Mar 30, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 1

Eric R. Baltrinic, Randall M. Moate, Michelle Gimenez Hinkle, Marty Jencius, Jessica Z. Taylor

Mentoring is an important practice to prepare doctoral students for future graduate teaching, yet little is known about the teaching mentorship styles used by counselor educators. This study identifies the teaching mentorship styles of counselor educators with at least one year of experience as teaching mentors (N = 25). Q methodology was used to obtain subjective understandings of how counselor educators mentor. Our results suggest three styles labeled as Supervisor, Facilitator, and Evaluator. Specifically, these styles reflect counselor educators’ distinct viewpoints on how to mentor doctoral students in teaching within counselor education doctoral programs. Implications and limitations for counselor educators seeking to transfer aspects of the identified mentorship styles to their own practice are presented, and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: teaching mentorship, counselor education, Q methodology, doctoral students, graduate teaching

Counselor educators mentor doctoral students in many aspects of the counseling profession, including preparation for future faculty roles (Borders et al., 2011; Briggs & Pehrsson, 2008; S.F. Hall & Hulse, 2010; Lazovsky & Shimoni, 2007; Protivnak & Foss, 2009). Counselor education doctoral students (CEDS) credit faculty mentor relationships in general, and teaching mentorships in particular, as strengthening their professional identities (Limberg et al., 2013). For example, co-teaching, a common form of teaching mentorship, includes relationships that allow CEDS to have instructive pedagogical conversations (Casto, Caldwell, & Salazar, 2005) and learn teaching skills (Baltrinic, Jencius, & McGlothlin, 2016).

Support for teaching mentorships is present in the higher education literature. Doctoral students across disciplines reported the helpfulness of regular mentoring (Austin, 2002) and careful guidance in teaching from faculty members (Jepsen, Varhegyi, & Edwards, 2012). Doctoral students attributed mentoring in teaching as important for increasing self-confidence and comfort with teaching as future faculty members (Utecht & Tullous, 2009). In counselor education, the specific benefits attributed to teaching mentorships included greater confidence in CEDS’ ability to find employment as faculty members (Warnke, Bethany, & Hedstrom, 1999) and greater confidence in CEDS’ teaching ability (S. F. Hall & Hulse, 2010). Doctoral students given teaching opportunities without mentoring risk developing poor attitudes and skill sets, instead of having critical experiences to help them become successful university teachers (Silverman, 2003). Overall, the benefits of teaching mentorships are important given that (a) teaching is a primary component of the faculty job (Davis, Levitt, McGlothlin, & Hill, 2006) and (b) new counselor educators need to sufficiently plan and implement quality teaching (Magnuson, Norem, & Lonneman-Doroff, 2009). Counselor education scholars agree on the importance of mentorship for socializing doctoral students for teaching roles (Baltrinic et al., 2016; Orr, Hall, & Hulse-Killacky, 2008), yet little research is available describing specific styles and approaches to teaching mentorship (S. F. Hall & Hulse, 2010). This gap in the literature is concerning given that new counselor educators reported mentoring and feedback on their teaching by senior faculty members was helpful in enhancing their pedagogical skills (Magnuson, Shaw, Tubin, & Norem, 2004).

Type and Style of Teaching Mentorship

In contrast to discrete faculty–student interactions or training episodes (Black, Suarez, & Medina, 2004), mentor relationships may occur over months and years. Kram (1985) has characterized these relationships as career (teaching skills) and psychosocial (mentor–mentee relationship) types. Career mentoring refers to the act of fostering skills development and sharing field-related content to mentees, and psychosocial mentoring pertains more to the interpersonal and relational aspects of entering a field (e.g., emotional support and working through self-doubt; Curtin, Malley, & Stewart, 2016). Both career and psychosocial mentoring types, or some combination, are used by academic faculty mentors (Curtin et al., 2016). But it is uncertain if these, or any other specific mentoring types, are used for teaching mentorships in counselor education. Teaching mentorships of all types allow faculty members to be flexible, emphasize multiple aspects of being a teacher, and allow for the inclusion of multiple mentors (Borders et al., 2011).

Teaching mentorships transpire through a variety of formal (more structured and planned) and informal (less structured and spontaneous) mentorship styles (Borders et al., 2012). For example, a CEDS may experience teaching mentorship as part of a structured pedagogy course (formal), or have an informal conversation with their faculty advisor about teaching experiences spontaneously during an advising session. Given the complexities and importance of mentor relationships in counselor training, little is known about either formal or informal styles. Thus, it is hardly surprising uncertainty exists regarding counselor educators’ preferred ways of mentoring in general (Borders et al., 2012) and mentoring in teaching in particular (S. F. Hall & Hulse, 2010).

We found no evidence in the counselor education literature describing common styles of teaching mentorship used by counselor educators. This is concerning given that faculty members tend to mentor in the manner that they were mentored (L. A. Hall & Burns, 2009), and that CEDS’ mentorship experiences are influential in shaping their careers as future counselor educators (Borders et al., 2011). Our purpose was to learn more about how counselor educators understand and use their own teaching mentorship styles, thus requiring that we measure aspects of sample members’ subjective understanding of this phenomenon. Therefore, we set out to answer the following research question: What are counselor educators’ preferred styles of engaging in teaching mentorships with CEDS?

Method

Because Q methodology objectively analyzes subjective phenomena, such as people’s preferences and opinions on a topic (Stephenson, 1935), it was selected for this study to reveal the structure of counselor educators’ perspectives (i.e., factors) on the teaching mentorship styles used for preparing CEDS to teach. Q methodology embodies the relative strengths of quantitative and qualitative methodologies by drawing on the depth and richness of qualitative data and the objective rigor of factor analysis to analyze data (Shemmings, 2006).

Participants

The participants (N = 25) eligible for this study: (a) were currently employed as a full-time faculty member in a counselor education doctoral program and (b) had accrued at least one year of experience mentoring CEDS in graduate teaching as a counselor educator. Twenty-five is a sufficient number given that Q methodology simply seeks to establish, understand, and compare individuals’ self-referent views expressed through the Q sort process (Brown, 1980). Participants were both conveniently sampled (n = 10) from counselor educators attending a workshop on Q methodology and purposefully sampled (n = 15) through recruitment emails sent to faculty members at several prominent counselor education doctoral programs in the Eastern (n = 7), Midwestern (n = 10), and Southern (n = 8) regions of the United States. Data were collected from participants by mailing packets that contained an informed consent, basic demographic questionnaire, Q sort, post–Q sort questionnaire, and a postage-prepaid return envelope. (Additional participant demographics are shown in Table 1). Note, we abstained from collecting certain demographic data (e.g., race, ethnicity, university type) from participants in response to their stated concerns about anonymity during data collection. Also, participants in this study were those that completed Q sorts (N = 25) versus those (N = 54) counselor educators used to generate the concourse described below.

Table 1

Demographics of Participants (N = 25)

Age n (%) Rank n (%)

25–30 1 (4%) Full Professor 5 (20%)

31–40 7 (28%) Associate Professor 8 (32%)

41–50 5 (20%) Assistant Professor 12 (48%)

51–60 9 (36%)

61–65+ 3 (12%)

Gender n (%) Tenure Status n (%)

Female 13 (52%) Tenured 13 (52%)

Male 12 (48%) Untenured 12 (48%)

Years of Teaching

Mentorship Experience n (%)

1–5 9 (36%)

6–10 3 (12%)

11–15 6 (24%)

16–20 4 (16%)

Concourse Generation and Selecting Items for the Q Sample

Q methodology studies begin with creating a concourse, or a collection of thoughts or sentiments about a topic (Stephenson, 1978), which serves as the source material for selecting items for the Q sample. To generate the concourse for this study, 54 counselor educators, each with a minimum of one year of experience mentoring doctoral students in graduate teaching, were solicited on a counseling listserv (see Table 2). Counselor educators each provided 5–10 opinion statements on teacher mentorship approaches for working with CEDS in response to one open-ended question: What are your preferred approaches to mentoring CEDS in teaching? This process resulted in 432 opinion statements. However, this was too many statements for participants to rank order during the Q sort process. Accordingly, a 2 x 2 factorial design based on Kram’s (1985) career and psychosocial mentorship types and Borders et al.’s (2012) formal and informal mentoring styles was used as a theoretical guide to obtain a reduced yet representative subset (sample) of statements from the concourse (for additional information on Q sample construction, see Paige & Morin, 2016).

