Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

William H. Snow, Thomas A. Field

This lead article introduces a special issue of The Professional Counselor designed to inform and support faculty, staff, and administrative efforts in starting or revitalizing doctoral degree programs in counselor education and supervision. We review the 14 studies that make up this issue and summarize their key findings. Seven key themes emerged for faculty and staff to consider during program development: (a) the current state of research, (b) doctoral program demographics and distribution, (c) defining quality, (d) mentoring and gatekeeping, (e) increasing diversity, (f) supporting dissertation success, and (g) gaining university administrator support. We recognize the vital contribution of these articles to doctoral counselor education and supervision program development while also highlighting future directions for research emerging from this collection.

Keywords: doctoral, counselor education and supervision, research, quality, diversity

This special issue of The Professional Counselor features 14 articles on doctoral counselor education and supervision (CES) to inform and support faculty, staff, and administrative efforts in starting or revitalizing doctoral degree programs in CES. In this introductory paper, we begin by providing context for the special issue’s focus on doctoral CES programs. We then reflect on the series of articles in this special issue that collectively address a myriad of topics pertinent to high-quality doctoral programs in CES. We further suggest critical themes and principles for faculty and administrators to follow when starting and operating doctoral counselor education programs and for students to reflect on when selecting a doctoral counselor education program. In our conclusion, we offer future directions for research emerging from the contributions to this special issue.

Doctoral CES Programming in Context

The CES doctorate is an increasingly sought-after degree. From 2012 to 2018, the number of CES doctoral programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) increased by 50%, with a 43.8% increase in student enrollment (CACREP, 2013, 2019). At the time of writing, there are now 84 CACREP-accredited doctoral programs (CACREP, n.d.). These CACREP-accredited doctoral programs have nearly 3,000 enrolled students and produce almost 500 doctoral graduates each year (CACREP, 2019). Doctoral study within counselor education prepares leaders for the profession (Adkinson-Bradley, 2013; West et al., 1995).

For over 70 years, the allied mental health professions, including counseling, were heavily influenced by psychology’s scientist–practitioner (aka Boulder) model of the 1940s (Baker & Benjamin, 2000), the scholar–practitioner model of the 1970s (Kaslow & Johnson, 2014), and the lesser-known clinical–scientist model of the 1990s (Stricker & Trierweiler, 2006).

In contrast to psychology, the purpose of doctoral counselor education was never to train entry-level clinicians. Instead, it has historically been to prepare counseling professionals to become counselor educators and advanced supervisors to train entry-level clinicians at the master’s level (West et al., 1995; Zimpfer et al., 1997). Counseling has needed to develop its own model(s) for effective doctoral education. Yet, relatively little literature exists to inform the development and implementation of doctoral programs within counselor education.

This special issue represents a concerted effort to address that knowledge gap. Research teams consisting of 46 counselor educators and student researchers from across the country answered the call with findings from 14 studies that we have organized under seven themes and related critical questions. The collective research provides invaluable information for anyone desiring to initiate, develop, and sustain a high-quality CES doctoral program on their campus. The following is a summary of the key themes, organizing questions, and findings.

Key Themes, Questions, and Findings

In preparation for this special issue, The Professional Counselor put out a call for papers with no restrictions on covered topics. The request simply asked authors to submit their scholarly contributions to a special issue on doctoral counselor education. Those accepted for the special issue fell naturally into one of the following seven themes: (a) the current state of research, (b) doctoral program demographics and distribution, (c) defining quality, (d) mentoring and gatekeeping, (e) increasing diversity, (f) supporting dissertation success, and (g) gaining university administrator support.

The Current State of Research

Research on the preparation of doctoral-level counselor educators shaped the first theme. Litherland and Schulthes (2020) conducted a thorough literature review in their paper, “Research Focused on Doctoral-Level Counselor Education: A Scoping Review.” They examined peer-reviewed articles published on the topic from 2005 to 2019 found in the PubMed, ERIC, GaleOneFile, and PsycINFO databases. After initially retrieving nearly 10,000 citations, they found only 39 studies met their inclusion criteria, an average of less than three published studies per year. Their work suggests the need for a long-term research strategy and plans to advance CES program development. The studies comprising this special issue begin to address some of that void by adding 14 peer-reviewed articles to the 39 Litherland and Schulthes already found, a significant increase in just a single publication in one year.

Doctoral Program Demographics and Distribution

The current number and location of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs relative to present and future demands for graduates to serve our master’s programs or the CES doctoral pipeline is the essence of the second theme. Field et al. (2020), in “The Pipeline Problem in Doctoral Counselor Education and Supervision,” analyzed regional distributions of existing doctoral programs. Despite recent growth in the number of doctoral programs, they found a significant difference in the number of CACREP-accredited doctoral programs by region. For example, the Western United States has the largest ratio of counseling master’s degree programs to doctoral programs (18:1), with only two doctoral and 35 master’s programs with CACREP accreditation in a region with nearly 64 million inhabitants. The data demonstrate a greater need for more CES doctoral programs in certain geographical regions. Without developing new CES programs accessible in regions with few doctoral degree options, a pipeline problem may persist whereby demand surpasses supply. This pipeline problem may result in some master’s programs struggling to hire faculty in regions with fewer doctoral programs, as prior studies have found that geographic location is a key reason why candidates accept faculty positions (Magnuson et al., 2001).

Defining Quality

The third theme centers on how to define high quality in CES doctoral education. Four studies in this special issue were aimed at exploring questions of quality doctoral counselor education in depth. Areas of investigation included program components, preparation for teaching and research, and promoting a research identity among students.

High-Quality Doctoral Programs

Preston et al. (2020) examined this theme in “Components of a High-Quality Doctoral Program in Counselor Education and Supervision.” Their qualitative study of 15 CES faculty revealed five critical indicators of program quality: (a) supportive faculty–student and student–student relationships; (b) a clearly defined mission that is supported by the counseling faculty and in alignment with the broader university mission; (c) development of a counselor educator identity with formal curricular experiences in teaching, research, and service; (d) a diversity orientation in all areas, including the cultural diversity of faculty and students, as well as a variety of experiences; and (e) reflection of the Carnegie classification of its institution, as aligned with its mission and level of support.

These findings on the components of a high-quality CES doctoral program are useful to multiple audiences. Faculty engaged in doctoral program development can use this as a partial checklist to ensure they are building quality components into what they are proposing. Faculty of existing programs can use these findings as a self-check for reviewing and improving their quality. Finally, potential doctoral students can use these five critical indicators of quality to inform their program search.

Quality Teaching Preparation

Teaching is a significant activity of faculty. Despite its importance, at least one recent study (Waalkes et al., 2018) found a lack of emphasis and rigor in graduate student training. Baltrinic and Suddeath (2020) conducted a study on the components of quality teacher preparation to inform preparation efforts. Their article, “A Q Methodology Study of a Doctoral Counselor Education Teaching Instruction Course,” found three broad critical factors of teacher preparation: course design, preparation for future faculty roles, and a focus on instructor qualities and intentionality in their communications. Most interesting are the practices they found were of less value yet commonly utilized in programs across the country. A detailed read of their study will likely challenge some of the activities currently deemed to be best practices.

