Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Wesley B. Webber, W. Leigh Atherton, Kelli S. Russell, Hilary J. Flint, Stephen J. Leierer

The COVID-19 pandemic and efforts to manage it have affected mental health around the world. Although early research on the COVID-19 pandemic showed a general decline in mental health after the pandemic began, mental health in later stages of the pandemic might be improving alongside other changes (e.g., availability of vaccines, return to in-person activities). The present study utilized data from a mental health service intervention for individuals at a southeastern university who were exposed to COVID-19 following the university’s return to in-person operations. This study tested whether time period (August–September 2021 vs. January–February 2022) predicted individuals’ likelihood of being mild or above in depression and anxiety ratings. Results showed that individuals were more likely to be mild or above in both depression and anxiety ratings during August–September of 2021 than January–February of 2022. Suggestions for future research and implications for professional counselors are discussed.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, depression, anxiety, university

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19), first detected in 2019, spread globally at a rapid pace, with the first confirmed case in the United States occurring on January 20, 2020, in the state of Washington (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023). By April 2020, the United States had the most reported deaths in the world due to COVID-19. It was not until December of 2020 that the first round of vaccines, authorized under emergency use authorization, was made available (Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2021). As of October 2022 in the United States, a total of 97,063,357 cases of COVID-19 had been reported, from which there were 1,065,152 COVID-19–related deaths (CDC, 2023). A reported 111,367,843 individuals aged 5 and above in the United States had received their first booster dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of October 2022 (CDC, 2023). Previous research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic and efforts to manage it (e.g., lockdowns, quarantine, isolation) had negative effects on mental health in the United States and internationally (Huckins et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020; Son et al., 2020). Based on the extended duration of the pandemic and changes that have occurred during it (e.g., vaccine availability, lessening of initial social restrictions), more recent research has investigated possible changes in mental health in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fioravanti et al., 2022; McLeish et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). The present study adds to this literature by exploring whether psychosocial symptomatology (i.e., depression and anxiety) at a university in the Southeastern United States differed in individuals exposed to COVID-19 during August–September 2021 as compared to individuals exposed to COVID-19 during January–February 2022 (following the university’s return to on-campus operations in August 2021).

Challenges to Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, conceptual and empirical research has focused on ways in which the pandemic and associated stressors might impact mental health (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2020; Marroquín et al., 2020; Şimşir et al., 2022). Implementation of lockdowns to deter spread of the virus led to concerns that social isolation might have severe impacts on mental health (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2020). This hypothesis was empirically supported, as stay-at-home orders and individuals’ reported levels of social distancing were positively associated with depression and anxiety (Marroquín et al., 2020). Individuals’ views on the COVID-19 pandemic evolved quickly at the outset of the pandemic, and perceptions of risk were shown to increase during the pandemic’s first week in the United States (Wise et al., 2020). Growing awareness of the dangers of the virus likely had deleterious effects on mental health; Şimşir et al. (2022) found through a meta-analysis that fear of COVID-19 was associated with a variety of mental health problems. Mental health was also negatively affected by stigmatization associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, as was the case for those exposed to COVID-19 while at their place of work (Schubert et al., 2021). Such stigmatization associated with COVID-19 exposure was found to increase risk for depression and anxiety (Schubert et al., 2021).

The lockdowns and social distancing measures that accompanied early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic also resulted in changes to routines that likely impacted mental health. For some individuals facing lockdowns or other disruptions to typical routines, reductions in physical activity occurred. Individuals who reported greater impact of COVID-19 on their level of physical activity showed greater symptoms of depression and anxiety (Silva et al., 2022). Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, based on people’s increased time spent at home and their concerns about COVID-19 developments, some people increased their media usage (e.g., news outlets, social media). Such increases in media usage were associated with decreases in mental health (Meyer et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic had less significant impact on mental health for those with greater tolerance of uncertainty (Rettie & Daniels, 2021) and psychological flexibility (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020). Thus, some individuals were uniquely suited to face the many changes and stressors brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

One population that previous research has identified as being especially at risk for negative mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic is college students (Xiong et al., 2020). For college students, the COVID-19 pandemic occurred alongside other stressors known to be typical for this population such as adjusting to leaving home, navigating new peer groups, and making career decisions (Beiter et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019). Thus, for many college students, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted a period of life already filled with many transitions. For example, shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic began, many college students were forced to leave their dormitories and peers as universities transitioned to online delivery of classes (Copeland et al., 2021). Xiong et al. (2020) found through a systematic review that college students were especially vulnerable to negative mental health outcomes at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic as compared to others in the general population. In the United States, college students’ reported degree of life disruption due to the COVID-19 pandemic was positively associated with depression at the conclusion of the spring 2020 semester (Stamatis et al., 2022). During fall 2020, COVID-19 concerns and previous COVID-19 infection were each found to be associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety among U.S. college students (Oh et al., 2021). Overall, previous research has supported the notion that changes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic had general negative effects on mental health in the general population and in college students specifically.

Changes in Psychosocial Symptomatology Across the COVID-19 Pandemic

Although research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic introduced unprecedented challenges and stressors that were associated with mental health problems, another important direction for research has been to characterize overall changes in psychosocial symptomatology as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed. Such research is important given that individuals might psychologically adapt to constant COVID-19 stressors or might benefit from changes that have occurred as the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed (e.g., vaccine availability, lessening of societal restrictions). Initial longitudinal studies comparing individuals’ symptomatology before the COVID-19 pandemic and after its beginning showed that mental health deteriorated after the COVID-19 pandemic began (Elmer et al., 2020; Huckins et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020). Prati and Mancini (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of 28 studies that used longitudinal or natural experimental designs and found that depression and anxiety showed small but statistically significant increases after implementation of the initial lockdowns in response to COVID-19. The various changes to ways of life associated with the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to result in a general deterioration in mental health.

Previous research has also explored possible changes in mental health beyond those that were observed in the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. In support of the notion that individuals adapted to changes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, Fancourt et al. (2021) found that anxiety and depression decreased across the initial lockdown period in the United Kingdom. In contrast, Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. (2020) found that levels of depression and anxiety were higher 3 weeks into the initial lockdown period in Spain as compared to the beginning of the lockdown. Fioravanti et al. (2022) assessed psychological symptoms longitudinally in an Italian sample at three time points—the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and first lockdown (March 2020), the end of the first lockdown phase (May 2020), and during a second wave of COVID-19 with increased societal restrictions (November 2020). Their findings pointed to possible influences of COVID-19 waves and societal restrictions on specific psychosocial symptoms. Specifically, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder all decreased at the end of the first lockdown phase (Fioravanti et al., 2022). However, all symptoms besides obsessive-compulsive disorder significantly increased from the end of the first lockdown phase to the second wave of COVID-19 (Fioravanti et al., 2022).

Recent research on mental health among college students in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic has also focused on possible mental health changes over time (McLeish et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022). Tang et al. (2022) reported reductions in anxiety and depression in a longitudinal study of university students in the United Kingdom between a first time point (July–September 2020, after the end of lockdown) and a second time point (January–March 2021, when vaccinations were becoming available). In contrast, McLeish et al. (2022) found through a repeated cross-sectional study that depression and anxiety among students at a specific university increased from spring 2020 to fall 2020, with the increases being maintained in spring 2021. The authors noted that vaccines were not widely available at the university until the end of spring 2021 (McLeish et al., 2022). Thus, recent studies have found mixed results as to whether psychosocial symptomatology improved over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. These discrepancies may be due to contextual differences between studies (e.g., differences in data collection time periods, availability of vaccines, or levels of COVID-19 restrictions being implemented during data collection).

