Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Dalena Dillman Taylor, Saundra M. Tabet, Megan A. Whitbeck, Ryan G. Carlson, Sejal Barden, Nicole Silverio

Individuals living in poverty have higher rates of mental health disorders compared to those not living in poverty. Measures are available to assess adults’ levels of psychological distress; however, there is limited support for instruments to be used with a diverse population. The purpose of our study was to examine the factor structure of Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 scores with an economically vulnerable sample of adults (N = 615), contributing to the evidence of validity of the measure’s scores in diverse mental health settings. Implications for professional counselors are considered, including clinical usage of the brief Outcome Questionnaire-16 and key critical items.

Keywords: poverty, psychological distress, factor structure, Outcome Questionnaire-45.2, validity

In the United States, it is estimated that 34 million adults live in poverty (i.e., income less than $12,880 per year), and poverty is a significant factor contributing to poor mental and physical health outcomes (Hodgkinson et al., 2017). Poverty, or economic vulnerability, refers to the extent to which individuals have difficulty living with their current level of income, increasing the risk for adverse social and economic consequences (Semega et al., 2021). Economically vulnerable adults often experience greater social inequality, lower educational attainment, less economic mobility (Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2015), and difficulty securing full-time employment (Dakin & Wampler, 2008), which leads to increased distress (Lam et al., 2019). Lower income levels are also associated with several mental health conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression, suicide attempts; Santiago et al., 2011). Further, Lam and colleagues (2019) found strong negative associations between income, socioeconomic status, and psychological distress.

To effectively support their clients, counselors must understand the unique context and financial stressors related to living in poverty. Incorporating poverty-sensitive measures into assessment and evaluation practices is essential to providing culturally responsive care that considers the systemic and environmental barriers of poverty (Clark et al., 2020). Implementing culturally responsive assessments ensures that counselors use outcome measures that are attuned to poverty-related experiences (Clark et al., 2020). Such measures can help counselors identify and prioritize treatment planning approaches and acknowledge the reality that economic disadvantages create for clients (Foss-Kelly et al., 2017). However, the availability of poverty-sensitive assessments is limited.

Measuring Psychological Distress in Adults Living in Poverty

Because of the risk of mental health issues related to economic vulnerability, assessments with evidence of validity and reliability that measure psychological distress relative to income are warranted. Professional counselors can individualize their therapeutic approach to meet the needs of this population with the assistance of accurate assessments of related mental health conditions. Naher and colleagues (2020) noted the need for individual-level data as well as interventions specifically targeted to adults living in poverty. Although outcome assessments exist to measure psychological distress or severity of mental illness symptoms (e.g., Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], Beck et al., 1961; Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener [GAD-7], Löwe et al., 2008; Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9], Kroenke et al., 2001), there is a lack of measures with evidence of validity and reliability with economically vulnerable adult populations. Therefore, our investigation examined the factor structure of the Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 (OQ-45.2; Lambert et al., 2004) with an economically vulnerable adult population, increasing the applicability of the measure in mental health settings.

Outcome Questionnaire-45.2

The OQ-45.2 (Lambert et al., 2004) is one of the most widely used outcome measures of psychological distress in applied mental health settings (Hatfield & Ogles, 2004). The OQ-45.2 assists professional counselors with monitoring client progress and can be administered multiple times throughout treatment, as it is sensitive to changes over time (Lambert et al., 1996). The OQ-45.2 has been implemented in outcome-based research with diverse populations such as university counseling center clients (Tabet et al., 2019), low-income couples (Carlson et al., 2017), and ethnic minority groups (Lambert et al., 2006). Lambert et al. (1996) reported strong test-retest reliability (r = .84) and internal consistency (α = .93) for the OQ-45.2, based on a sample of undergraduate students (n = 157) and a sample of individuals receiving Employee Assistance Program services (n = 289). However, researchers have yet to investigate the psychometric properties of the OQ-45.2 with an economically disadvantaged, diverse population.

Given the utility of the OQ-45.2 as a client-reported feedback measure, clinicians can use the OQ-45.2 in a variety of ways to evaluate client progress, including measuring changes in individual distress across the course of counseling and before and after specific treatment interventions, as well as to glean a baseline level of distress at the start of counseling (Lambert, 2017). For example, one study used the OQ-45.2 as a primary outcome measure for anxiety symptoms in clients engaging in cognitive behavioral therapy (Levy et al., 2020). The OQ-45.2 was administered at the beginning of each weekly counseling session and change scores were calculated between each session, which helped clinicians understand that about half of their sample reported clinically significant reductions in symptoms in just nine sessions (Levy et al., 2020). This example demonstrates how the OQ-45.2 can be implemented to monitor treatment outcomes and improve the duration and efficiency of counseling. A clinician can also use salient items as part of the intake clinical interview to encourage clients to elaborate on the specific symptoms they are experiencing, and how they may be impacting their functioning, across a variety of clinical settings (Espiridion et al., 2021; Lambert, 2017; Levy et al., 2020).

Factor Structure of OQ-45.2

Researchers contested the factor structure proposed by Lambert et al. (2004), suggesting the need for further validation of the three-factor oblique measurement model and exploration of other possible factor structures (e.g., Kim et al., 2010; Mueller et al., 1998; Rice et al., 2014; Tabet et al., 2019). Mueller and colleagues (1998) examined three models: (a) a one-factor model, (b) a two-factor oblique model, and (c) a three-factor oblique model, none of which fit the data well. In addition, the factors in the three-factor model were highly correlated, ranging from .83 to .91, asserting that the subscales may not be statistically indistinguishable and the OQ-45.2 might be a unidimensional measure of global distress.

Kim and colleagues (2010) also explored three models to assess adequate fit of the data: (a) a one-factor model, (b) a three-factor model, and (c) a revised 22-item four-factor model. Indicating weak support for the OQ-45.2’s factorial validity across all models, researchers cautioned against widespread utilization in mental health and research settings, encouraging further psychometric exploration and validation of the OQ-45.2 (Kim et al., 2010).

Rice and colleagues (2014) found evidence to support a two-factor OQ-45.2 model that included (a) overall maladjustment and (b) substance use. Results indicated relatively good fit (comparative fit index [CFI] = .990, root-mean-square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .068) for a two-factor measure with 11 items, which demonstrated better model fit than the original three-factor model

(CFI = .840, RMSEA = .086 [90% confidence interval {CI} = .085, .087]). Overall, multiple researchers have demonstrated poor fit for the original factor structure of the OQ-45.2 (Kim et al., 2010; Mueller et al., 1998; Rice et al., 2014; Tabet et al., 2019), supporting the need for further validation for using the OQ-45.2 with samples of adults living in poverty.

This study’s primary aim is to examine the factor structure of the OQ-45.2 with an economically vulnerable sample to enhance the generalizability of the OQ-45.2 in mental health settings. Therefore, the following research questions guided our study:

RQ1. What is the factor structure of OQ-45.2 scores with a sample of adults living in poverty?

RQ2. What is the internal consistency reliability of the abbreviated 16-item OQ-45.2 scores with a sample of adults living in poverty?

RQ3. What is the test-retest reliability of the abbreviated 16-item OQ-45.2 scores with a sample of adults living in poverty?

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants comprised a sub-sample from a grant-funded, community-based, relationship education program for individuals and couples at a university in the Southeastern United States. The project was funded through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Family Assistance (Grant #90FM0078). Study recruitment strategically involved passive and active recruitment strategies (Carlson et al., 2014) from various community locations that primarily serve low-income individuals and families (e.g., libraries, employment offices). Participants met inclusion criteria if they were at least 18 years old and interested in learning about healthy relationships. The relationship education intervention utilized was an evidence-based curriculum that taught individuals tools to improve their relationships in a small group setting (Prevention and Relationship Education Program [PREP]; Pearson et al., 2015).

We obtained ethical approval from the university’s IRB prior to data collection. Each person participated in a group intake session that consisted of a review of the informed consent; a battery of assessments, including the OQ-45.2; and a brief activity. Study participants (N = 615) included in this current analysis consented between July 2015 and June 2019.

Demographic Information

We collected demographic data as part of this study, which included gender, age, ethnicity, income, educational level, working status, and marital status (see Table 1). The majority of participants fell below the poverty line when factoring in number of children and/or under- or unemployment. Therefore, our sample consisted of a diverse population, including variations in income, age, ethnicity, and race.

