Gerta Bardhoshi, Amy Schweinle, Kelly Duncan

This mixed-methods study investigated the relationship between burnout and performing noncounseling duties among a national sample of professional school counselors, while identifying school factors that could attenuate this relationship. Results of regression analyses indicate that performing noncounseling duties significantly predicted burnout (e.g., exhaustion, negative work environment and deterioration in personal life), and that school factors such as caseload, Adequate Yearly Progress status and level of principal support significantly added to the prediction of burnout over and above noncounseling duties. Moderation tests revealed that Adequate Yearly Progress and caseload moderated the effect of noncounseling duties as related to several burnout dimensions. Participants related their burnout experience to emotional exhaustion, reduced effectiveness, performing noncounseling duties, job dissatisfaction and other school factors. Participants conceptualized noncounseling duties in terms of adverse effects and as a reality of the job, while also reframing them within the context of being a school counselor.

Keywords: burnout, noncounseling duties, professional school counselors, mixed methods, job dissatisfaction

Although the term burnout was first coined by Freudenberger (1974) to describe a clinical syndrome encompassing symptoms of job-related stress, it is generally accepted that the work of Maslach and colleagues has served as the foundation of the empirical study of burnout as a psychological phenomenon. Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter (2001) defined burnout as a prolonged exposure to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job. The primary focus of burnout studies remains within the occupational sector of human services and education, where empathy demands are high and the emotional challenges of working intensively with other people in either a caregiving or teaching role are considerable (Maslach et al., 2001). Burnout is defined by three core dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

Emotional exhaustion is a key aspect of the burnout syndrome. It is the most obvious manifestation of the syndrome (Maslach et al., 2001) and a reaction to increasing job demands that produce a sense of overload and exhaust one’s capacity to maintain involvement with clients (Lee & Ashforth, 1996). Feeling unable to respond to the needs of the client, one experiences purposeful emotional and cognitive distancing from one’s work. This effort to establish distance between oneself and the client is defined as depersonalization. Reduced personal accomplishment describes the eroded sense of effectiveness that burned-out individuals experience (Maslach et al., 2001).

According to the job demands–resources model, one of the most cited models in burnout literature, burnout occurs in two phases: first, extreme job demands lead to sustained effort and eventually exhaustion; second, a lack of resources to deal with those demands further leads to withdrawal and eventual disengagement from work (Demerouti, Nachreiner, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2001). Professional school counseling is a profession in which emotional empathy is a requirement, and the qualitative and quantitative job demands are high. Stressors linked to burnout (e.g., high workload, negative work environment) have effects that may persist even after exposure to the stressor has ended, leading to negative impact on daily well-being (Repetti, 1993). In those jobs in which high demands exist simultaneously with limited job resources, both exhaustion and disengagement are evident (Bakker, Demerouti, & Euwema, 2005; Demerouti et al., 2001). With organizational factors accounting for the greatest degree of variance in burnout studies (Lee & Ashforth, 1996), robustly exploring factors unique to the profession of school counseling is a key to understanding the phenomenon of burnout in school counselors.

Variables Related to Burnout in School Counselors

School counseling literature has repeatedly drawn attention to organizational variables that are problematic for the profession and might provide insight into the burnout phenomenon. School counselors face rising job demands (Cunningham & Sandhu, 2000; Gysbers, Lapan, & Blair, 1999; Herr, 2001) that are often difficult to balance (Bryant & Constantine, 2006), leading them to feel overwhelmed in their work environment (Kendrick, Chandler, & Hatcher, 1994; Kolodinsky, Draves, Schroder, Lindsey, and Zlatev, 2009; Lambie & Williamson, 2004), and to lack the time to provide direct services to students (Gysbers & Henderson, 2000). In addition to job overload, school counselors also are expected to perform a high number of conflicting job responsibilities, leading to role conflict (Coll & Freeman, 1997).

Role conflict is indeed related to burnout in school counselors (Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). Paperwork and other noncounseling duties interfere with the roles of school counselors and are a source of job stress and dissatisfaction (Burnham & Jackson, 2000; Kolodinsky et al., 2009). Authors have pointed out that school counselors who perform noncounseling duties labeled as inappropriate rate them as highly demanding (McCarthy et al., 2010), experience less satisfaction with and commitment to their jobs (Baggerly & Osborn, 2006), and cite these duties as a source of stress and role conflict (Kendrick et al., 1994).

Another factor implicated in school counselor overload is a large caseload (Sears & Navin, 1983). The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommends a 250:1 ratio of students to counselors; however, the national average of students per counselor is closer to 471 (ASCA, 2014). High counselor-to-student ratios further decrease the already limited time school counselors have available for providing direct counseling services to students (Astramovich & Holden, 2002). Feldstein (2000) reported that larger caseloads correlate with higher burnout in school counselors, a finding also echoed in Gunduz’s (2012) study of school counselors in Turkey.

School counseling today continues to be affected by initiatives and educational reforms (Herr, 2001), with school counselors facing the expectation of involvement in both educational and mental health initiatives (Paisley & McMahon, 2001). A current example includes the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) mandate, passed in 2002, which emphasizes required testing for all students, as well as increased accountability for school staff, including school counselors, to track student progress (Erford, 2011). Despite school counselors being an essential part of the school achievement team, they were not included in the NCLB reform movement (Thompson, 2012). The consequences of not meeting annual NCLB progress targets, termed Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP), have been implicated in increased stress for school staff and have negatively impacted school climates (Paisley & McMahon, 2001; Thompson & Crank, 2010), potentially important factors to explore in relation to school counselor burnout.

