Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Wesley B. Webber, W. Leigh Atherton, Kelli S. Russell, Hilary J. Flint, Stephen J. Leierer

The COVID-19 pandemic and efforts to manage it have affected mental health around the world. Although early research on the COVID-19 pandemic showed a general decline in mental health after the pandemic began, mental health in later stages of the pandemic might be improving alongside other changes (e.g., availability of vaccines, return to in-person activities). The present study utilized data from a mental health service intervention for individuals at a southeastern university who were exposed to COVID-19 following the university’s return to in-person operations. This study tested whether time period (August–September 2021 vs. January–February 2022) predicted individuals’ likelihood of being mild or above in depression and anxiety ratings. Results showed that individuals were more likely to be mild or above in both depression and anxiety ratings during August–September of 2021 than January–February of 2022. Suggestions for future research and implications for professional counselors are discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, depression, anxiety, university

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19), first detected in 2019, spread globally at a rapid pace, with the first confirmed case in the United States occurring on January 20, 2020, in the state of Washington (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023). By April 2020, the United States had the most reported deaths in the world due to COVID-19. It was not until December of 2020 that the first round of vaccines, authorized under emergency use authorization, was made available (Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2021). As of October 2022 in the United States, a total of 97,063,357 cases of COVID-19 had been reported, from which there were 1,065,152 COVID-19–related deaths (CDC, 2023). A reported 111,367,843 individuals aged 5 and above in the United States had received their first booster dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of October 2022 (CDC, 2023). Previous research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic and efforts to manage it (e.g., lockdowns, quarantine, isolation) had negative effects on mental health in the United States and internationally (Huckins et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020; Son et al., 2020). Based on the extended duration of the pandemic and changes that have occurred during it (e.g., vaccine availability, lessening of initial social restrictions), more recent research has investigated possible changes in mental health in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fioravanti et al., 2022; McLeish et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). The present study adds to this literature by exploring whether psychosocial symptomatology (i.e., depression and anxiety) at a university in the Southeastern United States differed in individuals exposed to COVID-19 during August–September 2021 as compared to individuals exposed to COVID-19 during January–February 2022 (following the university’s return to on-campus operations in August 2021).

Challenges to Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, conceptual and empirical research has focused on ways in which the pandemic and associated stressors might impact mental health (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2020; Marroquín et al., 2020; Şimşir et al., 2022). Implementation of lockdowns to deter spread of the virus led to concerns that social isolation might have severe impacts on mental health (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2020). This hypothesis was empirically supported, as stay-at-home orders and individuals’ reported levels of social distancing were positively associated with depression and anxiety (Marroquín et al., 2020). Individuals’ views on the COVID-19 pandemic evolved quickly at the outset of the pandemic, and perceptions of risk were shown to increase during the pandemic’s first week in the United States (Wise et al., 2020). Growing awareness of the dangers of the virus likely had deleterious effects on mental health; Şimşir et al. (2022) found through a meta-analysis that fear of COVID-19 was associated with a variety of mental health problems. Mental health was also negatively affected by stigmatization associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, as was the case for those exposed to COVID-19 while at their place of work (Schubert et al., 2021). Such stigmatization associated with COVID-19 exposure was found to increase risk for depression and anxiety (Schubert et al., 2021).

The lockdowns and social distancing measures that accompanied early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic also resulted in changes to routines that likely impacted mental health. For some individuals facing lockdowns or other disruptions to typical routines, reductions in physical activity occurred. Individuals who reported greater impact of COVID-19 on their level of physical activity showed greater symptoms of depression and anxiety (Silva et al., 2022). Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, based on people’s increased time spent at home and their concerns about COVID-19 developments, some people increased their media usage (e.g., news outlets, social media). Such increases in media usage were associated with decreases in mental health (Meyer et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic had less significant impact on mental health for those with greater tolerance of uncertainty (Rettie & Daniels, 2021) and psychological flexibility (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020). Thus, some individuals were uniquely suited to face the many changes and stressors brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

One population that previous research has identified as being especially at risk for negative mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic is college students (Xiong et al., 2020). For college students, the COVID-19 pandemic occurred alongside other stressors known to be typical for this population such as adjusting to leaving home, navigating new peer groups, and making career decisions (Beiter et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019). Thus, for many college students, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted a period of life already filled with many transitions. For example, shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic began, many college students were forced to leave their dormitories and peers as universities transitioned to online delivery of classes (Copeland et al., 2021). Xiong et al. (2020) found through a systematic review that college students were especially vulnerable to negative mental health outcomes at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to others in the general population. In the United States, college students’ reported degree of life disruption due to the COVID-19 pandemic was positively associated with depression at the conclusion of the spring 2020 semester (Stamatis et al., 2022). During fall 2020, COVID-19 concerns and previous COVID-19 infection were each found to be associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety among U.S. college students (Oh et al., 2021). Overall, previous research has supported the notion that changes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic had general negative effects on mental health in the general population and in college students specifically.

Changes in Psychosocial Symptomatology Across the COVID-19 Pandemic

Although research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic introduced unprecedented challenges and stressors that were associated with mental health problems, another important direction for research has been to characterize overall changes in psychosocial symptomatology as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed. Such research is important given that individuals might psychologically adapt to constant COVID-19 stressors or might benefit from changes that have occurred as the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed (e.g., vaccine availability, lessening of societal restrictions). Initial longitudinal studies comparing individuals’ symptomatology before the COVID-19 pandemic and after its beginning showed that mental health deteriorated after the COVID-19 pandemic began (Elmer et al., 2020; Huckins et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020). Prati and Mancini (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of 28 studies that used longitudinal or natural experimental designs and found that depression and anxiety showed small but statistically significant increases after implementation of the initial lockdowns in response to COVID-19. The various changes to ways of life associated with the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to result in a general deterioration in mental health.

Previous research has also explored possible changes in mental health beyond those that were observed in the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. In support of the notion that individuals adapted to changes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, Fancourt et al. (2021) found that anxiety and depression decreased across the initial lockdown period in the United Kingdom. In contrast, Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. (2020) found that levels of depression and anxiety were higher 3 weeks into the initial lockdown period in Spain as compared to the beginning of the lockdown. Fioravanti et al. (2022) assessed psychological symptoms longitudinally in an Italian sample at three time points—the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and first lockdown (March 2020), the end of the first lockdown phase (May 2020), and during a second wave of COVID-19 with increased societal restrictions (November 2020). Their findings pointed to possible influences of COVID-19 waves and societal restrictions on specific psychosocial symptoms. Specifically, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder all decreased at the end of the first lockdown phase (Fioravanti et al., 2022). However, all symptoms besides obsessive-compulsive disorder significantly increased from the end of the first lockdown phase to the second wave of COVID-19 (Fioravanti et al., 2022).

Recent research on mental health among college students in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic has also focused on possible mental health changes over time (McLeish et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). Tang et al. (2022) reported reductions in anxiety and depression in a longitudinal study of university students in the United Kingdom between a first time point (July–September 2020, after the end of lockdown) and a second time point (January–March 2021, when vaccinations were becoming available). In contrast, McLeish et al. (2022) found through a repeated cross-sectional study that depression and anxiety among students at a specific university increased from spring 2020 to fall 2020, with the increases being maintained in spring 2021. The authors noted that vaccines were not widely available at the university until the end of spring 2021 (McLeish et al., 2022). Thus, recent studies have found mixed results as to whether psychosocial symptomatology improved over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. These discrepancies may be due to contextual differences between studies (e.g., differences in data collection time periods, availability of vaccines, or levels of COVID-19 restrictions being implemented during data collection).

