Dec 9, 2015 | Article, Volume 5 - Issue 4

Lindsey Mitchell

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship of five variables—primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills, social support and stigma—to bereavement among women whose military spouses had completed suicide. Four correlations to bereavement (primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills and stigma) were significant. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis assessed the overall relationship of bereavement (the criterion variable) to the five predictor variables, along with the unique contribution of each predictor variable. In the regression, five of six models (all except Model 4) showed significance. The dissertation on which this manuscript is based has the following practical implications: statistically significant correlations between bereavement and constructs of Lazarus’ Cognitive Model of Stress (LCMS), as well as the significance of Lazarus’ construct of primary appraisal within Model 6, indicate that LCMS holds promise for understanding symptoms of bereavement in women whose military spouses have completed suicide.

Keywords: suicide, bereavement, military, spouse, Lazarus

Reports indicate that suicides in the U.S. military surged to a record number of 349 in 2013. This figure far exceeds the 295 American combat deaths in Afghanistan in 2012 and compares with the 201 military suicides in 2011 (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2013). Some private experts predict that the trend will worsen this year (Miles, 2010).

From 2008–2010, the Army reported the highest number of suicides (n = 182) among active duty troops; whereas the Navy and Air Force reported 60 and 59 respectively (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2013). The Marine Corps had the largest percentage increase in suicides in a period of 2 years (Lamorie, 2011). U.S. veterans accounted for 20% of the more than 30,000 suicide deaths in the United States in 2009. Between 2003 and 2009, approximately 6,000 veterans committed suicide annually, an average of 18 suicides each day (Congressional Quarterly, 2010; Miles, 2010). During the 2009 fiscal year, 707 members of the veteran population committed suicide, and another 10,665 made unsuccessful suicide attempts (Miles, 2010). Certain experiences of military service members (e.g., exposure to violence, act of killing the enemy, risk of injury, exposure to trauma) increase suicidal tendencies (Zamorski, 2011).

For every person who completes suicide, an estimated 20 people experience trauma related to the death (NIMH, 2010). This suggests that from the 349 military suicides in 2013, approximately 7,000 people have experienced related trauma. Suicide survivors are family members and friends whose lives significantly change because of the suicide of a loved one (Andriessen, 2009; Jordan & McIntosh, 2011; McIntosh, 1993). Survivors of suicide may have higher risk for a variety of psychological complications, including elevated rates of complicated grief and even reactive suicide (Agerbo, 2005).

It is also important to note that suicide survivors might not differ significantly from other bereaved groups regarding general mental health, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and anxiety (Sveen & Walby, 2008). Examining the impact of suicide on surviving military family members may provide important information on minimizing negative consequences, including possible survivor suicide.

Military deaths are often sudden, unexpected, traumatic and/or violent in nature, and the family is conditioned to anticipate these types of deaths. In contrast, death by suicide is not anticipated and might not be handled well among military families (Martin, Ghahramanlou-Holloway, Lou, & Tucciarone, 2009). Suicide within the military culture is a traumatic as well as a unique experience. Service members and their families struggle with the visible and invisible wounds of war and the aftermath that combat deaths leave for the survivors. When a service member’s trauma leads to suicide, the military community is less trained and conditioned to process the grief than when death occurs as a direct result of military service (Zhang & Jia, 2009).

Stress plays a role in the grief process within the military culture when it relates to suicide. The chief identifying feature of military culture is warfare, which in turn leads to the claiming of human lives (Siebrecht, 2011). Siebrecht argued that bereavement can only be overcome if people adopt a more rational attitude and grant death its natural place in life. Association with the military ensures that most families will have to experience some form of bereavement and many forms of loss during times of war (Audoin-Rouzeau & Becker, 2002). Military men and woman are less equipped than the general population when it comes to their culture’s acceptance of outward demonstration or sharing of the emotional experience of grief (Doka, 2005).

Stigma

Historically, the stigma of suicide has been present in society (Cvinar, 2005). The biggest obstacles that families with members who have completed suicide confront are acts of informal social disapproval. The surviving family may be suspected of being partly blameworthy in a suicide death and consequently may be subjected to informal isolation and shunning (Bleed, 2007). The stigma of suicide can be subtle. It can be manifested in overt actions taken against the survivors (i.e., placing blame on the family), as well as by omitted actions (i.e., not receiving life insurance), which are probably far more common. When people experience the untimely loss of a family member, there can be feelings of being offended, wounded or abandoned (Neimeyer & Jordan, 2002). The stigmatization experienced by survivors may complicate their bereavement process (Cvinar, 2005; Jordan, 2001; McIntosh, 1993). This complexity results in communication issues, social isolation, projection of guilt, blaming of others and scapegoating (Harwood, Hawton, Hope, & Jacoby, 2002; Lindemann & Greer, 1953). There is a lack of research in the professional literature addressing the grief of surviving military family members impacted by the death, including suicide, of a loved one (Lamorie, 2011).

Suicide and Bereavement

Jordan (2001) researched suicide bereavement and concluded that there are several underlying reasons that it differs from other types of mourning. Jordan summarized that “there is considerable evidence that suicide survivors are viewed more negatively by others and by themselves” (p. 93) and that suicide “is distinct in three significant ways: the thematic content of grief, the social processes surrounding the survivor, and the impact suicide has on family systems” (p. 91). In reviewing the social processes surrounding suicide, Jordan’s analysis supports those of Worden (1991) and Ness and Pfeffer (1990), saying that “there is considerable evidence that survivors feel more isolated and stigmatized than other mourners, and may be viewed more negatively by others in their social network” (p. 93). Most traumatic death survivors will face questions regarding their own culpability in their loved one’s decision to take his or her own life. Survivors may find themselves repeatedly pondering missed warning signs and risk factors (Parrish & Tunkle, 2005). Four primary factors that distinguish the complexities of suicide bereavement for families include stigma, questions about reasons, issues of remorse and guilt, and various logistical and legal factors unique to suicide that necessarily influence the events and processes following death (Minois,1999). The question of why often comes up given the pervasive sense that suicide is a preventable event. This line of thought can often define the grief process. Combined with factors of shock from the sudden, often violent nature of the death, these questions are virtually unavoidable. In some cases, answers to questions of why may never be forthcoming or satisfactory (Steel, Dunlavy, Stillman, & Pape, 2011). Among military families, bereavement is complex. A military death often has circumstances not normally found in the civilian world. It is most likely unexpected, potentially traumatic, occurring in another country, publicized by the media, and enveloped in the commitment to duty and country. Surviving family members of military personnel are often parents, siblings, grandparents and spouses. Military widows are young, often with young families, and are living at a duty station, far away from family and longtime friends (Katzenell, Ash, Tapia, Campino, & Glassberg, 2012).

Bereavement in the Military Culture

Bereavement is a part of the military culture but is often misinterpreted as a weakness that will elicit limited outside support. Military men and women in general are uninformed about the cultural acceptability of outwardly demonstrating their grief or sharing the emotional experience of the loss (Doka, 2005). Although traditional mental health treatments predominantly encourage emotional vulnerability, the military culture values emotional toughness (Kang, Natelson, Mahan, Lee, & Murphy, 2003) and stigmatizes mental illness (Doka, 2005). These attitudes can often deter service members from seeking assistance that could help them to overcome physical and mental health issues. Military culture affects the impact of suicide on families. Each spouse and family has a different bereavement process, and this process is influenced by stigma, social support and ability to cope. In the U.S. military, these issues can be a hindrance to seeking services and can lead to feelings of isolation, which in turn are a risk factor for suicide (Christensen & Yaffe, 2012).