A few studies also have drawn attention to the organizational support received from colleagues and supervisors in the work environment and the potential moderating effects of this variable on burnout. Perceived organizational support refers to employees’ perception of their value to the organization, as well as the support available to help them perform their work and deal effectively with stressful situations (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Bakker et al. (2005) found that, among other factors, a high-quality relationship with one’s supervisor provided a buffering effect on the impact of work overload on emotional exhaustion. Similarly, school counselors who perceive their own value to the organization as high seem to experience lower levels of job-related stress and greater levels of job satisfaction (Rayle, 2006). Lambie (2002) identified organizational support as the greatest influence on school counselor burnout levels in all three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment. Yildrim (2008) reported significant negative relationships between principal support and burnout in school counselors, while Wilkerson and Bellini (2006) further asserted that working relationships with school principals make a difference in school counselor burnout.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between burnout among professional school counselors, as measured by the Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI; Lee et al., 2007), and the assignment of noncounseling duties, as measured by the School Counselor Activity Rating Scale (SCARS; Scarborough, 2005), while also identifying other organizational factors in schools that could attenuate this relationship. We aimed to obtain different but complementary data on the same topics and included open-ended qualitative questions in the online survey in order to expand on quantitative results with qualitative data and gain a more nuanced understanding of burnout (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). Connides (1983) concluded that this combined qualitative and quantitative analysis approach is efficient for gathering baseline data from large numbers of respondents, resulting in a broader understanding of participants and phenomena. Research questions included the following:

What is the relationship between noncounseling duties, as measured by all three subscales of the SCARS (Fair Share, Clerical and Administrative), and burnout, as measured by each of the five subscales of the CBI (Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Client and Deterioration in Personal Life) among professional school counselors surveyed?

Do other school factors—specifically caseload, principal support and meeting AYP—also affect burnout, above and beyond noncounselor duties?

Can other school factors attenuate the effect of assignment of noncounselor duties on burnout?

What is the individual, unique and subjective meaning that participants ascribe to their experience of burnout and performing noncounseling duties in a school setting?

Method

Participants and Procedure

After obtaining institutional board approval, we created a randomized list of 1,000 school counselors who belonged to ASCA. The survey method followed a multiple-contact procedure suggested by Dillman (2007) regarding Internet surveys; a criterion sampling procedure embedded in the first page of the online survey ensured that all participants who progressed to the survey met the following criteria: (a) certified as a school counselor in their practicing state, and (b) working in elementary, middle and/or high school. Of the 286 counselors who responded to an e-mail survey invitation, 252 provided complete responses on the CBI, resulting in a 26% response rate (sample sizes for the specific tests may vary as a function of missing data for individual variables).

Some states offer a K–12 certification for school counselors. School counselors with this certification typically work in small schools and their assignment is the whole K–12 population; or, in the case in which counselors work in a school with multiple school counselors, their assignment might be a mix of grades from K–12. Participants in this study included school counselors with a wide range of grade-level assignment: 36.5% were K–12 school counselors, 32.9% were high school counselors, 19% were elementary school counselors and 11.5% were middle school counselors. The majority of the school counselors (41.7%) reported a rural work location, with the remaining 31% being suburban and 27.8% urban. Public school counselors made up the majority of the sample (75% public vs. 18.3% private). The sample also included charter schools (6%) and a tribal school (.4%). Although 36.5% of the participants reported caseloads of up to 250, the majority of the participants reported caseloads over the recommended ASCA numbers of 250 (32.9% had caseloads of 251–400; 30.6% had caseloads of 400+). The majority of school counselors (56%) indicated that their school had made AYP for the most recent school year, with 24.6 % indicating that their school had not made AYP, and 19.4% identifying AYP as not applicable for their particular school. School counselors’ responses also ranged in how supported they felt by their school principal—from very much so (42.9%), to quite a bit (23%), moderately (18.7%), a little bit (12.3%) and not at all (3.2%).

Women made up the majority of the sample (82.1% vs. 17.9% men). In terms of race and ethnicity, the majority identified as White (78.6%), with the next largest groups being Black and Hispanic (both 7.9%). The majority of school counselors (49.2%) selected the 0–5 range for their years of experience, with the following categories (6–10 and 11+) almost equally distributed (25% and 25.8%, respectively).

Instruments

Counselor Burnout Inventory. The CBI is a 20-item instrument designed to measure burnout in professional counselors (Lee et al., 2007). It is divided into five subscales: Exhaustion (e.g., “I feel exhausted due to my job as a counselor”), Incompetence (e.g., “I feel frustrated by my effectiveness as a counselor”), Negative Work Environment (e.g., “I feel negative energy from my supervisor”), Devaluing Client (e.g., “I am not interested in my clients and their problems”) and Deterioration in Personal Life (e.g., “I feel I have poor boundaries between work and my personal life”). Participants rate items on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never true, to 5 = always true. Scores for each of the individual subscales may range from 4–20, with total scores ranging from 20–100.

Lee et al. (2007; 2010) examined the initial validity and reliability of the CBI with two samples of counselors from a variety of specialties, including professional school counselors. Construct validity for the CBI was assessed by utilizing an exploratory factor analysis, which resulted in a five-factor solution that accounted for 66.97% of the total variance, with all goodness of fit indices also supporting an adequate fit to the data. Reported internal consistency for all five subscales by Lee et al. (2007) included alpha coefficient scores of .94 for the overall scale and .80 for Exhaustion, .81 for Incompetence, .83 for Negative Work Environment, .83 for Devaluing Client and .84 for Deterioration in Personal Life subscales. Test-retest reliability of the CBI across all five subscales was .81, indicating good reliability of this instrument over time. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of scores for the CBI were .92, well within the reported range of .88–.94.

School Counselor Activity Rating Scale. The SCARS was designed to assess the frequency with which school counselors actually perform certain activities, as well as the frequency with which they would prefer to perform those activities (Scarborough, 2005; Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008). Utilizing a verbal frequency scale (ranging from 1 = rarely do this activity, to 5 = routinely do this activity), school counselors rate their actual and preferred performance of a wide range of intervention activities (e.g., counsel students regarding personal problems, coordinate and maintain a comprehensive school counseling program) as well as other noncounseling activities. Only the Other Duties scale of the SCARS was used for this study. Participants rated their actual performance of 10 activities that fall into three subscales: Clerical (e.g., “schedule students for classes”), with scores ranging from 3–15; Fair Share (e.g., “coordinate the standardized testing program”), with scores ranging from 5–15; and Administrative (e.g., “substitute teach and/or cover for teachers at your school”), with scores ranging from 2–10.

