Mar 9, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 1

Laura Haddock, Kristi Cannon, Earl Grey

Computer-enhanced counselor education dates as far back as 1984, and since that time counselor training programs have expanded to include instructional delivery in traditional, hybrid, and fully online programs. While traditional schools still house a majority of accredited programs, the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) has accredited almost 40 fully online counselor education programs. The purpose of this article is to outline the similarities and differences between CACREP-accredited online or distance education and traditional program delivery and instruction. Topics include andragogy, engagement, curriculum, instruction, assessment, and gatekeeping.

Keywords: online, distance education, counselor education, andragogy, CACREP

Online counselor education training programs have continued to be developed year after year and have grown in both popularity and effectiveness. Recent trends in graduate education reflect online instruction as part of common practice (Kumar et al., 2019). Virtual training opportunities promote access for students who might not otherwise be able to participate in advanced education, and for some students, distance learning can be the ideal method to further their education as they strive to balance enrollment with remote geography, family life, and employment commitments. However, regardless of instructional setting, all counselor training programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) have distinct similarities. For example, CACREP-accredited programs are by nature graduate programs. There are no CACREP-accredited counselor training programs at the bachelor’s level or the doctoral level. To clarify, CACREP does offer accreditation for doctoral programs; however, most are focused on counselor education and supervision, and the curriculum is geared toward instructor and supervisor preparation versus counselor training. Thus, in every academic setting, master’s-level CACREP-accredited professional counselor training programs are simultaneously an introductory and a terminal degree. Both online and traditional programs must be prepared to design and deliver curriculum to students of various educational backgrounds that will ultimately equip graduates with the skills and dispositions needed for professional practice. As graduate students, enrollment is fully comprised of adult learners and this holds true regardless of instructional setting. Interestingly, most professional counseling literature uses the term pedagogy to reference the facilitation of learning within counselor training. For the purposes of this article, we will utilize the term andragogy, which is “the art and science of teaching adults” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

Counselor Education and Andragogy

Professional counseling literature related to andragogy is scarce and largely contains studies focused on meeting the needs of diverse students and preparing counselors to work with culturally diverse clients. Barrio Minton et al. (2014) conducted a 10-year content analysis of studies related to teaching and learning in counselor education, and the large majority of the studies grounded counselor preparation andragogy in counseling literature and theory as opposed to learning theories or research. Efforts to identify research specific to the andragogy of online counselor training produced minimal results, and a clear gap in the literature exists for empirical research when comparing online and traditional learning and instructional delivery. What did emerge from the research was debate regarding whether an online environment is appropriate to teach adult learners curriculum of the interpersonal nature of counseling (Lucas & Murdock, 2014). However, empirical evidence does exist to support the delivery of instruction in online academic environments as effective, although they require different andragogical methods and teaching practices (Cicco, 2013a). Additionally, studies on online education in higher education suggest that differences in student learning outcomes for traditional students and online students are not statistically significant (Buzwell et al., 2016). In fact, some evidence demonstrates superior outcomes in students enrolled in online courses (Allen et al., 2016). However, student perceptions of online learning and learning technologies outweighed pedagogy for impact on the quality of academic achievement (Ellis & Bliuc, 2019). Thus, emerging research on both method and student perceptions supports online counselor education as a viable instructional approach.

Characteristics of Online Learners

Before examining the similarities and differences in instructional practice and curriculum development between online and brick-and-mortar settings, consideration for the composition of the student body is warranted. The student body for both online and traditional programs have a higher enrollment of female versus male students and Caucasian versus other ethnicities across genders (CACREP, 2017). Because online programs are often comprised of non-traditional students who work full-time and are geographically diverse, this invites a student enrollment varied in age, race, ethnicity, physical ability, and educational background (Barril, 2017). Online training programs also demonstrate greater enrollment by learners from underrepresented populations (Buzwell et al., 2016).

Online Education Stakeholders

When we compare traditional programs and their online counterparts, the primary stakeholders for both settings include students and faculty members. In counselor training programs, the clients the graduates will serve also are stakeholders. The processes that occur in both traditional and online classrooms are aligned, with the “foci being teaching, learning, and . . . evaluation” (Cicco, 2013b, p. 1).

In 2018, Snow et al. conducted a study examining the current practices in online counselor education. The results indicated that overall, faculty instructors for online settings indicate a smaller class size with a reported mean enrollment of 15.5 students compared to traditional classroom enrollment of 25 or more. The study showed that both online and traditional programs utilize a variety of strategies for course enrollment, including both student-driven course selection and program-guided course enrollment within the learning community.

Learning Community

As previously mentioned, student perceptions of online learning emerged in the literature as a key for student academic success. However, research suggests that attrition rates for online students are much higher than those in traditional programs (Murdock & Williams, 2011). It has been suggested that elevated attrition rates in online programs could be related to students lacking a sense of connection to peers and program faculty and an insufficient learning community (Lu, 2017). Research reveals that the use of learning communities has proven successful in improving the retention rates (DiRamio & Wolverton, 2006; Kebble, 2017). The type and frequency of student-to-student and student-to-faculty interactions in online versus traditional programs are different. In both settings, scholars seek a valuable learning experience (Onodipe et al., 2016). However, while social interaction is a routine part of face-to-face learning, the online environment requires intentional effort to promote interaction between learners and faculty. Research has suggested that online learners need assignments and activities that emphasize the promotion of connection with both the material and peers and faculty (Lu, 2017). At a basic level, affirmation for a job well done on an assignment and prompt and comprehensive feedback are examples of faculty–student engagement that produce student satisfaction regardless of instructional setting (O’Shea et al., 2015). However, we contend these sorts of intentional, personalized instructional interactions are critical for online students who could otherwise feel alienated or isolated in the online learning environment. For online educators, one requirement is to persistently promote engagement for online learners, which can prove to be challenging, and require supplementary or diverse approaches to forging productive student learning communities. Simply transferring material used in traditional classrooms into an online learning management system is not adequate to promote engagement and could instead contribute to both cognitive and emotional detachment.

Instructional Practice and Curriculum Development

There is limited literature comparing the curriculum development and content delivery methods between traditional and distance education specific to counselor education, but there is a body of literature comparing the factors that influence the efficacy of traditional and distance education in general. The gap in the counselor education literature requires a comparative assessment of the deciding factors leading to different curriculum development and delivery methods for counselor education programs.

Delivery Preferences

Taylor and Baltrinic (2018) conducted a study in which they explored counselor educator course preparation and instructional practices. Unfortunately, the researchers did not include the educational delivery setting as a variable in the descriptive demographics, so it was impossible to discern whether the techniques that were identified as preferred methods of instruction were associated with online or traditional classrooms. However, it can be assumed that the preferences that were identified were geared more specifically to an in-class, face-to-face presentation. The five teaching methods that were explored for preferences in teaching content versus clinical courses included lecture, small group discussions, video presentations, case studies, and in-class modeling. Anecdotally, we assert that the reported preferences for instruction delivery would be different for online instructors and would be impacted by content delivery modality and technology. For example, if plans are disrupted in the traditional face-to-face classroom, such as internet disconnection, an instructor has the freedom to shift focus and move to a backup plan. However, an alternate instructional plan is not always available or feasible in an online environment (Marchand & Gutierrez, 2012). Delivery preferences can be influenced by the educational delivery setting in which the program was developed.

