Taylor J. Irvine, Adriana C. Labarta

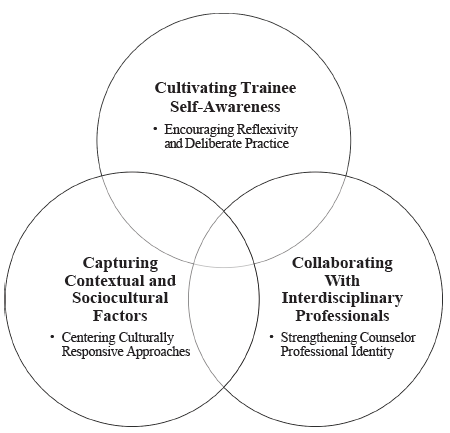

Eating disorders (EDs) are increasingly prevalent and pose significant public health challenges. Yet, deficits exist in counselor education programs regarding ED assessment, conceptualization, and treatment. Consequently, counselors report feeling incompetent and distressed when working with ED clients. We propose a conceptual framework, the 3 Cs of ED Education and Training, to enhance trainee development. The 3 Cs are: (a) cultivating trainee self-awareness through reflexivity and deliberate skill practice, (b) capturing contextual and sociocultural factors with culturally responsive approaches, and (c) collaborating with interdisciplinary ED professionals while strengthening counselor professional identity. Implications for counselor educators include incorporating activities aligned with this framework into curriculum and experiential training in order to facilitate trainee competence in ED assessment and treatment.

Keywords: eating disorders, 3 Cs of ED Education and Training, framework, counselor education, trainee development

Eating disorders (EDs) remain one of the most lethal mental health illnesses, contributing to roughly 3 million deaths globally each year (van Hoeken & Hoek, 2020) and impacting 29 million or 9% of Americans over their lifetime (Deloitte Consumer Report, 2020). In the United States alone, EDs directly result in 10,200 deaths annually, averaging one death every hour (Deloitte Access Economics, 2020). The steady rise of EDs across genders and countries is of increasing concern, with scholars noting in their systematic literature review that rates have doubled from 3.5% in 2000–2006 to 7.8% in 2013–2018 (Galmiche et al., 2019). EDs also exact a significant economic toll in the United States. In the 2018–2019 fiscal year, Streatfeild et al. (2021) found that EDs generated financial costs of nearly $65 billion, averaging about $11,000 per affected individual. Moreover, their study estimated an additional $326.5 billion in non-financial costs due to reduced well-being among those with EDs. Given their associated comorbidities with other mental health illnesses (Ulfvebrand et al., 2015), enduring somatic issues (Galmiche et al., 2019), and facilitation of psychological distress (Kärkkäinen et al., 2018), EDs pose significant public health and economic threats that necessitate further consideration. However, the literature lacks meaningful attention to ED prevention and treatment (van Hoeken & Hoek, 2020), an oversight that needs to be redressed within counselor education (CE) graduate training programs. A failure to examine this clinical issue threatens the maintenance of quality assurance and ethical standards within the profession, enabling short- and long-term client harm.

Challenges and Gaps in ED Education and Training

Given the steady rise in the prevalence of EDs and their associated consequences, counseling trainees must be equipped with comprehensive training in order to effectively conceptualize and treat these complex conditions. However, across the decades, research has illuminated ED education and training deficits, particularly in graduate programs (Biang et al., 2024; Labarta et al., 2023; Levitt, 2006; Thompson-Brenner et al., 2012). For instance, Labarta et al.’s (2023) recent study examined clinician attitudes toward treating EDs, revealing challenges related to the lack of specialized graduate training. Among surveyed respondents, only 25.7% reported that their programs offered a specialized course on EDs, while approximately half of the sample (41.3%) divulged that their program dedicated only 1–5 hours of ED-related instruction throughout the curricula. Furthermore, one participant indicated that ED education is “rarely more than one lecture at the master’s level” (Labarta et al., 2023, p. 21). This is particularly concerning as research shows that trainees are not only very likely to encounter a client battling an ED at some point in their professional career (Levitt, 2006) but are also going to be less prepared and effective in treating such clients without specialized ED training in graduate programs (Biang et al., 2024; Labarta et al., 2023).

As a result of this lack of ED education, scholars have noted negative implications for helping professions, contributing to clinician incompetence, increased burnout, and diminished self-efficacy when working with ED clients (Labarta et al., 2023; Levitt, 2006; Thompson-Brenner et al., 2012). Clinician competence is a necessary vehicle to not only promote individual accountability but to also ensure the integrity of the broader counseling profession. However, holistic competency development is threatened without adequate, targeted ED training, increasing the likelihood that counselors-in-training (CITs) will encounter recurring treatment failures when working with clients struggling with an ED (Williams & Haverkamp, 2010). Williams and Haverkamp (2010) echoed this sentiment, stating that the field risks the occurrence of “iatrogenesis . . . particularly when the practitioner has a poor understanding of EDs, the negative reactions that eating disordered clients can evoke in the clinician are not managed, and/or there are specific types of process and relationship errors made in therapy” (p. 92). For example, although a school counselor may not serve as the primary treatment provider for an adolescent with bulimia nervosa, their understanding of warning signs and symptoms, supportive collaboration with students and families, and knowledge of specialized community referrals are invaluable to the counseling process (Carney & Scott, 2012). As such, counselor educators must assist CITs with developing essential competencies for treating EDs during graduate training programs, ultimately working toward bridging this gap and improving the quality of care.

