Self-Reported Symptoms of Burnout in Novice Professional Counselors: A Content Analysis

Ryan M. Cook, Heather J. Fye, Janelle L. Jones, Eric R. Baltrinic

This study explored the self-reported symptoms of burnout in a sample of 246 novice professional counselors. The authors inductively analyzed 1,205 discrete units using content analysis, yielding 12 categories and related subcategories. Many emergent categories aligned with existing conceptualizations of burnout, while other categories offered new insights into how burnout manifested for novice professional counselors. Informed by these findings, the authors implore counseling scholars to consider, in their conceptualization of counselor burnout, a wide range of burnout symptoms, including those that were frequently endorsed symptoms (e.g., negative emotional experience, fatigue and tiredness, unfulfilled in counseling work) as well as less commonly endorsed symptoms (e.g., negative coping strategies, questions of one’s career choice, psychological distress). Implications for novice professional counselors and supervisors are offered, including a discussion about counselors’ experiences of burnout to ensure they are providing ethical services to their clients.

Keywords: novice professional counselors, burnout, content analysis, conceptualization, symptoms

The term high-touch professions refers to the fields that require professionals to provide ongoing and intense emotional services to clients (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Although such work can be highly rewarding, these professionals are also at risk for burnout (Bardhoshi et al., 2019). In counseling, professionals are called to provide ongoing and intensive mental health services to clients with trauma histories (Foreman, 2018) and complicated needs (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014). The risk of burnout is exacerbated by the fact that counselors often work in professional environments that are highly demanding and lack resources to serve their clients (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

The consequences of burnout for counselors and clients can be considerable (Bardhoshi et al., 2019). Potential impacts include a decline in counselors’ self-care, strain of personal relationships, and damage to their overall emotional health (Bardhoshi et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2020; Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Unaddressed burnout might also lead to more serious professional issues like impairment (e.g., substance use, mental illness, personal crisis, or illness; Lawson et al., 2007). Thus, self-monitoring symptoms of burnout is of the utmost importance for counselors to ensure they are providing ethical services to their clients (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014).

Although burnout is an occupational risk to all counselors (e.g., Bardhoshi et al., 2019; J. Lee et al., 2011; S. M. Lee et al., 2007), novice professional counselors may be especially vulnerable to burnout (Thompson et al., 2014; Westwood et al., 2017; Yang & Hayes, 2020). In the current study, we define novice professional counselors as those who are currently engaged in supervision for licensure in their respective states. Novice professional counselors face a multitude of challenges, such as managing large caseloads, working long hours for low wages, and receiving limited financial support for client care (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014). Even though their professional competencies are still developing (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013), these counselors receive minimal direct oversight from a supervisor (Cook & Sackett, 2018). However, to date, no study has exclusively examined novice professional counselors’ descriptions of their experiences of burnout. Input from these counselors is important to understand their specific issues of counselor burnout. Other helping professionals have studied a rich context of practitioners’ burnout experiences. For example, Warren et al. (2012) examined open-ended text responses of people who treated clients with eating disorders and found nuanced contributors to burnout among these providers, including patient descriptors (e.g., personality, engagement in treatment), work-related descriptors (e.g., excessive work hours, inadequate resources), and therapist descriptors (e.g., negative emotional response, self-care). Accordingly, we employed a similar approach to examine the open-ended qualitative responses of 246 novice professional counselors’ self-reported symptoms of burnout.

Conceptual Framework of Burnout

Burnout is defined as “a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” (Maslach & Leiter, 2016, p. 103). Although there are multiple conceptual frameworks of burnout (e.g., Kristensen et al., 2005; S. M. Lee et al., 2007; Maslach & Jackson, 1981; Shirom & Melamed, 2006; Stamm, 2010), the predominant model used to study burnout is the one developed by Maslach and Jackson (1981), which is measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Informed by qualitative research, Maslach and Jackson (1981) developed the MBI and conceptualized burnout for all human service professionals as a three-dimensional model consisting of Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Decreased Personal Accomplishment. Exhaustion is signaled by emotional fatigue, loss of energy, or feeling drained. Depersonalization is characterized by cynicism or negative attitudes toward clients, while Decreased Personal Accomplishment is indicated by a lack of fulfillment in one’s work or feeling ineffective. This conceptualization of burnout has been used to develop several versions of the MBI that are targeted for different professions (e.g., human services, education) and for professionals in general.

Despite the prominence of the MBI model in the burnout literature (Koutsimani et al., 2019), other scholars (e.g., Kristensen et al., 2005; Shirom & Melamed, 2006) have argued for a different conceptualization of burnout, noting several shortcomings of Maslach and Jackson’s (1981) three-dimensional model. Shirom and Melamed (2006) criticized the lack of theoretical framework of the MBI and noted that the factors were derived via factor analysis. They developed the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (Shirom & Melamed, 2006), a measure informed by the Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), which measures burnout as a depletion of physical, emotional, and cognitive resources using two subscales: Physical Fatigue and Cognitive Weariness.

