Counseling and the Interstate Compact: Navigating Ethical Practice Across State Lines

Amanda DeDiego, Rakesh K. Maurya, James Rujimora, Lindsay Simineo, Greg Searls

In the wake of COVID-19, health care providers experienced an immense expansion of telehealth usage across fields. Despite the growth of telemental health offerings, issues of licensing portability continue to create barriers to broader access to mental health care. To address portability issues, the Counseling Compact creates an opportunity for counselors to have privileges to practice in states that have passed compact legislation. Considerations of ethical and legal aspects of counseling in multiple states are critical as counselors begin to apply for privileges to practice through the Counseling Compact. This article explores ethical and legal regulations relevant to telemental health practice in multiple states under the proposed compact system. An illustrative case example and flowcharts offer guidance for counselors planning to apply for Counseling Compact privileges and provide telemental health across multiple states.

Keywords: telehealth, legislation, Counseling Compact, portability, telemental health

Maximizing the use of technology-assisted counseling techniques, telemental health (TMH) is a modality of service delivery that takes the best practices of traditional counseling and adapts practice for delivery via electronic means (National Institute of Mental Health, 2021). There are many terms to describe TMH, which include: distance counseling, technology-assisted services, e-therapy, and tele-counseling (Hilty et al., 2017). Counselors have previously been hesitant in adopting technology-supported counseling practice (Richards & Viganó, 2013). Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, TMH use has grown exponentially in applications across various disciplines (Appleton et al., 2021).

Between March and August 2021, out of all telehealth outpatient visits across disciplines, 39% were primarily for a mental health or substance use diagnosis, up from 24% a year earlier, and 11% two years earlier (Lo et al., 2022). During the same period, 55% of clients in rural areas relied on TMH to access outpatient mental health and substance use services compared to 35% of clients in urban areas. Further, TMH has expanded the accessibility of mental health services to underserved populations, including people living in remote areas, and marginalized groups, including sexual minorities, ethnic and racial minorities, and people with disabilities (Hirko et al., 2020). With broader adoption of TMH, existing issues of licensure portability continue to represent barriers to service provision across state lines. Recent state and national legislation that addresses telehealth parity and clarifies language in the provision of telehealth services supports the continued expansion of TMH (Baumann et al., 2020). Thus, to address portability issues, a partnership of professional counseling organizations engaged in a decades-long effort to address barriers to portability, leading to the recent creation of the Counseling Compact.

With the Counseling Compact legislation having been successfully passed in far more than the required 10 states, the Counseling Compact Commission has convened to create bylaws and informational systems to manage opening applications for privilege to practice in early 2024 (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2021). As counselors venture into a new era with privileges to practice across state lines, consideration of ethical and legal provisions of practice are critical. This article seeks to offer guidance to counselors in how to practice ethically within the privileges of the Counseling Compact. Exploration of ethical guidelines and legal statutes governing practice, a case example of ethical practice, and tools for establishing an ethical process of practice are offered.

Legal and Ethical Considerations for TMH

Provision of TMH may include use of various technology-supported methods of distance counseling. The National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC; 2016) differentiates between face-to-face counseling and distance professional services. Face-to-face services include synchronous interaction between individuals or groups of individuals using visual and auditory cues from the real world. Professional distance services utilize technology or other methods, such as telephones or computers, to deliver services like guidance, supervision, advice, or education.

NBCC (2016) also differentiates counseling services from supervision and consultation for counselors. Counseling represents a working partnership that enables various people, families, and groups to achieve their goals in terms of mental health, well-being, education, and employment. This type of professional relationship differs from supervision, in that supervision is a formal, hierarchical arrangement involving two or more professionals. Consultation is an intentional collaboration between two or more experts to improve the efficiency of professional services with respect to a particular person. NBCC also offers guidance in defining various modalities for the provision of TMH related to counseling, supervision, or consultation (see Table 1). TMH can enhance accessibility to mental health services (Maurya et al., 2020). Barriers to care via TMH include lack of access to video-sharing technologies (e.g., tablet, personal computer, laptop), reliable internet access, private space for using TMH, and adaptive equipment for people with disabilities, as well as a lack of overall digital literacy (Health Resources & Services Administration, 2022). However, with some shared resources and community partnerships, these barriers can be addressed, and TMH can offer broad access to mental health professionals with various expertise and specialty training to begin addressing health disparities (Abraham et al., 2021). Another barrier is the lack of mental health professionals offering TMH services, in part due to challenges in counselor licensing (Mascari & Webber, 2013). TMH barriers also include challenges in counselor training as well as technical and administrative support to implement TMH services with certain client populations (Shreck et al., 2020; Siegel et al., 2021).

Table 1

Common Modalities for Provision of Telemental Health

| Modality | Definition |

| Telephone-based | Information is conveyed across synchronous distance interactions using audio techniques. |

| Email-based | Asynchronous distance interaction in which information is transmitted via written text messages or email. |

| Chat-based | Synchronous distance interaction in which information is received via written messages. |

| Video-based | Synchronous distance interaction in which information is received by video and or audio mechanisms. |

| Social network | Synchronous or asynchronous distance interaction in which information is exchanged via social networking mechanisms. |

Navigating Laws and Ethics

As part of responsible practice, counselors who engage in TMH need to consider ethical considerations and risks. The ACA Code of Ethics (2014) dedicates Section H to “Distance Counseling, Technology, and Social Media” (p. 17). This section was added in the 2014 iteration of the ethical code in recognition of the fact that TMH was a growing tool for the counseling profession (Dart et al., 2016). These ethical guidelines address competency, regulations, use of distance counseling tools, and online practice. According to the most recent counselor liability report from the Healthcare Providers Service Organization (2019), the most common reasons for licensing board complaints within the last 5 years are issues related to sexual misconduct, failure to maintain professional standards, and confidentiality breaches.

