Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Wesley B. Webber, W. Leigh Atherton, Kelli S. Russell, Hilary J. Flint, Stephen J. Leierer

The COVID-19 pandemic and efforts to manage it have affected mental health around the world. Although early research on the COVID-19 pandemic showed a general decline in mental health after the pandemic began, mental health in later stages of the pandemic might be improving alongside other changes (e.g., availability of vaccines, return to in-person activities). The present study utilized data from a mental health service intervention for individuals at a southeastern university who were exposed to COVID-19 following the university’s return to in-person operations. This study tested whether time period (August–September 2021 vs. January–February 2022) predicted individuals’ likelihood of being mild or above in depression and anxiety ratings. Results showed that individuals were more likely to be mild or above in both depression and anxiety ratings during August–September of 2021 than January–February of 2022. Suggestions for future research and implications for professional counselors are discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, depression, anxiety, university

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19), first detected in 2019, spread globally at a rapid pace, with the first confirmed case in the United States occurring on January 20, 2020, in the state of Washington (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023). By April 2020, the United States had the most reported deaths in the world due to COVID-19. It was not until December of 2020 that the first round of vaccines, authorized under emergency use authorization, was made available (Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2021). As of October 2022 in the United States, a total of 97,063,357 cases of COVID-19 had been reported, from which there were 1,065,152 COVID-19–related deaths (CDC, 2023). A reported 111,367,843 individuals aged 5 and above in the United States had received their first booster dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of October 2022 (CDC, 2023). Previous research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic and efforts to manage it (e.g., lockdowns, quarantine, isolation) had negative effects on mental health in the United States and internationally (Huckins et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020; Son et al., 2020). Based on the extended duration of the pandemic and changes that have occurred during it (e.g., vaccine availability, lessening of initial social restrictions), more recent research has investigated possible changes in mental health in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fioravanti et al., 2022; McLeish et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). The present study adds to this literature by exploring whether psychosocial symptomatology (i.e., depression and anxiety) at a university in the Southeastern United States differed in individuals exposed to COVID-19 during August–September 2021 as compared to individuals exposed to COVID-19 during January–February 2022 (following the university’s return to on-campus operations in August 2021).

Challenges to Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, conceptual and empirical research has focused on ways in which the pandemic and associated stressors might impact mental health (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2020; Marroquín et al., 2020; Şimşir et al., 2022). Implementation of lockdowns to deter spread of the virus led to concerns that social isolation might have severe impacts on mental health (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2020). This hypothesis was empirically supported, as stay-at-home orders and individuals’ reported levels of social distancing were positively associated with depression and anxiety (Marroquín et al., 2020). Individuals’ views on the COVID-19 pandemic evolved quickly at the outset of the pandemic, and perceptions of risk were shown to increase during the pandemic’s first week in the United States (Wise et al., 2020). Growing awareness of the dangers of the virus likely had deleterious effects on mental health; Şimşir et al. (2022) found through a meta-analysis that fear of COVID-19 was associated with a variety of mental health problems. Mental health was also negatively affected by stigmatization associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, as was the case for those exposed to COVID-19 while at their place of work (Schubert et al., 2021). Such stigmatization associated with COVID-19 exposure was found to increase risk for depression and anxiety (Schubert et al., 2021).

The lockdowns and social distancing measures that accompanied early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic also resulted in changes to routines that likely impacted mental health. For some individuals facing lockdowns or other disruptions to typical routines, reductions in physical activity occurred. Individuals who reported greater impact of COVID-19 on their level of physical activity showed greater symptoms of depression and anxiety (Silva et al., 2022). Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, based on people’s increased time spent at home and their concerns about COVID-19 developments, some people increased their media usage (e.g., news outlets, social media). Such increases in media usage were associated with decreases in mental health (Meyer et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic had less significant impact on mental health for those with greater tolerance of uncertainty (Rettie & Daniels, 2021) and psychological flexibility (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020). Thus, some individuals were uniquely suited to face the many changes and stressors brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

One population that previous research has identified as being especially at risk for negative mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic is college students (Xiong et al., 2020). For college students, the COVID-19 pandemic occurred alongside other stressors known to be typical for this population such as adjusting to leaving home, navigating new peer groups, and making career decisions (Beiter et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019). Thus, for many college students, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted a period of life already filled with many transitions. For example, shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic began, many college students were forced to leave their dormitories and peers as universities transitioned to online delivery of classes (Copeland et al., 2021). Xiong et al. (2020) found through a systematic review that college students were especially vulnerable to negative mental health outcomes at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to others in the general population. In the United States, college students’ reported degree of life disruption due to the COVID-19 pandemic was positively associated with depression at the conclusion of the spring 2020 semester (Stamatis et al., 2022). During fall 2020, COVID-19 concerns and previous COVID-19 infection were each found to be associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety among U.S. college students (Oh et al., 2021). Overall, previous research has supported the notion that changes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic had general negative effects on mental health in the general population and in college students specifically.

Changes in Psychosocial Symptomatology Across the COVID-19 Pandemic

Although research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic introduced unprecedented challenges and stressors that were associated with mental health problems, another important direction for research has been to characterize overall changes in psychosocial symptomatology as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed. Such research is important given that individuals might psychologically adapt to constant COVID-19 stressors or might benefit from changes that have occurred as the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed (e.g., vaccine availability, lessening of societal restrictions). Initial longitudinal studies comparing individuals’ symptomatology before the COVID-19 pandemic and after its beginning showed that mental health deteriorated after the COVID-19 pandemic began (Elmer et al., 2020; Huckins et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020). Prati and Mancini (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of 28 studies that used longitudinal or natural experimental designs and found that depression and anxiety showed small but statistically significant increases after implementation of the initial lockdowns in response to COVID-19. The various changes to ways of life associated with the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to result in a general deterioration in mental health.

Previous research has also explored possible changes in mental health beyond those that were observed in the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. In support of the notion that individuals adapted to changes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, Fancourt et al. (2021) found that anxiety and depression decreased across the initial lockdown period in the United Kingdom. In contrast, Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. (2020) found that levels of depression and anxiety were higher 3 weeks into the initial lockdown period in Spain as compared to the beginning of the lockdown. Fioravanti et al. (2022) assessed psychological symptoms longitudinally in an Italian sample at three time points—the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and first lockdown (March 2020), the end of the first lockdown phase (May 2020), and during a second wave of COVID-19 with increased societal restrictions (November 2020). Their findings pointed to possible influences of COVID-19 waves and societal restrictions on specific psychosocial symptoms. Specifically, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder all decreased at the end of the first lockdown phase (Fioravanti et al., 2022). However, all symptoms besides obsessive-compulsive disorder significantly increased from the end of the first lockdown phase to the second wave of COVID-19 (Fioravanti et al., 2022).

Recent research on mental health among college students in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic has also focused on possible mental health changes over time (McLeish et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). Tang et al. (2022) reported reductions in anxiety and depression in a longitudinal study of university students in the United Kingdom between a first time point (July–September 2020, after the end of lockdown) and a second time point (January–March 2021, when vaccinations were becoming available). In contrast, McLeish et al. (2022) found through a repeated cross-sectional study that depression and anxiety among students at a specific university increased from spring 2020 to fall 2020, with the increases being maintained in spring 2021. The authors noted that vaccines were not widely available at the university until the end of spring 2021 (McLeish et al., 2022). Thus, recent studies have found mixed results as to whether psychosocial symptomatology improved over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. These discrepancies may be due to contextual differences between studies (e.g., differences in data collection time periods, availability of vaccines, or levels of COVID-19 restrictions being implemented during data collection).