Educational Delivery Settings

Content delivery modalities determine whether a program is defined as traditional or distance (telecommunications or correspondence) in accordance with the Office of Postsecondary Education Accreditation Division of the U.S. Department of Education (2012). If a program offers 49% or less of their instruction via distance learning technologies, with the remaining 51% via in-person synchronous classroom, the Department of Education categorizes that program as traditional education. The Department of Education defines distance education as instructional delivery using technology to support “regular and substantive interaction between the students and the instructor, either synchronously or asynchronously” in courses in which the students are physically separated from their instructor (Office of Postsecondary Education Accreditation Division, 2012, p. 5). The Department of Education further clarifies that a distance education program offers at least 50% or more of their instruction via distance learning technologies that include telecommunications (Office of Postsecondary Education Accreditation Division, 2012). The Office of Federal Student Aid of the U.S. Department of Education separates distance programs between telecommunications courses and correspondence courses. A telecommunication course uses “television, audio, or computer (including the Internet)” to deliver the educational materials (Office of Federal Student Aid, 2017, p. 299). A correspondence course includes home study materials without a course or regular interactions with an instructor (Office of Federal Student Aid, 2017). Although discussing correspondence education is outside the scope of this article, including it as context for educational delivery settings is valuable to have a full view of content delivery options as defined by the Department of Education.

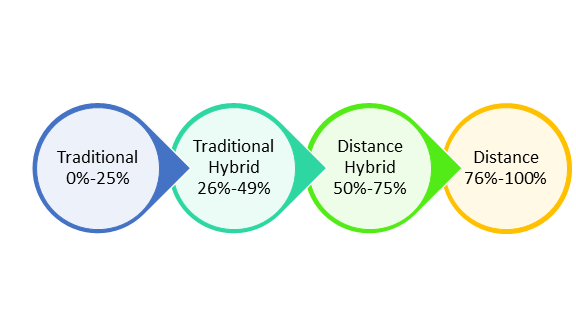

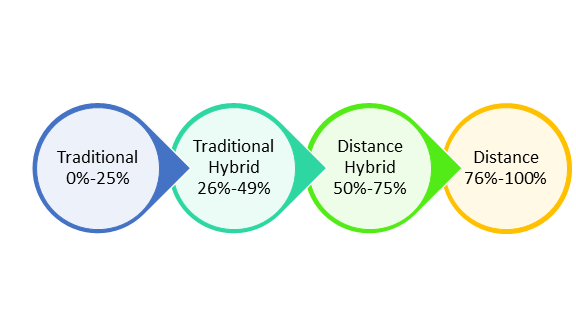

Through informal observations of counselor education programs, the hybrid or blended program seems to be neglected in the current educational delivery setting definitions provided by the Department of Education. Although there are variations in the definition of a hybrid or blended program, the Department of Education does not use hybrid or blended education as a category. Because most, if not all, programs integrate some level of telecommunications technology as defined above, we recommend using the word hybrid as a qualifier to the categories of educational delivery settings to more accurately categorize the unique complexity and needs of every counselor education program. We recommend defining the qualifier of hybrid as a program that offers at least 25% and no more than 75% of their instruction via a combination of distance learning telecommunication technologies and a traditional classroom. This qualifier would be added to the Department of Education’s primary definition of a traditional or distance program based on the percentage of telecommunications technologies used for content delivery. By adding this qualifier, a program may be categorized as traditional, traditional hybrid, distance hybrid, or distance education. The traditional setting uses telecommunications technologies for up to 25% of their content delivery, traditional hybrid is 26%–49%, distance hybrid is 50%–75%, and distance education has 76%–100% of their content delivered using telecommunications technologies. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the Educational Delivery Settings Continuum.

Figure 1

Educational Content Delivery Continuum.

Note. This figure demonstrates the percentages of content delivered using telecommunications technologies for each setting.

When we adopt the continuum above it becomes clear that counselor education content delivery cannot be reduced to a dichotomy. Viewing counselor education program content delivery through the lens of a continuum results in valuing the unique needs, complexities, and strengths of all counselor education programs with varying degrees of technology sophistication. Further, using this continuum can more accurately highlight the similarities across counselor educator programs instead of the differences. By definition, if any program relies on email and a website to communicate information about the content of the program (e.g., submitting assignments), that program is using telecommunication technologies to some degree. The above continuum is an important context for reviewing the current state of counselor education program content delivery and curriculum development. Because the traditional educational delivery setting was the starting point for formal education, a program will inevitably have a reason, purpose, or motive for integrating technology into a traditional model.

Motivation to Integrate Learning Technologies

When we examine the history of curriculum development and delivery methods, we can use traditional education as our starting point, dating back to the Socratic method (Snow & Coker, 2020). As Snow and Coker (2020) have shared, there are two primary motivators to developing or integrating technology into content delivery—increasing access and increasing revenues. These program development motivators can be valuable when initiating curricula, as long as programs consider how technological tools will be used to promote the “regular and substantive interaction between the students and the instructor” (Office of Postsecondary Education Accreditation Division, 2012, p. 5). This requires initial planning to integrate technological tools that can both deliver content and promote a learning community. Technology in any amount is a tool requiring skillful application in order to promote an effective technologically supported learning experience (Hedén & Ahlstrom, 2016; Koehler et al., 2004). Although some might choose to debate the differences in benefit between increasing access and revenues, a more equitable comparison for motivations requires the context of the faculty’s ability to skillfully deliver course content using technology. The faculty’s instructional practices impact the application of the program development motivators.

Instructional Practice

As we consider the continuum of technology integration for counselor education programs in different settings, we must consider the level of synchronicity for content delivery. Historically, the nature of professional counseling work has been synchronous, in-person interactions. The synchronous nature of the counseling profession is often used to argue that traditional programs are more effective than distance programs. Looking at a historical read/write approach (i.e., read materials and rely on written assignments to evaluate learning) to distance education, there can be some validity to the perceived challenges for a distance counselor education program that delivered its content in a read/write format only. Often, distance counselor education programs have overcome this perceived challenge by integrating traditional components into their curriculum.

Technology advancements provide new mediums for both synchronous and asynchronous learning to prepare a counselor-in-training. Counselors’ and counselor educators’ duties require some amount of synchronous activities (i.e., in-person interactions between two or more individuals occurring at the same time). As we view the counseling profession through the lens of telecommunications, the paradigm is expanding to include asynchronous counseling activities (i.e., interactions between two or more individuals occurring at various time intervals, such as text messaging).

Because the counseling profession requires human interactions, it seems fair that synchronous components, whether in person or technologically assisted, are necessary to prepare counselors-in-training. The synchronous component of every counselor education program is that of the practicum and internship experiences. The didactic curriculum in a counselor education program can vary between synchronous and asynchronous. But when a counselor-in-training meets the practicum and internship benchmarks, synchronicity is required by virtue of program accreditation standards and professional regulations. Although there can be an expansion into the asynchronous approach to counseling field experience in the distant future, it may not be realistic to imagine a fully asynchronous field experience. Consideration of the modalities used to deliver supervision and direct counseling services as part of the practicum and internship provides great opportunity to align these experiences with the overall curriculum delivery methods of the counselor education program and promote future skills for professional counselors.

