their relationship with clients. It describes counselors’ callous attitudes toward clients, such as little empathy for, or no concern about, the welfare of their clients. S. M. Lee et al. (2007) reported that the Devaluing Client dimension was positively correlated with the Depersonalization subscale of the MBI, defined as “a negative, cynical, or excessively detached response to other people” (Maslach, 1998, p. 69).

Regarding the sequence between Exhaustion and the two dimensions of consequence, we postulated that Devaluing Client is the final stage of the burnout developmental model, suggesting that exhaustion triggers feelings of incompetence first, which in turn results in counselors’ actual behavior of devaluing clients. Emotional and physical exhaustion is a major direct threat to counselors’ competencies in providing quality services to their clients (R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Park & Lee, 2013; van Dierendonck et al., 2001), while devaluing clients—treating clients as objects—can be viewed as an emotional coping strategy to deal with the frustration derived from emotional depletion (Gil-Monte et al., 1998). Emotional exhaustion may therefore increase counselors’ feelings of incompetence and then exacerbate their detachment from clients to the point where they become callous toward and no longer interested in their clients (R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Leiter & Maslach, 1988; Taris et al., 2005). Thus, we posited that devaluing clients is the final crucial manifestation of the phenomenon among counselors who have experienced prolonged burnout, leading many of them to consider leaving the counseling profession.

In summary, we proposed an integrative process model of counselor burnout that comprises the following stages in sequence: 1) Negative Work Environment, 2) Deterioration in Personal Life,

3) Exhaustion, 4) Incompetence, and 5) Devaluing Client. That is, professional counselors who work in a negative work environment for an extended period may start to experience a deterioration in their personal lives, which could lead counselors to emotional and physical exhaustion. Counselors exposed to prolonged exhaustion may also feel a lack of competence in counseling, which may make them prone to becoming callous toward their clients. Figure 1 depicts this serial process model of counselor burnout.

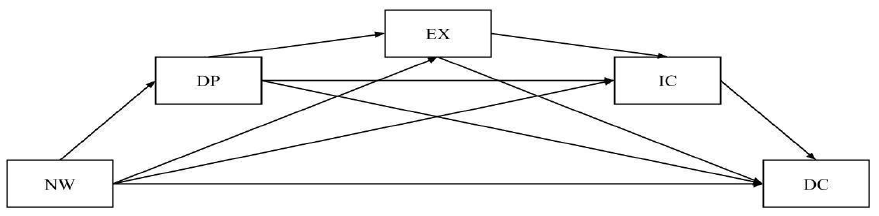

Figure 1

Saturated Model of Counselor Burnout Process

Note. NW = Negative Work Environment, DP = Deterioration in Personal Life, EX = Exhaustion, IC = Incompetence, DC = Devaluing Client.

Methods

Procedure

Upon IRB approvals from two different institutions, mass email invitations were sent to professional counselors affiliated with professional counseling associations (i.e., the American Counseling Association [ACA] and the American School Counselor Association [ASCA]). The email invitations contained a description of the study, proof of IRB approval, informed consent, and a link to a self-reported survey. Prior to responding to the web-based survey, participants were asked to review their consent information. Those who agreed to take part in the survey were asked to respond to a demographic questionnaire, followed by the CBI (S. M. Lee et al., 2007). All measures and forms were coded with the participants’ identification numbers to protect their privacy. Email addresses submitted by those who wanted to be entered into a drawing for compensation were stored in a separate database from the survey responses. Of the 428 participants who completed the online survey, we eliminated 69 who ceased their participation or did not fully complete the survey. As a result, 359 were included in the final data analysis.