The Present Study

The present study was conducted based on the need for continued research on mental health across the evolving COVID-19 pandemic and based on previous conflicting findings on possible mental health changes in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given previous research showing detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population and in college students, the present study utilized data from a university population. Specifically, an archival dataset was used in the present study to examine data collected during 2021–2022 at a university in the Southeastern United States and to test whether time period would predict severity of depression and anxiety symptoms. Individuals in the study had been exposed to COVID-19 between August–September 2021 or between January–February 2022 and had requested a mental health contact during university-conducted contact tracing. These two time periods corresponded to surges in COVID-19 cases at the university due to the delta and omicron COVID-19 variants, respectively. August–September 2021 also coincided with a return to on-campus operations at the university and therefore captured psychosocial symptomatology at the beginning of a significant transition in the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., a return to organized in-person activities on a college campus during the evolving pandemic). This study was designed to answer the following research questions:

- Among those requesting mental health contact after COVID-19 exposure, was the likelihood of having at least mild depression symptoms different for those whose contact occurred between August–September 2021 as compared to those whose contact occurred between January–February 2022?

- Among those requesting mental health contact after COVID-19 exposure, was the likelihood of having at least mild anxiety symptoms different for those whose contact occurred between August–September 2021 as compared to those whose contact occurred between January–February 2022?

Method

Design

A retrospective research design was used to analyze the possible effect of time period on severity of depression and anxiety symptoms among members of a university population who had been exposed to COVID-19 and requested a mental health check-in. The study used a de-identified dataset obtained from the service providers who completed the mental health check-in. We confirmed through consultation with the IRB that the use of archival, de-identified data does not necessitate IRB review.

COVID-19 Mental Health Check-In Dataset

The archival, de-identified dataset used in the present study was compiled as part of a mental health service occurring between February 2021 and February 2022. Participants in the dataset had tested positive for COVID-19 or been exposed to COVID-19 without a positive test. During university-conducted contact tracing, they were offered and elected to receive a subsequent mental health check-in. Individuals who were contact traced and thereby offered a mental health check-in had become known to contact tracers through one of two routes: (a) they reported their own COVID-19 diagnosis or exposure through a self-reporting mechanism as instructed by the university, or (b) they were reported by another individual as having been diagnosed with or exposed to COVID-19. The dataset used in this study included data collected during the mental health check-ins for those who elected to receive them. This data was collected over the phone and documented in RedCap (a secure web browser–based survey protocol designed for clinical research) at the time of the phone call or within 24 hours. The dataset consisted of data for 211 individuals’ check-ins. For each check-in, the dataset included participants’ demographic information, screening data (for depression, anxiety, and trauma), identified needs of the participant, resources shared with the participant, and the date of data entry.

The present study focused on check-in data for all individuals from the COVID-19 Mental Health Check-in Dataset whose check-in had occurred during one of the two time periods of focus—August–September 2021 or January–February 2022. These two time periods corresponded to surges in COVID-19 cases at the university associated with the delta and omicron COVID-19 variants, respectively. The 149 individuals who checked in during these 4 months represented 70.62% of the total number of check-ins over the 12-month dataset (N = 211), reflecting the surges in COVID-19 cases during these two periods. Of the 149 individuals in the present study, 96 (64.43%) received their check-in during August–September 2021, and 53 (35.57%) received their check-in during January–February 2022. The selection of these two time periods from the larger dataset allowed for comparison of psychosocial symptomatology during comparable levels of COVID-19 infection (i.e., surges associated with two subsequent COVID-19 variants) at comparable points in subsequent academic semesters (i.e., the first 2 months of the fall 2021 and spring 2022 semesters). The present study used only the screening data for depression and anxiety, as the scales for each of these constructs showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > .80).

Participants

The sample in the present study consisted of 149 individuals. The selected individuals’ ages ranged from 17 to 52 (M = 22.21, SD = 7.43). With regard to gender, 67.11% identified as female, 32.21% as male, and 0.67% as non-binary. The reported races of individuals in the study were as follows: 60.4% White, 20.13% African American, 6.71% Hispanic, 3.36% Other, 2.68% Two or more races, 1.34% Middle Eastern, 1.34% Native American, and 0.67% Asian. Some participants preferred not to indicate their race (3.36%). In responding to a question about their ethnicity, 87.25% of individuals identified as not Latinx, 9.40% identified as Latinx, and 3.36% preferred not to answer. With regard to academic level/job title, 32.89% were freshmen, 20.13% were sophomores, 14.09% were juniors, 15.44% were seniors, 7.38% were graduate students, 8.05% were faculty/staff, and 2.01% preferred not to answer. Regarding employment, 53.69% were not employed (including students), 30.20% were employed part-time, 12.75% were employed full-time, and 3.36% preferred not to answer. The relationship statuses of individuals were reported as the following: 87.92% single (never married), 4.7% married, 2.01% single but cohabitating with a significant other, 1.34% in a domestic partnership or civil union, 1.34% separated, 0.67% divorced, and 2.01% preferred not to answer. Table 1 summarizes demographic responses within each of the two time periods and for the full sample.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants responded to seven demographic questions (age, gender, race, ethnicity, academic year/job title, current employment status, and relationship status). They were informed that this information was optional and that they could choose not to answer particular questions.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

|

Demographic

Characteristic |

|

| August–September 2021 |

January–February 2022 |

Full Sample |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

69 |

71.88 |

31 |

58.49 |

100 |

67.11 |

| Male |

27 |

28.13 |

21 |

39.62 |

48 |

32.21 |

| Non-binary |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.89 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| White |

56 |

58.33 |

34 |

64.15 |

90 |

60.40 |

| African American |

23 |

23.96 |

7 |

13.21 |

30 |

20.13 |

| Hispanic |

8 |

8.33 |

2 |

3.77 |

10 |

6.71 |

| Other race |

1 |

1.04 |

4 |

7.55 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Two or more races |

4 |

4.17 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

2.68 |

| Middle Eastern |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Native American |

1 |

1.04 |

1 |

1.89 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Asian |

1 |

1.04 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

5 |

9.43 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not Latinx |

82 |

85.42 |

48 |

90.57 |

130 |

87.25 |

| Latinx |

12 |

12.50 |

2 |

3.77 |

14 |

9.40 |

| Prefer not to answer |

2 |

2.08 |

3 |

5.66 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Academic Year / Job Title |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Freshman |

38 |

39.58 |

11 |

20.75 |

49 |

32.89 |

| Sophomore |

18 |

18.75 |

12 |

22.64 |

30 |

20.13 |

| Junior |

15 |

15.63 |

6 |

11.32 |

21 |

14.09 |

| Senior |

15 |

15.63 |

8 |

15.09 |

23 |

15.44 |

| Graduate Student |

6 |

6.25 |

5 |

9.43 |

11 |

7.38 |

| Faculty/Staff |

4 |

4.17 |

8 |

15.09 |

12 |

8.05 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5.66 |

3 |

2.01 |

| Employment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not Employed (including student) |