Scarborough (2005) examined the initial validity and reliability of the SCARS with a random sample of 300 school counselors, demonstrating content and construct validity for the SCARS subscales. A separate analysis on the 10 items reflecting Other School Counseling Activities supported three factors in which noncounseling activities can be categorized: Clerical, Fair Share and Administrative. Scarborough (2005) also demonstrated convergent and discriminant construct validity. Reported Cronbach’s alphas were .84 for the Clerical subscale, .53 for the Fair Share subscale, and .43 for the Administrative subscale. Despite some subscale low reliability scores, the researchers were unable to locate any other instrument measuring noncounseling duties with published psychometric data. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the Other Duties Subscale scale was an adequate .69 and within the reported range of .43–.84.

Demographic Information. Demographic information collected included gender, ethnicity, highest degree earned, number of years as a practicing school counselor, grade-level assignment, location of school, type of school, total numbers of students in school, caseload number, total number of school counselors in school, percentage of minority students, percentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, whether the school made AYP, and perceived level of support from school principals.

Qualitative Questions. Three open-ended questions were included in the online survey to allow participants latitude in their responses (Marshall & Rossman, 1999). These questions included the following: What does burnout mean to you as a school counselor?, What does performing noncounseling duties in a school setting mean to you? and What other information would you like to add that has not been addressed in this survey?

Data Entry and Analysis

Data were imported from SurveyMonkey to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18 and examined prior to analysis. A concurrent triangulation mixed-methods design was utilized with the qualitative and quantitative data analyzed separately but integrated in the interpretation of the findings; quantitative and qualitative findings were combined into a “coherent whole” (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011, p. 214). It was hypothesized that among professional school counselors surveyed, a model containing all three of the SCARS subscales measuring noncounseling duties (Fair Share, Clerical and Administrative) would significantly predict three subscales of the CBI (Exhaustion, Negative Work Environment and Deterioration in Personal Life). In order to test this hypothesis, we conducted five separate linear, multiple-regression analyses of assignment of noncounselor duties (Clerical, Fair Share and Administrative, as measured by the SCARS) on each of the measures of burnout (Exhaustion, Incompetence, Negative Work Environment, Devaluing Clients and Deterioration in Personal Life, as measured by the CBI). We predicted that noncounselor duties would significantly predict exhaustion, negative work environment and deterioration in personal life. (Those participants who said AYP was not applicable to them were removed from this and future analyses.)

We also questioned whether school factors that could tap into job demands and resources (e.g., caseload, meeting AYP and lack of principal support) were predictive of burnout, over and above noncounselor duties. Caseload was coded as 0–250, 251–400, and over 400. Therefore, we dummy-coded this variable with the ASCA-recommended load of 0–250 as the reference group. We conducted hierarchical regressions, assessing the increase in prediction of burnout by other factors from the models with only noncounselor duties. To test the possibility that other school factors (e.g., meeting AYP, caseload, principal support) may increase or lessen (i.e., moderate) the effects of noncounseling duties on burnout, we ran a series of moderation tests (see Baron & Kenny, 1986) to arrive at a model for each measure of burnout including only the meaningful moderators. To create moderation terms, we centered the measures of noncounselor duties and other school factors about their means, and then multiplied (other school factors × noncounselor duties). For each measure of burnout, we used hierarchical regression to determine if the moderators significantly added to the prediction, over and above the main effects. We tested the addition of each moderator to the main effects model. Because this resulted in 60 tests, only the significant tests are reported in the results.

Analysis of the qualitative data was guided by a grounded theory approach, which allows the researcher to inductively move from a simple to a more nuanced understanding of a phenomenon through the identification and formulation of words, concepts and categories within the text (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Although not used to build a theory, this methodology allows for the utilization of frequency, meanings and relationships of words, concepts or categories to make meaningful inferences regarding the participants’ words (Silverman, 1999).

The first author coded qualitative responses line-by-line using etic or substantive codes, which were informed by school counseling and burnout literature. The first author then used a second level of coding: emic codes that emerged from the data, which are open codes using the participant’s own words to identify any emergent codes that departed from or supplemented burnout and school counseling literature. A constant comparative method, which compares coded segments of text with similar and different segments, was utilized to further refine the analysis. Axial codes were then used to conceptually categorize codes in order to capture larger emergent themes (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

When using qualitative methodology, researchers must be transparent as they become instruments of investigation. The first author is in her second year as a counselor educator, and was prompted to study the topic after working closely with school counselors who displayed many of the symptoms of burnout. The third author is in her 11th year as a counselor educator and has been involved in the field of school counseling for over 25 years. In addition to utilizing a subjectivity memo to guard against bias (Marshall & Rossman, 1999), we enhanced trustworthiness by having the third author audit the first author’s entire process and documents. A review of verbatim responses to determine adequate categorization of codes and themes derived by the first author provided a reliability check, and led to appropriate adjustments made by consensus. Response frequencies are included to present particularly influential codes (Driscoll, Appiah-Yeboah, Salib, & Rupert, 2007).

Results

Assignment of Noncounselor Duties and Burnout

The results of the regression analysis (see Table 1) supported the hypothesis that among professional school counselors surveyed, a model containing all three of the SCARS subscales measuring noncounseling duties (Fair Share, Clerical and Administrative) would significantly predict three subscales of the CBI (Exhaustion, Negative Work Environment and Deterioration in Personal Life). That is, noncounselor duties significantly predicted exhaustion, negative work environment and deterioration in personal life. More specifically, assignment of clerical duties was an important predictor for all three burnout subscales, and administrative duties were important for predicting negative work environment.

