Stefanie Rodriguez

The career decision-making process can be a daunting task during the college years for both athletes and non-athletes alike. Understanding factors that influence this process and ways to best support students as they are making career decisions is integral to counselors working with college students. Social support and career thoughts were examined in 118 college student-athletes and 154 non-athletes from a large public university in the southeastern United States. Social support was found to have a significant relationship with career thoughts. In addition, several significant differences were found between the study’s subpopulations. Implications for practice and future directions for research are further explored.

Keywords: career decisions, college athletes, social support, career counseling, sociocultural context

Career planning is a process in a college student’s life that can cause a considerable amount of stress, and social support can have a positive effect on this stress. In the sport psychology research, social support has been found to be an important factor in reducing the effects of stress in athletes’ lives (Bianco & Eklund, 2001; Taylor & Ogilvie, 2001). Athletes not only experience stress related to academics and athletics, but also related to what they will do after college. Some are talented enough to play professionally, but many must face the reality of having a career outside of the realm of sports. As a result, career planning is an important process for college athletes because it prepares them for life after sports. Social support can be an important factor during this process by alleviating the stress associated with career planning.

In research examining the general college student population, career thoughts have been found to have an important effect on the career planning process (Peterson, Sampson, & Reardon, 1991; Peterson, Sampson, Reardon, & Lenz, 1996; Sampson, Peterson, Lenz, Reardon, & Saunders, 1996b; Sampson, Reardon, Peterson, & Lenz, 2009). If career thoughts are negative, the individual is unable to clearly evaluate self and occupational knowledge that is necessary to make a career decision. Decreasing negative thoughts is the first and most important step in the career decision-making process. In conclusion, it is important for those who are influential in college students’ lives to know what types of social support have the strongest relationship with the thoughts related to a career after college.

Social Support

Social support refers to the “social interaction aimed at inducing positive outcomes” (Bianco & Eklund, 2001, p.85). The terms “provider” and “recipient” are often used when discussing social support. A provider is an individual who gives the social support, and a recipient is an individual who receives the social support. A theory that targets social support and recipient satisfaction is the person-environment fit theory (Brown, 2002). This theory posits that the interaction between the person and environment is both active and reactive. The person-environment fit model of satisfaction is a part of person-environment theory. It defines satisfaction as “a pleasant affective state that is produced by the degree of fit between a person’s needs, personality characteristics, abilities, and the commensurate supplies provided by, and abilities requirements of, the environment” (Brown, Brady, Lent, Wolfert, & Hall, 1987, p. 338). Conversely, dissatisfaction is defined as “an unpleasant affective state resulting from a misfit between relevant person and environment characteristics” (Brown et al., 1987, p. 338).

In many cases, person-environment fit is considered subjective because it focuses on the perceptions of the person. Within the context of subjective person-environment fit, satisfaction with social support is defined as “a positive affective state resulting from one’s appraisal or his or her social environment in terms of its success in meeting his or her interpersonal needs” (Brown et al., 1987, p. 338). Conversely, dissatisfaction with social support is defined as “an unpleasant affective state resulting from a perception that the interpersonal environment is failing to satisfy important interpersonal needs” (Brown et al., 1987, p. 338).

Using person-environment fit as a theoretical basis, Brown, Alpert, Lent, Hunt, and Brady (1988) defined five broad factors of social support: (a) acceptance and belonging, (b) appraisal and coping assistance, (c) behavioral and cognitive guidance, (d) tangible assistance and material aid, and (e) modeling. The first factor, acceptance and belonging, measures the degree to which the individual’s needs for affiliation and esteem are met through the provision of love, acceptance, respect, belonging, and shared communication. The second factor, appraisal and coping assistance, relates to the degree to which the social environment provides the individual with emotional support, hope, and coping assistance through assurances that feelings are normal, positive reinterpretations of the situation and future, and information on coping skills during times of stress.

