Sep 2, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 1

Richard A. Wantz, Michael Firmin

Numerous sources of information influence how individuals perceive professional counselors. The stressors associated with entering college, developmental differences, and factors associated with service fees may further impact how college students view mental health professionals and may ultimately influence when, for what issues, and with whom they seek support. Individual perceptions of professional counselors furthermore impress upon the overall identity of the counseling profession. Two hundred and sixty-one undergraduate students were surveyed regarding their perceptions of professional counselors’ effectiveness and sources of information from which information was learned about counselors. Overall, counselors were viewed positively on the dimensions measured. The sources that most influenced perceptions were word of mouth, common knowledge, movies, school and education, friends, books, and television.

Keywords: professional counselors, perceptions, counselor effectiveness, professional identity, undergraduates

Perception is not reality, but perception is nonetheless a very cogent relative to how humans come to understand reality. Moreover, perception tends to drive behavior and decisions made by consumers. In the present context, we are interested in how college students come to perceive human service providers across a number of variables. The constructs explored are not novel, as this genre of research has been assessed in decades past (e.g., Murray, 1962; Strong, Hendel, & Bratton, 1971; Tallent & Reiss, 1959; West & Walsh, 1975). However, we believe the topic warrants refreshed attention, particularly with the professional licensure acquired among all human service professions: psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, marriage and family therapists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses.

The media tends to exert a cogent effect on students’ perceptions across multiple life domains, including human service professionals (Von Sydow, Weber, & Christian, 1998). Students also are affected by other information sources such as previous experiences with their high school (guidance) counselors, personal therapy, clergy, family doctors, parental influence, and input from peers (Tinsley, de St. Aubin, & Brown, 1982). Students’ perceptions of human service providers also may be affected by various campaigns, typically receiving information-influence from multiple sources that actively attempt to shape their perceptions of mental health services’ value and efficacy (Hanson, 1998).

Some human service professions have been more aggressive in how they advocate their service value to the public. Fall, Levitov, Jennings, and Eberts (2000) note that psychiatrists and psychologists generally have dwarfed counselors’ efforts at advocacy. Counselors, as a profession, have struggled significantly with their own identity (Garrett & Eriksen, 1999; Eriksen & McAulife, 1999), which likely affects this phenomenon. That is, if one’s identity is unclear to the respective professionals, then probably it will negatively affect its status among the laity (Gale & Austin, 2003). Psychology generally has lagged behind psychiatry in terms of the public’s professional perceptions (Webb & Speer, 1985), although Zytowski et al. (1988) reported that people frequently confused the terms psychiatrist and psychologist relative to function. Counseling psychologists also often seem to be confused with professional counselors in the public’s understanding (Hanna & Bemak, 1997; Lent, 1990).

Social work has existed as a vocation for over a hundred years. Kaufman & Raymond (1995) reported that the public’s awareness of the profession’s perception was somewhat negative in their survey sample. LeCroy and Stinson (2004) and Winston and Stinson (2004) likewise found individuals in their particular sample to be relatively knowledgeable regarding social workers’ responsibilities, although reported attitudes were more positive than those reported by Kaufman and Raymond. This partly may be due to the fact that respondents reported more favorable perceptions of social workers as helping those needing avocation than they did for social workers as therapists. Sharpley, Rogers, and Evans (1984) suggest that marriage and family therapy, as a profession, is relatively cryptic to the general public. That is, people generally deduce what such human service personnel do, as indicated by the title, but do not have as much first-hand knowledge or experience with such professionals as they do with counselors, social workers, psychologists, and other professionals.

Ingham (1985) notes that a helping profession’s overall image affects clinicians in that profession relative to their abilities in helping clients to utilize their services. This conclusion makes logical sense in that consumers’ confidence in the care provided is subjective and highly influenced by psychological variables, such as idiographic perceptions. Attempts at educating the public regarding an apt understanding of what a human service profession has to offer has shown various levels of effectiveness (Pistole & Roberts, 2002). Nonetheless, Pistole (2001) also notes that the general public finds the distinctions among the various human service providers to be bewildering. In short, without periodic reminders, the public’s image of various human service personnel may reconverge in a fog of misperception.

Since many individuals have never experienced the services of mental health clinicians, often their perceptions are based on reports or intuitively acquired opinions. For example, Trautt and Bloom (1982) report that fee structures affect perceptions of status and effectiveness provided by clinicians. The basic understanding, of course, is that the more expensive the treatment, the higher its perceived value and professional status. That, of course, can result in self-fulfilling prophesies—with people paying more money expecting more from therapy—and experiencing better success rates. We are unaware of any studies where clients were randomly assigned to professional therapists and (systematically) charged varying pay rates. Such a study, controlling for fee structures, might yield some valuable data to the present discussion regarding how the public perceives the value of respective human service professionals.

Beyond the public’s general perceptions on this topic, however, we are particularly focused on students’ perceptions. Hundreds of thousands of students annually utilize the services of university counseling centers, as well as private practice therapists and other human service agencies. With the added stress of academics, social pressures, being away from home for the first time, transitioning from teenage to adult responsibilities, dating, drinking alcohol, and other similar stressors, having apt utilization of psychotherapeutic services is paramount for college students. Turner and Quinn (1999) suggest that college students’ perceptions differ from the population-in-general, and research data from one group may not accurately generalize to the other.

Notwithstanding obvious developmental differences between college students and more mature adults from the general population, counseling students may not pay (directly, out of pocket) for the services available to them. Campus counseling centers, for example, typically receive funding from tuition or generic student fees, rather than students paying direct dollars for the services. Additionally, most full-time students remain on their parents’ medical insurance which also offsets financial costs involved in private practice expenses. In short, cost of services seems to be a significant variable for the general population (Farberman, 1997) that may not load with the same degree of importance vis-a-vis college students. Additionally, titles (such as “doctor”) may not have as much bearing with the general public (Myers & Sweeney, 2004) as they do with college students who routinely use such nomenclature with professors and others on a daily basis. In short, while we accommodate research findings that compare the various mental health professionals as perceived by the general public (e.g., Murstein & Fontaine, 1993), we also treat the results with some degree of prudence and believe college students represent a distinct population worthy of particular focus and exploration.

Gelso, Brooks, and Karl (1975) conducted a study that was similar in some respects to our present one. They surveyed 187 students from a large eastern university with a sample of 103 females and 84 males. Subjects were asked to rate perceived characteristics of various human service professionals, including high school counselors, college counselors, advisers, counseling psychologists, clinical psychologists, and psychiatrists. They found that overall college students did not report significant differences relative to professionals’ personal characteristics. However, they did report differences among the human service providers relative to their perceived competencies in treating various hypothetical presenting problems.

In the 30 years subsequent to this study, we are interested in how student perceptions have changed over time. Additionally, the Gelso, Brooks, and Karl (1975) study did not account for students’ perceptions of social workers, marriage and family therapists, or psychiatric nurses. Given the present milieu, we are more interested in these professionals than the categories of school counselors or advisors. Additionally, we also chose to combine the categories of counseling and clinical psychologists into the generic grouping, “psychologist.” The specific questions asked of students also differed in our present study. However, the general tenor of the two studies is similar—and we believe the updating of knowledge in this area has significant importance for those working with college students in various capacities and milieus.

Warner and Bradley (1991) also conducted a study similar to the present one. Their participants included 60 men and 60 women who were undergraduate college students enrolled in a University of Montana introductory psychology course. They assessed student perceptions of master’s-level counselors, clinical psychologists, and psychiatrists on multiple variables. Findings included students reporting their perceptions of counselors as possessing more caring-type qualities. Psychiatrists were seen as most able to address severe psychopathology and psychologists were viewed as more academics and researchers than as therapists.