Table 1

Results of Regression Analyses of Noncounselor Duties Predicting Each Burnout Subscale

|

Burnout measure (DV) |

||||||||

|

Exhaustion |

Incompetence |

Negative work environment |

Devaluing client |

Deterioration in personal life |

M |

SD |

||

| R2 | 0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.06** | 0.01 | 0.08*** | |||

| MSE | 13.99 | 9.10 | 16.26 | 2.80 | 11.00 | |||

| b clerical | 0.27*** | 0.08 | 0.13† | 0.09 | 0.25*** | 9.90 | 4.22 | |

| b fair share | 0.11 | 0.02 | –0.02 | –0.10 | 0.02 | 16.26 | 4.33 | |

| b administrative | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.20 ** | –0.01 | 0.11 | 4.54 | 1.90 | |

| M | 11.96 | 9.02 | 10.16 | 5.22 | 8.50 | |||

| SD | 3.95 | 3.03 | 4.13 | 1.68 | 3.44 | |||

Note. N = 212.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; †p < .06.

Qualitative responses from participants answering the question, What does performing noncounseling duties mean to you? also echoed these results. Many participants responded to this qualitative question by listing a variety of noncounseling duties they performed at their school, which were fair share, administrative or clerical in nature. The most frequently cited noncounseling duties were testing (46), lunch duty (38), substitute teaching (31), discipline (23), scheduling (19), special education services (15) and bus duty (15). Many school counselors also described noncounseling duties as those that do not fall in the direct services category (16), or are not recommended by ASCA (10).

A major theme that emerged from the qualitative responses was that school counselors viewed performing noncounseling duties as having adverse personal and professional effects, including feeling exhausted and burned out (21), detracting from their job (36), serving as a source of stress and frustration (13), being a waste of time and resources (8) and resulting in making them feel less valued (8). One school counselor described performing noncounseling duties as follows:

It means that these activities and responsibilities are taking away from my time with students. When I am pushing papers, coordinating everything under the sun and mandated to serve on multiple committees, I rarely have time to design the classroom guidance lessons I’d like to do and I rarely have time to adequately research/prepare for my individual counseling sessions. I often feel like I am “putting out little fires” with students, staff, and parents.

Another major theme that emerged from the responses was that performing noncounseling duties was accepted as a reality of the job. Although many school counselors viewed noncounseling duties as tasks that could or should be done by other school professionals (19), or as resulting from role ambiguity (13), many cited that they simply had to be done (28). One school counselor stated, “It inevitably leads to the question of who will do the duty if we were not to. Resources are limited in many school districts these days.” Another added, “Counselors have always taken on or have been given other school assignments, it usually depends on the site administrator who often shares their overwhelming work load.” Yet another school counselor said, “It is somewhat expected because administration is not aware of all that we do, and the immediate demands are constantly arising.”

A final major theme emerging from school counselor responses regarding noncounseling duties was that many school counselors positively reframed some noncounseling duties within the context of their job, with many of them viewing them as fair share duties (17), as part of being on the school team (16) and even opportunities that positively affect their job (23). As one school counselor stated, “Obviously it would be ideal to be doing counseling all the time but I also feel that as a member of the team, supporting other team members in doing things that are not necessarily counseling related is also part of the job.”

Another counselor added the following:

It is difficult to define noncounseling duties in a school setting because every opportunity to be with students is an opportunity to build relationships that can be beneficial to the counseling relationship. In the same way, working with adults in the school community on committees for example can be the vehicle for forming positive professional relationships. In my school, I also teach classes for teachers and parents which increases my “counselor visibility” and has greatly enhanced my school practice. Some counselors would find teaching and serving on committees to be “noncounseling” but I find them to be “door opening.”

It appears that many school counselors view duties that allow them to interact with children and other school professionals positively, even if those duties may fit the noncounseling category.

Other School Factors and Burnout

To determine whether school factors that could tap into job demands and resources (e.g., caseload, meeting AYP and lack of principal support) were predictive of burnout, in addition to noncounselor duties, we conducted hierarchical regressions. We assessed the increase in prediction of burnout by other factors from the models with only noncounselor duties. For all but one measure of burnout (devaluing clients), caseload, AYP and principal support significantly added to the prediction of burnout over and above that accounted for by assignment of noncounseling duties. This was especially true for negative work environment. In all cases, principal support negatively predicted burnout (see Table 2).

A major qualitative theme was that individuals related their experience of burnout to organizational factors specific to their school. School factors cited as defining burnout included lack of time (36), budgetary constraints (13), lack of resources (8), lack of organizational support (8), lack of authority (4) and a negative school environment (4). One participant’s words seemed to encapsulate this theme when describing the experience of burnout: “When you feel you have too many responsibilities and not enough time or resources. When you feel overwhelmed by the amount of work. Feeling of longing to do some other job due to stress, difficulty coping with demands, paperwork, lack of support, lack of input, or other long-term difficulties on the job.”

Table 2

Results of Hierarchical Regression of Noncounselor Duties and Other School Factors Predicting Burnout

|

Burnout Measure |

|||||

|

Exhaustion |

Incompetence |

Negative work environment |

Devaluing client |

Deterioration in personal life |

|

| Δ R2 | 0.09*** | 0.07** | 0.43*** | 0.03 | 0.08*** |

| Full model | |||||

| R2 | 0.21*** | 0.09** | 0.49*** | 0.04 | 0.17*** |

| MSE | 12.73 | 8.68 | 8.82 | 2.84 | 10.12 |

| b clerical | 0.27*** | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.22* |

| b fair share | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.09 | –0.06 | 0.06 |

| b administrative | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.15* | –0.05 | 0.11 |

| b caseload (ASCA vs 251+) | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.14* | –0.01 | 0.09 |

| b caseload (ASCA vs. 400+) | 0.17* | 0.03 | 0.05 | –0.06 | 0.00 |

| b AYP | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.16* |

| b principal support | –0.17** | –0.23** | –0.62*** | –0.17* | –-0.20** |

Note. Hierarchical regressions adding other school factors (caseload, AYP, and principal support) to the model with noncounselor duties. N = 206.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Qualitative findings, although not AYP-specific or constituting major themes, indicated that some counselors felt stress regarding the call for data and accountability measures present in today’s school systems. One counselor described the situation as follows:

I think that the fact that ASCA has swallowed the NCLB “data-all-the-time” Kool Aid, adds to my stress tremendously. It encourages counselors to become quasi-administrators and data-collectors instead of doing the job that is encapsulated by our title: COUNSEL [sic] individuals and groups of kids in a school setting. When we are allowed to focus on the social and emotional needs of the whole child, we are best positioned to clear away the barriers to academic achievement. Our effect on test scores is indirect. Thus, it is a red herring to go chasing after “data” that proves we belong in a school.

