Body Neutral Parenting: A Grounded Theory of How to Help Cultivate Healthy Body Image in Children and Adolescents

Emily Horton

Body neutrality is a concept wherein individuals embody a neutral attitude toward the body that is realistic and flexible, appreciate and care for the function of the body, and acknowledge that self-worth is not defined by one’s outward appearance. Family behavior regarding body image has been related to higher levels of body dissatisfaction and unhealthy eating behavior among children and adolescents. Caregivers need knowledge and support on how to cultivate healthy body image for their children and adolescents. Limited studies explore how to parent in a way that promotes healthy relationships with one’s body, food, and exercise. I conducted a grounded theory study to explore the experiences of caregivers who integrate tenets of body neutrality. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 caregivers of children and adolescents who self-identified as approaching parenting from a place of body neutrality. Through constructivist grounded theory, I discerned insights regarding how caregivers can support their children and adolescents in developing healthy relationships with their bodies and how this corresponds with self-esteem. Considerations for counselors using body neutrality to support children, adolescents, and caregivers are provided.

Keywords: body neutrality, body image, parenting, children and adolescents, self-esteem

Body image and related low self-esteem are frequently under-addressed or unaddressed in counseling children, adolescents, and their caregivers (Damiano et al., 2020). Too often, counselors may take a reactive approach to addressing unhealthy relationships with food, bodies, and exercise in the family system, such as counseling after an adolescent is diagnosed with an eating disorder (Liechty et al., 2016). Thus, counselors may benefit from considering how to take a preventative, proactive approach to supporting children’s mental health specific to their relationship with food, bodies, and movement (Siegel et al., 2021). Because the family system has tremendous impact on children’s body image and relationship with food, counselors need to consider how to provide appropriate psychoeducation and support to caregivers on how to manage food and body talk (Gutin, 2021). Positive caregiver influence on body image can prevent disordered eating, negative body image, and low self-worth, and many families need a licensed mental health professional to cultivate said positive influence (Veldhuis et al., 2020).

Researchers have found that children as young as 3 to 5 years old experience body image issues (Damiano et al., 2015; Dittmar et al., 2006). Caregivers often communicate body dissatisfaction, engage in dieting, and demonstrate a drive for thinness, messages that children can internalize (National Eating Disorders Association, 2022). Families can inadvertently pass down unhealthy ideals regarding body image to their children (Kluck, 2010). Kluck (2010) emphasized that a family’s focus on appearance was related to their child’s body image dissatisfaction, and the dissatisfaction predicted increased disordered eating. Counselors with appropriate training can play an important role in mitigating the harmful cycle before disordered thinking turns into disordered eating (Klassen, 2017). Counselors have the unique opportunity to support families in encouraging a healthy relationship with their bodies (Horton, 2023; Horton & Powers, 2024).

In this study, I sought to explore the experiences of caregivers who integrate tenets of body neutrality. Body neutrality is a concept wherein individuals embody a neutral attitude toward the body that is realistic and flexible, appreciate and care for the function of the body, and acknowledge that self-worth is not defined by one’s outward appearance (Pellizzer & Wade, 2023). Examples of body neutrality can include not describing food as healthy or unhealthy, talking about what our bodies do for us rather than what they look like, and moving for enjoyment rather than to burn calories. Because the tripartite model emphasizes that parental influence, in addition to peer and media influence, is significant for children’s body image development, I explored existing research on parental influence on body image and self-esteem (Thompson et al., 1999).

Parental Influence on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Some family members negatively impact children’s and adolescents’ body image (Pursey et al., 2021). Neumark-Sztainer et al. (2010) found that over half of the adolescents in their study experienced weight-based and appearance-based teasing from family, and these experiences correlated to higher levels of body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and related mental health difficulties, such as depression. Parental influence on body image includes both direct (e.g., criticism about their child’s weight) and indirect (e.g., parents’ attitudes about their own bodies, food, and exercise) behaviors (Rodgers & Chabrol, 2009). Abraczinskas and colleagues (2012) conducted a study exploring parent direct influence, including weight- and eating-related comments, and modeling, including parental modeling of dieting and related behavior. In the study of over 360 participants, Abraczinskas and colleagues found that parental influence is a risk factor in the development of a drive for thinness, body shape dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptomology.

Moreover, Wymer and colleagues (2022) emphasized the importance of parent engagement in body image and self-esteem development. Often, families recognize the importance of discussing body image with their children but do not feel confident or competent in doing so (Siegel et al., 2021). The lack of confidence and competence leads to messages about health being conflated with messages about thinness (Siegel et al., 2021). In addition, researchers highlighted that although parental influence has a significant impact on body image and self-esteem, siblings, friends, and the media are also perceived to have influence over youth’s feelings about their bodies (Ricciardelli et al., 2000). The exiguous literature on parental influence on body image repeatedly emphasizes the negative impact of parents on body image yet seldom explores preventative and therapeutic ways of promoting healthy body image (Phares et al., 2004). Thus, I sought to explore how counselors might integrate body neutrality when supporting families and provide early intervention and prevention for adverse relationships with food, body, and movement.

Body Neutrality

Body neutrality is a concept wherein individuals accept their bodies as a vessel that carries them through life, and as such, do not attach positive or negative feelings to their physicality. For example, body neutrality can entail nurturing and respecting the body, being mindful of body talk, engaging in body gratitude and functionality appreciation, and recognizing self-worth that is not focused on appearance (Pellizzer & Wade, 2023). Body neutrality is an approach taken to help with the healing of body image, particularly in the field of eating disorders (Perry et al., 2019). Body neutrality tenets appear to be integral in the prevention of body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating (Herle et al., 2020). Practicing body neutrality positively impacts body satisfaction, self-esteem, and negative affect with adults, though continued empirical research is needed on its impact with youth (Walker et al., 2021). Although counselors and other allied professionals integrate body neutrality into their clinical practice, there is minimal research on its efficacy outside of eating disorder treatment. Existing research has emphasized the need for counseling approaches with youth that highlight body neutrality tenets, such as mindful eating and awareness-building conversations about societal messaging (Klassen, 2017). However, researchers have yet to explore how body neutrality could be integrated into a parenting approach. The bulk of the limited understanding of body neutrality is treatment based, rather than prevention oriented.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to cultivate a grounded theory or an abstract theoretical understanding of body neutral parenting (Charmaz, 2014). Further insight into the experiences, challenges, and potential barriers in parenting with body neutrality can enable a deeper understanding of how parents seek to promote healthy body image and self-esteem for children and adolescents. In this study, I aimed to offer a newfound understanding to mental health professionals supporting children, adolescents, and caregivers in the areas of body, food, movement, and related mental health implications.

