Melanie H. Iarussi, Jessica M. Tyler, Sarah Littlebear, Michelle S. Hinkle

Motivational interviewing (MI), a humanistic counseling style used to help activate clients’ motivation to change, was integrated into a basic counseling skills course. Nineteen graduate-level counseling students completed the Counselor Estimate of Self-Efficacy at the start and conclusion of the course. Significant differences were found between students’ pre/post measures of self-efficacy (t(18) = –7.055, p = .0005). Qualitative data collected concerning students’ experiences learning counseling skills in the context of MI are described by four main themes: (a) valuable and relevant learning experience, (b) more self-assuredness in working with challenging clients, (c) uncertainty in applying technique, and (d) feelings of restriction with MI application. Implications for integrating MI in skills courses and future directions in research are discussed.

Keywords: counseling skills, counseling students, motivational interviewing, self-efficacy, student experiences

Self-efficacy is an important mediator of performance and involves the degree to which people are capable, diligent and committed in their work (Chen, Casper, & Cortina, 2001). Specific to counselor education, there is a supported relationship between counseling self-efficacy and counselor training (Larson et al., 1992; Nilsson & Duan, 2007). Counseling self-efficacy has been shown to play a fundamental role in counselor development and training (Barnes, 2004; Lent et al., 2006), and higher counseling self-efficacy can be related to greater performance due to motivation factors (Bandura, 1986; Greason & Cashwell, 2009). In this study, the authors explored counselor trainees’ counseling self-efficacy before and after the completion of a counseling skills course that integrated MI. This technique was incorporated into the course to increase students’ humanistic people-responsiveness skills and to expose students to a defined evidence-based practice to help increase their counseling self-efficacy. Students’ experiences in this course were also a focus in the current study.

Counseling Self-Efficacy

Counseling self-efficacy can be defined as a counselor’s belief about his or her ability to effectively counsel a client in the near future (Larson, 1998; Larson & Daniels, 1998; Lent et al., 2006). Based on Bandura’s (1997) theory, this confidence is an important factor in the likelihood of counselor trainees applying specific counseling skills. Counseling skills can be defined as the ability of a counselor to demonstrate attending behavior that displays empathy, support, and a unified effort with the client toward a common goal of resolution and movement forward (Ivey, Packard, & Ivey, 2006; Schaefle et al., 2005; Schaefle, Smaby, Packman, & Maddux, 2007). More specifically, counseling attending behavior can be demonstrated through clarifications, encouragement, paraphrasing, reflecting and summarizing of client statements (Easton et al., 2008; Ivey et al., 2006). Self-efficacy theory states that the ability to thrive in the workplace entails not only content knowledge and appropriate application of required skills, but also the worker’s belief that he or she will use the skills successfully (Barnes, 2004; Melchert, Hays, Wiljanen, & Kolocek, 1996; Tang et al., 2004). Counseling self-efficacy theory holds the assumption that self-efficacy is the instrument through which effective practice occurs and perseverance is strengthened for navigating challenging professional scenarios. The theory also contends that self-efficacy enables an environment where counselor trainees are better able to value feedback in their learning processes (Barnes, 2004; Larson, 1998).

Providing opportunities for students to practice, learn and master counseling skills is a powerful way to develop self-efficacy (Greason & Cashwell, 2009). Within pedagogy literature, researchers suggest that counselor competency can be best developed through critical thinking activities such as role-play, modeling, and receiving practice feedback. Such activities build students’ self-efficacy to help them cope with real-work challenges (Daniels & Larson, 2001; Larson et al., 1992; Duys & Hedstrom, 2000; Tang et al., 2004). These purposeful and challenging interventions, which are important for developing counseling self-efficacy, have also been found to be most effective early in skill training (Barnes, 2004; Larson, 1998; Larson et al., 1999). Although new counselors may not feel confident or be fully prepared in their skills, research has found that experience in the field will likely compensate for any earlier deficiencies (Lent et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2004). As such, self-efficacy has been found to be higher among counselors with more education in counseling, more years of experience practicing counseling, and more hours of supervision (Larson et al., 1992).

When pertaining to counselor training, higher self-efficacy has been associated with greater execution of microskills among counselors-in-training who conducted mock sessions (Larson et al., 1992). Counseling self-efficacy includes having confidence in problem-solving and decision-making skills when working with clients (Easton, Martin, & Wilson, 2008). Self-efficacy is positively related to self-esteem, self-perceived planning effectiveness, and outcome expectations (Easton, Martin, & Wilson, 2008; Larson et al., 1992; Schaefle, Smaby, Maddux, & Cates, 2005; Tang et al., 2004), and negatively related to anxiety (Barnes, 2004; Daniels & Larson, 2001; Larson et al., 1992; Lent et al., 2006; Schaefle et al., 2005). Greason and Cashwell (2009) stated that although self-efficacy and competence are not interchangeable, counselors with strong self-efficacy report less anxiety and interpret their professional concerns as “challenging rather than overwhelming or hindering” (p. 3).

The current study assessed students’ counseling self-efficacy before and after completing a basic counseling skills course that integrated MI. Bandura (1984) described self-efficacy as a “generative capability in which multiple subskills must be flexibly orchestrated in dealing with continuously changing realities, often containing ambiguous, unpredictable, and stressful elements” (p. 233). We assert that integrating MI into a basic counseling skills course can provide counselor trainees with this capability as MI is a structured, evidence-based counseling style that requires the practitioner to approach clients in a humanistic people-responsive manner.