Method

Participants

We surveyed 261 students from three sections of a general psychology course for this study. The course was selected, in part, because it is included in the university’s general studies core curriculum. Consequently, it represented a relatively wide range of majors from the student body and included students from freshman through senior status. The sample was taken at a selective, private, comprehensive university located in the Midwest with a study body of approximately 3,000 students. It included 167 women and 92 men with ages ranging from 17 to 55. The students were mostly Caucasian with 9% identifying themselves as ethnic minorities representing 34 states.

Procedure

The instrument was first pilot tested (Goodwin, 2005) to a group of undergraduate students at a regional state university prior to utilizing it in the present research project. Modifications were made in clarifying ambiguous terminology, instructions, and time to complete. Due to practical considerations, the instrument was designed to be completed in about one-half of a normal class period. The survey was administered during a normal class period with students having the option to participate at will without reward or penalty for doing so. Two students chose not to complete the surveys for undisclosed reasons.

The survey queried students regarding their perceptions of human service professionals (HSP), taking about 20–25 minutes to complete. Anonymity was provided to all students regarding answers to all items. Questions were asked about the overall perceived effectiveness of various HSPs, for which types of problems they might recommend various HSPs, and overall perceptions about the various HSPs. Although obviously many types of HSPs exist, this particular survey focused on psychiatrists, psychologists, professional counselors, marriage & family therapists, social workers and psychiatric nurses. In order to control for order effects as potential threats to internal validity (Sarafino, 2005), the various HSPs were presented in random order each time they appeared throughout the survey. The amount of data collected from the survey was relatively substantial. However, given the practical number of journal pages that can be reasonably devoted to presenting the information, along with our desire to comprehensively address perceptions of counselors, the present article addresses only this particular segment of the data collection.

Results

We organized the survey’s results in terms of the counseling services utilized, how effective students perceived counseling to be, for what types of problems or issues counselors are thought to be apt, how students came to view their perceptions of professional counselors, and qualities thought to characterize professional counselors. All percentages are rounded for clarity of reading and presentation, except where percentages fall below 1%.

Types of Services Utilized

At the end of the questionnaire, students were asked to confidentially self-disclose whether or not they had received services from a HSP. The question was placed at the end in order to have students already somewhat acclimated to HSPs and to have them somewhat more comfortable with the world of different types of HSPs. Of those answering the question, 28% of the participants indicated having received assistance from a HSP prior to completing the survey. The specific question asked whether or not students received prior professional assistance regarding personal, social, occupational or mental health concerns. About 3% of all the participants chose not to answer this particular question. However, of the 28% only 1% indicated that they did not know the profession of their HSP, indicating that most of the respondents who previously had utilized HSP services were aware whether the professional they saw was a counselor, psychologist, social worker, etc. Relatively few (

States possess a variety of titles by which professional counselors can or should be called (Freeman 2006). Consequently, rather than asking students simply to identify whether or not they had previously utilized the services of a “counselor,” we specified some types of counselors they may have seen. These included professional counselor, pastoral counselor, addictions or chemical dependency counselor, rehabilitation counselor, clinical mental health counselor, professional clinical counselor, and school guidance counselor.

Of the 28% of students who indicated they had previously utilized HSP services, three particular types of counselors were more prominent than the others. Namely, 16% indicated having seen a school counselor, 11% saw a professional counselor, and 9% saw a pastoral counselor. Relatively few students indicated having seen a rehabilitation counselor (0.4%), an addictions counselor (0.8%), or a mental health/clinical counselor (3%).

Perceived Overall Effectiveness

Students were asked to indicate how effective they believed professional counselors are overall. The particular question was worded as follows: In general, what is your opinion about how overall effective professional counselors would be with helping a mental health consumer? The options provided, with descriptors in parenthesis, were 1 (Positive), 2 (Neutral), 3 (Negative), and 4 (Unsure or don’t know). The intent of the question was to capture the gestalt of students’ thinking regarding professional counselors, prior to probing more deeply vis-a-vis types of counselors and for which kinds of issues they might find effective interventions.

Only 3% of the participants indicated having no opinion regarding this question. Another 3% indicated viewing professional counselors negatively. A total of 28% of the participants indicated having neutral views regarding counselors’ overall effectiveness. Sixty-six percent of the participants indicated having a positive view of professional counselors.