62 |

64.58 |

18 |

33.96 |

80 |

53.69 |

| Employed Part-Time |

26 |

27.08 |

19 |

35.85 |

45 |

30.20 |

| Employed Full-Time |

8 |

8.33 |

11 |

20.75 |

19 |

12.75 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

5 |

9.43 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Relationship Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single, never married |

87 |

90.63 |

44 |

83.02 |

131 |

87.92 |

| Married |

3 |

3.13 |

4 |

7.55 |

7 |

4.70 |

| Single, but cohabitating with a

significant other |

2 |

2.08 |

1 |

1.89 |

3 |

2.01 |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Separated |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Divorced |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.89 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5.66 |

3 |

2.01 |

| Note. Average age was 21.51 (SD = 6.98) in August–September 2021 group, 23.49 (SD = 8.11) in January–February 2022 group, and 22.21 (SD = 7.43) in the full sample. |

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of depression symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The PHQ-9 has been validated for screening for depression in the general population (Kroenke et al., 2001; Martin et al., 2006). The questionnaire measures frequency of symptoms such as “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” and “little interest or pleasure in doing things.” The PHQ-9 uses a 4-point Likert scale to measure frequency of symptoms over the past 2 weeks with the response options of not at all, several days, more than half the days, and nearly every day. Scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 are assigned to each of the four response categories, and a PHQ-9 total score is derived by adding the scores for each of the nine PHQ-9 items. Minimal depression is indicated by PHQ-9 total scores of 0–4, mild depression by scores of 5–9, moderate depression by scores of 10–14, moderately severe depression by scores of 15–19, and severe depression by scores of 20–27. Question 9 on the PHQ-9 is a single screening question assessing suicide risk. Interviewers were trained in appropriate protocol in the event of a positive screen for this question. Cronbach’s alpha for the PHQ-9 in the present study was .86.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7)

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) is a 7-item self-report anxiety questionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The GAD-7 has demonstrated reliability and validity as a measure of anxiety in the general population (Löwe et al., 2008). The questionnaire measures symptoms such as “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge,” and “not being able to stop or control worrying.” The format of the GAD-7 is similar to the PHQ-9, using a 4-point Likert scale to measure frequency of symptoms over the past 2 weeks with response options of not at all, several days, more than half the days, and nearly every day. GAD-7 scores are calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 for response categories and then adding the scores from the 7 items to derive a total score ranging from 0 to 21. Minimal anxiety is indicated by total scores of 0–4, mild anxiety by scores of 5–9, moderate anxiety by scores of 10–14, and severe anxiety by scores of 15– 21. Cronbach’s alpha for the GAD-7 in the present study was .86.

Analytic Strategy

Total scores for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were found to be positively skewed for both groups of participants. Binary logistic regression was therefore an appropriate method of analysis for this dataset, as binary logistic regression does not require normality of dependent variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). For two separate binary logistic regression models, individuals were classified as being either minimal or mild or above in depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) to create binary outcome variables. This choice of cutoff allowed each model (with time period as predictor) to satisfy the recommendation of Peduzzi et al. (1996) that there be at least 10 cases per outcome per predictor in binary logistic regression.

Prior to performing these intended primary analyses to answer the research questions, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether adding control variables to the logistic regression models was warranted. Chi-square tests of independence, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests, Fisher’s Exact tests, and an independent samples t-test were used to test for possible differences between the two time periods in individuals’ responses to demographic questions. In cases in which responses to demographic questions were shown to be significantly different across the two groups, appropriate tests were used to determine whether the demographic responses in question were associated with either of the two intended dependent variables.

Following the preliminary analyses, the intended two binary logistic regressions were conducted to answer the research questions. In the first binary logistic regression, time period was the predictor

(1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) and PHQ-9 depression category was the outcome (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal). In the second logistic regression, time period was the predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) and GAD-7 anxiety category was the outcome (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal). All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 28.

Results

Preliminary Demographic Analyses

Prior to the primary analyses, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether the two groups differed in their responses to demographic questions. Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests and an independent samples t-test were used to test for differences between groups in their responses to the seven demographic questions. Two of the seven tests were statistically significant at Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. Specifically, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests found significant differences between time periods on the race (p = .004) and employment (p < .001) demographic variables.

Based on the above significant results for the race and employment variables across the time periods, 2 x 2 tests were conducted to test for differences between specific race responses and specific employment responses across the two time periods. For these 2 x 2 tests, a chi-square test of independence was used when all expected cell counts were 5 or greater and Fisher’s Exact test was used when any expected cell counts were less than 5. To follow up the significant result for race, 2 x 2 tests were conducted for all pairs of race responses in which 2 x 2 tests were possible (i.e., in which there was at least one observation for each of the two race responses at both time periods). These follow-up 2 x 2 tests of responses to the race question across time periods found no statistically significant differences between pairs of race responses across time periods using Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. Follow-up 2 x 2 tests comparing all pairs of responses to the employment question across time periods found two statistically significant differences using Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. A chi-square test of independence showed that individuals were more likely to be employed full-time during January–February 2022 than August–September 2021 as compared to those not employed (including students), X2 (1, N = 99) = 9.29, p = .002. Fisher’s Exact test showed that individuals were more likely to indicate “prefer not to answer” during January–February 2022 than during August–September 2021 as compared to those indicating “not employed (including students),” p = .001.

The statistically significant tests for race and employment across time periods were followed up with additional tests to determine if depression or anxiety category (minimal vs. mild or above for each) was associated with individuals’ responses to the relevant race and employment questions. A Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test showed that depression category was not associated with individuals’ responses to the race question, p = .099. A Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test also showed that individuals’ anxiety category was not associated with individuals’ responses to the race question,

p = .386. With regard to employment, tests of association were conducted between the intended dependent variables and the specific employment responses that were found to differ between the two groups. A chi-square test of independence showed that individuals’ status as “not employed” vs. “employed full-time” was not associated with depression category, X2 (1, N = 99) = .63, p = .429. A chi-square test of independence also showed that these employment statuses were not associated with anxiety category, X2 (1, N = 99) = .27, p = .601. Similarly, Fisher’s Exact tests showed that individuals’ employment responses of “prefer not to answer” vs. “not employed (including students)” were not associated with depression category (p = .156) or anxiety category (p = .317). These results were interpreted as indicating that the ways in which individuals in the two time periods differed demographically did not have significant impact on the study’s dependent variables of interest. Therefore, binary logistic regressions were conducted with only time period as a predictor of each dependent variable.

