Evidence-Based Practice, Work Engagement and Professional Expertise of Counselors

Varda Konstam, Amy Cook, Sara Tomek, Esmaeil Mahdavi, Robert Gracia, Alexander H. Bayne

This study examined work engagement and its role in mediating the relationship between organizational support of evidence-based practice (integrating research evidence to inform professional practice) and educational growth and perceived professional expertise. Participants included 78 currently employed counselors, graduates of a master’s program in mental health counseling located in an urban northeastern university. Results revealed that work engagement significantly mediates the relationship between organizational support of evidence-based practice and educational growth and perceived professional expertise. Implications for counseling practice and recommendations for future research are discussed.

Keywords: professional expertise, counselors, evidence-based practice, professional development, work engagement

Although ongoing efforts to maintain and improve clinical competence are intrinsic to ethical practice for counselors (Jennings, Sovereign, Bottorff, Mussell, & Vye, 2005), clinical experience does not appear to guarantee additional skill acquisition among counselors (Goodman & Amatea, 1994; Skovholt & Jennings, 2005). Notably, a meta-analysis conducted by Spengler et al. (2009) revealed that level of education, training and experience had a small effect on clinical judgment (d = .12). Skovholt and Jennings (2005) concluded that “experience alone is not enough” to ensure professional growth and increased professional expertise in counseling practice (p. 15).

Because years of experience only minimally inform professional expertise (defined as the ability to accurately diagnose and implement treatment plans that sensitively incorporate the contexts in which clients are embedded [Meier, 1999]), it is important to isolate both individual and organizational factors that improve professional expertise over time. Individual factors identified in the counseling literature include (a) the importance of self-reflection (Neufeldt, Karno, & Nelson, 1996), (b) exploration of unexamined assumptions about human nature (Auger, 2004), (c) empathy (McLeod, 1999; Pope & Kline, 1999), (d) self-awareness (Richards, Campenni, & Muse-Burke, 2010), (e) mindfulness (Campbell & Christopher, 2012) and (f) cultural competence (Goh, 2005). Organizational factors (defined as organizational systems and processes that are in place to support counselor professional growth linked to organizational and client outcomes) also have been identified (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006a; Bultsma, 2012, Goh, 2005; Perera-Diltz & Mason, 2012; Truscott et al., 2012). The range of studies, however, has been limited in scope, and research has tended to focus on administrative practices associated with staff turnover, morale, efficiency and productivity (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006a).

This research focused on how individual counselors and organizations providing counseling services can promote the continuing development and refinement of professional expertise among practicing counselors. Specifically, we focused on individual work engagement and organizational factors—that is, organizational support of evidence-based practice (EBP) and educational growth, and their relationships to perceived counselor professional expertise. Counselor use of EBP involves engaging in critical analysis of professional practice and integrating research evidence to inform interventions (Carey & Dimmitt, 2008). We propose that organizational support of EBP and educational growth are important job resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008), and that work engagement mediates the relationship between these resources and perceived counselor professional expertise. First, we present a review of the literature related to organizational support of EBP and work engagement, with a specific focus on linking individual and organizational factors to perceived professional expertise.

Evidence-Based Practice

Efforts put forth by the American Counseling Association (Morkides, 2009) and the American Counseling Association Practice Research Network (Bradley, Sexton, & Smith, 2005) have revealed that evidence-based interventions are critical to the optimal functioning of counselors. Implementation of EBP has been increasingly required across a variety of counseling settings, such as in schools (Carey & Dimmitt, 2008; Dimmitt, Carey, & Hatch, 2007; Forman et al., 2013) and nonprofit human services organizations (McLaughlin, Rothery, Babins-Wagner, & Schleifer, 2010). The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Program standards (2009) also have documented the importance of counselors being trained in using data to inform decision-making, although there are no specific guidelines informing counselors and counselor educators how to engage in EBP effectively. Consequently, implementation of EBP has required that practitioners work in new ways, develop and refine existing clinical skills, and at times reconcile philosophical differences between EBP and their respective disciplines (Tarvydas, Addy, & Fleming, 2010).

The requirement that counselors integrate research findings when working with clients serves to not only sharpen their conceptual understanding of treatment effects, but also aligns conceptual understanding with clinical practice. Such alignment affords the counselor a clearer sense of mastery and aids in developing professional confidence (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). At the organizational and individual practitioner levels, supervisors can work to promote the implementation of more efficacious interventions (Brown, Pryzwansky, & Schulte, 2006; Sears, Rudisill, & Mason-Sears, 2006; Truscott et al., 2012). Thus, understanding individual and organizational factors that influence the use of EBP could help inform counselor development and counseling expertise.

Aarons and Palinkas (2007) surveyed comprehensive home-based services case managers working in child welfare settings specifically with respect to their experiences with EBP. The authors reported that organizational support and willingness to adapt EBP to fit unique settings are the best predictors of successful EBP implementation, including positive attitudes toward EBP. When paired with consistent supportive consultations and supervision, implementation of EBP in child services settings has been associated with greater staff retention (Aarons, Sommerfeld, Hecht, Silovsky, & Chaffin, 2009). Researchers have not yet replicated these results with practitioners working across a range of counseling settings, nor have they expanded their analyses to examine the relationship of EBP training and implementation to professional expertise.