The Present Study

The present study was conducted based on the need for continued research on mental health across the evolving COVID-19 pandemic and based on previous conflicting findings on possible mental health changes in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given previous research showing detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population and in college students, the present study utilized data from a university population. Specifically, an archival dataset was used in the present study to examine data collected during 2021–2022 at a university in the Southeastern United States and to test whether time period would predict severity of depression and anxiety symptoms. Individuals in the study had been exposed to COVID-19 between August–September 2021 or between January–February 2022 and had requested a mental health contact during university-conducted contact tracing. These two time periods corresponded to surges in COVID-19 cases at the university due to the delta and omicron COVID-19 variants, respectively. August–September 2021 also coincided with a return to on-campus operations at the university and therefore captured psychosocial symptomatology at the beginning of a significant transition in the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., a return to organized in-person activities on a college campus during the evolving pandemic). This study was designed to answer the following research questions:

- Among those requesting mental health contact after COVID-19 exposure, was the likelihood of having at least mild depression symptoms different for those whose contact occurred between August–September 2021 as compared to those whose contact occurred between January–February 2022?

- Among those requesting mental health contact after COVID-19 exposure, was the likelihood of having at least mild anxiety symptoms different for those whose contact occurred between August–September 2021 as compared to those whose contact occurred between January–February 2022?

Method

Design

A retrospective research design was used to analyze the possible effect of time period on severity of depression and anxiety symptoms among members of a university population who had been exposed to COVID-19 and requested a mental health check-in. The study used a de-identified dataset obtained from the service providers who completed the mental health check-in. We confirmed through consultation with the IRB that the use of archival, de-identified data does not necessitate IRB review.

COVID-19 Mental Health Check-In Dataset

The archival, de-identified dataset used in the present study was compiled as part of a mental health service occurring between February 2021 and February 2022. Participants in the dataset had tested positive for COVID-19 or been exposed to COVID-19 without a positive test. During university-conducted contact tracing, they were offered and elected to receive a subsequent mental health check-in. Individuals who were contact traced and thereby offered a mental health check-in had become known to contact tracers through one of two routes: (a) they reported their own COVID-19 diagnosis or exposure through a self-reporting mechanism as instructed by the university, or (b) they were reported by another individual as having been diagnosed with or exposed to COVID-19. The dataset used in this study included data collected during the mental health check-ins for those who elected to receive them. This data was collected over the phone and documented in RedCap (a secure web browser–based survey protocol designed for clinical research) at the time of the phone call or within 24 hours. The dataset consisted of data for 211 individuals’ check-ins. For each check-in, the dataset included participants’ demographic information, screening data (for depression, anxiety, and trauma), identified needs of the participant, resources shared with the participant, and the date of data entry.

The present study focused on check-in data for all individuals from the COVID-19 Mental Health Check-in Dataset whose check-in had occurred during one of the two time periods of focus—August–September 2021 or January–February 2022. These two time periods corresponded to surges in COVID-19 cases at the university associated with the delta and omicron COVID-19 variants, respectively. The 149 individuals who checked in during these 4 months represented 70.62% of the total number of check-ins over the 12-month dataset (N = 211), reflecting the surges in COVID-19 cases during these two periods. Of the 149 individuals in the present study, 96 (64.43%) received their check-in during August–September 2021, and 53 (35.57%) received their check-in during January–February 2022. The selection of these two time periods from the larger dataset allowed for comparison of psychosocial symptomatology during comparable levels of COVID-19 infection (i.e., surges associated with two subsequent COVID-19 variants) at comparable points in subsequent academic semesters (i.e., the first 2 months of the fall 2021 and spring 2022 semesters). The present study used only the screening data for depression and anxiety, as the scales for each of these constructs showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > .80).

Participants

The sample in the present study consisted of 149 individuals. The selected individuals’ ages ranged from 17 to 52 (M = 22.21, SD = 7.43). With regard to gender, 67.11% identified as female, 32.21% as male, and 0.67% as non-binary. The reported races of individuals in the study were as follows: 60.4% White, 20.13% African American, 6.71% Hispanic, 3.36% Other, 2.68% Two or more races, 1.34% Middle Eastern, 1.34% Native American, and 0.67% Asian. Some participants preferred not to indicate their race (3.36%). In responding to a question about their ethnicity, 87.25% of individuals identified as not Latinx, 9.40% identified as Latinx, and 3.36% preferred not to answer. With regard to academic level/job title, 32.89% were freshmen, 20.13% were sophomores, 14.09% were juniors, 15.44% were seniors, 7.38% were graduate students, 8.05% were faculty/staff, and 2.01% preferred not to answer. Regarding employment, 53.69% were not employed (including students), 30.20% were employed part-time, 12.75% were employed full-time, and 3.36% preferred not to answer. The relationship statuses of individuals were reported as the following: 87.92% single (never married), 4.7% married, 2.01% single but cohabitating with a significant other, 1.34% in a domestic partnership or civil union, 1.34% separated, 0.67% divorced, and 2.01% preferred not to answer. Table 1 summarizes demographic responses within each of the two time periods and for the full sample.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants responded to seven demographic questions (age, gender, race, ethnicity, academic year/job title, current employment status, and relationship status). They were informed that this information was optional and that they could choose not to answer particular questions.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

|

Demographic

Characteristic |

|

| August–September 2021 |

January–February 2022 |

Full Sample |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

69 |

71.88 |

31 |

58.49 |

100 |

67.11 |

| Male |

27 |

28.13 |

21 |

39.62 |

48 |

32.21 |

| Non-binary |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.89 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Race |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| White |

56 |

58.33 |

34 |

64.15 |

90 |

60.40 |

| African American |

23 |

23.96 |

7 |

13.21 |

30 |

20.13 |

| Hispanic |

8 |

8.33 |

2 |

3.77 |

10 |

6.71 |

| Other race |

1 |

1.04 |

4 |

7.55 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Two or more races |

4 |

4.17 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

2.68 |

| Middle Eastern |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Native American |

1 |

1.04 |

1 |

1.89 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Asian |

1 |

1.04 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

5 |

9.43 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not Latinx |

82 |

85.42 |

48 |

90.57 |

130 |

87.25 |

| Latinx |

12 |

12.50 |

2 |

3.77 |

14 |

9.40 |

| Prefer not to answer |

2 |

2.08 |

3 |

5.66 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Academic Year / Job Title |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Freshman |

38 |

39.58 |

11 |

20.75 |

49 |

32.89 |

| Sophomore |

18 |

18.75 |

12 |

22.64 |

30 |

20.13 |

| Junior |

15 |

15.63 |

6 |

11.32 |

21 |

14.09 |

| Senior |

15 |

15.63 |

8 |

15.09 |

23 |

15.44 |

| Graduate Student |

6 |

6.25 |

5 |

9.43 |

11 |

7.38 |

| Faculty/Staff |

4 |

4.17 |

8 |

15.09 |

12 |

8.05 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5.66 |

3 |

2.01 |

| Employment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not Employed (including student) |

62 |

64.58 |

18 |

33.96 |

80 |

53.69 |

| Employed Part-Time |

26 |

27.08 |

19 |

35.85 |

45 |

30.20 |

| Employed Full-Time |

8 |

8.33 |

11 |

20.75 |

19 |

12.75 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

5 |

9.43 |

5 |

3.36 |

| Relationship Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single, never married |

87 |

90.63 |

44 |

83.02 |

131 |

87.92 |

| Married |

3 |

3.13 |

4 |

7.55 |

7 |

4.70 |

| Single, but cohabitating with a

significant other |

2 |

2.08 |

1 |

1.89 |

3 |

2.01 |

| In a domestic partnership or civil union |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Separated |

