Genevieve Weber-Gilmore, Sage Rose, Rebecca Rubinstein

Internalized homophobia, or the acceptance of society’s homophobic and antigay attitudes, has been shown to impact the coming out process for LGB individuals. The current study examined the relationship between levels of outness to family, friends and colleagues and internalized homophobia for 291 lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Results suggest internalized homophobia is a predictor of outness to friends, colleagues, and extended family, but not nuclear family. A discussion of these findings as well as implications for counselors are provided.

Keywords: internalized homophobia, “coming out,” lesbian, gay, bisexual

Lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals (LGB) have been shown to be one of the most stressed population groups in society (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007). Beyond dealing with daily stressors common with their heterosexual counterparts, LGB individuals experience unique stressors such as homophobia, societal discrimination and limited social and institutional supports due to their same-gender sexual orientations. Homophobia is defined as the anxiety, aversion, and discomfort that some individuals experience in response to being around, or thinking about LGB behavior or people (Davies, 1996; Spencer, & Patrick, 2009).

Homophobia is endorsed through the perpetuation of negative stereotypes about LGB behavior and people on both societal and individual levels, and the discrimination and prejudice of LGB people across the lifespan (Bobbe, 2002; Davies, 1996; Spencer & Patrick, 2009). Subtle forms of homophobia and discrimination such as the exclusion of LGB couples in the media and blatant acts of alienation experienced when individuals refuse to rent to LGB people are far too common in the lives of LGB individuals (Neisen, 1990; Smiley, 1997). Other examples of homophobia include unfair treatment by family, friends, and peers; loss of employment or lack of promotions; and observing/hearing people making anti-gay jokes (King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008; Rankin, Weber, Blumenfeld, & Frazer, 2010). These homophobic events greatly affect the lives of LGB individuals such that many LGB individuals hide their sexual orientation from others and feel shame and other negative feelings towards themselves (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT], 2001).

Higher levels of stress are common among LGB individuals who feel they have to hide their sexual orientation from others (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007) or have negative feelings towards themselves based on their same-gender sexual attractions (Weber, 2008). The acceptance of society’s homophobic and anti-gay attitudes about LGB sexual orientations is known as internalized homophobia. Low self-esteem and low self-acceptance; shame; guilt; depression and anxiety; feelings of inadequacy and rejection; verbal and physical abuse by family, partners, and/or peers; homelessness; prostitution; substance use and abuse; and suicide are some of the common feelings or behaviors that are associated with internalized homophobia (CSAT, 2001; Diamond & Wilsnack, 1978; Grossman, 1996; Lewis, Saghir, & Robins, 1982; Ross & Rosser, 1996; Saghir & Robins, 1973; Spencer, & Patrick, 2009; Stall & Wiley, 1988; Stein & Cabaj, 1996). According to Bobbe (2002), the negative feelings and behaviors associated with internalized homophobia can have a more painful and disruptive influence on the health of LGB individuals than external, overt forms of oppression such as prejudice and discrimination.

Homophobia and internalized homophobia have been shown to impact the coming out process for LGB individuals. “Coming out” is a shortened term for “coming out of the closet” (Hunter, 2007, p. 41). As LGB individuals begin to disclose their sexual orientation to others, or “come out,” they often experience a series of stages that include but are not limited to an initial awareness of being different, grieving, feelings of inner conflict, and an established sexual minority identity with long-term relationships. This is a developmental process that involves a person’s awareness and acknowledgement of same-gender oriented thoughts and feelings while accepting being LGB as a positive stage of being (Browning, Reynolds, & Dworkin, 1991; Kus, 1990; McGregor et al., 2001; Ridge, Plummer, & Peasley, 2006). The process of forming an LGB identity or “coming out” is a challenging process as it involves adopting a non-traditional sexual identity, restructuring one’s self-concept, and changing one’s relationship with society (Reynolds & Hanjorgiris, 2000; Ridge, Plummer, & Peasley, 2006).

Coming out for bisexual individuals is a “more ambiguous status” (Hunter, 2007, p. 53) as it is complicated by marginalization from both the straight and gay communities. This marginalization usually includes same-gender oriented friends urging bisexual individuals to adopt a gay lifestyle and heterosexually-oriented friends pressuring them to conform to heterosexual standards (Smiley, 1997). Although it is common for research on bisexual individuals to be lumped with lesbians and gay men (Hoang, Holloway, & Mendoza, 2011), Knous (2005) proposed a series of steps that individuals who identify as bisexual might take in disclosing and ultimately embracing their sexual identity. The first step is to be attracted or to participate in sexual activity with someone of either gender. The second step is to become labeled as bisexual either by themselves or by society. The third step is to be participatory in the bisexual community through personal or group pride. Bisexual individuals still experience stigma similar to their lesbian, gay, or heterosexual counterparts (Knous, 2005), and respond in similar ways: they might “pass” as either gay or straight, an act intended to hide one’s same-gender attractions (Herek, 1996); disclose their bisexual identity; or join support groups to fight the stigma (Knous, 2005).