The Present Study

The present study was conducted based on the need for continued research on mental health across the evolving COVID-19 pandemic and based on previous conflicting findings on possible mental health changes in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given previous research showing detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population and in college students, the present study utilized data from a university population. Specifically, an archival dataset was used in the present study to examine data collected during 2021–2022 at a university in the Southeastern United States and to test whether time period would predict severity of depression and anxiety symptoms. Individuals in the study had been exposed to COVID-19 between August–September 2021 or between January–February 2022 and had requested a mental health contact during university-conducted contact tracing. These two time periods corresponded to surges in COVID-19 cases at the university due to the delta and omicron COVID-19 variants, respectively. August–September 2021 also coincided with a return to on-campus operations at the university and therefore captured psychosocial symptomatology at the beginning of a significant transition in the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., a return to organized in-person activities on a college campus during the evolving pandemic). This study was designed to answer the following research questions:

- Among those requesting mental health contact after COVID-19 exposure, was the likelihood of having at least mild depression symptoms different for those whose contact occurred between August–September 2021 as compared to those whose contact occurred between January–February 2022?

- Among those requesting mental health contact after COVID-19 exposure, was the likelihood of having at least mild anxiety symptoms different for those whose contact occurred between August–September 2021 as compared to those whose contact occurred between January–February 2022?

Method

Design

A retrospective research design was used to analyze the possible effect of time period on severity of depression and anxiety symptoms among members of a university population who had been exposed to COVID-19 and requested a mental health check-in. The study used a de-identified dataset obtained from the service providers who completed the mental health check-in. We confirmed through consultation with the IRB that the use of archival, de-identified data does not necessitate IRB review.

COVID-19 Mental Health Check-In Dataset

The archival, de-identified dataset used in the present study was compiled as part of a mental health service occurring between February 2021 and February 2022. Participants in the dataset had tested positive for COVID-19 or been exposed to COVID-19 without a positive test. During university-conducted contact tracing, they were offered and elected to receive a subsequent mental health check-in. Individuals who were contact traced and thereby offered a mental health check-in had become known to contact tracers through one of two routes: (a) they reported their own COVID-19 diagnosis or exposure through a self-reporting mechanism as instructed by the university, or (b) they were reported by another individual as having been diagnosed with or exposed to COVID-19. The dataset used in this study included data collected during the mental health check-ins for those who elected to receive them. This data was collected over the phone and documented in RedCap (a secure web browser–based survey protocol designed for clinical research) at the time of the phone call or within 24 hours. The dataset consisted of data for 211 individuals’ check-ins. For each check-in, the dataset included participants’ demographic information, screening data (for depression, anxiety, and trauma), identified needs of the participant, resources shared with the participant, and the date of data entry.

The present study focused on check-in data for all individuals from the COVID-19 Mental Health Check-in Dataset whose check-in had occurred during one of the two time periods of focus—August–September 2021 or January–February 2022. These two time periods corresponded to surges in COVID-19 cases at the university associated with the delta and omicron COVID-19 variants, respectively. The 149 individuals who checked in during these 4 months represented 70.62% of the total number of check-ins over the 12-month dataset (N = 211), reflecting the surges in COVID-19 cases during these two periods. Of the 149 individuals in the present study, 96 (64.43%) received their check-in during August–September 2021, and 53 (35.57%) received their check-in during January–February 2022. The selection of these two time periods from the larger dataset allowed for comparison of psychosocial symptomatology during comparable levels of COVID-19 infection (i.e., surges associated with two subsequent COVID-19 variants) at comparable points in subsequent academic semesters (i.e., the first 2 months of the fall 2021 and spring 2022 semesters). The present study used only the screening data for depression and anxiety, as the scales for each of these constructs showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > .80).

Participants

The sample in the present study consisted of 149 individuals. The selected individuals’ ages ranged from 17 to 52 (M = 22.21, SD = 7.43). With regard to gender, 67.11% identified as female, 32.21% as male, and 0.67% as non-binary. The reported races of individuals in the study were as follows: 60.4% White, 20.13% African American, 6.71% Hispanic, 3.36% Other, 2.68% Two or more races, 1.34% Middle Eastern, 1.34% Native American, and 0.67% Asian. Some participants preferred not to indicate their race (3.36%). In responding to a question about their ethnicity, 87.25% of individuals identified as not Latinx, 9.40% identified as Latinx, and 3.36% preferred not to answer. With regard to academic level/job title, 32.89% were freshmen, 20.13% were sophomores, 14.09% were juniors, 15.44% were seniors, 7.38% were graduate students, 8.05% were faculty/staff, and 2.01% preferred not to answer. Regarding employment, 53.69% were not employed (including students), 30.20% were employed part-time, 12.75% were employed full-time, and 3.36% preferred not to answer. The relationship statuses of individuals were reported as the following: 87.92% single (never married), 4.7% married, 2.01% single but cohabitating with a significant other, 1.34% in a domestic partnership or civil union, 1.34% separated, 0.67% divorced, and 2.01% preferred not to answer. Table 1 summarizes demographic responses within each of the two time periods and for the full sample.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants responded to seven demographic questions (age, gender, race, ethnicity, academic year/job title, current employment status, and relationship status). They were informed that this information was optional and that they could choose not to answer particular questions.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

|

Demographic

Characteristic |

|

| August–September 2021 |

January–February 2022 |

Full Sample |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

69 |

71.88 |

31 |

58.49 |

100 |

67.11 |

| Male |

27 |

28.13 |

21 |

39.62 |

48 |

32.21 |

| Non-binary |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.89 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| White |

56 |

58.33 |

34 |

64.15 |

90 |

60.40 |

| African American |

23 |

23.96 |

7 |

13.21 |

30 |

20.13 |

| Hispanic |

8 |

8.33 |

2 |

3.77 |

10 |

6.71 |

| Other race |

1 |

1.04 |

4 |

7.55 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Two or more races |

4 |

4.17 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

2.68 |

| Middle Eastern |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Native American |

1 |

1.04 |

1 |

1.89 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Asian |

1 |

1.04 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

5 |

9.43 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not Latinx |

82 |

85.42 |

48 |

90.57 |

130 |

87.25 |

| Latinx |

12 |

12.50 |

2 |

3.77 |

14 |

9.40 |

| Prefer not to answer |

2 |

2.08 |

3 |

5.66 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Academic Year / Job Title |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Freshman |

38 |

39.58 |

11 |

20.75 |

49 |

32.89 |

| Sophomore |

18 |

18.75 |

12 |

22.64 |

30 |

20.13 |

| Junior |

15 |

15.63 |

6 |

11.32 |

21 |

14.09 |

| Senior |

15 |

15.63 |

8 |

15.09 |

23 |

15.44 |

| Graduate Student |

6 |

6.25 |

5 |

9.43 |

11 |

7.38 |

| Faculty/Staff |

4 |

4.17 |

8 |

15.09 |

12 |

8.05 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5.66 |

3 |

2.01 |

| Employment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not Employed (including student) |

62 |

64.58 |

18 |

33.96 |

80 |

53.69 |

| Employed Part-Time |

26 |

27.08 |

19 |

35.85 |

45 |

30.20 |

| Employed Full-Time |

8 |

8.33 |

11 |

20.75 |

19 |

12.75 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

5 |

9.43 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Relationship Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single, never married |

