Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Nancy Chae, Adrienne Backer, Patrick R. Mullen

All counseling graduate students participate in fieldwork experiences and engage in supervision to promote their professional development. School counseling trainees complete these experiences in the unique context of elementary and secondary school settings. As such, school counselors-in-training (SCITs) may seek to approach supervision with specific strategies tailored for the roles, responsibilities, and dispositions required of competent future school counselors. This article suggests practical strategies for SCITs, including engaging in reflection; navigating feelings of vulnerability in supervision; developing appropriate professional dispositions for school counseling practice; and practicing self-advocacy, broaching, and self-care. Counselor educators can share these strategies to help students identify their needs for their field experiences and prepare for their professional careers as school counselors.

Keywords: supervision, professional development, school counseling, school counselors-in-training, strategies

School counselors-in-training (SCITs) are trainees enrolled in graduate-level counselor education programs and receive supervision as an integral component of their training (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). Although the supervision relationship is often characterized as hierarchical, trainees must actively participate in the supervision process to develop competency as counseling professionals (Stark, 2017). Despite this, trainees in counseling programs generally receive little guidance on understanding their roles in supervision or how to make the most of their supervision experience to contribute to their learning (Pearson, 2004; Stark, 2017). Although Pearson (2004) offered suggestions for mental health counseling students to optimize their supervision experiences, there is limited literature about how school counseling students can maximize their supervision experiences. The intention of this article is to share strategies for SCITs to take the initiative to approach supervisors with questions and ideas about their overall supervision experience, though these suggestions are not limited to SCITs and may also be useful for trainees across other counseling disciplines.

School counseling site supervision is distinguishable from supervision in other helping professions in that the roles and responsibilities of professional school counselors extend beyond the individual and group counseling services that their community counseling partners provide (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2019a, 2021; Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). For example, comprehensive school counseling programming encompasses direct counseling services with students and families in addition to broader systemic consultation, advocacy, and support for school communities (ASCA, 2019a). School counselors encounter unique challenges in schools regarding student and staff mental health, issues related to equity and access, and navigating the political landscapes of school systems (Bemak & Chung, 2008). Even with an understanding of these distinct themes in school counseling, there is a lack of significance placed on supervision in school counseling within research and in practice to adequately respond to contemporary school counseling issues (Bledsoe et al., 2019). Examining how SCITs can approach supervision and their roles as trainees can ensure their own learning and developmental needs are met, along with the needs of their school communities.

Contexts of School Counseling Supervision

Supervision for SCITs is provided by experienced professional school counselors and characterized by an intentional balance of hierarchy, evaluation, and support during their practicum and internship fieldwork experiences (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Borders & Brown, 2005). School counselor supervision serves three primary purposes: (a) promoting competency in effective and ethical school counseling practice; (b) facilitating SCITs’ personal and professional development; and (c) upholding accountability of services and programs for the greater profession and the schools, students, and families receiving services (ASCA, 2021; L. J. Bradley et al., 2010). School counseling site supervisors utilize their training and experiences to guide SCITs through their induction to the profession and development of initial skills and dispositions.

ASCA (2021) compels school counseling supervisors to address the complexities specific to educational settings as they support the professional development of SCITs, which sets school counseling supervision apart from supervision in other clinical counseling disciplines. School counselors facilitate instruction and classroom management, provide appraisal and advisement, and support the developmental and social–emotional needs of students through data-informed school counseling programs (ASCA, 2019a). Within school and community settings, they also navigate systems with an advocacy and social justice orientation and attend to cultural competence and anti-racist work. Although there are school counseling–specific supervision models that address some of the complexities inherent in the work of school counselors (e.g., Lambie & Sias, 2009; Luke & Bernard, 2006; S. Murphy & Kaffenberger, 2007; Wood & Rayle, 2006), there is currently a gap in the school counseling literature about effectively addressing the unique supervision needs of SCITs. Therefore, school counselor practitioners and counselor educators may refer to professional standards for supervision to inform how they supervise and support the developmental needs of SCITs, which may also help SCITs to understand what they might expect to encounter in graduate-level supervision.

Professional Standards for School Counseling Supervision

School counseling professional standards underscore the need for school counselor supervisors to seek supervision and training (ASCA, 2019b; Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2015; Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). Professional associations and accrediting organizations (e.g., ASCA, CACREP) promote adherence to and integration of school counselor standards and competencies related to leadership, advocacy, collaboration, systemic change, and ethical practice (ASCA, 2022; CACREP, 2015; Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). As such, school counseling supervision facilitates ethical and professional skill development through school counselor standards and competencies, such as the ASCA School Counselor Professional Standards & Competencies (ASCA, 2019c) and the ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors (ASCA, 2022).

School counseling supervisors can support SCITs’ professional growth and development by aligning supervision activities with specific standards and competencies (Quintana & Gooden-Alexis, 2020). For example, a supervisor seeking to model the school counselor mindset and behavior standards focused on collaborative partnerships (i.e., M 5, B-SS 6; ASCA, 2019c) might provide opportunities for SCITs to develop relationships with stakeholders (e.g., families, administrators, community) while supporting student achievement. Similarly, an example of aligning supervision activities with ethical standards might involve guiding an SCIT through the process of utilizing an ethical decision-making model to resolve a potential dilemma (see Section F; ASCA, 2022).

Supervision in School Counseling

Supervision in school counseling ensures that new professionals enter the field prepared to understand and support the needs of students by effectively applying ethical standards and best practices of the profession. As such, gatekeeping is a crucial component of supervision. As gatekeepers, counselor educators or supervisors exercise their professional authority to take action that prevents a trainee who does not enact the required professional dispositions and ethical practices from entering the profession of counseling (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). When a trainee is identified as unable to achieve counseling competencies or likely to harm others, ethical practice guides counselor educators to provide developmental or remedial services to work toward improvements before dismissal from a counseling program (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Foster & McAdams, 2009).

Although supervised fieldwork experiences during graduate education and training are needed for accreditation (CACREP, 2015) and state certification, professional school counselors employed in the field may not be required to participate in any form of post-master’s clinical supervision for initial school counseling certification or renewal of their certification, unlike professional clinical mental health counselors, who require post-master’s supervision to attain licensure (Dollarhide & Saginak, 2017; Mecadon-Mann & Tuttle, 2023). Administrative supervision provided by a school administrator is more common for school counselors than clinical supervision, which promotes the competence of counselors by focusing on the development and refinement of counseling skills (Herlihy et al., 2002). In other words, though school counselors routinely encounter complex situations that involve supporting students with acute needs and responding to crises, they likely do not receive the clinical supervision needed to enhance their judgment, skills, and ethical decision-making (Bledsoe et al., 2019; Brott et al., 2021; Herlihy et al., 2002; McKibben et al., 2022; Sutton & Page, 1994). Given the reality that school counselors may not access or receive opportunities for postgraduate clinical supervision, it is important that SCITs experience robust supervision during their graduate training programs with the support of qualified site and university supervisors. This sets the stage for SCITs to effectively engage with the challenges of their future school counseling careers.

Expectations of Site and University Supervisors

For SCITs who are new to the experience of supervision in their fieldwork, it is helpful to understand what they may expect from their respective site and university supervisors. Borders et al. (2014) recommended that supervisors initiate supervision, set goals with trainees, provide feedback, facilitate the supervisory relationship, and attend to diversity, as well as engage in advocacy, ethical consideration, documentation, and evaluation. Supervisors select supervision interventions that attend to the developmental needs of trainees, and they also serve as gatekeepers for the profession (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Borders et al., 2014). Furthermore, supervisors facilitate an effective relationship with their trainees, characterized by empowerment, encouragement, and safety (Dressel et al., 2007; Ladany et al., 2013; M. J. Murphy & Wright, 2005). Supervisors provide a balance of support and challenge in their feedback and interactions with trainees (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019) and attend to multicultural issues by broaching with their trainees about their intersecting identities and experiences of power, privilege, and marginalization (Dressel et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2019; M. J. Murphy & Wright, 2005). Supervisors also validate trainees’ experiences by acknowledging any emergent issues of vicarious trauma and encouraging self-care (K. Jordan, 2018).

