Examining the Practicum Experience to Increase Counseling Students’ Self-Efficacy

James Ikonomopoulos, Javier Cavazos Vela, Wayne D. Smith, Julia Dell’Aquila

Master’s level counseling programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Education Programs (CACREP, 2016) require students to complete practicum and internship courses that involve group and individual or triadic supervision. Although clinical supervision provides students with effective skill development (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004), counseling students may begin practicum with low self-efficacy regarding their counseling abilities and skills. Given the importance of clinical supervision and counselor self-efficacy, it is surprising that there are limited studies that have examined the impact of supervision and practicum experience from the perspectives of supervisees. Almost all studies within this domain are qualitative and involve personal interviews with supervisees or supervisors (e.g., Hein & Lawson, 2008). In order to fill a gap in the literature and document the impact of the practicum experience, this study examined the effectiveness of the practicum experience encompassing direct counseling services, group supervision and triadic supervision to increase counseling students’ self-efficacy. First, we provide a literature review regarding group supervision, triadic supervision and counselor self-efficacy. Next, we present findings from a study with 11 counseling practicum students. Finally, we provide a discussion regarding the importance of these findings as well as implications for counseling practice and research.

Supervision in Counselor Education Coursework

CACREP requires an average of one and a half hours of weekly group supervision in practicum courses that involves an instructor with up to six counseling graduate students (Degges-White, Colon, & Borzumato-Gainey, 2012). Borders et al. (2012) identified that group supervisors use leadership skills, facilitate and monitor peer feedback, and encourage supervisees to take ownership of group process in group supervision. Borders and colleagues (2012) identified several benefits in group supervision, including exposure to multiple counselor styles and ability to learn about various educational issues. There also were challenges such as limited helpful feedback, brevity of case presentations, timing of group meetings and lack of educational opportunities. In another study, Conn, Roberts, and Powell (2009) compared hybrid and face-to-face supervision among school counseling interns. There were similarities in perceptions of quality of supervision, suggesting that distance learning can provide effective group supervision. CACREP counseling programs also require students to receive one hour of weekly supervision from a faculty member or doctoral student supervisor. Triadic is one form of supervision that involves a process whereby one supervisor meets and provides feedback with two supervisees (Hein & Lawson, 2008). Hein and Lawson (2008) explored supervisors’ perspectives on triadic supervision and found increased demands on the role of the supervisor. For example, supervisors felt additional pressure to support both supervisees in supervision. Additionally, Lawson, Hein, and Stuart (2009) investigated supervisees’ perspectives of triadic supervision. Noteworthy findings included: some students perceived less time and attention to their needs; importance of compatibility between supervisees; and careful attention must be given when communicating feedback, particularly if negative feedback must be given.

Finally, Borders et al. (2012) explored supervisors’ and supervisees’ perceptions of individual, triadic and group supervision. Benefits included vicarious learning experiences, peer-learning opportunities, and better supervisor feedback, while challenges included peer mismatch and difficulty keeping both supervisees involved.

Counselor Self-Efficacy

One of the most important outcome variables in counseling is self-efficacy. Bandura (1986) defined self-efficacy as individuals’ confidence in their ability to perform courses of action or achieve a desired outcome. Self-efficacy in counselor education settings might influence students’ thoughts, behaviors and feelings toward working with clients (Bandura, 1997). In the current study, counseling self-efficacy is defined as “one’s beliefs or judgments about his or her capabilities to effectively counsel a client in the near future” (Larson & Daniels, 1998, p. 1). Counselor self-efficacy also can refer to students’ confidence regarding handling the therapist role, managing counseling sessions and delivering helping skills (Lent et al., 2009). In higher education settings, researchers identified relationships between practicum students’ counseling self-efficacy and various client outcomes in counseling (Halverson, Miars, & Livneh, 2006). Self-efficacy also is positively related to performance attainment (Bandura, 1986), perseverance in counseling tasks, less anxiety (Larson & Daniels, 1998), positive client outcomes (Bakar, Zakaria, & Mohamed, 2011), and counseling skills development (Lent et al., 2009). Halverson et al. (2006) evaluated the impact of a CACREP program on counseling students’ conceptual level and self-efficacy. Longitudinal findings showed that counseling students’ perceptions of self-efficacy increased over the course of the program, primarily as a result of clinical experiences.

