Evaluating the Impact of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy on Hope and Clinical Symptoms With Latine Clients

Krystle Himmelberger, James Ikonomopoulos, Javier Cavazos Vela

We implemented a single-case research design (SCRD) with a small sample (N = 2) to assess the effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) for Latine clients experiencing mental health concerns. Analysis of participants’ scores on the Dispositional Hope Scale (DHS) and Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2) using split-middle line of progress visual trend analysis, statistical process control charting, percentage of non-overlapping data points procedure, percent improvement, and Tau-U yielded treatment effects indicating that SFBT may be effective for improving hope and mental health symptoms for Latine clients. Based on these findings, we discuss implications for counselor educators, counselors-in-training, and practitioners, which include integrating SFBT principles into the counselor education curriculum, teaching counselors-in-training how to use SCRDs to evaluate counseling effectiveness, and using the DHS and OQ-45.2 to measure hope and clinical symptoms.

Keywords: solution-focused brief therapy, single-case research design, hope, counselor education, clinical symptoms

Solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) is a strength-based and evidence-based intervention that helps clients focus on personal strengths, identify exceptions to problems, and highlight small successes (Berg, 1994; Gonzalez Suitt et al., 2016; Schmit et al., 2016). Schmit et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of SFBT for treating symptoms of internalizing disorders and identified that SFBT might be effective in creating short-term changes in clients’ functioning. Other researchers (e.g., Gonzalez Suitt et al., 2016; Novella et al., 2020) also found that SFBT can be helpful with clients from various cultural backgrounds and with different presenting symptoms such as anxiety. Yet, there is scant research evaluating the efficacy of SFBT on subjective well-being with Latine (a gender-neutral term that is more consistent with Spanish language and grammar than Latinx) populations. Additionally, there is not a lot of research that investigates the effectiveness of counseling practices among counselors-in-training (CITs) at community counseling clinics with culturally diverse clients. Although the costs are relatively low, the type of supervision, training, and feedback given to CITs provides community clients with the potential for effective counseling services. However, only a few researchers (e.g., Schuermann et al., 2018) have explored the efficacy of counseling services within a community counseling training clinic. Therefore, empirical research is needed regarding the efficacy of SFBT with Latine populations in a counseling training clinic at a Hispanic Serving Institution.

The Latine population is a fast-growing group in the United States and makes up approximately 19% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). Despite this growth, members of this culturally diverse population continue to face individual, interpersonal, and institutional challenges (Ponciano et al., 2020; Vela, Lu, et al., 2014). Because Latine individuals experience discrimination and negative environments (Cheng & Mallinckrodt, 2015; Ponciano et al., 2020; Ramos et al., 2021), perceive lack of support from counselors and teachers in K–12 school environments (A. G. Cavazos, 2009; Vela-Gude et al., 2009), and experience microaggressions (Sanchez, 2019), they are likely to experience greater mental health challenges. Researchers have identified numerous internalizing and externalizing symptoms that represent Latine individuals’ mental health experiences, likely putting them at greater risk for mental health impairment and poor psychological functioning (Cheng et al., 2016). Researchers also detected that Latine youth had similar or higher prevalence rates of internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression) when compared with their White counterparts (Merikangas et al., 2010; Ramos et al., 2021). Given that Latine individuals might be at greater risk for psychopathology and their mental health needs are often unaddressed because they do not seek mental health services (Mendoza et al., 2015; Sáenz et al., 2013), further evaluation of the effectiveness of counseling practices for this population is necessary.

Fundamental Principles of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy

Developed from the clinical practice of Steven de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, SFBT is a future-focused and goal-directed approach that focuses on searching for solutions and is created on the belief that clients have knowledge and resources to resolve their problems (Kim, 2008). Counselors’ therapeutic task is to help clients imagine how they would like things to be different and what it will take to facilitate small changes. Counselors take active roles by asking questions to help clients look at the situation from different perspectives and use techniques to identify where the solution occurs (de Shazer, 1991; Proudlock & Wellman, 2011).

In SFBT, counselors amplify positive constructs and solutions by using specific strategies and techniques to build on positive factors (Tambling, 2012). Common techniques include the miracle question, scaling questions, exceptions, experiments, and compliments, which are designed to help clients identify personal strengths and cultivate what works (de Shazer, 1991; Proudlock & Wellman, 2011). We agree with Vela, Lerma, et al. (2014) that counselors can use postmodern and strength-based theories (e.g., SFBT) to develop positive psychology constructs such as hope, positive emotions, and subjective well-being. SFBT might be useful to help Latine clients identify strengths, build on what works, and reconstruct a positive future outcome.

Several researchers have indicated the efficacy of SFBT for treating various issues with different populations (Bavelas et al., 2013; Kim, 2008). Schmit et al. (2016) conducted a meta-analysis with 26 studies examining the effectiveness of SFBT for treating symptoms of depression and anxiety. They found that SFBT resulted in moderately successful treatment; however, adults’ treatment effects were 5 times larger when compared to those of youth and adolescents. One possible explanation was that SFBT may require clients’ maturity to integrate and understand SFBT concepts and techniques. Researchers also concluded that the impact of SFBT may be effective in producing short-term changes that will lead to further gains in symptom relief as well as psychological functioning (Schmit et al., 2016).

Brogan et al. (2020) commented that “there are limited studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of this method with the Latine . . . population” (p. 3). However, we postulate that SFBT principles are compatible with Latine cultural and family characteristics (Lerma et al., 2015; Oliver et al., 2011). There are several reasons that make SFBT an appropriate fit for working with the Latine population. For instance, researchers suggest that understanding family dynamics or familismo when evaluating mental health and overall well-being with the Latine population is important (Ayón et al., 2010). Familismo is strong family ties to immediate and extended families in the Latine culture.

In a study investigating Latine families, Priest and Denton (2012) found that family cohesion and family discord were associated with anxiety. Calzada et al. (2013) also highlighted that although family support can positively impact mental health, family can also become a source of conflict and stress, which might result in poor mental health. By using SFBT principles, counselors can help Latine clients identify how familismo is a source of strength through sense of loyalty and cooperation among family members (Oliver et al., 2011).

Another emphasis with SFBT that aligns with the Latine culture is the focus on personal and family resiliency. Because Latine individuals must navigate individual, interpersonal, and institutional challenges (Vela et al., 2015), they have natural resilience and coping skills that align with an SFBT approach. Counselors can use exceptions, scaling questions, and compliments to help Latine individuals discover their inherent resilience and continue to persevere through personal adversity.

Constructs: Hope and Clinical Symptoms

Consistent with a dual-factor model of mental health (Suldo & Shaffer, 2008), we focused on two outcomes: hope and clinical symptoms. First, hope, which has been associated with subjective well-being among Latine populations (Vela, Lu, et al., 2014), refers to a pattern of thinking regarding goals (Snyder et al., 2002). Snyder et al. (1991) proposed Hope Theory with pathways thinking and agency thinking. Pathways thinking refers to individuals’ plans to pursue desired objectives (Feldman & Dreher, 2012), while agency thinking refers to perceptions of ability to make progress toward goals (Snyder et al., 1999). Researchers found that hope was positively related to meaning in life, grit, and subjective happiness among Latine populations (e.g., Vela, Lerma, et al., 2014; Vela et al., 2015). Other researchers (e.g., Vela, Ikonomopoulos, et al., 2016) have explored the impact of counseling interventions on hope among Latine adolescents and survivors of intimate partner violence. Given the association between hope and other positive developmental outcomes among Latine populations, examining this construct as an outcome in clinical mental health counseling services is important.

