Sep 4, 2014 | Author Videos, Volume 1 - Issue 2

Robert C. Reardon, Sara C. Bertoch

Educational counseling has declined as a counseling specialization in the United States, although the need for this intervention persists and is being met by other providers. This article illustrates how career theories such as Holland’s RIASEC theory can inform a revitalized educational counseling practice in secondary and postsecondary settings. The theory suggests that six personality types—Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional—have varying relationships with one another and that they can be associated to the same six environmental areas to assess educational and vocational adjustment. Although educational counseling can be viewed as distinctive from mental health counseling and/or career counseling, modern career theories can inform the practice of educational counseling for the benefit of students and schools.

Keywords: educational counseling, career theory, Holland, secondary education, postsecondary education

In searching for a formal definition of educational counseling, we found only one in the APA Dictionary of Psychology (VandenBos, 2007):

The counseling specialty concerned with providing advice and assistance to students in the development of their educational plans, choice of appropriate courses, and choice of college or technical school. Counseling may also be applied to improve study skills or provide assistance with school-related problems that interfere with performance, for example, learning disabilities. Educational counseling is closely associated with vocational counseling because of the relationship between educational training and occupational choice. (p. 314)

The Counseling Dictionary (Gladding, 2006) does not mention the term “educational counseling” in the following definition of counseling.

The application of mental health, psychological or human development principles, through cognitive, affective, behavioral or systemic interventions, strategies that address wellness, personal growth, or career development, as well as pathology. (Gladding, 2006, p. 37)

A renewed focus on educational counseling may be underway. The American Counseling Association meeting in Pittsburgh in 2010 brought together delegates from 29 major counseling organizations who agreed for the first time on a common definition of counseling. Educational goals were explicitly included in this definition: “Counseling is a professional relationship that empowers diverse individuals, families and groups to accomplish mental health, wellness, education, and career goals” (Breaking News, May 7, 2010).

The purpose of this article is to describe five functions essential for educational counseling (Hutson, 1958) and to use them to illustrate how Holland’s RIASEC theory might inform this counseling practice: (a) choosing a college or school for postsecondary training, (b) selecting an academic program or major, (c) adjusting to the college or academic program, (d) assessing academic performance, and (e) connecting education, career, and life decisions.

Historical Perspective

In tracing what has happened to educational counseling, a brief historical review can be helpful. In the early days of the vocational guidance movement, Brewer (1932) shifted the focus of guidance from vocation and occupation to education and instruction. He went so far as to institutionalize guidance as a professional field by linking the terms education and guidance and even using them synonymously. This could have elevated educational counseling to a more prominent position in the profession, but that did not happen. Brewer and others viewed guidance as limited by the descriptive adjective “vocational” with an emphasis on occupational choice (Shertzer & Stone, 1976), and this resulted in an estrangement between vocational and educational counseling.

Shertzer and Stone (1976) reported that the term “educational guidance” was first used in a doctoral dissertation by Truman L. Kelley at Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1914, and that he used it to describe the help given to students who had questions about choice of studies and school adjustment. Stephens (1970) pointed out that the shift from vocational choice to “guidance as education” ruptured the basic nature of the vocational guidance movement, separating the focus on “vocation” to “education.” Thus, vocational theory became associated with occupational choice and only tangentially related to educational choice, and we view this as leading to the separation of educational guidance and counseling from career theory.

In a comprehensive review of educational guidance literature published from 1933–1956, Hutson (1958) saw the counseling element of the educational guidance program as its most important function. He devoted a chapter to “Counseling for Some Common Problems” in which he identified 10 discrete but overlapping counseling situations. Several elements focused on educational counseling, including choice of subjects and curriculums, college-going (choice of going to college or working; choice of a particular college), and length of stay in school. Each of these problem areas involved counseling related to student psychological and educational characteristics, goals, and decision-making skills. Of relevance to this article, Hutson identified no theory related to educational counseling and cited only the vocational theory of Eli Ginzberg (Ginzberg, Ginsburg, Axelrad, & Herma, 1946) as informing vocational counseling. Theory-based educational counseling had not yet arrived.

The practice of educational counseling has faded from view in contemporary guidance and counseling literature. We conducted a search of journal titles and abstracts within the social sciences area using the term “educational counseling” and our university’s online library database system using Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSA) and PsychInfo. We were interested in how many “hits” for the past 10 years we would find in the following journals: Career Development Quarterly, Journal of Career Assessment, Journal of College Counseling, Journal of College Student Development, Journal of Counseling & Development, and Journal of Counseling Psychology. The search provided a total of seven results with only four falling into one of these six journals.

Advising, Coaching, Brokering

While the field of educational counseling seems to have been in decline for the past 50 years, other specialties have emerged to take its place, including academic advising, academic coaching, and educational brokering.

The field of academic advising has been very active in the past 30 years. Ender, Winston, and Miller (1984) defined developmental academic advising as “a systematic process based on a close student-advisor relationship intended to aid students in achieving educational, career, and personal goals through the utilization of the full range of institutional and community resources” (p. 19). Later, Creamer (2000) defined it as “an educational activity that depends on valid explanations of complex student behaviors and institutional conditions to assist college students in making and executing educational and life plans” (p. 18). While generally careful to distinguish between the terms advising and counseling, the National Academic Advising Association (NACADA; http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/index.htm) has fully embraced most of the educational planning and adjustment issues faced by postsecondary students that heretofore might have been included in the domain of educational counseling.

It is beyond the scope of this article to fully explore the notion of academic coaching, so we will limit our comments to the general field of life and career coaching (Chung & Gfroerer, 2003; Patterson, 2008). In general, proponents view coaching as a service focused on a student’s future goals and the creation of a new life path based on less formal collegial mentoring relationships and a positive, preventive wellness model. Opponents view coaching as practicing counseling without proper training or certification because there are limited professional standards or requirements in the coaching field.

Finally, the educational brokering movement in the 1970s was focused on helping adult learners navigate their way through postsecondary educational experiences (Heffernan, 1981). The educational broker independently assisted learners in the process of exploring, researching, and deciding on educational alternatives available. Some educational brokering proponents (Heffernan, 1981) held the view that an educational counselor employed by a specific institution would be biased and “guide” prospective students into the academic programs offered by the employing organization. Brokers were seen as neutral guides to the full range of educational options available to postsecondary learners.

Modern Career Theories

In this article, we examine the topic of educational counseling and suggest that modern career theories could contribute to a revitalization of this function. These theories, identified and described by Brown (2002), include career contextualist theory (Young, Valach, & Collin, 2002); Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription, compromise, and self-creation (L. Gottfredson, (2002); cognitive information processing theory (Sampson, Reardon, Peterson & Lenz, 2004); life stage/life space theory (Super, Savickas, & Super, 1996); narrative construction theory (Savickas, 2002); person-environment correspondence theory (Dawis, 2002); RIASEC theory (Holland, 1997); and social cognitive career theory (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 2002). We illustrate our idea of how career theory might be useful in educational guidance and counseling programs using Holland’s (1997) RIASEC theory, emphasizing the environmental aspect of the theory.

Thus far, we have identified the function of educational counseling as an early component of the developing field of guidance and counseling, and we have outlined trends that have negated that function more recently. The irony is that the need for educational counseling services remains strong today, but it needs revitalization. We believe that the application of new theory, especially career theory, would be useful in that process and inform practice and research in the field. In this article, we focus on Holland’s RIASEC theory as one theory for accomplishing this revitalization. At the same time, we draw upon some of the basic functions of educational counseling drawn from the literature (Hutson, 1958; VandenBos, 2007).

Holland’s RIASEC Theory

Holland’s theory and the related tools such as the Self-Directed Search (SDS; Holland, 1994) have become familiar icons in the career counseling field. Since the introduction of the SDS in 1972 and its use with over 29 million people worldwide (Psychological Assessment Resources, 2009), its incorporation into the Strong Interest Inventory (Harmon, Hansen, Borgen, & Hammer, 1994) and many other tools, we believe that most counselors feel comfortable and knowledgeable about this system. However, we also believe that the widespread familiarity with the hexagon and SDS is based on incomplete and outdated understandings of Holland’s contributions. For many, the theory is viewed as a simple matching model of three personality types, e.g., the three-letter SDS summary code, and the codes of occupations taken from some source, e.g., O*Net (http://online.onetcenter.org/), Occupations Finder (Holland, 2000).