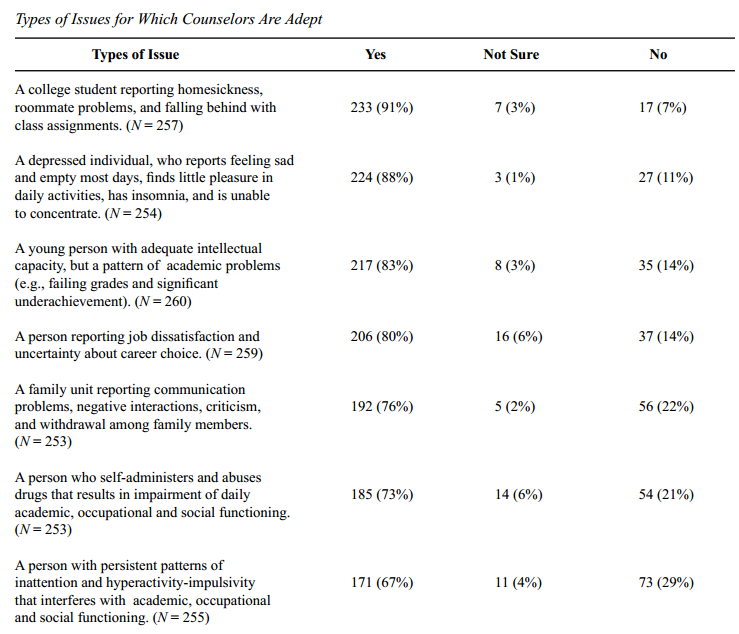

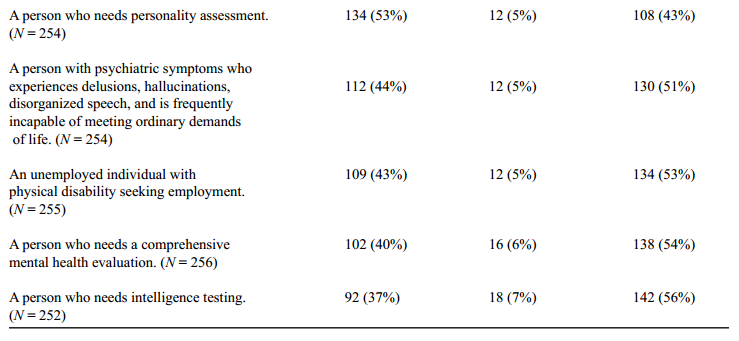

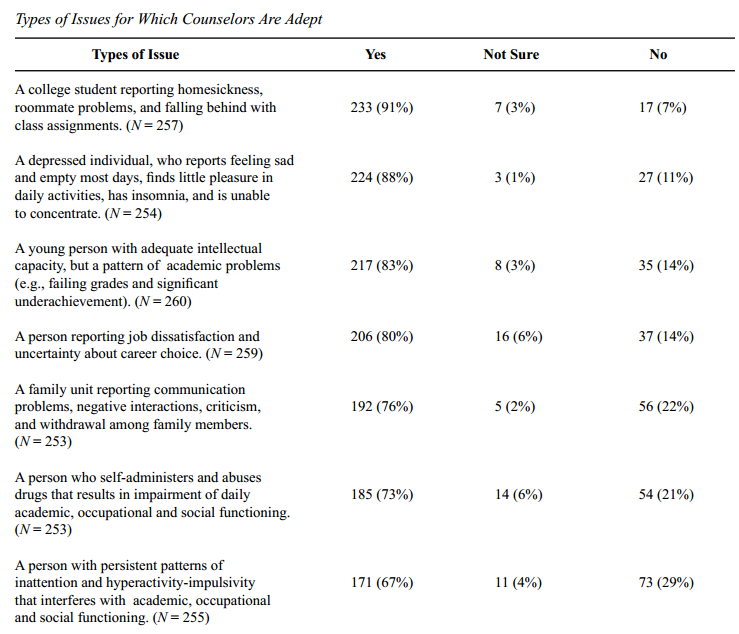

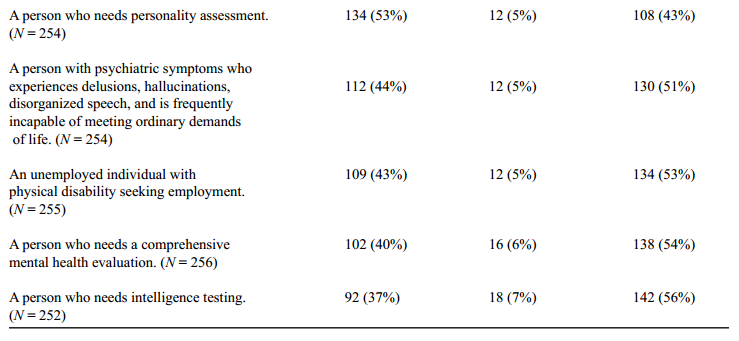

Types of Issues for Which Counselors Are Adept

Students were asked to identify for what types of issues they believed professional counselors would be particularly adept. They were provided with 12 different issues and asked to rate them as Yes (I would recommend a professional counselor for this situation), No (I would not recommend a professional counselor for this situation), or NS (Not sure, not familiar). Relatively few students skipped these questions or chose not to respond (range=0.8% to 3.4%). In other words, response rates were consistently high for these questions, obviously adding to the interpretation process. The same is true with students indicating that they were unsure or unfamiliar. Namely, on average 4% or so of students indicated being unsure for the situations presented (range=1.9 to 6.9). Results showed three clusters of participants’ responses.

The first cluster had four prominent responses, exhibited by 80% or more of the respondents—they involved college issues, academic problems, depression, and career counseling. A total of 91% of the participants indicated believing a professional counselor would be effective for helping college students who report homesickness, roommate problems, and falling behind with class assignments. A similar number (88%) believed that a professional counselor would be effective with a depressed individual who reports feeling sad and empty most days, finds little pleasure in daily activities, has insomnia, and is unable to concentrate. Comparable responses (83%) were seen for professional counselors addressing a young person with adequate intellectual capacity, but a pattern of academic problems (e.g., failing grades and significant underachievement). Finally, 80% of participants indicated that a professional counselor would be effective for a person reporting job dissatisfaction and uncertainty about career choices.

The next cluster of responses involved issues of family dysfunction, substance abuse, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Seventy-six percent of participants indicated feeling that professional counselors were effective for a family unit reporting communication problems, negative interactions, criticism, and withdrawal among family members. For cases when a person self-administers and abuses drugs that results in impairment of daily academic, occupational and social functioning, 73% of the respondents in our survey believed a professional counselor would be effective. Sixty-seven percent of participants indicated that a professional counselor would be effective when a person with persistent patterns of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with academic, occupational, and social function.

The final cluster of participants’ responses involved issues of personality assessment, intelligence testing, psychotic symptoms, physical disabilities, and mental health evaluations. Just over half (53%) of the participants indicated that professional counselors were apt for working with a person who needs personality assessment. Forty-four percent said that a professional counselor would be effective for a person with psychiatric symptoms who experiences delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and is frequently incapable of meeting ordinary demands of life. When asked if an unemployed individual with a physical disability seeking employment would be a target source for a professional counselor, 43% answered affirmatively. Only 40% of participants indicated that a professional counselor would be effective in helping a client who needs a comprehensive mental health evaluation. Fewer (37%) indicated that intelligence testing was germane for a professional counselor.

Table 1

Sources of Perceptions about Counselors

Another line of inquiry addressed the identified sources by which students indicated they developed their perceptions about counselors. In other words, they told us about the factors that influenced them the most regarding how they came to think about professional counselors. The options from which to choose included books, common knowledge, friends or associates, HSPs, insurance company or carrier, Internet, magazines, physician or nurse, movies, newspapers, personal experience, school and education, and television. Only 2% of the participants declined to participate in this section of the survey or marked “none.”

Instructions asked students to complete this section in two steps. First, they were to indicate (by checking a corresponding box) whether or not they learned about a professional counselor from the identified source. Students were told they could select multiple sources. In the second step, they were asked to rate whether the information about the HSP was 1 (positive), 2 (neutral) or 3 (negative). Only 2% of the students marked a box described as “other,” indicating that the categories provided were relatively comprehensive. Results from this portion of the survey showed the data falling into three clusters. The two clusters representing extreme scores were of relatively equal size, while the third or middle was small (only two sources in the category).

The first cluster showed the following items as being relatively influential in how students came to understand the roles of professional counselors: common knowledge (84%), movies (63%), school and education (60%), friends (55%), books (49%) and television (44%). The middle cluster included personal experience (27%) and Internet (24%). The finding that 27% indicated personal experience to be influential is consistent with the demographic portion of the questionnaire where 28% of students said they had personal contact with a HSP prior to completing the survey. The third cluster comprised those sources that participants said were relatively non-influential in generating their perceptions of professional counselors. They included magazines (20%), physician or nurse (18%), newspaper (13%), HSPs (10%) and insurance companies (5%).

Results from the second step in the survey are more difficult to summarize. The data was more dispersed than the first step, although three clusters inductively emerged. Some items received few responses, as they were not selected very frequently in step one. The percentages listed do not add up to 100% for each item because the remaining percentage for each item is accounted by students who did not provide answers for that item. For example, if an item had 1% positive, 1% neutral, and 1% negative, then 97% of the participants simply left the question blank.

The first were items where students indicated that professional counselors were as viewed mostly positive. These included school and education (43% positive, 13% neutral and 3% negative), friends (38% positive, 10% neutral and 6% negative), books (30% positive, 17% neutral and 2% negative), personal experience (17% positive, 7% neutral and 3% negative), physicians (10% positive, 6% neutral and 2% negative), and HSPs (8% positive, 0.8% neutral and 0.8% negative).The second cluster comprised items that were rated as being mostly neutral and with relatively few positive indicators. These included: movies (14% positive, 28% neutral and 19% negative) and television (13% positive, 25% neutral and 6% negative). The third cluster showed a relative spread of responses, although there were few negatives in each category. They included: common knowledge (38% positive, 42% neutral and 3% negative), magazines (10% positive, 8% neutral 3% negative), Internet (10% positive, 12% neutral and 1% negative), newspapers (5% positive, 6% neutral and 3% negative), and insurance companies (0.8% positive, 2% neutral and 2% negative).

Perceived Counselor Qualities

The final portion of the questionnaire addressed how participants viewed various professional counselors’ characteristics. Students were asked to identify statements that they believed to be true about professional counselors, based on their overall knowledge of them. Options included competent, can be in independent private practice, diagnose and treat mental and emotional disorders, doctoral degree required to practice, intelligent/smart, overpaid, prescribe medication and trustworthy. Consistently, only 1% of the participants chose not to respond to this portion of the survey, making interpretation for this section relatively straightforward. The findings fell neatly into two categories: characteristics counselors presumably possess and those they do not.

Characteristics that students believed professional counselors possess include being competent (81%), independent private practice (81%), trustworthy, (79%), and intelligent/smart (77%). Contrariwise, participants identified the following as not characterizing professional counselors, as indicated by the relatively low percentages of marked responses: doctorate required (30%), diagnose and treat mental disorders (22%), overpaid (16%) and prescribe medications (5%).

Discussion

Given the formation and advancement of the American Mental Health Counseling Association (AMCHA), the introduction of state licensure laws that specifically use mental health counselors as formal nomenclature (Freeman, 2006), and particular certifications that have been offered in clinical mental health counseling, we were somewhat surprised that only 3% of the students who had previously used HSP services identified doing so with clinical mental health counselors. Of course, they may have been confused with names, but to the degree that accurate reporting occurred, the numbers were relatively low compared to other types of counselors.