Quality Research and Scholarship

The ability of doctoral graduates to demonstrate research and scholarship prowess is critical in their competitiveness in securing top faculty positions. In a prior study on faculty hiring by Bodenhorn and colleagues (2014), over half of faculty position announcements asked for demonstrated research potential. How we prepare students for their role in generating knowledge for the profession was an area of preparation addressed by Limberg et al. (2020). They suggest in their article, “Research Identity Development of Counselor Education Doctoral Students: A Grounded Theory,” that programs need to have strong faculty research mentors. Faculty who can involve students experientially in their research are more apt to instill a robust research identity and sense of self-efficacy in their doctoral students. Limberg et al. also offer other practical steps programs can take to increase research-oriented outcomes in their graduates.

In their article titled “Preparing Counselor Education and Supervision Doctoral Students Through an HLT Lens: The Importance of Research and Scholarship,” Brown et al. (2020) examined CES faculty publication trends from 2008 to 2018 from 396 programs. They found that although programs from Carnegie-classified R1 and R2 universities accounted for nearly 70% of the research, 30% was produced by faculty from doctoral/professional universities (D/PU) and master’s programs (M1). There is clear evidence that research is essential for all counselor education faculty, no matter the Carnegie level at which their university is classified.

Mentoring and Gatekeeping

The fourth theme pertains to how CES doctoral faculty can best serve as mentors and gatekeepers, as well as educate and train doctoral students to help in that same role when they graduate and become faculty in other institutions. Given the importance of the professional relationship in counseling (Kaplan et al., 2014), relationship building would seem to be a natural part of the mentoring and advising experience. Dipre and Luke (2020) advocate for such an advising model in their article, “Relational Cultural Theory–Informed Advising in Counselor Education.” Kent et al. (2020) provide further guidelines for a more specialized student population in their article, “Mentoring Doctoral Student Mothers in Counselor Education: A Phenomenological Study.”

Mentoring and advising are generally rewarding experiences as we prepare the next generation of leaders in the profession, but at times the conversations we need to have are challenging and tough. DeCino et al. (2020) provide an important view to an often-stressful component of advising with their article, “‘They Stay With You’: Counselor Educators’ Emotionally Intense Gatekeeping Experiences.” Their work uncovered five powerful sets of issues for faculty advisors to consider, including the early warning signs to look for, elevated student misconduct, the trauma of student dismissal, the stress of involvement in legal interactions, and the changes that occur from such experiences. Their article is a must-read for any new faculty mentor or advisor.

Many of the students we mentor and advise will assume similar roles as faculty members and confront the issues above. Freeman et al. (2020) provide a model and exploratory data in “Teaching Gatekeeping to Doctoral Students: A Qualitative Study of a Developmental Experiential Approach.” Intentional integration of gatekeeping training is essential to preparing future faculty for their duties as faculty advisors and mentors.

Increasing Diversity

The fifth theme encompasses research on what changes to the structure of programs are needed to establish more diverse CES doctoral learning communities. There is a need for more doctoral graduates in CES, but more importantly, we need more graduates and faculty from culturally diverse backgrounds. The 2016 CACREP Standards (2015) emphasized this in requiring accredited programs to engage in a “continuous and systematic effort to attract, enroll, and retain a diverse group of students and to create and support an inclusive learning community” (Standard 1.K.). CACREP sets the standard to be met, but programs are often at a loss as to what is most effective.

Ju et al. (2020) generated findings to help guide faculty in the most effective strategies in “Recruiting, Retaining, and Supporting Students From Underrepresented Racial Minority Backgrounds in Doctoral Counselor Education.” They suggest that faculty must prioritize getting involved with students from the onset of recruiting and staying engaged through the student’s program completion. The involvement needs to be personalized, which requires a robust faculty–student connection. Another principle they espouse is that faculty need to value the cultural identity of diverse students and help to connect them to that identity. Faculty can better foster this connection when they share their own cultural identity, encourage students to express their uniqueness, and share research interests connected to their cultural identity. Ju et al. also remind us that diverse students are more than members of a cultural group—they desire individual mentorship and support tailored to their specific needs. Finally, faculty are encouraged to work with diverse students to address multicultural and social justice issues at the institution and in the profession. If the principles derived from this article are sincerely applied, they will likely go a long way to promoting a more culturally sensitive academic culture.

Many doctoral programs are under-resourced, and funding to increase diversity is often hard to come by. Branco and Davis (2020) provide insight on a significant financial and mentoring support program for diverse students funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and administered by the National Board for Certified Counselors in their article, “The Minority Fellowship Program: Promoting Representation Within Counselor Education and Supervision.” Their study found that although the scholarship funds were helpful, students also appreciated the program’s networking, cohort model, and mentorship. This program has successfully aided in the graduation of 158 doctoral students to date who will go on to serve their diverse communities.

Supporting Dissertation Success

The sixth theme is grounded in helping students complete their dissertation and avoid becoming an “all but dissertation” (ABD) statistic. This concern is critical, as the doctoral completion rate across all disciplines is only 57% (Neale-McFall & Ward, 2015). It is unclear if CES doctoral programs do any better or worse than other disciplines, and up until now, there has been a dearth of research on how to improve the odds of a student finishing their doctoral program (Purgason et al., 2016).

Ghoston et al. (2020) provide informed guidance in their article “Faculty Perspectives on Strategies for Successful Navigation of the Dissertation Process in Counselor Education.” Five principles for how to support dissertation completion effectively emerged from their research: (a) program mechanics with structured curriculum and processes with a dissertation focus from the outset; (b) a supportive environment with solid mentoring and feedback tailored to the style and needs of the individual student; (c) selecting and working with cooperative, helpful, and productive dissertation committee members; (d) intentionality in developing a scholar identity to include a research and methodological focus; and (e) regular accountability and contact in supporting a student’s steady progress toward the final dissertation writing and defense. Programs attentive to all five factors cannot guarantee dissertation completion on time, but they can certainly increase the probability of student success.

Gaining University Administrator Support

It is critical to have the support of university administrators who set priorities, allocate resources, and ultimately determine if a new degree program proposal lives or dies. Administrators who give their stamp of approval and invest resources will want to see evidence of success to commit to ongoing support. The seventh and final theme entails how to collaborate with administrators in supporting our doctoral programs. Scherer et al. (2020) provide keen analysis and insights into this issue in “Gaining Administrative Support for Doctoral Programs in Counselor Education.” They caution faculty that before embarking down the path of program development, there are many issues involved that faculty generally are not accustomed to considering.

First, higher education administration has a certain amount of politics involved, and faculty need to remain aware of the political minefields they may be entering. Understanding and navigating university organizational dynamics and cultivating buy-in from the broader university constituency is a critical skill. Second, the payoff for such an endeavor may not be self-evident, so faculty must demonstrate how a new doctoral program fits the university’s mission, helps local communities and the profession, and ultimately raises the university’s prestige and reputation. Third, program leadership must establish credibility and gain the administration’s confidence that counseling faculty have the intellectual capital and expertise to educate, train, and graduate high-quality doctoral graduates. This article is an essential read for anyone planning to start or revitalize a program.

Future Directions

The 14 studies contained in this special issue represent a vital contribution to doctoral counselor education, yet important questions remain. We highlight four important directions to help guide future research.

