Barriers to Seeking Counseling Among a National Sample of U.S. Physicians: The Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value Scale

Michael T. Kalkbrenner, Shannon Esparza

Physicians in the United States are a client population facing increased risks for mental distress coupled with a reticence to seek professional counseling. Screening tools with valid scores have utility for helping counselors understand why prospective client populations who might benefit from counseling avoid seeking services. The Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value (RFSV) Scale is a screener for measuring barriers to counseling. The primary aims of the present study were to validate RFSV scores with physicians in the United States and to investigate demographic differences in physicians’ RFSV scores. Results revealed that the RFSV Scale and its dimensionality were estimated sufficiently with a national sample of physicians (N = 437). Physicians’ RFSV scores were a significant predictor (p = .002, Nagelkerke R2 = .05) of peer-to-peer referrals to counseling. We also found that male physicians and physicians with help-seeking histories were more sensitive to barriers to counseling than female physicians and physicians without help-seeking histories, respectively. Recommendations for how counselors can use the RFSV Scale when working with physician clients are provided.

Keywords: Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value Scale; counseling; barriers to counseling; help-seeking; physicians

Because of the particularly stressful nature of their work, coupled with the pressure in medical culture to not display psychological vulnerability (Linzer et al., 2016), physicians in the United States must be vigilant about their self-care. Physicians are responsible for treating over 300 million patients in the United States, which can lead to elevated psychological distress that may undermine the quality of patient services and physicians’ personal well-being (Walker & Pine, 2018). Attending personal counseling is associated with a number of personal and professional benefits for physicians (Melnyk et al., 2020). However, a stigma toward seeking counseling and other mental health support services exists in the U.S. medical culture (Dyrbye et al., 2015). Lobelo and de Quevedo (2016) found that physicians are attending counseling at lower rates since 2000, with approximately 40%–70% attending counseling before the year 2000 and only 12%–40% after 2000. One of the next steps in this line of research is gaining a better understanding of barriers to counseling, including reasons why physicians are reluctant to attend.

Screening tools with valid scores are one way to understand why individuals are reticent to attend counseling (Goldman et al., 2018). For example, the Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value (RFSV) Scale is a screening tool with rigorously validated scores for measuring barriers to counseling (Kalkbrenner et al., 2019). Scores on the RFSV Scale have been validated with seven different normative samples since 2018, including adults in the United States (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018), mental health counselors (Kalkbrenner et al. 2019), counselors-in-training (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2019), college students attending a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI; Kalkbrenner et al., 2022), and STEM students (Kalkbrenner & Miceli 2022).

At the time of this writing, RFSV scores have not been validated with a normative sample of physicians. Validity evidence of test scores can fluctuate between normative samples (American Educational Research Association [AERA] et al., 2014; Lenz et al., 2022). Accordingly, counseling practitioners, researchers, and students have a responsibility to validate scores with untested populations before using the test in clinical practice or research (Lenz et al., 2022). Validating RFSV scores with a national sample of U.S. physicians may provide professional counselors with a clinically appropriate screening tool for ascertaining what barriers contribute to physicians’ reluctance to attend counseling services. Identifying barriers to counseling within this population may also promote efforts to increase physicians’ support-seeking behaviors (Mortali & Moutier, 2018).

Barriers to Counseling

Counseling interventions provide physicians with protective factors such as promoting overall health and wellness (Major et al., 2021) and decreasing emotional exhaustion associated with burnout (Wiederhold et al., 2018). Despite these correlations, Kase et al. (2020) found that although 43% of a sample of U.S. pediatric physicians had access to professional counseling and support groups, only 17% utilized these services. Participants cited barriers to attending counseling, including inconvenience, time constraints, preference for handling mental health issues on their own, and perceiving mental health services as unhelpful.

A significant barrier contributing to U.S. physicians’ reticence to attend counseling is the influence of medical culture which reinforces physician self-neglect and pressure to maintain an image of invincibility (Shanafelt et al., 2019). This pressure can begin as early as medical school and may lead to a decreased likelihood of seeking counseling, as medical students who endorsed higher perceptions of public stigma within their workplace culture perceived counseling as less efficacious and considered depression a personal weakness (Wimsatt et al., 2015). An association of frailty with mental health diagnoses and treatment may be driven by incongruences in medical culture between espoused values and actual behaviors, such as teaching that self-care is important, yet practicing excessive hours, delaying in seeking preventive health care, and tolerating expectations of perfectionism (Shanafelt et al., 2019). Such hidden curricula may perpetuate the stigma of seeking mental health treatment, which is considered a primary driver of suicide in the health care workforce (American Hospital Association [AHA], 2022).

In addition to the barrier presented by medical culture, the stigmatization and negative impact on licensure of receiving a diagnosis also discourages physicians from seeking care (Mehta & Edwards, 2018). Almost 50% of a sample of female U.S. physicians believed that they met the criteria for a mental health diagnosis but had not sought treatment, citing reasons such as a belief that a diagnosis is embarrassing or shameful and fear of being reported to a medical licensing board (Gold et al., 2016). It is recommended best practice for state medical licensing boards to phrase initial and renewal licensure questions to only inquire about current mental health conditions, to ask only if the physician is impaired by these conditions, to allow for safe havens, and to use supportive language; yet in a review of all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and four U.S. territories, only three states’ or territories’ applications met all four conditions (Douglas et al., 2023). Thus, it is unsurprising that out of a sample of 5,829 U.S. physicians, nearly 40% indicated reluctance to seek formal care for a mental health condition because of licensure concerns (Dyrbye et al., 2017). The barriers of medical culture and its expectations, stigma, and diagnosis are consequential; further research is needed given the pressure physicians may experience to remain silent on these issues (Mehta & Edwards, 2018).

Demographic Differences

A number of demographic variables are related to differences in physicians’ mental health and their attitudes about seeking counseling (Creager et al., 2019; Duarte et al., 2020). For example, demographic differences such as gender and ethnoracial identity can add complexity to physicians’ risk of negative mental health outcomes (Duarte et al., 2020). Sudol et al. (2021) found that female physicians were at higher risk of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion than male physicians, while physicians from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds were more likely to report burnout than White physicians. Gender identity can also affect help-seeking behavior, as female physicians are more likely than male physicians to utilize social and emotional supports and less likely to prefer handling mental health symptoms alone (Kase et al., 2020). Work setting is another demographic variable that is associated with physicians’ mental health wellness, as Creager et al. (2019) identified lower burnout and stress rates among physicians working in private practice than those working in non–private practice settings.