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework of Lazarus’ Cognitive Model of Stress (LCMS) was used to frame this study. The underlying construct of this model states that times of uncertainty and difficulty may assist in understanding a person’s ability and capacity to cope with the suicide of a loved one. In general, when people encounter a difficult situation, they employ strategies for dealing with and lessening perceived stress (Groomes & Leahy, 2002).

LCMS (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) has served as a useful lens for examining the interaction between a person and situational demands. Burton, Farley, and Rhea (2009) used LCMS to frame a study of the relationship between level of perceived stress and extent of physical symptoms of stress, or somatization, among spouses of deployed versus non-deployed servicemen. Eberhardt and associates (2006) examined Lazarus and Folkman’s 1984 stress theory regarding the ways that stress mediators and perceived social support may affect anxiety (as a stress response). The above studies show the usefulness of LCMS in depicting the impact of stress and coping on perceived anxiety, acceptance, ability to lead mentally and physically satisfactory lives, and perception of social support.

LCMS includes primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping and perceived social support. Stress is defined as a person’s relationship to his or her environment, specifically a relationship that the person perceives as exceeding his or her resources and endangering well-being. This model supports that the person and the environment are in a dynamic, reciprocal and multidimensional relationship. This conceptualization suggests that people’s perception of stress is related to the way they evaluate, appraise and cope with difficulties.

Stress can be measured by the way an individual appraises a specific encounter. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) presented two types of appraisal. The first is primary appraisal, defined as an individual’s expressed concern in terms of harm, loss, threat or challenge. Harm and loss appraisals refer to loss or damage that has already taken place; threat appraisal refers to harm or loss that has not yet occurred (i.e., anticipatory loss); and challenge appraisal refers to the opportunity for mastery or growth (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The second type is secondary appraisal, defined as the focus on what the individual can do to overcome or prevent harm. Lazarus and Folkman suggested that an appraisal of threat is associated with coping resources that can mediate the relationship between stressful events (e.g., loss of spouse to suicide) and outcomes (e.g., ability to seek mental health services).

Coping resources are the personal factors that people use to help them manage situations that are appraised as stressful (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Coping resources can be available to the person during the grief process or can be obtained as needed. This fact suggests that the grief process following a suicide is stressful and imposes demands on coping as the bereavement process evolves. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined coping as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external or internal demands that are appraised as exceeding the resources of the person” (p. 141). Coping is a dynamic process that is called into action whenever people are faced with a situation that requires them to engage in some special effort to manage that situation (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The ability to cope impacts a person’s bereavement process, and the ways and ability to cope vary with each individual. Stigma and the amount of perceived social support also influence the ability to cope (Bandura, 1997). These variables impact the bereavement process, especially with the added variable of death by suicide.

Social support can strengthen an individual’s position against the stressor and reduce the level of threat (Lazarus, 1996). Research suggests there are specific reasons why survivors do not seek out social support. McMenamy, Jordan, and Mitchell (2008) identified depression and a lack of energy as substantial barriers to obtaining social support.

People who experience a traumatic event are more likely to perceive barriers and not request medical and mental health services due to this lack of energy, lack of trust in professionals and depression (Amaya-Jackson et al., 1999). Provini, Everett, and Pfeffer (2000) stated that the stigma and social isolation that survivors experience can interfere with seeking social support and the willingness of social support networks to come to the aid of the survivor. A lack of social support can increase depression, a lack of energy to complete daily tasks and isolation. Limited social support is especially common for suicide survivors. Shame and guilt surrounding a suicide can impact survivors’ ability to seek social support; however, high social support can be linked to positive mental health.

Barriers to Bereavement

Many suicide survivors struggle with questions about the meaning of life and death, report feeling more isolated and stigmatized, and have greater feelings of abandonment and anger compared with other sudden death survivors (Callahan, 2000). Moreover, the feeling of relief from no longer having to worry about the deceased may distinguish survivors of suicide from survivors of other types of sudden death (Jordan, 2001). Experiencing suicide in one’s family increases risks for family members’ mental health and family relationships (Jordan, 2001). Despite the frequency of suicide, there is limited research focusing on the needs of surviving spouses (Miers, Abbott, & Springer, 2012).

The family system in which the spouses existed as a couple is destabilized by suicide, but the survivor must continue to function. Tasks that were carried out in the relationship must now be carried out by the survivor (Murray, Terry, Vance, Battistutta, & Connolly, 2000). Cerel, Jordan, and Duberstein (2008) stated that because suicide occurs within families, the focus on the aftermath of suicide within families and the impact on the spouse are important areas to investigate in order to determine exactly how to help survivors. Helping survivors to address practical, economic and legal issues, in addition to providing information and therapeutic intervention, is important (Dyregrov, 2002; Provini et al., 2000).

Purpose of the Study

Because of the frequency of suicide in the United States, the increased number of suicides within the U.S. military, and the impact of suicide on the family, the bereavement process among female spousal survivors of military suicides deserves further exploration. The purpose of this study was to explore bereavement in female spousal survivors of military suicides. Using LCMS, the study explored the relationship of bereavement and stigma, social support, primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, and coping skills among women whose military spouse had completed suicide.

Summary of the Study and Methodology

This study investigated the linear relationship between the dependent variable of bereavement and each of five independent variables—primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills, perceived social support and stigma—among women whose military spouses had completed suicide. The following hypotheses guided the study. Hypothesis 1 stated that there would be a relationship between bereavement and stigma; this positive relationship was significant. Hypothesis 2 stated that there would be a relationship between bereavement and social support; the relationship was not statistically significant. Hypothesis 3 stated that there would be a relationship between bereavement and primary appraisal; this positive relationship was significant. Hypothesis 4 stated that there would be a relationship between bereavement and secondary appraisal; this negative relationship was significant. Hypothesis 5 stated that there would be a relationship between bereavement and coping skills; this negative relationship was significant.

Using hierarchical regression analysis, the researcher examined the relationship of five independent variables—primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills, social support and stigma—to bereavement. The relationship was statistically significant. The model was a good fit and controlled for time since death (i.e., number of years since the person completed suicide). Therefore, for this sample, the five independent variables are components of a statistically significant model.

Participants and Recruitment

The participants in this study were women aged 18 and older who had lost a military spouse to suicide. Criteria for inclusion were that (a) the service member who had completed suicide had been either on active duty or of veteran status, (b) the survivor was female and 18 years of age or older, and (c) the survivor was considered a spouse. A spouse was defined as legally married to another person or living and cohabiting with another person in a marriage-like relationship, including a marriage-like relationship between persons of the same gender. Participants were chosen from seven national organizations serving veterans. The researcher recruited participants from these organizations by explaining the study and asking for volunteers. The director or assistant director of each organization distributed study information and materials through listservs and posted them on their Web sites. Once prospective participants received an e-mail, they decided whether they wanted to participate and whether they met the eligibility requirements. If the spouses decided to participate in the study, they would complete the survey through Survey Monkey.

Variables

Demographic variables included age, race/ethnicity, length of relationship with the deceased partner, the decedent’s military status (active or retired), the decedent’s length of service, and time elapsed since death. The survey also asked about the deceased’s rank, education level, surviving children and prior suicide attempts.

A self-report online survey was constructed using the following five instruments: the Core Bereavement Items (CBI; Holland, Futterman, Thompson, Moran, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2013), the Stigma of Suicide and Suicide Survivor Scale (STOSASS; Scocco, Castriotta, Toffol, & Preti, 2012), the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES; Chesney, Neilands, Chambers, Taylor, & Folkman, 2006), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet, 1988), and the Stress Appraisal Measure (SAM; Peacock & Wong, 1990). The SAM is one measure. However, the variables of primary stress appraisal and secondary stress appraisal within it were separated, and the questions within the SAM regarding primary stress appraisal were referred to as the primary stress appraisal measure (PSAM), and the remaining questions of the SAM were referred to as the secondary stress appraisal measure (SSAM). In addition to these assessments, participants would also answer 11 demographic questions and three open-ended questions. The survey was split into seven sections.