Participants

A total of 359 professional counselors who were currently practicing and affiliated with one or more professional counseling-related association(s) participated in the current study. In terms of demographics, 281 participants self-identified as female (78.3%) and 76 as male (21.2%), in addition to two participants who did not want to respond (0.5%). With regard to racial/ethnic identity, the majority of the participants self-identified as White (n = 270, 75.2%). Thirty-three participants identified themselves as African American (9.2%), 20 as Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander (5.6%), 19 as Hispanic (5.3%), and two as Native American (0.6%). The participants were employed in K–12 school (n = 123, 34.3%), outpatient (n = 76, 21.2%), private practice (n = 66, 18.4%), counselor education (n = 37, 10.3%), university counseling (n = 22, 6.1%), medical/psychiatric hospital (n = 11, 3.1%), or other (n = 24, 6.7%) settings. Years of experience ranged from 1 to 47 years, with a mean of 11.4 and standard deviation of 9.6. The participants displayed diverse specialties, including school counseling (42.9%), mental health counseling (42.9%), marriage and family therapy (4.6%), rehabilitation counseling (3.7%), and other disciplines (5.8%).

Measures

Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI)

The CBI (S. M. Lee et al., 2007), a 20-item self-report inventory used to assess professional counselors’ burnout, consists of five dimensions: Exhaustion (e.g., “I feel exhausted due to my work as a counselor”), Incompetence (e.g., “I am not confident in my counseling skills”), Negative Work Environment (e.g., “I feel frustrated with the system in my workplace”), Devaluing Client (e.g., “I am not interested in my clients and their problems”), and Deterioration in Personal Life (e.g., “My relationships with family members have been negatively impacted by my work as a counselor”). These five dimensions reflect the characteristics of feelings and behaviors that indicate various levels of burnout among counselors. The CBI asks participants to rate the relevance of the statements on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (always true). S. M. Lee et al. (2007) reported that Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of internal consistency reliability were .80 for the Exhaustion subscale, .83 for the Negative Work Environment subscale, .83 for the Devaluing Client subscale, .81 for the Incompetence subscale, and .84 for the Deterioration in Personal Life subscale. The current study obtained Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .89 for Exhaustion, .87 for Negative Work Environment, .77 for Devaluing Client, .78 for Incompetence, and .84 for Deterioration in Personal Life.

Data Analysis

We first explored descriptive statistics of demographic variables to understand the sample characteristics, including gender, race, age, employment status, work setting, specialty, and years of experience. Missing values were imputed using predictive mean matching, which estimates missing values by matching to the observed values in the sample (Rubin, 1986).

To examine relationships among the five dimensions, we conducted a correlation analysis. After identifying the correlation matrix, which confirmed significant relationships among the five dimensions, we tested the hypothesized process model with a serial mediation using a path analysis. The ratio of response-to-parameter was 18:1 for the data, which satisfies the minimum amount of data for conducting a path analysis (Kline, 2015). Because the variables did not follow normality according to the Shapiro-Wilk test, skewness and kurtosis, and plots, we used weighted least squares. We started with a saturated model in which all possible direct paths were identified (Figure 1). Using the trimming method introduced by Meyers and colleagues (2013), we successively removed the least statistically significant path from the previous model until we found a model with all significant paths. To assess the model goodness of fit, model fit indices, including root mean square error residual (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were evaluated. The RMSEA and SRMR values ≤ .06 indicate excellent fit, and CFI and TLI values ≥ .95 indicate excellent fit. All analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (R Core Team, 2022).

Results

Pairwise Correlation Analysis

Table 1 depicts the results of the pairwise correlation analysis. Significant positive correlations were found among the five dimensions of burnout. The relationship between Deterioration in Personal Life and Exhaustion was the largest, while that between Deterioration in Personal Life and Devaluing Client was the smallest. Also notable was that Devaluing Client, which is the dependent variable in the serial mediation model, displayed weak relationships with Negative Work Environment, Deterioration in Personal Life, and Exhaustion, but a moderate relationship with Incompetence.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

| Variable | n | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1. Negative Work Environment | 359 | 9.91 | 3.75 | — | ||||

| 2. Deterioration in Personal Life | 359 | 9.46 | 3.52 | .35** | — | |||

| 3. Exhaustion | 359 | 11.84 | 3.54 | .43** | .58** | — | ||

| 4. Incompetence | 359 | 8.67 | 2.56 | .23** | .35** | .33** | — | |

| 5. Devaluing Client | 359 | 5.52 | 1.94 | .23** | .22** | .27** | .40** | — |

| **p < .01 |

Path Analysis

The first model was identified drawing all possible direct paths among the variables (Table 2). Model fit indices were not calculated, as this is a saturated model. This model indicated that four of the 10 direct paths were not statistically significant, with p values ranging from .065 to .145.