Help-seeking history has become a more frequently examined variable in counseling research, often categorized into two groups: (a) individuals who have attended at least one session of personal counseling or (b) those who have never sought counseling (Cheng et al., 2018). This demographic variable is especially important when evaluating the psychometric properties of screening tools for physicians, who encounter numerous obstacles to accessing counseling services. Help-seeking history is related to more positive attitudes about seeking counseling, as Kevern et al. (2023) found that 80% of a sample of U.S. resident physicians who attended mental health counseling reported their sessions increased their willingness to attend counseling. These collective findings suggest demographic variables such as gender, ethnoracial identity, work setting, and help-seeking history may impact physicians’ mental health and their sensitivity to barriers to attending counseling and thus warrant further investigation.

The Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value Scale

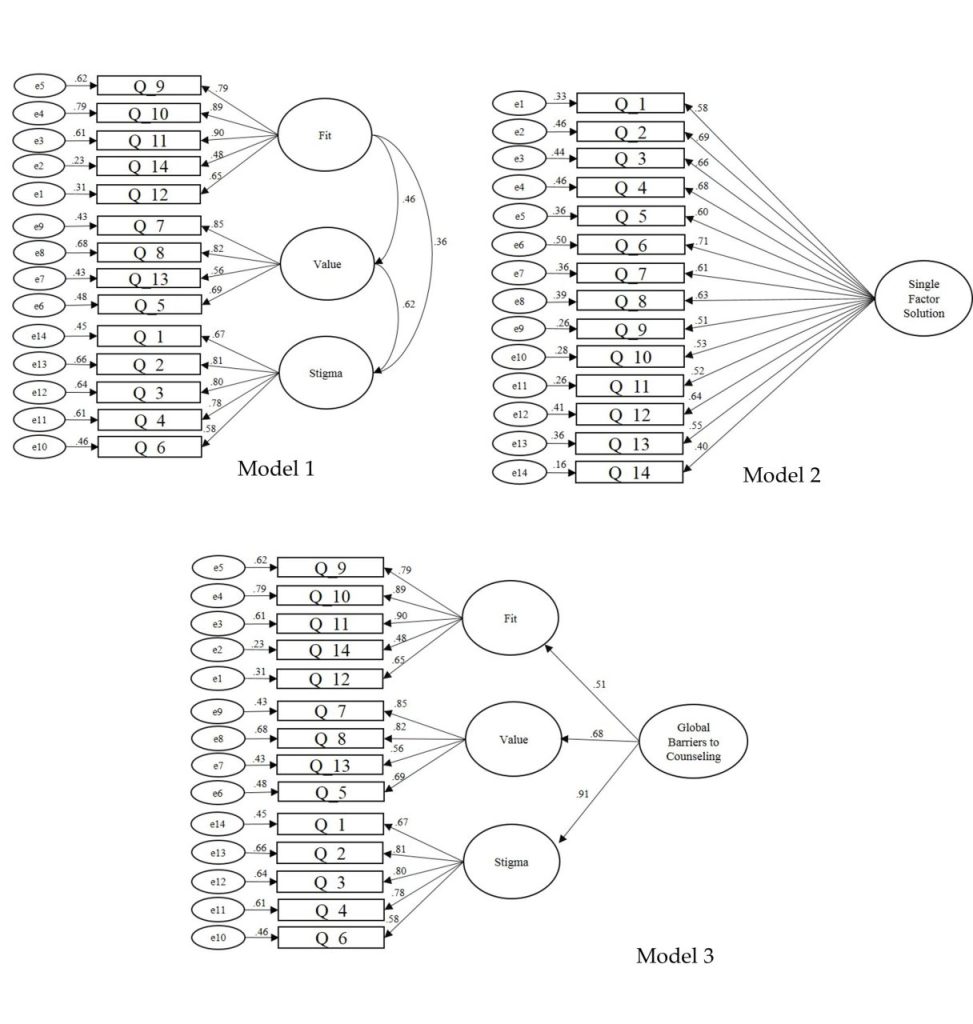

Neukrug et al. (2017) developed and validated scores on the original 32-item Fit, Stigma, and Value (FSV) Scale with a sample of human service professionals in order to appraise barriers to attending personal counseling. The FSV subscales assess sensitivity to three potential barriers to counseling attendance, including fit, the extent to which a respondent trusts the counseling process; stigma, the feelings of shame or embarrassment associated with attending counseling; and value, the perceived benefit of being in counseling. Kalkbrenner et al. (2019) also developed and validated scores on a briefer 14-item version of the FSV Scale (the RFSV Scale), that contains the original three subscales. Additionally, Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2019) identified a higher-order factor, the Global Barriers to Counseling Scale, which is the composite score of the RFSV’s Fit, Stigma, and Value single-order subscales.

Integrative Behavioral Health Care

Mental health challenges and attitudes toward seeking support are shaped by both individual (microsystemic) and broader societal (macrosystemic) factors, making it impossible for a single discipline to address these issues (Lenz & Lemberger-Truelove, 2023; Pester et al., 2023). As a result, the counseling profession is increasingly adopting interdisciplinary collaboration models, in which mental health professionals work together to deliver holistic care to clients or patients. Emerging research highlights interventions aimed at reducing barriers to accessing counseling services (e.g., Lannin et al., 2019). However, the complex interplay of ecological factors influencing mental health distress and service utilization makes evaluating these interventions challenging. Accordingly, counselors and other members of interdisciplinary teams need screening tools with valid scores to help determine the effectiveness of such interventions.

The primary aims of the present study were to validate RFSV scores with a national sample of physicians in the United States and to investigate demographic differences in physicians’ RFSV scores. The validity and meaning of latent traits (i.e., RFSV scores) can differ between different normative samples (AERA, 2014; Lenz et al., 2022). RFSV scores have not been normed with physicians. Accordingly, testing for factorial invariance of RFSV scores is a pivotal next step in this line of research. In other words, the internal structure validity of RFSV scores must be confirmed with physicians before the scale can be used to measure the intended construct. Although a number of different forms of validity evidence of scores exists, internal structure validity is a crucial consideration when testing the psychometric properties of an inventory with a new normative sample (AERA, 2014; Lenz et al., 2022). If RFSV scores are validated with a national sample of U.S. physicians, counselors can use the scale to better understand why physicians, as a population, are reticent to seek counseling.