One reason for the partial understanding of Holland’s theory and applications may be the result of the massive volume of research and literature that has been produced since 1957. Authors (2008) reported 1,609 reference citations from 1953–2007 in 197 different journals which make it extremely difficult to fully understand and utilize this body of work. Moreover, many articles have appeared in education journals not often read by counselors, e.g., Journal of Higher Education, Research in Higher Education, Higher Education, and the Review of Higher Education. It is no small irony that Holland’s early work was undertaken in educational settings examining students undecided about their major, adjustment to college, the nature of academic environments, and the work of the faculty within disciplines. Smart, Feldman, and Ethington (2000) recognized this gap in applying Holland’s work to higher education, and their research collaborators have published over 20 articles seeking to address it.

This article focuses on how college students struggle with varied educational decisions, e.g., undecided about their college major, and then examines the ways in which Holland’s RIASEC theory might be used in educational interventions. We begin with a review of Holland’s theory with respect to personality and environment, and then describe several practical tools based on the theory that might be used in educational counseling.

Personality

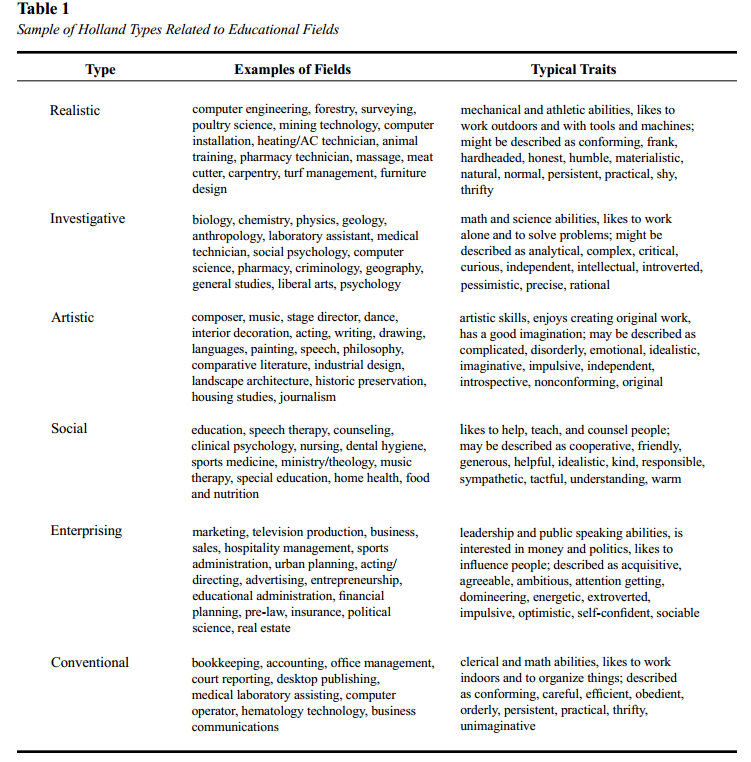

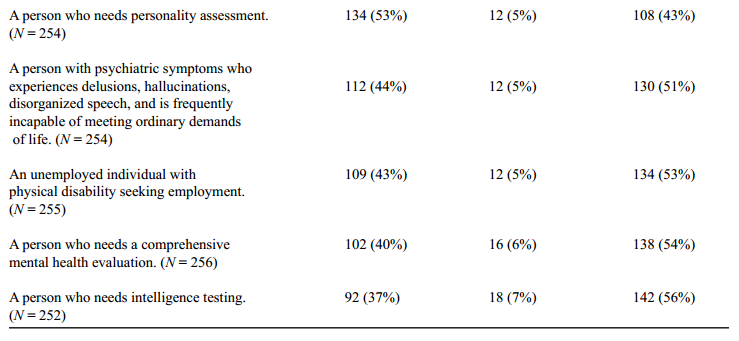

Holland’s typological theory (Holland, 1997) specifies a theoretical connection between personality and environment that makes it possible to use the same RIASEC classification system for both. Many inventories and career assessment tools use the typology to enable individuals to categorize their interests and personal characteristics in terms of combinations of the six types: Realistic (R), Investigative (I), Artistic (A), Social (S), Enterprising (E), or Conventional (C). These six types are briefly defined in relation to educational options in Table 1.

According to RIASEC theory, if a person and an environment have the same or similar codes, e.g., an Investigative person in an Investigative environment, then the person will likely be satisfied and persist in that environment (Holland, 1997). This satisfaction will result from individuals being able to express their personality in an environment that is supportive and includes other persons who have the same or similar personality traits. It should be noted that neither people nor environments are exclusively one type, but rather combinations of all six types. Their dominant type is an approximation of an ideal, modal type.

The profile of the six types can be described in terms of a number of secondary constructs, e.g., the degree of differentiation (flat or uneven profile), consistency (level of similarity of interests or characteristics on the RIASEC hexagon for the first two letters of a three-letter Holland code), or identity (stability characteristics of the type). Each of these factors moderates predictions about the behavior related to the congruence level between a person and an environment. These secondary constructs provide an in-depth schema for understanding a person’s SDS results with diagnostic implications regarding the amount of counselor involvement and skill that may be needed for an intervention (Reardon & Lenz, 1999). Given extended discussion of these ideas in other literature (Reardon & Lenz, 1998), we will not focus on them here but concentrate our attention on the environmental aspects of RIASEC theory in education.

Environments

While the personality aspects of Holland’s theory are widely known, the environmental aspects—especially of college campuses, fields of study, and work positions—are less well understood and appreciated (Gottfredson & Holland, 1996). Holland’s early efforts with the National Merit Scholarship Corporation (NMSC) and the American College Testing Program enabled him to look at colleges and academic disciplines as environments. It is important to note that RIASEC theory had its roots in higher education and later focused on occupations.

Gottfredson and Richards (1999) traced the history of Holland’s efforts to classify educational and occupational environments. Holland initially studied the numbers of incumbents in a particular environment to classify occupations or colleges in terms of RIASEC categories, but he later moved to study the characteristics of the environment independent of the persons in it. College catalogs and descriptions of academic disciplines were among the public records used to study institutional environments. Astin and Holland (1961) developed the Environmental Assessment Technique (EAT) while at the NMSC as a method for measuring college RIASEC environments.

Smart et al. (2000) presented evidence concerning the way academic departments socialize students. They reported that “faculty members in different clusters of academic disciplines create distinctly different academic environments as a consequence of their preference for alternative goals for undergraduate education, their emphasis on alternative teaching goals and student competencies in their respective classes, and their reliance on different approaches to classroom instruction and ways of interacting with students inside and outside their classes” (p. 238). Furthermore, these environments “have a strong socializing influence on change and the stability of students’ abilities and interests—that is, what students do and do not learn or acquire as a consequence of their collegiate experiences” (p. 238). Smart et al. noted that faculty in Investigative, Artistic, Social, and Enterprising disciplines create academic environments in a manner consistent with Holland’s theory, and “the degree to which academic environments are ‘successful’ in their efforts to socialize students to their respective patterns of abilities and interests thus appears to differ considerably, with Artistic and Investigative environments being the most ‘successful’ and the Social and Enterprising environments being less ‘successful’” (p. 146).

These findings suggest that students might best view academic programs in terms of the IASE schema and focus on the kinds of abilities and interests they wish to develop while in college. Such understandings and goal setting could be explored in educational counseling.

Finally, Tracey and Darcy (2002) reported that college students without an intuitive RIASEC schema for organizing information about interests and occupations experience greater career indecision. This finding suggests that the RIASEC hexagon may have a normative benefit regarding the classification of occupations and fields of study. There is increasing evidence that a RIASEC cognitive structure is associated with positive career decision variables (Tracey, 2008). Persons adhering to this structure had stronger career certainty, interest-occupation congruence, and career decision-making self-efficacy at the beginning of a career course than those not using the RIASEC structure. Moreover, teaching this structure in a career course led to increased certainty, congruence, and self-efficacy at the end of the course for those adhering to the model.

