Apr 28, 2020 | TPC Outstanding Scholar

Jennifer L. Rogers, Jamie E. Crockett, and Esther Suess

Jennifer L. Rogers, Jamie E. Crockett, and Esther Suess received the 2019 Outstanding Scholar Award for Concept/Theory for their article, “Miscarriage: An Ecological Examination.”

Jennifer L. Rogers, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor in the Wake Forest University Department of Counseling. She received her PhD in counseling and counselor education from Syracuse University. Her clinical and research interests are centered around relational approaches to counseling, supervision, and counselor preparation across ecologically diverse practice contexts. Her current research focuses upon how attachment and cognitive patterns among beginning counselors influence their experiences during clinical supervision.

Jamie E. Crockett, PhD, NCC, LCMHCA, is an assistant professor in the Wake Forest University Department of Counseling and a clinical mental health counselor at Triad Counseling and Clinical Services. Her clinical and research interests include human development, attachment, gender and sexuality, reproductive health, grief and loss, contemplative and breath-based approaches, emotion, wellness, religion and spirituality, ethics, feminism, and diversity and culture.

Esther Suess, MA, NCC, LPC-A, LCMHCA, is a mental health counselor at the Mood Treatment Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, with a specialty in the treatment of eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder. She graduated with an undergraduate degree in psychology from University College Dublin in 2016 and received her master’s degree in clinical mental health counseling from Wake Forest University in 2018. Her research interests include cultural diversity and biopsychosocial factors in counseling and eating disorders.

Read more about the TPC scholarship awards here.

Mar 9, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 1

Michael T. Kalkbrenner

College counselors work collaboratively with professionals in a variety of disciplines in higher education to coordinate gatekeeper training to prepare university community members to recognize and refer students in mental distress to support services. This article describes the cross-validation of scores on the Mental Distress Response Scale (MDRS), a questionnaire for appraising university community members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress, with a sample of faculty members. A confirmatory factor analysis revealed the dimensions of the MDRS were estimated adequately. Results also revealed demographic differences in faculty members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress. The MDRS has implications for augmenting the outreach efforts of college counselors. For example, the MDRS has potential utility for enhancing campus-wide mental health screening efforts. The MDRS also has implications for supporting psychoeducation efforts, including gatekeeper training workshops, for professional counselors practicing in college settings.

Keywords: Mental Distress Response Scale, mental health, college counselors, gatekeeper, outreach

College counselors play crucial roles in supporting students’ personal, social, and academic growth, as well as students’ success (Golightly et al., 2017). Outreach and prevention programming, including campus violence prevention and supporting college student mental health, are two key elements in the practice of college counselors (Brunner et al., 2014; Golightly et al., 2017). Addressing these two key areas has become increasingly challenging in recent years because of the prevalence of campus violence incidents, including mass shootings in the most severe cases, and the frequency of mental health distress among college students, which has increased substantially since the new millennium (Auerbach et al., 2016; Barrett, 2014; Vieselmeyer et al., 2017). In fact, supporting college student mental health has become one of the greatest challenges that institutions of higher education are facing (Reynolds, 2013).

Most college students suffering from mental health issues do not seek treatment (Downs & Eisenberg, 2012). In response, college counselors, student affairs professionals, and higher education administrators are working collaboratively to develop and implement mental health awareness initiatives and gatekeeper training workshops, which include training university community members (e.g., students, faculty, and staff) as referral agents to recognize and refer students who are showing warning signs for suicide or other mental health issues to support services (Albright & Schwartz, 2017; Hodges et al., 2017). Faculty members are particularly valuable referral agents, as they tend to interact with large groups of students on frequent occasions, and they generally report positive attitudes about supporting college student mental health (Albright & Schwartz, 2017; Kalkbrenner, 2016).