Pending at least acceptable validity evidence, we sought to investigate the capacity of physicians’ RFSV scores for predicting referrals to counseling and to examine demographic differences in RFSV scores. Results have the potential to offer professional counselors a screening tool for understanding why physicians might be reticent to seek counseling. Findings also have the potential to reveal subgroups of physicians who might be especially unlikely to access counseling services. To these ends, the following research questions (RQs) were posed:

RQ1. What is the factorial invariance of scores on the RFSV Scale among a national sample of U.S. physicians?

RQ2. Are U.S. physicians’ RFSV scores statistically significant predictors of making at least one referral to counseling?

RQ3. Are there demographic differences to the RFSV barriers among U.S. physicians’ RFSV scores?

Method

Participants and Procedures

A quantitative cross-sectional psychometric research design was utilized to answer the research questions. The current study is part of a larger grant-funded project with an aim to promote health-based screening efforts and wellness among physicians. The aim of the previous study (Kalkbrenner et al., 2025) was to test the psychometric properties of three wellness-based screening tools with physicians. In the present study, we further analyzed the data in Kalkbrenner et al. (2025) to answer different research questions about a different scale (the RFSV Scale) on barriers to counseling. This data set was collected following approval from our IRB. Crowdsourcing is an increasingly common data collection strategy in counseling research with utility for accessing prospective participants on national and global levels (Mullen et al., 2021). Qualtrics Sample Services is a crowdsource solutions service with access to over 90 million prospective participants who voluntarily participate in survey research for monetary compensation. Grant funding was utilized to engage the services of a data collection agency to enlist a nationwide cohort of U.S. physicians. Qualtrics Sample Services was selected because they were the only crowdsource service we came across that could provide a sample of more than 400 licensed U.S. physicians. A sample greater than 400 was necessary for answering the first research question because 200 participants per group is the lower end of acceptable for multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis (MG-CFA; Meade & Kroustalis, 2006). Qualtrics Sample Services provided us with a program manager and a team of analysts who undertook a meticulous quality assessment of the data. This quality assessment involved filtering out respondents exhibiting excessive speed in responding, random response patterns, failed attention checks, and instances of implausible responses (e.g., individuals claiming to be 18 years old with an MD).

A total of N = 437 valid responses that met quality standards were obtained. An analysis of missing values indicated an absence of missing data. Examination of standardized z-scores and Mahalanobis (D) distances identified no univariate outliers (z > ± 3.29) and no multivariate outliers, respectively. Skewness and kurtosis values for physicians’ scores on the RFSV Scale were within the range indicative of a normal distribution of test scores (skewness < ± 2 and kurtosis < ± 7). Participants in the sample (N = 437) ranged in age from 25 to 85 (M = 47.80, SD = 11.74); see Table 1 for the demographic profile of the sample.

Table 1

Demographic Profile of the Sample (N = 437)

| Sample Characteristics | n | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 217 | 49.7 |

| Female | 215 | 49.2 |

| Transgender | 1 | 0.2 |

| Nonbinary | 1 | 0.2 |

| Preferred not to answer | 3 | 0.7 |

| Ethnoracial Identity | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 0.2 |

| Asian or Asian American | 28 | 6.4 |

| Black or African American | 76 | 17.4 |

| Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish origin | 97 | 22.2 |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 6 | 1.4 |

| Multiethnic | 6 | 1.4 |

| White or European American | 216 | 49.4 |

| Identified as another race, ethnicity, or origin | 1 | 0.2 |

| Preferred not to answer | 4 | 0.9 |

| Help-Seeking History | ||

| No help-seeking history | 228 | 52.2 |

| Help-seeking history | 208 | 47.6 |

| Work Setting | ||

| Private practice | 202 | 46.2 |

| Non–private practice | 233 | 53.3 |

| Did not report work setting | 2 | 0.5 |

Measures

Prospective participants voluntarily indicated their informed consent and confirmed that they met the eligibility criteria for participation, including being a physician licensed as an MD, treating patients in the United States, and being over 18 years old at the time of data collection. Participants then responded to a demographic questionnaire and completed the RFSV Scale.

The RFSV Scale

The RFSV Scale is a screening tool designed to measure respondents’ sensitivity to barriers to attending counseling (Kalkbrenner et al., 2019) and is comprised of three subscales. Participants respond to a stem (“I am less likely to attend counseling because . . . ”) on the following Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, or 5 = Strongly Agree. Higher scores indicate greater reluctance to seek counseling. The Fit subscale measures the degree to which a respondent believes that the counseling process is congruent with their personality, values, or beliefs (e.g. “I couldn’t find a counselor who would understand me”). The Stigma subscale measures one’s reluctance to attend counseling because of shame or embarrassment (e.g. “It would damage my reputation”). The Value subscale appraises the degree to which a respondent perceives the effort required to attend counseling as beneficial (e.g. “It is not an effective use of my time”).

Kalkbrenner et al. (2019) found moderate to strong reliability evidence of scores on the RFSV subscales (Fit α = .82, Stigma α = .91, Value α = .78) and support for the internal structure validity of the RFSV through factor analysis. Additionally, Kalkbrenner and Neukrug (2018) demonstrated evidence of internal structure validity of RFSV scores through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Moreover, Kalkbrenner et al. (2022) found internal structure validity and criterion validity evidence of RFSV scores. More specifically, Kalkbrenner et al. (2022) found internal structure validity evidence of RFSV scores via CFA with a normative sample of STEM students. In addition, Kalkbrenner et al. (2022) found that STEM students’ scores on the Value barrier were a statistically significant predictor of a non-test criterion (referrals to the counseling center), which supported criterion validity of RFSV scores.

Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω) were calculated to estimate the reliability of physicians’ scores on the RFSV Scale. Consistent with the Responsibilities of Users of Standardized Tests (RUST-4E) standards, we computed confidence intervals (CIs) for each point reliability estimate (Lenz et al., 2022). All CIs were estimated at the 95% level. The following interpretive guidelines for internal consistency reliability evidence of test scores were used: α > .70 (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011) and ω > .65 (Nájera Catalán, 2019). Among the sample of physicians in the present study, scores on the Fit subscale showed acceptable internal consistency reliability of scores (α = .819, 95% CI [.789, .846]; ω = .827, 95% CI [.799, .851]). Scores on the Stigma subscale displayed acceptable-to-strong internal consistency reliability evidence of scores (α = .896, 95% CI [.877, .912]; ω =. 902, 95% CI [.885, .918]). Physicians’ scores on the Value subscale displayed acceptable internal consistency reliability of scores (α = .817, 95% CI [.781, .848]; ω =.820, 95% CI [.783, .850]). Finally, we found strong internal consistency reliability estimates of scores on the Global Barriers scale (α = .902, 95% CI [.885, .915]; ω = .897, 95% CI [.887, .911]).