Method

Methodology

To address the paucity of literature, a grounded theory study was conducted to examine the following research question: How do caregivers conceptualize and actualize body neutral parenting with their children? The study derived from constructivist grounded theory (CGT; Charmaz, 2014). CGT is an interpretative, qualitative methodology that acknowledges that researchers and participants co-create the theory (Charmaz, 2014). Given a desire to understand how caregivers conceptualize and utilize body neutral parenting, CGT was deemed appropriate. The purpose of the study was to generate a new theory through inductive analysis of data gleaned from caregivers who self-identify as using body neutral parenting.

Role of the Researcher

Congruent with CGT, I maintained a position of distant expert (Charmaz, 2014). The theoretical meaning was constructed by turning participants’ experiences into digestible theoretical interpretations. While staying as true to the experiences of the participants as possible, I reconstructed the participants’ stories in the development of the grounded theory via balancing conceptual analysis of participants’ stories and creating a sense of their presence in the narrative (Mills et al., 2006). I sought to examine the impact of my privilege and preconceptions as a White, cisgender woman and professional in the field of mental health counseling, with experience supporting families navigating eating disorders and disordered eating (Charmaz, 2014). Also, as a parent who integrates body neutrality into my approach with my child, I practiced reflexive journaling and other trustworthiness strategies to bracket my biases throughout the study.

Participant Recruitment

I obtained IRB approval prior to data collection. Per the IRB, all participants verbally consented before partaking in the research study. I used purposive sampling (Patton, 2014) for participant selection. Selection criteria included: (a) being a caregiver to at least one child under the age of 18, (b) identifying as integrating body neutrality into their parenting approach, and (c) willingness to participate in an interview lasting roughly 1 hour. I circulated electronic flyers detailing the focus of the study to social media pages for caregivers and professional networks. The recruitment flyers provided examples of body neutral parenting, including not describing food as healthy or unhealthy, talking about what our bodies do for us rather than what they look like, and moving for enjoyment rather than to burn calories.

Ten participants were interviewed. Of the 10 participants, nine identified as cisgender women and one identified as nonbinary. All 10 participants described themselves as being middle class. Nine participants were married and one was single. All of the participants had graduate-level or doctorate-level educations; four had master’s degrees and six had doctoral degrees. Participants lived in seven different states and two different countries. Participants had at least one child, with the number of children ranging from 1 to 5. Table 1 provides detailed demographic data.

Table 1

Participants’ Demographic Data

| Pseudonym | Age | Race | Number

of Children |

Age of Children | Race of Children |

| Logan | 27 | White | 1 | 20 months | White |

| Esmeralda | 38 | Hispanic | 2 | 8 and 5 years | White |

| Imani | 29 | Black, White | 2 | 6 and 3 years | White |

| Kimberly | 33 | White | 2 | 5 and 2 years | White |

| Heather | 42 | White | 2 | 3 years, 8 months | White |

| Cassie | 45 | White | 5 | 16, 13, 11, 9, and 7 years | White |

| Shanice | 36 | African American | 4 | 15, 9, and 2 years; 4 months | African American |

| Scarlett | 36 | White | 3 | 17, 5, and 4 years | White |

| Leilani | 43 | White | 1 | 9 years | Polynesian, White |

| Jennifer | 36 | White | 1 | 2 years | Middle Eastern, White |

Data Collection and Analysis

As guided by Charmaz’s (2014) CGT protocol, data collection and data analysis proceeded simultaneously, and the inclusion criteria evolved to include caregivers with children of all ages. The semi-structured interviews occurred via confidential videoconferencing software and lasted between 60 and 75 minutes. Interviews were an open-ended, detailed exploration of an aspect of life in which the participants had substantial experience and considerable insight: parenting with body neutrality principles (Charmaz & Liska Belgrave, 2012). During the interviews, I inquired about caregivers’ experiences, challenges, and insights of body neutral parenting. With the emergent categories, the guide evolved to emphasize the nuances of the parenting approach in alignment with three-cycle coding or focused coding (Charmaz, 2014).

Grounded theorists try to elicit their participants’ stories and attend to whether the participants’ interpretations are theoretically plausible (Charmaz & Liska Belgrave, 2012). As such, the interview protocol began with an initial open-ended question: “Tell me about a time in which you used body neutral parenting.” Then, I asked intermediate questions, such as “How, if at all, have your thoughts and feelings about body neutral parenting changed since your child was born?” I also asked ending questions, including: “How has taking the approach with your children impacted you as a parent? As a person?” The interview questions were informed by the literature and were reviewed by another content matter expert.

In addition to the in-depth interview, I used information from other data sources to support the depth of the data and theory construction. Other triangulated data sources included field notes of observations during the interviews, a reflexive journal, literature and previous research on body neutrality, and a demographic survey. In this way, the constant comparative analysis unique to CGT increases rigor through complex coding procedures more so than other methods of qualitative data analysis (Hays & McKibben, 2021). The constant comparative analysis examines nuanced relationships between participants through negative case analysis to strengthen findings (Hays & McKibben, 2021).

