Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Rebecca Scherer, Regina Moro, Tara Jungersen, Leslie Contos, Thomas A. Field

Initiating and sustaining a counselor education and supervision doctoral program requires navigating institutions of higher education, which are complex systems. Using qualitative analysis, we explored 15 counselor educators’ experiences collaborating with university administrators to gain support for beginning and sustaining counselor education and supervision doctoral programs. Results indicate the need to understand political elements, economical aspects, and the identity of the proposed program. Limitations and areas for future research are presented.

Keywords: counselor education and supervision, doctoral, university administrators, counselor educators, support

The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs’ (CACREP) 2009 CACREP Standards (2008) included a new requirement for core faculty in both entry-level (i.e., master’s) and doctoral programs. This requirement endured in the 2016 CACREP Standards (2015). Although West et al. (1995) predicted the necessity of growth of CACREP-accredited doctoral-level counselor education programs in the mid-1990s, it was not until 2013 that core faculty in all CACREP-accredited programs were required to possess doctorates in counselor education and supervision (CES; or be grandfathered in from previous employment experience; CACREP, 2008). Master’s-level programs that are seeking new CACREP accreditation, as well as existing programs that are seeking to maintain accreditation, must therefore hire faculty with doctorates in CES. This requirement has created a need for greater numbers of doctoral graduates in counselor education, and institutions with master’s-level programs may be seeking to establish new doctoral-level programs to meet this need.

The creation of a doctoral program requires intricate navigation of complex systems of administration, accreditation, funding, laws, facilities, infrastructure, and politics. Additionally, universities have different requirements and levels of approval for new program development (S. Fernandez, personal communication, November 27, 2017). Counselor educators proposing a CES doctoral program must have an understanding of the complexity of the specific university (e.g., its organization, the history of university support for doctoral programs, the mission of the institution, the needs of the surrounding community, and the resources required for program development and implementation). Furthermore, counselor educators must have a firm grasp of accreditation standards for both the university’s regional accreditation bodies (e.g., Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools), as well as specialty CES accreditation through CACREP.

Structure of Universities

The hierarchical structure of universities varies from institution to institution. In this section, we provide a general outline of how universities are structured to help counselor educators who are interested in proposing a CES doctoral program. This information is very important when considering how to advocate for a doctoral program because of the many organizational layers and levels associated with an institution.

Typically, counseling programs are housed in a department, college, or school of the university (e.g., College of Education). The program is led by a program head, coordinator, or department chair. This person reports to the dean of the college. The dean reports to the provost or chancellor or chief executive officer. The president of the university then supersedes this level.

It is important for faculty members to assess the priorities of their institution for academic, student, and financial affairs. For example, a small private college in an urban area may have a mission to train adult learners and to provide access to education through lower admissions standards and flexible pathways to degree completion. In contrast, a large, public, research-intensive university may have a mission to support exceptional research and secure external grant contracts, and to raise college rankings through metrics such as low acceptance rates (The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, 2019). Based on administrative experience with doctoral program creation, structural information must be taken into consideration when advocating to administrators on behalf of CES doctoral program development.

Successful Initiation of Doctoral Programs

In the higher education literature, there are a few publications on the creation of doctoral programs. Researchers have proposed that doctoral programs can be successfully initiated in the context of three circumstances: (a) top-down initiation, (b) filling a need in the local area, or (c) focusing on new delivery methods (Brooks et al., 2002; Haas et al., 2011; Slater & Martinez, 2000). In regard to top-down initiation, some authors have proposed that doctoral programs are likely to be launched if the initial idea comes from the provost or president of the university. Slater and Martinez (2000) described the process of successful initiation of a doctoral program in a small institution in Texas. They reported that the president suggested the idea to the dean, with later onboarding of faculty members.

Doctoral programs also seem to be initiated successfully if a need exists for such a program in the local area (Brooks et al., 2002; Haas et al., 2011). Haas and colleagues (2011) emphasized the importance of faculty members and administrators assessing program fit within the region. In both the Brooks et al. (2002) and Haas et al. (2011) studies, the importance of current delivery modalities in successfully recruiting support for a doctoral program, including the use of online delivery and interdisciplinary studies, was presented.

Rationale and Purpose

At the time of writing, no studies could be identified in the CES literature regarding how to successfully gain administrative support for starting a doctoral program in CES. Another manuscript in this special issue (Field et al., 2020) illustrates a potential pipeline problem in counselor education, in particular the need for more CES doctoral programs in the North Atlantic and Western regions of the country. CES faculty members who are contemplating starting a CES doctoral program currently have little guidance on how to gain support for starting a program. In addition, no studies could be located regarding how to successfully sustain an existing doctoral program in CES. The purpose of this study was to collect and analyze qualitative data to address the research question guiding this study: Which strategies are helpful in gaining initial and ongoing support from administrators for a CES doctoral program, and how successful are those?

Method

This study was conducted as part of a larger basic qualitative study sampling counselor educators. The purpose of the larger qualitative study was to identify perceptions of doctoral-level counselor educators regarding four major issues pertinent to doctoral counselor education: (a) components of high-quality programs, (b) strategies to recruit and retain underrepresented students, (c) strategies for successful dissertation advising, and (d) strategies for working with administrators. In order to explore these four major issues, four research teams were assembled, one of which included the authors of this manuscript. All four coding teams worked together to select these four issues, as it was felt that these issues were most pressing for faculty who were seeking to establish new doctoral CES programs and that little information and guidance existed in these areas. In-depth interviews were then conducted with doctoral-level counselor educators in CACREP-accredited programs to answer a series of research questions that addressed the issues above. Faculty from CACREP-accredited programs were selected because the focus of the larger project was to support faculty who intended to seek CACREP accreditation for new doctoral CES programs.

In the basic qualitative tradition, qualitative data were collected, coded, and categorized using the constant comparative method from grounded theory methodology (Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Basic qualitative designs involve the collection and analysis of qualitative data for the purpose of answering research questions outside of other specialized qualitative focus areas (e.g., developing theory, understanding essence of lived experience, describing environmental observations). Because we were not seeking to develop theory, understand lived experience, or research any other specialized qualitative focus area with this study, and because the research question did not require a specialized approach to data analysis, the large research team selected the basic qualitative approach described above.

Each coding team designed interview questions to directly answer their specific research question. The research questions explored in this study were as follows: Which strategies are helpful in gaining initial and ongoing support from administrators when seeking to start a new doctoral program in CES, and how successful are those? The interview questions that were developed and used as the basis for data collection for this study were: 1) What guidance might you provide to faculty who want to start a new doctoral program in counseling, with regard to working with administrators and gaining buy-in? and 2) What guidance might you provide to faculty who want to sustain an existing doctoral program in counseling with regard to working with administrators and gaining ongoing support?