Data Analytic Plan

MG-CFA is an advanced psychometric analysis for determining the extent to which the meaning of latent constructs remain stable across subgroups of a sample (Dimitrov, 2012). MG-CFA is particularly sensitive to sample size (Meade & Kroustalis, 2006). A number of guidelines for MG-CFA sample size exist; however, at least 200 participants per each level of every invariance variable tends to be the minimum. To ensure that the present sample included 200+ participants in each group (see Table 2), the gender identity and ethnoracial identity variables were coded as female or male and White or non-White, respectively, for sample size considerations. This method of dummy coding highlights a frequent sample size–based challenge encountered in survey research, particularly in the context of assessing gender or ethnoracial identity (Ross et al., 2020). However, this coding method can be appropriate for survey research provided that the authors openly acknowledge the limitations inherent in such procedures, and that there is at least some degree of consistency between the dummy-coded groups and both the existing literature and the research questions (Ross et al., 2020). The coded groups are consistent with the literature and RQs, as findings in the extant literature (e.g., Duarte et al., 2022) demonstrated mental health care disparities between White and non-White and between male and female physicians. There are macro- and microlevel inequalities in the U.S. health care system between White and non-White populations (Matthew, 2015). Using the comparative method between participants with White and non-White ethnoracial identifies can have utility for highlighting the discrepancies in the U.S. health care system (Matthew, 2015; Ross et al., 2020). The limitations of this statistical aggregation procedure in terms of external validity will be articulated in the Discussion section.

Table 2

Multiple-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis: RFSV Scale With U.S. Physicians

| Invariance Forms | CFI | ∆CFI | RMSEA | ∆RMSEA | RMSEA CIs | SRMR | ∆SRMR | Model Comparison | |

| Ethnoracial Identity: White (n = 216) vs. Non-White (n = 215) | |||||||||

| Configural | .934 | .057 | .049; .064 | .070 | |||||

| Metric | .933 | .001 | .055 | .002 | .048; .063 | .070 | < .001 | Configural | |

| Scalar | .928 | .005 | .055 | < .001 | .048; .062 | .071 | .001 | Metric | |

| Gender Identity: Female (n = 215) vs. Male (n = 217) | |||||||||

| Configural | .936 | .056 | .048; .063 | .060 | |||||

| Metric | .935 | .001 | .055 | .001 | .047; .062 | .066 | .006 | Configural | |

| Scalar | .921 | .014 | .057 | .002 | .051; .064 | .067 | .001 | Metric | |

| Help-Seeking History: Yes (n = 208) vs. No (n = 228) | |||||||||

| Configural | .921 | .062 | .055; .070 | .080 | |||||

| Metric | .921 | < .001 | .061 | .001 | .053; .068 | .080 | < .001 | Configural | |

| Scalar | .906 | .015 | .063 | .001 | .057; .070 | .079 | .001 | Metric | |

| Work Setting: Private Practice (n = 202) vs. Non-Private Practice (n = 233) | |||||||||

| Configural | .942 | .053 | .045; .061 | .062 | |||||

| Metric | .937 | .005 | .054 | .001 | .046; .061 | .075 | .013 | Configural | |

| Scalar | .936 | .001 | .052 | .002 | .044; .059 | .075 | < .001 | Metric | |

We computed an MG-CFA to test the factorial invariance of U.S. physicians’ RFSV scores (RQ1). All statistical analyses were computed in IBM SPSS AMOS version 29 with a maximum likelihood estimation method. The fit of the baseline configural models was compared to the following cutoff scores: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .08 = acceptable fit and < .06 = strong fit), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < .08 = acceptable fit and < .06 = strong fit), and the comparative fit index (CFI, .90 to .95 = acceptable fit and > .95 = strong fit (Dimitrov, 2012; Schreiber et al., 2006). Pending at least acceptable fit of the baseline models, we used the following guidelines for factorial invariance testing: < ∆ 0.010 in the CFI, < ∆ 0.015 in the RMSEA, and < ∆ 0.030 in the SRMR for metric invariance or < ∆ 0.015 in SRMR for scalar invariance (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

A binary logistic regression analysis was computed to investigate the predictive capacity of physicians’ RFSV scores (RQ2). The predictor variables included physicians’ interval level scores on the RFSV Scale. The criterion variable was whether or not physicians have made at least one referral to counseling (0 = no or 1 = yes). Interscale corrections between the RFSV scales ranged from r = .44 to r = .55, indicating that multicollinearity was not present in the data.

A 2 (gender) X 2 (ethnicity) X 2 (work setting) X 2 (help-seeking history) factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was computed to investigate differences in physicians’ RFSV scores (RQ3). The categorical level independent variables (IVs) included gender (female or male), ethnoracial identity (White or non-White), help-seeking history (yes or no), and work setting (private practice or non–private practice). The dependent variables (DVs) were physicians’ interval level scores on the RFSV Scale. Box’s M test demonstrated that the assumption of equity of covariance matrices was met, F = (90, 73455.60) = 86.28, p = .719.

Results

Factorial Invariance Testing

An MG-CFA was computed to answer the first research question regarding the factorial invariance of U.S. physicians’ scores on the RFSV Scale. First, the baseline configural models were investigated for fit. We then tested for invariance, as the baseline models showed acceptable fit based on the previously cited guidelines provided by Dimitrov (2012) and Schreiber et al. (2006), including gender identity (CFI = .936, RMSEA = .056, 90% CI [.048, .063], and SRMR = .060), ethnoracial identity (CFI = .934, RMSEA = .057, 90% CI [.049, .064], and SRMR = .070), help-seeking history (CFI = .921, RMSEA = .062, 90% CI [.055, .070], and SRMR = .080), and work setting (CFI = .942, RMSEA = .053, 90% CI [.045, .061], and SRMR = .062).