Table 2

Demographics of Counselor Educators Providing Opinion Statements for Concourse (N = 54)

Age n (%) Racial Identity n (%)

25–30 0 (0%) African American 4 (7%)

31–35 8 (15%) Native American/Indigenous 1 (2%)

36–40 13 (24%) Caucasian 38 (70%)

41–45 7 (13%) Hispanic/Latino(a)/Chicano(a) 5 (9%)

46–50 4 (7%) Multiracial 3 (6%)

51–55 7 (13%) Biracial 3 (6%)

56–60 7 (13%)

61–65 4 (7%)

66–70 3 (6%)

71–75+ 1 (2%)

Gender n (%) Primary Professional Identity n (%)

Female 33 (61%) Counselor Educator 51 (94%)

Male 19 (35%) School Counselor Educator 3 (6%)

Transgender 1 (2%)

Gender Fluid 1 (2%)

Sexual Identity n (%) Academic Rank n (%)

Lesbian 3 (6%) Professor 9 (17%)

Gay 4 (7%) Associate Professor 18 (33%)

Bisexual 4 (7%) Assistant Professor 27 (50%)

Heterosexual 43 (80%)

First, the lead author organized the 432 statements into two broad categories: informal and formal mentoring styles (Borders et al., 2012). Duplicate, fragmented, and unclear statements were identified and eliminated in this step. Then, the remaining 96 statements (i.e., 48 statements in the informal and formal categories, respectively) were each cross-referenced with two mentoring types (i.e., psychosocial and career; Kram, 1985). Similar to the first step, the lead author reviewed the content of each statement and eliminated any statements containing duplicate, fragmented, or unclear language, resulting in 52 statements across four domains: 13 statements representing informal and career, 13 statements representing informal and psychosocial, 13 statements representing formal and career, and 13 statements representing formal and psychosocial. Finally, the first author eliminated four and reworded two of the 52 statements after they were reviewed by the second, third, and fourth authors, resulting in a final sample of 48 statements (12 statements per domain). This final group of statements is called the Q sample, which in this case is a collection of statements that represent counselor educators’ perspectives on how to mentor CEDS in teaching. The 48-item Q sample constructed by the first author was reviewed by the second, third, and fourth authors to ensure that each item was unique and did not overlap with other statements, and was applicable to the study. The final Q sample was given to participants for rank ordering during the Q sort process.

Q Sort Process

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, 25 participants completed the Q sort process. During the Q sort process, participants were prompted to reflect on their personal experiences of mentoring teaching to CEDS and then asked to rank order the 48 items in the Q sample on a forced-choice frequency distribution, shown in Table 3. Participants indicated a conscribed number of items with which they most agreed (+4) to items with which they least agreed (-4) along the distribution. Items placed in the middle of the rank order indicated statements about which participants were neutral or ambivalent. After finishing the rank ordering of items, participants were asked to provide brief post–Q sort written responses for the top two or three statements with which they most and least agreed, which were incorporated into the factor interpretations found in the results section below.

Table 3

Q Sort Forced-Choice Frequency Distribution

Ranking Value – 4 -3 -2 -1 0 +1 +2 +3 +4

Number of Items 3 4 6 7 8 7 6 4 3

Data Analysis

Twenty-five completed Q sorts were entered into the PQMethod software program V. 2.35 (Schmolck & Atkinson, 2012). The PQMethod software creates a by-person correlation matrix (i.e., the “intercorrelation of each Q sort with every other Q sort”) used to facilitate factor analysis and subsequent factor rotation (Watts & Stenner, 2012, p. 97). The purpose of factor analysis in Q methodology is to group small numbers of participants with similar views into factors in the form of Q sorts (Brown, 1980). Factor analysis helps researchers rigorously reveal subjective patterns that could be overlooked via qualitative analysis. A 3-factor solution was selected to provide the highest number of significant factor loadings associated with each factor (Watts & Stenner, 2012). Factors were then rotated using varimax criteria with hand rotation adjustments in order to best reveal groupings of individuals with similar Q sorts. The factor rotations increased the total number of significant factor loadings from 17 to 20 of 25 participants, shown in Table 4.

We approached analyzing and interpreting each factor in the context of all other factors to provide a holistic factor interpretation, versus favoring specific items (i.e., factor scores, +4 or -4) over others within a particular factor (Watts & Stenner, 2012). To do so, a worksheet was created from the factor array (see Table 5) for each individual factor containing the highest and lowest ranked items within the factor and those items ranked lower within the factor compared to other factors. Second, items in the worksheets were compared to participants’ demographic and qualitative responses associated with that factor in order to add depth and detail before the final step. Finally, the finished worksheets were used for constructing the factor interpretation narratives, which are written as a story containing the viewpoint of the factor as a whole.

Table 4

Rotated Factor Loadings for Supervisor (1), Facilitator (2), and Evaluator (3)

Q Sort Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

Supervisor Facilitator Evaluator

1 .05 .74 .07

2 .47 .46 .30

3 .13 .60 .24

4 .02 -.13 .76

5 .51 .26 -.23

6 .60 .25 -.16

7 .18 .48 .03

8 .55 .37 .24

9 .54 .17 .13

10 .70 .16 .14

11 .53 .17 .34

12 .54 -.11 .25

13 .22 .48 .16

14 .52 .40 -.04

15 .34 .15 .53

16 .41 .13 .19

17 .10 .39 .33

18 .19 .32 .47

19 .26 .73 .05

20 .27 .04 .12

21 .36 .26 .11

22 .13 .40 .54

23 .10 .55 .03

24 .20 .39 .50

25 .32 .46 .08

Note. Significant loading > .43 are in boldface

Results

The data analysis revealed the existence of three different viewpoints (i.e., factors 1, 2, 3) on mentoring CEDS in graduate teaching. We named the factors Supervisor (F1), Facilitator (F2), and Evaluator (F3), respectively, and included those names in the factor interpretations below to best represent the distinguishing teaching mentorship characteristics of the groups of individuals associated with each factor. The resulting three factors accounted for 37% of the total variance in the correlation matrix. Note that sole reliance on statistical criteria, such as the proportion of variance, is discouraged in Q methodology. This is because a factor may hold theoretical interest and have contextual relevance that may be overlooked if only a statistical basis for interpreting subjective factors is used (Brown, 1980). Twenty of the 25 participants loaded significantly on one of the three factors. Factor loadings of > .43 were significant at the p < 0.01 level. Factor 1 had eight participants with significant loadings, accounting for 14% of the variance. Factor 2 had seven participants with significant loadings, accounting for 15% of the variance, whereas Factor 3 had five participants with significant loadings, accounting for 9% of the variance. Five of the 25 Q sorts were non-significant; four participants’ Q sorts were non-significant (X < .43) and one was confounded, meaning the factor scores for that participant were associated with more than one factor.