Relationship Between Time Period and Severity of Depression Symptoms

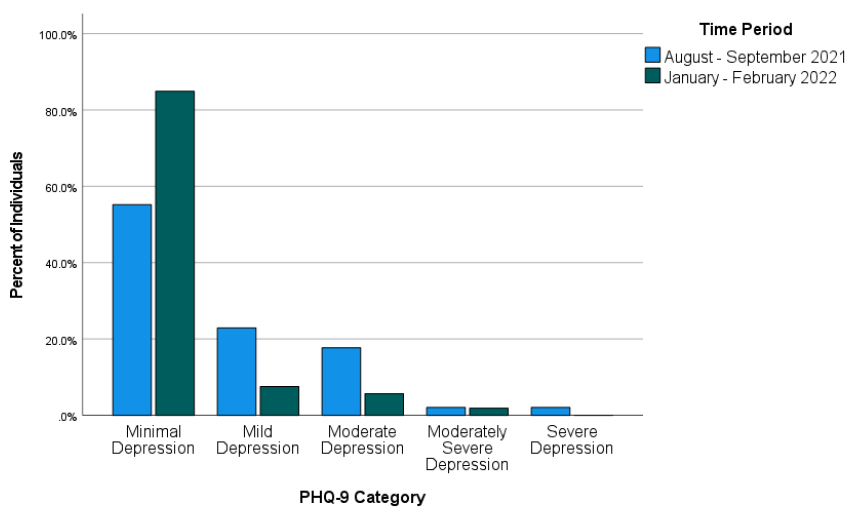

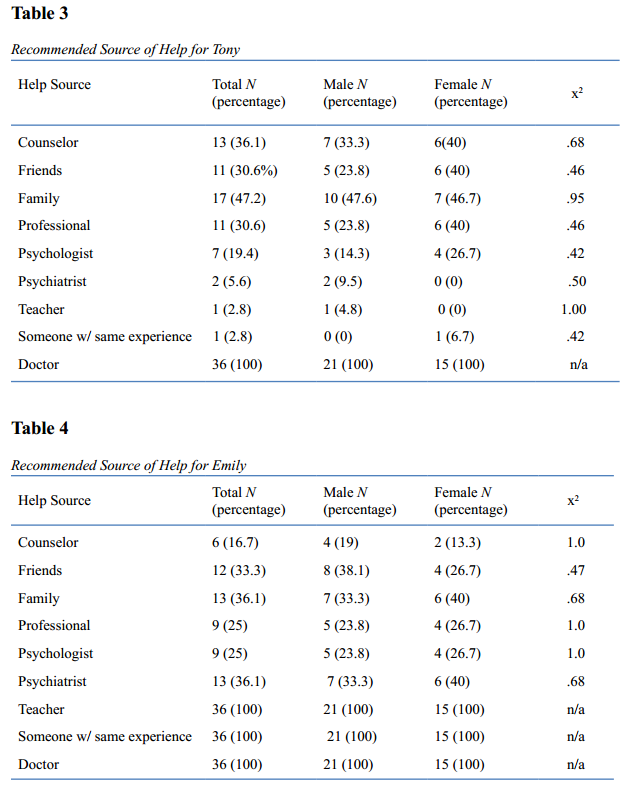

Most individuals in the study were in the minimal depression range on the PHQ-9 as compared to the other four categories. Figure 1 shows the percentage of individuals falling into each of the five PHQ-9 categories during each of the two time periods.

Figure 1

Percentages of Individuals Falling Into Each of the PHQ-9 Categories for Each of the Two Time Periods

Across both time periods combined (August–September 2021 and January–February 2022), 51 individuals (34.23%) were mild or above in depression while 98 (65.77%) were in the minimal range. Binary logistic regression was used to test whether time period predicted severity of depression symptoms. Time period was entered as a predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) of depression (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal depression). The overall binary logistic regression model was found to be statistically significant, χ2(1) = 14.46, p < .001, Cox & Snell R2 = .092, Nagelkerke R2 = .128. In the model, time period was found to be a significant predictor of depression, Wald χ2(1) = 12.17, B = 1.52, SE = .44, p < .001. The model estimated that the odds of being mild or above in depression were 4.56 times higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022 for individuals requesting a mental health check-in following COVID-19 exposure. Specifically, the predicted odds of being mild or above in depression were .81 during August–September 2021 and .18 during January–February 2022.

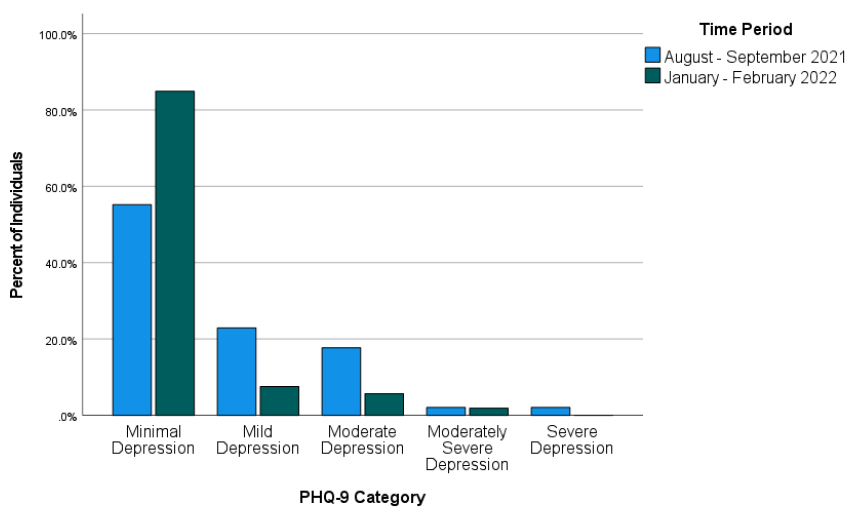

Relationship Between Time Period and Severity of Anxiety Symptoms

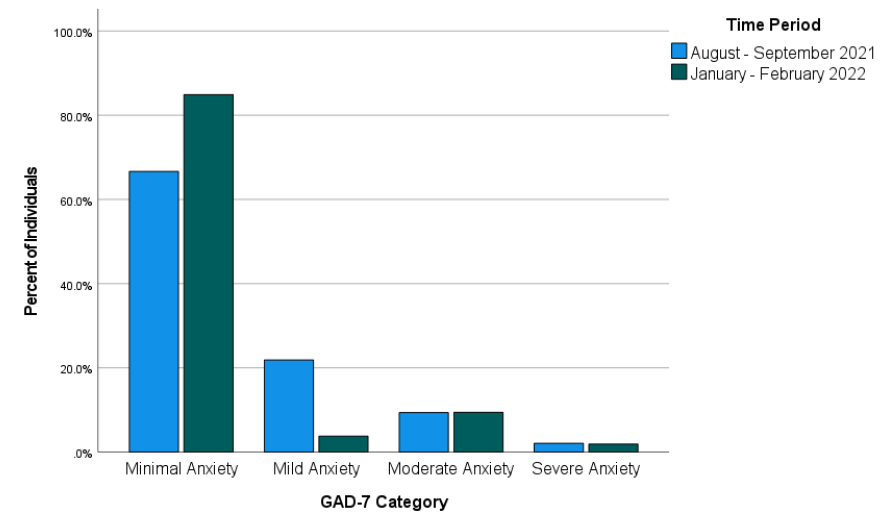

Most individuals in the study were in the minimal anxiety range on the GAD-7 as compared to the other three categories. Figure 2 shows the percentage of individuals falling into each of the four GAD-7 categories during each of the two time periods.