Table 1

Participant Demographic Characteristics

Descriptive Characteristic Total Sample (n, %)

| Age

18–20 years

21–24 years

25–34 years

35–44 years

45–54 years

55–64 years

65 years or older |

34 (5.5)

52 (8.5)

130 (21.1)

139 (22.6)

137 (22.3)

91 (14.8)

32 (5.2) |

| Gender (female) |

498 (81.0) |

| Race |

|

| American Indian or Alaska Native |

18 (2.9) |

| Asian |

19 (3.1) |

| Black or African American |

176 (28.6) |

| Native American or Pacific Islander |

2 (0.3) |

| White |

248 (40.3) |

| Other |

144 (23.4) |

| Ethnicity

Hispanic or Latino

Not Hispanic or Latino

Income |

258 (42.0)

356 (57.9) |

| Less than $500 |

216 (35.1) |

| $501–$1,000 |

108 (17.6) |

| $1,001–$2,000

$2,001–3,000

$3,001–$4,000

$4,001–$5,000

More than $5,000 |

124 (20.2)

81 (13.2)

28 (4.6)

18 (2.9)

18 (2.9) |

| Educational Level

No degree or diploma earned

High school diploma

Some college but no degree completion

Associate degree

Bachelor’s degree

Master’s / advanced degree |

24 (3.9)

18 (2.9)

75 (12.2)

66 (10.7)

134 (21.8)

77 (12.5) |

| Marital Status

Married

Engaged

Divorced

Widowed

Never Married |

93 (15.1)

11 (1.8)

164 (26.7)

24 (3.9)

270 (43.9) |

| Employment Status

Full-time employment

Part-time employment

Temporary, occasional, or seasonal, or odd jobs for pay

Not currently employed

Employed, but number of hours change from week to week

Selected multiple responses

Number of Children

0

1

2

3

4

5

6 |

227 (36.9)

83 (13.5)

41 (6.7)

207 (33.7)

29 (13.5)

6 (1.0)

148 (24.1)

60 (9.8)

44 (7.2)

17 (2.8)

6 (1.0)

4 (0.7)

1 (0.4) |

Instrument

The Outcome Questionnaire-45.2

The OQ-45.2 is a self-report questionnaire that captures individuals’ subjective functionality in various aspects of life that can lead to common mental health concerns (e.g., anxiety, depression, substance use). The current three-factor structure of the OQ-45.2 has 45 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with rankings of 0 (never), 1 (rarely), 2 (sometimes), 3 (frequently), and 4 (almost always; Lambert et al., 2004). Nine OQ-45.2 items are reverse scored, with total OQ-45.2 scores calculated by summing all 45 items with a range from 0 to 180. Clinically significant changes are represented in a change score of at least 14, whether positive or negative (i.e., increased or reduced distress).

The Symptom Distress subscale (25 items) evaluates anxiety, depression, and substance abuse symptoms, as these are the most diagnosed mental health concerns (Lambert et al., 1996). The Interpersonal Relations subscale (11 items) includes items that measure difficulties and satisfaction in relationships. The Social Role Performance subscale (nine items) assesses conflict, distress, and inadequacy related to employment, family roles, and leisure activities. The OQ-45.2 also includes four critical items (Items 8, 11, 32, and 44) targeting suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, and substance use. The Cronbach’s alpha for the OQ-45.2 in the current study was calculated at .943.

Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics on the total sample population, including the mean, standard deviations, and frequencies. Subsequently, we conducted preliminary descriptive analyses to test for statistical assumptions that included missing data, collinearity issues, and multivariate normality (Byrne, 2016). In the first analysis, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the factor structure of the OQ-45.2 with this population (N = 615) and subsequently used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to evaluate revised OQ models.

We conducted CFA utilizing the original three-factor oblique model (Lambert et al., 2004) as the a priori model to test the hypothesized structure of the latent variables. In addition, based on the results of the study, we tested a series of alternative structural models outlined by Bludworth and colleagues (2010). Given the non-normal distribution, we utilized MPlus (Version 8.4) with a robust maximum likelihood (MLR) parameter estimation (Satorra & Bentler, 1994). To address missing data, we employed a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to approximate the population parameters and produce the estimates from the sample data (Enders, 2010). Results of the CFA were evaluated using several fit indices: (a) the chi-square test of model fit (χ2; nonsignificance at p > .05 indicate a good fit [Hu & Bentler, 1999]); (b) the CFI (values larger than .95 indicate a good fit [Bentler, 1990]); (c) TLI (values larger than .95 indicate a good fit [Tucker & Lewis, 1973]); (d) RMSEA with 90% CI (values between .05 and .08 indicate a good fit [Browne & Cudeck, 1993]); and (e) standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; values below .08 indicate good fit [Hu & Bentler, 1999]).

Following the CFA, we conducted EFA because of poor model fit across all models and several items with outer loadings of less than 0.5 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Kline (2016) recommended researchers should not be constrained by the original factor structure when CFA indicates low outer loadings and should consider conducting an EFA because the data may not fit the original number of factors suggested. Accordingly, we conducted an EFA to test the number of factors derived from the 45-item OQ-45.2 within our population. We exceeded the recommended ratio (i.e., 10:1) of participants to the number of items (12.6:1; Costello & Osborne, 2005; Hair et al., 2010; Mvududu & Sink, 2013). We conducted a principal axis factoring with Promax rotation to determine whether factors were correlated using SPSS version 25.0. We chose parallel analysis (Horn, 1965) using the 95th percentile to determine the number of factors to retain given that previous researchers have acknowledged parallel analysis to be a superior method to extract significant factors as compared to conventional statistical indices such as Cattell’s scree test (Henson & Roberts, 2006). We used stringent criterion when identifying loading and cross-loading items such as items that indicated high (i.e., equal to or exceeding 1.00) or low communality values (i.e., less than 0.40; Costello & Osborne, 2005) and items with substantive cross-loadings (< .30 between two factor loadings; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019) were removed. To ensure the most parsimonious model, we removed items individually from Factor 1, which has the greatest number of items, to reduce the size of the model while still capturing the greatest variance explained by the items on that factor.

Results

We screened the data and checked for statistical assumptions prior to conducting factor analysis. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test (Little, 1988), a multivariate extension of a simple t-test, evaluated the mean differences of the 45 items to determine the pattern and missingness of data (Enders, 2010). Given the significant chi-square, data were not missing completely at random

(χ2 = 912.062, df = 769, p < .001). However, results indicated a very small percentage of values (< 1%) were missing from each variable; therefore, supporting data were missing at random (MAR; Osborne, 2013). When data are MAR, an FIML approach to replace missing values provides unbiased parameter estimates and improves the statistical power of analyses (Enders, 2010). The initial internal consistency reliability estimates (coefficient alpha) for scores on the original OQ-45.2 model were all in acceptable ranges except for Factor 3 (see Henson & Roberts, 2006): total α = .943, Symptom Distress α = .932

(k = 25 items), Interpersonal Relations α = .802 (k = 11 items), and Social Role Performance α = .683

(k = 9 items). We also conducted Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < .001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value (.950), indicating the data was suitable for conducting a factor analysis. We evaluated multivariate normality of the dataset with Mardia’s multivariate kurtosis coefficient. Mardia’s coefficient of multivariate kurtosis was .458; therefore, we deemed the data to be non-normally distributed

(Hu & Bentler, 1995).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We tested the developer’s original OQ-45.2 three-factor oblique model, and because of the results subsequently tested a series of alternative structural models outlined by Bludworth and colleagues (2010). Specifically, the alternative structural models tested included: (a) a three-factor orthogonal model, (b) a one-factor model, (c) a four-factor hierarchical model, and (d) a four-factor bilevel model. Table 2 presents the fit indices results in the series of CFAs. The original three-factor oblique model allowed all three factors (Social Role Performance, Interpersonal Relations, and Symptom Distress) to correlate, but resulted in a poor fit: χ2 (942, N = 615) = 3.014, p < .001; CFI = .779; TLI = .768; RMSEA = .057, 90% CI [.055, .060]; SRMR = .063. We next uncorrelated the factors and tested a three-factor orthogonal model, which also presented a poor fit with worsened fit metrics: χ2 (945, N = 615) = 3.825, p < .001; CFI = .689; TLI = .674; RMSEA = .068, 90% CI [.065, .070]; SRMR = .202. Accordingly, because the factors demonstrated high intercorrelation (rs = .94, .93, .91) in the three-factor oblique model and lack of factorial validity based on the CFA results of both three-factor models, we suspected the OQ-45.2 to be a unidimensional, one-factor model. However, the CFA revealed a poor fit to the OQ-45.2 one-factor model: χ2 (945, N = 615) = 3.197,

p < .001; CFI = .758; TLI = .747; RMSEA = .060, 90% CI [.057, .062]; SRMR = .062.

Table 2

Goodness-of-Fit Indices for the Item-Level Models of the OQ-45.2

|

χ2 |

df |

p |

χ2/df |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA |

90% CI |

SRMR |

| One-Factor |

3021.300 |

945 |

.000 |

3.197 |

.758 |

.747 |

.060 |

[.057, .062] |

.062 |

| Three-Factor (orthogonal) |

3615.060 |

945 |

.000 |

3.825 |

.689 |

.674 |

.068 |

[.065, .070] |

.202 |

| Three-Factor (oblique) |

2839.335 |

942 |

.000 |

3.014 |

.779 |

.768 |

.057 |

[.055, .060] |

.063 |

| Four-Factor (hierarchical) |

2839.335 |

942 |

.000 |

3.014 |

.779 |

.768 |

.057 |

[.055, .060] |

.063 |

| Four-Factor

(bilevel) |

2363.263 |

900 |

.000 |

2.626 |

.829 |

.812 |

.051 |

[.049, .054] |

.054 |

Note. N = 615. χ2 = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; χ2/df = relative chi-square; CFI = comparative fit index;

TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; 90% CI = 90% confidence interval;

SRMR = standardized root-mean-square residual.