Mental health professionals adhere to federal and state laws regarding privacy and security of information stored electronically (Dart et al., 2016). Such federal and state laws have been enacted to protect the privacy and security of information, and counselors must adhere to them in order to avoid legal ramifications (Dart et al., 2016). The ACA Code of Ethics (2014) provides guidelines for counselors to consider when in ethical dilemmas. For example, the ACA Code of Ethics advises counselors to adhere to the laws and regulations of the practice location of the counselor and the client’s place of residence. When working within a counselor’s statutory legislation and regulation, the ACA Code of Ethics directs counselors to address conflicts related to laws and ethics through ethical decision-making models. There are several models for counselors to follow (Levitt et al., 2015; Remley & Herlihy, 2010; Sheperis et al., 2016). Counselors, then, should be familiar with these ethical decision-making models to address ethical dilemmas with consideration of legal statutes in their state of practice. The ACA Code of Ethics strongly aligns with the NBCC Policy Regarding the Provision of Distance Professional Services (2016) providing guidance for National Certified Counselors (NCCs).

Counselors need to ensure compliance with applicable state and federal law in the provision of TMH services. For instance, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is a federal law that establishes legal rules in the security and privacy of medical records, and the electronic storage and transmission of protected health information (Dart et al., 2016). Counselors need to select HIPAA-compliant software and technologies to maintain the security, privacy, and confidentiality of electronic client information. For example, regarding videoconferencing, Skype is not HIPAA-compliant (Churcher, 2012), but VSee and several other vendors have the appropriate level of encryption to meet HIPAA standards for compliance (Dart et al., 2016). Once HIPAA-compliant platform usage is established, counselors need to implement and collect the following information related to clinical documentation: 1) verbal or written consent from client or representative of client in the case of minors or those declared legally unable to provide consent; 2) category of the office visit (e.g., audio with video or audio/telephone only based on acceptable practice in that state); 3) date of last visit or billable visit; 4) physical location of client; 5) counselor location; 6) names and roles of participants (including any potential third parties); and 7) length of visit (Smith et al., 2020). Finally, as part of HIPAA standards, a vendor must offer a Business Associate Agreement (BAA), which demonstrates that the software or tool aligns with HIPAA encryption and privacy standards in communication with clients, transmission of data, and storage of client data (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [HHS], 2013).

During the COVID-19 federal state of emergency, the Office for Civil Rights, tasked with enforcement of HIPAA regulations related to telehealth, exercised discretion and declared the agency would not impose penalties on counselors for lack of compliance in the provision of telehealth, assuming the counselor demonstrates a good faith effort to adhere to standards (HHS, 2021). These guidelines related to the discretion of enforcement cited the use of teleconferencing or chat tools without the adequate level of encryption as allowable, but only during the declared state of emergency.

Ethical Considerations

The scope of practice for counselors varies depending on state licensure laws. It is critical that counselors be familiar with and act in accordance with state licensing laws. For example, if a client is based in a specific physical location, then the counselor needs to adhere to the licensing regulations and scope of practice in that physical location. Some states require licensure where the counselor is located as well as where the client is located. However, there is a lack of specificity in state licensure requirements related to the demonstration of competence with telehealth-specific practices (Williams et al., 2021).

To be able to provide mental health counseling services, mental health counselors need to consider their scope of practice based on state licensure guidelines where the client is located. This scope of practice is defined by the licensing standards of each state. Beyond scope of practice, counselors also need to consider boundaries of competence. The ACA Code of Ethics (2014) is nonspecific about how counselors demonstrate competence, only stating that they should “practice within the boundaries of their competence, based on their education, training, supervised experience and state and national professional credentials” (p. 8). Because of the lack of specificity in state telehealth practices, unless state licensure guidelines explicitly prohibit or advocate for specific telehealth practices, counselors may need to clarify interpretation of statutes or rules with licensure boards to determine specific telehealth practices.

Inherent in a counselor’s responsibility is their ability to screen clients for the appropriateness of telehealth services (Sheperis & Smith, 2021). Counselors are advised to determine whether clients have characteristics that may render them inappropriate for telehealth services, and then to make appropriate referrals (Morland et al., 2015). Some clients may not be appropriate for telehealth because of their (a) inability to access specific technology, (b) rejection of technology during the informed consent process, (c) severe psychosis, (d) mood dysregulation, (e) suicidal or homicidal tendencies, (f) substance use disorder, or (g) cognitive or sensory impairment (Sheperis & Smith, 2021). Finally, counselors are advised to utilize age- and developmentally appropriate strategies for children, adolescents, and older adults (NBCC, 2016; Richardson et al., 2009).

Once service providers, such as counselors, have appropriately screened clients for service, then informed consent is the next step. When counselors provide technology-assisted services, they are tasked to make reasonable efforts to determine clients’ intellectual, emotional, physical, linguistic, and functional capabilities while also appropriately assessing the needs of the client (ACA, 2014). When working with children, counselors need to know the age of the child or adolescent and the client’s legal ability to provide consent (Kramer & Luxton, 2016). Age of consent laws vary between states, so counselors need to familiarize themselves with their specific state legislation. This information is critical for the informed consent process and determining emergency procedures in case of a crisis (Kramer & Luxton, 2016). Counselors then need to consider and complete the informed consent process acknowledging the practice of TMH services.

In the informed consent process, it is imperative that counselors disclose risks related to TMH such as accessibility to technology, technology failure, and data breaches (ACA, 2014). Counselors are required to provide information related to procedures, goals, treatment plans, risks, benefits, and costs of services as part of the informed consent process (Jacob et al., 2011). Other considerations counselors may want to include during the informed consent process include confidentiality and limits of TMH; emergency plans; documentation and storage of information; technological failures; contact between sessions, if any; and termination and referrals (Turvey et al., 2013).