The first section had 11 demographic questions. The second section, comprised of the MSPSS, had 12 questions regarding social support of the participant and used a 7-point Likert scale. The third section, comprised of the CBI, had 26 questions regarding the participant’s ability to cope and used a 10-point Likert scale. The fourth section, comprised of the SAM, had 19 questions regarding participant’s stress appraisal measures and used a 4-point Likert scale. The fifth section, comprised of the STOSASS, had 17 questions regarding the participant’s perceived stigma and used a 4-point Likert scale. The sixth section, comprised of the CBI, had 17 questions regarding the participant’s bereavement process and used a 4-point Likert scale. The survey included the three following open-ended questions that were derived from the Grief Evaluation Measure (GEM) and reviewed by three licensed professional counselors working in the field of suicide bereavement: (1) What do you recall about how you responded to the death of your spouse at the time?; (2) What was the most painful part of the experience to you?; and (3) How has this experience affected your view of yourself or your view of your world? To analyze the qualitative responses, the researcher identified the most commonly recurring words or phrases used by participants for each question. Three experts in the field of grief and loss were consulted and confirmed the content and face validity of the survey.

Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), a statistical software package, generated all of the statistics for this research investigation. A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to determine whether there was a linear relationship between primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, social support, coping skills, stigma and bereavement for women whose military spouse had completed suicide. Following this analysis, a multiple regression was used to describe the relationships of the independent or predictor variables to the dependent or criterion variable (Lussier & Sonfield, 2004). Because LCMS states that it is possible to discern the order in which a person experiences each variable with regard to a particular event, the variables were entered into the regression using the following equation: Bereavement = {time since death} + {primary appraisal} + {secondary appraisal} + {coping skills} + {perceived social support} + {perceived stigma}.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics provided simple summaries of the demographic characteristics of the sample, as well as descriptors such as means and standard deviations for these characteristics. The sample was a well-educated, racially diverse group of women who had lost their military spouses to suicide. The majority of participants were non-Hispanic White females who had attended at least some college. Most were affiliated with the Army and had been married to the military member who had completed suicide. The majority of the partners had committed suicide while on active duty. The mean age of respondents was 33.48 years (SD = 5.20; SE = .373); their ages ranged from 23–50 years. The mean number of children aged 17 or under that were a product of the relationship with the service member was 1.12 (SD = .79; SE = .064); the range was 0–4 children. The mean number of prior suicide attempts by the service member (known/confirmed by the surviving female spouse) was 1.31 (SD = 1.06; SE = .096); the range was 0–4 prior suicide attempts.

Correlation Results

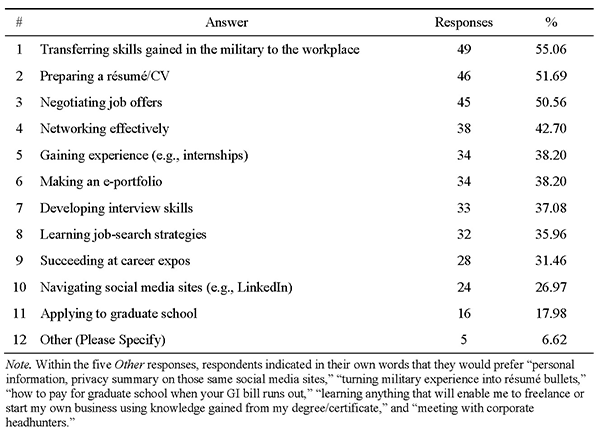

Using SPSS Student Version 22.0 software, a Pearson correlation coefficient was used to measure the relationship of bereavement, primary appraisals, secondary appraisals, coping skills, social support, and stigma among women whose military spouses had completed suicide. The correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of the relationship among variables. When conducting a correlational analysis of two co-occurring variables, the researcher can indicate whether change in one is accompanied by systematic change in the other. Examination of intercorrelations among study variables indicated statistically significant correlations between bereavement and each of four independent variables: primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skill, and stigma. The results for each correlation are presented separately and summarized below as well as in Table 1.

Control variable. There was a statistically significant relationship between time since death and bereavement for women whose military spouse had completed suicide, r(194) = .277, p < .01. The shorter the amount of time elapsed, the higher the bereavement scores.

Independent variables. Primary stress appraisal, r(193) = -.309, p < .01: There is a weak negative linear relationship between bereavement and primary stress appraisal. Secondary stress appraisal, r(193) = -.309, p < .01: There is a weak negative linear relationship between secondary stress appraisal and bereavement. Coping skills, r(193) = -.174, p = .015: There is a weak negative linear relationship between coping skills and bereavement. Social support, r(193) = -.039, p = .594: There is no linear relationship between perceived social support and bereavement. Stigma, r(193) = .252, p < .01: There is a weak positive linear relationship between perceived stigma and bereavement.

Table 1

Correlations for Independent, Dependent and Control Variables

CBI TSD PSAM SSAM MSPSS CSES

1. TSD .277*

2. PSAM -.309* -.167

3. SSAM -.309* -.151 .602*

4. MSPSS -.039 .032 .379* .172*

5. CSES -.174* -.167* .494* .473* .585*

6. STOSASS .252* .095 -.196* -.221* .022 -.253

Note: N = 194; CBI = Core Bereavement Items; TSD = Time Since Death (in months);

PSAM = Primary Stress Appraisal Measure; SSAM = Secondary Stress Appraisal Measure;

CSES = Coping Self-Efficacy Scale; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; STOSASS = Stigma of Suicide and Suicide Survivor Scale.

*Significant at p < .05.

Multiple Regression

Following the correlational analysis, a multiple regression was utilized. This analysis was appropriate to describe the relationships between the independent or predictor and dependent or criterion variables in an objective manner (Lussier & Sonfield, 2004). The design was appropriate because the purpose of the study was to explain the relationships between variables.

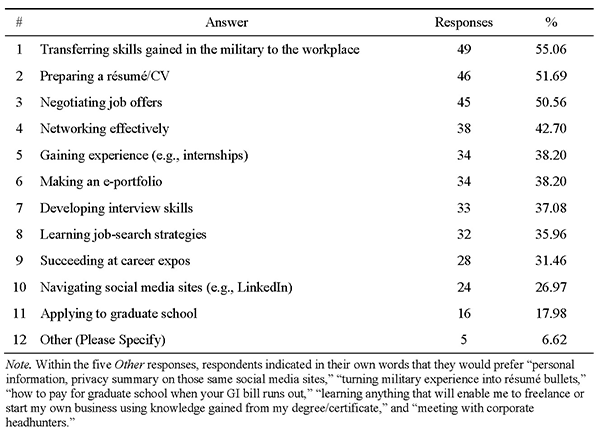

Model 1 (TSD onto bereavement) yielded R = .277, R2 = .077, F(1, 125), p < .001. The portion of the variance explained was 7%. Model 2 (TSD and primary appraisal) yielded R = .431, R2 = .186, F(2, 124), p < .001. The portion of variance explained was 18.6%. Model 3 (TSD, primary appraisal and secondary appraisal) yielded R = .454, R2 = .206, F(3, 123), p < .001. The portion of variance explained was 20.6%. Model 4 (time since death, primary appraisal, secondary appraisal and coping skills) yielded R = .455, R2 = .207, F(4, 122), p < .001. The portion of variance explained was 20.7%. Model 5 (time since death, primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills and social support) yielded R = .471, R2 = .221, F(5, 121), p < .001. The portion of variance explained was 22.1%. Model 6 (time since death, primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills, social support, and stigma) yielded R = .482, R2 = .232, F(6, 120), p < .001. The portion of variance explained was 23.2% (see Table 2).