The third factor, behavioral and cognitive guidance, relates to the degree to which the social environment meets the individual’s needs for direct and modeled feedback about appropriate behaviors and thoughts. The fourth factor, tangible assistance and material aid, pertains to the degree to which instrumental needs for money, goods, and services are met by the social environment. The fifth and final factor, modeling, refers to the information on how others feel, handle situations and think (Brown et al., 1988). It also measures the satisfaction with a model or example to follow. In conclusion, the person-environment fit theory provides a basis for the description of five types of social support. In order to fully understand the role of social support on the career planning process, it also is essential to understand the role of career thoughts in the process.

Career Thoughts

Career thoughts are defined as “outcomes of one’s thinking about assumptions, attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, feelings, plans, and/or strategies related to career problem-solving and decision-making” (Sampson et al., 2009, p. 91). Cognitive therapy theoretical concepts specify that dysfunctional cognitions have a detrimental impact on behavior and emotions (Beck, 1976; Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). Cognitive information process (CIP) theory explains the role of cognitions in career decision-making. This theory is meant to enhance the link between theory and practice in the delivery of cost-effective career services for adolescents, college students and adults (Peterson et al., 1991; 1996; Sampson et al., 2009). Its goal is to help individuals make appropriate career choices and learn improved problem-solving and decision-making skills needed for future choices (Sampson et al., 2009).

There are a few definitions that need to be understood in order to fully comprehend and utilize CIP. Problem is synonymous with career problem and is defined as a “gap between an existing and a desired state of affairs” (Sampson et al., 2009, p. 4). The gap may be between an existing state (e.g., knowing I need to make a choice) and an ideal state (e.g., knowing I made a good choice). Problem-solving is a “series of thought processes in which information about a problem is used to arrive at a plan of action necessary to remove the gap between an existing and a desired state of affairs” (Sampson et al., 2009, p. 5). Decision-making includes “problem-solving, along with the cognitive and affective processes needed to develop a plan for implementing the solution and taking risks involved in following through to complete the plan” (Sampson et al., 2009, p. 6).

CIP theory assumes that effective career problem-solving and decision-making requires the effective processing of information in four domains: (1) self-knowledge, (2) occupational knowledge, (3) decision-making skills, and (4) executive processing (Sampson et al., 2009). Self-knowledge includes individuals’ perceptions of their values, interests, skills, and employment preferences. Occupational knowledge includes knowledge of individual occupations and having a schema for how the world of work is organized. Decision-making skills are the generic information processing skills that individuals use to solve problems and make decisions. Executive processing includes meta-cognitions, which control the selection and sequencing of cognitive strategies used to solve a career problem through self-talk, self-awareness, and control and monitoring.

Social Support and Career Planning

There is limited research examining social support and career planning. Career planning is related to career thoughts by the appraisal or cognitive processing that occurs during career decision-making. Based on limited scientific findings, social support has been found to have a positive and important effect on career planning. In a study on unemployed individuals, Blustein (1992) found that instrumental support in the form of constructive advice and resources help to better appraise career-related information and adapt to the novel circumstances. It also was found that social support can positively affect the recipient’s experience and is an important determinant of career activities such as researching career options or seeking assistance from a career advisor.

Similar findings indicate that along with instrumental support, emotional social support which is characterized by empathy, caring, love, and trust from families is especially important during stressful transitions such as job loss (DeFrank & Ivancevich, 1986). Regarding students and career planning, Quimby and O’Brien (2004) found that perceptions of robust social support resulted in feelings of confidence both in managing the responsibilities associated with being a student and pursuing tasks related to advancing vocational development. Though it is evident that social support is an important factor in the career planning process, additional research examining this construct and its place in career development is needed.

Given the reviewed literature and current gap, the purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among satisfaction with five types of social support and negative career thoughts in collegiate athletes and non-athletes.