Participants

Participants met two inclusion criteria for entrance into the study: (a) current core faculty members in a doctoral CES program that was (b) accredited by CACREP. Email requests were sent to 85 CACREP-accredited programs; faculty from 34 programs responded (40% response rate). Interviews were conducted with 15 full-time faculty members at CACREP-accredited CES doctoral programs. Participants were each from separate and unique doctoral programs, with no program represented by more than one participant.

The 15 participants were selected one at a time, using a maximal variation sampling procedure to avoid premature saturation (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). The authors used maximal variation to understand perspectives from faculty of diverse backgrounds who worked at different types of institutions. Participant selection was predicated on six criteria grounded in research data about factors that may impact perceptions about doctoral program delivery: (a) racial and ethnic self-identification (Cartwright et al., 2018); (b) gender self-identification (Hill et al., 2005); (c) length of time working in doctoral-level counselor education programs (Lambie et al., 2014; Magnuson et al., 2009); (d) Carnegie classification of university where the participant was currently working using The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education database (Lambie et al., 2014); (e) region of the counselor education program where the participant was currently working (e.g., Field et al., 2020), using the regional classifications commonly applied in the counseling profession; and (f) delivery mode of the counselor education program where the participant was currently working, such as in-person or online (Smith et al., 2015). As an example of this procedure, the first two participants were selected because of variation in gender, years of experience, and Carnegie classification. The third and fourth participants were selected on the basis of differences from prior interviewees with regard to ethnicity and region. Interviews continued until data seemed to reach saturation and redundancy at 15 interviews.

Although unintended, participant characteristics closely approximated CACREP statistics for faculty characteristics. The demographics of counselor educators in the sample was 73.3% White (n = 11), with 73.3% (n = 11) of participants working at research-intensive (i.e., R1 and R2) institutions. The sample was highly experienced, with an average of 19.7 years (SD = 9.0 years) as a counseling faculty member, with a range of 4 to 34 years. More than half of the participants (n = 9) had spent their entire career in doctoral counselor education.

Procedure

The last author of this manuscript sought IRB approval. Once we received IRB approval, potential participants were contacted from 85 CACREP-accredited programs with doctoral-level graduate studies in CES. Fifteen faculty were interviewed based on maximal variation sampling described above. All but one participant (n = 14) was interviewed via the Zoom video conference platform, chosen because of its privacy settings (i.e., end-to-end encryption). Interviews were recorded using the built-in Zoom recording feature. One participant was interviewed in person at a national counseling conference. This interview was recorded using a Sony digital audio recorder.

Interview Protocol

Each videoconference interview was begun by collecting demographics and informed consent. Following the introductory phase, interviewees were asked eight questions that addressed the research questions of the larger study. Two of the questions were specific to this sub-research team. Interview questions were developed using Patton’s (2015) guidelines to inform question development. Specifically, the questions were open-ended, neutral, avoided “why” questioning, and asked one at a time. The questions were piloted with peer counselor educators prior to the start of the research project in order to get feedback on clarity and ease of answering. Participants received the questions by email before their scheduled interview. The participants were identified using alphabetical letters to blind participant identity to all members of the research team.

Each semi-structured interview lasted at least 60 minutes, during which participants responded to questions that were evenly distributed among the four research teams. Participants were therefore able to respond to interview questions with significant depth. Data did not appear saturated until 15 interviews had been conducted. Each research team was asked to review the transcripts developed from the 15 interviews to deduce whether adequate saturation had been achieved and until consensus was reached.

Transcription

All interview recordings were transcribed by graduate students. These students had no familiarity with the interviewees and were trained in how to transcribe verbatim. Once completed, each transcript was sent back to the interviewees to ensure accuracy. After all interviewees checked their document, the sections of the transcripts with the questions related to each team were copied and pasted into a document organized by the participants’ alphabetical identifiers. Each team was responsible for coding and analyzing the responses to their respective questions from the interviews.

Coding and Analysis

The first, second, third, and fourth authors served as coding team members. The fifth author conducted the interviews as part of the larger study and assisted with writing sections of the methodology only. The demographics of the coding team were as follows. Team member ages ranged from mid-30s to 40s. All four identified as White cisgender females. Two of the coding team members were employed as full-time counselor educators, one identified as an administrator and counselor educator, and one coding team member was completing doctoral training as a counselor educator. Two participants had worked in doctoral counselor education programs, and two had not. We have served on both sides of the faculty–administrator relationship. These differences in backgrounds allowed for both etic and emic positioning pertinent to the topic of working with administrators to start and sustain doctoral programs in CES.

Because of the nature of both insider (emic) and outsider (etic) perspectives, the authors used a memo system when coding the manuscripts. This memo system involved three components. First, we created a blank memo every time a transcript was coded. Second, each time an interviewee’s transcribed response provoked some response within one of us, we raised it to the group and reflected on our individual experience. This response was documented in a memo. Third, one of us took notes to bracket any biases that might have been present. Identified biases often stemmed from our own experiences as faculty members talking to administrators, our service in an administrative role, or our own personal experiences developing doctoral programs. This occurred during joint coding team meetings and individual coding meetings once the open coding had been solidified into a set of codes. The memos were kept in a shared, encrypted, electronic folder for later review.

The following steps were followed by the coding team in the current study to ensure trustworthiness of analysis. The four coding team members jointly coded the first three participant transcripts to gain consensus. Following this open coding process, the second author condensed the open codes for the next phase of analysis. The coding team members then reached consensus on the condensed codes. Following agreement, we used the condensed codes to continue the coding process for the next two transcripts in joint coding meetings. This process allowed for discussion to assist with consistent understanding of the codes across the team. Following the joint open coding of the fifth transcript, the remaining 10 transcripts were assigned to one of us for open coding to be completed independently. After the open coding process was completed, the fourth author proposed a framework of the emerging themes. She examined the open codes and considered discussions that emerged throughout the team process to identify the emergent themes from the data. Open codes were only included in the analysis if they emerged in at least four transcripts, which resulted in the removal of three codes from the final results. All team members reached consensus for the themes that were originally identified by the fourth author.

Results

The data analysis process resulted in three emergent themes regarding strategies for gaining initial and ongoing support from administrators for CES doctoral programs and the level of success of those strategies. The three themes were political landscape, economic landscape, and identity landscape. Each theme had five associated subthemes. Each theme and subtheme are discussed in more detail below, and brief participant quotes are inserted to highlight the experiences of the participants in their own words for the purpose of thick description (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Political Landscape

Considering the political landscape appeared to be a crucial strategy for recruiting administrative support when having conversations with administrators about CES doctoral programs. Participants described the importance of understanding the context of conversations with administrators within the larger political system of higher education institutions. The subthemes represented factors that influenced political decisions.

Political Endeavor: “Watching Your Politics”

Participants reported that conversations with administrators were highly political in nature and having these conversations was a form of political endeavor. One example of political endeavor was to ensure that other academic units and programs were in support of a CES doctoral program. As one participant stated, “First make sure that you’ve got your politics in order, so social work agrees with you and psychology agrees with you. So, you’ve got support of any competitor on campus.” If other academic units or programs are opposed to a CES doctoral program, it may result in administrators being cautious about supporting the program because of fears that they may be caught in the middle of a turf battle.