We proceeded to test the OQ-45.2 as a four-factor hierarchical model. In this multidimensional model, the three first-order factors (Social Role Performance, Interpersonal Relations, and Symptom Distress) became a linear combination to sum a second-order general factor (g-factor) of Psychological Distress (Eid et al., 2017). Results evidenced an unacceptable overall fit to the data: χ2 (942, N = 615) = 3.014, p < .001; CFI = .779; TLI = .768; RMSEA = .057, 90% CI [.055, .060]; SRMR = .063. Last, we examined a four-factor bilevel model. In this model, the g-factor of Psychological Distress has a direct effect on items, whereas, in the hierarchal model, it had an indirect effect on items. Therefore, the items in the four-factor bilevel model load onto both their intended factors (Social Role Performance, Interpersonal Relations, and Symptom Distress) and the g-factor (Psychological Distress). Nevertheless, although the four-factor bilevel was cumulatively the best fitting OQ-45.2 factorial model, the results still yielded a poor fit:

χ2 (900, N = 615) = 2.626, p < .001; CFI = .829; TLI = .812; RMSEA = .051, 90% CI [.049, .054]; SRMR = .054.

Overall, all models demonstrated a significant chi-square (p < .001); however, this result is common in larger sample sizes (N > 400; Kline, 2016). Because the chi-square statistic is sensitive to sample size and model complexity, researchers have recommended using other fit indices (e.g., RMSEA, CFI) to determine overall model fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Nevertheless, the levels of the CFI values (ranging from .689 to .829) and TLI values (ranging from .674 to .812) were low, and far below the recommended referential cutoff (> .90; Tucker & Lewis, 1973). Although the models’ RMSEA values were within the recommended range of .05 to .08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and the majority of SRMR values were below .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), these were the only fit indices that met acceptable cutoffs. We further examined outer loadings for the 45 items within the factorial models and identified that all models had outer loadings (ranging from 5 to 14 items) below the 0.5 cutoff (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). When CFA produces low factor loadings and poor fit indices, researchers should not be constrained to the original specified number of factors and should consider conducting an EFA (Kline, 2016). Hence, we elected to conduct an EFA to explore the factor structure with this population.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Results from the initial EFA using principal axis factoring with the 45 OQ items produced a solution that explained 55.564% of the total variance. After multiple iterations of item deletions, we concluded with a three-factor solution. We present the internal reliability estimates of two three-factor solutions: (a) a 16-item three-factor solution—the most parsimonious—and (b) an 18-item three-factor solution, including all critical items in Table 3. We present the first three-factor solution because it was derived using stringent criteria for creating the most parsimonious solution (Costello & Osborne, 2005; Henson & Roberts, 2006; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019), whereas the second three-factor solution included conceptual judgment determining the inclusion of the critical items from the original OQ-45.2.

Table 3

Internal Consistency Estimates

|

Total |

Symptom Distress |

Interpersonal Relations |

Social Role Performance |

| Original OQ-45 |

.943 |

.932 |

.802 |

.683 |

|

Total |

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

| 16-Item Model |

.894 |

.864 |

.840 |

.710 |

| 18-Item Model |

.896 |

.857 |

.840 |

.700 |

Three-Factor Solution

Results from the parallel analysis (Horn, 1965) indicated an initial four-factor solution. Through multiple iterations (n = 9) of examining factor loadings, removing items one at a time, and reexamining parallel analysis after each deletion, our results demonstrated that a three-factor solution was the most parsimonious. We removed a total of 29 items because of low communalities (< .5), low factor loadings (< .4), and substantive cross-loadings (> .3 between two factor loadings; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Before accepting the removal of these items, we added each back to the model to determine its impact on the overall model. No items improved the model; therefore, we accepted the deletion of the 29 items. The final three-factor solution included 16 items with 57.99% of total variance explained, which indicates near acceptable variance in social science research, with 60% being acceptable (Hair et al., 2010). Factor 1 (seven items) explained 38.98% of the total variance; Factor 2 (six items) explained 11.37% of the total variance; and Factor 3 (three items) explained 7.64% of the total variance.

Three-Factor Solution With Critical Items

After finalizing the model, we added Item 8 (“I have thoughts of ending my life”) and Item 44 (“I feel angry enough at work/school to do something I might regret”) into the final model for purposes of clinical utility. Both items resulted in low factor loading (< .4). Item 8 correlated with other items on Factor 3, and Item 44 correlated with other items on Factor 1. This final 18-item three-factor solution reduced the variance explained by the items on the factors by 3.45%, indicating a questionable fit for social sciences (54.54%; Hair et al., 2010). Factor 1 (eight items) explained 36.83% of the total variance; Factor 2 (six items) explained 10.82% of the total variance; and Factor 3 (four items) explained 6.90% of the total variance. Internal consistency estimates are presented in Table 3 for all three models: (a) the original OQ-45.2 (α = .943); (b) the 16-item, three-factor solution (α = .894); and (c) the 18-item, three-factor solution (α = .896).

Test-Retest Reliability

To examine the stability of the new 16-item OQ scores over time, we assessed test-retest reliability over a 30-day interval using bivariate correlation (Pallant, 2016). Results yielded strong correlation coefficients between pre-OQ scores and post-OQ scores: (a) OQ Total Scores, r = .781, p < .001; (b) Factor 1, r = .782, p < .001; (c) Factor 2, r = .742, p < .001; and (d) Factor 3, r = .681, p < .001. The 18-item OQ scores also demonstrated significant support for test-retest reliability over a 30-day interval: (a) OQ Total Scores, r = .721, p < .001; (b) Factor 1, r = .658, p < .001; (c) Factor 2, r = .712, p < .001; and (d) Factor 3, r = .682, p < .001.

Discussion

We found that the current factor structure of the OQ-45.2 poorly fits the sample population of economically vulnerable individuals. Our preliminary results support Rice and colleagues’ (2014) claim: because of the unique stressors economically vulnerable individuals face, the OQ-45.2 does not adequately capture their psychological distress. The lack of support for the OQ-45.2’s current structure (i.e., three-factor oblique) creates doubt clinically when assessing clients’ distress. Therefore, we explored alternative structural models proposed by Bludworth and colleagues (2010) using a CFA, and subsequently an EFA, to reexamine the factor structure of the OQ-45.2.

The EFA resulted in a 16-item, three-factor solution with our sample, indicating marginal support for the validity and reliability of the items for this brief model of the OQ, meaning that this model lacked reliability (i.e., ability to produce similar results consistently) and validity (i.e., ability to actually measure what it intends to measure: distress). In social science research, total variance explained of 60% is adequate (Hair et al., 2010); therefore, the three-factor model that approaches 60% could be acceptable, indicating that this model captures more than half or more than chance of the construct distress for this population. Still, additional research is needed to support the factor structure with a similar population of low-income, diverse individuals. Economically vulnerable individuals experience unique stressors (Karney & Bradbury, 2005), and brief assessments are best practices (Beidas et al., 2015). Therefore, we encourage other researchers to reexamine the use of this brief version of the OQ with a sample of economically vulnerable individuals or develop a new instrument that may more accurately capture psychological distress in economically disadvantaged individuals.

Also, the 16-item model results differ from the original OQ-45.2 in that we were unable to find support for the social role factor with our sample population. We hypothesize this finding is largely due to the economic stressors this population faces (e.g., unreliable transportation, food scarcity, housing needs). Anecdotally, some participants commented during the initial intake session that several items (e.g., specifically items on the social role factor relating to employment) were not relevant to their situation because of under- or unemployment. Further, reducing OQ-45.2 to a 16-item assessment may provide a more user-friendly version requiring less time for respondents and more efficient use of clinical time; however, without further research, the current authors are hesitant to support its clinical use with this population of economically vulnerable individuals.

Similar to previous researchers (e.g., Kim et al., 2010; Rice et al., 2014), we also found evidence for the need for a substance use factor (e.g., Factor 3) in the 18-item abbreviated model; however, this model deviated from the original OQ-45.2. The findings of this study support the need for professional counselors to assess substance use as part of psychological distress, whether it be implementing the

18-item version of the OQ or adding an additional assessment that has greater reliability and validity of its items with this population.

Implications

We found initial, possible support for a brief version of the OQ-45.2 for economically vulnerable individuals. The abbreviated 16-item OQ assessment derived from this research requires less time to complete while capturing an individual’s distress on substance use, interpersonal relationships, and symptom distress. A brief instrument can provide professional counselors with a snapshot of the client’s concerns, which can assist in monitoring a client’s level of psychological distress throughout treatment. In clinical settings, counselors can utilize this instrument to briefly assess at intake the baseline distress of their clients and use it as a guide or conversation starter for discussing client distress. For example, a counselor may ask that the client complete the brief OQ-16 instrument with the intake paperwork. In review of all paperwork, the counselor may note to the client, “I noticed that you indicated high distress with interpersonal relationships. Is that a place you would like to begin, or do you have another place you want to begin?”