Method

Participants

Non-student-athletes and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I student-athletes from the same university were recruited for this study. Complete data were obtained from 272 participants (154 non-athletes and 118 athletes). One hundred forty-six (53.7%) of the participants were male and 126 (46.3%) were female. The race/ethnicity breakdown was as follows: Caucasian (n = 162, 59.6%), African American (n = 74, 27.2%), Hispanic (n = 15, 5.5%), Asian American (n = 1, 0.4%), other (n = 12, 4.4%), and more than one apply (n = 8, 2.9%). Forty-three (15.8%) of the participants were freshman, 65 (23.9%) sophomores, 94 (34.6%) juniors and 70 (25.7%) seniors. Of the athletes, the varsity sport breakdown was as follows: baseball (n = 13, 11.0%), basketball (n = 14, 11.9%), football (n = 37, 31.4%), golf (n = 5, 4.2%), soccer (n = 7, 5.9%), softball (n = 8, 6.8%), swimming & diving (n = 8, 6.8%), tennis (n = 3, 2.5%), track & field (n = 18, 15.3%), and volleyball (n = 4, 3.4%). One (0.8%) athlete did not indicate involvement in a particular sport.

All participants were recruited from a single large university located in the southeastern region of the United States. They were above 18 years of age, and participants comprised of a volunteer, convenient sample obtained by contacting athletic administrators and professors.

Instrumentation

Demographic Information Survey. The survey contained information about participants’ college major, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and academic year.

Social Support Inventory-Subjective Satisfaction (SSI-SS). The SSI-SS (Brown et al., 1987) consisted of 39 self-report items assessing one’s satisfaction with five types of social support: (a) acceptance and belonging, (b) appraisal and coping assistance, (c) behavioral and cognitive guidance, (d) tangible assistance and material aid, and (e) modeling. Participants responded to these items on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 7 (very satisfied) to indicate their satisfaction with the support they have received. A total score is obtained by summing all of the items. The overall score of the SSI-SS ranges from 39 to 273. The acceptance-belonging subscale score ranges from 9 to 63, and the appraisal-coping assistance subscale score ranges from 9 to 63. The behavioral-cognitive guidance subscale score ranges from 6 to 42. The tangible assistance-material aid subscale score ranges from 5 to 35, and the modeling subscale score ranges from 4 to 28. The total score and the scores of each of the five factors will be assessed in this study.

Alpha coefficients for the five factors are .93 for acceptance-belonging, .88 for appraisal-coping assistance, .81 for behavioral-cognitive guidance, .78 for tangible assistance-material aid, and .83 for modeling (Brown et al., 1987). The overall alpha coefficient is .96. The SSI-SS has been normed on college-age and adult populations.

Career Thoughts Inventory (CTI). The CTI (Sampson, Peterson, Lenz, Reardon, & Saunders, 1996a) is a 48-item self-administered, objectively scored measure of dysfunctional thinking in career problem-solving and decision-making. Participants respond to items on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree) to indicate how much they agree with the negative career statement given. The CTI scores consist of one total score as well as scores on three subscales. The CTI is a CIP-based assessment and intervention resource intended to assess the quality of career decisions made by adults and college and high school students. It measures the eight content dimensions of CIP theory that include: (1) self-knowledge, (2) occupational knowledge, (3) communication, (4) analysis, (5) synthesis, (6) valuing, (7) execution, and (8) executive processing (Peterson et al., 1991; 1996).

The CTI has been normed on high school, college, and adult populations (Sampson et al., 1996b). Reliability evidence for the CTI total score includes internal consistency alpha coefficients ranging from .93 to .97 and a test-retest coefficient of .77. The readability of the CTI was calculated to be at a 6.4 grade level.

Decision-making confusion (DMC) is one subscale on the CTI and it refers to the inability to initiate or sustain the decision-making process as a result of disabling emotions and/or a lack of understanding about the decision-making process itself. Commitment anxiety (CA) is another subscale on the CTI and it reflects the inability to make a commitment to a specific career choice, accompanied by generalized anxiety about the outcome of the decision-making process. This anxiety perpetuates indecision. External conflict (EC) is the final subscale and it reflects the inability to balance the importance of one’s own self-perceptions with the importance of input from significant others, resulting in a reluctance to assume responsibility for decision-making.