Supervisors and trainees have mutual responsibilities to facilitate an effective supervision experience. Although supervisors may hold a more significant stake of power in the relationship, trainees’ willingness to take an active role also matters. School counseling trainees are not passive bystanders in the learning process; instead, they can be thoughtful learners yearning to take full advantage of the growth from their clinical experiences. To help illuminate the opportunities and expectations SCITs can seek during supervision, the subsequent strategies from school counseling supervision research serve as suggested approaches for SCITs to make the most of this fundamental and practical learning experience.

Strategies for School Counseling Trainees

School counseling trainees can take an active role to ensure that their supervision experiences are relevant to their personal and professional development. The following approaches do not constitute an all-encompassing list but provide a foundation and guidelines rooted in existing research to get the most out of the supervision experience, including engaging in reflection and vulnerability, practicing self-advocacy, broaching, and maintaining personal wellness.

Reflection in Supervision

Reflection is key to school counselor development, especially in supervision. Researchers have reported that continuous reflection helps novice counselors move toward higher levels of cognitive complexity and expertise (Borders & Brown, 2005; Skovholt & Rønnestad, 1992). A reflective trainee demonstrates openness to understanding; avoids being defensive; and engages in profound thought processes that lead to changes in their perceptions, practice, and complexity (Neufeldt et al., 1996). Through reflection, trainees consider troubling, confusing, or uncertain experiences or thoughts and then reframe them to problem-solve and guide future actions (Ward & House, 1998; Young et al., 2011). Further, by developing relationships with supervisors, trainees become open to receiving and integrating feedback to support their development (Borders & Brown, 2005). Reflection becomes an ongoing process and practice throughout trainees’ academic and field experiences and postgraduation.

Trainees can engage in self-reflective practices in various ways over the course of their graduate training. First, trainees can use a journal to record thoughts, feelings, and events throughout their school counseling field experiences. Research has shown that written or video journaling can help trainees to reflect on the highs and lows of counseling training and foster self-awareness (Parikh et al., 2012; Storlie et al., 2018; Woodbridge & O’Beirne, 2017). For example, trainees can connect their practical experiences with knowledge from academic learning to note discrepancies and consistencies (e.g., learning about the ASCA National Model and the extent to which a school chooses to implement the model; navigating the bureaucracy of school systems that often dictate roles and responsibilities of school counselors). Trainees can also challenge their thoughts by exploring difficult experiences using reflective journaling. They can journal about the different perspectives of those involved in the situation (e.g., students, parents/guardians, teachers, administrators), process ethical dilemmas, and gauge and manage any emotional experiences attached to grappling with challenges. Trainees desiring structured prompts can consider writing about specific developmental, emotional, and interpersonal experiences to process events related to counselor and client interactions (Storlie et al., 2018).

Second, trainees can consult with their supervisors to seek guidance and constructive feedback about challenging experiences (Borders & Brown, 2005). Hamlet (2022) recommended using the S.K.A.T.E.S. form to reflect on issues related to trainees’ Skills, Knowledge, Attitudes, Thoughts, Ethics, and Supervision needs. Using S.K.A.T.E.S., for example, a school counseling intern may reflect on how they incorporated motivational interviewing counseling skills to support a student struggling with their declining grades (North, 2017). They might seek supervision about a challenging crisis response at the school and process how they might have responded differently. Even after supervision sessions, trainees should engage in continued self-reflection and apply new learning to their clinical practice.

Third, trainees can utilize the Johari window as a tool to reflect upon the knowledge, awareness, and skills required for school counseling practice (Halpern, 2009). Trainees work with supervisors to consider questions or experiences to identify: (a) open areas (i.e., things known to everyone, such as critically discussing school- and district-wide policies that contribute to inequitable access to college preparatory courses); (b) hidden areas (i.e., things only known to the trainee to be shared in supervision, such as the trainee’s hesitations about leading a group counseling session with middle school students independently for the first time); (c) blind spots (i.e., things that the supervisor is aware of that the trainee may not be, such as personal biases, prejudices, stereotypes, and discriminatory attitudes that may affect the trainee’s conceptualizations and interactions with students and families); and (d) undiscovered potential (i.e., things that the supervisor and trainee can experience and learn together, such as engaging in professional learning together to align school counseling programming with a school-wide movement toward implementing restorative justice practices). This strategy also compels trainees to align their supervision goals with ethical codes (see A.4.b., F.8.c., and F.8.d in the ACA Code of Ethics) and standards for professional practice (ACA, 2014). Trainees can feel empowered to utilize the Johari window with supervisors and peers to guide conversations, generate questions, and develop insights to inform school counseling practice and explore ethical dilemmas.

Vulnerability in Supervision

Vulnerability is an essential yet challenging experience within the hierarchical nature of supervision. Being vulnerable involves feelings of uncertainty, reluctance, and exposure; hence, trainees require a sense of psychological safety and support to explore their needs and areas of weakness (Bradley et al., 2019; Giordano et al., 2018; J. V. Jordan, 2003). Although site supervisors hold the primary responsibility for facilitating supervision relationships characterized by safety and support (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019), trainees can feel empowered to advocate for supervision environments that encourage authenticity and vulnerability, which are conducive to growth and development.

First, trainees can discuss with their supervisors and peers to define feelings of vulnerability and create group norms to promote supported vulnerability (Bradley et al., 2019). With a shared understanding, trainees, supervisors, and peers create an environment for continued growth and risk-taking. For example, during the first group supervision meeting, trainees can suggest norms that will individually and collectively sustain a safe classroom community for sharing and learning. A lack of clear norms about how to communicate feedback may result in experiences of shame and affect trainees’ confidence (J. V. Jordan, 2003; Ratts & Greenleaf, 2018). To mitigate this, trainees, supervisors, and peers can collaboratively discuss appropriate and preferred ways of giving and receiving feedback that is supportive, productive, and meaningful (Ladany et al., 2013). For example, trainees may prefer specific comments rather than general praise: “When the client expressed their frustration, you did well to remain calm and reflect content and feelings in that moment,” instead of “You did a great job.” This exchange among trainees, supervisors, and peers offers a constructive and engaging experience in which individuals can appropriately support and challenge one another.

Second, reviewing recordings offers a learning opportunity for trainees to reflect upon and critique their own skills and dispositions (Borders & Brown, 2005). When presenting recorded case presentations, trainees can practice vulnerability by selecting and presenting recordings that highlight challenging areas that may require constructive feedback (i.e., show their worst rather than their best). Trainees can identify portions of recordings that exemplify where they need the most help, such as a challenging experience during an individual counseling session with a student. Further, when presenting their recordings, trainees can also ask for suggestions to improve consultation work with caregivers when discussing college and career planning issues or innovative instructional strategies for teaching a classroom lesson in response to challenging situations. Vulnerability also occurs when trainees seek support from supervisors and peers about blind spots and areas of strength and growth regarding skill development and self-awareness issues in the recorded session or role-play. For instance, a trainee may express concern about the increasing academic counseling referrals of ninth-grade students who are struggling with the transition to high school and ask for guidance about how to more effectively respond systemically and individually.

