Dec 22, 2025 | Volume 15 - Issue 4

Ne’Shaun J. Borden, Natalie A. Indelicato, Jamie F. Root, Lanni Brown

In this secondary qualitative data analysis, we examined data collected between 2018 and 2023 from See the Girl: In Elementary (formerly Girls Matter: It’s Elementary), a program model grounded in Relational–Cultural Theory that intervenes early in elementary school to improve school success and relational connection, decrease suspension and expulsion, and mitigate system involvement. African American girls ages 8 to 9 comprise 79% of the participants in this study. A reflexive thematic analysis focused on two open-ended questions from a larger program assessment tool: how the girls knew that their counselor listened and how the program was helpful to them. The analysis yielded three major themes for each research question. Girls knew counselors were listening to them through active listening, therapeutic support, and authenticity. Girls stated that the program helped them develop coping and relationship-building skills and provided them with a supportive environment. Given these findings, mental health professionals and supervisors are encouraged to prioritize culturally responsive models.

Keywords: girls, elementary, intervention, relational–cultural theory, culturally responsive

School disciplinary reforms following the 1994 Gun-Free Schools Act brought about zero tolerance policies, calling for mandatory punitive measures for students who violate codes of school conduct (Kang-Brown et al., 2013). Though evidence for the efficacy of such practices is lacking (American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008; Lamont et al., 2013; LiCalsi et al., 2021), these policies have since become widespread; as of the 2021–2022 school year, 62% of schools in the United States had a zero tolerance policy in effect. Of these, 76% allowed for students to be suspended for minor or nonviolent offenses such as talking back to a teacher or being inattentive in class (The Brookings Institution, 2023). Troublingly, these policies are applied disproportionately to students of color, children from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and those with disabilities (Anderson & Ritter, 2017; Anyon et al., 2014; Brobbey, 2017; Ryberg et al., 2021; Welsh & Little, 2018). According to recent Department of Education data, while Black boys are overrepresented among students who are suspended or expelled, Black girls are almost twice as likely as White girls to face expulsion or suspension (U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2023). Research has shown that students who are suspended or expelled in earlier grades are more likely to face suspension or expulsion in high school, to subsequently leave school, and to enter the juvenile justice system (Anyon et al., 2014; Novak, 2018; Skiba et al., 2014; Vanderhaar et al., 2014).

In response to these harsh disciplinary measures and in line with current recommendations from the Department of Education (U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2023), several experimental school-based positive intervention programs have been implemented and studied as alternatives. The Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) framework evolved in the late 1990s into School-Wide Positive Behavioral Support (SWPBS), a comprehensive system of behavioral support for the entire population of students across the school. This approach emphasizes a multitiered system of support utilizing evidence-based practices, focusing on implementing interventions that have proven effective in other packaged or manualized formats rather than relying on a standardized set of interventions (California Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, 2023; Sugai et al., 2000). SWPBS has been found to be a positive alternative to exclusionary discipline practices, as studies have demonstrated that schools that implement SWPBS programs with fidelity show marked decreases in disciplinary referrals and suspensions (Bradshaw et al., 2009; Gage et al., 2018). SWPBS is the most widely used school-based positive intervention program, with over 25,000 schools currently utilizing some form of this approach (Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports, 2024). Additional school-based positive intervention programs showing positive student outcomes include the Building Bridges program (Hernandez-Melis et al., 2016; Rappaport, 2014) and the Monarch Room, a trauma-informed alternative to suspension, utilized over a span of 3 years in an urban public charter school (Baroni et al., 2016).

Although exclusionary disciplinary practices have been widely adopted in U.S. schools over the past 30 years, their efficacy is not supported by the evidence, and the unequal application of such measures has raised significant concerns about equity and long-term student outcomes. Alternative interventions show promise in reducing disciplinary referrals and suspensions, particularly when implemented with fidelity and cultural sensitivity (Gage et al., 2018; Hernandez-Melis et al., 2016). Continued research and adaptation of such approaches is essential to create more equitable and effective disciplinary practices in schools.

See the Girl: In Elementary Program

Our study examines data from the Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, conceptualized in 2007 and opened in 2013. The mission of the Policy Center is to “advance the rights of girls and elevate justice reform, gender equity, and system accountability through research-based community solutions, and bold policy—all with a girl-centered approach.” (See the Girl, n.d.). The Policy Center focuses on research, advocacy, training, and programming for girls. The See the Girl: In Elementary program (SGIE; formerly Girl Matters®: It’s Elementary) is one of the model programs developed by the Policy Center to help mitigate the impact of the school-to-prison pipeline for girls in Florida during the early 2000s. SGIE focuses on school-level interventions, one-on-one skill building, referrals for services in the community, crisis intervention, and home visits (Patino Lydia et al., 2014). Program staff oversee the delivery of these interventions and train graduate and undergraduate counseling interns to provide one-on-one support for girls. The aims of the SGIE programming model are to “1) improve school success, 2) interrupt the suspension and expulsion of girls, and 3) prevent the spiraling effect of girls entering the juvenile justice system” (Patino Lydia et al., 2014, p. 2).