Kristensen et al. (2005) also criticized the utility of the MBI for numerous reasons, including the lack of theoretical underpinnings of the instrument. Therefore, they developed the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory to capture burnout in professionals across disciplines, most notably human service professionals. From Kristensen et al.’s perspective, the underlying cause of burnout is physical and psychological exhaustion, which occurs across three domains: Personal Burnout (i.e., burnout that is attributable to the person themselves), Work-Related Burnout (i.e., burnout that is attributable to the workplace), and Client-Related Burnout (i.e., burnout that is attributable to their work with clients; Kristensen et al., 2005).

Stamm (2010) conceptualized the construct of professional quality of life for helping professionals, which included three dimensions: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress. Burnout, as theorized by Stamm, is marked by feelings of hopelessness, frustration, and anger, as well as a belief that one’s own work is unhelpful to others, which results in a decline in professional performance. The experience of burnout may also be caused by an overburdening workload or working in an unsupportive environment (Stamm, 2010). Stamm’s model is reflected in the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL), and this instrument has been used by counseling scholars (e.g., Lambert & Lawson, 2013; Thompson et al., 2014).

A reason for variations in the conceptualization of burnout is that it manifests differently across professions (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). The only counseling-specific model of burnout is conceptualized by S. M. Lee et al. (2007), who developed the Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI). The CBI was informed by the three dimensions of the MBI and additionally captured the unique work environment of professional counselors and its impact on their personal lives. As such, the CBI poses a five-dimensional model consisting of Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Client, and Deterioration in Personal Life. In recent years, the CBI has been the instrument predominantly used by researchers to study counselor burnout (e.g., Bardhoshi et al., 2019; Fye et al., 2020; J. Lee et al., 2011).

The Current Study

J. Lee et al. (2011) noted the challenges of studying counselor burnout across diverse samples. They encouraged scholars to examine burnout within homogenous samples of counselors in order to offer more nuanced implications for each group. Prior scholarship (e.g., Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Thompson et al., 2014) suggested that novice professional counselors may be at risk of burnout, and despite the aforesaid vulnerabilities (e.g., low wages, work with high need clients, professional competency limitations), their self-reported manifestation of burnout symptoms have yet to be studied.

We acknowledge the critical importance of studying burnout in the profession of counseling. However, repeatedly relying on data from similar instruments to measure burnout may fail to capture new or relevant information about the phenomenon (Kristensen et al., 2005) for human service professionals (e.g., Maslach & Jackson, 1981) or professional counselors (e.g., S. M. Lee et al., 2007). Alternatively, content analysis, which focuses on the analysis of open-ended qualitative text (Krippendorff, 2013), may better capture the intricacies of burnout that could not be measured using quantitative instruments (e.g., Warren et al., 2012). Thus, we aimed to address the following research question: What are novice professional counselors’ self-reported symptoms of burnout?

Methodology

Participants

Participants in the current study were 246 postgraduate counselors who were currently receiving supervision for licensure. The age of participants ranged from 23 to 69, averaging 36.91 (SD = 10.15) years. The majority of participants identified as female (n = 195, 79.3%), while 22 participants identified as male (8.9%), four identified as non-binary (1.6%), nine indicated that they did not want to disclose their gender (3.7%), and 16 participants did not respond to the item (6.5%). The participants’ race/ethnicity was reported as follows: White (n = 186; 75.6%), Multiracial (n = 15, 6.1%), Latino/Hispanic (n = 7, 3.3%), Black (n = 6, 2.4%), Asian (n = 6, 2.4%), American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 3, 0.8%), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (n = 1, 0.4%), and Other (n = 7, 3.3%), while 15 participants declined to respond to the item (6.1%). The self-reported race/ethnicity demographic information is comparable to all counselors in the profession, based on DataUSA (2018). The participants’ client caseload ranged from 1 to 650 (M = 41.88; Mdn = 30.0; SD = 53.74). On average, participants had worked as counselors for 5 years (Mdn = 3.3; SD = 4.87). The provided percentages may not total to 100 percent because of rounding and because participants were afforded the option to select more than one response.

Procedure

To answer our research question, we used data from a larger study of novice professional counselor burnout, which included both quantitative and qualitative data. After receiving IRB approval, we obtained lists of names and email addresses of counselors engaged in supervision for licensure from the licensing boards in seven states: Florida, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin. We aimed to recruit a nationally representative sample by purposefully choosing at least one state from each of the ACA regions. In addition, states were selected based upon our ability to obtain a list of counselors who were engaged in supervision for licensure from the respective licensure boards. We were able to survey at least one state from each ACA region except the North Atlantic Region. After removing invalid email addresses, we invited 6,874 potential participants by email to complete an online survey in Qualtrics. This survey was completed by 560 counselors, yielding a response rate of 8.15%. This response rate is consistent with other studies that employed a similar design (Gonzalez et al., 2020). All participants were asked, Do you believe you are currently experiencing symptoms of burnout?, to which participants responded (a) yes or (b) no. Participants who responded yes were then prompted with the direction, Describe your symptoms of burnout, using an open-ended text box, which did not have a character limit. A total of 246 participants (43.9%) responded yes and qualitatively described their symptoms of burnout. On average, participants provided 30.31 words (SD = 36.30). We answered our research question for the current study using only the qualitative data, which aligns with the American Psychological Association’s Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research (JARS-Qual; Levitt et al., 2018).