Curriculum Development Models

The curriculum development model used for the counselor education program also can impact the program’s level of synchronicity. Although there are multiple designs that can guide curriculum development, there are two models often used in counselor education—teacher-centered and subject-centered. Programs used the teacher-centered approach when the curriculum was designed with the teacher as the subject matter expert and the content was designed to guide the learner through the content by way of the guidance of the teacher (Dole et al., 2016; Pinnegar & Erickson, 2010). Programs used the subject-centered approach when the subject matter guided the organization of the content and how the learning was assessed to support consistency across instructors (Burton, 2010; Dole et al., 2016). It would be inaccurate to assign either one of the approaches to a specific setting category as each approach can be plotted along the above continuum.

Teacher-Centered Approach

The teacher-centered approach allows the teacher to own their curriculum, and the specifics of the content within the same subject can vary across teachers. The teacher-centered approach occurs when assigned faculty members develop a course from scratch. They can use information from similar courses; however, there is a great amount of flexibility and freedom to develop the course content and delivery modalities. This approach may or may not integrate curriculum across multiple sections of the course taught by different instructors. The teacher-centered approach also can have varying degrees of course curriculum connections across different courses within the program. The instructor of the course in the teacher-centered approach typically develops the course and teaches the course, so they are intimately aware of the intention and nuances behind each element of the course curriculum.

Subject-Centered Approach

The subject-centered approach often relies on a team approach and can support consistency across sections of the same course. The subject-centered approach can assign responsibilities for the development to different team members (e.g., subject matter expert, curriculum design expert, learning resource expert). Team members work collaboratively to develop curriculum that targets critical elements of knowledge, skills, or dispositions directed by the subject matter. There can be a scaffolding approach to the overarching program curriculum when using a subject-centered approach. The subjects can be linked across courses to support collective success across the program’s curriculum. Although the instructor of the subject-centered curriculum did not typically take part in the development, they are tasked with bringing the course content to life by adding additional resources, examples, and professional experiences to the course curriculum. Now that we have discussed the various educational delivery settings, the motivation for integrating technologies, impact of instructional practices, and curriculum development models, we can consider the application of learning telecommunication technologies.

Learning Telecommunication Technologies

As telecommunication technologies have advanced, the integration of asynchronous counseling and telehealth is changing the landscape of the profession. Although there are state-specific definitions of the term, in sum telehealth refers to providing technology-assisted health care from a distance (Lerman et al., 2017). These changes in the counseling profession force us to consider the needs and the impact of the level of formal integration of technology skills training or practice in a counselor education program. This alone may begin to separate counselor education programs along the educational delivery settings continuum.

Using the traditional education category as our foundational approach for counselor education, we can see the parallels between the in-person synchronous experiences in the classroom and in counseling sessions. Professional counselors of the 21st century now need to be equipped with skills using and maneuvering technologies for communicating, documenting, and billing. Technology skills have received limited attention in the current CACREP standards as only five core standards and seven specialty standards mention technology. Technology is not mentioned in the specialty standards for Addiction Counseling; Clinical Mental Health Counseling; College Counseling and Student Affairs; Marriage, Couple, and Family Counseling; or School Counseling. There is one mention of technology for the doctoral program specialty standards (CACREP, 2015). Conversely, all 50 states in the United States have laws related to practicing telehealth (Lerman et al., 2017). The limited number of program accreditation standards that include technology neglects the current and future needs of professional counselors. Professional counselors are taxed with learning the required technological skills on the job instead of while enrolled as a student in their counselor education programs.

Student Considerations

A key factor in content delivery decisions is considering the type of learner the program will serve. The motivation, synchronicity level, and design approach all guide how successful a student will be. Not all students can be successful in every type of educational delivery setting. When considering synchronicity, the teacher-centered approach often is dependent on a greater percentage of synchronicity, while the subject-centered approach has flexibility in the percentage of synchronicity needed to effectively deliver the content. The choice in curriculum design approach also relates to the type of learner that the program attempts to serve. Yukselturk and Bulut’s (2007) description of the self-regulated learner summarizes the qualities of a learner that can be more successful with a greater percentage of asynchronous work. We also need to consider the comparative processes in a counselor-in-training’s development through a program of study.

Student Development in Online Education

Assessment of Skills and Dispositions

Assessment of skills and dispositions is a critical element of any counselor training program. The assessment process ensures that students have received the necessary training to demonstrate the skills and dispositions required to work with the public. The sections below will highlight a few of the ways student assessment is currently addressed within programs with online components.

Skills

Regardless of format, the key to effectively developing clinical skills in counselor trainees begins with intention. There are many shared approaches to teaching skills and techniques to counselor trainees in both online and traditional university settings. The nuances of online skills evaluation often begin with student access. Whereas traditional training programs have direct access to students in class and often do things like role-plays, practice sessions, and mock session evaluation in person, online programs do these in differing ways. There is a heavier reliance on technology to help facilitate exposure, practice, and assessment at a distance. This is demonstrated with greater use of podcasts, video clips, and video interfaces (Cicco, 2011). Additionally, there is a stronger need for well-developed relationships between students, faculty, and supervisors (Cicco, 2012). This strengthens the communication process and allows for more familiarity between the student and evaluators. It also allows for increased positive feedback, which can help reduce student anxiety and increase skill competency among counselor trainees in an online setting (Aladağ et al., 2014).

Fully online programs and some hybrid models often include synchronous activities, such as weekly course practice sessions, whereby students will meet via video technology and practice in front of the class or through a recorded session that can be viewed by the instructor at a later date. Feedback is an important part of this process and often includes both peer feedback, in the form of observation notes or class discussion, as well as notes or scaled assessments or rubrics provided to the student by the instructor (Cicco, 2011). This type of feedback is generally formative, which allows counselor trainees the opportunity to practice skills that are required by the program with a high level of frequency and relatively low stakes. Final course or summative evaluations often reflect a student’s combined skills practice demonstration and growth across the term.

Another frequently utilized form of skills assessment in online education is a residency model. In this training format, students gather in person with program faculty for a designated time (often 5–7 days) to complete specific skills-related training. Here, students may receive a combination of skills-based practice, faculty demonstrations, and skills- and content-based lectures. Within this format, skill development is specifically highlighted and opportunities to practice and receive real-time formative feedback are included. These in-person experiences are often evaluated in a summative manner at the conclusion of the experience with some form of established skills evaluation form. Determinations for additional skills training or remediation are often made at this point as well.

Dispositions

Much like skills assessment, dispositional assessment is a key function of counselor training programs and a requirement in the 2016 CACREP standards (CACREP, 2015). However, while skills are more behavior-based and observable, dispositional assessment often requires faculty and administrators to make judgments on student characteristics that are more abstract and difficult to define (Eells & Rockland-Miller, 2010; Homrich, 2009). Coupled with this is the fact that within the counseling profession, there are currently no specifically designed dispositional competencies (Homrich et al., 2014; Rapp et al., 2018). The result is that residence-based programs, as well as those online, are faced with the challenge of generating and operationalizing key dispositional characteristics within their counseling programs and in determining solid methods for assessment.