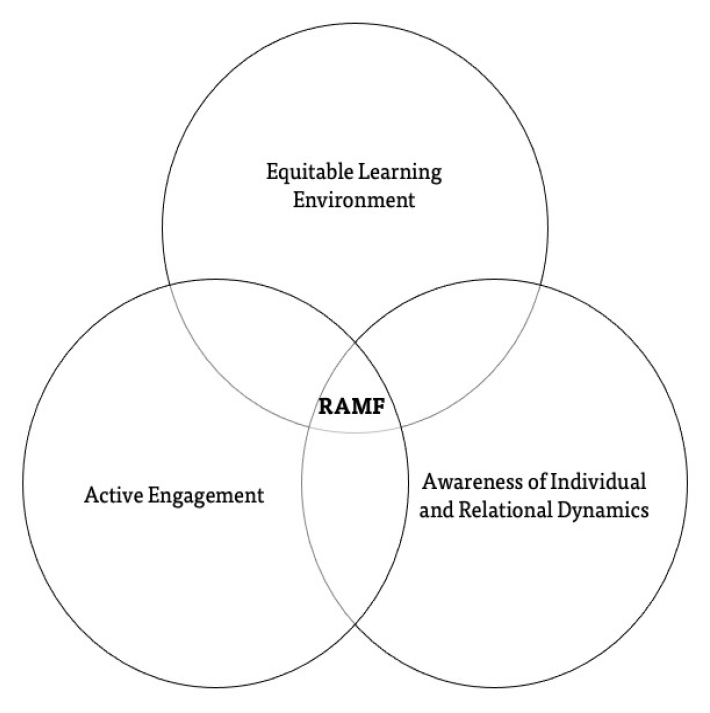

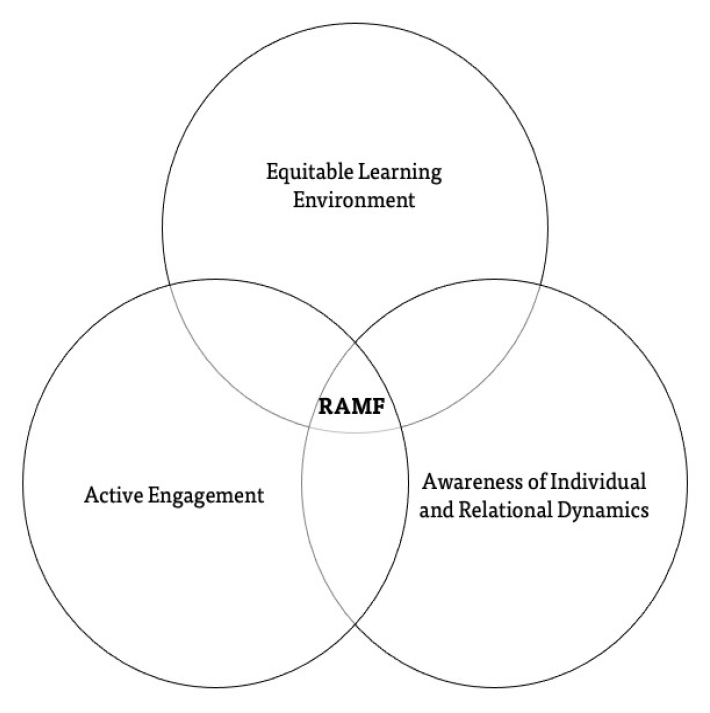

In order to meet these goals, the developers of SGIE created a program underpinned by tenets of Relational–Cultural Theory (RCT; Jordan, 2017). RCT exists within a feminist framework, one that assesses beyond individual factors and recognizes the broader impact that the environment has on girls, girls’ behavior, and crimes committed by girls (Patino Lydia & Moore, 2015). At its foundation, RCT is about relationships and growth, espousing the idea that we are born to create and maintain relational connections (Miller, 1976). Noting that individualistic, Western approaches of isolation and maladaptive independence can stunt developmental growth, RCT emphasizes culture, community, and the innate desire for interconnectedness (Jordan, 2017; Lenz, 2014). Healthy developmental growth is conceptualized through the perspective of RCT as active participation in growth-fostering relationships and genuine connections with others (Lenz, 2014). Relationships defined as growth-fostering are ones that empower both members to dually affect and be affected via the “five good things” (i.e., sense of zest, worth, productivity/creativity, clarity, desire for more connection; Jordan, 2017; Lenz, 2014).

Women and girls internalize numerous identities (e.g., sister, daughter, mother) that hold the power to shape the way they interact with the world around them (Patino Lydia & Moore, 2015). Grounded in RCT, the SGIE programming model seeks to move away from “blame and pathologize” to highlighting the distinct relational features that criminal justice systems, schools, and society have overlooked in understanding girls’ development (Patino Lydia & Moore, 2015).

Purpose of the Present Study

A pilot evaluation of the program examined data collected between 2011 and 2014 and showed positive and promising results at the girl, school, and community levels, including an 84% decrease in suspensions during the 2013–2014 school year (Patino Lydia et al., 2014). Similarly, 85% of girls reported that skill building with the assistance of the counseling intern was the most helpful aspect of the program. Although the initial evaluation showed positive results, with girls reporting that they felt more confident after learning skills, research did not indicate which aspects of the girls’ interactions with their counselors were most helpful. Thus, we sought to explore what aspects of the SGIE program were most impactful for the participants.

Positive, relationally based interventions show promise in reducing disciplinary referrals and suspensions, particularly when implemented with fidelity and cultural sensitivity (Gage et al., 2018; Hernandez-Melis et al., 2016). Continued research and replication of such approaches are essential to create more equitable and effective disciplinary practices in schools. Additionally, calls for research that include perspectives from the youth utilizing programming have been made to determine efficacious, culturally responsive interventions that improve academic and social outcomes (Goodman-Scott et al., 2024; Wymer et al., 2024). Researchers conducted a secondary analysis of two qualitative, open-ended questions from 2018–2023 assessment data with girls in the SGIE program to better understand which aspects of the program and interactions with their counselors were most helpful. This study focused on two open-ended questions from a broader assessment used by the Policy Center to collect data on the girls’ experiences in the program: 1) How do you know your counselor listens to you? and 2) How has SGIE been helpful to you?

Method

Prior to accessing the data, we worked in collaboration with the Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center to learn about the SGIE program, identify the program’s assessment process, and develop appropriate research questions, after which we obtained IRB approval. The secondary data used for this study are part of a larger assessment interview of girls participating in the SGIE program. Every aspect of the Policy Center’s work is girl-centered with the aim to inform the work based on girls’ lived experiences and voices. The girl-centered approach led us to focus on analysis of two open-ended questions from the assessment across a 5-year time frame to better understand how the girls knew when their counselor was listening and how the SGIE program was helpful. Open-ended questions in research can generate responses that are meaningful to the participant, unanticipated by the interviewer, and often descriptive and contextual in nature (Goodman-Scott et al., 2024; Mack et al., 2005).

Participants

From 2018–2023, 407 girls were referred to SGIE. At the time of referral, girls were between the ages of 5 and 13 years old (M = 8.60) and ranged from kindergarten to sixth grade (M = 3.18). Girls who shared their race at the time of referral (N = 228) identified as American Indian/Native American (.88%, n = 2), Black (79.39%, n = 181), Hispanic (5.7%, n = 13), White (7.89%, n = 18), and multiracial (6.14%, n = 14).

While 407 girls were referred to SGIE, there were fewer qualitative responses included in the data analysis because of variation in assessment administration by the Policy Center, girls’ school attendance rates or changing schools, and missing qualitative data at assessment. Once we accessed the de-identified data and deleted missing qualitative data entries for the two questions analyzed, a total of 107 qualitative responses were recorded for the first research question, “How do you know your counselor listens to you?” and 109 qualitative responses were recorded for the second research question, “How has SGIE been helpful to you?”

Research Team

Prior to engaging in the study, the research team discussed our personal beliefs about effective counseling skills; how clients know whether counselors are listening; and what makes a school-based positive intervention program effective, particularly for girls. Ne’Shaun Borden is a cisgender African American woman from the Southeastern United States. She has been a counselor educator for 5 years and licensed mental health counselor for 10 years with prior professional experience as an elementary school teacher and a school-based mental health professional (SBMHP). Natalie Indelicato is a cisgender multiracial counselor educator and licensed mental health counselor from the Southeastern United States. She has been in the mental health field for 20 years; her research and clinical work have focused on women and girls’ mental health. She has worked closely with the Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center for the past 10 years as a research collaborator and clinical supervisor for student interns. Jamie Root is a White cisgender female second-year student in a Master’s in Clinical Mental Health Counseling program who has a personal and professional interest in adolescent mental health. She has resided in the Southeastern United States for the past 25 years. Lanni Brown is an African American cisgender female second-year student in a Master’s in Clinical Mental Health Counseling program with an interest in counseling justice-involved youth. Throughout the research process, we discussed how our sociocultural positions and experiences in counseling informed our understanding of the analysis. These identities and beliefs about counseling skills and effective program components were referenced in peer discussion during data analysis.

Data Analysis

Girls’ responses to each open-ended question were transcribed and analyzed following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a method of analyzing qualitative data that is transtheoretical and flexible and allows researchers to identify and interpret patterns or themes found within the data using minimally structured organization (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We chose thematic analysis because it allowed us to capture themes based on quality, appropriateness of the information to the research question, and frequency of topics across the 5-year span of data collection. This approach was appropriate given the structure of the data sources and its emphasis on the active involvement of the researcher in the analytic process (Braun & Clarke, 2019).

We conducted a detailed review of all de-identified assessment data, including transcribed responses, for the two qualitative questions, using line-by-line coding to identify significant phrases. To facilitate organization and code tracking, we created a coding platform in Microsoft Excel, allowing researchers to record initial codes, note exemplar quotes, and maintain authentic, developmentally accurate, child-specific language. We interpreted meaning in context, prioritizing the participant’s intent while retaining the authenticity of developmental expression. When girls are referred to the SGIE program, parents provide consent to the assessment along with counseling services, and participants provide assent. Assessment items were administered by trained program staff, separate from counselors directly providing services, whenever possible to minimize social desirability or power influences; however, due to limited staff resources, counselors did administer assessments if other SGIE staff were not available. Additional safeguards included emphasizing confidentiality, administering surveys in private settings within the schools, and clarifying that responses would not affect program participation. Although social desirability may have influenced responses, these procedures enhanced authenticity and strengthened the credibility and trustworthiness of findings.