Data Analysis

To answer our research question, we analyzed participants’ open-ended responses using content analysis, which allows for systematic and contextualized review of text data (Krippendorff, 2013). As recommended by Krippendorff (2013), we followed the steps of conducting content analysis: unitizing, sampling, recording, and reducing. We first separated the responses of the 246 participants into discrete units. For example, “feeling exhausted and back pain” was coded as two units: (a) feeling exhausted and (b) back pain. This process resulted in a total of 1,205 discrete units. We reduced our data into categories using an inductive approach, which allowed for new categories to emerge from the data without an a priori theory (Krippendorff, 2013). Although there are multiple conceptualizations of burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981; S. M. Lee et al., 2007) that could have informed our analysis (i.e., deductive approach; Krippendorff, 2013), we chose an inductive approach to capture the conceptualization of burnout for novice professional counselors—generating categories based on participants’ explanations of their own symptoms of burnout (Kondracki et al., 2002).

To that end, we developed a codebook by randomly selecting roughly 10% of the discrete units to code as a pretest. Our first and third authors, Ryan M. Cook and Janelle L. Jones, independently reviewed the discrete units, met to discuss and develop categories and corresponding definitions, and coded the pretest data together to enhance reliability. This process yielded a codebook that consisted of 12 categories. Cook and Jones then used the codebook (categories and definitions) to independently code the remaining 90% of the data across three rounds (i.e., 30% increments). After each round, Cook and Jones met to discuss discrepancies and to reach consensus on the final codes. The overall agreement between Cook and Jones was 97% and the interrater reliability was acceptable (Krippendorff α = .80; Krippendorff, 2013), which was calculated using ReCal2 (Freelon, 2013). At the end of the coding process, Cook and Jones reviewed their notes for each code and further organized them into subcategories based on commonalities. The second author, Heather J. Fye, served as the auditor (see Researcher Trustworthiness section) and reviewed the entire coding process.

Researcher Trustworthiness

The research team consisted of four members, three counselor educators and one counselor education and supervision doctoral student. The first and third authors, Cook and Jones, served as coders, while the second author, Fye, served as the auditor and the fourth author, Eric R. Baltrinic, served as a qualitative consultant. The counseling experience of the four authors ranged from 4 to 18 years, and the supervision experience of the authors ranged from 3 to 9 years. Cook, Fye, and Baltrinic are licensed professional counselors and three of the authors are credentialed as either a National Certified Counselor or Approved Clinical Supervisor.

We all acknowledged our personal experiences of burnout to some degree as practicing counselors as well as observing the consequences of burnout to our students and supervisees. All members of the research team had prior experience studying counselor burnout. Although these collective experiences enriched our understanding of the subject matter, we also attempted to bracket our assumptions and biases throughout the research process. To increase the trustworthiness of the coding process, the auditor, Fye, reviewed the codebook, categories and subcategories, discreteness, and two coders’ notes coding process after the pretest and rounds of coding. Fye provided feedback on the category definitions, coding process, and coding decisions during the analysis process.