Obviously, school counselors are very important relative to how students perceive professional counselors. They accounted for the largest portion of users (16%). First impressions are not always necessarily lasting impressions. However, they are cogent and school counselors may set the tone for how these students, for the rest of their lives, perceive others using the word “counselor” in their professional titles. This sentiment was illustrated in qualitative research findings by Wantz, Firmin, Johnson, and Firmin (2006).

Three times as many students indicated having seen a pastoral counselor than a mental health counselor (9% and 3%, respectively). Obviously, we do not know if some students actually meant that they saw an ordained clergy person for personal issues, considering this person to be a pastoral counselor, since they received counseling from him/her and the person was clergy. However, assuming accurate reporting, it suggests that graduate training programs should consider giving additional attention to this domain of counseling. Although courses in pastoral counseling sometimes are seen in religiously-oriented universities (e.g., seminaries, Catholic or Christian colleges), the apparent popularity of their use by students, suggested by the present research, provides evidence that more widespread attention to pastoral counseling is warranted.

Students’ overall perception of professional counselors as being effective is heartening. Particularly welcoming is that only 3% viewed counselors negatively. Social psychology research (Myers, 1994) has shown that a few negative, public incidences can have overshadowing effects on a group’s overall positive characteristics. Fortunately for professional counselors, whatever data might feed negative overall impressions seems to be relatively dormant for students in the present sample.

A general continuum emerged vis-a-vis students’ perceptions of what types of issues are most germane for professional counselors to address. Namely, high responses were provided for general, developmental life issues such as academic problems, depression and career counseling. Moderate responses were provided for problems where direct brain-behavior connections are involved such as ADHD or drug counseling. The lowest responses were provided for types of situations where assessment is warranted, such as personality or intellectual assessment and mental health evaluations. These findings are consistent with overall perceptions that students do not think of counselors in terms of being clinical mental health professionals, but rather as more generic, trained counselors. If the field wishes to advance itself toward the direction of diagnosis, assessment, and treating psychopathology, then data from the present survey would suggest that efforts should be redoubled.

Not all media sources appear to be equal in influencing students’ perceptions of professional counselors. For example, newspapers (13%), magazines (20%), and the Internet (24%) were relatively inconsequential when compared to movies (63%), books (49%) and television (44%). Unfortunately for professional counseling organizations, the most potentially influential sources also happen to be the most expensive ones to target. Nonetheless, if organizations such as the American Counseling Association (ACA), American Mental Health Counselors Association (AMCHA), and the National Board for Certified Counselors (NBCC) are going to impact students’ thinking, then they should target the most efficacious sources. It could be, of course, that the reason newspapers, magazines and the Internet were so relatively non-influential is that few inroads have been attempted in these domains. Advertising in university newspapers, posting and promoting user-friendly web sites, and generating informative articles in popular magazines simply may be an important need for professional counseling advocacy at this time.

In a separate study under development, using qualitative methodology, we are attempting to better flesh-out some of the details relating to these sources of impact on students’ perceptions of professional counselors, particularly the concept of “common knowledge.” Although not surveyed in this study, an influential source proved to be word-of-mouth in perception formations regarding counseling. That is, influences of school, friends, personal experience, physicians, and HSPs most likely have some type of personal connections tied to the medium. Evidently, there is some truth to the adage that word-of-mouth is the best means of advertising—assuming, of course, that the messages being relayed are positive.

In the perceived counselor qualities portion of the survey, it was somewhat disheartening that comparatively few (22%) students indicated they saw professional counselors as competent to diagnose and treat mental disorders. This finding was consistent with other data throughout the survey. Namely, students generally view counselors as professionals who address relatively normal, human development issues rather than psychopathology or more severe disorders requiring assessment, diagnosis and treatment. Again, if the counseling profession wishes to move in the latter direction, then findings from the present research suggest that there is some distance to go. Early acquired school counselor perceptions tended to initiate students’ mindsets regarding what counselors do and they seem not to have moved far from those early perceptions.

In summary, we believe that the present study is a strong first step in a line of needed research regarding just how people come to understand counselors. The findings here do not dictate any action on behalf of professional counseling organizations. However, we believe that the findings indicate in which directions the winds of student perceptions are blowing—and that is data which should be considered when making policy decisions. If counselors are going to move to new, future levels of excellence in terms of public perception, then paying attention to this type of data and giving it due consideration is an important initial component.

Limitations and Future Research

All good research studies report limitations (Murnan & Price, 2004) and we indicate four of them here. First, while our sample had several strengths, including adequate size (Patten, 1998), high response rate (Stoop, 2004), and lack of incentives/bribes for participation (Storms & Loosveldt, 2004), it was taken from a single locale. Some compensation exists, such as students coming from 34 states and the relatively broad cross-section of college majors represented. However, future research in this domain should assess students from a wider variety of institutions such as research universities, state universities, and liberal arts colleges—as well as from diverse locales in the country in order to enhance the study’s external validity (Cohen & Wenner, 2006).

Second, our study had relatively low representation from minority students. This simply was an artifact of the university where the data was collected. Specifically, minorities comprised only 6% of the student body population. Further research should contain samples with larger representations of minority individuals. Additionally, replicating this present study with all minority students would provide an interesting comparison among many points of investigation.

Third, some of the items queried were selected a priori. While we believe them to be of interest and germane to our purposes, future research should broaden questionnaires to include questions that are derived empirically from the research literature. Also, organizations such as the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs should provide input vis-a-vis questions that directly would enhance their efforts in counselor education preparation. The same is true with potential input from NBCC and ACA as they market professional counselors to the general population as well as college students.

Fourth, in retrospect there are two particular changes we would have made to the survey instrument. One is that we would have added a Likert-scale to the first question, querying the perceived overall effectiveness of counselors. While we believe that rating professional counselors with three choices was useful—and we would keep the question—we also would recommend future researchers add a Likert-scale question that is anchored with descriptions, but to which numeric interval-scale values could be assessed. Second, looking back on our questionnaire, we would have asked how many students saw more than one HSP. That is, did they use more than one type of human service professional’s services (e.g., they saw both a rehabilitation counselor and a school counselor). Accounting for multiple uses within the same clientele could provide potentially useful data.

Future research should take the present study and apply it to the population in general. That is, we produced what we believe to be fairly apt representations of perceptions among students—but they do not represent the population at large. Obviously, college students have unique features of adult development that are not necessarily shared by older adults (Foos & Clark, 2003). The very low reported influence that health insurance companies have on college students’ perceptions is one of many examples of where student ideations and those of more middle-aged adults might differ.

And finally, qualitative research is needed in this area. A prime value of questionnaires, such as the present one, is that more voluminous amounts of data can be collected—providing breadth of understanding (Gall & Borg, 2003). Such research also tends to answer “how many” or “what” types of questions (Hittleman & Simon, 2003). Thicker descriptions are needed to help flesh-out some of the details on which survey research was only able to skim. Answers to some of the “why” and “how” questions that the present findings raise can best be answered with follow-up qualitative research methodology (Flick, 2002).

References

Cohen, J., & Wenner, C. J. (2006, May). Convenience at a cost: College student samples. Poster presented at the annual convention of the Association for Psychological Science, New York, NY.

Eriksen, K. P., & McAuliffe, G. J. (1999). Toward a constructivist and developmental identity of the counseling profession: The context-phase-state-style model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 267–280.

Fall, K. A., Levitov, J. E., & Eberts, S. (2000). The public perception of mental health professions: An empirical examination. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 22, 122–134.

Farberman, R. K. (1997). Public attitudes about psychologists and mental health care: Research to guide the American Psychological Association public education campaign. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 28, 128–136.

Foos, P. W., & Clark, M. C. (2003). Human aging. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Flick, U. (2002). An introduction to qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Freeman, L. (2006). Licensure requirements for professional counselors. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Gale, A. U., & Austin, B. D. (2003). Professionalism’s challenges to professional counselors’ collective identity. Journal of Counseling & Development, 81, 3–10.

