Defining Moment Experiences of Professional Counselors: A Phenomenological Investigation

Diane M. Coll, Chandra F. Johnson, Chinwé U. Williams, Michael J. Halloran

A defining moment experience is a pinnacle moment or critical incident that occurs within a therapeutic context and contributes significantly to the professional development and personal growth of counselors. The aim of this qualitative study was to investigate how experienced counselors make sense and meaning of their defining moment experiences in terms of developing their clinical attributes. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine experienced professional counselors to investigate how defining moment experiences influenced their professional development. Five main themes were derived from analysis via interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): acceptance reality, finding a balance, enhanced self-reflection and awareness, reciprocal transformation, and assimilation and integration. These themes provide perspectives on how facilitating conversations and reflection on defining moment experiences may enhance professional development and clinical attributes among counselors.

Keywords: defining moment experiences, professional development, clinical attributes, qualitative study, interpretative phenomenological analysis

The defining moment experience is a contemporary term to describe a pinnacle moment or critical incident that occurs within a therapeutic context and contributes to professional development and the personal growth of professional counselors (Prengel & Somerstein, 2013; Veach & LeRoy, 2012). The defining moment experience typically occurs in the early stages of counselor development and is considered a rite of passage, often serving as a catalyst for significant growth (Furr & Carroll, 2003; Lee, Eppler, Kendal, & Latty, 2001; Skovholt, 2012; Skovholt & McCarthy, 1988). A negative defining moment experience might entail initial exposure to a difficult client, which may have a negative influence on counselor perceptions of clinical competency. In contrast, a positive defining moment experience could involve a novice counselor’s first experience of effectiveness or making a therapeutic breakthrough with a client (Skovholt, 2012). Whether positive or negative, defining moment experiences provide great potential for counselor self-reflection and growth on professional and personal levels (Howard, Inman, & Altman, 2006).

Defining moment experiences are more likely to occur and have greatest influence among novice and early-career counselors from a counselor developmental perspective (Lee et al., 2001). In theory, novice counselors face several stressors, such as performance anxiety, rigid emotional boundaries, an incomplete practitioner-self, glamorized expectations, and inadequate conceptual maps (Skovholt & Rønnestad, 2003). Defining moment experiences are likely to intensify these stressors and existing growing pains in terms of confidence and perceptions of identity within the counseling profession (Patterson & Levitt, 2011). Novice counselors also may find themselves deeply questioning their personal beliefs, biases, and assumptions, which can lead to some level of personal transformation or significant growth (Skovholt, 2012). Nevertheless, Furr and Carroll (2003) argued that the first defining moment experience carries the potential to accelerate counselor development regarding their behaviors (e.g., performance-based skills), cognitions (e.g., simple to complex), and emotions (e.g., feelings of inferiority or self-efficacy).

Several research studies have confirmed these propositions. Indeed, Bischoff, Barton, Thober, and Hawley (2002) reported that the initial counseling session with a client was a defining moment experience among early-career counselors having both a positive and negative influence on their self-efficacy. Similarly, Furr and Carroll (2003) reported direct client experience to be a defining moment in the development of counseling students, leading them to increased self-understanding and confidence as well as recognition of personal deficiencies. A qualitative study by Howard et al. (2006) also investigated defining moment experiences among practicum counseling students as they pertained to their overall professional growth. The findings suggested defining moment experiences influenced their professional identity, personal reactions, competence, supervision processes, and counseling philosophy.

Defining moment experiences also have been found to be important in the ongoing development of professional counselors (Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2003). In their study over 30 years ago, Skovholt and McCarthy (1988) asked 58 mental health professionals with varying degrees of experience and credentials to submit narrative accounts of their own defining moment experiences. Common themes developed from the narratives included feelings of insecurity, learning to accept imperfections and limitations, transforming the experience into a specialty, the attitude of readiness to learn and grow from the experience, and dealing with unexpected events such as the suicide of a client. More recently, Veach and LeRoy (2012) reported several common themes in the defining moment essays of 37 professional counselors, including increased empathy, authenticity, honesty, self-awareness, resilience, compassion, connection, courage, and commitment. Two other publications (Prengel & Somerstein, 2013; Trotter-Mathison, Koch, Sanger, & Skovholt, 2010) have similarly used personal narratives of professional counselors to illustrate the significance of defining moment experiences in the ongoing development of counselors.

Theories of counselor development maintain that the process of growth and change continues throughout the career lifespan of counseling professionals, but may nonetheless entail different challenges at distinct stages of counselor development (Moss, Gibson, & Dollarhide, 2014; Skovholt & Rønnestad, 2003; Zahm, Veach, Martyr, & LeRoy, 2016). For novice counselors, defining moment experiences are likely to intensify pre-existing stressors and provide a significant opportunity for professional development (Skovholt & Rønnestad, 2003). In contrast, experienced counselors are more likely to be able to reflect and process the latent meanings of defining moment experiences for their own ongoing professional growth and development (Moss et al., 2014), making them a valuable resource for understanding the developmental effects of defining moment experiences. Yet there is little systematic research on how defining moment experiences contribute to the practice of experienced professional counselors. This study addressed this shortfall in the research literature by focusing on the following research question: How do experienced counselors make sense and meaning of their defining moment experiences with respect to their professional development and practice?