Addressing the deficit of multicultural research in the field of EDs is of paramount importance, as it directly impacts the practice and education of counselors. Accrediting and professional bodies expect counselor educators to impart multicultural knowledge and skills to CITs, including a focus on diverse cultural and social identities (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2023). Furthermore, Levitt (2006) emphasized that the significant consequences and growing prevalence of EDs across diverse cultural groups necessitate that clinicians “gain exposure to the etiology, manifestation, and treatment of eating disorders within multiple contexts” (p. 95). This assertion underscores the critical need for a more inclusive and culturally competent approach to assessing, treating, and educating about EDs, emphasizing the urgency of addressing the existing gaps in research. Ultimately, the absence of targeted ED research and training, notably conceptualization and assessment strategies, poses ethical concerns for safeguarding clients’ welfare, rendering trainees ill-equipped to address milder presentations of these disorders, let alone complex cases with more severe symptoms, such as heightened suicidality, enduring medical complications, and acute psychological distress (Kärkkäinen et al., 2018).

Research concerning client experiences is also imperative when assessing education and training needs for effective ED treatment. Babb et al. (2022) conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative research on ED clients’ experiences in ED treatment, illuminating important themes on clinicians’ roles in supporting clients. Several clients reported that some staff perpetuated stereotypes about EDs (e.g., viewing the client as an illness versus a person) and tried to fit clients into specific theoretical frameworks. Clients attributed this lack of awareness and sensitivity to the providers’ lack of specialized training in EDs. Conversely, clients in this study felt empowered when providers were empathic and provided individualized approaches to treatment. These participants noted that “being seen as an individual” facilitated motivation for treatment, with the therapeutic alliance as an essential factor in this process (Babb et al., 2022, p. 1289). These client perspectives provide valuable insights that should inform the development of CE training programs to better prepare CITs for working with individuals with EDs.

Training Recommendations for Counselor Education Programs

Collectively, the findings cited above underscore the importance of comprehensive ED training for counselors to be able to effectively and compassionately serve diverse clients with EDs. However, accessibility to such education and training remains a challenge to both the graduate students and practitioners (Biang et al., 2024; Labarta et al., 2023). Furthermore, despite the efficiency of manualized approaches, Babb et al.’s (2022) study emphasized the need for both flexibility and avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach to ED treatment, particularly given the diversity of clients with EDs, including those from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds (Schaumberg et al., 2017). Clients’ lived experiences corroborate these gaps, reporting instances of stereotyping, rigid adherence to theoretical frameworks, and a lack of empathy stemming from inadequate specialized training (Babb et al., 2022). These findings highlight the pressing need for training strategies that ensure competence and uphold ethical standards within the treatment of EDs, including ongoing education for new practitioners entering the field.

The following section offers competency-based recommendations for CE programs to incorporate into their curricula and experiential training. We propose a conceptual model that we call the 3 Cs of ED Education and Training. The 3 Cs are: (a) cultivating trainee self-awareness, (b) capturing contextual and sociocultural factors, and (c) collaborating with interdisciplinary professionals (see Figure 1). We also provide an overview of recommended activities and associated reflective prompts that can be used in a special topics course on EDs (see Appendix A), as well as suggested adaptations for integration across counseling curricula. By integrating these teaching strategies, CE programs can enhance competency-based education for EDs (Williams & Haverkamp, 2010), which may empower CITs to provide compassionate, empirically supported services to this vulnerable population.

Figure 1

The 3 Cs of ED Education and Training

Cultivating Trainee Self-Awareness

Cultivating trainee self-awareness is essential to ethical and multiculturally competent ED treatment. As espoused in our ethical codes (ACA, 2014), counselors are expected to examine their own beliefs, attitudes, and emotional responses when working with clients. Without such conscious examination, clinicians risk projecting their personal biases onto their clients or responding in ways that might inadvertently cause harm. For instance, the pervasive weight stigma embedded in our society can unconsciously influence counselors and may result in microaggressions, victim blaming, or the dismissal of symptoms, particularly when working with clients in larger bodies (Veillette et al., 2018). Counselors may also experience countertransference reactions triggered by ED behaviors or other challenging treatment components, such as high relapse rates, resistance to treatment, or insurance coverage issues (Labarta et al., 2023; Warren et al., 2013), negatively influencing the therapeutic relationship (Graham et al., 2020). Reflexive exercises, paired with targeted deliberate skill practice, are valuable mechanisms for facilitating conscious self-examination and building relevant knowledge and skills for effective ED treatment.