In addition to hope as an indicator of subjective well-being, we used the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2; Lambert et al., 1996) to measure clinical symptoms in the current study for several reasons, including its strong psychometric properties, its use in the counseling training clinic where this study took place, and its use in other studies that evaluate the efficacy of counseling or psychotherapy and show evidence based on relation to other variables such as depression and clinical symptoms (Ekroll & Rønnestad, 2017; Ikonomopoulos et al., 2017; Soares et al., 2018). The OQ-45.2 measures three areas that are central to individual psychological functioning: Symptom Distress, Interpersonal Relations, and Social Role Performance.

Purpose of Study and Rationale

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of SFBT for increasing hope and decreasing clinical symptoms among Latine clients. We implemented an SCRD (Lenz et al., 2012) to identify and explore changes in hope and clinical symptoms as a result of participation in SFBT. We evaluated the following research question: To what extent is SFBT effective for increasing hope and decreasing clinical symptoms among Latine clients who receive services at a community counseling clinic?

Methodology

We implemented a small-series (N = 2) AB SCRD with Latine clients admitted into treatment at an outpatient community counseling clinic to evaluate the treatment effect associated with SFBT for increasing hope and reducing clinical symptoms. The rationale for using an SCRD was to explore the impact of an intervention that might help Latine clients at a community counseling training clinic. We used criterion sampling to recruit participants who (a) sought counseling services at a community counseling clinic, (b) had internalizing symptoms related to anxiety and depression, and (c) worked with a CIT who was supervised by faculty in a clinical mental health counseling program.

Participants

Participants in this study were two adults admitted into treatment at an outpatient community counseling clinic in the Southern region of the United States. Both participants identified as Hispanic; one identified as a female and the other identified as a male. During informed consent, we explained to participants that they would be assigned pseudonyms to protect their identity. The participants consented to both treatment and inclusion in the research study.

The two participants for this study were selected to participate in this study because of their presenting internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety) and fit for SFBT principles. Because we wanted to increase hope among these Latine clients, we felt that SFBT was an appropriate approach. The fundamental principles of SFBT align with attempting to facilitate hope among clients with various symptoms because it helps clients view mental health challenges as opportunities to cultivate strengths, explore solutions, and identify new skills (Bannik, 2008; Joubert & Guse, 2021). SFBT practitioners also posit that clients can recreate their future, cultivate resilience, and construct solutions, which aligns well with tenets of the Latine culture (J. Cavazos et al., 2010). In the first session prior to treatment, both clients indicated that they believed they were in control of their future mental health and that they could construct solutions. We also informed them that SFBT focuses on future solutions as opposed to focusing on problems and the past. Because these clients indicated a willingness to explore their future through co-constructing solutions, they were a good fit for SFBT principles in counseling.

Participant 1

“Mary” was a 31-year-old Latine female with a history of receiving student mental health services at a university counseling clinic. Mary sought individual counseling services because of a recent separation with the father of her three children who was emotionally abusive. Anxiety associated with this separation was compounded by traumatic experiences from 5 years prior. Mary stated that her Latine culture generated greater symptoms of anxiety while recognizing her new role as a single mother. Mary’s therapeutic goals and focus of treatment were to reduce clinical symptoms of anxiety as well as improve self-identity and self-esteem.

Participant 2

“Joel” was a 20-year-old Latine male with a history of receiving mental health services for symptoms of depression. Joel’s therapeutic goals and focus of treatment were to reduce clinical symptoms of anxiety and associated anger as well as improve self-esteem. Joel reported being a victim of domestic violence and child abuse. Additionally, Joel expressed distress with revealing his sexual identity because of patriarchal roles in the Latine culture that may result in rejection.

Measurements

Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2)

The OQ-45.2 is a 45-item self-report outcome questionnaire (Lambert et al., 1996) for adults 18 years of age and older. Each item is associated with a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from never (1) to almost always (5). We used the total score for the OQ-45, which was calculated by summing the three subscale scores with a possible total score ranging from 0–180. Higher scores are reflective of more severe distress and impairment. Sample response items include “I feel worthless” and “I have trouble getting along with friends and close acquaintances.” This assessment was designed to include items relevant to three domains central to mental health: Symptom Distress, Interpersonal Relations, and Social Role Performance (Lambert et al., 1996).

Researchers have examined structural validity and reliability. Coco et al. (2008) used a confirmatory factor analysis to test various models of the factorial structure. They found support for the four-factor, bi-level model, which means that each survey item relates to a subscale as well as an overall maladjustment score. Amble et al. (2014) also examined psychometric properties using confirmatory factor analysis, concluding that “the total score of the OQ-45 is a reliable and valid measure for assessing therapy progress” (p. 511). Their findings are like Boswell et al.’s (2013) findings that found support for the validity of the total OQ-45 score. There is also evidence based on relation to other clinical outcomes measured by the General Severity Index from the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised, the Beck Depression Inventory, and Social Adjustment Scale (Lambert et al., 1996). Additionally, previous psychometric evaluations have revealed evidence of reliability through reliability indices such as Cronbach’s alpha (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2017; Kadera et al., 1996; Umphress et al., 1997). Internal consistency estimates through Cronbach’s alpha range from .71 to .92 (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2017; Lambert et al., 1996).

Hope

The Dispositional Hope Scale (DHS; Snyder et al., 1991) is a self-report inventory to measure participants’ attitudes toward goals and objectives. Participants responded to eight statements evaluated on an 8-point Likert scale ranging from definitely false (1) to definitely true (8). We used the total Hope score, which was obtained by summing scores for both Agency and Pathways subscales. Total scores range from 8–64, with higher scores indicating greater levels of hope. Sample response items include “I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are important to me” and “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam.”

Researchers have examined structural validity and reliability. Galiana et al. (2015) used confirmatory factor analysis to identify that a one-factor structure was the best fit. There is also evidence of validity with other theoretically relevant constructs such as meaning in life (Vela et al., 2017) as well as evidence of concurrent and discriminant validity with other measures related to self-esteem, state hope, and state positive and negative affect (Snyder et al., 1996). There is also evidence of factorial invariance (Nel & Boshoff, 2014), suggesting that factor structure is similar across gender and racial ethnic groups. Additionally, there is evidence of reliability (e.g., internal consistency) as indicated through Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .85 to .86 (Snyder et al., 2002; Vela et al., 2015).

Study Setting

During the present study, each participant was involved in individual counseling at a community counseling clinic. The facility, located in the Southern region of the United States, provides free counseling services to community members. Individual and group sessions are free and last approximately 45 to 50 minutes. The community counseling clinic offers preventive and early treatment for developmental, emotional, and interpersonal difficulties for community members. CITs at the community counseling clinic are graduate counseling students enrolled in practicum or internship.

Interventionists

Krystle Himmelberger, who was the CIT in the current study, adapted strength-based interventions designed to facilitate positive feelings by helping clients set goals, focus on the future, and find solutions rather than problems. She was a CIT in a clinical mental health counseling program. Prior to the study, she selected and designed interventions and activities according to specific guidelines from SFBT manuals and sources (Buchholz Holland, 2013; de Shazer et al., 2007; Trepper et al., 2010).

