Sep 13, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 2

Matthew Peck, Diana M. Doumas, Aida Midgett

Researchers have utilized the Bystander Intervention Model to conceptualize bullying bystander behavior. The five-step model includes Notice the Event, Interpret the Event as an Emergency, Accept Responsibility, Know How to Act, and Decision to Intervene. The purpose of this study was to examine outcomes of an evidence-based bystander training within the context of the Bystander Intervention Model among middle school students (N = 79). We used a quasi-experimental design to examine differences in outcomes between bystanders and non-bystanders. We also assessed which of the steps were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior. Results indicated a significant increase in Know How to Act for both groups. In contrast, we found increases in Notice the Event, Decision to Intervene, and defending behavior among bystanders only. Finally, Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior. We discuss implications of these findings for counselors.

Keywords: Bystander Intervention Model, bullying, bystander training, defending behavior, middle school

School bullying is a significant problem in the United States, with one out of four students reporting being a target of bullying (U.S. Department of Education, 2019). Bullying is defined as any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths, who are not siblings or currently dating, that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance, and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). Bullying peaks in middle school, with 28% of middle school students reporting being a target of school bullying (CDC, 2020). According to a meta-analysis examining consequences of bullying victimization, among middle school students, targets of bullying reported a wide range of socio-emotional consequences, including anxiety, post-traumatic stress, depressive symptoms, poor mental and general health, non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Moore et al., 2017). Researchers have also established mental health risks associated with witnessing bullying among middle school students, including anxiety and depressive symptoms (Doumas & Midgett, 2021; Midgett & Doumas, 2019).

The Role of Bystanders

The majority of students (80%) have reported observing bullying as a bystander (Wu et al., 2016). A bystander is a student who witnesses a bullying situation but is not the target or the perpetrator (Twemlow et al., 2004). Bystanders can respond to bullying in several ways, including encouraging the bully by directly acting as “assistants” or indirectly acting as “reinforcers,” walking away from bullying situations acting as “outsiders,” or attempting to intervene to help the target by acting as “defenders” (Salmivalli et al., 1996). As such, bystanders play an important role in inhibiting or exacerbating bullying situations. Although most students intentionally or unintentionally reinforce bullying by acting as “assistants,” “reinforcers,” or “outsiders” (Salmivalli & Voeten, 2004), a single high-status student or group of students acting as “defenders” can shift attention and power away from the perpetrator (Salmivalli et al., 2011), thereby discontinuing reinforcement, modeling prosocial behavior, and providing social support for targets. Thus, there is a need to train bystanders to intervene to both reduce bullying and buffer both bystanders and targets from the negative consequences associated with witnessing bullying.

Researchers have found that mobilizing bystanders to intervene to stop bullying is an important part of bullying prevention (Polanin et al., 2012). Bullying decreases when bystanders intervene as “defenders” (Salmivalli et al., 2011); however, many students reported they lack the skills to intervene (Bauman et al., 2020) and only 20% reported using defending behavior when they witness bullying (Salmivalli et al., 2005). Researchers investigating bullying bystander behavior have identified factors associated with defending targets, including perceived pressure to intervene (Porter & Smith-Adcock, 2016), basic moral sensitivity to bullying (Thornberg & Jungert, 2013), self-efficacy (Thornberg & Jungert, 2013; van der Ploeg et al., 2017), and empathy (van der Ploeg et al., 2017). However, these studies have focused primarily on one or two specific factors in relation to defending, rather than the process that leads to defending behavior. Because bullying involves many interacting factors, a comprehensive model is needed to understand the complex social behavior of bystander intervention in bullying.

The Bystander Intervention Model

The Bystander Intervention Model (Latané & Darley, 1970) provides a conceptual framework of necessary conditions for bystanders to intervene to help targets of bullying. This model outlines five sequential steps that a bystander must undergo in order to take action: (a) notice the event, (b) interpret the event as an emergency that requires help, (c) accept responsibility for intervening, (d) know how to intervene or provide help, and (e) implement intervention decisions. Nickerson and colleagues (2014) developed a measure, the Bystander Intervention Model in Bullying Questionnaire, as a way to assess the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model in bullying and sexual harassment situations among high school students. Results of structural equation modeling analyses revealed a good model fit, with engagement in each step of the Bystander Intervention Model being influenced by engagement in the previous step, providing a measurement model that can inform bullying intervention efforts. Researchers have also examined an adapted version of the Bystander Intervention Model in Bullying Questionnaire for middle school students, with confirmatory factor analysis supporting the five-step model and demonstrating positive correlations between engagement in each step of the Bystander Intervention Model and defending behavior in bullying situations (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). Applying the Bystander Intervention Model to school-based bullying prevention programs can inform program development and evaluation, with the goal of helping counselors understand how to equip students with skills to engage in all steps of the model, enhancing program outcomes through an increase in defending behavior. To date, however, no researchers have examined bystander training within the context of the Bystander Intervention Model.

The STAC Intervention

STAC (Midgett et al., 2015), which stands for four bystander intervention strategies—Stealing the Show, Turning It Over, Accompanying Others, and Coaching Compassion—is a brief bullying bystander intervention. The program is designed to provide education about bullying, including the definition of bullying and its negative associated consequences; emphasize the importance of intervening in bullying situations; and teach students prosocial skills they can use to intervene as a “defender” when they witness bullying. As a school-based program, STAC was developed to be delivered by school counselors during classroom lessons (Midgett et al., 2015). Research indicates STAC is effective in reducing bullying victimization (Moran et al., 2019) and bullying perpetration (Midgett et al., 2020; Moran et al., 2019) among middle school students. Additionally, researchers have found that middle school students trained in the STAC program reported a decrease in depressive symptoms (Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett et al., 2020), social anxiety (Midgett & Doumas, 2020), and passive suicide ideation (Midgett et al., 2020), while also experiencing a positive sense of self after implementing the STAC strategies (Midgett, Moody, et al., 2017).

Alignment Between the Bystander Intervention Model and the STAC Intervention

The STAC intervention includes didactic and experiential components that are aligned with the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model. First, the facilitators of the STAC program provide education about bullying, what it is and what it is not, and the negative associated consequences of bullying. This information can promote student engagement in the first two steps of the Bystander Intervention Model (i.e., Notice the Event and Interpret the Event as an Emergency). Next, facilitators of the STAC program emphasize the importance of intervening in bullying situations, which can promote student engagement in the third step of the Bystander Intervention Model (i.e., Accept Responsibility). Finally, facilitators of the STAC program train students to use prosocial skills they can use as bystanders to intervene as a “defender” when they witness bullying. The program also includes skills practice for strategy implementation through role-play activities and booster sessions. Skills training and practice are aligned with the last two steps of the Bystander Intervention Model (i.e., Know How to Intervene and Decision to Intervene). Although research indicates that middle school students trained in the STAC program report increases in knowledge and confidence (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett, Doumas, et al., 2017; Moran et al., 2019) and use of the STAC strategies post-training (Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Moran et al., 2019), to date, no research has examined the impact of the STAC intervention on student engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model or how engagement in the five steps is related to post–STAC training defending behavior.