Motivational Interviewing

MI is a collaborative, person-centered counseling style intended to elicit and explore clients’ personal motivations to change in an accepting and compassionate environment (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI practice includes an indispensable humanistic “spirit” that contains four components: partnership, acceptance, compassion and evocation (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Within the client-counselor partnership, or collaboration, the counselor is not doing anything “to” the client, but rather is working “with” or “for” the client, and the client is considered the “expert” on his or her own life. Acceptance is an extension of Rogers’s (1957) concept of unconditional positive regard. Expressions of acceptance in MI include supporting client autonomy, expressing accurate empathy, and reflecting client strengths and attributes through genuine affirmations. Compassion emphasizes the primary focus on the client’s welfare. In regard to evocation, the counselor elicits information about the problem from the client’s perspective, as well as information about the client’s goals, values and struggles. Further, the counselor explores the client’s ambivalence about change and evokes the client’s personal motivations to change. By teaching MI in basic skills courses, graduate counseling students learn to base their practice on these humanistic principles, emphasizing the establishment of a working therapeutic relationship based on empathic acceptance.

In addition to a foundational humanistic spirit, the essential skills of MI derive from person-centered counseling. Open questions, reflective statements, summarizations, and statements of affirmation are heavily utilized and emphasized throughout the four phases of MI: engaging, focusing, evoking and planning (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Phase one—engaging—requires the establishment of a therapeutic relationship, which may include diminishing any relationship discord (formerly known as “resistance”) that is initially present. In phase two, the counselor guides the focus of the interaction to whatever change the client may be considering. In phase three, the MI counselor focuses on evocation by eliciting the client’s arguments in favor of change and helping guide the client to further develop these ideas based on the client’s personal beliefs, values and goals. Counselor behaviors such as confrontation, persuasion and coercion are the antithesis to evocation and are not utilized in MI practice. Providing unsolicited advice and attempting to impose change are seen as counterproductive as these behaviors tend to result in discord in the therapeutic relationship and inhibit client change (Madson, Loignon, & Lane, 2009).

Instead, MI focuses on strategic use of evocation and reflective listening to help guide clients to consider change as they come to recognize and resolve inconsistencies between their values or goals and current behaviors (i.e., developing discrepancies; Miller & Rollnick, 2013). In this way, MI is goal-directed as the counselor intentionally moves with the client to explore and resolve client ambivalence that is interfering with change, and ultimately assist the client to enhance his or her personal motivations to implement and sustain positive behavior change. Finally, once a sufficient level of motivation is present, the counselor and client collaboratively develop a plan for change (phase four). Throughout the four phases of MI, counselors retain the humanistic spirit, meet clients where they are in their unique process of change, and respond to the individualized needs and circumstances of the client.

Basis for Integrating Motivational Interviewing into a Skills Course

The usefulness of MI and the diversity of its application informed the decision to incorporate MI into a basic counseling skills course. Adhering to the four phases of MI provides a clear blueprint for counselor trainees to engage clients in the counseling process, establish a working therapeutic relationship, focus on specific client goals, and develop a plan for change. Further, learning MI includes learning basic counseling skills such as open-ended questions, summarizations, reflections, and highlighting client strengths (i.e., affirmations); therefore, integration of MI might help strengthen these basic skills (Young & Hagedorn, 2012). In addition to these essential skills, learning MI also provides students with the opportunity to learn how to manage discord in the counseling relationship and help resolve client ambivalence about change—both common clinical challenges, especially for beginning counselors. We anticipated that these factors would lead to enhanced self-efficacy among counselor trainees.

In addition to providing a clear framework for counselor trainees to follow to begin the counseling process and a defined method that requires the practice of a humanistic spirit and skills, MI is considered an evidence-based practice (EBP) in the treatment of substance use disorders, the area in which it originated. In addition to substance-abuse treatment, MI has demonstrated efficacy across diverse populations, symptoms and behaviors (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010). From hundreds of research studies and several meta-analyses, MI has been found to be efficacious in the areas of chronic mental disorders management, treatment adherence, problem gambling, smoking cessation, generalized anxiety disorder, and co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, as well as various health issues (Barrowclough et al., 2010; Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Cleary, Hunt, Matheson, & Walter, 2009; Hettema et al., 2005; Lundahl et al., 2010; Westra, Arkowitz, & Dozois, 2009). MI also has been applied to adolescent counseling (e.g., Knight et al., 2005; Peterson, Baer, Wells, Ginzler, & Garrett, 2006), group therapy (e.g., Walters, Ogle, & Martin, 2002), and couples therapy (e.g., Burke, Vassilev, Kantchelov, & Zweben, 2002). By training counseling students to use an approach that has demonstrated effectiveness with a broad range of clients and issues, it seems likely that students’ self-efficacy with regard to clients would increase. In addition, counselor training programs are encouraged to expose students to EBPs (e.g., Council for Accredited Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2009).