Procedure

Athletic academic advisers and professors at a large southeastern university were contacted via e-mail using a script. The principal investigator met with the participants whenever they were available to be administered the battery of tests, during their tutoring sessions in the athletic academic support office or in their classes. During the meeting, the participants were oriented to the purpose of the study. They were asked to sign an informed consent form, and told that their participation in the study was completely voluntary and that they may drop out at any time. The researcher administered the questionnaires beginning with the Demographic Information Survey, then the Social Support Inventory, and finally the Career Thoughts Inventory. Tests were then collected and a randomly assigned number identified each battery of tests.

Results

Preliminary analyses were performed to obtain internal consistency coefficients of the measures and descriptive statistics. The alpha coefficients observed in this study for each Social Support Inventory-Subjective Satisfaction (SSI-SS) subscale and total score were: acceptance-belonging (α = .79), appraisal-coping assistance (α = .83), behavioral-cognitive guidance (α = .81), tangible assistance-material aid (α = .70), modeling (α = .74), and total score (α = .90). For the Career Thoughts Inventory (CTI) subscales and total score, the alpha coefficients observed were as follows: decision-making confusion (α = .86), commitment anxiety (α = .85), external conflict (α = .82), and total score (α = .89). The alpha coefficient values indicated adequate internal consistency.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

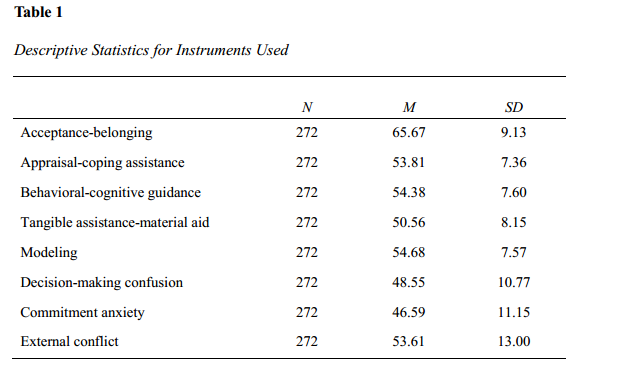

Descriptive statistics for the SSI-SS subscales: acceptance-belonging, appraisal-coping assistance, behavioral-cognitive guidance, tangible assistance-material aid, and modeling; and CTI subscales: decision-making confusion, commitment anxiety, and external conflict are presented in Table 1. Overall, participants averaged a T-score within the average range for the majority of the subscales with the social support subscale of acceptance-belonging having the highest mean (M = 65.67, SD = 9.13).

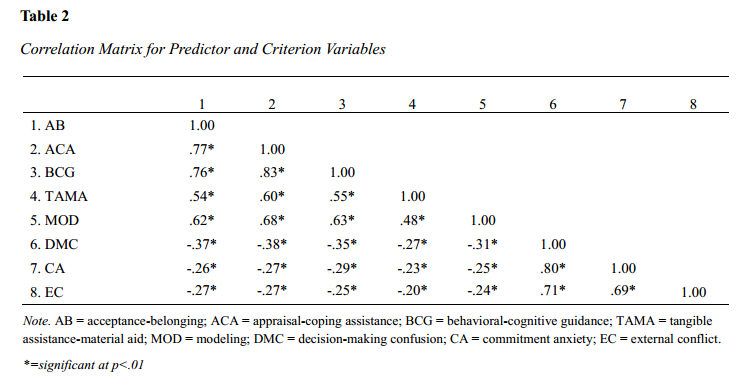

The bivariate correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Without controlling for any variables, the social support types of acceptance-belonging and appraisal-coping assistance had the strongest relationships with decision-making confusion (r = -.37 and -.38, respectively). The bivariate correlations also indicated that all social support types had significant relationships with decision-making confusion, commitment anxiety, and external conflict. When all variables were controlled, there were no significant relationships between any of the five types of social support and career thoughts.

Regression

Three hierarchical regression analyses were performed with the five predictor variables and three criterion variables. All regression models were significant. It is suggested that the variance shared among the predictors is what accounts for the significant models. None of the social support types were found to have significant unique relationships with any of the career thoughts variables.