In a qualitative study, Rapp et al. (2008) identified barriers to implementing EBP in five Kansas-based community mental health centers participating in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practice Project. Rapp et al. (2008) were able to identify critical strategies that produced successful outcomes and positive attitudes toward EBP on behalf of the staff. These strategies included the following: (a) managers setting expectations and front-line staff monitoring EBP use, (b) members of upper management serving as champions of EBP by proactively keeping organizational focus on EBP, (c) educating all staff on the importance of EBP rather than exclusively targeting the staff using EBP as part of their job responsibilities, and (d) creating leadership teams that included representatives from all levels of responsibility within the organization to monitor progress and identify obstacles to implementing EBP. Similarly, in a survey developed to assess EBP implementation in community mental health settings, Carlson, Rapp, and Eichler (2012) found that the key components of successful EBP implementation were team meetings, professional development and skill-building activities, and use of outcome measures to track progress.

Organizational and individual processes by which EBP contributes to optimal counselor functioning over time are relatively unexplored in the literature. One possible variable to consider when addressing issues related to EBP implementation and counselor effectiveness is work engagement, a work-related state of mind associated with feeling connected and fulfilled in relation to one’s work activities (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). Work engagement holds promise in furthering the understanding of how individuals and organizations that support these individuals can promote the continuing development and refinement of professional expertise (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Schaufeli et al., 2006).

Work Engagement and Professional Expertise

Schaufeli et al. (2006) defined work engagement as “a positive, fulfilling work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (p. 702). Contrary to those who suffer from burnout, engaged individuals have a sense of connection to their work activities and see themselves as capable of dealing with job responsibilities. It is important to note that the literature related to work engagement is represented by a wide array of contexts including those that are business related. The results of these studies, therefore, cannot be generalized to counselors working across a variety of mental health and school settings (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007, 2008; Salanova, Agut, & Pieró, 2005; Sonnentag, 2003). However, the findings in business-related contexts have revealed interesting associations that warrant further examination. For example, Langelaan, Bakker, van Doornen, and Schaufeli (2006) found that in participants working in diverse business settings (e.g., managers working for Dutch Telecom, blue-collar employees working in food processing companies), specific personality qualities associated with work engagement, such as low levels of neuroticism, high levels of extraversion and the ability to adapt to changing job conditions, were correlated with high levels of work engagement. A number of studies also identified a reciprocal relationship between personal resources (self-esteem and self-efficacy), job resources (effective supervision, social support, autonomy and variety in job tasks) and work engagement (Hakanen, Perhoniemi, & Toppinen-Tanner, 2008; Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2009). The participants in the Hakanen et al. (2008) study were Finnish dentists, whereas the Xanthopoulou et al. (2009) study was based on the responses of employees working in three branches of a fast-food company.

Supportive Organizational Contexts, Work Engagement and Professional Expertise

Colquitt, LePine, and Noe (2000) emphasized the importance of providing organizational support in the workplace when considering job performance and work engagement. However, the focus on “situational characteristics such as support remains surprisingly rare” (p. 700). The authors defined organizational support of educational growth as the extent to which the organization supports ongoing professional learning and development. Research findings have suggested that work engagement is positively correlated with job characteristics identified as resources, such as social support from supervisors and colleagues, performance feedback, coaching, job autonomy, task variety, and training facilities (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001; Salanova et al., 2005; Salanova, Bakker, & Llorens, 2006; Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003; Schaufeli, Taris, & van Rhenen, 2008). According to Bakker, Giervels, and Van Rijswijk (as cited by Bakker & Demerouti, 2008), engaged employees have been successful in mobilizing their job resources and influencing others to perform better as a team.

In accordance with the model proposed by Bakker and Demerouti (2008), work engagement, in the context of perceived counselor professional expertise, mediates the relationship between job and personal resources and job-related performance. Job resources (e.g., organizational support of EBP, organizational support of educational growth) and personal resources inform work engagement, especially in jobs with high demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Bakker, Hakanen, Demerouti, & Xanthopoulou, 2007; Salanova et al., 2005). We propose that organizational support of educational growth and organizational support of EBP are important job resources as conceptualized by the Bakker and Demerouti model, and that work engagement mediates the relationship between these resources and counselor professional expertise.

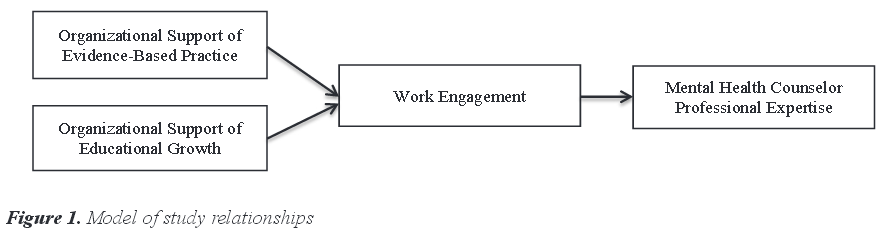

This study addresses a gap in the literature by focusing on understanding the relationships among work engagement, organizational support of EBP and organizational support of educational growth with respect to perceived professional expertise in practicing counselors. To our knowledge, no research to date has linked the systematic organizational implementation of EBP and organizational support of educational growth with the proposed mediating role of work engagement in relationship to counselor perceived professional expertise. See Figure 1 for the proposed mediation model. In addition, the participants of this study function across a variety of counseling settings including schools, hospitals and mental health agencies.

