School Counselors’ Emotional Intelligence and Comprehensive School Counseling Program Implementation: The Mediating Role of Transformational Leadership

Derron Hilts, Yanhong Liu, Melissa Luke

The authors examined whether school counselors’ emotional intelligence predicted their comprehensive school counseling program (CSCP) implementation and whether engagement in transformational leadership practices mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. The sample for the study consisted of 792 school counselors nationwide. The findings demonstrated the significant mediating role of transformational leadership on the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. Implications for the counseling profession are discussed.

Keywords: emotional intelligence, school counselors, transformational leadership, comprehensive school counseling program, implementation

School counselors have been called upon to design and implement culturally responsive comprehensive school counseling programs (CSCPs) that have a deliberate and systemic focus on facilitating optimal student outcomes and development (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2017, 2019b). To this end, school counselors are expected to align their activities with the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2019b) with an aim toward facilitating students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors to be academically and socially/emotionally successful and preparing students for college and career (ASCA, 2021). Relatedly, ASCA (2019a) urges school counselors to apply and enact a model of leadership in the process of program implementation. Several studies (e.g., Mason, 2010; Mullen et al., 2019; Shillingford & Lambie, 2010) have provided empirical evidence that supports the predictive role of school counselors’ leadership on their program implementation outcomes. Still, little is known about the relationship between school counselors’ program implementation and their leadership practices grounded in a specific model such as transformational leadership (Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995). Understanding this relationship may allow school counselors to better align their practices within a specific leadership framework consistent with best practice (ASCA, 2019a).

Although leadership has been broadly established as a macro-level capability, emotional intelligence has started to gain interest in recent literature, as intra- and interpersonal competencies are central to school counselors’ practice (Hilts et al., 2019; Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Mullen et al., 2018). For instance, school counselors must be emotionally attuned to themselves and others to more effectively navigate the complexities of systems in which they operate (Mullen et al., 2018). One way to achieve such emotional attunement may be by respecting and validating others’ perspectives and providing emotional support to enact interpersonal influence aimed at facilitating educational partners’ keenness toward programmatic efforts (Hilts et al., 2019; Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Jordan & Lawrence, 2009). The purpose of the current study is to examine the mechanisms between school counselors’ emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and CSCP implementation.

Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

Although school counseling programs will vary in structure based on the unique needs of school and community partners (Mason, 2010), programs should be comprehensive in scope, preventative by design, and developmental in nature (ASCA, 2017). CSCP implementation, which comprises a core component of school counseling practice, involves multilevel services (e.g., instruction, consultation, collaboration) and assessments (e.g., program assessments, annual results reports). The functioning of these services and assessments is further defined and managed within the broader school community by the CSCP (Duquette, 2021). Moreover, CSCPs are generally aligned with the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2019b) to create a shared vision among school counselors to have a more deliberate and systemic focus on facilitating optimal student outcomes and development.

Over the past 20 years, researchers have consistently found positive relationships between CSCP implementation and student achievement reflected through course grades and graduation/retention rates (Sink et al., 2008) and achievement-related outcomes such as behavioral issues and attendance (Akos et al., 2019). Students who attend schools with more well established and fully implemented CSCPs are more likely to perform well academically and behaviorally (Akos et al., 2019). Additionally, researchers have found that school counselors who engage in multilevel services associated with a CSCP are more likely to have higher levels of wellness functioning compared to those who are less engaged in delivering these services (Randick et al., 2018). As such, CSCP implementation seems to not only be positively related to student development and achievement but also the overall well-being of school counselors.

Designing and implementing a culturally responsive CSCP demands a collaborative effort between both school counselors and educational partners to create and sustain an environment that is responsive to students’ diverse needs (ASCA, 2017). This ongoing and iterative process requires school counselors to be emotionally attuned with school, family, and community partners to co-construct, facilitate, and lead initiatives to more efficaciously implement equitable services within their programs (ASCA, 2019b; Bryan et al., 2017). School counselors must engage in leadership and be attentive toward their self- and other-awareness and management to traverse diverse contexts involving differences in personalities, values and goals, and ideologies (Mullen et al., 2018). Although researchers have reported that school counselors’ CSCP implementation is positively related to their leadership (e.g., Mason, 2010), no studies have investigated the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence generally refers to the ability to recognize, comprehend, and manage the emotions of oneself and others to accomplish individual and shared goals (Kim & Kim, 2017). Scholars have purported that emotional intelligence can be subsumed into two overarching forms: trait emotional intelligence and ability emotional intelligence (Petrides & Furnham, 2000a, 2000b, 2001). Trait emotional intelligence, also known as trait emotional self-efficacy, involves “a constellation of behavioral dispositions and self-perceptions concerning one’s ability to recognize, process, and utilize emotional-laden information” (Petrides et al., 2004, p. 278). Ability emotional intelligence, also referred to as cognitive-emotional ability, concerns an individual’s emotion-related cognitive abilities (Petrides & Furnham, 2000b). Said differently, trait emotional intelligence is in the realm of an individual’s personality (e.g., social awareness), whereas ability emotional intelligence denotes an individual’s actual capabilities to perceive, understand, and respond to emotionally charged situations.

Over the past two decades, scholars have expanded the scope of emotional intelligence to have a deliberate focus on how emotional intelligence occurs within teams or groups in the workforce context (Jordan et al., 2002; Jordan & Lawrence, 2009). Given the salience of emotions in various professional and work contexts (e.g., Jordan & Troth, 2004), Jordan and colleagues’ (2002) Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile (WEIP) facilitates a better understanding of how emotional intelligence manifests in teams. The WEIP centralizes emotional intelligence around the “understanding of emotional processes” (Jordan et al., 2002, p. 197). Using the WEIP, researchers revealed that higher emotional intelligence scores are positively related to job satisfaction, organizational citizenship (e.g., performing competently under pressure), organizational commitment, and school and work performance (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, 2004). Conversely, higher scores of emotional intelligence were negatively associated with turnover intentions and counterproductive behavior (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b).