James Ikonomopoulos and Javier Cavazos Vela were faculty counseling supervisors who monitored sessions and provided weekly supervision to maintain fidelity of SFBT interventions. Bavelas et al. (2013) suggested that live supervision may provide a second set of clinical eyes to help CITs. Himmelberger received weekly supervision to ensure procedural and treatment adherence (Liu et al., 2020). Furthermore, videotaped supervision and transcriptions provided her with the ability to communicate between sessions. These measures were used to enhance treatment fidelity by focusing on quality and competency.

SFBT Principles and Intervention

Participants received six to nine sessions of individual SFBT using the description of techniques and activities in the following resources: More Than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (de Shazer et al., 2007), Solution-Focused Therapy Treatment Manual for Working With Individuals (Trepper et al., 2010), and “The Lifeline Activity With a ‘Solution-Focused Twist’” (Buchholz Holland, 2013). We used the following SFBT principles to guide the intervention: focus on specific topics, a positive and co-constructed therapeutic relationship, and questioning techniques (Trepper et al., 2010). First, Himmelberger focused on specific topics such as preferred future, strengths, confidence in finding solutions, and exceptions. She used future-specific and solution-focused language in each session to help clients focus on their preferred futures. Second, she developed a positive therapeutic relationship with clients through shared trust and co-construction of counseling experiences. She was positive and helpful, and she helped instill optimism and hope in her clients. A positive therapeutic relationship was evidenced based on her report as well as live supervision and reviews of session recordings. Finally, Himmelberger used questioning techniques that focused on clients’ strengths, exceptions, and coping skills. She used questioning techniques that helped clients focus on progress toward their preferred future and future-oriented solutions.

The techniques she used included looking for previous solutions, exceptions, the miracle question, scaling questions, compliments, future-oriented questions, and “so what is better” questions. Himmelberger used looking for previous solutions to help clients identify their previous coping strategies to cope with the problem. Based on Himmelberger’s report in supervision sessions, both clients commented that they were surprised that they had been successful in the past when the problem did not exist. She also used exceptions to help clients identify what was different when the problem did not exist. Additionally, she used present- and future-oriented questions to help clients focus on future solutions. This was an important technique as clients were not used to ignoring the problem. When clients provided updates on their progress toward their goals, Himmelberger used compliments to validate what clients were doing well. Using compliments helped cultivate a positive therapeutic relationship with these clients.

Finally, with the miracle question, she asked clients to provide details about their preferred future and what that would look like. She followed up with a question about constructing solutions regarding what work it would take to make that preferred future happen. Then in each session, she conducted progress checks toward that preferred future by asking scaling questions (On a scale from 1–10, where are you now with progress toward your preferred future?) and questions about “what is better” (What is better now when compared to last week?). She complimented clients’ progress toward that preferred future.

Procedures

We used AB SCRD to determine the effectiveness of an SFBT treatment program (Lundervold & Belwood, 2000; Sharpley, 2007) using scores on the DHS and OQ-45.2 total scale as outcome measures (Lambert et al., 1996). The two participants who were assigned to Himmelberger did not begin counseling until they consented to treatment and the research study. In other words, they did not receive counseling services prior to participation in this study. After 4 weeks of data collection, the baseline phase of data collection was completed. Participants did not receive counseling services during the baseline period.

The treatment phase began after the fourth baseline measure. At the conclusion of each individual session, participants completed the DHS and OQ-45.2. Himmelberger collected and stored the measures in each participant’s folder in a locked cabinet in the clinic. After the 12th week of data collection, the treatment phase of data collection was completed, at which point the SFBT intervention was withdrawn.

A percentage of non-overlapping data (PND) procedure was used to analyze quantitative data (Scruggs et al., 1987). A visual representation of change over time is graphically represented with a split-middle line of progress visual trend analysis showing data points from each phase (Lenz, 2015). Statistical process control charting was used to determine whether the characteristics of treatment phase data were beyond the realm of random occurrence with 99% confidence (Lenz, 2015). An interpretation of effect size was estimated using Tau-U to complement PND analysis (Lenz, 2015; Sharpley, 2007).

Data Collection and Analysis

We implemented the PND (Scruggs et al., 1987) to analyze scores on the Hope and OQ-45.2 scales across phases of treatment. The PND procedure yields a proportion of data in the treatment phase that overlaps with the most conservative data point in the baseline phase. PND calculations are expressed in a decimal format that ranges between 0 and 1, with higher scores representing greater treatment effects (Lenz, 2013).

Upon considering the percentage of data exceeding the median procedure (Ma, 2006), we selected the PND because it is considered a robust method of calculating treatment effectiveness (Lenz, 2013). This metric is conceptualized as the percentage of treatment phase data that exceeds a single noteworthy point within the baseline phase. Because we aimed for an increase in DHS scores, the highest data point in the baseline phase was used. Finally, given that we aimed for a decrease in OQ-45.2 total scale scores, the lowest data point in the baseline was used (Lenz, 2013). To calculate the PND statistic, data points in the treatment phase on the therapeutic side of the baseline are counted and then divided by the total number of points in the treatment phase (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2016).

Estimates of Effect Size and Clinical Significance

PND values are typically interpreted using the estimation of treatment effect provided by Scruggs and Mastropieri (1998) wherein values of .90 and greater are indicative of very effective treatments, those ranging from .70 to .89 represent moderate effectiveness, those between .50 to .69 are debatably effective, and scores less than .50 are regarded as not effective (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2015, 2016). Tau-U values are typically interpreted using the estimation of treatment effect provided by Vannest and Ninci (2015) wherein Tau-U magnitudes can be interpreted as small (≤ .20), moderate (.20–.60), large (.60–.80), and very large (≥ .80). These procedures were completed for each participant’s scores on the Hope and OQ-45.2 scales.

Clinical significance was determined in accordance with Lenz’s (2020a, 2020b) calculations of percent improvement (PI) values. Percent improvement values greater than 50% were interpreted as representing clinically significant improvement with large effect sizes, 25% to 49% were interpreted as slightly improved without clinical significance, and less than 25% represented no clinical significance. Lenz (2021) also recommended for researchers to provide sufficient context and visual representation when interpreting and reporting clinical significance. As one example, without context and visual representation, researchers could interpret a PI value of 49% as not having clinical significance.

Results

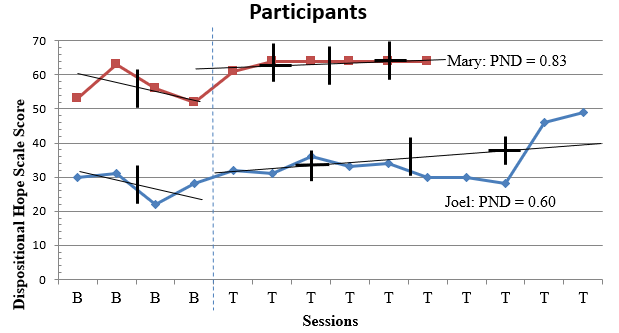

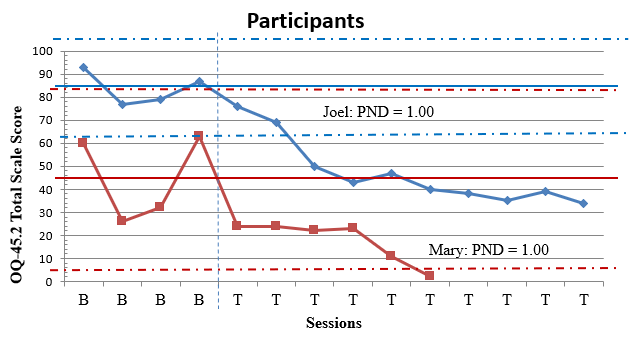

A detailed description of participants’ experiences is provided below. Figure 1 depicts estimates of treatment effect on the DHS; Figure 2 depicts estimates of treatment effect on the OQ-45.2 total scale.