The Present Study

The purpose of this study is to expand the literature by examining changes in engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model among middle school students. First, using a quasi-experimental design, we aim to examine changes in engagement between bystanders and non-bystanders. We also aim to assess which of the five steps are associated with post-training defending behavior. Researchers have demonstrated that each of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model correlates with defending behavior among middle school students (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). To date, however, no study has examined if bystander training increases engagement in the five steps of the model and if the five steps are related to defending behavior after bystander training. The STAC bystander intervention teaches bystanders to act as defenders by providing education about bullying and equipping students with the knowledge and skills to intervene in bullying situations (Midgett et al., 2015). To date, however, no researchers have examined the impact of the STAC intervention on student engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model or how engagement in the five steps is related to defending behavior after bystander training. To address this gap, we used a quasi-experimental design to answer the following research questions:

Research Question 1: Are there differences in student engagement in the five steps of the

Bystander Intervention Model from baseline (T1) to the 6-week

follow-up (T2) between bystanders and non-bystanders?

Research Question 2: Is there a difference in defending behavior from baseline (T1) to the

6-week follow-up (T2) between bystanders and non-bystanders?

Research Question 3: Engagement in which of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention

Model uniquely predicts defending behavior at the 6-week follow-up (T2)?

Methods

Participants

The sampling frame for recruitment included all students in grades 6–8 at a single private school in the Northwest. The school had a total enrollment of 362 students in grades K–8, with a student body comprised of 80% of students identifying as White, 14% Hispanic, 3% Two or More Races, 1% Asian American, 1% Black/African American, and < 1% Native American or Native Hawaiian. The researchers invited all students in grades 6–8 to participate (N = 127). Inclusion criteria included being enrolled in sixth, seventh, or eighth grade; speaking and reading English; and having parental consent and student assent to participate. Exclusion criteria included inability to speak or read English and not having parental consent or not assenting to participate. Of the 127 students invited, 90 (70.9%) parents/guardians provided informed consent and 87 students (68.5%) assented to participate; 79 of those students (90.8%) completed the 6-week (T2) follow-up assessment. Among participants, 62.1% self-identified as female and 37.9% self-identified as male. Participant age ranged from 11–14 years (M = 12.22 and SD = 0.92), with reported race/ethnicity of 63.3% White, 8.9% Hispanic, 2.5% Black/African American, 3.8% Asian American, 15.2% Two or More Races, and 6.3% Other. There were no differences in gender, c2(1) = .01, p = .98; grade, c2(2) = .61, p = .74; race/ethnicity, c2(5) = 4.41, p = .49; or age, t (85) = .41, p = .52, between students who completed the follow-up assessment and those who did not.

Procedure

The university IRB approved all study procedures. A member of our research team explained the purpose of the training and study procedures to all students during classtime, invited students to participate, and provided students with an informed consent form to take home to parents/guardians. Immediately prior to collecting baseline data (T1), our team members collected assent forms from students who had a signed informed consent form. Our team members conducted the STAC training in two 45-minute modules, followed by two weekly 15-minute booster sessions. Students completed a 6-week follow-up survey (T2). Trainers conducted the STAC intervention through six groups (two per grade level) ranging from 20–30 students per group. All students participated in the training; however, only those with informed consent and assent participated in the data collection. All procedures occurred during classroom time.

The STAC Program

Didactic Component. In the STAC program, trainers present educational information that includes (a) an overview of bullying; (b) different types of bullying (i.e., physical, verbal, relational, and cyberbullying); (c) characteristics of students who bully; (d) reasons students bully; (e) negative consequences associated with being a target, perpetrator, and/or bystander; (f) the role of the bystander and the importance of acting as a “defender”; (g) perceived barriers for intervening; and (h) the STAC strategies described below.

Stealing the Show. “Stealing the show” is a strategy aimed at interrupting a bullying situation by using humor, storytelling, or other forms of distraction to get the attention off of the bullying situation and the target. Students learn how to identify bullying situations that are appropriate to intervene in using this strategy. Students are trained not to use “stealing the show” to intervene during physical or cyberbullying.

Turning It Over. “Turning it over” involves seeking out a trusted adult to intervene in difficult bullying situations. Students learn how to identify bullying situations that require adult intervention, specifically physical bullying, cyberbullying, and/or any bullying situation they do not feel comfortable intervening in directly.

Accompanying Others. “Accompanying others” is a strategy aimed at offering support to the target of bullying. Students learn to comfort targets either directly by asking them if they would like to talk about the incident or indirectly by spending time with them.

Coaching Compassion. “Coaching compassion” is a strategy aimed at helping the perpetrator of bullying to develop empathy for students who are targets. Students learn to safely and gently confront those who are perpetrators by engaging them in a conversation about the impacts of bullying and communicating that bullying behavior is never acceptable. Trainers teach students to use this strategy only when they are friends with the perpetrator, are older than the perpetrator, or believe they have higher social status and will be respected by the perpetrator.

Experiential Component. Students participate in small group role-plays to practice each of the four STAC strategies across varying bullying scenarios. These scenarios include different types of bullying, such as spreading rumors, verbal and physical bullying, and cyberbullying. Each small group presents a role-play to the larger group and trainers provide both positive and constructive feedback to help students use the strategy more effectively in the future.

Booster Sessions. Students participate in two booster sessions to reinforce learning and skill acquisition. During the booster session, trainers review the STAC strategies, encourage students to share their experiences using the strategies, and brainstorm ways to help students be more effective defenders. The trainers invite students to share bullying situations that they have observed, including those in which they did not intervene, and then brainstorm with other students how they could intervene in the future.

Intervention Fidelity. The developer of STAC trained the trainers previously, and both trainers had experience delivering the STAC intervention prior to this study. The first author, Matthew Peck, served as one of two trainers during the intervention training used in this study; the other was a graduate student not involved in the later development of this article. The third author, Aida Midgett, was present during the training to ensure it was delivered with fidelity. Midgett completed a dichotomous rating scale (Yes or No) to evaluate whether the trainers accurately taught the material and whether they deviated from the intervention protocol, and determined that the trainers delivered the STAC training with high levels of fidelity.

Measures

Demographic Survey

Participants completed a demographic survey including questions about gender, grade, age, and race/ethnicity. Participants indicated their gender, grade, and age through open-ended questions and provided their race/ethnicity through response choices.

Bystander Intervention Model Steps

We assessed the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model using the 16-item Bystander Intervention in Bullying Questionnaire (Nickerson et al., 2014). The original scale was developed for high school students and focused on bullying and sexual harassment. Jenkins and Nickerson (2016) adapted the scale for middle school students to focus on bullying only. The questionnaire is comprised of five scales: Notice the Event (3 items), Interpret the Event as an Emergency (3 items), Accept Responsibility (3 items), Know How to Act (3 items), and Decision to Intervene (4 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example items include: “I am aware that students at my school are bullied” (Notice), “I think bullying is hurtful and damaging to others” (Interpret), “I feel personally responsible to intervene and assist in resolving bullying incidents” (Accept), “I have the skills to support a student who is being treated disrespectfully” (Know), and “I would say something to a student who is acting mean or disrespectful to a more vulnerable student” (Intervene). Confirmatory factor analyses support the five-factor structure, and convergent validity analyses using the Defending subscale of the Bullying Participant Behaviors Questionnaire (Summers & Demaray, 2008) has been demonstrated by providing positive correlations ranging from .26 to .35 among middle school students (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). Researchers have also demonstrated high internal consistency for the subscales among middle school students, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .77 to .87 for the five subscales (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016). For the current sample, the scales had acceptable internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .66 to .71. For the Interpret subscale, we deleted one item (i.e., “It is evident to me that someone who is being bullied needs help”) to reach an acceptable level of internal consistency (α = .66) for the scale.

