Oct 6, 2014 | Article, Volume 2 - Issue 2

Yuh-Jen Guo, Shu-Ching Wang, Shelly R. Statz, Craig Wynne

Growing individual access to the Internet helps universities take advantage of academic webpages to showcase unique characteristics and recruit prospective students. This study explored how the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) accredited counseling programs have utilized their program webpages for similar purposes. Results indicate many deficiencies existing in the contents of webpages hosted by CACREP counselor education programs.

Keywords: CACREP, accreditation, webpages, internet, counselor education

The world is moving to the rhythm of the Internet at a very fast pace. Thirty percent of the world population connects to the Internet, 78.3% of the North American population is online, and the usage of the Internet has increased 480.4% in the past 10 years (Miniwatts Marketing Group, 2011). In 2010, the Internet surpassed the television as the “essential medium” (Edison Research, 2010), whereas social network websites connected 77% of the population 18–24 years old (Edison Research, 2010). Webpages have become the virtual venue of information inquiry and socialization.

The counseling profession also rode the surge in Internet technology. Sampson, Kolodinsky, and Greeno (1997) foresaw several potential uses of the Internet in counseling. The marketing and delivery of various counseling services online, as well as supervision and research were identified by these authors as emerging areas for online counseling practices. To date, career exploration (American College Testing, n.d.; Sampson, 1999) has been moved from traditional page flipping to web browsing. Counseling has been effectively practiced online in the specialties of career counseling (Gati & Asulin-Peretz, 2011), college counseling (Derek, 2009; Quartoa, 2011), supervision (Chapman, Baker, Nassar-McMillan, & Gerler, 2011; Nelson, Nichter, & Henriksen, 2010), mental health counseling (Heinlen, Reynolds-Welfel, Richmond, & Rak, 2003; Mallen, Vogel, & Rochlen, 2005), self-help groups (Finn & Steele, 2010), and counselor education (Benshoff & Gibbons, 2011; Rockinson-Szapkiw, Baker, Neukrug, & Hanes, 2010).

A prominent feature of the Internet is the information super highway that provides tremendous materials online for information searching and inquiry (Kinka & Hessa, 2008). Universities and colleges take advantage of the Internet and publicize institutional information online through their webpages (Middleton, McConnell, & Davidson, 1999). Students now have the opportunity to access facts about a prospective university and academic program in which they are interested (Poock & Lefond, 2001, 2003). The current functions of university webpages have been extended beyond the online showcase to the active role of public relations (Gordon & Berhow, 2009) and student recruitment (Kittle & Ciba, 2001; Poock & Lefond, 2001, 2003). However, there is a need to increase research on the actual effectiveness of university websites in satisfying the prospective users (Middleton et al., 1999).

Very little attention has been devoted to the study of the use of the graduate counseling programs’ webpages (McGlothlin, West, Osborn, & Musson, 2008), even though the use of the Internet has become popular in various aspects of counseling training and practices. McGlothlin, West, Osborn, and Musson (2008) noted the potential capacity of counseling programs’ webpages as online marketing tools and conducted a review of webpages for 187 CACREP-accredited counseling programs. Their results indicated various deficiencies, such as missing CACREP accreditation information. This study reviewed the webpages of all CACREP-accredited counseling programs in order to examine the essential published information and to explore possible deficiencies which may prevent these webpages from being effective marketing tools for prospective students.

Method

CACREP Webpages

All CACREP-accredited counseling programs listed on the CACREP directory page (CACREP, n.d.) were used in this study. It was important to point out that one counseling department could house multiple accredited counseling programs; hence these counseling programs would share the departmental webpages. Few universities had multiple campuses where independent counseling programs were operating. The review criteria was to count each set of webpages for one content review even though there might be two or three accredited counseling programs sharing the same departmental webpages. Counseling programs in different campuses were counted separately when they were listed as different accredited programs on the CACREP directory.

A total number of 220 departmental webpages were reviewed. Within these 220 departments, researchers reviewed webpage contents covering 528 CACREP-accredited counseling programs. There were 42 institutions with 66 CACREP-accredited programs not accessible either from the CACREP directory list or the main institutional webpages. During the research process, multiple attempts to access the webpages of these 66 counseling programs had failed, and these programs were subsequently excluded from this study.

Procedure

A list of CACREP-accredited programs was retrieved from the CACREP directory page (CACREP, n.d.) during the 2009–2010 academic years. This directory provided links to all CACREP program webpages. When the links on the directory were not accurate or up-to-date, online search engines, including Google and Yahoo, were used to access program webpages. This route took researchers to the institutional webpages or the departmental webpages. In some cases, researchers were able to find the counseling program webpages through institutional or departmental webpages. Some program webpages were not able to be located after multiple attempts.

Two graduate students were trained as webpage reviewers. They went over a couple of webpages with researchers to become familiar with the process of reviewing webpage contents and determining the major content categories. One reviewer took an academic semester to examine all program webpages. The first reviewer began with the contents of several program webpages to create a list of major content categories from those webpages. This reviewer then presented the categories, such as “program mission” and “current student,” to the researchers. The category presentation was held to verify the efficiency and accuracy of the reviewer. Throughout the review process, the reviewer remained in constant communication with researchers and discussed unclear webpage contents with researchers to determine how to categorize such contents. The second reviewer followed the exact same links to review all CACREP program webpages independently and she compared her review results with those of the first reviewer to verify the accuracy of the recorded data. The second reviewer took another academic semester to complete this task. Both reviewers continued to access the program webpages with broken links on CACREP directory. They tried to locate these webpages through the institutional and departmental webpages. Those inaccessible webpages of counseling programs were excluded from this study.

The major content categories were determined on those common webpage headlines and information grouped in sections or links for prospective users. The common headlines included topics such as program mission and program description. Essential information included sections such as program contact information and the links for current students or faculty and staff. Many universal terms, such as mission and department contact, were used across the majority of program webpages. When reviewers encountered webpage contents they were not certain about how to categorize, they brought these contents to discuss with researchers in order to determine the categories for these contents. Reviewers were counting what common headlines were published on any given program webpages. Either these common headlines were listed on webpages or they were not. Essential information might contain additional contents that reviewers needed to count the accessible numbers. For example, one program webpage could list seven full-time faculty members, but it only provided three links to access three faculty’s publication records. In this case, there would be a “7” on the faculty count and a “3” on faculty publication.

Data Analysis Process

As explained in the procedure and methods section, two types of data were eventually collected in the review process. A set of nominal data was generated from reviewers’ examination on common headlines or essential information in webpage contents. The nominal data was coded as “0” and “1” to represent whether or not one headline or information existed on a particular webpage. For example, when reviewers were able to see the mailing address on one webpage, they would mark a “1” on the category of program mailing address. Nominal data could be tallied for total numbers. Another set of data was the interval data acquired by counting the numbers listed under one category. A total of 28 major categories were compiled by reviewers.

A careful examination of these 28 categories allowed researchers to group them into three content domains: program, faculty, and students. Each of the three domains contained a number of categories delivering essential information for that domain. For example, the program domain would contain categories such as mailing address, e-mail address, and mission, which all related to what the program was about. Based on the different qualities of the two data types and the purposes of this study, a descriptive analysis (Creswell, 2008) was selected to describe the data sets. This procedure was used to depict the content quality of the webpages of CACREP-accredited counseling programs and reveal what could be the deficient areas on program webpages.