Results

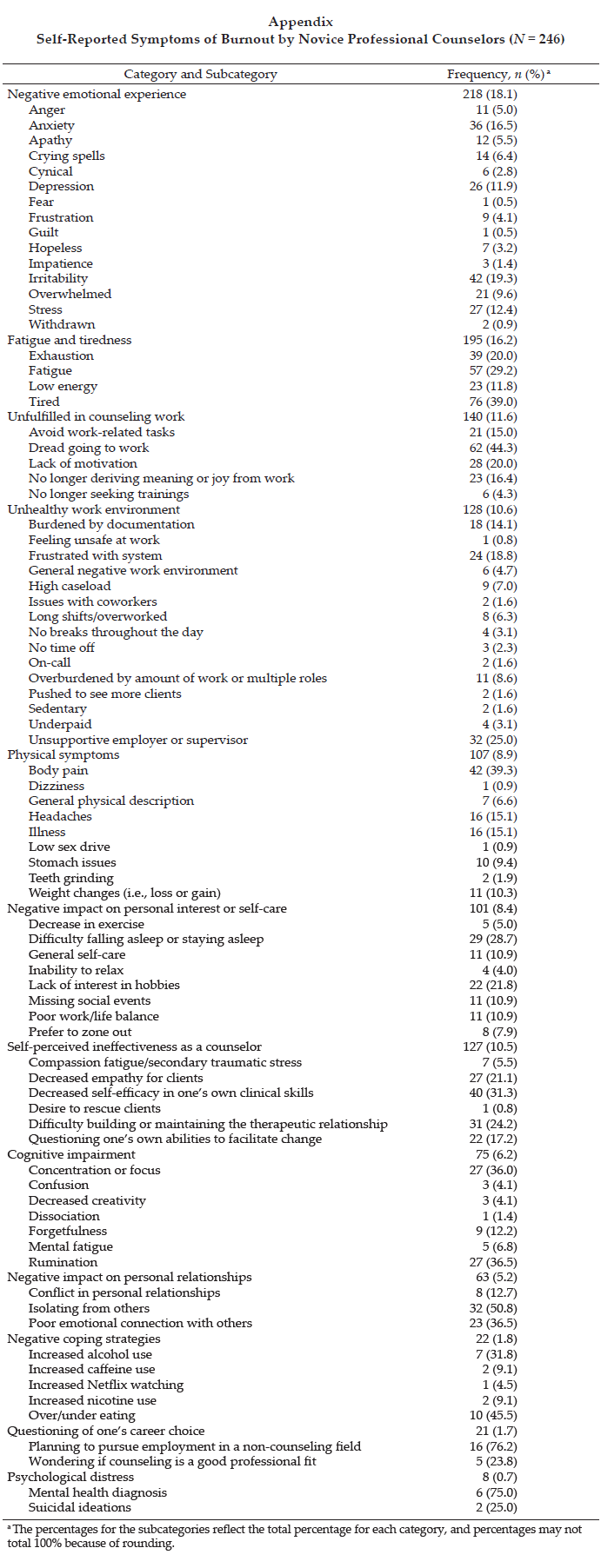

Using an inductive approach, 12 categories and related subcategories emerged from the 1,205 discrete self-reported symptoms of burnout. Full results, including the 12 categories and subcategories, as well as the frequencies of the categories and subcategories, are presented in the Appendix. We discuss each category in detail and provide illustrative examples of each category using direct participant quotes (Levitt et al., 2018).

Negative Emotional Experience

Of the 1,205 coded units, 218 units (18.1%) were coded into the category negative emotional experience. This category reflected participants’ descriptions of experiencing negative feelings related to their work as counselors (e.g., anxiety, depression, irritability) or unwanted negative emotions (e.g., crying spells). This category included 15 subcategories, and the units coded into these subcategories reflected the participants’ descriptions of a wide range of negative feelings. For example, one participant reported she was “struggling to feel happy,” while another participant shared that she “is carrying a heavy burden [that] no one understands or is aware of.” Some participants also reported crying spells. One participant shared she “has fits of crying,” while another reported she “[cries] in the bathroom at work.”

Fatigue and Tiredness

The category fatigue and tiredness was coded 195 times (16.2%) and included four subcategories. This category captured participants’ descriptions of feeling exhausted, fatigued, or tired. Units coded into this category included the participants’ indications that they feel exhausted, despite sleeping well. For example, one participant described feeling perpetually exhausted—“nothing recharges my batteries”— while another participant stated that her fatigue worsened as the week progressed: “[I feel] more and more exhausted throughout the week.”

Unfulfilled in Counseling Work

The category unfulfilled in counseling work captured the participants’ descriptions of no longer deriving joy at work, dread in going to work or completing work-related responsibilities, or lacking motivation to do work. This category was coded 140 times (11.6%) and subcategories included five subcategories. Avoidance of burdensome administrative responsibilities (e.g., paperwork) were commonly reported units that were captured in this category. For example, a participant noted “putting off doing notes.” Units also captured in this category reflected participants’ self-report of no longer feeling motivated or deriving joy from their work, which ultimately led some participants to stop seeking training. For instance, a participant described herself as “going through the motions at work,” and another added that she was no longer “motivated to improve [her] skills.”

Unhealthy Work Environment

Across all coded units, 128 units (10.6%) were coded in the category unhealthy work environment, which included 15 subcategories. This category captured participants’ descriptions of their work environment that contribute to a counselor experiencing burnout. For example, units captured in this category commonly described participants’ reports of working long hours with few or no breaks throughout the day, and participants feeling pressured to take on additional clients. Some participants described managing large client caseloads or caseloads with “high risk or high needs” clients. The units reflecting participants’ perceived lack of supervisor support were also coded into this category. For example, a participant noted that she was “scared to make a mistake or ask questions about doing my job,” while another participant described a supervisor as not “supportive or trustworthy.” Finally, units that signaled participants’ feelings of being inadequately compensated were coded into this category, such as this participant’s response: “I do not get paid enough for the work that I do.”

Physical Symptoms

The category physical symptoms reflected participants’ descriptions of physical ailments, physical manifestations of burnout (e.g., soreness, pain), physical illnesses, or physical descriptors (e.g., weight gain, weight loss). There were 107 coded units (8.9%) that referenced physical symptoms. The seven subcategories captured in this category reflected a wide range of physical ailments. The most commonly coded units were participants’ descriptions of headaches, illnesses, and weight changes, although some less commonly coded units reflected more serious physical and medical issues. For example, a participant noted, “I have TMJ [temporomandibular joint dysfunction] pain most days from clenching my jaw,” while another participant stated that she “recently began to have debilitating stomach symptoms, which were identified as small ulcerations.”