Three-cycle coding and constant comparative analysis drove the data analysis process (Charmaz, 2014). Through the data analysis process, I constantly compared data (Mills et al., 2006). Inductive in nature, the constant comparison through the data analysis grounded my theories from the participants’ experiences (Mills et al., 2006). In alignment with CGT, I coded the interviews through a fluid process of initial coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding. During initial coding, I focused on “fragments of data,” such as words, lines, segments, and incidents (Charmaz, 2014, p. 109). The initial coding process not only included the transcripts, but also continued the interaction and data collection to facilitate the continuous analytical process. I also engaged with focus coding, wherein I used the most significant and frequent codes that made the most analytic sense (Charmaz, 2014). The focused codes were more theoretical than line-by-line coding practices. I engaged in theoretical coding of the data; theoretical coding is a way of “weaving the fractured story back together” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 63). In accordance with Charmaz (2014), theoretical coding involved clarifying the “general context and specific conditions” and discovering “participants’ strategies for dealing with them” (p. 63). As I moved throughout the three-cycle coding process, the number of codes, categories, and emerging core categories decreased and refined, leaving me with the final core categories described below (Khanal, 2018).

Rigor and Trustworthiness

Throughout the totality of the research process, I engaged with five strategies to ensure trustworthiness. In the data analysis process, significant care was taken to ground analytic claims in the data obtained and remain true to the raw material provided by participants (Charmaz, 2014). I fostered trustworthiness through member checking and memo-writing (Creswell & Poth, 2017). I sent the transcript and the themes to participants and had six of 10 participants verify the themes as being congruent with their experiences. The other participants did not respond to the email with the transcript. Memo-writing was critical in constructing theoretical categories (Charmaz, 2014). I stopped and analyzed my ideas about the codes and emerging categories via memo-writing. Successive memos kept me immersed in the analysis and increased the abstraction of my ideas (Charmaz, 2014). In the theory construction, I also triangulated data sources, including semi-structured interviews, field notes of observations during the interviews, memo-writing, literature and previous research on body neutrality, and a demographic survey. Charmaz (2014) emphasized the importance of “thick descriptions” (p. 14), which I captured via writing extensive field notes of observations during the interviews and compiling detailed narratives from transcribed tapes of interviews.

I also shared my memos and data analysis process with an external auditor (Hays & McKibben, 2021). The external auditor was a researcher with experience in qualitative research and content familiarity. After the external auditor reviewed the data analysis trail, including the three stages of coding, I reviewed her written feedback and we met to process the feedback. The external auditor offered several pieces of feedback regarding the analytic process, including leaning more into the theory rather than the stories and removing quotes that captured pieces outside of the theory (i.e., removing content rooted in diet culture and body positivity). Feedback was integrated to strengthen the study’s development and explication of the theory based on data.

Results

This study involved the caregivers and researcher co-constructing the parenting theory while integrating body neutrality concepts. The theory stemmed from the perspectives shared by caregivers who parent in such a way as to promote body acceptance, such as focusing on what our bodies can do for us, avoiding body talk, eating the foods we want to eat, listening to our bodies, not focusing compliments on appearance, etc. As such, the grounded theory below explains caregivers interacting and experiencing body neutral parenting (Charmaz, 2014).