Multiple researchers have described average chronological ages at which experiences related to coming out occur, which were summarized by Hunter (2007). Lesbians and bisexual women first experience awareness of same-gender attraction between the ages of ten and eleven years; gay and bisexual males between the ages of nine and thirteen years. Gay male youths on average experience their first sexual experiences a few years later between the ages of thirteen and sixteen years, while lesbian youths experiment around twenty years of age. First disclosures of sexual orientation happen between the ages of sixteen and nineteen for lesbian youths, and sixteen and twenty for gay male youths. Regardless of the age of disclosure, negative responses to being lesbian, gay, or bisexual still occur, and this “tempers the motivation of persons…in terms of making disclosures” (Hunter, 2007, p. 84). This may explain the three main patterns of sexual identity in individuals who are moving towards identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Braun, 2006). These patterns include consistently identifying as gay or lesbian, transitioning from bisexual to gay or lesbian, and consistently identifying as bisexual. Youths who were engaged in transitional identities continued to change their behavior and orientation to match their new identity. The process of acceptance of one’s sexual identity, committing to that identity, and integrating that identity into one’s life is something that does not end after adolescence, but continues into adulthood (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Braun, 2006).

The process of coming out could be a major source of stress for LGB individuals (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007). Some disclosures could cause harm in the lives of LGB individuals such as family crisis, dismissal from the household, loss of custody of children, loss of friends, or mistreatment in the workplace (Hunter, 2007; Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003). Yet, not coming out to others means LGB individuals must maintain personal, emotional, and social distance from those to whom they remain closeted in order to “protect the secrecy” of their “core identity” (Brown, 1988, p. 67).

A number of studies have explored the unique challenges associated with the coming out process for LGB individuals. A study by Flowers and Buston (2001) investigated “passing” as heterosexual, or assuming the identity of a heterosexual individual while hiding behaviors associated with an LGBT identity. In their study, Flowers and Buston examined the retrospective accounts of gay identity development for 20 gay men. Living a lie was identified as a common theme in their interviews such that many men continued to assume a heterosexual identity as a response to a non-accepting homophobic society. This lie was not something that was simply stated; rather, it had to be created and maintained “all the time” (p. 58, Flowers & Buston), and only temporarily eased the participants’ feelings of isolation and identity confusion (Flowers & Buston). Shapiro, Rios, & Stewart (2010) support the findings of Flowers and Buston. In this study that explored narrative accounts of sexual minority identity development among lesbians, cultural norms that failed to acknowledge the existence of non-normative sexual identities were identified and discussed. Such neglect of LGB identities required personal silence on the part of the respondents, which helped them avoid the negative consequences of coming out such as feelings of danger and discomfort as well as punishment.

Paul and Frieden (2008) examined the process of integration of gay identity and self-acceptance among gay men. Participants described societal homophobia and heterosexism as “powerful barriers” to self-acceptance, and validation and acceptance from others as helpful supports in the acceptance of themselves. Respondents indicated that they felt emotional pain or crisis when they began to develop a same-gender sexual identity and received negative messages about that identity. They feared that loved ones would not be accepting, and often denied that they were gay, both to themselves and to others.

A study by Rowen and Malcolm (2002) examined internalized homophobia and its relationship to sexual minority identity formation, self-esteem, and self-concept among 86 gay men. Results indicated that higher levels of internalized homophobia were associated in less developed gay male identities. In addition, gay men who felt more uncomfortable with their sexual orientations were more likely to experience guilt over their same-gender sexual behavior. Internalized homophobia also was found to be related to lower levels of self-esteem and self-concept in terms of physical appearance and emotional stability.

There are a diverse range of personal variables such as “personality characteristics, overall psychological health, religious beliefs, and negative or traumatic experiences regarding one’s sexual orientation” (Hunter, 2007, p. 94) that impact to whom LGB individuals disclose their same-gender sexual orientation. Some same-gender oriented individuals are closeted entirely and hide their sexual orientations from others for fear of their reactions (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007). Others will only come out to selected people (e.g., friends, family, colleagues, teachers, medical providers) rather than everyone at once. Several will come out completely and become very involved in the LGB community by attending LGB events and venues.

In general, disclosures are most often first made to friends of LGB people who are considered to be somewhat affirming of one’s same-gender sexual orientation (Hunter, 2007). According to Cain (1991), coming out to friends can bring two friends closer together, confirm an already close relationship, or cause a strain between previously close friends. Results from a study by D’Augelli and Hershberger (2002) revealed that 73% of lesbian and gay youths first told a friend about their same-gender sexual attractions. Other research suggested that bisexual men and women are also more likely to disclose to their friends than to family members and work colleagues (Hunter, 2007). These friends are usually across sexual identities and often with individuals who are heterosexual, and less with other bisexuals (Galupo, 2006).

Regardless of the outcome, the notion that disclosure to friends differs from disclosure to family members allows for LGB individuals to “select friends who are supportive or drop those unlikely to accept the revelation, something they cannot do in their parental or sibling relationships” (Cain, 1991, p. 349). LGB individuals do not always disclose their LGB sexual orientations to family members for fear of consequences such as “…anything from a dismissal of their feelings to an actual dismissal from the household” (Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001, p. 104). Disclosures to parents elicit much anxiety for LGB individuals as there are limited ways to predict how parents will respond (Hunter, 2007). Many LGB individuals fear losing familial support after disclosing to family members (Carpineto et. al, 2008; D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2005). According to Shapiro, Rios, & Stewart (2010), when LGB individuals have identified the family as a source of conflict, these individuals considered their parental figures to be unsupportive of their sexual identity. This conflict leads to an increase in tension within the family. According to Savin-Williams and Ream (2003), 90% of college men reported that coming out to their parents was a “somewhat” to “extremely” challenging event for them (p. 429).