It is important to determine whether a supportive professional context in general, rather than support specific to EBP, accounts for the relationship between EBP and work engagement. We assessed an alternative source of organizational support: support of educational growth, defined as the extent to which the organization supports ongoing professional learning and development. We hypothesized that organizational support of EBP uniquely contributes to work engagement, independent of support of educational growth. We hypothesized the following:

Organizational support of EBP, organizational support of educational growth and professional expertise will all be positively related to each other.

Work engagement will significantly mediate the relationship between organizational support of EBP and educational growth, and in turn will increase perceived professional expertise, as proposed by Bakker and Demerouti (2008).

Methods

Participants

The participants for this study included 78 graduates of a master’s program in mental health counseling located in an urban university in the northeastern part of the United States. The graduates of the counseling program were exposed to coursework that incorporated training and content specific to developing EBP (although they did not complete individual courses devoted specifically to the topic). For example, during the completion of internship coursework and courses foundational to the counseling profession, they were required to complete assignments focusing on using research and data to inform decision-making and practice. As such, prior to being employed in the field as professional counselors, the participants had prior exposure to the theory and practice of employing EBP.

Mailing addresses of 286 mental health counseling graduates were obtained from the alumni office, and a survey was sent to each graduate. A total of 91 mental health counselors located in a variety of settings, including mental health, school and hospital settings, completed the survey and returned it by mail; a response rate of 31.8% was obtained. Five of the questionnaires were excluded due to the participants not working in the field, and eight questionnaires were excluded due to missing data. An a priori power analysis was conducted to ascertain the number of participants required to achieve statistical significance using G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009). In using an alpha level of .05 and establishing a minimum power set of .80 and moderate effect size of .30, a minimum of 64 participants was needed to obtain a power of .80 in a hypothesis test using bivariate correlations. A minimum sample size of 58 was needed to achieve a power of .80 for our mediation model analysis (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007).

The sample consisted of mostly female (n = 67, 86%) respondents. The participants were primarily White (n = 61, 78%), a small percentage Black (n = 4, 5%) and Hispanic (n = 3, 4%), and the rest identified as being “other” or “mixed-race” (n = 10, 13%). Participants averaged 37.4 years old (SD = 9.4), with a median age of 34.5 years. The participants were experienced, with over 90% having 2 or more years of work experience; 35% (n = 27) had 0–4 years of experience, 37% (n = 29) had 5–7 years of experience, while over 28% (n = 22) had 8 or more years of experience. A majority of participants (n = 65, 83%) reported involvement in a national committee within the mental health profession, indicating that the participants were involved within the counseling community and therefore more likely to be engaged at a professional level. Participants came primarily from mental health agencies (n = 33, 42%), followed by school settings (n = 15, 19%) and hospital settings (n = 7, 9%), with the remaining 27% (n = 20) indicating that they worked in more than one type of setting and approximately 4% (n = 3) not identifying their work setting. Data regarding licensure status was not collected.

Instruments

The Professional Expertise and Work Engagement Survey (PEWES) containing four subscales (Organizational Support of Educational Growth Measure [OSEGM], Organizational Support of Evidence-Based Practice [OSEBP], Utrecht Work Engagement Scale [Utrecht] and Mental Health Counseling Professional Expertise Questionnaire [PES]) was developed to measure professional expertise, organizational support of EBP and educational growth, and work engagement. The survey items were developed through incorporating key literature from counseling and related fields (e.g., business and psychology), since the constructs measured had not been assessed directly in the counseling literature. To ensure that the items were applicable to counseling practices, the survey was developed and piloted by two counselor educators. Items that the counselor educators identified as not applicable to counseling practices were excluded from analysis.

Organizational Support of Educational Growth. This assessment is a 5-item instrument using a 10-point Likert-type scale that evaluates characteristics of work settings. The instrument was designed based on the work of Colquitt et al. (2000) and focuses on attributes that predict motivation to learn and job performance. Cognitive abilities and age (identified as individual factors) along with work environment and trainee feedback from colleagues and supervisors (identified as situational factors) are represented in the model. The scale purports to assess support for educational growth present in the work environment. A few sample items used are the following: (a) To what extent does your work setting provide experiences for professional growth and development? (b) To what extent does your work setting provide time for learning activities to promote your professional growth? (c) To what extent does your organization have a climate that supports learning? A factor analysis was conducted on the items using a principal components extraction method. A single factor solution accounted for 52% of the variance in the items, with an eigenvalue of 2.6, indicating that a single summative scale could be utilized. The scale resulted in a range from 5 (low) to 50 (high). A Cronbach’s alpha of .81, 95% CI [.74, .87], was obtained for this instrument.