Table 2

Hierarchical Multiple Regression

| Model |

R |

R2 |

t |

p |

B |

β |

R2 Change |

| Model 1TSD |

.277

|

.077

|

61.600

3.228

|

.000

.002

|

.049

|

.277

|

0

|

| Model 2TSDPSAM |

.431

|

.186

|

19.482

2.696

-4.074

|

.000

.008

.000

|

.039

-.406

|

.222

-.335

|

.109

|

| Model 3TSDPSAMSSAM |

.454

|

.206

|

19.646

2.618

-1.947

-1.782

|

.000

.010

.054

.077

|

.038

-.254

-.192

|

.214

-.209

-.191

|

.02

|

| Model 4TSDPSAMSSAMCSES |

.455

|

.207

|

16.971

2.622

-1.952

-1.788

.266

|

.000

.010

.053

.076

.791

|

.038

-.262

-.199

.004

|

.216

-.216

-.198

.025

|

.001

|

| Model 5TSDPSAMSSAMCSESMSPSS |

.471

|

.221

|

12.989

2.307

-2.359

-1.111

-0.710

1.505

|

.000

.023

.020

.269

.479

.135

|

.034

-.335

-.132

-.012

.091

|

.192

-.276

-.132

-.083

.167

|

.015

|

| Model 6 TSDPSAMSSAMCSESMSPSSSTOSASS |

.482

|

.232

|

9.026

2.329

-2.187

-1.105

-0.320

1.107

1.280

|

.000

.022

.031

.271

.750

.271

.203

|

.034

-.312

-.131

-.006

.069

.086

|

.194

-.257

-.131

-.039

.128

.112

|

.010

|

Note: TSD = Time Since Death (in months); PSAM = Primary Stress Appraisal Measure; SSAM = Secondary Stress Appraisal Measure; CSES = Coping Self-Efficacy Scale; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; STOSASS = Stigma of Suicide and Suicide Survivor Scale.

Qualitative Component

There is a growing interest in integrating qualitative data across quantitative studies to discover patterns and common threads within a specific topic or issue (Erwin, Brotherson, & Summers, 2011). The main aim of the qualitative questions within the survey is to gain insight into the participants’ world and capture their unique experiences (e.g., naturally occurring events and/or social or human problems) and their interpretations of these experiences (Jones, 1995; Sarantakos, 1993).

A total of 55 (28.4%) participants responded to the question, “What do you recall about how you responded to the death of your spouse at the time?” Of these, 24 stated recalling “sadness” as most frequent. Fifteen participants indicated disbelief, shock, feelings of helplessness or feelings of fear. Other participants’ responses included “trying not to think about what had happened,” crying, sobbing, physical symptoms, physical pain, collapsing, fainting, being unable to forget what happened, and being unable to recall or process the event. A total of 68 (35.1%) participants responded to the question, “What was the most painful part of the experience to you?” Of these, 50 reported physical and emotional numbness and only partial recollection of learning about the death (e.g., who told them, where they were when notified, immediate responses). These participants indicated that they could recall parts of the experience but struggled with identifying feelings or emotions directly following the event. Other responses included being hospitalized, contemplating suicide, refraining from eating, and feeling that their future had been lost. Although four reported contemplating suicide following the death of their spouse, no participants reported attempting suicide at any point. A total of 36 (18.6%) participants responded to the question, “How has this experience affected your view of yourself or your view of your world?” Of these, 15 participants indicated that they no longer feared death, while seven reported having a negative reaction to relationships. Eleven participants reported that they perceived stress as more threatening than before the suicide of their spouse and were unaware of the triggers that brought on stress during the bereavement process. Ten participants indicated that their view of love had changed since the loss of their spouse. Nine participants wrote about making an effort to enjoy life after the suicide of their spouse.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationships between bereavement and primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills, perceived social support and stigma among women whose military spouses had completed suicide. There are several study findings that deserve further exploration.

First, there was a statistically significant positive relationship between stigma and bereavement, suggesting that as female survivors perceive increased stigma regarding the suicide of their spouse, they present more symptoms of bereavement. Knieper (1999) suggested that bereavement following suicide is not the same as that following natural death. He reported that stigma and avoidance continue to be central issues for suicide survivors. Psychological projection of feelings of rejection and the actual social response to the survivor interact in a complicated manner. Worden (2009) also noted a difference between suicide bereavement and other forms of bereavement, suggesting that suicide is often associated with stigma and a sense of shame. Such shame can result in the complete isolation of the bereaved during the period immediately following the suicide event. Eaton and associates (2008) examined survivors’ barriers to seeking mental health treatment after the suicide of their partners and found that spouses were 70% less likely to seek treatment following a suicide, as compared to a natural death, and that stigma was a recurrent theme in the qualitative analysis. However, Eaton et al.’s study did not directly examine the impact of stigma on bereavement. It did show that stigma is an important variable that needs to be investigated further. The present study showed similar results to Eaton et al.’s (2008) research.

The qualitative comments recorded in the open-ended question section of the survey supported the study findings. For example, one participant responded, “I blamed myself for not doing more, not being there enough, or not being there when the death happened.” Another participant noted, “Suicide is one of the most difficult and painful ways to lose someone we love, because we are left with so many unanswerable questions.” One participant expressed the following:

[I felt] anger at family members for not assisting me with my husband and anger at physicians that treated my husband and were not able to see the warning signs or provide assistance in caring for them properly. I was then left with the scars after the death and had to explain to people what happened. I felt I got blamed and it was not my fault.

Several participants expressed “numbness and isolation.” Responding to stigma, people with mental health problems often internalize public attitudes and become embarrassed or ashamed. These feelings can lead them to conceal symptoms and fail to seek treatment (President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003). These survey responses assist in understanding the impact of stigma upon the military spouse survivors and imply that unanswered questions, as well as guilt, are important factors to explore in the grief process following a suicide.

Second, a statistically significant relationship between primary appraisal and bereavement was reported, suggesting that survivors who perceive the death of a spouse to be stressful are more likely to experience bereavement. This result is supported by the bereavement literature (Cvinar, 2005; Jordan, 2001; McIntosh, 1993). Lazarus (2005) argued that primary appraisal shows that it is not the situation, but the way a person interprets the situation, that affects the person’s experience. The way a person appraises a situation can impact the way the person reacts to it. Primary appraisal is an important step in processing the stress of bereavement, since grieving is such an individualized experience.

The qualitative comments recorded in the open-ended question portion of the survey supported the statistical relationship between primary appraisal and bereavement. For example, one participant indicated that her worldview had changed when she responded, “My world has become gray; I have made myself closed. I live in a rain cloud and now know that good people do bad things that change lives.” The participant had changed her worldview such that her world became a smaller, more restricted place. Another stated, “This death, this loss, makes small things seem insignificant. Material things are insignificant. Relationships with people are more important. I don’t have a fear of dying and in fact, feel like I will die at a young age.” This concept of primary appraisal is based on the idea that emotional processes are dependent on a person’s expectancies about the significance and outcome of a specific event. The same event within the same community (in this case, suicide within the military) can elicit responses of different quality, intensity and duration due to individuality in experiences and personality (Krohne, Pieper, Knoll, & Breimer, 2002). The different kinds of stress identified by the primary appraisal may be embedded in specific types of emotional reactions, thus illustrating the close conjunction of the fields of stress and emotion (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Third, a statistically significant negative relationship was reported between secondary appraisal and bereavement, suggesting that survivors who make a negative appraisal of their ability to control the outcomes of their spouse’s death are more likely to experience bereavement. In the future, when examining outcomes of interventions that impact coping, beliefs about a person’s ability to perform specific behaviors related to coping would need to be highlighted. This concept is known as specific coping behaviors and is also pertinent to stress, coping theory and secondary appraisal (Chesney et al., 2006). Part of secondary appraisal is the judgment that an outcome is controllable through coping; another part addresses the question of whether or not the individual believes he or she can carry out the requisite coping strategy (Chesney et al., 2006; DiClemente, 1986; Hofstetter, Sallis, & Hovell, 1990).