2 |

2.08 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1.34 |

| Divorced |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.89 |

1 |

0.67 |

| Prefer not to answer |

0 |

0 |

3 |

5.66 |

3 |

2.01 |

| Note. Average age was 21.51 (SD = 6.98) in August–September 2021 group, 23.49 (SD = 8.11) in January–February 2022 group, and 22.21 (SD = 7.43) in the full sample. |

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of depression symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The PHQ-9 has been validated for screening for depression in the general population (Kroenke et al., 2001; Martin et al., 2006). The questionnaire measures frequency of symptoms such as “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless,” and “little interest or pleasure in doing things.” The PHQ-9 uses a 4-point Likert scale to measure frequency of symptoms over the past 2 weeks with the response options of not at all, several days, more than half the days, and nearly every day. Scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 are assigned to each of the four response categories, and a PHQ-9 total score is derived by adding the scores for each of the nine PHQ-9 items. Minimal depression is indicated by PHQ-9 total scores of 0–4, mild depression by scores of 5–9, moderate depression by scores of 10–14, moderately severe depression by scores of 15–19, and severe depression by scores of 20–27. Question 9 on the PHQ-9 is a single screening question assessing suicide risk. Interviewers were trained in appropriate protocol in the event of a positive screen for this question. Cronbach’s alpha for the PHQ-9 in the present study was .86.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7)

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) is a 7-item self-report anxiety questionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The GAD-7 has demonstrated reliability and validity as a measure of anxiety in the general population (Löwe et al., 2008). The questionnaire measures symptoms such as “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge,” and “not being able to stop or control worrying.” The format of the GAD-7 is similar to the PHQ-9, using a 4-point Likert scale to measure frequency of symptoms over the past 2 weeks with response options of not at all, several days, more than half the days, and nearly every day. GAD-7 scores are calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 for response categories and then adding the scores from the 7 items to derive a total score ranging from 0 to 21. Minimal anxiety is indicated by total scores of 0–4, mild anxiety by scores of 5–9, moderate anxiety by scores of 10–14, and severe anxiety by scores of 15– 21. Cronbach’s alpha for the GAD-7 in the present study was .86.

Analytic Strategy

Total scores for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were found to be positively skewed for both groups of participants. Binary logistic regression was therefore an appropriate method of analysis for this dataset, as binary logistic regression does not require normality of dependent variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). For two separate binary logistic regression models, individuals were classified as being either minimal or mild or above in depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) to create binary outcome variables. This choice of cutoff allowed each model (with time period as predictor) to satisfy the recommendation of Peduzzi et al. (1996) that there be at least 10 cases per outcome per predictor in binary logistic regression.

Prior to performing these intended primary analyses to answer the research questions, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether adding control variables to the logistic regression models was warranted. Chi-square tests of independence, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests, Fisher’s Exact tests, and an independent samples t-test were used to test for possible differences between the two time periods in individuals’ responses to demographic questions. In cases in which responses to demographic questions were shown to be significantly different across the two groups, appropriate tests were used to determine whether the demographic responses in question were associated with either of the two intended dependent variables.

Following the preliminary analyses, the intended two binary logistic regressions were conducted to answer the research questions. In the first binary logistic regression, time period was the predictor

(1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) and PHQ-9 depression category was the outcome (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal). In the second logistic regression, time period was the predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) and GAD-7 anxiety category was the outcome (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal). All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 28.

Results

Preliminary Demographic Analyses

Prior to the primary analyses, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether the two groups differed in their responses to demographic questions. Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests and an independent samples t-test were used to test for differences between groups in their responses to the seven demographic questions. Two of the seven tests were statistically significant at Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. Specifically, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact tests found significant differences between time periods on the race (p = .004) and employment (p < .001) demographic variables.

Based on the above significant results for the race and employment variables across the time periods, 2 x 2 tests were conducted to test for differences between specific race responses and specific employment responses across the two time periods. For these 2 x 2 tests, a chi-square test of independence was used when all expected cell counts were 5 or greater and Fisher’s Exact test was used when any expected cell counts were less than 5. To follow up the significant result for race, 2 x 2 tests were conducted for all pairs of race responses in which 2 x 2 tests were possible (i.e., in which there was at least one observation for each of the two race responses at both time periods). These follow-up 2 x 2 tests of responses to the race question across time periods found no statistically significant differences between pairs of race responses across time periods using Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. Follow-up 2 x 2 tests comparing all pairs of responses to the employment question across time periods found two statistically significant differences using Bonferroni-corrected alpha level. A chi-square test of independence showed that individuals were more likely to be employed full-time during January–February 2022 than August–September 2021 as compared to those not employed (including students), X2 (1, N = 99) = 9.29, p = .002. Fisher’s Exact test showed that individuals were more likely to indicate “prefer not to answer” during January–February 2022 than during August–September 2021 as compared to those indicating “not employed (including students),” p = .001.

The statistically significant tests for race and employment across time periods were followed up with additional tests to determine if depression or anxiety category (minimal vs. mild or above for each) was associated with individuals’ responses to the relevant race and employment questions. A Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test showed that depression category was not associated with individuals’ responses to the race question, p = .099. A Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact test also showed that individuals’ anxiety category was not associated with individuals’ responses to the race question,

p = .386. With regard to employment, tests of association were conducted between the intended dependent variables and the specific employment responses that were found to differ between the two groups. A chi-square test of independence showed that individuals’ status as “not employed” vs. “employed full-time” was not associated with depression category, X2 (1, N = 99) = .63, p = .429. A chi-square test of independence also showed that these employment statuses were not associated with anxiety category, X2 (1, N = 99) = .27, p = .601. Similarly, Fisher’s Exact tests showed that individuals’ employment responses of “prefer not to answer” vs. “not employed (including students)” were not associated with depression category (p = .156) or anxiety category (p = .317). These results were interpreted as indicating that the ways in which individuals in the two time periods differed demographically did not have significant impact on the study’s dependent variables of interest. Therefore, binary logistic regressions were conducted with only time period as a predictor of each dependent variable.