Self-Advocacy in Supervision

Self-advocacy is another empowering practice for trainees to identify their needs and seek support. Researchers have defined self-advocacy as understanding one’s rights and responsibilities, communicating needs, and negotiating for support, which helps trainees proactively approach supervision (Astramovich & Harris, 2007; Pocock et al., 2002). Although supervision is characterized as hierarchical, it is also a relationship based on mutual participation, with inherent expectations for trainees (Stark, 2017). Within the evaluative nature of a supervision relationship, trainees may reasonably feel intimidated about practicing self-advocacy. However, trainees can feel empowered to self-advocate when building rapport with supervisors in an environment characterized by safety and support.

To prepare to self-advocate, trainees should continue engaging in self-reflection on their gaps in knowledge, awareness, and skills related to school counseling practice and then consider the types of resources and supports needed from their supervisor to bridge such gaps. In alignment with their learning goals, trainees can self-advocate by taking the initiative to request support for what they would like to achieve during the supervision experience (Storlie et al., 2019). For example, trainees may inquire about logistical concerns, such as seeking guidance about appropriate and creative ways to ensure that they earn sufficient direct and indirect hours, or evaluative concerns, like asking how to improve in specific school counseling skill areas after mid- and end-of-semester evaluations. Trainees can also seek support with conceptualization (e.g., applying a theoretical orientation when understanding the potential contributors to a student’s feeling of anxiety), skill development (e.g., experience with advocating for students receiving special education services in an Individualized Educational Plan [IEP] meeting), and countertransference issues (e.g., emotional reactions that may arise when supporting a grieving student coping with a loss; Pearson, 2004). Trainees should prepare specific questions that communicate their needs and explicitly request resources, opportunities, or next steps for continued improvement and development.

Trainees may also self-advocate through positive communication, which is a critical skill for helping professionals and in maintaining relationships (Biganeh & Young, 2021). Positive communication may involve actively listening to their supervisor’s insights, presenting statements that paraphrase their supervisor’s key points, and asking open-ended questions to elicit mutual exploration of topics of interest. For instance, after observing a crisis response to a student expressing suicidal ideation, the trainee can debrief about their experiences with their supervisor by summarizing key observations and protocol followed, while also asking what steps could be added or reconsidered if the trainee were leading the crisis response. Additionally, practicing communication skills in the context of supervision may enhance trainees’ competence and confidence when interacting with students and stakeholders, including caregivers, teachers, and administrators (Heaven et al., 2006). For example, trainees can request to observe and later role-play how they might facilitate a consultation meeting with a student and their parent to discuss the importance of consistent attendance and academic development.

Trainees can get the most out of their supervision experience by self-advocating and taking initiative to describe their unique learning styles and needs (Storlie et al., 2019). This provides an opportunity for trainees to proactively convey their goals and concerns about students and stakeholders at their sites (Baltrinic et al., 2021; Cook & Sackett, 2018). For example, if the trainee has become increasingly comfortable with co-leading a group counseling session, the trainee can communicate a desire to design and independently lead a group counseling session and then seek feedback about the curriculum plans or recordings of the session for continued improvement in group facilitation skills. Ultimately, engaging in self-advocacy skills during fieldwork helps trainees prepare for their careers as school counselors, in which self-advocacy is necessary when seeking professional development, resources for school counseling program development, and navigating school systems and politics to support their students and school counseling programs (Oehrtman & Dollarhide, 2021).

Broaching

Broaching is an ongoing behavior in which counselors invite conversations to explore race, ethnicity, and culture with clients, which can strengthen the counseling relationship and enhance cultural responsiveness and therapeutic benefits (Day-Vines et al., 2007, 2013). Likewise, in supervisory relationships, broaching helps supervisors and trainees to understand how cultural factors affect the supervisory relationship (Jones et al., 2019). Without broaching, both supervisors and trainees may miss meaningful contexts and realities, potentially rupturing the supervisory relationship (Jones et al., 2019). Broaching is also a key demonstration of commitment to culturally informed clinical supervision that promotes cultural humility and anti-racist counseling and supervision practice (Cartwright et al., 2021).

Although supervisors are charged with the responsibility of broaching based on the hierarchical nature of the supervisory relationship and its inherent power dynamics, they may not consistently incorporate broaching as part of their regular supervision behaviors (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; King & Jones, 2019). Trainees who feel empowered to discuss issues of identity and power in supervision are more likely to initiate broaching conversations with their supervisors (King & Jones, 2019). As such, trainees should feel encouraged to engage in discussions with their supervisors to openly address cultural identities that may impact the supervisory relationship and their work with students and stakeholders in schools. King and Jones (2019) suggested that trainees can broach topics that they feel comfortable discussing within the context of their supervision relationship. It is necessary to note that the process and outcome of broaching in supervision are not only contingent upon the diverse sociocultural and sociopolitical contexts of individuals, but also on where the trainee and supervisor lie within the continuum of broaching styles and their own racial identity development as well as the power and hierarchy dynamics of the supervisory relationship (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Day-Vines et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2019). Just as for any novice counselor and individuals in the early stages of the broaching styles continuum, there may be hesitation, anxiousness, misunderstanding, or intimidation about engaging in broaching skills, especially considering the power dynamic of supervision. Trainees can self-assess their broaching style by using the Broaching Attitudes and Behavior Survey (Day-Vines et al., 2007, 2013), which might provide them with insight about their own level of comfort with broaching in supervision.

Trainees can seek continuing education and support from supervisors and peers about developing and strengthening their understanding of cultural diversity, race, oppression, and privilege related to school counseling. If a trainee feels nervous about broaching with their supervisor, the trainee can express their desire to practice broaching and seek feedback from their supervisor after broaching has taken place (e.g., “I would like to try broaching about a student’s cultural identities, and I was wondering if you could share your thoughts with me.”). Trainees can also directly express curiosities, observations, or questions about how any cultural differences and similarities between the supervisor and trainee may impact and inform the supervisory relationship. For example, a trainee and supervisor can discuss prior supervisory relationships, such as in academic or employment experiences, and identify the shared or different intersectional cultural identities to understand how this new supervisory relationship can be a meaningful relationship and safe space for learning. This exercise demonstrates cultural humility in which trainees engage in respectful curiosity, a stance of openness, and cultural awareness that enhances the supervisory working alliance (Watkins et al., 2019).

Broaching can also help school counseling trainees move beyond the nice counselor syndrome—a phenomenon in which stakeholders may often view school counselors as harmonious and unengaged in conflict, which supersedes their position as social justice advocates and instead perpetuates the status quo and reinforces inequities (Bemak & Chung, 2008). Because broaching invites discussion about multicultural and social justice issues, trainees can initiate conversations about personal obstacles (e.g., apathy, anxiety, guilt, discomfort) and professional obstacles (e.g., professional paralysis, resistance, job security) during supervision (Bemak & Chung, 2008). For example, a trainee can seek guidance about how to present a proposal to administrators about an affinity group for LGBTQ+ students and allies in the school. They can discuss potential personal and professional obstacles, how to overcome such obstacles to promote the group, and how to advocate for inclusion of LGBTQ+ students. It is important for trainees to engage in advocacy during their fieldwork experiences because social justice is inherent to school counselor identity and comprehensive school counseling programs (Glosoff & Durham, 2010).