In terms of invariance, all of the fit indices (∆CFI, ∆RMSEA, and ∆SRMR) supported both metric and scalar invariance of scores for ethnoracial identity and work setting (see Table 2). For the gender identity and help-seeking history variables, the ∆RMSEA and ∆SRMR supported both metric and scalar invariance of scores. The ∆CFI supported metric but not scalar invariance of scores for the help-seeking history and gender identity variables. Demonstrating invariance can be deemed acceptable solely based on metric invariance (Dimitrov, 2010). This is particularly true when only a single fit index, such as the CFI, confirms metric invariance but not scalar invariance of scores.

Logistic Regression

A logistic regression analysis was computed to answer the second research question regarding the predictive capacity of physicians’ RFSV scores. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, X2 (3) = 15.36, p = .002, Nagelkerke R2 = .05. The odds ratios, Exp(B), demonstrated that an increase of one unit in physicians’ scores on the Stigma subscale (higher scores = higher barriers to counseling) was associated with a decrease in the odds of having made at least one referral to counseling by a factor of .711, Exp(B) 95% CI [.517, .947], p = .036. In addition, an increase of one unit in physicians’ scores on the Value subscale was associated with a decrease in the odds of having made at least one referral to counseling by a factor of .707, Exp(B) 95% CI [.508, .984], p = .040.

Factorial MANOVA

A 2 (gender) X 2 (ethnicity) X 2 (work setting) X 2 (help-seeking history) factorial MANOVA was computed to investigate differences in physicians’ RFSV scores (RQ3). A significant main effect emerged for gender on the combined DVs, F = (3, 409) = 6.50, p < .001, Λ = 0.95, n2p = .05. The statistically significant findings in the MANOVA were followed up with post-hoc discriminant analyses. The discriminant function significantly discriminated between groups, λ = 0.94, X2 = 25.07, df = 3, Canonical correlation = .29, p < .001. The correlations between the latent factors and discriminant functions showed that Fit (−1.17) loaded more strongly on the function than Stigma (0.68) and Value (0.62), suggesting that Fit contributed the most to group separation in gender identity. The mean discriminant score on the function for male physicians was 0.24 and the mean score for female physicians was −0.25 (higher scores = greater barriers to counseling).

A significant main effect emerged for help-seeking history on the combined DVs, F = (3, 409) = 4.57, p = .004, Λ = 0.95, n2p = .03. The post-hoc discriminant function significantly discriminated between groups, Wilks λ = 0.96, X2 = 19.61, df = 3, Canonical correlation = .21, p < .001. The correlations between the latent factors and discriminant functions showed that Value (1.03) loaded more strongly on the function than Stigma (0.28) and Fit (0.26), suggesting Value contributed the most to group separation in help-seeking history. The mean discriminant score on the function for physicians with a help-seeking history was −0.23 and the mean score was 0.21 for physicians without a help-seeking history.

Discussion

The aims of the present study were to: validate RFSV scores with a national sample of physicians in the United States, investigate the capacity of RFSV scores for predicting physician referrals to counseling, and investigate demographic differences in physicians’ RFSV scores. The findings will be discussed in accordance with the RQs. The model fit estimates for each of the baseline configural models were all in the acceptable range based on the recommendations of Dimitrov (2012) and Schreiber et al. (2006; see Table 2). The acceptable fit of the configural models supported that the RFSV Scale and its dimensionality were estimated adequately with a normative sample of physicians. RFSV scores have been normed with seven different normative samples since 2018, including adults in the United States (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018), mental health counselors (Kalkbrenner et al., 2019), counselors-in-training (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2019), college students at an HSI (Kalkbrenner et al., 2022), and STEM students (Kalkbrenner & Miceli, 2022). The baseline CFA results in the present study extend the generalizability of RFSV scores to a normative sample of physicians in the United States. Because we found support for the baseline configural models, we proceeded to test for invariance of scores.

Invariance testing via MG-CFA takes internal structure validity testing to a higher level by revealing if the meaning of a latent trait stays consistent (i.e., invariant) between specific groups of a normative sample (Dimitrov, 2012). The results of factorial invariance testing were particularly strong and evidenced both metric and scalar invariance of RFSV scores for the ethnoracial identity and work setting variables. The ∆ in RMSEA and SRMR also supported both metric and scalar invariance for the help-seeking history and gender identity variables. The ∆ in CFI revealed metric, but not scalar invariance of scores for the help-seeking history and gender identity variables. Metric invariance alone can be sufficient for demonstrating invariance of scores across a latent trait (Dimitrov, 2010). This is particularly true when only a single fit index, such as the CFI, supports metric invariance but not scalar invariance of scores. In totality, the MG-CFA results supported invariance of physicians’ RFSV scores by ethnoracial identity, work setting, and, to a lesser but acceptable degree, help-seeking history and gender identity.

The MG-CFA results demonstrated that RFSV scores were valid among a national sample of U.S. physicians (RQ1). This finding adds rigor to the results of RQs 2 and 3 on predictive and demographic differences in physicians’ RFSV scores, as the scale was appropriately calibrated with a new normative sample. A test of the predictive capacity of RFSV scores revealed that physicians’ scores on the Stigma and Value subscales were statistically significant predictors of having made one or more referrals to counseling (RQ2). In other words, lower levels of stigma and higher attributions to the value of counseling were associated with higher odds of physicians making one or more referrals to counseling at a statistically significant level. This finding is consistent with Kalkbrenner and Miceli (2022), who found that scores on the Value subscale were predictors of referrals to counseling among STEM students. Similarly, Kalkbrenner et al. (2022) found that scores on the Value subscale predicted supportive responses to encountering a peer in mental distress among college students attending an HSI. Collectively, the findings of the present study are consistent with past investigators (e.g., Kalkbrenner et al., 2022) who found that more positive attitudes about counseling tend to predict increases in the odds of having made one or more peer referrals to counseling.

The final aim of the present study was to test for demographic differences in physicians’ sensitivity to the RFSV barriers (RQ3). We found statistically significant main effects for the gender identity and help-seeking history variables. Results revealed that male physicians were more sensitive to the Fit barrier than female physicians. This finding suggests that physicians who identify as male might be more skeptical about the counseling process in general and may doubt their chances of finding a counselor they feel comfortable with. This finding adds to the extant literature on physicians’ mental health and attitudes about seeking counseling. Past investigators (e.g., Sudol et al., 2021) documented female physicians’ increased risk for mental health stress when compared to male physicians. The findings of the present study showed that male physicians were more sensitive to the Fit barrier than female physicians. Accordingly, it is possible that female physicians are more likely to report symptoms of and seek support services for mental health issues than male physicians. This might be due, in part, to differences between male and female physicians’ beliefs about the fit of counseling. Future research is needed to test this possible explanation for this finding.