Encouraging Reflexivity and Deliberate Practice

Reflexivity, defined as “a practice of observing and locating one’s self as a knower within certain cultural and socio-historical contexts,” allows CITs to engage with courses on cognitive, affective, and experiential levels (Sinacore et al., 1999, p. 267). The integration of reflexive exercises and critical discussions into ED curricula is essential for cultivating self-awareness and, in effect, mitigating potential client harm. Such practices create opportunities for trainees to identify and address any unconscious biases or beliefs, which, if unaddressed, can undermine the quality of care provided. By establishing a habit of mindful self-inquiry, educators can take the first critical step in preparing ethically conscientious counselors attuned to ED clients’ diverse needs (Labarta et al., 2023).

This intentional practice of reflexivity should be paired with deliberate practice strategies focused specifically on promoting skill development for treating EDs. Deliberate practice is a systematic and intentional training method that targets skill development in order to attain expert performance in a given area or domain (Ericsson, 2006; Irvine et al., 2021). Research shows that integrating deliberate practice strategies early in CE training promotes competency development (Chow et al., 2015). Ericsson (2006) developed five crucial tasks of deliberate practice: self-assessment, skill repetition, formative feedback, stretch goals, and progress monitoring. The first task is a necessary step in increasing trainee self-awareness, which is particularly crucial when working with vulnerable populations, such as those struggling with EDs. Deliberate practice empowers trainees to refine their skills and continuously evolve as competent, empathic, and effective counselors. Thus, deliberate self-reflection on personal assumptions is key, as examining one’s relationship with food and body is imperative to prevent issues like value imposition and orient the focus of treatment to the client’s healing process.

Integrating reflexivity and deliberate skill practice early in CE training is vital to promoting lasting competency. CITs often overestimate their competence at the end of their training, necessitating that CE programs systematically monitor the congruence between CITs’ self-assessments and counselor educators’ assessments of CITs’ competency and skill development (Gonsalvez et al., 2023). Routine reflexive exercises can illuminate areas for growth, while deliberate practice strategies provide structured mechanisms for targeted skill refinement. As trainees embark on their professional journeys, ongoing and intentional efforts to self-reflect and evolve through skill refinement will empower them to provide safe, ethical, and effective ED treatment.

Capturing Contextual and Sociocultural Factors

It has been well-documented that EDs impact individuals across social and cultural identities despite the misconception that only thin, White, affluent, cisgender women are affected (Schaumberg et al., 2017). Indeed, scholars have pointed to the need for intersectional, social justice–informed research that addresses the unique ways that context and culture influence EDs and body image concerns (Burke et al., 2020; Halbeisen et al., 2022). The prevalence of EDs and pervasive body image issues is alarming in today’s sociocultural landscape. For instance, the recent increase in gender-affirming care bans and anti-LGBTQ+ legislation poses profound and detrimental effects on individuals battling an ED (Arcelus et al., 2017), as these restrictive policies exacerbate the mental and emotional distress already experienced by LGBTQ+ individuals, further isolating them and undermining their access to critical health care services (Canady, 2023). As a result, members of this community are more apt to experience intensified body dysphoria, heightening the risk of developing or worsening an ED in an attempt to conform to societal norms (Arcelus et al., 2017).

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has experienced a collective trauma that triggered a series of physical and mental health consequences that will linger for years to come, including rising rates of disordered eating and body-related concerns. Termorshuizen et al. (2020) surveyed 1,021 individuals across the United States and the Netherlands, revealing that ED diagnoses increased at a rate of roughly 60%, with respondents noting increased binge episodes (30%) and restriction behaviors (62%) during this time. Scholars have also shown the deleterious effects of the pandemic on body image perception. For instance, in one study of 7,878 respondents, 61% of surveyed adults and 66% of surveyed children (17 and under) disclosed frequent negative feelings regarding their body image, with 53% of adults and 58% of children reporting that the pandemic has significantly exacerbated these feelings (House of Commons, 2021). Unfortunately, weight stigma was also pervasive in the media, with concerns regarding quarantine weight gain (e.g., “Quarantine-15”) contributing to eating and body image challenges (Schneider et al., 2023). Amidst the multifaceted challenges presented by recent sociopolitical events and the intersecting struggles faced by diverse individuals with EDs, it is essential that counselors implement culturally responsive approaches to treatment and advocacy efforts.

