Heather C. Robertson, Pamelia E. Brott

Many military veterans face the challenging transition to civilian employment. Military veteran members of a national program, Troops to Teachers, were surveyed regarding life satisfaction and related internal/external career transition variables. Participants included military veterans who were currently or had previously transitioned to K–12 teaching positions. Two variables, confidence and control, demonstrated a slight yet statistically significant positive correlation with life satisfaction. Recommendations for practice and future research are included in this second report on the findings of a dissertation.

Keywords: career transition, employment, life satisfaction, military veterans, teaching

Military members typically experience transitions at some point during their military career, whether to a new duty station, a change of command or a deployment overseas. Another significant transition that military members often face is their return to civilian employment. While formal military programs are established to provide assistance with planning and overall logistics of such transitions (Wolpert, 2000), research suggests that veterans feel emotionally underprepared to manage the transition to civilian employment (Baruch & Quick, 2009; Business and Professional Women’s [BPW] Foundation, 2007). Researchers have examined retirement satisfaction and adjustment (Spiegel & Shultz, 2003), career adaptability and adjustment (Ebberwin, Krieshok, Ulven, & Prosser, 2004), as well as adjustment after transition (DiRamio, Ackerman, & Mitchell, 2008); however, few studies have examined the overall life satisfaction of veterans experiencing career transitions, specifically examining these experiences. This study examined career transition variables of military members, as well as the relationship of these variables to the military member’s overall life satisfaction.

Schlossberg’s model of “Human Adaptation to Transition” (Goodman, Schlossberg, & Anderson, 2006, p. 33) has made significant contributions to the current understanding of the transition process (Robertson, 2010). While transition is different for each individual, four main areas comprise the model, specifically (1) transition as a process that occurs over a span of time, (2) environmental and individual characteristics that may impact the transition, (3) one’s resources and deficits that impact the transition, and (4) a successful adaptation that is the goal of transition (Robertson, 2010; Schlossberg, 1981). The goal of the transition process is the ability to adapt to the new experience. Individuals manage a multitude of internal influences (e.g., confidence, control, coping skills, motivation) and external influences (e.g., job market, support from family, timing of transition) during the transition process. These influences may be considered resources or deficiencies (Schlossberg, 1981). One of the most important considerations of the model is that transition occurs over time. Schlossberg (2011) states that leaving one role and establishing another takes time, and that the process of doing so is easier for some than for others, even after several years.

Extensive research exists regarding civilians experiencing or considering career transition (e.g., Chae, 2002; Jepsen & Choudhuri, 2001; Perrone & Civiletto, 2004). One impetus for making a career change relates to increasing life satisfaction, which can be defined as contentment or happiness in life (Perrone & Civiletto, 2004). Career counseling models support clients’ movement toward fulfillment, such as the values-based counseling (e.g., Brown, 1995) and constructivist models (e.g., Savickas, 1997), which emphasize value formation, prioritization, role relationships and career adaptability. Given the volatility of the job market, unemployment, underemployment and the uncertainty of the future, one’s control during career transition has become a focus of concern. The support experienced during transition can further impact one’s ability to grow psychologically from the experience (Jepsen & Choudhuri, 2001). The perceived risk of career change also may impact one’s perceptions of control, manifesting as stress, or physical and mental health problems (Strazdins, D’Souza, Lim, Broom, & Rodgers, 2004).

Research does exist on the military career transition experience. Several researchers have examined the importance of pre-retirement/pre-separation planning and its value for post-military employment outcomes (Baruch & Quick, 2007; Baruch & Quick, 2009; Spiegel & Shultz, 2003). Other researchers have examined the relationship between mental health and employment of veterans, specifically regarding issues of trauma, depression and mental health treatment (Burnett-Zeigler et al., 2011; Zivin et al., 2011; Zivin et al., 2012).