Relationship Between Time Period and Severity of Depression Symptoms

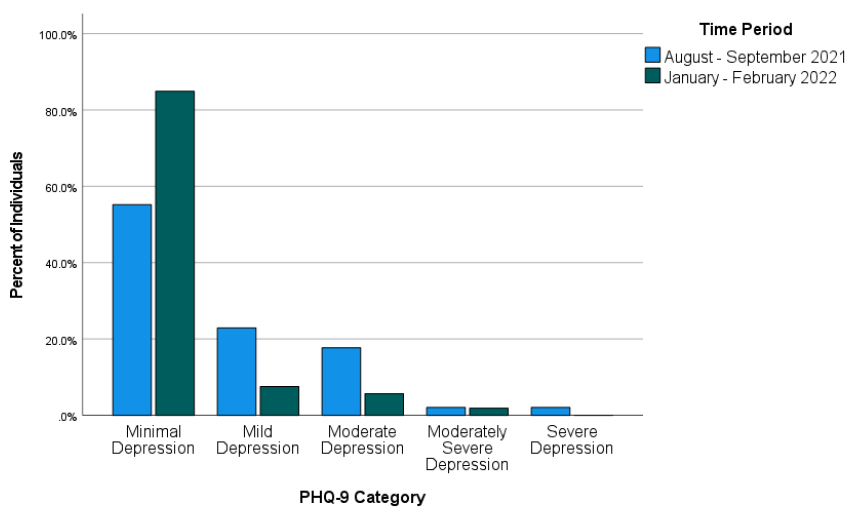

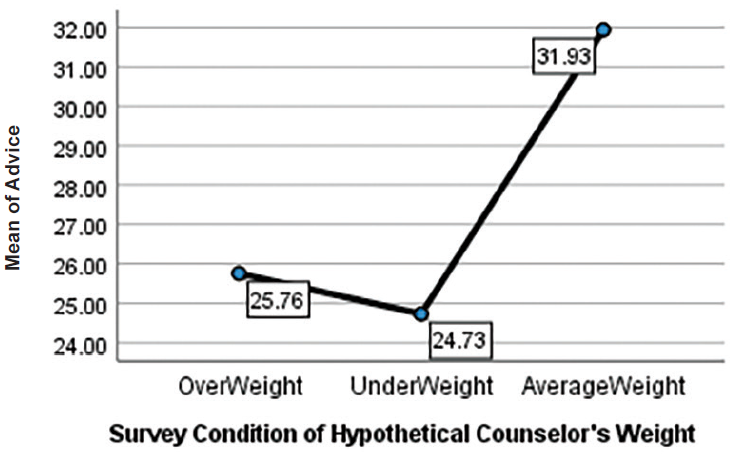

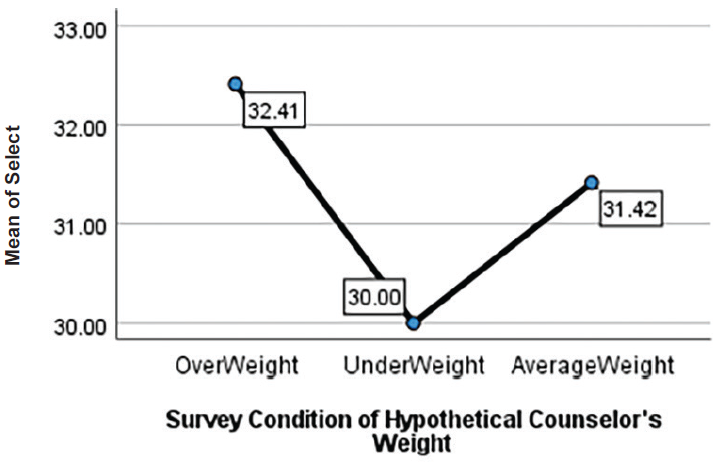

Most individuals in the study were in the minimal depression range on the PHQ-9 as compared to the other four categories. Figure 1 shows the percentage of individuals falling into each of the five PHQ-9 categories during each of the two time periods.

Figure 1

Percentages of Individuals Falling Into Each of the PHQ-9 Categories for Each of the Two Time Periods

Across both time periods combined (August–September 2021 and January–February 2022), 51 individuals (34.23%) were mild or above in depression while 98 (65.77%) were in the minimal range. Binary logistic regression was used to test whether time period predicted severity of depression symptoms. Time period was entered as a predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) of depression (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal depression). The overall binary logistic regression model was found to be statistically significant, χ2(1) = 14.46, p < .001, Cox & Snell R2 = .092, Nagelkerke R2 = .128. In the model, time period was found to be a significant predictor of depression, Wald χ2(1) = 12.17, B = 1.52, SE = .44, p < .001. The model estimated that the odds of being mild or above in depression were 4.56 times higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022 for individuals requesting a mental health check-in following COVID-19 exposure. Specifically, the predicted odds of being mild or above in depression were .81 during August–September 2021 and .18 during January–February 2022.

Relationship Between Time Period and Severity of Anxiety Symptoms

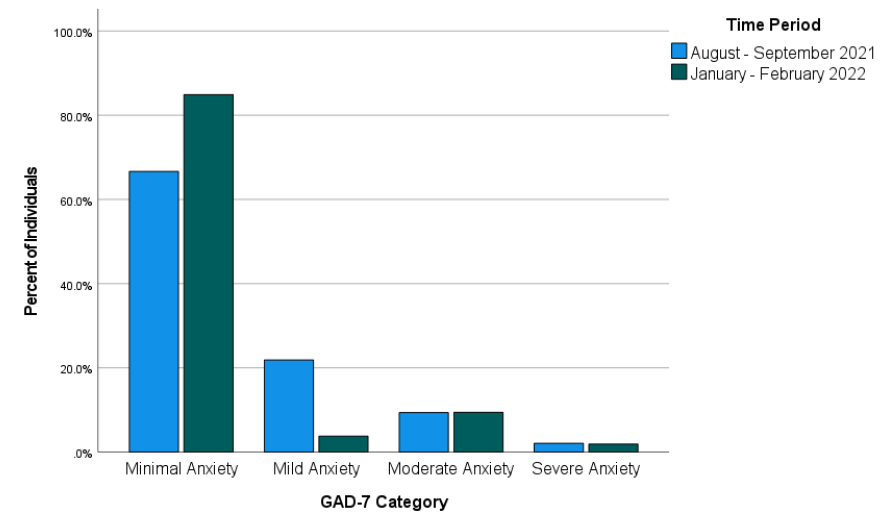

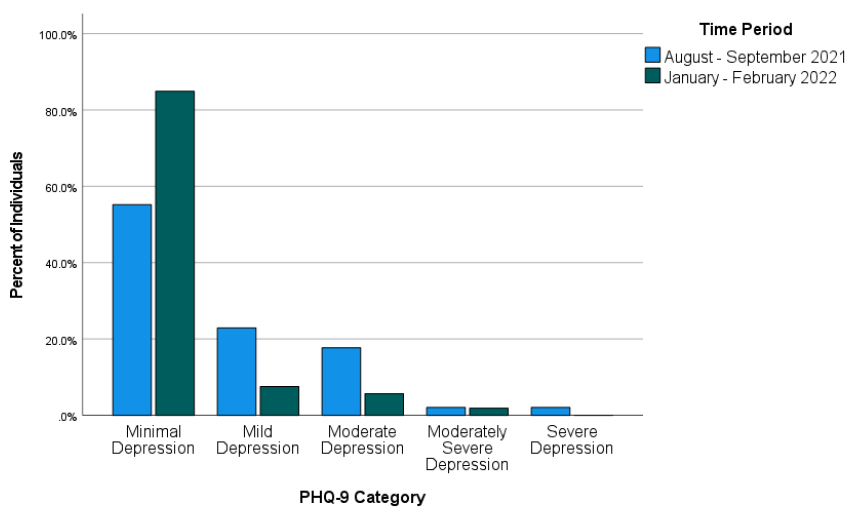

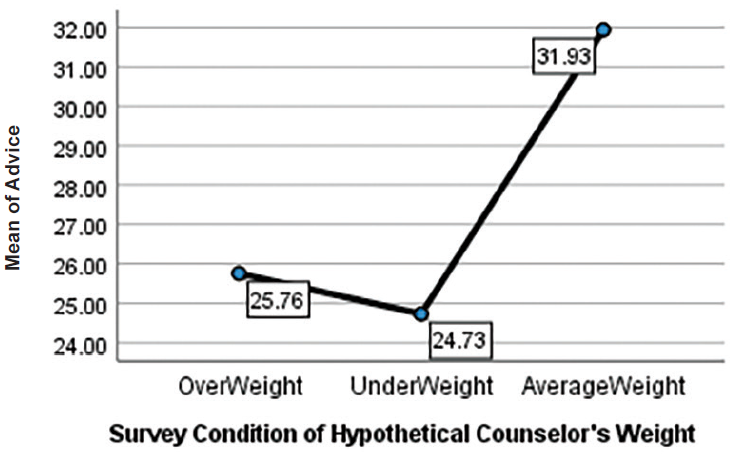

Most individuals in the study were in the minimal anxiety range on the GAD-7 as compared to the other three categories. Figure 2 shows the percentage of individuals falling into each of the four GAD-7 categories during each of the two time periods.