Increasing Counselor Trainee Self-Efficacy Through MI Training

Learning to effectively implement MI is a complex task that requires specific training. Extensive training that includes practice feedback or coaching has been found to be helpful in establishing and maintaining proficient MI practice (Abramowitz, Flattery, Franses, & Berry, 2010; Doran, Hohman, & Koutsenok, 2011; Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez, & Pirritano, 2004). To our knowledge, in the only study that has explored MI training with counselor trainees, researchers implemented a 4-hour MI training with graduate counseling students who were in practicum, which resulted in enhanced MI skills compared to a control group who did not receive the 4-hour MI training (Young & Hagedorn, 2012). In the current study, first-year counseling graduate students were exposed to MI starting in the fourth week of a 15-week semester course on basic counseling skills.

This study responded to two research questions. The first question asked, “Does an introductory counseling skills course that incorporated MI significantly increase counseling students’ self-efficacy?” Further, it was expected that an increase in self-efficacy would occur at rates comparable to or exceeding other skill training methods (e.g., skilled counselor training model; Urbani et al., 2002). Second, the authors sought to gain an understanding about the students’ experiences of learning counseling skills within the context of MI.

Description of the Course

Course Materials and Assignments

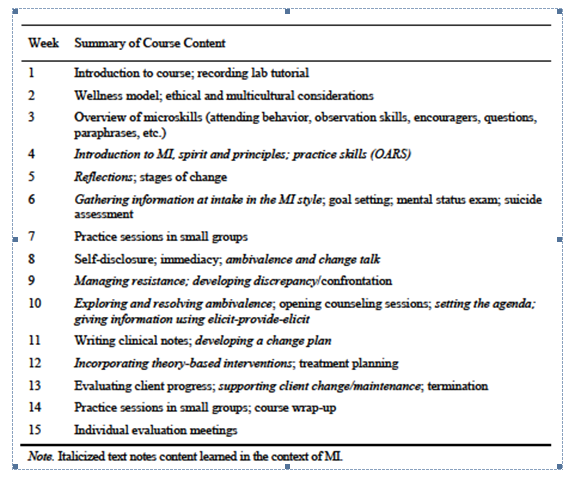

Two textbooks were used in the described course: the first was a general interview and counseling skills text (Ivey, Ivey, & Zalaquett, 2010), which was used exclusively for the first three classes and then intermittently throughout the semester. The second textbook was specific to building MI skills (Rosengren, 2009) and introduced in the fourth class meeting and also incorporated throughout the remainder of the semester. The third edition of the Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (Miller & Rollnick, 2013) text was scheduled to be released shortly after the end of the course. Therefore, students learned the MI concepts as they were presented in the second edition of the text (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) which was a recommended, not required, text for the course. Additional resources were incorporated into the course throughout the semester including supplemental readings related to MI (e.g., Lundahl et al., 2010; Miller & Rollnick, 2004; Miller & Rose, 2009) and video demonstrations of specific MI skills (Miller, Rollnick & Moyers, 1998). The summary of course content provided in Table 1 shows how MI was integrated into the course week-by-week.

Table 1

Integration of MI in Counseling Course

Students were required to complete four video-recorded demonstrations (one 15-minute session, three 45- to 50-minute sessions) of the counseling skills learned in class—with increasing complexity—using role-play with a classmate. Grading rubrics, which were developed by senior faculty and used in this course in previous years and therefore not MI-specific, were used to grade the skill demonstrations. In addition to recorded demonstrations, various written assignments were required throughout the semester, such as reflection papers, a self-evaluation, a completed intake form, a transcribed segment of a recorded mock session, and progress notes.

Course Process

In regard to the process of the course, skill development and practice were emphasized. For each skill presented, a video or interactive demonstration was shown, after which students practiced the skills in dyads or small groups using role-plays. Feedback was provided to the “counselor” from classmates and the instructor and/or a teaching assistant (TA). Three doctoral-level TAs (only one of whom had formal MI training) circulated with the primary instructor (first author) while the students practiced skills in small groups. In the third class meeting, students learned how to give appropriate, constructive feedback to their peers prior to engaging in the first role-play (Ivey, Ivey & Zalaquett, 2010).

Method

A pretest-posttest single group design was employed to investigate the differences in students’ self-efficacy between the start and end of the course, as measured by a self-administered counselor self-efficacy questionnaire. A qualitative case study approach was used to investigate students’ experiences in the course. Qualitative data was collected via an open-ended questionnaire distributed at the final class meeting. All data was collected anonymously and study participation was voluntary.

Participants

This study took place with 19 participants who were graduate students in the counseling programs offered at a large public university in the southern United States. Participants were enrolled in the required Introduction to Counseling Practice course during their second semester of study in their respective counseling programs. Forty-two percent (n = 8) of participants were enrolled in the CACREP-accredited school counseling program, 37% (n = 7) were in the CACREP-accredited clinical mental health counseling program, and 21% (n = 4) were in the APA-accredited counseling psychology program. Twenty-one percent (n = 4) of participants were Black/African American and 79% (n = 15) were White/Caucasian. Sixteen percent (n = 3) of the participants were men and 84% (n = 16) were women. Ages ranged from 22–29 with a mode of 22. All but one of these 19 participants passed this course.