Client Crisis Plans

There are specific steps to ensure appropriate emergency management practices when working with clients via telehealth (Sheperis & Smith, 2021). For example, at intake, these are the steps counselors could take: 1) verify the client’s identity and contact information; 2) verify the current location of the client and their residential address; 3) inquire about other health care providers; 4) navigate conversation regarding contact during emergency and non-emergency situations; and 5) implement a safety plan, if needed (Sheperis & Smith, 2021; Shore et al., 2018). Moreover, counselors need to stay up to date with local state and federal requirements related to duty to warn and protection requirements (Kramer et al., 2015).

For clients and counselors operating in separate cities or states, it is necessary for counselors to gather local law enforcement and emergency service contact information and maintain a plan of action if needed (Shore et al., 2007). Counselors are also advised to plan for service interruptions if and when technical issues arise during a crisis situation (Kramer et al., 2015). Aside from emergency management practices, counselors who engage clients during a crisis still need to apply basic counseling techniques such as unconditional positive regard, congruence, and empathy (Litam & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021). Once a counselor establishes a client’s psychological safety, they can begin to work collaboratively with clients to reestablish safety and predictability; defuse emotions; validate experiences; create specific, objective, and measurable goals; and identify any resources and coping mechanisms (Litam & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021).

Licensure Portability

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as states of emergency were issued at the state and national levels, licensing requirements were waived for the sake of allowing medical professionals to offer continuity of care via telehealth (Slomski, 2020). These time-bound waivers of practice highlighted the need for licensure portability, especially for counselors, even though in many of these states the waivers were difficult to obtain and could be withdrawn at any point when the state of emergency was rescinded. The widened use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic amplified the growing calls for long-term licensure portability options for counselors.

In the United States, counselors experience challenges in transferring licensure between states, as counseling licensure standards vary from state to state (Mascari & Webber, 2013). The profession of counseling, although a relatively new field as compared to other helping professions such as psychology and social work, has been working toward licensure portability over the past 30 years. Since its inception in 1986, the American Association of State Counseling Boards (AASCB) has been focused on advocacy efforts to establish consistency in counseling licensing standards and avenues for licensing portability across states (AASCB, 2022). To advance toward this goal, AASCB first partnered with organizations such as ACA, the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP), and NBCC. Together these groups established the professional identity of counselors through a unified definition of counseling as a profession (Kaplan & Kraus, 2018), as well as consistent training standards for professional counselors across the nation (Bobby, 2013).

In an effort to promote a unified counselor identity and facilitate licensure portability, the 20/20 initiative (Kaplan & Gladding, 2011) included an oversight committee comprised of stakeholders from various organizations to develop a consensus definition of the profession, address prominent issues facing the profession at the time, and develop principles to guide advocacy work in strengthening the counseling profession (Kaplan & Gladding, 2011; Kaplan & Kraus, 2018). Licensure portability was identified as one of these key issues critical for the future of the profession. This issue persisted, with various states assigning different licensure titles, guidelines, requirements, and continuing education standards. Common training standards across specialty areas through CACREP, which merged with the Council on Rehabilitation Education in 2017, promulgate widely used guidelines for counselor licensure (CACREP, 2017). There are various licensure portability models currently used in medical fields: (a) the nonprofit organization model, (b) the mutual recognition model, (c) the licensure language model, (d) the federal model, and (e) the national model (Bohecker & Eissenstat, 2019). In early efforts, Bloom et al. (1990) proposed model licensure language that could be used to establish national licensing standards, which was an effort toward portability under the licensure language model. AASCB previously tried to move toward a national portability system through the nonprofit organization model by establishing the National Credential Registry, which is a central repository for counselor education, supervision, exams, and other information relevant to state licensure (Bohecker & Eissenstat, 2019). However, recently the effort to establish a Counseling Compact for licensure portability under the mutual recognition model gained great momentum in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic (AASCB, 2022).

Licensing Compacts in Medicine and Allied Professions

The National Center for Interstate Compacts (NCIC) provides technical assistance in developing and establishing interstate compact agreements. According to NCIC, interstate compact agreements are legal agreements between governments of more than one state to address common issues or achieve common goals. Counseling is not the first health profession to pursue a licensing compact. Interstate compacts for medicine and allied professions have been established (Litwak & Mayer, 2021). Prior to current efforts for the Counseling Compact, similar legislation introduced compacts for physicians (Adashi et al., 2021), registered nurses (Evans, 2015), physical therapists (Adrian, 2017), psychologists (Goodstein, 2012), speech pathologists (Morgan et al., 2022), and emergency medical personnel (Manz, 2015). Other efforts to pass licensing compacts are underway for social workers (Apgar, 2022) and nurse practitioners (Evans, 2015). These compact models include multistate licensing (MSL) or privilege-to-practice (PTP) structures. A single multistate license obtained through the MSL model would allow a practitioner to practice equally in all member states, as opposed to the PTP model in which a practitioner would be licensed in their designated home state and then allowed specific privileges to use that license in other places (Counseling Compact, n.d.).

MSL compacts include licensing effective in multiple states. The MSL model is used for the Nurse Licensure Compact (Interstate Commission of Nurse Licensure Compact Administrators, 2021; National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2015). Nurses licensed within this compact system gain multistate licenses across all member states. The Nurse Licensure Compact legislation notes efforts to reduce redundancies in nursing licensure by using an MSL model. Draft legislation within the Nurse Licensure Compact MSL system defines a “multistate license” as a license awarded in a home state that also allows a nurse the ability to practice in all other member states under the said multistate license. This includes both in-person and remote practice. So, for example, a nurse in a compact state can be vetted and licensed through the central compact system, which allows traveling nurses to switch between placements rapidly without additional licensing required for compact states. On the other hand, non-compact states issue a “single state license” which does not allow practice across states.