Defending Behavior

We utilized the 3-item Defender subscale of the Participants Roles Questionnaire (PRQ; Salmivalli et al., 2005) to measure defending behaviors students may use to intervene when witnessing bullying. The subscale includes the following items: “I comfort the victim or encourage him/her to tell the teacher about the bullying,” “I tell the others to stop bullying,” and “I try to make the others stop bullying.” Items are rated on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 2 (often). Confirmatory factor analyses support the five-factor structure of the PRQ measure, and construct validity has been demonstrated through significant associations between self-reported roles and sociometric status (e.g., popular, rejected, and average), χ2 = 117.7–141.6, all p values < .001, and peer nominations, χ2 = 57.9–88.2, all p values < .001 (Goossens et al., 2006). Among middle school students, the Defender subscale has good internal reliability ranging from α = .79–.93 (Camodeca & Goossens, 2005; Salmivalli et al., 2005). For

the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was high (α = .80).

Bystander Status

We assessed bystander status by asking participants, “Have you seen bullying at school in the past month?” with response choices Yes and No. The item was developed by the second author, Diana M. Doumas, to assess whether or not students had the opportunity to respond to a bullying incident. Students who reported Yes were classified as bystanders (i.e., the student witnessed bullying and had the opportunity to respond) and students who reported No were classified as non-bystanders (i.e., students who did not witness bullying and, therefore, did not have the opportunity to respond). The item has face validity and researchers have utilized this item previously to measure bystander status among middle school students (Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Moran et al., 2019). In this study, the 30.4% of students who reported Yes to this item at the follow-up assessment (T2) were classified as bystanders, and the 59.6% of students who reported No were classified as non-bystanders.

Data Analyses

We conducted all analyses using SPSS version 28.0. We imputed missing data and examined all variables for skew and kurtosis. We used a general linear model (GLM) repeated measures multivariate analyses of covariance (RM-MANCOVA) to examine changes in engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model between bystanders and non-bystanders across time for the outcome variables Notice the Event, Interpret the Event as an Emergency, Accept Responsibility, Know How to Act, and Decision to Intervene. The independent variables were Time (baseline [T1]; follow-up [T2]) and Bystander Status (bystander; non-bystander). We also controlled for gender, age, and witnessing bullying at baseline. We conducted post-hoc GLM repeated measures analyses of covariance (RM-ANCOVAs) for each outcome variable. We plotted simple slopes to examine the direction and degree of the significant interactions testing moderator effects (Aiken & West, 1991). We only interpreted significant main effects in the absence of significant interaction effects. For changes in defending behavior, we used a GLM RM-ANCOVA. The independent variables and control variables paralleled the RM-MANCOVA analysis. We conducted a linear multiple regression to examine engagement of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model as predictors of post-training defending behavior. The five steps were entered simultaneously in the regression analysis. We calculated bivariate correlations among the criterion and predictor variables prior to conducting the main regression analyses. We examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) for predictors to assess multicollinearity. We calculated effect size for the ANCOVA models using partial eta squared (ηp2) with .01 considered small, .06 considered medium, and .14 considered large (Cohen, 1969) and for the regression model using R2 with .01 considered small, .09 considered medium, and .25 considered large (Cohen, 1969). A p-value of < .05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations for the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model and defending behavior are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Skew and kurtosis were satisfactory and did not substantially deviate from the normal distribution for all variables. Bivariate correlations for the criterion and predictor variables are presented in Table 3. Although several of the correlations between the predictor variables were significant at p < .01, the VIF ranged between 1.08–2.69, with corresponding tolerance levels ranging from .37–.93. The VIF is well below the rule of thumb of VIF < 10 (Erford, 2015), suggesting acceptable levels of multicollinearity among the predictor variables.

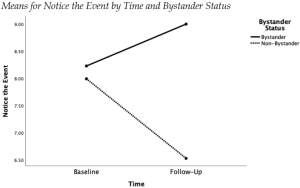

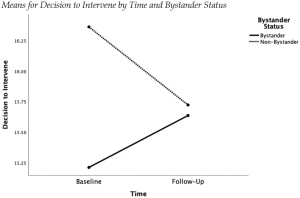

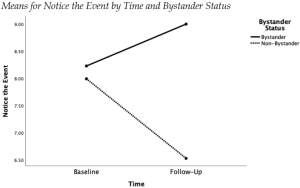

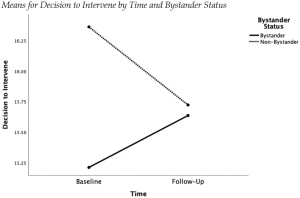

Changes in the Bystander Intervention Model

Results of the RM-MANCOVA indicated a significant main effect for Time, Wilks’ lambda = .86, F(5, 70) = 2.32, p =.05, ηp2 = .14., and a significant interaction effect for Time x Bystander Status, Wilks’ lambda = .77, F(5, 70) = 4.15, p =.002, ηp2 = .23. As seen in Table 1, post-hoc RM-ANCOVAs indicated a significant main effect for Time x Know How to Act (p < .02) and Decision to Intervene (p < .01), as well as significant interaction effects for Time x Bystander Status for Notice the Event (p < .001) and Decision to Intervene (p < .05). Results indicate that Know How to Act increased from baseline (T1) to the follow-up assessment (T2) for both bystanders and non-bystanders. Examination of the significant Time x Bystander Status interaction effects revealed that bystanders reported an increase in Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene, whereas non-bystanders reported a decrease in engagement in these steps of the Bystander Intervention Model (see Figures 1 and 2).

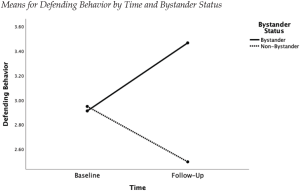

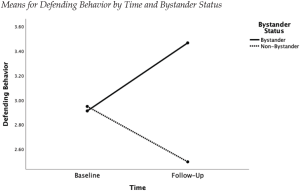

Changes in Defending Behavior

As seen in Table 2, results of the RM-ANCOVA indicated a significant interaction effect for Time x Bystander Status for defending behavior (p < .04). As seen in Figure 3, bystanders reported an increase in defending behavior from T1 to T2, whereas non-bystanders reported a decrease in defending behavior from T1 to T2.