Instruments

The Counselor Estimate of Self-Efficacy (COSE) is a 37-item measure of self-efficacy on a 6-point Likert scale. Sample items include, “When using responses like reflection of feeling, active listening, clarification, probing, I am confident I will be concise and to the point” and “I feel that I have enough fundamental knowledge to do effective counseling.” The COSE has demonstrated reliability and validity as Larson et al., (1992) reported the internal consistency of the COSE was .93 and the test-retest reliability over three weeks was .87. The range for total scores on the COSE is 37–222, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy.

The feedback questionnaire distributed at the end of the course consisted of five questions: (a) How would you describe your overall experience of learning counseling skills in the context of MI?; (b) What, if any, were the benefits of learning counseling skills in the context of MI?; (c) What, if any, were the challenges of learning counseling skills in the context of MI?; (d) Would you recommend that this course follow a similar format (integrating MI into the course) for subsequent cohorts? Why or why not?; and (e) Please provide any other comments/suggestions you may have.

Procedure

This counseling course was a required course that met weekly for 2 hours and 50 minutes over the course of a 15-week semester in the Spring of 2012. The course instructor (first author) was an assistant professor and a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT), meaning she had completed a 3-day training to train others in MI. Three doctoral students assisted with the instruction of the course (one of whom is the third author). These TAs taught segments of the course that were not specific to MI, observed and provided students with feedback during class practice sessions, and provided written feedback on students’ recorded skill demonstrations using a grading rubric that was focused on general counseling skill demonstrations (i.e., not specific to MI).

The second author, who was not part of the course instruction, conducted the informed consent and data collection following protocol approval from the Institutional Review Board. Participants completed a demographic form and a pretest COSE on the first day of class. During the final class meeting (week 14), students completed the posttest COSE and the feedback questionnaire. To reduce coercion and protect participant confidentiality, each participant was issued a code that only he or she knew to match his or her pretest and posttest; students completed the qualitative questionnaire anonymously. The course instructor (first author) was not present during the consenting procedures or data collection, and participants were directed not to provide any identifying information on data collection materials. Finally, participants were informed that their decision to participate in the study, not to participate in the study, or to stop participating would not affect their grade in the course, their relationship with the instructor/researchers, or their future relations with the department or university. No incentives were provided for study participation. Nineteen of the 20 students enrolled in the course completed the study in full. One student was absent during the final class meeting, and therefore did not complete the posttest or the qualitative questionnaire. The pretest from this student was destroyed and not used in data analysis.

Case Study Analysis

A case study design was chosen for qualitative portion of this study in order to explore students’ experiences within a bounded system: the counseling skills course that integrated MI (Creswell, Hanson, Plano, & Morales, 2007). The second and third authors completed the qualitative analysis and aimed to arrive at a description of this specific case using case-based themes (Creswell et al., 2007). To do so, the textual data collected via the feedback questionnaire was typed verbatim by the second author. Then, the second and third authors read over participant responses several times to become familiar with the data. Throughout data analysis, these authors engaged in reflexivity and memo writing with the purpose of reflecting on their personal perspectives and experiences in an effort to see the data as it was and to avoid undue influence from their own histories (Morrow, 2005; Patton, 2002), as well as to record and facilitate analytical thinking (Maxwell, 2005).

Consistent with case study research, the second and third authors independently used categorical aggregation to identify patterns and emergent themes from the data (Creswell, 2007). These authors then came together to reach a consensus about the meaning of the data by discussing their independent categories, referring back to the data, and identifying and agreeing upon preliminary categories. The researchers identified major ideas within the data and identified substantiating evidence across participants’ accounts to support each key issue (Creswell, 2007). Through data analysis, the initial 12 categories (practical skills, beneficial experience, client autonomy, helpful experience, enjoyable experience, effective skills, client resistance, client motivation, adaptable skills, difficult clients, ambivalent clients, and client connection) were collapsed into four information-rich themes, one of which contained two subthemes (Creswell, 2007). The authors repeatedly reverted back to the data when considering the wording of the themes and subthemes to confirm that the titles were consistent with the contents.

A peer reviewer (Creswell et al., 2007; Lincoln & Guba, 1985), who is the fourth author and who was familiar with qualitative research, was employed on two occasions in which the themes and analysis process were examined and questioned in terms of rationale, clarity and holistic understanding of the raw data. After each peer review session, the second and third authors discussed the themes and subthemes and made changes to the organization of the themes and their titles. Final themes were agreed upon by the second and third authors as they reflected the overall meaning of the data. These themes served as naturalistic generalizations or descriptions from which others may learn about this case (Creswell, 2007).

Results

Counseling Students’ Self-Efficacy

Participants’ point increases on the COSE ranged from 0 to 74 with the mode being 19 and the mean 30 points. No student showed a decrease in self-efficacy and one student’s score did not change between the pretest and posttest. After determining the assumption of normality was met using normal Q-Q plots, a dependent t-test was used to determine if significant differences existed between the COSE pretest and posttest for these participants. Results showed that a significant improvement occurred at the .0005 level in which the pretest COSE scores had a mean of 144.79±19.6 and the posttest scores averaged at 174.42 ± 16.0, t(18) = –7.055, p = .0005.