Emotional intelligence has also gained increased attention in the counseling literature. For example, Easton et al. (2008) found emotional intelligence as a significant predictor of counseling self-efficacy in the areas of attending to the counseling process and dealing with difficult client behavior. Following a two-phase investigation, Easton and colleagues demonstrated the stability of emotional intelligence during a 9-month timeframe in both groups of professional counselors and counselors-in-training; thus, the researchers argued that emotional intelligence may be an inherent characteristic associated with the career choice of counseling. In an earlier study with a sample with 108 school counselors, emotional intelligence was found to be significantly and uniquely related to school counselors’ multicultural counseling competence (Constantine & Gainor, 2001). More recently, school counselors’ emotional intelligence was found to be positively related to leadership self-efficacy and experience (Mullen et al., 2018).

School Counseling Leadership Practice

Leadership practice is a dynamic, interpersonal phenomenon within which school counselors engage in behaviors that mobilize support from educational partners to achieve programmatic and organizational objectives aimed at promoting student achievement and development (Hilts, Peters, et al., 2022). The focus on leadership practice entails an emphasis on the actual behavior of the individual, which scholars have contended is a byproduct of both individual and contextual factors in which these behaviors occur (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Mischel & Shoda, 1998; Scarborough & Luke, 2008). For instance, school counselors’ support from other school partners (Dollarhide et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2019) and previous leadership experience (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Lowe et al., 2017) have been found to influence school counselors’ engagement in leadership. Hilts, Liu, and colleagues (2022) found that intra- and interpersonal factors significantly predicted school counselors’ engagement in leadership such as multicultural competence, leadership self-efficacy, and psychological empowerment. Across several models of leadership (e.g., Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995), transformational leadership has been situated in the context of school counseling (Gibson et al., 2018).

Transformational School Counseling Leadership

Transformational leadership is described as behaviors aimed at encouraging others to enact leadership, challenge the status quo, and actively pursue learning and development to achieve higher performance (Bolman & Deal, 1997; Kouzes & Posner, 1995). Individuals employing transformational leadership foster a climate of trust and respect and inspire motivation among others by facilitating emotional attachments and commitment to others and the organization’s mission. More recently, Gibson et al. (2018) constructed and validated the School Counseling Transformational Leadership Inventory (SCTLI) in an effort to support school counselors in conceptualizing and informing their approach to leadership. The SCTLI (Gibson et al., 2018)—grounded in the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2012) and the general transformational leadership literature (e.g., Avolio et al., 1991)—offers a framework to support engagement in leadership within a school context. For example, school counselors build partnerships with important decision-makers in the school and community and empower educational partners to act to improve the program and the school. School counselors engaging in transformational leadership ascribe to an egalitarian structure in which they engage in shared decision-making, promote a united vision, and inspire others to work toward positive change among students and the broader school community (Lowe et al., 2017). Beyond being studied as an outcome variable itself (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022), school counselors’ enactment of leadership has also been found to be positively associated with their outcomes of CSCP implementation (Mason, 2010; Mullen et al., 2019).

Emotional Intelligence and the Mediating Role of Transformational Leadership

Over the past several decades, emotional intelligence has been increasingly attributed as a critical trait and ability of individuals employing effective leadership (Kim & Kim, 2017). For instance, Gray (2009) asserted that effective school leaders are able to perceive, understand, and monitor their own and others’ internal states and use this information to guide the thinking and actions of themselves and others. Mullen and colleagues (2018) found that, among a sample of 389 school counselors, domains of emotional intelligence (Jordan & Lawrence, 2009) were significant predictors of leadership self-efficacy and leadership experience. Specifically, Mullen et al.’s (2018) results showed that (a) awareness of own emotions and management of own and others’ emotions were positively related to leadership self-efficacy; (b) management of own and others’ emotions significantly predicted leadership experience; and (c) awareness and management of others’ emotions was positively associated with self-leadership.

Moreover, initial research has revealed that not only is emotional intelligence an antecedent of leadership (Barbuto et al., 2014; Harms & Credé, 2010; Mullen et al., 2018), but that leadership, particularly transformational leadership, mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and job-related behavior such as job performance (Hur et al., 2011; Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020; Rahman & Ferdausy, 2014). For example, Hussein and Yesiltas’s (2020) results indicated that not only were higher scores of emotional intelligence positively associated with organizational commitment, but that transformational leadership partially mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and organizational commitment. In another study, Hur and colleagues (2011) sought to examine whether transformational leadership mediated the link between emotional intelligence and multiple outcomes among 859 public employees across 55 teams. The researchers’ results showed that transformational leadership mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and service climate, as well as between emotional intelligence and leadership effectiveness. Scholars have explained this relationship as the ability of individuals employing transformational leadership to inspire and motivate others to accomplish beyond self- and organizational expectations and redirect feelings of frustration from setbacks to constructive solutions (Hur et al., 2011; Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020).