Siblings have been described as more accepting of their LGB sibling’s disclosure, and if there is rejection it is usually less stressful than rejection by the parents (Cain, 1991). Lesbian wives do not often disclose to their husbands for fear of consequences (i.e., violence, custody battles), but men who come out as bisexual following their marriage to a woman tell her soon after he accepts his bisexual identity (Hunter, 2007). No data on gay men and their disclosure to their wives could be located. It also is not uncommon for LGB parents to keep their same-gender sexual orientations from their children for fear of losing custody or inflicting harm on their children (Hunter, 2007).

There are positives and negatives to coming out at work and to work colleagues (Hunter, 2007), and therefore there are varying levels of disclosure among LGB individuals. Research suggests that LGB individuals who are more open at work experience higher levels of job satisfaction and commitment to the workplace (Day & Shoenrade, 1997; Griffith & Hebl, 2002; King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008). Some LGB individuals may feel “honest, empowered and connected” after disclosure at work, and able to speak more freely about their personal lives and romantic relationships (Hunter, 2007, p. 127). Organizations that have written non-discrimination policies, are actively affirmative, and offer trainings that incorporate LGB issues usually impact whether lesbian and gay individuals come out in the workplace (Griffith & Hebl, 2002). It is unfortunate, however, that there is little legal protection for LGB individuals based on sexual orientation in most workplaces (Hunter, 2007). The possible harm (i.e., ridicule, ostracism, job loss) of disclosing at work without legal protection, and in some cases even with legal protection, causes many LGB individuals to stay closeted at work. Although keeping one’s LGB sexual orientation a secret might create fewer problems with regard to stigma, discrimination, and discreditability, living “a double life” can be personally and professionally “costly” (Hunter, 2007, p. 126). Hunter further summarized the limited professional literature on outness in the workplace and reported that more than two-thirds of lesbian and gay individuals think coming out in the workplace would create problems and challenges for them, while one-third believed disclosure would hurt their career progression (i.e., not being hired, not being promoted, not receiving personal or professional support). Fears of and personal experiences with harassment and heterosexism in the workplace also could negatively impact one’s psychological and physical well-being and thus one’s decision to disclose to work colleagues.

A major study based on the utilization of The National Lesbian Health Care Survey (NLHCS; Bradford, Ryan, & Rothblum, 1993) examined the degrees of outness and to whom disclosures were made for a national sample of 1,925 lesbians. The results of this study support the aforementioned identification of whom LGB individuals come out to more often as they move through the process of forming a sexual minority identity. Researchers found that although the majority of lesbians (88%) were out to all gay and lesbian individuals who they knew, much smaller numbers were out to all family members (27%), heterosexual friends (28%), and co-workers (17%). Furthermore, many participants reported not coming out to any family members (19%) or co-workers (29%). Correlations between degree of outness and fears as a lesbian were also analyzed and results showed a negative relationship such that lesbians who were less out to family, heterosexual friends, and co-workers had more fear of exposure as a lesbian. Correlations were strongest among outness to heterosexual friends and co-workers. No other studies that specifically examined the relationship between level of outness and internalized homophobia could be located. Therefore, this important relationship remains underexplored.

In summary, LGB individuals have been described as an at-risk group based on the high level of homophobia on both societal and individual levels. Such experiences with homophobia impact the way LGB individuals view themselves, particularly how they define their sexual minority identities which have been historically marginalized and stigmatized. Consequently, negative views of self result from the internalization of society’s negative attitudes towards LGB individuals. Internalized homophobia has been documented as a potential disruption to the coming out process as it impacts an LGB individual’s decision to be closeted completely, come out to selected individuals, or come out to all (Cabaj, 1997). Disclosure or non-disclosure to family, friends, and colleagues and how it is impacted by internalized homophobia warrants attention from researchers as it has significant implications in the lives of LGB individuals.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the present study was to gain a better understanding of the relationship between levels of outness to family, friends and colleagues and internalized homophobia. Conducting research on risk factors that negatively impact the coming out process, such as internalized homophobia, will generate knowledge that will help reduce the stress unique to LGB individuals. Such research also will increase the provision of quality and effective support to cope with stress for this historically underserved population group (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007).

We hypothesized that internalized homophobia would predict whether one comes out to all family (nuclear and extended family), friends, and colleagues. Internalized homophobia and concerns about coming out contributes to an LGB individual’s reluctance to enter the ‘scene’ or culture which is related to their sexual identity (Ridge, Plummer, & Peasley, 2006). In fact, internalized homophobia has prevented some LGB individuals from never finding their true selves, creating a further disconnection from their true identities. Based on this finding as well as others, we propose that LGB individuals with high levels of internalized homophobia would be less likely to come out as LGB to all family (nuclear and extended family), friends and colleagues. If issues related to internalized homophobia, a well-documented risk factor for stress among LGB individuals, are addressed, improvement in the mental health and overall quality of life for LGB individuals can occur (Wagner et al., 1996).