Figure 2

Percentages of Individuals Falling Into Each of the GAD-7 Categories for Each of the Two Time Periods

Across both time periods combined, 40 individuals (26.85%) reported anxiety at levels of mild or above and 109 individuals (73.15%) reported minimal anxiety. Binary logistic regression was used to test whether time period predicted severity of anxiety symptoms. Time period was entered as a predictor (1 = August–September 2021, 0 = January–February 2022) of anxiety (1 = mild or above, 0 = minimal anxiety). The overall binary logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2(1) = 6.16, p = .013, Cox & Snell R2 = .041, Nagelkerke R2 = .059. In the model, time period was a significant predictor of anxiety, Wald χ2(1) = 5.51, B = 1.03, SE = .44, p = .019. Odds of being mild or above in anxiety were estimated by the model to be 2.81 times higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022 for individuals requesting a mental health check-in after exposure to COVID-19. Specifically, the predicted odds of being mild or above in anxiety were .50 during August–September 2021 and .18 during January–February 2022.

Discussion

This study examined whether time period would predict severity of depression and anxiety symptoms in a sample of individuals exposed to COVID-19 at a university in the Southeastern United States. More specifically, the study addressed the possibility that the likelihood of being mild or above in depression and anxiety would differ between two time periods following the university’s return to in-person operations in August 2021. The results of the study showed that the likelihood of being mild or above in depression and the likelihood of being mild or above in anxiety after exposure to COVID-19 were both higher during August–September 2021 than during January–February 2022. This finding is in line with previous research that found improvements in psychosocial symptomatology in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Tang et al., 2022) and in contrast to research that did not find such improvements (McLeish et al., 2022). Based on the results of the present study, it appears likely that factors that differed between the two assessed time periods (first two months of fall 2021 vs. first two months of spring 2022) contributed to the observed difference in likelihood of depression and anxiety symptoms. McLeish et al. (2022) noted that vaccines were not widely available in their study that did not find such differences, while Tang et al. (2022), who did find significant differences, noted that vaccines were available at their second data collection point (January–March 2021). For individuals in the present study, COVID-19 vaccinations were available. Vaccination was strongly encouraged by university administrators following the return to campus, and more individuals on campus were vaccinated in spring 2022 than in fall 2021. Vaccinations might have lessened individuals’ COVID-19 concerns and contributed to more positive psychosocial outcomes during spring 2022 than fall 2021.

Besides vaccinations possibly lessening depression and anxiety symptoms, other environmental circumstances might also have played a role. The two time periods on which this study focused also differed in their proximity to a significant environmental event—a return to in-person operations on the campus where the individuals studied and/or worked. Early research on the mental health impact of COVID-19 highlighted the negative mental health effects of factors such as reduced physical activity (Silva et al., 2022), life disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Stamatis et al., 2022), and social distancing (Marroquín et al., 2020). Therefore, it is possible that symptoms of depression and anxiety in spring 2022 were affected by changes in specific circumstances known to have negatively impacted mental health earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, individuals’ physical activity likely increased because of a return to campus, and they might have perceived less disruption to their lives through being able to resume in-person activities. Although individuals in the present study who were exposed to COVID-19 during the first 2 months after the return to campus might have reaped some benefits from the return to more normal environmental circumstances, they might also have faced a period of adjustment. In contrast, individuals exposed to COVID-19 between January and February 2022 might have been more readjusted and reaped greater benefits from the return to campus, thereby reducing depression and anxiety symptoms.

Implications

This study’s findings on psychosocial symptomatology across time during the COVID-19 pandemic have important implications for the work of counselors. Based on the results of the present study, counselors planning outreach efforts to individuals exposed to COVID-19 should consider that as time passes, these individuals might be more stable with regard to symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, some individuals directly affected by COVID-19 might still be interested in receiving mental health information despite low levels of depression and anxiety. Many individuals in the present study scored as minimal in depression and anxiety but were still interested in receiving a mental health check-in. Thus, counselors should advocate for mental health information and resources to be made available to individuals who are known to be facing stressors related to COVID-19. Counselors should be prepared to have conversations to determine the contextual needs of individuals exposed to COVID-19 rather than relying only on standardized measures of psychosocial symptomatology. For example, counselors working with employees (such as university employees in the present study) should be attentive to the possibility that employees exposed to COVID-19 may be concerned about facing stigma in their workplace due to their exposure (Schubert et al., 2021).

Given that the present study focused on individuals from a university population, the study’s results also have specific implications for college counselors. College counselors should develop approaches to reach students during circumstances that might make traditional outreach challenging. For example, the present study used data from a mental health intervention in which service providers collaborated with university contact tracers to safely provide mental health resources by telephone to individuals exposed to COVID-19. College counselors should be prepared to connect clients with services at a distance. Previous research during the COVID-19 pandemic found that college students were interested in using teletherapy and online self-help resources, particularly if such services were made available for free (Ahuvia et al., 2022).

Besides preparing for flexible modes of service delivery, college counselors should be prepared to deliver interventions most likely to be useful to college students during the COVID-19 pandemic or similar pandemics. Those recently exposed to COVID-19 might benefit from discussing possible fears associated with COVID-19, experiences of stigmatization they might have experienced due to their exposure, and ways to maintain mental health during any period of quarantine or isolation that might be required. Those not recently exposed to COVID-19 might instead benefit from interventions that address other issues that might have resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic or societal responses to it. For example, if circumstances associated with the COVID-19 pandemic led to reductions in a client’s amount of exercise, a counselor can help the client identify ways they might increase their physical activity. Interventions promoting physical activity were found to reduce anxiety and depression in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic (Luo et al., 2022).

Limitations

This study had limitations that should be considered. First, with the study being retrospective and using secondary data from a clinical intervention, it was not possible to include measures that might have better clarified mechanisms of the changes that were observed in psychosocial symptoms. Thus, the possible explanations above of what might have driven these changes are tentative and future research should test them more directly. Second, individuals in the present study were likely to have been in greater distress than the general university population based on their exposure to COVID-19, which might limit the generalizability of the study’s findings. Third, individuals in the present study were from a single university in the Southeastern United States. Thus, our findings might not generalize to other regions where university-related COVID-19 policies might have differed. Fourth, the decision to create a binary independent variable to reflect time periods (August–September 2021 and January–February 2022) in the present study also entails a limitation. This decision was justifiable on the basis that it allowed for comparisons of individuals at similar points in academic semesters and during comparable periods of COVID-19 infection. However, this analysis decision means that inferences from the study’s results are limited to the two specific time periods that were analyzed. Fifth, individuals in the present study responded to items on the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 through a phone conversation with interviewers. Interviewer-administered surveys have been previously associated with greater tendencies toward socially desirable responses than self-administered surveys (Bowling, 2005). This might limit the present study’s generalizability in contexts where self-administrations of the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 are used.

Future Research

The results of this study provide important directions for future research. Future researchers who can conduct prospective studies or who have access to larger retrospective datasets should aim to determine specific factors that might lead to improvement in mental health outcomes over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Knowledge produced by such studies could contribute to clinical applications in the future regarding COVID-19 or other pandemics that might occur. Relatedly, future research with larger samples of demographically diverse participants should explore possible demographic differences in specific mental health trajectories in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Future research should continue to focus specifically on those who are interested in mental health information and interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. To follow up this study’s findings, future quantitative and qualitative studies should aim to identify which individuals are interested in receiving mental health services and determine the best ways to deliver services to them. As a globally experienced stressor, the COVID-19 pandemic might have changed some individuals’ views of mental health and/or their receptiveness to mental health outreach. More specifically, some might be more receptive to available mental health information even at lower thresholds of anxiety, depression, or other psychosocial symptoms. Such clients might be interested in preventive services or their interest in mental health information might be driven by other factors. Future studies should address these possibilities more directly than was possible in the present retrospective study.