Purpose of the Study

Taken together, emotional intelligence has been identified in the counseling literature as a significant predictor of counseling self-efficacy and competence (Constantine & Gainor, 2001; Easton et al., 2008). It has also been well established in the workforce literature as being positively related to job performance and leadership outcomes (Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020; Kim & Kim, 2017). The broader leadership literature also comprises evidence in support of the mediating role of transformational leadership between emotional intelligence and performance outcomes (Hur et al., 2011; Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020; Rahman & Ferdausy, 2014). Emotional intelligence has not been examined in relation to school counselors’ CSCP implementation and service outcomes, although CSCP implementation has been widely embraced as a core of the ASCA National Model. Likewise, although emotional intelligence has been studied with counseling practice and leadership separately, we identified no empirical research that has examined the mechanisms between school counselors’ emotional intelligence, transformational leadership practice, and outcomes of program implementation. The present study seeks to address these gaps. Thus, the two research questions that guided our study were: (a) Does school counselors’ emotional intelligence predict their CSCP implementation? and (b) Does engagement in transformational leadership practice mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation? Given the synergistic focus on collaboration (or teamwork) shared by the school and workforce contexts coupled with previous empirical evidence, we hypothesized that (a) school counselors’ emotional intelligence predicts their CSCP implementation, and (b) transformational leadership practice mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation.

Method

Research Design

In the present study, we utilized a correlational, cross-sectional survey design. We used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 27). To test our hypotheses, we performed a mediation analysis using Hayes’s PROCESS in order to establish the extent of influence of an independent variable on an outcome variable (through a mediator; Hayes, 2012). Mediation analysis answered how an effect occurred between variables and is based on the prerequisite that the independent variable/predictor is often considered the “causal antecedent” to the outcome variable of interest (Hayes, 2012, p. 3). Furthermore, we expected that the effects of school counselors’ emotional intelligence on their CSCP implementation would be partly explained by the effects of their engagement in transformational leadership.

Participants

Participants included for final analysis were 792 practicing school counselors in the United States, 94.6% (n = 749) of which reported to be certified/licensed as school counselors and 5.4% (n = 43) indicated to be either not certified/licensed or “unsure.” The sample’s geographic location was mostly suburban (n = 399, 50.4%), followed by rural (n = 195, 24.6%) and urban (n = 184, 23.2%); and 1.8% of participants (n = 14) did not disclose their setting. Public schools accounted for 86.2% (n = 683) of participants’ work settings, followed by charter (n = 42, 5.3%) and private (n = 40, 5.1%), while 3.4% (n = 27) of participants indicated “other” or did not disclose. For grade levels served by participants, 13% (n = 103) worked at the PK–4 level, 20.8% (n = 165) at the 5–8 level, 28.4% (n = 225) at the 9–12 level, and 37.8% (n = 299) worked at the combined K–12 level. Participants’ race/ethnicity included Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n = 26, 3.3%), Multiracial (n = 47, 5.9%), Black/African American (n = 56, 7.1%), Hispanic/Latino (n = 70, 8.8%), and White (n = 593, 74.9%). Lastly, participants’ mean age was 43, ranging from 23 to 77 years of age. Of the 792 participants, 82.4% (n = 653) identified as cisgender female, 11.0% (n = 88) as cisgender male, 0.3% (n = 2) as transgender female, 0.3% (n = 2) as transgender male, 3.8% (n = 30) chose “prefer to self-identify,” and 2.2% (n = 17) chose “not to answer.” Our sample was representative of the larger population based on the results of a recent nationwide study by ASCA (2021), in which approximately 7,000 school counselors were surveyed; demographic statistics from that study similar to ours included 88% of participants working in public, non-charter schools; 19% working at the middle school level; and 24% working in urban schools..

Procedures and Data Collection

Prior to engaging in data collection, we received approval from our university’s IRB. According to our a priori power analysis conducted using G*Power 3.1 Software (Faul et al., 2007), a sample size of 558 participants would be considered sufficient for the current study, assuming a small effect size ( f 2 = 0.1); therefore, we attempted to achieve a nationally representative sample through a variety of recruitment methods. In efforts to represent the target population, non-probability sampling methods (Balkin & Kleist, 2016) were used and included either sending, posting, or requesting dissemination of a research recruitment message and survey link to (a) school counselors of current or former Recognized ASCA Model Program (RAMP)-designated school counseling programs, (b) state school counseling associations, (c) several closed groups on Facebook for school counselors, (d) the ASCA Scene online discussion forum, and (e) the university’s school counselor listserv. In addition, similar to recruitment methods used by Hilts and colleagues (2019) in previous school counseling research, we emailed ASCA members directly with an invitation to participate. We shared one to two follow-up announcements through these same methods between 2 to 4 weeks after the initial recruitment message.

The link within the research recruitment announcement directed participants to an informed consent page. After indicating their willingness to participate in the study, participants were then directed to the online survey managed by the Qualtrics platform. On average, the survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete.

Instrumentation

Demographic Questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire consisted of 18 questions asked of all eligible participants. The demographic form included questions about participants’ school level, geographic location, school type, and student caseload. We also asked participants about other demographic information including race/ethnicity, gender, age, and years of experience.

Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile

The Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile-Short Version (WEIP-S; Jordan & Lawrence, 2009), a shortened version of the WEIP (Jordan et al., 2002) and the WEIP-6 (Jordan & Troth, 2004), is a 16-item, self-report scale that measures participants’ emotional intelligence within a team context. Jordan and Lawrence (2009) selected just 25 behaviorally based items from the 30-item WEIP-6 (Jordan & Troth, 2004). Through confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to achieve the best fit model, the final WEIP-S measure consisted of 16 items with four factors, each of which had good internal consistency reliability in the sample: awareness of own emotions (4 items, ⍺ = .85), management of own emotions (4 items, ⍺ = .77), awareness of others’ emotions (4 items, ⍺ = .88), and management of others’ emotions (4 items, ⍺ = .77). To enhance construct validity of the WEIP-S, Jordan and Lawrence employed model replication analyses and test-retest stability across three time periods. Examples of items from each dimension are (a) “I can explain the emotions I feel to team members” (awareness of own emotions); (b) “When I am frustrated with fellow team members, I can overcome my frustration” (management of own emotions); (c) “I can read fellow team members ‘true’ feelings, even if they try to hide them” (awareness of others’ emotions); and (d) “I can provide the ‘spark’ to get fellow team members enthusiastic” (management of others’ emotions). The items are measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). For analyses, we summed scores of all dimensions, with higher scores indicating a greater amount of emotional intelligence. Cronbach’s ⍺ and McDonald’s omega (ω) for the WEIP-S were both .93, which indicated good internal consistency.