Results

The review process was able to access 220 program webpages (84%) from a list of 262 departments offering at least one CACREP-accredited counseling program. These 220 departmental webpages contained information for 528 CACREP-accredited counseling programs (88.9%) from 594 programs listed on CACREP directory. A total of 28 categories carrying the essential information were labeled. These categories were grouped into three domains of program, faculty and student based on the types of information presented in the categories. The program domain consisted of categorical information about the counseling program. Information in a program domain aimed to introduce a counseling program to prospective users. The faculty domain contained categorical information aimed to introduce counselor educators to prospective users. The student domain consisted of categorical information which counseling programs provided for prospective and current students, as well as alumni.

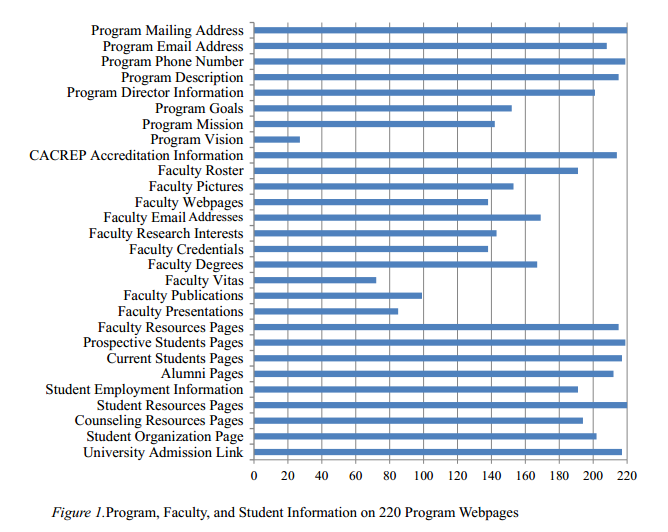

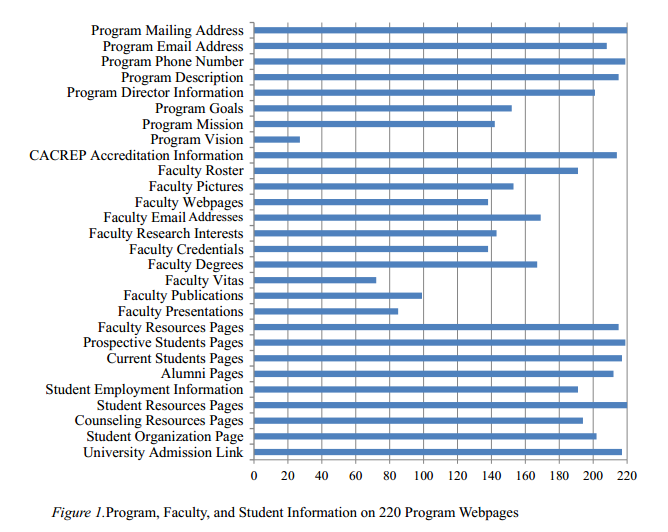

Figure 1 represents the results of our investigation on the essential information published on all accessible webpages of CACREP-accredited counseling programs. The data in Figure 1 indicated whether or not a type of essential information was displayed on program webpages and the numbers of counseling programs actually displaying the essential information.

Among the 28 major content categories, nine categories were placed under the program domain: (1) program mailing address, (2) program phone number, (3) program description, (4) CACREP accreditation information, (5) program e-mail address, (6) program director information, (7) program goals, (8) program mission, and (9) program vision. Eleven categories were grouped under the faculty domain: (1) faculty resources pages, (2) faculty roster, (3) faculty e-mail addresses, (4) faculty degrees, (5) faculty photos, (6) faculty research interests, (7) faculty webpages, (8) faculty credentials, (9) faculty publications, (10) faculty presentations, and (11) faculty vitas. Eight categories were placed under the student domain: (1) student resources pages, (2) prospective student pages, (3) current student pages, (4) university admission link, (5) alumni pages, (6) student organization page, (7) counseling resources pages, and (8) student employment information.

Among the 28 categories, two categories had a 100% accessibility rate (220 out of 220). The “student resources” and “program mailing address” were accessible on all program webpages. The category of “program vision” had the least accessibility with only 12% found on counseling program webpages. Many categories in the faculty domain appeared to have lower accessibility rates compared to those in program and student domains. Six out of 11 categories of faculty domain did not have high accessibility rates: research interests (65%), web pages (63%), credentials (63%), publications (45%), presentations (37%), and vitas (33%). Only the faculty resources pages had high accessibility (98%).

In addition to the descriptive analysis presented in Figure 1, interval data was collected and tabulated in Table 1. Table 1 displayed the counts on ten categories of the faculty domain. This table compared each category against the total number of counseling faculty listed by 528 counseling programs. There were 1,469 counselor educators listed on the counseling department webpages where the faculty was employed. However, the information in the ten categories of faculty domain did not show an equivalent accessibility across all counseling programs.

The list in Table 1 showed a ranking of faculty information available to online public access. Among the total of 220 program webpages, there were 191 webpages posting faculty rosters which could be used to count the full-time counselor educators in those departments. A total of 1,469 counselor educators were listed as full-time faculty members. Not all categories were available on all 191 program webpages. The third column displayed the numbers of program webpages allowing access to a particular category.

Among the 1,469 counselor educators, there were 1,254 e-mail addresses (85.4%) and 1,072 highest graduate degrees (73%) posted with the faculty names. Faculty photos were found on 1,004 counselor educators (68.3%), but only 875 faculty webpages (59.6%), which were used to present personalized information about counselor educators, were able to be found on program webpages. Counselor educators’ research interests were accessible for 702 faculty members (47.8%). A total of 522 counselor educators (35.5%) had displayed the professional credentials or licenses they held. The program webpages only posted the publication records of 514 counselor educators (35%) and professional presentation of 326 (22.2%). Faculty vitas were made available on 72 program webpages with a count of 337 counselor educators (22.9%).

Discussion

Webpages have become a popular media for online information disclosure and exchange (Bateman, Pike, & Butler, 2011; Tapscott & Williams, 2008). The Internet is a crucial technological tool which counseling programs are utilizing. In this study, 84% of counseling departments were accessed and 88.9% of CACREP-accredited counseling program webpages were reviewed. This percentage was close to the number (86%) reported by a previous study (Quinn, Hohenshil, & Fortune, 2002). Most counseling programs, 90% or more, listed their contact information (mailing, e-mail, phone, and program director’s contact information) as well as program description (97.7%) and CACREP accreditation information (97.3%) on their webpages. Such findings concurred with results found in a previous study indicating that a high percentage (above 75%) of contact information could be detected on department webpages (McGlothlin et al., 2008). However, our findings endorsed improved display of CACREP information (an increase from 62% to 97.3%) and program description (from 75% to 97.7%). The accessibilities of program goals, mission and vision were all below 69%, with vision being the lowest (12%). Although our findings indicated that program vision was not a common item on department webpages, students should have easy access to contacting a counseling program and identifying whether or not a program is CACREP-accredited.

Regarding faculty information, the majority of counseling programs posted faculty resource pages (97.7%) and faculty roster (87%). It was noticed that some counseling faculty members were listed within the collegial faculty roster and without a tag to identify who was a member of the counseling faculty. Table 1 also indicated that not every counselor educator had his or her essential information online for public browsing. Among the 1,469 listed counselor educators, students would be able to access the information containing faculty e-mail addresses (85.4%), highest degrees (73%), photos (68.3%), individual faculty webpages (59.6%), research interests (47.8%), licenses and credentials (35.5%), and faculty publications (35%). The lowest percentages of accessibility on faculty information were faculty vitas (22.9%) and faculty presentations (22.2%).