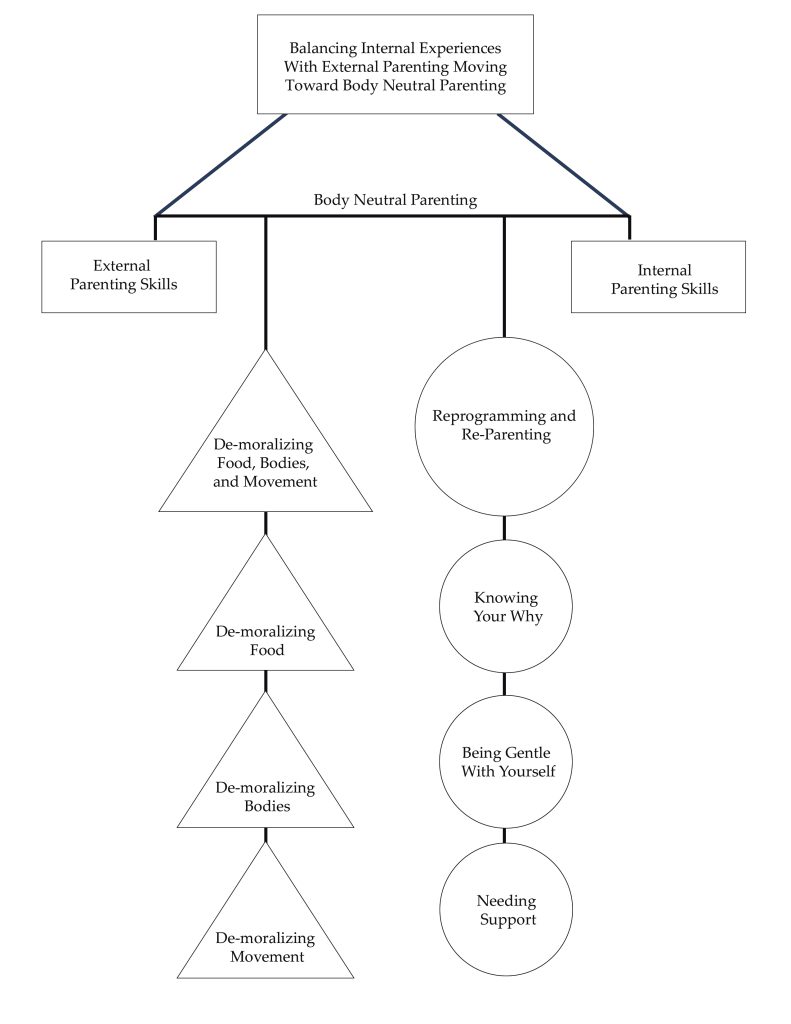

The emergent core category was the balancing of internal experiences with external parenting, moving toward body neutral parenting. The emergent core category captured the essence of the theory—parents integrating body neutrality balance internal experiences (e.g., their own relationship with their bodies and food) with external parenting (e.g., their parenting skills of how to handle food in the household). Figure 1 depicts a conceptual diagram of the body neutral parenting grounded theory. The “mobile” emphasizes the movement and interconnectedness within the body neutral parenting process. At the top of the diagram, there is a seesaw balance between the external parenting skills and internal experiences, processing, and regulating. The internal and external experiences teeter and totter and inform one another as a parent integrates body neutrality. The mobile diagram showcases that if one piece moves, the other pieces move as well. To illustrate, if a parent’s external parenting skills move (e.g., a parent no longer says negative things about their body in front of their children), their internal experiences are impacted (e.g., their own unmet childhood mental health needs related to body image are addressed). The core category of balancing internal experiences with external parenting moving toward body neutral parenting included two categories: (a) De-moralizing Food, Bodies, and Movement, and (b) Reprogramming and Re-Parenting. Each of the two emergent categories has associated subcategories.

De-moralizing Food, Bodies, and Movement

The first category is De-moralizing Food, Bodies, and Movement (n = 10). Within this category, there were three subcategories: De-moralizing Food, De-moralizing Bodies, and De-moralizing Movement. The category embodied acknowledging and countering the large cultural narrative of “good” foods and “bad” foods as well as “good” bodies and “bad” bodies. Participants emphasized the impact of removing the reward and punishment that accompanies the moralization of food, bodies, and movement. As captured by Kimberly, body neutral parenting is about “giving children more of a voice”and trusting them: “When they say that they’re hurt, believing them; when they say that they’re hungry, believing them. Letting them speak for themselves and not speaking for them or for their body. Trusting that they know their body the best.”

Figure 1

Note. This figure showcases the diagram of the body neutral parenting theory. The diagram shows a visual representation of the emergent core category, two categories, and six subcategories and their relationships (Charmaz, 2014).

De-moralizing Food

The first subcategory (n = 10) was De-moralizing Food. Participants consistently noted that food was “one of the biggest” parts of body neutral parenting—specifically, approaching food not as “good” or “bad,” not as “healthy” or “unhealthy,” but simply, neutrally, as “fuel” for the body. Cassie articulated that “A big piece is trying to take the moral piece out of it too. That it’s somehow good to have a certain body or foods are good or bad. Just trying to get away from that.”

The demoralization of food, moving toward neutrality with food, presented in numerous ways across participants’ approaches to caregiving. A primary way in which participants showcased their beliefs about food with regard to body neutrality was to present different foods in a neutral way. For example, the neutral presentation of different foods could look like desserts on the child’s plate from the beginning of the meal, rather than something to be “earned” after eating the “good” foods first. Esmeralda articulated a way in which she demoralized foods and presented them neutrally through what she coined as “Tasting Tuesdays.” She shared:

Instead of making a meal that you serve up in bowls or on plates, you basically charcuterie board the whole meal. . . . I noticed the effect it had on my kids to present a bunch of options, including desserts or traditional treats—it was all presented together. I was laying out all the foods on equal ground, lots of options. And many traditionally unhealthy foods and many traditionally healthy foods just all on the table together. There was no instruction. They just got an empty plate, and they could fill it with whatever they wanted, and I think for them there was some autonomy built into that. They could decide exactly what and how much they wanted to eat off the table. But it also, I think, inspired some adventurousness in them.

Presenting foods neutrally mitigated food judgment, created variety and exposures to food, and met the developmental needs of her children by making mealtime fun.

Another pivotal element of de-moralizing food and moving toward neutrality with food was to create space for children to practice noticing their hunger and fullness cues. Jennifer shared about her experience helping her child learn to trust their body and its cues. She explained:

Trying to trust him and listening to his body, even though he’s 2, and knowing where to intervene and where I shouldn’t intervene. If I make dinner and I put it in front of him and he touches nothing and wants to get down, the way that I was raised was you finish your plate no matter what. Reading everything that I’m reading and trying to move to this neutral space. What I want to say is “At least taste it. At least take a bite. Take one bite. Take three bites.” And what I’m choosing to do is, “Okay, you don’t have to eat right now. We’ll have a bedtime snack later.” I was conditioned to think that first thought.

While not explicitly using the language, participants spoke to helping their children with their hunger, fullness, and satiety cues. Practicing satiety looked like the children being able to say, as Scarlett’s son said, “My body is hungry for ice cream.” Also, Kimberly shared trying to instill autonomy within her children as they learn their hunger, fullness, and satiety cues:

We do defer to them a lot in terms of what they eat or when they’re eating. My daughter wanted canned cooked carrots for breakfast. It was like, well, okay, that’s not maybe socially typical, eating cooked carrots for breakfast. But if that’s what your body wants, go for it. . . . They asked her a question at school when she was graduating from preschool. What would you spend $1,000,000 on? A doughnut. So, it’s like, okay, we’re not going to demonize your doughnuts. You can have your doughnuts when you want your doughnuts.

Here, Kimberly also captured body neutral parenting’s emphasis on avoiding “healthy” vs. “unhealthy” food and other dichotomous language, stemming from diet culture.

Neutral beliefs and behaviors regarding food also manifest via portion sizes for children. Scarlett highlighted differences she noticed in how her family members wanted to portion food for her two sons: one in a larger body and one in a smaller body. She explained that her family members will “offer to my one son and not to the other” while also saying “Oh, do you need that?” to the son in a larger body. Thus, integrating body neutral parenting entails presenting food neutrally, rather than being driven by internalized societal messages about food and thin privilege (e.g., suggesting to a child in a larger body that they may not need the amount of food they are being served perhaps because of anti-fat bias). Body neutral parenting applies for children of all body types.