Negative Impact on Personal Interest or Self-Care

Across all coded units, 101 units (8.4%) were coded in the category negative impact on personal interest or self-care, which included eight subcategories. This category reflected the participants’ descriptions of reduced self-care or inability to engage in self-perceived healthy behaviors (e.g., cannot fall asleep), or lacking personal interest. Units coded in this category most commonly reflected participants’ experience of sleep issues—difficulty either falling asleep or staying asleep. Other units reflected participants’ lessening desire to engage in once-enjoyable activities. For example, one participant noted, “I find myself knowing that I need more time for play, rest, recovery, socializing, and personal interests, but [I am] feeling confused about how to fit that in.” Another participant described her self-care as unconstructive: “It often feels like no amount of self-care is helpful, which makes it more difficult to engage in any self-care.”

Self-Perceived Ineffectiveness as a Counselor

We coded 127 units (10.5%) into the category self-perceived ineffectiveness as a counselor, which included six subcategories. This category reflected the participants’ descriptions of their self-perceived decrease in self-efficacy as a counselor, difficulty in developing or maintaining therapeutic relationships with clients, decreased empathy toward clients, or questioning of their own abilities as counselors (e.g., ability to facilitate change). For example, one participant noted that she did not “have as much empathy for clients as before,” while another participant expressed, “I often feel like clients are being demanding and trying to waste my time.” Units coded into this category also reflected participants’ feelings of inadequacy or struggles to develop a meaningful professional relationship with clients. One participant stated that she must “reach very deep every morning for the presence of mind and spirit to pay close attention and to care deeply for each of these people.” Although less frequently coded, some units described participants’ feelings of compassion satisfaction or self-reported secondary traumatic stress. For example, one participant shared that she was “personally disturbed” by her work.

Cognitive Impairment

Across all coded units, 75 units (6.2%) were coded in the category cognitive impairment, and this category included seven subcategories. The units coded into this category reflected the participants’ descriptions of their cognitive abilities being negatively impacted in different ways. For example, one participant described “feeling like I am in a fog at work,” while another participant shared that she found it “hard to concentrate at work.” Some units captured in this category reflected participants’ rumination of clients or work; for example, one participant noted “shifting my attention to ruminating about dropouts at times, when I need to be present with a [current] client.”

Negative Impact on Personal Relationships

The category negative impact on personal relationships captured 63 coded units (5.2%). Participants’ descriptions of strained relationships as a result of their self-reported burnout were coded into this category, which included three subcategories. For example, one participant described “not [feeling] available for emotional connects with others in my personal life,” while another participant said that they “lashed out sometimes at family members after a stressful day of work.” Another example of the negative impact on personal relationships was a participant’s description of “struggling to find joy at home with my wife and two kids.”

Negative Coping Strategies

We coded 22 units (1.8%) into the category negative coping strategies. This category included five subcategories that captured participants’ descriptions of using unhealthy or negative coping strategies to cope with burnout. Units coded into this category described participants’ use of a variety of negative coping strategies. For example, participants noted an increase in “alcohol consumption” or “smoking.” Relatedly, a participant expressed one of her coping strategies was “the excessive use of Netflix,” while another participant stated that she was “not eating or eating way too much.”

Questioning of One’s Career Choice

Units that reflected participants’ descriptions of the questioning of one’s career choice and potential or planned desire to leave the profession were coded into the category questioning of one’s career choice. There were 21 coded units (1.7%) for this category, which included two subcategories. An example of units coded into this category is a participant who stated that she has “thoughts that I have made a mistake in pursuing this line of work.” Another participant shared feelings of “wanting to quit [my] job.” Some units coded into this category captured participants who were already making plans to leave their jobs or the field. For example, one participant shared that she “recently put in [my] notice at agency,” while another participant stated plans to leave the profession “within one year.”

Psychological Distress

The least number of units were coded into the category psychological distress, which was coded eight times (0.7%) and included two subcategories. This category captured the participants’ discussions of a mental health diagnosis, which they attributed as a symptom of burnout, or suicidal ideations. For example, one participant shared, “I have been diagnosed with major depressive disorder and my job is a factor,” while another participant stated, “I sought therapy for myself and I had to increase my anti-depressant medication.” Finally, two participants endorsed experiencing suicidal ideations at some previous point related to their burnout.

Discussion

The content analysis yielded insights of self-reported burnout symptoms by capturing the phenomenon in novice professional counselors’ own words. Many of the 12 categories that emerged from the data generally aligned with prior conceptualizations of burnout for human service professionals (e.g., Maslach & Jackson, 1981) and counselors (S. M. Lee et al., 2007), while some categories provided novel insights into how burnout manifested in this sample. Further, we observed trends in common self-reported descriptors of burnout for novice professional counselors (negative emotional experiences) to the least commonly endorsed descriptors (psychological distress). We assert that these findings enrich the scholarly understanding of the burnout phenomenon in novice professional counselors.