Our findings confirmed the high percentage of faculty contact information and the low percentage of faculty descriptions reported by a previous study (McGlothlin et al., 2008). McGlothlin et al. (2008) reported that 87.7% of webpages contained faculty contact information and 46% contained faculty description. Our study further examined the contents of faculty description and found an uneven and inconsistent style of information disclosure. It was clear that not every listed faculty member displayed all of the following information online: (1) e-mail address, (2) highest earned degrees, (3) photos, (4) personal webpages, (5) research interests, (6) credentials or licenses, (7) publications, (8) presentations, and (9) vitas. These deficiencies may potentially pose difficulties for students who access program webpages for faculty information.

Clearly, counseling programs should provide essential information for past, current and prospective students. Our results indicated that counseling programs had primarily constructed webpages with information for current and prospective students, as well as alumni. These student pages included student resources (100%), prospective students (99.5%), current students (98.6%), alumni (96.3%), and student employment (86.8%). The high percentages of accessibility demonstrated that counseling programs focused more on maintaining webpage information related to students.

Our results concluded that most counseling programs considered the main function of their webpages as a tool to communicate with students due to the high percentage of student-related webpages. On the other hand, information about counseling programs themselves had not been valued equally. The introduction of counseling programs was less focused because the program contact information obtained a high accessibility rate, but the program missions and goals were often omitted. Faculty information appeared to have an even lower emphasis on program webpages. The low accessibility of faculty information was represented by the below 50% display rate of faculty’s research interests, licenses and credentials, publications, presentations, and vitas. Our findings suggest that CACREP counseling programs concentrate their web design efforts on enriching student-related pages, but devote less effort on the construction and maintenance of webpages displaying essential information on counseling programs and their faculty. However, this would be a debatable conclusion without further investigation on counseling students’ browsing preferences.

Implications

The use of webpages in counseling programs needs more thorough research to determine how to effectively disclose and exchange essential online information to students and the public. Several critical points and questions have been raised from our research that can assist future web design in counseling programs:

1. It is important to determine what essential materials should be disclosed and exchanged on program webpages. A proper web design and the quality of information disclosure are vital criteria for effective webpages (Maddux & Johnson, 1997). Counseling programs have to carefully consider how they want to be viewed on the Internet. Who are the potential viewers of department webpages? What specific information are viewers seeking? Will the information be useful to the viewers and benefit the programs?

2. Webpage marketing must monitor its dissemination of information and web design (Poock & Bishop, 2006). Information posted on webpages should attract viewers’ attention and satisfy browsing purposes. Careful consideration of web design can provide easy access to information sought by viewers.

3. Counseling programs need to consider the value of their webpages within the university web structures. When counseling programs do not have full control of their webpages, their information dissemination and design may lack integrity. Webpage viewers look for fast and effective access to desired information (Poock & Bishop, 2006), and when viewers access program information via college or university websites, they may be discouraged by the lack of quick access.

4. Awareness of cultural factors is necessary for the design of webpages in counseling programs. Maddux, Torres-Rivera, Smaby, and Cummings (2005) repeated a study (Torres-Rivera, Maddux, & Phan, 1999) regarding multicultural counseling-related websites and concluded there were deficiencies on the display of culturally related information. Considerations for the accessibility of disabled viewers are needed since counseling program webpages might contain obstacles that hinder disabled viewers’ free access (Flowers, Bray, Furr, & Algozzine, 2002). Since the webpages are reaching an audience beyond offices and campuses, they need to include cultural sensitivity.

5. In addition to online marketing, webpages carry departmental public relations into the virtual world (Gordon & Berhow, 2009). Hill and White (2000) indicated that webpages carry the images of the programs they are representing. It is certainly not a professional appearance when items and information are missing or partially displayed on program webpages. With limited resources, counseling programs need to construct their webpages in a professional manner and formulate the webpages to distribute high quality and thorough information.

6. In light of webpage usage, new features are constantly emerging in web design. Many popular forms of online media, such as Facebook and YouTube, may certainly enrich the contents of counseling program webpages. For example, the use of images (Vilnai-Yavetz & Tiffere, 2009) and video (Audet & Paré, 2009) on webpages achieves specific advantages for viewers. In addition to information dissemination, the communication feature of webpages also is important to web design (Gordon & Berhow, 2009; Kent & Taylor, 1998). This feature allows viewers to communicate with the programs and receive timely feedback (Kent & Taylor, 1998). Counseling programs should consider incorporating these advanced features into their program webpages to better reach viewers.

It is important to make sure that webpage viewers will be able to access desired information easily on departmental webpages. Future research efforts should focus on what essential information should be displayed on counseling program webpages, as well as the satisfaction of program webpage users.

Limitations

It is important for readers to realize the potential limitations for interpretation and generalization of these research results. Webpages are frequently changed and upgraded. Subsequent improvements and revisions may dramatically change the outlook of the reviewed webpages. Our assessment should be considered a “snapshot review” since our project intended to produce a “one-shot” quantitative measurement of counseling program webpages. Less attention was paid to the quality of contents and the methods and services for information disclosure, such as video clips, and information exchange, such as message boards. Further studies on the effectiveness of various web design tools and features among counseling program webpages should be able to provide more in-depth information on effective counseling program webpage designs.

References

American College Testing. (n.d.). Discover. Retrieved from http://www.act.org/discover/index.html

Audet, C. T., & Paré, D. A. (2009). The collaborative counseling website: Using video e-learning via Blackboard Vista to enrich counselor training. In G. R. Walz, J. C. Bleuer, & R. K. Yep (Eds.), Compelling counseling interventions: VISTAS 2009 (pp. 305–315). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Bateman, P. J., Pike, J. C., & Butler, B. S. (2011). To disclose or not: Publicness in social networking sites. Information Technology & People, 24, 78–100.

Benshoff, J. M., & Gibbons, M. M. (2011). Bringing life to e-learning: Incorporating a synchronous approach to online teaching in counselor education. The Professional Counselor: Research and Practice, 1, 21–28.

Chapman, R. A., Baker, S. B., Nassar-McMillan, S. C., & Gerler, E. R. (2011). Cybersupervision: Further examination of synchronous and asynchronous modalities in counseling practicum supervision. Counselor Education & Supervision, 50, 298–313.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (n.d.). Directory. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/directory/directory.cfm

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Derek, R. (2009). Features and benefits of online counseling: Trinity College online mental health community. British Journal of Guidance & Counseling, 37, 231–242.

Edison Research. (2010). The infinite dial 2010: Digital platforms and the future of radio. Retrieved from http://www.edisonresearch.com/The_Infinite_Dial_2010.pdf

Finn, J., & Steele, T. (2010). Online self-help/mutual aid groups in mental health practice. In L. D. Brown, & S. Wituk (Eds.), Mental health self-help: Consumer and family initiatives (pp. 87–106). New York, NY: Springer.

Flowers, B. P., Bray, M., Furr, S., & Algozzine, R. F. (2002). Accessibility of counseling education programs’ web sites for students with disabilities. Journal of Technology in Counseling, 2. Retrieved from http://jtc.colstate.edu/vol2_2/flowersbray.htm

Gati, I., & Asulin-Peretz, L. (2011). Internet-based self-help career assessments and interventions: Challenges and implications for evidence-based career counseling. Journal of Career Assessment, 19, 259–273. doi: 10.1177/1069072710395533

Gordon, J., & Berhow, S. (2009). University websites and dialogic features for building relationships with potential students. Public Relations Review, 35, 150–152. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.11.003

Heinlen, K. T., Reynolds-Welfel, E., Richmond, E. N., & Rak, C. F. (2003). The scope of Web Counseling: A survey of services and compliance with NBCC standards for the ethical practice of Web Counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81, 61–69.