Despite the utility of faculty members as gatekeepers for recognizing and referring students to the university counseling center and to other resources, the results of a recent national survey indicated that a significant proportion of faculty members (63%) do not refer a student in mental distress to support services (Albright & Schwartz, 2017). The literature is lacking research on how faculty members are likely to respond to encountering a student in mental distress, including but not limited to making a faculty-to-student referral to mental health support services. The primary aim of this investigation was to confirm the psychometric properties of the Mental Distress Response Scale (MDRS), a screening tool for measuring university community members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress. Past investigators validated the MDRS for use with 4-year university students (Kalkbrenner & Flinn, 2020) and community college students (Kalkbrenner, 2019). If found valid for use with faculty members, college counselors could find the MDRS useful for screening and promoting faculty-to-student mental health support. A review of the extant literature is provided in the following section.

Mental Health and the State of Higher Education

Active shooter incidents on college campuses are some of the most tragic events in American history (Kalkbrenner, 2016). The 2015 massacre that occurred on a college campus in Oregon received attention at the highest level of government; former President Barack Obama urged the nation to decide when voting “whether this cause of continuing death for innocent people should be a relevant factor.” (Vanderhart et al., 2015, section A, p. 1). Seung-Hui Cho was a perpetrator of another one of these tragedies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 2007. According to Cho’s mother, he had a history of social isolation and unresolved mental health issues (Klienfield, 2007). Without treatment, the effects of mental health disorders can be debilitating and widespread for students, including impairments in academic functioning, attrition, self-harm, social isolation, and suicide or homicide in the most serious cases (Kalkbrenner, 2016; Shuchman, 2007). The early detection and treatment of students who are at risk for mental health disorders is a harm-prevention strategy for reducing campus violence incidents and promoting college student mental health (Futo, 2011; Kalkbrenner, 2016). Consequently, the practice of college counselors involves deploying outreach and systems-level mental health support interventions (Albright & Schwartz, 2017; Brunner et al., 2014; Golightly et al., 2017).

The Role of College Counselors in Providing Systems-Level Interventions

Providing individual counseling is a key role of college counselors (Golightly et al., 2017). In recent years, however, the practice of college counselors has been extended to providing systems-level and preventative mental health interventions to meet the growing mental health needs of college student populations (Brunner et al., 2014; Golightly et al., 2017). In particular, college counselors and their constituents engage in both campus-wide and targeted prevention and outreach programs (Golightly et al., 2017; Lynch & Glass, 2019), including gatekeeper training workshops to prepare university community members as referral agents or train them to recognize and refer students at risk for suicide and other mental health issues to the university counseling center (Albright & Schwartz, 2017; Brunner et al., 2014). These collaborative, educative, and preventative efforts are particularly crucial given the increase in both the severity and complexity of mental health disorders among college students (Gallagher, 2015; Reetz et al., 2016). The findings of past investigators suggest that faculty members are particularly viable referral agents for recognizing and referring students in mental distress to the counseling center (Kalkbrenner, 2016; Margrove et al., 2014).

Faculty Members as Referral Agents

Faculty members have a propensity to serve as referral agents (i.e., recognize and refer students in mental distress to resources) because of their frequent contact with students and their generally positive attitudes and willingness to support their students’ mental and physical wellness (Albright & Schwartz, 2017). Albright and Schwartz (2017) found that approximately 95% of faculty members and staff considered connecting students in mental distress to resources as one of their roles and responsibilities. Similarly, Margrove et al. (2014) found that 64% of untrained university staff members expressed a desire to receive training to recognize warning signs of mental health disorders in students.

Past investigators extended the line of research on the utility of faculty members as gatekeepers by identifying demographic differences by gender and help-seeking history (previous attendance in counseling) in faculty members’ tendency to support college student mental health (Kalkbrenner & Carlisle, 2019; Kalkbrenner & Sink, 2018). In particular, Kalkbrenner and Sink (2018) identified gender as a significant predictor of faculty-to-student counseling referrals, with faculty who identified as female more likely to make faculty-to-student referrals to the counseling center compared to their male counterparts. Similarly, Kalkbrenner and Carlisle (2019) found that faculty members’ awareness of warning signs for mental distress in students was a significant positive predictor of faculty-to-student referrals to the counseling center. In addition, faculty members with a help-seeking history (previous attendance in counseling) were significantly more aware of warning signs for mental distress in their students compared to faculty without a help-seeking history (Kalkbrenner & Carlisle, 2019).