Figure 2

Percentages of Individuals Falling Into Each of the GAD-7 Categories for Each of the Two Time Periods

Across both time periods combined, 40 individuals (26.85%) reported anxiety at levels of mild or above and 109 individuals (73.15%) reported minimal anxiety. Binary logistic regression was used to test whether time period predicted severity of anxiety symptoms. Time period was entered as a predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) of anxiety (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal anxiety). The overall binary logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2(1) = 6.16, p = .013, Cox & Snell R2 = .041, Nagelkerke R2 = .059. In the model, time period was a significant predictor of anxiety, Wald χ2(1) = 5.51, B = 1.03, SE = .44, p = .019. Odds of being mild or above in anxiety were estimated by the model to be 2.81 times higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022 for individuals requesting a mental health check-in after exposure to COVID-19. Specifically, the predicted odds of being mild or above in anxiety were .50 during August–September 2021 and .18 during January–February 2022.

Discussion

This study examined whether time period would predict severity of depression and anxiety symptoms in a sample of individuals exposed to COVID-19 at a university in the Southeastern United States. More specifically, the study addressed the possibility that the likelihood of being mild or above in depression and anxiety would differ between two time periods following the university’s return to in-person operations in August 2021. The results of the study showed that the likelihood of being mild or above in depression and the likelihood of being mild or above in anxiety after exposure to COVID-19 were both higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022. This finding is in line with previous research that found improvements in psychosocial symptomatology in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Tang et al., 2022) and in contrast to research that did not find such improvements (McLeish et al., 2022). Based on the results of the present study, it appears likely that factors that differed between the two assessed time periods (first two months of fall 2021 vs. first two months of spring 2022) contributed to the observed difference in likelihood of depression and anxiety symptoms. McLeish et al. (2022) noted that vaccines were not widely available in their study that did not find such differences, while Tang et al. (2022), who did find significant differences, noted that vaccines were available at their second data collection point (January–March 2021). For individuals in the present study, COVID-19 vaccinations were available. Vaccination was strongly encouraged by university administrators following the return to campus, and more individuals on campus were vaccinated in spring 2022 than in fall 2021. Vaccinations might have lessened individuals’ COVID-19 concerns and contributed to more positive psychosocial outcomes during spring 2022 than fall 2021.

Besides vaccinations possibly lessening depression and anxiety symptoms, other environmental circumstances might also have played a role. The two time periods on which this study focused also differed in their proximity to a significant environmental event—a return to in-person operations on the campus where the individuals studied and/or worked. Early research on the mental health impact of COVID-19 highlighted the negative mental health effects of factors such as reduced physical activity (Silva et al., 2022), life disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Stamatis et al., 2022), and social distancing (Marroquín et al., 2020). Therefore, it is possible that symptoms of depression and anxiety in spring 2022 were affected by changes in specific circumstances known to have negatively impacted mental health earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, individuals’ physical activity likely increased because of a return to campus, and they might have perceived less disruption to their lives through being able to resume in-person activities. Although individuals in the present study who were exposed to COVID-19 during the first 2 months after the return to campus might have reaped some benefits from the return to more normal environmental circumstances, they might also have faced a period of adjustment. In contrast, individuals exposed to COVID-19 between January and February 2022 might have been more readjusted and reaped greater benefits from the return to campus, thereby reducing depression and anxiety symptoms.

Implications

This study’s findings on psychosocial symptomatology across time during the COVID-19 pandemic have important implications for the work of counselors. Based on the results of the present study, counselors planning outreach efforts to individuals exposed to COVID-19 should consider that as time passes, these individuals might be more stable with regard to symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, some individuals directly affected by COVID-19 might still be interested in receiving mental health information despite low levels of depression and anxiety. Many individuals in the present study scored as minimal in depression and anxiety but were still interested in receiving a mental health check-in. Thus, counselors should advocate for mental health information and resources to be made available to individuals who are known to be facing stressors related to COVID-19. Counselors should be prepared to have conversations to determine the contextual needs of individuals exposed to COVID-19 rather than relying only on standardized measures of psychosocial symptomatology. For example, counselors working with employees (such as university employees in the present study) should be attentive to the possibility that employees exposed to COVID-19 may be concerned about facing stigma in their workplace due to their exposure (Schubert et al., 2021).

Given that the present study focused on individuals from a university population, the study’s results also have specific implications for college counselors. College counselors should develop approaches to reach students during circumstances that might make traditional outreach challenging. For example, the present study used data from a mental health intervention in which service providers collaborated with university contact tracers to safely provide mental health resources by telephone to individuals exposed to COVID-19. College counselors should be prepared to connect clients with services at a distance. Previous research during the COVID-19 pandemic found that college students were interested in using teletherapy and online self-help resources, particularly if such services were made available for free (Ahuvia et al., 2022).

Besides preparing for flexible modes of service delivery, college counselors should be prepared to deliver interventions most likely to be useful to college students during the COVID-19 pandemic or similar pandemics. Those recently exposed to COVID-19 might benefit from discussing possible fears associated with COVID-19, experiences of stigmatization they might have experienced due to their exposure, and ways to maintain mental health during any period of quarantine or isolation that might be required. Those not recently exposed to COVID-19 might instead benefit from interventions that address other issues that might have resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic or societal responses to it. For example, if circumstances associated with the COVID-19 pandemic led to reductions in a client’s amount of exercise, a counselor can help the client identify ways they might increase their physical activity. Interventions promoting physical activity were found to reduce anxiety and depression in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic (Luo et al., 2022).

Limitations

This study had limitations that should be considered. First, with the study being retrospective and using secondary data from a clinical intervention, it was not possible to include measures that might have better clarified mechanisms of the changes that were observed in psychosocial symptoms. Thus, the possible explanations above of what might have driven these changes are tentative and future research should test them more directly. Second, individuals in the present study were likely to have been in greater distress than the general university population based on their exposure to COVID-19, which might limit the generalizability of the study’s findings. Third, individuals in the present study were from a single university in the Southeastern United States. Thus, our findings might not generalize to other regions where university-related COVID-19 policies might have differed. Fourth, the decision to create a binary independent variable to reflect time periods (August–September 2021 and January–February 2022) in the present study also entails a limitation. This decision was justifiable on the basis that it allowed for comparisons of individuals at similar points in academic semesters and during comparable periods of COVID-19 infection. However, this analysis decision means that inferences from the study’s results are limited to the two specific time periods that were analyzed. Fifth, individuals in the present study responded to items on the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 through a phone conversation with interviewers. Interviewer-administered surveys have been previously associated with greater tendencies toward socially desirable responses than self-administered surveys (Bowling, 2005). This might limit the present study’s generalizability in contexts where self-administrations of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 are used.

Future Research

The results of this study provide important directions for future research. Future researchers who can conduct prospective studies or who have access to larger retrospective datasets should aim to determine specific factors that might lead to improvement in mental health outcomes over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Knowledge produced by such studies could contribute to clinical applications in the future regarding COVID-19 or other pandemics that might occur. Relatedly, future research with larger samples of demographically diverse participants should explore possible demographic differences in specific mental health trajectories in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Future research should continue to focus specifically on those who are interested in mental health information and interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. To follow up this study’s findings, future quantitative and qualitative studies should aim to identify which individuals are interested in receiving mental health services and determine the best ways to deliver services to them. As a globally experienced stressor, the COVID-19 pandemic might have changed some individuals’ views of mental health and/or their receptiveness to mental health outreach. More specifically, some might be more receptive to available mental health information even at lower thresholds of anxiety, depression, or other psychosocial symptoms. Such clients might be interested in preventive services or their interest in mental health information might be driven by other factors. Future studies should address these possibilities more directly than was possible in the present retrospective study.