Figure 1

Ratings for Hope by Participants With Split-Middle Line of Progress

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.

Figure 2

Ratings for Mental Health Symptoms on OQ-45.2 by Participants with Statistical Process Control Charting

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.

Participant 1

Data for Mary is represented in Figures 1 and 2 as well as Tables 1 and 2. A comparison of level of Hope across baseline (M = 56.00) and intervention phases (M = 63.50) indicated notable changes in participant scores evidenced by an increase in mean DHS scores over time. Variation between scores in baseline (SD = 3.50) and intervention (SD = 0.83) indicated differential range in scores before and after the intervention. Data in the baseline phase trended downward toward a contra-therapeutic effect over time. Dissimilarly, data in the intervention phase trended upward toward a therapeutic effect over time. Comparison of baseline level and trend data with the first three observations in the intervention phase did suggest immediacy of treatment response for the participant. Data in the intervention phase moved into the desired range of effect for scores representing Hope. Overall, visual inspection of Mary’s ratings on the DHS (see Figure 1) indicates that most of her scores in the treatment phase were higher than her scores in the baseline phase.

Mary’s ratings on the DHS illustrate that the treatment effect of SFBT was moderately effective for improving her DHS score. Evaluation of the PND statistic for the DHS score measure (0.83) indicated that five out of six scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (DHS score of 63). Mary successfully improved Hope during treatment as evidenced by improved scores on items such as “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam,” “I can think of ways to get the things in life that are important to me,” and “I meet the goals that I set for myself.” Scores above the PND line were within a 1-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. This finding is corroborated by the associated Tau-U value (τU = 0.92), which suggested a very large degree of change in which the null hypothesis about intervention efficacy for Mary could be rejected (p = .02). Also, interpretation of the clinical significance estimate of PI is that 13.39% improvement is not clinically significant (Lenz, 2020a, 2020b). See Table 1 for information regarding PND, Tau-U, and PI. Although the PI value is considered not clinically significant, it is important to contextualize this finding within visual inspection of Mary’s Hope scores in Figure 1. Because Mary had moderately high levels of Hope in the baseline phase, her room for improvement based on the ceiling effect as related to Hope was not high. In other words, in the context of Mary’s treatment and visual inspection of her scores, the SFBT intervention helped Mary move from good to better. In the context of Mary’s treatment and a visual representation of her scores on the DHS (see Figure 1), the SFBT intervention had some level of convincingness, which means that some amount of change in Hope occurred for Mary (Kendall et al., 1999; Lenz, 2021).

Table 1

Ratings for Hope by Participants

| Age | Ethnicity | Gender | Baseline Data | Intervention Data | PND | τU (p) |

PI |

|||

| M | SD | M | SD | |||||||

| Mary | 31 | Latina | Female | 56.00 | 3.50 | 63.50 | 0.83 | 83% | 0.92 (.02) | 13.39% |

| Joel | 20 | Latino | Male | 27.75 | 2.87 | 34.90 | 5.26 | 60% | 0.70 (.05) | 25.75% |

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.

Table 2

Ratings for OQ-45.2 Total Scale Score by Participants

| Age | Ethnicity | Gender | Baseline Data | Intervention Data | PND | τU (p) |

PI |

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||||||

| Mary | 31 | Latina | Female | 45.25 | 16.25 | 17.67 | 7.44 | 100% | −1.00 (.01) | 60.95% | |

| Joel | 20 | Latino | Male | 84.00 | 6.00 | 47.10 | 10.74 | 100% | −1.00 (.004) | 43.93% | |

Note. PND = Percentage of Non-overlapping Data.

Before treatment began, one of Mary’s baseline measurements was above the cut-score guideline on the OQ-45.2 of a total scale score of 63, which indicates symptoms of clinical significance. Comparison of level of clinical symptoms across baseline (M = 45.25) and intervention phases (M = 17.67) indicated notable changes in participant scores evidenced by a decrease in mental health symptom scale scores over time. Variation between scores in baseline (SD = 16.25) and intervention (SD = 7.44) indicated differential range in scores before and after the intervention. Data in the baseline phase trended upward toward a contra-therapeutic effect over time. Dissimilarly, data in the intervention phase trended downward toward a therapeutic effect over time. Comparison of baseline level and trend data with the first three observations in the intervention phase did suggest immediacy of treatment response for the participant. Data in the intervention phase moved into the desired range of effect for scores representing mental health symptoms.

Mary’s ratings on the OQ-45.2 illustrate that the treatment effect of SFBT was very effective for decreasing her total scale score measuring mental health symptoms. Evaluation of the PND statistic for the OQ-45.2 total scale score measure (1.00) indicated that all six scores were on the therapeutic side below the baseline (total scale score of 26). Mary successfully reduced clinical symptoms during treatment as evidenced by improved scores on items such as “I am a happy person,” “I feel loved and wanted,” and “I find my work/school satisfying.” This contention became most apparent after the first treatment session when Mary continuously scored lower on a majority of symptom dimensions such as Symptom Distress, Interpersonal Relations, and Social Role Performance. Scores below the PND line were within a 24-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. This finding is corroborated by the associated Tau-U value (τU = −1.0), which suggested a very large degree of change in which the null hypothesis about intervention efficacy for Mary could be rejected (p = .01). An analysis of statistical process control charting revealed that one data point in the treatment phase was beyond the realm of random occurrence with 99% confidence. This finding also corresponds with interpretation of the clinical significance estimate of PI that 60.95% improvement is clinically significant (Lenz, 2020a, 2020b). See Table 2 for information regarding PND, Tau-U, and PI. In the context of Mary’s treatment and a visual representation of Mary’s scores on the OQ-45.2 (see Figure 2), the SFBT intervention had a high level of convincingness, which means that a considerable amount of change in clinical symptoms occurred for Mary (Kendall et al., 1999; Lenz, 2021).

Participant 2

Data for Joel is represented in Figures 1 and 2 as well as Tables 1 and 2. Comparison of level of Hope across baseline (M = 27.75) and intervention phases (M = 34.90) indicated notable changes in participant scores evidenced by an increase in mean DHS scores over time. Variation between scores in baseline (SD = 2.87) and intervention (SD = 5.26) indicated differential range in scores before and after the intervention. Data in the baseline phase trended downward toward a contra-therapeutic effect over time. Dissimilarly, data in the intervention phase trended upward toward a therapeutic effect over time. Comparison of baseline level and trend data with the first three observations in the intervention phase did suggest immediacy of treatment response for the participant. Data in the intervention phase moved into the desired range of effect for scores representing Hope.