The Relationship Between the Bystander Intervention Model and Defending Behavior

As seen in Table 3, bivariate correlations revealed a positive association between post-training defending behavior and Notice the Event (p < .01), Accept Responsibility (p < .05), Know How to Act (p < .05), and Decision to Intervene (p < .01). We next conducted a linear multiple regression analysis to examine the unique effect of each of the five steps on post-training defending behavior. The full regression equation was significant, R2 = .18, F(53, 7) = 4.39, p = .002. As seen in Table 4, Notice the Event (p < .01) and Decision to Intervene (p < .05) were significant predictors of post-training defending behavior.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Results of the RM-MANCOVAs for Engagement in the Five Steps of the Bystander Intervention Model by Time and Bystander Status

|

Bystander

(n = 24) |

Non-Bystander

(n = 55) |

Total

(n = 79) |

Time |

Time x Bystander Status |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

F(5, 70) |

p |

ηp2 |

F(5, 70) |

p |

ηp2 |

| Notice the Event |

|

|

1.12 |

.29 |

.02 |

14.10*** |

.001 |

.16 |

| Baseline |

8.75 (2.21) |

7.76 (2.35) |

8.06 (2.34) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

9.50 (2.23) |

6.31 (2.36) |

7.28 (2.74) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Interpret as Emergency |

|

|

1.68 |

.20 |

.02 |

0.08 |

.78 |

.001 |

| Baseline |

8.98 (1.05) |

8.58 (1.47) |

8.70 (1.36) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

8.54 (1.56) |

8.36 (1.46) |

8.42 (1.48) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Accept Responsibility |

|

|

0.81 |

.37 |

.01 |

2.62 |

.11 |

.03 |

| Baseline |

11.12 (2.26) |

11.63 (2.17) |

11.49 (2.19) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

11.38 (1.91) |

11.09 (2.25) |

11.18 (2.14) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Know How to Act |

|

|

5.31* |

.02 |

.07 |

1.75 |

.19 |

.02 |

| Baseline |

10.63 (1.81) |

10.95 (2.26) |

10.85 (2.12) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

11.63 (2.34) |

11.54 (1.78) |

11.56 (1.95) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Decision to Intervene |

|

|

6.73** |

.01 |

.08 |

4.12* |

.05 |

.05 |

| Baseline |

15.46 (2.47) |

16.25 (2.24) |

16.01 (2.32) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

15.71 (2.35) |

15.69 (2.43) |

15.70 (2.39) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| *p < .05, **p < .01,***p < .001. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics and Results of the RM-ANCOVA for Defending Behavior by Time and Bystander Status

|

Bystander

(n = 24) |

Non-Bystander

(n = 55) |

Total

(n = 79) |

Time |

Time x Bystander Status |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

F(1, 74) |

p |

ηp2 |

F(1, 74) |

p |

ηp2 |

| Defending Behavior |

|

|

1.36 |

.25 |

.02 |

4.61* |

.04 |

.06 |

| Baseline |

3.17 (1.46) |

2.84 (1.81) |

2.94 (1.71) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Follow-Up |

3.67 (1.66) |

2.41 (1.89) |

2.79 (1.90) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

*p < .05.

Table 3

Bivariate Correlations for Defending Behavior and the Five Steps of the Bystander Intervention Model

| Measure |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

| 1. Defending Behavior |

__ |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Notice the Event |

.31** |

__ |

|

|

|

|

| 3. Interpret as an Emergency |

.04 |

.09 |

__ |

|

|

|

| 4. Accept Responsibility |

.23* |

.11 |

.30** |

__ |

|

|

| 5. Know How to Act |

.26* |

−.07 |

.01 |

.67** |

__ |

|

| 6. Decision to Intervene |

.38** |

.11 |

.29** |

.56** |

.63** |

__ |

*p < .05, **p < .01.

Table 4

Summary of Linear Multiple Regression Analyses for the Five Steps of the Bystander Intervention Model

| Variable |

B |

SE B |

β |

t(73) |

95% CI |

| Notice the Event |

.20 |

.07 |

.29** |

2.70 |

[.05, .35] |

| Interpret as an Emergency |

−.10 |

.15 |

−.08 |

−0.68 |

[−.40, .20] |

| Accept Responsibility |

−.02 |

.14 |

−.02 |

−0.12 |

[−.29, .25] |

| Know How to Act |

.08 |

.16 |

.08 |

0.49 |

[−.25, .41] |

| Decision to Intervene |

.27 |

.12 |

.33* |

2.30 |

[.04, .50] |

Note. SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

Figure 1

Means for Notice the Event by Time and Bystander Status

Note. Simple slopes are shown depicting the direction and degree of the significant interaction testing moderator effects (p = .001). Bystanders reported an increase in Notice the Event and non-bystanders reported a decrease in Notice the Event.

Figure 2

Means for Decision to Intervene by Time and Bystander Status

Note. Simple slopes are shown depicting the direction and degree of the significant interaction testing moderator effects (p = .05). Bystanders reported an increase in Decision to Intervene and non-bystanders reported a decrease in Decision to Intervene.

Figure 3

Means for Defending Behavior by Time and Bystander Status

Note. Simple slopes are shown depicting the direction and degree of the significant interaction testing moderator effects (p = .05). Bystanders reported an increase in defending behavior and non-bystanders reported a decrease in defending behavior.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to extend the literature on bystander interventions by examining the STAC intervention in the context of the Bystander Intervention Model. This is the first study to identify positive changes in engagement in steps of the Bystander Intervention Model following implementation of a bystander bullying intervention (i.e., STAC) and to illustrate how engagement in the steps of the model relates to post-training defending behavior. Overall, results indicate students trained in STAC reported changes in engagement in three of the five steps of the model and an increase in defending behavior from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up assessment (T2). Further, two of the five steps of the model were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior.

Findings indicate that there were significant changes in the Bystander Intervention Model steps of Notice the Event, Know How to Act, and Decision to Intervene from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2). For Know How to Act, there was a significant increase for both bystanders and non-bystanders from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up assessment (T2). These findings parallel prior research on the STAC intervention that indicates students trained in the program report an increase in knowledge and confidence to intervene in bullying situations (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett, Moody, et al., 2017; Moran et al., 2019). For Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene, we found differences between bystanders and non-bystanders over time, such that there was an increase in engagement in these steps among students who reported witnessing bullying but a decrease among students who did not report witnessing bullying after training. Findings among bystanders are consistent with previous research demonstrating that students trained in the STAC intervention report an increase in ability to identify bullying (Midgett, Doumas, et al., 2017), awareness of bullying situations (Johnston et al., 2018), and confidence to intervene (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2020; Midgett, Doumas, et al., 2017; Moran et al., 2019). In contrast, non-bystanders may have reported a decrease in these steps because they did not witness bullying after training.

We did not find significant differences from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2) for either group in engagement in the steps Interpret the Event as an Emergency and Accept Responsibility. For Interpret the Event as an Emergency, a possible explanation for this finding is that students reported high scores on this step at baseline. After removing one item on the scale to achieve adequate internal reliability, the maximum score on the scale was 10.00, with a baseline mean of 8.98 for bystanders and 8.58 for non-bystanders. Thus, students in this sample already had a high understanding of the significance of bullying and the importance of helping targets of bullying, which may have been communicated to them prior to our study when the school decided to implement a bullying intervention program. For Accept Responsibility, while the STAC program was designed to provide students with knowledge, skills, and confidence to intervene in bullying situations, the training content is less focused on taking personal responsibility when witnessing bullying. Thus, this may be an important area for future development, emphasizing the importance of each student taking personal responsibility for acting as a “defender” and that by doing that, each student has an important role in reducing bullying and shifting school climate in a positive direction.

Findings also reveal differences in defending behavior from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2) based on bystander status. Specifically, students who witnessed bullying post-training reported an increase in defending behavior, whereas students who did not witness bullying behavior post-training reported a decrease in defending behavior. Findings among the student bystanders are consistent with research demonstrating that more than 90% of middle school students who witness bullying post-training use the STAC strategies to intervene in bullying situations (Midgett & Doumas, 2020;

Moran et al., 2019). The decrease in defending behavior among students who did not witness bullying post-training can likely be explained by the lack of opportunity to utilize defending behavior.