Table 2

Results of a Path Analysis: Saturated Model

| Endogenous Variables | Exploratory Variables | Estimate | Standardized Estimate | p | SMC |

| Deterioration in Personal Life | Negative Work Environment | 0.321 | 0.049 | .000 | 0.117 |

| Exhaustion | Negative Work Environment | 0.248 | 0.043 | .000 | 0.386 |

| Deterioration in Personal Life | 0.483 | 0.046 | .000 | ||

| Incompetence | Negative Work Environment | 0.056 | 0.038 | .145 | 0.146 |

| Deterioration in Personal Life | 0.153 | 0.044 | .000 | ||

| Exhaustion | 0.125 | 0.045 | .006 | ||

| Devaluing Client | Negative Work Environment | 0.050 | 0.029 | .082 | 0.188 |

| Deterioration in Personal Life | −0.003 | 0.035 | .930 | ||

| Exhaustion | 0.069 | 0.037 | .065 | ||

| Incompetence | 0.254 | 0.037 | .000 |

Note. SMC = squared multiple correlation.

Among them, the path connecting Deterioration in Personal Life to Devaluing Client (p = .930) was the least significant. According to the trimming process, this path was removed to identify modified Model 1. The modified Model 1 was found to include two nonsignificant paths, connecting Negative Work Environment to Incompetence (p = .145) and Negative Work Environment to Devaluing Clients

(p = .082). The path connecting Negative Work Environment to Incompetence was less significant, and it was removed from the modified Model 1 to fit modified Model 2. The modified Model 2 identified only one path that was not significant (p = .050), which connected Negative Work Environment to Devaluing Client. This path was eliminated to identify modified Model 3. The modified Model 3 finally rendered significant direct paths only with excellent model fit indices, and it was retained as the final model (Table 3). Model fit indices of all the models are described in Table 4.

Table 3

Results of a Path Analysis: Retained Model

| Endogenous Variables | Exploratory Variables | Estimate | Standardized Estimate |

p | SMC |

| Deterioration in Personal Life | Negative Work Environment | 0.311 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.110 |

| Exhaustion | Negative Work Environment | 0.255 | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.398 |

| Deterioration in Personal Life | 0.491 | 0.046 | 0.000 | ||

| Incompetence | Deterioration in Personal Life | 0.176 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 0.146 |

| Exhaustion | 0.136 | 0.044 | 0.002 | ||

| Devaluing Client | Exhaustion | 0.082 | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.193 |

| Incompetence | 0.273 | 0.033 | 0.000 |

Note. SMC = squared multiple correlation.

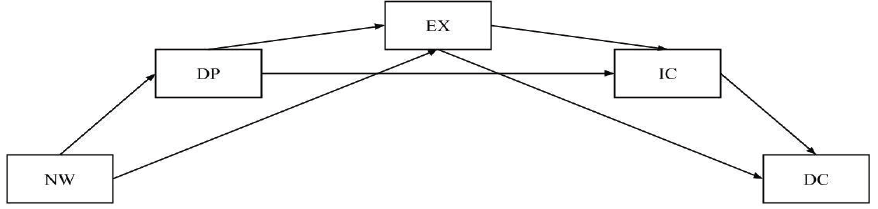

In the retained model (Figure 2), the indirect effect involving all three mediators, Deterioration in Personal Life, Exhaustion, and Incompetence, were found to be significant in a serial chain. The total effect of Negative Work Environment on Devaluing Clients was significant (standardized estimate = .269, p = .000), but the direct effect of Negative Work Environment on Devaluing Clients was not significant (standardized estimate = .062, p = .402). The ratio of the total indirect effect to the total direct effect was .273, and the proportion of the total effect mediated was .125. Among the indirect effects involving one or two of the three mediators, only the paths through Deterioration in Personal Life and Incompetence and the path through Exhaustion and Incompetence were found to be significant (p < .05).