First, there is a need to promote a more focused, systematic, ongoing agenda for the scholarship of doctoral counselor education. This special issue is an important first step, but leadership is needed to continue the effort. It is unclear how stakeholders such as CACREP, professional associations, doctoral program faculty, and editorial boards of peer-reviewed journals may build on and initiate efforts to promote scholarship in this area. It may be that a unified and intentional approach is key to ensuring that research proceeds in a strategic and methodical fashion and moves the profession steadily forward.

Second, we need to better understand how the advent of online programs is shaping the landscape of doctoral education. Based upon the findings in this special issue, we know residential doctoral programs are not distributed evenly across the country, but does it really matter if there is now an online option for all students? It is important to understand how potential employers now perceive online graduates and how potential doctoral students perceive online programs as acceptable alternatives to a brick-and-mortar campus experience.

Third, the important work of this journal’s special issue in promoting high-quality outcomes in doctoral education should continue. Current descriptions of quality rely heavily on expert faculty opinions and judgments. We need to evaluate how these suggested best practices actually translate into more empirical outcomes, such as student satisfaction and retention, dissertation pass rates, job-seeking success, and post-degree productivity. Future studies can also benefit from larger sample sizes and broader representation from more programs to increase the generalizability of findings.

Finally, the work of better understanding and improving the student experience—especially that of students from culturally diverse backgrounds and identities—is critical. This special issue strikes a good balance with six student-oriented articles and two focused on helping programs recruit, retain, and support students from underrepresented minority backgrounds, but we have more yet to do. The work must continue until the words “underrepresented minority” are a thing of the past and we have doctoral student cohorts that truly reflect the diversity of our world.

Conclusion

As we conclude our introduction to this special issue on doctoral education, we are grateful for the contribution of the 14 studies and their authors. We now know more about the state of research in the profession, potential geographic gaps in program coverage, how to define and improve program quality, strategies to gain administrative support, and most importantly how to best increase diversity and promote student success. We hope that the combined insights in the assembled studies will help inform CES doctoral programming and contribute to a focused research agenda for years to come. We look forward to revisiting this first CES special issue in the future to observe its influence and the positive outcomes we trust will follow.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Adkinson-Bradley, C. (2013). Counselor education and supervision: The development of the CACREP doctoral standards. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00069.x

Baker, D. B., & Benjamin, L. T., Jr. (2000). The affirmation of the scientist-practitioner: A look back at Boulder. American Psychologist, 55(2), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.2.241

Baltrinic, E. R., & Suddeath, E. G. (2020). A Q methodology study of a doctoral counselor education teaching instruction course. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 472–487. https://doi.org/10.15241/erb.10.4.472

Bodenhorn, N., Hartig, N., Ghoston, M. R., Graham, J., Lile, J. J., Sackett, C., & Farmer, L. B. (2014). Counselor education faculty positions: Requirements and preferences in CESNET announcements 2005-2009. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 6(1). https://repository.wcsu.edu/jcps/vol6/iss1/2

Branco, S. F., & Davis, M. (2020). The Minority Fellowship Program: Promoting representation within counselor education and supervision. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 603–614. https://doi.org/10.15241/sfb.10.4.603.

Brown, C. L., Vajda, A. J., & Christian, D. D. (2020). Preparing counselor education and supervision doctoral students through an HLT lens: The importance of research and scholarship. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 501–516. https://doi.org/10.15241/clb.10.4.501.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (n.d.). Find a program. Retrieved November 23, 2019, from https://www.cacrep.org/directory

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2013). 2012 annual report. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CACREP-2012-Annual-Report.pdf

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2019). Annual report 2018. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CACREP-2018-Annual-Report.pdf

DeCino, D. A., Waalkes, P. L., & Dalbey, A. (2020). “They stay with you”: Counselor educators’ emotionally intense gatekeeping experiences. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 548–561. https://doi.org/10.15241/dad.10.4.548.

Dipre, K. A., & Luke, M. (2020). Relational cultural theory–informed advising in counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.15241/kad.10.4.517.

Field, T. A., Snow, W. H., & Hinkle, J. S. (2020). The pipeline problem in doctoral counselor education and supervision. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 434–452. https://doi.org/10.15241/taf.10.4.434

Freeman, B., Woodliff, T., & Martinez, M. (2020). Teaching gatekeeping to doctoral students: A qualitative study of a developmental experiential approach. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 562–580.

https://doi.org/10.15241/bf.10.4.562.

Ghoston, M., Grimes, T., Grimes, J., Graham, J., & Field, T. A. (2020). Faculty perspectives on strategies for successful navigation of the dissertation process in counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.15241/mg.10.4.615.

Ju, J., Merrell-James, R., Coker, J. K., Ghoston, M., Casado Pérez, J. F., & Field, T. A. (2020). Recruiting, retaining, and supporting students from underrepresented racial minority backgrounds in doctoral counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 581–602. https://doi.org/10.15241/jj.10.4.581.

Kaplan, D. M., Tarvydas, V. M., & Gladding, S. T. (2014). 20/20: A vision for the future of counseling: The new consensus definition of counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 366–372.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00164.x

Kaslow, N. J., & Johnson, W. B. (Eds.). (2014). The Oxford handbook of education and training in professional psychology. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199874019.001.0001

Kent, V., Runyan, H., Savinsky, D., & Knight, J. (2020). Mentoring doctoral student mothers in counselor education: A phenomenological study. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 532–547. https://doi.org/10.15241/vk.10.4.532.

Limberg, D., Newton, T., Nelson, K., Barrio Minton, C. A., Super, J. T., & Ohrt, J. (2020). Research identity development of counselor education doctoral students: A grounded theory. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 488–500. https://doi.org/10.15241/dl.10.4.488.

Litherland, G., & Schulthes, G. (2020). Research focused on doctoral-level counselor education: A scoping review. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.15241/gl.10.4.414

Magnuson, S., Norem, K., & Haberstroh, S. (2001). New assistant professors of counselor education: Their preparation and their induction. Counselor Education and Supervision, 40(3), 220–229.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01254.x

Neale-McFall, C., & Ward, C. A. (2015). Factors contributing to counselor education doctoral students’ satisfaction with their dissertation chairperson. The Professional Counselor, 5(1), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.15241/cnm.5.1.185

Preston, J., Trepal, H., Morgan, A., Jacques, J., Smith, J. D., & Field, T. A. (2020). Components of a high-quality doctoral program in counselor education and supervision. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.15241/jp.10.4.453

Purgason, L. L., Avent, J. R., Cashwell, C. S., Jordan, M. E., & Reese, R. F. (2016). Culturally relevant advising: Applying relational-cultural theory in counselor education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12101

Scherer, R., Moro, R., Jungersen, T., Contos, L., & Field, T. A. (2020). Gaining administrative support for doctoral programs in counselor education. The Professional Counselor, 10(4), 632–647.

https://doi.org/10.15241/rf.10.4.632.

Stricker, G., & Trierweiler, S. J. (2006). The local clinical scientist: A bridge between science and practice. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, S(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.S.1.37

Waalkes, P. L., Benshoff, J. M., Stickl, J., Swindle, P. J., & Umstead, L. K. (2018). Structure, impact, and deficiencies of beginning counselor educators’ doctoral teaching preparation. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12094

West, J. D., Bubenzer, D. L., Brooks, D. K., Jr., & Hackney, H. (1995). The doctoral degree in counselor education and supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(2), 174–176.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01846.x

Zimpfer, D. G., Cox, J. A., West, J. D., Bubenzer, D. L., & Brooks, D. K., Jr. (1997). An examination of counselor

preparation doctoral program goals. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36(4), 318–331.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1997.tb00398.x

William H. Snow, PhD, is a professor at Palo Alto University. Thomas A. Field, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, ACS, LPC, LMHC, is an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Medicine. Correspondence may be addressed to William Snow, 1791 Arastradero Road, Palo Alto, CA 94304, wsnow@paloaltou.edu.