School Counseling Transformational Leadership Inventory

The SCTLI (Gibson et al., 2018) is a 15-item, self-report inventory that measures the leadership practices of school counselors. The items are measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always or almost always) and a total score indicates the self-reported level of engagement in overall leadership practices. Sample items on the SCTLI include “I have empowered parents and colleagues to act to improve the program and the school” and “I have used persuasion with decision-makers to accomplish school counseling goals.” Findings from Gibson et al.’s (2018) exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) and CFAs revealed a one-factor model of transformational leadership practices based on transformational leadership theory and responsibilities as described within the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2019b; CFI = .94, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .08). Through Pearson’s correlation, the researchers revealed that concurrent validity was significant (r = .68, p < .01). Additionally, in their sample, Gibson et al. reported strong internal consistency reliability with a Cronbach’s α = .94. In the current study, Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s (ω) for the SCTLI were .93 and .94, respectively.

School Counseling Program Implementation

The School Counseling Program Implementation Survey-Revised (SCPIS-R; Clemens et al., 2010; Fye et al., 2020) is a self-report survey that measures school counselors’ level of CSCP implementation. The SCPIS-R (Fye et al., 2020), used in the current study, is a 14-item Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not present) to 4 (fully implemented). The factor structure was established through two studies that utilized EFA (Clemens et al., 2010) and CFA (Fye et al., 2020) to test the factor structure. The data from the original study (Clemens et al., 2010) yielded a three-factor model structure of the SCPIS, which includes programmatic orientation (7 items, α = .79), school counselors’ use of computer software (3 items, α = .83), and school counseling services (7 items, α =. 81), and a total SCPIS of α = .87. That said, Fye et al.’s (2020) CFA findings suggested a modified two-factor model was a more appropriate fit; thus, the modified two-factor model structure of the SCPIS includes only programmatic orientation (7 items, α = .86) and school counseling services (7 items, α = .83) and a total SCPIS of α = .90. Examples from each factor are (a) needs assessments are completed regularly and guide program planning (programmatic orientation) and (b) services are organized so that all students are well served and have access to them (school counseling services). We calculated participants’ total SCPIS scores with higher scores indicating greater CSCP implementation (Mason, 2010; Mullen et al., 2019). In the present study, the SCPIS-R demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .90; McDonald’s ω = .90) in our sample.

Data Analysis

Missing Data Analysis and Assumptions Test

We received a total of 1,128 responses. Of all these responses, 336 respondents missed a significant portion (over 70%) of one or more of the main scales (i.e., WEIP-S, SCTLI, and SCPIS-R). We assessed this portion of values as not missing completely at random (NMCAR), and we proceeded with employing listwise deletion to 336 cases. The data NMCAR may be because of the survey length and time commitment, which is discussed more in the Limitations section. With the remaining 792 cases, the missing values counted for 0.1%–0.7% of missing values across respective scales. We performed a Little’s Missing Completely at Random test using SPSS Statistics Version 26.0 with a nonsignificant chi-square value (p > .05), which suggested that the missing values (across cases) were missed completely at random. Therefore, we retained all 792 cases and followed multiple imputation (Scheffer, 2002) to replace the missing values, using SPSS. Our data met assumptions for mediation analysis, normality based on histograms, and linearity and homoscedasticity as demonstrated through the scatterplots generated from univariate analysis.

Mediation Analysis

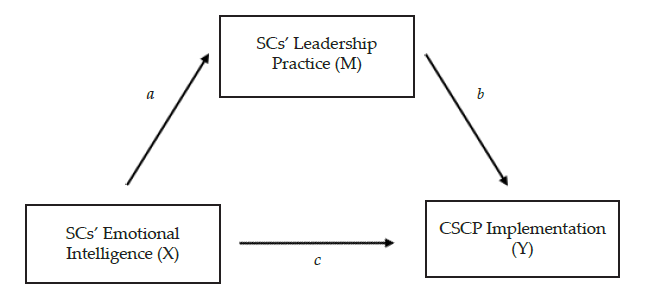

In our mediation model (see Figure 1), given its combined trait-ability nature and stability over time, school counselors’ emotional intelligence was hypothesized as the causal antecedent to program implementation; we then hypothesized transformational leadership practice to be a mediator for the effect of school counselors’ emotional intelligence on program implementation. We tested our mediation model based on Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach. Specifically, our mediation analysis entailed four steps involving (a) the role of school counselors’ emotional intelligence (X) in predicting CSCP implementation (Y), with the coefficient denoted as c to reflect the total effect that X has on Y; (b) the predictive role of school counselors’ emotional intelligence (X) on transformational leadership practice (M), with the coefficient denoted as a; (c) the effect of transformational leadership practice (M) on CSCP implementation (Y), controlling for the effect of emotional intelligence (X), with the coefficient denoted as b; and (d) the association between school counselors’ emotional intelligence (X) and CSCP implementation (Y), using transformational leadership practice (M) as a mediator with coefficient denoted as c’ (MacKinnon et al., 2012). The difference between the coefficients c and c’,

(c – c’), is the mediation effect of transformational leadership practice.

Figure 1

The Hypothesized Mediation Model

Note. SC = school counselors; CSCP = Comprehensive School Counseling Program.