Gall, M. D., & Borg, W. R. (2003). Educational research (7th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Garrett, J. M., & Eriksen, K.P. (1999). Toward a constructivist and developmental identity for the counseling profession: The context-phase-stage-style model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77, 267–280.

Gelso, C. J., Brooks, L., & Karl, N. J. (1975). Perceptions of “counselors” and other help givers: A consumer analysis. Journal of College Student Personnel, 16, 287–292.

Goodwin, C. J. 92005). Research in psychology: Methods and design (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Hann, F. J., & Bemak, F. (1997). The quest for identity in the counseling profession. Counselor Education and Supervision, 36, 194–206.

Hanson, K. W. (1998). Public opinion and the mental health parity debate: Lessons from the survey literature. Psychiatric Services, 49, 1059–1066.

Hittleman, D., & Simon, A. (2006). Interpreting educational research (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ingham, J. (1985). The public image of psychiatry. Social Psychiatry, 20, 107–108.

Murstein, B. I., & Fonatine, P.A. (1993). The public’s knowledge about psychologists and other mental health professionals. Psychology in Action, 48, 839–845.

Kaufman, A. V., & Raymond, G. T. (1995). Public perception of social workers: A survey of knowledge and attitudes. Arete, 20, 24–35.

Lecroy, C. W., & Stinson, E. L. (2004). The public’s perception of social work: Is it what we think it is? Social Work, 49, 164–175.

Lent, R. W. (1990). Further reflections on the public image of counseling psychology. Counseling Psychologist, 18, 324–332.

Murnan, J., & Price, J. H. (2004). Research limitations and the necessity of reporting them. American Journal of Health Education, 35, 66–67.

Murray, C. M. (1962). College students’ concepts of psychologists and psychiatrists: A problem of differentiation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 57, 161–168.

Myers, D. G. (1994). Exploring social psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Myers, J. E., & Sweeney, T. J. (2004). Advocacy for the counseling profession: Results of a national survey. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82, 466–471.

Patten, M. L. (1998). Questionnaire research. Los Angeles: Pyrczak.

Pistole, M. C. (2001). Mental health counseling: Identity and distinctiveness. ERIC reproduction services. EDO-CG-01-09. 1–4.

Pistole, M. C., & Roberts, A. (2002). Mental health counseling: Toward resolving identity confusions. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 24, 1–19.

Sarafino, W. P. (2005). Research methods. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sharpley, C. F., Rogers, H. J., & Evans, N. (1984). ‘Me! Go to a marriage counselor! You’re joking!’: A survey of public attitudes to and knowledge of marriage counseling. Australian Journal of Sex, Marriage, and Family, 5, 129–137.

Stoop, I. (2004). Surveying nonrespondents. Field Methods, 16, 23–54.

Strong, S. R., Hendel, D. D., & Bratton, J. C. (1971). College students’ views of campus help-givers: Counselors, advisers, and psychiatrists. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 18, 234–238.

Storms, V., & Loosveldt (2004). Who responds to incentives? Field Methods, 16, 414–421.

Tallent, N., & Reiss, W. J. (1959). The public’s concepts of psychologists and psychiatrists: A problem of differentiation. The Journal of General Psychology, 61, 281–285.

Tinsley, H. E., de St. Aubin, T. M., & Brown, M. T. (1982). College students’ help-seeking preferences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 5, 523–533.

Trautt, G. M., & Bloom, L. J. (1982). Therapeugenic factors in psychotherapy: The effects of fee and title on credibility and attraction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 274–279.

Turner, A. L., & Quinn, K. F. (1999). College students’ perceptions of the value of psychological services: A comparison with APA’s public education research. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30, 368–371.

Von Sydow, K., Weber, A., & Reimer, C. (1998). Psychotherapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists in the media: A content analysis of cover pictures in eight German magazines, published 1947–1995. Psychotherapeut, 43, 80–92.

Wantz, R., Firmin, M., Johnson, C., & Firmin, R. (2006, June). University student perceptions of high school counselors. Poster presented at the 18th Annual Enthnographic and Qualitative Research in Education conference, Cedarville, OH.

Warner, D. L., & Bradley, J. R. (1991). Undergraduate psychology students’ views of counselors, psychiatrists, and psychologists: A challenge to academic psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 2, 138–140.

Webb, A. R., & Speer, J. R. (1985). The public image of psychologists. American Psychologist, 40, 1064–1065.

West, N. D., & Walsh, M. A. (1975). Psychiatry’s image today: Results of an attitudinal survey. American Journal of Psychiatry, 132, 1318–1319.

Winston, L., & Stinson, E. L. (2004). The public’s perception of social work: Is it what we think it is? National Association of Social Workers, 49, 164–174.

Zytowski, D. G., Casas, J. M., Gilbert, L. A., Lent, R. W., & Simon, N. P. (1988). Counseling psychology’s public image. Counseling Psychologist, 16, 332–346.

Richard A. Wantz, NCC, is a Professor at Wright State University, and Michael Firmin, NCC, teaches at Cedarville University, both in Ohio. Correspondence can be addressed to Richard A. Wantz, Wright State University, Department of Human Services, 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway, Dayton, OH, 45435, richard.wantz@wright.edu.

Sep 1, 2014 | Article, Volume 2 - Issue 1

Jonathan H. Ohrt, Laura K. Cunningham

Burnout and impairment among professional counselors are serious concerns. Additionally, counselors’ work environments may influence their levels of wellness, impairment and burnout. This phenomenological study included the perspectives of 10 professional counselors who responded to questions about how their work environments influence their sense of wellness. Five themes emerged: (a) agency resources, (b) time management, (c) occupational hazards, (d) agency culture, and (e) individual differences. Implications for professional counselors and future research are discussed.

Keywords: professional counselors, agencies, wellness, burnout, impairment

Wellness promotion focuses on individual strengths and emphasizes holistic growth and development. For example, Myers, Sweeney and Witmer (2000) defined wellness as:

A way of life oriented towards optimal health and well-being in which body, mind, and spirit are integrated by the individual to live life more fully within the human and natural community. Ideally, it is the optimum state of health and well-being that each individual is capable of achieving. (p. 252)

The authors’ definition of wellness alludes to one’s overall well-being. Counselors often advocate holism, exploration of self and self-actualization for their clients (Cain, 2001). Such aspirations may be achieved through a holistic wellness approach (i.e., attending to intellectual, emotional, physical, occupational and spiritual well-being; Witmer & Young, 1996). Therefore, counselors view wellness as an important aspect of overall human functioning. Although this fundamental view has historically been applied to clients, professional counselors themselves now recognize that they also may benefit from a wellness focus (Maslach, 2003).

Professional counseling organizations (e.g., American Counseling Association [ACA]; American Mental Health Counselors Association [AMHCA]; National Board for Certified Counselors [NBCC]) specifically emphasize the importance of counselor wellness and impairment prevention. For example, counselors are ethically required to recognize when they are impaired. The ACA (2005) ethical standards state that “Counselors are alert to the signs of impairment from their own physical, mental, or emotional problems and refrain from offering or providing professional services when such impairment is likely to harm a client or others” (Standard C.2.g). The AMHCA (2010) ethical standards further state that counselors:

recognize that their effectiveness is dependent on their own mental and physical health. Should their involvement in any activity, or any mental, emotional, or physical health problem, compromise sound professional judgment and competency, they seek capable professional assistance to determine whether to limit, suspend, or terminate services to their clients. (Standard C.1.h)

Furthermore, the NBCC (2005) ethical standards indicate that certified counselors discontinue providing services “if the mental or physical condition of the certified counselor renders it unlikely that a professional relationship will be maintained” (Standard A.15).