Method

A qualitative research design was employed in this study and incorporated interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) of the defining moment experiences of professional counselors (Smith, 2004; Smith & Osborn, 2008). The IPA approach was considered a suitable methodology to reveal the complex issues associated with the defining moment experiences of counseling professionals, as it enables a rich level of data collection and interpretation by studying people ideographically (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012). Semi-structured interviews were employed to collect data by providing participants the opportunity to discuss their defining moment experiences and give voice to their thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes formed as a result of the experience.

Research Team

The research team consisted of the first author, a research assistant, and an external auditor. None of the research team were in a dependent relationship or received monetary compensation for their work, and only the first author was significantly connected to the topic of defining moment experiences. The first author and principal investigator (PI) holds a doctorate in counselor education and supervision and is a licensed professional counselor with over 20 years’ experience. The external auditor is a doctorate-level clinician with over 20 years’ experience, significant knowledge of IPA methods, and no vested interest in the study. The research assistant (RA) is a retired English professor who has familiarity with and understanding of qualitative data analysis. The RA was intentionally selected to provide independent data analysis, as she had no counseling background.

Participants

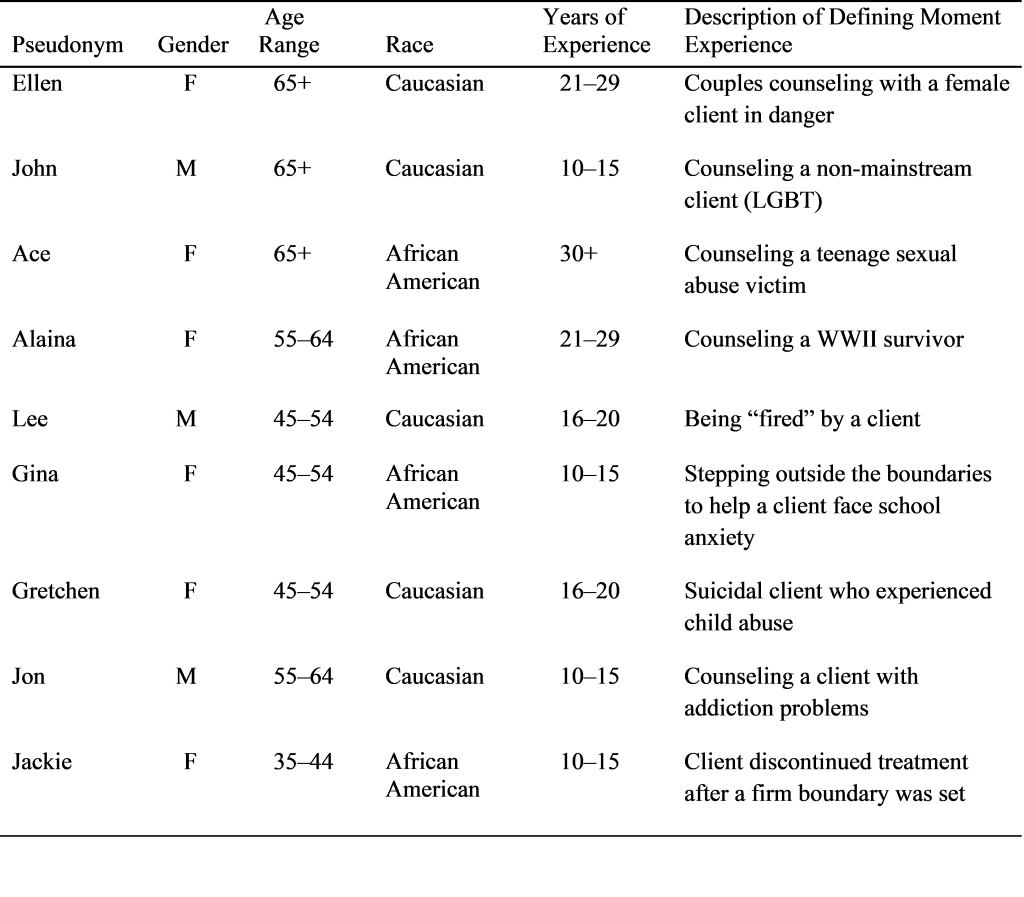

The study consisted of a purposive sample of nine experienced professional counselors who met the following inclusion criteria: (a) have a minimum of 10 years’ professional counseling experience, (b) be an active licensed professional counselor, and (c) experienced a defining moment in the role of counselor and expressed willingness to share related thoughts, feelings, and attitudes. Participant demographics are displayed in Table 1 with respect to the pseudonym each counselor selected for the study, along with a description of their defining moment experience and their varied backgrounds in terms of gender, age, race, experience, and the nature of their reported defining moment experiences.