In another investigation, Greason and Cashwell (2009) examined mindfulness, empathy and self-efficacy among masters-level counseling interns and doctoral counseling students. Mindfulness, empathy and attention to meaning accounted for 34% of the variance in counseling students’ self-efficacy. Finally, Barbee, Scherer, and Combs (2003) investigated the relationship among prepracticum service learning, counselor self-efficacy and anxiety. Substantial counseling coursework and counseling-related work experiences were important influences on counseling students’ self-efficacy.

Purpose of Study

This study evaluated practicum experiences by using a single-case research design (SCRD) to measure the impact on students’ self-efficacy. In a recent special issue of the Journal of Counseling & Development, Lenz (2015) described how researchers and practitioners can use SCRDs to make inferences about the impact of treatment or experiences. SCRDs are appropriate for counselors or counselor educators for the following reasons: minimal sample size, self as control, flexibility and responsiveness, ease of data analysis, and type of data yielded from analyses. In the current study, the rationale for using an SCRD to examine the effectiveness of the practicum experience and triadic supervision was to provide counselor educators with insight regarding potential strategies that increase students’ self-efficacy. With this goal in mind, we implemented an SCRD (Lenz, Perepiczka, & Balkin, 2013; Lenz, Speciale, & Aguilar, 2012) to identify and explore trends of students’ changes in self-efficacy while completing their practicum experience. We addressed the following research question: to what extent does the practicum experience encompassing direct counseling services, group supervision and triadic supervision influence counseling graduate students’ self-efficacy?

Methodology

Instructors of record for three practicum courses formulated a plan to investigate the impact of the practicum experience on counseling students’ self-efficacy. We focused on providing students with a positive practicum experience with support, constructive feedback, wellness checks and learning experiences. With this goal in mind, we implemented a single case research design (Hinkle, 1992; Lenz et al., 2013; Lenz et al., 2012) to identify and explore trends of students’ changes in self-efficacy while completing their practicum experience. We selected this design to evaluate data that provides inferences regarding treatment effectiveness (Lenz et al., 2013). All practicum courses followed the same course requirements, and instructors shared the same level of teaching experience.

Participant Characteristics

We conducted this study with a sample of Mexican American counseling graduate students (N = 11) enrolled in a CACREP-accredited counseling program in the southwestern United States. This Hispanic Serving Institution had an enrollment of approximately 7,000 undergraduate and graduate students (approximately 93% of students at this institution are Latina/o) at the time of data collection. As a result, we were not surprised that all of the participants in the current study identified as Mexican American. Fifteen participants were solicited; four declined to participate. Participants (four men and seven women) ranged in age from 24 to 57 (M = 31; STD = 9.34). All participants were enrolled in practicum; we assigned participants with pseudonyms to protect their identity. Participants had diverse backgrounds in elementary education, secondary education, case management and behavioral intervention services. Participants also had aspirations of obtaining doctoral degrees or working in private practice, school settings, and community mental health agencies.

Instrumentation

Counselor Activity Self-Efficacy Scale. The Counselor Activity Self-Efficacy Scale (CASES) is a self-report measure of counseling self-efficacy (Lent, Hill, & Hoffman, 2003). This scale consists of 31 items with a 10-point Likert-type scale in which respondents rate their level of confidence from 0 (i.e., having no confidence at all) to 9 (i.e., having complete confidence). Participants respond to items on exploration skills, session management and client distress (Lent et al., 2003), with higher scores reflective of higher levels of self-efficacy. The total score across these domains represents counseling self-efficacy. Reliability estimates range from .96 to .97 (Greason & Cashwell, 2009; Lent et al., 2003). We used the total score as the outcome variable in our study.

Treatment

Over the course of a 14-week semester, participants received 12 hours of triadic supervision and approximately 25 hours of group supervision. We followed Lawson, Hein, and Getz’s (2009) model through pre-session planning, in-session strategies, administrative considerations and evaluations of supervisees. During triadic supervision meetings with two practicum students, the instructor of record conducted wellness checks assessing students’ well-being and level of stress, listened to concerns about clients, observed recorded sessions, provided support and feedback, and encouraged supervisees to provide feedback. The instructor of record also facilitated group supervision discussions on clients’ presenting problems, treatment planning, note-writing, and wellness and self-care strategies. All practicum instructors collaborated and communicated bi-weekly to monitor students’ progress as well as students’ work with clients. All students obtained a minimum of 40 direct hours while working at their university counseling and training clinic, where services are provided to individuals with emotional, developmental, and interpersonal issues. Treatment for depression, anxiety and family issues are the most common issues. The population receiving services at this counseling and training clinic are mostly Mexican American and Spanish-speaking clients who are randomly assigned to a practicum student after an initial phone screening.