Hill, L. N., & White, C. (2000). Public relations practitioners’ perception of the World Wide Web as a communications tool. Public Relations Review, 26, 31-51. doi:10.1016/S0363-8111(00)00029-1

Kent, M. L., & Taylor, M. (1998). Building dialogic relationships through the World Wide Web. Public Relations Review, 24, 321–334. doi:10.1016/S0363-8111(99)80143-X

Kinka, N., & Hessa, T. (2008). Search engines as substitutes for traditional information sources? An investigation of media choice. The Information Society, 24, 18–29. doi: 10.1080/01972240701771630

Kittle, B., & Ciba, D. (2001). Using college web sites for student recruitment: A relationship marketing study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 11, 17–37. doi: 10.1300/J050v11n03_02

Maddux, C., & Johnson, D. L. (1997). The World Wide Web: History, cultural context, and a manual for developers of educational information-based web sites. Educational Technology, 37, 5–12.

Maddux, C. D., Torres-Rivera, E., Smaby, M., & Cummings, R. (2005). Revisiting style and design elements of World Wide Web Pages dealing with multicultural counseling. Journal of Technology in Counseling, 14. Retrieved from http://jtc.colstate.edu/Vol4_1/Maddux/Maddux.htm

Mallen, M. J., Vogel, D. L., & Rochlen, A. B. (2005). The practical aspects of online counseling: Ethics, training, technology, and competency. The Counseling Psychologist, 33, 776–818. doi: 10.1177/0011000005278625

McGlothlin, J. M., West, J. D., Osborn, C. J., & Musson, J. L. (2008). A review of counselor education program websites: Recommendations for marketing counselor education programs. Journal of Technology in Counseling, 5. Retrieved from http://jtc.columbusstate.edu/Vol5_1/McGlothlin2.htm

Middleton, I., McConnell, M., & Davidson, G. (1999). Presenting a model for the structure and content of a university World Wide Web site. Journal of Information Science, 25, 219–227.

Miniwatts Marketing Group. (2011). Internet world stats: Usage and population statistics. Retrieved from http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

Nelson, J. A., Nichter, M., & Henriksen, R. (2010). On-line supervision and face-to-face supervision in the counseling internship: An exploratory study of similarities and differences. Retrieved from http://counselingoutfitters.com/ vistas/vistas10/Article_46.pdf

Poock, M. C., & Bishop, A. V. (2006). Characteristics of an effective community college web site. Community College Journal, 30, 687–695.

Poock, M. C., & Lefond, D. (2001). How college-bound prospects perceive university web sites: Findings, implications, and turning browsers into applicants. College and University, 77, 15–21.

Poock, M. & Lefond, D. (2003). Characteristics of effective graduate school Web sites: Implications for the recruitment of graduate students. College & University Journal, 78, 15–19.

Quartoa, C. J. (2011). Influencing college students’ perceptions of videocounseling. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 25, 311–325. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2011.605694

Quinn, A. C., Hohenshil, T., & Fortune, J. (2002). Utilization of technology in CACREP approved counselor education programs. Journal of Technology in Counseling, 2, Retrieved from http://jtc.columbusstate.edu/vol2_2/quinn/quinn.htm

Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J., Baker, J. D., Neukrug, E., & Hanes, J. (2010). The efficacy of computer mediated communication technologies to augment and to support effective online counselor education. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 28, 161–177.

Sampson, J. P., Jr. (1999). Integrating Internet-based distance guidance with services provided in career center. The Career Development Quarterly, 47, 243–254.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Kolodinsky, R. W., & Greeno, B. P. (1997). Counseling on the information highway: Future possibilities and potential problems. Journal of Counseling and Development, 75, 203–212.

Tapscott, D., & Williams, A. D. (2008). Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything. New York: Portfolio.

Torres-Rivera, E., Maddux, C. D., & Phan, L. (1999). An evaluation of style and design elements of counseling World Wide Web sites. Journal of Technology in Counseling, 1. Retrieved from http://jtc.columbusstate.edu/vol_1/multicultural.htm

Vilnai-Yavetz, I. & Tiffere, S. (2009). Images in academic Web pages as marketing tools: Meeting the challenge of service intangibility. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 8, 148–164. doi: 10.1080/15332660902876893

Yuh-Jen Guo, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Texas at El Paso. Shu-Ching Wang works at the Ysleta Independent School District, El Paso, Texas. Shelly R. Statz is a social worker at the University of Wisconsin Family Medicine Residency program. Craig Wynne is a doctoral student at the University of Texas at El Paso. The authors thank Drs. Rick Myer and Sarah Peterson at UTEP for their assistance in manuscript preparation. Correspondence can be addressed to Yuh-Jen Guo, University of Texas at El Paso, 705 Education Building, College of Education, 500 West University Avenue, El Paso, TX 79968, ymguo@utep.edu.

Oct 6, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 4

Kristi A. Lee, John A. Dewell, Courtney M. Holmes

The persistent research-to-practice gap poses a problem for counselor education. The gap may be caused by conflicts between the humanistic values that guide much of counseling and the values that guide research training. In this article, the authors address historical concerns regarding research training for students and the conducting of research by faculty, and report on an effective research education model animated with values that guide clinical, supervisory and pedagogical identities within counselor education.

Keywords: research-to-practice gap, research training, counselor education, research education, master’s-doctoral collaborative research group

Research is a fundamental part of counseling and counselor education (Huber & Savage, 2009). The structure of the scientist-practitioner model embraced by counseling and other social science fields endeavors to create a useful dialogue between research producers and research consumers that leads to effective evidence-based practice (Lambie & Vaccaro, 2011). Unfortunately, there is evidence to suggest that this dialogue is not actually occurring (Murray, 2009). The breakdown in productive dialogue has roots both in the types of research being produced and in practitioners’ ability to utilize published research (Bangert & Baumberger, 2005; Murray, 2009). This disconnect has resulted in rising concern about the utility and efficacy of research conducted within counselor education for those in practice. Termed the research-to-practice gap, it is a conspicuous problem for the field of counseling at a time when demand for a research-informed evidence base to guide clinical practice is increasing (Moran, 2011).

Furthermore, research in counseling seems disconnected from the essential values that have guided the field (Sperry, 2009). This may be due to a fundamental divide between the values that shape counseling and those that shape research. Mariage, Paxton-Buursma, and Bouck (2004) have suggested that using values as a lens to approach research and practice will serve to “animate” (p. 534) these processes in new ways. Animating both the content and the process of research with counseling values may produce results that are more meaningful to both counselor educators and counseling practitioners. Ideally, the result will be coherent and systemic research designed to solve today’s complex problems.

The research-to-practice gap is acknowledged as a problem throughout the helping professions (Vanderlinde & van Braak, 2010). In counselor education, the gap appears to be amplified by the tenuous nature of the relationship that both practitioners and academics have with research. For practitioners, research is often seen as irrelevant to day-to-day practice and incapable of addressing the complexities of real-world work (Murray, 2009). This perspective is reflected in the conclusion of a methodological review of research articles published in the Journal of Counseling & Development (JCD) between 1990 and 2001, which states that “many ACA [American Counseling Association] members will most likely find it difficult to comprehend and evaluate the usefulness of much of the research published by JCD” (Bangert & Baumberger, 2005, p. 486). Murray (2009) has concluded that most practitioners view research and practice as two entirely unrelated arenas.