Further, we retained two critical items (i.e., Items 8 and 44) in the 18-item version of the OQ brief assessment, as psychological distress associated with economic vulnerability is linked to higher rates of suicide and homicide (Knifton & Inglis, 2020). Because of the clinical utility of this instrument, professional counselors may want to include those items to assess a client’s level of threat of harm to self or others. Dependent on the client’s answer to these critical items, professional counselors have a quick reference with which to intervene or focus the initial session to address safety. Therefore, the items of this assessment may possibly be used to start the initial dialogue regarding an individual’s psychological distress and/or suicidal intent; however, the assessment should not be used as the only tool or instrument to diagnose or treat psychological distress. We understand that these items can help professional counselors efficiently assess for suicidal or homicidal intent. Therefore, the counselor can opt to use the 16-item version and include an additional, more reliable assessment for measuring threat of harm to self and/or others. For example, counselors may opt to use an instrument such as the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions tool (Horowitz et al., 2012) to further evaluate suicidal intent.

In our experience, when following up with study participants based on a score higher than 1 on a scale of 1–5, many participants indicated they felt that way in the past but no longer feel that way now. In our use of the OQ-45.2, we find that participants tend to answer these questions based on their entire life versus the time frame indicated in the assessment instructions (the past week [7 days]). Therefore, professional counselors should be clear that respondents should answer based on the past week, rather than “ever experienced.” When offering the assessment to clients, we recommend that the counselor highlight the time frame in the instructions or clearly communicate that time frame to the client before they complete the instrument to gain the most accurate data.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

As with all research, results should be considered in light of limitations. The large study sample consisted of diverse individuals; however, the majority were women, and all individuals were from the southeast region of the United States, minimizing the generalizability of these findings. In addition, although findings indicate initial, possible support for a revised three-factor model consisting of 16 items, future studies are warranted to strengthen the validity of this abbreviated version of the OQ-45.2. We suggest that future researchers test the 16-item assessment through CFA with a similar population to confirm the current study’s findings. All respondents volunteered to participate in a 6-month study, which may indicate more motivation to improve or represent a population with distress responses different from those who were recruited but chose not to participate in the study. Additionally, study participants were actively recruited, and may have experienced less distress than a help-seeking sample.

The OQ is available in a Spanish translation; however, we only included people who completed the English OQ-45.2 version in the current study. Future analyses should examine the factor structure of the Spanish OQ-45.2 as well. Next, future research on the OQ should include the development and testing of new items. Lastly, future research should aim to validate the reduced 16-item and 18-item OQ scores on a new sample and seek to establish a new criterion for clinical significance. Professional counselors may also benefit from the creation of a specific instrument assessing distress related to the unique stressors that economically vulnerable clients face. Until further analyses are conducted with a new sample population to confirm the abbreviated models, we encourage professional counselors to implement the brief version tentatively and with caution, and to follow up with the client regarding high scores on critical items prior to making clinical judgments regarding reported subscale scores.

Conclusion

Given the broad utility of the OQ-45.2 in research and mental health settings, researchers and professional counselors must understand the instrument’s structure for interpretation purposes and how the assessment should be adapted for various populations. Professional counselors can effectively support clients by assessing and recognizing how economic-related distress impacts their quality of life, which may directly relate to treatment outcomes. Findings from the current study add to previous literature that calls into question the original OQ-45.2 factor structure. Additionally, the current study’s findings support a revised 16-item, three-factor structure for economically vulnerable clients and we provide implications for use of this assessment in clinical practice. Future research should include a confirmatory analysis of the current findings.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

This research was supported by a grant (90FM0078)

from the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services (USDHHS), Administration for Children and

Families, Office of Family Assistance. Any opinions,

findings, conclusions, or recommendations are those

of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views

of the USDHHS, Office of Family Assistance. The authors

reported no further funding or conflict of interest.

References

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

Beidas, R. S., Stewart, R. E., Walsh, L., Lucas, S., Downey, M. M., Jackson, K., Fernandez, T., & Mandell, D. S. (2015). Free, brief, and validated: Standardized instruments for low-resource mental health settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.02.002

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bludworth, J. L., Tracey, T. J. G., & Glidden-Tracey, C. (2010). The bilevel structure of the Outcome Questionnaire–45. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019187

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models. SAGE.

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Carlson, R. G., Fripp, J., Munyon, M. D., Daire, A., Johnson, J. M., & DeLorenzi, L. (2014). Examining passive and active recruitment methods for low-income couples in relationship education. Marriage & Family Review, 50(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2013.851055

Carlson, R. G., Rappleyea, D. L., Daire, A. P., Harris, S. M., & Liu, X. (2017). The effectiveness of couple and individual relationship education: Distress as a moderator. Family Process, 56(1), 91–104.

https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12172

Clark, M., Ausloos, C., Delaney, C., Waters, L., Salpietro, L., & Tippett, H. (2020). Best practices for counseling clients experiencing poverty: A grounded theory. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(3), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12323

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(7), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Dakin, J., & Wampler, R. (2008). Money doesn’t buy happiness, but it helps: Marital satisfaction, psychological distress, and demographic differences between low- and middle-income clinic couples. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 36(4), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180701647512

Eid, M., Geiser, C., Koch, T., & Heene, M. (2017). Anomalous results in G-factor models: Explanations and alternatives. Psychological Methods, 22(3), 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000083

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis (1st ed.). Guilford.

Espiridion, E. D., Oladunjoye, A. O., Millsaps, U., & Yee, M. R. (2021). A retrospective review of the clinical significance of the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ) measure in patients at a psychiatric adult partial hospital program. Cureus, 13(3), e13830. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.13830

Foss-Kelly, L. L., Generali, M. M., & Kress, V. E. (2017). Counseling strategies for empowering people living in poverty: The I-CARE Model. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 45(3), 201–213.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12074

Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson.

Hatfield, D. R., & Ogles, B. M. (2004). The use of outcome measures by psychologists in clinical practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35(5), 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.35.5.485

Henson, R. K., & Roberts, J. K. (2006). Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(3), 393–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282485

Hodgkinson, S., Godoy, L., Beers, L. S., & Lewin, A. (2017). Improving mental health access for low-income children and families in the primary care setting. Pediatrics, 139(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1175

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289447

Horowitz, L. M., Bridge, J. A., Teach, S. J., Ballard, E., Klima, J., Rosenstein, D. L., Wharff, E. A., Ginnis, K., Cannon, E., Joshi, P., & Pao, M. (2012). Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): A brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1170–1176.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 76–99). SAGE.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (2005). Contextual influences on marriage: Implications for policy and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(4), 171–174.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00358.x

Kim, S.-H., Beretvas, S. N., & Sherry, A. R. (2010). A validation of the factor structure of OQ-45 scores using factor mixture modeling. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 42(4), 275–295.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175609354616

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford.

Knifton, L., & Inglis, G. (2020). Poverty and mental health: Policy, practice and research implications. BJPsych Bulletin, 44(5), 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.78

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Lam, J. R., Tyler, J., Scurrah, K. J., Reavley, N. J., & Dite, G. S. (2019). The association between socioeconomic status and psychological distress: A within and between twin study. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 22(5), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2019.91

Lambert, M. J. (2017). Measuring clinical progress with the OQ-45 in a private practice setting. In S. Walfish, J. E. Barnett, & J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Handbook of private practice: Keys to success for mental health practitioners (pp. 78–93). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780190272166.003.0007

Lambert, M. J., Burlingame, G. M., Umphress, V., Hansen, N. B., Vermeersch, D. A., Clouse, G. C., & Yanchar, S. C. (1996). The reliability and validity of the Outcome Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 3(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199612)3:4<249::AID-CPP106>3.0.CO;2-S

Lambert, M. J., Gregersen, A. T., & Burlingame, G. M. (2004). The Outcome Questionnaire-45. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults (3rd ed.; pp. 191–234). Routledge.

Lambert, M. J., Smart, D. W., Campbell, M. P., Hawkins, E. J., Harmon, C., & Slade, K. L. (2006). Psychotherapy outcome, as measured by the OQ-45, in African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Latino/a, and Native American clients compared with matched Caucasian clients. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 20(4), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1300/J035v20n04_03

Levy, H. C., Worden, B. L., Davies, C. D., Stevens, K., Katz, B. W., Mammo, L., Diefenbach, G. J., & Tolin, D. F. (2020). The dose-response curve in cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 49(6), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2020.1771413

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.2307/2290157

Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46(3), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

Mueller, R. M., Lambert, M. J., & Burlingame, G. M. (1998). Construct validity of the Outcome Questionnaire: A confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 70(2), 248–262.

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa7002_5

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables. User’s guide. (7th ed.)

https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_7.pdf

Mvududu, N. H., & Sink, C. A. (2013). Factor analysis in counseling research and practice. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 4(2), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137813494766

Näher, A.-F., Rummel-Kluge, C., & Hegerl, U. (2020). Associations of suicide rates with socioeconomic status and social isolation: Findings from longitudinal register and census data. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(898), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00898

Osborne, J. W. (2013). Best practices in data cleaning. SAGE.