Procedure

We evaluated treatment effect using an AB SCRD (in our case, we referred to this more precisely as BT for baseline and treatment), using scores on the CASES as an outcome measure. During an orientation before the semester, practicum students were informed that their instructors were interested in evaluating changes in self-efficacy. Students who agreed to participate in the current study completed baseline measure one at this time. Following this, we selected a pseudonym to identify each participant when completing counselor self-efficacy activity (CSEA) scales throughout the study. The baseline phase consisted of data collection for 3 weeks before the practicum experience. The treatment phase began after the third baseline measure, when the first triadic supervision session was integrated into the practicum experience. Individual cases under investigation were practicum students who agreed to document their changes in self-efficacy while completing the practicum experience. Given that participants serve as their own control group in a single case design, the number of participants in the current study was considered sufficient to explore the research question (Lenz et al., 2013).

Data Collection and Analysis

We implemented an AB, SCRD (Lundervold & Belwood, 2000; Sharpley, 2007) by gathering weekly scores of the CASES. We did not use an ABA design with a withdrawal phase given that almost all students enrolled in internship immediately after the semester. As a result, we did not want to collect data that would have tapped into students’ internship experiences. After three weeks of data collection, the baseline phase of data collection was completed. The treatment phase began after the third baseline measure where the first triadic supervision session occurred. After the 13th week of data collection, the treatment phase of data collection was completed due to nearing completion of the semester, for a total of three baseline and ten treatment phase collections. We did not collect additional treatment data points given that students were scheduled to begin internship at the conclusion of the semester. We only wanted to measure the impact of the practicum experience.

Percentage of data points exceeding the median (PEM) procedure was implemented to analyze the quantitative data from the AB single case design (Ma, 2006). A visual trend analysis was reported as data points from each phase were graphically represented to provide visual representations of change over time (Ikonomopoulos, Smith, & Schmidt, 2015; Sharpley, 2007). An interpretation of effect sizes was conducted to determine the effectiveness of triadic supervision integrated into the practicum experience when comparing each phase of data collection (Sharpley, 2007). Interpreting effect sizes for the PEM procedure yields a proportion of data overlap between a baseline and treatment condition expressed in a decimal format that ranges from zero and one. Higher scores represent greater treatment effects while lower scores represent less effective treatments. This procedure is conceptualized as the analysis of treatment phase data that is contingent on the overlap with the median data point within the baseline phase. Ma (2006) suggested that PEM is based on the assumption that if the intervention is effective, data will be predominately on the therapeutic side of the median. If an intervention is ineffective, data points in the treatment phase will vacillate above and below the baseline median (Lenz, 2013). To calculate the PEM statistic, data points in the treatment phase on the therapeutic side of the baseline are counted and then divided by the total number of points in the treatment phase. Scruggs and Mastropieri (1998) suggested the following criteria for evaluation: effect sizes of .90 and greater are indicative of very effective treatments; those ranging from .70 to .89 represent moderate effectiveness; those between .50 to .69 are debatably effective; and scores less than .50 are regarded as not effective