Discussion of the Conceptual Framework of Burnout

Maslach and Jackson (1981) emphasized in their earlier work that exhaustion and fatigue are core features of burnout, and the category of fatigue and tiredness was the second most commonly coded category (16.2% of all coded units) in our study. Our findings reaffirm exhaustion (or fatigue or tiredness) as a central feature of burnout, and specifically self-reported symptoms of burnout in novice professional counselors. Scholars (e.g., Kristensen et al., 2005; Maslach & Jackson, 1981; Shirom & Melamed, 2006) have conceptualized that the interconnectedness between the emotional, physical, and psychological fatigue of burnout is different. Shirom and Melamed (2006) distinguished emotional, physical, and cognitive resources, while Kristensen et al. (2005) made no distinction between physical and psychological exhaustion. Stamm (2010) also viewed exhaustion as a feature of burnout but did not specify how this exhaustion manifested in human service professionals. In the current study, we chose to distinguish emotional, physical, and cognitive symptoms to best capture the participants’ experiences in their own words (Kondracki et al., 2002). However, we found supportive evidence that novice professional counselors’ burnout included emotional, physical, and cognitive symptoms. Our findings suggest that all three components should be examined to adequately capture this phenomenon.

The category negative emotional experience, which reflected participants’ reports of experiencing negative feelings associated with their work as counselors, was the most commonly endorsed symptom of burnout (18.1% of all coded units). In other models of burnout (e.g., Kristensen et al., 2005; Shirom & Melamed, 2006), feelings or emotions are most often conceptualized as emotional exhaustion, emotional fatigue, or emotional distress. However, the participants in the current study richly described their negative emotional experiences, as captured in the subcategories, with irritability, anxiety, depression, and stress being the most commonly endorsed negative emotions. These findings most closely align with Stamm’s (2010) conceptualization of burnout, which suggested that feelings of hopelessness, anger, frustration, and depression are evidence of burnout. Relatedly, a similar content analysis performed with eating disorder treatment professionals also found that their participants most frequently described emotional distress (61% of their sample, n = 94) as a way in which their worry for clients impacts their personal and professional lives (Warren et al., 2012). Scholars (e.g., Maslach & Leiter, 2016) have postulated about the relationship between workplace burnout and affectional distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, stress); however, such an investigation has yet to be conducted in the profession of counseling. Our findings suggest that novice professional counselors commonly describe their manifestation of burnout as an emotional experience, and as such, this represents a gap in the current conceptualization of counselor burnout.

Two other categories captured in the current study were physical symptoms and cognitive impairment symptoms. Physical symptoms were coded for 8.9% of the 1,205 units coded, while cognitive symptoms were coded for 6.1% of all coded units. In the existing burnout literature (e.g., Maslach & Jackson, 1981; Shirom & Melamed, 2006), physical symptoms of burnout often paralleled or referenced fatigue or exhaustion. For example, in Shirom and Melamed’s (2006) model, physical symptoms were reflective of feeling physically tired. However, in the current study, participants most commonly described their physical symptoms as back pain, illnesses, and headaches. This finding aligns with Kaeding et al. (2017), who found that counseling and clinical psychology trainees attributed their back and neck pain to sitting for long periods of time. We assert that specific physical symptoms may have been inadequately captured by the existing models of burnout.

Relatedly, Shirom and Melamed (2006) suggested that psychological fatigue or psychological manifestations of burnout should be distinguished from those of emotional and physical symptoms, while Kristensen et al. (2005) made no such distinctions. The participants in the current study described numerous cognitive manifestations of burnout, and the most commonly coded subcategories included concentration or focus, rumination, and forgetfulness. These self-reported symptoms closely align with the model of Shirom and Melamed, which describes psychological fatigue as an inability to think clearly and difficulty processing one’s own thoughts. Further, Kristensen et al. described one symptom of personal burnout as being at risk of becoming ill. However, no items of cognitive impairment or worsening cognitive abilities are included in the CBI. Informed by our findings, descriptors of cognitive impairment should be considered to understand burnout in novice professional counselors.

Two of the three dimensions of burnout as conceptualized by Maslach and Jackson (1981) were Depersonalization (i.e., cynicism or negative attitudes toward clients) and Decreased Personal Accomplishment (i.e., diminished fulfillment in one’s work or feeling ineffective in their work). These two dimensions are similar to Stamm’s (2010) conceptualization of burnout for human service professionals, which included the features of perceiving that one’s own work is unhelpful and no longer enjoying the work. In the current study, two of the categories that emerged closely aligned with these conceptualizations of burnout: unfulfilled in counseling work (11.6% of all coded units) and self-perceived ineffectiveness as a counselor (10.5% of all coded units). Collectively, these two categories and related subcategories provide rich descriptors of how novice professional counselors experience their own depersonalization and diminished personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

Our findings align with qualitative studies of novice professional counselors’ experiences (e.g., Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013). For example, Freadling and Foss-Kelly (2014) found that novice professional counselors sometimes question if their graduate training adequately prepared them for their current positions. As such, questioning of one’s clinical abilities by counselors at this developmental level was also a common experience by participants in our study (Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014).

Our findings were consistent with the counselor-specific burnout model in which S. M. Lee et al. (2007) noted the importance of including the unique work environment of counselors and related impact on their personal life. Our findings support the burnout conceptualization with novice professional counselors. For example, participants in the current study described an unhealthy work environment (10.6% of all coded units). The most commonly coded subcategories included unsupportive employer or supervisor, frustrated with system, burdened by documentation, and overburdened by amount of work or multiple roles.