For counselor educators, the relationship with research also appears tenuous. Faculty members are charged with two primary tasks relating to research: (1) training practitioners who are capable of utilizing research, and (2) contributing to the counseling knowledge base through publishing original research. The effectiveness and productivity of counselor educators with both of these tasks is in question. A recent study highlighted that faculty do not appear to consistently demonstrate productive engagement with their own research. From 2004–2009, almost 50% (47.9%) of faculty in programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) published two or fewer articles in refereed journals, and almost 20% (18.5%) published none (Lambie, Ascher, Sivo, & Hays, 2014). The relationship that both counseling practitioners and counselor educators have with research appears to be unproductive. Given the current climate of increasing need for mental health care and dwindling resources, the research-to-practice gap must be addressed. A critical examination of the way research is woven into both the professional identity of counselor educators and counselors as well as the counselor-training environment is warranted.

Research and Academia

Research in counselor education is often conducted within academia where, historically, the dominant discourse values positivistic ways of knowing and prioritizes measurable academic products (McLeod & Machin, 1998; Moran, 2011). Central to this discourse is the perspective that value-neutral researchers can acquire knowledge through reducing complex human experiences to isolated variables that are discrete and measurable. Additionally, the last several decades have seen an intentional shift in academia away from emphasizing quality teaching and research toward basing tenure and promotion on the quantity of refereed articles published (Lambie et al., 2014). This shift is undergirded by administrators’ view that measurable academic products are necessary to enhance the field’s reputation, and as a result, the “publish or perish” mentality has become commonplace (McGrail, Rickard, & Jones, 2006). Working within this framework appears to position many counselor educators’ research selves in direct conflict with the values that have historically supported counseling, supervisory and pedagogical orientations.

Research and Counselor Educator Identity

The field of counseling has historically been a practitioner-oriented field focusing on “individuality and human potential” instead of reducing “clients to pathological entities” (Hansen, 2005, p. 406). As a result, training programs are primarily concerned with preparing counselors for practical work. In contrast, other fields stress positivistic research that relies upon reductionist discourses, controlled conditions and ways of knowing that are removed from the complexity of life (Mariage, Paxton-Buursma, & Bouck, 2004). This positivistic perspective is often seen as limited in its practical utility and often inherently alienates those in practice (Vanderlinde & van Braak, 2010). Indeed, according to Murray (2009), many practicing counselors view research in counseling and the practice of counseling as separate and unrelated areas. As counselors, counselor educators are likely to struggle with integrating their rich and complex clinical experiences with a way of knowing that prioritizes positivistic and reductionist discourses.

Working within a positivistic framework can pose problems for counselor educators serving as supervisors. For clinical supervisors, responding to the needs of those in practice and facilitating student counselor development are of central importance. Counselor educators and supervisors are called to help students learn evidence-based best practices detailed in research publications (Wester, 2007). However, according to Bangert and Baumberger (2005), research that increasingly values complex methodologies and statistical analyses is not likely to be easily understood by those in practice, thus rendering a majority of research largely unusable to practitioners. Counselor educators who supervise may find it difficult to reconcile how their research, which is required for tenure, does not appear to meet the needs of practicing counselors and students they supervise.

A positivistic framework also can conflict with counselor educators’ pedagogical perspectives. This is particularly true for those who emphasize social justice, advocacy or multicultural approaches, as positivistic approaches tend to create and reinforce a rigid hierarchy between those who produce knowledge and those who consume it. For example, conducting or relating research that an educator knows might be incomprehensible to practitioners could be seen as an endorsement of practitioners’ role as passive consumers of knowledge. This construction of producers and consumers of research may promote traditional models that fail to consider “broader social contexts, particularly where social injustices occur” (Brubaker, Puig, Reese, & Young, 2010, p. 89). Because the explicit aim of the counseling field is to incorporate pedagogies that reflect social justice and multicultural perspectives (CACREP, 2009), counselor educators may find their pedagogies and research expectations in conflict. This conflict has important implications for the research-to-practice gap, as it reifies rigid roles of knowledge producers and knowledge consumers, and impedes the dialogic process needed to successfully translate valuable research from academia to practitioners’ work in the field.

The conflict between the research environment and the values and identity of counselor educators seems to be a substantial barrier to improving the field’s engagement with research. With this in mind, the extreme variability in the quantity and quality of research being produced makes sense (Lambie et al., 2014; Paradise & Dufrene, 2010). In fact, the current research-training environment may force counselor educators to choose between a research identity and client/student-focused identity. Those attempting to fully embrace both identities may experience Bateson’s classic double bind situation that leads to untenable and fragmented identities (Bateson, Jackson, Haley, & Weakland, 1956).

The Research-to-Practice Gap and Counselor Training

For many practitioners, the only engagement they have with statistics or research design occurs in mandated courses taken during graduate training. While the courses are required to cover basic research education (CACREP, 2009), time and practical limitations make it unlikely that students will emerge prepared to effectively utilize published research (Bangert & Baumberger, 2005). This situation all but ensures that students will enter the field unable to engage in a productive dialogue with researchers or produce their own research, a disconcerting fact for those concerned by the lack of evidence-based practice in the field.

Research and statistics courses also generally occupy an inconspicuous role within counselor education programs. If these topics are taught by noncounseling faculty, it may implicitly communicate to students that research and statistics are not within the scope of the counselor identity. At best, students learn to engage with research in a language that is separate from their emerging clinical selves. More often they find the language of research incomprehensible to their clinical selves. In either situation, students’ counselor identities have a gap between research and practice at their inception (Reisetter et al., 2004).

Counselor educators may feel unprepared to teach classes in research and statistics, which may be due to the education they received in graduate school. The method by which doctoral students prepare to become counselor educators appears to contribute to the research-to-practice gap. Unlike master’s-level students, many doctoral students engage with faculty on research, hopefully benefitting from a productive mentoring relationship that is crucial for future scholarly productivity (Paradise & Dufrene, 2010). Unfortunately, emphasis is seldom placed on training doctoral students to supervise research. The research-training environment equates knowledge and skill in research with the ability to supervise others to conduct effective research. This process is akin to training students as clinicians and assuming that they are prepared to provide clinical supervision for others. Wester and Borders (2011) state that “the counseling profession has competencies for many other aspects of counseling” (p. 1), including supervision, but lacks these for research. Having a skill set in counseling practice does not automatically qualify one to supervise others in practice; this also is true for research and research supervision. This failure to prepare doctoral students in the skills of supervising research is an unfortunate missed educational opportunity that contributes to the maintenance of the research-to-practice gap.

With the limited content, knowledge and skills and fragmented identities in counselor training programs, the research-to-practice gap appears to naturally emerge from the research-training environment. Within this environment, a best-case scenario is for individual researchers to develop sufficient skills to produce high-quality research and hope that this research will trickle down to those in practice. Unfortunately, even in this best-case scenario there is reason to assume that the research-to-practice gap will persist. The field of counselor education has been called upon to improve the quality and quantity of published research, particularly research that practitioners can easily utilize (Murray, 2009). We, the authors, suggest that animating the research process with counseling-related values may serve to reduce the gap between research and practice.

Addressing the Research-to-Practice Gap

The literature has attempted to address the research-to-practice gap in several ways. Suggested interventions have focused on both practical means of addressing the gap and ways to shift the epistemological foundations of research in counselor education. Both of these directions seek to reduce the gap and unify research and practice professional identities. One notable practical suggestion in the literature involves increasing practitioner collaboration in research (Horsfall, Cleary, & Hunt, 2011). Building partnerships with community stakeholders has been identified as the most effective way to ensure that research is relevant and timely for counseling practitioners (Becker, Stice, Shaw, & Woda, 2009). Engaging stakeholders involves fostering relationships and useful dialogues between those in academia and those in practice, thus challenging the current construction of the relationship that limits the role of practitioners to passive consumers of research conducted by those in academia. In order to develop these relationships, counselor educators have been challenged to engage in a collaborative research process that builds relationships, addresses the felt needs of those in practice and disseminates research in a manner translatable to those in practice (Murray, 2009).