Organizational Support of Evidence-Based Practice. This 4-item survey using a 10-point Likert-type scale measures the organization’s culture in terms of supporting employee commitment to EBP. The items were created based on Colquitt and colleagues’ work (2000) and the work of Pfeffer and Sutton (2006). Examples of items used include the following: To what extent do the following statements represent your organizational culture? (a) Committed to evidence-based decision-making, which means being committed to getting the best evidence and using it to guide actions. (b) Looks for the risks and drawbacks in what people recommend—even the best interventions have side effects. A factor analysis with principal components extraction was conducted. Results indicated that a single factor accounted for 66% of the variance in the items, with an eigenvalue of 2.66. The scale resulted in a range of values from 4 (low) to 40 (high). A Cronbach’s alpha of .84, 95% CI [.78, .89], was obtained for this questionnaire.

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. As originally developed, this is a 9-item assessment using a 10-point Likert-type scale that measures level of connection and enthusiasm related to one’s work (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Individuals are evaluated within three aspects of work engagement: vigor, dedication and absorption. The first five items of the scale are utilized to assess work engagement, as follows: (a) At my work, I feel bursting with energy. (b) At my job, I feel strong and vigorous. (c) When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work. (d) I am enthusiastic about my job. (e) I am proud of the work that I do. These five items fall within the first two subscales of vigor and dedication. Given that absorption was not assessed due to clerical error, items were examined to determine whether a single summative scale could be utilized that would define both vigor and dedication at work. A factor analysis using a principal components extraction found a single factor to account for 81% of the variance in the items, with an eigenvalue of 4.06. This total sum scale created a range of values from 5 (low) to 50 (high). The Cronbach’s alpha for this subset of questions in our sample was .95, 95% CI [.93, .96], indicating high reliability. Schaufeli and colleagues (2006) found a reliability between .60 and .88 for the full 9-item scale.

Mental Health Counseling Professional Expertise Questionnaire. Professional expertise was measured by the PES. This self-assessment instrument was designed to measure perceived professional expertise and professional skills. It consists of 10-questions on a 10-point Likert-type scale. Those taking the survey are asked to determine how a strict but fair supervisor would rate their counseling and clinical abilities as related to their work setting. Questions focus on two areas of functioning: ability to select and employ appropriate diagnostic methods, including consideration of cultural data, and ability to implement a treatment plan, based on diagnostic considerations. A few sample items include the following: (a) I am able to select and employ appropriate diagnostic methods. (b) I am able to accurately interpret diagnostic material and make an accurate diagnosis. (c) I am able to develop a comprehensive treatment plan based on my diagnosis. A factor analysis with principal component extraction was conducted to determine whether a single summative scale could be utilized. Our results indicated that a single factor accounted for 63% of the variance in the items, with an eigenvalue of 6.3. A total sum scale was then created and had a range of 10 (low) to 100 (high) points. A Cronbach’s alpha of .92, 95% CI [.89, .94], was obtained for the scale.

Data Analysis

Analyses for hypothesis one were performed by calculating a full correlation matrix for the four variables. The second research question evaluated the hypothesized mediation effect proposed by Bakker and Demerouti (2008) using a path analysis. The alpha level was set to .05 for all statistical analyses. Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 19.0 and SAS Version 9.2.

Results

Hypothesis One

Scores on the OSEGM were positively correlated with the OSEBP Measure, r(76) = .53, p < .001. This positive correlation indicated that high values of organizational support of educational growth were found with high values of organizational support of EBP. In addition, scores on the OSEGM were positively correlated with scores on the Utrecht, r(76) = .55, p < .001. This significant positive relationship indicated that high levels of organizational support of educational growth were found with high scores on the Utrecht. A significant positive correlation also was found between the OSEGM scores and the PES scores, r(76) = .25, p < .03. This positive directional effect indicated that high levels of organizational support of educational growth related to higher scores on professional expertise.

The Utrecht was positively correlated with the OSEBP Measure, r(76) = .58, p < .001. High levels of organizational support of EBP related to higher scores on the Utrecht. The Utrecht was positively correlated with the PES, r(76) = .46, p < .001. The positive relationship indicated that higher scores on the Utrecht found with higher scores on the PES.

Lastly, OSEBP was found to be positively correlated with the PES, r(76) = .33, p = .003. This positive relationship indicated that high levels of organizational support of EBP were found with high scores on the PES. Thus, as hypothesized, organizational support of EBP, organizational support of educational growth and perceived professional expertise were all positively related to each other (see Table 1 for correlations between all major variables.).