Figure 2

Retained Model of Counselor Burnout Process

Note. NW = Negative Work Environment, DP = Deterioration in Personal Life, EX = Exhaustion, IC = Incompetence, DC = Devaluing Client.

Table 4

Goodness of Fit Indices

| Model | χ2 | df | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

| Saturated model | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Modified model 1 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.071 |

| Modified model 2 | 2.168 | 2.000 | 0.997 | 0.981 | 0.015 | 0.019 | 0.999 | 0.994 |

| Modified model 3 (retained) | 6.104 | 3.000 | 0.993 | 0.964 | 0.054 | 0.033 | 0.978 | 0.926 |

Note. AGFI = adjusted goodness of fit index; CFI = comparative normed fit index; df = degree of freedom; GFI = goodness of fit index; RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index.

Discussion

This study examined a process model of counselor burnout in the work context by analyzing our proposed serial mediation model. The findings support the hypothesized sequential process model of counselor burnout by confirming the full mediating effects of Deterioration in Personal Life, Exhaustion, and Incompetence in a serial order on the relationship between Negative Work Environment and Devaluing Client.

The final model describes the mechanism of counselor burnout, pertaining to how it starts and proceeds to the point where clients are affected. In the proposed model, Negative Work Environment, an external factor that counselors are usually not able to control, may affect counselors’ experiences not only at work but also in their personal lives. This is consistent with previous findings in which counselors exposed to unfavorable work environments for an extended period tended to have poor boundaries between work and life and thus failed to maintain well-being in their personal lives (Leiter & Durup, 1996; Puig et al., 2012). Limited ability to find a balance between work and personal life because of negative work-related factors such as an excessive workload may affect the overall quality of life, resulting in emotional and physical depletion among counselors. Accordingly, in the final model, Exhaustion was predicted by Negative Work Environment through Deterioration in Personal Life. Exhaustion then predicted counselors’ feelings of incompetence as hypothesized. Being emotionally and physically exhausted, counselors may experience a reduced sense of self-competence and self-view as professional counselors, which may also influence their actual performance. The final model depicted that the feelings of incompetence predicted Devaluing Client, indicating counselors were unable to emotionally connect with their clients and thus lost interest in their clients’ welfare. Our findings supported previous studies (Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Maslach et al., 2001; Park & Lee, 2013; Taris et al., 2005; van Dierendonck et al., 2001) that found causal relationships between exhaustion and reduced accomplishment, as well as between exhaustion and depersonalization. For example, several researchers have argued that exhaustion may decrease professionals’ self-efficacy in providing quality services to their clients and that it may also increase depersonalization, in which they feel indifferent toward their work and the people with whom they work (R. T. Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Maslach et al., 2001; Park & Lee, 2013; Taris et al., 2005; van Dierendonck et al., 2001).

Lastly, our serial process model confirmed Devaluing Client to be the final stage of counselor burnout, predicted by Negative Work Environment through Deterioration in Personal Life, Exhaustion, and Incompetence. According to Maslach (1998), devaluing clients (i.e., a cynical attitude and feelings toward work and clients) begins with the action of distancing oneself emotionally and cognitively from one’s work, which can be a way to cope with emotional exhaustion. In fact, emotional detachment from work can be viewed as somewhat functional and even a necessary action to take to maintain effectiveness as a professional (Gil-Monte et al., 1998; Golembiewski et al., 1986). Maintaining proper emotional distance from clients and creating a clear boundary from work may act as an effective coping strategy for dealing with emotional and physical exhaustion. However, emotional detachment from work, despite its virtue as a potential coping strategy and an ethical practice (Gil-Monte et al., 1998), can be aggravated by emotional exhaustion through the perceived lack of competence as professional counselors. Such a detached attitude may lead counselors to become callous toward clients and to contemplate leaving the counseling profession (Cook et al., 2021). As the process model indicates, a negative work environment could significantly affect counselors’ social, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral aspects in order, which may harm their clients and the profession.