87 |

90.63 |

44 |

83.02 |

131 |

87.92 |

| Married |

3 |

3.13 |

4 |

7.55 |

7 |

4.70 |

| Single, but cohabitating with a

significant other |

2 |

2.08 |

1 |

1.89 |

3 |

2.01 |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Separated |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Divorced |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.89 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5.66 |

3 |

2.01 |

| Note. Average age was 21.51 (SD = 6.98) in August–September 2021 group, 23.49 (SD = 8.11) in January–February 2022 group, and 22.21 (SD = 7.43) in the full sample. |

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of depression symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The PHQ-9 has been validated for screening for depression in the general population (Kroenke et al., 2001; Martin et al., 2006). The questionnaire measures frequency of symptoms such as “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” and “little interest or pleasure in doing things.” The PHQ-9 uses a 4-point Likert scale to measure frequency of symptoms over the past 2 weeks with the response options of not at all, several days, more than half the days, and nearly every day. Scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 are assigned to each of the four response categories, and a PHQ-9 total score is derived by adding the scores for each of the nine PHQ-9 items. Minimal depression is indicated by PHQ-9 total scores of 0–4, mild depression by scores of 5–9, moderate depression by scores of 10–14, moderately severe depression by scores of 15–19, and severe depression by scores of 20–27. Question 9 on the PHQ-9 is a single screening question assessing suicide risk. Interviewers were trained in appropriate protocol in the event of a positive screen for this question. Cronbach’s alpha for the PHQ-9 in the present study was .86.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7)

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) is a 7-item self-report anxiety questionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The GAD-7 has demonstrated reliability and validity as a measure of anxiety in the general population (Löwe et al., 2008). The questionnaire measures symptoms such as “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge,” and “not being able to stop or control worrying.” The format of the GAD-7 is similar to the PHQ-9, using a 4-point Likert scale to measure frequency of symptoms over the past 2 weeks with response options of not at all, several days, more than half the days, and nearly every day. GAD-7 scores are calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 for response categories and then adding the scores from the 7 items to derive a total score ranging from 0 to 21. Minimal anxiety is indicated by total scores of 0–4, mild anxiety by scores of 5–9, moderate anxiety by scores of 10–14, and severe anxiety by scores of 15– 21. Cronbach’s alpha for the GAD-7 in the present study was .86.

Analytic Strategy

Total scores for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were found to be positively skewed for both groups of participants. Binary logistic regression was therefore an appropriate method of analysis for this dataset, as binary logistic regression does not require normality of dependent variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). For two separate binary logistic regression models, individuals were classified as being either minimal or mild or above in depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) to create binary outcome variables. This choice of cutoff allowed each model (with time period as predictor) to satisfy the recommendation of Peduzzi et al. (1996) that there be at least 10 cases per outcome per predictor in binary logistic regression.

Prior to performing these intended primary analyses to answer the research questions, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether adding control variables to the logistic regression models was warranted. Chi-square tests of independence, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests, Fisher’s Exact tests, and an independent samples t-test were used to test for possible differences between the two time periods in individuals’ responses to demographic questions. In cases in which responses to demographic questions were shown to be significantly different across the two groups, appropriate tests were used to determine whether the demographic responses in question were associated with either of the two intended dependent variables.

Following the preliminary analyses, the intended two binary logistic regressions were conducted to answer the research questions. In the first binary logistic regression, time period was the predictor

(1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) and PHQ-9 depression category was the outcome (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal). In the second logistic regression, time period was the predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) and GAD-7 anxiety category was the outcome (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal). All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 28.

Results

Preliminary Demographic Analyses

Prior to the primary analyses, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether the two groups differed in their responses to demographic questions. Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests and an independent samples t-test were used to test for differences between groups in their responses to the seven demographic questions. Two of the seven tests were statistically significant at Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. Specifically, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests found significant differences between time periods on the race (p = .004) and employment (p < .001) demographic variables.

Based on the above significant results for the race and employment variables across the time periods, 2 x 2 tests were conducted to test for differences between specific race responses and specific employment responses across the two time periods. For these 2 x 2 tests, a chi-square test of independence was used when all expected cell counts were 5 or greater and Fisher’s Exact test was used when any expected cell counts were less than 5. To follow up the significant result for race, 2 x 2 tests were conducted for all pairs of race responses in which 2 x 2 tests were possible (i.e., in which there was at least one observation for each of the two race responses at both time periods). These follow-up 2 x 2 tests of responses to the race question across time periods found no statistically significant differences between pairs of race responses across time periods using Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. Follow-up 2 x 2 tests comparing all pairs of responses to the employment question across time periods found two statistically significant differences using Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. A chi-square test of independence showed that individuals were more likely to be employed full-time during January–February 2022 than August–September 2021 as compared to those not employed (including students), X2 (1, N = 99) = 9.29, p = .002. Fisher’s Exact test showed that individuals were more likely to indicate “prefer not to answer” during January–February 2022 than during August–September 2021 as compared to those indicating “not employed (including students),” p = .001.

The statistically significant tests for race and employment across time periods were followed up with additional tests to determine if depression or anxiety category (minimal vs. mild or above for each) was associated with individuals’ responses to the relevant race and employment questions. A Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test showed that depression category was not associated with individuals’ responses to the race question, p = .099. A Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test also showed that individuals’ anxiety category was not associated with individuals’ responses to the race question,

p = .386. With regard to employment, tests of association were conducted between the intended dependent variables and the specific employment responses that were found to differ between the two groups. A chi-square test of independence showed that individuals’ status as “not employed” vs. “employed full-time” was not associated with depression category, X2 (1, N = 99) = .63, p = .429. A chi-square test of independence also showed that these employment statuses were not associated with anxiety category, X2 (1, N = 99) = .27, p = .601. Similarly, Fisher’s Exact tests showed that individuals’ employment responses of “prefer not to answer” vs. “not employed (including students)” were not associated with depression category (p = .156) or anxiety category (p = .317). These results were interpreted as indicating that the ways in which individuals in the two time periods differed demographically did not have significant impact on the study’s dependent variables of interest. Therefore, binary logistic regressions were conducted with only time period as a predictor of each dependent variable.