Pearson, M., Stanley, S. M., & Rhoades, G. K. (2015). Within My Reach leader manual. PREP for Individuals, Inc.

Rice, K. G., Suh, H., & Ege, E. (2014). Further evaluation of the Outcome Questionnaire–45.2. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 47(2), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175614522268

Santiago, C. D., Wadsworth, M. E., & Stump, J. (2011). Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(2), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.008

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C. C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). SAGE.

Semega, J., Kollar, M., Shrider, E. A., & Creamer, J. F. (2021). Income and poverty in the United States: 2019. Current population reports. U.S. Census Bureau.

https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.pdf

Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality. (2015). State of the states: The poverty and inequality report. Pathways. http://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/SOTU_2015.pdf

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Tabet, S. M., Lambie, G. W., Jahani, S., & Rasoolimanesh, S. (2019). The factor structure of the Outcome Questionnaire–45.2 scores using confirmatory tetrad analysis—partial least squares. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282919842035

Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38, 1–10.

Dalena Dillman Taylor, PhD, LMHC, RPT-S, is an associate professor at the University of North Texas. Saundra M. Tabet, PhD, NCC, CCMHC, ACS, LMHC, is an assistant professor and CMHC Program Director at the University of San Diego. Megan A. Whitbeck, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at The University of Scranton. Ryan G. Carlson, PhD, is a professor at the University of South Carolina. Sejal Barden, PhD, is a professor at the University of Central Florida. Nicole Silverio is an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina. Correspondence may be addressed to Dalena Dillman Taylor, 1300 W. Highland St., Denton, TX 76201, Dalena.dillmantaylor@unt.edu.

Apr 1, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 2

Fei Shen, Yanhong Liu, Mansi Brat

The present study examined the relationships between childhood attachment, adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress; specifically, it investigated the multiple mediating roles of self-esteem and adult attachment on the association between childhood attachment and psychological distress. Using 1,708 adult participants, a multiple-mediator model analysis following bootstrapping procedures was conducted in order to investigate the mechanisms among childhood and adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress. As hypothesized, childhood attachment was significantly associated with self-esteem, adult attachment, and psychological distress. Self-esteem was found to be a significant mediator for the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment. In addition, adult attachment significantly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and psychological distress. The results provide insight on counseling interventions to increase adults’ self-esteem and attachment security, with efforts to decrease the negative impact of insecure childhood attachment on later psychological distress.

Keywords: childhood attachment, adult attachment, self-esteem, psychological distress, mediator

Attachment has been widely documented across disciplines, following Bowlby’s (1973) foundational work known as attachment theory. Attachment, in the context of child–parent interactions, is defined as a child’s behavioral tendency to use the primary caregiver as the secure base when exploring their surroundings (Bowlby, 1969; Sroufe & Waters, 1977). Research has shed light on the significance of childhood attachment in predicting individuals’ intrapersonal qualities such as self-esteem and emotion regulation during adulthood (Brennan & Morris, 1997), interpersonal orientations examined through attachment variation and adaptation across different developmental stages (Sroufe, 2005), and overall psychological well-being (Cassidy & Shaver, 2010; Wright et al., 2014).

Given its clinical significance, attachment has gained increased interest across disciplines. For example, childhood attachment was found to significantly predict coping and life satisfaction in young adulthood (Wright et al., 2017). Relatedly, a 30-year longitudinal study reinforces the vital role of childhood attachment in predicting individuals’ development of “the self and personality” (Sroufe, 2005, p. 352). Sroufe’s (2005) study reinforced the vital role of attachment across the life span. As an outcome variable, attachment is asserted to be associated with empathy (Ruckstaetter et al., 2017) and parenting practice in the adoptive population (Liu & Hazler, 2017). Considering the interplay between individuals’ relationship evolvement and their living contexts (Bowlby, 1973; Sroufe, 2005), attachment is examined at different stages generally labelled as childhood attachment and adult attachment, with the former focusing on the infant/child–parent relationship and the latter on adults’ generalized relationships with intimate others (e.g., romantic partners, close friends). Because of the abstract nature of attachment, it is commonly measured in the form of childhood attachment styles (Ainsworth et al., 1978) or adult attachment orientations (Turan et al., 2016).

Conceptual Framework

The present study is grounded in attachment theory, which is centered around a child’s ability to utilize their primary caregiver as the secure base when exploring surroundings, involving an appropriate balance between physical proximity, curiosity, and wariness (Bowlby, 1973; Sroufe & Waters, 1977). A core theoretical underpinning of attachment theory is the internal working model capturing a child’s self-concept and expectations of others (Bretherton, 1996). Internal working models of self and other are complementary. Namely, a child with strong internal working models is characterized with a perception of self as being worthy and deserving of love and a perception of others as being responsive, reliable, and nurturing (Bowlby, 1973; Sroufe, 2005).

In the context of attachment theory, childhood attachment is considered an outcome of consistent child–caregiver interactions and serves as the foundation for individuals’ later personality development (Bowbly, 1973; Sroufe, 2005). In line with child–caregiver interactions, Ainsworth et al. (1978) came up with three attachment styles based upon Bowlby’s seminal work, including secure, anxious-ambivalent, and anxious-avoidant attachment, following sequential phases of laboratory observations. Attachment theory was subsequently extended beyond the child–parent relationship to include later relationships in adulthood, given the parallels between these relationships (Cassidy & Shaver, 2010). Likewise, four distinct adult attachment styles (i.e., secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful) are referred to based on the two-dimensional models of self and other (Konrath et al., 2014). Adult attachment styles are commonly examined under two orientations: attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety (Turan et al., 2016). Individuals showing low avoidance and low anxiety are considered securely attached, whereas those with high levels of anxiety and avoidance tend to be insecurely attached. Although childhood attachment and adult attachment are broadly considered distinct concepts in the literature, they share a spectrum of behaviors spanning from secure to insecure attachment. The levels of avoidance and anxiety involved in these behaviors are used as parameters to differentiate securely attached individuals from those who are insecurely attached.

Childhood Attachment, Self-Esteem, and Adult Attachment

Despite the conceptual overlaps, childhood attachment to caregivers and adult attachment to intimate others are commonly investigated as two distinct variables associated with individuals’ needs and features of different relationships. Childhood attachment captures a child’s distinct relationship with the primary caregiver (e.g., the mother figure) as well as their ability to differentiate the primary caregiver from other adults (Bowlby, 1969, 1973), whereas adult attachment may involve an individual’s multiple relationships (with parents, a romantic partner, or close friends). Noting the general stability of attachment from childhood to adulthood (Fraley, 2002), previous conceptual work stresses the importance of contexts in individuals’ attachment evolvement, highlighting that “patterns of adaptation” and “new experiences” reinforce each other in a reciprocal way (Sroufe, 2005, p. 349). For instance, an individual may develop secure attachment in adulthood because of healthy interpersonal experiences likely facilitated by trust, support, and nurturing received from significant others or their relationships, despite showing insecure attachment patterns in early childhood. A dynamic view of attachment development is thus warranted.

From a dynamic lens, researchers have generated evidence for the association between childhood attachment and adult attachment (Pascuzzo et al., 2013; Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997). For example, in a study of 879 college students (Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997), participants’ perception of their childhood attachment to both mother and father significantly predicted 7.9% of the variance in their adult attachment scores. Similarly, Pascuzzo et al. (2013) followed 56 adolescents at age 14 through age 22 and found that attachment insecurity to both parents and peers during adolescence was significantly associated with anxious romantic attachment in adulthood as measured by the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR; Brennan et al., 1998). Studies that rely on retrospective data to assess childhood attachment (e.g., Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997) may be limited in validity because of time elapsed and potential compounding variables.

Childhood attachment is well recognized as the foundation for the growth of self-reliance and emotional regulation (Bowlby, 1973). Aligning with self-reliance, self-esteem appears to be frequently studied primarily through self-liking and self-competence (Brennan & Morris, 1997). Brennan and Morris (1997) defined self-liking as general self-evaluation based on perceived positive regard from others, and self-competence as concrete self-evaluation based on personal abilities and attributes. Previous research has suggested that secure attachment (to parents and peers) is significantly associated with higher levels of self-esteem (e.g., Wilkinson, 2004). In contrast, individuals who reported insecure attachment tended to endorse low self-esteem (Gamble & Roberts, 2005).

These results provide theoretical and empirical evidence for links between childhood attachment and adult attachment, but these links are likely to be indirect and mediated by other relevant variables from developmental perspectives. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the effect of self-esteem on the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment. The theoretical framework of attachment theory indicates that childhood attachment can have not only direct effects on adult attachment, but also indirect effects on adult attachment via self-esteem. In order to develop effective interventions tackling issues with adult attachment, it is important to examine potential mediators (e.g., self-esteem) between childhood attachment and adult attachment. To address this gap, the present study tests this hypothesized mediation function of self-esteem with a nonclinical sample of adults.