The Governing Council of the ACA states that “Therapeutic impairment occurs when there is a significant negative impact on a counselor’s professional functioning which compromises client care or poses the potential for harm to the client” (Lawson & Venart, 2005, p. 3). In 2003, this council became proactive in addressing the issue of counselor wellness by creating a task force on counselor wellness and impairment. The task force seeks to educate counselors about impairment prevention, promote resources for prevention and treatment of impaired counselors and to advocate within ACA and its division to address the broader issue of counselor impairment. As a result, they have distributed information on risk factors, assessment, resources and wellness strategies. Thus, a wellness focus is essential for professional counselors to prevent impairment and provide effective counseling services to clients (Witmer & Young, 1996).

Unfortunately, professional counselors encounter multiple factors that threaten their wellness (Lawson, 2007). For instance, counselors are at a particularly high risk for burnout due to the intense and psychologically close work they do with clients (Skovholt, 2001). Although there are many definitions of burnout, Pines and Maslach (1978) described it as “a condition of physical and emotional exhaustion, involving the development of a negative self-concept, negative job attitude, and loss of concern and feelings for clients” (p. 233). Additional consequences of burnout may include low energy and fatigue, cynicism towards clients, feelings of hopelessness and being late or absent from work (Lambie, 2006). When counselors fail to address burnout it can lead to impairment. Counselors also may experience occupational hazards such as compassion or empathy fatigue and vicarious traumatization (Figley, 2002; Lawson, 2007; Stebniki, 2007). Stebniki (2007) defined empathy fatigue as a state wherein counselors are exhausted by their duties because of their constant exposure to the suffering of others, which induces feelings of hopelessness and despair. Similarly, vicarious traumatization occurs when a counselor becomes emotionally impaired due to being exposed to an accumulation of traumatic stories from multiple therapy sessions (McCann & Perlman, 1990). Therefore, the actual nature of counselors’ work is a potential threat to their ability to be well.

In addition, environmental factors in counselors’ work settings also may be detrimental to their wellness (Ducharme, Knudsen, & Roman, 2008; Knudsen, Ducharme, & Roman, 2006; Vredenburgh, Carlozzi, & Stein, 1999). In a survey that included 501 professional counselors, Lawson (2007) found that those working in community agencies experienced higher levels of burnout and compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatization than those working in private practice. Agency variables that are associated with burnout include: work overload, low remuneration, lack of control over services, unsupportive or unhealthy work peers and ineffective or punitive supervisors (Lloyd, King, & Chenoweth, 2002). For example, low remuneration is a specific concern in many Southeastern states. Lambie and Young (2007) offered the following example of a work environment in a specific agency: “an employee assistance program in this area requires its counselors to conduct sessions for 35 clients a week…the counselor in such an organization faces stresses and work hours similar to a first year lawyer in a large firm, without the mitigating effects of financial compensation” (p.101). Additional stressors stem from nonprofit agencies’ dependence on government and state funding sources to operate. Agency compliance with government and state policies to maintain funding often require administrations to focus on the “bottom line,” sometimes to the detriment of client services and employee wellness (Rupert & Morgan, 2005). Counselors who experience such stressors are at serious risk for burnout. Nevertheless, counselors are ethically expected to avoid burnout because it ultimately reduces the quality of services provided to clients, compromises client care and creates potential for harm to the clients (Lawson & Venart, 2005).

Leaders in the counseling profession strongly encourage counselors to be proactive in maintaining their own wellness and self-care. Counselors need to “fill the well” of their own sense of well-being continually, so they can “pour it out” for their clients (Shapiro, Brown, & Biegel, 2007). For example, Lawson (2007) reported that counselors who endorsed 15 highly valued career sustaining behaviors scored higher on compassion satisfaction and lower on burnout. However, despite individuals’ efforts to maintain a wellness lifestyle, the work environment may have a significant role in impeding or supporting wellness efforts. If the work environment does not allow for rejuvenation, or if wellness is not valued, employees (counselors) may become distressed and impaired (Maslach, Leiter, & Schaufeli, 2008). Witmer and Young (1996) suggested that counselor education programs promote and model wellness for their students so they can prepare themselves to make lasting changes in their life to reduce the risk of impairment. Further, if counselors create an individual sense of wellness, they can advocate for their personal well-being in the agency and redirect energies towards organization wellness (Lambie & Young, 2007).

Previous authors suggested that the agencies in which counselors work can help to create wellness environments that contribute to counselors’ overall functioning. For example, Witmer and Young (1996) posited that counselor education programs, employing organizations and regulatory boards should develop systemic preventative wellness protocols to prevent counselor impairment. Their recommendations to agencies included equally distributing the most difficult cases, providing employee assistance programs that include family counseling, adequate peer support, and supervision and team building exercises. Stokes, Henley, and Herget (2006) offered some concrete suggestions to increase wellness including healthy food options, on-site exercise facilities, smoke-free environments, break stations away from the work areas, wellness challenges, support groups, social activities, health risk assessments, self-care information, employee counseling, financial incentives for long term employees and conflict resolution training for supervisors. Further, Lambie and Young (2007) recommended that mental health agencies reduce stress and promote wellness among their employees (counselors) by reducing paperwork and cutting “red tape,” adopting a collaborative management style, improving interpersonal relationships and teamwork, developing ways to reduce role stress, helping counselors grow on the job (e.g., professional development) and improving environmental conditions.

Although the potential hazards related to counselor’s work have received some attention (Gaal, 2009), there is limited research about how counselors conceptualize their wellness in relation to the influence of their work environment. Thus, the purpose of this exploratory study was to gain a greater understanding of how counselors experience wellness and how their work environment influences their sense of wellness. A qualitative phenomenological approach was the most appropriate method to implement because we were seeking to understand the participants’ lived experience of the phenomena (Creswell, 2007). Following the phenomenological tradition, we sought to uncover the central underlying meaning of their experience by reducing data, analyzing specific statements, searching for all possible meanings and creating meaning units (Creswell, 2009). Thus, we developed two research questions. The first question was, “How do you relate to the concept of wellness as a professional counselor?” and the second question was, “How do you perceive your agency influences your sense of wellness?” The first open-ended question was designed to gain information on each of the counselors’ thoughts about wellness and how they interpret the concept. The second question was designed to obtain information about how they believe their work environment affects their sense of wellness.

Method

Research Team

The research team consisted of two counselor educators who at the time of the study were doctoral students at a university in the southeastern U.S. The first author is a Caucasian male and the second author is a Caucasian female. The first author has previous work experience in a residential treatment setting and in a secondary school setting where he experienced a high level of turnover and burnout among the staff. The second author has previous work experience in a variety of agency settings and experienced different levels of emphasis on wellness in each agency. She became interested in researching in this area to assist counselors in the field. Both authors believe a wellness focus is important for professionals in the helping professions. Furthermore, the authors believe that one’s work environment affects each counselor’s ability to be well.

Procedure

Prior to facilitating the interviews and focus groups, we obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) to conduct the study. Next, we recruited the 10 participants through a mixture of criterion-based and snowball-sampling strategies (Teddlie & Yu, 2007). The criterion included contacting counselors or agency directors who were currently or very recently employed at mental health agencies in a southeastern state. The snowball strategy included contacting individuals from the first and second authors’ previous employers, e-mailing invites on group servers for counselors who are alumni from a university that educates counselors and through following up recommendations from other counselors. After we secured participants for the study, we obtained informed consent and confirmed dates for the interviews and focus group.

Participants

The sample included seven female and three male professional counselors whose ages ranged from 25 to 53. Seven of the counselors were Caucasian, one counselor was of Indian descent, one was Latino, and one was of Middle Eastern descent. Two participants were employed by an agency that provides palliative care by way of in-home visits. One participant was a clinical director of an adolescent residential unit. One was previously a clinical director of a domestic violence shelter and a community counseling clinic. One participant worked in a behavioral hospital while another participant worked in an inpatient facility and previously in a residential setting. Three of the participants worked in a university-based clinic. Three counselors were present in the focus group interview and seven counselors were interviewed individually on separate occasions. See Appendix for pseudonyms and demographics.