Independent coding further ensured interpretive rigor, centering girls’ own descriptions. Within the reflexive paradigm, consensus was conceptualized as achieving a shared understanding of patterns and meanings across the data. We collaboratively reviewed transcripts and initial codes, iteratively discussing and refining interpretations until a coherent set of themes and subthemes emerged for each question. These methods align with key standards for reporting qualitative research (O’Brien et al., 2014), including purpose, approach, description of the research team and their roles, data collection context, coding and theme development processes, strategies to enhance trustworthiness and reflexivity, and limitations.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was established by emphasizing transparency in coding decisions, iterative theme development, and critical reflexivity; potential researcher bias was identified through ongoing self-reflection and addressed by maintaining reflexive individual and group note-taking, engaging in peer debriefing, and explicitly acknowledging the researchers’ positionalities in relation to the data. We recognized that our own therapeutic experiences and theoretical orientations could influence our interpretations of participants’ narratives. To mitigate this potential bias, we engaged in reflexivity by discussing our assumptions together, as well as with the Policy Center staff, and how these might shape our understanding of the data. This process involved critically examining our roles as both researchers and clinicians, acknowledging the interplay between our professional identities and the research process. By incorporating reflexive practices, such as individual and group note-taking, peer discussions, and frequent interaction with the Policy Center staff, we aimed to enhance the validity of our interpretations and ensure that the participants’ voices were authentically represented.

Findings

A total of 107 qualitative responses were recorded for the first research question, “How do you know your counselor listens to you?” Girls described how they knew their counselor listened to them in developmentally typical language indicating that they knew counselors were listening by providing eye contact, responding to what they said, answering their questions, helping them problem-solve, being respectful, and paying attention to them. RCT is the theoretical framework of the SGIE program, and girls’ focus on their relationship with their counselor and growth-fostering connections was evident. We identified three major themes: Active Listening, Therapeutic Support, and Authenticity. Major themes, subthemes, and examples from the participants are provided in Table 1.

Table 1

Research Question 1 Themes, Subthemes, and Examples

| Research Question: How Do You Know Your Counselor Listens to You? |

| Theme 1. Active Listening

Fully engaging with the girls through verbal and nonverbal cues and thoughtful responses |

| Subtheme: Nonverbal Encouragers/Body Language |

| “She had her ears on. . . . She would listen to me when I had problems with other girls.”

“She would always look in my eyes.”

“She had her eyes on me, and we had so much fun.”

“She listened to me, it was fun, and we drew pictures together.” |

| Subtheme: Open-Ended Questions |

| “She asks me questions and pays attention to me.”

“She asks what I like about myself.”

“Because she asks how I am doing.” |

| Subtheme: Minimal Encourager |

| “By looking in my eyes or shaking her head.”

“She allows me time to talk.”

“She would say something like ‘okay’ or ‘I get it’ and I knew she was listening to me.”

“When we talk, she would laugh.” |

| Theme 2. Therapeutic Support

A counseling alliance grounded in consistency, reliability, advocacy, and compassionate presence |

| Subtheme: Reliability and Consistency |

| “When I ask her something, she always answers.”

“She is there when I need help.” |

| Subtheme: Advocacy and Problem-Solving |

| “She helps me solve the problems that I have, like when I have a conflict with someone.”

“She would talk to my teacher to help me.” |

| Subtheme: Kindness and Caring |

| “She is friendly and nice.” “I can tell them how I feel in school.”

“When I told her about my problems, she would relate to them.”

“Because if I’m going through something, they’d ask me how I’m doing and care for me.” |

| Theme 3. Authenticity

Building a personal connection to create a counseling experience tailored to each girl’s unique needs |

| “Because they are curious about my life.” “When I cry, she tells me to breathe.”

“Whenever I asked a question, she replied to me.” “She responds to things I say.”

“I listen to her, and she listens to me.” “She has activities just for me.”

“When playing together, she would know stuff about me.”

“Because they respond back when I am telling my story and get more information about it and they comfort.” |

Note. Quotes included are as verbatim as possible from the child participants with light edits as appropriate.

Active Listening

Girls emphasized that they knew their counselor was listening to them when they received eye contact; open-ended questions; and encouragement to share what they were going through at school, at home, and with friends. We identified three subthemes of Active Listening, including nonverbal encouragers and body language (e.g., “She had her ears on . . . ”; “She would always look in my eyes.”); open-ended questions (e.g., “She asks me questions and pays attention to me.”); and minimal encouragers (e.g., “She would say something like ‘okay’ or ‘I get it’ and I knew she was listening to me.”). Girls paid attention to the counselors’ active listening skills to determine whether they were listening, which in turn helped the girls determine whether they could trust them and thus increase their engagement in the relationship.

Therapeutic Support

The girls identified counselors’ investment in building a therapeutic alliance and providing support as indicators of whether their counselors were listening. Three subthemes included Reliability and Consistency, Advocacy and Problem-Solving, and Kindness and Caring. Girls stated that counselors who listened were reliably available when the girls sought them out and consistent in their ability to provide support (e.g., feeling like the counselor “always answers” or “is there when I need help”). Girls shared that part of the listening process included engaging back and forth in problem-solving or determining how to advocate for themselves when they perceived unfair treatment by a friend or teacher (e.g., assisting “when I have a conflict with someone” or “talk[ing] to my teacher to help me”). Finally, girls shared that they felt supported and listened to because of the kindness and caring they received from counselors as well as when counselors were friendly in their interactions (e.g., “Because if I’m going through something, they’d ask me how I’m doing and care for me.”). Girls perceived listening as caring, which deepened trust and relational growth with counselors. They discussed knowing that their counselor was listening because of the caring follow-up questions about how the girl is doing and the counselor’s attunement and responsiveness to the girl’s emotions.

Authenticity

Girls described knowing their counselor was listening to them by the way they responded with genuine interest and authenticity (e.g., the counselor showing signs of “curiosity”). Additionally, girls indicated that they felt listened to when the counselor came to the counseling space with interventions that were individually tailored to their interests and their counselor’s knowledge of them (e.g., “When playing together she would know stuff about me.”). This included playful interventions that were fun for the girl. Girls identified play as a way for the counselor to demonstrate authenticity within the relationship. Girls knew that their counselors were listening to them when there was genuine interest within their exchange (e.g., sincere responsivity, mutual respect).

For the second research question, “How has SGIE been helpful to you?”, we recorded 109 qualitative responses. Overall, girls indicated that the program was helpful and provided a safe, supportive space for participants to express emotions, talk about problems, build coping skills, and receive support. Girls reported that the program helped improve behavior, confidence, focus, and relationships. We identified three major themes: Coping Skill Development; Relationship Building; and having a Supportive and Safe Environment. Major themes, subthemes, and examples from the participants are provided in Table 2 .

Table 2

Research Question 2 Themes, Subthemes, and Examples

| Research Question: What Helps? |

| Theme 1. Coping Skill Development

Building strategies to express emotions, manage academic challenges, and solve problems effectively |

| Subtheme: Emotional Regulation and Expression Skills |

| “It would get all my bad thoughts away, and it would make me happy.”

“Because she taught me a lot of stuff and I use that stuff at home.”

“I used to be bad and now I communicate with others.”

“I’ve learned about saying how I feel.”

“I know it helps me because my mom used to say I was like a robot, but now I’m not.”

“It teaches how to have self-control, and you can talk about stuff that I can’t say to my parents and help me calm down. They care about my issues.”

“Whenever I was going through my dad passing away, coming here and doing fun stuff helped.”

“Helps me keep calm.” |

| Subtheme: Problem-Solving Skills |

| “We get to work stuff out here.”

“If something’s wrong, I have somebody to talk to.”

“They taught me not to get into drama, like when girls are about to fight.” |

| Subtheme: Academic Skills |

| “Made a planner, did more homework, and tried new things.”

“It helps me concentrate on how to work, and it helps me understand if I’m stuck and what I should be doing.”

“We had fun and read books.” |

| Theme 2. Relationship Building

Creating connections that help girls feel seen, valued, and confident in their own strengths |

| Subtheme: Trust |

| “I trust my counselor.” |

| Subtheme: Increased Confidence and Self-Awareness |

| “Helps me feel good about myself and makes me confident.”

“Helped me see myself in a positive light.”

“I have been feeling more confident and comfortable in school.”