In addition to the mechanism of counselor burnout involving all dimensions with three mediators, the final model also identified effects involving a part of the five dimensions (Figure 2). Among those, a significant finding relates to the one without Exhaustion. According to the model, without Exhaustion, Negative Work Environment may still lead counselors to devalue clients through the deterioration in their personal lives and the feeling of incompetence. This finding is significant given that a variety of burnout theories and research have posited exhaustion as a key concept of burnout, insisting that emotional and physical depletion of counselors would lead up to feelings of incompetence and devaluing clients (Leiter & Maslach, 1999; Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Maslach et al., 2001; Park & Lee, 2013). Distinguishably, our findings suggest that, even when counselors do not necessarily experience emotional and physical exhaustion or are not aware of such experiences, counselors who work in unfavorable work environments that negatively impact their personal lives for a long period (Puig et al., 2012) may feel unable to maintain their effectiveness as professionals (Bandura & National Institute of Mental Health, 1986; Hattie et al., 2004) and thus become callous toward their work and clients (Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

Implications

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first attempt to acquire an in-depth understanding of a process model of counselor burnout using the five dimensions of burnout. The present study introduced a model that depicts the sequential process among the five dimensions of counselor burnout, indicating how counselor burnout may develop from their experiences at work as counselors to the point where they may harm their clients. Our research findings suggest important practical implications for counselors, clinical supervisors, and counseling center directors.

Implications for Counselors

The findings first enrich counselors’ understanding of their experiences of burnout and allow them to reflect on how they can relate themselves to each stage of the model. Counselors may use this model to examine their environments and experiences and to engage in self-reflection, assessing whether they have any signs of burnout. A single experience that may not have always necessarily been considered an indication of being in a developmental phase of counselor burnout, such as a limited number of coworkers who can provide case consultation (i.e., negative work environment) or reduced quality time with family and friends because of limited free time (i.e., deterioration in personal life), can now be perceived as early signs of counselor burnout that require intervention. This means that they may still be in the early phases and have the potential to bounce back if they seek help and receive early intervention. Given the gravity of more severe symptoms of burnout (i.e., incompetence and devaluing clients), counselors may utilize this model to detect the early signs of counselor burnout and develop strategies, such as self-care or help-seeking plans, so they can avoid progressing to the later phases of counselor burnout. Failing to take immediate action and receive appropriate help can lead to a serious problem, resulting in not only violating ethical obligations given to all counselors but also potentially harming clients. Specifically, counselors exhibiting the symptom of devaluing clients but failing to take any action may violate the two core values of the counseling profession: “nonmaleficence” and “beneficence” (ACA, 2014). The ACA Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014) states that professional counselors should avoid causing harm to their clients and work for the good of the clients by promoting their mental health and well-being. By devaluing clients as a result of experiencing burnout, counselors would essentially devastate the therapeutic relationship with their clients (Garner, 2006), impair their own ability to promote clients’ well-being (i.e., violation of beneficence), and ultimately cause serious harm to the clients (i.e., violation of nonmaleficence).