Personal Well-Being

Self-care and personal wellness are necessary not only for counseling practice but also for supervision experiences; these contribute to personal and professional development and ethical practice, promote positive outcomes with students/clients, and mitigate issues of burnout and turnover (Blount et al., 2016; Branco & Patton-Scott, 2020; Mullen et al., 2020). For trainees, it is typical yet challenging to balance an academic workload; the demands of fieldwork; and other personal, social, and emotional experiences. Trainees can utilize supervision to maintain accountability for self-assessing their wellness practices that support their continued effective and ethical counseling practice. Marley (2011) found that self-help strategies can reduce emotional distress and offer coping skills to manage difficulties, which can help trainees maintain their self-care and develop skills for continued wellness.

Blount et al. (2016) suggested developing a wellness identity in supervision. Trainees can develop a wellness identity by acknowledging the wellness practices they already engage in and continuing practices that help to maintain self-care. Moreover, Mullen et al. (2020) found that engaging in problem-solving pondering (e.g., planning or developing a strategy to complete a task or address a problem within fieldwork), as opposed to negative work-related rumination, supported well-being, higher job satisfaction, and work engagement for school counselors. For example, rather than ruminating about a disagreement with a teacher regarding recommending a student for the gifted program, the trainee can consider ways to turn future conversations into partnership opportunities with the teacher—while also consulting with the supervisor, administrator, and parent about considering additional data points to advocate for the student’s enrollment in the gifted program.

Another way for trainees to support their well-being is to acknowledge their strengths (Wiley et al., 2021) related to their clinical knowledge, awareness, and skills in live and recorded sessions with students. This can be challenging yet empowering for trainees who are quick to self-criticize. For instance, before jumping to areas for improvement, trainees are encouraged to first ask, “What did I do well here?” and also request recommendations for additional wellness strategies to strengthen their school counseling practice. Additional resources, such as readings or role-plays, may help trainees

re-center themselves after difficult or challenging scenarios. For example, after making their first report to child protective services about a suspected physical abuse case, the trainee can process with their supervisor and discuss potential self-care strategies and resources to manage the difficult emotions arising from the challenging experience.

Moreover, researchers suggested utilizing self-compassion as a means of self-care for counseling graduate students (Nelson et al., 2018). Trainees can intentionally practice being kind to oneself; normalizing and humanizing the experience of challenges; and being aware of one’s own feelings, thoughts, and reactions, which can enhance their well-being and reduce potential fatigue and burnout (Nelson et al., 2018; Pearson, 2004). For example, after hearing difficult feedback from their supervisor about improving a lesson plan, a trainee can try reframing weaknesses as areas for continued growth. Or, when reviewing a mid- or end-of-semester evaluation with their supervisor, a trainee can practice being present and open to feedback while also monitoring and taking the initiative to share feelings, insights, and questions. After a supervision session or evaluative experience, a trainee can also engage in journaling or compassionate letter writing (Nelson et al., 2018) to be mindfully aware of their emotions and normalize the challenging growth experiences of a developing counselor.

Overall, trainees deserve meaningful, supportive, and responsive supervision, yet they commonly (mis)perceive themselves as in positions of less power in supervision and their fieldwork sites. Trainees should feel empowered to consult with others at their sites and universities to address issues of concern and seek clarification from supervisors about the expectations of supervision; this supports an effective, collaborative supervision experience. Together with supervisors, trainees can review the strategies throughout supervision sessions. With guidance and support, trainees can attempt such strategies within the safety of the supervisory relationship.

Implications for Site Supervisors and Counselor Educators

There are several implications for site supervisors and counselor educators when considering strategies to empower trainees to maximize their supervision experience. Although trainees can take the initiative to implement such strategies independently, some suggestions may require additional collaborative support and guidance from site supervisors and counselor educators. For example, site supervisors and counselor educators could consider introducing the strategies posed in this article during supervision sessions or as assigned reading for discussion. Altogether, engaging in and facilitating these strategies contributes to the development of important dispositional characteristics required of professional school counselors.

Site supervisors and counselor educators have the responsibility to facilitate a supervision environment in which trainees feel empowered to utilize the suggested strategies. This requires them to intentionally balance safety and support with challenge and high expectations (Stoltenberg, 1981). When trainees lack a sense of safety, they may be less likely to self-disclose dilemmas or concerns and more likely to feel shame, which jeopardizes the overall supervision experience and relationship (J. V. Jordan, 2003; Murphy & Wright, 2005). When trainees experience inclusivity in their training programs and move past the discomfort of vulnerability, they can experience growth, strengthen the supervisory relationship, and address their learning goals (Bradley et al., 2019; Giordano et al., 2018). For example, although trainees can take the initiative to suggest norms for supervision, we encourage supervisors to invite or prompt discussions related to trainees’ learning needs and expectations for the supervisory relationship.

Reflection and vulnerability also require rapport and trust for trainees to self-advocate. Further, when trainees can communicate with their supervisors about their needs, supervisors can respond by appropriately facilitating their request for support (Stoltenberg, 1981). During supervision, supervisors also model, teach, and monitor wellness strategies to support trainees’ ethical and professional school counseling practice (Blount et al., 2016). For instance, site supervisors and counselor educators may need to introduce the Johari window framework as a structured reflective exercise, if trainees are not already aware of this tool (Halpern, 2009).

Finally, broaching within supervision may offer a proactive means of exploring dynamics, power, and cultural differences that can bolster the quality and longevity of the supervision experience. However, the onus is typically on supervisors to initiate broaching conversations after they have facilitated a supervision relationship characterized by trust, acceptance, and inclusion (Jones et al., 2019). Supervisors model how to broach topics of race and culture within the dynamics of the supervisory relationship so that trainees can feel empowered to incorporate broaching as an ongoing professional disposition during and beyond supervision. For example, trainees and supervisors are encouraged to explore, model, and role-play recommendations from Bemak and Chung (2008) to move beyond nice counselor syndrome in school counseling practice.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this article provided a variety of practical strategies for SCITs to navigate supervision, it is not intended to be comprehensive and is not without limitations. The suggested strategies have been informed by research to support the supervision process and overall trainee development but may not necessarily be empirically supported. In addition, the strategies may not apply across all supervision contexts, relationships, and circumstances; thus, we encourage trainees to use their best judgment to consider which strategies may be most feasible and useful within their given contexts. Although this article attempted to provide examples specific to the unique work environment and responsibilities that SCITs will encounter, several suggestions provided herein may also apply to counseling trainees working outside of school counseling contexts. Knowing that supervision is an evaluative and hierarchical process, there may be dynamics of power and privilege present that may intimidate or hinder trainees from autonomously attempting and engaging in such strategies. Thus, the power dynamics of supervision may present a barrier for some trainees to self-advocate.

Future research is needed about the characteristics and contributions of trainees that can enhance the supervisory relationship and competence of the supervisor. Researchers could consider a qualitative study to explore SCITs’ experiences of autonomously implemented strategies during supervision as well as a quantitative intervention study to assess the effectiveness of specific strategies to enhance trainee and supervisor development, self-efficacy, and competence. Researchers could also consider strategies specific to site- and university-based supervision that offer evidence for trainees’ growth and competence and later longitudinal impacts of such strategies on personal and professional development.