Joel’s ratings on the DHS illustrate that the treatment effect of SFBT was debatably effective for improving his DHS score. Evaluation of the PND statistic for the DHS score measure (0.60) revealed that six out of ten scores were on the therapeutic side above the baseline (DHS score of 31). Joel successfully improved his Hope during treatment as evidenced by improved scores on items such as “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam,” “I can think of ways to get the things in life that are important to me,” and “I meet the goals that I set for myself.” Scores above the PND line were within an 18-point range. Trend analysis depicted a steady level of scores following the first treatment measure, with scores vacillating around the baseline score until the eighth treatment measure. This finding is corroborated by the associated Tau-U value (τU = 0.70), which suggested a large degree of change in which the null hypothesis about intervention efficacy for Joel could be rejected (p = .047). This finding also corresponds with interpretation of the clinical significance estimate of PI that 25.75% is slightly improved but not clinically significant (Lenz, 2020a, 2020b). One explanation for the lack of clinical significance and moderate effect size is the limited nature of the intervention. Based on results from visual depiction of Joel’s levels of Hope across treatment (see Figure 1), we suspect that this trend would have continued if he had received additional sessions of an SFBT intervention. His treatment was trending in a positive trajectory. In the context of Joel’s treatment and a visual representation of his scores on the DHS (see Figure 1), the SFBT intervention had a moderate level of convincingness, which means that a considerable amount of change in Hope occurred for Joel (Kendall et al., 1999; Lenz, 2021).

Before treatment began, all four of Joel’s baseline measurements were above the cut-score guideline on the OQ-45.2 of a total scale score of 63, which indicates symptoms of clinical significance. Comparison of level of clinical symptoms across baseline (M = 84.00) and intervention phases (M = 47.10) indicated notable changes in participant scores evidenced by a decrease in mental health symptom scale scores over time. Variation between scores in baseline (SD = 6.00) and intervention (SD = 10.74) indicated differential range in scores before and after intervention. Data in the baseline phase trended upward toward a contra-therapeutic effect over time. Dissimilarly, data in the intervention phase trended downward toward a therapeutic effect over time. Comparison of baseline level and trend data with the first three observations in the intervention phase did suggest immediacy of treatment response for the participant. Data in the intervention phase moved into the desired range of effect for scores representing mental health symptoms.

Joel’s ratings on the OQ-45.2 illustrate that the treatment effect of SFBT was very effective for decreasing his total scale score measuring clinical symptoms. Evaluation of the PND statistic for the total scale score measure (1.00) indicated that all 10 scores were on the therapeutic side below the baseline (total scale score of 77). Joel successfully reduced clinical symptoms during treatment as evidenced by improved scores on items such as “I am a happy person,” “I feel loved and wanted,” and “I find my work/school satisfying.” This contention became most apparent after the first treatment session when Joel continuously scored lower on a majority of symptom dimensions such as Symptom Distress, Interpersonal Relations, and Social Role Performance. Scores below the PND line were within a 41-point range. Trend analysis depicted a consistent level of improvement following the first treatment measure. This finding is corroborated by the associated Tau-U value (τU = −1.0), which suggested a very large degree of change in which the null hypothesis about intervention efficacy for Joel can be rejected (p = .004). An analysis of statistical process control charting revealed that eight data points in the treatment phase were beyond the realm of random occurrence with 99% confidence. This finding also corresponds with interpretation of the clinical significance estimate that 43.93% of improvement is slightly improved but not clinically significant (Lenz, 2020a, 2020b). Considering contextual evidence from the intervention as well as data visualization of Figure 2, it was clear that Joel experienced a downward trajectory in clinical symptoms. If he had received additional SFBT sessions, we suspect that he would have continued to experience a reduction in clinical symptoms. In the context of Joel’s treatment and a visual representation of his scores on the OQ-45.2 (see Figure 2), the SFBT intervention had a high level of convincingness, which means that a considerable amount of change in Hope occurred for Joel (Kendall et al., 1999; Lenz, 2021).

Discussion

The purpose of this exploratory study was to examine the impact of SFBT on clinical symptoms and hope among Latine clients. The results yield promising findings and preliminary evidence about the efficacy of SFBT as an intervention for promoting positive change across two Latine clients’ clinical symptoms and hope. The scores varied for each outcome variable, and this is likely related to the length and duration of the intervention as well as each participant’s personal characteristics (Callender et al., 2021) and relationship to their counselor (Liu et al., 2020). Findings from the current study also lend further support regarding the efficacy among CITs who aim to impact clients’ psychological functioning at a community counseling training clinic.

The findings for clinical symptoms showed a trend toward reduction in clinical symptoms across 8 weeks of SFBT. Both participants reported statistically significant improvements (p < .05) in reductions of clinical symptoms on the OQ-45.2. In both cases, the SFBT intervention was within the range of very large treatment effectiveness and clinical significance for improving symptoms of psychopathology. Results from the PND and PI confirmed that these participants experienced reduced clinical symptoms. It appears that there was a steady progression of improvement for these participants after their second treatment session. During this phase of treatment, Himmelberger used techniques such as exceptions to the problem and scaling questions to help participants recognize inner resources and personal strengths, analyze current levels of functioning, and visualize their preferred future (de Shazer, 1991).

In review of counseling session recordings and in supervision, Himmelberger commented that both Joel and Mary provided feedback throughout SFBT that they appreciated the opportunity to focus on small successes, personal strengths, and exceptions to their problems, and the use of scaling questions to assess and track their progress. They also commented that they appreciated how they were able to conceptualize family as a source of strength and element of resiliency (J. Cavazos et al., 2010; Oliver et al., 2011). Researchers have found that using SFBT techniques such as miracle and exceptions questions can help clients reduce negative affect (Brogan et al., 2020; Neipp et al., 2021). Our findings also are like those of Schmit et al. (2016), who found that SFBT may be effective for treating symptoms of internalizing disorders, and Oliver et al. (2011), who commented that SFBT can help Mexican Americans cultivate familismo.

The findings for Hope showed a visual trend toward increased levels of Hope across 8 weeks of SFBT. Both participants reported statistically significant improvements (p < .05) in Hope on the DHS. In both cases, the SFBT intervention was within the range of debatable effectiveness and slight improvement without clinical significance for improving symptoms of Hope. Mary’s rating on the DHS indicates the treatment was moderately effective and PI was not clinically significant. When visualizing Mary’s rating on the DHS, we see that Mary had high levels of Hope in the baseline phase, which means that she did not have much room to improve in the treatment phase. Contextualizing Mary’s treatment and using a visual representation of her scores on the DHS (see Figure 1), we infer that the SFBT intervention had some level of convincingness, which means that some amount of change in Hope occurred for Mary (Kendall, 1999; Lenz, 2021). Additionally, Joel’s rating on the DHS indicate that the treatment effect was debatably effective with a PI that is slightly improved but not clinically significant. When looking closely at Joel’s scores, we see that Joel experienced trends in a positive trajectory. In the context of his treatment and a visual representation of his scores on the DHS (see Figure 1), the SFBT intervention had a moderate level of convincingness, which means that a considerable amount of change in Hope occurred (Kendall, 1999; Lenz, 2021).