Structural Equation Modeling

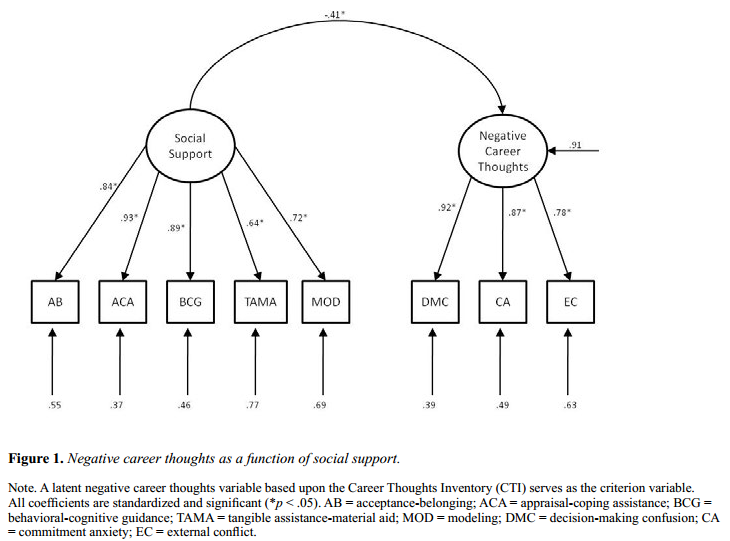

Conceptual models of the posited relationship between social support and career thoughts, as seen in Figure 1, were tested using SEM procedures. The model shows that the five social support types were used as indicators for a social support latent factor and the three subscales of the CTI were used as indicators for a negative career thoughts latent factor.

The distributional properties of the study variables in the model were examined to select the appropriate model estimator. No substantial problems were evident in either univariate skewness (M = -.39; range from -.83 to .29) or kurtosis (M = .23; range from -.36 to .90) in the eight variables used in the SEM analysis. Mild multivariate kurtosis was indicated with a Mardia’s normalized estimate equating to 10.15. For the model, the model-reproduced and observed covariance matrices did not differ, χ² = 18.79, df = 19, p = .47. Desirable CFI and IFI indexes (1.00 for both) were observed. The satisfactory distribution of the residuals was substantiated by the observed standardized RMSR (.02). Figure 1 presents the standardized path coefficients and residuals for the SEM.

In the model, the social support latent variable accounted for 17% of the variance in the negative career thoughts latent variable. The social support latent variable accounted for the majority of the variance in the subscales of acceptance-belonging (R² = .70), appraisal-coping assistance (R² = .87), behavioral-cognitive guidance (R² = .79), tangible assistance-material aid (R² = .41), and modeling (R² = .52). The negative career thoughts latent variable accounted for the majority of the variance in the subscales of decision-making confusion (R² = .85), commitment anxiety (R² = .76), and external conflict (R² = .61). In summary, these analyses make it apparent that social support is associated with career thoughts as observed by the significant correlation between the latent variable of social support as measured by the SSI-SS and the latent variable of negative career thoughts as measured by the CTI.

Z-Score Analyses

Z-score analyses were performed to determine any significant differences between sample populations based on athletic status, gender, and academic class status in the relationship between social support and career thoughts. Regarding athletic status, a significant difference (p < .01) was found between athletes and non-athletes in the relationship between the social support type of appraisal-coping assistance and the career thoughts variable of commitment anxiety (z = 1.95), with that relationship being stronger in the non-athlete population. Also regarding athletic status, a significant difference (p < .01) was found between athletes and non-athletes in the relationship between the social support type of modeling and the career thoughts’ variable commitment anxiety (z = 2.02), with that relationship also being stronger in the non-athlete population.

No significant differences were found between the male and female genders in the relationship between social support and career thoughts. Regarding academic class status, upperclassmen had a significantly stronger relationship (p < .01) between total social support and the social support types of appraisal-coping assistance and behavioral-cognitive guidance and the career thoughts’ variable commitment anxiety (z = 2.08; 2.30; 2.15; respectively). In summary, several significant differences were found between sample populations.