Solutions that build upon the strengths of the counseling field in developing relationships and working collaboratively toward felt needs are congruent with the values that undergird the roles of clinician, supervisor and educator. Unfortunately, such solutions also require a significant investment of time and energy on the part of the researcher—a notable problem in the publish or perish world. These practical suggestions also do not address the continued development of both researchers and practitioners who lack a congruent professional identity.

In addition to practical suggestions, the literature has proposed a shift toward post-positivistic epistemologies. Levers et al. (2008) suggested that qualitative inquiries are of particular utility for the counseling field, as they allow researchers to engage about lived experiences and do not unnecessarily reduce complex human experience to unrecognizable parts. Post-positivistic approaches have been suggested to be more consistent with the values of the counseling field and, as a result, more easily digestible by those in practice (Moran, 2011; Rennie, 1994).

While post-positivistic paradigms may provide an engagement in research that is more congruent with counseling identity and values, quantitative data is still more highly valued and expected by many universities. Counselor training does not always emphasize training in qualitative methods, making consistent production of quality qualitative research difficult for academics and practitioners alike. The utility of qualitative methodologies may therefore be limited in much the same way as quantitative research is limited. Without research as a congruent part of the professional identities of both practitioners and counselor educators, the research-to-practice gap will continue.

One potential remedy for cultivating this post-positivistic identity is to provide students with opportunities to engage in practical research experiences and to pursue their own research interests while in counseling training (Murray, 2009). Practical engagement in research can help students to develop and integrate research as one strand of the overall professional counselor identity (Sexton, 2000). This will prime a relationship in which students graduate ready to benefit from creating and collaborating on research.

Changing the counseling field’s engagement with research is necessary if the field is to reduce the research-to-practice gap. Currently, counselor education’s relationship with research appears to be unsettled, leaving the field with a fractured identity. This fractured identity is evident both in the lingering research-to-practice gap and in the way counselors engage with research in training programs. The field of counselor education must find a way to engage both academics and practitioners in research in a way that provides a unified and credible professional identity. The authors suggest that counselor educators need not look far for the solution to this problem. The field must act on counseling values, embrace research as an important component of counselor identity and create a coherent narrative around research. Animating research in counselor education with counseling values is warranted (Mariage et al., 2004). We, the authors, carried out a model that sought to create a new and effective method for engaging in research within counseling and counselor education. Known as the Master’s–Doctoral Collaborative Research Group (MDCRG), this model may offer one avenue for changing the field’s engagement with research.

Overview of the MDCRG

For many students, the current graduate research–training environment does not provide a sufficient structure to develop the skills and identity necessary for a productive engagement with research. This is particularly unfortunate, as the experience of these authors has shown that master’s-level students are eager for opportunities to develop their research skills and to pursue topics of interest to them. This eagerness communicates an unmet need in counselor training; however, there appear to be few opportunities for master’s-level students to participate in research in meaningful ways and develop this core component of their professional identity (Owenz & Hall, 2011). By providing a structured experience animated with the values of the counseling field, counselor educators can actively change the current paradigm of research training.

Animating Research with Counseling Values

The research process may be expanded and enhanced through the infusion of values that guide clinical, pedagogical and supervisory practices. The authors suggest that training future practitioners in a research model that is congruent with counselor professional identity may allow for increased research engagement. Developing new approaches and ideas about effective research training is necessary. While many foundational values undergird counselor education (Eaves, Erford, & Fallon, 2010; Gladding, 2013; Hackney & Cormier, 2013), four are particularly relevant for a research context. These values include the power of relationships (Sheperis & Ellis, 2010), empowerment (Eaves et al., 2010), a developmental perspective (Gladding, 2013; Hackney & Cormier, 2013), and experiential education (CACREP, 2009).

The power of relationships. The establishment of a collaborative, supportive relationship between participants is central to the success of counseling and counselor supervision (Blocher, 1983; Sheperis & Ellis, 2010). Green and Herget stated that the quality of the therapeutic alliance is one of the “most powerful predictors of client outcome” (as cited in Seligman & Reichenberg, 2010, p. 9) in counseling. Additionally, characteristics of the supervisory relationship, such as support and encouragement, contribute to the success of clinical supervision (Leddick & Dye, 1987). Research is often conducted in the isolated academic world and disseminated to a small group. This traditional construction ignores the power of relationships in creating successful outcomes and connections in the research process. Infusing relationships into the processes of research and research supervision is a central goal of the MDCRG.

Empowerment. Eaves et al. (2010) identified empowerment as a central element of counseling philosophy, stating that the goal of promoting empowerment is to help clients “gain the confidence to navigate their future lives and problems” (p. 7). Empowering future counselors with the skills and abilities to address challenges in the practice of counseling is also critical. Congruent with this value, master’s-level student researchers can be empowered to find their research voices through full collaboration in each step of the research process. Students present different needs and desires for engaging in the experience. For example, some want to develop a deeper understanding of the research process, some want to explore specific topics through research, and others want to reduce perceived gaps in the knowledge base. In the MDCRG, the doctoral-level supervisors provide a space where group members can share their research needs and advocate for their ideas. The group collectively determines research topics, direction and products, with each member having an equal voice in the process. This structure seeks to empower students and strengthen student research identity and professional voices.

Developmental perspective. The use of developmental theory to conceptualize and promote growth has undergirded the field of counseling for many years (Gladding, 2013), and it has been heavily utilized to frame clinical supervision (Blocher, 1983). Broadly speaking, the developmental perspective rests on the assumption that the correct balance of support and challenge promotes individual growth. While the use of developmental theory in research supervision has not yet been documented in the current counseling literature, it is a useful model in the research context as well. Taking a developmental pedagogical stance throughout the process, MDCRG doctoral research supervisors utilize the skills of teaching, supporting and challenging students to promote growth in their research abilities. In order to accomplish this, research supervisors adjust the amount of environmental support and structure as group members develop their ability to engage in the research process.

Experiential education. Counselor training has historically utilized active, experiential pedagogical strategies (Hackney & Cormier, 2013). A central component of counselor education is the clinical field work that occurs during counseling practicum and internship experiences (CACREP, 2009). Employing a similar model of experiential education, the MDCRG is designed to offer both master’s and doctoral students opportunities to engage in a practical experience of conducting research and research supervision. Master’s-level researchers actively participate in each step of the research process, including generating research topics, conducting literature reviews, formulating research designs, collecting and analyzing data, and writing for publication. Further, doctoral students gain practical experience in supervising and supporting others’ research. This type of practical engagement has been suggested as a way to reduce the research-to-practice gap (Murray, 2009). Utilizing experiential pedagogical strategies in research training will create a unified approach across different components of counselor education.

The counseling values of relationship, empowerment, developmental perspective and experiential education animate the research process in the MDCRG. The resulting model provides a possible new avenue for more effective research training in counselor education. The context, structure, stages and outcomes of this model are described and discussed in the following section.

Context for the MDCRG

The MDCRG was conceptualized and put into place when the first author, a third-year doctoral candidate at the time, was approached independently by several master’s students expressing a desire to become involved in research. These students expressed interest in actively engaging in the research process in order to explore areas of interest in clinical practice. They were satisfied neither with the level of research training they had received in their graduate program, nor with the role of consumer of research that was implied in the research training.