Despite previous studies on career transition experiences of civilians and military, there is a dearth of studies that examine the overall experience and life satisfaction of those who transition from the military to a second career. Military members who pursue the teaching profession provide an opportunity to examine life satisfaction and career transition. Their (first) military career indicates a commitment to the military for a period of time. For individuals choosing to teach as a second career path, there also is a commitment toward additional education or certification, since there is no military occupational code (MOC) for educating children in an elementary through high school classroom (Robertson, 2010). While training and leading adults may be required in specific positions, teaching children in a traditional classroom setting is not offered as a military career (Messer, Green, & Holland, 2013). This means that those who pursue teaching would likely have to receive additional education and training in order to teach in a classroom post-military separation. Their commitment to the military and their commitment to teaching indicate that both professions were intentional career opportunities, as opposed to employment obtained via happenstance (Robertson, 2010).

This study explored the transition of 136 military members to the field of teaching. Measurements were sought that would adequately capture the framework of internal and external resources, as well as adaptation and life satisfaction. Given the foci of life satisfaction among military members who are transitioning or have transitioned to teaching, the present study examined the following research question: “To what extent is the life satisfaction of military members who are transitioning or have transitioned to teaching explained by the five career transition factors of readiness, confidence, control, perceived support, and decision independence?”

The career transition variables (readiness, confidence, control, perceived support and decision independence) were hypothesized to increase or decrease in proportion to one’s life satisfaction (Robertson, 2010). This hypothesis was based on earlier research studies examining internal and external variables of career transition, including confidence and self-esteem (Heppner, Fuller, & Multon, 1998; Robbins, 1987), control (Strazdins et al., 2004), readiness and goal setting (Oyserman, Bybee, Terry, & Hart-Johnson, 2004) and family support (Eby & Buch, 1995; Latack & Dozier, 1986). However, while these studies examined career transition, none addressed the transition experiences of military members or their overall life satisfaction.

Methods

Members of a national program, Troops to Teachers (TTT), were surveyed. Ninety (90) mentors (i.e., former military, current teachers who volunteer to assist others with the teaching certification process) and 46 members (i.e., military members who may be seeking or have already secured careers in K–12 teaching) responded to the survey. At the time of the survey, there were 178 mentors on the TTT mentor list, indicating a mentor response rate of approximately 50%. It was not possible to estimate the number of members represented in the database in order to determine a member response rate because the percentages of active and inactive members in the TTT database is unknown. Membership in TTT is not a requirement for pursing a teaching career, and not everyone in the database has continued to pursue teaching since originally joining. Accessing members of TTT was feasible due to contact information made available through the TTT Web site. State TTT directors were contacted and asked to include the survey in their member materials (e.g. Web site, newsletters, e-mails); mentor data was available publically on the TTT Web site. According to Feistritzer (2005) and Robertson (2010), over 8,000 teachers have entered the profession via Troops to Teachers.

Participants

Data from 136 respondents (90 members, 46 mentors) were used for analysis. Specifically, 86% of the respondents were male, 10% female, and approximately 4% identified as transgender or left the item blank. Of the respondents, 87% identified as non-Hispanic; 79% identified as white, and the mean age was 51 (range 21–69 years). Respondents were either married (86%), divorced (4.4%), single (3.7%), or identified as “other” (5.8%). The average household income was $102,224 per year (range $0–$250,000). Distribution of respondents was divided among all branches of service: Air Force (32%), Navy (28%), Army (21%), Marine Corps (13%) and Coast Guard (1%), or the item was left blank (5%). Officers and enlisted personnel were nearly equal, with approximately 48% being officers and 45% enlisted (7% left item blank). Average years served in the military was 20.5 years. Responses indicated that respondents experienced an average of 29.4 months between leaving the military and beginning their teaching career. A large number of respondents (80%) were in the post-transition stage, indicating that they were currently in a teaching or other employment position (Robertson, 2010; Robertson, 2013). Demographic data from the sample was primarily white, male and non-Hispanic, which is similar to that of a larger study of TTT participants (n = 1,461) conducted by Feistritzer (2005).