Gaining administrative support seemed to be predicated on the ability to “strategically build relationships” with administrators, as one participant put it. One participant commented on the complexity of developing these relationships with administrators. This participant believed that faculty needed to strike a balance of being flexible and adaptive to the administrators’ agenda and “order of the day,” while also retaining one’s “own ideology and belief systems.” Building relationships with administrators also seemed to involve avoiding unnecessary conflict that may reduce administrator support for faculty ideas. One participant cautioned that “watching your politics” and “keeping your mouth shut when you know you shouldn’t be speaking up against key administrators” was important during conversations with administrators to avoid unnecessary conflict that could “hurt your own doc program.” Learning this form of engagement seemed to be a struggle for some participants. One participant stated that they “don’t know how to navigate those conversations effectively” and felt “saddened and frustrated” as a result.

Status, Prestige, and Recognition: “A Huge Feather in One’s Cap”

Participants conveyed that CES faculty could gain administrative support through the strategy of arguing how a doctoral program could enhance status, prestige, and recognition for an institution. One participant commented that “all university presidents want doctoral programs. They want them because of the prestige.” This participant elaborated that faculty should therefore “show them how doctoral programs bring recognition, how it raises you in the rankings, and all of those kinds of things.” Some participants noted that the degree to which administrators cared about enhanced status, prestige, and recognition depended on the type of institution. For example, administrators who work at an institution that is less concerned with college rankings may be unpersuaded by the potential for enhanced status and recognition.

Participants also encouraged CES faculty to strategically engage in actions that increase recognition for the program and university. Some potential strategies that may appeal to administrators include being “identified as an expert, and to go out and do public radio broadcasts and be featured in the newspaper. Be featured in national publications.” This recognition helps with both program and university visibility, which participants believed was important to administrators. Participants also shared that visibility can help to protect the program from losing administrative support. As one participant stated, “If you’re invisible in the eyes of the administrators, they’re not going to think of you if some opportunities are coming to the fore.” This participant further commented that administrators needed to be reminded of the doctoral program through continual visibility efforts, as administrators often operate from an “out of sight, out of mind” position.

Demonstration: “Wanting Empirical Evidence”

Participants identified the strategy of sharing evidence with administrators to support and sustain doctoral programs. As one participant stated, “Once you get to the doctoral level, then we’re talking about people wanting empirical evidence.” In the early stages of program formation, this evidence might be a comprehensive proposal that is supported by data. As one participant stated, faculty need to develop a “solid plan” and be “as prepared as possible” for conversations in which administrators will “ask a ton of questions.”

Once a program is formed, it seems crucial that programs continuously provide updates to administration about program successes to sustain administrative support. Participants identified several approaches to demonstrating the success of a program. Some participants indicated that it was important to keep administration informed about student successes that occurred during doctoral study. One participant reported that their program kept administration informed via email about “every little success of the doctoral program” and provided the following examples: “Every time somebody successfully defends a dissertation, every time somebody presents at a conference, every time somebody gets a job congratulated, the president knows about it.” Other participants believed that it was helpful to report program outcomes such as graduation rates and employment statistics, which requires faculty to maintain contact with alumni to understand where they are working after graduation. It therefore seems possible that administrators may differ in which types of evidence they value, requiring faculty to carefully consider which information their administration most values when sending them updates of program successes. As one participant stated, “I think the question is, what information do you need to feed to administration to be convincing?”

Scrutiny: “Internal Credibility Is Super Important”

Participants reported that program faculty should understand the different ways that administration will scrutinize the credibility of a doctoral program. One participant defined credibility as, “Do what you’re doing well.” Administrators might withdraw support for a program that is perceived as not producing quality graduates or has problems such as not graduating students. Administrator scrutiny of the program’s financial situation also appears to be an important consideration. Administrators who are concerned about the financial viability of the program may withdraw their support.

Timeline and Trajectory: “It’s a Long Journey”

Participants reported that political decisions, such as starting and sustaining academic programs, particularly doctoral programs, may be influenced by unique timelines and trajectories. Participants encouraged faculty to develop the strategy of thinking long-term about cultivating administrative support for a doctoral program. One participant emphasized the need to “work together” with administrators in a collaborative fashion and make compromises so that administrators will support the doctoral program throughout the “long haul” and “long journey” of the program.

The length of administrator tenure at the university is another factor that faculty are advised to consider. One participant stated that faculty tend to have longer tenure than administrators at their university. As a “lifer,” this participant saw “a lot of rotation in and out of leadership.” Administrator turnover can result in changes to administrative priorities and agendas, which can impact support for a CES doctoral program. This participant encouraged faculty to “be cognizant of the fact that winds change.”

Economic Landscape

Considering the economic landscape and economic realities of starting and sustaining a doctoral program was the second main overarching theme. Developing an understanding of the economic landscape is important context for faculty when preparing for discussions with administrators. Several subthemes comprise the economic landscape, each detailed below.

Financial Aspects: “It Takes a Lot of Money”

Of utmost importance when discussing starting and sustaining CES doctoral programs with administrators is understanding the financial resources required. Many participants spoke about the cost of CES doctoral programs for universities. Participants believed that a crucial strategy to gaining administrator support was being able to explain how programs can be at least revenue-neutral or even generate revenue for the university, as administrators are less likely to support a CES doctoral program that is a drain on financial resources.

Participants varied in their perceptions of whether CES doctoral programs could generate revenue for the university. The key distinction between these participants seemed to be whether they believed doctoral programs should charge students tuition or fully fund them. Some participants believed that “high-quality doc programs do not make money for institutions” because they should be fully funding doctoral students rather than generating tuition revenue. These participants proposed that faculty should instead be “thinking creatively about funding sources” and seeking alternative methods of offsetting the financial burden on the institution. Examples of identified alternate funding sources included grants and undergraduate teaching opportunities for doctoral students.

Others were aware of this prevailing belief that doctoral programs do not generate revenue and argued the opposite: “Most faculty, when they want to start a doctoral program, they repeat this thing that they hear, which is ‘doctoral programs cost money, they don’t make money.’ And that’s not true.” These participants proposed that student tuition should be used to fund doctoral programs. One participant argued that if tuition exceeded the cost of faculty salaries, the program was likely to be generating revenue. This participant believed that counseling programs could generate money because they were relatively inexpensive. Unlike hard science disciplines, CES doctoral programs do not require expensive lab equipment, and CES faculty salaries are “lower compared to other programs.”

Tangible Benefits to Ecosystem: “How Do We Help?”

Participants discussed that administrator support for a doctoral program can be bolstered through demonstrations of how the program is supporting the local community. One participant shared that their program provides data to administrators about the number of hours of free counseling that the program provides to the community, which in turn helps the dean to gain the provost’s support for the program. Such data can help administrators when they conduct a cost–benefit analysis for whether to start a new program or sustain an existing program. Likewise, another participant encouraged faculty to take an “ecological view” and consider “how do we help . . . the surrounding communities?”