Conclusion

Overall, the present study provided a positive picture regarding psychosocial symptomatology in later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from this study of students and employees at a university in the Southeastern Unites States following their return to campus found that many individuals requesting mental health information after exposure to COVID-19 showed minimal levels of depression and anxiety. Individuals in the study were more likely to be in these minimal ranges during January–February 2022 than August–September 2021. COVID-19 will continue to have effects in individuals’ lives through future infections and potentially through lasting effects of previous stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. As organized in-person activities resume and COVID-19 infections continue, counseling researchers and practitioners should continue efforts to best characterize and address individuals’ mental health needs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Ahuvia, I. L., Sung, J. Y., Dobias, M. L., Nelson, B. D., Richmond, L. L., London, B., & Schleider, J. L. (2022). College student interest in teletherapy and self-guided mental health supports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2062245

Beiter, R., Nash, R., McCrady, M., Rhoades, D., Linscomb, M., Clarahan, M., & Sammut, S. (2015). The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 173, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054

Bowling, A. (2005). Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. Journal of Public Health, 27(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdi031

Bzdok, D., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2020). The neurobiology of social distance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(9), 717–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.016

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, March 15). COVID-19 timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html

Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., Rettew, J., & Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 134–141.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466

Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 126–134.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 15(7), Article e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A., & Bu, F. (2021). Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X

Fioravanti, G., Benucci, S. B., Prostamo, A., Banchi, V., & Casale, S. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological health in a sample of Italian adults: A three-wave longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research, 315, Article 114705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114705

Food and Drug Administration. (2021, August 23). FDA approves first COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-covid-19-vaccine

Huckins, J. F., daSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E. I., Meyer, M. L., Wagner, D. D., Holtzheimer, P. E., & Campbell, A. T. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), Article e20185.

https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Liu, C. H., Stevens, C., Wong, S. H. M., Yasui, M., & Chen, J. A. (2019). The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among U.S. college students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depression and Anxiety, 36(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22830

Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46(3), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

Luo, Q., Zhang, P., Liu, Y., Ma, X., & Jennings, G. (2022). Intervention of physical activity for university students with anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215338

Marroquín, B., Vine, V., & Morgan, R. (2020). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Research, 293, Article 113419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419

Martin, A., Rief, W., Klaiberg, A., & Braehler, E. (2006). Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(1), 71–77.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003

McLeish, A. C., Walker, K. L., & Hart, J. L. (2022). Changes in internalizing symptoms and anxiety sensitivity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 44, 1021–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-022-09990-8

Meyer, J., McDowell, C., Lansing, J., Brower, C., Smith, L., Tully, M., & Herring, M. (2020). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in response to COVID-19 and their associations with mental health in 3052 US adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), Article 6469.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186469

Oh, H., Marinovich, C., Rajkumar, R., Besecker, M., Zhou, S., Jacob, L., Koyanagi, A., & Smith, L. (2021). COVID-19 dimensions are related to depression and anxiety among US college students: Findings from the Healthy Minds Survey 2020. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.121

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Dosil Santamaría, M., & Picaza Gorrotxategi, M. (2020). Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: An investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 1491.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01491

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R., & Feinstein, A. R. (1996). A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49(12), 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Prati, G., & Mancini, A. D. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological Medicine, 51(2), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721000015

Rettie, H., & Daniels, J. (2021). Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000710

Riehm, K. E., Holingue, C., Kalb, L. G., Bennett, D., Kapteyn, A., Jiang, Q., Veldhuis, C. B., Johnson, R. M., Fallin, M. D., Kreuter, F., Stuart, E. A., & Thrul, J. (2020). Associations between media exposure and mental distress among U.S. adults at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(5), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.008

Schubert, M., Ludwig, J., Freiberg, A., Hahne, T. M., Romero Starke, K., Girbig, M., Faller, G., Apfelbacher, C., von dem Knesebeck, O., & Seidler, A. (2021). Stigmatization from work-related COVID-19 exposure: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126183

Silva, D. T. C., Prado, W. L., Cucato, G. G., Correia, M. A., Ritti-Dias, R. M., Lofrano-Prado, M. C., Tebar, W. R., & Christofaro, D. G. D. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity level and screen time is associated with decreased mental health in Brazillian adults: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Psychiatry Research, 314, Article 114657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114657

Şimşir, Z., Koç, H., Seki, T., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Death Studies, 46(3), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1889097

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), Article e21279. https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Stamatis, C. A., Broos, H. C., Hudiburgh, S. E., Dale, S. K., & Timpano, K. R. (2022). A longitudinal investigation of COVID-19 pandemic experiences and mental health among university students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12351

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Tang, N. K. Y., McEnery, K. A. M., Chandler, L., Toro, C., Walasek, L., Friend, H., Gu, S., Singh, S. P., & Meyer, C. (2022). Pandemic and student mental health: Mental health symptoms amongst university students and young adults after the first cycle of lockdown in the UK. BJPsych Open, 8(4), Article e138.

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.523

Wise, T., Zbozinek, T. D., Michelini, G., Hagan, C. C., & Mobbs, D. (2020). Changes in risk perception and self-reported protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

Royal Society Open Science, 7(9), Article 200742. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200742

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Wesley B. Webber, PhD, NCC, is a postdoctoral scholar at East Carolina University. W. Leigh Atherton, PhD, LCMHCS, LCAS, CCS, CRC, is an associate professor and program director at East Carolina University. Kelli S. Russell, MPH, RHEd, is a teaching assistant professor at East Carolina University. Hilary J. Flint, NCC, LCMHCA, is a clinical counselor at C&C Betterworks. Stephen J. Leierer, PhD, is a research associate at the Florida State University Career Center. Correspondence may be addressed to Wesley B. Webber, Department of Addictions and Rehabilitation Studies, Mail Stop 677, East Carolina University, 1000 East 5th Street, Greenville, NC 27858-4353, webberw21@ecu.edu.

Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Byeolbee Um, Lindsay Woodbridge, Susannah M. Wood

This content analysis examined articles on international counseling students published in selected counseling journals between 2006 and 2021. Results of this study provide an overview of 18 articles, including publication trends, methodological designs, and content areas. We identified three major themes from multiple categories, including professional practices and development, diverse challenges, and personal and social resources. Implications for counseling researchers and counselor education programs to increase understanding and support for international counseling students are provided.

Keywords: international counseling students, counseling journals, content analysis, publication trends, counseling researchers

International counseling students (ICSs) can be defined as individuals from outside the United States who seek professional training by enrolling in counselor education programs in the United States. After graduation, they often keep contributing to the counseling field as professional counselors or counselor educators, either in the United States or their home countries (Behl et al., 2017). In 2021, non-resident international students accounted for 1.02% of master’s students and 3.81% of doctoral students in counseling programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2022). However, because these percentages do not include international students who have resident alien status in the United States (Karaman et al., 2018), the actual numbers of international students in counseling programs may be higher. Despite the underestimated number of ICSs in CACREP-accredited programs, Ng (2006) found that at least one international student was enrolled in 41% of CACREP-accredited programs, which suggested that many counselor education programs already had some degree of global cultural diversity. Considering that the number of ICSs in the United States has risen within a few decades (CACREP, 2022; Ng, 2006), additional research is needed on this population and how best to prepare them for professional practice.