Results

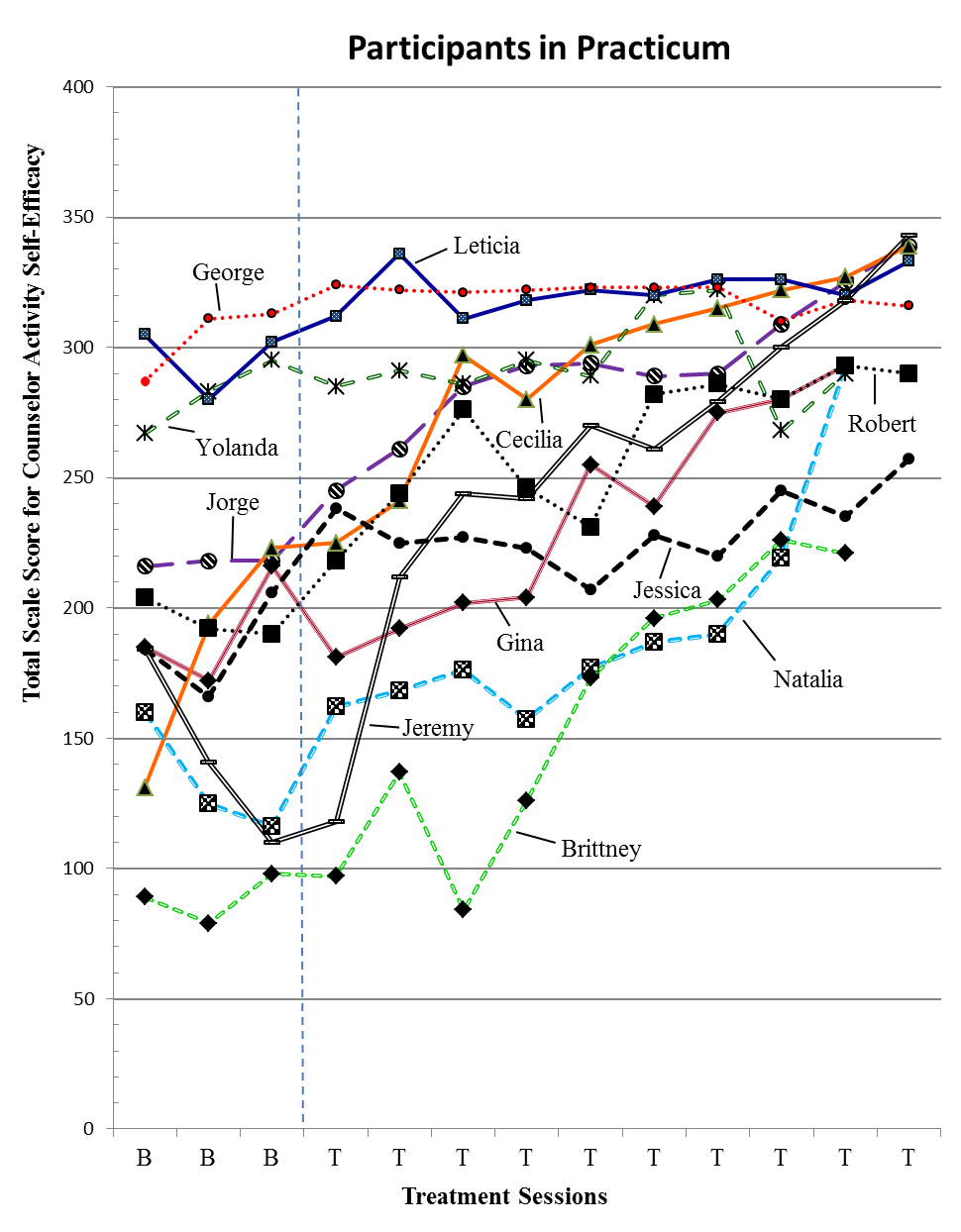

Figure 1 and Table 1 depict estimates of treatment effect using PEM across all participants. Detailed descriptions of participants’ experiences are provided below.

Participant 1

Jorge’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience involving triadic supervision and group supervision was very effective for improving counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Jorge’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123, which considers an individual to have low counseling self-efficacy for the CASES. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (1.00) indicated that 10 scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 217). Scores above the PEM line were within a 122-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring exploration skills.

Participant 2

Gina’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience involving triadic supervision and group supervision was moderately effective for improving counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Gina’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (0.77) indicated that seven scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 194). Scores above the PEM line were within a 99-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the second treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring exploration skills, session management and client distress.

Participant 3

Cecilia’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Cecilia’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (1.00) indicated that 10 scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 177). Scores above the PEM line were within a 162-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring exploration skills and session management.

Figure 1.

Graphical Representation of Ratings for Counselor Activity Self-Efficacy by Participants

Table 1

Participants’ Sessions and Their CASES Total Scale Score for Counselor Activity Self-Efficacy

![]()

Participant 4

Natalia’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving her counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, two of Natalia’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (1.00) indicated that nine scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 138). Scores above the PEM line were within a 155-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring exploration skills.