While challenging to establish, there have been programs that have made their disposition development process available to the broader counseling profession (Spurgeon et al., 2012). Additionally, Homrich et al. (2014) conducted a study with 82 counselor educators and supervisors from CACREP-accredited programs to better determine what dispositional characteristics are most valued in the counseling profession. Their results indicated three primary clusters of behavior specific to counselor disposition: (a) professional behaviors, (b) interpersonal behaviors, and (c) intrapersonal behaviors, with an emphasis on things like maintaining confidentiality, respecting the values of others, demonstrating cultural competence, and having an awareness of how personal beliefs impact performance. Similarly, Brown (2013) proposed the domains of (a) professional responsibility, (b) professional competence, (c) professional maturity, and (d) professional integrity, with associated behaviors within each domain. Many of these behaviors are indicated in the Counseling Competencies Scale, which has a specific section on counselor disposition (Swank et al., 2012). Having this psychometrically tested and sound assessment certainly aids in the process of assessing dispositions, whether online or in a traditional university setting.

Despite having some degree of guidance on dispositions and how to assess them, the unique elements of online education similarly reflect what was noted in the skills section—a lack of direct access to students, which alters the ability to assess formally and informally on already abstract concepts. While obvious or visibly present in a traditional classroom, interaction can be hidden behind a computer screen in the online setting. As a result, online-based programs often get around this limitation by creating opportunities to challenge students’ thinking and belief systems as well as enhancing awareness of key triggers and blind spots. Within the classroom, specific efforts can be made to create assignments in which students will face dilemmas and varied cultural experiences. Similarly, students can be asked to role-play certain characters or serve as the counselor to clients who may be perceived as controversial. These types of activities allow online counselor educators to first evaluate the responses students have, as well as to gauge openness to feedback if concerns arise in the initial response. Residency or other synchronous experiences, like video-based synchronous classrooms, afford faculty the chance to see and work with students on an interpersonal level. They also allow students to interact with one another and in some cases receive feedback from one another. Much like in the classroom, faculty members are then able to assess students on the interactions as well as on how students respond to specific feedback.

One area that is unique to online education and dispositional assessment is that of cyber incivility. De Gagne et al. (2016) defined cyber incivility as “a direct and indirect interpersonal violation involving disrespectful, insensitive, or disruptive behavior of an individual in an electronic environment that interferes with another person’s personal, professional, or social well-being, as well as student learning” (p. 240). Because online education programs rely so heavily on written electronic communication, both in the classroom and through email, there is a growing need for evaluation of interpersonal interactions in written online formats. Students who would otherwise never come into their faculty member’s office and disparage them face-to-face, or speak offensively to another student in a traditional classroom, might not struggle to do so when online. As a result, online education programs need to fine-tune the way they operationalize certain dispositional characteristics and otherwise make more formal evaluations of things like tone and messaging in written communication and interpersonal interactions. Recommendations to best address this include heightening students’ awareness of cyber incivility in both the curriculum and programmatic policies and communication (De Gagne et al., 2016), and assessing for cyber incivility as part of a dispositional evaluation. These types of assessment practices ultimately help online programs in the broader area of professional gatekeeping.

Gatekeeping

Gatekeeping is a fundamental part of the counselor training process and is mandated by section F.6.b. of the American Counseling Association’s ACA Code of Ethics (2014). As defined by the ACA Code of Ethics, gatekeeping is “the initial and ongoing academic, skill, and dispositional assessment of students’ competency for professional practice, including remediation and termination as appropriate” (2014, p. 20). It therefore includes both the assessment and evaluation process of each counselor trainee, but also the need for appropriate remediation, support, and dismissal by the programs that support them. In addition to the ethical mandate for gatekeeping, significant litigation in counseling programs (Hutchens et al., 2013) and a greater emphasis on assessment and gatekeeping in the CACREP 2016 standards (CACREP, 2015) have fostered a real need for programs of all types to firm up the gatekeeping process.

Gatekeeping is well addressed in the counseling literature, including the need for programs to create transparent performance assessment policies and practices that are explicitly communicated to students and to which students can respond (Brown-Rice & Furr, 2016; Foster & McAdams, 2009; Rapp et al., 2018). Ziomek-Daigle and Christensen (2010) proposed that there are four phases to the gatekeeping process: (a) preadmission screening, in which potential students are evaluated on key metrics prior to admission; (b) postadmission screening, in which actively enrolled students are evaluated and monitored on academic aptitude as well as interpersonal reactions; (c) remediation plan, in which students requiring remediation are provided intensified supervision and personal development; and (d) remediation outcome, in which students are evaluated on their remediation efforts and determined to be successful or not. The value of these proposed frameworks and theories is that they can be adapted and used to support the gatekeeping process of all counseling programs, regardless of the format. This is particularly valuable when as many as 10% of students in counseling programs may be deficient in skills, abilities, or dispositions and ill-suited for the profession (Brown-Rice & Furr, 2016).

In online education, the process of gatekeeping can look very similar to traditional programs, but it often requires a specific or altered set of practices to support its students. First, though not always the case, many online programs have an open- or broad-access admissions policy. This means that while certain minimal requirements have to be met (e.g., GPA, letters of recommendation, goal statement) at the preadmissions phase, other more traditional prescreening steps, such as student interviews (Swank & Smith-Adcock, 2014; Ziomek-Daigle & Christensen, 2010), may not be included. The byproduct of this may mean that there is a heightened level of gatekeeping required at the other phases: postadmission screening, remediation plan, and remediation outcome (Ziomek-Daigle & Christensen, 2010). This often results in the need for more faculty support related to the remediation process itself, as well as the need for very clear policies and practices related to remediation and dismissal that are consistently applied across a larger group of students.

While there is a call for all programs to make explicit policies and practices related to the gatekeeping process (Hutchens et al., 2013), online education programs have a heightened responsibility to overly communicate these practices. Students in online programs often are required to do much of their coursework on their own as well as attend and complete orientations and information sessions via electronic formats. The lack of direct contact with students means that online programs need to be more overt with policy messaging and provide repeated exposure to gatekeeping practices so that students stay informed. Often this is done via classroom announcements, email messaging, and course- or program-based requirements in which they must sign statements or acknowledgement forms indicating they have read and understand specific policies.

As remediation needs develop through the gatekeeping process, one of the fundamental needs of distance-based programs is strong collaboration and consultation among faculty and administration. Faculty with student concerns need the outlet and opportunity to connect with their colleagues to address potential issues and determine if issues are isolated. This is not unlike what occurs in traditional programs; however, the mechanisms for communication can differ, requiring more phone calls, tracking of email communication, and increased documentation in shared electronic records platforms. Problematic behaviors can be hard to parse out (Brown, 2013; Brown-Rice & Furr, 2016) regardless of setting, but can be increasingly challenging to identify online. Having these types of opportunities to connect with colleagues and track student issues is imperative to good remediation in an online setting.