Hayes’s PROCESS v3.5 (with 5,000 regenerated bootstrap samples) was used to perform the mediation analysis. Hayes’s PROCESS is an analytical function in SPSS used to specify and estimate coefficients of specified paths using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression (Hayes, 2012). We consulted Fritz and MacKinnon (2007) regarding sample adequacy for detecting a mediation effect. Specifically, in order to allow .80 power and a medium mediation effect size, a sample of 397 is recommended for Baron and Kenny’s test, and a sample of 558 is considered adequate to detect small effects via percentile bootstrap (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). As such, our sample size of 792 met both criteria. According to MacKinnon et al. (2012), the mediation effect is significant, if zero (0) is excluded from the designated confidence interval (95% in our study).

Results

Correlations

We performed a bivariate analysis on the main study variables of school counselors’ emotional intelligence (measured using the WEIP-S), transformational leadership practice (measured using the SCTLI), and school counselors’ CSCP implementation (measured using the SCPIS-R). School counselors’ emotional intelligence scores were positively correlated with their transformational leadership practice (r = .42, p < .001) and were positively correlated with their CSCP implementation (r = .34, p < .001). Similarly, school counselors’ transformational leadership practice was found to be positively correlated with CSCP implementation (r = .56, p < .001). Table 1 denotes the correlations among variables.

Table 1

Correlation Matrix of Study Variables

| Variable | EI | TL | CSCP |

| EI | – | .42** | .34** |

| TL | .42** | – | .56** |

| CSCP | .34** | .56** | – |

Note. EI = school counselors’ emotional intelligence scores; TL = school counselors’ transformational

leadership; CSCP = school counselors’ comprehensive school counseling program implementation.

**p < .001

Mediation Analysis Results

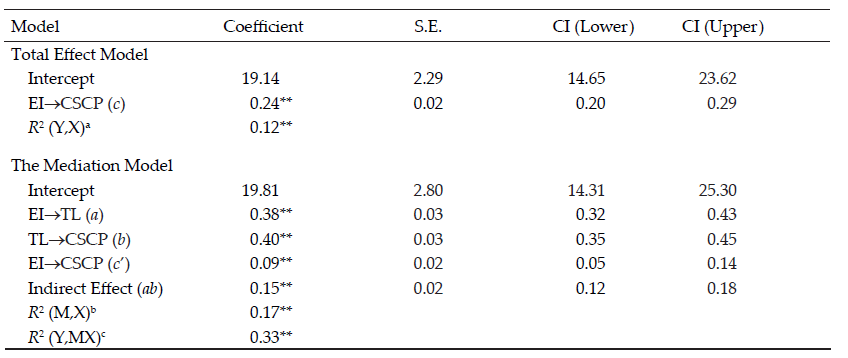

With the total effect model (Step 1), we found a positive relation between school counselors’ emotional intelligence (X) and their CSCP implementation (Y; coefficient c = 0.24; p < .001; CI [0.20, 0.29]). Namely, school counselors’ emotional intelligence scores significantly predicted their CSCP implementation. In Step 2, we found a positive association between school counselors’ emotional intelligence scores (X) and their transformational leadership practice (M; coefficient a = 0.38; p < .001; CI [0.32, 0.43]). In Step 3, school counseling transformational leadership practice (M) was found to significantly predict their CSCP implementation (Y; coefficient b = 0.40; p < .001, CI [0.35, 0.45]) while controlling for the effect of emotional intelligence (X). Lastly, after adding transformational leadership practice as a mediator, we noted a significant direct effect of emotional intelligence on school counselors’ CSCP implementation (coefficient c’ = 0.09; p = .0001; CI [0.05, 0.14]). We also detected a mediation effect (coefficient ab = 0.15 which equaled c – c’; p < .001; CI [0.12, 0.18]) of emotional intelligence on CSCP implementation through transformational leadership practice. The 95% confidence intervals did not include zero (0), so the path coefficients were significant.

We performed a Sobel test to further evaluate the significance of the mediation effect by school counseling transformational leadership practice, which yielded a Sobel test statistic of 9.97 with a p value of < .001. The Sobel outcome corroborated the significance of our mediated effect. To calculate the effect size of our mediation analysis, we generated kappa-squared value (k2; Preacher & Kelley, 2011). Our kappa-squared (k2) value of .17 suggested a medium effect size (Cohen, 1988). Table 2 demonstrates regression results for the effect of school counselors’ emotional intelligence on their CSCP implementation outcomes mediated by transformational leadership practice.

Table 2

Regression Results for Mediated Effect by Leadership Practice

Note. N = 792. EI = emotional intelligence; TL = transformational leadership; CSCP = comprehensive school counseling program; CI = 95% Confidence Interval. The 95% CI for ab is obtained by the bias-corrected bootstrap with 5,000 resamples.

aR2 (Y,X) is the proportion of variance in CSCP implementation explained by EI.

bR2 (M,X) is the proportion of variance in TL explained by EI.

cR2 (Y,MX) is the proportion of variance in CSCP implementation explained by EI and TL.

**p < .001.

Discussion

In this national sample of 792 practicing school counselors, we examined whether school counselors’ emotional intelligence predicts their CSCP implementation. We also investigated whether engagement in transformational leadership practice mediated the relationship between school counselors’ emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. First, we found that school counselors who reported higher scores of emotional intelligence were also more likely to score higher in CSCP implementation. Given that designing and implementing a CSCP requires school counselors to engage in a culturally responsive and collaborative effort (ASCA, 2017), our result that suggested emotional intelligence is positively correlated with CSCP implementation is not entirely unpredicted. This result was consistent with previous evidence supporting the positive correlation between emotional intelligence and work performance (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, 2004). The result also illustrated the predictive role of school counselors’ emotional intelligence on their CSCP implementation, beyond its significant association with counseling competencies (Constantine & Gainor, 2001; Easton et al., 2008).