Experiences Learning Counseling Skills Using Motivational Interviewing

The feedback questionnaire elicited participants’ perceived benefits and challenges of learning counseling skills in the context of MI. Overall, participants provided more rich descriptions of positive experiences and benefits rather than negative experiences or challenges. Additionally, each participant responded affirmatively to the fourth question, “Would you recommend that this course follow a similar format (integrating MI into the course) for subsequent cohorts?” In response to the second research question, four main themes were identified to capture participants’ experiences of learning counseling skills within the context of MI. Two subthemes also emerged within the first theme. These themes are presented along with corroborating excerpts from the data.

Learning experience valuable and relevant to skill development. According to a majority of participants in this study, learning counseling skills in the context of MI could translate to their future professional experiences and be relevant in working with clients. Two subthemes emerged from this theme: (a) class instruction was useful and valuable, and (b) students felt they had learned practical and effective skills.

Class instruction useful and valuable. Many students conveyed that class instruction was helpful and they expressed confidence in the expertise of their instructor. One student reflected on the overall experience of learning counseling skills in the context of MI and feeling better prepared following the course: “I see MI being very helpful in my profession and in the overall profession of counseling.” In response to the inquiry about challenges experienced, one student indicated that “the professors did a wonderful job breaking down the beginning and basic steps in order to build on them throughout the semester.”

Participant responses also suggested that students found practicing the skills during class time to be beneficial. One student reflected on the experience of practicing skills: “MI has a ton of great tool[s] that help you connect with your client as you work together to help them change. Practicing the skills in class helped me see how effective they can be in the real world.” When asked about the challenges encountered while learning skills in the context of MI, another student responded: “It is a lot of skills, but practicing them helped me remember and understand them.”

Practical and effective skills learned. Within this subtheme, almost all of the comments from participants suggest that the skills learned were versatile and effective. One student noted the versatile application of MI: “I think the skills can be applied to most any counseling session, regardless of the counselor’s theoretical perspective.” The students also appreciated the demonstrated efficacy of MI, perhaps enhancing their own counseling efficacy. For example, one student wrote, “I feel that learning the skills in the context of MI has enabled me to possess a wide variety of skills and interventions that will work effectively with the client while promoting client autonomy.”

Participants’ beliefs that they would be able to connect with clients also were viewed as a valuable and useful part of this experience. For example, one student reported that “the overall experience of learning MI has given me a new outlook and approach that I can use to connect with and help my clients.” Students also seemed to find the MI approach to be practical, as one student reflected: “All the information that goes with MI seems so practical and almost like common sense.” Another student responded, “I really appreciate the strengths-based approach and the empowerment-stance toward clients. I also like that the skills are specific enough to be practical and general enough to be applicable to a variety of clients.”

More self-assuredness about challenging clients. This theme captured participants’ experiences of an increased sense of self-assurance and comfort when working with clients who are not ready to change (e.g., ambivalent), or who might be considered “difficult” or “hesitant” clients. When describing the benefits of learning counseling skills in the context of MI, almost half the students commented on working with challenging clients with more self-assurance or comfort. For example, one student reflected: “MI allows you to understand that you cannot make someone change and this [rolling] with resistance really helps put the counseling skills to effective use.” Students also expressed they would feel more self-assured working with ambivalent clients in the future. One student noted that “MI has taught me how to work with ambivalence and gave me a whole new set of tools to help initiate change from within the client.” Finally, one student wrote, “I feel I am much more prepared with the skills that will help me when working with hesitant clients.”

Uncertainty in applying technique. Almost half of participants expressed a sense of uncertainty in applying techniques learned throughout the course. This uncertainty appeared to be associated with the technical application of the skills that were taught in conjunction with basic counseling skills. One student reflected on the challenges of learning counseling skills in the context of MI: “Sometimes it was hard to tell the difference between MI techniques and basic counseling techniques. There was a lot of overlap.” Another student responded, “I had trouble implementing the skills learned in class into the video tapes [assignments]. Some of the practice sessions were awkward.” Another student commented on the technicality of skill use: “For me, knowing exactly when to use the skills and how to use them so it’s a natural flow to things.”

Restrictions in applying Motivational Interviewing. Finally, a few students conveyed feelings that the application of MI techniques was somewhat rigid. This rigidity included difficulty in using the techniques in various situations and with a variety of clients as well as combining MI skills with other counseling skills. Although MI was introduced in the counseling skills course to provide a structured approach to practicing basic skills, beginning counseling students typically have had limited exposure to counseling approaches, which may be necessary for students to develop their own counseling style. As one student reflected, “I think it was difficult for me to focus the skills if MI is not being used with a client…kind of rigid in that aspect.” According to another student, “The only suggestion I would make is to incorporate other skills outside of MI.” Finally, one student noted a preference for the skills to be more specific to a school setting: “I would recommend maybe some of the taping sessions to be more school focused.”

Discussion

In the current study, significant differences were found between participants’ counseling self-efficacy pretests and posttests, suggesting that the counseling skills course that incorporated MI was effective in enhancing students’ beliefs that they can be successful counseling clients. The average point increase on the COSE was 30, which is comparable to the findings of Larson and colleagues (1992), who found that counselor trainees’ COSE scores increased approximately one standard deviation over the course of their clinical practicum experience and had an average point increase of 30.4. Similarly, the posttest scores of participants of the current study were comparable to those found by Urbani et al. (2002), who examined the self-efficacy of 53 students who learned counseling skills through the skilled counselor training model (SCTM; 176.46 compared to 174.42 in the current study). These comparable increases in student self-efficacy lend support to incorporating MI into counseling skill courses.