Another participant stated, “The biggest drain and waste of time has to be, without a doubt, testing, testing, testing!”

Although principal support was not a major theme in the qualitative results, participants discussed principal support when referring to a lack of organizational support and a negative work environment in their schools. Another participant’s words seemed to echo the importance of supervisor support when discussing his or her own experience of burnout: “Stress from too much work and less resources. Supervisors becoming less supportive and more disciplinary. School is not a fun place to learn. So much for positive behavior supports.”

Effects of Other School Factors on Noncounseling Duties and Burnout

To determine whether other school factors, like meeting AYP, caseload and principal support may increase or lessen (i.e., moderate) the effects of noncounseling duties on burnout, we ran a series of moderation tests (see Baron & Kenny, 1986) to arrive at a model for each measure of burnout including only the meaningful moderators. It appears that meeting AYP and caseload can moderate the effect of noncounselor duties as they relate to exhaustion. Caseload also can moderate the effects on noncounselor duties as they relate to incompetence, devaluing clients and deterioration in personal life. However, even though adding the moderation of the SCARS Fair Share Activities (SFSA) by caseload increased the prediction of devaluing clients, the whole model was still not significant (R2 = .04). Therefore, we will not discuss this measure of burnout further; the remaining moderations, as indicated in Table 3, will be discussed in turn.

Table 3

Moderation Tests

|

Burnout measure |

|||||

| ΔR2 |

Exhaustion |

Incompetence |

Negative work environment |

Devaluing client |

Deterioration in personal life |

| SFSA*AYP | .01** | ||||

| SAA*AYP | .01* | ||||

| SCA*caseload1 | .03*** | .02*** | .02*** | ||

| SFSA*caseload1 | .01** | .02*** | .01** | ||

Note. Values in the table represent the change in R2 as a function of adding each moderator, in turn, to the main effects model (i.e., full model in Table 2). Only significant values are reported. 1Caseload was dummy coded, so two moderation terms were actually created—one for each dummy code. The ΔR2 values result from adding both terms. N = 206.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Exhaustion: Adequate Yearly Progress × noncounselor duties. Whether or not a school made AYP moderated the effect of assignment of both fair share and administrative duties. Assignment of these duties related to increased exhaustion among counselors at schools that made AYP (SFSA, r[152] = .27, p < .001; SCARS Administrative Activities (SAA), r[155] = .18, p = .026), but not at schools that did not make AYP (SFSA, r[64] = .01, p = .92; SAA, r[67] = .07, p = .56). As revealed in Figure 1, exhaustion remained high among those at schools that did not make AYP, regardless of fair share and administrative duties. However, at schools that did make AYP, exhaustion was lower when assignment of fair share and administrative duties was lower.

Figure 1. Mean predicted values of exhaustion as predicted by noncounselor duties as a function of (a) meeting AYP and (b) caseload.

Exhaustion seemed to be central in how school counselors related their experience of burnout. The overwhelming majority of school counselors qualitatively described the meaning of burnout in terminology and symptoms congruent with emotional exhaustion. Participants described burnout in terms of feeling tired (27), overwhelmed (27), stressed (27), exhausted (23), lacking energy (22), becoming emotionally drained (16), and unable to cope and respond to daily demands (10). One participant characterized burnout as “reaching the bottom of psychological energy,” while another one added that burnout is “being unable to complete my duties of caring for and assisting my students because I am exhausted, stressed, or completely overwhelmed.”

Exhaustion: Caseload × noncounselor duties. Assignment of clerical and fair share noncounseling duties differentially predicted exhaustion depending on caseload. Interestingly, the greatest variability and strongest relationships were at large caseloads (from 251–400; SCARS Clerical Activities (SCA), r[74] = .50, p < .001; SFSA, r[73] = .39, p < .001). In both cases, the lowest levels of exhaustion were seen for those with the fewest noncounseling duties.

Similar variability was seen at the ASCA-recommended level of moderate caseloads (fewer than 250) for assignment of clerical, but not fair share, duties related to exhaustion (SCA, r[75] = .34, p = .003; SFSA, r[70] = .10, p = .38). For counselors with the highest caseloads (greater than 400), assignment of clerical and fair share duties was not significantly or meaningfully related to exhaustion (SCA, r[68] = .11, p = .37; SFSA, r[67] = .05, p = .66). At the highest caseloads, exhaustion remained high regardless of fair share or clerical noncounselor duties. At a large caseload (and moderate caseloads as pertaining to clerical duties), exhaustion was lowest at the fewest noncounseling duties. It should be noted that for school counselors with caseloads at the ASCA-recommended levels (fewer than 250), exhaustion levels did not meaningfully increase even if fair share or clerical duties increased. Even though some school counselors defined burnout in terms of caseloads, this was not a major qualitative finding. One participant stated, when discussing caseload, “I am asked to provide critical services to 400 students and yet I make the same salary as teachers who are only responsible for educating one quarter of the students on my case load.”

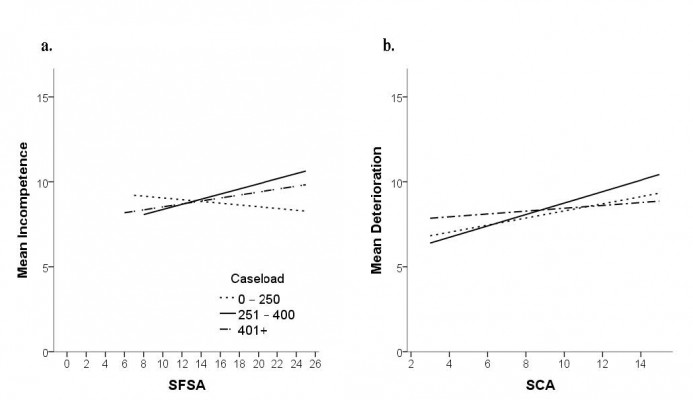

Incompetence: Caseload × noncounselor duties. Assignment of fair share duties differentially related to incompetence as a function of caseload. It was only at a large caseload (251–400) that fair share duties predicted incompetence (r[72] = .24, p = .04). At moderate (0–250; r[71] = –.07, p = .57) and extra-large caseloads (more than 400; r[66] = .12, p = .33), assignment of fair share duties did not significantly or meaningfully relate to incompetence. As depicted in Figure 2, the lowest levels of incompetence are reported for those with moderate or large caseloads at low levels of fair share duties. For those at larger caseloads, though, incompetence increases as fair share duties increase, indicating that the assignment of fair share duties with the existence of large caseloads is related to school counselor self-reported incompetence levels. For those with small caseloads, levels of incompetence remain steady.