Instruments

Each participant took the Career Transitions Inventory (CTI) and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), as well as answered 15 demographic questions. The CTI (Heppner, 1991) contains 40 items and assesses strengths and barriers that adults experience during career transition. These items measure one’s belief about readiness (preparedness), confidence (belief in one’s ability manage the process), control (individual input and influence over the process), perceived support (whether important people in one’s life are supportive) and decision independence (impact of decisions on others). Higher scores in one factor indicate that the area is a source of strength for the client. Lower scores may be viewed as barriers or obstacles for clients, excluding the independence factor. The independence factor is not viewed as a strength or barrier; however, independence measures one’s relationship and responsibility to others (Heppner & Hendricks, 1995). Of the 40 items, each variable is assigned a selected number of items as well as an average score from high to low, specifically as follows: control (6 items; high score = 5.0, medium score = 3.5, low score = 2.0), readiness (13 items; high score = 5.5, medium score = 4.7, low score = 2.7), perceived support (5 items; high score = 5.6, medium score = 4.7, low score = 2.6), confidence (11 items; high score = 4.7, medium score = 3.9, low score = 2.2) and decision independence (5 items; high score = 5.0, medium score = 3.5, low score = 2.0). The CTI subscale scores’ reliability ranges from .66–.87 (median .69); the test-retest reliability (three-week interval) for each section is as follows: control .55, readiness .74, perceived support .77, confidence .79, and decision independence .83. The overall CTI test-retest reliability was reported as .84 (Heppner, Multon, & Johnston, 1994). Construct validity has been reported for various populations, as well as convergent validity with external instruments, which was utilized during the development of a French version of the CTI (Fernandez, Fouquereau, & Heppner, 2008).

The SWLS (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) is a five-item instrument assessing life satisfaction, allowing respondents to examine overall satisfaction based on the their own personal values. The instrument contains five statements and responses are indicated on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). These statements include the following: “(a) In most ways my life is close to my ideal; (b) The conditions of my life are excellent; (c) I am satisfied with my life; (d) So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life; and (e) If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing” (Diener et al., 2009. Results are tallied as an overall score, which corresponds to a level of satisfaction, specifically highly satisfied, satisfied, average, below average, dissatisfied and extremely dissatisfied. The reported reliability includes Cronbach’s alphas of .87 for the scale and .82 for test-retest (two-month interval). Validity evidence appears as moderately strong convergence, with outcomes ranging from .50–.75 with 12 other instruments (Diener et al., 1985). More recent reports indicate a number of cross-cultural studies that have utilized the SWLS, including studies with the U.S. Marine Corps (Pavot & Diener, 2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the overall population. Based on the large number of mentors in the group, t-tests were conducted to compare the mentor group to the member group. Correlation was used to examine the primary hypothesis stating that all transition variables would be positively correlated with life satisfaction. Finally, multiple regression analyses examined how the transition variables might explain variability in the military members’ life satisfaction.

Comparing Mentor and Member Groups

Initially there was concern about the large number of mentors among respondents. Because mentors are TTT volunteers who assist members with the teacher certification process, there was concern that mentor experiences would be positively skewed as a result of mentors having positive experiences (e.g. desired employment) with their transitions. Thus t-tests on demographic, career transition and life satisfaction variables were conducted. The demographics of both groups (member and mentor) were analyzed using cross-tabs and graphs as a means of comparing the two samples. The member and mentor samples were comparable. Both groups were comprised of primarily married men (% of men = mentor 87%, member 85%; % married = mentor 86%, member 87%). Their racial and ethnic backgrounds were primarily white and non-Hispanic (% white = mentor 80%, member 76%; % non-Hispanic = mentor 90%, member 80%). The groups were similar in terms of average years served in the military (mentor 21, member 20). There was a slight difference in their ages (mentor 53, member 57), combined income (mentor $98,100, member $114,200) and the length of transition between military and civilian employment (mentor 26 months, member 40 months). Despite the differences in their transition periods, a t-test did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference between the time in transition for members and mentors, t (28) = –.965, p = .343; r = –.12 (mentors: M = 26.22, SD = 33.3; members: M = 39.60, SD = 66.8).