Although there is evidence that participants gained self-efficacy in counseling after learning MI skills in conjunction with basic counseling skills, the qualitative findings suggest that some students were uncertain how to directly apply the MI skills. This self-doubt was particularly expressed when students considered how they might incorporate the skills into sessions with “actual clients” and how to utilize the skills across various theoretical orientations. This concern might not be related to the specific integration of MI skills in a techniques course, but rather a reflection of where students are in their process of becoming a counselor and process of learning. Experiencing discomfort may be developmentally appropriate for beginning counselors and can facilitate growth and learning (Griffith & Frieden, 2000; Kember, 2001).

Rønnestad and Skovholt (2003) described Phase 2: The Beginning Student Phase (of their previously formulated eight stages of counselor development) as a time when students feel easily overwhelmed by new skills and information they are learning, and as a result lack confidence in their abilities. The researchers reported that during this stage, the introduction of basic helping skills that can be used with all clients is helpful in providing students with a sense of control and tranquility. Young and Hagedorn (2012) reported that students who had MI skills training had marked improvements in basic counseling microskills (e.g., empathy, open questions, support, evocation) and noted that this outcome might have been due to the overlap of basic counseling skills used in MI. As MI training reiterates the microskills that many counselor educators expect students to learn, its incorporation into a basic skills course might provide students with the practice and confidence needed to ease the anxiety students may experience in the beginning stages of counselor development.

Incorporating MI into a basic counseling skills course provides students with training in an EBP that possesses a humanistic foundation. Further, it may foster people-responsive counseling skills, such as how to respond to clients who are not ready to change (e.g., ambivalent or mandated clients); students might otherwise receive no or minimal exposure to such skills. Responses in the qualitative portion of this study indicated satisfaction and perhaps relief in learning specific skills that might be useful when working with challenging clients (e.g., reluctant, mandated, difficult). This is especially promising when considering that an obstacle for novice counselors is knowing how to respond to stress-invoking situations when clients show behaviors that seem confusing to counselors (e.g., lack of motivation; Skovholt & Rønnstad, 2003).

In their qualitative research on beginning psychotherapists in a counseling psychology doctoral program, Hill and colleagues (2007) identified that students shared similar frustration when working with clients who were reluctant to participate in the counseling process or who were not open to counselor help. Although other counseling methods might conceptualize and provide ways to work with resistant clients, MI offers a humanistic conceptualization and specific skills for counselors to meet and accept clients where they are in their process of change. Many of MI’s components are specific to working with clients who present in earlier stages of change (i.e., precomtemplation and contemplation), particularly those regarding relationship discord and ambivalence. MI also can be useful as clients prepare for change, take action, and work to maintain changes (DiClemente & Velasquez, 2002). As such, MI skills expand beyond a typical basic skill set and beginning counselors can benefit from having MI as part of their repertoire, especially to help them feel more confident when working with clients who are not ready for change.

Limitations

As with any research investigation, the current study has limitations for consideration. First, the primary instructor of the course also was the primary investigator for the study. This dual role may have influenced students’ responses. Second, this study lacked a control group, which would be necessary to determine between group differences. Third, this study was conducted at one university with a small sample size and is therefore limited in generalizability. Fourth and finally, although a case study design will typically incorporate multiple sources of data (Creswell, 2007), this study relied solely on the feedback questionnaire to gather qualitative data, thus limiting the richness of data collected.

Implications for Counselor Education

Results indicated that using MI skills in an introductory level skills course provided enhanced self-efficacy and positive experiences in learning basic counseling skills. These findings suggest that it might behoove counselor educators to utilize the MI spirit and skills as a way for students to gain a humanistic foundation, reiterate basic counseling skills, and prepare students to help clients who are not yet ready to change. However, it is important for counselor educators who choose to integrate MI into a skills course to be trained and competent in MI skills and application. Additionally, they should be prepared to demonstrate these skills to students.

Students reported higher confidence levels in their readiness to use specific counseling skills; however, they indicated uncertainty in how to integrate these skills with other skills they may have been learning specific to particular theoretical orientations. Since MI is a counseling style and not a theoretical approach, it can be used with other counseling approaches (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy) for a potential synergistic effect (Miller & Rose, 2009). In response to the need for a greater integrative understanding, counselor educators might consider providing additional opportunities for students to discuss and self-reflect on their use of MI skills with their preferred theories, and model ways to synthesize these skills cohesively across theories and various problems presented by clients. Such opportunities would likely occur in advanced coursework including practicum and internship when students are engaging with actual clients. In addition, it may be useful to have more experiential practice in integrating the skills rather than having the sole focus be on using a particular MI skill in isolation.

Overall, incorporating MI into an introductory skills course appeared to be helpful for students. The spirit of MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2013) is undeniably humanistic as it emphasizes self-directed growth and people responsiveness within the therapeutic relationship. Fitch, Canada, and Marshall (2001) reported that humanistic theories (person-centered, existential and Gestalt) are influential in practicum courses, perhaps due to their emphasis on relationship building. When considering MI’s humanistic tenets, it might be useful for counselor educators to consider the utility and worthiness of this approach among other influential and well-established humanistic theories in the field.