“Made new friends and learned things about myself.” |

| Theme 3. Supportive and Safe Environment

Providing a consistent space where girls feel safe to express themselves freely and openly |

| “Helps you with things and helps you calm down.”

“I can talk about my emotions and it’s a safe place where I can work on things.”

“It is calming because I can have a bad day at school but when I go there it’s more calming and relaxing.”

“When I’m angry, I have somewhere to go.”

“I like having girls’ conversation and you get to do a lot of fun things. Helpful because I normally don’t get to do a lot of things with girls.” |

Note. Quotes included are as verbatim as possible from the child participants with light edits as appropriate.

Coping Skill Development

Girls emphasized learning coping skills as one of the primary ways that the program was helpful. We identified three subthemes related to coping skill development: Emotional Regulation and Expression Skills, Problem-Solving Skills, and Academic Support. Girls discussed the value of learning how to better understand their emotions, communicate about how they were feeling, increase strategies for calming themselves, and reframe negative thinking (e.g., “I’ve learned about saying how I feel.”; “It teaches how to have self-control . . . ”). Girls discussed increased emotional expression at school and at home. They associated increased emotional expression and ability to regulate emotions with an improvement in communicating with peers and family members. Girls also disclosed learning how to navigate problems through utilizing school, peers, and home support (e.g., “If something’s wrong, I have somebody to talk to.”). Girls identified learning how to access academic support as a coping skill. They acknowledged that problem-solving and implementing academic and organizational skills improved their overall emotional coping (e.g., success strategies such as “[making] a planner, [doing] more homework,” and “read[ing] books.”).

Relationship Building

Girls described relationship building as a significant benefit of the SGIE program. Subthemes within this theme include Trust and Increased Confidence and Self-Awareness. Girls emphasized cultivating a trusting relationship with their counselor and gaining confidence through the relationship. Girls described the program as helping them feel more positively about themselves, more comfortable at school, and better equipped to handle conflicts. Girls attributed the program to making new friends, discovering more about their interests, and having fun.

Supportive and Safe Environment

The last theme regarding what participants found helpful about the program is the idea that it provides a place that is safe, calm, relaxing, and fun. Overall, the girls felt secure in knowing they had a safe, consistent place to go during the school day to talk about emotions and receive support (e.g., “I can talk about my emotions, and it’s a safe place where I can work on things.”). The data indicate that the program provides a calming and relaxing environment, particularly during or following stressful experiences within the school environment (e.g., relaxing after a “bad day at school” or “when I’m angry”). Additionally, fun activities were mentioned as contributing to positive experiences and feeling a connection with their counselor.

Discussion

Our study results indicate that the SGIE program was well received by program participants. Overall, girls felt that the program was helpful, that their counselors listened to them, and that they could trust their counselors. These findings support the RCT underpinnings of the program design, which emphasize the importance of connection, authenticity, and growth-fostering relationships (Miller, 1976). Active listening reflects mutuality and attunement—core competencies in culturally responsive practice. By providing consistent eye contact, nonverbal encouragers, open-ended questions, and minimal verbal prompts, counselors communicate genuine attention and respect for girls. These behaviors allow girls to feel heard and foster relational trust. In practical terms, counselors demonstrate mutuality by engaging in reciprocal dialogue, attunement by noticing and responding to both verbal and nonverbal cues, and agency by encouraging girls to guide the conversation and share concerns that matter most to them.

Therapeutic support operationalizes culturally responsive behaviors through reliability, advocacy, and caring responsiveness, which are critical for promoting agency and relational safety. Girls recognized listening when counselors consistently made themselves available; assisted with problem-solving; and advocated for girls in contexts where they experienced unfair treatment, such as conflicts with peers or teachers. These actions reflect culturally responsive competencies by attending to systemic inequities while centering the girls’ perspectives. Counselors’ kindness, follow-up inquiries, and emotional responsiveness exemplify attunement, which signals to girls that their emotional experiences are acknowledged and respected. Such behaviors strengthen growth-fostering relationships and enable girls to participate more fully in interventions, reinforcing both empowerment and trust.

Authenticity further underscores culturally responsive practice by highlighting genuine curiosity, individualized interventions, and playful engagement. Counselors who demonstrate authentic interest in each girl’s unique experiences and tailor activities to her preferences convey respect for individuality and support the development of agency. For example, incorporating play or personalized activities not only fosters engagement but also models culturally responsive competencies by creating a safe space where girls can express themselves freely. Together, these three listening themes reflect an integrated approach, ensuring that relational connections are both growth-fostering and equity-centered in under-resourced school contexts.

Implications

Counselor Education

Counselor educators in clinical mental health counseling programs provide counseling trainees with the knowledge and skills to work with individuals across the lifespan. Utilization of traditional, often monocultural, pedagogy may restrict counselor educators in their ability to train counseling students to tackle complex, culture-bound topics (Lertora et al., 2020). Though there now exists increased accountability for clinical mental health counseling programs to teach cultural competence and relational approaches within multicultural foundation courses, limited research exists regarding the implementation of culturally tailored relational processes within technique and skills courses (Lertora et al., 2020). To address this issue, we recommend that counselor educators revise the traditional transcription and recording assignment, which is a hallmark of many counselor training courses. In courses such as Counseling Children and Adolescents or Skills Training, educators could guide students to identify authenticity and mutuality as microskills, integrating these concepts into their practice and reflection.

Current findings highlight the need for educators to go beyond simple definitions toward increasingly practice-based instruction on how to best apply culturally bound relational skills within the counseling relationship. Future exploration of the continued examination of effective skills for counselors-in-training is warranted. For example, broaching grants the counselor the ability to intentionally address the cultural impact on well-being and demonstrates a holistic relational skill (Day-Vines et al., 2007). Additional efforts to attract and retain counseling students from diverse backgrounds have become a growing interest within clinical mental health counseling programs (Purgason et al., 2016) and may assist in an increasingly culturally responsive counseling profession.

Supervision

Often, novice counselors, especially when working cross-culturally with individuals from diverse backgrounds, may unintentionally overuse interventions at the expense of developing rapport with clients. This can also be seen when working with girls who have been labeled as defiant and disrespectful. A potential recommendation for overcoming this barrier is to use modeling within the supervisory relationship. Parallel processes (i.e., the replication of client–counselor dynamics brought into the supervisory relationship) can occur during supervision and are often deemed as important aspects of the process (Tracey et al., 2012). Specifically, supervisors can model RCT tenets in individual and group supervision with counselor trainees. In accordance with current findings, we propose that supervisors utilize RCT concepts while engaging in counselor supervision. A practical approach would be to incorporate an active listening self-assessment, enabling counselors-in-training to become more aware of their own listening skills. Following this, an active listening checklist could be integrated into supervision sessions. Because supervisees who struggle to listen and remain engaged in the supervisory relationship are likely to exhibit similar behaviors with clients, this checklist would provide a targeted way to identify, address, and strengthen those essential skills.

Emphasizing a relational approach, the integration of RCT components into the supervisory environment assists in the creation of a creative, open-minded space, allowing for a transformative experience and acknowledgement of the relationship between client, therapist, and supervisor (Lasinsky, 2020; Lenz, 2014). Lenz (2014) offered a relational–cultural supervision (RCS) model dually promoting the professional growth of both supervisor and supervisee as a two-dimensional approach: essential practices (i.e., RCT skill acquisition) and essential processes (i.e., relational development of supervisee). Through consistent development of RCT skills and practices identified by Lenz (2014) alongside recognition of personal and cultural influences of relationships, via the innate parallel process, the modeling interactions promote the development of competence and growth. Limited research exists applying this specific RCS model, but research supports the overall use of relational models within the supervisory relationship. In their exploration of developmental relational counseling (an integrated model founded on RCT), Duffey et al. (2016) noticed clear disparities between growth-fostering and disconnected supervisory relationships. These findings suggest an increased ability by those in healthy supervisory relationships to approach the client–counselor relationship with empathy and mutuality. Though increased research is needed within supervision literature, it is evident that supervision creates a unique opportunity for supervisors to model and incorporate underpinnings of RCT by focusing on the relationship between the supervisor and trainee through modeling mutual empathy, empowerment, and relational authenticity (Duffey et al., 2016; Lasinsky, 2020; Lenz, 2014).