Procedure

University IRB approval to conduct the study was received. An invitation to participate in a semi-structured interview on the defining moment experiences of professional counselors was advertised on the state therapist listserv as well as other established mental health agencies and professional counseling listservs limited to the southeast region of the United States. Participants also were recruited via the snowball method by initial contacts for referrals or recommendations for potential interview subjects.

Participants received a paper copy of the informed consent for review and signature prior to the start of each scheduled interview wherein participants were provided with a definition of defining moment experiences. Each participant chose a pseudonym in order to maintain confidentiality and, in accordance with Standard G.2.f. of the American Counseling Association (ACA) Code of Ethics (2014), the location, time, and format (by phone or in-person) of the interview honored each participant’s schedule and preferences. Moreover, interviews were conducted in a private space to maintain confidentiality and be free from distractions. Each interview was audio-recorded using a digital voice recorder and lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Two interviews were conducted in person, and seven interviews were conducted over the telephone.

Prior to their interview, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire. Each interview consisted of 12 open-ended questions (see Table 2), with the five main questions being: (1) Tell me about a defining moment that occurred while working with a client(s). (2) How did this experience shape how you saw yourself as a professional counselor? (3) How did this experience shape your sense of clinical competency? (4) How did you regard the therapeutic relationship between client and counselor prior to your defining moment experience? (5) As you reflect on your defining moment experience, how has your perspective changed or not changed? Sub-questions also were asked to illicit the meaning and sense attributed to defining moment experiences. Each interview question was presented in the same order with each participant for consistency (Creswell, 2007). Follow-up impromptu questions were asked in between the established questions to obtain richer, more elaborate details or context, as needed. Each interview progressed at a pace that was set by the participant, allowing for the development of more elaborate data with each question (Hays & Singh, 2012).

Table 1

Participant Demographics and Defining Moment Experience

A range of procedural steps were taken to enhance the credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability of the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and to counter any potential researcher biases (Morrow, 2005). To establish the credibility of the findings, descriptive field notes were taken during interviews to document observations and add context to the audio data. The field notes emphasized participant content, expressed meaning and PI observations (Creswell, 2007), and provided a means to confirm interpretations of interview data through data triangulation (Anney, 2014). Member checking was used to enhance the credibility of the findings (see Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2005) by asking participants to check summaries of the interview content. Confirmability of findings entailed the use of analytic memos and a reflexivity journal to ensure objectivity in any interpretations made in the course of data analysis (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009). Analytic memos were written throughout data analysis to record thoughts about the meaning behind participants’ words (Saldaña, 2009). A reflexivity journal was employed to assist the PI with preparing to interview each participant and enter their subjective reality by writing about her own defining moment experiences as a counselor prior to interviews (Hays & Singh, 2012). Moreover, the PI maintained the reflexivity journal throughout the interviews and data analysis processes. The PI made a consistent effort to bracket assumptions and biases to not superimpose her own experiences or subjective interpretations as a professional counselor (Smith, 2004; Smith & Osborn, 2008). The transferability of research findings was met by purposive sampling of participants based on their capacity to provide relevant knowledge on defining moment experiences (Anney, 2014). The criteria of ensuring dependability was met by employing the Dedoose qualitative research software program (Moylan, Derr, & Lindhorst, 2015) to independently organize, archive, and code interview data and field notes, as well as validate codes and themes derived from interview data (Silver & Lewins, 2014). The dependability of the data was enhanced by having the external auditor confirm the accuracy of (1) interview transcripts, (2) descriptive field notes, (3) the reflexive journal, (4) the theme codebook, and (5) Dedoose summaries and output.

Table 2

Interview Questions for the Study

| Question No. | Question content |

| 1 | Tell me about a defining moment that occurred while working with a client(s). This moment could have occurred in the early stages of counselor training or at a later time in your work as a counselor. |

| 1a | • What made it a defining moment? |

| 1b | • Do you have a takeaway from this moment? |

| 1c | • Is there anything else you would like to share about this experience? |

| 2 | How did this experience shape how you saw yourself as a professional counselor? As a person? |

| 2a | • What did this experience mean to you as a counselor? |

| 2b | • What did this experience mean to you on a personal level? |

| 2c | • What assisted you with making sense out of this experience? |

| 3 | How did this experience shape your sense of clinical competency? |

| 3a | • What strengths did you become aware of? |

| 3b | • What weaknesses or limitations did you become aware of? |

| 4 | How did you regard the therapeutic relationship between client and counselor prior to your defining moment experience? |

| 4a | • How did your understanding of the therapeutic relationship change or not change after the defining moment experience? |

| 4b | • How would you describe the therapeutic relationship between client and counselor as if you were describing this to a layperson/non-clinician? |

| 5 | As you reflect on your defining moment experience, how has your perspective changed or not changed? |