Using RIASEC Theory in Educational Counseling

In this section, we discuss the five basic educational counseling functions identified by Hutson (1958), and how Holland’s RIASEC theory might inform this practice. To address these five problems in educational counseling from a RIASEC perspective, it would be important for the counselor to have a basic understanding of Holland’s theory (Holland, 1997). The client might complete the Self-Directed Search (Holland, 1994) and review the Occupations Finder (Holland, 2000), Educational Opportunities Finder (Rosen, Holmberg, & Holland, 1997), and You and Your Career (Holland, 1994) booklets. These materials operationalize and explain the theory in client terms. Armed with this basic information and these tools, the counselor and client can enter into a collaborative relationship to resolve educational problems and make educational decisions.

Choosing a College or School

The number of options for education and training is very large. Choices Planner (Bridges, 2009) was examined for one state and 196 postsecondary schools offering associate, bachelors, and professional (postgraduate) degrees were found. The Choices system makes it possible to use varied criteria for selecting among these options, including five school types, (e.g., public, private), specific miles from a designated ZIP postal code, six regions of the state, five campus or town settings of the school, eight tuition ranges, five affiliations (e.g., women, religious), on-campus housing, and over 30 sports options for men or women. If the student wanted to explore options in additional states the number of options would grow exponentially.

The array of postsecondary schools has very limited options for Realistic and Conventional types, which led Smart et al. (2000) to exclude these areas from their study of baccalaureate level colleges and universities. College level occupations are least frequently associated with the Conventional and Realistic categories, while Investigative and Artistic work are most likely associated with college level employment or the highest level of cognitive ability. Smart et al. found few college majors, faculty, or students in their samples categorized as Realistic or Conventional.

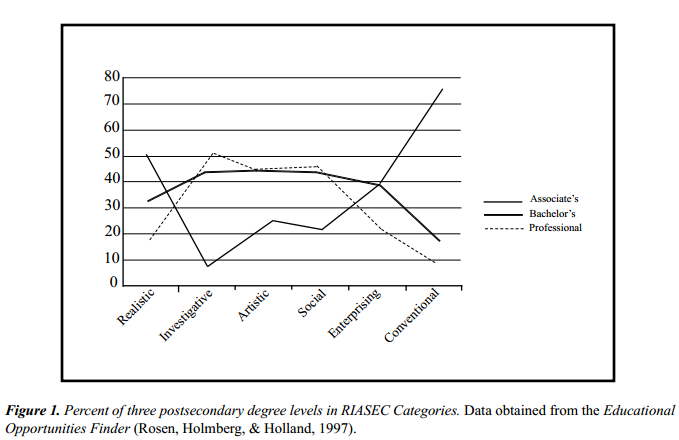

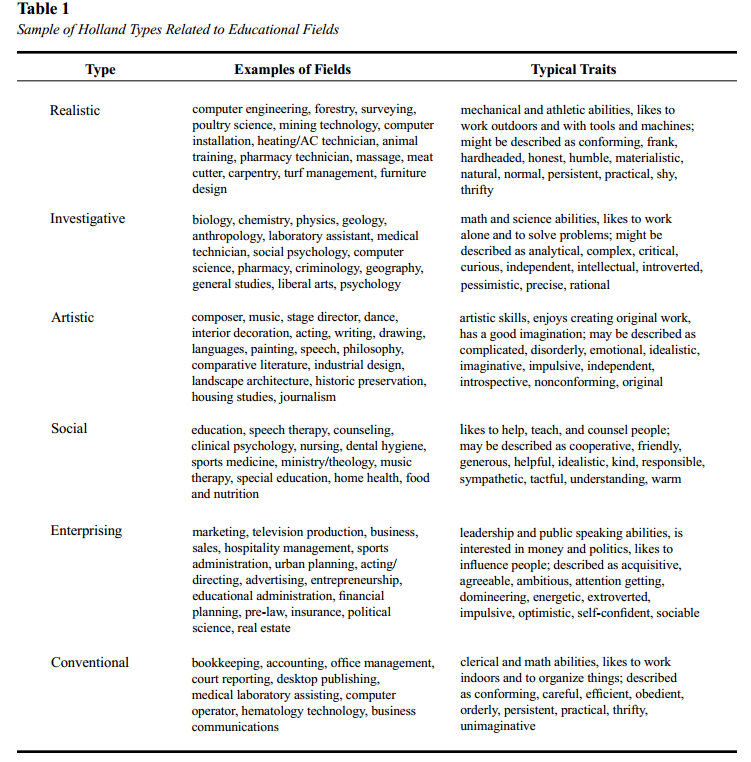

Taking this a step further, the number of associate, bachelors, and professional academic programs listed in the Educational Opportunities Finder (EOF; Rosen et al., 1997) were tabulated in relation to RIASEC categories. Of the 750 postsecondary programs of study listed in the EOF, there were 296 offered at the associate level, 492 at the bachelor’s level, and 645 at the professional level. Because some programs are offered at more than one degree level, the resulting total degree programs listed in the EOF number 1,517. Inspection of Figure 1 shows proportionally more Realistic and Conventional programs are available at the associate degree level in comparison to the other two degrees. Conversely, more professional degrees are offered in the IAS categories. This suggests that vocational technical schools and community colleges would be the types of schools most likely offering programs in these two areas. In this way, RIASEC theory could be used to guide selection of a school.

Authors (1996) documented this phenomenon in their research and reported that the student body at their postsecondary institution was composed predominately of S, E, and I types, creating an SEI-type school. They reported 153 fields of study at the university enrolled 10,439 students with declared majors in the following categories: R, 5%; I, 19%; A, 13%; S, 34%; E, 19%; and C, 10%. This suggests a student body with a profile of SEIACR. Such a student population would find C and R types in a minority.

RIASEC theory can inform the process of choosing a college by providing a conceptual schema of six environments and judging the priority and influence of each in socializing enrolled students. Students with E-type personalities (e.g., interests and skills) might have the best fit in a school that reinforced and prized those traits, and the same would be true for the remaining RIASC environments. In the following sections we will explain more how the environmental aspect of RIASEC theory may be used in educational counseling.

Selecting an Academic Program or Major

The Choices Planner (Bridges, 2009) lists over 780 specific academic programs or fields of study (majors) for students for the selected state. Large universities may have several hundred undergraduate majors and this can be overwhelming to students required to pick one field. Holland’s RIASEC schema can help to make the process of exploring and selecting options less daunting. This section describes some ways this might happen.

First, when students understand the basic elements of RIASEC theory they are armed with a schema for categorizing a great amount of academic information. Table 1 illustrates the operation of this schema in practical terms. Students intent on pursuing a bachelor’s degree can be informed that most college fields of study or disciplines are concentrated in Holland’s Investigative, Artistic, Social, and Enterprising areas (Smart et al., 2000), which reduces hundreds of options to four areas.

Second, the research by Smart et al. (2000) of bachelor’s programs was based on the idea that “faculty create academic environments inclined to require, reinforce, and reward the distinctive patterns of abilities and interests of students in a manner consistent with Holland’s theory” (p. 96). Moreover, “students are not passive participants in the search for academic majors and careers; rather, they actively search for and select academic environments that encourage them to develop further their characteristic interests and abilities and to enter (and be successful in) their chosen career fields” (p. 52). This is an important idea because it puts the power of informed choice in the hands of students as they explore educational options. They can actively select the type of environment in which they desire to spend their time and in which they wish to learn while in college.

Third, Smart et al. (2000) described primary and secondary recruits entering bachelor’s level academic programs. Primary recruits were freshmen entering disciplines directly from secondary school (discussed in this section) and secondary recruits (discussed in the next section) were those who changed their minds after entering college. Based on their research, Smart et al. found that two-thirds of freshmen (primary recruits) initially selected majors in the Social area and remained in that area over four years, while only slightly more than half of the students in the Enterprising area persisted in that area over four years. Students in the Artistic and Investigative areas both persisted over four years at 64%. Overall, about two-thirds of freshmen (primary recruits) persisted in one of the four disciplines initially selected and about 30% changed to another area.