Centering Culturally Responsive Approaches

Given the diversity of clients who struggle with eating and body image concerns (Schaumberg et al., 2017), CE programs must integrate culturally sensitive theories into the curriculum to ensure that CITs possess the necessary competencies to explore relevant cultural factors and effectively treat diverse clients with EDs (Williams & Haverkamp, 2010). Two theories that fostered the development of the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC; Ratts et al., 2016) are intersectionality theory and relational–cultural theory (Singh et al., 2020). Intersectionality is a framework for comprehensively understanding the interaction of systemic inequalities and oppression that significantly affect marginalized community members (Burke et al., 2020; Crenshaw, 1991). This theoretical paradigm deepens our understanding of factors such as age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, ability status, body size, and gender identity and how these factors influence an individual’s lived experience. Intersectionality is vital for promoting social justice and culturally responsive treatment while also serving as a tool to dismantle oppression and colonizing practices within the profession (Chan et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2020). Intersectionality-informed practice may assist researchers and counselors with considering risk and protective factors for EDs; however, the lack of attention to the intersecting roles and identities of ED clients (e.g., a Catholic, bisexual, Latina) remains a concern, which is crucial for informing culturally competent counseling and training practices (Burke et al., 2020).

Relational–cultural therapy (RCT; Jordan, 2009) is another promising theory that may decolonize dominant counseling approaches (Singh et al., 2020). Due to its emphasis on relational connection, social justice, and empowerment, RCT has been applied to the treatment of EDs (Labarta & Bendit, 2024; Trepal et al., 2015). Infusing RCT into practice may help counselors understand sociocultural influences that maintain ED (e.g., diet culture, weight stigma, acculturation) and perpetuate feelings of disconnection for individuals who do not conform to prevailing body or appearance standards. RCT also aligns well with counseling’s wellness orientation due to its relational and strengths-based focus, emphasizing resilience over pathology in the treatment of ED (Labarta & Bendit, 2024). Counselor educators can expand beyond traditional ED treatment approaches by integrating culturally responsive theories like intersectionality and RCT into course curricula, thus highlighting the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and systemic components that impact clients with EDs.

Collaborating With Interdisciplinary Professionals

The counseling profession has recognized the importance of interdisciplinary practice, encouraging counselors to participate in “decisions that affect the well-being of clients by drawing on the perspectives, values, and experiences of the counseling profession and those of colleagues from other disciplines” (ACA, 2014, Code D.1.c, p. 10). The CACREP Standards (2023) also emphasize the need for counseling students to learn about collaboration, consultation, and community outreach as part of interprofessional teams (Section 3.A.3). Indeed, interdisciplinary collaboration provides an opportunity for individual and systems-level advocacy (Myers et al., 2002). The challenge remains in how counselors can balance establishing a distinct professional identity while simultaneously fostering a sense of community among various helping professions (Klein & Beeson, 2022). Researchers have underscored common experiences of counselors within interdisciplinary teams, including challenges with building legitimacy and credibility, especially among more well-established helping professions such as psychiatry or psychology (Klein & Beeson, 2022; Ng et al., 2023). Given that multidisciplinary collaboration is also crucial to ED treatment (Crone et al., 2023; Williams & Haverkamp, 2010), counselor educators must prepare CITs to effectively work within interdisciplinary treatment teams while utilizing their counseling values and training to best serve their clients and advocate for the inclusion of counselors across ED treatment settings (Labarta et al., 2023).

Strengthening Counselor Professional Identity

Given that EDs are biopsychosocial in nature, effective treatment commonly involves collaboration among various health professions (e.g., medicine, psychiatry, counseling, psychology, dietetics) to ensure holistic, comprehensive client care (Crone et al., 2023). Counselors’ developmental, preventive, and wellness-based perspectives can help provide a strengths-based approach to interdisciplinary collaborations (Labarta et al., 2023). For example, a psychiatrist at a residential facility may focus on assessing a client’s pathology, comorbidity, and changes in symptoms throughout treatment. Although counselors can also focus on assessing client symptoms, their training allows them to provide insight into protective factors that foster client resilience in their recovery process (e.g., social support and cognitive flexibility). Both professionals bring unique expertise, knowledge, and skill sets that provide a distinct conceptualization of the client’s concerns with food or with their body. However, the ultimate goal of the treatment team is to ensure ethical and competent care for the client.

Outside of intensive ED treatment, counselors in school settings and community agencies can offer prevention-based approaches to mitigate risk factors leading to the development of EDs. Prevention-based efforts, such as community programs and workshops, are essential to the field of ED, given the alarmingly low rates of help-seeking in adults with lifetime EDs (34.5% for anorexia nervosa, 62.6% for bulimia nervosa, and 49.0% for binge eating disorder), which are even more pronounced among marginalized communities (Coffino et al., 2019). As such, counselors and other helping professionals can collaborate on ways to increase accessibility to mental health services for underserved groups with increased risk of eating or body image concerns (e.g., LGBTQ+; Nagata et al., 2020). Regardless of the settings within which CITs will work, students can benefit from developing teamwork, leadership, and advocacy skills, as well as a systemic conceptualization of client care (Ng et al., 2023). Ultimately, counselor educators can encourage the exploration of shared goals across helping professions and the utilization of counseling values and training to enhance interdisciplinary work for diverse clients and communities recovering from EDs (Klein & Beeson, 2022; Labarta et al., 2023; Ng et al., 2023).