Method

Participants

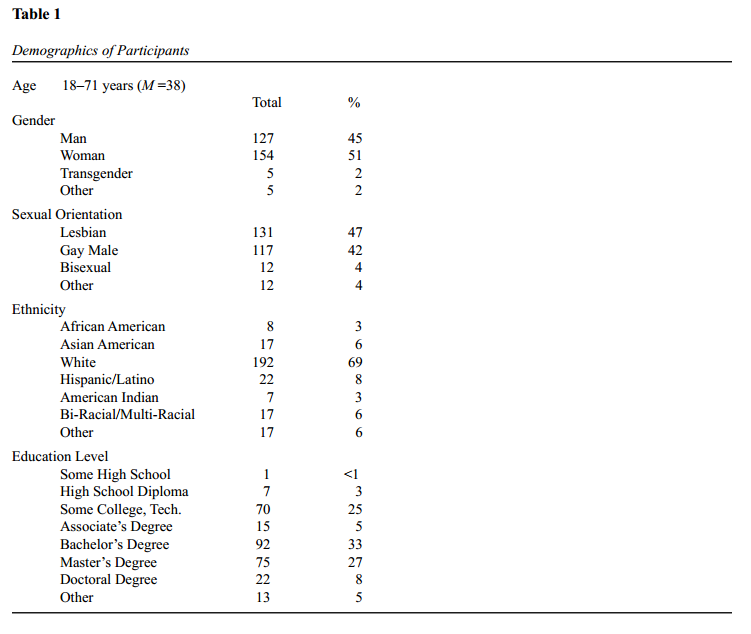

Two hundred ninety individuals between the ages of 18 and 71 responded to our study. Forty-seven percent (n = 131) of respondents identified as lesbian, 42% (n = 117) as gay, and 4% (n = 12) as bisexual. More than half of the respondents identified their gender identity as woman (51%, n = 154), 45% (n=127) as man, 2% (n = 5) as transgender, and 2% (n = 5) as “other.” Seventy-three percent (n = 204) had an associate’s degree or higher, and 69% (n=192) identified as White (see Table 1 for complete demographics). Due to the small number of transgender respondents, we did not examine their experiences by gender identity. We do recognize, however, the unique interaction between gender identity and sexual identity, and encourage future research in this area.

Materials

Levels of Outness. The questions used in this study that assessed level of outness of participants were adapted with permission from a survey developed by Rankin (2003). These questions are part of a larger campus climate survey that is used nationally to assess campus climate for community members. This set of questions showed high internal consistency (α = .80). Using a varimax rotation, items load as one factor and account for 65% of the variance.

Internalized Homophobia Scale (IHP; Martin & Dean, 1987). The Internalized Homophobia Scale is a 9-item measure adapted for self-report. Previous research has indicated that the self-administered version of the IHP scale has acceptable internal consistency and correlated as expected with relevant measures (Herek & Glunt, 1995). Items are administered with a 5-point response scale, ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly. Reliability coefficients for this scale are typically higher for men (α = .83) then women (α = .71).

Procedure

An online survey was created through PsychData, a Web-based company that conducts Internet-based research in the social sciences. Participants were invited through email advertisements to general and multicultural LGBT list-servs. Personal networks also were utilized. Participants were made aware of the intentions of the survey and the topics they would encounter. Participation was anonymous and all respondents reviewed and gave informed consent before initiating the study. (Appropriate IRB approval was obtained).

Results

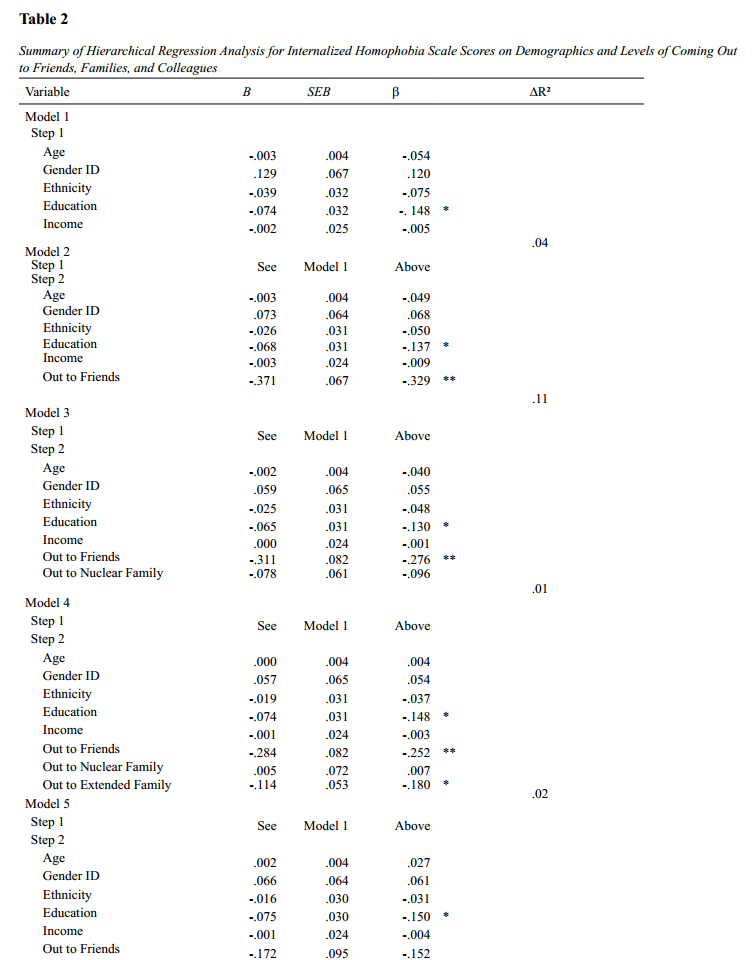

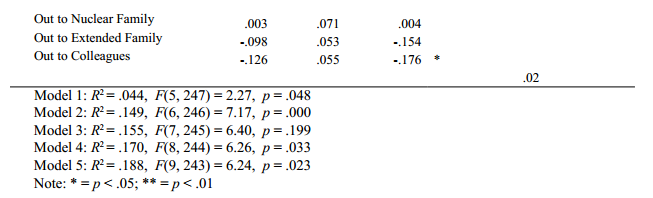

A set of regression procedures were conducted to examine how “coming out” to friends, family, and colleagues predicted scores on the Internalized Homophobia Scale (IHP). Table 2 shows the complete regression summaries. Model 1 regressed demographic variables: age, self-identified gender, ethnicity, education level and reported income. This model accounted for 4% of the overall variance with education level contributing most to the prediction of IHP scores (β = -.15, p < .05). This model was used in each of the following hierarchical models as a first step to control for demographics to examine the prediction value of each “coming out” variable.