The qualitative comments recorded in the open-ended section of the survey supported this finding. For example, one participant indicated her appraisal of the situation by stating, “Everyone must learn to face the misfortune, because life on the road will not be smooth.” Another stated that “time can dilute all and I must face life and accept my reality;” yet another wrote, “I want to work on longer range goals to give myself some structure and direction to my life and not focus on my loss. I am only interested in rebuilding my life.” However, other participants stated that it was harder to assess the loss and to move forward after the suicide. One participant stated the following:

I often find myself complaining to God about what seems senseless or unjust and unfair. I find myself bogged down in fear and even anger at myself or the person who died and “left” me. I do not accept what happen[ed] to me and my children.

Some participants reported not knowing what to do. An example of this feeling is the statement, “I perceive stress as threatening. I feel totally helpless.” Perceived self-efficacy, defined as a belief about one’s ability to perform a specific behavior, is a salient component of this theory. It highlights the importance of personal efficacy in determining the acquisition of knowledge on which skills are founded (Bandura, 1997; Chesney et al., 2006).

Fourth, a statistically significant negative relationship between coping skills and bereavement was reported, suggesting that survivors who believe they have a low ability to cope with their spouses’ death are more likely to experience bereavement. Although it is important for survivors to become familiar with the stress appraisal process, the way they assign meaning to their spouse’s death and their past experience with death also are important in their primary appraisal to the overall coping effort. One model of this process is the transactional model of coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). This model of coping implies that a person’s appraisal of his or her interaction with a difficult event naturally evokes a coping response for dealing with the situation. Experiencing a suicide or living in a social environment that hinders, stigmatizes or isolates a person who has experienced a suicidal death may cause demands to exceed his or her resources for dealing with certain situations. Few studies have examined the natural coping efforts used by suicide survivors, or have identified specific problems and needs that survivors experience following the suicide of a significant other (McMenamy et al., 2008). Interventions with suicide survivors have limited effectiveness (Jordan & McMenamy, 2004). Provini et al. (2000) presented four categories of concerns for suicide survivors: concerns related to (a) family relationships, (b) psychiatric symptoms, (c) bereavement and (d) stress. Family-related problems were the most frequently mentioned type of concerns (Provini et al., 2000). Examples of family relationship concerns included inability to maintain parenting roles, inability to maintain family routines, existence of different coping styles within the family, and inability to provide appropriate emotional support to family members.

Qualitative comments recorded in the open-ended section of the survey supported this study finding. For example, one participant stated, “I often feel distracted, forgetful, irritable, disoriented, or confused. I try to remember how I got over a death in the past, sometimes it helps and sometimes it does not.” Another participant stated, “I know I need to start to form new relationships or attachments in my life but my mind [is] telling me ‘there must be some mistake,’ or ‘this can’t be true.’ ” Regarding bereavement, one participant wrote, “Grief is perhaps the most painful companion to death.” Addressing coping, one participant stated, “I must also adjust to working or returning to work after the death. I know things can’t go back to the way they were before, very difficult and painful to deal with and I better adjust to life.” These statements support the need to further explore the relationship between one’s ability to cope with the suicide of a spouse and one’s ability to experience and acknowledge feelings and move forward with everyday life activities (e.g., employment, childcare, financial obligations). Ability to cope impacts a person’s bereavement process; the ways and ability to cope vary with the individual. Stigma and amount of perceived social support have been correlated with ability to cope (Bandura, 1997). It is important to understand the individual impacts that stigma, social support, primary appraisal, secondary appraisal and coping have on bereavement. However, it is equally important to examine the relationships of these variables within the context of a model in order to establish future interventions for bereavement within the context of a suicide.

Fifth, results indicated that the model is statistically significant in predicting bereavement outcomes and provides considerable support for using the Lazarus model as a means of understanding the relationship between stress and bereavement when placed into the equation in a particular order: CBI = TSD + PSAM + SSAM + CSES + MSPSS + STOSASS.

This study suggests that the proposed model, using LCMS and assessment of stress, identifies the constructs associated with bereavement among women whose military spouses completed suicide. Future research could further explore the assessment of primary and secondary appraisal processes, coping, stigma, and social support enhancement programs and interventions to improve the bereavement process for military spouses. When survivors can identify and address their needs, the bereavement process following a suicide can begin (Christensen & Yaffe, 2012).

Limitations

First, the majority of the sample (54.1%) were non-Hispanic White, or Euro-American. Second, there is limited representation across military branches. Third, the study collected data from a self-administered electronic survey. Fourth, although the social support measure (i.e., MSPSS) has good reliability and measures social support as a general feeling of belonging to a social network that one can turn to for advice and assistance in times of need (Uchino, 2006), it does not delineate various types of social support. Finally, most of the sample consisted of women whose spouses had completed suicide while on active duty. Active duty members typically live on base and are well connected to the military community. When the military spouse dies, these supports are often no longer available, and the stigma of a suicide could strongly affect these women.

Recommendations for Future Studies

There are several practice implications from this study. The statistically significant correlations between bereavement and four other variables (primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping skills and stigma), as well as the significance of the LCMS construct of primary appraisal within Model 6, indicate that LCMS holds promise for understanding symptoms of bereavement in females following the suicide of a military spouse. Primary appraisal, the most significant variable within this study, could be highlighted within bereavement research on women whose military spouses have completed suicide. When conceptualizing the responses of these women, counselors and clinicians could use LCMS, examining the three components of primary appraisal (goal relevance, goal congruence and ego involvement) and exploring the ways these components present during the client’s bereavement process. The approach would focus on the role of maladaptive cognitions during times of stress (Sudak, 2009).

The reluctance of the military community to seek mental health support contributes to an inability to move through the bereavement process in a healthy way. Within the military community, it can be quite difficult to deal with the ambiguity of bereavement that is typically associated with emotional vulnerability (Lamorie, 2011). However, the current study suggests that four constructs—primary appraisal, secondary appraisal, coping and stigma—are significant when addressing the issues of bereavement in females who have lost a military spouse to suicide. Using LCMS to address cognitions, counselors might be able to assist a population whose members have been reluctant to seek mental health services in the past. Because the components of LCMS are correlated with bereavement, clinicians could use LCMS and cognitive stress research, which together seem to be a promising direction, when assisting women who have lost a military spouse to suicide.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The author reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Agerbo, E. (2005). Midlife suicide risk, partner’s psychiatric illness, spouse and child bereavement by suicide or other modes of death: A gender specific study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 407–412. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.024950

Amaya-Jackson, L., Davidson, J. R., Hughes, D. C., Swartz, M., Reynolds, V., George, L. K., & Blazer, D. G. (1999). Functional impairment and utilization of services associated with posttraumatic stress in the community. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12, 709–724. doi:10.1023/A:1024781504756

Andriessen, K. (2009). Can postvention be prevention? Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 30, 43–47. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.30.1.43

Audoin-Rouzeau, A., & Becker, S. (2002). 14–18: Understanding the great war. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Worth.