Similarly, there is often the need for remediation committees in online programs. These committees generally include faculty and leadership within the program that work specifically to address the remediation needs of identified students. They can be content-specific—focusing solely on skills remediation or dispositional remediation—or they can serve both functions. While some traditional counseling programs have remediation committees (Brown, 2013), online programs often serve a significant number of students, which can translate to a higher number of students requiring remediation and support. Having a formalized process in place that is guided by a remediation or student support committee can be invaluable to this type of load.

Conclusion

When comparing program delivery and instructional variance between CACREP-accredited online and traditional counselor training programs, it is clear there are distinct similarities and differences. While the literature included debate regarding the appropriateness of an online environment for training counselors, research supports online counselor education training as effective for skill and professional identity development, despite requiring different instructional practices than traditional classrooms. Similarities between both settings also include a student body made up of adults, with a higher enrollment of Caucasian female students. However, online programs show greater diversity within their student body with higher numbers of non-traditional and underserved populations. One significant difference in online and traditional settings was attrition rates, which were higher for online programs, and research suggests that the social interaction that is a routine part of traditional training could hold a key to successful program completion for online learners. Future implications for counselor education are the expansion of empirically based curriculum development approaches that not only engage students but promote increased connection with the material, faculty, and peer learning communities. Another critical future direction of the counseling profession that has implications for both educational environments is the formal integration of technology skills training into the curriculum. While the academic core content areas are aligned for both settings, telehealth is rapidly changing the required skill sets for counselors to include communicating, documenting, and billing clients through electronic means.

Online counseling programs are growing in number and type, with many traditional programs now offering courses or full-program offerings at a distance. The increasing demand for this delivery model ultimately means more students will be trained at a distance, with an ever-increasing need to ensure appropriate assessment and gatekeeping practices. Faculty and administrators must be mindful of developing strong processes around admissions, student developmental assessment, remediation, and, where necessary, dismissal. Visual technology and simulation experiences are already being used by many online programs and will continue to grow and diversify as students seek new ways and opportunities to train at a distance. As more programs adopt online courses or curriculum, it is important that those programs, and the larger university systems that support them, are equipped to provide necessary training in the most effective and meaningful ways, while ensuring appropriate assessment and gatekeeping.

Finally, while conducting the review of literature for the analysis of similarities and differences between online and traditional programs, we revealed some gaps in existing research. Suggestions for future research include an investigation of instructional practices within online settings inclusive of delivery methods specific to asynchronous learning. Research indicates that attrition rates are higher for online programs, but it would be useful for researchers to investigate variables that contribute to attrition in online counseling students. Similarly, a meta-analysis of remediation practices as well as a qualitative inquiry of successful remediation efforts from both the faculty and student perspective may provide useful information in closing the gap for degree completion between online and traditional students. Finally, with the growing demand for technology literacy, the development of technology competencies for professional counselors could prove very useful for both curriculum development and counselor supervisors in facilitating success in developing professionals.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Aladağ, M., Yaka, B., & Koç, İ. (2014). Opinions of counselor candidates regarding counseling skills training. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14, 879–886. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2014.3.1958

Allen, I. E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R. & Straut, T. T. (2016). Online report card: Tracking online education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group. https://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/onlinereportcard.pdf

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics.

Barril, L. (2017). The influence of student characteristics on the preferred ways of learning of online college students: An examination of cultural constructs. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/oils_etds/41

Barrio Minton, C. A., Wachter-Morris, C. A., & Yaites, L. D. (2014). Pedagogy in counselor education: A 10-year content analysis of journals. Counselor Education & Supervision, 53, 162–177.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00055.x

Brown, M. (2013). A content analysis of problematic behavior in counselor education programs. Counselor Education & Supervision, 52(3), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00036.x

Brown-Rice, K. A., & Furr, S. (2016). Counselor educators and students with problems of professional competence: A survey and discussion. The Professional Counselor, 6, 134–146. https://doi.org/10.15241/kbr.6.2.134

Burton, L. D. (2010). Subject-centered curriculum. In C. Kridel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of curriculum studies (pp. 824–825). SAGE.

Buzwell, S., Farrugia, M., & Williams, J. (2016). Students’ voice regarding important characteristics of online and face-to-face higher education. Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain & Culture, 12, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.7790/sa.v12i1.430

Cicco, G. (2011). Assessment in online courses: How are counseling skills evaluated? i-manager’s Journal of Educational Technology, 8(2), 9–15. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1102103.pdf

Cicco, G. (2012). Counseling instruction in the online classroom: A survey of student and faculty perceptions. i-manager’s Journal on School Educational Technology, 8(2), 1–10. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1101712.pdf

Cicco, G. (2013a). Online course effectiveness: A model for innovative research in counselor education. i-manager’s Journal on School Educational Technology, 9, 10–16.

Cicco, G. (2013b). Strategic lesson planning in online courses: Suggestions for counselor educators. i-manager’s Journal on School Educational Technology, 8(3), 1–8.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2018). CACREP vital statistics 2017: Results from a national survey of accredited programs.

De Gagne, J. C., Choi, M., Ledbetter, L., Kang, H. S., & Clark, C. M. (2016). An integrative review of cybercivility in health professions education. Nurse Educator, 41, 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000264

DiRamio D., & Wolverton, M. (2006). Integrating learning communities and distance education: Possibility or pipedream? Innovative Higher Education, 31(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-006-9011-y

Dole, S., Bloom, L., & Kowalske, K. (2016). Transforming pedagogy: Changing perspectives from teacher-centered to learner-centered. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 10(1).

https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1538

Eells, G. T., & Rockland-Miller, H. S. (2010). Assessing and responding to disturbed and disturbing students: Understanding the role of administrative teams in institutions of higher education. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 25, 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2011.532470

Ellis, R. A., & Bliuc, A.-M. (2019). Exploring new elements of the student approaches to learning framework: The role of online learning technologies in student learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 20, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417721384

Lerman, A. F., Kim, D., & Ozinal, F. (2017). 50-State survey of telemental/telebehavioral health. https://www.ebglaw.com/telehealth-telemedicine/news/telemental-and-telebehavioral-health-considerations-a-50-state-analysis-on-the-development-of-telehealth-policy/

Foster, V. A., & McAdams, C. R., III. (2009). A framework for creating a climate of transparency for professional performance assessment: Fostering student investment in gatekeeping. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48(4), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00080.x

Hedén, L., & Ahlstrom, L. (2016). Individual response technology to promote active learning within the caring sciences: An experimental research study. Nurse Education Today, 36, 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.10.010

Homrich, A. (2009). Gatekeeping for personal and professional competence in graduate counseling programs. Counseling and Human Development, 41, 1–24.

Homrich, A. M., DeLorenzi, L. D., Bloom, Z. D., & Godbee, B. (2014). Making the case for standards of conduct in clinical training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53(2), 126–144.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00053.x

Hutchens, N., Block, J., & Young, M. (2013). Counselor educators’ gatekeeping responsibilities and students’ first amendment rights. Counselor Education and Supervision, 52(2), 82–95.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00030.x

Kebble, P. G. (2017). Assessing online asynchronous communication strategies designed to enhance large student cohort engagement and foster a community of learning. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 5(8), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v5i8.2539

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Hershey, K., & Peruski, L. (2004). With a little help from your students: A new model for faculty development and online course design. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 12, 25–55.