Dec 16, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 4

Jennie Ju, Rose Merrell-James, J. Kelly Coker, Michelle Ghoston, Javier F. Casado Pérez, Thomas A. Field

Few models exist that inform how counselor education programs proactively address the gap between diverse student needs and effective support. In this study, we utilized grounded theory qualitative research to gain a better understanding of how 15 faculty members in doctoral counselor education and supervision programs reported that their departments responded to the need for recruiting, retaining, and supporting doctoral students from underrepresented racial minority backgrounds. We also explored participants’ reported successes with these strategies. A framework emerged to explain the strategies that counselor education departments have implemented in recruiting, supporting, and retaining students from underrepresented racial minority backgrounds. The main categories identified were: (a) institutional and program characteristics, (b) recruitment strategies, and (c) support and retention strategies. The latter two main categories both had the same two subcategories, namely awareness and understanding, and proactive and intentional efforts. The latter subcategory had three subthemes of connecting to cultural identity, providing personalized support, and faculty involvement.

Keywords: underrepresented racial minority, recruitment, retention, counselor education, doctoral

For the past several years, doctoral counselor education and supervision (CES) programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) have experienced a greater enrollment of students from diverse backgrounds (CACREP, 2014, 2015). According to the CACREP Vital Statistics report (2018), two-fifths of doctoral students have a diverse racial or ethnic identity. This stands in contrast to the less than 30% of full-time faculty in CACREP-accredited programs who identify as having a diverse racial or ethnic identity. In 2012, the total doctoral-level enrollment in CACREP institutions was 2,028, where 37% of the students were from racially or ethnically diverse backgrounds (CACREP, 2014). Enrollment increased to 2,561 in 2017, with 1,016 students from racially or ethnically diverse communities, which translates to 39.7% of total enrollment (CACREP, 2018).

Accompanying this trend is a growing awareness that diverse doctoral students in counseling and related disciplines are not receiving adequate support and preparation to succeed (Barker, 2016; Henfield et al., 2011; Hollingsworth & Fassinger, 2002; Zeligman et al., 2015). CACREP-accredited programs are charged with making a “continuous and systematic effort to attract, enroll, and retain a diverse group of students and to create and support an inclusive learning community” (CACREP, 2016, section 1.K.). Yet few models exist that inform how CES programs proactively address the gap between diverse student needs and effective support. Literature is limited on this topic. Little is known about effective and comprehensive structures for recruiting, supporting, and retaining CES doctoral students from underrepresented minority (URM) backgrounds that take into consideration CACREP standards, student needs, economics, sociocultural barriers, and student opportunities.

In this study, we used Federal definitions of URM status in higher education to guide our inquiry. A section of the U.S. Code pertaining to minority persons provides the following definition for minority, and it is the one we chose to use in our study: “American Indian, Alaskan Native, Black (not of Hispanic origin), Hispanic (including persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central or South American origin), Pacific Islander, or other ethnic group” (Definitions, 20 U.S.C. 20 § 1067k, 2020). This definition is important to higher education, as it is used by institutions to allocate funding for URM students. We note here that cultural diversity also spans other aspects of minority status, such as gender identity, sexual/affectional identity, and ability/disability status, among others. We restricted the focus of this study to exploring racial identity pertinent to URM status, following the U.S. Code definition.

Recruitment of Doctoral Students From URM Backgrounds

Understanding the diversification of doctoral students in CES programs begins by first considering effective methods for recruitment used by those programs. Recruitment of CES doctoral students of color may necessitate intentional and active approaches, such as building personal connections in the community and family (Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017; McCallum, 2016). CES doctoral programs might consider recruitment not as a yearly endeavor, but a long-term, day-to-day strategy. Early exposure, responsiveness to student needs (e.g., financial needs), commitment to diversity (e.g., hiring and retaining faculty members from diverse backgrounds), community relationships, and program location have all been identified as important factors to consider in the extant literature.

Early Exposure and Recruitment

Programs can promote more representative recruitment through earlier exposure to the disciplinary field and community connections (Grapin et al., 2016; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017; McCallum, 2016). Introducing the possibility of pursuing doctoral studies in CES during the high school and undergraduate experience can increase student familiarity with the profession and may promote their long-term attention to the field (Luedke et al., 2019; McCallum, 2016). McCallum (2015, 2016) found that early familial and social messages about the low viability of doctoral studies was a deterrent among African American students and that mentorship and exposure to doctoral careers by professionals can help renew interest. Many undergraduate students from culturally diverse backgrounds lack opportunities to learn and develop ownership of doctoral-level professions and in some cases lack knowledge that those professions even exist (Grapin et al., 2016; Luedke et al., 2019).

Responsiveness to Needs and Commitment to Diversity

To successfully recruit doctoral students from culturally diverse backgrounds, CES programs need to be responsive to potential students’ needs. In fact, a program’s commitment to diversity and the demonstration of that commitment through student and faculty representation have been found to be highly influential factors in applicants’ decisions to enter a doctoral program (Foxx et al., 2018; Grapin et al., 2016; Zeligman et al., 2015). An additional aspect of this responsiveness in recruitment is the program’s ability to ensure and provide financial support to incoming students (Dieker et al., 2013; Proctor & Romano, 2016). Given the unique barriers experienced by culturally diverse communities throughout the educational system, doctoral programs can be prepared to compensate for some of these obstacles through financial and academic support.

Community Relationships and Program Location

In keeping with recruitment as a long-term endeavor, research has found that community relationships and program location are essential when recruiting doctoral students from culturally diverse backgrounds (Foxx et al., 2018; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017). CES programs can look to build relationships with their local culturally diverse communities and recruit from those communities, rather than looking nationally for their doctoral students (Foxx et al., 2018; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017). Proctor and Romano (2016) found that proximity to representative communities and applicants’ support systems had a significant impact on their decision to enter doctoral programs. Community connections also offered more opportunities to clarify admission requirements for interested students, a barrier for many first-generation students (Dieker et al., 2013; Hipolito-Delgado et al., 2017).

Support and Retention of Culturally Diverse Doctoral Students

Once admitted to a doctoral program in CES, program faculty are required by the CACREP (2015) standards to make a continuous and systematic effort to not only recruit but also to retain a diverse group of students. To do so, faculty should be attentive to both common and unique personal and social challenges, experiences of marginalization and isolation, and acculturative challenges that students from URM backgrounds may face.