We found that physicians with a help-seeking history (i.e., attended one or more counseling sessions in the past) were less sensitive to the Value barrier when compared to physicians without a help-seeking history. Similarly, past investigators found associations between help-seeking history and more positive attitudes about the value and benefits of seeking counseling, including among STEM students (Kalkbrenner & Miceli 2022), college students at an HSI (Kalkbrenner et al., 2022), and adults living in the United States (Kalkbrenner & Neukrug, 2018). Collectively, the results of the present study are consistent with these existing findings, which suggest that physicians and members of other populations with help-seeking histories tend to attribute more value toward the anticipated benefits of counseling.

Limitations and Future Research

We recommend that readers consider the limitations of the present study before the implications for practice. Causal attributions cannot be drawn from a cross-sectional survey research design. Future researchers can build upon this line of research by testing the RFSV barriers using an experimental approach. Such research could involve administering the scale to physician clients before and after their counseling sessions. Such an approach might yield evidence on how counseling reduces sensitivity to certain barriers. However, it is important to note that pretest/posttest approaches can come with a number of limitations, including attrition, regression to the mean, history, and maturation.

Dummy coding the sociodemographic variables into broader categories to ensure adequate sample sizes for MG-CFA was a particularly challenging decision, especially for the ethnoracial identity variable. Although this statistical aggregation procedure can be useful for making broad and tentative generalizations about ethnicity and other variables (Ross et al., 2020), it limited our ability to explore potential differences in the meaning of the RFSV barriers among physicians with identities beyond White or non-White, and male or female. Future research with a more diverse sample by gender and ethnoracial identity is recommended.

Implications for Practice

The findings from this study provide robust psychometric evidence that supports the dimensionality of U.S. physicians’ scores on the RFSV Scale and carries important implications for counseling professionals. The National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC; 2023) emphasizes the use of screening tools with valid scores as a means of improving clinical practice. Additionally, ethical guidelines for counselors stress the importance of ensuring that the screening tools that they utilize offer valid and reliable scores, derived from representative client samples, to uphold their effectiveness and proper application (AERA, 2014; Lenz et al., 2022; NBCC, 2023). Mental health issues and attitudes about utilizing mental health support services are influenced by microsystemic and macrosystemic factors (Lenz & Lemberger-Truelove, 2023; Pester et al., 2023). To this end, implications for practice will be discussed on both microsystemic and macrosystemic levels.

The practicality of the RFSV Scale adds to its utility, as it is free to use, simple to score, and typically takes between 5 and 8 minutes to complete. Identifying barriers or doubts that physician clients have about counseling during the intake process might help increase physician client retention. To these ends, counselors can include the RFSV Scale with intake paperwork for physician clients. Counselors can use the results as one way to gather information about doubts that their physician clients might have about attending counseling. Suppose, for example, that a physician client scores higher on the Fit subscale (higher scores = higher barriers to counseling) than the Stigma or Value subscales. It might be helpful for the counselor and client to discuss how they can make the counseling process a good fit (i.e., how and in what ways the counseling process can be congruent with their personality, values, or beliefs). Increasing physician clients’ buy-in regarding the counseling process may increase retention.

Counselors could also administer the RFSV Scale at the beginning, middle, and end of the counseling process when working with clients who are physicians or medical students. Results might reveal the utility of counseling for reducing barriers to counseling among clients who are physicians or medical students. Our results revealed that physicians with help-seeking histories perceived greater value about the benefits of counseling than physicians without help-seeking histories. Mental health support services provided by counselor education students can be a helpful resource for medical students and residents (Gerwe et al., 2017). Accordingly, there may be utility in counselor education programs collaborating with medical colleges and schools to address stigma around seeking counseling that can exist in the medical field. This broader perspective is consistent with the ecological systems direction that the counseling profession spearheaded (Lenz & Lemberger-Truelove, 2023; Pester et al., 2023) and could help address stigma toward seeking counseling before medical students become physicians. More specifically, directors and clinical coordinators of counseling programs can reach out to directors of medical schools to establish collaborative relationships in which counseling interns provide supervised counseling services to medical students and residents. This might have dual benefits because medical schools would be able to offer their students free mental health support services and counseling programs would provide additional internship sites for their students. Early intervention before students become physicians could reduce stigma toward counseling throughout their careers.

Time constraints can be a barrier to counseling among physicians, residents, and medical students (Gerwe et al., 2017; Kase et al., 2020). Accordingly, it could be beneficial for counseling students who are interested in working with medical students or residents to complete their internship placements in the same settings where medical students and residents work. In all likelihood, providing supervised group and individual counseling for medical students at their work sites would increase the accessibility of counseling.

The counseling profession is moving toward interdisciplinary collaboration models that involve teams of mental health professionals working together to provide comprehensive client/patient care (Lenz & Lemberger-Truelove, 2023; Pester et al., 2023). Interventions designed to reduce barriers to counseling are only beginning to appear in the extant literature (e.g., Lannin et al., 2019). The ecological systemic nature of mental health distress and influences on attitudes about accessing mental health support services makes evaluating the utility of reducing barriers to counseling interventions complex. To address this, counselors and interdisciplinary teams need screening tools with reliable and valid scores in order to effectively assess the impact of these interventions.

The results of CFA and MG-CFA in the present study confirmed that the RFSV Scale measured the intended construct of measurement with a national sample of U.S. physicians (RQ1). Thus, the RFSV Scale may have utility as a pretest/posttest for measuring the effectiveness of interventions geared toward reducing barriers to counseling. The extant literature on interventions for reducing barriers to counseling is in its infancy. Lannin et al. (2019) started to fill this gap in the knowledge base by conducting an intervention study with random assignment. Lannin et al. (2019) tested the extent to which contemplation about seeking counseling and self-affirmation were related to seeking mental health screening and general information about mental health support services. Results revealed that participants who used both self-affirming personal values and contemplation were significantly more likely to seek mental health screening and general information about mental health than participants in the contemplation-only group. In addition, participants in the contemplation about seeking counseling group only reported higher self-stigma. Findings indicated that interventions including both contemplation and self-affirmation of participants’ personal values were more likely to increase receptivity to outreach efforts.