Suldo and Shaffer (2008) argued that using a dual-factor model of mental health with indicators of subjective well-being (e.g., hope) and illness (e.g., clinical symptoms) allows researchers and practitioners to measure and understand complete mental health. Although a client’s psychopathology might decrease, subjective well-being might not improve with the same effect. Findings from SFBT treatment with Joel and Mary support a dual-factor model that suggests indicators of personal wellness and psychopathology are different parts of mental health and are important to consider in treatment (Vela, Lu, et al., 2016). For Joel and Mary, SFBT appeared to be efficacious for slightly increasing and maintaining scores on the DHS. Our findings support Joubert and Guse (2021), who recommended SFBT to facilitate hope and subjective well-being among clients. When clients can think about solutions, identify exceptions to their problems, and think about their preferred future, they might be more likely to develop hope for their future as well as improve subjective well-being (Joubert & Guse, 2021).

The findings from this study lend further support regarding the effectiveness of counseling services at a community counseling training clinic. Our findings are like Schuermann et al.’s (2018) findings that lend support for the efficacy of counseling services in a Hispanic-serving counselor training clinic and Dorais et al.’s (2020) findings of counseling students’ motivational interviewing techniques at a university addiction training clinic. Faculty supervision, group supervision, and live supervision have all been associated with increases in counseling interns’ self-efficacy to provide quality counseling services. Himmelberger received weekly supervision and consultation on SFBT principles as well as SCRD principles. It is possible that these forms of supervision helped her provide effective counseling services. Our findings also support the need to continue to design research studies to evaluate the impact of counseling services at community counseling training clinics with clients of different cultural backgrounds and different presenting symptoms.

Implications for Counselor Educators and Counselors-in-Training

Based on our findings, we propose a few recommendations for counselor educators, CITs, and practitioners. First, our study provides evidence that CITs at community counseling centers can provide effective treatments with culturally diverse clients with moderate internalized symptoms such as depression and anxiety. As a result, SFBT can be taught and infused into counselor education curricula and can be delivered by future licensed professional counselors, school counselors, or counseling interns.

Community agencies working with this client population should also consider providing counselors with professional development and training related to SFBT. It is important to mention that when two of us were in graduate programs, we did not receive formal SFBT instruction. This might be due to greater emphasis on humanistic and cognitive behavioral therapies in counseling curricula or among some counselor education faculty. As a result, counselor educators must make a cogent effort to promote and discuss postmodern theories such as SFBT. This is important because SFBT can be effective at improving internalizing disorders among clients (Schmit et al., 2016) and Latine populations (Gonzalez & Franklin, 2016).

Another implication for counselor educators is to consider teaching CITs how to use SCRDs to monitor and assess treatment effectiveness. All counseling interns who work in a community counseling clinic need to demonstrate the effectiveness of their services with clients. Therefore, CITs can learn how to use SCRDs or a single-group pretest/posttest with clinical significance (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2021; Lenz, 2020b) to determine the impact of counseling on client outcomes. Finally, community counseling clinics can consider using the DHS and OQ-45.2 to measure indicators of subjective well-being and clinical symptoms. CITs can use these instruments, which have evidence of reliability and validity with culturally diverse populations, to document the impact of their counseling services on clients’ hope and clinical symptoms.

Implications for Practitioners

There also are implications for practitioners. First, counselors can use SFBT principles and techniques to work with Latine clients. By using a positive and future-oriented framework, counselors can build a positive therapeutic relationship and help Latine clients construct a positive future. Counselors can use SFBT to help Latine clients identify how familismo is a source of strength (Oliver et al., 2011) and draw on their inner resiliency (Vela et al., 2015) to create their preferred future outcome. Practitioners can use SFBT techniques, including looking for previous solutions, exceptions, the miracle question, scaling questions, compliments, and future-oriented questions. SFBT principles and techniques can be used to facilitate hope by helping Latine clients view mental health challenges as opportunities to cultivate strengths and explore solutions (Bannik, 2008; Joubert & Guse, 2021).

Practitioners also can use SCRDs to evaluate the impact of their work with clients. Although most practitioners collect pre- and post-counseling intervention data, they typically use a single data point at pre-counseling and a single data point at post-counseling. Using an SCRD in which a baseline phase and weekly treatment points are collected can help analyze trends over time and identify clinical significance. Lenz (2015) described how practitioners can use SCRDs to make inferences—self as control, flexibility and responsiveness, small sample size, ease of data analysis, and type of data yielded from analyses. In other words, counseling practitioners can analyze data over time with a client and use the data collection and analysis methods in this study to evaluate the impact of their counseling services on client outcomes.

Implications and Limitations

There are several implications for future research. First, researchers can evaluate the impact of SFBT on other indicators related to subjective well-being and clinical symptoms among culturally diverse populations, including subjective happiness, resilience, grit, meaning in life, anxiety, and depression (Karaman et al., 2019). More research needs to explore how SFBT might enhance indicators of subjective well-being and decrease clinical symptoms as well as the intersection between recovery and psychopathology. Although researchers have explored the impact of SFBT on internalizing symptoms (Schmit et al., 2016), more research needs to examine the impact on subjective well-being, particularly among Latine populations and Latine adolescents at a community counseling clinic.

Researchers also should consider using qualitative methods to discover which SFBT techniques are most effective. In-depth interviews and focus groups with SFBT participants would provide insight and perspectives with the miracle question, scaling questions, and other SFBT techniques. Counselors could also collect clients’ journal entries to capture the impact of specific techniques on psychopathology or subjective well-being.

Additionally, using between-group designs to compare SFBT interventions with other evidence-based approaches such as cognitive behavior therapy could provide fruitful investigations. It is also possible to explore the impact of SFBT coupled with another approach such as positive psychology or cognitive behavior therapy with Latine populations. Finally, researchers can continue to explore the impact of CITs who work with clients in a community counseling clinic. Counseling interns can use SCRDs or single-group pretest/posttest designs to measure the impact of their counseling services.

The current study was exploratory in nature. Although both participants demonstrated improvement in measures related to subjective well-being and psychopathology, generalization to a larger Latine population is not appropriate. Because of the exploratory nature of this study, we cannot generate causal inferences regarding the relationship between SFBT and Hope as well as clinical symptoms. Second, we did not include withdrawal measures following completion of the treatment phase (Ikonomopoulos et al., 2016, 2017). Although some researchers use AB and ABA SCRDs to measure counseling effectiveness (Callender et al., 2021), we did not use an ABA design that would have provided stronger internal validity to evaluate changes of SFBT (Lenz et al., 2012). Because Himmelberger completed the academic semester and graduated from the clinical mental health counseling program, collecting withdrawal measures was not possible. Therefore, an AB SCRD was a more feasible approach.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first exploratory studies to examine the impact of the effectiveness of SFBT with Latine clients at a community counseling training clinic. This exploratory SCRD serves as a foundation for future data collection and evaluation of CITs who work with culturally diverse clients at community counseling training clinics. Results support the potential of SFBT as an intervention for promoting positive change for Latine clients’ hope and clinical symptoms.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Amble, I., Gude, T., Stubdal, S., Oktedalen, T., Skjorten, A. M., Andersen, B. J., Solbakken, O. A., Brorson, H. H., Arnevik, E., Lambert, M. J., & Wampold, B. E. (2014). Psychometric properties of the Outcome Questionnaire-45.2: The Norwegian version in an international context. Psychotherapy Research, 24(4), 504–513. https://doi.10.1080/10503307.2013.849016

Ayón, C., Marsiglia, F. F., & Bermudez-Parsai, M. (2010). Latino family mental health: Exploring the role of discrimination and familismo. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(6), 742–756.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20392

Bannik, F. P. (2008). Posttraumatic success: Solution-focused brief therapy. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 8(3), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhn013

Bavelas, J., De Jong, P., Franklin, C., Froerer, A., Gingerich, W., Kim, J., Korman, H., Langer, S., Lee, M. Y., McCollum, E. E., Jordan, S. S., & Trepper, T. S. (2013). Solution focused therapy treatment manual for working with individuals. Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association, 1–42. https://bit.ly/solutionfocusedtherapy

Berg, I. K. (1994). Family-based services: A solution-focused approach. W. W. Norton.