School-Based Mental Health Professionals

SBMHPs such as mental health counselors, social workers, school psychologists, and school counselors are all tasked with supporting aspects of girls’ wellness within the school setting through counseling, resource sharing, staffing, testing, classroom lessons, and group counseling (Zabek et al., 2023). With limited resources and the often overwhelming responsibilities that come with these roles, various barriers to effective practice may emerge, including feelings of uncertainty on when to begin implementing programming due to time constraints, staff shortages, lack of multidisciplinary communication, and insufficient budgeting (Frey et al., 2022; Zabek et al., 2023). If SBMHPs are unable to implement a curriculum as outlined in this study, they can instead utilize relational, culturally based interventions that have been shown to positively impact adolescent girls. In a review of RCT interventions, Evans and O’Donnell (2024) identified four key characteristics that effective approaches share: mutual empathy, authenticity, empowerment, and opportunities to strengthen and deepen relational connections. The interventions reviewed included psychoeducation groups, expressive arts groups, individual counseling, and equine-assisted therapy, which could be implemented by SBMHPs as appropriate in their settings.

Further, to increase quality of care and reduce barriers, potential connections between school districts and SBMHPs with girl-serving agencies could open access to curriculum like the SGIE, which requires minimum training to implement and relies mostly on the counseling training that professionals have already received. Furthermore, SBMHPs can evaluate the effectiveness of their programs from the girls’ perspectives by utilizing the questions explored in this study as part of their ongoing assessment of services.

Future Directions

Women and girls experience unique, gender-specific realities; therefore, culturally responsive interventions and approaches are needed. Utilizing a qualitative framework allows for a richer understanding of why certain factors (e.g., active listening, therapeutic support, authenticity, coping skill development, relationship building, a supportive and safe environment) elicit a positive, beneficial experience for girls. Our study supplements existing literature by offering insights into effective, culturally responsive program delivery and client outcomes by examining which aspects of counselor interactions were most helpful. Considering the commitment for counselor education programs to continually evolve by adapting to the ever-changing needs of students, clients, and the counseling profession, current findings can be used to inform counselor education training moving forward.

Future research related to counselor training and longitudinal outcome data on girls is warranted. Patino Lydia and colleagues (2014) called for research that examines the effectiveness of the training of graduate- and undergraduate-level counselors. Given that the SGIE program relies heavily on undergraduate and graduate counselor interns to provide program interventions and that these interventions are helpful from the girls’ perspectives, future research should focus on their training to identify which aspects were most helpful for their development in order to replicate this model program in other schools. Also, longitudinal outcome data on the girls participating in the SGIE program would help determine the long-term impact of participating in girl-centered programming.

Limitations

Although this study contributes to the literature on girl-centered programs by adding qualitative data on girls’ perspectives, several limitations should be noted. The use of secondary data posed challenges, as the researchers did not design the original assessment tools, oversee implementation, or participate in data collection. The data were cleaned, organized, and anonymized prior to analysis, which may have introduced gaps affecting representation of all participant perspectives. For instance, although 407 girls were referred to the program between 2018 and 2023, only 107 and 109 qualitative responses were available for analysis for each research question, respectively. Nonresponse and missing data may have introduced bias, as participants who did not respond could differ systematically from those who provided complete data, potentially resulting in differing thematic patterns in girls’ perceptions of counselor listening and program helpfulness. Additionally, opportunities to mitigate nonresponse prospectively (e.g., participant follow-up or additional data collection) were not available. As a result, researchers relied on post hoc approaches, including examining patterns of missing data, utilizing demographics of the number of girls referred to SGIE, and considering the potential limitations when interpreting results. Finally, because the data were collected from a limited number of public schools in one large Southeastern city, the generalizability of findings to other geographic or cultural contexts is limited. Future research should employ strategies to minimize missing data during primary data collection and use analytic techniques such as weighting, multiple imputation, or sensitivity analyses to better account for possible nonresponse bias.

Conclusion

This study directly advances equity and culturally competent care for underserved girls by offering relationally based programs as an effective alternative to exclusionary discipline practices. Additionally, the study offers specific counselor behaviors that foster trust and growth in RCT-informed settings. The authors sought to explore girls’ perspectives on two specific aspects of the SGIE program: how the girls knew their counselors listened to them and which aspects of the program the girls found most helpful. Though the average age of the girls in our study was eight years old, from their developmental perspective, girls were able to identify the importance of active listening, therapeutic alliance and support, trust, and authenticity in the counseling relationship. Further, the girls identified that skill building was one of the most helpful aspects of the program, specifying the value of learning relationships and coping skills in a safe and supportive environment.

Assessing and examining girls’ perspectives on the efficacy of girl-centered programming is critical for improving program delivery and client outcomes. Gathering feedback directly from girls, almost 80% of whom were Black, provides invaluable insights into their experiences and helps identify which aspects of the counseling services are working well and which areas need improvement. Understanding their perspectives ensures that the services are culturally responsive, leading to more effective and relevant interventions. By analyzing girls’ perceptions of progress, outcomes, and overall benefit, researchers can gauge whether the programs are achieving their intended goals. This information is essential for determining the actual efficacy of interventions beyond standardized outcome measures. Girls who feel that their perspectives are valued and acted upon are more likely to remain engaged with the counseling process. By incorporating girls’ feedback into program design and implementation, programs foster a girl-centered, collaborative, and supportive environment, which can improve client retention and engagement. Finally, examining girls’ perspectives can influence policy decisions and funding allocations. Demonstrating that counseling services are valued by girls and are effective can support arguments for continued or increased funding, helping to sustain and expand beneficial programs. This approach enhances the quality of the services provided and promotes a more ethical and responsive practice in counseling. Including girls’ perspectives and prioritizing the development and maintenance of growth-fostering relationships through connection and coping skills is critical to the efficacy of girl-centered programming.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862.

Anderson, K. P., & Ritter, G. W. (2017). Disparate use of exclusionary discipline: Evidence on inequities in school discipline from a U.S. state. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25(49). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.25.2787

Anyon, Y., Jenson, J. M., Altschul, I., Farrar, J., McQueen, J., Greer, E., Downing, B., & Simmons, J. (2014). The persistent effect of race and the promise of alternatives to suspension in school discipline outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.06.025

Baroni, B., Day, A., Somers, C., Crosby, S., & Pennefather, M. (2016). Use of the Monarch Room as an alternative to suspension in addressing school discipline issues among court-involved youth. Urban Education, 55(1), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916651321

Bradshaw, C. P., Mitchell, M. M., & Leaf, P. J. (2009). Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on student outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12(3), 133–148.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300709334798

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Brobbey, G. (2017). Punishing the vulnerable: Exploring suspension rates for students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(4), 216–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451217712953

The Brookings Institution. (2023). School discipline in America. https://www.brookings.edu/tags/school-discipline-in-america/

California Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. (2023). https://pbisca.org

Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports. (2024). https://www.pbis.org

Day-Vines, N. L., Wood, S. M., Grothaus, T., Craigen, L., Holman, A., Dotson-Blake, K., & Douglass, M. J. (2007). Broaching the subjects of race, ethnicity, and culture during the counseling process. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00608.x

Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center: See the Girl. Mission, vision, values. https://www.seethegirl.org/about-us/mission/

Duffey, T., Haberstroh, S., Ciepcielinski, E., & Gonzales, C. (2016). Relational-cultural theory and supervision: Evaluating developmental relational counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12099

Evans, K., & O’Donnell, K. (2024). Relational cultural theory and intervention approaches with adolescent girls: An integrative review. Affilia, 40(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/08861099241271296