Table 1

Correlations Between Study Factors

|

Utrecht |

OSEBP |

OSEGM |

|

| PESOSEGM | .46***.55*** | .33**.53*** | .25* |

| OSEBP | .58*** |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Hypothesis Two

Bakker and Demerouti (2008) proposed a model with a mediation effect of work engagement on the relationship between job and personal resources and performance. Our interpretation of the model placed the OSEGM and the OSEBP Measure into what Bakker and Demerouti (2008) identified as job and personal resources. Additionally, performance was measured by the PES. Work engagement, a mediating variable as suggested by the model, was measured by the Utrecht. Because we adapted the PEWES in accordance with Bakker and Demerouti’s (2008) model, we assessed the individual items and subscales for content validity and reliability as previously described. Given that preliminary findings suggested strong internal consistency, we hypothesized that the full survey could be utilized to ascertain a potential mediation effect of work engagement on the relationship between organizational support of EBP and educational growth, and consequently, greater perceived professional expertise.

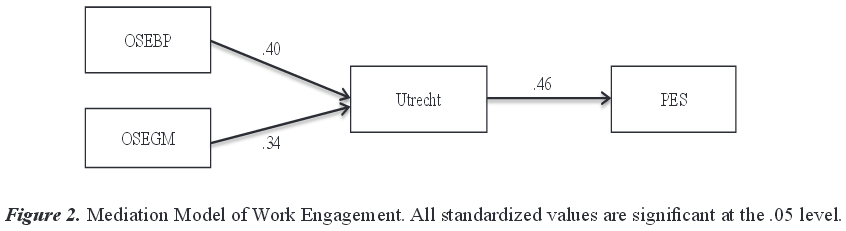

The estimated model, along with the standardized estimates, is shown in Figure 2. The fit of the model was very good, with an RMSEA of 0.00, χ2(2, n = 78) = 0.66, p = .72, GFI = .99, CFI = 1.00. Additionally, 55% of the direct effect between the OSEBP Measure and the PES can be accounted for by the mediation of the Utrecht, and 70% of the direct effect between the OSEGM and the PES can be accounted for by the mediation of the Utrecht. Given the large bivariate relationships between professional expertise and both organizational support of EBP and organizational support of educational growth, it appears that work engagement itself is largely contributing to these positive relationships. This finding is shown by the large percentage of direct effects accounted for by the Utrecht.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain an increased understanding of the relationships between organizational support of EBP and educational growth, work engagement, and perceived counselor professional expertise. In addition, we examined the mediational effect of work engagement on perceived counselor professional expertise. Results revealed a consistent and coherent picture with important implications for organizational support of continued development of counselor professional expertise across a variety of work settings, including mental health agencies, schools and hospital settings.

Significant positive relationships between all variables indicate that counselors who rated themselves higher in professional expertise and perceived their work settings as supportive of EBP and educational growth reported significantly higher work engagement scores. Results affirm the importance of organizational support of EBP and its unique contribution to nurturing and sustaining work engagement levels among counselors. Results also affirm the importance of organizational support of continued counselor educational growth. These findings help to substantiate the research efforts of Bakker and Demerouti (2007, 2008) and Schaufeli and Salanova (2007).

While organizational support of EBP and organizational support of educational growth both were shown to increase professional expertise, it was the amount of work engagement that accounted for a large proportion of the direct relationships between organizational support of EBP and educational growth with professional expertise. This finding suggests that employers can assist in creating environmental conditions that support and promote employee engagement. A commitment to supervision processes that promote the use of EBP and address issues related to the improvement of work engagement can contribute to improvement in counselors’ functioning across a variety of counselor work settings. Supervision that incorporates linkages between and among EBP implementation, work engagement and professional expertise is potentially empowering to respective supervisees.

It is important to note that relying on counselor individual factors exclusively is an insufficient and incomplete path to improving professional expertise outcomes. Results suggest that organizational assessment of work engagement, specifically how it is promoted within the organization, in concert with counselor self-assessments, has the potential to yield meaningful results in terms of creating work environments conducive to professional growth.

Further longitudinal research is needed to corroborate the pathways resulting in increased counselor work engagement and professional expertise. Linkages to client outcomes would have significant implications for the continued assessment and support of professional growth of counselors in the field. Another important contextual consideration, exploration of job demands (e.g., work pressure, emotional demands) and how they inform work engagement, would also be beneficial, with important implications for training, supervision and practice. Because work engagement appears to increase possibilities for influencing positive counselor outcomes across a variety of settings, a promising practice includes increased emphasis on assessment and continued monitoring of counselor work engagement.

Treatment approaches based on evidence-based principles are likely to increase counselors’ confidence levels and expectations for treatment (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). As suggested by the work of Bakker and Demerouti (2008), a positive feedback loop develops between level of work engagement and organizational support of EBP. Our data are incomplete in terms of understanding these critical and complex relationships that suggest mutually reinforcing feedback loops. Future research is needed urgently to understand these linkages, specifically how organizational support of EBP and counselor level of work engagement reinforce each other in the service of improving treatment outcomes. Conducting longitudinal studies would allow more complete understanding of the relationship between organizational support of EBP and counselor work engagement. Such studies would permit careful examination of how these feedback loops unfold and are sustained over time. Furthermore, supervision models that promote systematic understanding of feedback loops can empower supervisees and promote them monitoring and evaluating their professional growth.