Boswell, D. L., White, J. K., Sims, W. D., Harrist, R. S., & Romans, J. S. C. (2013). Reliability and validity of the Outcome Questionnaire–45.2. Psychological Reports, 112(3), 689–693.

https://doi.org/10.2466/02.08.PR0.112.3.689-693

Brogan, J., Contreras Bloomdahl, S., Rowlett, W. H., & Dunham, M. (2020). Using SFBC group techniques to increase Latino academic self-esteem. Journal of School Counseling, 18. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1251785.pdf

Buchholz Holland, C. E. (2013). The lifeline activity with a “solution-focused twist.” Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 24(4), 306–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/08975353.2013.849552

Callender, K. A., Trustey, C. E., Alton, L., & Hao, Y. (2021). Single case evaluation of a mindfulness-based mobile application with a substance abuse counselor. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 12(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2019.1686353

Calzada, E. J., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Yoshikawa, H. (2013). Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. Journal of Family Issues, 34(12), 1696–1724.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513×12460218

Cavazos, A. G. (2009). Reflections of a Latina student-teacher: Refusing low expectations for Latina/o students. American Secondary Education, 37(3), 70–79.

Cavazos, J., Jr., Johnson, M. B., Fielding, C., Cavazos, A. G., Castro, V., & Vela, L. (2010). A qualitative study of resilient Latina/o college students. Journal of Latinos and Education, 9(3), 172–188.

https://doi.org/10.1080/153484431003761166

Cheng, H.-L., Hitter, T. L., Adams, E. M., & Williams, C. (2016). Minority stress and depressive symptoms: Familism, ethnic identity, and gender as moderators. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(6), 841–870.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016660377

Cheng, H.-L., & Mallinckrodt, B. (2015). Racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol problems in a longitudinal study of Hispanic/Latino college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000052

Coco, G. L., Chiappelli, M., Bensi, L., Gullo, S., Prestano, C., & Lambert, M. J. (2008). The factorial structure of the Outcome Questionnaire-45: A study with an Italian sample. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 15(6), 418–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.601

de Shazer, S. (1991). Putting differences to work. W. W. Norton.

de Shazer, S., Dolan, Y., Korman, H., Trepper, T., McCollum, E., & Berg, I. K. (2007). More than miracles: The state of the art of solution-focused brief therapy. Hawthorne Press.

Dorais, S., Gutierrez, D., & Gressard, C. R. (2020). An evaluation of motivational interviewing based treatment in a university addiction counseling training clinic. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 11(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2019.1704175

Ekroll, V. B., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2017). Pathways towards different long-term outcomes after naturalistic psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(2), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2162

Feldman, D. B., & Dreher, D. E. (2012). Can hope be changed in 90 minutes? Testing the efficacy of a single-session goal-pursuit intervention for college students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 745–759.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9292-4

Galiana, L., Oliver, A., Sancho, P., & Tomás, J. M. (2015). Dimensionality and validation of the Dispositional Hope Scale in a Spanish sample. Social Indicators Research, 120, 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0582-1

Gonzalez Suitt, K., Franklin, C., & Kim, J. (2016). Solution-focused brief therapy with Latinos: A systematic review. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 25, 50–67.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2015.1131651

Ikonomopoulos, J., Garza, K., Weiss, R., & Morales, A. (2021). Examination of treatment progress among college students in a university counseling program. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 12(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2020.1850175

Ikonomopoulos, J., Lenz, A. S., Guardiola, R., & Aguilar, A. (2017). Evaluation of the Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 with a Mexican-American population. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory, & Research, 44(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2017.12033956

Ikonomopoulos, J., Smith, R. L., & Schmidt, C. (2015). Integrating narrative therapy within rehabilitative programming for incarcerated adolescents. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(4), 460–470.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12044

Ikonomopoulos, J., Vela, J. C., Smith, W. D., & Dell’Aquila, J. (2016). Examining the practicum experience to increase counseling students’ self-efficacy. The Professional Counselor, 6(2), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.15241/ji.6.2.161

Joubert, J., & Guse, T. (2021). A solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) intervention model to facilitate hope and subjective well-being among trauma survivors. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 51, 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-021-09511-w

Kadera, S. W., Lambert, M. J., & Andrews, A. A. (1996). How much therapy is really enough?: A session-by-session analysis of the psychotherapy dose-effect relationship. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 5(2), 132–151.

Karaman, M. A., Vela, J. C., Aguilar, A. A., Saldana, K., & Montenegro, M. C. (2019). Psychometric properties of U.S.-Spanish versions of the grit and resilience scales with a Latinx population. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 41, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9350-2

Kendall, P. C., Marrs-Garcia, A., Nath, S. R., & Sheldrick, R. C. (1999). Normative comparisons for the evaluation of clinical significance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(3), 285–299.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.67.3.285

Kim, J. S. (2008). Examining the effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy: A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507307807

Lambert, M. J., Burlingame, G. M., Umphress, V., Hansen, N. B., Vermeersch, D. A., Clouse, G. C., & Yanchar, S. C. (1996). The reliability and validity of the Outcome Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 3(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10/bmwzbf

Lenz, A. S. (2013). Calculating effect size in single-case research: A comparison of nonoverlap methods. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 46(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175612456401

Lenz, A. S. (2015). Using single-case research designs to demonstrate evidence for counseling practices. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(4), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12036

Lenz, A. S. (2020a). The future of Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 11(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2020.1712977

Lenz, A. S. (2020b). Estimating and reporting clinical significance in counseling research: Inferences based on percent improvement. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 53(4), 289–296.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2020.1784758

Lenz, A. S. (2021). Clinical significance in counseling outcome research and program evaluation. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 12(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2021.1877097

Lenz, A. S., Speciale, M., & Aguilar, J. V. (2012). Relational-cultural therapy intervention with incarcerated adolescents: A single-case effectiveness design. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 3(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137811435233

Lerma, E., Zamarripa, M. X., Oliver, M., & Vela, J. C. (2015). Making our way through: Voices of Hispanic counselor educators. Counselor Education and Supervision, 54(3), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12011

Liu, V. Y., La Guardia, A., & Sullivan, J. M. (2020). A single-case research evaluation of collaborative therapy treatment among adults. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 11(1), 45–58.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2018.15311238

Lundervold, D. A., & Belwood, M. F. (2000). The best kept secret in counseling: Single-case (N = 1) experimental designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78(1), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb02565.x

Ma, H.-H. (2006). An alternative method for quantitative synthesis of single-subject researches: Percentage of data points exceeding the median. Behavior Modification, 30(5), 598–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445504272974

Mendoza, H., Masuda, A., & Swartout, K. M. (2015). Mental health stigma and self-concealment as predictors of help-seeking attitudes among Latina/o college students in the United States. International Journal for Advancement of Counselling, 37(3), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-015-9237-4

Merikangas, K. R., He, J.-P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., Benjet, C., Georgiades, K., & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Study Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of Academy Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

Neipp, M.-C., Beyebach, M., Sanchez-Prada, A., & Álvarez, M. D. C. D. (2021). Solution-focused versus problem-focused questions: Differential effects of miracles, exceptions and scales. Journal of Family Therapy, 43(4), 728–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12345

Nel, P., & Boshoff, A. (2014). Factorial invariance of the Adult State Hope Scale. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(1), 1–8.