Frey, A. J., Mitchell, B. D., Kelly, M. S., McNally, S., & Tillett, K. (2022). School-based mental health practitioners: A resource guide for educational leaders. School Mental Health, 14, 789–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09530-5

Gage, N. A., Grasley-Boy, N., Peshak George, H., Childs, K., & Kincaid, D. (2018). A quasi-experimental design analysis of the effects of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports on discipline in Florida. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 21(1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300718768208

Goodman-Scott, E., Perez, B. M., Dillman Taylor, D., & Belser, C. T. (2024). Youth-centered qualitative research: Strategies and recommendations. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 10(2), 66–84.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2024.2360681

Hernandez-Melis, C., Fenning, P., & Lawrence, E. (2016). Effects of an alternative to suspension intervention in a therapeutic high school. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60(3), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2015.1111189

Jordan, J. V. (2017). Relational–cultural theory: The power of connection to transform our lives. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56(3), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12055

Kang-Brown, J., Trone, J., Fratello, J., & Daftary-Kapur, T. (2013). A generation later: What we’ve learned about zero tolerance in schools. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/zero-tolerance-in-schools-policy-brief.pdf

Lamont, J. H., Devore, C. D., Allison, M., Ancona, R., Barnett, S. E., Gunther, R., Holmes, B., Lamont, J. H., Minier, M., Okamoto, J. K., Wheeler, L. S. M., & Young, T. (2013). Out-of-school suspension and expulsion. Pediatrics, 131(3), e1000–e1007. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3932

Lasinsky, E. E. (2020). Integrating relational-cultural theory concepts and mask-making in group supervision. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 15(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2019.1640153

Lenz, A. S. (2014). Integrating relational-cultural theory concepts into supervision. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 9(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2013.864960

Lertora, I. M., Croffie, A., Dorn-Medeiros, C., & Christensen, J. (2020). Using relational cultural theory as a pedagogical approach for counselor education. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 15(2), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2019.1687059

LiCalsi, C., Osher, D., & Bailey, P. (2021). An empirical examination of the effects of suspension and suspension severity on behavioral and academic outcomes. American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/NYC-Suspension-Effects-Behavioral-Academic-Outcomes-August-2021.pdf

Mack, N., Woodsong, C., MacQueen, K. M., Guest, G., & Namey, E. (2005). Qualitative research methods: A data collector’s field guide. Family Health International. https://www.fhi360.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Qualitative-Research-Methods-A-Data-Collectors-Field-Guide.pdf

Miller, J. B. (1976). Toward a new psychology of women. Beacon Press.

Novak, A. (2018). The association between experiences of exclusionary discipline and justice system contact: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.04.002

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

Patino Lydia, V., Baker, P., Jenkins, E., & Moore, A. (2014). Girl matters: It’s elementary evaluation report. Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center. https://www.seethegirl.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/GMIE-Pilot-Evaluation-Report.pdf

Patino Lydia, V., & Moore, A. (2015). Breaking new ground on the first coast: Examining girls’ pathways into the juvenile justice system. Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center. https://www.seethegirl.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Girls-Pathways.pdf

Purgason, L. L., Avent, J. R., Cashwell, C. S., Jordan, M. E., & Reese, R. F. (2016). Culturally relevant advising: Applying relational-cultural theory in counselor education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12101

Rappaport, M. (2014). Building bridges: An alternative to school suspension. Bridges.

Ryberg, R., Her, S., Temkin Cahill, D., & Harper, K. (2021). Despite reductions since 2011-12, Black students and students with disabilities remain more likely to experience suspension. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/despite-reductions-black-students-and-students-with-disabilities-remain-more-likely-to-experience-suspension

Skiba, R. J. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools?: An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.9.852

Skiba, R. J., Arredondo, M. I., & Williams, N. T. (2014). More than a metaphor: The contribution of exclusionary discipline to a school-to-prison pipeline. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(4), 546–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2014.958965

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelson, C. M., Scott, T., Liaupsin, C., Sailor, W., Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., III, Wickham, D., Wilcox, B., & Ruef, M. (2000). Applying positive behavior support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(3), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/109830070000200302

Tracey, T. J. G., Bludworth, J., & Glidden-Tracey, C. E. (2012). Are there parallel processes in psychotherapy supervision? An empirical examination. Psychotherapy, 49(3), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026246

U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights. (2023). Student discipline and school climate in U.S. public schools: 2020–21 Civil Rights Data Collection. https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-discipline-school-climate-report.pdf

Vanderhaar, J., Munoz, M., & Petrosko, J. (2014). Reconsidering the alternatives: The relationship between suspension, disciplinary alternative school placement, subsequent juvenile detention, and the salience of race. Journal of Applied Research on Children, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.58464/2155-5834.1218

Welsh, R. O., & Little, S. (2018). The school discipline dilemma: A comprehensive review of disparities and alternative approaches. Review of Educational Research, 88(5), 752–794. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318791582

Wymer, B., Guest, J. D., & Barnes, J. (2024). A content analysis of recent qualitative child and adolescent counseling research and recommendations for innovative approaches. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 10(2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2024.2357520

Zabek, F., Lyons, M. D., Alwani, N., Taylor, J. V., Brown-Meredith, E., Cruz, M. A., & Southall, V. H. (2023). Roles and functions of school mental health professionals within comprehensive school mental health systems. School Mental Health, 15, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09535-0

Ne’Shaun J. Borden, PhD, LMHC (FL), is an assistant professor and program director at Jacksonville University and was a 2019 Doctoral Fellow in Mental Health Counseling with the NBCCF Minority Fellowship Program. Natalie A. Indelicato, PhD, LMHC, is a professor at Jacksonville University. Jamie F. Root, BSc, RMCHI, is a registered mental health counseling intern in Florida. Lanni Brown, BS, is a counseling student at Jacksonville University. The authors would like to acknowledge the Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center for partnering to conceptualize this project and provide the de-identified program data used for analysis. Correspondence may be addressed to Ne’Shaun J. Borden, 2800 University Blvd. N., Jacksonville, FL 32211, nborden@ju.edu.

Aug 20, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 3

Christian D. Chan, Camille D. Frank, Melisa DeMeyer, Aishwarya Joshi, Edson Andrade Vargas, Nicole Silverio

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) communities have faced a history of discriminatory incidents with deleterious effects on mental health and wellness. Compounded with other historically marginalized identities, LGBTQ+ people of color continue to experience disenfranchisement, inequities, and invisibility, leading to complex experiences of oppression and resilience. Moving into later stages of life span development, older adults of color in LGBTQ+ communities navigate unique nuances within their transitions. The article addresses the following goals to connect relational–cultural theory (RCT) as a relevant theoretical framework for counseling with older LGBTQ+ adults of color: (a) explication of conceptual and empirical research related to older LGBTQ+ adults of color; (b) outline of key principles involved in the RCT approach; and (c) RCT applications in practice and research for older LGBTQ+ adults of color.

Keywords: relational–cultural theory, theoretical framework, older adults, LGBTQ+, people of color

Multiple forms of oppression have been historically documented across conceptual and empirical literature for the broad spectrum of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) communities across the life span (Chan, 2018; Chan & Erby, 2018; Meyer, 2014, 2016; Singh, 2013). Further, Black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) have experienced multiplicative deleterious effects combined with psychosocial factors that culminate in racial discrimination and marginalization (David et al., 2019; Sue et al., 2019). Oppression for BIPOC communities and LGBTQ+ communities often cascades across the life span and culminates in a number of health disparities (Choi & Meyer, 2016; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2015, 2017). Given these complex dimensions with social identities, researchers have expanded their focus to examine social conditions, such as education and health care, to accentuate the needs of older LGBTQ+ adults of color (Howard et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2017). Although researchers have given more attention to LGBTQ+ BIPOC (e.g., Jackson et al., 2020; Velez et al., 2019), older adults within these communities are typically omitted in practice, advocacy, and policy (Kimmel, 2014; Porter et al., 2016; Seelman et al., 2017; South, 2017). Combined with this pattern of exclusion, older LGBTQ+ adults of color are forced to navigate a dearth of resources and complicated climates that fail to properly recognize multiple overlapping forms of racism, heterosexism, genderism, and ageism (Kim et al., 2017; Woody, 2014). Within the counseling profession, gaps in culturally responsive services and advocacy combine with alarming rates of barriers, health disparities, and underutilization of mental health services (Chan & Silverio, in press; Kim et al., 2017; Lecompte et al., 2021).