Conclusion

Considering that supervision is a time-limited experience, these suggested strategies for approaching supervision can inform SCITs (and trainees from other counseling disciplines) about ways to advocate for a quality supervision experience. When trainees are prepared for supervision, they may feel less anxious and more empowered to approach and shape supervision to meet their developmental needs. When trainees are mindful of and actively engaged in reflection, vulnerability, self-advocacy, broaching, and wellness, they can feel empowered to seek support and resources to bridge gaps in their learning and development during the supervision experience. Site supervisors and counselor educators can also share these strategies with trainees and encourage trainees to implement them in fieldwork and university contexts.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2019a). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2019b). ASCA standards for school counselor preparation programs. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/573d7c2c-1622-4d25-a5ac-ac74d2e614ca/ASCA-Standards-for-School-Counselor-Preparation-Programs.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2019c). ASCA school counselor professional standards & competencies. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/a8d59c2c-51de-4ec3-a565-a3235f3b93c3/SC-Competencies.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2021). The school counselor and school counselor supervision. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-School-Counselor-Supervis

American School Counselor Association. (2022). ASCA ethical standards for school counselors. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/44f30280-ffe8-4b41-9ad8-f15909c3d164/EthicalStandards.pdf

Astramovich, R. L., & Harris, K. R. (2007). Promoting self-advocacy among minority students in school counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(3), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00474.x

Baltrinic, E. R., Cook, R. M., & Fye, H. J. (2021). A Q methodology study of supervisee roles within a counseling practicum course. The Professional Counselor, 11(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15241/erb.11.1.1

Bemak, F., & Chung, R. C.-Y. (2008). New professional roles and advocacy strategies for school counselors: A multicultural/social justice perspective to move beyond the Nice Counselor Syndrome. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(3), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00522.x

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2019). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (6th ed.). Pearson.

Biganeh, M., & Young, S. L. (2021). Followers’ perceptions of positive communication practices in leadership: What matters and surprisingly what does not. International Journal of Business Communication, 0(0).

https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488420987277

Bledsoe, K. G., Logan-McKibben, S., McKibben, W. B., & Cook, R. M. (2019). A content analysis of school counseling supervision. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X19838454

Blount, A. J., Taylor, D. D., Lambie, G. W., & Anwell, A. N. (2016). Clinical supervisors’ perceptions of wellness: A phenomenological view on supervisee wellness. The Professional Counselor, 6(4), 360–374.

https://doi.org/10.15241/ab.6.4.360

Borders, L. D., & Brown, L. L. (2005). The new handbook of counseling supervision (1st ed.). Routledge.

Borders, L. D., Glosoff, H. L., Welfare, L. E., Hays, D. G., DeKruyf, L., Fernando, D. M., & Page, B. (2014). Best practices in clinical supervision: Evolution of a counseling specialty. The Clinical Supervisor, 33(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2014.905225

Bradley, L. J., Ladany, N., Hendricks, B., Whiting, P. P., & Rhode, K. M. (2010). Overview of counseling supervision. In N. Ladany & L. J. Bradley (Eds.), Counselor supervision (4th ed.). Routledge.

Bradley, N., Stargell, N., Craigen, L., Whisenhunt, J., Campbell, E., & Kress, V. (2019). Creative approaches for promoting vulnerability in supervision: A relational-cultural approach. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 14(3), 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2018.1562395

Branco, S. F., & Patton-Scott, V. (2020). Practice what we teach: Promoting wellness in a clinical mental health counseling master’s program. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 15(3), 405–412.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2019.1696260

Brott, P. E., DeKruyf, L., Hyun, J. H., LaFever, C. R., Patterson-Mills, S., Cook Sandifer, M. I., & Stone, V. (2021). The critical need for peer clinical supervision among school counselors. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 3(2), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.25774/nr5m-mq71

Cartwright, A. D., Carey, C. D., Chen, H., Hammonds, D., Reyes, A. G., & White, M. E. (2021). Multi-tiered intensive supervision: A culturally-informed method of clinical supervision. Teaching and Supervision in Counseling, 3(2), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.7290/tsc030208

Cook, R. M., & Sackett, C. R. (2018). Exploration of prelicensed counselors’ experiences prioritizing information for clinical supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(4), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12226

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. http://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2016-Standards-with-citations.pdf

Day-Vines, N. L., Bryan, J., & Griffin, D. (2013). The Broaching Attitudes and Behavior Survey (BABS): An exploratory assessment of its dimensionality. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 41(4), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00037.x

Day-Vines, N. L., Wood, S. M., Grothaus, T., Craigen, L., Holman, A., Dotson-Blake, K., & Douglass, M. J. (2007). Broaching the subjects of race, ethnicity, and culture during the counseling process. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00608.x

Dollarhide, C. T., & Saginak, K. A. (2017). Comprehensive school counseling programs: K-12 delivery systems in action (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Dressel, J. L., Consoli, A. J., Kim, B. S. K., & Atkinson, D. R. (2007). Successful and unsuccessful multicultural supervisory behaviors: A Delphi poll. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 35(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2007.tb00049.x

Foster, V. A., & McAdams, C. R., III. (2009). A framework for creating a climate of transparency for professional performance assessment: Fostering student investment in gatekeeping. Counselor Education & Supervision, 48(4), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2009.tb00080.x

Giordano, A. L., Bevly, C. M., Tucker, S., & Prosek, E. A. (2018). Psychological safety and appreciation of differences in counselor training programs: Examining religion, spirituality, and political beliefs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12202

Glosoff, H. L., & Durham, J. C. (2010). Using supervision to prepare social justice counseling advocates. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50(2), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00113.x

Halpern, H. (2009). Supervision and the Johari window: A framework for asking questions. Education for Primary Care, 20(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2009.11493757

Hamlet, H. S. (2022). School counseling practicum and internship: 30+ essential lessons (2nd ed.). Cognella Academic Publishing.

Heaven, C., Clegg, J., & Maguire, P. (2006). Transfer of communication skills training from workshop to workplace: The impact of clinical supervision. Patient Education and Counseling, 60(3), 313–325.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.008

Herlihy, B. J., Gray, N., & McCollum, V. (2002). Legal and ethical issues in school counselor supervision. Professional School Counseling, 6(1), 55–60.

Jones, C. T., Welfare, L. E., Melchior, S., & Cash, R. M. (2019). Broaching as a strategy for intercultural understanding in clinical supervision. The Clinical Supervisor, 38(1), 1–16.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2018.1560384

Jordan, J. V. (2003). Valuing vulnerability: New definitions of courage. Women in Therapy, 31(2–4), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140802146399

Jordan, K. (2018). Trauma-informed counseling supervision: Something every counselor should know about. Asia Pacific Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy, 9(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507686.2018.1450274

King, K. M., & Jones, K. (2019). An autoethnography of broaching in supervision: Joining supervisee and supervisor perspectives on addressing identity, power, and difference. The Clinical Supervisor, 38(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2018.1525597

Ladany, N., Mori, Y., & Mehr, K. E. (2013). Effective and ineffective supervision. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(1), 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012442648

Lambie, G. W., & Sias, S. M. (2009). An integrative psychological developmental model of supervision for professional school counselors-in-training. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87(3), 349–356.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00116.x

Luke, M., & Bernard, J. M. (2006). The School Counseling Supervision Model: An extension of the Discrimination Model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45(4), 282–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00004.x

Marley, E. (2011). Self-help strategies to reduce emotional distress: What do people do and why? A qualitative study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 11(4), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2010.533780

McKibben, W. B., George, A. L., Gonzalez, O., & Powell, P. W. (2022). Exploring how counselor education programs support site supervisors. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 15(2). https://digital

commons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol15/iss2/1

Mecadon-Mann, M., & Tuttle, M. (2023). School counselor professional identity in relation to post-master’s supervision. Professional School Counseling, 27(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X221143932

Mullen, P. R., Backer, A., Chae, N., & Li, H. (2020). School counselors’ work-related rumination as a predictor of burnout, turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and work engagement. Professional School Counseling, 24(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20957253

Murphy, M. J., & Wright, D. W. (2005). Supervisees’ perspectives of power use in supervision. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31(3), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01569.x

Murphy, S., & Kaffenberger, C. (2007). ASCA National Model: The foundation for supervision of practicum and internship students. Professional School Counseling, 10(3), 289–296.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0701000311

Nelson, J. R., Hall, B. S., Anderson, J. L., Birtles, C., & Hemming, L. (2018). Self-compassion as self-care: A simple and effective tool for counselor educators and counseling students. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 13(1), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2017.1328292

Neufeldt, S. A., Karno, M. P., & Nelson, M. L. (1996). A qualitative study of experts’ conceptualizations of supervisee reflectivity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.43.1.3

North, R. A. (2017). Motivational interviewing for school counselors. Independently Published.