Bleed, J. (2007, February 19). Howell’s life insurance payout not a sure bet. Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Retrieved from http://www.arkansasonline.com/

Burton, T., Farley, D., & Rhea, A. (2009). Stress-induced somatization in spouses of deployed and nondeployed servicemen. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 21, 332–339. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00411.x

Callahan, J. (2000). Predictors and correlates of bereavement in suicide support group participants. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 30, 104–124. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb01070.x

Cerel, J., Jordan, J. R., & Duberstein, P. R. (2008). The impact of suicide on the family. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 29, 38–44. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.29.1.38

Chesney, M. A., Neilands, T. B., Chambers, D. B., Taylor, J. M., & Folkman, S. (2006). A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 421–337. doi:10.1348/135910705X53155

Christensen, B. N., & Yaffe, J. (2012). Factors affecting mental health service utilization among deployed military personnel. Military Medicine, 177, 278–283.

Congressional Quarterly. (2010). Rising military suicide: The pace is faster than combat death in Iraq and Afghanistan. Retrieved from http://www.infiniteunknown.net/2010/01/01/rising-us-military-suicides-the-pace-is-faster-than-combat-deaths-in-iraq-or-afghanistan/

Cvinar, J. C. (2005). Do suicide survivors suffer social stigma: a review of the literature. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 41, 14–21. doi:10.1111/j.0031-5990.2005.00004.x

DiClemente, C. C. (1986). Self-efficacy and the addictive behaviors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4, 302–315. doi:10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.302

Doka, K. J. (2005). Ethics, end-of-life decisions and grief. Mortality, 10, 83–90. doi:10.1080/13576270500031105

Dyregrov, K. (2002). Assistance from local authorities versus survivors’ needs for support after suicide. Death Studies, 26, 647–668. doi:10.1080/07481180290088356

Eaton, K. M., Hoge, C. W., Messer, S. C., Whitt, A. A., Cabrera, O. A., McGurk, D., . . . Castro, C. A. (2008). Prevalence of mental health problems, treatment need, and barriers to care among primary care-seeking spouses of military service members involved in Iraq and Afghanistan deployments. Military Medicine, 173, 1051–1056.

Eberhardt, B., Dilger, S., Musial, F., Wedding, U., Weiss, T., & Miltner, W. H. (2006). Short-term monitoring of cognitive functions before and during the first course of treatment. Journal of Cancer Research & Clinical Oncology, 132, 234–240. doi:10.1007/s00432-005-0070-8

Erwin, E. J., Brotherson, M. J., & Summers, J. A. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 33, 186–200. doi:10.1177/1053815111425493

Groomes, D. A. G., & Leahy, M. J. (2002). The relationships among the stress appraisal process, coping disposition, and level of acceptance of disability. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 46, 15–24.

Harwood, D., Hawton, K., Hope, T., & Jacoby, R. (2002). The grief experiences and needs of bereaved relatives and friends of older people dying through suicide: A descriptive and case-control study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 72, 185–194. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00462-1

Hofstetter, C. R., Sallis, J. F., & Hovell, M. F. (1990). Some health dimensions of self-efficacy: Analysis of theoretical specificity. Social Science & Medicine, 31, 1051–1056.

Holland, J. M., Futterman, A., Thompson, L. W., Moran, C., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2013). Difficulties accepting the loss of a spouse: A precursor for intensified grieving among widowed older adults. Death Studies, 37, 126–144. doi:10.1080/07481187.2011.617489

Jones, R. (1995). Why do qualitative research? British Medical Journal, 311(6996), 2–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.6996.2

Jordan, J. R. (2001). Is suicide bereavement different? A reassessment of the literature. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31, 91–102. doi:10.1521/suli.31.1.91.21310

Jordan, J. R., & McIntosh, J. L. (2011). Grief after suicide: Understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jordan, J. R., & McMenamy, J. (2004). Interventions for suicide survivors: A review of the literature. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34, 337–349. doi:10.1521/suli.34.4.337.53742

Kang, H. K., Natelson, B. H., Mahan, C. M., Lee, K. Y., & Murphy, F. M. (2003). Post-Traumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome-like illness among Gulf War veterans: A population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 141–148. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf187

Katzenell, U., Ash, N., Tapia, A. L., Campino, G. A., & Glassberg, E. (2012). Analysis of the causes of death of casualties in field military setting. Military Medical Journal, 177, 1065–1068.

Knieper, A. J. (1999). The suicide survivor’s grief and recovery. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 353–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1999.tb00530.x

Krohne, H. W., Pieper, M., Knoll, N., & Breimer, N. (2002). The cognitive regulation of emotions: The role of success versus failure experience and coping dispositions. Cognition & Emotion, 16, 217–243. doi:10.1080/02699930143000301

Lamorie, J. (2011). Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom: Exploring wartime death and bereavement. Social Work in Health Care, 50, 543–563. doi:10.1080/00981389.2010.532050

Lazarus, A. A. (2005). Is there still a need for psychotherapy integration? Current Psychology, 24, 149–152. doi:10.1007/s12144-005-1018-5

Lazarus, A. A. (1996). Behavior therapy & beyond. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Lindemann, E., & Greer, I. M. (1953). A study of grief: Emotional responses to suicide. Pastoral Psychology, 4, 9–13.

Lussier, R. N., & Sonfield, M. C. (2004). Family business management activities, styles and characteristics: A correlational study. Mid-American Journal of Business, 19, 47–53.

Martin, J., Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M., Lou, K., & Tucciarone, P. (2009). A comparative review of U.S. military and civilian suicide behavior: Implications for OEF/OIF suicide prevention efforts. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 31, 101–118.

McIntosh, J. L. (1993). Control group studies of suicide survivors: A review and critique. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 23,146–161. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1993.tb00379.x

McMenamy, J. M., Jordan, J. R., & Mitchell, A. M. (2008). What do suicide survivors tell us they need? Results of a pilot study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38, 375–389. doi:10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.375

Miers, D., Abbott, D., & Springer, P. R. (2012). A phenomenological study of family needs following the suicide of a teenager. Death Studies, 36, 118–133. doi:10.1080/07481187.2011.553341

Miles, D. (2010). VA strives to prevent veteran suicides. Retrieved from http://www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=58879

Minois, G. (1999). History of suicide: Voluntary death in western culture (L. G. Cochrane, Trans.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Murray, J. A., Terry, D. J., Vance, J. C., Battistutta, D., & Connolly, Y. (2000). Effects of a program of intervention on parental distress following infant death. Death Studies, 24, 275–305. doi:10.1080/074811800200469

National Institute of Mental Health. (2010). Statistics. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (2013). Suicide prevention. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/suicide-prevention/index.shtml

Neimeyer, R. A., & Jordan, J. R. (2002). Disenfranchisement as empathic failure: Grief therapy and the co-construction of meaning. In K. J. Doka (Ed.), Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice (pp. 95–117). Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Ness, D. E., & Pfeffer, C. R. (1990). Sequelae of bereavement resulting from suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 279–285.

Parrish, M., & Tunkle, J. (2005). Clinical challenges following an adolescent’s death by suicide: Bereavement issues faced by family, friends, schools, and clinicians. Clinical Social Work Journal, 33, 81–102. doi:10.1007/s10615-005-2621-5

Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1990). The stress appraisal measure (SAM): A multidimensional approach to cognitive appraisal. Stress Medicine, 6, 227–236. doi:10.1002/smi.2460060308

President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). New freedom commission on mental health report. Retrieved from http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/mentalhealthcommission/reports/FinalReport/downloads/FinalReport.pdf

Provini, C., Everett, J. R., & Pfeffer, C. R. (2000). Adults mourning suicide: Self-Reported concerns about bereavement, needs for assistance, and help-seeking behavior. Death Studies, 24, 1–19. doi:10.1080/074811800200667

Sarantakos, S. (1993). Social research. Basingstoke, England: Macmillan.

Scocco, P., Castriotta, C., Toffol, E., & Preti, A. (2012). Stigma of Suicide Attempt (STOSA) scale and Stigma of Suicide and Suicide Survivor (STOSASS) scale: Two new assessment tools. Psychiatry Research, 200, 872–878. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.033

Siebrecht, C. (2011). Imagining the absent dead: Rituals of bereavement and the place of the war dead in German women’s art during the First World War. German History, 29, 202–223.