The information gleaned from research by Smart and his colleagues of bachelor’s level programs can help inoculate students for relief of some of the anxiety regarding the selection of an academic program. Rather than simply focusing on the occupations related to a major in making a choice, students can focus on the nature and characteristics of the IASE environments and prioritize them according to their goals, interests, values, and skills. These understandings would also help students search for information about academic programs that provide details about whether or not the way life in the program is consistent or inconsistent with the theoretical RIASEC environment characteristics, e.g., student relationships with professors, classroom activities, nature of learning projects, leadership styles favored.

Adjusting to the College or Academic Program

Faculty in IASE disciplines create specialized academic environments that are shared by the students selecting these majors. The variability in the socialization styles and the effects of the environments on student behaviors and thinking were described by Smart et al. (2000) and are summarized below. Increased understanding of these environmental characteristics is important in educational counseling and for student decisions about preferred fields of study.

Faculty in Investigative environments place primary attention on developing analytical, mathematical, and scientific competencies, with little attention given to character and career development. They rely more than other faculty on formal and structured teaching and learning, they are subject-matter centered, and they have specific course requirements. They focus on examinations and grades. This environment has the highest percentage of primary recruits (e.g., students select it as freshmen).

Faculty in Artistic environments focus on aesthetics and with an emphasis on emotions, sensations, and the mind. The curriculum stresses learning about literature and the arts, as well as becoming a creative thinker. Faculty also emphasize character development, along with student freedom and independence in learning.

Varied instructional strategies are used in these disciplines.

Faculty in Social environments have a strong community orientation characterized by friendliness and warmth. Like the Artistic environment, faculty place value on developing a historical perspective of the field and an emphasis on student values and character development. Unlike the Artistic environment, faculty also place value on humanitarian, teaching, and interpersonal competencies. Colleagueship and student independence and freedom are supported, and informal small group teaching is employed.

The Enterprising environment has a strong orientation to career preparation and status acquisition. Faculty focus on leadership development, the development and use of social power to attain career goals, and striving for common indicators of organizational and career success. Teaching strategies in this environment are very balanced, but faculty like most to work with career-oriented students regarding specialized issues related to organizational and individual achievement.

Once an academic program is selected as a major field of study and the student begins to interact with other students and faculty in the program, more information of a personal nature is acquired which can lead to adjustments that the student will need to make to excel in that environment. For example, when Smart et al. (2000) examined college environments (the percentage of seniors in each of the IASE areas), they found that from 30–50% of the four environments were composed of primary recruits and about half were secondary recruits, e.g., the seniors who had changed their majors. This means that almost half the seniors ended up in an IASE discipline that was different from their initial choice.

Students migrated to and from the four environments in different ways. For example, two-thirds of the seniors in the Artistic environment were secondary recruits from one of the other areas; they did not intend to major in the Artistic area in their freshman year. In addition, about one third of the students migrating into the Social area came from Investigative, Enterprising, or undecided areas. Stated another way, the Social environments appear to be the most accepting and least demanding of the four environments studied by Smart et al. (2000) and Social disciplines seem to have the least impact and the least gains in related interests and abilities. Students moving into the Investigative area were most likely to come from the Enterprising area, and vice versa.

These findings (Smart et al., 2000) reveal the fluid nature of students’ major selections and the heterogeneous nature of the four environments with respect to the students’ initial major preferences. They also provide information regarding the migration of students among the IASE disciplines, and this can inform educational planning for students and counselors about the way in which these four disciplines interact with different types of students.

In summary, Smart et al. (2000) found that congruent students in Investigative, Artistic, and Enterprising environments increased their pattern of self-reported interests and abilities over four years by further developing what was already present in their personality. These three environments also increased the related traits for incongruent students, but the gap between the congruent and incongruent students did not decrease over time. In other words, students in both congruent and incongruent environments made equivalent or parallel changes in self-reported abilities and interests over four years, but students in congruent environments had higher levels of interests and abilities at the end of four years. Investigative and Enterprising environments had the most impact on student characteristics. These findings, if communicated to students in educational counseling, could affect the nature of discussions about students’ educational goals in college.

Assessing Academic Performance

Early in his career, Holland (1957) began to discuss the impact of college on students and how varied personality traits and beliefs other than aptitude were associated with success. Gottfredson (1999) noted that Holland’s early research demonstrated that much of the output from the college experience was related to what students brought into that experience. According to Gottfredson, Holland promoted the idea that college selection practices relying heavily on measures of academic potential resulted in much lost talent, e.g., selection of the top 10% of high school students based only on grades would exclude about 86% of high school class presidents (Enterprising types). The idea that noncognitive traits (e.g., RIASEC personality types) would be important in assessing academic performance is a noteworthy contribution of Holland’s theorizing and research.

Academic success is sometimes measured in terms of persistence on the part of the student or retention on the part of the institution. Other immediate outcome measures might include the grade point average, student satisfaction, awards received, or engagement in program activities, while longer term outcomes might include professional accomplishments, contributions, and recognitions. It should be noted that while all academic programs require cognitive skill and ability, some programs further emphasize interests and abilities related to the RIASEC areas identified in Table 1. These could include creativity, leadership, community service, and the like.

According to RIASEC theory, students in an environment that is highly congruent or matches with their personality will persist in that environment and achieve awards and recognition from the environment. In the process of educational counseling, students should have opportunities to clarify what it means to be in, or move to or out of, an environment that either matches their type or provides an opportunity to develop desired skills and interests. Their achievements and satisfaction would theoretically be related to the quality of the match between their personality and the environmental characteristics.

Connecting Education to Career and Life

Holland’s RIASEC theory provides a relatively simple, effective scheme for thinking about people (e.g., personalities, traits, interests, values, behaviors, attitudes) and their options (e.g., educational programs, occupations, work organizations, leisure activities). Conceptualizing people and options in these six areas can improve personal and career decision making.

Several examples of this strategy are apparent. For example, when students conduct information interviews they might structure questions and make observations about the degree to which the various RIASEC codes are prevalent in the life of the interviewee or characterize the organizational setting. In considering job offers, students might use the RIASEC schema to assess the quality of the fit between their personality and the culture of the organization, or more particularly, the personality of their immediate supervisor.

The UMaps project at the University of Maryland is a good example of applying RIASEC theory to life/career options (Jacoby, Rue, & Allen, 1984). The UMaps program operated out of the Office of Commuter Affairs in the Division of Student Affairs and was designed to help students become aware of diverse campus opportunities, options, and resources related to RIASEC types. Using both large posters displayed on bulletin boards and brochures distributed by advisors, each of the six RIASEC UMaps had a standard layout including areas of study (with office locations and phone numbers), sample career possibilities, internship and volunteer options, and student organizations and activities related to each type. Each map also had a brief description of the RIASEC type and a brief self-assessment related to interests and skills.

As reported earlier, Reardon, Lenz, and Strausberger (1996) used an earlier version of the Educational Opportunities Finder (Rosen et al., 1997) to classify all of the majors at a large university, and then used these data to assess the types of students seeking services in the career center and to design appropriate interventions. For example, it was judged that Realistic and Investigative students might prefer independent career planning using a computer-assisted guidance system, e.g., Choices Planner, rather than an individual counseling session.

Descriptive information about college majors could include the kinds of information summarized by Smart et al. (2000) about course structures, learning style expectations, faculty interests and activities, and program objectives. Other student information materials could list volunteer experiences related to the discipline (if any), introductory classes, sample employment opportunities, and profiles of graduates. Brochures and other descriptive information used in academic advising and educational counseling could be indexed or include information about Holland codes. These examples illustrate the ways in which RIASEC theory applied in educational counseling might be extended to broader life and career decisions.