In the current study, we did not assess individual attitudes about and commitment to EBP; rather, we assessed participants’ perceptions of organizational commitment to supporting EBP in their respective counseling work settings. We did not explore the unique contributions of supervision models across provider settings and their contributions to perceived professional growth. Consequently, future studies are needed to determine how organizational implementation of EBP, including the use of formal and informal supervision, combined with individual commitment to EBP, is implicated in terms of levels of work engagement and professional expertise.

Organizational support of EBP is likely to thrive in a context in which individuals, as well as the system in which they are embedded, embrace and respect the scientific inquiry process (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006b). While preliminary factors have been identified (e.g., Rapp et al., 2008), further research is needed to investigate this potentially fruitful area of inquiry across culturally diverse work settings, including mental health agencies, schools and hospital settings.

Limitations

This study is characterized by several limitations, in particular, generalizability. All of the participants were graduates of a Master of Science degree program in mental health counseling at an urban northeastern university with a strong commitment to and focus on social justice and serving vulnerable populations. In addition, participants had completed coursework that incorporated assignments focusing on building knowledge and understanding of EBP. Further limiting the generalizability of our findings is that only a select number (31.8%) of graduates from the master’s degree program chose to respond to the questionnaire. The participants were a self-selected group committed to serving clients in urban contexts, and therefore the findings cannot be generalized to all practicing counselors.

Another limitation in our results is the use of a subset of questions designed to assess vigor and dedication on the Utrecht, but that did not assess absorption. However, the questions that were included to assess vigor and dedication yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .95, indicating a very high reliability. A factor analysis revealed that a single factor accounted for 81% of the variance in the items.

The use of self-reports is an additional limitation of the study. Professional expertise and counselor work engagement were assessed by the participants themselves. The study would be enhanced if seasoned external evaluators, deemed experts in their fields, evaluated each of the participants’ level of work engagement and professional expertise. Multiple self-report measurements such as the EBP Attitude Scale (Aarons, 2004) would have provided additional useful information.

This study would be enhanced if variables such as provider demographics, job characteristics and in-depth analyses of supervision services provided were assessed. In addition, using a longitudinal design that incorporated client outcomes and linked them to mental health counselor professional expertise and work engagement would address the limitation of the cross-sectional nature of this design. Nevertheless, given the dearth of research in this unfolding area of study, our findings provide an important contribution in terms of building a foundation for developing a relatively unexplored section of literature as it relates to the counseling profession. Examining the impact of organizational support of EBP and educational growth and level of work engagement has the potential for significantly improving counselor professional expertise over time.

Professional Practice and Supervision Implications

The findings of this study suggest important directions for counselors, counseling supervisors and administrators. The mediation model indicates the strength of work engagement as a mediator of the large positive relationship between organizational support of EBP and counselor professional expertise, and provides a potential powerful lens for improving counselor outcomes. Given that work engagement accounts for a majority of the direct relationship between organizational support of EBP and professional expertise, the findings of this study suggest that assessment of work engagement can be a valuable avenue for increasing professional expertise.

Professionals in counseling and related work settings are struggling with how best to situate their organizations in terms of ensuring optimal counselor and client outcomes, particularly in a context of diminishing economic resources. Although, for example, research studies have provided a degree of clarity in terms of identifying strategies that promote positive attitudes on the part of counselors toward implementation of EBP (Rapp et al., 2008), the systematic study of counselor work engagement and its contribution to professional expertise has not received the attention and focus it merits. While traditional models of counselor training have focused on counselor deficiencies, our finding in support of the mediational role of work engagement expands the understanding of professional growth from a positive psychology perspective—the positive aspects of work.

The dynamic nature of the mediational model proposed in this study provides important opportunities for supervision and administrative practices. In accordance with the model proposed by Bakker and Demerouti (2008), relationships between resources, such as organizational support of EBP and continuing organizational support of education; work engagement; and counselor professional expertise are neither static nor unidirectional. These variables mutually reinforce and inform each other. Based on the model suggested by Salanova et al. (2005), organizational support of EBP and organizational support of educational growth serve as job resources that increase work engagement levels among counselors; they also inform counselor professional expertise. Sensitizing counselors and supervisors who function across a variety of settings, including schools, hospitals and mental health agencies, to the significance of work engagement, its linkage to EBP and the opportunities it provides for self-assessment can increase possibilities for improving counselor professional expertise (Crocket, 2007). To date, there is no study that suggests how these important linkages—organizational support of EBP and education, work engagement, and professional expertise—can best be harnessed and translated to a variety of settings and improved outcomes with respect to counselor professional expertise (as well as improved client counseling outcomes). Comparison studies are needed to determine optimal models and how they may be adapted and individualized across a variety of sociocultural settings in order to reinforce the dynamic interplay of these important constructs.