Finally, we examined engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model as predictors of post-training defending behavior. Although prior research indicates that engagement in each of the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model correlate positively with defending behavior among middle school students (Jenkins & Nickerson, 2016), this is the first study to examine the unique effect of engagement in each of the five steps on post–bystander training defending behavior. Results of the regression analysis indicated that Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were significant predictors of defending behavior. These findings are particularly promising, as engagement in the steps Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene both increased from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2) for students who witnessed bullying after training. Thus, among students who witness bullying as bystanders, the STAC intervention was effective in increasing engagement in the two steps of the bystander model that are uniquely associated with defending behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study extends research on the Bystander Intervention Model, as it is the first study to examine engagement in the steps of the model in the context of a bystander intervention, there are some limitations. First, the sampling frame included a single recruitment location at a private school in the Northwest, and our final sample was relatively small and composed of English-speaking students who were primarily White. Thus, we cannot generalize our findings to students enrolled in ethnically diverse, public middle schools. Further, because the current study did not include a control group, we cannot make causal attributions about our findings. Future studies with larger, more diverse samples using a randomized controlled design should be conducted to increase generalizability and address causality. Additionally, only one third of students in the current sample reported witnessing bullying post-training. Although prior research indicates 80% of students reported witnessing bullying in the past year, our measure of bystander status was limited to witnessing bullying in the past month, as we aimed to capture witnessing bullying post-training. Future research with a longer follow-up would be useful, as the sample of bystanders would likely be larger with more time between the STAC training and follow-up assessment. Additionally, the item we used to assess bystander status was developed by one of our authors and, although it has face validity, the construct validity of the item has not yet been established. Next, Cronbach’s alphas for the Bystander Intervention Model in Bullying Questionnaire scales were lower than found in initial validation research. Additionally, although all Cronbach’s alphas were ultimately in the acceptable range, we needed to eliminate an item from the Interpret the Event as an Emergency scale to achieve adequate internal consistency. Finally, our findings were based on self-report data, potentially leading to biased reporting. Thus, including objective measures of observable “defending” behavior would strengthen the findings.

Implications

The current study provides important implications for counselors related to supporting the role of bystanders in bullying prevention. First, findings add to the growing body of literature supporting the STAC intervention as an effective school-based bullying prevention program. Because 28% of middle school students report being bullied (CDC, 2020), and bullying victimization (Moore et al., 2017) and witnessing bullying (Doumas & Midgett, 2021; Midgett & Doumas, 2019) are associated with significant mental health risks, it is imperative that students are equipped with skills they can use to act as “defenders.” Middle school counselors can implement STAC as a brief, school-wide intervention through core curriculum classroom lessons as part of a school counseling curriculum.

Second, by focusing on specific steps within the Bystander Intervention Model, counselors can break down the complex process of bullying bystander behavior and have a better understanding of what enables students to intervene when they witness bullying. Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were both unique predictors of defending behavior among bystanders post-training. Thus, when delivering the STAC intervention, school counselors can increase awareness of bullying by providing education related to the definition of bullying, including what bullying is and is not, as well as the different types of bullying. School counselors can also encourage students to decide to intervene when they witness bullying by providing the skills and confidence needed to intervene using one of the four STAC strategies. Booster sessions may be particularly helpful in promoting the decision to intervene, as school counselors can use this time to reinforce student strategy use.

Next, we did not find changes in engagement in the steps Interpret the Event as an Emergency or Accept Responsibility. The STAC intervention provides education on the negative consequences associated with bullying; this information could be highlighted by counselors within the STAC training to emphasize the magnitude of the problem of bullying and underscore the importance of identifying bullying as an emergency that needs to be addressed. Additionally, when discussing bystander roles, counselors can tie in the concept of why school personnel need students to help address bullying, focusing on the importance of each student taking personal responsibility for making a difference at school by acting as a defender. When conducting the STAC training, it may also be important to engage students who have not witnessed bullying. Although most students witness bullying at some point during adolescence, not all students have witnessed bullying, or witnessed bullying recently. Thus, it may be important to address this in the training, suggesting that even if a student has not witnessed bullying, it is important to learn about bullying and being a “defender,” as they may witness bullying in the future.

This study also provides implications for counselors working with youth outside of the school setting. Counselors can conceptualize bystander behavior using the Bystander Intervention Model, assessing engagement in each step of the model and providing education to enhance engagement in each step as needed. Counselors can teach youth about bullying behavior and the different types of bullying, provide information about the consequences of bullying to educate youth on the importance of interpreting bullying as a serious problem, and discuss the importance of taking personal responsibility when witnessing bullying. Consistent with Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977), counselors can use the STAC framework to equip youth with skills they can use to intervene when they witness bullying, which can provide opportunities for them to develop and strengthen their self-efficacy through social modeling and mastery experiences to overcome potential challenges. Because self-efficacy influences the decision-making process, the ability to act in the face of difficulty, and the amount of emotional distress experienced while completing a difficult task (Bandura, 2012), self-efficacy can be an important factor in mobilizing youth to engage in the steps of the Bystander Intervention Model. By working with youth on these steps, counselors can empower youth to intervene when they witness bullying and provide youth with prosocial skills they can use to intervene effectively.

Further, this study provides implications for counselor educators. Efforts to reduce bullying and the associated long-standing negative effects on students are widespread in the field, whether working inside schools or in clinical settings. Conversations related to bystander bullying intervention, however, do not seem to have entered counselor education classrooms on a wide scale. Counselor educators can share findings from this study in their courses to educate counseling students on how to provide youth who witness bullying with useful strategies that empower them to confront future instances of school bullying and cyberbullying. The Bystander Intervention Model and the STAC intervention can be infused into the counselor education curriculum to prepare counselors-in-training to work with youth as allies in the prevention of school bullying.

Conclusion

This was the first study to examine if a bullying bystander intervention increases student engagement in the five steps of the Bystander Intervention Model and if engagement in the five steps of the model is related to post-training defending behavior. Results indicate that from baseline (T1) to the 6-week follow-up (T2), both bystanders and non-bystanders trained in the STAC intervention reported changes in Know How to Act, whereas only bystanders reported increases in Notice the Event, Decision to Intervene, and defending behavior. Further, Notice the Event and Decision to Intervene were uniquely associated with post-training defending behavior. Results underscore the importance of guiding students through the bystander process in bullying prevention and provide additional support for the effectiveness of the STAC intervention.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 38(1), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606

Bauman, S., Yoon, J., Iurino, C., & Hackett, L. (2020). Experiences of adolescent witnesses to peer victimization: The bystander effect. Journal of School Psychology, 80, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.03.002

Camodeca, M., & Goossens, F. A. (2005). Children’s opinions on effective strategies to cope with bullying: The importance of bullying role and perspective. Educational Research, 47(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188042000337587

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). #StopBullying. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/stop-bullying/index.html

Cohen, J. (1969). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Academic Press.

Doumas, D. M., & Midgett, A. (2021). The association between witnessing cyberbullying and depressive symptoms and social anxiety among elementary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 58(3), 622–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22467

Erford, B. T. (2015). Research and evaluation in counseling (2nd ed). Cengage.