Steel, J. L., Dunlavy, A. C., Stillman, J., & Pape, H. C. (2011). Measuring depression and PTSD after trauma: Common scales and checklists. Injury, 42, 288–300. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2010.11.045

Sudak, D. (2009). Training in cognitive behavioral therapy in psychiatry residency: An overview for educators. Behavior Modification, 33, 124–137. doi:10.1177/1059601108322626

Sveen, C.-A., & Walby, F. A. (2008). Suicide survivors’ mental health and grief reactions: A systematic review of controlled studies. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38, 13–29. doi:10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.13

Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavior Medicine, 29, 377–387. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

Worden, J. W. (1991). Grief counseling & grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

Worden, J. W. (2009). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (4th ed.) New York, NY: Springer.

Zamorski, M. A. (2011). Suicide prevention in military organizations. International Review of Psychiatry, 23, 173–180. doi:10.3109/09540261.2011.562186

Zhang, J., & Jia, C.-X. (2009). Attitudes toward suicide: The effect of suicide death in the family. Omega, 60, 365–382. doi:10.2190/OM.60.4.d307.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Lindsey Mitchell, NCC, is the recipient of the 2015 Outstanding Dissertation Award for The Professional Counselor and a licensed counselor in both Texas and Washington, D.C. Correspondence may be addressed to Lindsey Mitchell at lmitch26@gwmail.gwu.edu.

Apr 7, 2014 | Article, Volume 4 - Issue 2

Elizabeth A. Prosek, Jessica M. Holm

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and TRICARE have approved professional counselors to work within the military system. Counselors need to be aware of potential ethical conflicts between counselor ethical guidelines and military protocol. This article examines confidentiality, multiple relationships and cultural competency, as well as ethical models to navigate potential dilemmas with veterans. The first model describes three approaches for navigating the ethical quandaries: military manual approach, stealth approach, and best interest approach. The second model describes 10-stages to follow when navigating ethical dilemmas. A case study is used for analysis.

Keywords: military, ethics, veterans, counselors, competency, confidentiality

The American Community Survey (ACS; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011) estimated that 21.5 million veterans live in the United States. A reported 1.6 million veterans served in the Gulf War operations that began post-9/11 in 2001 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Gulf War post-9/11 veterans served mainly in Iraq and Afghanistan, in operations including but not limited to Operations Enduring Freedom (OEF), Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and New Dawn (OND) (M. E. Otey, personal communication, October 23, 2012). Holder (2007) estimated that veterans represent 10% of the total U.S. population ages 17 years and older. Pre-9/11 data suggested that 11% of military service members utilized mental health services in the year 2000 (Garvey Wilson, Messer, & Hoge, 2009). In 2003, post-9/11 comparative data reported that 19% of veterans deployed to Iraq accessed mental health services within one year of return (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006). Recognizing the increased need for mental health assessment, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) mandated the Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) for all returning service members (Hoge et al., 2006). The PDHA is a brief three-page self-report screening of symptoms to include post-traumatic stress, depression, suicidal ideation and aggression (U.S. DOD, n.d.). The assessment also indicates service member self-report interest in accessing mental health services.

Military service members access mental health services for a variety of reasons. In a qualitative study of veterans who accessed services at a Veterans Affairs (VA) mental health clinic, 48% of participants reported seeking treatment because of relational problems, and 44% sought treatment because of anger and/or irritable mood (Snell & Tusaie, 2008). Veterans may also present with mental health symptoms related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and suicidal ideation (Hoge et al., 2006). Depression is considered a common risk factor of suicide among the general population, and veterans are additionally at risk due to combat exposure (Martin, Ghahramanlou-Holloway, Lou, & Tucciarone, 2009). The DOD (2012) confirmed that 165 active-duty Army service members committed suicide in 2011. Furthermore, researchers asserted that suicide caused service member deaths more often than combat (O’Gorman, 2012). Hoge et al. (2004) reported that veterans were most likely to access mental health services 3–4 months post-deployment. Unfortunately, researchers suggested that service members were hesitant to access mental health treatment, citing the stigma of labels (Kim, Britt, Klocko, Riviere, & Adler, 2011). Studies indicated that mental health service needs are underestimated among the military population and are therefore a potential burden to an understaffed helping profession (Garvey Wilson et al., 2009; Hoge et al., 2006). In May of 2013, the DOD and VA created 1,400 new positions for mental health providers to serve military personnel (DOD, 2013). Moreover, as of March 2013, the DOD-sponsored veterans crisis line reported more than 800,000 calls (DOD, 2013). It is evident that the veteran population remains at risk for problems related to optimal mental health functioning and therefore requires assistance from trained helping professionals.

Historically, the DOD employed social workers and psychologists almost exclusively to provide mental health services in the military setting. Recently, the DOD and VA expanded services and created more positions for mental health clinicians (U.S. VA, 2012). Because licensed professional counselors (LPCs) are now employable by VA service providers (e.g., VA hospitals) and approved TRICARE providers (Barstow & Terrazas, 2012), it is imperative to develop an understanding of the military system, especially of the potential conflict that may exist between military protocol and counselor ethical guidelines. The military health system requires mental health professionals to be appropriately credentialed (e.g., licensed), and credentialing results in the mandatory adherence to a set of professional ethical standards (Johnson, Grasso, & Maslowski, 2010). However, there may be times when professional ethical standards do not align with military regulations. Thus, an analysis of the counselor ethical codes relevant to the military population is presented. At times, discrepancies between military protocol and counselor ethical codes may emerge; therefore, recommendations for navigating such ethical dilemmas are provided. A case study and analysis from the perspective of two ethical decision-making models are presented.

Ethical Considerations for Counselors

The mission of the American Counseling Association (ACA) Code of Ethics (2005) is to establish a set of standards for professional counselors, which ensure that the counseling profession continues to enhance the profession and quality of care with regard to diversity. As professional counselors become employed by various VA mental health agencies or apply for TRICARE provider status, it is important to identify specific ethical codes relevant to the military population. Therefore, three categories of ethical considerations pertinent to working with military service members are presented: confidentiality, multiple relationships, and cultural competence.

Confidentiality

The ACA Code of Ethics (2005) suggests that informed consent (A.2.a., p. 4) be a written and verbal discussion of rights and responsibilities in the counseling relationship. This document includes the client right for confidentiality (B.1.c., p. 7) with explanation of limitations (B.1.d., p. 7). The limitations, or exceptions, to confidentiality include harm to self, harm to others and illegal substance use. In the military setting, counselors may need to consider other exceptions to confidentiality including domestic violence (Reger, Etherage, Reger, & Gahm, 2008), harassment, criminal activity and areas associated with fitness for duty (Kennedy & Johnson, 2009). Also, military administrators may require mandated reporting when service members are referred for substance abuse treatment (Reger et al., 2008). When these conditions arise in counseling, the military may require reporting beyond the standard ethical protocol to which counselors are accustomed.

Counselors working in the VA mental health system or within TRICARE may need to be flexible with informed consent documents, depending on the purpose of services sought. Historically, veterans represented those who returned from deployment and stayed home. Currently, military members may serve multiple tours of combat duty; therefore, the definition of veterans now includes active-duty personnel. This modern definition of veteran speaks to issues of fitness for duty, where the goal is to return service members ready for combat. Informed consent documents may need to outline disclosures to commanding officers. For example, if a service member is in need of a Command-Directed Evaluation (CDE), then the commander is authorized to see the results of the assessment (Reger et al., 2008). Fitness for duty is also relevant when service members are mandated to the Soldier Readiness Program (SRP) to determine their readiness for deployment. In these situations, counselors need to clearly explain the exception to confidentiality before conducting the assessment. Depending on the type of agency and its connection to the DOD, active-duty veterans’ health records may be considered government property, not the property of the service provider (McCauley, Hacker Hughes, & Liebling-Kalifani, 2008). It is imperative that counselors are educated on the protocols of the setting or assessments, because “providing feedback to a commander in the wrong situation can be an ethical violation that is reviewable by a state licensing authority” (Reger et al., 2008, p. 30). Thus, in order to protect the client and the counselor, limitations to confidentiality within the military setting must be accurately observed at all times. Knowledge of appropriate communication between the counselor and military system also speaks to the issue of multiple relationships.