Supervisors of mental health counselors have an important role in helping counselors understand organizational contexts, and how they may influence and support their professional growth. Crocket (2007) found that a counselor’s workplace and professional culture, including what transpires during supervision discussions, influence the counselor’s development. Supervisors also play a role in deciphering organizational contexts and can be instrumental in supporting supervisees’ job satisfaction and work motivation (Sears et al., 2006). It is important to understand one’s work context and the potential impact of organizational and professional values on one’s own professional development, a stance that helps counselors to engage actively in the process of self-assessment (Crocket, 2007). Finally, the linkage of organizational commitment to EBP and counselor engagement to continuing professional expertise offers promising opportunities for reflection and professional growth. There is developing evidence that support for professional growth in general facilitates the successful implementation of EBP (Rapp et al., 2008). When there is consistent supportive supervision for using EBP, and when all staff members are included in the education on EBP and demonstration of its importance, even those personnel who are not targeted for EBP implementation, more successful outcomes of EBP implementation have been reported (Rapp et al., 2008). Further, Carlson et al. (2012) reported that successful implementation of EBP is supported by implementation of professional development and skill building as supervisory activities. Not only does our model provide support for the implementation of EBP in counseling settings, but it also provides support for implementation of interventions that enhance professional growth. In keeping with the findings of Colquitt et al. (2000), our model suggests that organizational support contributes to work engagement, independent of support of EBP. Furthermore, Witteman, Weiss, and Metzmacher (2012), based on the work of Gaines (1988), suggested that the development and refinement of professional expertise depend on consistent positive feedback processes. Organizational support of EBP provides counselors and administrators with data-driven feedback processes that encourage opportunities for focused collaboration with room for reflection, evaluation and refinement.

Conclusion

Our robust findings suggest a potentially fruitful area of inquiry that is relatively unexplored terrain. Given that implementation of EBP requires both well-conceived research and practitioners to interpret that research, it would be helpful to isolate and understand the variables that promote successful implementation of EBP in terms of counselor level of work engagement and counselor professional expertise. In the present study, a mediational model that considered systemic factors yielded fruitful findings that have significant implications for counselors, supervisors and administrators working in mental health, school and hospital settings.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

Aarons, G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6, 61–74. doi:10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65

Aarons, G. A., & Palinkas, L. A. (2007). Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: Service provider perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34, 411–419. doi:10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3

Aarons, G. A., & Sawitzky, A. C. (2006a). Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33, 289–301. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0039-1

Aarons, G. A., & Sawitzky, A. C. (2006b). Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychological Services, 3, 61–72. doi:10.1037/1541-1559.3.1.61

Aarons, G. A., Sommerfeld, D. H., Hecht, D. B., Silovsky, J. F., & Chaffin, M. J. (2009). The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: Evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 270–80. doi:10.1037/a0013223

Auger, R.W. (2004). What we don’t know CAN hurt us: Mental health counselors’ implicit assumptions about human nature. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 26, 13–24.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13, 209–223. doi:10.1108/13620430810870476

Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 274–284. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274

Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 1–30. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x

Bradley, L. J., Sexton, T. L., & Smith, H. B. (2005). The American Counseling Association Practice Research Network (ACA-PRN): A new research tool. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 488–491. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00370.x

Brown, D., Pryzwansky, W. B., & Schulte, A. C. (2006). Psychological consultation and collaboration: Introduction to theory and practice (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Bultsma, S. A. (2012). Supervision experiences of new professional school counselors. Michigan Journal of Counseling: Research, Theory, and Practice, 39, 4–18.

Campbell, J. C., & Christopher, J. C. (2012). Teaching mindfulness to create effective counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34, 213–226.

Carey, J., & Dimmitt, C. (2008). A model for evidence-based elementary school counseling: Using school data, research, and evaluation to enhance practice. The Elementary School Journal, 108, 422–430. doi:10.1086/589471

Carlson, L., Rapp, C. A., & Eichler, M. S. (2012). The experts rate: Supervisory behaviors that impact the implementation of evidence-based practices. Community Mental Health Journal, 48, 179–186. doi:10.1007/s10597-010-9367-4

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 678–707. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.85.5.678

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2009). 2009 standards. Alexandria, VA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/2009-Standards.pdf

Crocket, K. (2007). Counselling supervision and the production of professional selves. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 7, 19–25. doi:10.1080/14733140601140402

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.499

Dimmitt, C., Carey, J. C., & Hatch, T. (2007). Evidence-based school counseling: Making a difference with data-driven practices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Forman, S. G., Shapiro, E. S., Codding, R. S., Gonzales, J. E, Reddy, L. A., Rosenfield, S. A., . . . Stoiber, K. C. (2013). Implementation science and school psychology. School Psychology Quarterly, 28, 77–100. doi:10.1037/spq000001910

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18, 233–239. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

Gaines, B. R. (1988). Positive feedback processes underlying the formation of expertise. IEEEE Transactions on Systems, Man & Cybernetics, 18, 1016–1020. doi:10.1109/21.23101

Goh, M. (2005). Cultural competence and master therapists: An inextricable relationship. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 27, 71–81.

Goodman, R. L., & Amatea, E. S. (1994). The impact of trainee characteristics on the family therapy skill acquisition of novice therapists. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 16, 483–497.