In terms of the impact of counseling work on their personal lives (S. M. Lee et al., 2007), evidence of this dimension was captured in the current study in two categories: negative impact on personal interest or self-care and negative impact on personal relationships. There is a high degree of interconnectedness between burnout and self-care (Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Warren et al., 2012). Thus, it is unsurprising that participants reported a decrease in their self-care; however, some of the specific self-care behaviors that are affected as a result of novice professional counselors experiencing burnout are less understood. In the current study, the most commonly coded subcategory was difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, followed by lack of interest in hobbies, poor work/life balance, and general decrease in self-care. As defined in the CBI, lack of time for personal interest and poor work/life balance are both indicators of Deterioration in Personal Life. While sleep onset and maintenance issues are associated with burnout (Yang & Hayes, 2020), counselors’ experiences with sleep issues appears to be a novel finding. Another indicator of deterioration in counselors’ personal lives as theorized by S. M. Lee et al. was a lack of time to spend with friends, which was also observed in our study. Relatedly, some participants indicated that they isolated from their social support system. Other participants described strained personal relationships (i.e., conflict in personal relationships, poor emotional connection with others), which are unique findings.

Counselor Burnout Versus Counselor Impairment

Although uncommonly reported, some participants in the current study described using negative coping strategies (1.8% of all coded units) and psychological distress (0.7% of all coded units) as evidence of their self-reported burnout. Examples of negative coping strategies reported by participants included increased substance use (e.g., alcohol, caffeine, nicotine) and overeating or skipping meals, while examples of psychological distress included having received a psychological diagnosis and experiencing increased suicidal ideations, which participants attributed to burnout. These self-reported symptoms of burnout align more closely with the definition of counselor impairment (Lawson et al., 2007) as opposed to the definition of counselor burnout. Our findings are significant for two reasons. First, any study of counselor burnout that utilized one of the commonly used instruments of burnout (e.g., CBI, MBI) would have failed to capture these participants’ experiences. Second, these findings suggest that a small number of counselors may be experiencing significant impairment in their personal and professional lives, despite being early in their professional careers. Finally, another infrequently coded category was questioning of one’s career choice (1.7% of all coded units). Coded units in this category indicated that some counselors were wondering if counseling was a good professional fit for them, while others expressed their intention to seek employment in another profession. It is possible that prolonged disengagement from one’s professional work (i.e., cynicism; Maslach & Jackson, 1981) could result in counselors wanting to explore other career options.

Limitations

There are limitations of this study which we must address. The purpose of content analysis is not to generalize findings, so our findings may only reflect the experiences of burnout for the participants in the current study. Their experiences may be influenced by developmental levels, experiences in their specific state, or other reasons that we did not capture.

Another limitation is our response rate of 8.15%. A possible reason for our low response rate is self-selection bias—counselors who were currently experiencing burnout responded to the open-ended items as opposed to those who were not feeling burnout. Future research is needed to see how burnout presents in larger or different populations of counselors. It might also be important to study the career-sustaining behaviors and work environments of those counselors who did not endorse burnout. The final limitation is that this study was descriptive in nature. Future researchers are encouraged to explore the factors that may predict burnout while also considering the novel findings generated from this study.

Implications

Our findings offer implications for counseling researchers, counselors, and supervisors. Although many of the findings from the current study align with prior research, there appears to be some degree of discrepancy between how burnout is conceptualized by scholars and how novice professional counselors describe symptoms of burnout. We implore scholars to further examine the specific descriptors of burnout as reported by participants in this study and to see if the frequency of these self-reported symptoms can be duplicated. Specifically, scholars should focus on the emotional experience of novice professional counselors, fatigue and tiredness, and feeling unfulfilled in their work, which were the most commonly reported symptoms. It also seems critically important to explore the less commonly reported descriptors of burnout, like negative coping strategies, questioning of one’s career choice, and psychological distress. Each of these categories could signal counselor impairment and would have been otherwise missed by scholars who relied exclusively on existing Likert-type burnout inventories.

Novice professional counselors sometimes experience self-doubt about their counseling skills or even the profession (Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013), given the difficult work conditions in which these counselors practice (e.g., low wages, long hours; Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014). Novice professional counselors should understand that experiences of burnout appear to be commonly occurring. The illumination of these descriptors may encourage other novice professional counselors to seek guidance from their supervisors on how best to manage these feelings. For those novice professional counselors who are experiencing more serious personal and professional issues associated with burnout (e.g., using negative coping strategies and psychological distress), they should consider whether they are presently able to provide counseling services to clients and seek consultation from a supervisor (ACA, 2014).

Our findings have implications for supervisors. For example, supervisors should be willing to openly discuss burnout with their supervisees. Our results can provide supervisors with descriptors that capture novice professional counselors’ experiences of burnout. Supervisors might find it helpful to disclose some of their own experiences of burnout (or mitigating burnout) with their supervisees, which can normalize the supervisees’ experiences (Knox et al., 2011). Finally, to the extent that supervisors are able, they should protect novice professional counselors from experiencing an unhealthy work environment or potentially harmful behaviors. For example, in response to supervisees’ self-reported symptoms of burnout, supervisors could limit caseloads, allow counselors time to complete documentation, or mandate regular breaks throughout the day (including lunchtime).