Figure 2. Mean predicted values of (a) incompetence as predicted by SFSA and (b) deterioration in personal life as predicted by SCA, both as a function of caseload.

Qualitative results indicated that reduced effectiveness also was a major common theme. Participants cited feeling that they were not effective (60) and no longer made a difference (12) as descriptors of burnout. One participant stated, “It means that I am no longer helpful to my students. I feel like I’m extremely tired and over-worked and consequently my effectiveness as a school counselor is negatively impacted.” Yet another participant described burnout as “being overwhelmed by so many duties and responsibilities over an extended amount of time. The result in turn is being a less focused, determined, dedicated, effective school counselor.”

Deterioration in personal life: Caseload × noncounselor duties. Assignment of clerical duties related differently to deterioration in personal life depending on caseload. At an extra- large caseload (more than 400), the relationship between clerical duties and deterioration was not significant (r[68] = .11, p = .37). However, the relationship was positive at moderate (0–250; r[75] = .25, p = .03) and large caseloads (251–400; r[74] = .38, p < .001). As depicted in Figure 2, at moderate and large caseloads, deterioration in personal life starts out low with low levels of clerical duties, but increases as caseload increases. However, for those with the highest caseloads, deterioration in personal life remains steady.

Although not a major theme, qualitative results indicated that some participants discussed burnout in terms of a spillover effect (22), with symptoms experienced beyond the workplace and in school counselors’ personal lives. One participant described burnout as “work becoming overwhelming enough that it is negatively affecting other parts of your life and dreading work every day because you do not think you can deal with anything else.”

Additional qualitative findings. Job dissatisfaction, a factor not examined quantitatively, was a major additional theme that emerged from the participants’ discussion of their experience of burnout. Several participants discussed burnout as simply going through the motions at work (9) and having difficulty continuing to do the job (18). One participant defined burnout as “no longer enjoying the job. Counting the days. Waiting for the weekend. Thinking about retirement too much. Rather not go to work.” Another participant discussed burnout as “waking up and not wanting to go to work . . . or being at work and just going through the motions. Dreaming of jobs where you don’t deal with emotions or hardships!”

Discussion

In sum, the quantitative results suggest that the assignment of noncounselor duties positively predicts burnout—especially exhaustion, negative work environment and deterioration in personal life (and incompetence to a lesser extent). Qualitative results echo these findings, as participants discussed their experience of burnout in terms of emotional exhaustion, reduced effectiveness, performance of noncounseling duties and being tied to organizational factors in their school setting. Another major qualitative theme emerging from the participants’ experience of burnout is job dissatisfaction. School counseling literature has noted that demands placed upon school counselors are rising (Cunningham & Sandhu, 2000; Gysbers et al., 1999; Herr, 2001), that many feel stressed and overwhelmed with the numerous job demands that have been placed on them (Kendrick et al., 1994; Lambie & Williamson, 2004; Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006), and that performing inappropriate duties is linked to job dissatisfaction (Baggerly & Osborn, 2006). However, the results of this study surpass current literature by providing support for the assignment of noncounseling duties as a predictor of burnout in school counselors.

More specifically, the results indicate that the assignment of clerical duties predicts exhaustion and deterioration in personal life, while the assignment of administrative duties predicts negative work environment. These results are supported by the qualitative findings: while the majority of school counselors surveyed viewed the assignment of noncounseling duties as having adverse personal and professional effects, or resignedly accepted them as a reality of the job, some counselors also reframed noncounseling duties within the context of their job, distinguishing fair share duties and suggesting that performing the latter was part of being a team, and even an opportunity to better perform their job.

Quantitative results, however, indicate that the assignment of fair share duties for school counselors who already have large or extra-large caseloads is related to increased feelings of incompetence in their jobs. Reduced effectiveness is also a major qualitative theme that emerged when participants discussed their experience of burnout. It appears that despite qualitative results supporting some counselors’ positive view of performing fair share duties, quantitative results also point out that fair share duties have negative effects for counselors with large caseloads, or for those working in a school that has not met AYP. This finding indicates that clerical and administrative duties may be potential areas for intervention and advocacy for school counselors. Furthermore, school counselors may benefit from taking into account particular school factors when evaluating the effect of fair share duties on burnout.

Results indicate that support from the school principal can reduce burnout, as a unique predictor and not as it interacts with noncounselor duties. This finding is congruent with Lee (2008), who reported that level of perceived support from the school principal was a significant predictor of emotional exhaustion, a dimension of burnout, among school counselors. Although not a major theme, participants also linked principal support to their personal meaning of burnout, as some related it to a lack of organizational support and a negative work environment in their schools.

The results of moderation analyses suggest that meeting AYP can be a buffer against burnout as a result of fair share and administrative duties when those duties are low. Similarly, for school counselors working in a school that did not meet AYP, emotional exhaustion remains high, regardless of performing fair share or administrative duties. Schools that do not meet AYP are subject to interventions that can eventually lead to the replacement of staff, including school counselors, a stressor that is potentially more threatening than performing a low level of noncounseling duties. Although not a major qualitative theme, participants discussed budgetary constraints and accountability standards as stressors in their work environment. Although the consequences of not meeting AYP have been implicated in increased stress for school staff and in negative impacts on school climate (Paisley & McMahon, 2001; Thompson & Crank, 2010), no other studies to date have examined the relationship between meeting AYP, performing noncounseling duties and experiencing school counselor burnout.