Participant 5

Yolanda’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Yolanda’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (0.90) indicated that nine scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 295). Scores above the PEM line were within a 27-point range. Trend analysis depicted a minimal level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring exploration skills.

Participant 6

Leticia’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving her counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Leticia’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (1.00) indicated that 10 scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 293). Scores above the PEM line were within a 43-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring client distress.

Participant 7

Robert’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Robert’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (1.00) indicated that 10 scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 197). Scores above the PEM line were within a 96-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring client distress.

Participant 8

George’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving his counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of George’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the counselor activity self-efficacy measure (1.00) indicated that ten scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 300). Scores above the PEM line were within a 24-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring exploration skills.

Participant 9

Jeremy’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving his counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, two of Jeremy’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (0.90) indicated that nine scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 142). Scores above the PEM line were within a 201-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the second treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring session management and client distress.

Participant 10

Brittney’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were moderately effective for improving her counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Brittney’s baseline measurements were below the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (0.88) indicated that eight scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 94). Scores above the PEM line were within a 132-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the fourth treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring session management.

Participant 11

Jessica’s ratings on the CASES illustrate that the practicum experience and triadic supervision were very effective for improving her counselor self-efficacy. Before the treatment phase began, three of Jessica’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the CASES with a total scale score of 123. Evaluation of the PEM statistic for the CASES (1.00) indicated that 10 scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (total scale score of 186). Scores above the PEM line were within a 71-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. The majority of improvement in confidence was found on items measuring exploration skills.

Discussion

The results of this study found that in all 11 investigated cases, the practicum experience ranged from moderately effective (PEM = .77) to very effective (PEM = 1.00) for improving or maintaining counselor self-efficacy during practicum coursework. For most participants, counseling self-efficacy continued to improve throughout the practicum experience as evidenced by high scores on items such as “Helping your client understand his or her thoughts, feelings and actions,” “Work effectively with a client who shows signs of severely disturbed thinking,” and “Help your client set realistic counseling goals.” Participants shared that the most helpful experiences during practicum to improve their counselor self-efficacy came from direct experiences with clients. This finding is consistent with Bandura’s (1977) conceptualization of direct mastery experiences where participants gain confidence with successful experiences of a particular activity. Participants also shared how obtaining feedback from clients on their outcomes and seeing their clients’ progress was important for their development as counselors. Other helpful experiences included processing counseling sessions with a peer during triadic supervision, and case conceptualization and treatment planning during group supervision. Obtaining feedback during triadic supervision from peers and instructors after observing recorded counseling sessions also was beneficial.

Qualitative benefits of supervision included vicarious learning experiences, peer-learning opportunities and better supervisor feedback (Borders et al., 2012). Findings from this study extend qualitative findings regarding benefits of the practicum experience and triadic supervision. The results of this study yielded promising findings related to the integration of triadic supervision into counseling graduate students’ practicum experiences. First, the practicum experience appeared to be effective for increasing and maintaining participant scores on the CSEA scale. Inspection of participant scores within treatment targets revealed that the practicum experience was very effective for nine participants and within the moderately effective range for two participants.

Lastly, informal conversations with participants indicate that triadic supervision provided participants with an opportunity to receive peer feedback. Participants also commented that weekly wellness checks were important due to stress from the practicum experience. Trends were observed for the group as a majority of participants improved self-efficacy consistently after their fourth treatment measure. In summary, direct services with clients, triadic supervision with a peer and group supervision as part of the practicum experience may assist counseling graduate students to improve self-efficacy.

Implications for Counseling Practice

There are several implications for practice. First, triadic supervision has been helpful when there is compatibility between supervisor and supervisees (Hein & Lawson, 2008). Compatibility between supervisees is helpful, as participants shared how having similar knowledge and experience contributed to their development. While all participants in the current study selected their partner for supervision, Hein and Lawson (2008) commented that the responsibility to implement and maintain clear and achievable support to supervisees lies heavily on supervisors. As a result, additional trainings should be offered to supervisors regarding clear, concise and supportive feedback. Such trainings and discussions can focus on clarity of roles and expectations for both supervisor and supervisee before triadic supervision begins. More training in providing feedback to peers in group supervision also can be beneficial as students learn to provide feedback to promote awareness of different learning experiences. We suggest that additional trainings will help practicum instructors and students identify ways to provide clear, constructive and effective feedback.