Model 2 emerged as a significant model. Coming “out to friends” was added as a second step to the model and accounted for an additional 11% of the variance after controlling for demographics. According to the standardized regression coefficients, this variable provided a significant contribution to the prediction of IHP scores (see Table 2). Model 3 did not emerge as a significant model. By including coming “out to nuclear family” only an addition 1% of the total variance was accounted for. Within the third model, coming “out to friends” remained the largest contributor to the prediction of internalized homophobia (β = -.28, p < .05).

Model 4 and Model 5 emerged as significant models. In Model 4, the second step added coming “out to extended family” and contributed 2% to the total variance. Standardized regression coefficients indicated coming “out to friends” and “out to extended family members” were the strongest contributors to the model. By adding “out to colleagues” to the second step of the fifth model, an additional 2% of the variance was accounted for beyond demographics. “Out to colleagues” contributed the most to the predication of internalized homophobia beyond demographic differences, coming out to friends, coming out to nuclear family, and coming out to extended family (β = -.18, p < .05). Model 5 accounted for almost 19% of the total variance.

Discussion

The findings from our study suggest internalized homophobia impacts whether one is out to friends, colleagues, and extended family, but not to nuclear family. These findings are surprising as we hypothesized internalized homophobia would impact whether one is out to all family members (nuclear and extended), friends, and colleagues. Specifically, we hypothesized that higher internalized homophobia would lessen the likelihood that LGB individuals disclose as lesbian, gay, or bisexual to all family (nuclear and extended), friends, and colleagues. This assumption was based on the professional literature that underscored the fact that experiences in an anti-gay society can lead LGB individuals to internalize prejudicial messages and have negative views of self, and the potential consequences of coming out to family (family crisis), friends (disconnection and loss of friends), and work colleagues (dismissal and mistreatment; Hunter, 2007; Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003).

Education level also was a strong predictor of internalized homophobia for the sample in this study. Education level may be influential because individuals who are more “in the know” may accept that internalized homophobia is a barrier to self-acceptance and therefore an issue worth addressing and resolving. Further, coming out to friends and colleagues contributed strongly to internalized homophobia which may be a result of the experiences of LGB individuals in an anti-gay society and the possibility that friends and colleagues represent non-affirming members of our society. Therefore, the greater the discomfort with one’s same gender sexual identity, the less likely a LGB individual will come out to friends or co-workers for fear of negative consequences.

Although Hunter (2007) posited that LGB people most often come out to friends first, our study underscores a unique relationship between internalized homophobia and coming out to friends in that respondents with higher internalized homophobia were less out to friends. Findings from the National Lesbian Health Care Survey (NLHCS; Bradford, Ryan, & Rothblum, 1993) support this finding from our study. Correlations from the NLHCS suggest lesbians with higher internalized homophobia feared exposure as a lesbian to heterosexual friends. Furthermore, 88% of lesbians from the NLHCS were out to other LGB individuals, but only 28% were out to heterosexual friends. Perhaps respondents in our study who had higher internalized homophobia had similar fears regarding disclosure to heterosexual friends, particularly those who were non-affirming of LGB sexual identities. Furthermore, based on the results of our study and the professional literature, it is possible to assert that respondents from our study who had lower internalized homophobia were more comfortable coming out to friends who were affirming of LGB sexual identities.

Research suggests that LGB individuals who are more open at work experience higher levels of job satisfaction, commitment to the workplace, the fostering of a healthy identity, and the encouragement of employers to promote a diverse workplace (Day & Shoenrade, 1997; Griffith & Hebl, 2002; King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008). While there are positive aspects of research surrounding coming out at work, research also suggests that more than two-thirds of LGB people think coming out to the workplace would create problems (i.e., not being hired, not being promoted, not receiving support and mentorship necessary for professional development, or loss of job; Hunter, 2007). The context in which an individual comes out at work is much more important than the situational factors which lead them to come out (King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008). Consequently, many LGB individuals stay closeted at work in anticipation of rejection, which is often based on a lack of legal protection or personal experiences with an anti-gay organizational climate.

Our study uncovered a strong relationship between internalized homophobia and level of outness at work. In fact, outness to colleagues was the largest predictor of internalized homophobia above and beyond all other variables analyzed in this study. Based on this finding, we defend previously cited research that LGB individuals are more likely to be out and experience less internalized homophobia when they have had positive experiences with coming out in the past, or when their organizations are gay-friendly, include written non-discrimination policies and advocate on behalf of LGB people (i.e., offer trainings and workshops that incorporate LGB issues; Griffith & Hebl, 2002). Friskopp and Silverstein (1995) concur with our findings by suggesting those who disclosed at work were not only more comfortable with their sexual identity, but also had many previous disclosures with heterosexual friends and relatives. In the same respect, LGB individuals who enter and remain in a workplace where heterosexism and homophobia are pervasive may never come out to co-workers or may be very selective about to whom they come out (Hunter, 2007). They might decide to pass to divide their work life and personal life, and avoid discrimination at all costs (DeJordy, 2008). Passing, while helpful in the organizational environment, can be harmful to the individual because it reduces an individual’s authenticity of one’s behavior, lowers one’s self-esteem, and denies or suppresses an individual’s LGB identity.