Self-Esteem, Attachment, and Psychological Distress

The extant literature comprises prolific information on the relationship between attachment and psychological well-being (Gnilka et al., 2013; Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; M. E. Kenny & Sirin, 2006; Turan et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2014). Existing evidence focuses on the relationship between adult attachment orientations and individuals’ psychological well-being (e.g., Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; Lynch, 2013; Roberts et al., 1996; Sowislo & Orth, 2013). Nevertheless, previous research has shed some light on the role of early childhood attachment in predicting psychological distresses in adulthood, including depression and anxiety (Bureau et al., 2009; Lecompte et al., 2014; Styron & Janoff-Bulman, 1997). Lecompte and colleagues (2014) conducted a longitudinal study of a sample of preschoolers (N = 68) with data collected at 4 years and again at 11–12 years; results of the study suggested that children with disorganized attachment at the baseline scored higher in both anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to those classified as securely attached.

Likewise, the effect of self-esteem on psychological distress is well established. A meta-analysis on 80 longitudinal studies published between 1994 and 2010 yielded consistent evidence supporting the relationship between low self-esteem and depressive symptoms (Sowislo & Orth, 2013). More recently, Masselink et al. (2018) examined data collected at four different points of participants’ development from early adolescence to young adulthood, which demonstrated that low self-esteem constitutes a persistent risk factor for participants’ depressive symptoms across developmental stages. Moreover, self-esteem scores in early adolescence significantly predicted the participants’ depressive symptoms at later stages, specifically during late adolescence and young adulthood.

Research has also supported the association between self-esteem, adult attachment, and psychological distress. Lopez and Gormley (2002) followed 207 college students from the beginning to the end of their freshman year and identified adjustment outcomes in association with the participants’ attachment styles and changes of their attachment styles measured by the ECR (e.g., secure-to-insecure attachment, insecure-to-secure attachment). The authors found that participants who remained securely attached scored higher in self-confidence and lower in both psychological distress and reactive coping compared to those who reported consistent insecure attachment. Moreover, participants who maintained secure attachment presented better outcomes in self-confidence and psychological well-being than the comparative group with secure-to-insecure or insecure-to-secure attachment changes (Lopez & Gormley, 2002). Adult attachment (measured by the ECR) was also found to be a mediator for the effects of traumatic events on post-traumatic symptomatology among a sample of female college students (Sandberg et al., 2010). In addition, Roberts et al. (1996) suggested attachment insecurity contributed to negative beliefs about oneself, which in turn activated cognitive structures of psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety, with a sample of 152 undergraduate students.

Taken together, the literature provides consistent support for the significant relationships between childhood attachment and various outcome variables in later adulthood, including adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress. It further reveals a two-fold gap: (a) the variables tended to be investigated separately in previous studies, yet the mechanisms among these variables remained underexplored; and (b) little is known about the role of self-esteem and adult attachment in the association between childhood attachment and psychological distress. Disentangling the mechanisms, including potential mediating roles, involved in the variables will enrich the current knowledge based on attachment and can facilitate counseling interventions surrounding the effects of childhood attachment. In tackling the gap, three hypotheses were posed:

1. Childhood attachment is significantly associated with adult attachment, self-esteem, and psychological distress.

2. Self-esteem mediates the relationship between perceived childhood attachment and adult attachment.

3. Adult attachment mediates the relationship between self-esteem and

psychological distress.

Method

Participants

Of the 2,373 voluntary adult participants who took the survey, 1,708 (72%) completed 95% of all the questions and were retained for final analysis. Among the participants, 76.2% (n = 1,302) were female, 22.3% (n = 381) were male, and 1.3% (n = 25) chose not to specify their gender. The mean age of the participants was 29.89, ranging from 18 to 89 years old (SD = 12.44). A total of 66.3% (n = 1,133) of participants described themselves as White/European American, 8.7% (n = 148) as African American, 10.2% (n = 175) as Asian/Pacific Islander, 2.6% (n = 44) as American Indian/Native American, 7.3% (n = 124) as biracial or multiracial, 3.6% (n = 61) as other race, and 1.3% (n = 23) did not specify.

Sampling Procedures

The study was approved by the university’s IRB. We posted the recruitment information on various websites (e.g., Facebook, discussion board, university announcement board, Craigslist) in order to recruit a diverse pool of participants. Individuals who were 18 years old or above and were able to fill out the questionnaire in English were eligible for participating in this project. Participants were directed to an online Qualtrics survey consisting of the measures discussed in the following section. An informed consent form was included at the beginning of the survey outlining the confidentiality, voluntary participation, and anonymity of the study. Participants were prompted to enter their email addresses to win one of ten $15 e-gift cards. Participants’ email addresses were not included in the survey questions and data analysis.

Measures

Psychological Distress

Psychological distress was measured using the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2003). Participants were asked about their emotional states in the past four weeks (e.g., “How often did you feel nervous?”). Responses were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (None of the time) to 4 (All of the time). Scores were averaged, with a higher score indicating a higher level of psychological distress. Previous studies using K10 have provided evidence of validity (Andrews & Slade, 2001). The internal consistency for K10 has been well established with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from .88 (Easton et al., 2017) to .94 (Donker et al., 2010). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .94.

Childhood Attachment

Childhood attachment was measured using the Parental Attachment subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). Previous research has demonstrated evidence that this measure has great convergent and concurrent validity (M. E. Kenny & Sirin, 2006). The IPPA has been used to recall childhood attachment in adult populations (Aspelmeier et al., 2007; Cummings-Robeau et al., 2009). This 25-item subscale directs participants to recall their attachment to the parent(s) or caregiver(s) who had the most influence on them during childhood. The subscale consists of three dimensions, including 10 items on trust, nine items on communication, and six items on alienation. Some sample items are: “My parent(s)/primary caregiver(s) accepts me as I am” for trust, “I tell my parent(s)/primary caregiver(s) about my problems and troubles)” for communication, and “I do not get much attention from my parent(s)/primary caregiver(s)” for alienation. Participants rated the items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Almost never or never true) to 5 (Almost always or always true). Items were averaged to form the subscale, with a higher score reflecting more secure childhood attachment. The subscale has demonstrated high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .93 (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the subscale was .96.

Adult Attachment

Adult attachment was measured using the ECR (Brennan et al., 1998). The ECR consists of 36 items with 18 items assessing each of the two orientations: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. In order to avoid confounding factors, we only assessed adult attachment with close friends or romantic partners, as relationships with parents can confound the childhood attachment outcomes. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Two scores were averaged, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of attachment anxiety or avoidance. In terms of validity, the ECR subscales have been found to be positively associated with psychological distress and intention to seek counseling, and negatively associated with social support (Vogel & Wei, 2005). The ECR has a high internal consistency for both the anxiety (α = .91) and avoidance (α = .94) dimensions (Brennan et al., 1998). For this study, Cronbach’s alphas for attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were .93 and .92, respectively.

Self-Esteem

Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965) is a 10-item scale designed to assess an adult’s self-esteem. The scale assesses both self-competency (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) and self-liking (e.g., “I certainly feel useless at times”). Responses were coded using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). Negatively worded statements were reverse-coded. Scores were averaged, with a higher score reflecting a higher level of self-esteem. RSES has been frequently used in various studies with high reliability and validity (Brennan & Morris, 1997; Chen et al., 2017). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .89.