Moreover, caregivers practicing body neutrality with their children talked about food in a way that emphasizes how it “fuels the body” rather than being about “reward or punishment.” Esmeralda explained:

It’s like you have to basically find a whole new system of rewards. Sweet things are good motivators. They’re reward systems. And they’re also seen as the desirable food after you choke down the “healthy” food . . . these are the “good” foods you have to eat in order to get the “bad” foods that you get rewarded with after dinner. That just is such an insidious concept.

Counter to food being a “reward” or “punishment,” children get to choose rather than falling into the power struggle with food. Cassie described

taking the power out of the food situation. With little kids, everyone thinks like, “Oh, you have to control it and you have to make sure they get vegetables in and all that stuff.” Then it becomes about this power dynamic and just trying to take power out of it and then it is about letting them listen to their body and learn about their body.

Avoiding using food as a reward or as a punishment was integral to the body neutral parenting approach.

De-moralizing Bodies

The second subcategory (n = 9) was De-moralizing Bodies, wherein there are not “good” bodies and “bad” bodies. Leilani described, “In relation to size, shape, behavior, disposition, bad habits . . . everybody’s different.” Body neutral parenting conceptualizes bodies in neutral ways, emphasizing what they help people do. As Cassie explained, “You need food to do the things you want to do, and so we take care of our bodies . . . not to look pretty, but to be able to do—focus more on the doing.” Similarly, Leilani shared,

My go-to approach is to say things like “Everyone’s body is growing at its own pace” and “We have to let our bodies grow at their own pace.” I’m freaked out by stats on how many U.S. girls are dieting around age 10-ish. I’m hoping that my emphasis on letting our bodies do what they need to do will have some impact against pre-teen dieting fads taking hold in our home.

Many participants spoke about their goal for their children of “listening to their bodies.” Kimberly explained, “We tell our children a lot, ‘Listen to your body.’ So, what your body is feeling, what your body is saying, if your body is not hungry anymore, that’s fine. Or if it is hungry.” Further, participants named the impact of modeling, and not modeling, ideals about bodies. To illustrate, Imani explained,

Not talking about other people, that is a huge thing in our family, is just to not talk negatively about people that we don’t know or about people we do know. We don’t talk negatively about our own bodies in front of our kids or anybody else’s body in front of our kids. That’s honestly probably one of the more impactful things that we do.

Kimberly, too, emphasized being mindful of modeling how to think and talk about bodies:

Making sure that we model kindness to our bodies in front of them as well. So not saying things that are self-deprecating about the way that we look. Making sure that our children don’t hear us saying, “Oh my gosh, I’m just so fat,” those kinds of messages.

Also, participants emphasized integrating body neutrality into clothing approaches with their children. Scarlett described being mindful of the language she uses regarding clothes and bodies: “You’re too big for that versus those clothes don’t fit your body, or you’re too small for that versus that doesn’t really look like it’s comfortable on your body. Let’s find something that works best for you.”

De-moralizing Movement

The last subcategory (n = 7) was De-moralizing Movement, which included engaging in movement for fun and being mindful of how we speak about exercise. Imani explained:

And so I think that for us, we really try to keep those things [exercise, body image, and food] disconnected. If you’re doing gymnastics, it’s because you’re interested in it and you think it’s a fun thing, not because it’s going to impact your body, not because you know it’s going to make you thin. It’s because you think it’s fun.

Cassie conceptualized movement as being fun, not for compensation, as well: “Being excited about things our bodies are doing and not just kind of the emphasis on like, well, if it’s fun, let’s do it. But if it’s not fun, then we’re not going to push ourselves or torture ourselves.” Moreover, Scarlett emphasized the importance of being conscientious of language used to describe her children’s bodies:

How big they are. We use that term especially with male children. But you are such a big boy is always the thing. You’re such a big boy . . . instead trying to just say things like, “Oh, hey, that’s really awesome that you can do X, Y, and Z.” Trying to make it very concrete, it’s very cool that your body allows you to run around and play.

When it came to De-moralizing Food, Bodies, and Movement, a theme of removing the “shoulds” prevailed across participants. Kimberly described trying to “stay neutral with foods so that we don’t end up so much down the should line of what they should be eating or what they should be doing in terms of physical activity or those kinds of things.” Taking out the “should” entailed avoiding dictating what children “should be eating, “should look like,” or how they “should be exercising.” In summary, as poignantly articulated by Logan, “just focusing on the objectivity of what’s there without having the positive or negative associations.”

Reprogramming and Re-Parenting

The second category (n = 10) was Reprogramming and Re-Parenting. Beyond the skills of body neutral parenting, a key tenet of the approach was ample self-reflection. Caregivers engaged in deep reflection of their own relationship with food, their body, and movement while supporting their children in their body image development. The self-reflection process entailed identifying, rewiring, and, often, re-parenting oneself through the sociocultural messages that have permeated one’s life span. Scarlett shared that body neutral parenting “makes me reflect on myself and why I’m saying the things I’m saying and why I feel the way I’m feeling.” Subcategories of Reprogramming and Re-Parenting included: Knowing Your Why, Being Gentle With Yourself, and Needing Support.

To illustrate, Leilani increased her awareness of her history with disordered eating and exercising for compensation and shared the impact her daughter has had on rewiring her way of thinking:

If I had a child who was very thin, it would have reinforced that dysfunction for me, because then I’m someone who produced a very thin child, and that makes me even better. . . . And then when you have a kid who’s really big and she’s pretty chubby, that you have to make such a hard shift to undo. Being the skinniest person in the room isn’t your greatest value in life and really reestablishing that personal value system. That’s been a massive kind of change for me.

This is a tangible example of the rewiring that happened for Leilani, though all of the parents spoke to their rewiring process and need to re-parent themselves alongside their children.