The PTP licensing model is used by physical therapy and EMS professionals. PTP establishes an agreement between member states to grant legal authorization to permit counselors to practice (NCIC, 2020). Unlike the MSL structure, counseling licensure is still maintained by a single state, or “home state,” but member states allow privileges to practice with clients located in other states as part of the compact agreement. This licensing model includes the definition of a “single state license,” which indicates that licenses issued by the state do not by default allow practice in any other states but the home state (Interstate Commission of Nurse Licensure Compact Administrators, 2021). Further, definitions include “privilege to practice,” which allows legal authorization of practice in each designated remote state. The Counseling Compact uses this PTP model for portability of licensing privileges across member states (Counseling Compact, 2020).

The Counseling Compact

Development of the Counseling Compact began in 2019 as a solution to the challenges of licensure portability. Historically, navigating varying licensure standards across states represented a barrier to the portability of counseling professionals and access to services for the community (Mascari & Webber, 2013). To address these barriers, organizations including NBCC (2017), ACA (2018), American Mental Health Counselors Association (2021), and AASCB (2022) have worked to unify the profession, establish common minimum licensing standards across states, and create and promote the Counseling Compact. With the support of NCIC, draft legislation for a PTP compact was developed by the end of 2020 and followed by advocacy efforts to pass legislation in a minimum of 10 states to begin the process of establishing the Counseling Compact (ACA, 2021). As of October 2023, the Counseling Compact has been passed as law in a growing list of states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming, with legislation pending in several other states (Counseling Compact, 2022).

Compact Standards

The model legislation for the Counseling Compact outlines the provisions of the PTP model used (Counseling Compact, 2020). Within these regulations, only independently licensed counselors can apply for compact privileges. Each state maintains its own licensing standards and processes separately. PTP applies equally to both in-person and TMH services. Within the regulations of the compact, each counselor establishes a home state in which they hold a primary license. Prior to the compact, a counselor would have to seek additional licensure in other states to provide service to clients. However, under the PTP Counseling Compact, counselors who hold an unencumbered license may apply for privileges to use their home license in another state without seeking an additional formal license.

Counselors may choose the states in which they apply for privileges to practice under the compact. Differing from the MSL model, under the Counseling Compact, counselors would need to apply for privileges in individual states where they wish to practice if these states have passed legislation to join the compact group (Counseling Compact, n.d.). This may involve passing jurisprudence exams for some states. However, licensing renewal and continuing education would only be required in accordance with the home state standards and process (Counseling Compact, 2020). According to the model legislation, each state is also able to set a fee for privileges to practice. A central Compact Commission oversees the process of privilege applications and exchange of information regarding ethical violations across privilege states.

As states have varying titles for professional counselors, the general requirements for compact eligibility include counselors who have taken and passed a national exam, have completed required supervision in accordance with their home state requirements, and hold a 60–semester-hour, or 90–quarter-hour, master’s degree. There is language in the model legislation specifying that counselors need to complete 60 semester hours, or 90 quarter hours, of graduate coursework in areas with a counseling focus to accommodate states that do not require a 60-hour master’s degree for licensure. The Counseling Compact (2020) does not include other professions (e.g., marriage and family therapists) and, for the purposes of defining applicable counseling license types, requires counselors be able to independently assess, diagnose, and treat clients. A key element of the Counseling Compact is that counselors are required to adhere to the individual state regulations and rules for each state where they exercise PTP. In the future, this may ultimately mean that counselors must simultaneously understand and navigate rules and regulations for potentially 20 different states as they practice using TMH across state lines. The following illustrative case example describes Sam, a licensed professional counselor, who requests privileges to practice online with a client in another state through the Counseling Compact.

Case Example

Ethical practice in multiple states entails more than just applying for privileges through the Compact Commission. The following case example illustrates how an independently licensed professional counselor would provide services in multiple states as part of the Counseling Compact. The compact provides avenues for the expansion of the availability of TMH services. However, counselors must mindfully apply ethical guidelines and adhere to state rules in using such privileges to practice, thus avoiding licensing complaints, liability, and client harm.

The Case of Sam

Sam is an independently licensed professional counselor in their home state of Nebraska. Sam has the National Certified Counselor (NCC) and Board Certified-TeleMental Health Provider (BC-TMH) credentials. Nebraska just passed legislation and became part of the Counseling Compact. To practice as part of the Counseling Compact, Sam first confirms which states are members of the compact. Then Sam joins the compact through the Nebraska Board for Mental Health Practice. Sam has two potential clients for whom they would like to provide TMH services. These clients reside in Utah and Colorado. Sam verifies that both states have passed legislation to be part of the Counseling Compact. Sam applies for privileges in both Utah and Colorado. Sam is required to take a jurisprudence exam before being granted privileges in Colorado through the compact. Sam also may be required to pay fees for privileges in these states. After Sam is approved for privileges in Colorado and Utah through the Compact Commission, they are ready to practice via TMH in each state. Sam creates separate professional disclosure statements they will use for clients in Colorado and Utah. They create necessary forms and consider how they will verify the location and identity of the clients they will see via TMH. Sam reads and understands all rules and statutes for Utah and Colorado related to licensure. This includes understanding the scope of practice and any unique rules of conducting TMH in these states. Sam also makes sure their professional disclosure statements meet all requirements for Utah and Colorado.

As part of their professional disclosure, Sam creates a TMH guide for clients that includes concerns and risks about counseling online, with a troubleshooting guide if the internet is unstable. This disclosure provides tips for privacy during an online counseling session for the client. The disclosure also outlines the steps Sam will use to increase confidentiality, such as wearing headphones and conducting practice in a designated private space. Sam will also be using an online telehealth platform that provides a BAA and appropriate encryption for HIPAA compliance. This platform also allows for secure document signing and document transfer. Sam creates a protocol for TMH, which includes verifying client identity with a copy of photo identification provided as part of the intake process. Sam also plans to complete a safety plan with each new client in Utah and Colorado as part of the intake process. This safety plan will include a release of information to contact a local support person in case of an emergency and looking up the local law enforcement dispatch phone numbers for the client’s primary location in case of emergency. Sam also is sure to let all clients know about the 988 National Suicide Lifeline as part of this process.