Due to the similarity of the two groups, as well as the small number of respondents in the member group, a decision was made to report the findings as one group (combined member and mentor). T-tests which compared the means of the mentor and member groups with life satisfaction, as well as with the variables of readiness, confidence, control, support and decision independence, found no statistically significant differences among the variables. Specifically, t-tests revealed the following: readiness: t (134) = –.485, p = .626, r = .05 (mentors: M = 2.89, SD = .57; members: M = 2.93, SD = .62); confidence: t = (134) = –806, p = .422, r = –.07 (mentors: M = 4.09, SD = .57; members: M = 4.17, SD = .58); control: t (134) = –.022, p = .983, r = .05 (mentors: M = 4.3, SD = .87; members: M = 4.3, SD = .91); support: t (134) = –1.681, p = .095, r = –.14 (mentors: M = 3.67, SD = .51; members: M = 3.83, SD = .57); decision independence: t (134) = –.540, p = .590, r = .04 (mentors: M = 3.71, SD = .90; members: M = 3.79, SD = .75); and life satisfaction: t (134) = –.221, p = .826, r = –.20 (mentors: M = 5.57, SD = .12; members: M = 5.62, SD = .12) . Therefore, a decision was made not to disaggregate the data into member and mentor groups, since there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups, and smaller group samples would reduce the validity of the findings.

Life Satisfaction and Career Transition

Reliability was reported for each career transition variable using Cronbach’s alpha (life satisfaction = .87, readiness = .87, confidence = .83, control = .69, support = .66, decision independence = .67). All transition variables had positive, statistically significant correlations with one another (ranging from .25 to .56). Results from the SWLS indicated satisfied to average level of satisfaction (M = 5.59; SD = 1.21) for participants.

To address the hypothesis that all transition variables correlated with life satisfaction, bivariate correlation analysis using Pearson’s r was utilized. Using the SWLS and the CTI means for each variable (readiness, confidence, control, support and decision independence), a correlation matrix was developed (Table 1). Two transition variables, confidence (r = .23) and control (r = .31), demonstrated little statistically significant positive correlations to life satisfaction. Thus, the overall hypothesis stating that all variables would be correlated with life satisfaction was not supported.

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations for Life Satisfaction and Career Transition

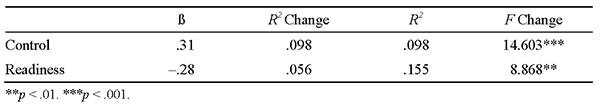

Results from multiple regression analyses were used to address the main research question: To what extent is the life satisfaction of military members who are transitioning or have transitioned to teaching explained by the five career transition factors (readiness, confidence, control, perceived support, and decision independence)? Of the five predictor variables, control was the only transition variable found to explain life satisfaction (Table 2). Control was responsible for 10% of the variance in life satisfaction (F (1, 134) = 14.60, R = .10, beta = .31, p < .001); whereas readiness was responsible for adding approximately 6% (F (3, 133) = 8.87, R = .16, beta = –.28, p < .01). Combined, control and readiness accounted for approximately 16% of the variance in life satisfaction, indicating a small to medium effect size. None of the other variables (confidence, support, decision independence) explained any statistically significant portion of life satisfaction.

Table 2

Multiple Regression with Life Satisfaction and Career Transition Variables

Discussion

Control was the primary variable connected to life satisfaction among transitioning military members, with a small but significant correlation with life satisfaction. Control has been present in several studies which indicate its positive influence on the transition process (Heppner, Cook, Strozier, & Heppner, 1991; Latack & Dozier, 1986; Lerner, Levine, Malspeis, & D’Agostino, 1994; Perosa & Perosa, 1983). While the correlation between control and life satisfaction was significant, one should also note that it was small. As such, control of one’s career transition may not be an essential component of life satisfaction post-transition (Robertson, 2010).