Practicum instructors can administer weekly or bi-weekly wellness checks and discuss responses on individual items on the Mental Well-Being Scale to monitor progress (Tennant et al., 2007). Additionally, counselor education programs would benefit from bringing self-efficacy to the forefront in the practicum experience as well as prepracticum coursework. Findings from the current study could be presented to students in group counseling and practicum coursework to facilitate discussion regarding how the practicum experience can increase students’ self-efficacy. Part of this discussion should focus on assessing baseline self-efficacy in order to help students increase perceptions of self-efficacy. As such, counselor educators can administer and interpret the CSEA scale with practicum students. There are numerous scale items (e.g., silence, immediacy) that can be used to foster discussions on perceived confidence in dealing with counseling-related issues. Finally, CACREP-accredited programs require 1 hour of weekly supervision and allow triadic supervision to fulfill this requirement. We recommend that CACREP and non-CACREP-accredited programs consider incorporating triadic supervision into the practicum experience and suggest that triadic supervision as part of the practicum experience might help students’ increase self-efficacy.

Implications for Counseling Research

The practicum experience seemed helpful for improving counseling students’ self-efficacy. However, information regarding reasons for this effectiveness of the practicum experience and triadic supervision was not explored. Qualitative research regarding the impact of the practicum experience on counselors’ self-efficacy can provide incredible insight into specific aspects of group or triadic supervision that increase self-efficacy. Second, more outcome-based research with ethnic minority counseling students is necessary. There might be aspects of group or triadic supervision that are conducive when working with Mexican American students (Cavazos, Alvarado, Rodriguez, & Iruegas, 2009). Third, exploring different models of group or triadic supervision to increase counseling self-efficacy is important. As one example, researchers could explore the impact of the Wellness Model of Supervision (Lenz & Smith, 2010) on counseling graduate students’ self-efficacy. Finally, all participants in our study attended a CACREP counseling program with mandatory individual or triadic supervision. Comparing changes in self-efficacy between students in CACREP and non-CACREP programs where weekly individual or triadic supervision outside of class is not mandatory would be important.

Limitations

There are several limitations that must be taken into consideration. First, we did not use an ABA design with withdrawal measures that would have provided stronger internal validity to evaluate changes to counselor self-efficacy (Lenz et al., 2012). Most practicum students in our study began internship immediately after the conclusion of the semester. As a result, collecting withdrawal measures in an ABA design would have tapped into students’ internship experiences. Second, although three baseline measurements are considered sufficient in single-case research (Lenz et al., 2012), employing five baseline measures might have allowed self-efficacy scores to stabilize prior to their practicum experience (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2015).

Conclusion

Based on results from this study, the practicum experience shows promise as an effective strategy to increase counseling graduate students’ self-efficacy. Implementing triadic supervision as part of the practicum experience for counseling students is a strategy that counselor education programs might consider. Provided are guidelines for counselor educators to consider when integrating triadic supervision into the practicum experience. Researchers also can use different methodologies to address how different aspects of the practicum experience influence counseling students’ self-efficacy. In summary, we regard the practicum experience with triadic supervision as a promising approach for improving counseling graduate students’ self-efficacy.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Bakar, A. R., Zakaria, N. S., & Mohamed, S. (2011). Malaysian counselors’ self-efficacy: Implication for career counseling. The International Journal of Business and Management, 6, 141–147. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v6n9p141

Bandura, A. (1977). Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Barbee, P. W., Scherer, D., & Combs, D. C. (2003). Prepracticum service-learning: Examining the relationship with counselor self-efficacy and anxiety. Counselor Education and Supervision, 43, 108–120.

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2004). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (3rd ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Borders, L. D. (2014). Best practices in clinical supervision: Another step in delineating effective supervision practice. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 68, 151–162.

Borders, L. D., Welfare, L. E., Greason P. B., Paladino, D. A., Mobley, A. K., Villalba, J. A., & Wester, K. L. (2012). Individual and triadic and group: Supervisee and supervisor perceptions of each modality. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51, 281–295.

Cavazos, J., Alvarado, V., Rodriguez, I., & Iruegas, J. R. (2009). Examining Hispanic counseling students’ worries: A qualitative approach. Journal of School Counseling, 7, 1–22.