Results from the NLHCS (Bradford, Ryan, & Rothblum, 1993) support Hunter (2007) and our research: lesbians who were less out to co-workers had more fear of exposure as lesbian. For some LGB individuals, “just the thought of disclosure at work typically creates considerable anxiety” (Hunter, 2007, p. 124). This might be true for the participants in our study.

Finally, our hypothesis that internalized homophobia will predict outness to all family members, including nuclear and extended, was partially supported by our results. In particular, internalized homophobia was not a predictor of outness to nuclear family, but was a predictor of outness to extended family.

The fact that internalized homophobia did not predict outness to nuclear family was surprising considering the high degree of difficulty and anxiety associated with coming out to parents, the anticipated rejection by the nuclear family, and the fact that many LGB individuals remain closeted to family members indefinitely or until later in life (Hunter, 2007). Paul and Frieden (2008) contend that negative social messages about LGB sexual identities, particularly those made by family, friends, and religious organizations, increases the challenge of self-acceptance as LGB. With a lack of self-acceptance coupled with “fears related to a potential loss of relationship with specific family members,” LGB individuals might refrain from disclosing their sexual minority identities (Paul & Frieden, 2008, p. 43). It could be assumed that internalized homophobia would affect the act of coming out to family, particularly nuclear family, since “there is no predicting” how parents will react, and disclosure could cause “great turmoil in the home” (Hunter, 2007, p. 95.). Based on the aforementioned assumption, our initial hypothesis would stand. This conception, however, was not supported by the results of our study as internalized homophobia predicted outness to extended family and not nuclear family. It appears that the disclosures or lack of disclosures to nuclear family by participants in our study were not influenced by internalized homophobia. Future research that explores factors that impact disclosure to nuclear family is warranted in order to more fully understand this relationship.

Implications for Counseling

This study presents many implications for counselors. First, experiences with internalized homophobia can impact the lives of LGB individuals, particularly the coming out process.

“If one has a high level of internalized homophobia, the [coming out] process can be fraught with turmoil; however, if the individual is able to connect with supportive people who can help him or her dispel the negative attitudes of society, that state is temporary. This is an area in which counselors can aid in the process” (Matthews, 2005, p. 212).

An affirmative counselor can model a positive reaction to an LGB client’s disclosure, provide a corrective emotional experience for that client, and instill hope that positive consequences can result from coming out. This can help the client externalize his or her experiences with homophobia, and move towards self-acceptance (Matthews, 2007). Ridge, Plummer, and Peasley (2006) found that positive self-talk, writing about problems, and making more positive choices were helpful when an individual is looking to defeat feelings of internalized homophobia. On the other hand, a counselor who perpetuates messages of homophobia or heterosexism can reinforce the negative experiences of the LGB client, and thus cause more distress and heartache.

It is essential that affirmative counselors avoid heterosexism in clinical practice (i.e., review clinical paperwork for heterosexist language; decorate office to be inclusive of diverse sexual identities; advocate for a non-discrimination policy that is inclusive of sexual and gender identity). A counselor also must overcome heterosexism through self-examination and self-education where biases and prejudices are identified and dispelled (Matthews, 2007). Additionally, it is necessary for affirmative counselors to develop the knowledge and skills necessary for working with LGB clients. Continuing education opportunities such as conference workshops and graduate classes that focus on LGB issues are excellent ways to enhance a counselor’s multicultural competency to work with LGB clients. Familiarizing oneself with the LGB community (local and national) by attending LGB venues (i.e., parades, community centers, LGB bookstores), and learning key LGB figures who contributed to LGB rights through movies and literature are all important steps in becoming an affirmative counselor.

“Personal contact is the most consistently influential factor in reducing prejudice” (Hunter, 2007, p. 168). Therefore, it is invaluable for affirmative counselors, particularly heterosexual counselors, to spend time with LGB people. This will help challenge misconceptions and messages that have been learned as members of a society that perpetuates anti-gay attitudes and beliefs in many domains. Counselors must help clients explore and discover how they wish to self-identify, whether it is lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or questioning another identity. It is important to use caution in assigning the client an identity before he or she is ready to self-identity. It is beneficial for counselors to utilize sexual minority identity development models (see, for example, Cass, 1979; D’Augelli, 1994; McCarn & Fassinger, 1996; Troiden, 1979). Although these models present stages or phases that are often experienced during the coming out process, it is important to use them as guides as each LGB client is unique and may experience coming out differently.

Coming out can be a risky process, but also an empowering experience for LGB individuals (Matthews, 2007). Consequently, as a counselor, it is important to consider the potential dangers and benefits of disclosing to various individuals in the LGB client’s life. A LGB client might decide not to disclose to a particular individual because the negative consequences outweigh the positives. Counselors should support the decisions made by clients, and always ensure their personal safety (Hunter, 2007). Although there might be consequences as a result of disclosure, there will likely be long-term gains in self-acceptance and overall psychological health for LGB individuals.