Confidence had a small correlation to life satisfaction, despite the fact that earlier studies cite confidence as an essential element for career transition success (Heppner et al., 1991; Latack & Dozier, 1986). While respondents indicated moderate to high confidence on the CTI, it should be noted that many of those who responded to the survey indicated that they were in the post-transition phase, having already began their teaching career. These respondents would exhibit and respond with great confidence in the success of their transition, with the knowledge that they had already navigated the experience with success (Robertson, 2010).

Readiness contributed slightly to the findings and also is present in earlier research as a as a means of coping with transitions (Ebberwein, Krieshok, Ulven, & Prosser, 2004; Oyserman et al., 2004). The terms ready and motivated are often used to describe U.S. military service members. While readiness and motivation did not present substantial outcomes in this study, it is important to explore the feelings of readiness and motivation in military members making a career transition, particularly those who have less control over their military separation and may not feel ready for the transition.

Implications for Counseling Practice

Counselors should recognize that confidence, control and readiness may play a role in the life satisfaction of current or former military members’ career transition. Counselors may wish to help military clients in transition examine their perceptions of control. A difficult economy and rising joblessness rates may cause clients to feel a lack of control. For military members transitioning to the civilian sector, controlling their own career decisions can be a new and challenging concept. However, counselors can assist clients in examining transition from angles that they can control, including attitude or effort toward the transition or their job search. Counselors may wish to help clients identify areas of control that are present before, during and after the transition. Military members who had no control over their military separation (e.g., being passed over for promotions, injury, medical discharge, other than honorable discharge) can explore with counselors how the circumstances of their separation from the military do not determine their life satisfaction post-transition.

Counselors working with current and former military members should explore the clients’ confidence both toward completing the transition process and their life post-transition. Military communities have a unique military culture, and separation from one’s military culture may impose a lifestyle loss (Simmelink, 2004), which may be more difficult than moving from civilian job to civilian job. Regardless of how or where a military member spent their career (e.g. abroad, state-side, combat, or non-combat), they may go through a period of culture shock in their post-military career (Wolpert, 2000; Robertson, 2010). The military member’s confidence may contribute to their ability to manage that change and loss. Counselors also may wish to address confidence of the military member before, during and after the transition process. Specifically, counseling activities that both assess and enhance confidence may help clients obtain greater life satisfaction in their post-military career. Confidence may be viewed as emotional readiness to navigate the career transition process.

Counselors can help clients assess their readiness for the military-to-civilian career transition, including both emotional and practical preparation. Emotional preparation may include preparing for lifestyle loss (Simmelink, 2004), specifically the transition from close-knit military communities, structured employment environments and regular promotions/pay increases to the ambiguous and uncertain realm of civilian employment. Earlier studies on career transition for civilians (Latack & Dozier, 1986) emphasize the presence of grief and loss in career changers. These feelings of loss and longing were also present with this population (Robertson & Brott, 2013), in that service members often feel that their civilian careers are less meaningful, less significant, or less important than their military careers (Spiegel & Shultz, 2003). Counselors must help prepare military members for these emotional aspects of the military-to-civilian transition, as well as the logistical aspects, such as preretirement planning, job searching, benefits, and relocation.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this research was the large number of individuals in the post-transition stage, which impacts the ability to generalize results to all military personnel. Generalizations should not be made to populations with low representation in this sample, which includes females, minorities and the unmarried. Generalizations also should not be made to different occupations (e.g. individuals moving from non-military careers and to non-teaching careers). Respondents for this research were volunteer participants, as opposed to randomly selected. Outcomes were self-reported, which includes the risk that responses may be impacted by other, unintended factors. This is particularly relevant since some respondents were asked to reflect on their past transition experience as opposed to those who were currently undergoing transition (Robertson, 2010).