Need for Resources: “Pit Bulls in a Fighting Ring”

Participants discussed the need to address the competition for resources when attempting to gain administrator support. Participants mentioned the scarcity of resources that included faculty positions (i.e., lines) and physical building space. This scarcity resulted in programs needing to compete for resources. One participant stated, “I think we’re all going to be like pit bulls in a fighting ring over resources at this point.” Another participant shared a similar statement: “Once we get outside of our building, it is very territorial. So, we have to basically anticipate resistance from other pockets in the university if we want a new program at the doctoral level.” This participant elaborated that the provost needs to be aware of these dynamics and that faculty should attempt to make a strong case for needing resources if they are in competition with other programs.

Competition for resources seemed to occur not only within a university’s departments but also between CES programs at different universities. Doctoral applicants appear to be increasingly making enrollment decisions based on tuition costs and graduate assistantships, which increases the pressure for programs to provide financial support packages. One participant reported that it is becoming less feasible to operate a doctoral program without “some form of stipend or assistantship” because “if you don’t, there’s too many other programs that do.” This participant elaborated that administrators must support the program with assistantships and concluded, “I wouldn’t try to start a program without it.”

Some participants discussed strategies to maximize resources across the college or school in which the program exists, such as with college-wide methodology courses. Such strategies seemed particularly important when adapting to the pressure of accepting more students to make the program revenue-neutral. One participant suggested that such resource sharing was “of utmost importance… in the early beginnings of programs.”

Faculty and Program Responsibilities

Faculty have more complex responsibilities when operating a doctoral program compared with a master’s program, such as attending conferences with students and engaging in the larger campus community. As one participant stated, “It’s also being at events, interacting with administrators, making sure when walking around campus or buildings that they know who you are and that they can connect with what you’re doing.” Participants explored the economic aspects of the responsibilities that individual faculty members and the larger program have when responsible for the doctoral education of counseling students: “At our institution, you don’t get a lot of credit per se, or release time or extra pay for all of the work it takes to mentor doctoral students.” This credit that is or is not allocated to doctoral education impacts faculty members’ well-being. Another participant cautioned faculty to be aware of “faculty burnout” that accompanies tensions around adequately funding faculty positions: “If you shrink, and you still maintain the same number of students, there is simply not enough time, not enough emotional capacity, to do the good work.” Another participant shared that their doctoral programs felt like “hell on wheels” because “we ended up with a program that had more than 100 students with two real tenured faculty running the program.”

Influence of University: “Know the Size and Culture”

This subtheme represented faculty considerations of the larger university system context where the counseling program is situated. As one participant summarized, “part of it is looking at the context of the program in the university.” Participants particularly referenced size as an influencing factor. As one participant stated, “Know the size and culture of your institution.” University size influenced participants’ access to decision-makers: “We’re so small that I could literally walk out of my office and two minutes later I can be in the provost’s office. I can ask a question. They’re very approachable, and so I don’t feel intimidated.” Understanding the institution’s mission and its funding priorities is crucial to forging successful alliances with administrators regarding whether to start and sustain a CES doctoral program. Understanding where a CES doctoral program fits within the institution’s academic structure therefore helps faculty to effectively communicate with administrators, and consistently reviewing this can help inform ongoing dialogues with administrators.

Identity Landscape

The overarching identity landscape theme represents how programs both understand their internal identity regarding doctoral education, as well as the external identity factors that contribute to the program. Each subtheme is detailed below with participant quotes.

Operationalize and Define Commitment: “Faculty Have to Buy In”

Gaining faculty buy-in prior to conversations with administrators and gaining approval for a doctoral program was a consistent message relayed by participants. One participant reflected, “Everybody has to be on board and has to buy in to the concept that the mission can’t be the mission of one person.” Another participant recommended that faculty leadership (e.g., program directors) need to operationalize this commitment through intentional dialogues with faculty. This participant stated that “the evidence for faculty buy-in isn’t always there until you probe.” They elaborated that faculty leadership can facilitate discussions around the following questions: “Are you willing to do X, are you willing to do Y?” and “If we start a doctoral program, do you feel like you have the skills you’ll need or do you fear that you’re going to be left behind?” Such conversations appeared important to developing a unified collective commitment to the doctoral program, which was critically important when challenges arose. Other participants reflected on personal buy-in and encouraged self-reflection in this regard: “Things to consider including one’s own personal meaning making.” Participants reflected that doctoral education was significantly different than master’s-level education and required a different level of commitment. Administrators are unlikely to support a doctoral program if the faculty are divided in their commitment to the program.

Understanding Differences: “Know What Your Program Is Worth”

Participants spoke about the need for faculty to possess knowledge about multiple aspects of doctoral education when conveying information to administrators. Faculty should be familiar with the differences between master’s and doctoral education, between doctorates in other disciplines within the university, and among doctoral programs at different universities in the state. This information assists faculty “to really know what your program is worth and to be able to explain it.” For example, faculty should make administrators aware of how doctoral education can enhance master’s-level training rather than result in master’s students being “ignored” and treated as “second class citizens.”

Participants indicated that administrators may not be familiar with the counseling profession and thus may need education. Participants reported the need for “educating your administrative colleagues about what counselor ed is, what they do, how we train.” Another participant stated that “even at the dean level, they don’t know what the heck a mental health counselor is. Not a clue.” Consistent with this, administrators may also need information about other aspects of the profession, such as the value of specialized accreditation. One participant reported, “I think that we can do a better job of telling our admin the pros of CACREP versus the cons.” Education about CACREP accreditation was important because of the costs associated with accreditation fees and hiring core faculty to meet the CACREP doctoral standards.

Quality in Programs: “High-Quality Output”

Participants reflected on the importance of program quality as a reflection of the programs’ overall identity. Program outputs seemed to be a particularly important measure of program quality. Some participants, particularly those at research-intensive universities, emphasized the importance of research-related outputs such as “grants, high-quality output, and visibility.” Across participants, employment rates were a particularly important measure of program quality, especially employment in academic and administrative jobs post-graduation. Participants reported that such metrics were useful as a “selling point” to administrators, especially if needs existed for doctoral-level graduates in the local area. As one participant stated, “Some of those outcomes become really important to administrators, and I think that we need to be good at putting those outcomes in front of them.”

Participants also shared concerns with program quality. These concerns often centered on admitting more students than can be adequately mentored through the dissertation process. One participant was “concerned about doc programs that bring in cohorts of 20 and churn them out” because they feared that “big doc programs” are “just course-based models without a whole lot happening outside of that. . . . And, you know, I worry about dissertation mentoring.”

Program accreditation was explored as an influencing factor in program quality that ultimately influences the overall program identity through reputation. One participant stated, “We built the program around the accreditation standards and took those standards very seriously.” Another participant explored how the accreditation process can influence administrators’ opinions of the program: “If we had bombed that visit, from the president to the vice president on down, we would have looked really bad.”