Implications for Counselor Educators

The 3 Cs for ED Education and Training pose several implications for counselor educators and counseling programs. Although intended for ED treatment, this framework captures essential competencies across counseling specialties, such as counselor self-awareness, cultural and diversity issues, and interdisciplinary practice (CACREP, 2023). As such, integrating these foci into the counseling curriculum can help reinforce competencies regardless of the settings within which students will work. Counselor educators teaching about EDs should also consider ways to incorporate other ED counseling competencies, such as relevant ethical issues, assessment and screening, and evidence-based treatments into coursework (Williams & Haverkamp, 2010). These topics can be integrated into the 3 Cs for ED Education and Training in several ways. For instance, ethical issues and scenarios, such as determining when a client may need a higher level of care, can be presented to students as a standard component of collaborating with interdisciplinary professionals. Counselor educators can also review common ED assessments and encourage students to critically evaluate gaps in the diagnostic process that impact underrepresented populations (e.g., men with EDs), capturing contextual and sociocultural factors and enhancing culturally responsive care (see Appendix B for more examples.)

We also recognize the potential challenges of implementing the 3 Cs of ED Education and Training, as a stand-alone, special topics course on EDs may not be possible for all counseling programs. However, counselor educators can adapt and incorporate the suggested activities in Appendix A into various CACREP core courses to enhance ED education across the curriculum. CE programs can also utilize their Chi Sigma Iota chapters to host events on EDs, such as an interdisciplinary panel discussion followed by a group discussion on professional counseling identity and advocacy (Labarta et al., 2023). Opening these events to the local community could encourage continuing education, collaboration, and advocacy.

Directions for Future Research

Given that the 3 Cs of ED Education and Training is a conceptual framework, there are several directions for future research. Counselor educators and researchers may consider developing a stand-alone course to test the effects of this framework on CITs’ competence in treating EDs. To our knowledge, limited ED competency measures exist, especially for counselors. As such, researchers could explore developing an instrument that measures ED competency areas that include the 3 Cs of ED Education and Training. Such a tool would be helpful for research, clinical, and teaching purposes. An ED competency tool may also enhance CITs’ and counselors’ deliberate practice efforts, promoting quality care for clients across ED treatment settings. Additionally, one theoretical framework educators can modify to help enhance trainees’ clinical competencies in treating EDs is Irvine and colleagues’ (2021) Deliberate Practice Coaching Framework (DPCF), given its structured guidance for skill refinement through individualized coaching and feedback. The development and future testing of an adapted DPCF for EDs may further enhance reflexive and deliberate practice efforts for CITs and counselors working with this population.

Conclusion

In this article, we have proposed our 3 Cs of ED Education and Training to address current gaps in ED education and enhance trainee preparedness across CE programs. Informed by existing literature, this framework incorporates essential elements of comprehensive ED treatment, including counselor self-awareness, cultural and contextual factors, and interdisciplinary practice. The flexibility of this framework allows educators to adapt current curricula to strengthen ED training in CE programs and to meet the needs of their students. Further research that tests a stand-alone course incorporating this framework is needed. The 3 Cs of ED Education and Training offer a path forward in remedying the salient gaps in ED education, ultimately advocating for more compassionate, ethical, and inclusive care across counseling settings.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/ethics/2014-aca-code-of-ethics.pdf?sfvrsn=55ab73d0_1

Arcelus, J., Fernández-Aranda, F., & Bouman, W. P. (2017). Eating disorders and disordered eating in the LGBTQ population. In L. K. Anderson, S. B. Murray, & W. H. Kaye (Eds.), Clinical handbook of complex and atypical eating disorders (pp. 327–343). Oxford University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1093/med-psych/9780190630409.003.0019

Babb, C., Jones, C. R. G., & Fox, J. R. E. (2022). Investigating service users’ perspectives of eating disorder services: A meta-synthesis. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 29(4), 1276–1296. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2723

Biang, A., Merlin-Knoblich, C., & Lim, J. H. (2024). An exploration of counselors of color working in the eating disorder field. Journal of Counseling & Development, 102(4), 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12532

Burke, N. L., Schaefer, L. M., Hazzard, V. M., & Rodgers, R. F. (2020). Where identities converge: The importance of intersectionality in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(10), 1605–1609. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23371

Canady, V. A. (2023). Mounting anti-LGBTQ+ bills impact mental health of youths. Mental Health Weekly, 33(15), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/mhw.33603

Carney, J. M., & Scott, H. L. (2012). Eating issues in schools: Detection, management, and consultation with allied professionals. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(3), 290–297. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00037.x

Chan, C. D., Cor, D. N., & Band, M. P. (2018). Privilege and oppression in counselor education: An intersectionality framework. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 46(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12092

Chow, D. L., Miller, S. D., Seidel, J. A., Kane, R. T., Thornton, J. A., & Andrews, W. P. (2015). The role of deliberate practice in the development of highly effective psychotherapists. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000015

Coffino, J. A., Udo, T., & Grilo, C. M. (2019). Rates of help-seeking in US adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders: Prevalence across diagnoses and differences by sex and ethnicity/race. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(8), 1415–1426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.02.030