Challenges with Post-Transition Respondents

The research design was intended to capture respondents in the pre-, mid- and post-transition phases. However, since the CTI is designed for veterans who are currently experiencing transition, instructions were adjusted to ask post-transition respondents to reflect on their transition process and respond as they remembered their transition experience. While these changes raise questions as to the validity of including the post-transition participant responses, three factors support reporting the findings.

First, transition is viewed as a process that occurs over time, not as an event that ends when one becomes employed. Schlossberg (2011) considers it important to identify where one is in the transition process including before, during and after the transition. While individuals may have already secured a teaching job, it does not necessarily imply that they have successfully adapted to the transition. Secondly, when validating the French version of the CTI, Fernandez et al. (2008) utilized a sample of over 1,000 participants who were experiencing varying types of career transition. Heppner herself (1998) identified three types of career transition: task change, position change and occupational change. Task changes and position changes usually occur within the same workplace settings, while occupational changes involve an entirely new occupation. These variations on transition were incorporated in the results of the CTI. Heppner’s (1998) own validation of the CTI included stages of transition. This factor emphasizes the variability in which transition occurs as reported by participants, and this variability has been incorporated into the development of the CTI.

Finally, the findings of this research, originally from a dissertation, support and supplement earlier studies regarding midlife career transition, life satisfaction and transition variables. For example, Baruch and Quick’s (2009) study of senior admirals who had left the Navy addressed the difficulty of the transition and adaptability. They specifically addressed the admirals’ ability to move away from past roles and toward future roles, reinforcing the concept of transition over time. Spiegel and Shultz (2003) also examined a variety of transition variables in their study of retired naval officers. A pilot project by the BPW Foundation (2007) examined female veterans transitioning to civilian employment and emphasized the importance of both practical and psychological supports during and after the transition. These studies demonstrate that the variables examined by the CTI are being examined in other military transition research.

It was predicted that distribution among respondents’ participant groups (pre-, mid-, and post-transition) would be somewhat balanced; however, the results were not as anticipated. Yet the findings yield valuable results in understanding veterans and the career transition process. T-tests also yielded no significant differences between mentors (primarily post-transition) and members (pre-, mid- and post-transition).

Future Research Opportunities

Future research opportunities exist to replicate the present research with populations that exhibit greater diversity, including veterans in various stages of transition and veterans from various demographic backgrounds. A random sample survey would provide results that are less likely to be influenced by personal factors. Longitudinal studies, following service members from their time in the military, through their transition, to their post-service employment, perhaps via interviewing and qualitative research, would provide personal experiences and insights on service members’ transitions. Opportunities exist to diversify the careers being studied (Robertson, 2010). For example, many universities offer “career changer” programs for individuals transitioning to teaching, who are not necessarily military members. Another option would be to utilize post-service military organizations (e.g., U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans of Foreign Wars, or Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America) to examine the transition experience of military members to other careers besides teaching. University career centers may have access to data examining student veteran career transition information. Further, life satisfaction scores could be compared to other populations beyond those studied here, thus illuminating whether these results were a condition of military experience, teaching careers, or other factors pertaining to the career transition experience.

Summary

This research provides insight into life satisfaction and career transition, specifically for military members pursing teaching careers. Military members indicated that their control and confidence throughout the transition process was slightly correlated with life satisfaction. Results indicated that their control and readiness during the transition process may explain a small portion of their life satisfaction. However, previous literature indicates that relationships exist (Robertson, 2010), which were not found in the present study. For example, previous researchers have indicated that family support impacts the career transition process (Perone & Civiletto, 2004; Eby & Buch, 1995); however, family support was not one of the variables considered in this study. One reason for these differences may be the limited sample size and distribution; yet it is also possible that military experiences are not well examined through traditional assessments. The main limitation of the study was an uneven distribution of the data, including a large number from those post-transition, males, whites and those who were married. Generalizing results to other areas and populations should be discouraged (Robertson, 2010). Counselors who have the opportunity to work with military members transitioning to the civilian workforce, or those who have already transitioned, may wish to address how confidence, control and readiness contribute to the life satisfaction of the transitioning military member.