Advancing the Institutional Mission: “It Has to Match”

Study participants commented on the importance of the identity of the doctoral program connecting to the mission of the larger institution. One participant encouraged faculty to consider the institutional mission when communicating with administrators: “When we advocate for programs, we need to understand the mission of the institution.” This participant reported that administrators in a university that values community service may be in favor of doctoral programs that “create more service providers for the local community.” Another participant stated that “it has to match the university’s mission. I hear that more and more and more.” This participant acknowledged that a proposed doctoral program would only receive administrative support if it “fits with the strategic plan of the university.” Participants indicated that the program should align not only with the institutional mission but also with the mission of the college or school where the program is housed.

Stakeholder Dynamics: “Making the Administrators Happy”

Participants discussed the variety of stakeholders that faculty should consider when developing a CES doctoral program. Such stakeholders include the students being educated, faculty in the program, administrators who make decisions about the program, and employers of future program graduates. Participants reflected that each stakeholder group can contribute meaningfully to the identity of the program.

At times, a stakeholder group’s contributions and agendas may be at odds with those of another stakeholder group. This is particularly problematic when tensions exist between a stakeholder group and administrators. For example, faculty may prefer a smaller program than administrators. One participant stated that “one of the things that I’ve fought with faculty about my whole life, has been that [faculty] want small classes and they want few students.” This participant added that administrators tend to close smaller programs when pressured to cull the number of doctoral programs at an institution, and thus smaller size represents a potential threat to the program: “Any time an administrator is going to cut a program or deny resources to a program, they do it with the program with the least number of students in it. It’s just the absolute way it’s done.” This participant proposed that faculty stakeholders must therefore understand the dynamics of higher education administration when advocating, as “making the administrators happy with the numbers” is an important priority.

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a qualitative analysis of interviews with 15 experts in the field to examine the research question. We identified participant-reported strategies for gaining initial and ongoing support from administrators for a CES doctoral program. The overarching themes of political, economic, and identity landscapes emerged from the data, alongside associated strategies necessary for gaining support. Navigation of complex university systems, including accreditation, finances, legal concerns, infrastructure, and politics, seem to be required for successful initial administrator approval of a CES doctoral program. Awareness of institutional mission and history, purpose, community needs, fiscal realities, and the university’s organizational chart also can facilitate approval and successful program sustenance.

Implications for CES Faculty

The findings from this study may be utilized by existing master’s degree counseling program faculty who want to create a CES doctoral program. Faculty should embark on a data-driven process to inform administrators of tangible benefits across multiple systems and articulate the financial resources necessary for long-term success. As new CES doctoral programs are proposed, faculty should ensure that university administrators are aware of the relative worth of counselors and counselor educators, particularly in contrast to other mental health disciplines that may exist on campus. They may need to document the tangible benefits that CES programs bring to the university that are in alignment with the university’s mission and strategic plan. In 2013, Adkison-Bradley noted, “As universities change and grow, academic programs are often required to justify their request for resources or asked to explain how they uniquely contribute to the overall mission of the college and surrounding communities” (p. 48). Faculty could benefit from open dialogue with administrators and mentors about what it costs the institution to have a doctoral program compared to what revenue and resources a doctoral program can generate. CES faculty also can provide data to explain how accreditation requirements that may appear expensive to administrators (e.g., 1:6 faculty–student ratios in practica; 1:12 faculty–student ratios) do benefit students, clients, and communities, including protection of “broad public interests” (Urofsky, 2013, p. 13).

Faculty must engage in systemic thought that goes beyond the program and department. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems model provides a useful model for program faculty to understand. This model includes four main systems in which individuals exist—microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem, with each system growing in size and complexity. Faculty without this perspective risk experiencing their department in a bubble and may not realize how their smaller microsystem (i.e., program, department) fits within the larger macrosystem of the university. The political landscape can become entangled in the developing exosystem where these systems overlap. This exosystem includes considerations for the college’s or school’s strategic priorities where the doctoral program is located. Faculty also should consider larger systemic interactions, such as the doctoral program’s relationship with the local community, with other master’s and doctoral programs in the state, and with other doctoral programs nationally.

The 2016 CACREP Standards (2015) require doctoral education to focus on leadership. However, the standards require this education to be in relation to counselor education programs and in professional organizations, not specifically in institutions of higher education as larger systems. It is unknown how or if students receive formal education about how to navigate university systems, as it is not typically included in CES doctoral program curricula. However, in our own personal experiences as faculty members and doctoral students, we have found that this knowledge seems to be acquired through observation, experience, and on-the-job mentoring. Unfortunately, this learning may occur when new and junior faculty are under pressure to establish themselves for tenure and promotion. Senior faculty, including those nearing retirement, are likely to possess this systemic knowledge and understanding. This knowledge could be conveyed via formal or informal mentoring programs; however, junior faculty in counselor education programs report a lack of mentoring experiences (Borders et al., 2011). The lack of mentoring could be from a variety of reasons, as junior faculty members may be intimidated by senior faculty (Savage et al., 2004), or senior faculty may lack the commitment to put forth the long-term effort to gain support for a new CES doctoral program.

Faculty must be willing to invest in learning about the processes involved in doctoral program creation—to listen, be respectful, and exercise patience for the time required for program approval, funding, and development. The results of this study indicate that program generation is a political process, and junior faculty must be aware of their environment. Faculty have different levels of input and leadership at different institutions, such as with different forms of shared governance (Crellin, 2010). Faculty who do not understand political savviness, the role of fiscal constraints, and the historical precedents for doctoral program initiation may struggle more than those who understand the lens by which individual institutional decisions are made.

Implications for University Administrators

University administrators could utilize the results of this study to understand how to work with faculty who are requesting the initiation of a new doctoral program. Administrators could consider establishing dedicated time and orientation to new and junior faculty to assist them in conceptualizing how faculty requests are prioritized within the institution, perhaps via a formal mentoring program (Savage et al., 2004). For example, if the university’s current vision is to respond to the lack of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) graduates in the local job market, counseling faculty could better manage their expectations about the estimated timeline of new degree program creation while aligning their new CES doctoral degree proposal to a more attainable target date. Communication about the timeline of decisions and the patience involved in systemic change (e.g., state legislature involvement) could also benefit the faculty perspective. Opportunities for learning about the organization are a crucial ingredient in organizational change (Boyce, 2003).

Although it is the responsibility of deans and department chairs to communicate the university’s vision and strategic plan, administrators should also trust the CES faculty’s distinct knowledge of the field and dynamic accreditation standards. Faculty are uniquely qualified to anticipate shifts in the profession that could impact their programs. From our experience, CES faculty who serve as internship clinical supervisors may also possess unique knowledge of the needs of the surrounding communities through their supervisees’ reports of client needs.