Summary and Implications

This article illustrates how the educational counseling function has become estranged or lost in traditional counseling practice in secondary and postsecondary settings. While educational counseling can be viewed as distinctive from mental health counseling and/or career counseling, modern career theories can inform the practice of educational counseling for the benefit of students and schools. Holland’s RIASEC career theory, especially the extensive research on educational environments conducted by Smart and his associates (2000) and reported in more than six different journals, was used to illustrate this idea.

Educational counselors using RIASEC theory need to be fully informed about the theory, the research that supports it, the instruments that are based upon it, and the counseling techniques that could be derived from it. Such theory-driven practice might represent a new paradigm in educational counseling. Holland’s (1997) theory, like other career theories, has the most power when the extremes of wealth, social class, genetic traits, and health are not in effect. In other words, career theory probably works best in educational counseling for students in general rather than those at the extremes of any personal trait or situation.

RIASEC theory can be useful in educational counseling by specifying the kinds of conditions and traits associated with difficulties in educational decision making. Authors (1998, 1999) and Holland, Gottfredson, and Nafziger (1975) indicated that persons with poor diagnostic signs on the Self-Directed Search, e.g., lack of congruence between expressed and assessed summary codes, low differentiation, low consistency, low coherence among aspirations, low profile elevation, and a high point code in the Realistic or Conventional area, were likely candidates for more intensive counseling interventions. This is a special province of educational counselors because of their professional counselor training as opposed to the standard training for academic advisors or coaches. Students with high Artistic codes also may be problematic because of their preference for a non-rational approach to decision making (Holland et al., 1975). Persons with such diagnostic signs will likely need more time and professional, individualized counselor assistance in career problem solving and decision making.

Smart et al.’s (2000) research reveals some of the variations in academic departments and suggests implications for college and university organizational systems. It is important for counselors and other staff to inform students about the impact of majors and academic disciplines on the development of student interests and skills. At present, advisors make students aware of many aspects of a major, e.g., required courses, prerequisites, entrance requirements, and the occupations most closely aligned with the major. Providing additional information based on the research findings by Smart et al. regarding the way academic environments socialize or affect students pursuing that major will make students better “consumers” of majors or “shoppers” of academic programs.

References

Astin, A. W., & Holland, J. L. (1961). The Environmental Assessment Technique: A way to measure college environments. Journal of Educational Psychology, 52, 308–316.

Breaking News: 20/20 Delegates Reach Consensus Definition of Counseling. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/20-20/index.aspx, May 7, 2010.

Brewer, J. (1932). Education as guidance. New York, NY: Macmillian.

Bridges.com Co. (2009). Choices [Computer software]. Oroville, WA: Author.

Brown, D. (Ed.). (2002). Career choice and development (4th. ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chung, Y. B., & Gfroerer, M. C. A. (2003). Career coaching: Practice, training, professional, and ethical issues. Career Development Quarterly, 52, 141–152.

Creamer, D. G. (2000). Use of theory in academic advising. In V. N. Gordon & W. R. Habley (Eds.), Academic advising: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 18–34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Dawis, R. V. (2002). Person-environment-correspondence theory. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 427–464). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ender, S. C., Winston, Jr., R. B., & Miller, T. K. (1984). Academic advising reconsidered. In R. B. Winston, Jr., T. K. Miller, S. C. Ender, & T. J. Grites (Eds.), Developmental academic advising: Addressing students’ educational, career, and personal needs (pp. 3–34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ginzberg, E., Ginsburg, S., Axelrad, S., & Herma, J. L. (1946). Occupational choice. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gladding, S. T. (2006). The counseling dictionary: Concise definitions of frequently used terms (2nd. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Gottfredson, G. D. (1999). John L. Holland’s contributions to vocational psychology: A review and evaluation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 15–40.

Gottfredson, G. D., & Holland, J. L. (1996) The dictionary of Holland occupational codes. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2002). Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription, compromise, and self- creation. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 85–148). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Gottfredson, L. S., & Richards, J. M., Jr. (1999). The meaning and measurement of environments in Holland’s theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 57–73.

Harmon, L. W., Hansen, J. C., Borgen, F. H., & Hammer, A. L. (1994). Strong Interest Inventory: Applications and technical guide. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Heffernan, J. M. (1981). Educational and career services for adults. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices (3rd. ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (2000). Occupations finder. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (1994). The Self-Directed Search. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (1957). Undergraduate origins of American Scientists. Science, 126, 433–437.

Holland, J. L. (1994). You and your career. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J., Gottfredson, G., & Nafziger, D. (1975). Testing the validity of some theoretical signs of vocational decision-making ability. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22, 411–422.

Hutson, P. W. (1958). The guidance function in education. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Jacoby, B., Rue, P., & Allen, K. (1984). U-Maps: A person-environment approach to helping students make critical choices. Personnel & Guidance Journal, 62, 426–28.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. 2002). Social cognitive career theory. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th. ed., pp. 255–311). San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass.

Patterson, J. (2008). Counseling vs. life coaching. Counseling Today, 5(6), 32–37.

Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. (2009). PAR catalog of professional testing resources, 32(4), 235–247.

Reardon, R. C., & Lenz, J. L. (1999). Holland’s theory and career assessment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 102–113.

Reardon, R. C., & Lenz, J. L. (1998). The Self-Directed Search and related Holland career materials: A practitioner’s guide. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Reardon, R. C., Lenz, J. L., & Strausberger, S. (1996). Integrating theory, practice, and research with the Self-Directed Search: Computer Version (Form R). Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 28, 211–218.

Rosen, D., Holmberg, K, & Holland, J. L. (1997). The educational opportunities finder. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Ruff, E. A., Reardon, R. C., & Bertoch, S. C. (2008, June). Holland’s RIASEC theory and\applications: Exploring a comprehensive bibliography. Career Convergence, http://209.235.208.145/cgibin/WebSuite/tcsAssnWebSuite.pl?Action=DisplayNewsDetails&RecordID=1164&Sections=3&IncludeDropped=0&NoTemplate=1&AssnID=NCDA&DBCode=130285.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Reardon, R. C., Peterson, G. W., & Lenz, J. L. (2004). Career counseling and services: A cognitive information processing approach. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth-Brooks/Cole.

Savickas, M. (2002). Career construction: A developmental theory of vocational behavior. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th ed., pp.149–205). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Shertzer, B., & Stone, S. C. (1976). Fundamentals of guidance (3rd. ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Smart, J. C., Feldman, K. A., & Ethington, C. A. (2000). Academic disciplines: Holland’s theory and the study of college students and faculty. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Stephens, J. (1970). Social reform and the origins of vocational guidance. Washington, DC: NVGA.

Super, D. E., Savickas, M. L., & Super, C. M. (1996). The life-span, life-space approach to careers. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates, Career choice and development (3rd ed., pp. 121–170). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Tracey, T. J. G. (2008). Adherence to RIASEC structure as a key career decision construct. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 146–157.

Tracey, T. J. G., & Darcy, M. (2002). An idiothetic examination of vocational interests and their relation to career decidedness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 420–427.

VandenBos, G. R. (Ed.). 2007). APA dictionary of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Young, R., Valach, L., & Collin, A. (2002). A contextualist explanation of career. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th. ed., pp. 206–254). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Robert C. Reardon, NCC, is Professor Emeritus and Sara C. Bertoch, NCC, is a career advisor, both at the Career Center at Florida State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Robert C. Reardon, Florida State University Career Center,

PO Box 3064162, Tallahassee, FL, 32306, rreardon@fsu.edu.

Sep 4, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

John E. Mabey

Consideration of older adult lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in gerontological research is lacking, leaving professional counselors without a substantive bridge with which to connect resources with treatment planning when working with sexual minorities. Therefore, presented here is an overview of aging research related to older adult LGBT individuals. The importance of individuality among LGBT individuals and suggestions for professional counselors who work with both individuals and couples in these populations also are presented.

Keywords: LGBT, older adults, gerontology, aging research, individuality

Multidisciplinary in nature, gerontology encompasses the study of dynamic processes of aging as experienced on the social, psychological, and biological levels (Hooyman & Kiyak, 2008). Knowledge of gerontology therefore enables professional counselors to work more effectively with older clients by facilitating understanding of their worldview. Professional counselors thus are better able to contextualize how aging itself is not the pathology, but rather the context that influences other aspects of the client’s life.