Implications for Clinical Supervisors

As counselors take primary responsibility for detecting the symptoms of burnout to maintain their optimal effectiveness, supervisors should continue to support them by guaranteeing adequate supervision and continuing education that provides an opportunity to discuss burnout experiences. Supervisors may set aside time during the supervision sessions for genuine discussions to help counselors better address their burnout and encourage them to regularly adopt the sequential model of the current study to assess their experience pertaining to the five dimensions. Continuing education may focus on the early warning signs of burnout, which in the current study were negative work environment and deterioration in personal life, so that supervisees can take immediate action when detecting the signs of burnout. Encouraging counselors to monitor their sudden changes and stressors at work and in their personal life and maintain a balance between them could help them seek support from supervisors and professional counseling. Relatedly, when counselors show the cognitive and behavioral patterns of devaluing clients, which is the last element in the sequential process of counselor burnout, supervisors should take immediate actions to protect both clients and counselors (ACA, 2014; Dang & Sangganjanavanich, 2015) because it may signal more serious levels of burnout. Therefore, supervisors need to maintain an open and inviting atmosphere to not only allow conversations when supervisees feel less empathetic toward their clients or disinterested in their clients’ lives, but also initiate further discussions for creating intervention strategies that are effective at mitigating impairment caused by burnout (Merriman, 2015). Supervisors should be mindful that some counselors may be reluctant to discuss their burnout symptoms with their supervisors because of fear of a negative evaluation. Having a conversation regarding their burnout in a more confidential relationship, such as counseling, would be more effective and safer for the counselors to evaluate their impairment accurately and take actions as necessary.

Implications for Counseling Center Directors

According to our findings, without necessarily going through the stage of emotional and physical exhaustion, negative work environment can have tremendous negative impacts on counselors’ overall competencies. This finding stresses the role of directors of counseling centers to create a positive work environment for counselors. First, the directors may periodically examine counselors’ perceptions of their work environment to determine whether they feel frustrated with the working system or perceive any unfair treatment (e.g., excessive workload, limited resources, unfair decision-making). For instance, they could hold a monthly meeting to listen to counselors’ difficulties and discuss improvement opportunities in the system. Paying attention to counselors’ difficulties and feedback can be critical to not only making system improvements but also building healthy relationships among members of the environment. The directors may take a careful look at their counselors’ caseloads and maintain a reasonable counselor-to-client ratio to prevent burnout and create a working environment that allows for the best services for their clients.

Second, counseling center directors can prevent or reduce counselors’ burnout by providing professional development opportunities. Counselors have experienced rapid changes in terms of counseling modalities and strategies and may feel inadequately prepared to meet the unique needs of their clients, which can result in counselor burnout. Therefore, it is beneficial for counselors to engage in professional development activities, such as workshops, continuing education, and conferences, to expand their knowledge and skills. These types of opportunities can reduce counselors’ feelings of incompetence and prevent them from progressing to the last phase (devaluing clients), even if the counselors are in the later phases of burnout.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study provides an in-depth understanding of the expanded developmental model of counselor burnout and suggests significant implications for the counseling profession. Nevertheless, there are some limitations in the current study. First, although our research participants represented the overall characteristics of the counseling population fairly, future research should contain counselors from diverse backgrounds with regard to demographics, work settings, or specialties. Increased diversity could help us understand the unique burnout phenomenon among counselor populations working in various settings and with diverse clients.

Second, this study examined the sequential model of counselor burnout within the structure of the five subfactors of the CBI (S. M. Lee et al., 2007), including Negative Work Environment, Deterioration in Personal Life, Exhaustion, Incompetence, and Devaluing Client. Further investigation should involve external variables to explore what may contribute to the development of counselor burnout and how it may affect the counseling process and outcomes.

Lastly, a longitudinal study is necessary to capture the extended understanding of the sequential development model of counselor burnout, given that time may be a critical factor that influences burnout among professionals. By conducting a longitudinal study, counseling professionals will be able to detect the advancement of burnout and take immediate action to initiate prevention and intervention plans.