Sam’s protocols also include asking the client to verify their location verbally at the beginning of each session and documenting this in their case notes. Sam also notes in their protocols they must have new forms completed should a client move their primary residence, verifying the client is still in a state where Sam has privileges. Once Sam has updated the appropriate forms and created their protocols, they begin to engage in services with their new clients using privileges from the Counseling Compact. After a few weeks, Sam gets a referral for a new client located in Florida. Because Florida has passed legislation to be part of the Counseling Compact, Sam repeats this process in working through the compact to gain privileges to practice in Florida and creates a new disclosure statement for this state.

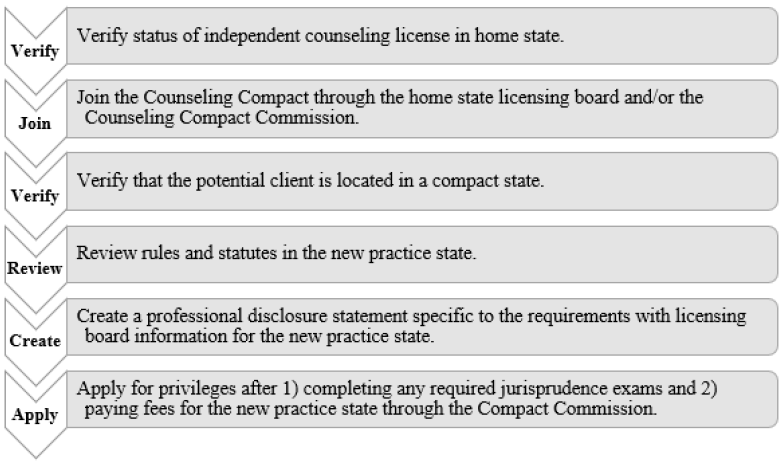

Practicing With Compact Privileges

To gain privileges to practice, according to Counseling Compact legislation (Counseling Compact, 2020), Sam would be responsible for submitting paperwork to their licensing board as well as paying any required fees to participate in the compact. Not doing so would be considered practicing without a license in those states. Therefore, in the case example, Sam did not automatically gain privileges to practice in all compact states as soon as Nebraska passed the Counseling Compact legislation. They had to apply for state privileges once they joined the compact through their home state of Nebraska (see Figure 1). Though counselors will not be required to meet any additional reciprocity requirements, they could be required to take the jurisprudence exam for specific states before they are able to provide services (Counseling Compact, 2020).

Figure 1

Flowchart for Seeking Compact Privileges in Another State

Beyond applying for privileges through the Compact Commission, Sam will need to consider other administrative aspects of TMH practice to engage in ethical practice (ACA, 2014, H.1.a.), which would support their ability to later work through ethical dilemmas and avoid disciplinary action with their licensing board. For each compact state, Sam will be responsible for reading, understanding, and abiding by all rules and statutes for the states in which they practice (ACA, 2014, H.1.b.). This means being responsible for the rules of not just their home state, but of all states in which they hold privileges. This may entail having various scopes of practice or rules in different states. Sam would need to review the rules for Utah, Colorado, and Florida to ensure their typical treatment modalities would be permitted under the scope of practice in each state. For example, in some states Sam may not be able to provide a client with a diagnosis according to their counseling scope of practice.

With each state having its own rules, statutes, and licensing board, it would be considered best practice for Sam to have a disclosure statement that is specific to each compact state. Sam will be responsible for having updated disclosure statements that align with the rules and statutes for each compact state licensing board to review as well as for their prospective clients within each compact state. For both the benefit of the client and the protection of Sam, Sam’s disclosure statements will include their Nebraska licensing information, information about the Counseling Compact as well as a definition of PTP, and information specific to the corresponding compact state licensing board if the client needs to file a complaint. For clients in Utah, complaints would be filed with the Utah Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing. For clients in Colorado, complaints would be filed with the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies. In Florida, complaints would be filed with the Florida Department of Health. Sam’s disclosure statements for each state would need to have this information listed. Complaints filed in privilege states would potentially result in revocation of PTP in said state, and disciplinary actions would be reported to the Compact Commission.

The Counseling Compact also does not include insurance billing privileges for each state, so Sam will need to explore the ability to join insurance panels or be approved to bill Medicaid in each state. They may also choose to only take out-of-pocket fees for clients in different states, in which case they would need to consider a means of securely collecting payments or working with a billing service.

TMH Practice

When Sam is providing TMH services in the states of Colorado, Florida, and Utah via the Counseling Compact, they need to complete and obtain informed consent, which is a necessary standard of care (ACA, 2014, H.2.a.). When generating informed consent, Sam needs to gain consent (in writing) in real time and in accordance with the laws of all practice states, as some states have specific regulations (Kramer et al., 2015). Further, consent needs to be gained if the session needs to be recorded for any reason (e.g., consultation, education, legal). Then Sam needs to ensure their telehealth platform/software is secure, private, confidential, and in compliance with HIPAA, as it is important for them to use appropriate technologies, understand privacy requirements, and attend to any issues related to liability of technology use to ensure compliance with their scope of practice (Kramer et al., 2015).