Oehrtman, J. P., & Dollarhide, C. T. (2021). Advocacy without adversity: Developing an understanding of micropolitical theory to promote a comprehensive school counseling program. Professional School Counseling, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X211006623

Parikh, S. B., Janson, C., & Singleton, T. (2012). Video journaling as a method of reflective practice. Counselor Education and Supervision, 51(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2012.00003.x

Pearson, Q. M. (2004). Getting the most out of clinical supervision: Strategies for mental health. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 26(4), 361–373. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.26.4.tttju8539ke8xuq6

Pocock, A., Lambros, S., Karvonen, M., Test, D. W., Algozzine, B., Wood, W., & Martin, J. E. (2002). Successful strategies for promoting self-advocacy among students with LD: The LEAD group. Intervention in School and Clinic, 37(4), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/105345120203700403

Quintana, T. S., & Gooden-Alexis, S. (2020). Making supervision work. American School Counselor Association.

Ratts, M. J., & Greenleaf, A. T. (2018). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: A leadership framework for professional school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 21(1b), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18773582

Skovholt, T. M., & Rønnestad, M. H. (1992). Themes in therapist and counselor development. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70(4), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01646.x

Stark, M. D. (2017). Assessing counselor supervisee contribution. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 50(3), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1308224

Stoltenberg, C. (1981). Approaching supervision from a developmental perspective: The counselor complexity model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.28.1.59

Storlie, C. A., Baltrinic, E., Fye, M. A., Wood, S. M., & Cox, J. (2019). Making room for leadership and advocacy in site supervision. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 6(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2019.1575778

Storlie, C. A., Giegerich, V., Stoner-Harris, T., & Byrd, J. (2018). Conceptual metaphors in internship: Creative journeys in counselor development. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 13(3), 331–343.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2018.1439790

Sutton, J. M., Jr., & Page, B. J. (1994). Post-degree clinical supervision of school counselors. The School Counselor, 42(1), 32–39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23901709

Ward, C. C., & House, R. M. (1998). Counseling supervision: A reflective model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 38, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1998.tb00554.x

Watkins, C. E., Jr., Hook, J. N., Mosher, D. K., & Callahan, J. L. (2019). Humility in clinical supervision: Fundamental, foundational, and transformational. The Clinical Supervisor, 38(1), 58–78.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2018.1487355

Wiley, E. D., Phillips, J. C., & Palladino Schultheiss, D. E. (2021). Supervisors’ perceptions of their integration of strength-based and multicultural approaches to supervision. The Counseling Psychologist, 49(7), 1038–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000211024595

Wood, C., & Rayle, A. D. (2006). A model of school counseling supervision: The Goals, Functions, Roles, and Systems Model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45(4), 253–266.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2006.tb00002.x

Woodbridge, L., & O’Beirne, B. R. (2017). Counseling students’ perceptions of journaling as a tool for developing reflective thinking. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 9(2), Article 12.

https://doi.org/10.7729/92.1198

Young, T. L., Lambie, G. W., Hutchinson, T., & Thurston-Dyer, J. (2011). The integration of reflectivity in developmental supervision: Implications for clinical supervisors. The Clinical Supervisor, 30(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2011.532019

Nancy Chae, PhD, NCC, NCSC, ACS, LCPC, is an assistant professor at the University of San Diego. Adrienne Backer, PhD, is an assistant professor at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi. Patrick R. Mullen, PhD, NCC, NCSC, ACS, is an associate professor and department chair at Virginia Commonwealth University. Correspondence may be addressed to Nancy Chae, University of San Diego, Mother Rosalie Hill Hall, 5998 Alcalá Park, San Diego, CA 92110, nchae@sandiego.edu.

Feb 7, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 1

Clare Merlin-Knoblich, Jenna L. Taylor, Benjamin Newman

Social justice is a paramount concept in counseling and supervision, yet limited research exists examining this idea in practice. To fill this research gap, we conducted a qualitative case study exploring supervisee experiences in social justice supervision and identified three themes from the participants’ experiences: intersection of supervision experiences and external factors, feelings about social justice, and personal and professional growth. Two subthemes were also identified: increased understanding of privilege and increased understanding of clients. Given these findings, we present practical applications for supervisors to incorporate social justice into supervision.

Keywords: social justice, supervision, case study, personal growth, practical applications

Social justice is fundamental to the counseling profession, and, as such, scholars have called for an increase in social justice supervision (Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Dollarhide et al., 2018, 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Although researchers have studied multicultural supervision in the counseling profession, to date, minimal research has been conducted on implementing social justice supervision in practice (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). In this study, we sought to address this research gap with an exploration of master’s students’ experiences with social justice supervision.

Social Justice in Counseling

Counseling leaders have developed standards that reflect the profession’s commitment to social justice principles (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). For instance, the American Counseling Association’s ACA Code of Ethics (2014) highlights the need for multicultural and diversity competence in six of its nine sections, including Section F, Supervision, Training, and Teaching. Additionally, in 2015, the ACA Governing Council endorsed the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC), which provide a framework for counselors to use to implement multicultural and social justice competencies in practice (Fickling et al., 2019; Ratts et al., 2015). All of these standards reflect the importance of social justice in the counseling profession (Greene & Flasch, 2019).

Social Justice Supervision

Although much of the counseling profession’s focus on social justice emphasizes counseling practice, social justice principles benefit supervisors, counselors, and clients when they are also incorporated into clinical supervision. In social justice supervision, supervisors address levels of change that can occur through one’s community using organized interventions, modeling social justice in action, and employing community collaboration (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019). These strategies introduce an exploration of culture, power, and privilege to challenge oppressive and dehumanizing political, economic, and social systems (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Garcia et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; Pester et al., 2020). Moreover, participating in social justice supervision can assist counselors in developing empathy for clients and conceptualizing them from a systemic perspective (Ceballos et al., 2012; Fickling et al., 2019; Kiselica & Robinson, 2001). When a supervisory alliance addresses cultural issues, oppression, and privilege, supervisees are better able to do the same with clients (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Thus, counselors become advocates for clients and the profession (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010).

Chang and colleagues (2009) defined social justice counseling as considering “the impact of oppression, privilege, and discrimination on the mental health of the individual with the goal of establishing equitable distribution of power and resources” (p. 22). In this way, social justice supervision considers the impact of oppression, privilege, and discrimination on the supervisee and supervisor. Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) further simplified the definition of social justice supervision, stating that it is “supervision in which social justice is practiced, modeled, coached, and used as a metric throughout supervision” (p. 104). Supervision that incorporates a focus on intersectionality can further support supervisees’ growth in developing social justice competencies (Greene & Flasch, 2019).

Literature about social justice supervision often includes an emphasis on two concepts: structural change and individual care (Gentile et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; Toporek & Daniels, 2018). Structural change is the process of examining, understanding, and addressing systemic factors in clients’ and counselors’ lives, such as identity markers and systems within family, community, school, work, and elsewhere. Individual care acknowledges each person within the counseling setting independent of their environment (Gentile et al., 2009; Roffman, 2002). Scholars advise incorporating both concepts to address power, privilege, and systemic factors through social justice supervision (Chang et al., 2009; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; Greene & Flasch, 2019; Pester et al., 2020).