Secondly, school counselors’ emotional intelligence was found to be positively associated with their engagement in transformational leadership. This result aligned with previous evidence that school counselors’ emotional intelligence is linked to leadership outcomes demonstrated through the workforce literature (Barbuto et al., 2014; Harms & Credé, 2010; Kim & Kim, 2017). Similarly, the result echoed Mullen et al.’s (2018) finding on the positive relationship between school counselors’ emotional intelligence and leadership scores measured by the Leadership Self-Efficacy Scale (LSES; Bobbio & Manganelli, 2009). Noteworthily, the LSES was normed and validated with college students. Our results advanced the school counseling literature and corroborated the relationship between emotional intelligence and school counseling transformational leadership measured by the SCTLI, a scale developed specifically for school counselors. Our results suggest that school counselors may actively attend to emotional processes in order to effectively enact transformational leadership practice.

Thirdly, we found that school counselors’ engagement in transformational leadership significantly mediated the relationship between their emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. Because leadership is woven into the ASCA National Model and is considered an integral component of a CSCP (ASCA, 2019b), and school counselors are required to develop collaborative partnerships with a range of educational partners (ASCA, 2019a; Bryan et al., 2017), we were not surprised to find these two concepts were related to CSCP implementation. This result also aligns with empirical evidence in the broader leadership literature that transformational leadership mediated the relationship between emotional intelligence and work performance (Hur et al., 2011; Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020). This result is particularly meaningful in that it demonstrates school counseling leadership as either a significant predictor (Mason, 2010; Mullen et al., 2019) or an outcome variable itself (Hilts, Liu, et al., 2022; Mullen et al., 2018). It enables a more nuanced understanding of mechanisms involved in emotional intelligence, leadership, and program implementation in a school counseling context. To our best knowledge, the current study was the first study that found that through leadership practice, school counselors’ emotional intelligence may offer an indirect effect on their CSCP implementation.

Implications

Results of this study have implications for school counselor practice and school counselor training and supervision. Given the significant relationships between emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and CSCP implementation, we suggest that practicing school counselors begin by assessing their emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and CSCP implementation and then set goals to enhance their performance. This may be especially important considering that other research has suggested that school counselors’ engagement in leadership, as well as their other roles and responsibilities (e.g., multicultural competence; challenging co-workers about discriminatory practices) have changed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Hilts & Liu, 2022). For instance, Hilts and Liu’s (2022) results indicated that school counselors’ leadership practice scores were higher during the pandemic compared to prior to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Next, school counselors can seek resources and professional development opportunities to support their goals. For example, school counselors may benefit from professional development focused on social-emotional learning (SEL), given SEL’s competency approach to building collaborative relationships (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, n.d.). That said, school counselors should also seek supports to experientially integrate their intrapersonal, interpersonal, and systemic skills associated with emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and CSCP implementation. Intentional application of the Model for Supervision of School Counseling Leadership (Hilts, Peters, et al., 2022) may provide one such example for both school counseling practitioners and those in training.

School counselor training programs can also identify meaningful opportunities to infuse emotional intelligence and transformational leadership into school counselor coursework and supervision. Scarborough and Luke (2008) identified the important role of exposure in training to models of successful CSCP implementation and related resources on subsequent self-efficacy. As such, not only can school counseling coursework infuse the ASCA National Model Implementation Guide: Manage & Assess (ASCA, 2019b) and the Making DATA Work: An ASCA National Model publication (ASCA, 2018) along with additional emotional intelligence and transformational leadership resources, school counseling faculty and supervisors should intentionally incorporate school counseling students’ ongoing exposure to practicing school counselors and supervisors with high scores of emotional intelligence and transformational leadership.

Limitations

As with all research, the results of this study need to be understood in consideration of the methodological strengths and limitations. Despite obtaining a large national sample, the data collection procedures used in this study prevented our ability to determine the survey response rate. As such, we are unable to make any claim about non-response bias and it is possible that school counselors who declined to participate significantly differed from those who completed the study. Relatedly, the sample included a proportionately large number of participants who started the survey but did not finish. It is possible that the attrition of these school counselors reflected an as of yet unidentified confounding construct that is also related to the variables under study (Balkin & Kleist, 2016). Our sample is nonetheless generally representative of the national school counselor demographic data reported in the recent state of the profession survey of approximately 7,000 school counselors (ASCA, 2021), strengthening the validity and subsequent generalizability of our results.

Another limitation of our study is that all data were cross-sectional and non-experimental. The correlation and mediation analyses used in the study demonstrate the strength of associations between the examined constructs, and do not reflect temporal or causal relationships. The cross-sectional design does not allow statistical control for the predictor and outcome variables; thus, it may not accurately specify the effect of the predictor on the mediator (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). Therefore, any inclination to impose intuitive logic or imbue directionality that emotional intelligence is an antecedent to either transformational leadership or CSCP implementation should be interpreted with caution. Further, all data from this study were collected at the same time and relied upon self-report. As such, common-method variance could have inflated the identified relationships between the constructs.

An important consideration is that this study was delineated to focus on illustrating individual path coefficients between emotional intelligence, leadership, and CSCP implementation and provides limited insight into understanding of complex relationships among latent variables. Likewise, we used Hayes’s PROCESS to examine our mediation model which features procedure rather than overall model fit created through more sophisticated statistical analyses such as structural equation modeling (SEM). Given that PROCESS is a modeling tool that relies on OLS regression, it may be biased in estimating effects without taking into consideration measurement error (Darlington & Hayes, 2017).

Suggestions for Future Research

The results of this study have numerous implications for future research. Future studies may explore the relationship between emotional intelligence and other forms of leadership prevalent in the counseling literature, such as charismatic democratic or servant leadership (Hilts, Peters, et al., 2022). In addition, because self-report emotional intelligence measures have been described as better to assess intrapersonal processes and ability emotional intelligence measures have been shown to be related to emotion-focused coping and work performance (Miao et al., 2017a, 2017b), future research may consider incorporating ability and mixed emotional intelligence measurements to examine a causal model of emotional intelligence and transformational leadership (or other forms of leadership).