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2024-cacrep-standards

Crandall, C. S. (1994). Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(5), 882–894. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.882

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Crone, C., Fochtmann, L. J., Attia, E., Boland, R., Escobar, J., Fornari, V., Golden, N., Guarda, A., Jackson-Triche, M., Manzo, L., Mascolo, M., Pierce, K., Riddle, M., Seritan, A., Uniacke, B., Zucker, N., Yager, J., Craig, T. J., Hong, S.-H., & Medicus, J. (2023). The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 180(2), 167–171. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.23180001

Deloitte Access Economics. (2020, June). Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States [Infographic]. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/striped/report-economic-costs-of-eating-disorders

Ericsson, K. A. (2006). The influence of experience and deliberate practice on the development of superior expert performance. In K. A. Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J. Feltovich, & R. R. Hoffman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (1st ed., pp. 683–704). Cambridge University Press.

Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

Gonsalvez, C. J., Riebel, T., Nolan, L. J., Pohlman, S., & Bartik, W. (2023). Supervisor versus self-assessment of trainee competence: Differences across developmental stages and competency domains. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(12), 2959–2973. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23590

Graham, M. R., Tierney, S., Chisholm, A., & Fox, J. R. E. (2020). The lived experience of working with people with eating disorders: A meta-ethnography. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(3), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23215

Halbeisen, G., Brandt, G., & Paslakis, G. (2022). A plea for diversity in eating disorders research. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 820043. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.820043

House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee. (2021). Changing the perfect picture: An inquiry into body image. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/5357/documents/53751/default

Irvine, T., Fullilove, C., Osman, A., Farmanara, L., & Emelianchik-Key, K. (2021). Enhancing clinical competencies in counselor education: The Deliberate Practice and Coaching Framework. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 14(4). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol14/iss4/5

Jordan, J. V. (2009). Relational–cultural therapy. American Psychological Association.

Kärkkäinen, U., Mustelin, L., Raevuori, A., Kaprio, J., & Keski-Rahkonen, A. (2018). Do disordered eating behaviours have long-term health-related consequences? European Eating Disorders Review, 26(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2568

Kerl-McClain, S. B., Dorn-Medeiros, C. M., & McMurray, K. (2022). Addressing anti-fat bias: A crash course for counselors and counselors-in-training. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 15(4). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol15/iss4/3

Klein, J. L., & Beeson, E. T. (2022). An exploration of clinical mental health counselors’ attitudes toward professional identity and interprofessionalism. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 44(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.44.1.06

Labarta, A. C., & Bendit, A. (2024). Culturally responsive and compassionate eating disorder treatment: Serving marginalized communities with a relational-cultural and self-compassion approach. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 19(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2023.2174629

Labarta, A. C., Irvine, T., & Peluso, P. R. (2023). Exploring clinician attitudes towards treating eating disorders: Bridging counselor training gaps. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 17(1). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol17/iss1/2

Levitt, D. H. (2006). Eating disorders training and counselor preparation: A survey of graduate programs. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 45(1), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2006.tb00008.x

Myers, J. E., Sweeney, T. J., & White, V. E. (2002). Advocacy for counseling and counselors: A professional imperative. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80(4), 394–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00205.x

Nagata, J. M., Ganson, K. T., & Austin, S. B. (2020). Emerging trends in eating disorders among sexual and gender minorities. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(6), 562–567. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000645

Ng, K.-M., Harrichand, J. J. S., Litherland, G., Ewe, E., Kayij-Wint, K. D., Maurya, R., & Schulthes, G. (2023). Interdisciplinary collaboration challenges faced by counselors in places where professional counseling is nascent. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 45(1), 155–169.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-022-09492-y

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Schaumberg, K., Welch, E., Breithaupt, L., Hübel, C., Baker, J. H., Munn-Chernoff, M. A., Yilmaz, Z., Ehrlich, S., Mustelin, L., Ghaderi, A., Hardaway, A. J., Bulik-Sullivan, E. C., Hedman, A. M., Jangmo, A., Nilsson, I. A. K., Wiklund, C., Yao, S., Seidel, M., & Bulik, C. M. (2017). The science behind the Academy for Eating Disorders’ nine truths about eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 25(6), 432–450.

https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2553

Schneider, J., Pegram, G., Gibson, B., Talamonti, D., Tinoco, A., Craddock, N., Matheson, E., & Forshaw, M. (2023). A mixed-studies systematic review of the experiences of body image, disordered eating, and eating disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 56(1), 26–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23706

Sinacore, A. L., Blaisure, K. R., Justin, M., Healy, P., & Brawer, S. (1999). Promoting reflexivity in the classroom. Teaching of Psychology, 26(4), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328023TOP260405

Singh, A. A., Appling, B., & Trepal, H. (2020). Using the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies to decolonize counseling practice: The important roles of theory, power, and action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12321