Discussion

Results revealed that social support accounts for about 17% of the variance in career thoughts. This suggests that social support has a moderate relationship with career thoughts. These results also support the literature on the positive effect of social support on the career planning process (Blustein, 1992; DeFrank & Ivancevich, 1986; Quimby & O’Brien, 2004).

The person environment fit model (Dawis, 2002) provided an important framework in the present study as satisfaction with social support was found to have a moderate relationship with career thoughts. However, the strong relationships between the five types of social support made it difficult to examine the unique relationship of each to career thoughts. The results infer that the five types of social support identified by Brown et al. (1988) may not be independent.

The bivariate correlations indicated that all social support types had significant relationships with the career thoughts variables. When all variables were controlled, there were no significant relationships between any of the five types of social support and career thoughts. Instrumental support, as defined by Blustein (1992) and DeFrank and Ivancevich (1986), relates to Brown et al.’s (1988) social support types of behavioral-cognitive guidance and tangible assistance-material aid. The results of the present study show that both social support types had moderate relationships with career thoughts. Emotional support, as defined by DeFrank and Ivancevich (1986), relates to Brown et al.’s (1988) social support type of acceptance-belonging. This type of social support also was found to have a negative, moderate relationship with career thoughts. These results reinforce those found in Blustein (1992) and DeFrank and Ivancevich (1986) in that social support is an important component in the career planning process.

It was found that the sociocultural context in which the social support is provided has an effect on the perception of the social support by the recipient. The significant difference between the athlete and non-athlete and upperclassmen and underclassmen populations in the present study may be due to their different sociocultural contexts. The results of this study suggest that the appraisal-coping assistance and modeling social support types may be better provided to the non-student-athlete population who are experiencing anxiety related to the career decision-making process. In addition, the appraisal-coping assistance and behavioral-cognitive guidance social support types may be more influential in reducing career decision-making anxiety if provided to upperclassmen.

The present study adds to the literature by studying the different types of social support that make up the social support construct. The study also adds to the literature by examining the relationship between social support and career thoughts, which has not been studied previously. In addition, the examination of the differences in the social support/career thoughts relationship between groups in the sample population (i.e., athlete/non-athlete, male/female, upperclassmen/underclassmen) adds an important dimension to the available literature.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is with the convenience sampling because the extent to which the students were representative of the overall population of college students is unknown. The participants were not obtained by random sampling, but rather obtained because of availability. Therefore, it is difficult to know the extent to which the results of this study are generalizable beyond this sample.

Implications

The present study investigated the relationship between the five types of social support and the three constructs that comprise career thoughts. Although none of the types of social support were found to have a uniquely significant relationship with career thoughts, there was in fact a moderate relationship between the overall construct of social support and career thoughts.

This study has important implications for practice. Coaches, athletic administrators, career counselors, mental health counselors, professors and other post-secondary administrators now have a better idea of what types of social support are deemed as having the greatest impact on how college students view their post-collegiate careers. Current literature only focuses on the overall social support construct and its positive effects, but the present study allows for the differentiation of the social support types, which provides additional information for practical purposes (Bianco & Eklund, 2001; Taylor & Ogilvie, 2001). Hopefully, this will increase the likelihood of college students actually receiving these types of social support based on their subgroup (i.e., athlete/non-athlete and upperclassmen/underclassmen). Also, college students now have the opportunity to be aware of what types of social support will lead to less negative career thinking.

Regarding implications for research, it is evident that additional research needs to be done to gain a better understanding of the relationship between social support and career thoughts in college students. This is the first study that has examined these two constructs and more research is necessary. More and better social support measures need to be introduced into the field that better examine social support and its different types. Also, this study supports the literature on the importance of career thoughts during the career planning process (Peterson et al., 1991, 1996; Sampson et al., 1996b, 2009). An improved foundation is now available for additional research on the cognitive aspects of career planning and how it relates to social entities.