It also is very important for an LGB individual to establish a connection to the LGBT community (Matthews, 2007). As a counselor, it is vital to be able to promote exposure to and interaction with positive elements of the LGB community. There are a number of online options such as support groups, chat rooms, and list-servs. Community options include LGBT community centers, support groups at counseling centers, and LGBT-sponsored events. Counselors should be familiar with these resources and prepared ahead of the counseling session to share them with a LGB client. Caution should be used in identifying resources to ensure they are safe and healthy avenues for support.

Limitations and Areas for Future Research

A possible limitation of this research is that it represents a one-time measurement of self-reported data. Such complex perceptions of being closeted and the corresponding feelings of internalized homophobia may be viewed as a dynamic process subject to change over time and experiences. Moradi, Mohr, Worthington, and Fassinger (2009) suggest using experimental, repeated measures designs, and longitudinal designs to best determine causal and or developmental hypotheses regarding sexual minority research areas and would benefit research such as this one. Future research will look toward long-term methods of measuring levels of outness and corresponding feelings of internalized homophobia over time. Additional future research should focus on homophobia and heterosexism in the workplace which, according to a report by the Human Rights Campaign (2001) “occurred in every area of the country, happened in a range of workplaces, and affected employees at all levels” (Smith & Ingram, 2004, p. 59). Although anti-LGB discrimination in the workplace is pervasive in our society, this topic remains under-explored. Finally, best practices to reduce the negative effects of internalized homophobia should be examined. Although internalized homophobia is a strong influential factor to coming out, the exploration of additional risk factors is essential in gaining a stronger understanding of sexual minority identity development.

References

Bobbe, J. (2002). Treatment with lesbian alcoholics: Healing shame and internalized homophobia for ongoing sobriety. Health and Social Work, 27(3), 218–222.

Bradford, J., Ryan, C., & Rothblum, E. (1994). National Lesbian Health Care Survey: Implications for mental health care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(2), 228–242.

Brown, L. (1989). Lesbians, gay men, and their families: Common clinical issues. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 1(1), 65–77.

Browning, C., Reynolds, A. L., & Dworkin, S. H. (1991). Affirmative psychotherapy for lesbian women. The Counseling Psychologist, 19(2), 177–196.

Cabaj, R. P. (2000). Substance abuse, internalized homophobia, and gay men and lesbians: Psychodynamic issues and clinical implications. In J. R. Guss & J. Drescher (Eds.), Addictions in the gay and lesbian community (pp. 5–24). Binghamton, NY: Haworth.

Cain, R. (1991). Stigma management and gay identity development. Social Work, 36(1), 67–73.

Carpineto, J., Kubicek, K., Weiss, G., Iverson, E., & Kipke, M. D. (2008). Young men’s perspectives on family support and disclosures of same-sex attraction. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 2(1), 53–80.

Cass, V. (1979) Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4(3), 219–235.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2001). A provider’s introduction to substance abuse treatment for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 01-3498. Rockville, MD: CSAT.

D’Augelli, A. R. (1994). Identity development and sexual orientation: Toward a model of lesbian, gay, and bisexual development. In E. W. Trickett, R. J. Watts & D. Birman (Eds.), Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

D’Augelli, A. R., Grossman, A, H., & Starks, M. T. (2005). Parents’ awareness of lesbian, gay, bisexual youths’ sexual orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family Therapy, 67, 474–482.

D’Augelli, D. & Hershberger, S. L. (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 148–167.

Davies, D. (1996). Homophobia and heterosexism. In D. Davies & C. Neal (Eds.), Pink therapy: A guide for counselors and therapists working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients (pp. 41–65). Buckingham, England: Open University Press.

Day, N., & Schoenrade, P. (1997). Staying in the closet versus coming out: Relationships between communication about sexual orientation and work attitudes. Personnel Psychology, 50(1), 147–163.

DeJordy, R. (2008). Just passing through – stigma, passing, and identity decoupling in the work place. Group and Organization Management, 33(5), 504–531.

Diamond, D. L., & Wilsnack, S. C. (1978) Alcohol abuse among lesbians: A descriptive study. Journal of Homosexuality, 4(2), 123–142.

Flowers P., & Buston K. (2001). “I was terrified of being different”: Exploring gay men’s accounts of growing-up in a heterosexist society. Journal of Adolescence, 24(1), 51–65.

Friskopp, A., & Silverstein S. (1995). Straight jobs, Ggay lives: Gay and lesbian professionals, the Harvard Business School, and the American workplace. New York, NY: Scribner.

Galupo, M.P. (2006). Sexism, heterosexism, and biphobia: The framing of bisexual women’s friendships. Journal of Bisexuality, 6(3), 35–45.

Griffith, K. H., & Hebl, M. R. (2002). The disclosure dilemma for gay men and lesbians: “Coming out” at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1191–1199.

Herek, G. M. (1996). Heterosexism and homophobia. In R. P. Cabaj & T. S. Stein (Eds.), Textbook of homosexuality and mental health (pp. 101–113). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Herek, G. M., & Glunt, E. K. (1995). Identity and community among gay and bisexual men in the AIDS era: Preliminary findings from the Sacramento Men’s Health Study. In G. M. Herek & B. Greene (Eds.) AIDS, identity, and community: The HIV epidemic and lesbians and gay men (pp. 55–84). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hoang, M., Holloway, J., & Mendoza, R. H. (2011). An empirical study into the relationship between bisexual identity congruence, internalized biphobia and infidelity among bisexual women. Journal of Bisexuality, 11, 23–38.

Hunter, S. (2007). Coming out and disclosures: LGBT persons across the life span. Binghamton, New York, NY: Haworth.