| 5a | • How did you make sense of the experience then? |

| 5b | • How do you make sense of the experience now? |

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed a 3-stage process as outlined by Pietkiewicz and Smith (2012): immersion, transformation, and connection. The immersion process began with the PI listening to each interview after its conclusion in order to review the content and record any additional observations in the field notes (Smith & Osborn, 2008). Each interview was transcribed by an independent contractor and the PI reviewed each along with the digital recording to ensure accuracy and facilitate deeper immersion in the data (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012). The PI read the participant’s responses along with the recording during the review process to foster deeper immersion and understanding of the experience being shared (Bailey, 2008). The PI documented new observations and insights throughout the immersion process in field notes and via a reflexivity journal (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012). The RA also independently engaged in the immersion, transformation, and connection stages with the interview transcripts.

The PI and the RA worked together to review and interpret all their notes about the transcripts and transform them into emergent themes consistent with IPA methodology (Smith & Osborn, 2008). Emergent themes were then connected together according to conceptual similarities to develop a thematic hierarchy (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2012). The final stage of analysis entailed a narrative account of each theme, including direct passages from the interviews. The PI and the RA also discussed and compared several levels of interpretation of interview content and of interpreted meanings to reach agreement on the final set of distinct themes. Moreover, the transcripts, notes, and themes were submitted to the external auditor, who conducted an independent cross-analysis to ensure their accuracy and clarity.

Results

Data analysis with IPA methods resulted in five themes being identified and labeled based on the meanings associated with professional counselors’ defining moment experiences (see Table 3). The first theme was labeled acceptance of reality and captures how defining moment experiences led professional counselors to the realization that counselors are not always a good match for a client and cannot fully resolve any clinical problem that comes their way. The second theme, finding a balance, addresses how defining moment experiences shaped perceptions of clinical boundaries and the balance between strengths and limitations and external and internal forces. The third theme to be derived from the analysis, enhanced self-reflection and awareness, captures professional counselors’ understanding that defining moment experiences facilitated their own reflection and questioning of their intrapersonal and interpersonal processes. The fourth theme, reciprocal transformation, illustrates how the experiences shaped professional counselors’ understanding of the therapeutic relationship and acted as a mutual change agent for both counselor and client. Lastly, the fifth theme, assimilation and integration, encapsulates how meanings attached to defining moment experiences changed and were incorporated over time.

Table 3

IPA Coding Scheme of the Meaning of Defining Moment Experiences of Professional Counselors

| Theme | Description |

| Acceptance of reality | Coming to terms with the realistic, sometimes limiting, aspects of the counselor role |

| Finding a balance | Perceptions of clinical boundaries and the balance between strengths and limitations and external and internal forces |

| Enhanced self-reflection and awareness | Facilitated reflection and questioning of intrapersonal and interpersonal processes |

| Reciprocal transformation | Mutual change agent for both counselor and client |

| Assimilation and integration | How meanings attached to defining moment experiences changed and were incorporated over time |

Theme 1: Acceptance of Reality

Experienced counselors made meaning of their defining moment experiences in the theme of acceptance of reality. This theme was derived to reflect participants’ thoughts about how their defining moment experience helped them come to terms with the realistic, sometimes limiting, aspects of the counselor role. Specifically, defining moment experiences were understood by counselors to help dispel the myth that counselors are a good match for any client and can “fix” and fully resolve any clinical problem that comes their way. According to Ellen, “some situations are beyond repair. If people wait too long to come to see us, we can’t help, and they can’t even make any changes for themselves.” For Jackie, the defining moment experience meant being comfortable with accepting the reality of the limiting aspects of the counselor role when a client didn’t want to change and wanted Jackie to do all the work. She reflected: “In that moment, I just remembered saying . . . you can’t help everybody. It just means I’m not a good fit (for everybody) and that’s okay.” Similarly, the defining moment experience of Alaina meant accepting the reality that “a client I cannot love is not right for me . . . I don’t agree celebrating [the fact of] working with someone you don’t have a connection with.” It also would appear from these defining moment reflections that the acceptance of reality was associated with deeper knowledge of counselor–client boundary conditions. Indeed, counselor–client boundary issues were a significant factor in the defining moments theme of finding a balance.

Theme 2: Finding a Balance

The theme of finding a balance was identified in participants’ understanding of their defining moment experiences as highlighting different therapeutic boundary conditions and balancing the fine line between internal or external limitations while gaining a sense of finesse and agility between opposing forces. Here, participants identified a dual connection between strengths and limitations, while expressing accountability for establishing a balance between the two factors for client benefit. By taking ownership of a specific personality trait as part of the defining moment experience, Lee came to understand the importance of balance and the potential for possible pitfalls if such a balance is not obtained: “It was my personal disposition to speak with conviction, which is both a strength and limitation. I am still this way of course, but I know when to scale it back—to strike that balance.”