Future Directions in Research

Ongoing studies are investigating if these students demonstrated MI proficiency on their final recorded skill demonstration required for this course, and the degree to which students maintained use of MI after they learned and integrated cognitive behavior therapy into their practice. Research that includes a control group is needed in order to assess the effect of learning MI on counselor trainees’ self-efficacy and skill development. Future research also might investigate possible associations between student self-efficacy, satisfaction in a counseling skills course, and execution of skills within and beyond the counseling skills course. In addition, research is needed to inform optimal timing of this type of skill training, as students might be better equipped to incorporate such training later in the graduate programs (e.g., during practicum).

Conclusion

This study investigated students’ counseling self-efficacy before and after completing a counseling skills course that integrated MI. Results indicated that students’ self-efficacy increased at rates comparable to alternative counseling skill development models. Further, students reported positive overall experiences when learning MI skills, which were noted in qualitative themes highlighting their skill development and self-assuredness in working with challenging clients. Students also had some lingering questions about the implementation of MI; however, this might be expected given their early stages of counselor development. Given that student self-efficacy increased by the end of the course and students reported overall positive experiences, this study provides preliminary support of the integration of MI into a counseling skills course. Although further investigations are needed, it seems that the inclusion of MI in the course may be useful to reiterate humanistic counseling skills and prepare students to work with clients who are not yet ready to change and who might otherwise overwhelm a novice counselor.

References

Abramowitz, S., Flattery, D., Franses, K., & Berry, L. (2010). Linking a motivational interviewing curriculum to the chronic care model. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25, 620–626.

Bandura, A. (1984). Recycling misconceptions of perceived self-efficacy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8, 231–255.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy. Harvard Mental Health Letter, 13(9), 4–7.

Barnes, K. (2004). Applying self-efficacy theory to counselor training and supervision: A comparison of two approaches. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 56–69.

Barrowclough, C., Haddock, G., Wykes, T., Beardmore, R., Conrod, P., Craig, T., . . . Tarrier, N. (2010). Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy for people with psychosis and comorbid substance misuse: Randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 341, 6325–6337.

Burke, B. L., Arkowitz, H., & Menchola, M. (2003). The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 843–861.

Burke, B. L., Vassilev, G., Kantchelov, A., & Zweben, A. (2002). Motivational interviewing with couples. In W. R. Miller & S. Rollnick (Eds.), Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed., pp. 347–361). New York, NY: Guilford.

Chen, G., Casper, W. J., & Cortina, J. M. (2001). The roles of self-efficacy and task complexity in the relationships among cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and work-related performance: A meta-analytic examination. Human Performance, 14, 209–230.

Cleary, M., Hunt, G. E., Matheson, S., & Walter, G. (2009). Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance misuse: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 238–258.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP). (2009). 2009 standards. Retrieved from: http://www.cacrep.org

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., Hanson, W. E., Clark, V. L., & Morales, A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 236–264.

Daeppen, J., Fortini, C., Bertholet, N., Bonvin, R., Berney, A., Michaud, P., . . . Gaume, J. (2012). Training medical students to conduct motivational interviewing: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education & Counseling, 87, 313–318.

Daniels, J. A., & Larson, L. M. (2001). The impact of performance feedback on counseling self-efficacy and counselor anxiety. Counselor Education and Supervision, 41, 120–130.

DiClemente, C. C., & Velasquez, M. M. (2002). Motivational interviewing and the stages of change. In W. R. Miller & S. Rollnick (Eds.), Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed., pp. 201–216). New York, NY: Guilford.

Doran, N., Hohman, M., & Koutsenok, I. (2011). Linking basic and advances motivational interviewing training outcomes for juvenile correctional staff in California. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43, 19–26.

Duys, D. & Hedstrom, S. (2000). Basic counselor skills training and counselor cognitive complexity. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40, 8–19.

Easton, C., Martin Jr., W., & Wilson, S. (2008). Emotional intelligence and implications for counseling self-efficacy: Phase II. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 218–232.

Fitch, T. J., Canada, R., & Marshall, J. L. (2001). The exposure of counseling practicum students to humanistic counseling theories: A survey of CACREP programs. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 40, 232–242.

Greason, P., & Cashwell, C. (2009). Mindfulness and counseling self-efficacy: The mediating role of attention and empathy. Counselor Education and Supervision, 49, 2–19.

Griffith, B. A., & Frieden, G. (2000). Facilitating reflective thinking in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40, 82–94.

Hettema, J., Steele, J., & Miller, W. R. (2005). Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 91–111.

Hill, C. E., Sullivan, C., Knox, S., & Schlosser, L. Z. (2007). Becoming psychotherapists: Experiences of novice trainees in a beginning graduate class. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44(4), 434–449. doi 10.1037/0033-3204.44.4.434

Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. P. (2010). Intentional interviewing & counseling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Ivey, A. E., Packard, N. G., & Ivey, M. B. (2006). Basic attending skills (4th ed.). North Amherst, MA: Microtraining Associates.