It is suggested that administrators include a university organizational chart in new faculty orientation or in the faculty handbook so that faculty can be aware of the hierarchy within the university. The orientation should include a clear explanation of how the particular institution prioritizes agendas and provide a history of the institution, with specific examples of prior program creation in the face of competing needs (e.g., missions, financial). Faculty can then understand how the university invests in its future.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Several limitations exist with qualitative research in general, and with this unique project specifically. In general, qualitative research is limited by researcher bias, interviewer bias, interviewee bias, and participant demographics (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). To control for potential bias during the analysis process, the coding team used several strategies to enhance trustworthiness, including recruiting coding team members who had identities as both CES faculty and administrators, bracketing biases throughout coding, using consensus to resolve discrepancies in coding, and using memos to document decisions. Future studies could seek to triangulate the data from this study to determine whether the findings are transferable to the perspectives of other faculty in CES doctoral programs.

The focus of this particular research study was to explore faculty perspectives regarding how to gain administrative support for initiating and sustaining CES doctoral programs. As such, the perspectives of administrators were not surveyed regarding how to gain administrative support for CES doctoral programs (beyond those counselor educator faculty participants who have served in administrative roles). Future studies, perhaps in the form of quantitative research, could include these perspectives to determine whether the perspectives of CES doctoral faculty are consistent or divergent with administrator experiences regarding how to work effectively with administrators.

We sought to understand strategies for successfully gaining initial and ongoing administrative support for a CES doctoral program. This exploration included both participants who had recently started new programs and those who had long worked in CES doctoral programs. However, an analysis of thematic differences between participants who had and had not spearheaded the creation of a CES doctoral program was not conducted. Future research could explore whether strategies varied for those who had recently started a CES doctoral program versus those who had not. In addition, data were not organized and analyzed by differences in participants’ institution type (i.e., private or public), because it was outside the scope of the research question. Finally, the study focused solely on faculty at CACREP-accredited institutions. It is unknown whether the perspectives of participants in this study would be consistent with faculty at non–CACREP-accredited institutions.

Conclusion

The counseling profession continues its efforts to address the pipeline shortage of doctoral-level CES faculty to meet CACREP accreditation requirements. To meet this need, some master’s-level programs are seeking to start CES doctoral programs. The findings from this study may be useful to CES faculty when planning a strategic approach for collaboration with administrators regarding the initiation of new CES doctoral programs. This strategic approach will involve exploring political elements, economical components, and the identity of the proposed program. The findings of this study indicate these areas of knowledge promote a more comprehensive planning process to help prepare for working with administrators on the creation of a doctoral program.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Adkison-Bradley, C. (2013). Counselor education and supervision: The development of the CACREP doctoral standards. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00069.x

Borders, L. D., Young, J. S., Wester, K. L., Murray, C. E., Villalba, J. A., Lewis, T. F., & Mobley, A. K. (2011). Mentoring promotion/tenure-seeking faculty: Principles of good practice within a counselor education program. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50(3), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2011.tb00118.x

Boyce, M. E. (2003). Organizational learning is essential to achieving and sustaining change in higher education. Innovative Higher Education, 28(2), 199–136. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IHIE.0000006287.69207.00

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Brooks, K., Yancey, K. B., & Zachry, M. (2002). Developing doctoral programs in the corporate university: New models. Profession, 89–103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25595734

The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. (2019). Basic classification description. http://car

negieclassifications.iu.edu/classification_descriptions/basic.php

Cartwright, A. D., Avent-Harris, J. R., Munsey, R. B., & Lloyd-Hazlett, J. (2018). Interview experiences and diversity concerns of counselor education faculty from underrepresented groups. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12098

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). SAGE.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2008). 2009 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2009-Standards.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Crellin, M. A. (2010). The future of shared governance. New Directions for Higher Education, 2010(151), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.402

Field, T. A., Snow, W. H., & Hinkle, J. S. (2020). The pipeline problem in doctoral counselor education and supervision. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 434–452. https://doi.org/10.15241/taf.10.4.434

Haas, B. K., Yarbrough, S., & Klotz, L. (2011). Journey to a doctoral program. Journal of Professional Nursing, 27(5), 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2011.04.006

Hill, N. R., Leinbaugh, T., Bradley, C., & Hazler, R. (2005). Female counselor educators: Encouraging and discouraging factors in academia. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83(3), 374–380.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00358.x

Lambie, G. W., Ascher, D. L., Sivo, S. A., & Hayes, B. G. (2014). Counselor education doctoral program faculty members’ refereed article publications. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 338–346.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00161.x

Magnuson, S., Norem, K., & Lonneman-Doroff, T. (2009). The 2000 cohort of new assistant professors of counselor education: Reflecting at the culmination of six years. Counselor Education and Supervision, 49(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00086.x

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Wiley.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE.

Preston, J., Trepal, H., Morgan, A., Jacques, J., Smith, J. D., & Field, T. A. (2020). Components of a high-quality doctoral program in counselor education and supervision. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.15241/jp.10.4.453

Savage, H. E., Karp, R. S., & Logue, R. (2004). Faculty mentorship at colleges and universities. College Teaching, 52(1), 21–24. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.52.1.21-24

Slater, C. L., & Martinez, B. J. (2000). Transformational leadership in the planning of a doctoral program. The Educational Forum, 64(4), 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720008984775

Smith, R. L., Flamez, B., Vela, J. C., Schomaker, S. A., Fernandez, M. A., & Armstrong, S. N. (2015). An exploratory investigation of levels of learning and learning efficiency between online and face-to-face instruction. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 6(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137815572148

Urofsky, R. I. (2013). The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs: Promoting quality in counselor education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 6–14.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00065.x

West, J. D., Bubenzer, D. L., Brooks, D. K., Jr., & Hackney, H. (1995). The doctoral degree in counselor education and

supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(2), 174–176.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01846.x

Rebecca Scherer, PhD, NCC, ACS, CPC, is an assistant professor at St. Bonaventure University. Regina Moro, PhD, NCC, BC-TMH, LPC, LMHC, LCAS, is an associate professor at Boise State University. Tara Jungersen, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, LMHC, is an associate professor and department chair at Nova Southeastern University. Leslie Contos, NCC, CCMHC, LCPC, is a doctoral candidate at Governors State University. Thomas A. Field, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, ACS, LPC, LMHC, is an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Medicine. Correspondence may be addressed to Rebecca Scherer, B43 Plassman Hall, 3261 West State Road, St. Bonaventure, NY 14778, rscherer@sbu.edu.

Feb 20, 2017 | Volume 7 - Issue 1

Laura Boyd Farmer, Corrine R. Sackett, Jesse J. Lile, Nancy Bodenhorn, Nadine Hartig, Jasmine Graham, Michelle Ghoston

Using quantitative and qualitative analysis, the perceived impact of post-master’s experience (PME) during counselor education and supervision (CES) doctoral study was examined across five core areas of professional identity development: counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy. The results showed positive perceptions of the impact of PME in four of the five core areas, with significant relationships between the amount of PME and perceived impact on supervision and leadership and advocacy. Implications inform CES doctoral admissions committees as well as faculty who advise master’s students interested in pursuing a doctoral degree in CES.