Due to advances in medical care and quality of life, the average lifespan in the U.S. is being prolonged and the percentage of those reaching old age is increasing dramatically (Dobrof, 2001). According to recent U.S. Census data (2008), the number of Americans aged 85 years and older will increase from 5.4 million in 2008 to 19 million by the year 2050. In addition, about 1 in 5 U.S. residents will be age 65 or older by 2030. It is not uncommon in professional literature and research to differentiate old age into categories, such as the young old, typically between 60 to 79, and the old old, typically 80 and above, to capture more accurate developmental data at different stages of the life cycle (Grossman, 2008; McFarland & Sanders, 2003; Quam, 1993; Quam, 2004; Quam & Whitford, 2007). Although relatively arbitrary, such categories do point to the fact that there are developmental differences even among older adults.

Older adult sexual minorities have been relatively ignored in gerontological research (Apuzzo, 2001; Cook-Daniels, 1997; Grossman, 2008; Kimmel, 1979; Orel, 2004; Quam, 2004). It is estimated that there are between 1 and 3 million individuals in the U.S. over age 65 who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) (Jackson, Johnson, & Roberts, 2008; McFarland & Sanders, 2003), and that number is expected to increase substantially in the next 15 years (Penn, 2004). Unfortunately, whether because of discriminatory bias against LGBT individuals or the invisibility of sexual identity within older adult populations in the larger society, most professional counselors find themselves lacking in general knowledge about this growing population and therefore ill-equipped to provide professional services for them.

Older adults, whether heterosexual or part of the LGBT community, confront many concerns about aging, including financial matters, health, companionship, independence (Quam & Whitford, 1992), loss, and residence concerns (MetLife, 2006). All older adults also face issues and stereotypes surrounding ageism (Wright & Canetto, 2009), including discriminatory attitudes and behaviors against older persons (Hooyman & Kiyak, 2008). However, ageism as experienced in LGBT communities has the additional impact of making a stigmatized group feel even more of a minority (Brown, Alley, Sarosy, Quarto, & Cook, 2001; Drumm, 2005; Jones, 2001; Jones & Pugh, 2005; Kimmel, Rose, Orel, & Greene, 2006; Meris, 2001) .

Additional concerns unique to older adult LGBT individuals include the ability to make legal decisions for each other as couples/partners, lack of support from family who might not recognize or respect their sexuality, and homophobic discrimination in healthcare and other services. Older adult LGBT persons often face unparalleled discrimination and harassment in residential care facilities (Johnson, Jackson, Arnette, & Koffman, 2005; Phillips & Marks, 2008). While elder abuse is recognized as a significant problem among older adults in general, unfortunately there is a deficiency of specific knowledge about abuse for older adult LGBT persons (Moore, 2000). Thus, in the vast majority of situations, mainstream services for older adults are not meeting the specific and unique needs of the older adult LGBT population (Slusher, Mayer, & Dunkle, 1996).

Older adult LGBT individuals have lived through distinctively oppressive social climates for sexual minorities compared to more recent generations. Their early developmental years were marked by a typically homophobic culture in which homosexuality was overtly and profoundly admonished, and included messages from national and local leaders that their sexuality was immoral, pathological, and often illegal. For example, the old old grew up in an era during which President Eisenhower ordered all homosexuals to be fired from government jobs and Senator McCarthy sought to ‘expose’ communists and homosexuals (Kimmel, 2002). Without a more organized movement in place in that era to combat the rampant homophobia and negative stereotyping, blatant fear and dislike of homosexuality was seen in nearly all political, educational, and religious institutions. Indeed, the general lack of support for LGBT individuals in religious institutions continues today, leaving many in the position of a forced choice between two fundamental components of their sense of self: spirituality and sexuality. “In turn, this conflict can manifest itself through internalized disorders, such as depression, or through externalized disorders, such as risky or suicidal behavior” (Mabey, 2007, p. 226). However, it is important for professional counselors to be aware of the distinction many older adult LGBT persons make between spirituality and religiosity; religious dogma against homosexuality does not prevent many LGBT individuals from maintaining a strong spiritual identity (Mabey, 2007; Orel, 2004).

The young old, though, became adults during a time of more relatively progressive changes in society. The Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village in 1969, in which gay and transgender individuals physically fought back against unjust police harassment, marked a milestone in what would eventually become the modern gay rights movement. In the mid-1970s, homosexuality was finally declassified as a mental disorder within both the American psychiatric and psychological professional communities (but only after decades of miseducating medical and mental health professionals about the pathologic nature of sexual minorities).

As professional counselors work with an aging LGBT population, it is important to consider this historically negative climate which shaped an individual’s experiences with, and impressions of, her or his own sexual identity (Berger, 1982). For the older adult LGBT individual, consequently, there might exist a sense of internalized homophobia (D’Augelli, Grossman, Hershberger, & O’Connell, 2001; Heaphy, 2007; Porter, Russell, & Sullivan, 2004) that contributes to nonparticipation in LGBT-supportive services and associated diminished overall mental health. These individuals also are less likely to seek any general health services for fear of having to disclose their sexual orientation to a possibly homophobic provider (Brotman, Ryan, & Cormier, R., 2003; Grossman, D’Augelli, & Dragowski, 2007; Sussman-Skalka, 2001). For example, refer to Zodikoff (2006) for vignettes that highlight unique aspects of social work practice with a diverse and aging LGBT population.

Aging and Individuality

Professional counselors should recognize that an older adult LGBT individual does not belong to one homogenous group within the LGBT acronym. For example, a gay youth living in New York City at the time of the Stonewall Riots will have experienced the movement in vastly different ways than, say, a gay youth then living in the rural Midwest. Similarly, a transgender individual involved in the Stonewall Riots will have faced different experiences than a gay male in those same riots because of the greater concealment of transgender individuals. Cook-Daniels (1997) wrote, “Lesbian and Gay male elders have been called an ‘invisible’ population (Cruikshank, 1991). If they are invisible, then transgendered elders have been inconceivable” (p. 35).

Transgender older adults also face unique challenges apart from those who are lesbian, gay, or bisexual (Cook-Daniels, 2006). For example, health concerns for those transitioning from male to female (MTF) or female to male (FTM) are greater because surgeries become more complicated with age. However, there has been a significant increase in the number of those willing to face the risk of transitioning in later life because of vastly improved methods of electronic communication about options, new research, and medical procedures (Cook-Daniels, 2006).

Another challenge to older adult transgender individuals is that most older adults in society, including gay and lesbian older adults, have well-established social roles and relationships. Thus, MTF or FTM transitioning becomes more difficult with age because of the need for changed manners of speech and gesticulations. Legal issues include additional unique challenges as a change in gender is often associated with changed governmental benefits. For example, a formerly heterosexual marriage might be seen as an illegal same-sex marriage after one spouse transitions, and then formerly anticipated benefits, such as Social Security, might be revoked.

As professional counselors work with the older adult transgender population, there are several important aspects about this community to be considered in treatment planning (Cook-Daniels, 2006). First, although transphobia in the medical community and healthcare facilities has not been adequately researched, it is well-documented (Donovan, 2001). Therefore, making effective referrals necessitates that the new service provider be familiar and comfortable with the transgender population. Professional counselors also should understand the roadmap for individuals who are transitioning, and in particular how they need to be declared mentally fit as well as diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder before any treatment for transitioning may commence. Professional counselors also should understand that persons in MTF or FTM are often perceived to be, “…mentally ill until proven otherwise, and they are fearful and angry that—to a degree that is rivaled perhaps only by prisoners and the severely domestically abused—their life choices are under someone else’s control” (Cook-Daniels, 2006, p. 25). To the extent that a transgender person holds this perspective, it might interfere with his or her level of comfort in seeking the services of a mental health professional at all.