Data Collection

Demographic questionnaire. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire consisting of questions about their age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, years in the field and work setting prior to participating in the interviews.

Individual interviews. The second author facilitated individual, semi-structured interviews with seven of the participants. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. The interview started with the interviewer explaining the purpose of the study and then posing the first question: “How do you relate to the concept of wellness as a professional counselor?” Once this area was completely explored between the researcher and the interviewee, the researcher posed the second question: “How do you perceive your agency impacts your sense of wellness?” The researchers used follow-up, open-ended questions to elicit significant depth for each of the questions.

Focus group. The focus group included three counselors at a university-based counseling clinic and was facilitated by the second author. Prior to the group, the researcher reminded the interviewees about confidentiality and its limitations. The group lasted approximately 90 minutes and followed the same protocol as the individual interviews.

Data Analysis

After completing the interviews, we transcribed the audio-recorded sessions. All identifying information of the participants and location of employment were altered to maintain confidentiality. Next, the first and second authors read through transcripts to find initial categories. We employed inductive coding to devise categories that represented the overall essential message that was being conveyed in each interview and the focus group. The coding categories that emerged were recorded as well as thoughts about possible relationships between the categories (Glesne, 2006). Next, using the qualitative research software ATLAS.ti (Muhr, 2004), we loaded the documents and reduced the data using a chunking method, which requires the researcher to highlight sections of the transcription and assign codes or categories. Finally, we numbered the code list and noted connections among the interviewees’ coded chunks. This procedure consists of the researcher reviewing the codes to determine if a pattern, theme or relationship occurs (Glesne, 2006).

Verification Procedures

We implemented multiple verification procedures in order to ensure the trustworthiness of the study (Creswell, 2008). First, we performed member checks with participants to verify that the themes developed captured the essence of their experience. We addressed the threat of subjectivity through revealing our positionality and attempting to view information as objectively as possible. Additionally, we employed a peer-debriefer who continuously asked the primary author questions about the study, reviewed the relationship between the data and the research questions and reviewed the accuracy of the data analysis in comparison to the transcriptions.

Findings

In this study, we conducted seven individual interviews and a focus group to explore wellness for professional counselors in various mental health agencies. From the two research questions, “How do you relate to the concept of wellness as a professional counselor?” and, “How do you perceive your agency influences your sense of wellness?” five themes emerged: (a) resources, (b) time management, (c) occupational hazards, (d) agency culture, and (e) individual differences. We discuss each theme with thick, rich descriptions.

Agency Resources

Resources within the agency appeared to be a common theme that influenced participants’ sense of wellness. Participants consistently discussed areas such as salary, staff coverage and workloads as barriers to wellness. For example, participants discussed how financial compensation affected their feelings of being valued as well as their means to do things to maintain wellness. One participant, Anne, explained, “I am a 37-year-old woman who has to live with a roommate… I’m paid half of what nurses [at the same facility] are paid for the same amount of time.” When asked how she handled being paid less than other helping professionals, Anne responded, “I commiserate with other people in the field about being underpaid and undervalued. I can’t beat my head against a wall.” Another participant, Brian, discussed how his salary often impeded his ability to engage in wellness activities:

One of the struggles I had at the beginning was pay. Because it didn’t afford me, literally, the chance to do things to take care of myself, that I wanted to do to take care of myself. So if I had a weekend I couldn’t take a trip to the beach for the weekend. It had to be a quick jaunt and back because I couldn’t afford a hotel.

Resources also included counselor workloads, specifically in terms of how many clients each counselor had to see a day to maintain reimbursement policies. Brian discussed the lack of funding and explained that agencies must work “bare bones…skeleton crew basically.” One participant, Helen, commented on her caseload:

Money can drive a lot of things. Like the choices that you could make [before reimbursement] were more about the clients and what was needed, or what you wanted to try, and then you know Medicaid or other external forces enter, and then decisions have to be made on a different basis. The number of people you would even take would change. [before Medicaid]… There was a lot of flexibility, there was no external pressure to take a certain amount of clients and then there were great conversations and the ability to envision what you should do, and there was the time do it, and there was opportunity to review what you have done, and build the relationships and get feedback on your work, and whereas now, you have put in the time and you have to make the numbers and you lose the time to create relationships or talk about what you are doing.

Similarly, Brian discussed how large caseloads and working with clients back-to-back affected his performance when stating:

Basically, it took away from the services I was able to offer. But most of all it took away from me. You know my energy level, and just across the board I wasn’t able to do all of the things you would like to do as a quality counselor like planning…often it was sort of on the cusp.

Participants described the various resources within their agencies that influenced their sense of wellness. They identified the lack of resources as a barrier to their wellness, which also affected the quality of client care and enthusiasm for their work.

Time Management

Participants discussed time constraints as barriers to their wellness and their ability to maintain optimal performance with clients. They mentioned heavy caseloads as well as administrative duties and paperwork requirements as obstacles to their wellness that also reduced the quality of client services. Additionally, they believed that there was not adequate time for other important aspects of their development, such as supervision. One participant, David, discussed his frustration with not being able to sufficiently prepare for sessions, stating, “there was kind of this disconnect with how long it took to prepare for a session to do it right, or how long it would take to do a group, and to do it right.” He further proposed that the problem may be lessened even without reducing the caseload; “maybe it’s not about the number of clients as much as, maybe it’s just about a scheduling thing too, if you could just spread these clients out, thin enough.”

Participants also discussed administrative duties such as paperwork as wellness barriers that take away from the true meaning of their work. For instance, David stated that, “what was most stressful wasn’t working one-on-one with clients, it was just the amount of paperwork and catch up. You literally feel like you’re running a marathon when you walk in the room.” Brian described the draining effects of paperwork by stating, “I found myself very disenchanted because the work that I wanted to do was with people and often I found I was just doing documentation.”

Finally, participants discussed the importance of making time for appropriate supervision and consultation in maintaining their wellness. For example, when comparing an agency where she felt greater wellness to her previous agency, Fatin stated that the difference is:

The support and the peer consultation, and the time to do that. The level of respect is much higher. There is respect for the administrator; you can approach her with feedback. [There are] high ethical standards and consulting, and the open-door policy. Just makes it so you never feel worried that you will make a mistake, because a lot of people are holding you up.

When talking about the need to differentiate client staffing from clinical supervision, Brian explained that supervisors often, “don’t do supervision with their employees…or supervision is staffing. It’s the same.” He further explained, “Ideally, you have a sit-down with a person and do supervision. So they have a chance to talk about how they’re feeling, the problems they are having, in a safe place to do that.” He conceded that time constraints often hinder this process because, “there’s a lot of crisis and things come up at any given moment. So, you have a schedule, but something trumps it very quickly.” David discussed the benefits of having a positive supervisor who made time for clinical supervision with him, stating:

It was a really important part of me so when I was getting close to burnout or when I was stressed out or in a funk or whatever, I could talk to him and that kind of supervision process which was more than just once a week for an hour. It was more of an as needed kind of a thing and was very, very helpful. It was more than just clients, so it was very helpful for personal growth and so I was totally happy to have that.

Participants described time constraints as significant barriers to their wellness and consequently their ability to provide the best care to clients. However, they also discussed how access to human resources (e.g., supervisors) can positively influence their sense of wellness and development.

Occupational Hazards

A second theme that emerged was occupational hazards. This theme involved the psychologically intense characteristics of the work itself that threaten wellness and included concepts such as empathy fatigue, vicarious traumatization, depersonalization, lack of meaning and wounded healing. Participants discussed the challenges of helping difficult clients while attempting to maintain their own wellness.