Research on International Students in Counseling Programs

While in training, ICSs, like domestic students, experience pressure to perform across academic, practical, and personal contexts (Thompson et al., 2011). However, ICSs face the additional challenges of adapting to a new culture and practicing counseling in that culture (Ju et al., 2020; Kuo et al., 2021; Ng & Smith, 2009). These challenges stem from having varying levels of experience using English in an academic context, adapting to new sociocultural and interpersonal patterns, and navigating key clinical factors of counselor education such as supervision and therapeutic relationships (Jang et al., 2014; C. Li et al., 2018; Y. Mori et al., 2009). Researchers have found that ICSs perceive more barriers and concerns regarding their training, such as academic problems and role ambiguity in supervision (Akkurt et al., 2018; Ng & Smith, 2009).

Regarding the experiences of ICSs, researchers have paid scholarly attention to the concept of acculturation, which is the assimilation process an individual experiences in response to the psychological, social, and cultural forces they are exposed to in a new dominant culture (C. Li et al., 2018; Ng & Smith, 2012). According to counseling studies, ICSs’ levels of acculturation and acculturative stress were associated with several variables related to their professional development, including counseling self-efficacy, language anxiety, and diverse academic and life needs (Behl et al., 2017; Interiano-Shiverdecker et al., 2019; C. Li et al., 2018). For example, Interiano-Shiverdecker et al. (2019) found that two domains of acculturation—ethnic identity and individualistic values—were positively associated with counseling self-efficacy for international counseling master’s students. Researchers have also uncovered the potential issues ICSs can experience related to a lack of acculturation: Behl et al. (2017) found that students’ acculturative stress was positively associated with their academic, social, cultural, and language needs.

With goals of uncovering effective coping strategies and identifying characteristics of high-quality training environments, researchers have investigated the personal and academic experiences of ICSs (Lau & Ng, 2012; Nilsson & Wang, 2008; Park et al., 2017; Woo et al., 2015). Woo and colleagues (2015) identified several coping tools of ICSs. These tools included self-directed strategies such as engaging in reflection and keeping up with the latest literature, support from mentors, and networking among international students and graduates (Woo et al., 2015). Researchers have attended to strategies that support ICSs’ development of cultural competence and commitment to social justice (Delgado-Romero & Wu, 2010; Karaman et al., 2018; Ng & Smith, 2012). For example, Delgado-Romero and Wu (2010) piloted a social justice group intervention with six Asian ICS participants and found the intervention to be a useful way to empower students and enhance their critical consciousness about inequity.

Supervision has been another area of focus in ICS research. Through interviews and surveys of ICSs, researchers have identified supervision strategies that support ICSs’ developing cultural competence, professional development, and self-efficacy (Mori et al., 2009; Ng & Smith, 2012; Park et al., 2017). A shared theme across these studies is the importance of clear communication. Findings of two studies (Mori et al., 2009; Ng & Smith, 2012) support supervisors engaging ICS supervisees in communication about critical topics such as cultural differences and the purpose and expectations of supervision. Based on a consensual qualitative analysis of interviews with 10 ICS participants, Park et al. (2017) recommended that programs and supervisors make sure to share basic information about systems of counseling, health care, and social welfare in the United States.

Necessity of ICS Research

Across academic units, there has been a growing attention to international graduate students (Anandavalli et al., 2021; Vakkai et al., 2020). Given the increasing representation of international students in counseling programs, researchers have called for academic and practical strategies to support ICSs’ success in training (Lertora & Croffie, 2020; Woo et al., 2015). These calls are aligned with the values of professional counseling organizations. Specifically, the American Counseling Association (ACA; 2014) endorsed respect for diversity and multiculturalism as elements of counselor competence. This value is reflected in the ACA Code of Ethics, including Standard F.11.b, which urges counselor educators to value a diverse student body in counseling programs. Similarly, the CACREP standards have identified counseling programs as responsible for working to include “a diverse group of students and to create and support an inclusive learning community” (CACREP, 2015, p. 6). Because counselors must have a profound comprehension of and commitment to diversity, experiences with multiculturalism during professional training programs are essential (O’Hara et al., 2021; Ratts et al., 2016). In this vein, the presence of international students in counseling programs can be beneficial for both domestic and international students by enhancing trainees’ understanding of diversity and multicultural counseling competencies (Behl et al., 2017; Luo & Jamieson-Drake, 2013). Given that there is a substantially increasing need for addressing multiculturalism, diversity, and social justice in the counseling profession, counseling programs’ efforts to recruit various minority student groups, including ICSs, will contribute to not only counselor training but also client outcomes in the long term.

However, despite the importance of the topic, researchers have consistently indicated that research on ICSs has been quite limited (Behl et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2019). In counseling research, there is a history of researchers using content analysis to provide a comprehensive overview of topics that are underrepresented but have growing importance. For example, Singh and Shelton (2011) published a content analysis of qualitative research related to counseling lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer clients. Involving the summarization of findings from a body of literature into a few key categories or content areas (Stemler, 2001), content analysis is a useful methodology for expanding the field’s knowledge and understanding of the topic. Considering ICSs’ unique challenges and their potential contributions to enriching diversity in counseling programs and in the profession (Park et al., 2017), a comprehensive understanding of the current ICS literature is needed. This content analysis can identify how the research on ICSs has progressed and what remains unexplored or underexplored, which can provide meaningful implications for researchers interested in conducting ICS research in the future.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to identify major findings in literature recently published on ICSs in the United States and to draw useful implications for counseling researchers and counseling programs seeking to better understand and support international students in counseling programs. Our content analysis, which focused on ICS research published between 2006 and 2021 in selected counseling journals, was driven by the following research questions: 1) What are the publication trends in ICS research, such as prevalence, publication outlets, authorship, methodological design, and sample size and characteristics?; and 2) What is the content of the ICS research published in counseling journals? Based on the findings, this study aimed to suggest recommendations for counseling researchers to fill the scholarly gap in ICS research and for counselor education programs to provide more effective training experiences to their international trainees.

Method

Content analysis is a useful methodology to expand our knowledge and understanding of the field through an overview of the current literature (Stemler, 2001). This approach makes it possible to effectively summarize a large amount of data using a few categories or content areas. In counseling research, content analysis has been used to provide an overview of a profession that is underrepresented but with growing importance (e.g., LGBTQ; Singh & Shelton, 2011), which is aligned with the aim of this study. This study employed both quantitative and qualitative content analysis to provide an overview of ICS research. Quantitative content analysis refers to analyzing the data in mathematical ways and applying predetermined categories that do not derive from the data (Forman & Damschroder, 2007). After reviewing existing content analysis articles in the counseling field, Byeolbee Um and Susannah M. Wood determined the scope of our quantitative analysis as: (a) journal and authorship, (b) research design, (c) participant characteristics, and (d) data collection methods.

Research Team

The research team consisted of two doctoral candidates and one full professor, all of whom were affiliated with the same CACREP-accredited counselor education and supervision program at a Midwestern university. Um and Lindsay Woodbridge were doctoral candidates in counselor education and supervision when conducting this research project and are currently counselor educators. Um is an international scholar from an East Asian country. She has drawn on her experiences in quantitative and qualitative courses and research projects to engage in research of marginalized counseling students, including ICSs. Woodbridge is a domestic scholar who has taken classes and collaborated with international student peers and worked with international students in instructional and clinical capacities. She has taken quantitative and qualitative research courses and completed several research projects. The first and second authors met regularly to establish the scope of the investigation, collect data, and form a consensus on coding emerging categories and sorting them into themes. Wood, an experienced researcher and instructor, has worked as a counselor educator for more than 15 years. She has worked with international students in teaching, supervision, advising, and mentoring capacities. She audited the research process, reviewed emergent categories and themes, and provided constructive feedback at each phase of the study.