Goossens, F. A., Olthof, T., & Dekker, P. H. (2006). New participant role scales: Comparison between various criteria for assigning roles and indications for their validity. Aggressive Behavior, 32(4), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20133

Jenkins, L. N., & Nickerson, A. B. (2016). Bullying participant roles and gender as predictors of bystander intervention. Aggressive Behavior, 43(3), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21688

Johnston, A. D., Midgett, A., Doumas, D. M., & Moody, S. (2018). A mixed methods evaluation of the “aged-up” STAC bullying bystander intervention for high school students. The Professional Counselor, 8(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.15241/adj.8.1.73

Latané, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? Prentice Hall.

Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2019). Witnessing bullying at school: The association between being a bystander and anxiety and depressive symptoms. School Mental Health, 11, 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09312-6

Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2020). Acceptability and short-term outcomes of a brief, bystander intervention program to decrease bullying in an ethnically blended school in low-income community. Contemporary School Psychology, 24, 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00321-w

Midgett, A., Doumas, D. M., Peralta, C., Bond, L., & Flay, B. (2020). Impact of a brief, bystander bullying prevention program on depressive symptoms and passive suicidal ideation: A program evaluation model for school personnel. Journal of Prevention and Health Promotion, 1(1), 80–103.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2632077020942959

Midgett, A., Doumas, D., Sears, D., Lundquist, A., & Hausheer, R. (2015). A bystander bullying psychoeducation program with middle school students: A preliminary report. The Professional Counselor, 5(4), 486–500. https://doi.org/10.15241/am.5.4.486

Midgett, A., Doumas, D., Trull, R., & Johnston, A. D. (2017). A randomized controlled study evaluating a brief, bystander bullying intervention with junior high school students. Journal of School Counseling, 15(9). http://www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v15n9.pdf

Midgett, A., Moody, S. J., Rilley, B., & Lyter, S. (2017). The phenomenological experience of student-advocates trained as defenders to stop school bullying. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12044

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

Moran, M., Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2019). Evaluation of a brief, bystander bullying intervention (STAC) for ethnically blended middle schools in low-income communities. Professional School Counseling, 23(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20940641

Nickerson, A. B., Aloe, A. M., Livingston, J. A., & Feeley, T. H. (2014). Measurement of the bystander intervention model for bullying and sexual harassment. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.003

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Porter, J. R., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2016). Children’s tendency to defend victims of school bullying. Professional School Counseling, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-20.1.1

Salmivalli, C., Kaukiainen, A., & Voeten, M. (2005). Anti-bullying intervention: Implementation and outcome. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(3), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X26011

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-T

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488

Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(5), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.597090

Summers, K. H., & Demaray, M. K. (2008). Bullying participant behaviors questionnaire. Northern Illinois University.

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003

Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Sacco, F. C. (2004). The role of the bystander in the social architecture of bullying and violence in schools and communities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036(1), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1330.014

U.S. Department of Education: National Center for Educational Statistics. (2019). Student reports of bullying: Results from the 2017 School Crime Supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCES 2017-015). https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019054.pdf

van der Ploeg, R., Kretschmer, T., Salmivalli, C., & Veenstra, R. (2017). Defending victims: What does it take to intervene in bullying and how is it rewarded by peers? Journal of School Psychology, 65(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.06.002

Wu, W.-C., Luu, S., & Luh, D.-L. (2016). Defending behaviors, bullying roles, and their associations with mental health in junior high school students: A population-based study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1066. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3721-6

Matthew Peck, PhD, LPC, is an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas. Diana M. Doumas, PhD, LPC, is Distinguished Professor of Counselor Education at Boise State University. Aida Midgett, PhD, LPC, is a professor at Boise State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Matthew Peck, 100 Graduate Education Building, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, mattpeck@uark.edu.

Mar 30, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 1

April D. Johnston, Aida Midgett, Diana M. Doumas, Steve Moody

This mixed methods study assessed the appropriateness of an “aged-up,” brief bullying bystander intervention (STAC) and explored the lived experiences of high school students trained in the program. Quantitative results included an increase in knowledge and confidence to intervene in bullying situations, awareness of bullying, and use of the STAC strategies. Utilizing the consensual qualitative research methodology, we found students spoke about (a) increased awareness of bullying situations, leading to a heightened sense of responsibility to act; (b) a sense of empowerment to take action, resulting in positive feelings; (c) fears related to intervening in bullying situations; and (d) the natural fit of the intervention strategies. Implications for counselors include the role of the school counselor in program implementation and training school staff to support student “defenders,” as well as how counselors in other settings can work with clients to learn the STAC strategies through psychoeducation and skills practice.

Keywords: bullying, bystander intervention, consensual qualitative research (CQR), high school, mixed methods

Researchers have defined bullying as “when one or more students tease, threaten, spread rumors about, hit, shove, or hurt another student over and over again” (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDCP], 2017, p. 7). Bullying includes verbal, physical, or relational aggression, as it often occurs through the use of technology (e.g., cyberbullying). National statistics indicate approximately 20.5% of high school students are victims of bullying at school and 15.8% are victims of cyberbullying (CDCP, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2016). Although school bullying peaks in middle school, it remains a significant problem at the high school level, with the highest rates of cyberbullying reported by high school seniors (18.7%; U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2016).

There are wide-ranging negative consequences experienced by students who are exposed to bullying as either a target or bystander (Bauman, Toomey, & Walker, 2013; Doumas, Midgett, & Johnston, 2017; Hertz, Everett Jones, Barrios, David-Ferdon, & Holt, 2015; Rivers & Noret, 2013; Rivers, Poteat, Noret, & Ashurst, 2009; Smalley, Warren, & Barefoot, 2017). High school students who are targets of bullying report higher levels of risky health behaviors, including physical inactivity, less sleep, risky sexual practices (Hertz et al., 2015), elevated substance use (Doumas et al., 2017; Smalley et al., 2017), and higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation (Bauman et al., 2013; Smalley et al., 2017). Adolescents who observe bullying as bystanders also report associated negative consequences, and, in some instances, report more problems than students who are directly involved in bullying situations (Rivers & Noret, 2013; Rivers et al., 2009). Specifically, bystanders have been found to be at higher risk for substance abuse and overall mental health concerns than students who are targets (Rivers et al., 2009). Bystanders also are significantly more likely to report symptoms of helplessness and potential suicidal ideation compared to students not involved in bullying (Rivers & Noret, 2013). Furthermore, although bystanders are often successful when they intervene on behalf of targets of bullying (Gage, Prykanowski, & Larson, 2014), bystanders usually do not intervene because they do not know what to do (Forsberg, Thornberg, & Samuelsson, 2014; Hutchinson, 2012). Failure to respond to observed bullying leads to feelings of guilt (Hutchinson, 2012) and coping through moral disengagement (Forsberg et al., 2014). Thus, there is a need to train bystanders to intervene to both reduce bullying and buffer bystanders from the negative consequences associated with observing bullying without acting.