Streatfeild, J., Hickson, J., Austin, S. B., Hutcheson, R., Kandel, J. S., Lampert, J. G., Myers, E. M., Richmond, T. K., Samnaliev, M., Velasquez, K., Weissman, R. S., & Pezzullo, L. (2021). Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States: Evidence to inform policy action. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(5), 851–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23486

Termorshuizen, J. D., Watson, H. J., Thornton, L. M., Borg, S., Flatt, R. E., MacDermod, C. M., Harper, L. E., van Furth, E. F., Peat, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2020). Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders: A survey of ~1000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(11), 1780–1790. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23353

Thompson-Brenner, H., Satir, D. A., Franko, D. L., & Herzog, D. B. (2012). Clinician reactions to patients with eating disorders: A review of the literature. Psychiatric Services, 63(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100050

Trepal, H., Boie, I., Kress, V., & Hammer, T. (2015). A relational-cultural approach to working with clients with eating disorders. In L. H. Choate (Ed.), Eating disorders and obesity: A counselor’s guide to prevention and treatment (pp. 261–276). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119221708.ch18

Ulfvebrand, S., Birgegård, A., Norring, C., Högdahl, L., & von Hausswolff-Juhlin, Y. (2015). Psychiatric comorbidity in women and men with eating disorders results from a large clinical database. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.008

van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2020). Review of the burden of eating disorders: Mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 33(6), 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000641

Veillette, L. A. S., Serrano, J. M., & Brochu, P. M. (2018). What’s weight got to do with it? Mental health trainees’ perceptions of a client with anorexia nervosa symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2574. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02574

Warren, C. S., Schafer, K. J., Crowley, M. E. J., & Olivardia, R. (2013). Demographic and work-related correlates of job burnout in professional eating disorder treatment providers. Psychotherapy, 50(4), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028783

Williams, M., & Haverkamp, B. E. (2010). Identifying critical competencies for psychotherapeutic practice with eating disordered clients: A Delphi study. Eating Disorders, 18(2), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260903585524

Appendix A

The 3 Cs of ED Education and Training: Suggested Activities and Reflective Prompts

| 3 Cs of ED Education & Training | Suggested

Activities |

Activity Sample

Reflective Prompts |

Adaptations for Integration Across Counseling Curricula |

|

Cultivating Trainee Self-Awareness |

Reflexive Journaling:

Have CITs maintain a journal, reflecting on their experiences (e.g., biases, assumptions, insights, challenges) throughout the course. Instructors can provide suggested weekly prompts based on the content or topic area discussed. Deliberate Practice: During the first week, CITs will read Williams and Haverkamp’s (2010) article on ED counseling competencies. CITs then write a reflection paper identifying 2–3 targeted, actionable areas for development and growth. Revisit these competencies at the end of the course to assess CIT growth and ongoing development areas. |

Reflexive Journaling Prompts:

Reflect on your beliefs, values, and attitudes about counseling ED clients. What would you like to learn? What challenges do you anticipate? How might cultural factors impact how counselors work with ED clients? Consider how your cultural and social identities shape your relationship with food and body image. Complete the Anti-fat Attitudes Questionnaire (Crandall, 1994) and interpret your score. What insights did you gain? Why might self-assessment in this domain be an important tool for counselors? (Kerl-McClain et al., 2022) Deliberate Practice Prompts: Using a Likert scale of 1 (not confident) to 5 (very confident), how confident do you feel to treat clients with EDs? Using a Likert scale of 1 (not prepared) to 5 (very prepared), how prepared do you feel to treat clients with EDs? Identify 2–3 areas of personal or professional development and growth. Identify 2–3 actionable steps for this semester and beyond.

|

Psychopathology and Diagnosis Courses:

Before teaching ED diagnoses, facilitate a brief activity to promote reflexive practice (see suggested prompts). Follow up with a class discussion on CITs’ reflections, reactions, insights, and the possible impact of biases or assumptions on the diagnosis and treatment process for ED clients. Practicum and Internship Courses: CITs working in ED treatment settings can use the deliberate practice prompts to continually assess strengths and growth areas. Encourage CITs to complete the self-assessment on ED knowledge and skills. Based on the identified gaps, campus instructors can invite guest lecturers to discuss topics of interest. |

| 3 Cs of ED Education & Training | Suggested

Activities |

Activity Sample

Reflective Prompts |

Adaptations for Integration Across Counseling Curricula |

|

Capturing Contextual and Sociocultural Factors |

Media Critique:

Have CITs select and analyze a form of media (e.g., movies, TV series, social media). CITs can then consider the messages conveyed about EDs and body image. Class Discussion: Engage in a class discussion on CITs’ observations, noted themes, and implications for counseling practice. Educators may also initiate a discussion on media literacy and how to broach similar discussions with clients and colleagues.

|

Individual Reflection Prompts:

How were EDs and/or body image concerns portrayed explicitly and implicitly? How do sociocultural factors (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, etc.) influence media portrayals and messages about EDs/body image? How might these portrayals or messages influence one’s beliefs about EDs? Class Discussion Prompts: What were the overarching themes or messages across the various media? How can culturally responsive theories (e.g., RCT, intersectionality) inform how we conceptualize the impact of media on EDs and body image concerns? How can counselors work with clients impacted by harmful media ideals? How can counselors advocate for more culturally inclusive and responsible ED portrayals in media? |

Social and Cultural Diversity Course:

Facilitate a discussion on CITs’ observations of ED media portrayals, considering the impact of limited representation on mental health access. Provide a case study of a client with intersecting minoritized identities and encourage CITs to identify culturally responsive treatment approaches and theories that can benefit the client’s recovery. |

| 3 Cs of ED Education & Training | Suggested

Activities |

Activity Sample

Reflective Prompts |

Adaptations for Integration Across Counseling Curricula |

|

Collaborating with Interdisciplinary Professionals |

ED Expert Panel:

Invite professionals across disciplines specializing in treating EDs (e.g., M.D., psychiatrist, psychologist, dietician). Engage the panelists in a discussion on their respective training, roles, responsibilities, and experiences working in interdisciplinary treatment teams. Reserve Q&A time for CITs to share any thoughts, questions, and insights (Labarta et al., 2023).

After the ED expert panel discussion, have CITs write a reflection paper on what they learned from the panelists. CITs can reflect on how counselors contribute to interdisciplinary teams using their developmental, prevention-focused, and wellness-based training. Facilitate a broader discussion with CITs during the subsequent class meeting. |

Expert Panel Discussion Prompts:

Briefly discuss your ED treatment experiences and describe your main roles and responsibilities. Discuss the benefits and challenges of working in interdisciplinary treatment teams. What would you say are the most prevalent issues faced by ED professionals today? What words of wisdom can you share with CITs considering working with ED clients? Professional Identity · What challenges and opportunities do you foresee as a counselor working in an interdisciplinary treatment team? · How can counseling values inform an interdisciplinary perspective on ED treatment? · What personal strengths could you contribute as an interdisciplinary treatment team member? · Reflect on the MJSCC (Ratts et al., 2016), discussing how they can inform a counselor’s work with diverse clients struggling with eating and/or body image concerns. |

Introduction to Mental Health Counseling Course:

If coordinating an ED expert panel is not feasible, consider inviting other professionals across specialty areas (e.g., EDs, addictions, integrated behavioral health) to share their experiences CITs can complete a reflection paper on their insights and reactions to the guest panelists using the professional identity paper prompts as a guide.

|

Appendix B

Educator Checklist for Integrating the 3 Cs of Eating Disorder (ED) Education and Training Into Counselor Education Curricula

| Cultivating Trainee Self-Awareness | |

| Increase trainee awareness by incorporating ED warning signs, risk factors, and conceptualization strategies into assessment and treatment approaches. | |

| Routinely assess student competency on ED-related knowledge and skills, evaluating for any incongruence between the students’ and educators’ scores. Additionally, assess multicultural counseling competencies related to EDs during student evaluations. Provide feedback for growth. | |

| Encourage student attendance at ED-focused workshops, webinars, and conferences to enhance deliberate practice efforts, promoting professional growth and development. | |

| Promote student exploration of their own cultural identities, values, and biases related to appearance, health, and eating behaviors. | |

| Capturing Contextual and Sociocultural Factors | |

| Incorporate diverse ED case examples and vignettes that reflect a range of intersecting cultural identities and experiences. | |

| Provide training on culturally responsive ED treatment approaches like RCT and intersectionality. Be sure to cover strategies for adapting evidence-based ED treatment approaches to be culturally relevant for diverse clients. | |

| Emphasize the importance of cultivating cultural humility and client empowerment, particularly when working with ED clients from diverse or marginalized backgrounds. | |

| Collaborating With Interdisciplinary Professionals | |

| Critically examine course syllabi to identify where ED content and scholarship could be incorporated or expanded (e.g., textbooks, media, articles). Include resources from interdisciplinary helping professionals. | |

| Compile a list of interdisciplinary community referrals and resources to support students working with ED clients. | |

| Provide opportunities (e.g., guest lecture, course assignment) for students to learn from ED experts in various helping disciplines. Encourage students to reflect on ways to utilize their counseling values and training within interdisciplinary treatment collaborations. | |

Note. This checklist is a framework for integrating ED education into CE graduate training. Consider modifying components to align with your specific curriculum, resources, and student population. The goal is to integrate ED education in a way that provides students with foundational knowledge, skills, and practical experience to effectively support clients struggling with EDs and body image issues in their future counseling practice.

Taylor J. Irvine, PhD, NCC, ACS, LMHC, is an assistant professor at Nova Southeastern University. Adriana C. Labarta, PhD, NCC, ACS, LMHC, is an assistant professor at Florida Atlantic University. Correspondence may be addressed to Taylor J. Irvine, Department of Counseling, Nova Southeastern University, 3300 S. University Dr., Maltz Bldg., Rm. 2041, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33328-2004, ti48@nova.edu.