Kumar, P., Kumar, A., Palvia, S., & Verma, S. (2019). Online business education research: Systematic analysis and a conceptual model. The International Journal of Management in Education, 17, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2018.11.002

Lu, H. (2017). How can effective online interactions be cultivated? Journal of Modern Education Review, 7, 557–567. https://doi.org/10.15341/jmer(2155-7993)/08.07.2017/003

Lucas, K., & Murdock, J. (2014). Developing an online counseling skills course. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design, 4(2), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijopcd.2014040104

Marchand, G. C., & Gutierrez, A. P. (2012). The role of emotion in the learning process: Comparisons between online and face-to-face learning settings. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(3), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.10.001

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Andragogy. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictiona

ry/andragogy

Murdock, J. L., & Williams, A. M. (2011). Creating an online learning community: Is it possible? Innovative Higher Education, 36, 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-011-9188-6

Office of Federal Student Aid. (2017). Federal student aid handbook. U.S. Department of Education.

Office of Postsecondary Education Accreditation Division. (2012). Guidelines for preparing/reviewing petitions and compliance reports. U.S. Department of Education. https://www.asccc.org/sites/default/files/USDE%20_agency-guidelines.pdf

Onodipe, G. O., Ayadi, M. F., & Marquez, R. (2016). The efficient design of an online course: Principles of economics. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 17, 39–50.

O’Shea, S., Stone, C., & Delahunty, J. (2015). “I ‘feel’ like I am at university even though I am online.” Exploring how students narrate their engagement with higher education institutions in an online learning environment. Distance Education, 36, 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.1019970

Pinnegar, S., & Erickson, L. (2010). Teacher-centered curriculum. In C. Kridel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies (pp. 848–849). SAGE.

Rapp, M. C., Moody, S. J., & Stewart, L. A. (2018). Becoming a gatekeeper: Recommendations for preparing doctoral students in counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 8, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.15241/mcr.8.2.190

Snow, W. H., & Coker, J. K. (2020). Distance counselor education: Past, present, and future. The Professional Counselor, 10, 40–56. https://doi.org/10.15241/whs.10.1.40

Snow, W. H., Lamar, M., Hinkle, J. S., & Speciale, M. (2018). Current practices in online counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 8, 131–145. https://doi.org/10.15241/whs.8.2.131

Spurgeon, S. L., Gibbons, M. M., & Cochran, J. L. (2012). Creating personal dispositions for a professional counseling program. Counseling and Values, 57, 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2012.00011.x

Swank, J. M., Lambie, G. W., & Witta, E. L. (2012). An exploratory investigation of the Counseling Competencies Scale: A measure of counseling skills, dispositions, and behaviors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51(3), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00014.x

Swank, J. M., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2014). Gatekeeping during admissions: A survey of counselor education programs. Counselor Education & Supervision, 53, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00048.x

Taylor, J. Z., & Baltrinic, E. R. (2018). Teacher preparation, teaching practice, and teaching evaluation in counselor education: Exploring andragogy in counseling. Wisconsin Counseling Journal, 31, 25–38.

Yükseltürk, E., & Bulut, S. (2007). Predictors for student success in an online course. Educational Technology & Society, 10(2), 71–83.

Ziomek-Daigle, J., & Christensen, T. M. (2010). An emergent theory of gatekeeping practices in counselor education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00040.x

Laura Haddock, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC-S, is a clinical faculty member at Southern New Hampshire University. Kristi Cannon, PhD, NCC, LPC, is a clinical faculty member at Southern New Hampshire University. Earl Grey, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, ACS, BC-TMH, LMHC, LPC, is an associate dean at Southern New Hampshire University. Correspondence can be addressed to Laura Haddock, 3100 Oakleigh Lane, Germantown, TN 38138, l.haddock@snhu.edu.

Jun 28, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 2

William H. Snow, Margaret R. Lamar, J. Scott Hinkle, Megan Speciale

The Council for Accreditation of Counseling & Related Educational Programs (CACREP) database of institutions revealed that as of March 2018 there were 36 CACREP-accredited institutions offering 64 online degree programs. As the number of online programs with CACREP accreditation continues to grow, there is an expanding body of research supporting best practices in digital remote instruction that refutes the ongoing perception that online or remote instruction is inherently inferior to residential programming. The purpose of this article is to explore the current literature, outline the features of current online programs and report the survey results of 31 online counselor educators describing their distance education experience to include the challenges they face and the methods they use to ensure student success.

Keywords: online, distance education, remote instruction, counselor education, CACREP

Counselor education programs are being increasingly offered via distance education, or what is commonly referred to as distance learning or online education. Growth in online counselor education has followed a similar trend to that in higher education in general (Allen & Seaman, 2016). Adult learners prefer varied methods of obtaining education, which is especially important in counselor education among students who work full-time, have families, and prefer the flexibility of distance learning (Renfro-Michel, O’Halloran, & Delaney, 2010). Students choose online counselor education programs for many reasons, including geographic isolation, student immobility, time-intensive work commitments, childcare responsibilities, and physical limitations (The College Atlas, 2017). Others may choose online learning simply because it fits their learning style (Renfro-Michel, O’Halloran, & Delaney, 2010). Additionally, education and training for underserved and marginalized populations may benefit from the flexibility and accessibility of online counselor education.

The Council for Accreditation of Counseling & Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015) accredits online programs and has determined that these programs meet the same standards as residential programs. Consequently, counselor education needs a greater awareness of how online programs deliver instruction and actually meet CACREP standards. Specifically, existing online programs will benefit from the experience of other online programs by learning how to exceed and surpass minimum accreditation expectations by utilizing the newest technologies and pedagogical approaches (Furlonger & Gencic, 2014). The current study provides information regarding the current state of online counselor education in the United States by exploring faculty’s descriptions of their online programs, including their current technologies, student and program community building approaches, and challenges faced.

Distance Education Defined

Despite its common usage throughout higher education, the U.S. Department of Education (DOE) does not use the terms distance learning, online learning, or online education; rather, it has adopted the term distance education (DOE, 2012). However, in practice, the terms distance education, distance learning, online learning, and online education are used interchangeably. The DOE has defined distance education as the use of one or more technologies that deliver instruction to students who are separated from the instructor and that supports “regular and substantive interaction between the students and the instructor, either synchronously or asynchronously” (2012, p. 5). The DOE has specified that technologies may include the internet, one-way and two-way transmissions through open broadcast and other communications devices, audioconferencing, videocassettes, DVDs, and CD-ROMs. Programs are considered distance education programs if at least 50% or more of their instruction is via distance learning technologies. Additionally, residential programs may contain distance education elements and still characterize themselves as residential if less than 50% of their instruction is via distance education. Traditional on-ground universities are incorporating online components at increasing rates; in fact, 67% of students in public universities took at least one distance education course in 2014, further reflecting the growth in this teaching modality (Allen & Seaman, 2016).