Knowing Your Why

The first subcategory (n = 10) of Reprogramming and Re-Parenting was Knowing Your Why. Participants acknowledged the value they put into the parenting approach. Jennifer captured common collective values of body neutral parenting when she shared:

Number one, reducing shame. Number two, increasing quality of life and self-confidence . . . that would probably eventually help with any mental health issues or any relationship issues because he’ll have the self-confidence to say where his boundaries are and trust his body. And at the same time listen to other people and be empathetic.

Similarly, Kimberly emphasized how much it means to be parenting without shame: “I love that we know we’re not parenting with shame . . . as the hidden motivator. That’s why you don’t eat that extra food you might be hungry for.”

A significant challenge for many participants was the “internalized messaging” they experienced regarding their body image, food, and movement. Almost all of the participants (n = 8) directly spoke to their experiences with an eating disorder or disordered eating driving their desire to parent from a body neutral stance. Cassie, for example, cited her eating disorder recovery as sparking her passion for body neutral parenting:

Right when my husband and I got married, I went into treatment for an eating disorder, and so that shaped me a lot. . . . I was using all of the things that I had learned and trying to really instill it in them. How we talk about food, how we talk about bodies. It was such an integral part of my parenting.

Being Gentle With Yourself

The second subcategory was Being Gentle With Yourself. Each participant (n = 10) criticized themselves in some fashion about not perfectly integrating body neutrality into their parenting approach. They were quick to highlight their failures and slow to honor their successes. Body neutral parenting, given its emphasis on countering long-standing sociocultural messaging, requires offering oneself a great deal of grace. Body neutral parenting entails tremendous learning, and that learning starts with reminding caregivers that they are doing the best that they can with the knowledge, support, and resources that they have. Imani spoke to how she navigated thoughts from these internalized messages and filtered them:

I think about things like, “She’s thinning out.” . . . It’s so ingrained, it’s hard not to think those things. And so then even if that’s something that goes across my mind or I think about the things that they’re eating and how that might impact their body or their physical health, just stopping that conversation with me and not actually talking about that with them, it’s not something that they need to hear. So, I think that it’s just as much what we don’t say as much as what we do say to them.

Having thoughts stemming from diet culture and stumbling and saying the “wrong” thing is inevitable when rewiring these deeply embedded messages. Not only are those moments of “messing up” normal, but they also create space for beautiful moments to repair. Scarlett explained her process of repairing the inevitable ruptures:

Which all sounds well and good and wonderful until you are running around with a 4-year-old and a 5-year-old on your day to day. I will also balance that, it’s also trying to catch myself when I say things that I’ve just internalized from society in my own childhood and being like, “Hey, isn’t that interesting.” Just talking out loud to them. Saying, “Isn’t it interesting that I said X, Y, and Z? Is that really maybe the best way to talk about our bodies?” Trying to just be reflective and knowing that I’m not always going to be body neutral but trying to be intentional about noticing when I’m not.

The participants reflected that parenting is an imperfect, human process.

Needing Support

The third subcategory was Needing Support. All of the caregivers in the study (n = 10) spoke to the importance of feeling support in their parenting approach. Support looked different for each family; some received support through social media, and others described finding support from their partner or other like-minded caregivers. Every participant described the role that social media had in their body neutral parenting approach. Many described learning about the approach via social media and experiencing continued support through certain social media pages. For example, common social media pages referenced by participants included Feeding Littles, Our Mama Village, Dr. Becky, and Kids Eat in Color. Most participants recommended that caregivers interested in starting body neutral parenting seek out social media for knowledge and support.

Additionally, participants emphasized the importance of being on the same page with other primary caregivers. Consistently, participants accentuated the need to talk through how to navigate situations in advance, to be on the same page for how to handle them. To illustrate, Scarlett described how to navigate their child “wanting ice cream after not eating all of their dinner” and how she and her partner talked through how to approach that situation. Esmeralda emphasized a need for support that she felt she was not getting:

I don’t think I’ve really found a group of parents or moms where we can talk through these things or troubleshoot together. I feel like I’m a consumer of some social media on the topic, and then I’m just sort of alone.

Feeling supported appeared to be integral to body neutral parenting.

Discussion

This co-created grounded theory on body neutral parenting is a valuable addition to the literature, given the gaps in understanding how counselors can help guardians support healthy body image amongst children (Klassen, 2017). Given the significant familial influence on body image development, counselors can consider this study’s findings through a preventative lens (Liechty et al., 2016). The findings align with the scant literature on body neutrality, suggesting the need for continued exploration of how to support children, adolescents, and their families in their conceptualizations of body, food, and movement (Gutin, 2021). Mental health counselors can consider body neutral parenting as an avenue to foster positive familial influence in body image development. Positive familial influence on body image and related self-worth can prevent disordered eating, negative body image, and low self-worth (Veldhuis et al., 2020). Thus, body neutral parenting appears to have the potential to have significant impact on the mental health and self-efficacy of children, as well as their caregivers.

Based on the findings of this study, critical tenets of body neutral parenting include de-moralizing food, bodies, and movement, and reprogramming and re-parenting. The co-created parenting theory constructed in this study can be utilized as a way of conceptualizing a parenting practice that facilitates healthy body image development for families. Specifically, counselors can help families learn that food is not “healthy” or “unhealthy” and there are not “good” or “bad” bodies. In addition, the co-created theory emphasizes the need for counselors to help family members heal from internalized messages and misconceptions about health that can perpetuate body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating across generations.

Implications for Counselors and Caregivers

Counselors and caregivers are uniquely positioned to use the findings of this study to inform how they support children and their body image development. In this study, parents offered their approach to integrating body neutral parenting with their children. The co-created theory of body neutral parenting offers a baseline for counselors and parents to consider, and future research on the theory is needed. Thus, counselors and parents can consider learning about body neutrality and integrating the principles in supporting the mental health of families.