Relationship Between Time Period and Severity of Depression Symptoms

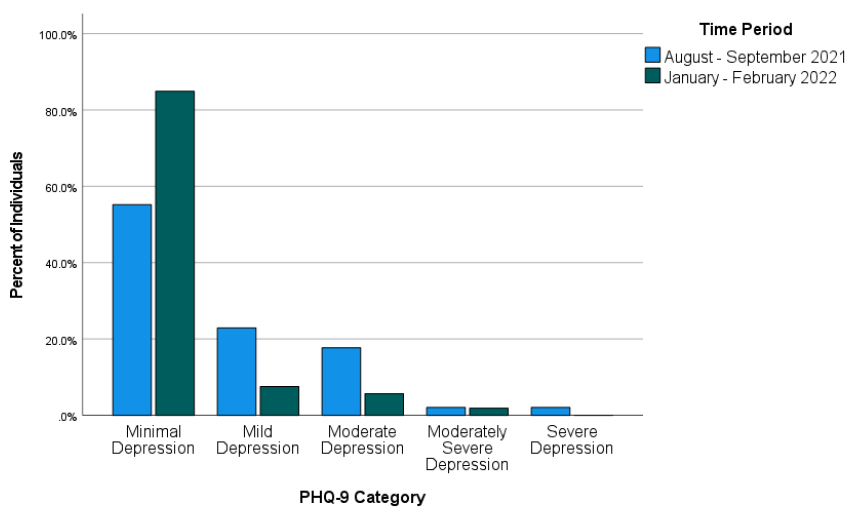

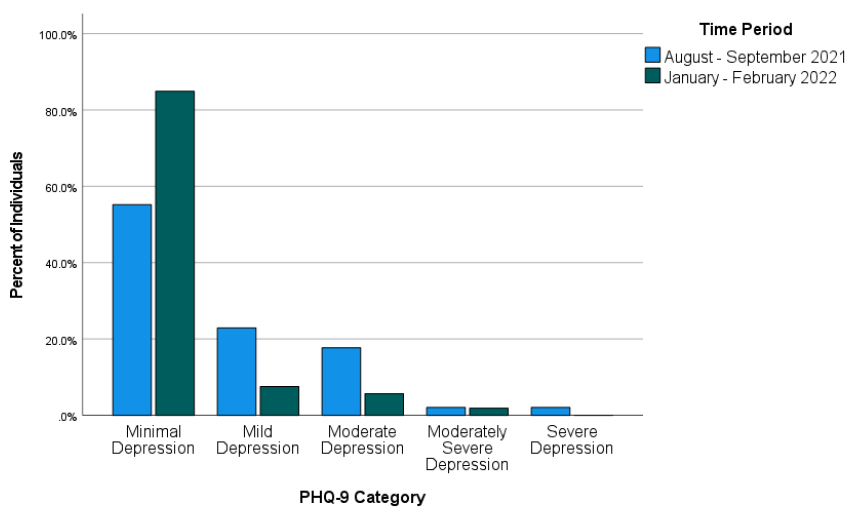

Most individuals in the study were in the minimal depression range on the PHQ-9 as compared to the other four categories. Figure 1 shows the percentage of individuals falling into each of the five PHQ-9 categories during each of the two time periods.

Figure 1

Percentages of Individuals Falling Into Each of the PHQ-9 Categories for Each of the Two Time Periods

Across both time periods combined (August–September 2021 and January–February 2022), 51 individuals (34.23%) were mild or above in depression while 98 (65.77%) were in the minimal range. Binary logistic regression was used to test whether time period predicted severity of depression symptoms. Time period was entered as a predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) of depression (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal depression). The overall binary logistic regression model was found to be statistically significant, χ2(1) = 14.46, p < .001, Cox & Snell R2 = .092, Nagelkerke R2 = .128. In the model, time period was found to be a significant predictor of depression, Wald χ2(1) = 12.17, B = 1.52, SE = .44, p < .001. The model estimated that the odds of being mild or above in depression were 4.56 times higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022 for individuals requesting a mental health check-in following COVID-19 exposure. Specifically, the predicted odds of being mild or above in depression were .81 during August–September 2021 and .18 during January–February 2022.

Relationship Between Time Period and Severity of Anxiety Symptoms

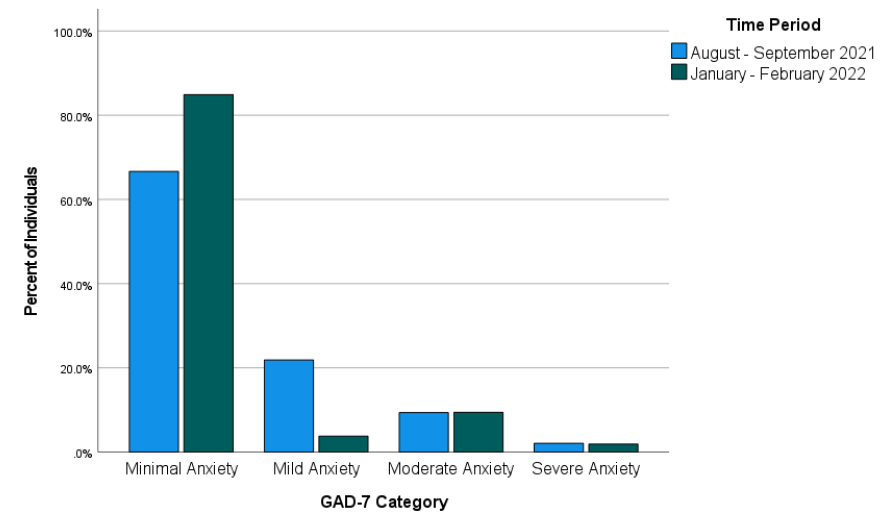

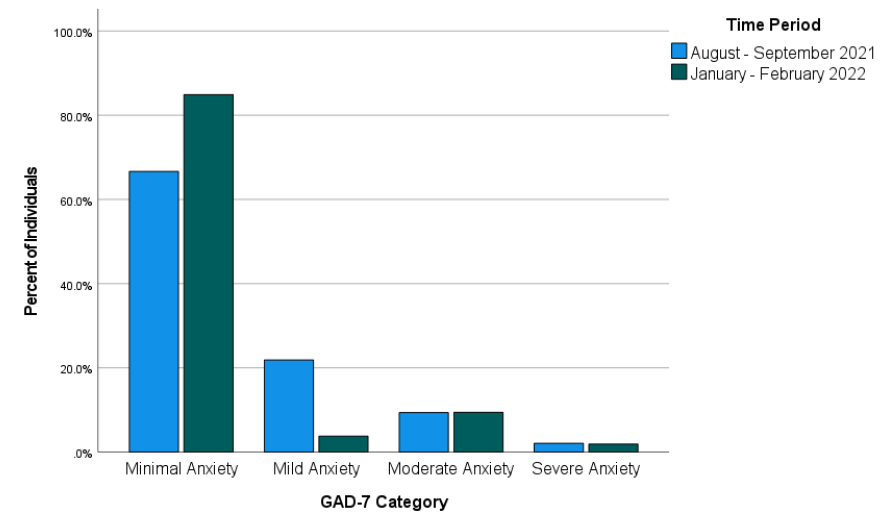

Most individuals in the study were in the minimal anxiety range on the GAD-7 as compared to the other three categories. Figure 2 shows the percentage of individuals falling into each of the four GAD-7 categories during each of the two time periods.

Figure 2

Percentages of Individuals Falling Into Each of the GAD-7 Categories for Each of the Two Time Periods

Across both time periods combined, 40 individuals (26.85%) reported anxiety at levels of mild or above and 109 individuals (73.15%) reported minimal anxiety. Binary logistic regression was used to test whether time period predicted severity of anxiety symptoms. Time period was entered as a predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) of anxiety (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal anxiety). The overall binary logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2(1) = 6.16, p = .013, Cox & Snell R2 = .041, Nagelkerke R2 = .059. In the model, time period was a significant predictor of anxiety, Wald χ2(1) = 5.51, B = 1.03, SE = .44, p = .019. Odds of being mild or above in anxiety were estimated by the model to be 2.81 times higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022 for individuals requesting a mental health check-in after exposure to COVID-19. Specifically, the predicted odds of being mild or above in anxiety were .50 during August–September 2021 and .18 during January–February 2022.