Transgendered individuals also cannot control the coming-out process of their gender identity because visual or auditory cues may expose their status, and therefore they are left open to the opinions and reactions of others they encounter. Thus, it is important for professional counselors to assess their own comfort levels, and meeting transgender individuals or volunteering in an organization that serves this population is a great way to increase familiarity with and knowledge about this group. It also is important to recognize that transgendered individuals face financial constraints that are usually greater than those typically encountered by other gay, lesbian, or bisexual elders due to hormone medication or surgical procedures that are usually not covered by insurance. Therefore, as with other clients experiencing financial constraints, professional counselors might employ a sliding-fee scale depending on their client’s stage of transition and/or individual circumstances.

Bisexual individuals also experience a sense of invisibility within the LGBT community. As another underrepresented group in professional research literature, the needs and experiences of bisexual older adults also are often misunderstood. Professional counselors likely will work with bisexual clients during their careers, and should approach treatment without the erroneous assumption that sexuality is necessarily dichotomous (Dworkin, 2006).

Ageism typically precludes recognizing the sexuality of older adults (Hooyman & Kiyak, 2008). However, it is an important element. Consider a professional counselor who meets an older adult client who is happily married to a member of the opposite sex. That counselor likely will not consider that the client may in fact be bisexual—but it may be the case. Indeed, coming out as bisexual during a heretofore heterosexual marriage is the point at which a professional counselor might most be needed as issues of intimacy and restructuring of familial dynamics are addressed.

There also is the myth of the impossibility of monogamous relationships for bisexual individuals that should be considered by professional counselors (Dworkin, 2006). Simply because a person has the capacity for attraction and/or commitment to both males and females does not mean that the individual is unfulfilled with a monogamous relationship or that polyamorous relationships are necessarily seen as negative.

Aging Research and Identity

Differences among individuals within the “LGBT” acronym highlight the necessity for a professional counselor to understand the complex nature of identity. Through a shared history, current activism, and support networks, individuals within the LGBT community have much in common with one another. However, they also have differences. In building rapport with an older adult client, a professional counselor should recognize these differences (beyond commonly understood stereotypes). For an older adult LGBT client, having a well-informed professional counselor is essential to relationship-building and establishing trust, i.e., a comfortable environment in which LGBT history can be addressed and acknowledged.

Comprised of persons of every nationality, socioeconomic status, gender, ability level, race and ethnicity, the older adult LGBT population cannot be grouped or treated as one cohesive category. Unfortunately, research about LGBT elders is still underrepresented in gerontological literature, and representative samples of populations within that body of research are even more limited (Berger & Kelly, 2001; Butler, 2006; Grossman, D’Augelli & Hershberger, 2000; Jackson, et al., 2008; Kimmel, 2002; Quam & Whitford, 1992). Indeed, because of a variety of factors, such as “closeted” older adults and the lack of organized LGBT communities in some areas, no economically feasible method is available to generate a random sample of older LGB(T) individuals (Grossman, et al., 2000). Professional counselors must also consider this limitation when reviewing research, and how a significant number of studies have been conducted with LGBT individuals with limited sample sizes (and who primarily were Caucasian, highly educated, affluent, self-identified, younger, male individuals living in urban areas) (Dworkin, 2006; Grossman, D’Augelli, & O’Connell, 2001; Hash, 2006; McFarland, & Sanders, 2003; Porter, et al., 2004). Within the professional research and literature on older adult LGBT individuals, there exists a substantial gap in representation of people of color, the old old, and those living in rural areas.

Professional counselors should inquire of each older adult LGBT client about level of identification with an LGBT identity or community. Indeed, a professional counselor may be better educated about LGBT history and circumstances than the client, and therefore may be able to facilitate the older adult LGBT client’s identity development. Indeed, it is rare for an older adult LGBT individual to have had LGBT parents, and therefore they are not necessarily taught this cultural history or coping strategies for overcoming homophobia, biphobia, or transphobia in the traditional family setting. Regardless, the ability of a professional counselor to access such information during a session is an important skill for relationship-building and even for educating the client regarding homework or making referrals.

As professional counselors consider the impact of an LGBT identity for the older adult individual, it also is important to not view that identity as necessarily problematic (Berger, 1982). In fact, researchers point to the idea of “crisis competence,” in which the coming-out process enables the individual to develop a competency for dealing with other crises in the lifespan, including difficulties associated with the adjustment to aging (Heaphy, 2007; Kimmel, 2002; McFarland & Sanders, 2003; MetLife, 2006; Morrow, 2001; Quam, 1993).

Additional Skills for Professional Counselors

Sometimes an older adult individual in the LGBT community has difficulty coping with the stressors of homophobia and coming-out, and professional counselors might witness psychological distress or unhealthy behaviors. Kimmel (2002) outlines suggestions that can be adapted by mental health professionals to enhance the development of crisis competency and combat maladaptive thoughts and behaviors with this population. The suggestions include to:

• Aid the client to discover any familial or peer support.

• Identify positive role models locally or nationally that embody characteristics to which the client would aspire.

• Practice the use of effective coping skills.

• Assist in managing the integration of their multiple identities to enhance their sense of self.

Because the number of older adult individuals in the U.S. is expected to increase dramatically in the next 20 to 50 years, the number of older adult LGBT individuals will continue to grow as well. Professional counselors, working with these often misunderstood populations, face the additional challenge of treating LGBT elders with limited research or experience. Quam, Knochel, Dziengel, and Whitford, (2008) offer practical suggestions for working with same-sex couples that are adapted for work with older adult LGBT individuals:

• Your older adult client may define “family” as close friends who have assumed the role of absent families of origin. These fictive kin must be treated with the same respect as other family members.

• Because of anti-LGBT attitudes, your older adult client’s biological or adoptive family may not be providing elder care. This care might instead be provided by fictive kin or not at all.

• Your older adult client might also be a caregiver for another elderly individual, especially as fictive kin play an important role in LGBT communities and caregiving.

• Your older adult client may have biological or adoptive children.

• Be knowledgeable about legal protections such as a will, power of attorney and a health care directive, as there are limited benefits for same sex couples (being denied visitation rights in a hospital when their partner is injured or gravely ill is a possibility).

• Confidentiality is essential when working with an older adult LGBT individual, specifically because of realistic fears about anti-LGBT attitudes in the medical field or treatment facilities. Therefore, disclosing your client’s sexual orientation without permission, even to another LGBT individual, should be strictly avoided.

• Familiarize yourself with older adult LGBT services and communities. An example is SAGE (Services and Advocacy for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Elders), a comprehensive social service agency with chapters across the country (http://www.sageusa.org).

As professional counselors continue to balance a scholar-practitioner role, increased research and experience with LGBT older adults and their aging will promote and elevate the counseling profession. It also will serve to enrich the lives of millions of LGBT older adults and their supporters. Both historically and in contemporary times, the counseling profession thrives as a fertile ground for pioneering and ground-breaking research; LGBT aging represents a generally underexplored but vital new challenge. Indeed, the dynamic and diverse nature of older adult LGBT communities provides opportunity for expanding academic inquiry and new and innovative treatment modalities in the counseling profession.

References

Apuzzo, V. M. (2001). A call to action. The Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 1–11.

Berger, R. M. (1982). The unseen minority: Older gays and lesbians. Social Work, May Issue, 236–242.

Berger, R. M., & Kelly, J. J. (2001). What are older gay men like? An impossible question? Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 55–64.

Brotman, S., Ryan, B., & Cormier, R. (2003). The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 192–202.

Brown, L. B., Alley, G. R., Sarosy, S., Quarto, G., & Cook, T. (2001). Gay men: Aging well! Journal of gay and Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 41–54.

Butler, S. S. (2006). Older gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender persons. In B. Berkman (Ed.), The handbook of social work in health and aging (pp. 273–281). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Cook-Daniels, L. (1997). Lesbian, gay male, bisexual, and transgender elders: Elder abuse and neglect issues. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 9(2), 35–49.

Cook-Daniels, L. (2006). Trans aging. In D. Kimmel, T. Rose, & S. David (Eds.), Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender aging – Research and clinical perspectives (pp. 20–35). NewYork, NY: Columbia University Press.