It is necessary to distinguish social justice supervision from previous literature on multicultural supervision. Although similar, these concepts are different in that multicultural supervision emphasizes cultural awareness and competence, whereas social justice supervision brings attention to sociocultural and systemic factors and advocacy (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; E. Lee & Kealy, 2018; Peters, 2017; Ratts et al., 2015). For instance, a supervisor practicing multicultural supervision would be aware of a supervisee’s identity markers, such as race, ethnicity, and culture, and address those components throughout the supervisory experience, whereas a supervisor practicing social justice supervision would also consider systemic factors that impact a supervisee, in addition to being culturally competent. The supervisor would use that knowledge in the supervisory alliance and act as a change agent at individual and community levels (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; E. Lee & Kealy, 2018; Lewis et al., 2003; Peters, 2017; Ratts et al., 2015; Toporek & Daniels, 2018).

Researchers have found that multicultural supervision contributes to more positive outcomes than supervision without consideration for multicultural factors (Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005). For example, supervisees who participated in multicultural supervision reported that supervisors were more likely to engage in multicultural dialogue, show genuine disclosure of personal culture, and demonstrate knowledge of multiculturalism than supervisors who did not consider multicultural concepts in supervision (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010; Chopra, 2013). Supervisees also reported that multicultural considerations led them to feel more comfortable, increased their self-awareness, and spurred them on to discuss multiculturalism with clients (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010). Although parallel research on social justice supervision is lacking, findings on multicultural supervision are a promising indicator of the potential of social justice supervision.

Models

In recent years, scholars have called for social justice supervision models to integrate social justice into supervision (Baggerly, 2006; Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; O’Connor, 2005). However, to date, only three formal models of social justice supervision have been published. Most recently, Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) recommended a social justice supervision model that can be used with any supervisory theory, developmental model, and process model. In this model, the MSJCC are integrated using four components. First, the intersectionality of identity constructs (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, abilities, etc.) is identified as integral in the supervisory triad between supervisor, counselor, and client. Second, systemic perspectives of oppression and agency for each person in the supervisory triad are at the forefront. Third, supervision is transformed to facilitate the supervisee’s culturally informed counseling practices. Lastly, the supervisee and client experience validation and empowerment through the mutuality of influence and growth (Dollarhide et al., 2021).

Prior to Dollarhide and colleagues’ (2021) model for social justice supervision, Gentile and colleagues (2009) proposed a feminist ecological framework for social justice supervision. This model encouraged the understanding of a person at the individual level through interactions within the ecological system (Ballou et al., 2002; Gentile et al., 2009). The supervisor’s role is to model socially just thinking and behavior, create a climate of equality, and implement critical thinking about social justice (Gentile et al., 2009; Roffman, 2002).

Lastly, Chang and colleagues (2009) suggested a social constructivist framework to incorporate social justice issues in supervision via three delineated tiers (Chang et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; Toporek & Daniels, 2018). In the first tier, self-awareness, supervisors assist supervisees to recognize privileges, understand oppression, and gain commitment to social justice action (Chang et al., 2009; C. C. Lee, 2007). In the second tier, client services, the supervisor understands the clients’ worldviews and recognizes the role of sociopolitical factors that can impact the developmental, emotional, and cognitive meaning-making system of the client (Chang et al., 2009). In the third tier, community collaboration, the supervisor guides the supervisee to advocate for changes on the group, organizational, and institutional levels. Supervisors can facilitate and model community collaboration interventions, such as providing clients easier access to resources, participating in lobbying efforts, and developing programs in communities (Chang et al., 2009; Dinsmore et al., 2002; Kiselica & Robinson, 2001).

Each of these supervision models serves as a relevant, accessible tool for counseling supervisors to use to incorporate social justice into supervision (Chang et al., 2009, Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009). However, researchers lack an empirical examination of any of the models. To address this research gap and begin understanding social justice supervision in practice, the present qualitative case study exploring master’s students’ experiences with social justice supervision was undertaken.

We selected Chang and colleagues’ (2009) three-tier social constructivist framework in supervision for several reasons. First, the social constructivist framework incorporates a tiered approach similar to the MSJCC (Ratts et al., 2015) and reflects social justice goals in the profession of counseling (Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Second, the model is comprehensive. In using three tiers to address social justice (self, client, and community), the model captures multiple layers of social justice influence for counselors. Finally, the model is simple and meets the developmental needs of novice counselors. By identifying three tiers of social justice work, Chang and colleagues (2009) crafted an accessible tool to help new and practicing school counselors infuse social justice into their practice. This high level of structure matches the initial developmental levels of new counselors, who typically benefit from high amounts of structure and low amounts of challenge in supervision (Foster & McAdams, 1998).

Method

The research question guiding this study was: What are the experiences of master’s counseling students in individual social justice supervision? We used a social constructivist theoretical framework and presumed that knowledge would be gained about the participants’ experiences based on their social constructs (Hays & Singh, 2012). The ontological perspective reflected realism, or the belief that constructs exist in the world even if they cannot be fully measured (Yin, 2017).

We selected a qualitative case study methodology because it was the most appropriate approach to explore the experiences of a single group of supervisees supervised by the same supervisor in the same semester. In this approach, researchers examine one identified unit bounded by space, time, and persons (Hancock et al., 2021; Hays & Singh, 2012; Yin, 2017). Qualitative case study research allows researchers to deeply explore a single case, such as a group, person, or experience, and gain an in-depth understanding of that identified situation, as well as meaning for the people involved in it (Hancock et al., 2021; Prosek & Gibson, 2021).

In this study, we selected a case study methodology because the study’s participants engaged in the same supervisory experience at the same counseling program in the same semester, thus forming a case to be studied (Hancock et al., 2021). Given the research question, we specifically used a descriptive case study design, which reflected the study goals to describe participants’ experiences in a specific social justice supervision experience. Case study scholars (Hancock et al., 2021; Yin, 2017) have noted that identifying the boundaries of a case is an essential step in the study process. Thus, the boundaries for this study were: master’s-level school counseling students receiving social justice supervision from the same supervisor (persons) at a medium-sized public university on the East Coast (place) over the course of a 14-week semester (time).

Research Team

Our research team for this study consisted of our first and third authors, Clare Merlin-Knoblich and Benjamin Newman, both of whom received training and had experience in qualitative research. Merlin-Knoblich and Newman both identify as White, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class, and trained counselor educators/supervisors. Merlin-Knoblich is a woman (pronouns: she/her/hers) and former school counselor, who completed master’s and doctoral coursework on social justice counseling and studied social justice supervision in a doctoral program. Newman is a man (pronouns: he/him/his) and clinical mental health/addictions counselor, who completed social justice counseling coursework in a master’s counseling program before completing a doctorate in counselor education and supervision. Our second author, Jenna L. Taylor, was not a part of the research team, but rather was a counseling student unaffiliated with the research participants who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. Taylor identifies as a White, heterosexual, cisgender, and middle-class woman (pronouns: she/her/hers) with prior experience in research courses and on qualitative research teams. Merlin-Knoblich was familiar with all three participants given her role as the practicum supervisor. Taylor and Newman did not know the study participants beyond Newman’s interactions while recruiting and interviewing them for this study.