Finding a balance through defining moment experiences was evident in participants sharing their experiences of entering uncharted or unfamiliar territories with some trepidation, only to find their own rhythm through setting boundaries. Alaina shared: “I understood I was really flying by the seat of my pants and the only thing I had that I really understood were my boundaries. It made my boundaries even stronger. They were very heart-wrenching limitations; it was very hard.” Moreover, Ellen conveyed how the defining moment experience highlighted the process of balancing between her own feelings of physical vulnerability and her inner strengths when she was working with a couple in an abusive relationship: “I needed to sit alone with him to keep her safe. It was like walking into the lion’s den; however, my use of self-intuition [and] wisdom was a strength. I was just going to tap dance with him when I saw him.”

Theme 3: Enhanced Self-Reflection and Awareness

Professional counselors understood their defining moment experiences as ones that especially facilitated self-reflection and awareness of intrapersonal and interpersonal processes. At the intrapersonal level, John highlighted how the defining moment experience “increased my awareness and clarity of my own internal processes.” At the interpersonal level, Lee shared: “I made a connection in my personal relationships where I’ve learned to create space for others.” The theme of self-reflection also was manifest in the level of self-questioning prompted by the defining moment experiences of professional counselors. Indeed, Jackie discussed how her defining moment experience led to “a lot of reflection; I started to question my passion and why I wanted to be a therapist.” Similarly, Gina reflected that “I was puzzled and confused; lots of self-doubt [and] reflection. I remember where I would question whether I was a good therapist.” Importantly, the self-reflection and awareness prompted by the defining moment experiences of professional counselors appeared to have confirmed their professional capacities, with Gretchen sharing: “I received affirmation of what I thought I knew—what my gut was telling me.”

Theme 4: Reciprocal Transformation

Professional counselors understood their defining moment experiences as entailing the theme of reciprocal transformation through shared vulnerability and trust. This theme was derived from counselors speaking to their awareness of the dynamic of change within the therapeutic relationship; defining moment experiences generated a broader understanding of the transformative power within the therapeutic bond. For example, Lee shared: “You know, it’s a two-way conversation. This guy came back, taught me a great lesson: just how sacred and fragile the bond can be. I think we both changed after that experience.” Reciprocal transformation was reflected in participants discussing how defining moment experiences were associated with shared feelings of vulnerability and healing. As stated by Ellen, “We work with vulnerable people and if we just pretend we’re not there’s no authentic connection. The relationship is the primary vehicle for healing. Vulnerability is a good thing as a therapist.”

Jackie discussed how her defining moment experience highlighted the importance of disclosure in transforming the therapeutic relationship into one of mutual trust: “You are both engaging in some sense of disclosure and that helps people to build trust. It’s ever-growing, it’s always changing. The relationship can change and grow as the two of you grow and change.” In a similar way, Jon’s understanding of his defining moment experience highlighted the importance of taking risks to transform the therapeutic relationship: “You are risking the possibility that something will happen so then emotionally they won’t go on with you. You need to be willing to clear the air and move forward. I think that’s the place where the relationship deepens.”

Theme 5: Assimilation and Integration

The final theme, assimilation and integration, represents the difference in meaning between how the defining moment experience was initially assimilated by professional counselors and how meanings gleaned from the experience continue to be integrated. Participants discussed the non-static nature of the meanings attached to their defining moment experiences. The meanings continue to be assimilated with time and experience and remain an integral part of their ongoing counselor development. For example, Jackie stated: “I needed to grow as a therapist. Now, I look at the experience differently. It really has evolved into knowing my limitations [and] my strengths.” For Alaina, “the meanings acquired more textures, they got better and continue with me today.” Similarly, Lee used the metaphor of winding a ball of yarn to explain the meaning associated with integrating her defining moment experience over time: “Then, it taught me more about the client. Now, it informs me more. It’s like a ball of yarn. As I acquired experience, there was more yarn to wind. It now informs me how to be with all clients.”

For John, processing the defining moment experience meant he went from a place of anxiety to becoming aware of the spiritual nature of counseling: “At first, the experience relieved some anxiety about whether I was able to do this work. What I appreciate now, that I was too anxious to be aware of at the time, is that this is spiritual work.” Finally, Ace integrated her defining experience of working with a victim of teenage sexual abuse by now conducting advocacy work: “What assisted me with making sense out of my experience was volunteering for child abuse agencies, serving on a board, [and] being an advocate.” Overall, each participant constructed meaningful interpretations of their defining moment experiences that continue to inform their work and passion as counseling professionals, whether as a source of inspiration or affirmation.

Discussion

From novice to seasoned professionals, challenges occur within the therapeutic relationship that can provide growth opportunities to counseling practitioners to develop their clinical attributes (Orlinsky & Rønnestad, 2005; Skovholt & Rønnestad, 2003). The findings from this study support and extend the idea that defining moment experiences represent one such challenge. Professional counselors in this study understood their defining moment experiences as growth opportunities associated with different meanings to their professional practice and clinical skills. The meanings of the defining moment experiences of professional counselors were interpreted to reflect five main themes relevant to counseling practice: acceptance of reality, finding a balance, enhanced self-reflection and awareness, reciprocal transformation, and assimilation and integration.