The counselor education program that housed the MDCRG consisted of a CACREP-accredited master’s program in Community Counseling and School Counseling, and a CACREP-accredited doctoral program in Counselor Education and Supervision. Each program traditionally required 2 and 3 years, respectively, to complete. Within the counselor education program there was little precedence for the collaboration of faculty with master’s students on research, as doctoral students often filled these roles. Given the desire of these energetic and motivated master’s students to experience the research process firsthand, this situation constituted an unfortunate gap in the counselor training experience. Graduating without meaningful engagement in research would likely result in a continuation of the research-to-practice gap for these students.

Overall Structure of the Group

Membership in each MDCRG included three types of roles: (1) doctoral student research supervisors, (2) a faculty advisor and (3) master’s-level researchers. A third-year doctoral student served as the lead research supervisor and a second-year doctoral student partnered to supervise the group. This tiered leadership configuration created a developmental structure that prepared the less-advanced doctoral student with the skills needed to lead the next iteration of the MDCRG. Doctoral research supervisors recruited first- and second-year master’s students via e-mail, and received support from a faculty advisor. In this developmental structure, second-year master’s students mentored first-year students, and first-year students prepared to take on mentoring roles in the following academic year. Thus, the group was designed to be developmental and cyclical, so that over time all students continually advanced to greater levels of responsibility and skill. The MDCRG was an ongoing experience within the counselor education program, with each group working together for the duration of an academic year. The groups progressed through four stages, as described in the following section (summarized in Table 1).

Stage 1: Forming the group. The initial step in forming the MDCRG is the establishment of the leadership structure and support from program faculty. Once the research supervision leadership is established (two doctoral research supervisors and a faculty advisor), recruitment for master’s-level researchers begins. All current master’s students receive an e-mail describing the MDCRG as a fully collaborative and hands-on research experience and inviting the students to attend an information meeting. Potential participants learn that expectations for participation include attendance at weekly research meetings, as well as active contribution to research tasks including collection and analysis of data, writing and presenting. Groups typically have approximately nine members, including two doctoral research supervisors, a faculty advisor and six master’s-level researchers.

Once the membership in the group is established, the group begins its work. Consistent with a developmental model of supervision (Hunt, Butler, Noy, & Rosser, 1978), throughout stage 1, supervisors adopt an active role and provide high levels of structure and support. Initial sessions focus on establishing the structure for weekly meetings, identifying goals and forming working relationships among the group. Master’s-level researchers are encouraged to engage in the formation and direction of the group. In order to empower the master’s-level researchers, the research supervisors facilitate conversations that focus on what each member of the group wants to achieve and experience.

Research supervisors seek to model open communication by providing an atmosphere in which the group can productively discuss potential pitfalls in collaborative research. For example, in a group that the authors conducted, the group members examined the challenge of establishing order of authorship on presentations or publications when working in a group. The research supervisors shared personal experiences of how this can arise as an issue and presented various options for deciding authorship. Together the group conferred and selected a method for resolving this situation.

Stage 2: Research preparation. In this stage, groups select research topics, apply for IRB approval (if necessary), write research grants and submit conference presentation proposals. Again, in order to empower master’s-level researchers, all members of the group are invited to present topics of interest to the group for consideration. Research supervisors teach relevant research skills as needed, including how to turn a topic of interest into a researchable project with specific research questions and methodologies. The group discusses all potential research topics that members bring as possibilities. As a group, they select research topics, develop research questions and choose methodologies for conducting the research.

Once they have identified a specific project, group members elect to engage in various scholarly activities, including submitting research grant proposals and conference presentation proposals. For example, in the model the authors carried out, one group chose to research how CACREP-accredited programs engaged in program evaluations and used those evaluations to improve programs, while another group pursued its interest in training gaps in preparing students to work with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) clients. As needed, research supervisors teach master’s-level researchers about preparing grant and conference proposals. All group members are responsible for drafting portions of proposals. Finally, all of the group members edit compiled proposals and then submit them for consideration.

Stage 3: Active research. All members are fully engaged during this stage, in which data are collected and analyzed. Research supervisors coach master’s-level researchers on appropriate data collection procedures. Each member is responsible for segments of the data collection and analysis. When problems arise, group members work together to brainstorm solutions. At various points, members take the lead on pieces of the research process. For example, in one group, a master’s researcher who was particularly skilled in spreadsheet software created the spreadsheet used in data tracking and analysis. At times, members are not able to attend weekly meetings in person because of illness or travel, but attend these meetings remotely using technology such as instant messaging or video chatting. Throughout the process, doctoral supervisors take the opportunity to teach research concepts, processes or procedures as needed.

During this stage, groups prepare conference presentations that disseminate their research. Because most of the master’s researchers have never presented at a professional conference, doctoral supervisors share experiences of past conference presentations to order to teach master’s-level researchers how to put on a professional, well-prepared and engaging conference presentation. The researchers identify important pieces of preliminary results and decide how to structure the presentations. Each member is responsible for preparing and presenting pieces of the research during the presentation. In the group meetings before the conference, group members practice their presentation together. Presentations at professional conferences are often peak moments for the groups.

Stage 4: Writing and closure. As data collection and analysis end, groups prepare to disseminate the results of their research through writing. Again, doctoral supervisors teach master’s-level researchers the skills and process of scholarly writing. All members are responsible for drafting pieces of manuscripts. The group members discuss and edit drafts on a weekly basis. Once the groups have concluded their work, doctoral supervisors finalize manuscripts to unify the voices of various authors, and then submit them for review with appropriate publishing venues.

The close of the academic year also brings the end of the research group experience. Consistent with clinical values, the doctoral supervisors believe that an important element of any group is to reflect on the experience to provide opportunities for celebration and closure. At the conclusion of the experience, research supervisors facilitate group reflection, encouraging master’s-level researchers to consider and share what they learned about themselves, about research and about their roles as counselors. Closing celebratory dinners are held as final group sessions.

Table 1

MDCRG Timeline and Tasks by Stage

| Stage |

Timeline |

Tasks |

|

|

|

| 1: Forming |

September |

Select group leadership |

| Recruit master’s-level researchers |

| Set up group structure |

| 2: Research Preparation |

October–November |

Select research topic |

| Apply for Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval |

| Apply for research grants |

| Apply for conference presentations |

| 3: Active Research |

December–March |

Collect data |

| Analyze data |

| Conference presentation |

| 4: Writing and Closure |

April–May |

Manuscript preparation |

| Reflection |

| Celebration and closure |

Outcome and Evaluation

Each iteration of the MDCRG has been successful in both content and process. The groups produced scholarly work including the following: one published article in a professional, refereed journal; a CACREP-funded student research grant; three professional presentation sessions at a state-level counseling conference; implementation of a training program on working with LGBT clients in a multicultural course; a professional presentation at a regional counseling conference; and two articles published in a regional counseling newsletter. These accomplishments have exceeded the expectations of all involved. In addition, of the master’s-level researchers involved during the first 2 years, two researchers have now completed doctoral degrees in Counselor Education and Supervision, others are currently in doctoral programs, and others have advanced to clinical practice. All of the doctoral-level supervisors are now working as counselor educators in CACREP-accredited programs.

Beyond the scholarly accomplishments that the groups achieved, master’s-level researchers gained new skills, knowledge and perspectives about research. After two iterations of the group, doctoral research supervisors conducted an informal survey with which to assess the learning outcomes of the MDCRG experience for master’s-level researchers. Participants were asked to respond in writing to prompts on their experiences within the group. Questions included but were not limited to the following: (1) What was the experience of being in the MDCRG like for you?; (2) What were the most important things you learned about the research process while you were in the group?; and (3) Did your participation in the group change how you see your role as a counselor?