References

Baruch, Y., & Quick, J. C. (2007). Understanding second careers: Lessons from a study of U.S. Navy admirals. Human Resource Management, 46, 471–491. doi:10.1002/hrm.20178

Baruch, Y., & Quick, J. C. (2009). Setting sail in a new direction: Career transitions of US Navy admirals to the civilian sector. Personnel Review, 38, 270–285. doi:10.1108/00483480910943331

Brown, D. (1995). A values-based approach to facilitating career transitions. The Career Development Quarterly, 44, 4–11.

Burnett-Zeigler, I., Valenstein, M., Ilgen, M., Blow, A. J., Gorman, L. A., & Zivin, K. (2011). Civilian employment among recently returning Afghanistan and Iraq National Guard veterans. Military Medicine, 176, 639–646.

Business and Professional Women’s Foundation. (2007). Women veterans in transition: A research project of the Business and Professional Women’s Foundation. Retrieved from http://bpwfoundation.org/resources/women_veterans_project/

Chae, M. H. (2002). Counseling reentry women: An overview. Journal of Employment Counseling, 39, 146–152. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2002.tb00846.x

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. L., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (2009). Satisfaction with Life Scale: SWLS translations. Retrieved from http://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~ediener/SWLS.html

DiRamio, D., Ackerman, R., & Mitchell, R. L. (2008). From combat to campus: Voices of student-veterans. NASPA Journal, 45, 73–102.

Ebberwin, C. A., Krieshok, T. S., Ulven, J. C., & Prosser, E. C. (2004). Voices in transition: Lessons on career adaptability. The Career Development Quarterly, 52, 292–308. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2004.tb00947.x

Eby, L. T., & Buch, K. (1995). Job loss as career growth: Responses to involuntary career transitions. The Career Development Quarterly, 44, 26–42.

Feistritzer, C. E. (2005). Profile of Troops to Teachers. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Information. Retrieved from http://ncei.com/NCEI_TT_v3.pdf

Fernandez, A., Fouquereau, E., & Heppner, M. J. (2008). The Career Transitions Inventory: A psychometric evaluation of a French version (CTI-F). Journal of Career Assessment, 16, 384–398. doi:10.1177/1069072708317384

Goodman, J., Schlossberg, N. K., & Anderson, M. L. (2006). Counseling adults in transition: Linking practice with theory (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

Heppner, M. J. (1991). The Career Transitions Inventory. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri.

Heppner, M. J. (1998). The career transition inventory: Measuring internal resources in adulthood. Journal of Career Assessment, 6, 135–145. doi:10.1177/106907279800600202

Heppner, M. J., Fuller, B. E., & Multon, K. D. (1998). Adults in involuntary career transition: An analysis of the relationship between the psychological and career domains. Journal of Career Assessment, 6, 329–346. doi:10.1177/106907279800600304

Heppner, M. J., & Hendricks, F. (1995). A process and outcome study examining career indecision and indecisiveness. Journal of Counseling and Development, 73, 426–437.

Heppner, M. J., Multon, K. D., & Johnston, J. A. (1994). Assessing psychological resources during career change: Development of the Career Transitions Inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 55–74. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1994.1004

Heppner, P. P., Cook, S. W., Strozier, A. L., & Heppner, M. J. (1991). An investigation of coping styles and gender differences with farmers in career transition. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 167–174. doi:10.1037//0022-0167.38.2.167

Jepsen, D. A., & Choudhuri, E. (2001). Stability and change in 25-year occupational career patterns. The Career Development Quarterly, 50, 3–19. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2001.tb00884.x

Latack, J. C., & Dozier, J. B. (1986). After the ax falls: Job loss as career transition. Academy of Management Review, 11, 375–392. doi:10.5465/AMR.1986.4283254