Keywords: counselor education and supervision, doctoral study, post-master’s experience, doctoral admissions, professional identity

The master’s degree in counseling serves as the entry-level degree in the field, and students entering a doctoral program in counselor education and supervision (CES) are believed to have already met the standards of an entry-level clinician (Goodrich, Shin, & Smith, 2011). Therefore, the doctoral degree in CES is to prepare counselors for leadership in the profession within a variety of roles including supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy, as well as counseling practice (Bernard, 2006; Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2015; Goodrich et al., 2011; Sackett et al., 2015). Though CACREP (2015) recognizes previous professional experience as one of the doctoral program admission criteria, the counselor education field lacks clear professional standards regarding the amount and type of counseling experience necessary for admittance to doctoral programs (Boes, Ullery, Millner, & Cobia, 1999; Sackett et al., 2015; Schweiger, Henderson, McCaskill, Clawson, & Collins, 2012; Warnke, Bethany, & Hedstrom, 1999). Conventional wisdom may tell us the more post-master’s counseling experience a doctoral applicant has, the more enriched their doctoral experience will be; however, the CES field does not have empirical data for how CES doctoral students perceive the impact of their post-master’s experience (PME) on their doctoral education. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to explore the perceived impact of PME on doctoral study in CES.

In this study, researchers explored the perceived impact of PME across the five core areas of doctoral professional identity development outlined by CACREP (2015; Section 6. B.1-5). The following research questions guided the study: (1) How do advanced doctoral students and recent doctoral graduates perceive the impact of PME on the development of the five core areas of professional identity during doctoral study: counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy? and (2) Is the amount of PME and the setting of PME related to the perceived impact of PME on the five core areas of professional identity during doctoral study: counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy? Practically, the results inform CES doctoral admissions committees in considering applicants with and without PME. CES doctoral admissions committees must decide whether and how much PME should be required for admittance to their programs. PME is an important consideration in selecting doctoral students, yet few applicants have this experience (Nelson, Canada, & Lancaster, 2003), making it difficult to require. The results also inform CES faculty who advise master’s students interested in pursuing a doctoral degree. CES faculty members frequently encounter ambitious master’s students who are interested in pursuing a doctoral degree, and one of the many considerations in that conversation is whether and how much PME should be obtained before doctoral study begins. Though PME is deemed important, many CES faculty members advise master’s students to go straight into doctoral study based on factors such as maturity, academics and skill level (Sackett et al., 2015). This is an issue for the field since experience is an important qualification in hiring CES faculty members (Bodenhorn et al., 2014; Rogers, Gill-Wigal, Harrigan, & Abbey-Hines, 1998) and clinical experience informs teaching (Rogers et al., 1998; Sackett et al., 2015), supervision (Sackett et al., 2015), and research (Munson, 1996; Sackett et al., 2015). Thus, exploring further the impact of PME on doctoral students’ development is critical.

Relevant CES Literature on Post-Master’s Experience

The field of CES lacks clarity regarding the amount or type of counseling experience preferable for incoming doctoral students (Sackett et al., 2015; Schweiger et al., 2012; Warnke et al., 1999). Recently, Swank and Smith-Adcock (2014) found that most CES doctoral programs in their study recommended, rather than required, one to two years of clinical experience for admission, while some suggested licensure for admission. Similarly, Nelson et al. (2003) found that counseling experience was a necessary component to doctoral admissions, though program representatives relayed the difficulty in requiring PME since so few applicants have experience. Twenty of the 25 CACREP-accredited programs in their sample rated successful work experience as a criterion for admission to their doctoral programs. Sixteen of those reported that work experience is always or often helpful in selecting strong doctoral students. CES doctoral programs deem experience is important in admissions, yet CES faculty members often advise master’s students to go immediately into doctoral programs (Sackett et al., 2015). Thus, there will likely continue to be a shortage of experienced doctoral applicants for doctoral admissions committees to choose from. As such, it is critical to explore the impact of PME on the areas of CES study to inform advisors at the master’s level how to advise their students on gaining PME prior to pursuing doctoral work.

Sackett et al. (2015) conducted a recent study to explore how CES faculty are advising master’s-level students interested in doctoral work regarding the amount of PME to obtain beforehand. CES faculty expressed the significant influence of clinical practice on the areas of teaching, research and supervision. Respondents identified the importance of clinical experience in providing for stimulation in research and in establishing credibility in teaching and supervision. Though there was much support for PME in the qualitative findings from this study, many respondents emphasized individual circumstances in evaluating readiness for doctoral work in CES, such as age, maturity, academics and skill level. For other respondents, the experience gained through master’s and doctoral training was enough, especially in cases where students were working in clinical capacities while completing their doctoral degrees. Thus, there is some indication in CES that PME is an important consideration in doctoral student admissions (Nelson et al., 2003; Swank & Smith-Adcock, 2014) and some indication that CES faculty members perceive the importance of PME in the areas of teaching, supervision and research (Sackett et al., 2015). The current study adds to the literature by exploring CES doctoral students’ perceptions of PME on their experiences in doctoral study.

Other Helping Professions’ Literature on PME

Related disciplines are concerned with the question of PME as well. In marriage and family therapy, students with clinical experience have been rated as better clinicians by faculty than those who did not have clinical experience (Piercy et al., 1995). Proctor (1996) and Munson (1996) wrote about opposing viewpoints on whether social work doctoral programs should admit students with limited to no post-master’s in social work (MSW) experience. Proctor’s stance was that requiring post-MSW experience for admission to doctoral programs in social work was a detriment to the field, as it meant the discipline might miss out on students who are research-minded and eager to continue with their education. On the other hand, Munson argued that post-MSW experience is essential for graduates of social work doctoral programs to fulfill the needs of the field, which include building knowledge, conducting practice research and effectively teaching social work practice. In clinical psychology, O’Leary-Sargeant (1996) found academic criteria to be most important in doctoral student admissions, while clinical competence also was important. It appears that determining PME’s place in the priority list for doctoral admissions and its impact on doctoral work is a concern for related disciplines as well.

As there are no clear guidelines for considering PME in doctoral student admissions (Sackett et al., 2015; Schweiger et al., 2012), and empirical studies exploring the doctorate in counselor education are scarce (Goodrich et al., 2011), with none specifically exploring the perceived impact of PME on doctoral students’ experiences, researchers set out to add to the literature in this area. Both doctoral admissions committees and faculty members advising master’s students who wish to pursue doctoral study encounter the dilemma of if and how much PME experience is important to gain prior to pursuing doctoral work. Given this, the purpose of this study was to explore the perceived impact of PME on the five core areas of doctoral professional identity: counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy.