Lannin et al. (2019) sampled undergraduate students attending a historically Black college/university. Lannin et al.’s (2019) intervention might have utility with physicians. However, to the best of our knowledge, the screening tools used by Lannin et al. have not been validated with U.S. physicians. Accordingly, professional counselors can use the RFSV Scale as one way to measure potential reductions in barriers to seeking counseling before and after participating in interventions geared toward promoting help-seeking among physicians. Fully developing an intervention that reduces barriers to counseling is beyond the scope of this study. Although future research is needed in this area, the results of this study confirmed that the RFSV Scale measured the intended construct of measurement with a national sample of U.S. physicians. Accordingly, professional counselors can use the RFSV Scale to better understand why prospective or current physician clients are reluctant to seek counseling. For example, professional counselors can work with medical supervisors and the directors of physician residency programs to administer the RFSV Scale at orientations for new physician employees and medical residents. The results could reveal specific barriers that are particularly salient in a given medical setting. Professional counselors can use the results to structure psychoeducation sessions about the utility of counseling for physicians. Suppose, for example, that physicians in a particular setting score higher on the Stigma subscale. A counselor can structure the content of the psychoeducation session on reducing stigma toward counseling. Specifically, the session could involve reframing seeking counseling in the context of the courage it takes for one to reach out to a counselor and the benefits associated with participating in counseling. These sessions may also help strengthen interpersonal bonds among physicians and begin to normalize mental health support within the medical community.

Consistent with the findings of Kalkbrenner and Miceli (2022), we found that lower scores on the Value subscale (lower scores = greater perceived benefits of counseling) was a statistically significant predictor of higher odds of participants having made one or more peer referrals to counseling. This finding, combined with the extant literature on physicians’ vulnerability to mental health distress and reticence to seek counseling (Lobelo & de Quevedo, 2016; Walker & Pine, 2018), suggested that peer-to-peer support may be a valuable resource for counselors who work in medical settings. In other words, we found that greater perceived value of the benefits of counseling was a statistically significant predictor of an increase in the odds of physicians recommending counseling to another physician. Accordingly, professional counselors who work in medical settings are encouraged to organize peer-to-peer support networks among physicians within their work setting. For example, professional counselors can work to promote physicians’ awareness of the value of attending professional counseling, particularly for reducing burnout, grieving the loss of a patient, coping with the demanding work life of physicians, and increasing general health (Major et al., 2021; Trivate et al., 2019; Wiederhold et al., 2018). Our results revealed that when compared to female physicians, male physicians scored higher on the Fit subscale (higher RFSV scores = poorer attitudes about counseling) and physicians with a help-seeking history scored higher on the Value subscale than those without help-seeking histories. To this end, there may be utility in focusing outreach sessions about the benefits of counseling to male physicians. For example, professional counselors could produce short videos, flyers, or other types of media on the benefits that attending counseling can have for physicians. These media sources can be shared with physicians. Such awareness advocacy about the benefits of counseling may result in an increase of peer-to-peer referrals to counseling among physicians.

Summary and Conclusion

Physicians in the United States face increased risks for mental distress and often hesitate to seek professional counseling (Lobelo & de Quevedo, 2016; Walker & Pine, 2018). Screening tools with validated scores are essential resources for helping professional counselors to understand why potential clients avoid seeking counseling services. The RFSV Scale measures barriers to counseling. This study aimed to validate RFSV scores among U.S. physicians and investigated demographic differences in their scores. Results indicated that the RFSV Scale and its dimensions were adequately estimated with a national sample of physicians in the United States. Physicians’ RFSV scores significantly predicted peer-to-peer counseling referrals. We identified demographic differences in sensitivity to barriers to counseling based on gender identity and help-seeking history. Physicians who self-identified as male and those without help-seeking histories were more sensitive to barriers to counseling than female physicians or physicians with help-seeking histories, respectively. At this phase of development, professional counselors can use the RFSV Scale as a tool for understanding barriers to seeking counseling among physicians.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, & Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (U.S.). (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. https://www.apa.org/science/programs/testing/standards

American Hospital Association. (2022). Suicide prevention: Evidence-informed interventions for the health care workforce. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/09/suicide-prevention_evidence-informed-interventions-for-the-health-care-workforce.pdf

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Cheng, H.-L., Wang, C., McDermott, R. C., Kridel, M., & Rislin, J. L. (2018). Self-stigma, mental health literacy, and attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12178

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Creager, J., Coutinho, A. J., & Peterson, L. E. (2019). Associations between burnout and practice organization in family physicians. Annals of Family Medicine, 17(6), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2448

Dimitrov, D. M. (2010). Testing for factorial invariance in the context of construct validation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 43(2), 121–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175610373459

Dimitrov, D. M. (2012). Statistical methods for validation of assessment scale data in counseling and related fields. American Counseling Association.

Douglas, R. N., Sharpe, E. E., Kraus, M., Saddawi-Konefka, D., Hanson, A. C., & Pulos, B. (2023). Mental health questions on state medical license applications and evaluation of updates. JAMA Network Open, 6(9), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.33360

Duarte, D., El-Hagrassy, M. M., Castro e Couto, T., Gurgel, W., Fregni, F., & Correa, H. (2020). Male and female physician suicidality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(6), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0011

Duarte, D., El-Hagrassy, M. M., Couto, T., Gurgel, W., Frey, B. N., Kapczinski, F., & Correa, H. (2022). Physician suicide demographics and the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 44(2). https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2021-1865

Dyrbye, L. N., Eacker, A., Durning, S. J., Brazeau, C., Moutier, C., Massie, F. S., Satele, D., Sloan, J. A., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2015). The impact of stigma and personal experiences on the help-seeking behaviors of medical students with burnout. Academic Medicine, 90(7), 961–969. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000655

Dyrbye, L. N., West, C. P., Sinsky, C. A., Goeders, L. E., Satele, D. V., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2017). Medical licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(10), 1486–1493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.06.020

Gerwe, C., Parks-Savage, A. C., Bertolet, C. L., Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Archer, L. (2017). Promoting the wellness of physician-residents: Counselor-delivered coaching. Counseling & Wellness: A Professional Counseling Journal, 6(1), 1–19.