One participant, Peter, discussed his struggle to not personally take on too much of the clients’ concerns. He stated that:

I think the biggest challenge that I’ve faced, and I can’t say this challenge is gone to this day, is that I took on a lot of my clients’ stuff. You know, you hear as a counselor you develop empathy for your clients with their challenges and their stories and experiences can be very traumatic and you know can be very impactful. So I think the biggest thing that I had that was impactful is I feel I would take on a lot and I would feel a lot more of what others struggled to face, as opposed to be there in the moment and then walk away from it… That was something, if you think about wellness as this bubble around me and that bubble keeps me from taking on too much of people’s stuff and keeps me mentally and personally safe, then my wellness was gone, the bubble was gone.

Another participant, Anne, discussed the burden that builds when occupational hazards are ignored by the agency and/or supervisors:

A lot of vicarious trauma, grief trauma left unprocessed. When a patient dies it is like—okay next. My administrator actually said that we assume you are coming in with the clinical skills and you will take care of yourself with that. There is no facilitative process or it is not acknowledged in our agency—that it could be happening to us as counselors. We are not given a moment to have that time. [The administrators say] be sure your taking care of yourselves out there—it is sort of you take care of yourself out there.

Yet another participant, David, discussed how the quick client turnaround in the inpatient facility led him to question the value and meaning in his work when he stated:

It was a lot of treat and street, so in other words they come in, you’re basically working on discharge paperwork from the first day you meet them, so you are already thinking about where they need to go…I mean they had lost everyone else in their lives and they felt isolated and alone, so the relationship was incredibly crucial and I think most people would agree that the relationship is the most important part of the counseling process, and you can’t build a relationship if basically when they are coming in you are looking at the chart trying to get the form filled out and trying to get them out the door because either insurance won’t pay or it’s a bed that needs to be emptied out so it can be filled with someone who can maybe last longer.

David went on to discuss his resulting emotions:

There is almost like this shame/guilt you are kind of feeling or struggling with where you feel like you can’t seem to get anywhere, or I am not doing anything, or what am I doing…Am I helping?…Does this matter? And I think that once you have lost that meaning in your work, that passion for what you are doing then it just kind of all, it’s a sinking ship at that point and wellness is just kind of out the window, you just get frustrated.

Participants also discussed the potential setbacks that can occur when professional counselors over-identify with their clients (e.g., wounded healer). Helen comments on how unfinished business unfolds in an agency:

It isn’t quite a straight line. In other words, it is whatever the underlying energy of the agency that draws people in. If people come and then they go, they may not relate to it, but those people who stay for a while, for [more than] three years, that is an issue. You have to constantly reflect back ‘why am I here?’ What is it about this job that has pulled me here and what is it that I need to learn. I think you could stay in the field and never reflect or heal from anything.

One participant, Romie, who also does clinical supervision, discussed the importance of processing empathy fatigue and often spends her time processing the “heaviness of the work.” She responded that “managing the occupational hazards is a matter of keeping the counselors happy…if they are happy and they feel good, and if they feel rewarded in their work they are going to produce and stay.”

Participants discussed that intense and emotionally close work they do with clients is a potential barrier to their wellness. They alluded to the need to set personal boundaries while still finding meaning in their work. Additionally, participants discussed needing time to process the emotions that may arise.

Agency Culture

The next theme that emerged was agency culture. The participants expressed that the messages the administration convey as well as the morale of the agency often influence their sense of wellness. Participants discussed wanting to feel valued and respected by their agency. Sarita stated that she felt valued by her agency. When she was asked how that message was conveyed to her, she replied:

I have been made to feel okay about my developmental level, just…you know…. normalizing my learning level. Everyone can speak up about what their opinion is, even if they are new, you feel part of the team. You know you have been selected for a reason to work here. They have confidence in you and they remind you of that.

Romie paralleled Sarita’s statement:

I happen to believe that wellness comes from the agency itself through feeling valued as an employee, [when] someone hears you in the company and that you have a voice. Having a sense that you say things and that they are respected. Feeling like that if there is anything that the company could do to help, they would. People feel happier, more rewarded and better. What that is in an agency I think is different for each one. It is more of a relationship and personal style.

Brian discussed the value when agencies respect the employees’ need to take care of their family:

Most of the programs that I’ve been in—they are more than willing to let you take care of your family as long as you are doing your job. That’s been the biggest piece I think from a wellness standpoint is the understanding of that from the top.

Participants also discussed how the overall morale of the agency and coworker relationships influence their sense of wellness. For example, Helen commented on how one of her previous places of employment communicated messages of wellness through promoting coworker relationships:

A lot that has to do with the attitude with the people running the place, what they valued, that fact they were invested in relationships. They realized we have to have connection with each other in order to give support to do the work here.

Similarly, Peter discussed how he believed staff cohesion plays a role in wellness:

My experience is that when there is a sense of cohesion, a sense of togetherness and teamwork, I think that people get along better and there’s a natural well, not well, but a natural happiness that goes along with it. My experience, where I’ve had the most stable or happy wellness have been places that encourage staff meals or having staff getaways, or doing events that brought the staff together to enjoy one another…not to work, but just to be around one another and enjoy one another and support one another.

Participants also discussed how agency directors and supervisors directly advocate for self-care. Catherine commented about self-care and wellness:

There is an encouragement for self-care. It is double-binded, you have to get your stuff done, but you know it is like it is Friday, let’s go home. They encourage each other to work less and have fun. Other places (agencies) had more pressure to get it done. There is a consciousness of balance.

Peter also discussed positive feelings when his supervisor supported his self-care efforts, “There was one day there was an accumulation of things, a combination of feeling sick, but also in the middle of a stressful time…he said go home, have a great day. So he was in support of wellness.” Peter continued, “he understood the job is not always easy and can bring on a lot of stress and he was willing to let us take care of ourselves if we needed to.”

Overall, when the agency promoted the respect and value of professional counselors and encouraged counselors to have a voice and affect change, it promoted the counselors’ own sense of wellness. Furthermore, sensing an investment in work relationships and promoting a work-life balance influenced the wellness of these counselors.

Individual Differences

The final theme that emerged involved the different perspectives of the participants and how that influenced their feelings of wellness. Two participants from the same agency held very different feelings about how their agencies influenced their sense of wellness. Jill felt very positive about her agency and spoke of the many financial incentives and freedoms allotted and that the agency’s independent scheduling fit her. Anne also mentioned the same financial incentives, but believed that she received negative mixed messages and that her wellness was being negatively affected by the same agency. Conversely, Jill, who felt positive towards her agency, noted, “No one had to tell me to take care of myself.” David also expressed that wellness is often left up to the individual; when speaking about one of his agencies he stated, “it wasn’t really like it was a place of wellness. Wellness is something that happened, or self-care happened long after you left.” Romie responded about her intentionality with wellness:

Personally, what I do is many things. I exercise; I make sure I get plenty of sleep. I take time for myself when I need to. I will do yoga and meditate and do a lot of reading and I am highly spiritual. I have a wonderful home-life, a very supportive love-mate in my life. I am really in a good place.

Throughout the interviews, the participants discussed very different values in terms of their wellness. Some of the participants mentioned spiritual practice and journaling as being important in maintaining wellness. Others expressed time with family as being most important, whereas others discussed setting clear boundaries or finding meaning in their work.

Other participants discussed how wellness initiatives within their agencies often seemed inconvenient to them. When talking about a discounted gym membership that was offered, Brian viewed the offer as superficial, saying “in my experience, most of what they offer in terms of wellness is, in my experience, is somewhat superficial.” He further stated, “Very few people are able to utilize the gym membership because of the hours they work and where it’s located and the cost is still too high for the employees.” Peter discussed the positives and negatives of a wellness initiative:

The book was a 40 week-by-week event where you learned about wellness…physical, mental, spiritual; all these different components. The problem was they had these events that took place scattered all over the district and so for anyone to attend them, they would have to drive half an hour to 45 minutes to attend them and which if you’re trying to have a good basis for wellness, then having people drive 45 minutes after a long day of work is not a good place to start for that.