Method

To investigate the perceived impact of PME on doctoral study, quantitative and qualitative methods were utilized for their complementarity (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2007). The study was guided by the research questions: (1) How do advanced doctoral students and recent doctoral graduates perceive the impact of PME on the development of the five core areas of professional identity during doctoral study: counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy? and (2) Is the amount of PME and the setting of PME related to the perceived impact of PME on the five core areas of professional identity during doctoral study: counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy? Institutional Review Board approval was acquired prior to data collection. The researchers asked participants to rate the perceived impact of their PME or lack of PME using an 11-point Likert scale (-5 to +5; strong negative impact to strong positive impact), and analyzed themes using participants’ responses to open-ended questions for the five core areas of doctoral professional identity.

Participants

Fifty-nine advanced doctoral students or recent graduates completed an online questionnaire. To define participants’ status to degree completion, all fell into one of three groups: recent doctoral graduates (completed a CES doctoral degree within the last three years), ABD doctoral students (all but dissertation; completed all coursework and were working on dissertation studies), and advanced doctoral students (two years into completing coursework). Among participants, 13 (22%) were recent doctoral graduates, 32 (54%) were ABD doctoral students, and 13 (22%) were advanced doctoral students. One participant did not answer this question.

Participants were asked to indicate the type of setting and experience that best described their PME, checking all items that applied. There were 10 options provided and an option for “other” that included a comment box. Forty-nine percent (n = 29) indicated PME in community-based agencies, 31% (n = 18) worked in K–12 school settings, 20% (n = 12) worked in private practice, and 7% (n = 4) worked in inpatient settings. Four participants indicated post-master’s work in more than one setting. Additionally, 37% (n = 22) indicated that their PME provided experiences working with diverse populations, 31% (n = 18) gained experience working with families, and 24% (n = 14) gained experience working with clients who had substance use issues. Less than 10% of participants indicated other counseling settings and experiences such as play therapy, bilingual counseling, day treatment and in-home counseling.

The 59 participants indicated a range of time spent in PME from zero years up to 19 years before entering doctoral study. Thirty-four percent (n = 20) indicated between zero and one year of experience, 25% (n = 15) between one and three years of experience, 19% (n = 11) between three and five years of experience, 17% (n = 10) between five and 10 years of experience, and 5% (n = 3) indicated more than 10 years of PME prior to entering doctoral study.

Procedure

Survey links were distributed through two national electronic list-servs, CESNET (the Counselor Education and Supervision NETwork) and COUNSGRAD (for graduate students in counselor education). The study invitation was sent to the listservs on two separate occasions approximately one month apart. Simultaneously, the study invitation was sent to regional Association for Counselor Education and Supervision leaders requesting that it be distributed to their membership lists. Additionally, CACREP liaisons were asked to send the survey link and invitation to their doctoral students. The survey was delivered through SurveyMonkey, a commonly used software product with a secure feature that was used for this research. The following research question was identified to potential participants: How do doctoral students and recent doctoral graduates reflect on how their post-master’s counseling experience or lack of experience impacted their experiences as a doctoral student? A response rate could not be calculated, as it is not possible to identify how many potentially appropriate participants received the research request.

PME Questionnaire

The authors collaborated on identifying questions that would serve to answer the research questions, focusing on five core areas of doctoral professional identity: counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy. Two questions were asked about each of the five areas. “To what extent do you believe your post-master’s experience impacted your ability to develop [area] skills in your doctoral program?” used an 11-point Likert scale with the end points being (-5) strong negative impact and (+5) strong positive impact. Following the scaling question, an open-ended follow-up question was asked: “Please comment on how your experience impacted your [area] skills, and whether more or less experience would be beneficial.” Basic demographic questions were included regarding the type of experience gained prior to doctoral study, length of doctoral study and year of graduation. A pilot survey was sent to six people: two recent doctoral graduates, two ABD doctoral students, and two advanced doctoral students completing coursework. Feedback was provided on clarity and time involved.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analyses included correlation and multiple linear regression to examine the relationship between the amount of PME obtained and the perceived impact on the five core areas of doctoral study. The research team hypothesized that the amount of PME would predict a positive relationship with the perceived impact on some core areas of doctoral study, although which core areas would be statistically significant were unknown. Therefore, this study represents an exploration of the relationships between previously unexamined variables in the literature.

An independent samples t-test examined the relationship between PME setting (clinical mental health or school) and the perceived impact of PME on the five core areas. For this analysis, several setting options (community-based agencies, private practice and inpatient hospitals) were combined into one setting labeled “clinical mental health,” which was compared to K–12 school settings (labeled “school”). The research team hypothesized that there would be no statistically significant differences between PME setting and any of the five core areas of doctoral study. There are no prior studies that examine these variables.

For the qualitative analysis, the first, third and fourth authors served as the data analysis team. The data analysis team analyzed responses to the open-ended questions using a constant comparative method described by Anfara, Brown, and Mangione (2002). Additionally, the team used a form of check coding described by Miles and Huberman (1994). The team members independently completed a first iteration of data analysis by assigning open codes for each of the five open-ended questions by reading responses to each item broadly and observing regularities (Anfara et al., 2002). The team members completed a second iteration of analysis, which included comparison within and between codes to establish categories and identify emergent themes. The constant comparative method provided a systematic way to analyze large amounts of data by organizing it into manageable parts first, and then identifying themes and patterns.

For the final step of analysis, the data analysis team rotated through a process of peer review as recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994). For each open-ended question, two team members were assigned as coders and one was assigned the role of peer reviewer. Once the team members arrived at individually derived themes, the team met together to discuss the findings and arrive at consensus for naming themes. During this meeting, the peer reviewer led the discussion by probing and seeking clarification on the original comment wording, thus helping the team to reach consensus for the themes. Consensus was reached when the three team members came to agreement on the final themes. The data analysis team sent the original data and final themes for each of the five core areas to the remaining four authors, who served as additional peer reviewers by examining the analysis.

Results

Quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted in this study of the perceived impact of PME on the five core areas of doctoral development for advanced doctoral students completing coursework, ABD doctoral students, and recent doctoral graduates. The results are presented in the following sections, with discussion to follow.

Quantitative Results: Correlation, Multiple Regression and Independent Samples T-test

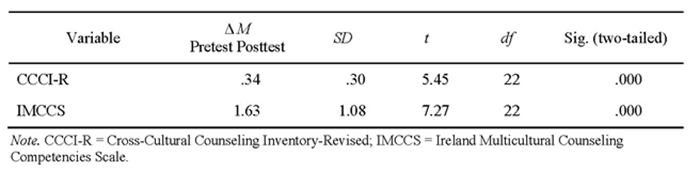

Correlational analysis was used to explore the relationships among all variables: amount of PME obtained (years), and the perceived impact of PME on counseling, supervision, teaching, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy. A correlational matrix presents the relationships among the variables in Table 1. Among significant relationships, the amount of PME was related to perceived impact on development in supervision (r(57) = .43, p < .01) and leadership and advocacy (r(57) = .39, p < .01).

Table 1

Correlation Matrix for Main Study Variables

Note. Variables 2–6 represent the perceived impact of PME on the core area of doctoral identity development (counseling, teaching, supervision, research and scholarship, and leadership and advocacy)