Personal and Social Challenges

Students from URM backgrounds have faced ongoing challenges with their ability to establish a clear voice and ethnic identity in predominately Euro-American CES programs (Baker & Moore, 2015; González, 2006; Guillory, 2009; Lerma et al., 2015). This phenomenon has been written about for decades (Lewis et al., 2004). Lewis et al. (2004) described the lived experiences of African American doctoral students at a predominantly Euro-American, Carnegie level R1 research institution. Key themes that emerged included feelings of isolation, tokenism, difficulty in developing relationships with Euro-American peers, and learning to negotiate the system. Further review of the literature found consistent challenges across diverse students, especially with establishing voice and ethnic identity (Baker & Moore, 2015; González, 2006; Lerma et al., 2015). Guillory (2009) noted that the level of difficulty American Indian students will face in college depends in large measure on how they see and use their ethnic identity. Utilizing a narrative inquiry approach, Hinojosa and Carney (2016) found that five Mexican American female students experienced similar challenges in maintaining their ethnic identities while navigating doctoral education culture.

Challenges of Marginalization and Isolation

Marginalization and isolation were additional common themes across diverse groups. Blockett et al. (2016) concluded that students experience marginalization in three areas of socialization, including faculty mentorship, professional involvement, and environmental support. Other researchers have also concluded that both overt and covert racism is a contributing factor to marginalization in the university culture (Behl et al., 2017; González, 2006; Haizlip, 2012; Henfield et al., 2013; Interiano & Lim, 2018; Protivnak & Foss, 2009). Study themes also indicated that students often expressed frustration from tokenism in which they felt expectations to represent the entire race during doctoral programs (Baker & Moore, 2015; Haizlip, 2012; Henfield et al., 2013; Lerma et al., 2015; Woo et al., 2015). Henfield et al. (2011) investigated 11 African American doctoral students and found that the challenges included negative campus climates regarding race, feelings of isolation, marginalization, and lack of racial peer groups during their graduate education. Similarly, using critical race theory to examine how race affects student experience, Henfield et al. (2013) found African American students experienced a lack of respect from faculty because of their racial and ethnic differences. Students who had previously studied at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) or Hispanic serving institutions (HSIs) reported that the lack of racial/ethnic diversity representation during doctoral study in predominantly White institutions (PWIs) contributed to their experience of stress, anxiety, and irritation (Henfield et al., 2011, 2013).

Culture and Acculturation Challenges

Collectivity and community seem to be consistent values that doctoral students from URM backgrounds have expressed as missing or not understood by faculty (González, 2006; Lerma et al., 2015). For example, faculty may not understand familia, a Latinx student’s obligation to family (González, 2006; Lerma et al., 2015). Several authors have reported that culturally diverse doctoral students experience difficulty adjusting to a curriculum or program that values a Eurocentric individualist form of counseling (Behl et al., 2017; Interiano & Lim, 2018; Woo et al., 2015).

International students also experience similar anxiety and stress during their doctoral studies in the United States. In addition to adjusting to speaking and writing in a language that may not be their primary language, their supervision skills and clinical abilities can be questioned by Euro-American supervisees despite international students having advanced training and supervisory status (Behl et al., 2017). Interiano and Lim (2018) used the term “chameleonic identity” (p. 310) to describe foreign-born doctoral students’ attempts to adapt to the Euro-American cultural context of their CES programs. They posited that international students experienced a sense of conflict, loss, and grief associated with the pressure to adopt cultural norms embedded in Euro-American counseling and higher education in the United States.

Strategies to Support and Retain Culturally Diverse Doctoral Students

To address these stressors and barriers to persistence in doctoral studies, faculty members can employ several strategies to support and retain students from culturally diverse backgrounds, such as mentorship, advising, increasing faculty diversity, understanding students’ cultures, and offering student support services.

Mentorship

Some scholars recommend intentional utilization of mentorship as a strategy for improving retention and graduation rates of diverse students in higher education (Evans & Cokley, 2008; Rogers & Molina, 2006). Chan et al. (2015) defined mentoring relationships as a “one-to-one ongoing connection between a more experienced member (mentor) and less experienced member (protégé) that is aimed to promote the professional and personal growth of the protégé through coaching, support and guidance” (p. 593). Chan and colleagues added that mentoring can involve transferring needed information, feedback, and encouragement to the protégé as well as providing emotional support.

Zeligman and colleagues (2015) indicated that mentoring impacts both the recruitment and the retention of doctoral students from URM backgrounds. The quality and significance of mentoring relationships and participants’ connection with faculty members during a doctoral program seems to influence choice in continuing doctoral study for URM students (Baker & Moore, 2015; Protivnak & Foss, 2009). Blackwell (1987) noted that the most powerful predictor of enrollment and graduation of African American students at a professional school was the presence of an African American faculty member serving as the student’s mentor.

Although a powerful tool for recruiting and retaining diverse doctoral students, mentoring can also create retention issues if inadequate or problematic. Students may receive ambiguous answers to advising questions and may not receive support when life circumstances interfere with study (Baker & Moore, 2015; Henfield et al., 2013; Interiano & Lim, 2018). In such situations, some students may seek other faculty mentors within the department (Baker & Moore, 2015; Henfield et al., 2013; Interiano & Lim, 2018) or may specifically establish mentoring relationships with faculty from diverse cultural backgrounds to receive greater support for their experience of being a person of color (González, 2006; Woo et al., 2015; Zeligman et al., 2015). Diverse students may also seek mentors from outside of their doctoral program. Woo and colleagues (2015) found that international students selected professional counseling mentors from their home community that they considered to be caring and nonjudgmental of their doctoral work in comparison to faculty supervisors they felt were neither culturally sensitive nor supportive of international students.

Because of an existing disparity in the availability of African American counselor educators and supervisors who can serve as mentors to African American doctoral counseling students, Euro-American counselor educators and supervisors can provide mentorship support to underrepresented African American doctoral students. Brown and Grothaus (2019) conducted a phenomenological study with 10 African American doctoral counseling students. The authors found that trust was a primary factor in establishing successful cross-racial relationships, and that African American students could benefit from “networks of privilege” (p. 218) during cross-racial mentoring. The authors also found that if issues of racism and oppression are not addressed, it can interfere with establishing mentoring relationships.

Establishing same-race, cross-race, and/or cultural community affiliations provides support to culturally diverse doctoral students. In addition, increasing faculty diversity can be a viable measure to support and retain diverse doctoral students.

Increasing Faculty Diversity

The presence of diverse faculty members in CES has been discussed in the literature as a positive element in the recruitment, support, and retention of diverse doctoral students (Henfield et al., 2013; Lerma et al., 2015; Zeligman et al., 2015). Henfield and colleagues (2013) emphasized the need to proactively recruit and retain African American CES faculty to attract, recruit, and retain African American CES doctoral students. Recruiting and retaining faculty members from URM backgrounds requires intentional effort. Ponjuan (2011) suggested the development of mentoring policies that establish Hispanic learning communities and improve overall departmental climate as efforts to help increase the number of Latinx faculty at an institution. The next section discusses the relational significance of having counselor educator mentors who share cultural backgrounds and worldviews.

Understanding of Students’ Culture

Lerma et al. (2015) recommended that doctoral faculty in CES programs be responsive to both the professional and personal development of their students. One area of dissonance for doctoral students from URM backgrounds involves differences in cultural worldview. Marsella and Pederson (2004) posited that “Western psychology is rooted in an ideology of individualism, rationality, and empiricism that has little resonance in many of the more than 5,000 cultures found in today’s world” (p. 414). Ng and Smith (2009) found that international counselor trainees, particularly those from non-Western nations, struggle with integrating Eurocentric theories and concepts into the world they know. This presents opportunities for counselor educators to intentionally search for appropriate pedagogies and to critically present readings and other media that portray the multicultural perspective (Goodman et al., 2015).