Relational–cultural theory (RCT) operates as a cohesive and modern theoretical approach founded on values of feminism, equity, empowerment, and social justice (see Comstock et al., 2008; Duffey & Trepal, 2016; Hammer et al., 2016; Kress et al., 2018). Instances of disconnection can be prominent at older adult stages of life (Seelman et al., 2017), and RCT offers a purposeful framework for increasing relational awareness (Hammer et al., 2016), relational growth (Kress et al., 2018), and investment in professional counseling relationships (Fullen et al., 2020). Given developmental concerns and life span transitions, older LGBTQ+ adults of color can remain disconnected from family, society, institutional resources, and professional counselors (Jones et al., 2018; Mereish & Poteat, 2015; Seelman et al., 2017). Using an RCT approach accounts for these factors and increases the awareness of disconnections between people and others in their environment (Hammer et al., 2016; Singh & Moss, 2016). Because of its emphasis on relationships, RCT’s focus on mutually fostering growth and dismantling oppression provides a platform for professional counselors to integrate the themes of equity, social justice, and feminism into counseling practice with older LGBTQ+ adults of color (Rausch & Wikoff, 2017; Singh et al., 2020). RCT demonstrates that intersections of social identities mirror several overlapping forms of oppression and hierarchies of power (Addison & Coolhart, 2015; Chan & Erby, 2018; Hammer et al., 2016).

Within this conceptual framework, we intentionally use LGBTQ+ communities to inclusively highlight communities featured across the spectrum of sexuality, affectional identity, and gender identity (Griffith et al., 2017). As counselors address the intersections among social identities, applying philosophical underpinnings of RCT equips them to tackle cultural, social, and contextual barriers that disconnect older LGBTQ+ people of color from society, resources, and health care access. Consequently, this article entails a three-pronged approach: (a) an overview of extant conceptual and empirical research relevant for older LGBTQ+ adults of color; (b) in-depth illustration of key principles within the RCT approach; and (c) RCT applications for counseling practice and research to support older LGBTQ+ adults of color.

Intersections of Older Adults, LGBTQ+ Communities, and Communities of Color

Scholars across disciplines (e.g., psychology, social work, counseling, sociology, education) continue to explore intersections of racial and ethnic identities in confluence with sexuality, affection, and gender identity (Chan & Erby, 2018; Jackson et al., 2020; Van Sluytman & Torres, 2014). Researchers can ostensibly benefit from a gerontological focus to critically examine social conditions and structures sustained by ageism (Chaney & Whitman, 2020; Kim et al., 2017). The lack of attention to gerontology, ageism, or older adults within LGBTQ+, racial, and ethnic identity research has further underscored the impact of health disparities and social determinants of health (e.g., education, economic resources, career, income) that precipitate an underutilization of mental health services and health care, specifically among LGBTQ+ people of color (Choi & Meyer, 2016; Du & Xu, 2016; Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2014; Rowan & Giunta, 2016; Seelman et al., 2017). Kim and colleagues (2017) specifically observed that race and ethnicity have been historically excluded as variables and outcomes in LGBTQ+ older adult research. Building further on this gap, Woody’s (2014) study of African American LGBT elders exemplified the need to address these intersections of identities. In the study, Woody noted that African American LGBT elders consistently faced conflicts in negotiating ethnic and spiritual values together with sexual and gender identities. Outside of oppressive circumstances, older adults already face realities associated with the aging process, health concerns, maintaining an economic standard of living, retirement, and housing barriers related to developmental life tasks and the stages of older adulthood (Brennan-Ing et al., 2014; Choi & Meyer, 2016; Porter et al., 2016). Several of these concerns coincide with a consistent gap in culturally responsive counseling practices focused on older adults (Chan & Silverio, in press; Fullen, 2018) and the call to action by Fullen and colleagues (2019) to broaden research evidence in gerontological counseling.

Health Disparities

As gerontological and health researchers attempt to shed light on the experiences of older LGBTQ+ adults of color, overall trends continue to reveal cultural, social, psychological, and physical implications of intersecting forms of oppression. In fact, a study by Kim et al. (2017) documented that African American LGBT elders faced higher rates of lifetime discrimination, which adversely affected their physical and mental health. Similarly, incidents that contribute to the lack of identity affirmation, community networks, and social support exacerbate a number of health disparities and adverse outcomes of mental health (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Seelman et al., 2017; Woody, 2014, 2015). Consistent with patterns in health disparities research, oppression tends to serve as a catalyst for higher prevalence of suicidality among older LGBTQ+ adults of color (Choi & Meyer, 2016; Meyer, 2014, 2016). In fact, Fullen and colleagues (2018) noted that internalized ageism can predispose older adults to a myriad of mental health issues, symptoms, and increased rates of suicidal ideation. According to Seelman (2019), the combination of responding to discrimination along with barriers to access can significantly increase the mortality rate for older LGBTQ+ adults of color. Conversely, the preservation of cultural identity (Fullen, 2016) and identity affirmation (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017; Howard et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2017) buffers the effects of oppression and encourages older LGBTQ+ adults of color to seek help and health care.

Older LGBTQ+ adults of color also face disproportionate access to resources, especially adequate and LGBTQ-affirming health care services (Hinrichs & Donaldson, 2017; Kimmel, 2014). Among the variety of health conditions tied to the aging process, the risk of HIV increases for older LGBTQ+ adults of color as a result of psychosocial factors, such as poverty, stigma, marginalization, and lack of education (Bower et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2018; Karpiak & Brennan-Ing, 2016; Yarns et al., 2016). Many of these barriers can be traced to the marginalization attached to ageism, classism, racism, genderism, and heterosexism (Brennan-Ing et al., 2014; Robinson-Wood & Weber, 2016). During this stage, older LGBTQ+ adults of color face drastic changes to mental health based on cumulative interactions with societal stigma and internalized heterosexism and genderism (Correro & Nielson, 2020; Yarns et al., 2016). Consistently responding to discrimination can eventually culminate in a variety of mental health symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression) or mental exhaustion (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2014; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013).

Social Isolation, Grief, and Loss

Compounded with multiple overlapping forms of oppression, older LGBTQ+ adults of color can have a multifaceted experience of social isolation and loss as they transition into the stages of older adulthood (Dzierzewski, 2014). Although older adults generally experience grief and loss as part of the transition in aging (Chaney & Whitman, 2020; Kampfe, 2015), these experiences are heightened for older LGBTQ+ adults of color as an outcome of navigating racism, heterosexism, and genderism (Bockting et al., 2016; Woody, 2014, 2015). The loss of family, friends, social networks, and intimate partners for older LGBTQ+ adults of color can converge with an overall lack of affirmation and heighten experiences of racial, sexual, and gender discrimination (Seelman et al., 2017). Instances of isolation and loss are pervasive because of the confluence of racism and heterosexism converging in this stage of the life span (Woody, 2015). Woody’s (2015) study noted that older African American lesbian women cited the proliferation of racism as a more prominent issue than their experiences with other forms of oppression (e.g., heterosexism). Compounding these losses, barriers to housing and the likelihood of eviction for older LGBTQ+ adults of color can amplify feelings of displacement from communities and society (Brennan-Ing et al., 2014; Robinson-Wood & Weber, 2016).