Conclusion

There are many novice professional counselors experiencing a wide range of symptoms of burnout. A career in counseling can be rewarding, but prolonged burnout can lead to both personal and professional consequences, as evidenced by the findings from this study. Counselors must attend to their own symptoms of burnout in order to provide quality care to their clients and lead a fulfilling personal life. Supervisors and educators can support these counselors by discussing the experiences of burnout, and future scholars can better understand the experiences of counselor burnout by studying the phenomenon using definitions and symptoms in the words of counselors as opposed to generic definitions.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics.

Bardhoshi, G., Erford, B. T., & Jang, H. (2019). Psychometric synthesis of the Counselor Burnout Inventory. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12250

Cook, R. M., Fye, H. J., & Wind, S. A. (2020). An examination of the Counselor Burnout Inventory using item response theory in early career post-master’s counselors. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2020.1827439

Cook, R. M., & Sackett, C. R. (2018). Exploration of prelicensed counselors’ experiences prioritizing information for clinical supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(4), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12226

DataUSA. (2018). Counselors. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/counselors#demographics

Foreman, T. (2018). Wellness, exposure to trauma, and vicarious traumatization: A pilot study. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 40(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.40.2.04

Freadling, A. H., & Foss-Kelly, L. L. (2014). New counselors’ experiences of community health centers. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53(3), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00059.x

Freelon, D. (2013). ReCal OIR: Ordinal, interval, and ratio intercoder reliability as a web service. International Journal of Internet Science, 8(1), 10–16.

Fye, H. J., Cook, R. M., Baltrinic, E. R., & Baylin, A. (2020). Examining individual and organizational factors of school counselor burnout. The Professional Counselor, 10(2), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.15241/hjf.10.2.235

Gonzalez, E., Sperandio, K. R., Mullen, P. R., & Tuazon, V. E. (2020). Development and initial testing of the Multidimensional Cultural Humility Scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 54(1), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2020.1745648

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Kaeding, A., Sougleris, C., Reid, C., van Vreeswijk, M. F., Hayes, C., Dorrian, J., & Simpson, S. (2017). Professional burnout, early maladaptive schemas, and physical health in clinical and counselling psychology trainees. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(12), 1782–1796. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22485

Knox, S., Edwards, L. M., Hess, S. A., & Hill, C. E. (2011). Supervisor self-disclosure: Supervisees’ experiences and perspectives. Psychotherapy, 48(4), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022067

Kondracki, N. L., Wellman, N. S., & Amundson, D. R. (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34(4), 224–230.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60097-3

Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., & Georganta, K. (2019). The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(284), 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Kristensen, T. S., Hannerz, H., Høgh, A., & Borg, V. (2005). The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire: A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 31(6), 438–449. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.948

Lambert, S. F., & Lawson, G. (2013). Resilience of professional counselors following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(3), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00094.x

Lawson, G., Venart, E., Hazler, R. J., & Kottler, J. A. (2007). Toward a culture of counselor wellness. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00022.x

Lee, J., Lim, N., Yang, E., & Lee, S. M. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of three dimensions of burnout in psychotherapists: A meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(3), 252–258.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023319

Lee, S. M., Baker, C. R., Cho, S. H., Heckathorn, D. E., Holland, M. W., Newgent, R. A., Ogle, N. T., Powell, M. L., Quinn, J. J., Wallace, S. L., & Yu, K. (2007). Development and initial psychometrics of the Counselor Burnout Inventory. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 40(3), 142–154.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2007.11909811

Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publication and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000151

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovholt, T. M. (2013). The developing practitioner: Growth and stagnation of therapists and counselors. Routledge.

Shirom, A., & Melamed, S. (2006). A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(2), 176–200.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.2.176

Stamm, B. H. (2010). Professional Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Version 5 (ProQOL).

http://www.proqol.org.

Thompson, I., Amatea, E., & Thompson, E. (2014). Personal and contextual predictors of mental health counselors’ compassion fatigue and burnout. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(1), 58–77.

https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.1.p61m73373m4617r3

Warren, C. S., Schafer, K. J., Crowley, M. E., & Olivardia, R. (2012). A qualitative analysis of job burnout in eating disorder treatment providers. Eating Disorders, 20(3), 175–195.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.668476

Westwood, S., Morison, L., Allt, J., & Holmes, N. (2017). Predictors of emotional exhaustion, disengagement and burnout among improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) practitioners. Journal of Mental Health, 26(2), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2016.1276540

Yang, Y., & Hayes, J. A. (2020). Causes and consequences of burnout among mental health professionals: A practice-oriented review of recent empirical literature. Psychotherapy, 57(3), 426–463.

https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000317

Ryan M. Cook, PhD, ACS, LPC, is an assistant professor at the University of Alabama. Heather J. Fye, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an assistant professor at the University of Alabama. Janelle L. Jones, MS, NCC, is a doctoral student at the University of Alabama. Eric R. Baltrinic, PhD, LPCC-S (OH), is an assistant professor at the University of Alabama. Correspondence may be addressed to Ryan M. Cook, 310A Graves Hall, Box 870231, Tuscaloosa, AL 35475, rmcook@ua.edu.