Hakanen, J. J., Perhoniemi, R., & Toppinen-Tanner, S. (2008). Positive gain spirals at work: From job resources to work engagement, personal initiative and work-unit innovativeness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 78–91. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.003

Jennings, L., Sovereign, A., Bottorff, N., Mussell, M. P., & Vye, C. (2005). Nine ethical values of master therapists. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 27, 32–47.

Langelaan, S., Bakker, A. B., van Doornen, L. J. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement: Do individual differences make a difference? Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 521–532. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.009

McLaughlin, A. M., Rothery, M.,, Babins-Wagner, R., & Schleifer, B. (2010). Decision-making and evidence in direct practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, 38, 155–163. doi:10.1007/s10615-009-0190-8

McLeod, J. (1999). A narrative social constructionist approach to therapeutic empathy. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 12, 377–394. doi:10.1080/09515079908254107

Meier, S. T. (1999). Training the practitioner-scientist: Bridging case conceptualization, assessment, and intervention. The Counseling Psychologist, 27, 846–869. doi:10.1177/0011000099276008

Morkides, C. (2009, July). Measuring counselor success. Counseling Today. Retrieved from http://ct.counseling.org/2009/07/measuring-counselor-success/

Neufeldt, S. A., Karno, M. P, & Nelson, M. L. (1996). A qualitative study of experts’ conceptualizations of supervisee reflectivity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 3–9. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.43.1.3

Perera-Diltz, D. M., & Mason, K. L. (2012). A national survey of school counselor supervision practices: Administrative, clinical, peer, and technology mediated supervision. Journal of School Counseling, 10(4), 1–34. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ978860.pdf

Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. I. (2006). Evidence-based management. Harvard Business Review, 84, 62–74.

Pope, V. T., & Kline, W. B. (1999). The personal characteristics of effective counselors: What 10 experts think. Psychological Reports, 84, 1339–1344. doi:10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3c.1339

Rapp, C. A., Etzel-Wise, D., Marty, D., Coffman, M., Carlson, L., Asher, D., . . . Whitley, R. (2008). Evidence-based practice implementation strategies: Results of a qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, 44, 213–224. doi:10.1007/s10597-007-9109-4

Richards, K. C., Campenni, C. E., & Muse-Burke, J. L. (2010). Self-care and well-being in mental health professionals: The mediating effects of self-awareness and mindfulness. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 32, 247–264.

Salanova, M., Agut, S., & Pieró, J. M. (2005). Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1217–1227. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1217

Salanova, M., Bakker, A. B., & Llorens, S. (2006). Flow at work: Evidence for an upward spiral of personal and organizational resources. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-8854-8

Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behavior. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19, 116–131. doi:10.1080/09585190701763982

Schaufeli, W., & Bakker, A. (2003). UWES: Utrecht work engagement scale preliminary manual [Version 1, November 2003]. Utrecht University: Occupational Health Psychology Unit. Retrieved from http://www.beanmanaged.com/doc/pdf/arnoldbakker/articles/articles_arnold_bakker_87.pdf

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 293–315. doi:10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701–716. doi:10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2007). Work engagement: An emerging psychological concept and its implications for organizations. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Series Eds)., Research in social issues in management: Vol. 5. Managing social and ethical issues in organizations (pp. 135–177). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 173–203. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00285.x

Sears, R., Rudisill, J., & Mason-Sears, C. (2006). Consultation skills for mental health professionals. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Skovholt, T., & Jennings, L. (2005). Mastery and expertise in counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 27, 13–18.

Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 518–528. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518

Spengler, P. M., White, M. J., Ægisdóttir, S., Maugherman, A. S., Anderson, L. A., Cook, R. S., . . . Rush, J. D. (2009). The meta-analysis of clinical judgment project: Effects of experience on judgment accuracy. The Counseling Psychologist, 37, 350–399. doi:10.1177/0011000006295149

Tarvydas, V., Addy, A., & Fleming, A. (2010). Reconciling evidenced-based [sic] research practice with rehabilitation philosophy, ethics, and practice: From dichotomy to dialectic. Rehabilitation Education, 24, 191–204. doi:10.1891/088970110805029831

Truscott, S. D., Kreskey, D., Bolling, M., Psimas, L., Graybill, E., Albritton, K., & Schwartz, A. (2012). Creating consultee change: A theory-based approach to learning and behavioral change processes in school-based consultation. Consultation Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 64, 63–82. doi:10.1037/a0027997

Witteman, C. L. M., Weiss, D. J., & Metzmacher, M. (2012). Assessing diagnostic expertise of counselors using the Cochran–Weiss–Shanteau (CWS) index. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 30–34. doi:10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00005.x

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 235–244. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.003

Varda Konstam is a professor emerita at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. Sara Tomek is an assistant professor and the director of the Research Assistance Center at the University of Alabama. Amy L. Cook is an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. Esmaeil Mahdavi is a professor at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. Robert Gracia is an instructor at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. Alexander H. Bayne is a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. Correspondence can be addressed to Varda Konstam, Department of Counseling and School Psychology, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2 Avery Street, Boston, MA 02111, vkonstam@gmail.com.