Conclusion

Professional counselors who work in a negative work environment for an extended period may start to experience a deterioration in their personal lives, which could lead counselors to emotional and physical exhaustion. Counselors exposed to prolonged exhaustion may also feel a lack of competence in counseling, which may make them prone to becoming callous toward their clients. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first attempt to acquire an expanded understanding of a process model of counselor burnout using the five dimensions of burnout. The research findings validated the aforementioned hypothesized process model of counselor burnout, suggesting how counselor burnout may develop from their experiences at work to the point where they may harm their clients. Counselors may utilize this model to detect the early signs of counselor burnout and to develop strategies, such as self-care or help-seeking plans, so they can avoid progressing to the later phases of counselor burnout. Failing to take immediate action and receive appropriate help can lead to a serious problem, resulting in not only violating ethical obligations given to all counselors but also potentially harming clients. Supervisors and counseling center directors may set aside time for genuine discussions to help counselors better address their burnout and encourage them to regularly adopt the sequential model of the current study to assess their experience pertaining to the five dimensions.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Bandura, A., & National Institute of Mental Health. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

Bardhoshi, G., Erford, B. T., & Jang, H. (2019). Psychometric synthesis of the Counselor Burnout Inventory. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12250

Bardhoshi, G., & Um, B. (2021). The effects of job demands and resources on school counselor burnout: Self-efficacy as a mediator. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(3), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12375

Cook, R. M., Fye, H. J., Jones, J. L., & Baltrinic, E. R. (2021). Self-reported symptoms of burnout in novice professional counselors: A content analysis. The Professional Counselor, 11(1), 31–45.

https://doi.org/10.15241/rmc.11.1.31

Dang, Y., & Sangganjanavanich, V. F. (2015). Promoting counselor professional and personal well-being through advocacy. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 2(1), 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2015.1007179

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Emerson, S., & Markos, P. A. (1996). Signs and symptoms of the impaired counselor. The Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 34(3), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4683.1996.tb00335.x

Evans, T. D., & Villavisanis, R. (1997). Encouragement exchange: Avoiding therapist burnout. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 5(4), 342–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480797054013

Freudenberger, H. J. (1975). The staff burn-out syndrome in alternative institutions. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 12(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086411

Fye, H. J., Cook, R. M., Baltrinic, E. R., & Baylin, A. (2020). Examining individual and organizational factors of school counselor burnout. The Professional Counselor, 10(2), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.15241/hjf.10.2.235

Garner, B. R. (2006). The impact of counselor burnout on therapeutic relationships: A multilevel analytic approach [Doctoral dissertation, Texas Christian University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Gil-Monte, P. R., Peiro, J. M., & Valcárcel, P. (1998). A model of burnout process development: An alternative from appraisal models of stress. Comportamento Organization E Gestao, 4(1), 165–179.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263043320

Golembiewski, R. T., & Munzenrider, R. F. (1988). Phases of burnout: Developments in concepts and applications. Praeger.

Golembiewski, R. T., Munzenrider, R. F., & Stevenson, J. G. (1986). Stress in organizations: Toward a phase model of burnout. Praeger.

Hattie, J. A., Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2004). A factor structure of wellness: Theory, assessment, analysis, and practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(3), 354–364.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00321.x

Kesler, K. D. (1990). Burnout: A multimodal approach to assessment and resolution. Elementary School Guidance and Counseling, 24(4), 303–311.

Kim, J. J., Brookman-Frazee, L., Gellatly, R., Stadnick, N., Barnett, M. L., & Lau, A. S. (2018). Predictors of burnout among community therapists in the sustainment phase of a system-driven implementation of multiple evidence-based practices in children’s mental health. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000182

Kim, N., & Lambie, G. W. (2018). Burnout and implications for professional school counselors. The Professional Counselor, 8(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.15241/nk.8.3.277

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford.