Lerner, D. J., Levine, S., Malspeis, S., & D’Agostino, R. B. (1994). Job strain and health-related quality of life in a national sample. American Journal of Public Health, 84, 1580–1585. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.10.1580

Messer, M. A., Greene, J. A., & Holland, J. L. (2013). The Veterans and Military Occupations Finder: Online edition. Lutz, FL: PAR. Retrieved from http://www.self-directed-search.com/docs/default-source/default-document-library/sds_vmof_online_edition.pdf?sfvrsn=2

Oyserman, D., Bybee, D., Terry, K., & Hart-Johnson, T. (2004). Possible selves as roadmaps. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 130–149. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00057-6

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction with Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152. doi:10.1080/17439760701756946

Perosa, S. L., & Perosa, L. M. (1983). The midcareer crisis: A description of the psychological dynamics of transition and adaptation. Vocational Guidance Quarterly, 32, 69–79.

Perrone, K. M., & Civiletto, C. L. (2004). The impact of life role salience on life satisfaction. Journal of Employment Counseling, 41, 105–116. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2004.tb00884.x

Robertson, H. C. (2010). Life satisfaction among midlife career changers: A study of military members transitioning to

teaching (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-05122010-100341/unrestricted/Robertson_HC_D_2010.pdf

Robertson, H. C. (2013). Income and support during transition from a military to civilian career. Journal of Employment Counseling, 50, 26–33. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2013.00022.x

Robertson, H. C., & Brott, P. E. (2013). Male veterans’ perceptions of midlife career transition and life satisfaction: A study of military men transitioning to the teaching profession. Adultspan Journal, 12, 66–79. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0029.2013.00016.x

Robbins, S. B. (1987). Predicting change in career indecision from a self-psychology perspective. The Career Development Quarterly, 35, 288–296.

Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. The Career Development Quarterly, 45, 247–259. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x

Schlossberg, N. K. (1981). A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. The Counseling Psychologist, 9(2), 2–18. doi:10.1177/001100008100900202

Schlossberg, N. K. (2011). The challenge of change: The transition model and its applications. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48, 159–162. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb01102.x

Simmelink, M. N. (2004, December 1). Lifestyle loss: An emerging career transition issue. Career Convergence Magazine.

Retrieved from http://ncda.org/aws/NCDA/pt/sd/news_article/4992/_PARENT/layout_details_cc/false

Spiegel, P. E., & Shultz, K. S. (2003). The influence of preretirement planning and transferability of skills on naval officers’ retirement satisfaction and adjustment. Military Psychology, 15, 285–307. doi:10.1207/S15327876MP1504_3

Strazdins, L., D’Souza, R. M., Lim, L. L.-Y., Broom, D. H., & Rodgers, B. (2004). Job strain, job insecurity, and health: Rethinking the relationship. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9(4), 296–305. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.9.4.296

Wolpert, D. S. (2000). Military retirement and the transition to civilian life. In J. A. Martin, L. N. Rosen, & L. R. Sparacino (Eds.), The military family: A practice guide for human service providers (pp. 103–119). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Zivin, K., Bohnert, A. S. B., Mezuk, B., Ilgen, M. A., Welsh, D., Ratliff, S.,…Kilbourne, A. M. (2011). Employment status of patients in the VA health system: Implications for mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 62, 35–38. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.62.1.35

Zivin, K., Campbell, D. G., Lanto, A. B., Chaney, E. F., Bolkan, C., Bonner, L. M.,…Rubenstein, L. V. (2012). Relationships between mood and employment over time among depressed VA primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34, 468–477. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.05.008

Heather C. Robertson, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at St. John’s University. Pamelia E. Brott, NCC, is an Associate Professor at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Heather C. Robertson, 80-00 Utopia Parkway, Sullivan Hall, Jamaica, NY 11439, robertsh@stjohns.edu.