Future research could extend the unit of analysis in this study (e.g., individual school counselor) and adopt a similar perspective to Lee and Wong (2019) to examine emotional intelligence in teams. Studies could similarly expand the use of self-report emotional intelligence measures and include ability or mixed emotional intelligence measurement. Relatedly, as Miao et al. (2017b) described significant moderator effects of emotional labor demands of jobs on the relationship between self-report emotional intelligence and job satisfaction, future research could assess this in the school counseling context, wherein the emotional labor demands of the work may vary. Given the robust workforce literature grounding associations between emotional intelligence and job performance, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and resilience in the face of counterproductive behavior in the workplace (Hussein & Yesiltas, 2020), future school counseling research can examine emotional intelligence and other constructs, including ethical decision-making, belonging, attachment, burnout, and systemic factors.

Lastly, as most constructs involved in school counseling practice are latent variables in nature, we recommend future scholars consider SEM when it comes to investigating overall model fit between the variables of interest. SEM offers more specification to the model including goodness of fit of the model to the data (Hayes et al., 2018). It minimizes bias involved in mediation effect estimation with consideration of individual indicators for each latent variable (Kline, 2016).

Conclusion

As an initial examination of the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation, as well as the role of school counselors’ transformational leadership in mediating the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation, this study was grounded in the empirical scholarship on leadership in both school counseling and allied fields. We found support for our hypothesized model of school counselors’ emotional intelligence and their CSCP implementation, mediated by their engagement in transformational leadership. Our examination yielded evidence in support of the significant mediating role of school counselors’ transformational leadership engagement on the relationship between emotional intelligence and CSCP implementation. In the meantime, our results supported the robust reliability of three instruments in our sample: the WEIP-S (Jordan & Lawrence, 2009), the SCTLI (Gibson et al., 2018), and the SCPIS-R (Clemens et al., 2010; Fye et al., 2020), which can be useful for future school counseling researchers and practitioners. This study serves as an important necessary step in establishing these relationships, and we anticipate that our results will ground further investigation related to school counselors’ emotional intelligence, leadership practices, and CSCP implementation, including the development of additional measurements.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

This study was partially funded by Chi Sigma

Iota International’s Excellence in Counseling

Research Grants Program.

References

Akos, P., Bastian, K. C., Domina, T., & de Luna, L. M. M. (2019). Recognized ASCA Model Program (RAMP) and student outcomes in elementary and middle schools. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X19869933

American School Counselor Association. (2012). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2017). The school counselor and school counseling programs.

https://schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-School-Counseling-Program

American School Counselor Association. (2018). Making data work: An ASCA National Model publication (4th ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2019a). ASCA school counselor professional standards & competencies. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/a8d59c2c-51de-4ec3-a565-a3235f3b93c3/SC-Competencies.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2019b). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2021). ASCA research report: State of the profession 2020. https://www.sch

oolcounselor.org/getmedia/bb23299b-678d-4bce-8863-cfcb55f7df87/2020-State-of-the-Profession.pdf

Avolio, B. J., Waldman, D. A., & Yammarino, F. J. (1991). Leading in the 1990s: The four I’s of transformational leadership. Journal of European Industrial Training, 15(4), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090599110143366

Balkin, R. S., & Kleist, D. M. (2016). Counseling research: A practitioner-scholar approach. American Counseling Association.

Barbuto, J. E., Gottfredson, R. K., & Searle, T. P. (2014). An examination of emotional intelligence as an antecedent of servant leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(3), 315–323.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051814531826

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bobbio, A., & Manganelli, A. M. (2009). Leadership Self-Efficacy Scale. A new multidimensional instrument. TPM–Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 16(1), 3–24. https://www.tpmap.org/wp-content/

uploads/2014/11/16.1.1.pdf

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1997). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Bryan, J. A., Young, A., Griffin, D., & Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2017). Leadership practices linked to involvement in school–family–community partnerships: A national study. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18761897

Clemens, E. V., Carey, J. C., & Harrington, K. M. (2010). The school counseling program implementation survey: Initial instrument development and exploratory factor analysis. Professional School Counseling, 14(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1001400201

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum. https://www.ut

stat.toronto.edu/~brunner/oldclass/378f16/readings/CohenPower.pdf

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (n.d.). SEL in school districts. https://casel.org/systemic-implementation/sel-in-school-districts

Constantine, M. G., & Gainor, K. A. (2001). Emotional intelligence and empathy: Their relation to multicultural counseling knowledge and awareness. Professional School Counseling, 5(2), 131–137.

Darlington, R. B., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Regression analysis and linear models: Concepts, applications, and implementation. Guilford.

Dollarhide, C. T., Gibson, D. M., & Saginak, K. A. (2008). New counselors’ leadership efforts in school counseling: Themes from a year-long qualitative study. Professional School Counseling, 11(4), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0801100407

Duquette, K. (2021). “We’re powerful too, you know?” A narrative inquiry into elementary school counselors’ experiences of the RAMP process. Professional School Counseling, 25(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20985831

Easton, C., Martin, W. E., Jr., & Wilson, S. (2008). Emotional intelligence and implications for counseling

self-efficacy: Phase II. Counselor Education and Supervision, 47(4), 218–232.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2008.tb00053.x

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

Fye, H. J., Memis, R., Soyturk, I., Myer, R., Karpinski, A. C., & Rainey, J. S. (2020). A confirmatory factor analysis of the school counseling program implementation survey. Journal of School Counseling, 18(24). http://www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v18n24.pdf

Gibson, D. M., Dollarhide, C. T., Conley, A. H., & Lowe, C. (2018). The construction and validation of the school counseling transformational leadership inventory. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2017.1399246

Gray, D. (2009). Emotional intelligence and school leadership. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 4(4), n4.