Kember, D. (2001). Beliefs about knowledge and the process of teaching and learning as a factor in adjusting to study in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 26, 205–221. doi:10.1080/03075070120052116

Knight, J. R., Sherritt, L., Hook, S. V., Gates, E. C., Levy, S., & Chang, G. (2005). Motivational interviewing for adolescent substance use: A pilot study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 167–169. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.020

Larson, L. M. (1998). The SCMCT making it to “the show”: Four criteria to consider. The Counseling Psychologist, 26(2), 324–341. doi:10.1177/0011000098262008

Larson, L. M., Clark, M. P., Wesely, L. H., Koraleski, S. F., Daniels, J. A., & Smith, P. L. (1999). Videos versus role plays to increase counseling self-efficacy in prepractica trainees. Counselor Education and Supervision, 38, 237–248. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.1999.tb00574.x

Larson, L. M., & Daniels, J. A. (1998). Review of the counseling self-efficacy literature. The Counseling Psychologist, 26, 179–218. doi:10.1177/0011000098262001

Larson, L. M., Suzuki, L. A., Gillespie, K. N., Potenza, M. T., Bechtel, M. A., & Toulouse, A. L. (1992). Development and validation of the Counseling Self-Estimate Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 39, 105–120. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.39.1.105

Lent, R. W., Hoffman, M. A., Hill, C. E., Treistman, D., Mount, M., & Singley, D. (2006). Client-specific counselor self-efficacy in novice counselors: Relation to perceptions of session quality. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 453–463. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.453

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Lundahl, B. W., Kunz, C., Brownell, C., Tollefson, D., & Burke, B. L. (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20, 137–160. doi: 10.1177/1049731509347850

Madson, M. B., Loignon, A. C., & Lane, C. (2009). Training in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36, 101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.005

Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Melchert, T. P., Hays, V. L., Wiljanen, L. M., & Kolocek, A. K. (1996). Testing models of counselor development with a measure of counseling self-efficacy. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74, 640–644. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1996.tb02304

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2004). Talking oneself into change: Motivational interviewing, stages of change, and therapeutic process. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 18, 299–308. doi: 10.1891/jcop.18.4.299.64003

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Miller, W. R., Rollnick, S., & Moyers, T. B. (1998). Motivational interviewing: Professional training videotape series [DVD]. Albuquerque, NM: The University of New Mexico.

Miller, W. R., & Rose, G. S. (2009). Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist, 64, 527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830

Miller, W. R., Yahne, C. E., Moyers, T. B., Martinez, J., & Pirritano, M. (2004). A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 72, 1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 250–260. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

Nilsson, J. E. & Duan, C. (2007). Experiences of prejudice, role difficulties, and counseling self-efficacy among U.S. racial and ethnic minority supervisees working with white supervisors. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 35, 219–229. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2007.tb00062.x

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Peterson, P. L., Baer, J. S., Wells, E. A., Ginzler, J. A., & Garrett, S. B. (2006). Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 254–164. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.254

Rogers. C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95–103. doi: 10.1037/h0045357

Rosengren, D. B. (2009). Building motivational interviewing skills: A practitioner workbook. New York, NY: Guilford.

Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovholt, T. M. (2003). The journey of the counselor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives on professional development. Journal of Career Development, 30, 5–44. doi:10.1177/089484530303000102

Schaefle, S., Smaby, M. H., Maddux, C. D., & Cates, J. (2005). Counseling skills attainment, retention, and transfer as measured by the skilled counseling scale. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 280–292. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01756.x

Schaefle, S., Smaby, M. H., Packman, J., & Maddux, C. D. (2007). Performance assessment of counseling skills based on specific theories: Acquisition, retention, and transfer to actual counseling sessions. Education, 128, 262–273.

Skovholt, T. M., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2003). Struggles of the novice counselor and therapist. Journal of Career Development, 30, 45–58. doi:10.1177/089484530303000103

Tang, M., Addison, K. D., LaSure-Bryant, D., Norman, R., O’Connell, W., & Stewart-Sicking, J. (2004). Factors that influence self-efficacy of counseling students: An exploratory study. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 70–80. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01861.x

Urbani, S., Smith, M. R., Maddux, C. D., Smaby, M. H., Torres-Rivera, E., & Crews, J. (2002). Skills-based training and counseling self-efficacy. Counselor Education and Supervision, 42, 92–106. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.2002.tb01802.x

Walters, S. T., Ogle, R., & Martin, J. E. (2002). Perils and possibilities of group-based motivational interviewing. In W. R. Miller & S. Rollnick (Eds.), Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed., pp. 377–390). New York, NY: Guilford.

Westra, H. A., Arkowitz, H., & Dozois, D. J. A. (2009). Adding a motivational interviewing pretreatment to cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.014.

Young, T. L., & Hagedorn, W. B. (2012). The effect of a brief training in motivational interviewing on trainee skill development. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51, 82–97. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00006.x

Melanie H. Iarussi is an Assistant Professor at Auburn University. Jessica M. Tyler, NCC, is Clinical Coordinator at East Alabama Mental Health and Adjunct Professor at Auburn University. Sarah Littlebear, NCC, is a doctoral candidate at Auburn University. Michelle S. Hinkle is an Assistant Professor at William Paterson University. Correspondence can be addressed to Melanie H. Iarussi, Auburn University, 2084 Haley Center, Auburn, AL 36830, miarussi@auburn.edu.