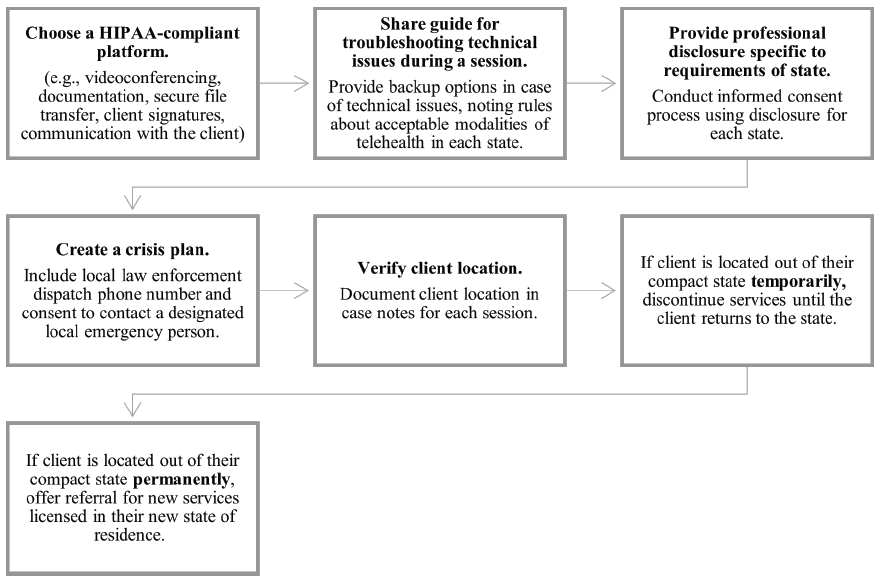

Sam will need to consider a workflow of administrative protocols related to their TMH work (see Figure 2). This will address ethical issues that could arise when working with clients in multiple states. Sam has sought additional training with their BC-TMH credential to help with competency and considerations of ethical practice for TMH. Before engaging in TMH practice, Sam has prepared for the addition of these services by creating guidelines for clients to access online services (ACA, 2014, H.4.e.). Sam selected an online platform that includes secure video conferencing, case note storage, and file

transfer. Sam has arranged to use a HIPAA-compliant video platform with a BAA, and they have considered how to facilitate secure exchange of files with clients and how to obtain client signatures securely from a distance. Sam would also need to make this BAA available to clients upon request. If Sam opted to transfer documents virtually via email, the files would need to be encrypted and password protected, and Sam would need to make sure methods of communication meet state regulations regarding encryption. Discussing in detail with the client the most secure way to provide documentation in accordance with state statutes will be important (ACA, 2014, H.2.d.). Considering potential barriers of insurance billing for clients in other states, Sam has created a specific Good Faith Estimate of cost for each state with an out-of-pocket rate listed using a sliding scale to comply with the No Surprises Act (U.S. Department of Labor, 2022). Sam will also consider managing crises with clients in other states.

Figure 2

Workflow for Ethical Telehealth Services Across State Lines Under the Counseling Compact

Additional Considerations

Although Sam has considered how to verify the identity and location of each client (ACA, 2014, H.3.), there is still the possibility a client reports to Sam they are in a compact state, when in fact they are not in a compact state either temporarily or permanently. This could lead to a formal complaint that Sam, unknowingly, was practicing in a non-compact state where they are not licensed. To prevent possible disciplinary action, Sam asks the client where they are located at the beginning of each session, even if they recognize the background of the client. Sam is sure to document the location of both themselves and the client in the clinical note for each session. Sam also makes sure to document where the client is living, working, or going to school. If possible, the client’s insurance policy or photo identification should corroborate their location. Sam will need to have this documentation in the event of a formal complaint. In this case, Sam could demonstrate due diligence in confirming the client’s location is within a compact state where Sam has privileges. Sam can then show the corresponding licensing boards and the Compact Commission they believed they were practicing within the compact to the best of their knowledge.

If a client moves, Sam will need to document the new mailing, work, or school addresses. This and any other corresponding information would lead Sam to believe the client is in the reported location which is in fact within a compact state where Sam holds privileges. Finally, it is important to note that if Sam or the client moves out of the compact state and into a state not part of the compact, services must immediately stop. Sam has included this in every disclosure that they offer a client (ACA, 2014, H.2.a.). Sam states in the disclosure that if either party relocates outside of a compact state, Sam is then responsible for finding the client possible referrals either in the client’s location or within the compact so the client can continue care. By discussing this at the beginning of the therapeutic relationship as part of informed consent, Sam makes the transition easier and more efficient for the client if a transfer of care needs to occur. In thoughtfully preparing to use privileges offered through the Counseling Compact, Sam has carefully ensured they are engaging in ethical and legal TMH practice from first contact with a client to termination of services.

Finally, it would be helpful for Sam to identify individuals with whom they can consult should ethical issues arise (ACA, 2014, I.2.c.). Ideally, these individuals would have good knowledge of TMH. Sam might also take advantage of consultation opportunities through their state licensing board and professional organizations. Sam would also identify an ethical decision-making model to use when ethical dilemmas arise to document how ethical decisions were made (ACA, 2014, I.1.b.).

Implications for Telehealth Practice via the Counseling Compact

The Compact Commission is in the process of setting up systems and processes for granting privileges for compact states. The application process for compact privileges is anticipated to open in 2024. Counselors who hope to participate in the Counseling Compact should first verify that the state in which they currently practice has passed legislation to become part of the compact. If that is not the case, there is an opportunity for advocacy with state legislatures to pass compact legislation to allow their state to join the Compact Commission. Counselors who are practicing in states that have already passed Counseling Compact legislation should review their TMH workflow and guidelines. There is an opportunity to establish administrative workflows and documentation, as well as review HIPAA compliance of all electronic systems being used for current practice.

Counselors should also review malpractice insurance policies to ensure TMH is covered by their current policy. Counselors may begin to research and review statutes and rules for states where they hope to gain privileges as part of the compact. They may also prepare for jurisprudence exams if required in states where they hope to have privileges. Counselors can also draft a professional disclosure statement and other necessary documents for TMH that can be adapted for different states.

Given the forthcoming revision of the ACA Code of Ethics, we propose that the H.1. Knowledge and Legal Considerations section be updated to incorporate additional guidelines for conducting ethical telehealth practice. Notably, these guidelines should emphasize the establishment of a crisis plan when rendering telehealth services, including a local law enforcement dispatch phone number and consent for disclosure for a designated local emergency contact. Counselors also have an ethical obligation to be familiar with local referral resources when working with clients in different states. Furthermore, the ACA Code of Ethics should underscore the necessity of a telehealth protocol or workflow as preparation for engaging in ethical telehealth practice.