Lee, J., Wallace, S., Puig, A., Choi, B. Y., Nam, S. K., & Lee, S. M. (2010). Factor structure of the Counselor Burnout Inventory in a sample of sexual offender and sexual abuse therapists. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 43(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175610362251

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1993). A longitudinal study of burnout among supervisors and managers: Comparisons between the Leiter and Maslach (1988) and Golembiewski et al. (1986) models. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 54(3), 369–398. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1993.1016

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123

Lee, S. M., Baker, C. R., Cho, S. H., Heckathorn, D. E., Holland, M. W., Newgent, R. A., Ogle, N. T., Powell, M. L., Quinn, J. J., Wallace, S. L., & Yu, K. (2007). Development and initial psychometrics of the Counselor Burnout Inventory. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 40(3), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2007.11909811

Leiter, M. P., & Durup, M. J. (1996). Work, home, and in-between: A longitudinal study of spillover. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 32(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886396321002

Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (1988). The impact of interpersonal environment on burnout and organizational commitment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 9(4), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030090402

Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (1999). Six areas of worklife: A model of the organizational context of burnout. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 21(4), 472–489. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/12693291

Malach-Pines, A., & Yafe-Yanai, O. (2001). Unconscious determinants of career choice and burnout: Theoretical model and counseling strategy. Journal of Employment Counseling, 38(4), 170–184.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2001.tb00499.x

Maslach, C. (1993). Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 19–32). Taylor and Francis.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263847970

Maslach, C. (1998). A multidimensional theory of burnout. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Theories of organizational stress (pp. 68–85). Oxford University Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280939428

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981a). The Maslach Burnout Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981b). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (2018). The Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (4th ed.). Mind Garden. https://www.mindgarden.com/maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi/685-mbi-manual.html

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

McCarthy, C., Van Horn Kerne, V., Calfa, N. A., Lambert, R. G., & Guzmán, M. (2010). An exploration of school counselors’ demands and resources: Relationship to stress, biographic, and caseload characteristics. Professional School Counseling, 13(3), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1001300302

McCarthy, W. C., & Frieze, I. H. (1999). Negative aspects of therapy: Client perceptions of therapists’ social influence, burnout, and quality of care. Journal of Social Issues, 55(1), 33–50.

https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00103

Merriman, J. (2015). Enhancing counselor supervision through compassion fatigue education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(3), 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12035

Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G. C., & Guarino, A. J. (2013). Performing data analysis using IBM SPSS. Wiley.

Noh, H., Shin, H., & Lee, S. M. (2013). Developmental process of academic burnout among Korean middle school students. Learning and Individual Differences, 28, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.09.014

Osborn, C. J. (2004). Seven salutary suggestions for counselor stamina. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(3), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00317.x

Park, Y. M., & Lee, S. M. (2013). A longitudinal analysis of burnout in middle and high school Korean teachers. Stress and Health, 29(5), 427–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2477

Puig, A., Baggs, A., Mixon, K., Park, Y. M., Kim, B. Y., & Lee, S. M. (2012). Relationship between job burnout and personal wellness in mental health professionals. Journal of Employment Counseling, 49(3), 98–109.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2012.00010.x

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Rubin, D. B. (1986). Statistical matching using file concatenation with adjusted weights and multiple imputations. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 4(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1391390

Taris, T. W., Le Blanc, P. M., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2005). Are there causal relationships between the dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory? A review and two longitudinal tests. Work & Stress, 19(3), 238–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500270453

van Dierendonck, D., Schaufeli, W. B., & Buunk, B. P. (2001). Burnout and inequity among human service professionals: A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 43–52.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.43

Walsh, B., & Walsh, S. (2002). Caseload factors and the psychological well-being of community mental health staff. Journal of Mental Health, 11(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/096382301200041470

Donghun Lee, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Sojeong Nam, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at The University of New Mexico. Jeongwoon Jeong, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at The University of New Mexico. GoEun Na, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at The City University of New York at Hunter College. Jungeun Lee, PhD, LPC, LPC-S, is a clinical professor at the University of Houston. Correspondence may be addressed to Donghun Lee, 501 W. Cesar E. Chavez Blvd., Durango Building 4.304, San Antonio, TX 78207, donghun.lee@utsa.edu.