Data Collection

To identify a full list of ICS studies that satisfy the scope of this study, Um and Woodbridge independently performed electronic searches using research databases including EBSCO, PsycINFO, and ERIC. Because ICSs have attracted scholarly attention relatively recently and because Ng’s (2006) study that estimated the number of ICSs in CACREP-accredited programs was the first published research on ICSs in counselor education programs, we set 2006 as the initial year of our search. We used the following search criteria to identify candidate articles: (a) published between 2006 and 2021 in ACA division, branch, and state journals and major journals under the auspices of professional counseling organizations; (b) containing one or more of the following keywords: international students, international counseling students, international counseling trainees, international counseling programs, counselor education; and (c) involving original empirical findings from ICSs in the United States.

We conducted an extensive search of ICS research across various journals in the counselor education field and identified ICS articles from several ACA-related journals, including Counselor Education and Supervision (CES), Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development (JMCD), The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision (JCPS), The Journal for Specialists in Group Work (JSGW), and the Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research (JPC). Additionally, we found ICS articles from the International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling (IJAC) and the Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy (JCLA), which are associated with the International Association for Counselling and Chi Sigma Iota, respectively. Although they are not under the broader umbrella of ACA, these journals have contributed to enriching scholarship in the counseling field.

After the initial searches, Um and Woodbridge made a preliminary list of the articles identified based on the search results. Subsequently, they re-screened the articles independently. Among the 27 identified articles, we excluded five conceptual papers, three articles that examined counselors’ or counselor educators’ experiences after graduation, and one article about ICSs in Turkey. Consequently, the final data consisted of 18 articles published by seven selected counseling journals.

Data Analysis

The research team analyzed content areas of the ICS research as an extension of qualitative content analysis, which requires performing the systematical coding and identifying categories/themes (Cho & Lee, 2014). We followed a series of steps suggested by Downe-Wamboldt (1992), which included selecting the unit of analysis, developing and modifying categories, and coding data. Several methods were used to ensure the trustworthiness of this content analysis study (Kyngäs et al., 2020). For credibility, Um and Woodbridge conducted multiple rounds of review on determining an adequate unit of analysis and tracked all discussions and modifications in great detail. For dependability, we calculated interrater reliability coefficients and Wood provided feedback about the results. Um also secured confirmability by utilizing audit trails, which described the specific steps and reflections of the project. Finally, to support transferability, we carefully examined other content analysis articles, reflected core aspects in the current study, and depicted the research process transparently.

Coding Protocol

After completing the quantitative content analysis, we conducted the qualitative content analysis as Downe-Wamboldt (1992) suggested. In so doing, we applied the inductive category development process suggested by Mayring (2000), which features a systematic categorization process of identifying tentative categories, coding units, and extracting themes from established categories. Specifically, after discussing the research question and levels of abstraction for categories, Um and Woodbridge determined the preliminary categories based on the text of the 18 ICS articles. We practiced coding the data using two articles and then performed independent coding of the remaining articles. Using a constructivist approach, we agreed to add additional categories as needed. Subsequently, the categories were revised until we reached a consensus. In the final step, established categories were sorted into three themes to identify the latent meaning of qualitative materials (Cho & Lee, 2014; Forman & Damschroder, 2007). Regarding validity, the congruence between existing conceptual themes and results of data coding secures external validity, which is regarded as the purpose of content analysis (Downe-Wamboldt, 1992).

Interrater Reliability

We used various indices of interrater reliability to assess the overall congruence between the researchers who performed the qualitative analysis and ensure trustworthiness. In this study, we used the kappa statistic (κ) suggested by Cohen (1960), which shows the extent of consensus among raters for selecting an article or coding texts (Stemler, 2001). Cohen’s kappa has been used extensively across various academic fields to measure the degree of agreement between raters. More specifically, the kappa statistic was calculated in two phases: 1) after screening articles and 2) after coding the texts according to the categories. The kappa results between Um and Woodbridge were .68 for screening articles and .71 for coding the text, both of which are considered substantial (.61–.80; Stemler, 2004).

Results

Results of Quantitative Content Analysis

Based on our electronic search, we identified a total of 18 ICS articles published between 2006 and 2021 in seven selected counseling journals, including three ACA division journals, one ACA state-branch journal, one ACES regional journal, and two journals from professional counseling associations (see Table 1). Specifically, two articles were published in CES, three in JMCD, one in JCPS, one in JSGW, three in JPC, seven in IJAC, and one in JCLA. Across the 18 ICS articles, a total of 35 researchers were identified as authors or co-authors with six authoring more than one article. According to researchers’ positionality statements in qualitative articles, eight researchers reported that they were previous or current ICSs in the United States. The institutional affiliations of researchers include 22 U.S. universities and two international universities, with three institutional affiliations appearing more than once across the studies.

Table 1

Summary of International Counseling Student Research in Selected Counseling Journals Between 2006 and 2021

| Journal and Author |

Research Design |

Participants |

Data Collection |

Topic |

| Counselor Education and Supervision (CES) |

Behl et al.

(2017) |

Quantitative

(Pearson product-moment correlations) |

38 counseling master’s and doctoral students |

Online survey |

Stress related to acculturation and students’ language, academic, social, and cultural needs |

D. Li & Liu

(2020) |

Qualitative (Phenomenology) |

11 doctoral students |

Semi-structured interview |

ICSs’ experiences with teaching preparation |

| Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development (JMCD) |

Kuo et al.

(2021) |

Qualitative (Consensual

qualitative research) |

13 doctoral students |

Semi-structured interview |

ICSs’ professional identity development influenced by their multicultural identity and experience |

Nilsson &

Dodds (2006) |

Quantitative (Exploratory factor analysis, ANOVA, and hierarchical multiple regression analysis) |

115 master’s and doctoral students in counseling and psychology |

Online survey |

Development of a scale to measure issues in supervision |

Woo et al.

(2015) |

Qualitative (Consensual qualitative research) |

8 counselor education doctoral students |

Semi-structured interview |

Coping strategies used during training in supervision |

| The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision (JCPS) |

Park et al.

(2017) |

Qualitative (Consensual qualitative research) |

10 counseling master’s and doctoral students |

Semi-structured interview |

Practicum and internship experiences of ICSs |

| The Journal for Specialists in Group Work (JSGW) |

Delgado-Romero

& Wu (2010) |

Qualitative

(Not identified) |

6 Asian counseling graduate students |

Counseling

practice |

Social justice–focused group intervention |

| Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research (JPC) |

Interiano-

Shiverdecker

et al. (2019) |

Quantitative (Hierarchical multiple regression analysis) |

94 counseling master’s and doctoral students |

Online survey |

Relationship between acculturation and self-efficacy |

| Ng (2006) |

Quantitative (Descriptive analysis) |

96 CACREP-accredited

counseling programs |

Responses via email/telephone |

Enrollment in CACREP-accredited programs |

Sangganjanavanich

& Black (2009) |

Qualitative (Phenomenology) |

4 master’s students

and 1 doctoral student

in counseling |

Semi-structured interview |

Perceptions of supervision |

|

|

|

|

|

| International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling (IJAC) |

|

|

Akkurt et al.

(2018) |

Quantitative (Moderation analysis) |

71 counseling master’s and doctoral students |

Online survey |

Relationships between acculturation, counselor self-efficacy, supervisory working alliance, and role ambiguity moderated by frequency of multicultural discussion |

Interiano & Lim

(2018) |

Qualitative (Interpretive phenomenology) |

8 foreign-born doctoral students |

Semi-structured interview |

Influence of acculturation on ICSs’ professional development |

Lertora & Croffie

(2020) |

Qualitative (Phenomenology) |

6 counseling master’s students |