Conclusion

The Counseling Compact creates new and exciting possibilities for counselors to have improved portability of licensure through practice privileges. The compact also addresses barriers to broader access and equity in TMH for various populations across the nation. However, before counselors enroll in the compact, there is a critical need to consider how to engage in TMH ethically when working with clients online in different states. The included guidelines and example workflow processes are important considerations for counselors preparing to apply for privileges within the Counseling Compact. These preparatory steps will help counselors to be prepared to apply for compact privileges when the portal becomes available.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Abraham, A., Jithesh, A., Doraiswamy, S., Al-Khawaga, N., Mamtani, R., & Cheema, S. (2021). Telemental health use in the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review and evidence gap mapping. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 748069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.748069

Adashi, E. Y., Cohen, I. G., & McCormick, W. L. (2021). The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact: Attending to the underserved. JAMA, 325(16), 1607–1608. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1085

Adrian, L. (2017). The Physical Therapy Compact: From development to implementation. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 9(2), 59–62. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2017.6237

American Association of State Counseling Boards. (2022). History of AASCB. https://wwwaascborg.wildapricot.org/History-of-AASCB

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

American Counseling Association. (2018). ACA takes action toward interstate licensure portability. https://www.counseling.org/news/aca-blogs/aca-government-affairs-blog/aca-government-affairs-blog/2018/12/19/aca-takes-action-toward-interstate-licensure-portability

American Counseling Association. (2021). Counseling compact. https://www.counseling.org/government-affairs/counseling-compact

American Mental Health Counselors Association. (2021). Counselor licensure interstate portability endorsement and reciprocity plan.

Apgar, D. (2022). Social work licensure portability: A necessity in a post-COVID-19 world. Social Work, 67(4), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swac031

Appleton, R., Williams, J., Vera San Juan, N., Needle, J. J., Schlief, M., Jordan, H., Sheridan Rains, L., Goulding, L., Badhan, M., Roxburgh, E., Barnett, P., Spyridonidis, S., Tomaskova, M., Mo, J., Harju-Seppänen, J., Haime, Z., Casetta, C., Papamichail, A., Lloyd-Evans, B., . . . Johnson, S. (2021). Implementation, adoption, and perceptions of telemental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(12), e31746. https://doi.org/10.2196/31746

Baumann, B. C., MacArthur, K. M., & Michalski, J. M. (2020). The importance of temporary telehealth parity laws to improve public health during COVID-19 and future pandemics. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 108(2), 362–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.05.039

Bloom, J., Gerstein, L. H., Tarvydas, V., Conaster, J., Davis, E., Kater, D., Sherrard, P., & Esposito, R. (1990). Model legislation for licensed professional counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 68(5), 511–523.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01402.x

Bobby, C. L. (2013). The evolution of specialties in the CACREP standards: CACREP’s role in unifying the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00068.x

Churcher, J. (2012). On: Skype and privacy. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 93(4), 1035–1037.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-8315.2012.00610.x

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2017). Fall 2017 CACREP connection. https://www.cacrep.org/newsletter/fall-2017-cacrep-connection/#accreditation

Counseling Compact. (n.d.). Interstate compacts vs. universal license recognition. https://counselingcompact.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Compacts-Universal-Recognition-Explained-Final-Counseling-Compact.pdf

Counseling Compact. (2020). Counseling compact model legislation. https://counselingcompact.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Final_Counseling_Compact_.pdf

Counseling Compact. (2022). Compact map. https://counselingcompact.org/map

Dart, E. H., Whipple, H. M., Pasqua, J. L., & Furlow, C. M. (2016). Legal, regulatory, and ethical issues in telehealth technology. In J. K. Luiselli & A. J. Fischer (Eds.), Computer-assisted and web-based innovations in psychology, special education, and health (pp. 339–363). Academic Press.

Evans, S. (2015). The Nurse Licensure Compact: A historical perspective. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 6(3), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2155-8256(15)30778-x

Goodstein, L. D. (2012). The interstate delivery of psychological services: Opportunities and obstacles. Psychological Services, 9(3), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027821

Healthcare Providers Service Organization. (2019). Counselor liability claim report: 2nd edition. https://www.hpso.com/getmedia/ac13a1d8-3bdd-4117-ad36-8fba7c419153/counselor-claim-report-second-edition.pdf

Health Resources & Services Administration. (2022). Health equity in telehealth. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/health-equity-in-telehealth

Hilty, D. M., Maheu, M. M., Drude, K. P., Hertlein, K. M., Wall, K., Long, R. P., & Luoma, T. L. (2017). Telebehavioral health, telemental health, e-therapy and e-health competencies: The need for an interprofessional framework. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 2(3), 171–189.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-017-0036-0

Hirko, K. A., Kerver, J. M., Ford, S., Szafranski, C., Beckett, J., Kitchen, C., & Wendling, A. L. (2020). Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for rural health disparities. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(11), 1816–1818. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa156

Interstate Commission of Nurse Licensure Compact Administrators. (2021). Final rules. https://www.ncsbn.org/public-files/FinalRulesadopted81120clean_ed.pdf

Jacob, S., Decker, D. M., & Hartshorne, T. S. (2011). Ethics and law for school psychologists (6th ed.). Wiley.

Kaplan, D. M., & Gladding, S. T. (2011). A vision for the future of counseling: The 20/20 Principles for Unifying and Strengthening the Profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 367–372.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00101.x

Kaplan, D. M., & Kraus, K. L. (2018). Building blocks to portability: Culmination of the 20/20 initiative. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(2), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12195

Kramer, G. M., Kinn, J. T., & Mishkind, M. C. (2015). Legal, regulatory, and risk management issues in the use of technology to deliver mental health care. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(3), 258–268.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.04.008

Kramer, G. M., & Luxton, D. D. (2016). Telemental health for children and adolescents: An overview of legal, regulatory, and risk management issues. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(3), 198–203. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2015.0018

Levitt, D. H., Farry, T. J., & Mazzarella, J. R. (2015). Counselor ethical reasoning: Decision-making practice versus theory. Counseling and Values, 60(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2015.00062.x

Litam, S. D. A., & Hipolito-Delgado, C. P. (2021). When being “essential” illuminates disparities: Counseling clients affected by COVID-19. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12349

Litwak, J. B., & Mayer, J. (2021). Developments in interstate compact law and practice 2020. Urban Lawyer, 51(1), 99–100. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/state_local_government/publications/urban_lawyer/2021/51-1/developments-interstate-compact-law-and-practice-2020

Lo, J., Rae, M., Amin, K., Cox, K., Panchal, N., & Miller, B. F. (2022). Telehealth has played an outsized role meeting mental health needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical Benefits, 39(7), 8–9.