Conclusion

Overall, the present study provided a positive picture regarding psychosocial symptomatology in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from this study of students and employees at a university in the Southeastern Unites States following their return to campus found that many individuals requesting mental health information after exposure to COVID-19 showed minimal levels of depression and anxiety. Individuals in the study were more likely to be in these minimal ranges during January–February 2022 than August–September 2021. COVID-19 will continue to have effects in individuals’ lives through future infections and potentially through lasting effects of previous stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. As organized in-person activities resume and COVID-19 infections continue, counseling researchers and practitioners should continue efforts to best characterize and address individuals’ mental health needs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Ahuvia, I. L., Sung, J. Y., Dobias, M. L., Nelson, B. D., Richmond, L. L., London, B., & Schleider, J. L. (2022). College student interest in teletherapy and self-guided mental health supports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2062245

Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054

Bowling, A. (2005). Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. Journal of Public Health, 27(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdi031

Bzdok, D., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2020). The neurobiology of social distance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(9), 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.016

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, March 15). COVID-19 timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html

Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., Rettew, J., & Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 134–141.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466

Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 126–134.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 15(7), Article e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A., & Bu, F. (2021). Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X

Fioravanti, G., Benucci, S. B., Prostamo, A., Banchi, V., & Casale, S. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological health in a sample of Italian adults: A three-wave longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 315, Article 114705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114705

Food and Drug Administration. (2021, August 23). FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

Huckins, J. F., daSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E. I., Meyer, M. L., Wagner, D. D., Holtzheimer, P. E., & Campbell, A. T. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), Article e20185.

https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Liu, C. H., Stevens, C., Wong, S. H. M., Yasui, M., & Chen, J. A. (2019). The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among U.S. college students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depression and Anxiety, 36(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22830

Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46(3), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

Luo, Q., Zhang, P., Liu, Y., Ma, X., & Jennings, G. (2022). Intervention of physical activity for university students with anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215338

Marroquín, B., Vine, V., & Morgan, R. (2020). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Research, 293, Article 113419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419

Martin, A., Rief, W., Klaiberg, A., & Braehler, E. (2006). Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(1), 71–77.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003

McLeish, A. C., Walker, K. L., & Hart, J. L. (2022). Changes in internalizing symptoms and anxiety sensitivity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 44, 1021–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-022-09990-8

Meyer, J., McDowell, C., Lansing, J., Brower, C., Smith, L., Tully, M., & Herring, M. (2020). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in response to COVID-19 and their associations with mental health in 3052 US adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), Article 6469.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186469

Oh, H., Marinovich, C., Rajkumar, R., Besecker, M., Zhou, S., Jacob, L., Koyanagi, A., & Smith, L. (2021). COVID-19 dimensions are related to depression and anxiety among US college students: Findings from the Healthy Minds Survey 2020. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.121

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Dosil Santamaría, M., & Picaza Gorrotxategi, M. (2020). Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: An investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 1491.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01491

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R., & Feinstein, A. R. (1996). A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49(12), 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Prati, G., & Mancini, A. D. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological Medicine, 51(2), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000015

Rettie, H., & Daniels, J. (2021). Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000710

Riehm, K. E., Holingue, C., Kalb, L. G., Bennett, D., Kapteyn, A., Jiang, Q., Veldhuis, C. B., Johnson, R. M., Fallin, M. D., Kreuter, F., Stuart, E. A., & Thrul, J. (2020). Associations between media exposure and mental distress among U.S. adults at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(5), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.008

Schubert, M., Ludwig, J., Freiberg, A., Hahne, T. M., Romero Starke, K., Girbig, M., Faller, G., Apfelbacher, C., von dem Knesebeck, O., & Seidler, A. (2021). Stigmatization from work-related COVID-19 exposure: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126183

Silva, D. T. C., Prado, W. L., Cucato, G. G., Correia, M. A., Ritti-Dias, R. M., Lofrano-Prado, M. C., Tebar, W. R., & Christofaro, D. G. D. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity level and screen time is associated with decreased mental health in Brazillian adults: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Psychiatry Research, 314, Article 114657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114657

Şimşir, Z., Koç, H., Seki, T., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Death Studies, 46(3), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1889097

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), Article e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Stamatis, C. A., Broos, H. C., Hudiburgh, S. E., Dale, S. K., & Timpano, K. R. (2022). A longitudinal investigation of COVID-19 pandemic experiences and mental health among university students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12351

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Tang, N. K. Y., McEnery, K. A. M., Chandler, L., Toro, C., Walasek, L., Friend, H., Gu, S., Singh, S. P., & Meyer, C. (2022). Pandemic and student mental health: Mental health symptoms amongst university students and young adults after the first cycle of lockdown in the UK. BJPsych Open, 8(4), Article e138.

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.523

Wise, T., Zbozinek, T. D., Michelini, G., Hagan, C. C., & Mobbs, D. (2020). Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

Royal Society Open Science, 7(9), Article 200742. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200742

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Wesley B. Webber, PhD, NCC, is a postdoctoral scholar at East Carolina University. W. Leigh Atherton, PhD, LCMHCS, LCAS, CCS, CRC, is an associate professor and program director at East Carolina University. Kelli S. Russell, MPH, RHEd, is a teaching assistant professor at East Carolina University. Hilary J. Flint, NCC, LCMHCA, is a clinical counselor at C&C Betterworks. Stephen J. Leierer, PhD, is a research associate at the Florida State University Career Center. Correspondence may be addressed to Wesley B. Webber, Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies, Mail Stop 677, East Carolina University, 1000 East 5th Street, Greenville, NC 27858-4353, webberw21@ecu.edu.

Apr 29, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 2

TeShaunda Hannor-Walker, Lynn Bohecker, Lacey Ricks, Sarah Kitchens

Literature does little to explore the perceptions of Black adolescents with depression or their perspective of treatment effectiveness. Studies are usually from urban areas and there is a dearth of research with Black adolescents from rural areas. This study explored the unique personal experiences of Black adolescents located in the rural southeastern United States, with the purpose of gaining a clearer understanding when working with this population. An interpretative qualitative method was used to explore 10 participants’ interpretation of their experiences to gain insight in how they make meaning of those experiences. Five significant categories were found to capture participant themes: (a) definition of depression, (b) seeking treatment, (c) coping and problem solving strategies, (d) types of emotional support, and (e) contributing factors to depression. Specific recommendations and interventions are suggested for mental health clinicians to become more educated and aware when working with Black adolescents.

Keywords: Black adolescents, depression, treatment effectiveness, rural, contributing factors

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020). The World Federation for Mental Health (2012) estimated that by 2030, more people will be impacted by depression than any other health problem. In the United States, approximately 13.3% of adolescents, or 3.2 million, had at least one major depressive episode and 9.5% were Black (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2013). Black people have experienced more severe forms of mental health conditions than individuals of other races because of unmet needs and other barriers (NIMH, 2013). In fact, Black people were reported to be 10% more likely to experience serious mental health problems than the general population (Shushansky, 2017), and Black children have a suicide rate that is almost two times higher than that of their White counterparts (Bridge et al., 2018).