To address the negative effects that can result from being exposed to bullying, researchers have developed numerous bullying prevention and intervention programs for implementation within the school setting. Many of these programs are comprehensive, school-wide interventions (Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, 2012; Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel, & Loeber, 2011). However, findings indicate these programs are most effective for students in middle and elementary school (Yeager, Fong, Lee, & Espelage, 2015). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis indicates that bystander intervention is an important component of bullying intervention; however, few comprehensive programs include a bystander component (Polanin et al., 2012). Further, those programs that do include a bystander component have been normed on children within the context of the classroom setting (Salmivalli, 2010). High school students experience greater independence at school, with less adult supervision in the hallways and at lunch, and move to different classroom locations throughout the day. Thus, there is a need for effective bullying bystander programs and interventions that have been “aged up” specifically for the high school level (Denny et al., 2015).

The STAC Program

The STAC program is a brief bystander intervention that teaches students who witness bullying to intervene as “defenders” (Midgett, Doumas, Sears, Lundquist, & Hausheer, 2015). The STAC acronym stands for the four bullying intervention strategies taught in the program: “Stealing the Show,” “Turning It Over,” “Accompanying Others,” and “Coaching Compassion.” The second author created the STAC program for the middle and elementary school level with the intention of establishing school counselors as leaders in program implementation. The program includes a 90-minute training with bi-weekly, 15-minute small group follow-up meetings, placing low demands on schools for implementation. Findings from studies conducted at the elementary and middle school level indicate students trained in the STAC program report an increase in knowledge and confidence to intervene as defenders (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2016; Midgett, Doumas, & Trull, 2017), as well as increased use of the STAC strategies (Midgett, Doumas, Trull, & Johnston, 2017). Additionally, research demonstrates students trained in the STAC program report reductions in bullying (Midgett, Doumas, Trull, & Johnson, 2017), as well as increases in self-esteem (Midgett, Doumas, & Trull, 2017) and decreases in anxiety (Midgett, Doumas, Trull, & Johnston, 2017), compared to students in a control group.

Development of the STAC Program for High School

The authors conducted a previous qualitative study to inform the modification of the original STAC program to be appropriate for the high school level (for details, see Midgett, Doumas, Johnston, et al., 2017). Based upon data generated from high school students, the authors “aged up” the STAC program by incorporating the following content into the didactic and role-play components of the training: (a) cyberbullying through social media and texting, (b) group dynamics in bullying, and (c) bullying in dating and romantic relationships. The authors also aged up the program by including developmentally appropriate language (e.g., breaks vs. recess) and content, including common locations where bullying occurs (e.g., school parking lot vs. the school bus) and age-appropriate examples of physical bullying (e.g., covert behaviors such as “shoulder checking,” “backpack checking,” and “tripping” vs. physical fights).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to extend the literature by evaluating the appropriateness of the aged-up STAC program for the high school level and to explore the experiences of students trained in the program. Following guidelines suggested by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (2010), the literature review guided the formulation of the study rationale, goal, objectives, and research questions. Despite the need to provide anti-bullying programs to high school students, the majority of bullying intervention research has been conducted with elementary and middle school students (Denny et al., 2015). Although intervening on behalf of students who are targets of bullying is associated with positive outcomes (Hawkins, Pepler, & Craig, 2001), research on bystander intervention programs aged up for high school students is limited. The present authors could find only one program, StandUP, developed specifically for high school students. Results of a pilot study indicated students participating in the 3-session StandUP online program reported an increase in positive bystander behavior and decreases in bullying behavior (Timmons-Mitchell, Levesque, Harris, Flannery, & Falcone, 2016). The research noted several methodological limitations that limit the generalizability and validity of the findings, including a 6.8% response rate, 22% attrition rate with differential attrition by race and bullying status, and the use of a single-group design.

Thus, the goal of this study was to add to the knowledge on bullying interventions for high school students. Our objectives were to (a) examine the influence of the STAC program on knowledge and confidence, awareness of bullying, and use of the STAC strategies, and (b) describe and explore the experience of high school students participating in the STAC intervention. We were interested in answering the following mixed method research questions: (a) Do students trained in the aged-up STAC intervention report an increase in knowledge and confidence to intervene as defenders? (b) Do students trained in the aged-up STAC intervention have an increased awareness of bullying? (c) Do students trained in the aged-up STAC intervention use the STAC strategies to intervene when they observe bullying? and (d) What were high school students’ experiences of participating in the aged-up STAC intervention and using the STAC strategies to intervene in bullying situations?

Methods

Mixed Research Design

A mixed methods design was implemented with a single group of participants who completed the STAC training. We were interested in the influence of the STAC intervention on students’ knowledge and confidence, awareness of bullying, and use of the STAC strategies. An additional interest was to understand students’ experiences of the STAC training. The purpose of selecting a mixed methods design was to maximize interpretation of findings, as mixed methods designs often result in a greater understanding of complex phenomena than either quantitative or qualitative studies can produce alone (Creswell, 2013). Hesse-Biber (2010) also advocates for the convergence of qualitative and quantitative data to enhance and triangulate findings. Following the guidelines described by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (2010), we chose to supplement the quantitative data with qualitative data to investigate the in-depth, lived experiences of high school students trained as defenders in the aged-up STAC program. Our research design was a partially mixed, sequential design (Creswell, 2009; Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2010). The quantitative design was a single-group repeated-measures design and the qualitative component included consensual qualitative research (CQR; Hill et al., 2005).

Participants

Our sampling design was sequential-identical (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2010), with the same participants completing surveys followed by focus groups. The sample consisted of 22 students

(n = 15 females [68.2%]; n = 7 males [31.8%]) recruited from a public high school via stratified random sampling in the Northwestern region of the United States. Participants ranged in age from 15–18 years old (M = 16.82 and SD = 0.91), with reported racial backgrounds of 59.1% White, 18.2% Asian, 13.6% Hispanic, and 9.1% African American. Of the 22 participants trained in the STAC program, 100% participated in follow-up focus groups and follow-up data collection.

Procedures

The current study was completed as part of a larger study designed to develop and test the effectiveness of the aged-up STAC intervention. Following institutional research board approval, the researchers randomly selected 200 students using stratified proportionate sampling and then obtained parental consent and student assent from 57 students, for a response rate of 28.5%. The current sample consists of the 22 students who participated in the STAC intervention. The recruiting team included school counselors, a doctoral student, and master’s students. A team member met briefly with students selected to discuss the project and provided an informed consent form to be signed by a parent or guardian. A team member met with students with parental consent to explain the research in greater detail and to obtain student assent. Researchers trained participants in the 90-minute aged-up STAC program and then conducted two 15-minute bi-weekly follow-up meetings for 30 days following the training. Students completed baseline, post-training, and 30-day follow-up surveys. Six weeks after the STAC training, team members conducted three 45-minute open-ended, semi-structured focus groups to investigate students’ experiences being trained as defenders in the aged-up STAC program. Researchers audio recorded the focus groups for transcription purposes. The team provided pizza to students after the follow-up survey and at the end of each focus group. The university and school district review boards approved all research procedures.

Measures

Knowledge and Confidence to Intervene. The Student-Advocates Pre- and Post-Scale (SAPPS; Midgett et al., 2015) was used to measure knowledge of bullying, knowledge of the STAC strategies, and confidence to intervene. The questionnaire is comprised of 11 items that measure student knowledge of bullying behaviors, knowledge of the STAC strategies, and confidence intervening in bullying situations. Examples of items include: “I know what verbal bullying looks like,” “I know how to use humor to get attention away from the student being bullied,” and “I feel confident in my ability to do something helpful to decrease bullying at my school.” Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (I totally disagree) to 4 (I totally agree). Items are summed to create a total scale score. The SAPPS has established content validity and adequate internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .75–.81 (Midgett et al., 2015; Midgett & Doumas, 2016; Midgett, Doumas, & Trull, 2017; Midgett, Doumas, Trull, & Johnston, 2017). Cronbach’s alpha was .83 for this sample.