Conn, S. R., Roberts, R. L., & Powell, B. M. (2009). Attitudes and satisfaction with a hybrid model of counseling supervision. Educational Technology and Society, 12, 298–306.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2016). 2016 CACREP standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2016-Standards-with-Glossary-rev-2.2016.pdf

Degges-White, S., Colon, B. R., & Borzumato-Gainey, C. (2013). Counseling supervision within a feminist framework: Guidelines for intervention. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 52, 92–105.

doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2013.00035.x

Greason, P. B., & Cashwell, C. S. (2009). Mindfulness and counseling self-efficacy: The mediating role of attention and empathy. Counselor Education and Supervision, 49, 2–19.

Halverson, S. E., Miars, R. D., & Livneh, H. (2006). An exploratory study of counselor education students’ moral reasoning, conceptual level, and counselor self-efficacy. Counseling and Clinical Psychology Journal, 3, 17–30.

Hein, S., & Lawson, G. (2008). Triadic supervision and its impact on the role of the supervisor: A qualitative examination of supervisors’ perspectives. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48, 16–31.

Hinkle, J. S. (1992). Computer-assisted career guidance and single-subject research: A scientist-practitioner approach to accountability. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70, 391–395.

Ikonomopoulos, J., Smith, R. L., & Schmidt, C. (2015). Integrating narrative therapy within rehabilitative programming for incarcerated adolescents. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93, 460–470. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00000.x

Larson, L. M., & Daniels, J. A. (1998). Review of the counseling self-efficacy literature. The Counseling Psychologist, 26, 179–218.

Lawson, G., Hein, S. F., & Getz, H. (2009). A model for using triadic supervision in counselor education preparation programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 48, 257–270.

Lawson, G., Hein, S. F., & Stuart, C. L. (2009). A qualitative investigation of supervisees’ experiences of triadic supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87, 449–457.

Lent, R. W., Cinamon, R. G., Bryan, N. A., Jezzi, M. M., Martin, H. M., & Lim, R. (2009). Perceived sources of changes in trainees’ self-efficacy beliefs. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46, 317–327. doi:10.1037/a0017029

Lent, R. W., Hill, E., & Hoffman, M. A. (2003). Development and validation of the counselor activity self-efficacy scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 97–108.

Lenz, A. S. (2013). Calculating effect size in single-case research: A comparison of nonoverlap methods. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 46, 64–73.

Lenz, A. S. (2015). Special issue editor’s introduction: Using single-case research designs to demonstrate evidence for counseling practices. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93, 387–393.

doi:10.1002/jcad.12036

Lenz, A. S., Perepiczka, M., & Balkin, R. S. (2013). Evidence of the mitigating effects of a support group for attitude toward statistics. Counseling Outcome Research & Evaluation, 4, 26–40. doi:10.1177/2150137812474000

Lenz, A. S., & Smith, R. L. (2010). Integrating wellness concepts within a clinical supervision model. The Clinical Supervisor, 29, 228–245. doi:10.1080/07325223.2020.518511

Lenz, A. S., Speciale, M., & Aguilar, J. V. (2012). Relational-cultural therapy intervention with incarcerated adolescents: A single-case effectiveness design. Counseling Outcome Research & Evaluation, 3, 17–29. doi:10.1177/2150137811435233

Lundervold, D. A., & Belwood, M. F. (2000). The best kept secret in counseling: Single-case (N = 1) experimental designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78, 92–102.

Ma, H. H. (2006). An alternative method for quantitative synthesis of single-subject researches: Percentage of data points exceeding the median. Behavior Modification, 30, 598–617.

Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (1998). Summarizing single-subject research: Issues and applications. Behavior Modification, 22, 221–242.

Sharpley, C. F. (2007). So why aren’t counselors reporting n = 1 research designs? Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 349–356.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., . . . Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health & Quality of Life

Outcomes, 5, 63. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

James Ikonomopoulos, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Javier Cavazos Vela is an LPC-Intern at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Wayne D. Smith is an Assistant Professor at the University of Houston–Victoria. Julia Dell’Aquila is a graduate student at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Correspondence concerning this article can be addressed to James Ikonomopoulos, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Department of Counseling, Main 2.200F, One West Univ. Blvd., Brownsville, TX 78520, james.ikonomopoulos@utrgv.edu.