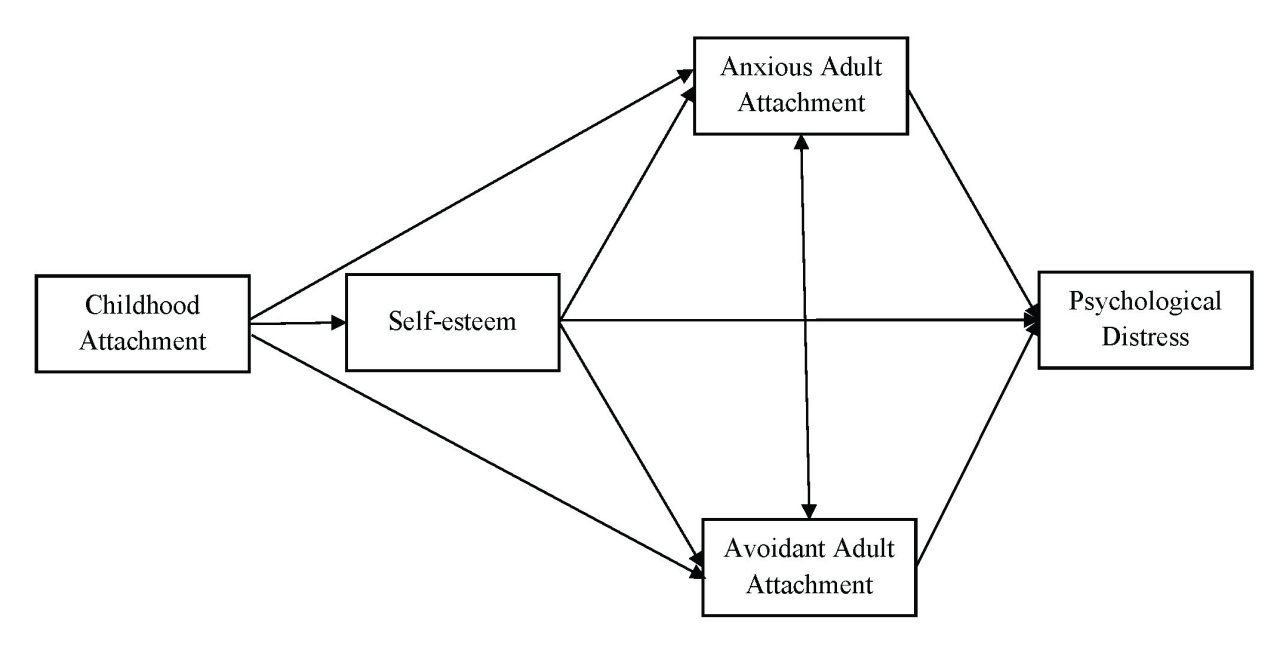

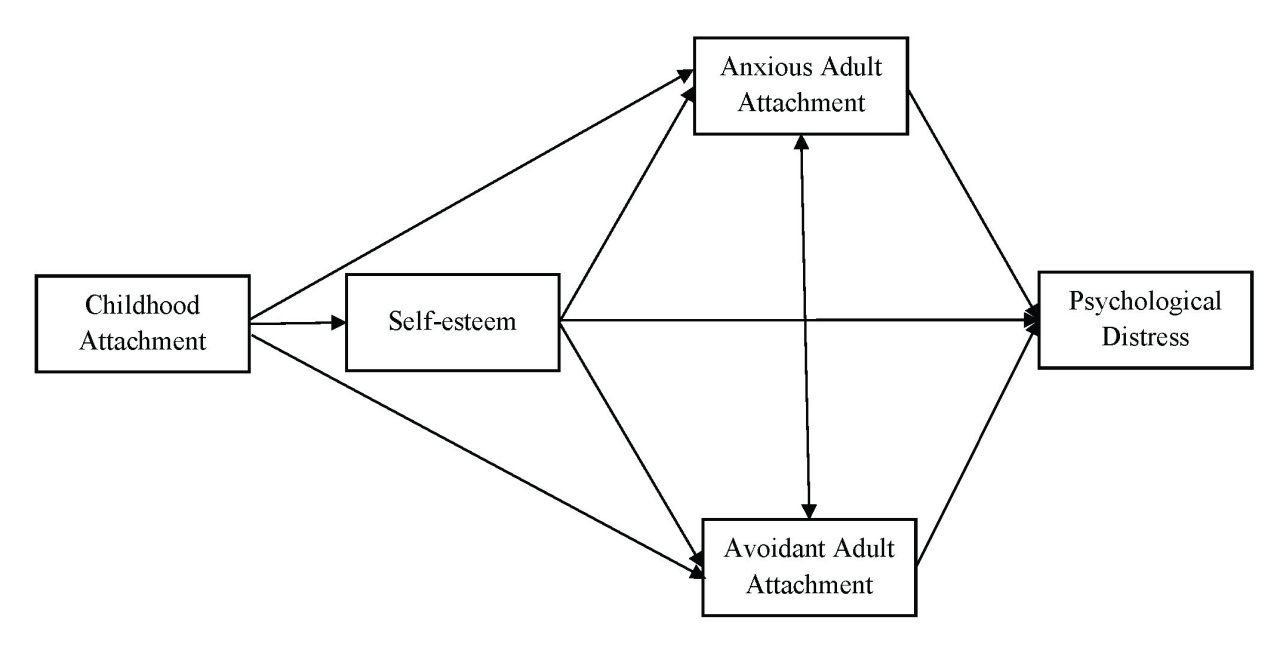

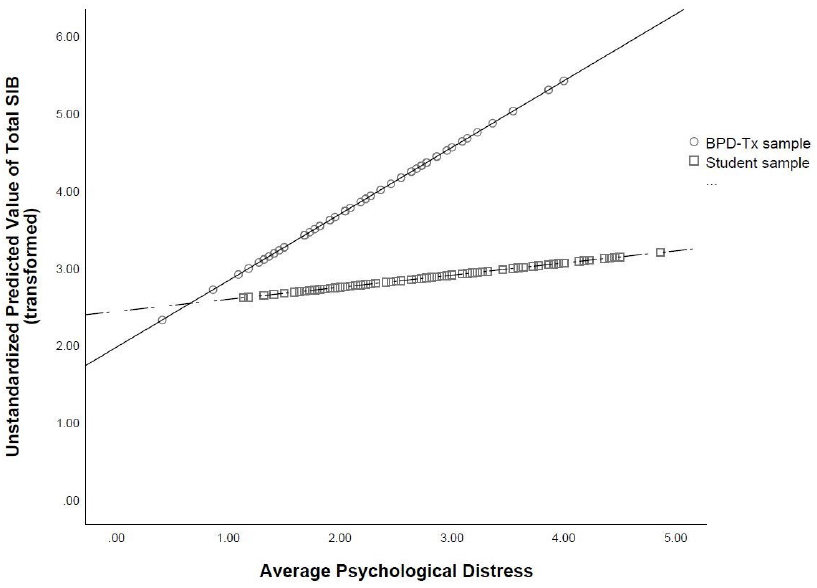

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed using SPSS version 23 followed by a multiple-mediator model analysis using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Missing data were treated with the full information maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus, which was one of the most pragmatic approaches in producing unbiased parameter estimates (Acock, 2005). The multiple-mediator model includes childhood attachment as the predictor, self-esteem and adult attachment anxiety and avoidance as mediators, and psychological distress as the outcome variable (see Figure 1). The mediation analysis was conducted using bootstrapping procedures (J = 2,000), which was a resampling method to construct a confidence interval for the indirect effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Several model fit indices based on Kline’s (2010) guidelines were employed, including the ratio of chi-square to degree of freedom (χ2/df), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Indicators of good model fit are a nonsignificant chi-square value, a CFI and TLI of .90 or greater, RMSEA of .08 or less, and an SRMR of .05 or less (Hooper et al., 2008).

Figure 1

Multiple-Mediator Model: Self-Esteem, Anxious Adult Attachment, and Avoidant Adult Attachment as Multiple Mediators Between Childhood Attachment and Psychological Distress

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

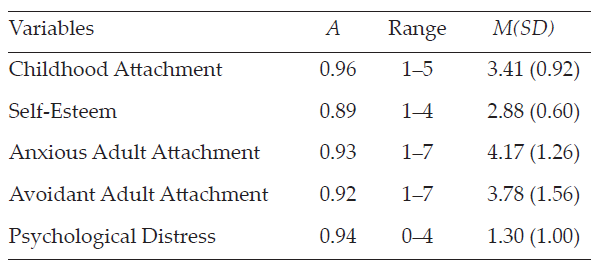

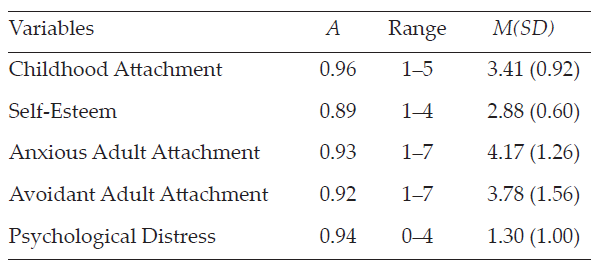

The descriptive statistics of each variable are reported in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Variables (N = 1,708)