Enrollment in online education continues to grow, with nearly 6 million students in the United States engaged in distance education courses (Allen & Seaman, 2016). Approximately 2.8 million students are taking online classes exclusively. In a conservative estimate, over 25% of students enrolled in CACREP programs are considered distance learning students. In a March 2018 review of the CACREP database of accredited institutions, there were 36 accredited institutions offering 64 degree programs. Although accurate numbers are not available from any official sources, it is a conservative estimate that over 12,000 students are enrolled in a CACREP-accredited online program. When comparing this estimate to the latest published 2016 CACREP enrollment figure of 45,820 (CACREP, 2017), online students now constitute over 25% of the total. This does not include many other residential counselor education students in hybrid programs who may take one or more classes through distance learning means.

At the time of this writing, an additional three institutions were currently listed as under CACREP review, and soon their students will likely be added to this growing online enrollment. As this trend continues, it is essential for counselor education programs to understand issues, trends, and best practices in online education in order to make informed choices regarding counselor education and training, as well as preparing graduates for employment. It also is important for hiring managers in mental health agencies to understand the nature and quality of the training graduates of these programs have received.

One important factor contributing to the increasing trends in online learning is the accessibility it can bring to diverse populations throughout the world (Sells, Tan, Brogan, Dahlen, & Stupart, 2012). For instance, populations without access to traditional residential, brick-and-mortar classroom experiences can benefit from the greater flexibility and ease of attendance that distance learning has to offer (Bennet-Levy, Cromarty, Hawkins, & Mills, 2012). Remote areas in the United States, including rural and frontier regions, often lack physical access to counselor education programs, which limits the numbers of service providers to remote and traditionally underserved areas of the country. Additionally, the online counselor education environment makes it possible for commuters to take some of their course work remotely, especially in winter when travel can become a safety issue, and in urban areas where travel is lengthy and stressful because of traffic.

The Online Counselor Education Environment

The Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (ACES) Technology Interest Network (2017) recently published guidelines for distance education within counselor education that offer useful suggestions to online counselor education programs or to those programs looking to establish online courses. Current research supports that successful distance education programs include active and engaged faculty–student collaboration, frequent communications, sound pedagogical frameworks, and interactive and technically uncomplicated support and resources (Benshoff & Gibbons, 2011; Murdock & Williams, 2011). Physical distance and the associated lack of student–faculty connection has been a concern in the development of online counselor education programs. In its infancy, videoconferencing was unreliable, unaffordable, and often a technological distraction to the learning process. The newest wave of technology—enhanced distance education—has improved interactions using email, e-learning platforms, and threaded discussion boards to make asynchronous messaging virtually instantaneous (Hall, Nielsen, Nelson, & Buchholz, 2010). Today, with the availability of affordable and reliable technical products such as GoToMeeting, Zoom, and Adobe Connect, online counselor educators are holding live, synchronous meetings with students on a regular basis. This includes individual advising, group supervision, and entire class sessions.

It is important to convey that online interactions are different than face-to-face, but they are not inferior to an in-person faculty–student learning relationship (Hickey, McAleer, & Khalili, 2015). Students and faculty prefer one method to the other, often contingent upon their personal belief in the effectiveness of the modality overall and their belief in their own personal fit for this style of teaching and learning (Watson, 2012). In the actual practice of distance education, professors and students are an email, phone call, or videoconference away; thus, communication with peers and instructors is readily accessible (Murdock & Williams, 2011; Trepal, Haberstroh, Duffey, & Evans, 2007). When communicating online, students may feel more relaxed and less inhibited, which may facilitate more self-disclosure, reflexivity, and rapport via increased dialogue (Cummings, Foels, & Chaffin, 2013; Watson, 2012). Subsequently, faculty who are well-organized, technologically proficient, and more responsive to students’ requests may prefer online teaching opportunities and find their online student connections more engaging and satisfying (Meyer, 2015). Upon Institutional Research Board approval, an exploratory survey of online counselor educators was conducted in 2016 and 2017 to better understand the current state of distance counselor education in the United States.

Method

Participants

Recruitment of participants was conducted via the ACES Listserv (CESNET). No financial incentive or other reward was offered for participation. The 31 participants comprised a sample of convenience, a common first step in preliminary research efforts (Kerlinger & Lee, 1999). Participants of the study categorized themselves as full-time faculty members (55.6%), part-time faculty members (11.1%), academic chairs and department heads (22.2%), academic administrators (3.7%), and serving in other roles (7.4%).

Study Design and Procedure

The survey was written and administered using Qualtrics, a commercial web-based product. The survey contained questions aimed at exploring online counselor education programs, including current technologies utilized, approaches to reducing social distance, development of community among students, major challenges in conducting online counselor education, and current practices in meeting these challenges. The survey was composed of one demographic question, 15 multiple-response questions, and two open-ended survey questions. The demographic question asked about the respondent’s role in the university. The 15 multiple-response questions included items such as: (a) How does online counselor education fit into your department’s educational mission? (b) Do you provide a residential program in which to compare your students? (c) How successful are your online graduates in gaining postgraduate clinical placements and licensure? (d) What is the average size of an online class with one instructor? and (e) How do online students engage with faculty and staff at your university? Two open-ended questions were asked: “What are the top 3 to 5 best practices you believe are most important for the successful online education of counselors?” and “What are the top 3 to 5 lessons learned from your engagement in the online education of counselors?”

Additional questions focused on type of department and its organization, graduates’ acceptance to doctoral programs, amount of time required on the physical campus, e-learning platforms and technologies, online challenges, and best practices for online education and lessons learned. The 18 survey questions were designed for completion in no more than 20 minutes and the survey was active for 10 months, during which time there were three appeals for responses yielding 31 respondents.

Procedure

An initial recruiting email and three follow-ups were sent via CESNET. Potential participants were invited to visit a web page that first led to an introductory paragraph and informed consent page. An embedded skip logic system required consent before allowing access to the actual survey questions.

The results were exported from the Qualtrics web-based survey product, and the analysis of the 15 fixed-response questions produced descriptive statistics. Cross tabulations and chi square statistics further compared the perceptions of faculty and those identifying themselves as departmental chairs and administrators.

The two open-ended questions—“What are the top 3 to 5 best practices you believe are most important for the successful online education of counselors?” and “What are the top 3 to 5 lessons learned from your engagement in the online education of counselors?”—yielded 78 statements about lessons learned and 80 statements about best practices for a total of 158 statements. The analysis of the 158 narrative comments initially consisted of individually analyzing each response by identifying and extracting the common words and phrases. It is noted that many responses contained more than one suggestion or comment. Some responses were a paragraph in length and thus more than one key word or phrase could come from a single narrative response. This first step yielded a master list of 18 common words and phrases. The second step was to again review each comment, compare it to this master list, and place a check mark for each category. The third step was to look for similarities in the 18 common words and group them into a smaller number of meaningful categories. These steps were checked among the researchers for fidelity of reporting and trustworthiness.

Results

Thirty-one distance learning counselor education faculty, department chairs, and administrators responded to the survey. They reported their maximum class sizes ranged from 10 to 40 with a mean of 20.6 (SD = 6.5), and the average class size was 15.5 (SD = 3.7). When asked how online students are organized within their university, 26% reported that students choose classes on an individual basis, 38% said students are individually assigned classes using an organized schedule, and 32% indicated that students take assigned classes together as a cohort.

Additionally, respondents were asked how online students engage with faculty and staff at their university. Email was the most popular, used by all (100%), and second was phone calls (94%). Synchronous live group discussions using videoconferencing technologies were used by 87%, while individual video calls were reported by 77%. Asynchronous electronic discussion boards were utilized by 87% of the counselor education programs.