Manz, D. (2015). Legislation, regulation, and ordinance. In D. C. Cone, J. H. Brice, T. R. Delbridge, & J. B. Myers (Eds)., Emergency medical services: Clinical practice and systems oversight, clinical aspects of EMS (2nd ed., pp. 36–43). Wiley.

Mascari, J. B., & Webber, J. (2013). CACREP accreditation: A solution to license portability and counselor identity problems. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00066.x

Maurya, R. K., Bruce, M. A., & Therthani, S. (2020). Counselors’ perceptions of distance counseling: A national survey. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 10(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.18401/2020.10.2.3

Morgan, S. D., Zeng, F.-G., & Clark, J. (2022). Adopting change and incorporating technological advancements in audiology education, research, and clinical practice. American Journal of Audiology, 31(3S), 1052–1058. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_aja-21-00215

Morland, L. A., Poizner, J. M., Williams, K. E., Masino, T. T., & Thorp, S. R. (2015). Home-based clinical video teleconferencing care: Clinical considerations and future directions. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(6), 504–512. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1082986

National Board for Certified Counselors. (2016). National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC) policy regarding the provision of distance professional services.

National Board for Certified Counselors. (2017). Joint statement on a national counselor licensure endorsement process. https://www.nbcc.org/assets/portability/portability-statement-endorsement-process.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2015). Nurse licensure compact.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2021). What is telemental health? (NIH Publication No. 21-MH-8155). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/health/publications/what-is-telemental-health/what-is-telemental-health.pdf

Remley, T. P., Jr., & Herlihy, B. (2010). Ethical, legal, and professional issues in counseling (3rd ed.). Merrill.

Richards, D., & Viganó, N. (2013). Online counseling: A narrative and critical review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(9), 994–1011. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21974

Richardson, L. K., Frueh, B. C., Grubaugh, A. L., Egede, L., & Elhai, J. D. (2009). Current directions in videoconferencing tele-mental health research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 16(3), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01170.x

Sheperis, D. S., Henning, S. L., & Kocet, M. M. (2016). Ethical decision making for the 21st century counselor. SAGE.

Sheperis, D. S., & Smith, A. (2021). Telehealth best practice: A call for standards of care. Journal of Technology in Counselor Education and Supervision, 1(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.22371/tces/0004

Shore, J. H., Hilty, D. M., & Yellowlees, P. (2007). Emergency management guidelines for telepsychiatry. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29(3), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.01.013

Shore, J. H., Yellowlees, P., Caudill, R., Johnston, B., Turvey, C., Mishkind, M., Krupinski, E., Myers, K., Shore, P., Kaftarian, E., & Hilty, D. (2018). Best practices in videoconferencing-based telemental health April 2018. Telemedicine and e-Health, 24(11), 827–832. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0237

Shreck, E., Nehrig, N., Schneider, J. A., Palfrey, A., Buckley, J., Jordan, B., Ashkenazi, S., Wash, L., Baer, A. L., & Chen, C. K. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to implementing a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Telemental Health (TMH) program for rural veterans. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 44(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000129

Siegel, A., Zuo, Y., Moghaddamcharkari, N., McIntyre, R. S., & Rosenblat, J. D. (2021). Barriers, benefits and interventions for improving the delivery of telemental health services during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A systematic review. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(4), 434–443.

https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000714

Slomski, A. (2020). Telehealth success spurs a call for greater post–COVID-19 license portability. JAMA, 324(11), 1021–1022. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9142

Smith, W. R., Atala, A. J., Terlecki, R. P., Kelly, E. E., & Matthews, C. A. (2020). Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 231(2), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.030

Turvey, C., Coleman, M., Dennison, O., Drude, K., Goldenson, M., Hirsch, P., Jueneman, R., Kramer, G. M., Luxton, D. D., Maheu, M. M., Malik, T. S., Mishkind, M. C., Rabinowitz, T., Roberts, L. J., Sheeran, T., Shore, J. H., Shore, P., van Heeswyk, F., Wregglesworth, B., . . . Bernard, J. (2013). ATA practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. Telemedicine and e-Health, 19(9), 722–730.

https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2013.9989

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2013). Business associate contracts. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/covered-entities/sample-business-associate-agreement-provisions/index.html

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2021). Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html

U.S. Department of Labor. (2022). Requirements related to surprise billing: Final rules. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs/requirements-related-to-surprise-billing-final-rules-2022.pdf

Williams, A. E., Weinzatl, O. L., & Varga, B. L. (2021). Examination of family counseling coursework and scope of practice for professional mental health counselors. The Family Journal, 29(1), 10–16.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720978536

Amanda DeDiego, PhD, NCC, BC-TMH, LPC, is an associate professor at the University of Wyoming. Rakesh K. Maurya, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of North Florida. James Rujimora, MEd, EdS, is a doctoral student at the University of Central Florida. Lindsay Simineo, MA, NCC, LPC, is Legislative Advocate for the Wyoming Counseling Association. Greg Searls is Executive Director of Professional Licensing Boards for the Wyoming Department of Administration & Information. Correspondence may be addressed to Amanda DeDiego, 125 College Dr, UU 431, Casper, WY 82601, adediego@uwyo.edu.