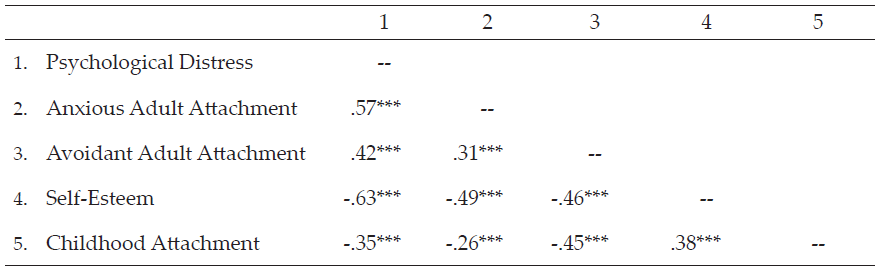

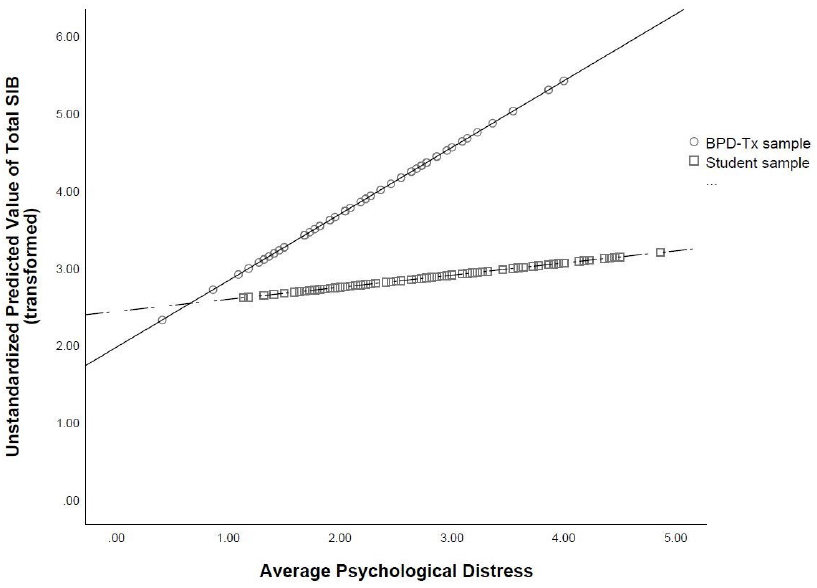

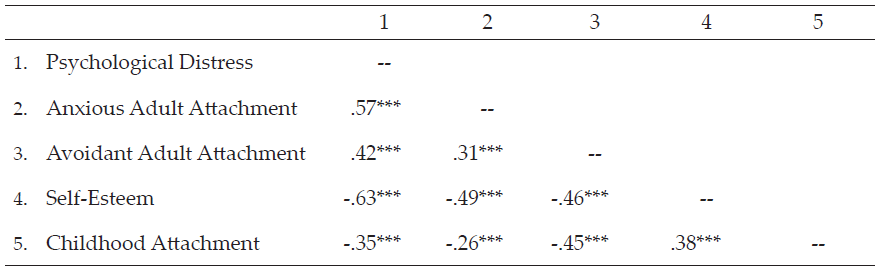

Pearson’s correlations between variables were computed. All bivariate statistics are presented in Table 2 and provided full support for our Hypothesis 1. For instance, childhood attachment was positively associated with self-esteem (r = .38, p < .001) and negatively correlated with adult attachment anxiety (r = -.26, p < .001) and avoidance (r = -.45, p < .001), as well as with psychological distress (r = -.35, p < .001). Significant negative correlations were found between self-esteem and adult attachment anxiety (r = -.49, p < .001) and avoidance (r = -.46, p < .001), and between self-esteem and psychological distress (r = -.63, p < .001). Both adult attachment anxiety (r = .57, p < .001) and avoidance (r = .42, p < .001) were positively associated with psychological distress. Significant correlation was found between adult attachment anxiety and avoidance (r = .31, p < .001).

Table 2

Correlation Matrix of Variables (N = 1,708)

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001 (two-tailed).

The Multiple-Mediator Model

The multiple-mediator model involving self-esteem and adult attachment as mediators, with bootstrapping procedures, yielded satisfactory fit indices: χ2(1) = 12.24, p < .001, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = .01. However, the index of RMSEA = .08, 90% CI [0.05, 0.12] indicated a mediocre fit, with the upper value of 90% CI larger than the suggested cutoff score of 0.08. D. A. Kenny et al. (2015) suggested that the models with small degrees of freedom had the average width of the 90% CI above 0.10, unless the sample size was extremely large. The nonsignificant χ2 value was interpreted as a good fit index.

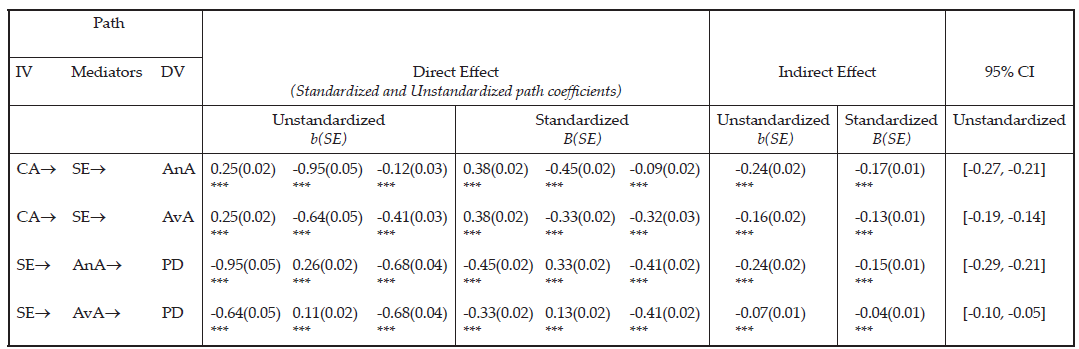

The present study further revealed that secure childhood attachment was associated with high self-esteem (β = .25, p < .001) and low levels of anxiety (β = -.12, p < .001) and avoidance (β = -.41, p < .001) of adult attachment. Meanwhile, high self-esteem was associated with low anxiety (β = -.95, p < .001) and low avoidance (β = -.64, p < .001) of adult attachment. In addition, high self-esteem (β = -.68, p < .001) and low adult attachment anxiety (β = .26, p < .001) and avoidance (β = .11, p < .001) were significantly associated with low psychological distress. The results supported both Hypotheses 2 and 3 in that self-esteem mediated the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment, and adult attachment mediated the relationship between self-esteem and psychological distress.

The mediating role of self-esteem was examined using bootstrapping procedures. Results demonstrated that self-esteem significantly mediated the association between childhood attachment and adult attachment anxiety (b = -.24, 95% CI [-0.27, -0.21]) and avoidance (b = -.16, 95% CI [-0.19, -0.14]).

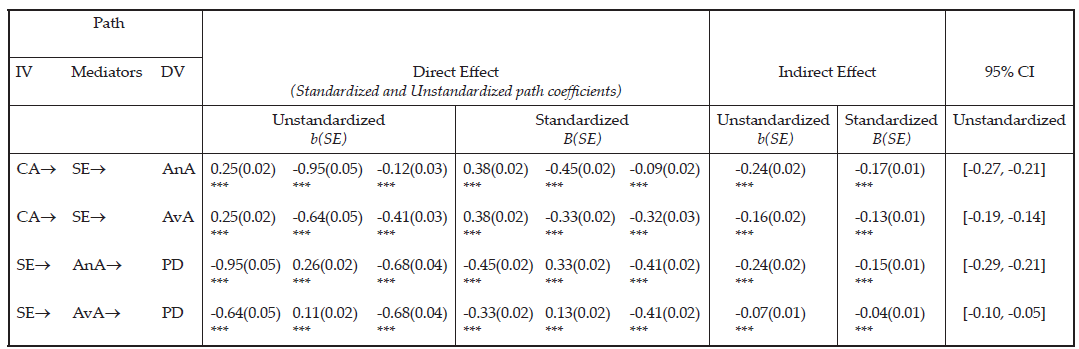

The present study further supported the mediating role of adult attachment (i.e., anxiety and avoidance). The association between self-esteem and psychological distress was significantly mediated by both adult attachment anxiety (b = -.24, 95% CI [-0.29, -0.21]) and avoidance (b = -.07, 95% CI [-0.10, -0.05]). Mediation effects are denoted in Table 3.

Table 3

Mediation Analysis With Bootstrapping: Unstandardized and Standardized Estimates and Confidence Intervals for Mediation Effects

Note. Bootstrap J = 2,000, CI = confidence interval; IV = independent variable; DV = dependent variable; CA = Childhood Attachment; SE = Self-Esteem; AnA = Anxious Adult Attachment; AvA = Avoidant Adult Attachment; PD = Psychological Distress. Direct effect of path direction, IV® Mediator, Mediator ® DV, IV ® DV. Statistical significance was evaluated based on whether 95% bias corrected bootstrap CIs include zero or not. If zero was included in the CI, then it was not a significant indirect effect. Model fit: χ2(1) = 12.24, p < .001, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = .01, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI [0.05, 0.12]).

Discussion

The present study highlights the significance of childhood attachment and its associations with self-esteem and psychological distress in adulthood. Participants who reported secure childhood attachment scored higher on self-esteem and lower on psychological distress. Secure childhood attachment was also found to be associated with low adult attachment anxiety and avoidance. Our study builds upon previous research (e.g., Sroufe, 2005) to capture the complexity of key variables related to attachment and its evolvement from childhood to adulthood. The results shed further light on the mechanisms among childhood attachment, self-esteem, adult attachment, and psychological distress. Self-esteem was found to be a significant mediator between childhood attachment and adult attachment; meanwhile, adult attachment was found to be a mediator between self-esteem and psychological distress.

The findings support Hypothesis 1 in that individuals with more secure childhood attachment reported higher levels of self-esteem, lower levels of adult attachment anxiety and avoidance, and less psychological distress. The results echo attachment theory (Bowlby, 1973), positing childhood attachment as a predictor of later adjustment as well as self-esteem, indicating that the quality of attachment appears to be intimately related to how to cope with stress and how to perceive oneself (Wilkinson, 2004). The results are also consistent with previous research that highlighted secure childhood attachment as a protective factor against anxiety, depression, and later emotional and relational distress (e.g., Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012).

Results also lend support to Hypothesis 2 in that self-esteem mediated the relationship between childhood attachment and adult attachment. Self-esteem as a mediator echoed previous research that indicated the influence of childhood attachment on one’s self-esteem may be mitigated by expanded social networks in adulthood (Steiger et al., 2014). For instance, it is likely that improving self-esteem through peer connections (e.g., friendship; romantic relationships) may contribute to individuals’ adaptation to close relationships and enhance attachment security in adulthood, despite their insecure attachment with primary caregivers in childhood (Fraley, 2002; Sroufe, 2005).