Multiple Relationships

Kennedy and Johnson (2009) suggested creating collaborative relationships with interdisciplinary teams in a military setting in order to create a network of consultants (e.g., lawyers, psychologists, psychiatrists), which is consistent with ACA ethical code D.1.b to develop interdisciplinary relationships (2005, p. 11). However, when interdisciplinary teams are formed, there are ACA (2005) ethical guidelines that must be considered. These guidelines state that interdisciplinary teams must focus on collaboratively helping the client by utilizing the knowledge of each professional on the team (D.1.c., p. 11). Counselors also must make the other members of the team aware of the constraints of confidentiality that may arise (D.1.d., p. 11). In addition, counselors should adhere to employer policies (D.1.g., p. 11), openly communicating with VA superiors to navigate potential discrepancies between employers’ expectations and counselors’ roles in best helping the client.

In the military environment, case transfers are common because of the high incidence of client relocation, which increases the need for the interdisciplinary teams to develop time-sensitive treatment plans (Reger et al., 2008). Therefore, treatment plans not only need to follow the guidelines of A.1.c., in which counseling plans “offer reasonable promise of success and are consistent with abilities and circumstances of clients” (ACA, 2005, p. 4), but they also need to reflect brief interventions or treatment modalities that can be easily transferred to a new professional. Mental health professionals may work together to best utilize their specialized services in order to meet the needs of military service members in a minimal time allowance.

For those working with military service members, consideration of multiple relationships in terms of client caseload also is important. Service members who work together within the same unit may seek mental health services at the same agency. Members of a military unit may be considered a support network which, according to ethical code A.1.d., may be used as a resource for the client and/or counselor (ACA, 2005, p. 4). However, learning about a military unit as a network from multiple member perspectives may also create a dilemma. Service members within a unit may be tempted to probe the counselor for information about other service members, or tempt the counselor to become involved in the unit dynamic. McCauley et al. (2008) recommended that mental health professionals avoid mediating conflicts between service members in order to remain neutral in the agency setting.

However, there are times when the unit cohesion may be used to support the therapeutic relationship. Basic military training for service members emphasizes the value of teamwork and the collective mind as essential to success (Strom et al., 2012). It is important for counselors to approach military service member clients from this perspective, not from a traditional Western individualistic lens. Mental health professionals also are warned not to be discouraged if rapport is more challenging to build than expected. Hall (2011) suggested that the importance of secrecy in the military setting might make it more difficult for service members to readily share in the therapeutic relationship. Researchers noted that military service members easily built rapport with each other in a group therapy session, often leaving out the civilian group leader (Strom et al., 2012). It might behoove counselors to build upon the framework of collectivism in order to earn the trust of members of the military population. Navigating the dynamic of a unit or the population of service members accessing care at the agency may be a challenge; however, counselors are able to alleviate this challenge with increased knowledge of the military culture in general.

Cultural Competence

The military population represents a group of people with a unique “language, a code of manners, norms of behavior, belief systems, dress, and rituals” and therefore can be considered a cultural group (Reger et al., 2008, p. 22). Reger et al. (2008) suggested that many clinical psychologists learned about military culture as active service members themselves. While there may be many veterans currently working as professional counselors, civilian counselors also serve the mental health needs of the military population; and as civilians, they require further training. The ACA Code of Ethics (2005) suggests that counselors communicate with their clients in ways that are culturally appropriate to ensure understanding (A.2.c., p. 4). This can be achieved by prolonged exposure to military culture or by seeking supervision from a professional involved with the military mental health system (Reger et al., 2008). Strom et al. (2012) outlined examples of military-specific cultural components for professionals to learn: importance of rank, unique terminology and value of teamwork. It behooves counselors intending to work with the military population to learn terminology in order to understand service members. For example, R&R refers to vacation leave and MOS or rate refers to a job category (Strom et al., 2012).

Personal values may cause dilemmas for a mental health professional working within the VA system. This can be especially true during times of war. Stone (2008) suggested that treating veterans of past wars may be easier than working with military service members during current combat because politics may be intensified. A counselor who does not support the current wartime mission may be conflicted when clients are mandated to return to active-duty assignments (Stone, 2008). The ACA Code of Ethics (2005) addresses the impact of counselors’ personal values (A.4.b., pp. 4–5) on the therapeutic relationship. It is recommended that counselors be aware of their own values and beliefs and respect the diversity of their clients. Counselors need to find a way to value the contributions of their client when personal or political opinion conflicts with the DOD’s plans or efforts overseas. If one wants to be successful with this population, Johnson (2008) suggested the foundational importance of accepting the military mission. If this is in direct conflict with the counselor’s values, it may be recommended for the counselor to consider the client’s value of the mission.

The ACA ethical code stresses the importance of mental health professionals practicing within the boundaries of their competence and continuing to broaden their knowledge to work with diverse clients (ACA, 2005, C.2.a., p. 9). Counselors should only develop new specialty areas after appropriate training and supervised experience (ACA, 2005, C.2.b., p. 9). Working within the VA mental health system, mental health professionals may be asked to provide a service in which they are not competent (Kennedy & Johnson, 2009). Such a request may occur more frequently here than in other settings, due to the high demand of mental health services and low availability of trained professionals (Garvey Wilson et al., 2009; Hoge et al., 2006). Counselors must determine if their experience and training can be generalized to working with military service members (Kennedy & Johnson, 2009), and may be their own best advocate for receiving appropriate training.

Awareness of when and how military service members access mental health services also might be important to consider. Reger et al. (2008) reported that military personnel were more likely to access services before and after a deployment. Researchers specified a higher prevalence rate of access 3–4 months after a deployment (Hoge et al., 2004). The relationship of time between deployment and help-seeking behaviors suggests that counselors should be prepared for issues related to trauma. For women, combat-related trauma is compounded with increased rates of reported military sexual trauma (Kelly et al., 2008). Counselors would benefit from additional trainings in trauma intervention strategies. The VA and related military organizations offer many resources online to educate professionals working with military members with identified trauma symptoms (U.S. VA., n.d.).

Advocating for appropriate training in areas of incompetence is the responsibility of the professional, who should pursue such training in order to best meet the needs of the military population. It is best practice for mental health professionals to be engaged in ongoing trainings to ensure utilization of the latest protocols and treatment modalities (McCauley et al., 2008). Trainings may need to extend beyond general military culture, because each branch of service (e.g., Army, Marines, Navy) could be considered a cultural subgroup with unique language and standards. For example, service members in the Army are soldiers, whereas members of the Navy are sailors (Strom et al., 2012).

This article has outlined many ACA (2005) ethical guidelines pertinent to working with the military population. However, as presented, there are times when counselor ethical codes conflict with military regulations. Counselors interested in working in the military setting or with military personnel may consider decision-making models to address ethical dilemmas.

Recommendations for Counselors

The military mental health system has almost exclusively employed psychologists and social workers. Counselors interested in employment within VA agencies or as TRICARE providers may utilize the resources created by these practitioners to better serve the military population. Two ethical decision-making models are presented, and a case study is provided to demonstrate how to implement the models.

Ethical Models