Discussion

This study examined whether time period would predict severity of depression and anxiety symptoms in a sample of individuals exposed to COVID-19 at a university in the Southeastern United States. More specifically, the study addressed the possibility that the likelihood of being mild or above in depression and anxiety would differ between two time periods following the university’s return to in-person operations in August 2021. The results of the study showed that the likelihood of being mild or above in depression and the likelihood of being mild or above in anxiety after exposure to COVID-19 were both higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022. This finding is in line with previous research that found improvements in psychosocial symptomatology in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Tang et al., 2022) and in contrast to research that did not find such improvements (McLeish et al., 2022). Based on the results of the present study, it appears likely that factors that differed between the two assessed time periods (first two months of fall 2021 vs. first two months of spring 2022) contributed to the observed difference in likelihood of depression and anxiety symptoms. McLeish et al. (2022) noted that vaccines were not widely available in their study that did not find such differences, while Tang et al. (2022), who did find significant differences, noted that vaccines were available at their second data collection point (January–March 2021). For individuals in the present study, COVID-19 vaccinations were available. Vaccination was strongly encouraged by university administrators following the return to campus, and more individuals on campus were vaccinated in spring 2022 than in fall 2021. Vaccinations might have lessened individuals’ COVID-19 concerns and contributed to more positive psychosocial outcomes during spring 2022 than fall 2021.

Besides vaccinations possibly lessening depression and anxiety symptoms, other environmental circumstances might also have played a role. The two time periods on which this study focused also differed in their proximity to a significant environmental event—a return to in-person operations on the campus where the individuals studied and/or worked. Early research on the mental health impact of COVID-19 highlighted the negative mental health effects of factors such as reduced physical activity (Silva et al., 2022), life disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Stamatis et al., 2022), and social distancing (Marroquín et al., 2020). Therefore, it is possible that symptoms of depression and anxiety in spring 2022 were affected by changes in specific circumstances known to have negatively impacted mental health earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, individuals’ physical activity likely increased because of a return to campus, and they might have perceived less disruption to their lives through being able to resume in-person activities. Although individuals in the present study who were exposed to COVID-19 during the first 2 months after the return to campus might have reaped some benefits from the return to more normal environmental circumstances, they might also have faced a period of adjustment. In contrast, individuals exposed to COVID-19 between January and February 2022 might have been more readjusted and reaped greater benefits from the return to campus, thereby reducing depression and anxiety symptoms.

Implications

This study’s findings on psychosocial symptomatology across time during the COVID-19 pandemic have important implications for the work of counselors. Based on the results of the present study, counselors planning outreach efforts to individuals exposed to COVID-19 should consider that as time passes, these individuals might be more stable with regard to symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, some individuals directly affected by COVID-19 might still be interested in receiving mental health information despite low levels of depression and anxiety. Many individuals in the present study scored as minimal in depression and anxiety but were still interested in receiving a mental health check-in. Thus, counselors should advocate for mental health information and resources to be made available to individuals who are known to be facing stressors related to COVID-19. Counselors should be prepared to have conversations to determine the contextual needs of individuals exposed to COVID-19 rather than relying only on standardized measures of psychosocial symptomatology. For example, counselors working with employees (such as university employees in the present study) should be attentive to the possibility that employees exposed to COVID-19 may be concerned about facing stigma in their workplace due to their exposure (Schubert et al., 2021).

Given that the present study focused on individuals from a university population, the study’s results also have specific implications for college counselors. College counselors should develop approaches to reach students during circumstances that might make traditional outreach challenging. For example, the present study used data from a mental health intervention in which service providers collaborated with university contact tracers to safely provide mental health resources by telephone to individuals exposed to COVID-19. College counselors should be prepared to connect clients with services at a distance. Previous research during the COVID-19 pandemic found that college students were interested in using teletherapy and online self-help resources, particularly if such services were made available for free (Ahuvia et al., 2022).

Besides preparing for flexible modes of service delivery, college counselors should be prepared to deliver interventions most likely to be useful to college students during the COVID-19 pandemic or similar pandemics. Those recently exposed to COVID-19 might benefit from discussing possible fears associated with COVID-19, experiences of stigmatization they might have experienced due to their exposure, and ways to maintain mental health during any period of quarantine or isolation that might be required. Those not recently exposed to COVID-19 might instead benefit from interventions that address other issues that might have resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic or societal responses to it. For example, if circumstances associated with the COVID-19 pandemic led to reductions in a client’s amount of exercise, a counselor can help the client identify ways they might increase their physical activity. Interventions promoting physical activity were found to reduce anxiety and depression in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic (Luo et al., 2022).

Limitations

This study had limitations that should be considered. First, with the study being retrospective and using secondary data from a clinical intervention, it was not possible to include measures that might have better clarified mechanisms of the changes that were observed in psychosocial symptoms. Thus, the possible explanations above of what might have driven these changes are tentative and future research should test them more directly. Second, individuals in the present study were likely to have been in greater distress than the general university population based on their exposure to COVID-19, which might limit the generalizability of the study’s findings. Third, individuals in the present study were from a single university in the Southeastern United States. Thus, our findings might not generalize to other regions where university-related COVID-19 policies might have differed. Fourth, the decision to create a binary independent variable to reflect time periods (August–September 2021 and January–February 2022) in the present study also entails a limitation. This decision was justifiable on the basis that it allowed for comparisons of individuals at similar points in academic semesters and during comparable periods of COVID-19 infection. However, this analysis decision means that inferences from the study’s results are limited to the two specific time periods that were analyzed. Fifth, individuals in the present study responded to items on the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 through a phone conversation with interviewers. Interviewer-administered surveys have been previously associated with greater tendencies toward socially desirable responses than self-administered surveys (Bowling, 2005). This might limit the present study’s generalizability in contexts where self-administrations of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 are used.

Future Research

The results of this study provide important directions for future research. Future researchers who can conduct prospective studies or who have access to larger retrospective datasets should aim to determine specific factors that might lead to improvement in mental health outcomes over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Knowledge produced by such studies could contribute to clinical applications in the future regarding COVID-19 or other pandemics that might occur. Relatedly, future research with larger samples of demographically diverse participants should explore possible demographic differences in specific mental health trajectories in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Future research should continue to focus specifically on those who are interested in mental health information and interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. To follow up this study’s findings, future quantitative and qualitative studies should aim to identify which individuals are interested in receiving mental health services and determine the best ways to deliver services to them. As a globally experienced stressor, the COVID-19 pandemic might have changed some individuals’ views of mental health and/or their receptiveness to mental health outreach. More specifically, some might be more receptive to available mental health information even at lower thresholds of anxiety, depression, or other psychosocial symptoms. Such clients might be interested in preventive services or their interest in mental health information might be driven by other factors. Future studies should address these possibilities more directly than was possible in the present retrospective study.