Professional counselors understood their defining moment experience as one that was a wake-up call to accept the reality that counselors are not ideal for all clients and all presenting problems. This finding supports theory and research that an idealistic and glamorized view of counseling is often a source of stress among developing counselors (Moss et al., 2014; Skovholt & Rønnestad, 2003), wherein supervisors play an important role in guiding novice counselors toward the realistic position that it is not always possible to have a positive impact with clients. Indeed, the findings of this study provide distinct evidence that defining moment experiences of professional counselors bring them to a point in their career when they come to accept that the counselor role may produce limited success with certain clients on different occasions. As suggested by Skovholt and Rønnestad (2003) and the findings of this study, acceptance of reality is paradoxical in a helping profession like counseling; growth as a counselor occurs with the realization that some people and problems cannot be helped. This change of view also meant that the acceptance of reality was associated with deeper knowledge of counselor–client boundary conditions.

The meanings of professional counselors’ defining moment experiences were reflected in the specific theme of finding a balance in terms of participants navigating the boundaries between their strengths and limitations. Previous counselor development research (e.g., Furr & Carroll, 2003; Moss et al., 2014; Trotter-Mathison et al., 2010) has shown that establishing client–counselor boundaries is an important challenge to novice counselors, usually meant in terms of establishing emotional boundaries. To the counselors in this study, establishing such boundaries was about finding the right balance. Nevertheless, the meanings associated with the defining moment experiences of professional counselors extended beyond client–counselor boundaries to include balance between one’s own strengths and weaknesses, internal and external limitations, and finding a rhythm in uncharted or unfamiliar territories. It also was apparent that the participants’ ability for self-reflection and awareness was important for facilitating balance.

Experienced counselors also understood their defining moment experiences to entail enhanced self-reflection and awareness. Indeed, their willingness to self-reflect and take ownership for finding an optimal balance between strengths and limitations that were revealed through defining moment experiences has been clarified elsewhere as an important developmental step toward increased counseling competency (e.g., Skovholt & Rønnestad, 2003; Thériault & Gazzola, 2010; Williams, Hayes, & Fauth, 2008). As identified by Moss et al. (2014), continuous reflection is required for optimal learning. Defining moment experiences for professional counselors meant self-reflection even to the point of questioning their suitability for the profession. Indeed, the best counselors are generally viewed as questioning what they do and why (Kottler, 2017). It would appear from the findings that defining moment experiences appear to bring that level of self-questioning into focus.

The findings also revealed the change-agent quality of defining moment experiences wherein the experiences of counselors led to the development of a broader understanding of the reciprocal and transformative power within the therapeutic bond. In line with previous research (e.g., Orlinsky, Botermans, & Rønnestad, 2001; Skovholt & Rønnestad, 2003), the findings clarified that learning within the counselor–client relationship was a significant influence on career development among experienced counselors. Moreover, reciprocal transformation was reflected in professional counselors acknowledging shared vulnerability within the counselor–client relationship. Other research (e.g., Trotter-Mathison et al., 2010) has similarly found the most powerful defining moments occurred when counselors took risks or a leap of faith and allowed themselves to be vulnerable. Indeed, the defining moment experiences of the professional counselors in this study were reported as opportunities to experience the transformative power of shared vulnerability to establish new learning and growth in both counselor and client alike.

Within the theme of assimilation and integration, professional counselors shared how meanings of their defining moments continue to be a solid foundation of inspiration for their purpose, passion, and advocacy work in the counseling profession. Siegel (2007) referred to this process as the power of recall and repetition, whereby as counselors self-reflect on definitive experiences, the repetition of each memory forges deeper, more meaningful connections in the brain. Whether counselors engage in self-reflection in present time or as retrospection, the repetition of recall begins to move newly acquired data from state to trait, thus furthering the integration of new information or insights (Siegel, 2007). This view is supported in Prengel and Somerstein’s (2013) study of defining moment experiences, which highlights the process of self-reflection as one that requires time and re-examination in order to deepen lessons learned. In kind, the findings of this study suggest it is beneficial for counselors to engage in self-reflective practices throughout their professional life; the practice of self-reflection appears to have facilitated deeper integration of originally assimilated meanings of defining moment experiences by professional counselors. Consistent with the view of Engels, Barrio Minton, and Ray (2009), assimilation and integration of significant meanings appeared to have a positive effect on the competencies of professional counselors in this study.