Iwasaki, Y., & Ristock, J. (2007). The nature of stress experienced by lesbians and gay men. Anxiety, Stress and Coping: An International Journal, 20(20), 299–319.

King, E. B., Reilly, C., & Hebl, M. (2008). The best of times, the worst of times – exploring dual perspectives of “coming out” in the workplace. Group and Organization Management, 33(5), 566–601.

Knous, H. M. (2005). The coming out experience for bisexuals: Identity formation and stigma management. Journal of Bisexuality, 5(4), 37–59.

Kus, R. J. (1988). Alcoholism and non-acceptance of gay self: The critical link. Journal of Homosexuality, 15(1-2), 25–41.

Lewis, C. E., Saghir, M. T., & Robins, E. (1982). Drinking patterns in homosexual and heterosexual women. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 43(7), 277–279.

McCarn, S. R., & Fassinger, R. E. (1996). Re-visioning sexual minority identity formation: A new model of lesbian identity and its implications for counseling and research. The Counseling Psychologist, 24(3), 508–534.

McGregor, B., Carver, C., Antoni, M., Weiss, S., Yount, S., & Ironson, G. (2001). Distress and internalized homophobia among lesbian women treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(1), 1–9.

Martin, J., & Dean, L. (1987). Ego-dystonic Homosexuality Scale. School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Matthews, C. R. (2007). Affirmative lesbian, gay, and bisexual counseling with all clients. In K. J. Bieschke, R. M. Perez, & K. A. DeBord (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients, (2nd ed., pp. 201–219). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Moradi, B., Mohr, J., Worthington, R. L., & Fassinger, R. (Guest Eds.) (2009). Special Issue: Advances in research with sexual minority people. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 23–43.

Neisen, J. H. (1990). Heterosexism: Redefining homophobia for the 1990’s. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 1(3), 21–35.

Paul, P., & Frieden, G. (2008). The lived experience of gay identity development: A phenomenological study. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 2(1), 25–52.

Rankin, S. (2003). Campus climate for sexual minorities: A national perspective. New York, NY: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute.

Rankin, S., Weber, G., Blumenfeld, W., & Frazer, S. (2010). 2010 State of Higher Education for LGBT People. Charlotte, NC: Campus Pride.

Reynolds, A. L., & Hanjorgiris, W. F. (2000). Coming out: Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identity development. In R. M. Perez, K. A. DeBord, & K. J. Bieschke (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients, (pp. 35–55). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ridge, D., Plummer, D., & Peasley, D,. (2006). Remaking the masculine self and coping in the liminal world of the gay ‘scene’. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 8(6), 501–514.

Rosario, M., Schrimshaw, E. W., Hunter, J., & Braun, L. (2006). Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: consistency and change over time. Journal of Sex Research, 43(1), 46–58.

Ross, M. W., & Rosser, S. B. (1996). Measurement and correlates of internalized homophobia: A factor analytic study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52(1), 15–20.

Rotheram-Borus, M. J., & Langabeer, K. A. (2001). Developmental trajectories of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. In A. D’Augelli, & C. Patterson (Eds.), Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities and youth: Psychological perspectives (pp. 97–128). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rowen, C., & Malcolm, J. (2002). Correlates of internalized homophobia and homosexual identity formation in a sample of gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(2), 77–92.

Saghir, M. T., & Robins, E. (1973). Male and female homosexuality: A comprehensive investigation. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

Savin-Williams, R. C., & Ream, G. L. (2003). Sex variations in the disclosure to parents of same-sex attractions. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 429–438.

Selvidge, M. (2000). The relationship of sexist events, heterosexist events, self-concealment and self-monitoring to psychological well-being in lesbian and bisexual women. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee.

Shapiro, D.N., Rios, D., & Stewart, A.J. (2010). Conceptualizing lesbian sexual identity development: narrative accounts of socializing structures and individual decisions and actions. Feminism & Psychology, 20(4), 491–510.

Smiley, E. B. (1997). Counseling bisexual clients. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 19, 373–382.

Smith, N. G., & Ingram, K. M. (2004). Workplace heterosexism and adjustment among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: The role of unsupportive social interactions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 57–67.

Spencer, S. M., & Patrick, J. H. (2009). Social support and personal mastery as protective resources during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 191–198.

Stall, R., & Wiley, J. (1988). A comparison of alcohol and drug use patterns of homosexual and heterosexual men: The San Francisco Men’s Health Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 22(1-2), 63–73.

Stein, T. S., & Cabaj, R. P. (1996). Psychotherapy and gay men. In R. P. Cabaj & T. S. Stein (Eds.), Textbook of homosexuality and mental health (pp. 413–432). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Troiden, R. (1979) Becoming homosexual: A model of gay identity acquisition. Psychiatry, 42(4), 362–373.

Wagner, G., Brondolo, E., & Rabkin, J. (1996). Internalized homophobia in a sample of HIV+ gay men, and its relationship to psychological distress, coping, and illness progression. Journal of Homosexuality, 32(2), 91–106.

Weber, G. N. (2008). Using to numb the pain. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 30(1), 31–48.

Genevieve Weber-Gilmore and Sage Rose are Assistant Professors at Hofstra University. Rebecca Rubinstein is a graduate student in Rehabilitation and Mental Health Counseling at Hofstra University. Correspondence can be addressed to Genevieve Weber-Gilmore, Hofstra University, Department of Counseling and Mental Health Professions, Hempstead, NY, 11549-1000, genevieve.weber@hofstra.edu.