Counseling departments can promote, facilitate, and value a multicultural orientation when focusing on student success and development. Lerma et al. (2015) and Castellanos et al. (2006) emphasized the need to understand the importance of family and peer support among Latinx students and faculty, specifically in recreating familia in the academic environment to help increase resilience. When working with African American students, Henfield et al. (2013) recommended that faculty should possess an understanding and respect of African American culture and be more “cognizant of how a history of oppression may influence students’ perception, behavior, and nonbehavior” (p. 134). Faculty members should also possess an understanding of student financial difficulties and potential knowledge gaps in preparation for graduate school (González, 2006; Zeligman et al., 2015).

Student Support Services

Another effective area of support for doctoral students from diverse backgrounds is student-based services. These services include broader institutionally based resources, student-guided groups or activities, and community-based efforts. Institutional resources that seem to hold promise in increasing support for and the potential success of diverse students include race-based organizations (Henfield et al., 2011). Peer support has been consistently identified as an important factor in doctoral student persistence (Chen et al., 2020; Henfield et al., 2011; Rogers & Molina, 2006). Student-centered organizations can effectively provide a sense of belonging and an environment that facilitates peer support among those with shared interests on campus (Rogers & Molina, 2006). Henfield et al. (2011) found that African American students sought collaborative support through race-based campus organizations and with students who share similar backgrounds and interests. Multicultural-based, student-centered organizations and events are resources that institutions utilize as active support for multicultural individuals that contribute to “sustaining diverse students to reach the finish line of graduation with a strong foundation from which to launch their counseling career” (Chen et al., 2020, p. 10).

Chen et al. (2020) and Behl et al. (2017) have both reported that writing centers are an important support for international students as well as students from refugee, immigrant, and underprivileged communities. Ng (2006) reported that counseling students from non–English-speaking countries often experience challenges related to English proficiency. Chen et al. (2020) added that tutoring in writing is critical for students who come from cultures that are unaccustomed to the formal use of writing styles (e.g., APA style). Furthermore, helping international students understand classroom norms and culture through an orientation as part of the onboarding process can be a preventive support (Behl et al., 2017).

Purpose of the Present Study

The CACREP standards have created expectations and requirements for counseling programs to recruit, retain, and support students from diverse backgrounds. There now exists a wide swath of literature that has reported a variety of efforts toward these goals (Baker & Moore, 2015; Evans & Cokley, 2008; Rogers & Molina, 2006; Woo et al., 2015). Yet at the time of writing, there is not a clearly articulated path for CES programs to follow with regard to these efforts. For example, there is currently no information available regarding which strategies are more successful or easier to implement than others. This study aimed to address this gap in knowledge for how to attract, support, and retain students from diverse backgrounds in CES doctoral programs. The purpose of our study was to explore: (a) strategies doctoral programs use to recruit, retain, and support underrepresented doctoral students from diverse backgrounds, and (b) the level of success these programs have had with their implemented strategies.

Methodology

Throughout the study, we were grounded by a shared belief in constructivist philosophy that participants’ realities are socially co-constructed, and therefore, all responses are valued regardless of frequency. From this philosophical position, we chose to approach the topic using a qualitative framework (Lincoln & Guba, 2013). Grounded theory was selected because it utilizes a systematic and progressive gathering and analysis of data, followed by grounding the concepts in data that accurately describe the participants’ own voices (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015). This approach allows the integration of both the art and science aspects of inquiry while supporting systematic development of theoretical constructs that promote richer comprehension and explanation of social phenomena (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015). Through the grounded theory approach, we hoped to establish an emergent framework to explain practice and provide recommendations for CES programs striving to support diverse doctoral students.

This study was part of a larger comprehensive qualitative study based on the basic qualitative research design described by Merriam and Tisdell (2016) that examined a series of issues pertinent to doctoral counselor education. Preston et al. (2020) described the larger qualitative project that involved the collection and analysis of in-depth qualitative interviews with 15 doctoral-level counselor educators. This article focuses on the analysis of interview data gathered through two of the interview questions: 1) Which strategies has your program used to recruit underrepresented students from diverse backgrounds? How successful were those? and 2) Which strategies has your program used to support and retain underrepresented students from diverse backgrounds? How successful were those?

Researcher Positioning, Role, and Bias

The last author utilized the etic position, which is through the perspective of the observer, to conduct all interviews with selected participants. Approaching the interview process around the topic of doctoral-level counselor education through the etic status was important because the author had not worked in a doctoral-level CES program previously but has been a member of the counselor education community.

The situational context was composed of the researchers’ and participants’ experiences and perceptions, the social environment, and the interaction between them (Ponterotto, 2005). Therefore, we engaged in reflexivity to increase self-awareness of biases related to this topic (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). This required continual examination of the potential influence that identified biases may have on the research process. In keeping with the standard of reflexivity, we recorded our personal experiences as they related to the research questions with the use of memoing to bracket potential biases throughout the coding and analysis process.

All members of the research team are from CACREP-accredited institutions in the Western and Eastern parts of the United States. The coding team consisted of the first four authors. The fifth author contributed to writing the manuscript, and the sixth author conducted the interviews as part of the larger study and assisted in writing sections of the methodology. All four coding team members had previously been doctoral students in a CES program, though only one of the coding team members had ever worked in a CES doctoral program as a full-time faculty member. This person thus had emic positioning, while other team members held etic positioning.

Four of the five members of the coding team were from diverse backgrounds themselves and were influenced by their personal experiences as doctoral students. Two members of the coding team identified as cisgender, heterosexual African American females. One member identified as a cisgender, heterosexual Asian American female and another as a cisgender, heterosexual Euro-American female. The coding team members were aware of potential biases around expectations toward the programs discussed in the transcripts and recognized the need to closely examine personal perceptions and understanding of the interview data.

Two coding team members observed the lack of racial/ethnic diversity at the counseling programs where they currently work. They experienced Eurocentric, non–culturally responsive methods of support and development that led them to recognize the potential bias of shared experience with multicultural participants. One coding team member was Euro-American and was a part of an all Euro-American doctoral cohort. The program they attended had an all Euro-American faculty and she wondered whether the predominantly Euro-American participants in this study had an understanding of the challenges of diverse students. Having taught in doctoral programs, this researcher was aware of potential biases around types of universities that might be successful in recruiting but less so in retaining diverse students.

Participants

Participants were selected based on the following study design criteria: 1) current full-time core faculty members in CES, and 2) currently working in a doctoral-level CES program that is accredited by CACREP. At the time of writing, there were 85 CACREP-accredited doctoral CES programs in the United States (CACREP, 2019). Purposeful sampling was used to identify and recruit participants who had experiences working in doctoral-level counselor education (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Information-rich cases were sought to understand the phenomenon of interest.

Maximum variation sampling was also employed for the purposes of understanding the perspectives of counselor educators from diverse backgrounds with regard to demographic characteristics and program characteristics and to avoid premature saturation (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Based on the belief that counselor educator perspectives may differ by background, the research team used the following criteria to select participants: (a) racial and ethnic self-identification; (b) gender self-identification; (c) length of time working in doctoral-level CES programs; (d) Carnegie classification of the university where the participant was currently working (The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, 2019); (e) region of the counselor education program where the participant was currently working, using regions commonly defined by national counselor education associations and organizations; and (f) delivery mode of the counselor education program where the participant was currently working (e.g., in-person, online; Preston et al., 2020).