Harms, P. D., & Credé, M. (2010). Emotional intelligence and transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051809350894

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper].

Hayes, A. F., Montoya, A. K., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal, 25(1), 76–81.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

Hilts, D., Kratsa, K., Joseph, M., Kolbert, J. B., Crothers, L. M., & Nice, M. L. (2019). School counselors’ perceptions of barriers to implementing a RAMP-designated school counseling program. Professional School Counseling, 23(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X19882646

Hilts, D., & Liu, Y. (2022). School counselors’ perceived school climate, leadership practice, psychological empowerment, and multicultural competence before and during COVID-19. Niagara University [Unpublished manuscript].

Hilts, D., Liu, Y., Li, D., & Luke, M. (2022). Examining ecological factors that predict school counselors’ engagement in leadership practices. Professional School Counseling, 26(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X221118042

Hilts, D., Peters, H. C., Liu, Y., & Luke, M. (2022). The model for supervision of school counseling leadership. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2022.2032871

Hur, Y., van den Berg, P. T., & Wilderom, C. P. M. (2011). Transformational leadership as a mediator between emotional intelligence and team outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 591–603.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.002

Hussein, B., & Yesiltas, M. (2020). The influence of emotional intelligence on employee’s counterwork behavior and organizational commitment: Mediating role of transformational leadership. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 71, 377–402. https://doi.org/10.33788/rcis.71.23

Jordan, P. J., Ashkanasy, N. M., Härtel, C. E., & Hooper, G. S. (2002). Workgroup emotional intelligence: Scale development and relationship to team process effectiveness and goal focus. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00046-3

Jordan, P. J., & Lawrence, S. A. (2009). Emotional intelligence in teams: Development and initial validation of the short version of the Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile (WEIP-S). Journal of Management and Organization, 15(4), 452–469. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1833367200002546

Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2004). Managing emotions during team problem solving: Emotional intelligence and conflict resolution. Human Performance, 17(2), 195–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1702_4

Kim, H., & Kim, T. (2017). Emotional intelligence and transformational leadership: A review of empirical studies. Human Resource Development Review, 16(4), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484317729262

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1995). The leadership challenge: How to keep getting extraordinary things done in organizations (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Lee, C., & Wong, C.-S. (2019). The effect of team emotional intelligence on team process and effectiveness. Journal of Management & Organization, 25(6), 844–859. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.43

Lowe, C., Gibson, D. M., & Carlson, R. G. (2017). Examining the relationship between school counselors’ age, years of experience, school setting, and self-perceived transformational leadership skills. Professional School Counseling, 21(1b), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18773580

MacKinnon, D. P., Cheong, J., & Pirlott, A. G. (2012). Statistical mediation analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 313–331). American Psychological Association.

Mason, E. C. M. (2010). Leadership practices of school counselors and counseling program implementation. National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin, 94(4), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636510395012

Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23

Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., & Qian, S. (2017a). A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and work attitudes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 177–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12167

Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., & Qian, S. (2017b). Are the emotionally intelligent good citizens or counterproductive? A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and its relationships with organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.015

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1998). Reconciling processing dynamics and personality dispositions. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 229–258. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.229

Mullen, P. R., Gutierrez, D., & Newhart, S. (2018). School counselors’ emotional intelligence and its relationship to leadership. Professional School Counseling, 21(1b), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18772989

Mullen, P. R., Newhart, S., Haskins, N. H., Shapiro, K., & Cassel, K. (2019). An examination of school counselors’ leadership self-efficacy, programmatic services, and social issue advocacy. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 6(2), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2019.1590253

Petrides, K. V., Frederickson, N., & Furnham, A. (2004). The role of trait emotional intelligence in academic performance and deviant behavior at school. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 277–293.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00084-9

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2000a). Gender differences in measured and self-estimated trait emotional intelligence. Sex Roles, 42, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007006523133

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2000b). On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(2), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00195-6

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15(6), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.416

Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022658

Rahman, S., & Ferdausy, S. (2014). Relationship between emotional intelligence and job performance mediated by transformational leadership. NIDA Development Journal, 54(4), 122–153. https://doi.org/10.14456/ndj.2014.1

Randick, N. M., Dermer, S., & Michel, R. E. (2018). Exploring the job duties that impact school counselor wellness: The role of RAMP, supervision, and support. Professional School Counseling, 22(1).

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18820331

Robinson, D. M., Mason, E. C. M., McMahon, H. G., Flowers, L. R., & Harrison, A. (2019). New school counselors’ perceptions of factors influencing their roles as leaders. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X19852617

Scheffer, J. (2002). Dealing with missing data. Research Letters in the Information and Mathematical Sciences, 3, 153–160. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/4355

Shillingford, M. A., & Lambie, G. W. (2010). Contribution of professional school counselors’ values and leadership practices to their programmatic service delivery. Professional School Counseling, 13(4), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1001300401

Sink, C. A., Akos, P., Turnbull, R. J., & Mvududu, N. (2008). An investigation of comprehensive school counseling programs and academic achievement in Washington state middle schools. Professional School Counseling, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0801200105

Van Rooy, D. L., & Viswesvaran, C. (2004). Emotional intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive

validity and nomological net. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 71–95.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00076-9

Derron Hilts, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at Niagara University. Yanhong Liu, PhD, NCC, is an associate professor at Syracuse University. Melissa Luke, PhD, NCC, is a dean’s professor at Syracuse University. Correspondence may be addressed to Derron Hilts, 5795 Lewiston Rd, Niagara University, NY 14109, dhilts@niagara.edu.