Table 5

48-Item Q Sample Factor Array With Factor Scores

| Item |

STATEMENT |

FACTOR SCORES

1 2 3 |

| 1 |

Viewing doctoral students’ life experiences as complementary to those of the faculty teaching mentor. |

-3 |

0 |

-1 |

| 2 |

Exposing doctoral students to progressively more challenging teaching roles with faculty supervision. |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| 3 |

Guiding doctoral students to complete a teaching practicum and/or internship as part of their doctoral training. |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| 4 |

Sharing teaching resources with doctoral students (e.g., group activities, discussion prompts, assignments, etc.). |

-1 |

1 |

0 |

| 5 |

Maintaining a reputation among doctoral students as a quality teacher by modeling and demonstrating quality teaching. |

0 |

2 |

-1 |

| 6 |

Giving doctoral students examples from your own teaching on how to overcome teaching challenges. |

4 |

-3 |

-2 |

| 7 |

Having doctoral students rehearse teaching strategies (e.g., lectures, activities) prior to implementing them in the classroom. |

-2 |

-3 |

-3 |

| 8 |

Defining for doctoral students their teaching roles in and out of the classroom. |

-1 |

-2 |

0 |

| 9 |

Modeling best practices in teaching to facilitate the development of doctoral students’ teaching styles. |

-1 |

1 |

-2 |

| 10 |

Having doctoral students facilitate portions of a course under supervision as part of co-teaching, a course assignment, and so forth. |

3 |

3 |

1 |

| 11 |

Having doctoral students develop and discuss a teaching philosophy. |

0 |

-2 |

2 |

| 12 |

Teaching doctoral students to develop rubrics and grade student assignments. |

-2 |

-1 |

0 |

| 13 |

Providing doctoral students with a safe space to acknowledge their teaching mistakes. |

4 |

4 |

1 |

| 14 |

Assisting doctoral students with incorporating technology and course management systems (e.g., Blackboard) into the teaching process. |

-2 |

-2 |

-4 |

| 15 |

Holding doctoral students to high level of accountability regarding their teaching and learning practices. |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| 16 |

Having doctoral students teach a portion of a class under faculty supervision. |

2 |

3 |

1 |

| 17 |

Immersing doctoral students in teaching environments in a sink-or-swim manner with no advice, preparation, or supervision. |

-4 |

-4 |

-1 |

| 18 |

Having doctoral students co-teach an entire course with faculty members and/or experienced peers. |

4 |

0 |

2 |

| 19 |

Providing strengths-based feedback and support regarding teaching. |

0 |

4 |

0 |

| 20 |

Interacting with doctoral students as colleagues or equals. |

-3 |

3 |

-4 |

| 21 |

Teaching doctoral students to evaluate their teaching effectiveness and student learning. |

1 |

1 |

4 |

| 22 |

Providing doctoral students with specific examples of how to address student issues. |

3 |

-1 |

0 |

| 23 |

Acting as a “sounding board” when doctoral students need to discuss their feelings about teaching. |

0 |

3 |

-3 |

| 24 |

Promoting the creation of critical learning environments where doctoral students are asked to apply higher order cognitive skills (e.g., Bloom’s Taxonomy). |

-3 |

-2 |

4 |

| 25 |

Assisting doctoral students with identifying challenging student behaviors. |

1 |

1 |

2 |

| 26 |

Encouraging doctoral students with teaching experience to engage in mentoring of their peers’ teaching. |

-4 |

-1 |

-3 |

| 27 |

Assisting doctoral students with preparing lectures, activities, and discussion topics. |

-2 |

-1 |

-2 |

| 28 |

Focusing on a broad range of learning and instructional theories when grounding one’s teaching approach. |

-2 |

-3 |

2 |

| 29 |

Having doctoral students participate in a formal course on pedagogy. |

-1 |

-4 |

2 |

| 30 |

Encouraging doctoral students to implement refined teaching approaches after receiving feedback from teaching mentors. |

3 |

-1 |

1 |

| 31 |

Disclosing to doctoral students the ways that faculty members developed their teaching practice, including successes and mistakes. |

2 |

1 |

-2 |

| 32 |

Supporting doctoral students’ solo teaching opportunities (e.g., to lead a class). |

1 |

2 |

0 |

| 33 |

Providing both candid and immediate feedback to doctoral students about their teaching

performance. |

2 |

0 |

0 |

| 34 |

Having doctoral students identify the verbal and nonverbal behaviors that contribute to

building teacher–student rapport. |

-1 |

-1 |

-1 |

| 35 |

Nurturing professionalism in teaching during faculty–doctoral student interactions. |

-3 |

4 |

3 |

| 36 |

Talking to doctoral students about how their life experiences influence their approach to

teaching. |

-4 |

0 |

-1 |

| 37 |

Providing doctoral students with readings on pedagogy. |

1 |

-4 |

2 |

| 38 |

Having doctoral students participate in designing a course. |

2 |

0 |

-2 |

| 39 |

Having doctoral students observe faculty and experienced peers’ teaching. |

-1 |

-2 |

-1 |

| 40 |

Inviting doctoral students to discuss their clinical/school counseling experiences while in a teaching role in the classroom. |

1 |

2 |

-3 |

| 41 |

Assisting doctoral students with developing a syllabus. |

2 |

-1 |

-4 |

| 42 |

Planning before class with doctoral students before they engage in teaching activities. |

1 |

-3 |

-2 |

| 43 |

Discussing boundaries and other ethical concerns regarding teaching. |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| 44 |

Facilitating opportunities to improve doctoral students’ confidence and comfort about teaching. |

-1 |

2 |

-1 |

| 45 |

Helping doctoral students with understanding the variables and actions linked to an improved learning environment. |

-2 |

0 |

1 |

| 46 |

Assisting doctoral students with linking specific learning theories to course content/topic areas. |

0 |

-3 |

1 |

| 47 |

Teaching doctoral students to remain empathic to students’ worldviews by using worldview-affirming language. |

3 |

2 |

3 |

| 48 |

Discussing with doctoral students why instructional decisions were made in the classroom. |

1 |

2 |

0 |

The three factors contain factor exemplars merged to form a single ideal Q sort for each factor, called a factor array (Watts & Stenner, 2012). The factor array, which contains the 48 Q sample items and the associated factor scores for Factors 1 through 3, is found in Table 5. The factor array contains factor scores calculated by weighted averages in which higher-loading Q sorts are given more weight in the averaging process because they better exemplify the factor. It is the factor scores contained in the factor array versus participants’ factor loadings that are used for factor interpretation. Note that parenthetical references to Q sample items and commensurate factor scores (e.g., item 24, +4) provide contextual reference for each of the factor interpretations below.

Factor 1: Supervisor

Eight (32%) of the 25 participants were associated with factor 1. Factor 1 mentors (i.e., Supervisors) view mentoring in teaching as a process that begins with CEDS co-teaching an entire course under the supervision of a faculty member or experienced peer (item 18, +4). Providing CEDS with real-world teaching examples from faculty members’ teaching experiences (item 6, +4) and a safe space to acknowledge teaching mistakes (item 13, +4) are defined as key mentoring processes for Factor 1. In so doing, Supervisors provide candid and immediate feedback about CEDS’ teaching performance (item 33, +2) and incorporate examples from their mentors’ own teaching successes and mistakes as part of the feedback (item 31, +2). These points are illustrated by one participant in her post–Q sort responses: “As a doctoral student, I appreciated receiving honest real-talk feedback (about teaching), which rarely happened. Now, when I mentor students, I tell folks what I really think in a kind but frank manner.” Supervisors encourage CEDS to implement refined teaching approaches after receiving candid feedback about their teaching. Additionally, Supervisors regularly plan before class with CEDS before they engage in teaching activities (item 42, +1). CEDS engage in syllabus development (item 41, +2) and course design (item 38, +2), versus sharing teaching resources (item 4, -1) and linking teaching variables to improved learning environments (item 45, -2), both of which are, as one participant remarked, “assumed to be part of the mentoring process.” Supervisors prefer that CEDS complete formal practica or internships as part of their doctoral training (item 3, +2).