Conclusion

Overall, the present study provided a positive picture regarding psychosocial symptomatology in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from this study of students and employees at a university in the Southeastern Unites States following their return to campus found that many individuals requesting mental health information after exposure to COVID-19 showed minimal levels of depression and anxiety. Individuals in the study were more likely to be in these minimal ranges during January–February 2022 than August–September 2021. COVID-19 will continue to have effects in individuals’ lives through future infections and potentially through lasting effects of previous stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. As organized in-person activities resume and COVID-19 infections continue, counseling researchers and practitioners should continue efforts to best characterize and address individuals’ mental health needs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Ahuvia, I. L., Sung, J. Y., Dobias, M. L., Nelson, B. D., Richmond, L. L., London, B., & Schleider, J. L. (2022). College student interest in teletherapy and self-guided mental health supports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2062245

Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054

Bowling, A. (2005). Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. Journal of Public Health, 27(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdi031

Bzdok, D., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2020). The neurobiology of social distance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(9), 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.016

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, March 15). COVID-19 timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html

Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., Rettew, J., & Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 134–141.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466

Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 126–134.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 15(7), Article e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A., & Bu, F. (2021). Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X

Fioravanti, G., Benucci, S. B., Prostamo, A., Banchi, V., & Casale, S. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological health in a sample of Italian adults: A three-wave longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 315, Article 114705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114705

Food and Drug Administration. (2021, August 23). FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

Huckins, J. F., daSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E. I., Meyer, M. L., Wagner, D. D., Holtzheimer, P. E., & Campbell, A. T. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), Article e20185.

https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Liu, C. H., Stevens, C., Wong, S. H. M., Yasui, M., & Chen, J. A. (2019). The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among U.S. college students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depression and Anxiety, 36(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22830

Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46(3), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

Luo, Q., Zhang, P., Liu, Y., Ma, X., & Jennings, G. (2022). Intervention of physical activity for university students with anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215338

Marroquín, B., Vine, V., & Morgan, R. (2020). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Research, 293, Article 113419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419

Martin, A., Rief, W., Klaiberg, A., & Braehler, E. (2006). Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(1), 71–77.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003

McLeish, A. C., Walker, K. L., & Hart, J. L. (2022). Changes in internalizing symptoms and anxiety sensitivity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 44, 1021–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-022-09990-8

Meyer, J., McDowell, C., Lansing, J., Brower, C., Smith, L., Tully, M., & Herring, M. (2020). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in response to COVID-19 and their associations with mental health in 3052 US adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), Article 6469.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186469

Oh, H., Marinovich, C., Rajkumar, R., Besecker, M., Zhou, S., Jacob, L., Koyanagi, A., & Smith, L. (2021). COVID-19 dimensions are related to depression and anxiety among US college students: Findings from the Healthy Minds Survey 2020. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.121

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Dosil Santamaría, M., & Picaza Gorrotxategi, M. (2020). Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: An investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 1491.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01491

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R., & Feinstein, A. R. (1996). A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49(12), 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Prati, G., & Mancini, A. D. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological Medicine, 51(2), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000015

Rettie, H., & Daniels, J. (2021). Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000710

Riehm, K. E., Holingue, C., Kalb, L. G., Bennett, D., Kapteyn, A., Jiang, Q., Veldhuis, C. B., Johnson, R. M., Fallin, M. D., Kreuter, F., Stuart, E. A., & Thrul, J. (2020). Associations between media exposure and mental distress among U.S. adults at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(5), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.008

Schubert, M., Ludwig, J., Freiberg, A., Hahne, T. M., Romero Starke, K., Girbig, M., Faller, G., Apfelbacher, C., von dem Knesebeck, O., & Seidler, A. (2021). Stigmatization from work-related COVID-19 exposure: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126183

Silva, D. T. C., Prado, W. L., Cucato, G. G., Correia, M. A., Ritti-Dias, R. M., Lofrano-Prado, M. C., Tebar, W. R., & Christofaro, D. G. D. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity level and screen time is associated with decreased mental health in Brazillian adults: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Psychiatry Research, 314, Article 114657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114657

Şimşir, Z., Koç, H., Seki, T., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Death Studies, 46(3), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1889097

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), Article e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Stamatis, C. A., Broos, H. C., Hudiburgh, S. E., Dale, S. K., & Timpano, K. R. (2022). A longitudinal investigation of COVID-19 pandemic experiences and mental health among university students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12351

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Tang, N. K. Y., McEnery, K. A. M., Chandler, L., Toro, C., Walasek, L., Friend, H., Gu, S., Singh, S. P., & Meyer, C. (2022). Pandemic and student mental health: Mental health symptoms amongst university students and young adults after the first cycle of lockdown in the UK. BJPsych Open, 8(4), Article e138.

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.523

Wise, T., Zbozinek, T. D., Michelini, G., Hagan, C. C., & Mobbs, D. (2020). Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

Royal Society Open Science, 7(9), Article 200742. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200742

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Wesley B. Webber, PhD, NCC, is a postdoctoral scholar at East Carolina University. W. Leigh Atherton, PhD, LCMHCS, LCAS, CCS, CRC, is an associate professor and program director at East Carolina University. Kelli S. Russell, MPH, RHEd, is a teaching assistant professor at East Carolina University. Hilary J. Flint, NCC, LCMHCA, is a clinical counselor at C&C Betterworks. Stephen J. Leierer, PhD, is a research associate at the Florida State University Career Center. Correspondence may be addressed to Wesley B. Webber, Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies, Mail Stop 677, East Carolina University, 1000 East 5th Street, Greenville, NC 27858-4353, webberw21@ecu.edu.

Nov 9, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 4

Jennifer Scaturo Watkinson, Gayle Cicero, Elizabeth Burton

It is widely documented that practicum students experience anxiety as a natural part of their counselor development. Within constructivist supervision, mindfulness exercises are used to help counselors-in-training (CITs) work with their anxiety by having them focus on their internal experiences. To inform and strengthen our practice, we engaged in a practitioner inquiry study to understand how practicum students experienced mindfulness as a central part of supervision. We analyzed 25 sandtray reflections and compared them to transcripts from two focus groups to uncover three major themes related to the student experience: (a) openness to the process, (b) reflection and self-care, and (c) attention to the doing. One key lesson learned was the importance of balancing mindfulness exercises to highlight the internal experiences related to anxiety while providing adequate opportunities for CITs to share stories and hear from peers during group supervision.

Keywords: supervision, mindfulness, counselors-in-training, anxiety, practitioner inquiry

It is widely documented that counselors-in-training (CITs) experience anxiety as part of the developmental process (Auxier et al., 2003; Kuo et al., 2016; Moss et al., 2014). Reasons for anxiety include CITs’ doubts about their ability to perform competently within their professional role (Moss et al., 2014) coupled with perfectionism (Kuo et al., 2016). Additionally, Auxier et al. (2003) noted that CITs’ anxiety also stems from the pressure associated with external evaluation provided by supervisors. Wagner and Hill (2015) added that CITs’ need for external validation from their supervisors, coupled with the belief that there is only one right way to counsel clients, also generates anxiety. This need for external validation creates an overreliance on a supervisor’s judgment that could render a CIT helpless (Wagner & Hill, 2015). Although a moderate amount of anxiety may increase a person’s focus and positively impact productivity, too much anxiety impedes learning and growth (Kuo et al., 2016). Hence, there is a need for supervisors to address anxiety early in a CIT’s development to foster self-reliance and professional growth (Ellis et al., 2015; Mehr et al., 2015).

The two lead authors of this article, Jennifer Scaturo Watkinson and Gayle Cicero, are counselor educators who supervised school counseling practicum students and ascribed to a constructivist approach to supervision. While discussing supervision pedagogy, we shared our observations on how anxious our practicum students were to be evaluated and our belief that their anxiety often limited their professional growth and development as counselors. Within constructivist supervision, mindfulness exercises are used to help CITs work with their anxiety by having them focus on their internal experiences of discomfort (Guiffrida, 2015). Thus, we utilized mindfulness as a central approach to helping our students work with their anxiety associated with the counselor developmental process.