Counselors

Body neutral parenting gives families and counselors alike a framework of how to navigate conversations of body, food, and movement to promote a healthy relationship with body image. Families need the language, including specific scripts of what to say and do, and what to avoid saying and doing, to support their children in their body image development. It appears that many families would be interested in shifting the larger sociocultural narrative, including diet culture, with their approach to raising their children, if they had the appropriate psychoeducation and support (Siegel et al., 2021). Clinical mental health counselors can meet that need. The co-created grounded theory in this study and further research can provide a launching pad for counselors who want to take a more preventative approach to body image and related mental health support for youth. Counselors can teach families about de-moralizing food, bodies, and movement in their household, for example, as part of the counseling process for children and adolescents who are at risk for disordered eating and body image concerns.

Counselors can consider how to be of support to families with an interest in integrating body neutrality into their childrearing approach. Mental health professionals can consider how to be of support through the arduous, though meaningful, process of simultaneously parenting one’s children and re-parenting oneself. Some ways in which mental health counselors can support families include normalizing and validating how difficult body neutrality can be and offering specific scripts of what to avoid saying and what to say instead. To illustrate, a counselor might provide psychoeducation to a parent on how to talk to their child about food. Rather than saying “Apples are good for you,” the caregiver could say, “Red food gives you a strong heart” (Kids Eat in Color, 2022). Moreover, families will need support as they navigate the tremendous amount of rewiring involved for body neutral parenting. Counselors can keep in mind the larger overarching goal to drive their clinical decisions in supporting families through body neutral parenting and avoid the negative experience of shame (Ruckstaetter et al., 2017). Counselors can support families in realizing that parenting is an imperfect, human process. Reminding caregivers that imperfect moments will happen, and how to be gentle with themselves, is critical for caregivers continuing the body neutral lifestyle.

As practicing counselors, we must engage in deep reflective practice ourselves to support families and children with body neutrality. In order to be culturally responsive and meet the needs of diverse families, we must “gain knowledge, personal awareness, sensitivity, dispositions, and skills” specific to body neutrality (ACA, 2014, C.2.a). All people have internalized messages and “shoulds” about food, bodies, and exercise, and those internalized biases can hinder the counselor’s ability to support the intricate needs of diverse families healing their relationships with food, bodies, and exercise. Thus, it is an ethical imperative for counselors to engage in self-reflective work about their internalized messages and how those biases might impact the body image needs of children. To illustrate, a counselor might have thin privilege and internalized messages of fat phobia and unknowingly perpetuate the social justice issue of sizeism. Similarly, a parent might make negative comments about the larger body individuals on a TV show. When working with a client in a larger body, a counselor might congratulate the client on their weight loss, when the client might actually be struggling with restricting food and exercising for compensation. It remains an ethical and social justice requirement to engage in both self-reflective work and learning new skills, such as de-moralizing food, to be a culturally responsive, ethical counselor.

Parents and Caregivers

Relatedly, parents and caregivers can consider body neutrality when supporting their children with their body image development. For example, parents might consider the findings of this study and consider what de-moralizing food, bodies, and movement might look like in their home as well as reflect on their own healing process related to reprogramming and re-parenting. Parents might first identify how they engage in power struggles with food; use food as a reward; or use moralized language around food, bodies, and movement. Then, they might work toward identified areas for growth that can help move toward a more neutral relationship with food, bodies, and movement in their home.

Parents might be intentional about their use of language related to food, bodies, and movement with their children. For example, parents might avoid using the terms “healthy” and “unhealthy” related to food, but rather, emphasize the nutrients in the food, how the body feels after food, and other concepts congruent with intuitive and mindful eating. Further, in this study, many parents prefer the term “movement” over “exercise,” as it more accurately captures the relationship with moving the body. “Exercise” has a connotation for many clients as being punitive, exhausting, or for compensation, as opposed to “movement” embodying the mindful moving of the body for fun concepts aligned with body neutrality. In addition to language considerations, parents might consider how they maneuver mealtimes and integrate suggestions from the findings of this study, such as offering sweet foods at the same time as the meal, rather than having the dessert afterward as something to be earned.

Parents might also engage in their own healing and reflective practices, such as identifying their own food rules and reprogramming their internalized messages about food. Parents can model body neutrality with their own body by avoiding negative body talk, such as “I am so fat” or “I am bad for eating that, now I need to walk off those calories,” and replacing those comments with more body neutral statements. Similarly, caregivers can be mindful of how they talk about others’ bodies, such as avoiding negative comments about the larger body individuals on a TV show. Examples of body neutral statements might be: “My body is hungry for” and “I love that my body allows me to give you big hugs.”

Limitations

The sampling procedure is a limitation of this study. Onwuegbuzie and Collins (2007) suggested an ideal sample size between 12 and 15 for a grounded theory investigation using interviews. Although the study met theoretical saturation, the sample size was slightly under some recommended sources for a grounded theory investigation with 10 interviews. Moreover, although attempts were made to have a diverse sample and a geographically diverse sample was acquired, the study primarily captured the experiences of highly educated, middle-class mothers.

In addition, another primary limitation is the self-report from parents. Although parents self-reported as enacting body neutral parenting practices, I did not confirm if their self-report aligned with their actual parenting practices. As such, this study was not able to confirm how or in what way the participants’ parenting was effective. Moreover, research has not yet confirmed that body neutral parenting practices are helpful for children, necessitating further outcome research.

Future Research

Future studies could cast a more comprehensive, representative net and capture the experiences of other caregivers of more diverse gender, socioeconomic, and educational backgrounds. Researchers could explore the nuances of caregivers integrating body neutrality into their approach caring for their children, such as specific developmental considerations. Research exploring current counseling practices, including how counselors support families through body neutral parenting, would also be a helpful addition to a scant literature base.