Novella, J. K., Ng, K.-M., & Samuolis, J. (2020). A comparison of online and in-person counseling outcomes using solution-focused brief therapy for college students with anxiety. Journal of American College Health, 70(4), 1161–1168. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1786101

Oliver, M., Flamez, B., & McNichols, C. (2011). Postmodern applications with Latino/a cultures. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 38(3), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2011.12033875

Ponciano, C., Semma, B., Ali, S. F., Console, K., & Castillo, L. G. (2020). Institutional context of perceived discrimination, acculturative stress, and depressive symptoms among Latina college students. Journal of Latinos and Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2020.1809418

Priest, J. B., & Denton, W. (2012). Anxiety disorders and Latinos: The role of family cohesion and family discord. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 34(4), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986312459258

Proudlock, S., & Wellman, N. (2011). Solution focused groups: The results look promising. Counselling Psychology Review, 26(3), 45–54.

Ramos, G., Delgadillo, D., Fossum, J., Montoya, A. K., Thamrin, H., Rapp, A., Escovar, E., & Chavira, D. A. (2021). Discrimination and internalizing symptoms in rural Latinx adolescents: An ecological model of etiology. Children and Youth Services Review, 130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106250

Sáenz, V. B., Lu, C., Bukoski, B. E., & Rodriguez, S. (2013). Latino males in Texas community colleges: A phenomenological study of masculinity constructs and their effect on college experiences. Journal of African American Males in Education, 4(2), 82–102.

Sanchez, M. E. (2019). Perceptions of campus climate and experiences of racial microaggressions for Latinos at Hispanic-Serving Institutions. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 18(3), 240–253.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192717739

Schmit, E. L., Schmit, M. K., & Lenz, A. S. (2016). Meta-analysis of solution-focused brief therapy for treating symptoms of internalizing disorders. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 7(1), 21–39.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137815623836

Schuermann, H., Borsuk, C., Wong, C., & Somody, C. (2018). Evaluating effectiveness in a Hispanic-serving counselor training clinic. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 9(2), 67–79.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2018.1442680

Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (1998). Summarizing single-subject research: Issues and applications. Behavior Modification, 22(3), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455980223001

Scruggs, T. E., Mastropieri, M. A, & Casto, G. (1987). The quantitative synthesis of single-subject research: Methodology and validation. Remedial and Special Education, 8(2), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258700800206

Sharpley, C. F. (2007). So why aren’t counselors reporting n = 1 research designs? Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(3), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00483.x

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, J., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

Snyder, C. R., Michael, S. T., & Cheavens, J. S. (1999). Hope as a psychotherapeutic foundation of common factors, placebos, and expectancies. In M. A. Hubble, B. L. Duncan, & S. D. Miller (Eds.), The heart and soul of change: What works in therapy (pp. 179–200). American Psychological Association.

Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Adams, V. H., III, & Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 820–826.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.820

Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., Ybasco, F. C., Borders, T. F., Babyak, M. A., & Higgins, R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personal Social Psychology, 70(2), 321–325.

https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321

Soares, M. C., Mondon, T. C., da Silva, G. D. G., Barbosa, L. P., Molina, M. L., Jansen, K., Souza, L. D. M., & Silva, R. A. (2018). Comparison of clinical significance of cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy for major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(9), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000872

Suldo, S. M., & Shaffer, E. J. (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2008.12087908

Tambling, R. B. (2012). Solution-oriented therapy for survivors of sexual assault and their partners. Contemporary Family Therapy, 34, 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-012-9200-z

Trepper, T. S., McCollum, E. E., De Jong, P., Korman, H., Gingerich, W., & Franklin, C. (2010). Solution focused therapy treatment manual for working with individuals. Research Committee of the Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association. https://www.andrews.edu/sed/gpc/faculty-research/coffen-research/trepper_2010_solution.pdf

Umphress, V. J., Lambert, M. J., Smart, D. W., Barlow, S. H., & Glenn, C. (1997). Concurrent and construct validity of the Outcome Questionnaire. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 15(1), 40–55.

https://doi.org/10.1177/073428299701500104

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Quick facts: United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RH1725221

Vannest, K. J., & Ninci, J. (2015). Evaluating intervention effects in single-case research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(4), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12038

Vela, J. C., Ikonomopoulos, J., Dell’Aquila, J., & Vela, P. (2016). Evaluating the impact of creative journal arts therapy for survivors of intimate partner violence. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 7(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137816664781

Vela, J. C., Ikonomopoulos, J., Hinojosa, K., Gonzalez, S. L., Duque, O., & Calvillo, M. (2016). The impact of individual, interpersonal, and institutional factors on Latina/o college students’ life satisfaction. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 15(3), 260–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192715592925

Vela, J. C., Ikonomopoulos, J., Lenz, A. S., Hinojosa, Y., & Saldana, K. (2017). Evaluation of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire and Dispositional Hope Scale with Latina/o students. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56(3), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12051

Vela, J. C., Lerma, E., Lenz, A. S., Hinojosa, K., Hernandez-Duque, O., & Gonzalez, S. L. (2014). Positive psychology and familial factors as predictors of Latina/o students’ hope and college performance. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 36(4), 452–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986314550790

Vela, J. C., Lu, M.-T. P., Lenz, A. S., & Hinojosa, K. (2015). Positive psychology and familial factors as predictors of Latina/o students’ psychological grit. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 37(3), 287–303.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986315588917

Vela, J. C., Lu, M.-T. P., Lenz, A. S., Savage, M. C., & Guardiola, R. (2016). Positive psychology and Mexican American college students’ subjective well-being and depression. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 38(3), 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986316651618

Vela, J. C., Lu, M.-T. P., Veliz, L., Johnson, M. B., & Castro, V. (2014). Future school counselors’ perceptions of challenges that Latina/o students face: An exploratory study. In Ideas and Research You Can Use: VISTAS 2014, Article 39, 1–12. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/article_39.pdf?sfvrsn=10

Vela-Gude, L., Cavazos, J., Jr., Johnson, M. B., Fielding, C., Cavazos, A. G., Campos, L., & Rodriguez, I. (2009). “My counselors were never there”: Perceptions from Latina college students. Professional School Counseling, 12(4), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0901200407

Krystle Himmelberger, MS, LPC, is a doctoral candidate at St. Mary’s University. James Ikonomopoulos, PhD, LPC-S, is an assistant professor at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi. Javier Cavazos Vela, PhD, LPC, is a professor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Correspondence may be addressed to James Ikonomopoulos, 6300 Ocean Drive, Unit 5834, Corpus Christi, TX 78412,

james.ikonomopoulos1@tamucc.edu.