Supervisors employ both formal (e.g., co-teaching, practica and internships, and regular pre-class planning) and informal (e.g., real-world examples, candid feedback, and appropriate professional disclosure about teaching) mentoring practices intended for students’ incremental professional development as teachers (Baltrinic et al., 2016). Supervisors’ teaching mentorship style is guided by the belief that experienced faculty members versus less-experienced peers are critical for influencing the development of doctoral students’ teaching skills (item 26, -4), more so than Factors 2 and 3. And, although Supervisors agree that no doctoral student should learn to teach in a sink-or-swim manner (item 17, -4), the Supervisor takes a less nurturing, or life experience–based approach to mentoring (items 1, -3; 35, -3; and 36, -4 respectively) than Factors 2 and 3. A less nurturing approach may be difficult to understand given the nature of mentoring itself. Keep in mind that what is central to Supervisors’ views on mentoring is the instructive and real-world supervision of students’ structured teaching activities over time, which does not preclude faculty members valuing students’ life experience or nurturing their development; rather, these are not central drivers for preferred mentoring interactions between faculty members and students.

Factor 2: Facilitator

Seven (28%) of the 25 participants agreed with Factor 2, which we have titled Facilitator. Facilitators are distinguished as mentors who nurture professionalism during faculty–student interactions (item 35, +4) and provide feedback and support using a strengths-based approach regarding CEDS’ teaching (item 19, +4). Similar to Supervisors (Factor 1), Facilitators provide CEDS with a safe space in the mentoring relationship to acknowledge teaching mistakes (item 13, +4). However, Facilitators favor providing supportive versus corrective or formal feedback (item 30, -1) as central to the mentoring relationship—described aptly by one participant as “I am not big on structured pedagogical teaching. In other words, modeling and supportive discussion can serve the mentor well.” It stands to reason that Facilitators prefer to maintain a reputation as a quality teacher by modeling and demonstrating best practices in teaching (item 5, +2), and thereby extend this practice to facilitate the development of CEDS’ teaching styles (item 9, +1). Accordingly, Facilitators do not approach mentoring in teaching by providing CEDS with formal readings on pedagogy, or have them participate in a formal course on pedagogy (items 29, -4 and 37, -4 respectively). Instead, Facilitators prefer to discuss with CEDS why they made teaching decisions in the classroom without being prescriptive (item 48, +2).

Facilitators approach mentoring by treating CEDS as colleagues or equals during the teaching experience (item 20, +3) and by creating opportunities for them to improve their comfort and confidence when teaching (item 44, +2). When providing feedback, Facilitators act as sounding boards for CEDS to express their feelings about teaching (item 23, +3). For example, noted in one participant’s post–Q sort response, “We learn the most through our own discomfort, so a mentor serving as a sounding board is very important.” Facilitators are more interested than Supervisors or Evaluators (Factor 3) in how CEDS’ life experiences influence their approach to teaching (item 36, 0). In the classroom, Facilitators invite CEDS to discuss their clinical or school counseling experiences when teaching (item 40, +2). In contrast with the Supervisor and the Evaluator, the Facilitator will share examples of their own teaching resources with CEDS (item 4, +1). In general, Facilitators prefer to have CEDS formally teach a portion of a class under their supervision (item 16, +3), versus having them co-teach an entire class or be thrown into teaching in a sink-or-swim manner (item 17, -4).

Facilitators avoid helping CEDS overcome teaching challenges through examples from their own teaching (item 6, -3) or by providing specific examples to address issues. Overall, Facilitators prefer not to define teaching roles for CEDS (item 8, -2), pre-plan specific activities before class (item 42, -3), provide particular learning theories to address specific course content (item 46, -3), or impose on the learning environment (item 28, -3). Finally, Facilitators do not prefer to provide CEDS with feedback that they should use to refine and subsequently implement during future teaching endeavors (item 30, -1), which is not surprising given the relational and discovery-oriented focus of this factor’s approach to mentoring in teaching.

Factor 3: The Evaluator

Factor 3, the Evaluator, included five (20%) of the 25 participants. Evaluators create a critical learning environment for CEDS to use higher order cognitive skills (item 24, +4) while helping them to evaluate their teaching effectiveness and student learning (item 21, +4). Additionally, Evaluators create a safe space for CEDS to acknowledge their mistakes (item 13, +1) and offer corrective feedback as a way for them to refine their teaching (item 30, +1). Unlike Facilitators in Factor 2, Evaluators do not interact with CEDS as colleagues or equals (item 20, -4), initiate conversations about students’ feelings (item 23, -3), or promote students’ confidence and comfort (item 44, -1) about teaching as a central part of mentorship. Instead, Evaluators come from a directive teaching perspective and place an emphasis on content-driven mentorship. Fittingly, Evaluators have high expectations of CEDS to learn and study critical components of teaching and guide students accordingly. Evaluators provide CEDS with readings on pedagogy (item 37, +2) and expose students to a range of learning and instructional theories (item 28, +2). Evaluators also place high value on CEDS taking a formal class on pedagogy (item 29, +2), distinguishing themselves from Supervisors and Facilitators, who rated teaching-related course work as less important.

Although Evaluators make students aware of ethical concerns while teaching (item 42, -2) and identify specific techniques linked to improved learning (item 45, +1), other pragmatic aspects of teaching are given less attention. For example, Evaluators place minimal importance on rubric development and grading practices (item 12, 0) and course design (item 38, -2), and even less importance on developing a syllabus (item 41, -4) and incorporating technology or course management systems into the teaching process (item 14, -4). This is a stark difference from Supervisors in Factor 1, who placed higher value on some of these responsibilities. And Supervisors emphasize skill development, whereas Evaluators stress creating a strong theoretical foundation to guide CEDS’ teaching tasks.

Classroom experiences, though secondary to learning theory and techniques, also are important aspects to mentorship for participants grouped in Factor 3. Evaluators supervise CEDS as they teach portions of courses (item 10, +1) or take on solo teaching opportunities (item 32, 0). In these circumstances, Evaluators hold CEDS to high levels of accountability in terms of their teaching and learning practices (item 15, +4), as opposed to their counterparts in Factors 1 and 2, who rate the importance of accountability more neutrally. One participant illustrates the importance of accountability: “I want doctoral students to know the how, what, and why of where they are going in the classroom, otherwise their students may end up somewhere else. Educators need to be responsible for accounting for students’ outcomes.” Offering feedback to improve teaching is a key aspect of the mentoring process for Evaluators as mentors and students evaluate these hands-on teaching experiences (item 30, +1). These experiences may be critical for Evaluators to assess CEDS’ learning and abilities, gradually exposing them to more challenging teaching roles (item 2, +3).

Throughout the mentorship process, Evaluators place CEDS’ learning and teaching practice at the center of interactions. Whereas Supervisors and Facilitators share their teaching experiences with CEDS, Evaluators avoid conversation about successes or mistakes in their teacher development (item 21, +4). Furthermore, Evaluators do not believe their reputations as quality teachers (item 5, -1) nor their modeling of best practices in teaching is relevant to CEDS’ development of teaching styles (item 9, -2). Instead, Evaluators keep themselves in a distant position during the course of mentorship. Key teaching mentorship interactions are characterized as student-centered and include discussion of their unique teaching philosophies (item 11, +2), exploration of the intentionality behind the instructional decisions they make in classrooms (item 48, 0), and evaluation of their teaching effectiveness (item 21, +4). Consequently, the mentorship style of Evaluators is directive but student-focused, with emphasis on mentees learning and reflecting upon various pedagogical theories and practices as they develop into teachers.

Discussion

Three different perspectives (i.e., Supervisor, Facilitator, and Evaluator) exist among counselor educators of preferred ways to mentor CEDS in teaching. The three perspectives could be conceptualized as different styles of mentorship that are used by counselor educators. Although each perspective is unique, we noticed areas of agreement among counselor educators on using certain formal (e.g., co-teaching), informal (e.g. affirming worldviews), and combinations of mentoring approaches (Borders et al., 2011). These areas of agreement are similar to mentorship experiences in research with CEDS (Borders et al., 2012). The findings of this study also reinforce that mentoring is a complex process in which mentors fill a variety of roles and initiate multiple activities (Casto et al., 2005). Overall, results lend support for teaching mentorship also supported by the literature. For example, Silverman’s (2003) suggestions that learning about pedagogy, having teaching experiences, and working closely with an experienced mentor who facilitates pedagogical conversations are helpful for preparing future faculty members. Though the pairing procedures between participants and students were unknown (e.g., intentionally paired, general guidance; Borders et al., 2011), each factor in this study contained some combination of formal (e.g., planned readings or activities) and informal (e.g., in-the-moment conversations, minimal planning) approaches to mentoring, which is consistent with other findings on preparing CEDS to teach (Baltrinic et al., 2016).