Gold, K. J., Andrew, L. B., Goldman, E. B., & Schwenk, T. L. (2016). “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: A survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. General Hospital Psychiatry, 43(1), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.09.004

Goldman, M. L., Bernstein, C. A., & Summers, R. F. (2018). Potential risks and benefits of mental health screenings of physicians. JAMA, 320(24), 2527–2528. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.18403

Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Miceli, G. (2022). Barriers to seeking counseling among STEM students: The Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value Scale. The Professional Counselor, 12(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.15241/mtk.12.3.249

Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Neukrug, E. S. (2018). Identifying barriers to attendance in counseling among adults in the United States: Confirming the factor structure of the Revised Fit, Stigma, & Value Scale. The Professional Counselor, 8(4), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.15241/mtk.8.4.299

Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Neukrug, E. S. (2019). The utility of the Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value Scale with counselor trainees: Implications for enhancing clinical supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 38(2), 262–280.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2019.1634665

Kalkbrenner, M. T., Neukrug, E. S., & Esquivel, L. E. (2022). Mental health literacy screening of students in Hispanic Serving Institutions. Journal of Counseling & Development, 100(3), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12428

Kalkbrenner, M. T., Neukrug, E. S., & Griffith, S.-A. M. (2019). Appraising counselors’ attendance in counseling: The validation and application of the Revised Fit, Stigma, and Value Scale. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.1.03

Kalkbrenner, M. T., Sun, H., & Peterson, S. (2025). Psychometric evaluation of wellness-based screeners: National sample of U.S. physicians. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 47(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2024.2441135

Kase, S. M., Gribben, J. L., Waldman, E. D., & Weintraub, A. S. (2020). A pilot study exploring interventions for physician distress in pediatric subspecialists. Pediatric Research, 88(1), 398–403. https://doi.org./10.1038/s41390-020-0805-x

Kevern, T., Davies, D. R., Stiel, K., & Raaum, S. (2023). Impact of opt-out therapy appointments on resident physicians’ mental health, well-being, stigma, and willingness to engage. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 15(6), 734–737. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00898.1

Lannin, D. G., Ludwikowski, W. M. A., Vogel, D. L., Seidman, A. J., & Anello, K. (2019). Reducing psychological barriers to therapy via contemplation and self-affirmation. Stigma and Health, 4(3), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000139

Lenz, A. S., Ault, H., Balkin, R. S., Barrio Minton, C., Erford, B. T., Hays, D. G., Kim, B. S. K., & Li, C. (2022). Responsibilities of users of standardized tests (RUST-4E): Prepared for the Association for Assessment and Research in Counseling. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 55(4), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2022.2052321

Lenz, A. S., & Lemberger-Truelove, M. E. (2023). The social determinants of mental health and professional counseling: A call to action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101(4), 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12489

Linzer, M., Poplau, S., Babbott, S., Collins, T., Guzman-Corrales, L., Menk, J., Murphy, M. L., & Ovington, K. (2016). Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: Results from a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(9), 1004–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3720-4

Lobelo, F., & de Quevedo, I. G. (2016). The evidence in support of physicians and health care providers as physical activity role models. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 10(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827613520120

Major, A., Williams, J. G., McGuire, W. C., Floyd, E., & Chacko, K. (2021). Removing barriers: A confidential opt-out mental health pilot program for internal medicine interns. Academic Medicine, 96(5), 686–689. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003965

Matthew, D. B. (2015). Just medicine: A cure for racial inequality in American health care. New York University Press.

Meade, A. W., & Kroustalis, C. M. (2006). Problems with item parceling for confirmatory factor analytic tests of measurement invariance. Organizational Research Methods, 9(3), 369–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105283384

Mehta, S. S., & Edwards, M. L. (2018). Suffering in silence: Mental health stigma and physicians’ licensing fears. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal, 13(11), 2–4. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2018.131101

Melnyk, B. M., Kelly, S. A., Stephens, J., Dhakal, K., McGovern, C., Tucker, S., Hoying, J., McRae, K., Ault, S., Spurlock, E., & Bird, S. B. (2020). Interventions to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle behaviors in physicians and nurses: A systematic review. American Journal of Health Promotion, 34(8), 929–941. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120920451

Mortali, M., & Moutier, C. (2018). Facilitating help-seeking behavior among medical trainees and physicians using the Interactive Screening Program. Journal of Medical Regulation, 104(2), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.30770/2572-1852-104.2.27

Mullen, P. R., Fox, J., Goshorn, J. R., & Warraich, L. K. (2021). Crowdsourcing for online samples in counseling research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12369

Nájera Catalán, H. E. (2019). Reliability, population classification and weighting in multidimensional poverty measurement: A Monte Carlo study. Social Indicators Research, 142(3), 887–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1950-z

National Board for Certified Counselors. (2023). NBCC code of ethics. https://bit.ly/NBCCCodeofEthics

Pester, D. A., Jones, L. K., & Talib, Z. (2023). Social determinants of mental health: Informing counseling practice and professional identity. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101(4), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12473

Ross, P. T., Hart-Johnson, T., Santen, S. A., & Zaidi, N. L. B. (2020). Considerations for using race and ethnicity as quantitative variables in medical education research. Perspectives on Medical Education, 9(5), 318–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-020-00602-3

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338.

https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Shanafelt, T. D., Schein, E., Minor, L. B., Trockel, M., Schein, P., & Kirch, D. (2019). Healing the professional culture of medicine. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(8), 1556–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.026

Sudol, N. T., Guaderrama, N. M., Honsberger, P., Weiss, J., Li, Q., & Whitcomb, E. L. (2021). Prevalence and nature of sexist and racial/ethnic microaggressions against surgeons and anesthesiologists. JAMA Surgery, 156(5), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0265

Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2(1), 53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Trivate, T., Dennis, A. A., Sholl, S., & Wilkinson, T. (2019). Learning and coping through reflection: Exploring patient death experiences of medical students. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 451. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1871-9

Walker, R., & Pine, H. (2018). Physician wellness is an ethical and public health issue. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 158(6), 970–971. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599818773296

Wiederhold, B. K., Cipresso, P., Pizzioli, D., Wiederhold, M., & Riva, G. (2018). Intervention for physician burnout: A systematic review. Open Medicine, 13(1), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2018-0039

Wimsatt, L. A., Schwenk, T. L., & Sen, A. (2015). Predictors of depression stigma in medical students: Potential targets for prevention and education. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(5), 703–714.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.021

Michael T. Kalkbrenner, PhD, NCC, is a full professor at New Mexico State University. Shannon Esparza, BA, is a graduate student at New Mexico State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Michael T. Kalkbrenner, Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, mkalk001@nmsu.edu.