Weaver et al. (2015) noted that although 90% of rural Black people live in the southeastern part of the United States, there are only two studies that specifically examined depression among rural Black people using national data (i.e., Probst et al., 2006; Willis et al., 2003). Most studies of depression that include Black youth are based on data from urban communities (Al-Khattab et al., 2016; Conner & Yeh, 2018; Ofonedu et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2015). This suggests there is a dearth of research exploring Black adolescent experiences of depression in rural communities, and there is even less research focusing on Black youth who live in the rural southeastern United States (Smokowski et al., 2015: Weaver et al., 2015). The goal of this study was to explore the unique experiences of Black adolescents living in the rural southeastern United States who had been diagnosed with depression.

Contributing Factors to Depression in Black Adolescents

Adolescents who suffer from depression may experience substantial negative health and social consequences in late adolescence and adulthood (Lu, 2019). Black adolescents are particularly vulnerable to these consequences because they are more likely to live in low-resource neighborhoods and because they contend with the negative psychological impacts of racial discrimination (Robinson et al., 2015). Choi et al. (2006) found that ethnic minorities have higher scores on social stress and mental distress and lower scores on coping, self-esteem, and family cohesion. The depressive symptoms experienced by Black adolescents are often socially and culturally based (Lu et al., 2017). Therefore, it is essential for counselors, school personnel, and related professionals to remain abreast of the current research on depressive signs and symptoms, beliefs about treatment, and specific needs of Black adolescents.

Choi et al. (2006) discovered that Black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescents in the United States have consistently higher levels of social stress beginning in childhood compared to their White counterparts. Breland-Noble et al. (2010) found that relationship problems, academic problems, bereavement, and stress were primary triggers for depressive symptoms among Black adolescents. Ofonedu et al. (2013) determined in their study of Black adolescents that life events in the home, school, and community contributed to depressive symptoms. These factors included (a) a stressful home life, (b) stressful life circumstances and unique life experiences at school, and (c) the experience of high levels of violent crimes in neighborhoods. Stress is clearly a contributing factor to the depressive symptoms of Black adolescents.

Symptoms of Depression in Black Adolescents

Although understanding national trends and contributing factors can help practitioners identify adolescents suffering from depression, it is also important to understand potential racial and ethnic differences in the expression of adolescent depression (Lu, 2019). The manifestations of depressive symptoms vary in Black youth and affect all dimensions of physical, psychological, interpersonal, and social being (Ofonedu et al., 2013). In the Black community, mental health conditions have often been unacknowledged, misunderstood, and misdiagnosed (Shushansky, 2017; Vontress et al., 2007). According to Vontress et al. (2007), Black people often experience cultural dysthymia and mental health symptoms such as low-grade depression; feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and anger; aggression; and self-destructive behaviors. Vontress et al. (2007) characterized these symptoms as a “psychosocial condition” grounded in external societal experiences of discrimination and oppression that often go unrecognized (p. 131). Additional studies are needed to show how to better identify individuals suffering from depression and thereby increase the effectiveness of treatment for Black adolescents (Ofonedu et al., 2013).

As in adults, unrecognized or undiagnosed dysthymia or symptoms of low-grade depression in adolescents can contribute to poor health and problematic behaviors (Saluja et al., 2004). Researchers discovered that untreated dysthymia elevates the risk of disruptive behaviors, anxiety, substance abuse, unsafe sexual practices, involvement in fights, lower achievement on tests, lower teacher-rated grades, and poorer peer relationships (Saluja et al., 2004). Auger (2005) discovered that the many signs and symptoms of adolescent depression were overlooked not only by parents but also by school systems, administrators, counselors, and teachers who daily were in a very unique position to identify those at risk of depression. Many cases of adolescent depression, particularly among minorities, have gone undiagnosed, misdiagnosed, and untreated (Cook et al., 2017; Shushansky, 2017). A better understanding of the unique experiences of Black adolescents diagnosed with depression would help improve symptom recognition, which may in turn reduce misdiagnosis and increase treatment effectiveness.

An understanding of the cultural implications and influence that oppression, prejudice, and various forms of discrimination have on Black people’s mental health in the United States is helpful in contextualizing and normalizing symptoms of depression and reducing instances of misdiagnosis. Hope et al. (2017) posited that discrimination remains a common experience for Black adolescents that can impact not only the onset of depression but also the quality of and access to mental health services. Furthermore, according to Liang et al. (2016), racial disparities exist, as Black youth are more likely to be misdiagnosed as having psychotic and disruptive behavior problems compared to mood (i.e., depression) and substance abuse disorders.

Lu et al. (2017) echoed these sentiments, stating that depression presents differently for Black adolescents. It is essential for Black adolescents to use their own language when describing their depressive symptoms. Additionally, it is important for clinical and school counseling professionals to be aware of gender differences in Black adolescents’ expression of depression, specifically in terms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The findings of Breland-Noble et al. (2010) indicated that female Black adolescents seem to internalize behaviors (e.g., becoming withdrawn, exhibiting visible sadness), while male Black adolescents seem to externalize behaviors (e.g., becoming angry or acting out). Lu et al. (2017) further highlighted that “adolescents develop [symptoms] as a means of coping in response to environmental factors” (p. 614). More research is needed to understand how depressed Black adolescents describe their symptoms and assign meaning to their experiences of depression.

Coping Strategies of Black Adolescents

In addition to presenting different symptoms than individuals of other racial groups, Black adolescents have the lowest coping skills scores compared to their peers (Conner & Yeh, 2018). Recent studies suggest that adolescents who live in low-resourced neighborhoods feel like they have limited options in how to respond to stressful and anxiety-provoking situations because of limited or ineffective coping skills (Robinson et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2015). There are indications that Black adolescents cope with depression in a variety of contexts. Some Black adolescents describe depression as a way of life, noting that everybody becomes depressed one way or another (Ofonedu et al., 2013). Researchers have shown that some Black adolescents conceal their feelings of depression because they are uncertain of how others would perceive them (Al-Khattab et al., 2016; Ofonedu et al., 2013). For instance, some Black adolescents reported trying to manage their depression independently and only going to an adult as a last resort (Breland-Noble et al., 2010). Black adolescents have been shown to manage their depression by strong will and spiritual beliefs (Ofonedu et al., 2013). Conner and Yeh (2018) highlighted how Black adolescents cope with depression in spiritual and creative ways such as listening to music, dancing, and writing.

In 2016, Al-Khattab et al. discovered that Black adolescents controlled their depression through their interactions with other people. Al-Khattab et al. identified five typology interaction models, which include hiding feelings of depression, lashing out verbally or physically toward others, seeking help from others to address emotional feelings, joining with others in social activities, and having others approach them about behavioral and mood changes. Therefore, it is critical for Black adolescents to better understand their experiences with depression and how interactions with others may influence their symptoms.

Treatment of Depression in Black Adolescents

Cook et al. (2017) noted that there are barriers to accessing mental health services and quality of care, which include stigma associated with mental illness, distrust of the health care system, lack of providers from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds, lack of culturally competent providers, and lack of insurance or underinsurance. Often these barriers cause Black people to be unable or reluctant to seek help (Shushansky, 2017). Although Black adolescents may feel that treatment can be effective, many are reluctant to attend therapy because of the stigma and possible misdiagnosis of their symptoms, much of which has been influenced by their culture (Al-Khattab et al., 2016; Lindsey et al., 2010; Ofonedu et al., 2013). Positive results have been seen when using family-centered prevention programs to address depressive symptoms in Black adolescents (Brody et al., 2012). Jacob et al. (2013) determined that behavioral activation was effective for decreasing depressive symptoms and impairments for the Black adolescents who participated in their study.