Ninety percent of respondents indicated that remote or distance counseling students were required to attend the residential campus at least once during their program, with 13% requiring students to come to campus only once, 52% requiring students to attend twice, and 26% requiring students to come to a physical campus location four or more times during their program.

All participants indicated using some form of online learning platform with Blackboard (65%), Canvas (23%), Pearson E-College (6%), and Moodle (3%) among the ones most often listed. Respondents indicated the satisfaction levels of their current online learning platform as: very dissatisfied (6.5%), dissatisfied (3.2%), somewhat dissatisfied (6.5%), neutral (9.7%), somewhat satisfied (16.1%), satisfied (41.9%), and very satisfied (9.7%). There was no significant relationship between the platform used and the level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction (X2 (18,30) = 11.036, p > .05), with all platforms faring equally well. Ninety-seven percent of respondents indicated using videoconferencing for teaching and individual advising using such programs as Adobe Connect (45%), Zoom (26%), or GoToMeeting (11%), while 19% reported using an assortment of other related technologies.

Participants were asked about their university’s greatest challenges in providing quality online counselor education. They were given five pre-defined options and a sixth option of “other” with a text box for further elaboration, and were allowed to choose more than one category. Responses included making online students feel a sense of connection to the university (62%), changing faculty teaching styles from traditional classroom models to those better suited for online coursework (52%), providing experiential clinical training to online students (48%), supporting quality practicum and internship experiences for online students residing at a distance from the physical campus (38%), convincing faculty that quality outcomes are possible with online programs (31%), and other (10%).

Each participant was asked what their institution did to ensure students could succeed in online counselor education. They were given three pre-defined options and a fourth option of “other” with a text box for further elaboration, and were allowed to choose more than one option. The responses included specific screening through the admissions process (58%), technology and learning platform support for online students (48%), and assessment for online learning aptitude (26%). Twenty-three percent chose the category of other and mentioned small classes, individual meetings with students, providing student feedback, offering tutorials, and ensuring accessibility to faculty and institutional resources.

Two open-ended questions were asked and narrative comments were analyzed, sorted, and grouped into categories. The first open-ended question was: “What are the top 3 to 5 best practices that are the most important for the successful online education of counselors?” This yielded 78 narrative comments that fit into the categories of fostering student engagement (n = 19), building community and facilitating dialogue (n = 14), supporting clinical training and supervision (n = 11), ensuring courses are well planned and organized (n = 10), providing timely and robust feedback (n = 6), ensuring excellent student screening and advising (n = 6), investing in technology (n = 6), ensuring expectations are clear and set at a high standard (n = 5), investing in top-quality learning materials (n = 4), believing that online counselor education works (n = 3), and other miscellaneous comments (n = 4). Some narrative responses contained more than one suggestion or comment that fit multiple categories.

The second open-ended question—“What are the top 3 to 5 lessons learned from the online education of counselors?”—yielded 80 narrative comments that fit into the categories of fostering student engagement (n = 11), ensuring excellent student screening and advising (n = 11), recognizing that online learning has its own unique workload challenges for students and faculty (n = 11), providing timely and robust feedback (n = 8), building community and facilitating dialogue (n = 7), ensuring courses are well planned and organized (n = 7), investing in technology (n = 6), believing that online counselor education works (n = 6), ensuring expectations are clear and set at a high standard (n = 5), investing in top-quality learning materials (n = 3), supporting clinical training and supervision (n = 2), and other miscellaneous comments (n = 8).

Each participant was asked how online counselor education fit into their department’s educational mission and was given three categorical choices. Nineteen percent stated it was a minor focus of their department’s educational mission, 48% stated it was a major focus, and 32% stated it was the primary focus of their department’s educational mission.

The 55% of participants indicating they had both residential and online programs were asked to respond to three follow-up multiple-choice questions gauging the success rates of their online graduates (versus residential graduates) in attaining: (1) postgraduate clinical placements, (2) postgraduate clinical licensure, and (3) acceptance into doctoral programs. Ninety-three percent stated that online graduates were as successful as residential students in gaining postgraduate clinical placements. Ninety-three percent stated online graduates were equally successful in obtaining state licensure. Eighty-five percent stated online graduates were equally successful in getting acceptance into doctoral programs.

There were some small differences in perception that were further analyzed. Upon using a chi square analysis, there were no statistically significant differences in the positive perceptions of online graduates in gaining postgraduate clinical placements (X2 (2, 13) = .709, p > .05), the positive perceptions regarding the relative success of online versus residential graduates in gaining postgraduate clinical licensure (X2 (2, 13) = .701, p > .05), or perceptions of the relative success of online graduates in becoming accepted in doctoral programs (X2 (2, 12) = 1.33, p > .05).

Discussion

The respondents reported that their distance learning courses had a mean class size of 15.5. Students in these classes likely benefit from the small class sizes and the relatively low faculty–student ratio. These numbers are lower than many residential classes that can average 25 students or more. It is not clear what the optimal online class size should be, but there is evidence that the challenge of larger classes may introduce burdens difficult for some students to overcome (Chapman & Ludlow, 2010). Beattie and Thiele (2016) found first-generation students in larger classes were less likely to talk to their professor or teaching assistants about class-related ideas. In addition, Black and Latinx students in larger classes were less likely to talk with their professors about their careers and futures (Beattie & Thiele, 2016).

Programs appeared to have no consistent approach to organizing students and scheduling courses. The three dominant models present different balances of flexibility and predictability with advantages and disadvantages for both. Some counselor education programs provide students the utmost flexibility in selecting classes, others assign classes using a more controlled schedule, and others are more rigid and assign students to all classes.

The model for organizing students impacts the social connections students make with one another. In concept, models that provide students with more opportunities to engage each other in a consistent and effective pattern of positive interactions result in students more comfortable working with one another, and requesting and receiving constructive feedback from their peers and instructors.

Cohort models, in which students take all courses together over the life of a degree program, are the least flexible but most predictable and have the greatest potential for fostering strong connections. When effectively implemented, cohort models can foster a supportive learning environment and greater student collaboration and cohesion with higher rates of student retention and ultimately higher graduation rates (Barnett & Muse, 1993; Maher, 2005). Advising loads can decrease as cohort students support one another as informal peer mentors. However, cohorts are not without their disadvantages and can develop problematic interpersonal dynamics, splinter into sub-groups, and lead to students assuming negative roles (Hubbell & Hubbell, 2010; Pemberton & Akkary, 2010). An alternative model in which students make their own schedules and choose their own classes provides greater flexibility but fewer opportunities to build social cohesion with others in their program. At the same time, these students may not demonstrate the negative dynamics regarding interpersonal engagement that can occur with close cohort groups.

Faculty–Student Engagement

Remote students want to stay in touch with their faculty advisors, course instructors, and fellow students. Numerous social engagement opportunities exist through technological tools including email, cell phone texts, phone calls, and videoconference advising. These fast and efficient tools provide the same benefits of in-person meetings without the lag time and commute requirements. Faculty and staff obviously need to make this a priority to use these tools and respond to online students in a timely manner.