Altogether, interpretive analysis of the defining moment experiences of professional counselors suggested a set of interrelated meanings and themes that appear to facilitate the development of counselor capacities. Defining moment experiences appear to bring into sharp focus an important transition in counselor thinking—acceptance of the realistic nature of counseling in terms of the sometimes lack of counselor–client-problem fit. In a related way, defining moment experiences of professional counselors facilitated deeper thinking about finding balance in professional practice. Professional counselors reported deeper thinking in the form of heightened self-reflection and self-awareness as meanings they associated with defining moment experiences. One may posit that heightened self-reflection and awareness mediates the relationship between defining moment experiences and acceptance of reality and finding balance in professional counseling. Defining moment experiences of professional counselors also held significant meaning because they highlighted the reciprocal and transformative power within the therapeutic bond and because the meanings continue to be integrated. As shared by Jackie, “This was a great opportunity to reflect on where I was and who I’ve become . . . all with the same lesson from my first client . . . that thread continues to inform me.”

Implications for Counselor Practice

The significance of defining moment experiences to professional counselors raises implications for professional practice and the counselor development process. As suggested by themes identified in the findings of this study, experienced professional counselors appeared to find defining moment experiences helped them accept counseling realities, find balance within the counselor role, and understand the transformative power within the therapeutic bond. At the same time, defining moment experiences facilitated heightened self-awareness, providing professional counselors an opportunity to attune to their own internal processes. As such, the meanings associated with defining moment experiences tie in with standards set forth by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (2015), which aligns professional competence with counselor self-awareness via self-reflection. Facilitating conversations and reflecting on defining moment experiences may provide a focal point for continuing training of professional counselors consistent with the mission of ACA (2019). The findings of this study underline the potential benefits of practicing and modeling self-reflection throughout the careers of professional counselors, supervisors, and counselor mentors to enhance their ongoing development and clinical expertise.

At the same time, counselor training programs may incorporate the meanings of defining moment experiences into their courses. Indeed, some participants in this study reported on a defining moment experience that occurred as a counselor trainee, and previous research has revealed practicum and novice counselors find great benefit from reflecting on defining experiences when they worked with a challenging client or issue (e.g., Bischoff et al., 2002; Furr & Carroll, 2003; Howard et al., 2006). Providers of counselor education programs and supervisors could develop awareness of the potential for defining moment experiences to raise questions about the realities of counseling, finding a balance in the counselor role, and the transformative power of the therapeutic relationship. This may be facilitated by encouraging novice counselors to employ self-reflection techniques such as journaling, which has been shown in previous research to benefit counselor development (e.g., Burnett & Meacham, 2002). Novice counselors could be asked to self-reflect on a defining moment experience via journaling as a part of their practicum and internship programs and use supervision sessions to connect the meaning and significance of the experience to the development of clinical skills and attributes. The findings of this study provide some insights on what type of meanings may be discussed in such sessions, including how defining moment experiences may relate to acceptance of counseling realities, finding a balance within the counselor role, and understanding the transformative power within the therapeutic bond.

Limitations and Future Research

There are limitations inherent in this study that require acknowledgement. The sample of participants might have invoked a self-selection bias wherein participants who elected to take part in the study may have been more inclined to value and reflect on their defining moment experiences than those who did not elect to participate. The use of semi-structured interviews, whether conducted in person or by phone, could have increased the likelihood of response inhibition (Bischoff et al., 2002). The interview participants could have answered interview questions according to perceived socially desirable responses rather than provide a more accurate and honest account of thoughts and feelings associated with their defining moment experiences. Steps to ensure confidentiality, such as the use of pseudonyms for participants, may have minimized response bias; however, to what degree is uncertain. In addition, the sample of participants was limited to professional counselors who worked in private practice with an expertise in trauma. A final limitation of the study is the potential for researcher subjectivity to influence data collection (interviews) and interpretive analysis (thematic coding). Nevertheless, appropriate methodological steps were taken in this study, such as a reflexivity journal and independent coders, to enhance the objectivity and trustworthiness of the data collection and interpretation procedures and outcomes.

The research findings provide directions for future research on defining moment experiences of professional counselors. To date, there is very little empirical research on defining moment experiences and their significance to professional counselors. Whereas this study provides a unique contribution to the counselor literature, future research may broaden the sample criteria to include not only experienced professionals in other regions of the United States and in other countries, but also licensed clinical social workers, licensed marriage and family therapists, and clinical psychologists. Research with a range of professionals would broaden knowledge about the significance of defining moment experiences to their ongoing professional practice. Moreover, research that broadens the focus on counselors to include an investigation of the role of supervisors in defining moment experiences would be worthwhile. Finally, research may follow up on the revelation from two participants in this study that defining moment experiences led them to question their suitability for the counseling profession. Research on the defining moment experiences of individuals who chose to leave the field may shed light upon the goodness-of-counselor-fit within the counseling profession.