To assist in our planning, we reviewed the supervision literature and found that discussions on mindfulness were largely conceptual (Guiffrida, 2015; Johnson et al., 2020; Schauss et al., 2017; Sturm et al., 2012) or outcome-based (Bohecker et al., 2016; Campbell & Christopher, 2012; Carson & Langer, 2006; Daniel et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2017), with limited focus on supervision pedagogy to guide supervisors on how to integrate mindfulness into their practicum seminars, particularly from the perspective of the practitioner. Further, Barrio Minton et al. (2014) and Brackette (2014) confirmed that there was a scarcity of counselor education literature that focused on teaching pedagogy and argued that more research in this area was needed to improve counselor preparation. To add to the current literature on supervision pedagogy and inform our practice, we engaged in a practitioner inquiry study (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009) and formed a professional learning community to investigate how utilizing mindfulness within our supervision could help school counseling practicum students work with their anxiety.

Literature Review

Constructive Supervision

Supervisors who utilize constructivist principles help CITs make meaning of their experience by examining how their approach benefits their clients (Guiffrida, 2015). Constructivism is built upon the belief that knowledge is not derived from absolute realities but rather localized to specific contexts and personal experiences. McAuliffe (2011) argued that knowledge is “continually being created through conversations” and is not given to the learner through a one-sided expert account. Constructivists believe that learning is “reflexive and includes a tolerance for ambiguity” (McAuliffe, 2011, p. 4). Constructivist supervisors prioritize CITs’ experiences, encouraging them to examine the intent behind their approach and reach their own conclusions. Hence, constructive supervisors help supervisees deconstruct experiences that have multiple “right” approaches to client care while normalizing the anxiety associated with professional growth. Within a constructivist supervision framework, moderate amounts of anxiety are not viewed as problematic but rather are seen as a catalyst for change (Guiffrida, 2015) and part of the learning process (McAuliffe, 2011). Guiffrida (2015) asserted that the aim of supervision in the early stages of counselor development is not to remove feelings of anxiety but rather to help the CIT acknowledge and live with the anxiety. Utilizing mindfulness, supervisors acknowledge CITs’ internal experiences and guide them through intentional mindfulness practices to generate personal and professional reflection and meaning making.

Within constructivist supervision, mindfulness is a central approach to helping CITs work with their anxiety (Guiffrida, 2015). Kabat-Zinn (2016) defined mindfulness as “paying attention in a sustained and particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally” (p. 1). Constructive supervisors facilitate learning experiences that promote introspection and intentionally direct CITs to examine their internal experience, without judgment, during times of disequilibrium. Rather than helping a CIT rid themselves of anxiety, the constructivist supervisor acknowledges that anxiety is a normal response to the uncertainty of doing something for the first time (Guiffrida, 2015). Mindfulness provides a platform for a supervisor to normalize anxiety within the supervisory relationship (Sturm et al., 2012). Hence, supervisors can utilize mindfulness to prioritize the CITs’ internal experiences (e.g., doubt, uncertainty, fear) and foster self-reliance.

Mindfulness as an Approach

Mindfulness practices are linked to the personal and professional growth of CITs (Bohecker et al., 2016; Campbell & Christopher, 2012). Campbell and Christopher (2012) compared counseling students who participated in a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program to a control group and found that those who participated in MBSR reported significant decreases in stress, negative affect, rumination, and state and trait anxiety while noting a significant increase in positive affect and self-compassion when compared to participants in the control group. Additionally, Christopher and Maris (2010) reported that supervisees who were exposed to mindfulness were “more open, aware, self-accepting, and less defensive in supervision” (p. 123). Similarly, Bohecker et al. (2016) discovered that CITs who participated in a mindfulness experiential small group saw the benefits of attending to their emotions (e.g., internal experiences) and acknowledged that mindfulness increased self-awareness and promoted objectivity when attending to their thoughts. Having objectivity allowed them to be in the present, which positively affected their behavioral responses (Bohecker et al., 2016).

CITs also experienced benefits to having mindfulness incorporated into their practicum and internship seminar classes. Dong et al. (2017) examined CITs’ response to mindfulness-based activities and discussions during internship seminar. Results suggested that CITs who engaged in mindfulness practices were more focused on the moment and responded to stressors with acceptance and nonjudgment. As a result, CITs were more likely to be “okay with not being okay” when faced with challenging situations (Dong et al., 2017, p. 311). Additionally, Dong and his colleagues noted that participants were able to validate themselves when they made mistakes and were more accepting of their rough edges. Carson and Langer (2006) agreed and added that CITs who received mindfulness as part of their supervision were better able to examine the thoughts that contributed to their anxiety and were more open to accepting their mistakes as learning opportunities. As a result, CITs minimized the focus they put on self-criticism and were less vulnerable when they made mistakes (Carson & Langer, 2006). These studies highlight how CITs benefited from integrating mindfulness into group supervision, yet there is limited research on how counselor educators might structure their practicum seminars to include mindfulness as an integrated approach to supervision.

Purpose of the Present Study

The purpose of this practitioner inquiry was to inform Watkinson and Cicero’s practice as supervisors of practicum school counseling students within a CACREP-accredited program. We utilized mindfulness as a central approach to group supervision during practicum seminar and wanted to understand how intentional mindfulness exercises that prioritized the CITs’ internal experiences (e.g., uncertainty, doubt, fear) were perceived by our students. By understanding the student experience, we could make informed decisions about how we might improve upon the way we integrate mindfulness into future seminar meetings. Specifically, we were guided by this research question: How are CITs experiencing mindfulness as part of group supervision provided during practicum seminar?

Method

We engaged in a practitioner inquiry study (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009) to examine the application of mindfulness within the context of our practice. Cochran-Smith and Lytle (2009) argued that the examination of one’s practice privileges practitioner knowledge and adds to the overall discourse on teaching pedagogy, as “deep and significant changes in practice can only be brought about by those closest to the day-to-day work of teaching and learning” (p. 6). Although not intended to generalize knowledge, practitioner inquiry positions the researcher as a participant to uncover tensions and challenges that come from applying theory to practice while enhancing the knowledge of the practitioner doing the investigation (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009). Thus, we intended to reflect upon how we integrated mindfulness into supervision by understanding the experiences of our practicum students.

Participants

We gained approval from our university’s IRB to conduct the study and invited all 33 CITs enrolled in our practicum sections to participate. Twenty-five (76%) CITs agreed to participate. Of the 25 participants, 24 identified as female (96%) and one identified as male (4%). Sixteen students (64%) self-identified as White/Caucasian, five (20%) as African American, three (12%) as Hispanic, and one (4%) as other. Eighty-four percent of participants were full-time students and 16% identified as part-time. Students were told they could withdraw their participation at any time. All practicum students completed their field experience in public schools.

To safeguard participants from believing they were required to join the study, Watkinson and Cicero were not aware of which students agreed to participate until the end of the semester, when grades were submitted. To protect participant identity until after the semester, we took the following steps: 1) the third author, Elizabeth Burton, was the only one who knew the identity of the participants; 2) Burton recruited participants, stored data (erasing identifying information), and communicated with the participants; 3) the data source labeled sandtray reflections included activities that all CITs completed as part of a required seminar experience; 4) a focus group was held after the semester concluded and grades were submitted; and 5) during data collection, Watkinson and Cicero never discussed the study with any of the CITs enrolled in practicum.

Seminar Context

The practicum course is the first field experience for CITs enrolled in the school counseling master’s program. As per the CACREP 2016 Standards, the practicum experience is a 100-hour experience in which 40% of those hours are in direct service. In addition to meeting those direct hours by working with several individual clients, practicum students are also required to design and run a small counseling group and deliver several classroom lessons within schools. Further, CACREP-accredited programs must provide practicum students with 1.5 hours on average of group supervision per week throughout the duration of the semester. Thus, our practicum seminars were designed to provide CITs with the required group supervision.