As highlighted by a study of Black adults from a rural faith community, Black people living in rural communities suffering from depression face additional barriers to treatment such as (a) a lack of medical resources, (b) insufficient education about depression, and (c) stigma (Bryant et al., 2013). Sullivan et al. (2017) learned that terminology was crucial when discussing treatment with rural Black adults on a stigmatized topic such as mental illness. Parental concerns about marginalization because of having a child with a mental health diagnosis and some primary care providers’ characterization of mental health symptoms as a “phase” have been found to be barriers to treatment for Black children living in rural communities (Murry et al., 2011). Working with Black children who live in poverty, Graves (2017) identified cultural and macro-level barriers that influence the process of seeking treatment.

Treatment of mental health disorders extends from diagnoses. Considering the differences in symptoms and frequency of misdiagnosis, it is not surprising that treatment options for Black adolescents have shown varied outcomes across the literature. Additionally, some researchers suggested that new measures need to be developed for accurately identifying depression in diverse populations, which would then inform modifications in treatment (Ofonedu et al., 2013). Having a better understanding of the unique and complex experiences of Black adolescents may help parents, therapists, schools, and counseling professionals understand and identify those most at risk for depression. Planey et al. (2019) discovered that Black youth viewed seeking mental health treatment as a contextual and relational process rather than an event. What is clear is that more culturally diverse training for therapists, schools, and counseling professionals is needed to prevent, detect, and implement interventions for minorities experiencing depression during the disease’s earlier stages. Likewise, research exploring Black adolescents’ unique experiences of symptoms, environmental factors, and coping strategies remains necessary in order to inform effective treatment.

Purpose of the Present Study

The review of the literature captured symptoms and coping strategies unique to Black adolescents. Studies highlight that environmental factors contribute to depressive symptoms in this population. Furthermore, disparities exist in mental health care for adolescents, specifically for minorities (Alegria et al., 2010; Brenner, 2019; Lake & Turner, 2017). This clear gap in the literature indicates insufficient knowledge regarding the personal experiences of Black adolescents with depression. Most of the studies in the extant literature took place in urban areas; little is known about rural experiences and even less is known about experiences in the southeastern United States. This qualitative study was designed to help fill that gap. It posed an overarching research question to Black adolescents living in the rural southeastern United States: “What is your experience with depression?” This study was designed to offer human services professionals a clearer understanding of the unique experiences of Black adolescents in this geographical region who had been diagnosed with depression, with the hope of informing clinical practices.

Method

The goal of this study was to explore the unique experiences of Black adolescents living in the rural southeastern United States who had been diagnosed with depression. The research design for the study was a basic interpretive qualitative method, as described by Merriam (2009). The purpose of this method is to understand the perspectives of the participants involved by uncovering and interpreting their meanings (Everall et al., 2006). This purpose was well-suited to the overall objective of this study, which was to gain a clearer understanding of the unique personal experiences of Black adolescents living with depression in the rural southeastern United States.

According to Merriam (2009), interpretive qualitative research is founded on the idea that people and their interactions with their world, or reality, socially construct meaning. Researchers using this method are interested in how individuals “interpret” their experiences, “construct their worlds,” and assign “meanings” to their experiences (Merriam, 2009, p. 38). Moreover, Merriam asserted that interpretive qualitative research has multiple meanings and is a complex phenomenon ideal for attempting to understand and treat Black adolescents with depression. Using Merriam’s (2009) model, researchers “strive to understand the meanings individuals construct regarding their world and their experiences” in a natural setting (p. 4). Another characteristic is that the researcher serves as the primary instrument for both collecting and analyzing data. The research process is inductive rather than deductive, which means that the researcher gathers data in an effort to “build concepts, hypotheses, or theories” in the forms of themes and categories (Merriam, 2009, p. 5). A final characteristic of this model is that interpretive qualitative research is richly descriptive and includes details about the context, the participants involved, and quotations and interview excerpts (Merriam, 2009).

Merriam (2009) noted that certain elements of the basic interpretive qualitative design may overlap with other designs, particularly when concepts of cultural values are discussed and explored. Merriam’s design does not require researchers to give a full sociocultural interpretation of the data, as is done in ethnography. Indeed, this study does not provide a full sociocultural interpretation. However, the data were analyzed using Patton’s (1987) content analysis model because the model provides a rigorous, systemic, and ethical procedure for analyzing data. Merriam’s model for collecting data and Patton’s model for analyzing data form a rich methodological combination that enhances the trustworthiness of the research study and improves the transferability of its findings.

Participants and Procedure

The university IRB granted approval for this study. Purposive sampling was used to identify 10 Black adolescents living in the rural southeastern United States who were being treated for depression. The southeastern part of the United States was selected because it contains fewer metropolitan areas that have been studied specifically. Each of the participants met the following criteria: (a) self-identified as Black, (b) was between the ages of 13 and 17, (c) was willing to participate, (d) had secured a signed informed consent form from their parents, (e) had signed a participant assent form, and (f) was currently under the care of a counselor either in or out of school for depression. The participants ranged in age from 13 to 17 years old and were in grades seven through 12. Six participants were female and four were male.

Approval was obtained in advance from a public school system located in the rural southeastern United States. The public school system administrator agreed to send the letter of invitation along with the consent and assent forms to the parents and potential participants. In addition, the first author sent a packet of information to a counseling agency; school professionals, including professional school counselors and school psychologists; and social workers. The packet contained an invitation letter requesting that the packet be shared with potential participants and their parents; it also contained consent and assent forms. The informed consent form described the study and the efforts that would be taken to protect the confidentiality of the participants’ information. The informed consent form stated that the risk of participating was the normal discomfort of sharing one’s experiences with depression and that if a participant felt uncomfortable, they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Parents and participants signed the consent and assent forms, respectively, and returned them to either the local counseling agency or school professionals, who forwarded the forms to the first author. The first author then contacted the parents, with the participants present, to schedule a 45- to 90-minute, face-to-face interview with the participant. The informed consent form was verbally reviewed, ensuring that the parents and participants understood that a second interview to review and correct the interpretation would be optional. Interviews took place either during the day in a private room at the school or outside of school hours in the first author’s office. Because adolescent depression is considered a sensitive topic, participants were instructed to follow up with their counselor if they experienced adverse feelings as a result of participating in the study.

Data Collection and Analysis

The first author met with each of the 10 participants for a single semi-structured interview that lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. In phenomenological research, the researcher follows the essence of participants’ responses (van Manen, 1997). The first author spent time establishing rapport with the participants. Once the first author believed a participant was comfortable, she asked the participant the overarching question, “What is your experience with depression?” Follow-up questions specific to each participant were used to probe the participants’ responses regarding their experience as Black adolescents living with depression in the rural southeastern United States. Several participants expressed a reluctance to fully disclose or discuss their experiences with depression; however, no participants withdrew from the study, and all participants completed the first interview. At the end of the first interview, the participants were notified that they would be contacted for a second interview to review the transcript of the first interview and verify its accuracy and trustworthiness.