Additionally, older LGBTQ+ adults of color consistently contend with coming out across the life span (Hinrichs & Donaldson, 2017; Mabey, 2011). Experiences of coming out and self-disclosure of these social identities can be complex because of the loss of connections, fear of rejection, and incivility from trusted communities of support (Dzierzewski, 2014; Woody, 2014; Yarns et al., 2016). Complicating the range of concerns within the older adult stages, the chronic effects of marginalization can increase risk factors for substance use and addictions as coping mechanisms for older LGBTQ+ adults of color (Bryan et al., 2017; Veldhuis et al., 2017). Substance use and addictions have become a more visible crisis facing these communities, and they can combine with the risks of displacement from social supports and vital community resources (Brennan-Ing et al., 2014; Cloyes, 2016; Rowan & Giunta, 2016).

The Model of Relational–Cultural Theory (RCT)

RCT can be used by counselors to reflect experiences with societal forces of oppression (Singh & Moss, 2016) and social determinants tied to health, connection, and wellness (Hammer et al., 2016). RCT has surfaced as an applicable theoretical approach for older LGBTQ+ adults of color with the most recent uptick of research and scholarship (Mereish & Poteat, 2015; Singh et al., 2020). Given the core values of RCT generated with social context, authenticity, connection, and social justice, the approach addresses needs, social conditions, barriers, and marginalization experiences for older LGBTQ+ adults of color (Chan & Erby, 2018; Rausch & Wikoff, 2017; Singh & Moss, 2016). The history of RCT provides context for current practice and underscores the foundation of a relationally centered paradigm. The concepts of relational images, growth-fostering relationships, and the central relational paradox inform counseling with clients experiencing such positions of resilience and oppression (Duffey & Trepal, 2016). The relevance of an RCT approach to a number of client concerns has gained traction as counseling professionals are charged with implementing more culturally responsive approaches (Flores & Sheely-Moore, 2020; Haskins & Appling, 2017; Singh et al., 2020). To support RCT’s utility, a recent review from Lenz (2016) concluded that empirical research has consistently supported RCT constructs and its use as a framework for understanding client experiences.

Key Principles

Originally positioned within Miller’s (1976) Five Good Things, the principles of RCT in counseling practice have imminently evolved into a robust theoretical framework centered in (a) clarity of self and others, (b) creativity, (c) zest, (d) empowerment, and (e) connection. As Jordan (2000) provided in an influential comprehensive overview of RCT, the main themes for the framework can be summarized in four distinct areas. The first principle posits that people are generally oriented toward growing individually and collectively within their relationships across the life span (Jordan, 2010, 2017), which results in growth-fostering relationships (Miller, 1976; Miller & Stiver, 1997). Secondly, growth-fostering relationships require mutuality, which is defined as mutual empathy and mutual empowerment (Jordan, 2010; Kress et al., 2018). Because of mutuality in growth-fostering relationships, assessing growth of individuals and relationships is contingent on authenticity, or individual genuineness, as the third component (Duffey & Trepal, 2016; Jordan, 2000, 2017). Individuals’ abilities to represent themselves authentically in their relationships can be a function of this growth (Duffey & Somody, 2011; Hammer et al., 2016). Because authenticity underpins mutuality and growth-fostering relationships, the fourth area of RCT involves the central relational paradox. The central relational paradox illustrates how the fear of vulnerability reduces authentic expression and maintains disconnections, despite a proclivity for connection with others (Miller & Stiver, 1997). When mutuality and authenticity are prioritized, professional counselors using RCT assume that conflict can be a normal dynamic in the relationship, in which high-level growth in the relationship involves the ability to actively address this relational difference (Comstock et al., 2008; Duffey, 2007; Jordan & Carlson, 2013). The primary function of RCT in counseling then focuses on building relational competence (Kress et al., 2018; Singh & Moss, 2016).

To build further on these constructs, several researchers have provided a foundation for using RCT with older LGBTQ+ adults of color (Flores & Sheely-Moore, 2020; Mereish & Poteat, 2015; Singh & Moss, 2016). There are cultural, social, and political implications underlying the connection between RCT and older LGBTQ+ adults of color. For example, older LGBTQ+ adults of color are forced to contend with multiple points of disconnection from society through histories of racism, genderism, heterosexism, and ageism. Although multiple forms of oppression can disconnect historically marginalized communities, ageism is distinct because it focuses on marginalizing life transitions (Chaney & Whitman, 2020; Fullen, 2018). Consequently, older LGBTQ+ adults of color experience a heightened sense of disconnection due to grief and loss, isolation, and lack of social support. Older LGBTQ+ adults of color may likely encounter disconnections from a society that fails to affirm their identities, which precipitates a disconnection to self and underutilization of community resources (Kim et al., 2017; Seelman et al., 2017). Older LGBTQ+ adults of color may face a hierarchy of power and privilege that would impair an authentic connection and movement toward mutuality (Duffey & Somody, 2011; Hammer et al., 2016; Jordan, 2010). One outcome of this hierarchy is the notion of relational images, in which historically marginalized individuals feel forced to conform to a privileged identity. For instance, an older lesbian woman of color as a client may hold controlling relational images of help-seeking when interacting with a White male counselor possessing multiple privileged identities. In this instance, the client might internalize stereotypes and biases imposed by the counselor. Using RCT explicitly addresses these controlling relational images to challenge the dominant discourse, increase authenticity, and empower connection (Hammer et al., 2016; Haskins & Appling, 2017).

RCT as a Lens for Conceptualization and Intervention

The following hypothetical case example underscores the theoretical underpinnings of RCT and illustrates applications of RCT in clinical practice. This case example illustrates a variety of RCT principles to help counselors connect potential experiences of older LGBTQ+ adults of color and the complexity of intersecting forms of oppression. With the overall case study presented, Table 1 synthesizes key principles and applications, supplemental literature, and relevant portions of the case example.

Case Formulation

Chris, 72 years old, and Hector, 71 years old, have been partnered for 27 years. Chris is a Mexican American bisexual male born in the United States with the pronouns he, him, and his. Hector is a multi-heritage Asian American gay man of Filipino, Norwegian, and Colombian descent with the pronouns he, him, and his. Both Chris and Hector are Catholic and living without disabilities. Chris retired as a social worker when he reached 65 years of age while Hector chose to continue working as a university professor until the previous year at age 70. Chris and Hector recently relocated to live with Chris’s daughter from a previous marriage, Ella. Ella welcomed both Chris and Hector into her home as family. Upon the transition to their retirement phase, Chris and Hector began spending most of their time at home, and Ella has checked in with them regularly. They took on new hobbies, including painting, and focused more of their time on relaxation and leisure. Recently, Chris became increasingly concerned with Hector’s forgetfulness. Chris became worried about bringing him to social events, as Hector was “absentminded.” Although initially excited about the move, Chris realized Hector was struggling with all of the new issues that emerged from the transition. Chris thought about discussing the concerns with his daughter, but he did not want to worry her or embarrass Hector. Chris has felt conflicted about his own internal and external responses. Over the past few months, Chris has felt increasingly isolated and disconnected with Hector while recognizing a decreased lack of enjoyment.

Table 1

RCT Applications to Case Example

| Application |

Supporting Literature |

Relevance to Case Example |

| Connection is essential to existence. |

Duffey & Somody, 2011; Lenz, 2016; Walker & Rosen, 2004 |

Practitioners can identify the possible connections Chris and Hector have with each other and with their family. In addition, practitioners can also cite the connection they have with the clients Chris and Hector. Practitioners can particularly note the disconnect they have experienced as society has emerged with transitions and multiple overlapping forms of oppression. |

| Growth-fostering relationships result in the Five Good Things: clarity of self and others, creativity, zest, empowerment, and connection.

|

Miller, 1976; Miller & Stiver, 1997; Duffey, 2007; Duffey et al., 2009; Duffey & Somody, 2011; Hammer et al., 2014

|

Practitioners can work with Chris and Hector to search for strengths and reinvigorate their energy in each other during this transition and stage of their lives. Although Chris and Hector initially struggled with the transition, practitioners can ascertain new types of hobbies and activities they can create together. Such creative activities might elicit more nuanced meaning. Practitioners can also highlight the methods and actions in which Chris and Hector have been resilient in the face of adversity in association with societal and interpersonal discrimination. |