Similarly, a low or moderate caseload can be a buffer against exhaustion related to fair share and clerical duties, but only when those duties are lower. At higher levels of noncounselor duties, even meeting AYP or having a lower caseload does not buffer against exhaustion. These findings seem consistent with previous research exploring school counselor demands: although caseload size was rated by participants as demanding, it was secondary to paperwork requirements, a duty that fits the noncounseling duties category (McCarthy et al., 2010). These results also are supported by the qualitative findings: while performing noncounseling duties is a major theme related to the experience of burnout, caseload does not feature prominently. However, the distinction in caseload numbers, based on ASCA recommendations, seems to be a meaningful one; if number of caseloads is at or below the recommended 250, levels of emotional exhaustion do not increase even if noncounseling duties are high. Caseloads that exceed the 400 threshold increase emotional exhaustion regardless of noncounseling duties. It seems that counselors operating at those very high caseloads are experiencing exhaustion from the sheer number of students they must serve, regardless of performing noncounseling duties.

Implications for Practice: School Counselors and Counselor Educators

It is evident from this study that school counselors face many organizational challenges that may make them vulnerable to experiencing the negative effects of burnout. Supervisors may be the first to notice stressed-out counselors and be privy to feelings and concerns related to those challenges (Lee at al., 2010). In a school setting, principals can have extensive influence on determining the role of the school counselors with whom they work (Amatea & Clark, 2005; Dollarhide, Smith, & Lemberger, 2007). Research suggests that when compared to school counselors, principals seem to underestimate the time that school counselors spend on clerical and administrative noncounseling duties, and place more importance on the performance of other noncounseling duties such as record keeping, coordinating the standardized testing program and scheduling (Finkelstein, 2009). As few graduate programs in administration include courses in school counseling, school principals may receive little training or education regarding the appropriate role of the school counselor and the nature of the comprehensive school counseling program, making school counselor advocacy even more imperative (Dollarhide et al., 2007; Fitch, Newby, Ballestero, & Marshall, 2001). It appears that administrators may especially benefit from a discussion regarding the school counselor’s role (Amatea & Clark, 2005), and that facilitating an increased awareness of school counselor burnout may result in interventions dedicated to preventing and ameliorating burnout (Lee et al., 2010).

Counselor educators also are responsible for advocating for the profession and promoting best practices for school counselors. They are uniquely positioned to expose future school counselors to quality training and resources. Indeed, adequate training can reduce role stress for school counselors (Culbreth, Scarborough, Banks-Johnson, & Solomon, 2005). Membership in professional organizations can serve as an important resource for beginning school counselors, as it can reduce the likelihood of becoming isolated and encourage practices according to professional standards (Baker & Gerler, 2004). Resources such as self-assessment tools that can be shared with principals to identify gaps in perceptions and priorities, and strategies for promoting collaboration and preventing burnout, are all available through professional organizations and publications. Equipping school counselors with knowledge, resources and strategies to optimize effectiveness early in their careers may better prepare them for the challenges inherent in their profession.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

Certain limitations in this study may have affected the reported outcomes. First, utilizing a volunteer sample of school counselors who were exclusively members of ASCA poses a limit to generalizability. Despite use of a nationwide sample, responses cannot be generalized to school counselors who may not belong to ASCA. It also is possible that school counselors experiencing the most severe form of burnout may be underrepresented in this study, as those active in professional organizations may be less likely to experience high levels of burnout. As all data gathered in this study utilized self-reports, school counselors experiencing high levels of burnout may have opted out due to the uncomfortable nature of the topic.

Second, the addition of the open-ended questions to the quantitative questionnaire did not result in an extensive qualitative data set or the opportunity for additional follow-up discussion, providing only specific qualitative data from one point in time. However, the method of employing written responses to open-ended questions to gain broad information on sensitive topics (such as occupational burnout) has merit in this study (Friborg & Rosenvinge, 2013; Montero-Marín et al., 2013) and can be successfully utilized to triangulate or converge quantitative data (Hanson, Creswell, Plano Clark, Petska, & Creswell, 2005).

Replicating the results of this study with a random sample of school counselors who are practicing nationwide but are not exclusively ASCA members may increase the representativeness of the sample. Multi-informant, multi-method data would be useful in further examining burnout and the assignment of noncounseling duties and enhancing validity. Future studies utilizing a mixed-methods approach could incorporate semistructured interviews to collect more in-depth qualitative responses and enrich school counseling literature on burnout.

References

Amatea, E. S., & Clark, M. A. (2005). Changing schools, changing counselors: A qualitative study of school administrators’ conceptions of the school counselor role. Professional School Counseling, 9, 16–27.

American School Counselor Association. (2014). Careers/Roles. Retrieved from http://www.schoolcounselor.org/school-counselors-members/careers-roles

Astramovich, R. L., & Holden, J. M. (2002). Attitudes of American School Counselor Association members toward utilizing paraprofessionals in school counseling. Professional School Counseling, 5, 203–210.

Baggerly, J., & Osborn, D. (2006). School counselors’ career satisfaction and commitment: Correlates and predictors. Professional School Counseling, 9, 197–205.

Baker, S. B., & Gerler, E. R. (Eds.). (2004). School counseling for the twenty-first century (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 170–180. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bryant, R. M., & Constantine, M. G. (2006). Multiple role balance, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction in women school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 9, 265–271.

Burnham, J. J., & Jackson, C. M. (2000). School counselor roles: Discrepancies between actual

practice and existing models. Professional School Counseling, 4, 41–49.

Coll, K. M., & Freeman, B. (1997). Role conflict among elementary school counselors: A

national comparison with middle and secondary school counselors. Elementary School

Guidance and Counseling, 31, 251–261.