All practicum seminar sessions met in person except for one, which was held synchronously through Zoom, a web conferencing platform. There were three sections of practicum, two taught by Cicero and one taught by Watkinson. Watkinson and Cicero drew upon constructive supervision principles and mindfulness core concepts (e.g., self-compassion, present moment, and nonjudgment) to guide the planning of the practicum seminars. We maintained similar course structures, objectives, and learning outcomes utilizing similar room arrangements, mindfulness exercises, and structured learning experiences. Mindfulness exercises were central to the practicum seminar and were focused on the practicum students’ internal experiences. The 15 weekly practicum seminars were 90 minutes in length, and student-to-faculty ratios were 9:1 for two of the practicum sections and 6:1 for the third. The room arrangement consisted of a circle of chairs for students to use during the opening and closing of the seminar, along with a designated workspace for students to sit at tables to take notes or complete reflective class experiences. Soft meditation music played as students entered the room and was turned off to signal the beginning of class.

Watkinson and Cicero engaged in weekly collaborative planning meetings throughout the 15-week semester to plan their seminar meetings and share insights related to student learning. The instructional design was experiential and incorporated mindfulness exercises during the opening of the seminar to bring attention to the “here and now,” breath, nonjudgment, and self-compassion. Cicero was previously trained in mindfulness and exercises were selected based upon her training; Cicero taught Watkinson how to implement those mindfulness exercises during their weekly meetings. Many of the opening mindfulness exercises can be found through internet searches.

Structure of Seminar Meetings

The structure and room arrangement for each practicum seminar were consistent across the three sections. Fourteen of the 15 seminar meetings began with the CITs participating in a 5-minute mindfulness opening that transitioned into structured learning experiences and ended with a sharing circle. Seminar Meeting 11 was entirely dedicated to mindfulness, engaging practicum students in several mindfulness activities for the purpose of drawing their attention to breath and reflection.

Mindfulness Openings

The 5-minute mindfulness openings were scripted and consisted of either a guided meditation (e.g., Calm Still Lake, A River Runs Through It), intentional breathing exercises (e.g., Balloon Breath, Meditative Chimes) or chair yoga (e.g., Mountain Pose, Warrior 2). Each mindfulness opening concluded with reflective questions to increase awareness of the present moment (e.g., What was this experience like for you?). The meditation exercises were varied to introduce CITs to different approaches they might want to try outside of seminar for personal use or in their own practice with K–12 students.

Structured Learning Experiences

After the mindfulness opening, CITs participated in structured learning experiences that focused on either counselor development, case conceptualization, group counseling leadership, evidence-based planning, or classroom curriculum development and instruction. Guided by constructivist supervision principles, two of the structured learning experiences implemented were metaphorical case drawing (Guiffrida, 2015) and sandtray (Guiffrida, 2015; Saltis et al., 2019).

Metaphorical Case Drawing. Guiffrida’s (2015) metaphorical case drawing was used to assist CITs in the development of their case conceptualization skills. In Guiffrida’s work, a metaphorical case drawing has three steps. First, CITs reflect upon six items that highlight their internal experiences and perspectives specific to an individual counseling session with one of their clients: 1) identification of the client’s primary concern, 2) description of the client and CIT interaction, 3) CIT’s intention for the session, 4) CIT’s description of how they viewed their performance as a counselor during the session, 5) general assessment of how the session went, and 6) statement on what the CIT thought the client gained from the session. Second, CITs use images and/or metaphors to respond to three of the six items above to create a case drawing. Lastly, utilizing their case drawings, CITs share their cases with the supervisor and other supervisees. Through the presentation of their case, the CITs interpreted their work while the supervisor and other supervisees listened and asked questions to facilitate deeper insight by offering alternative perspectives.

Sandtray. Although sandtray is typically used in supervision to help CITs develop their case conceptualization skills (Anekstein et al., 2014; Guiffrida, 2015; Guiffrida et al., 2007), we modified our use of sandtray to focus the CITs on their developmental journey as counselors. Like the metaphorical case drawing, the sandtray facilitates an internal examination where CITs get to interpret their own experience (Guiffrida et al., 2007). The sandtray was used in Seminar Meetings 6 and 13 to document how CITs were encountering practicum at two different times in the semester. The written reflections that followed the sandtray were used as a data source for this study and are therefore described in further detail.

Prior to creating an image in the sandtray, CITs were asked to journal about their experience as a practicum student. The prompt was left open so that CITs would have the freedom to focus on the most salient part of their experience. Next, CITs were partnered to create a sandtray image and each pair were given a large box that contained sand and a small baggie filled with a variety of miniature objects. CITs had 5 minutes to create an image in response to this prompt: Create an image that represents your practicum experience thus far. At the conclusion of the 5 minutes, CITs shared their stories with their partners. After everyone created a sandtray image and shared, CITs wrote a reflection in response to this prompt: Drawing from the sandtray exercise and sharing, describe your experience in practicum thus far. Identify and describe the thoughts and feelings you have as you begin your work with students. These written reflections were submitted to the professor at the conclusion of the seminar meeting.

At Seminar Meeting 13, CITs created and shared their sandtray images. Following the same procedure as identified in Seminar Meeting 6, CITs engaged in the sandtray activity again to create a new image in response to a new prompt: Create an image that described your overall experience in practicum. After creating and sharing of their image with a partner, students reflected and responded in writing to a final prompt: Drawing from the sandtray exercise, describe your experience in practicum. Identify and describe your thoughts and feelings now that practicum has come to an end. What have you learned about yourself? Written reflections were completed during the seminar meeting and submitted to the professor when class ended.

Sharing Circle

After the structured learning experience, each seminar concluded with a 5–10 minute sharing circle where students summarized new insights and identified actions to implement at their practicum site. The sharing circle was guided by two questions: What are some key takeaways from today’s seminar? and How might we use what we have learned today within our own practice?

Structure of Mindfulness Seminar Meeting

Seminar Meeting 11 was fully dedicated to the practice of mindfulness and did not follow the above seminar format and structure. During this one 90-minute class, CITs identified an intention, created a mindfulness jar, journaled, and walked a labyrinth. Johnson et al. (2020) argued that CITs who receive mindfulness as part of their supervision should start or maintain a mindfulness practice of their own. Yet there is nothing in the research that identifies specific mindfulness exercises as being essential to that practice, only that CITs should be exposed to mindfulness as part of the classroom experience (Johnson et al., 2020). Thus, our intent for this seminar meeting was to engage CITs in mindfulness exercises that would encourage meditation and reflection. For this class we requested a large room to accommodate a small circle arrangement of 10 chairs and three stations: a labyrinth, creating a mindfulness jar, and journaling. During this seminar meeting, the CITs were instructed to visit the three stations at their own pace and to self-select the order in which they participated in those stations. Class opened with a mindfulness exercise that focused on breath and ended with a sharing circle to debrief. An example of a closing question posed by the professors during the sharing circle is: What insights would you like to share about your experience in seminar today?

Labyrinth. CITs were given a brief description of a labyrinth along with written instructions on how to set an intention and walk the labyrinth. We created a floor labyrinth for use during the seminar. CITs set their intention prior to walking the labyrinth. Some examples of intentions were to be open to the process or to demonstrate self-compassion. Once inside the labyrinth, CITs would follow the path and could walk the labyrinth as many times as they desired.