Both career and psychosocial mentoring types are embodied within the three factors reported in the current study, the findings of which support and extend the work of Kram (1985) by providing examples specific to teaching mentorship styles. The Evaluator and the Supervisor perspectives contain career components, as they are knowledge and skill driven, respectively. The Facilitator perspective is reflective of Kram’s psychosocial type, as it is the most relational, exploratory, and insight-oriented perspective of the three. Though career and psychosocial properties overlap between factors (e.g., skill building, feedback, support), each mentoring perspective has one that is a central characteristic.

The combination of career and psychosocial (Kram, 1985) mentoring types evident in the results also are highlighted in other counselor education mentorship guidelines. Similar to the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision research mentorship model (Borders et al., 2012), participants noted the importance of mentors demonstrating and transferring teaching-oriented knowledge and skills to mentees, as well as providing constructive feedback. Other mentor characteristics and tactics, such as facilitating student self-assessment and accountability, modeling, and creating a supportive and open relationship (Black et al., 2004; Briggs & Pehrsson, 2008), are reflected in the current findings on teacher mentoring approaches. For some participants, maintaining a nurturing and supportive environment was of utmost importance, which also has been noted as essential for mentoring CEDS (Casto et al., 2005).

Borders et al. (2011) specifically noted the importance of mentoring graduate students who aspire to be faculty and, though minimally, addressed pedagogy support by offering teaching opportunities to students and engaging them in conversation about their experiences. The current research findings expand on Borders and colleagues’ position by providing ideas on what these conversations might entail. All three factors identified teacher-related topics of conversation and relevant activities, including teaching philosophies, skills, and tasks; pedagogical and learning theories; monitoring student interactions; classroom ethics and boundaries; and self-efficacy associated with teacher development. This offers some unique ideas on topics of interest that may be incorporated into conversations when mentoring students in teaching.

A practical component to teaching mentorships is represented within the factors. Rather than culminating in a product, such as co-written publications developed in research mentoring (Briggs & Pehrsson, 2008), each of the three teaching mentorship factors guide CEDS through applied teaching experiences. These hands-on teaching opportunities provided experiences for CEDS to work through and reflect upon, and offered material for mentors to provide feedback. The extent of student involvement in teaching varied, as did the direction of conversations (e.g., corrective, exploratory); nevertheless, some mentoring tasks were built from observable and enacted teaching moments.

Implications for Counselor Education Programs and Counselor Educators

We believe that it may be helpful for faculty members in positions of leadership (i.e., department chairs, doctoral program coordinators) in counselor education doctoral programs to infuse awareness of teaching mentorship practices among other faculty members. Senior counselor education faculty members responsible for coordinating doctoral programs may be able to create more impactful mentorship experiences for CEDS by encouraging other faculty members to become more aware of their mentorship practices. Several researchers have suggested that quality mentorship is associated with counselor education faculty members who demonstrate intentionality in their mentorship practices (Black et al., 2004; Casto et al., 2005). Findings from this study can generate discussion and self-assessment among faculty members, leading to a clearer understanding of different mentoring styles that exist within a department or program. As different mentoring styles are identified among faculty members, it may help to consider ways to match CEDS with faculty members who will be a good fit for their preferred learning style.

Similarly, we also believe that counselor educators mentoring CEDS in teaching can benefit from being reflective about their own style of mentorship. It may be helpful to consider one’s personal style of mentorship in relation to the styles of teaching mentorship (i.e., Supervisor, Facilitator, and Evaluator) highlighted in this study. Counselor educators who identify with a particular teaching mentorship style may discuss this with CEDS early in the mentorship process to facilitate a goodness of fit. In situations in which CEDS do not have the opportunity to select a mentor of their choosing, it may be particularly important for counselor educators to consider how their style of mentorship will fit with their mentee. It may help counselor educators identifying with a singular style of mentorship to integrate strengths from other styles of mentorship into their practice. For example, a counselor educator who closely identifies with the Supervisor style may benefit from increasing the amount of strength-based feedback they provide mentees (i.e., associated with the Facilitator), or by being more methodical about gradually increasingly their mentees exposure to challenging teaching experiences (i.e., associated with the Evaluator).

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Q studies are not generalizable in the same way as other quantitative studies. The data in this study represent subjective perspectives; thus, results are viewed similar to qualitative studies (Watts & Stenner, 2012). However, Q results offer an additional rigor derived from the factor analysis of the participants’ respective Q sorts. Results from this study pertain to mentoring CEDS in aspects of pedagogy and not clinical teaching or clinical experiences. Future Q methodology studies can use purposeful samples of diverse particpants with a range of pedagogy and clinical teaching experiences, and use participants from a wider range of regions within the United States. Examining students’ and faculty members’ critical incidents during teaching mentorships may increase understanding of respective mentor and mentee perspectives. Future studies distinguishing teacher mentorship from research mentorship would be useful. Finally, investigating the specific practices of the three factor types through single-case studies could provide in-depth perspectives on faculty members’ teaching mentorship styles.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest or funding contributions for the development of this manuscript.

References

Austin, A. E. (2002). Preparing the next generation of faculty: Graduate school as socialization to the academic career. The Journal of Higher Education, 73, 94–122.

Baltrinic, E. R., Jencius, M., & McGlothlin, J. (2016). Co-teaching in counselor education: Preparing doctoral students for future teaching. Counselor Education and Supervision, 55, 31–45.

Black, L. L., Suarez, E. C., & Medina, S. (2004). Helping students help themselves: Strategies for successful mentoring relationships. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 44–55.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2004.tb01859.x

Borders, D. L., Wester, K. L., Haag Granello, D., Chang, C. Y., Hays, D. G., Pepperell, J., & Spurgeon, S. L.

(2012). Association for Counselor Education and Supervision guidelines for research mentorship: Development and implementation. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51, 162–175.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00012.x

Borders, D. L., Young, J. S., Wester, K. L., Murray, C. E., Villalba, J. A., Lewis, T. F., & Mobley, A. K. (2011). Mentoring promotion/tenure-seeking faculty: Principles of good practice within a counselor education program. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 171–188. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2011.tb00118.x

Briggs, C. A., & Pehrsson, D.-E. (2008). Research mentorship in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48, 101–113. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2008.tb00066.x

Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity: Applications of Q methodology in political science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Casto, C., Caldwell, C., & Salazar, C. F. (2005). Creating mentoring relationships between female faculty and students in counselor education: Guidelines for potential mentees and mentors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 331–336. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00351.x

Curtin, N., Malley, J., & Stewart, A. J. (2016). Mentoring the next generation of faculty: Supporting academic career aspirations among doctoral students. Research in Higher Education, 57, 714–738.

doi:10.1007/s11162-015-9403-x

Davis, T. E., Levitt, D. H., McGlothlin, J. M., & Hill, N. R. (2006). Perceived expectations related to promotion and tenure: A national survey of CACREP program liaisons. Counselor Education and Supervision, 46, 146–156. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00019.x

Hall, L. A., & Burns, L. D. (2009). Identity development and mentoring in doctoral education. Harvard Educational Review, 79, 49–70. doi:10.17763/haer.79.1.wr25486891279345

Hall, S. F., & Hulse, D. (2010). Perceptions of doctoral level teaching preparation in counselor education. The Journal for Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 1, 2–15. doi:10.7729/12.0108

Jepsen, D. M., Varhegyi, M. M., & Edwards, D. (2012). Academics’ attitudes towards PhD students’ teaching: Preparing research higher degree students for an academic career. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34, 629–645.

Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Glenview, IL: Foresman.

Lazovsky, R., & Shimoni, A. (2007). The on-site mentor of counseling interns: Perceptions of ideal role and actual role performance. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 303–316.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00479.x

Limberg, D., Bell, H., Super, J. T., Jacobson, L., Fox, J., DePue, K., . . . Lambie. G. W. (2013). Professional

identity development of counselor education doctoral students: A qualitative investigation. The Professional Counselor, 3, 40–53. doi:10.15241/dll.3.1.40

Magnuson, S., Norem, K., & Lonneman-Doroff, T. (2009). The 2000 cohort of new assistant professors of counselor education: Reflecting at the culmination of six years. Counselor Education and Supervision, 49, 54–71. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00086.x

Magnuson, S., Shaw, H., Tubin, B., & Norem, K. (2004). Assistant professors of counselor education: First and second year experiences. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory, & Research, 32, 3–18.

Orr, J. J., Hall, S. F., & Hulse-Killacky, D. (2008). A model for collaborative teaching teams in counselor education. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47, 146–163. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2008.tb00046.x

Paige, J. B., & Morin, K. H. (2016). Q-sample construction: A critical step for Q-methodological study. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38, 96–110. doi:10.1177/0193945914545177

Protivnak, J. J., & Foss, L. L. (2009). An exploration of themes that influence the counselor education doctoral student experience. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48, 239–256.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00078.x

Schmolck, P., & Atkinson, J. (2012). PQMethod (2.35). Retrieved from http://schmolck.userweb.mwn.de

qmethod/#PQMethod

Shemmings, D. (2006). ‘Quantifying’ qualitative data: An illustrative example of the use of Q methodology in

psychosocial research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 147–165. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp060oa

Silverman, S. (2003). The role of teaching in the preparation of future faculty. Quest, 55, 72–81.

doi:10.1080/00336297.2003.10491790

Stephenson, W. (1935). Technique of factor analysis. Nature, 136, 297. doi:10.1038/136297b0

Stephenson, W. (1978). Concourse theory of communication. Communication, 3, 21–40.

Utecht, R. L., & Tullous, R. (2009). Are we preparing doctoral students in the art of teaching? Research in Higher Education Journal, 4, 1–12.

Warnke, M. A., Bethany, R. L., & Hedstrom, S. M. (1999). Advising doctoral students seeking counselor

education faculty positions. Counselor Education and Supervision, 38, 177–190

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.1999.tb00569.x

Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q methodological research: Theory, method and interpretation. London,

England: Sage.

Eric R. Baltrinic is an assistant professor at Winona State University. Randall M. Moate is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Tyler. Michelle Gimenez Hinkle is an assistant professor at William Paterson University. Marty Jencius is an associate professor at Kent State University. Jessica Z. Taylor is an assistant professor at Central Methodist University. Correspondence can be addressed to Eric Baltrinic, Gildemeister 116A, P.O. Box 5838, 175 West Mark Street, Winona, MN 55987-5838, ebaltrinic@gmail.com.

Apr 5, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 1

Melodie H. Frick, Harriet L. Glosoff

Counselor education doctoral students are influenced by many factors as they train to become supervisors. One of these factors, self-efficacy beliefs, plays an important role in supervisor development. In this phenomenological, qualitative research, 16 counselor education doctoral students participated in focus groups and discussed their experiences and perceptions of self-efficacy as supervisors. Data analyses revealed four themes associated with self-efficacy beliefs: ambivalence in the middle tier of supervision, influential people, receiving performance feedback, and conducting evaluations. Recommendations for counselor education and supervision, as well as future research, are provided.

Keywords: supervision, doctoral students, counselor education, self-efficacy, phenomenological, focus groups

Counselor education programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) require doctoral students to learn supervision theories and practices (CACREP, 2009). Professional literature highlights information on supervision theories (e.g., Bernard & Goodyear, 2009), supervising counselors-in-training (e.g., Woodside, Oberman, Cole, & Carruth, 2007), and effective supervision interventions and styles (e.g., Fernando & Hulse-Killacky, 2005) that assist with supervisor training and development. Until recently, however, few researchers have studied the experiences of counselor education doctoral students as they prepare to become supervisors (Hughes & Kleist, 2005; Limberg et al., 2013; Protivnak & Foss, 2011) or “the transition from supervisee to supervisor” (Rapisarda, Desmond, & Nelson, 2011, p. 121). Specifically, an exploration of factors associated with the self-efficacy beliefs of counselor education doctoral student supervisors is warranted to expand this topic and enhance counselor education training of supervisor development.

Bernard and Goodyear (2009) described supervisor development as a process shaped by changes in self-perceptions and roles, much like counselors-in-training experience in their developmental stages. Researchers have examined factors that may influence supervisors’ development (e.g., experiential learning and the influence of feedback). For example, Nelson, Oliver, and Capps (2006) explored the training experiences of 21 doctoral students in two cohorts of the same counseling program and reported that experiential learning, the use of role-plays, and receiving feedback from both professors and peers were equally as helpful in learning supervision skills as the actual practice of supervising counselors-in-training. Conversely, a supervisor’s development may be negatively influenced by unclear expectations of the supervision process or dual relationships with supervisees, which may lead to role ambiguity (Bernard & Goodyear, 2009). For example, Nilsson and Duan (2007) examined the relationship between role ambiguity and self-efficacy with 69 psychology doctoral student supervisors and found that when participants received clear supervision expectations, they reported higher rates of self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy is one of the self-regulation functions in Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and is a factor in Larson’s (1998) social cognitive model of counselor training (SCMCT). Self-efficacy, the differentiated beliefs held by individuals about their capabilities to perform (Bandura, 2006), plays an important role in counselor and supervisor development (Barnes, 2004; Cashwell & Dooley, 2001) and is influenced by many factors (Schunk, 2004). Along with the counselor’s training environment, self-efficacy beliefs may influence a counselor’s learning process and resulting counseling performance (Larson, 1998). Daniels and Larson (2001) conducted a quantitative study with 45 counseling graduate students and found that performance feedback influenced counselors’ self-efficacy beliefs; self-efficacy increased with positive feedback and decreased with negative feedback. Steward (1998), however, identified missing components in the SCMCT, such as the role and level of self-efficacy of the supervisor, the possible influence of a faculty supervisor, and doctoral students giving and receiving feedback to supervisees and members of their cohort. For example, results of both quantitative studies (e.g., Hollingsworth & Fassinger, 2002) and qualitative studies (e.g., Majcher & Daniluk, 2009; Nelson et al., 2006) indicate the importance of mentoring experiences and relationships with faculty supervisors to the development of doctoral students and self-efficacy in their supervisory skills.

During their supervision training, doctoral students are in a unique position of supervising counselors-in-training while also being supervised by faculty. For the purpose of this study, the term middle tier will be used to describe this position. This term is not often used in the counseling literature, but may be compared to the position of middle managers in the business field—people who are subordinate to upper managers while having the responsibility of managing subordinates (Agnes, 2003). Similar to middle managers, doctoral student supervisors tend to have increased responsibility for supervising future counselors, albeit with limited authority in supervisory decisions, and may have experiences similar to middle managers in other disciplines. For example, performance-related feedback as perceived by middle managers appears to influence their role satisfaction and self-efficacy (Reynolds, 2006). In Reynolds’s (2006) study, 353 participants who represented four levels of management in a company in the United States reported that receiving positive feedback from supervisors had an affirming or encouraging effect on their self-efficacy, and that their self-efficacy was reduced after they received negative supervisory feedback. Translated to the field of counselor supervision, these findings suggest that doctoral students who participate in tiered supervision and receive positive performance feedback may have higher self-efficacy.