Conclusion

This study uncovered body neutral practices that caregivers and mental health professionals alike can use to support the body image development of children and adolescents. In particular, findings emphasized the importance of the caregiver’s reflective work and de-moralizing food, bodies, and movement. Body neutrality as an approach to parenting appears to underpin the healthy development of body image and related self-esteem in children and adolescents.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Abraczinskas, M., Fisak, B., Jr., & Barnes, R. D. (2012). The relation between parental influence, body image, and eating behaviors in a nonclinical female sample. Body Image, 9(1), 93–100.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.10.005

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/Resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Charmaz, K., & Liska Belgrave, L. (2012). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, & K. D. McKinney (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (2nd ed., pp. 347–365). SAGE.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

Damiano, S. R., Gregg, K. J., Spiel, E. C., McLean, S. A., Wertheim, E. H., & Paxton, S. J. (2015). Relationships between body size attitudes and body image of 4-year-old boys and girls, and attitudes of their fathers and mothers. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0048-0

Damiano, S. R., McLean, S. A., Nguyen, L., Yager, Z., & Paxton, S. J. (2020). Do we cause harm? Understanding the impact of research with young children about their body image. Body Image, 34, 59–66.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.05.008

Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., & Ive, S. (2006). Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283

Gutin, I. (2021). Body mass index is just a number: Conflating riskiness and unhealthiness in discourse on body size. Sociology of Health & Illness, 43(6), 1437–1453. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13309

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12365

Herle, M., De Stavola, B., Hübel, C., Abdulkadir, M., Ferreira, D. S., Loos, R. J. F., Bryant-Waugh, R., Bulik, C. M., & Micali, N. (2020). A longitudinal study of eating behaviours in childhood and later eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(2), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.174

Horton, E. (2023). “I want different for my child”: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of mothers’ histories of disordered eating and the impact on their parenting approach. The Family Journal, 31(2), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807221151171

Horton, E., & Powers, M. (2024). Demoralizing food, bodies, and movement: A phenomenological exploration of caregivers’ experience in a body neutral parenting support group. The Family Journal.

https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807231226232

Khanal, K. P. (2018). Constructivist grounded theory practice in accountability research. Journal of Education and Research, 8(1), 61–88. https://doi.org/10.3126/jer.v8i1.25480

Kids Eat in Color [@kids.eat.in.color]. (2022, April 21). How to talk: May not help, may help a lot [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ccnn7CMr2D5/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Klassen, S. (2017). Free to be: Developing a mindfulness-based eating disorder prevention program for preteens. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 3(2), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2017.1294918

Kluck, A. S. (2010). Family influence on disordered eating: The role of body image dissatisfaction. Body Image, 7(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.009

Liechty, J. M., Clarke, S., Birky, J. P., & Harrison, K. (2016). Perceptions of early body image socialization in families: Exploring knowledge, beliefs, and strategies among mothers of preschoolers. Body Image, 19, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.010

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2006). The development of constructivist grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500103

National Eating Disorders Association. (2022). Body image. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/body-image

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Bauer, K. W., Friend, S., Hannan, P. J., Story, M., & Berge, J. M. (2010). Family weight talk and dieting: How much do they matter for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors in adolescent girls? Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(3), 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.001

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Collins, K. M. T. (2007). A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report, 12(2), 281–316. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2007.1638

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. SAGE.

Pellizzer, M. L., & Wade, T. D. (2023). Developing a definition of body neutrality and strategies for an intervention. Body Image, 46, 434–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2023.07.006

Perry, M., Watson, L., Hayden, L., & Inwards-Breland, D. (2019). Using body neutrality to inform eating disorder management in a gender diverse world. Child and Adolescent Health, 3(9), 597–598.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(19)30237-8

Phares, V., Steinberg, A. R., & Thompson, J. K. (2004). Gender differences in peer and parental influences: Body image disturbance, self-worth, and psychological functioning in preadolescent children. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(5), 421–429. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000037634.18749.20

Pursey, K. M., Burrows, T. L., Barker, D., Hart, M., & Paxton, S. J. (2021). Disordered eating, body image concerns, and weight control behaviors in primary school aged children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of universal–selective prevention interventions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(10), 1730–1765. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23571

Ricciardelli, L. A., McCabe, M. P., & Banfield, S. (2000). Body image and body change methods in adolescent boys: Role of parents, friends and the media. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49(3), 189–197.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00159-8

Rodgers, R., & Chabrol, H. (2009). Parental attitudes, body image disturbance and disordered eating amongst adolescents and young adults: A review. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.907

Ruckstaetter, J., Sells, J., Newmeyer, M. D., & Zink, D. (2017). Parental apologies, empathy, shame, guilt, and attachment: A path analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(4), 389–400.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12154

Sharpe, H., Patalay, P., Choo, T.-H., Wall, M., Mason, S. M., Goldschmidt, A. B., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2018). Bidirectional associations between body dissatisfaction and depressive symptoms from adolescence through early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 30(4), 1447–1458. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417001663

Siegel, J. A., Ramseyer Winter, V., & Cook, M. (2021). “It really presents a struggle for females, especially my little girl”: Exploring fathers’ experiences discussing body image with their young daughters. Body Image, 36, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.11.001

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance (1st ed.). American Psychological Association.

https://doi.org/10.1037/10312-000

Veldhuis, J., Alleva, J. M., Bij de Vaate, A. J. D., Keijer, M., & Konijn, E. A. (2020). Me, my selfie, and I: The relations between selfie behaviors, body image, self-objectification, and self-esteem in young women. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000206

Walker, D. C., Gorrell, S., Hildebrandt, T., & Anderson, D. A. (2021). Consequences of repeated critical versus neutral body checking in women with high shape or weight concern. Behavior Therapy, 52(4), 830–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.10.005

Wymer, B., Swartz, M. R., Boyd, L., Zankman, M., & Swisher, S. (2022). A content analysis of empirical parent engagement literature. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 8(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2022.2037987

Emily Horton, PhD, LPC, RPT, is an assistant professor at the University of Houston–Clear Lake. Correspondence may be addressed to Emily Horton, 2700 Bay Area Boulevard, Houston, TX 77058, horton@uhcl.edu.