Participants and Context

Although some scholars of some qualitative research methodologies call for requisite minimum numbers of participants, in case study research, there is no minimum number of participants sufficient to study (Hays & Singh, 2012). Rather, in case study research, researchers are expected to study the number of participants needed to reflect the phenomenon being studied (Hancock et al., 2021). There were three participants in this study because the supervisory experience that comprised the case studied included three supervisees. Adding additional participants outside of the case would have conflicted with the boundaries of the case and potentially interfered with an understanding of the single, designated case in this study.

All study participants identified as White, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class, and English-speaking women (pronouns: she/her/hers). Participants were 23, 24, and 26 years old. All the participants were students in the same CACREP-accredited school counseling program at a public liberal arts university on the East Coast of the United States. Prior to the study, the participants completed courses in techniques, group counseling, school counseling, ethics, and theories. While being supervised, participants also completed a practicum experience and coursework in multicultural counseling and career development.

All participants completed practicum at high schools near their university. One high school was urban, one was suburban, and one was rural. During the practicum experience, participants met with Merlin-Knoblich, their supervisor, for face-to-face individual supervision for 1 hour each week. They also submitted weekly journals to Merlin-Knoblich, written either freely or in response to a prompt, depending on their preference. Merlin-Knoblich then provided weekly written feedback to each participant’s journal entry, and, if relevant, the journal content was discussed during face-to-face supervision. Simultaneously, a university faculty member provided weekly face-to-face supervision-of-supervision to Merlin-Knoblich to monitor supervision skills and ensure adherence to the identified supervision model. The faculty member possessed more than 15 years of experience in supervision and was familiar with social justice supervision models.

Merlin-Knoblich applied Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social constructivist social justice supervision model in deliberate ways throughout the supervisees’ 14-week practicum experience. For example, in the initial supervision sessions, Merlin-Knoblich introduced the supervision model and explained how they would collaboratively explore ideas of social justice in counseling related to their practicum experiences. This included defining social justice, discussing supervisees’ previous background knowledge, and exploring their openness to the idea.

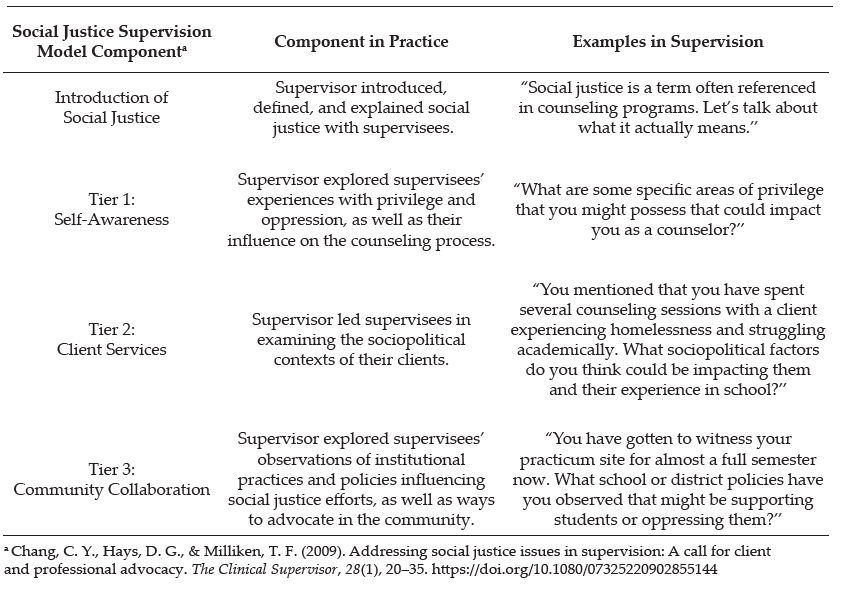

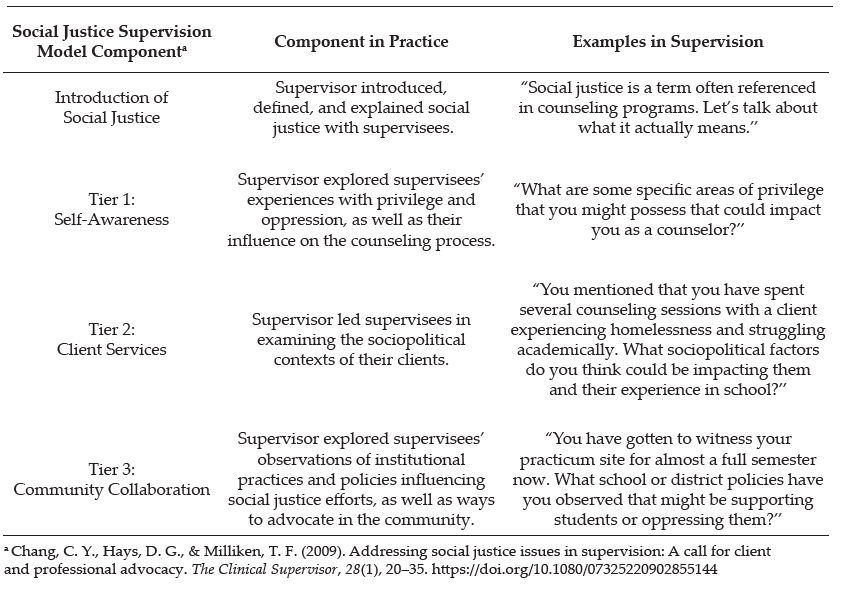

Throughout the first 5 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich used exploratory questions to build participants’ self-awareness (the first tier), particularly around their experiences with privilege and oppression. During the next 5 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich focused on the second tier, understanding clients’ worldviews. They discussed sociopolitical factors and examined how a client’s worldview impacts their experiences. For example, Merlin-Knoblich discussed how a client’s age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, family structure, language, immigrant status, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other factors can influence their experiences. Lastly, in the final 4 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich focused on the third tier of social justice implications at the institutional level. For instance, Merlin-Knoblich initiated discussions about policies at participants’ practicum sites that hindered equity. Merlin-Knoblich also explored the role that participants could take in making resources available to clients, advocating in the community, and using leadership to support social justice. Table 1 summarizes how Merlin-Knoblich implemented Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social justice model.

Table 1

Social Justice Supervision in Practice

Merlin-Knoblich addressed fidelity to the supervision model in two ways. First, in weekly supervision-of-supervision meetings with the faculty advisor, they discussed the supervision model and its use in sessions with participants. The faculty advisor regularly asked about the supervision model and how it manifested in sessions in an attempt to ensure that the model was being implemented recurrently. Secondly, engagement with Newman occurred in regular peer debriefing discussions about the use of the supervision model. Through these discussions, Newman monitored Merlin-Knoblich’s use of the social justice model throughout the 14-week supervisory experience.

Data Collection

We obtained IRB approval prior to initiating data collection. One month after the end of the semester and practicum supervision, Newman approached Merlin-Knoblich’s three supervisees about participation in the study. He explained that participation was an exploration of the supervisees’ experiences in supervision and not an evaluation of the supervisees or the supervisor. Newman also emphasized that participation in the study was confidential, entirely voluntary, and would not affect participants’ evaluations or grades in the practicum course, which ended before the study took place. All supervisees agreed to participate.

Case study research is “grounded in deep and varied sources of information” (Hancock et al., 2021) and thus often incorporates multiple data sources (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). In the present study, we identified two data sources to reflect the need for varied information sources (Hancock et al., 2021). The first data source came from semistructured interviews with participants, a frequent data collection tool in case study research (Hancock et al., 2021). One month after the participants’ practicum experiences ended, Newman conducted and audio-recorded 45-minute individual in-person interviews with each participant using a prescribed interview protocol that explored participants’ experiences in social justice supervision. Newman exercised flexibility and asked follow-up questions as needed (Merriam, 1998).