Awareness of Bullying. Awareness of bullying was assessed using one item. Students were asked to respond Yes or No to the following question: “Have you seen bullying at school in the past month?” Prior research has used this question to test the impact of the STAC program on observing and identifying bullying behavior post-training (Midgett, Doumas, Trull, & Johnston, 2017).

Use of STAC Strategies. The use of each STAC strategy was measured by a single item. Students were asked, “How often would you say that you used these strategies to stop bullying in the past month? (a) Stealing the Show—using humor to get the attention away from the bullying situation,

(b) Turning It Over—telling an adult about what you saw, (c) Accompanying Others—reaching out to the student who was the target of bullying, and (d) Coaching Compassion—helping the student who bullied develop empathy for the target.” Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never/Almost Never) to 5 (Always/Almost Always). Prior research has used these items to examine use of STAC strategies post-training (Midgett, Doumas, Trull, & Johnston, 2017).

High School Students’ Experiences. Researchers followed Hill et al.’s (2005) recommendation to develop a semi-structured interview protocol to answer the question, “What were high school students’ experiences of participating in the aged-up STAC intervention and using the STAC strategies to intervene in bullying situations?” Researchers developed questions based on previous qualitative findings with middle school students (Midgett, Moody, Reilly, & Lyter, 2017), quantitative results indicating students trained in the program use the STAC strategies (Midgett, Moody, et al., 2017), and a review of the literature (Jacob & Furgerson, 2012). Researchers asked students the following questions: (1) Can you please talk about the personal values you had before the STAC training that were in line with what you learned during the STAC training? (2) Please share your experience using the STAC strategies (Stealing the Show, Turning It Over, Accompanying Others, and Coaching Compassion), (3) Can you share how using the STAC strategies made you feel about yourself? (4) How did being trained in the STAC program impact your relationships? (5) Can you please talk about your fears related to using the strategies in different bullying situations? and, (6) Overall, what was it like to be trained in the STAC program and use the STAC strategies?

The STAC Intervention

The STAC intervention began with a 90-minute training, which included information about bullying and strategies for intervening in bullying situations (Midgett et al., 2015). Following the training, facilitators met with students twice for 15 minutes throughout the subsequent 30 days to support them as they applied what they learned in the training. During these meetings, researchers reviewed the STAC strategies with students, and asked students about bullying situations they witnessed and whether they utilized a strategy. If students indicated they observed bullying but did not utilize a strategy, researchers helped students brainstorm ways in which they could utilize one of the four STAC strategies in the future.

Didactic Component. The didactic component included icebreaker exercises, an audiovisual presentation, two videos about bullying, and hands-on activities to engage students in the learning process. Students learned about (a) the complex nature of bullying in high school often involving group dynamics rather than single individuals; (b) different types of bullying, with a focus on cyberbullying and covert physical bullying; (c) characteristics of students who bully, including the likelihood they have been bullied themselves, to foster empathy and separate the behavior from the student; (d) negative associated consequences of bullying for students who are targets, perpetrate bullying, and are bystanders; (e) bystander roles and the importance of acting as a defender; and (f) the STAC strategies used for intervening in bullying situations. The four strategies are described below.

Stealing the Show. Stealing the Show involves using humor or distraction to turn students’ attention away from the bullying situation. Trainers teach bystanders to interrupt a bullying situation to displace the peer audience’s attention away from the target (e.g., tell a joke, initiate a conversation with the student who is being bullied, or invite peers to play a group game such as basketball).

Turning It Over. Turning It Over involves informing an adult about the situation and asking for help. During the training, students identify safe adults at school who can help. Students are taught to always “turn it over” if there is physical bullying taking place or if they are unsure as to how to intervene. Trainers also emphasized the importance of documenting evidence in cyberbullying cases by taking a screenshot or picture of the computer or cell phone over time for authorities (i.e., school principal and resource officer) to take action.

Accompanying Others. Accompanying Others involves the bystander reaching out to the student who was targeted to communicate that what happened is not acceptable, that the student who was targeted is not alone, and that the student bystander cares about them. Trainers provide examples of how students can use this strategy either directly, by inviting a student who was targeted to talk about the situation, or indirectly, by approaching a peer after they were targeted and inviting them to go to lunch or spend time with the bystander. This strategy focuses on communicating empathy and support to the student who was targeted.

Coaching Compassion. Coaching Compassion involves gently confronting the student who bullied either during or after the bullying incident to communicate that his or her behavior is unacceptable. Additionally, the student bystander encourages the student who bullied to consider what it would feel like to be the target in the situation, thereby fostering empathy toward the target. Bystanders are encouraged to implement Coaching Compassion when they have a relationship with the student who bullied or if the student who bullied is in a lower grade and the bystander believes they will respect them.

Role-Plays. Trainers divided students into small groups to practice the STAC strategies through role-plays that included hypothetical bullying situations. The team developed the scenarios based on student feedback on types of bullying that occur in high school, including cyberbullying, romantic relationship issues, and covert physical bullying (Midgett, Doumas, Johnston, Trull, & Miller, 2017). See Appendix A for the STAC scenarios.

Post-Training Groups. STAC training participants met in 15-minute groups with two graduate student trainers twice in the 30 days post-training. In these meetings, students reviewed the STAC strategies, shared which strategies they used, and explained whether they felt the strategies were effective in intervening in bullying. Trainers also addressed questions and supported students in brainstorming other ways to implement the strategies, including combining strategies or working as a group to intervene together.

Data Analysis

Quantitative. The authors used quantitative analyses to test for significant changes in knowledge and confidence and to provide descriptive statistics for frequency of awareness of bullying and the use of the STAC strategies. An a priori power analysis was conducted using the G*Power 3.1.3 program (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) for a repeated-measures, within-subjects ANOVA with three time points. Results of the power analysis indicated a sample size of 20 was needed for power of > 0.80 to detect a medium effect size for the main effect of time with an alpha level of .05. Thus, the final sample size of 22 met the needed size to provide adequate power for analyses.

Before conducting primary analyses, all variables were examined for outliers and normality. The authors found no outliers and all variables were within the normal range for skew and kurtosis. To assess changes in knowledge and confidence, we conducted a GLM repeated-measures ANOVA with one independent variable, time (baseline, post-intervention, follow-up), and post-hoc follow-up paired t-tests to examine differences between time points. To evaluate awareness of bullying, we computed descriptive statistics to determine how many participants observed bullying at baseline and follow-up. To evaluate the use of STAC strategies, we computed descriptive statistics to examine the frequency of use of each strategy at the follow-up assessment. The authors used an alpha level of p < .05 to determine statistical significance and used partial eta squared (h2p) as the measure of effect size for the repeated-measures ANOVA and Cohen’s d for paired t-test with magnitude of effects interpreted as follows: small (h2p > .01; d = .20), medium (h2p > .06; d = .50), and large (h2p > .14; d = .80; Cohen, 1969; Richardson, 2011). All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24.0.