Responding to the informal survey of their experiences in the MDCRG, several master’s-level researchers reflected on how the group influenced their practical knowledge of research. They reported learning about the importance of maintaining focus on the research questions, the importance of persistence in finding peer-reviewed and current articles, and the importance of using a timeline to keep the research on track. One master’s-level researcher reflected, “I feel I have the necessary tools in order to research articles, write an article that is tailored to the journal/newsletter, and submit it to a newsletter and conference.”

One of the most valuable experiences that the master’s-level researchers reported was engaging in a collaborative research process with peers. Researchers stated that they learned “the value of one’s colleagues in the research process,” the value of “decision making as a group” and the value of “being able to collaboratively decide on a topic,” such as how to divide the work and how to decide authorship.

Master’s-level researchers also reported that participation in the MDCRG positively affected their academic program. They reported translating their learning from the MDCRG into academic classes. One student stated, “I bring the knowledge I gained to the classroom.” Another said that the group “enriched my academics,” while others expressed that it “highlighted the lack of research done at the master’s level in this program.” Having an opportunity to explore their own interests in the research process led several master’s-level researchers to take a more active role in their coursework. Additionally, the group gave researchers the opportunity to develop collaborative relationships with other students that they “otherwise would not have had.” Students reported benefitting from the cross-cohort connections and mentoring.

Master’s-level researchers also stated that they could clearly see a link between their experiences within the MDCRG and their counseling practice. One master’s-level researcher reflected that “the subject matter of the research enhanced my ability to be a more culturally competent counselor for LGBTQ individuals and made me a resource for colleagues that were not in the research group.” Another student stated that the group “solidified the importance of research in responsible, current practice.” A third stated that her experience highlighted the need for additional research and advocacy.

The final theme that the students mentioned when responding to the informal survey is encouraging in light of the research-to-practice gap. Participant responses reflected a deeper understanding of and appreciation for the role of research in counseling. One student said that “[my] understanding of the importance of conducting research motivates me to be involved and . . . engage in the research already being conducted at my agency of employment.” Other students suggested that their greatest growth came in understanding “how to communicate ideas and also how my ideas can be strengthened/further developed through collaboration.” The research-to-practice gap may be reduced through producing students who emerge from training programs viewing research as part of their professional identity.

Implications and Conclusion

The research-to-practice gap has been a persistent problem in counselor education that may be attributed to incongruence between how the research process has historically been constructed and the values central to counseling. This gap is reflected in the low rates of publication by counselor educators and in graduating counselors’ lack of readiness to engage in research (Bangert & Baumberger, 2005; Lambie et al., 2014). The call for evidence-based practices will likely continue to increase and will result in greater demand for all types of research. For the field of counseling to grow and stay relevant in an era of increasing need and decreasing resources, a change in research training and practice will be necessary. Meaningful change necessitates a cultural shift that animates the research process with the values that guide clinical, supervisory and pedagogical perspectives. This type of change would facilitate a more productive and effective relationship between counseling practitioners, counselor educators and researchers. In order to reduce the research-to-practice gap, counselors must emerge from graduate programs prepared to utilize and to produce high-quality, relevant research. Until the counseling field engages in the research process in a way that is consistent with practitioners’ values, the field’s interactions with research will continue to be limited to a small handful of individuals, and the research-to-practice gap that inherently limits the potentiality of both practitioners and academics will continue. Counselor educators are uniquely suited to lead this charge and promote a congruent sense of professional identity that includes research. As a field, counseling can be a model for how the social sciences prepare themselves for the continued push toward evidence-based practice.

Research is a fixture of academic life. Counselor educators, in collaboration with counseling students and practitioners, could embark on new lines of inquiry that seek to better understand the relationship between research and the field of counseling. Several areas for future research are suggested. First, studies are needed that examine meaningful and productive ways to teach master’s students how to engage with research. Second, models for research collaboration between researchers and practitioners should be studied and implemented. Third, understanding how practicing counselors utilize or do not utilize published research could inform a change in pedagogical practices. Finally, conducting empirical research on the model presented in this article would offer deeper understanding of the impact of the model on students as future practitioners.

The model outlined above offers a possible avenue for providing effective research training for counseling students, for creating a congruent identity as a field and for reducing the research-to-practice gap. The lived experience of using this model illustrates that it offers a realistic and sustainable approach for research training in counselor education. It shows that students are eager to change their relationship with research, and that by responding with professional values, counselors can make a meaningful difference in the research-to-practice gap.

References

Bangert, A. W., & Baumberger, J. P. (2005). Research and statistical techniques used in the Journal of Counseling & Development: 1990–2001. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 480–487. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00369.x

Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J., & Weakland, J. (1956). Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, 1, 251–264. doi:10.1002/bs.3830010402

Becker, C. B., Stice, E., Shaw, H., & Woda, S. (2009). Use of empirically supported interventions for psychopathology: Can the participatory approach move us beyond the research-to-practice gap? Behaviour Research & Therapy, 47, 265–274. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.007

Blocher, D. H. (1983). Toward a cognitive developmental approach to counseling supervision. The Counseling Psychologist, 11, 27–34. doi:10.1177/0011000083111006

Brubaker, M. D., Puig, A., Reese, R. F., & Young, J. (2010). Integrating social justice into counseling theories pedagogy: A case example. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 88–102. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00111.x

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). 2009 CACREP standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/2009-Standards.pdf

Eaves, S. H., Erford, B. T., & Fallon, M. (2010). Becoming a professional counselor: Philosophical, historical, and future considerations. In B. T. Erford (Ed.), Orientation to the counseling profession: Advocacy, Ethics, and Essential Professional Foundations (pp. 3–23). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Gladding, S. T. (2013). Counseling: A comprehensive profession (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hackney, H. L, & Cormier, S. (2013). The professional counselor: A process guide to helping (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hansen, J. T. (2005). The devaluation of inner subjective experiences by the counseling profession: A plea to reclaim the essence of the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 406–415. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00362.x

Horsfall, J., Cleary, M., & Hunt, G. E. (2011). Developing partnerships in mental health to bridge the research-practitioner gap. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 47, 6–12. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00265.x

Huber, C. H., & Savage, T. A. (2009). Promoting research as a core value in master’s-level counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48, 167–178. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00072.x

Hunt, D., Butler, L., Noy, J., & Rosser, M. (1978). Assessing conceptual level by the paragraph completion method. Toronto, Canada: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Lambie, G. W., Ascher, D. L., Sivo, S. A., & Hayes, B. G. (2014). Counselor education doctoral program faculty members’ refereed article publications. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92, 338–346. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00161.x

Lambie, G. W., & Vaccaro, N. (2011). Doctoral counselor education students’ levels of research self-efficacy, perceptions of the research training environment, and interest in research. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 243–258. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2011.tb00122.x

Leddick, G. R., & Dye, H. A. (1987). Effective supervision as portrayed by trainee expectations and preferences. Counselor Education and Supervision, 27, 139–154. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.1987.tb00753.x

Levers, L. L., Anderson, R. I., Boone, A. M., Cebula, J. V., Edger, K., Kuhn, L., . . . Sindlinger, J. (2008). Qualitative research in counseling: Applying robust methods and illuminating human context. Retrieved from http://counselingoutfitters.com/vistas/vistas08/Levers.htm

Mariage, T. V., Paxton-Buursma, D. J., & Bouck, E. C. (2004). Interanimation: Repositioning possibilities in educational contexts. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, 534–549. doi:10.1177/00222194040370060901