Findings to date illuminate factors that influence self-efficacy beliefs, such as performance feedback, clear supervisor expectations and mentoring relations. There is a need, however, to examine what other factors enhance or detract from the self-efficacy beliefs of counselor education doctoral student supervisors to ensure effective supervisor development and training. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to build on previous research and further examine the experiences of doctoral students as they train to become supervisors in a tiered supervision model. The overarching research questions that guided this study included: (a) What are the experiences of counselor education doctoral students who work within a tiered supervision training model as they train to become supervisors? and (b) What experiences influenced their sense of self-efficacy as supervisors?

Method

Design

A phenomenological research approach was selected to explore how counselor education doctoral students experience and make meaning of their reality (Merriam, 2009), and to provide richer descriptions of the experiences of doctoral student supervisors-in-training, which a quantitative study may not afford. A qualitative design using a constructivist-interpretivist method provided the opportunity to interact with doctoral students via focus groups and follow-up questionnaires to explore their self-constructed realities as counselor supervisors-in-training, and the meaning they placed on their experiences as they supervised master’s-level students while being supervised by faculty supervisors. Focus groups were chosen as part of the design, as they are often used in qualitative research (Kress & Shoffner, 2007; Limberg et al., 2013), and multiple-case sampling increases confidence and robustness in findings (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Participants

Sixteen doctoral students from three CACREP-accredited counselor education programs in the southeastern United States volunteered to participate in this study. These programs were selected due to similarity in supervision training among participants (e.g., all were CACREP-accredited, required students to take at least one supervision course, utilized a full-time cohort design), and were in close proximity to the principal investigator. None of the participants attended the first author’s university or had any relationships with the authors. Criterion sampling was used to select participants that met the criteria of providing supervision to master’s-level counselors-in-training and receiving supervision by faculty supervisors at the time of their participation. The ages of the participants ranged from 27–61 years with a mean age of 36 years (SD = 1.56). Fourteen of the participants were women and two were men; two participants described their race as African-American (12.5%), one participant as Asian-American (6.25%), 12 participants as Caucasian (75%), and one participant as “more than one ethnicity” (6.25%). Seven of the 16 participants reported having 4 months to 12 years of work experience as counselor supervisors (M = 2.5 years, SD = 3.9 years) before beginning their doctoral studies. At the time of this study, all participants had completed a supervision course as part of their doctoral program, were supervising two to six master’s students in the same program (M = 4, SD = 1.2), and received weekly supervision with faculty supervisors in their respective programs.

Researcher Positionality

In presenting results of phenomenological research, it is critical to discuss the authors’ characteristics as researchers, as such characteristics influence data collection and analysis. The authors have experience as counselors, counselor educators, and clinical supervisors. Both authors share an interest in understanding how doctoral students move from the role of student to the role of supervisor, especially when providing supervision to master’s students who may experience critical incidents (with their clients or in their own development). The first author became engaged when she saw the different emotional reactions of her cohort when faced with the gatekeeping process, whether the reactions were based on personality, prior supervision experience, or stressors from inside and outside of the counselor education program. She wondered how doctoral students in other programs experienced the aforementioned situations, what kind of structure other programs used to work with critical incidents that involve remediation plans, and if there were ways to improve supervision training. It was critical to account for personal and professional biases throughout the research process to minimize biases in the collection or interpretation of data. Bracketing, therefore, was an important step during analysis (Moustakas, 1994) to reduce researcher biases. The first author accomplished this by meeting with her dissertation committee and with the second author throughout the study, as well as using peer reviewers to assess researcher bias in the design of the study, research questions, and theme development.

Quality and Trustworthiness

To strengthen the rigor of this study, the authors addressed credibility, dependability, transferability and confirmability (Merriam, 2009). One way to reinforce credibility is to have prolonged and persistent contact with participants (Hunt, 2011). The first author contacted participants before each focus group to convey the nature, scope and reasons for the study. She facilitated 90-minute focus group discussions and allowed participants to add or change the summary provided at the end of each focus group. Further, information was gathered from each participant through a follow-up questionnaire and afforded the opportunity for participants to contact her through e-mail with additional questions or thoughts.

By keeping an ongoing reflexive journal and analytical memos, the first author addressed dependability by keeping a detailed account throughout the research study, indicating how data were collected and analyzed and how decisions were made (Merriam, 2009). The first author included information on how data were reduced and themes and displays were constructed, and the second author conducted an audit trail on items such as transcripts, analytic memos, reflection notes, and process notes connecting findings to existing literature.

Through the use of rich, thick description of the information provided by participants, the authors made efforts to increase transferability. In addition, they offered a clear account of each stage of the process as well as the demographics of the participants (Hunt, 2011) to promote transferability.

Finally, the first author strengthened confirmability by examining her role as a research instrument. Selected colleagues chosen as peer reviewers (Kline, 2008), along with the first author’s dissertation committee members, had access to the audit trail and discussed and questioned the authors’ decisions, further increasing the integrity of the design. Two doctoral students who had provided supervision and had completed courses in qualitative research, but who had no connection to the research study, volunteered to serve as peer reviewers. They reviewed the focus group protocol for researcher bias, read the focus group transcripts (with pseudonyms inserted) and questionnaires, and the emergent themes, to confirm or contest the interpretation of the data. Further, they reviewed the quotes chosen to support themes for richness of description and provided feedback regarding the textural-structural descriptions as they were being developed. Their recommendations, such as not having emotional reactions to participants’ comments, guided the authors in data collection and analysis.

Data Collection

Upon receiving approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board, the first author contacted the directors of three CACREP-accredited counselor education programs and discussed the purpose of the study, participants’ rights, and logistical needs. Program directors disseminated an e-mail about this study to their doctoral students, instructing volunteer participants to contact the first author about participating in the focus groups.

Within a two-week period, she conducted three focus groups—one at each counselor education program site. Each focus group included five to six participants and lasted approximately 90 minutes. She employed a semi-structured interview protocol consisting of 17 questions (see Appendix). The questions were based on an extensive literature review on counselor and supervisor self-efficacy studies (e.g., Bandura, 2006; Cashwell & Dooley, 2001; Corrigan & Schmidt, 1983; Fernando & Hulse-Killacky, 2005; Gore, 2006; Israelashvili & Socher, 2007; Steward, 1998; Tang et al., 2004). The initial questions were open and general at first, so as to not lead or bias the participants in their responses. As the focus groups continued, the first author explored more specific information about participants’ experiences as doctoral student supervisors, focusing questions around their responses (Kline, 2008). Conducting a semi-structured interview with participants ensured that she asked specific questions and addressed predetermined topics related to the focus of the study, while also allowing for freedom to follow up on relevant information provided by participants during the focus groups.

Approximately six to eight weeks after each focus group, participants received a follow-up questionnaire consisting of four questions: (a) What factors (inside and outside of the program) influence your perceptions of your abilities as a supervisor? (b) How do you feel about working in the middle tier of supervision (i.e., working between a faculty supervisor and the counselors-in-training that you supervise)? (c) What, if anything, could help you feel more competent as a supervisor? (d) How can your supervision training be improved? The purpose of the follow-up questions was to explore participants’ responses after they gained more experiences as supervisors and to provide a means for them to respond to questions about their supervisory experiences privately, without concern of peer judgment.

Data Analysis

Data analysis began during the transcription process, with analysis occurring simultaneously with the collection of the data. The first author transcribed, verbatim, the recording of each focus group and changed participant names to protect their anonymity. Data analysis was then conducted in three stages: first, data were analyzed to identify significant issues within each focus group; second, data were cross-analyzed to identify common themes across all three focus groups; and third, follow-up questionnaires were analyzed to corroborate established themes and to identify additional, or different themes.