Future Directions

The present study provides an important foundation for future research. Since it is the first study to examine social support and career thoughts directly, additional examinations of these constructs are necessary per the practical and research implications previously stated. Other variables such as career maturity, self-efficacy, motivation, and personality characteristics should be included in future research to try and account for the remaining variance in career thoughts. Also, the negative aspects of social support, such as peer or parental pressures, should be examined.

Since the present study only examines college students, other populations should be included in future research. In addition, it may be interesting to examine the differences between college students at private and public institutions. Other populations also can be researched, including adults on the verge of retirement or high school seniors trying to decide what to do after graduation.

It may be important to study the phases of the career development process and if different types of social support affect the various phases differently. For example, participating in volunteer activities to boost one’s resume is unlike job searching. In addition, performing qualitative research may add to the information provided from quantitative research.

It is important to note that the strong correlations between each type of social support may infer a poor measure of the different types of social support. A confirmatory factor analysis would be useful in determining if the Social Support Inventory is in fact an adequate measure of social support and its subtypes. There may be better inventories available that measure the different types of social support, and they should be used to determine any differences between social support measures. It is important to note the complexity of the social support construct and that other instruments should be identified that better measure the complex aspects of the construct. Overall, the current study provides an adequate foundation for future practice and research. The relationship between social support and career thoughts is important to understand in order to better help college students and possibly other populations prepare for whatever career transition they may face.

References

Beck, A. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Beck, A., Emery, G., & Greenberg, R. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Beck, A., Rush, A., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bianco, T. (2001). Social support and the recovery from sport injury: Elite skiers share their experiences. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 72, 376–388.

Bianco, T., & Eklund, R.C. (2001). Conceptual considerations for social support research in sport and exercise settings: The case of sport injury. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 23, 85–107.

Blustein, D. (1992). Applying current theory and research in career exploration to practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 41, 174–184.

Brown, S., Brady, T., Lent, R., Wolfert, J., & Hall, S. (1987). Perceived social support among college students: Three studies of the psychometric characteristics and counseling uses of the social support inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 337–354.

Brown, S., Alpert, D., Lent, R., Hunt, G., & Brady, T. (1988). Perceived social support among college students: Factor structure of the social support inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35, 472–478.

Dawis, R. (2002). Person-environment-correspondence theory. In D. Brown & Associates (Eds.). Career choice and development (pp. 427–464). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

DeFrank, R., & Ivancevich, J. (1986). Job loss: An individual level review and model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 28, 1–20.

Peterson, G., Sampson, J., Jr., & Reardon, R. (1991). Career development and services: A cognitive approach. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Peterson, G., Sampson, J., Jr., Reardon, R., & Lenz, J. (1996). Becoming career problem solvers and decision makers: A cognitive information processing approach. In D. Brown & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (3rd. Ed.) (pp. 423–475). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Quimby, J., & O’Brien, K. (2004). Predictors of student and career decision-making self-efficacy among nontraditional college women. The Career Development Quarterly, 52, 323–339.

Sampson, J., Jr., Peterson, G., Lenz, J., Reardon, R., & Saunders, D. (1996a). Career thoughts inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Sampson, J., Jr., Peterson, G., Lenz, J., Reardon, R., & Saunders, D. (1996b). Negative thinking and career choice. In R. Feller & G. Walz (Eds.). Optimizing life transitions in turbulent times: Exploring work, learning and careers (pp. 323–330). Greensboro, NC: University of North Carolina at Greensboro, ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Student Services.

Sampson, J., Jr., Reardon, R., Peterson, G., & Lenz, J. (2009). Career counseling and services: A cognitive information processing approach. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Taylor, J., & Ogilvie, B. (2001). Career termination among athletes. In R. N. Singer, H. A. Hausenblas, & C. M. Janelle (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (2nd ed., pp. 672–691). New York, NY: Wiley.

Stefanie Rodriguez is an Adjunct Professor at the University of South Florida. Correspondence can be addressed to Stefanie Rodriguez, University of South Florida, 4202 E Fowler Ave, Tampa, FL 33620, stefanie.rodriguez@live.com.