The 15 study participants belonged to separate doctoral-level CES programs, with no more than one participant representing each program. The sample was composed of 11 participants (73.3%) who self-identified as White, with multiracial/multiethnic (n = 1, 6.7%), African American (n = 1, 6.7%), Asian (n = 1, 6.7%), and Latinx ethnic backgrounds (n = 1, 6.7%) also represented. Seven participants self-identified as female (46.7%), eight participants as male (53.3%), and none identified as non-binary or transgender. The majority of participants identified as heterosexual (n = 14, 93.3%), with one participant (6.7%) identifying as bisexual.

Participants’ experience as faculty members averaged full-time work for 19.7 years (SD = 9.0 years) and a median of 17 years, with a range from 4 to 34 years. For most of those years, participants worked in doctoral-level CES programs (M = 17.3 years, SD = 9.2 years, Mdn = 16 years), ranging from 3 to 33 years. More than half of participants (n = 9, 60%) spent their entire careers working in doctoral-level CES programs. Geographic distribution of the programs where participants worked were as follows: eight belonged to the Southern region (53.3%); two each (13.3%) belonged to the North Atlantic, North Central, and Western regions; and one program (6.7%) belonged to the Rocky Mountain region. Twelve participants (80%) were working in brick-and-mortar programs, and three participants (20%) were working in online or hybrid programs. With regard to Carnegie classification representation, nine (60%) were working at Doctoral Universities – Very High Research Activity (i.e., R1) institutions, two (13.3%) were working at Doctoral Universities – High Research Activity (i.e., R2) institutions, and four (26.7%) were working at universities with the Master’s Colleges and Universities: Larger Programs designation (The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, 2019; Preston et al., 2020).

Procedure

After receiving approval from the last author’s IRB, the last author used the CACREP (2018) website directory to identify and recruit doctoral-level counselor educators who worked at the CACREP-accredited CES programs. Recruitment emails were sent to one faculty member at each of the 85 accredited programs. Fifteen of the 34 faculty (40% response rate) who responded were selected to participate on the basis of maximal variation.

Interview Protocol

Each interview began with demographic questions that addressed self-identified characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual/affectional orientation, years as a faculty member, years working in doctoral-level CES programs, number of doctoral programs the participant had worked in, and regions of the programs in which the counselor educator had worked. A series of eight in-depth interviews followed to address the research questions of the larger qualitative study. Interview questions developed in accordance with Patton’s (2014) guidelines were open-ended, as neutral as possible, avoided “why” questions, and were asked one at a time in a semi-structured interview protocol, with sparse follow-up questions salient to the main questions to ensure understanding of participant responses. Adhering to the interview protocol as outlined in Appendix A helped to ensure that data was gathered for each research question to the highest extent possible. Participants received the interview questions ahead of time upon signing the informed consent agreement. A pilot of the interview protocol was conducted with a faculty member in a doctoral-level CES program prior to commencing the study.

The interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were recorded using the Zoom online platform. One exception was an interview that occurred in-person during a professional conference and thus was recorded via a Sony digital audio recorder. All demographic information and recordings were assigned an alphabetical identifier known only to the last author and were blinded to subsequent transcribers and coders.

Data Analysis

Data analysis, as outlined by Corbin and Strauss (2015), employs the techniques of coding interview data to derive and develop concepts. In the initial step of open coding, the primary task is to “break data apart and delineate concepts to stand for blocks of raw data” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 197). During this step, the coding team sought to identify a list of significant participant statements about how they and their department perceive, value, and experience the responsibility of recruiting, retaining, and supporting underrepresented cultural groups. We met to code the first three of 15 transcripts together via Zoom video platform. The task of identifying codes included searching for data that was salient to the research questions and engaging in constant comparison until reaching saturation (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). We maintained a master codebook of participant statements that the team decided were relevant, then added descriptions and categories to the codes. Utilizing this same strategy, the remaining 12 transcripts were coded in dyads to make sure the coding team was not overlooking pertinent information.

When discrepancies occurred, the coding team utilized the following methods to resolve them:

(a) checking with each other for clarification and understanding of each person’s view on the code, (b) reviewing previous and subsequent lines for context, (c) slowing down the pace of coding to allow space for reflection on the team members’ thoughts and feeling about a code, (d) considering the creation of a new code if one part of the statement added new data that was not covered in the first part of the statement, and (e) referring back to the research questions to determine relevance of the statement. Discrepancies in coding were questions around statements that: (a) were vague, (b) contained multiple codes, (c) were similarly phrased, (d) reflected a wish rather than an action on the part of the program, and (e) presented interesting information about the participant’s program but did not address the research question.

The subsequent step of axial coding involved the task of relating concepts and categories to each other, from which the contexts and processes of the phenomena emerge (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). The researchers then framed emerging themes and concepts to identify higher-level concepts and lower-level properties as well as delineated relationships between categories until saturation was reached. In the step of selective coding, the researchers engaged in an ongoing process of integrating and refining the framework that emerged from categories and relationships to form one central concept (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Trustworthiness

Standards of trustworthiness were achieved by incorporating procedures as outlined by Creswell et al. (2007) and Merriam and Tisdell (2016). The strategies included enhancing credibility through clarification of researcher bias to illustrate the researchers’ position as well as identifying a priori biases and assumptions that could potentially impact our inquiry. In addition, the research team members were from different counselor education programs, which contributed to moderating bias in coding and analysis. In an attempt to avoid interpreting data too early during the coding process, the researchers used emergent, in vivo, verbatim, line-by-line open coding. Furthermore, the interviewer intentionally chose not to participate in coding the data in order to minimize bias through being too close to the data. To promote consistency, the last author clearly identified and trained research teams associated with the larger study. The last author also used member checking and kept an audit trail of the process to enhance credibility. Purposive sampling and thick description were used to ensure adequate representation of perspectives and thus strengthen the transferability and dependability qualities of the study (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016).

Results

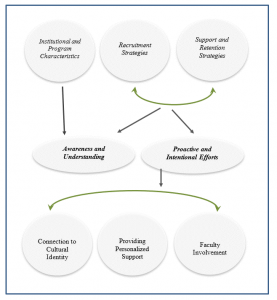

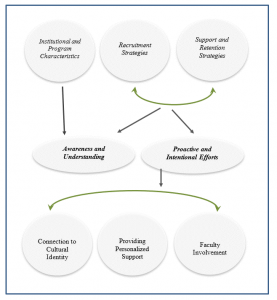

Implementing strategies that make a difference was the central concept in describing the process of CES faculty participants’ experience with recruiting and retaining diverse doctoral students. These strategies refer to programmatic steps that counselor educator interview participants had found to be effective in the recruitment, support, and retention of culturally diverse doctoral students. This central concept was composed of three progressive and interconnected categories, each with its own subcategories, properties, and accompanying dimensions. These three categories were institutional and program characteristics, recruitment strategies, and support and retention strategies. The three major categories shared the subcategory of awareness and understanding, while the recruitment strategies and support and retention strategies categories shared the subcategory of proactive and intentional efforts. The conceptual diagram of these categories and subcategories is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Conceptual Diagram of Strategies That Make a Difference in Recruiting and Supporting

Culturally Diverse Doctoral Students

Institutional and Program Characteristics

The category institutional and program characteristics refers to features that are a part of program identity. This category was significant, as it represents the backdrop for a unique set of conditions in which the participants experienced the limitations as well as strengths of the program environment. Institutional and program characteristics may be part of the institution’s natural setting that the faculty participant had little control over, such as geographic location, institution size, institution reputation, tuition cost, or demographic composition of the area in which the program was located. At times, these factors were helpful for recruitment purposes. One participant described how the program’s geographic location positively impacted the recruitment of prospective students, including diverse students: “We are the only doctoral program in the state, so I think that carries some clout.” Another participant added, “A lot of it is financial . . . They largely choose programs because they are geographically convenient, so they can work or be close to family. So, their choice is largely guided by economic and geographic factors.”