D’Augelli, A. R., Grossman, A. H., Hershberger, S. L., & O’Connell, T. S. (2001). Aspects of mental health among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Aging & Mental Health, 5(2), 149–158.

Dobrof, R. (2001). Aging in the United States today. The Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 15–17.

Donovan, T. (2001). Being transgender and older: A first person account. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 19–22.

Drumm, K. (2005). An examination of group work with old lesbians struggling with a lack of intimacy by using a record of service. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 44(1–2), 25–52.

Dworkin, S. H. (2006). The aging bisexual—The invisible of the invisible minority. In D. Kimmel, T. Rose, & S. David (Eds.), Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender aging—Research and clinical perspectives (pp. 36–52). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Grossman, A. H. (2008). Conducting research among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 20 (1–2), 51–67.

Grossman, A. H., D’Augelli, A. R., & Dragowski, E. A. (2007). Caregiving and care receiving among older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 18(3–4), 15–38.

Grossman, A. H., D’Augelli, A. R., & Hershberger, S. L. (2000). Social support networks of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults 60 years of age and older. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 55B(3), 171–179.

Grossman, A. H., D’Augelli, A. R., & O’Connell, T. S. (2001). Being lesbian, gay, bisexual, and 60 or older in North America. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 23–40.

Hash, K. (2006). Caregiving and post-caregiving experiences of midlife and older gay men and lesbians. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 47(3), 121–138.

Heaphy, B. (2007). Sexualities, gender and ageing. Current Sociology, 55(2), 193–210.

Hooyman, N. R., & Kiyak, H. A., (2008). Social gerontology: A multidisciplinary perspective (8th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Jackson, N. C., Johnson, M. J., & Roberts, R. (2008). The potential impact of discrimination fears of older gays, lesbians, bisexual, and transgender individuals living in small-to moderate-sized cities on long-term health care. Journal of Homosexuality, 54(3), 325–339.

Johnson, M. J., Jackson, N. C., Arnette, J. K., & Koffman, S. D. (2005). Gay and lesbian perceptions of discrimination in retirement care facilities. Journal of Homosexuality, 49(2), 83–102.

Jones, B. E. (2001). Is having the luck of growing old in the gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender community good or bad luck? The Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 13–14.

Jones, J., & Pugh, S. (2005). Ageing gay men: Lessons from the sociology of embodiment. Men and Masculinities, 7(3), 248–260.

Kimmel, D. (1979). Life-history interviews of aging gay men. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 10(3), 239–248.

Kimmel, D. C. (2002). Aging and sexual orientation. In Jones, B. E., & Hill, M. J. (Eds.), Mental health issues in lesbian, gay. bisexual, and transgender communities (pp.17–36). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Kimmel, D., Rose, T., Orel, N., & Greene, B. (2006). Historical context for research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender aging. In D. Kimmel, T. Rose, & S. David (Eds.), Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender aging—Research and clinical perspectives (pp. 1–19). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Mabey, J. E. (2007). Spirituality and religion in the lives of gay Mmn and lesbian women. In L. Badgett, & J. Frank (Eds.), Sexual orientation discrimination: An international perspective (pp. 225–235). London, England: Routledge.

McFarland, P. L., & Sanders, S. (2003). A pilot study about the needs of older gays and lesbians: What social workers need to know. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 40(3), 67–80.

Meris, D. (2001). Responding to the mental health and grief concerns of homeless HIV-infected men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 103–111.

MetLife Mature Market Institute in conjunction with the Lesbian and Gay Aging Issues Network of the American Society on Aging and Zogby International (2006). Out and aging: The MetLife study of lesbian and gay baby boomers.

Moore, W. R. (2000). Adult protective services and older lesbians and gay men. Clinical Gerontologist, 21(2), 61–65.

Morrow, D. F. (2001). Older gays and lesbians: Surviving a generation of hate and violence. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 13(1–2), 151–169.

Orel, N. A. (2004). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 43(2), 57–77.

Penn, D. (2004, April). Groups collaborate to build affordable housing for LGBT seniors. Lesbian News, p.15.

Phillips, J., & Marks, G. (2008). Ageing lesbians: Marginalizing discourses and social exclusion in the aged care industry. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 20 (1–2), 187–202.

Porter, M., Russell, C., & Sullivan, G. (2004). Gay, old, and poor: Service delivery to aging gay men in inner city Sydney, Australia. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 16(2), 43–57.

Quam, J. K. (1993). Gay and lesbian aging. SIECUS Report, 21 (5), 10–12.

Quam, J. K. (2004) Issues in gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender aging. In W. Swan (Ed.), Handbook of gay, lesbian and transgender administration and policy (pp.137–156). New York, NY: Marcel Dekker.

Quam, J. K., Knochel, K., Dziengel, L., & Whitford, G. S. (2008). Understanding long-term same-sex couples. Retrieved from the College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota, website: http://www.cehd.umn.edu/ssw/research/posterpdfs/Knochel_poster.pdf

Quam, J. K., & Whitford, G. S. (1992). Adaptation and age-related expectations of older gay and lesbian adults. The Gerontologist, 32(3), 367–374.

Quam, J. K., & Whitford, G. S. (2007). Gay and lesbian aging. In E. A. Capezuti, E. L. Siegler, & M. D. Mezey (Eds.), The encyclopedia of elder care (pp.339–341). New York, NY: Springer.

Slusher, M. P., Mayer, C. J., & Dunkle, R. E. (1996). Gays and lesbians older and wiser (GLOW): A support group for older gay people. The Gerontologist, 36(1), 118–123.

Sussman-Skalka, C. (2001). Vision and older adults. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 13(4), 95–101.

U.S. Census Bureau (2008). An older and more diverse nation by midcentury. Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/012496.html

Wright, S. L., & Canetto, S. S. (2009). Stereotypes of older lesbians and gay men. Educational Gerontology, 35, 424–452.

Zodikoff, B. D. (2006). Services for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. In B. Berkman & S. D’Ambruoso (Eds.), Handbook of social work in health and aging (pp. 569–575). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

John E. Mabey, NCC, is Editor and Facilitator at University-Community Partnership for Social Action Research Network (UCP-SARnet). Correspondence can be addressed to John E. Mabey, University-Community Partnership for Social Action Research Network, Arizona State University, P.O. Box 871104, Tempe, AZ, 85287, johnmabeyadvisor@hotmail.com.

Sep 3, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 3

Cody J. Sanders

Given the increasing popularity of narrative and collaborative therapies, this article undertakes an examination of the postmodern theory underlying these therapies. This consideration gives particular attention to issues of power and knowledge in therapeutic practice, examined both within clients’ narratives and within the therapeutic alliance. Implications on the role of counselors in recognizing and addressing power within clinical practice is likewise detailed.

Keywords: collaborative therapies, postmodern theory, narrative, knowledge, power, stories

Knowledge and power, terms used frequently in everyday vernacular, carry particular nuanced meaning and significant weight in discussions of postmodern therapies. Narrative therapies, in particular, bear the marks of significant shaping by notions of knowledge and power that are given particular form through a process of postmodern critique. While narrative therapy and other collaborative-based postmodern therapies have much to offer in the way of method for counseling practice, one would miss the significance of methodological structure without first understanding the philosophical underpinnings. While postmodern thought is often referred to in a unified manner, it is important to note that postmodern influences on therapy do not stem from a unified system or philosophy called “postmodernism.” Instead, postmodern influences may be most clearly articulated as a critique of the assumptions of modernism. Modernist thought can be traced throughout the foundations of the psychotherapeutic theories and modalities that have dominated the field from Freud to the present. While narrative therapy certainly runs counter to many modernist assumptions in counseling, it is sometimes difficult to see the significance of postmodern influences without first illustrating how they provide a critique to modernist assumptions. As McNamee (1996) states, “We often do not recognize the mark of modernism because it has inscribed itself on our way of living” (p. 121). Thus, it is necessary at the outset of this exploration to provide a contrast between modern and postmodern thought as it relates to the field of counseling in order to more fully articulate the importance of the concepts of knowledge and power in the theory and practice of narrative therapy.

Modern and Postmodern Thought in Counseling