During data analysis, a Miles and Huberman (1994) approach was employed by using initial codes from focus-group question themes. Inductive analysis occurred with immersion in the data by reading and rereading focus group transcripts. It was during this immersion process that the first author began to identify core ideas and differentiate meanings and emergent themes for each focus group. She accomplished data reduction by identifying themes in participants’ answers to the interview protocol and focus group discussions until saturation was reached, and displayed narrative data in a figure to organize and compare developed themes. Finally, she used deductive verification of findings with previous research literature. During within-group analysis, she identified themes if more than half (i.e., more than three participants) of a focus group reported similar experiences, feelings or beliefs. Likewise, in across-group analyses, she confirmed themes if statements made by more than half (more than eight) of the participants matched. There were three cases in which the peer reviewers and the first author had differences of opinion on theme development. In those cases, she made changes guided by the suggestions of the peer reviewers. In addition, she sent the final list of themes related to the research questions to the second author and other members of the dissertation committee for purposes of confirmability.

Results

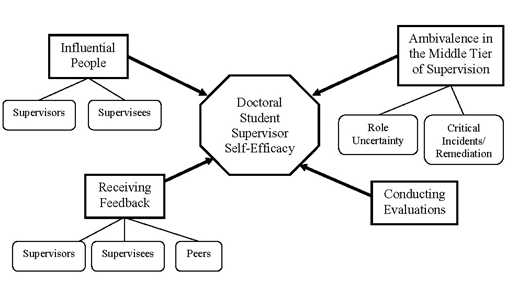

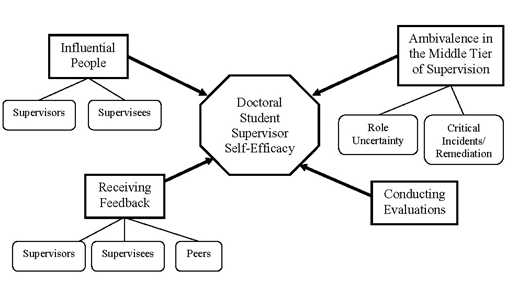

Results of this phenomenological study revealed several themes associated with doctoral students’ perceptions of self-efficacy as supervisors (see Figure 1). Cross-group analyses are provided with participant quotes that are most relevant to each theme being discussed. Considerable overlap of four themes emerged across groups: ambivalence in the middle tier of supervision, influential people, receiving feedback, and conducting evaluations.

Figure 1. Emergent themes of doctoral student supervisors’ self-efficacy beliefs. Factors identified by doctoral student as affecting their self-efficacy as supervisors are represented with directional, bold-case arrows from each theme toward supervisor self-efficacy; below themes are sub-themes in each group connected with non-directional lines.

Ambivalence in the Middle Tier of Supervision

All participants noted how working in the middle tier of supervision brought up issues about their roles and perceptions about their capabilities as supervisors. All 16 participants reported feeling ambivalent about working in the middle tier, especially in relation to their role as supervisors and about dealing with critical incidents with supervisees involving the need for remediation. What follows is a presentation of representative quotations from one or two participants in the emergent sub-themes of role uncertainty and critical incidents/remediation.

Role Uncertainty. Participants raised the issue of role uncertainty in all three focus groups. For example, one participant described how it felt to be in the middle tier by stating the following:

I think that’s exactly how it feels [to be in the middle] sometimes….not really knowing how much you know, what does my voice really mean? How much of a say do we have if we have big concerns? And is what I recognize really a big concern? So I think kind of knowing that we have this piece of responsibility but then not really knowing how much authority or how much say-so we have in things, or even do I have the knowledge and experience to have much say-so?

Further, another participant expressed uncertainty regarding her middle-tier supervisory role as follows:

[I feel a] lack of power, not having real and true authority over what is happening or if something does happen, being able to make those concrete decisions…Where do I really fit in here? What am I really able to do with this supervisee?…kind of a little middle child, you know really not knowing where your identity really and truly is. You’re trying to figure out who you really are.

Participants also indicated difficulty discerning their role when supervising counselors-in-training who were from different specialty areas such as college counseling, mental health counseling, and school counseling. All participants stated that they had not had any specific counseling or supervision training in different tracks, which was bothersome for nine participants who supervised students in specialties other than their own. For example, one participant stated the following:

I’m a mental health counselor and worked in the community and I have two school counselor interns, and so it was one of my very first questions was like, what do I do with these people? ’Cause I’m not aware of the differences and what I should be guiding them on anything.

Another participant noted how having more information on the different counseling tracks (e.g., mental health, school, college) would be helpful:

We’re going to be counselor educators. We may find ourselves having to supervise people in various tracks and I could see how it would be helpful for us to all have a little bit more information on a variety of tracks so that we could know what to offer, or how things are a little bit different.

Working in the middle tier of supervision appeared to be vexing for focus group participants. They expressed feelings of uncertainty, especially in dealing with critical incidents or remediation of supervisees. In addition to defining their roles as supervisors in the middle tier, another sub-theme emerged in which participants identified how they wanted to have a better understanding of how remediation plans work and have the opportunity to collaborate with faculty supervisors in addressing critical incidents with supervisees.

Critical Incidents/Remediation. Part of the focus group discussion centered on what critical incidents participants had with their supervisees and how comfortable they were, or would be, in implementing remediation plans with their supervisees. All participants expressed concerns about their roles as supervisors when remediation plans were required for master’s students in their respective programs and were uncertain of how the remediation process worked in their programs. Thirteen of the 16 participants expressed a desire to be a part of the remediation process of their supervisees in collaboration with faculty supervisors. They discussed seeing this as an important way to learn from the process, assuming that as future supervisors and counselor educators they will need to be the ones to implement such remediation plans. For example, one participant explained the following:

If we are in the position to provide supervision and we’re doing this to enhance our professional development so in the hopes that one day we’re going to be in the position of counselor educators, let’s say faculty supervisors, my concern with that is how are we going to know what to do unless we are involved [in the remediation process] now? And so I feel like that should be something that we’re provided that opportunity to do it.

Another participant indicated that she felt not being part of the remediation process took away the doctoral student supervisors’ credibility:

I don’t have my license yet, and I’m not sure how that plays into when there is an issue with a supervisee, but I know when there is an issue, there is something we have to do if you have a supervisee who is not performing as well, then that’s kind of taken out of your hands and given to a faculty. So they’re like, ‘Yeah you are capable of providing supervision,’ but when there’s an issue it seems like you’re no longer capable.

Another participant noted wanting “to see us do more of the cases where we need to do remediation” in order to be better prepared in identifying critical incidents, thus feeling more capable in the role as supervisor. Discussion on the middle tier proved to be a topic participants both related to and had concerns about. In addition to talking about critical incidents and the remediation process, another emergent theme included people within the participants’ training programs who were influential to their self-efficacy beliefs as supervisors.

Influential People

When asked about influences they had from inside and outside of their training programs, all participants identified people and things (e.g., previous work experience, support of significant others, conferences, spiritual meditation, supervision literature) as factors that affected their perceived abilities as supervisors. The specific factors most often identified by more than half of the participants, however, were the influence of supervisors and supervisees in their training programs.

Supervisors. All participants indicated that interactions with current and previous supervisors influenced their self-efficacy as supervisors. Ten participants reported supervisors modeling their supervision style and techniques as influential. For example, in regard to watching supervision tapes of the faculty supervisors, one participant stated that it has “been helpful for me to see the stance that they [faculty supervisors] take and the model that they use” when developing her own supervision skills. Seven participants also indicated having the space to grow as supervisors as a positive influence on their self-efficacy. One participant explained as follows:

I know people at other universities and it’s like boot camp, they [faculty supervisors] break them down and build them up in their own image like they’re gods. And I don’t feel that here. I feel like I’m able to be who I am and they’re supportive and helping me develop who I am.

In addition to the information provided during the focus groups, 11 focus group participants reiterated on their follow-up questionnaires that faculty supervisors had a positive influence on the development of their self-efficacy. For example, for one participant, “a lot of support from faculty supervisors in terms of their accessibility and willingness to answer questions” was a factor in strengthening her perception of her abilities as a counselor supervisor. Participants also noted the importance of working with their supervisees as beneficial and influential to their perceptions of self-efficacy as supervisors.