Conclusion

In conclusion, findings from this study support and contribute to the professional counseling literature by revealing the meanings associated with the defining moment experiences of professional counselors. Consistent with models of counselor development (e.g., Moss et al., 2014), experienced counselors showed a comparatively strong capacity to deeply reflect and process the latent meanings and implications of defining moment experiences for their ongoing professional growth and development. Defining moment experiences appear to help professional counselors accept the realities of counseling, find a balance within the counselor role, and understand the transformative power within the therapeutic bond. The findings contribute to existing literature by illustrating how meaningful interpretations of defining moment experiences continue to deepen over time and enhance counselor practice, especially when opportunities are taken for self-reflection. Application of knowledge on the significance, meaning, and implications of defining moment experiences in counselor training programs and supervision sessions provides an opportunity for enhancing the clinical attributes of professional counselors.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). Code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

American Counseling Association. (2019). Continuing education. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org /continuing-education

Anney, V. N. (2014). Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 5, 272–281.

Bailey, J. (2008). First steps in qualitative data analysis: Transcribing. Family Practice, 25(2), 127–131. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmn003

Bischoff, R. J., Barton, M., Thober, J., & Hawley, R. (2002). Events and experiences impacting the development of clinical self confidence: A study of the first year of clinical contact. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28, 371–382. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2002.tb01193.x

Burnett, P. C., & Meacham, D. (2002). Learning journals as a counseling strategy. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80, 410–415. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00207.x

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. Retrieved from https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design. London, UK: SAGE.

Kottler, J. A. (2017). On being a therapist (5th ed). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Moss, J. M., Gibson, D. M., & Dollarhide, C. T. (2014). Professional identity development: A grounded theory of transformational tasks of counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92, 3–12.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2003.tb00275.x

Moylan, C. A., Derr, A. S., & Lindhorst, T. (2015). Increasingly mobile: How new technologies can enhance qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 14, 36–47. doi:10.1177/1473325013516988

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2005). On becoming a pragmatic researcher: The importance of combining quantitative and qualitative research methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 375–387. doi:10.1080/13645570500402447

Orlinsky, D. E., Botermans, J.-F., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2001). Towards an empirically grounded model of psychotherapy training: Four thousand therapists rate influences on their development. Australian Psychologist, 36(2), 139–148. doi:10.1080/00050060108259646

Orlinsky, D. E., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2005). How psychotherapists develop: A study of therapeutic work and professional growth. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Patterson, C. A., & Levitt, D. H. (2011). Student counselor development during the first year: A qualitative study. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 3(2), 6–19.

Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2012). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czasopismo Psychologiczne Psychological Journal, 18, 361–369. doi:10.14691/CPPJ.20.1.7

Prengel, S., & Somerstein, L. (2013). Defining moments for therapists. New York, NY: LifeSherpa.

Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovholt, T. M. (2003). The journey of the counselor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives in professional development. Journal of Career Development, 30, 5–44. doi:10.1177/089484530303000102

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (1st ed.). London, UK: SAGE.

Siegel, D. J. (2007). Mindfulness training and neural integration: Differentiation of distinct streams of awareness and the cultivation of well-being. Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience, 2, 259–263. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm034

Silver, C., & Lewins, A. (2014). Using software in qualitative research (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Skovholt, T. M. (2012). Becoming a therapist: On the path to mastery. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons.

Skovholt, T. M., & McCarthy, P. R. (1988). Critical incidents: Catalysts for counselor development. Journal of Counseling & Development, 67(2), 69–72. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1988.tb02016.x

Skovholt, T. M., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2003). Struggles of the novice counselor and therapist. Journal of Career Development, 30, 45–58. doi:10.1023/A:1025125624919

Smith, J. A. (2004). Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1, 39–54. doi:10.1191/1478088704qp004oa

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London, UK: SAGE.

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 53–80). London, UK: SAGE.

Thériault, A., & Gazzola, N. (2010). Therapist feelings of incompetence and suboptimal processes in psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40, 233–243. doi:10.1007/s10879-010-9147-z

Trotter-Mathison, M., Koch, J. M., Sanger, S., & Skovholt, T. M. (2010). Voices from the field: Defining moments in therapist and counselor development. New York, NY: Routledge.

Veach, P. M., & LeRoy, B. S. (2012). Defining moments in genetic counselor professional development: One decade later. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 21, 162–166. doi:10.1007/s10897-011-9427-0

Williams, E. N., Hayes, J. A., & Fauth, J. (2008). Therapist self-awareness: Interdisciplinary connections and future directions. In S. D. Brown & B. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (4th ed., pp. 303–319). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Zahm, K. W., Veach, P. M., Martyr, M. A., & LeRoy, B. S. (2016). From novice to seasoned practitioner: A qualitative investigation of genetic counselor professional development. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 25, 818–834. doi:10.1007/s10897-015-9900-2

Diane M. Coll is a professional counselor at Argosy University. Chandra F. Johnson is an associate professor at Argosy University. Chinwé U. Williams is an associate professor at Argosy University. Michael J. Halloran is an honorary associate professor at La Trobe University. Correspondence can be addressed to Michael Halloran, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Kingsbury Dr., Bundoora, Australia, 3086, m.halloran@latrobe.edu.au.