Connides, I. (1983). Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods in survey research on aging: An assessment. Qualitative Sociology, 6, 334–352. doi:10.1007/BF00986684

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Culbreth, J., Scarborough, J., Banks-Johnson, A., & Solomon, S. (2005). Role stress among practicing school counselors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 45, 58–71. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb00130.x

Cunningham, N. J., & Sandhu, D. S. (2000). A comprehensive approach to school–community violence prevention. Professional School Counseling, 4, 126–133

Demerouti, E., Nachreiner, F., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Dillman, D. A. (2007). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Dollarhide, C. T., Smith, A. T., & Lemberger, M. E. (2007). Critical incidents in the development of supportive principals: Facilitating school counselor–principal relationships. Professional School Counseling, 10, 360–369.

Driscoll, D. L., Appiah-Yeboah, A., Salib, P., & Rupert, D. J. (2007). Merging qualitative and quantitative data in mixed methods research: How to and why not. Ecological and Environmental Anthropology, 3, 19–28.

Erford, B. T. (2011). Transforming the school counseling profession (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Feldstein, S. B. (2000). The relationship between supervision and burnout in school counselors (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Duquesne University, Pittsburg, PA.

Finkelstein, D. (2009). A closer look at the principal–counselor relationship: A survey of principals and counselors. New York, NY: National Office for School Counselor Advocacy, American School Counselor Association, and National Association of Secondary School Principals. Retrieved from http://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/CloserLook.pdf

Fitch, T., Newby, E., Ballestero, B., & Marshall, J. L. (2001). Future school administrators’ perceptions of the school counselor’s role. Counselor Education & Supervision, 41(2), 89–99. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2001.tb01273.x

Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues, 30, 159–165. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

Friborg, O., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2013). A comparison of open-ended and closed questions in the prediction of mental health. Quality & Quantity, 47, 1397–1411. doi:10.1007/s11135-011-9597-8

Gunduz, B. (2012). Self-efficacy and burnout in professional school counselors. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12, 1761–1767.

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2000). Developing and managing your school guidance program (3rded.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Gysbers, N. C., Lapan, R. T., & Blair, M. (1999). Closing in on the statewide implementation of a comprehensive guidance program model. Professional School Counseling, 2, 357–366.

Hanson, W. E., Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., Petska, K. S., & Creswell, J. D. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 224–235. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.224

Herr, E. L. (2001). The impact of national policies, economics, and school reform on comprehensive guidance programs. Professional School Counseling, 4, 236–245.

Kendrick, R., Chandler, J., & Hatcher, W. (1994). Job demands, stressors, and the school counselor. The School Counselor, 41, 365–369.

Kolodinsky, P., Draves, P., Schroder, V., Lindsey, C., & Zlatev, M. (2009). Reported levels of satisfaction and frustration by Arizona school counselors: A desire for greater connections with students in a data-driven era. Professional School Counseling, 12, 193–199. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-12.193

Lambie, G. W. (2002). The contribution of ego development level to degree of burnout in school counselors. Dissertation Abstracts International, 63, 508.

Lambie, G. W., & Williamson, L. L. (2004). The challenge to change from guidance counseling to professional school counseling: A historical proposition. Professional School Counseling, 8, 124–131.

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 123–133. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123

Lee, R. V. (2008). Burnout among professional school counselors. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. (AAT 304683311)

Lee, S. M., Baker, C. R., Cho, S. H., Heckathorn, D. E., Holland, M. W., Newgent, R. A., . . . Yu, K. (2007). Development and initial psychometrics of the counselor burnout inventory. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 40, 142–154.

Lee, S. M., Cho, S. H., Kissinger, D., & Ogle, N. T. (2010). A typology of burnout in professional counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 131–138. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00001.x

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (1999). Designing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2, 99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. In S. T. Fiske, D. L. Schacter, & C. Zahn-Waxler (Eds.), Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

McCarthy, C., Van Horn Kerne, V., Calfa, N. A., Lambert, R. G., & Guzman, M. (2010). An exploration of school counselors’ demands and resources: Relationship to stress, biographic, and caseload characteristics. Professional School Counseling, 13, 146–158.

Montero-Marín, J., Prado-Abril, J., Carrasco, J. M., Asensio-Martínez, Á., Gascón, S., & García-Campayo, J. (2013). Causes of discomfort in the academic workplace and their associations with the different burnout types: A mixed-methodology study. BMC Public Health, 13, 1240. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1240.

Paisley, P. O., & McMahon, H. G. (2001). School counseling for the 21st century: Challenges and opportunities. Professional School Counseling, 5, 106–116.

Rayle, A. D. (2006). Do school counselors matter? Mattering as a moderator between job stress and job satisfaction. Professional School Counseling, 9, 206–215.

Repetti, R. L. (1993). The effects of workload and social environment at work on health. In L. Goldberger & S. Breznitz (Eds.), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects (pp. 368–385). New York, NY: Free Press.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

Scarborough, J. L. (2005). The School Counselor Activity Rating Scale: An instrument for gathering process data. Professional School Counseling, 8, 274–283.

Scarborough, J. L., & Culbreth, J. R. (2008). Examining discrepancies between actual and preferred practice of school counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 446–459. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00533.x

Sears, S. J., & Navin, S. L. (1983). Stressors in school counseling. Education, 103, 333–337.

Silverman, D. (1999). Interpreting qualitative data. London, England: Sage.

Thompson, M. J., & Crank, J. N. (2010). An evaluation of factors that impact positive school climate for school psychologists in a time of conflicting educational mandates. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED507929)

Thompson, R. A. (2012). Professional school counseling: Best practices for working in the schools (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Wilkerson, K., & Bellini, J. (2006). Intrapersonal and organizational factors associated with burnout among school counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84, 440–450. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00428.x

Yildrim, I. (2008). Relationship between burnout, sources of social support and sociodemographic variables. Social Behavior and Personality, 36, 603–616. doi:10.2224/sbp.2008.36.5.603

Gerta Bardhoshi, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of South Dakota. Amy Schweinle and Kelly Duncan are associate professors at the University of South Dakota. Correspondence can be addressed to Gerta Bardhoshi, Division of Counseling and Psychology in Education, 414 E. Clark Street, Vermillion, SD 57069, gerta.bardhoshi@usd.edu.