Institutional and program characteristics also included factors that influenced support and retention of diverse students through their doctoral journey. Characteristics mentioned as either a hindrance or a support for diverse students included: (a) presence of diverse faculty, visual representation, and student body; (b) supportive environment for diverse students; (c) faculty attitudes and dispositions which create either a welcoming or hostile sociocultural climate; (d) fellowship or scholarship monies intended for diverse students; (e) evidence of valuing of and commitment to diversity; (f) multicultural and social justice focused activities; and (g) faculty who share common research interests with their students. From this list, it was evident that doctoral students seemed best supported by program qualities and actions that communicated a valuing of and commitment to diversity.

Awareness and Understanding

Participants indicated awareness that the context in which the institution and program exist presents as either a hindrance or a benefit to diversity. For example, geographic location and demographic composition of the locality can pose a barrier to recruitment as one participant expressed: “Our university itself is not going to attract people. It is a very White community.” This participant understands that this means the program will need to develop specific recruitment efforts to mitigate this potential barrier to “show students that this is a program that would be welcoming and take proactive steps to do that.”

Participants also indicated an awareness that students can sense whether diversity-related issues will be given priority. One participant stated, “Students are really astute about getting a sense for how committed a department is to diversity. So, having tangible evidence there is a willingness to commit to diversity at the faculty level is super important.” Another participant shared, “Our interview process is a barrier . . . There can be some privileged White males who are highly, highly confrontational, and I don’t think that’s an appropriate recruitment style for sending a welcoming message to minority candidates.”

Recruitment Strategies

The second major category identified in the data, recruitment strategies, pertains to the process of developing and implementing plans for the primary purpose of attracting individuals from diverse backgrounds to apply and enroll in the program. The recruitment strategies category is composed of two subcategories that are shared with the support and retention strategies, namely awareness and understanding and proactive and intentional efforts.

Awareness and Understanding

Participants shared a variety of responses regarding their awareness and understanding of the importance of creating a diverse learning community. Some participants reported that their departments proactively sought to recruit underrepresented students, whereas others acknowledged that their departments made no such attempt. At times, this was due to the structure of recruiting at the university: “Our program doesn’t necessarily get involved in admissions that much . . . We have an admissions team, and they have a whole series of strategies in place.” At other times, participants reported that their program was unintentional about recruiting diverse students: “We don’t have any good strategy particularly. It’s accident, dumb luck and accident.” One participant experienced distress and confusion because of their program’s perceived misalignment with CACREP standards: “These are key standards for programs, and one that programs have struggled with, and we certainly have too.”

Proactive and Intentional Efforts

Participants reported engaging social resources such as personal connections and networks to recruit diverse students. As one participant described, “Recruiting diverse students begins with personal networks. So, we use personal networks, professional networks, alumni network.” In addition to recruiting through alumni and professional organizations and conferences, participants found success through partnerships with community agencies as well as building relationships with HBCUs and HSIs. One participant captured the process this way: “It’s about maintaining relationships with graduates, with colleagues. We know, for us to diversify our student body, we cannot just look to the surrounding states to produce a diverse student body. We have to go beyond that.”

In addition to reaching out to master’s programs with sizable diverse student populations, one common strategic effort involved finding financial support for diverse doctoral students, from departmental, institutional, or external funding sources. One participant stated, “We also know in our program where the sources for funding underrepresented populations are; we know how to hook people into those sources of funding.” Another participant shared, “Our institutions have funding mechanisms, including some that are for historically marginalized populations or underrepresented populations. We have been successful in applying for those and getting those.”

Participants indicated a commitment to making changes to their typical mode of recruitment strategy and recognized that supporting diverse students required the implementation of strategies that differed from typical recruiting and retaining activities. Three subcategories that emerged as representing effective recruitment and support strategies were (a) connection to cultural identity, (b) providing personalized support, and (c) involvement of faculty.

Connection to Cultural Identity. Consistent with the literature, participants reported that students seemed drawn to programs that valued their cultural background and research interests associated with their identity. For example, participants reported that it was important to have faculty who are interested in promoting social justice and diversity and sharing similar research interests to their students. As one participant described: “The student picked us because we supported their research interest of racial battle fatigue.” This participant had shared with their prospective student that “I’m really excited about that [topic], and it overlaps with my own research in historical trauma with native populations.”

Personalized Support. Participants indicated personalized support was crucial to recruiting diverse students to their CES doctoral program. One participant reported that most of the diverse students who chose to attend their doctoral program typically shared the same response when asked about their choice: “Their comments are consistent. . . . They say, ‘We came and interviewed, and we met you, and we met the students, and we feel cared about.’”

Faculty Involvement. Third, faculty involvement was an essential component of proactive and intentional efforts. Faculty involvement seemed to take a variety of forms: (a) activities related to promoting multiculturalism and social justice, (b) engagement in diverse areas of the profession and representing the program well, and (c) advocating to connect potential students to external funding resources or professional opportunities. One participant explained faculty involvement this way: “An anchor person who strongly identifies not only with their own diversity, but also with a body of scholarship related to diversity.” Another participant shared, “Our faculty have had some nice engagements with organizations and research strands focused on multiculturalism and social justice issues.” These types of involvement made an impact on the impressions of prospective students from diverse backgrounds: “We have students who came to us and said, ‘I looked at the work your faculty were doing, I looked at what they said was important on the website, and it struck a chord with me.’”

Support and Retention Strategies

The third major category of support and retention strategies was characterized as responding to awareness and understanding of diverse students’ perspectives, experiences, and needs while enrolled in the doctoral program. Participants reported that faculty engaged in proactive and intentional efforts that integrated considerations for cultural identity, personalized support, and faculty involvement.

Awareness and Understanding

As with recruitment, participants reported that successful retention and support of enrolled doctoral students integrated considerations for the students’ cultural identity as well as values, needs, and interests that are a part of that identity. One participant described exploring missing aspects of each student’s experience for the purpose of providing effective support: “It’s super important on a very regular basis to sit down with students of color specifically and talk with them about what they’re not getting . . . those conversations really are key.” Often, these personalized conversations are part of a healthy, intentional mentoring relationship in which students are purposely paired with faculty who can understand their experience, support them in navigating professional organizations, and foster success in the program and in their future career. Two participants added that an effective support strategy involves reaching out and engaging in regular conversations about student struggles and experience with microaggressions, tokenism, or other socioemotional matters.