Faculty Members’ Responses to Encountering a Student in Mental Distress

Despite the growing body of literature on institutional agents’ participation in gatekeeper training (i.e., recognize and refer), research on the measurement and appraisal of how faculty members are likely to respond when encountering a student in mental distress is in its infancy. The results of a recent national survey of college students (N = 51,294) and faculty members (N = 14,548) were troubling, as 63% of faculty members did not refer a student in psychological distress to mental health support services (Albright & Schwartz, 2017). Making a referral to the university counseling center is one possible response of students and faculty members to encountering a peer or student in mental distress (Kalkbrenner & Sink, 2018). However, the findings of Albright and Schwartz (2017) highlight a gap in the literature regarding how university community members are likely to respond when encountering a student in mental distress, including but not limited to making a faculty-to-student referral to the college counseling center.

To begin filling this gap in the literature, Kalkbrenner and Flinn (2020) developed, validated, and cross-validated scores on the MDRS to assess 4-year university students’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress, including but not limited to making a referral to mental health support services. In a series of two major phases of psychometric analyses, Kalkbrenner and Flinn identified and confirmed two dimensions or subscales of the MDRS, including Diminish/Avoid and Approach/Encourage, with two large samples of undergraduate students. The Diminish/Avoid subscale measures adverse or inactive responses of university community members to encountering a student in mental distress (e.g., stay away from the person or warn the person that mental issues are perceived as a weakness). The Approach/Encourage subscale appraises facilitative or helpful responses of university community members when encountering a student in mental distress that are likely to help connect the person to resources (e.g., talking to a college counselor or suggesting that the person go to the campus counseling or health center). However, the psychometric properties of the MDRS have not been tested with faculty members. If found valid for such purposes, the MDRS could be a useful tool that college counselors and their constituents can use to screen and promote faculty-to-student referrals to mental health support services. In particular, the following research questions were posed: (1) Does the two-dimensional hypothesized MDRS model fit with a sample of faculty members? and (2) To what extent are there demographic differences in faculty members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress?

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected electronically from faculty members using Qualtrics, a secure e-survey platform. A nonprobability sampling procedure was used by sending a recruitment email message with an electronic link to the survey to 1,000 faculty members who were teaching at least one course at a research-intensive, mid-Atlantic public university at the time of data collection. A total of 221 faculty members clicked on the electronic link to the survey and 11 responses were omitted from the data set because of 100% missing data, resulting in a useable sample size of 210, yielding a response rate of 21%. This response rate is consistent with the response rates of other investigators (e.g., Brockelman & Scheyett, 2015; Kalkbrenner & Carlisle, 2019) who conducted survey research with faculty members. For gender, 58% (n = 122) identified as female, 41% (n = 86) as male, and 0.5% (n = 1) as non-binary or third gender, and 0.5% (n = 1) did not specify their gender. For ethnicity, 79.0% (n = 166) identified as Caucasian, 6.2% (n = 11) as African American, 3.8% (n = 8) as Hispanic or Latinx, 2.9% (n = 6) as Asian, 2.9% (n = 6) as multiethnic, 0.5% (n = 1) as Hindu, and 0.5% (n = 1) as Irish, and 5.2% (n = 11) did not specify their ethnic identity. Participants ranged in age from 31 to 78 (M = 50; SD = 11). Participants represented all of the academic colleges in the university, including 28.6% (n = 60) Arts and Letters, 22.9% (n = 48) Education, 18.1% (n = 38) Sciences, 12.9% (n = 27) Health Sciences, 9% (n = 19) Engineering and Technology, and 7.6% (n = 16) Business, while 1% (n = 2) of participants did not specify their college.

Instrumentation

Demographic questionnaire

Following informed consent, participants were asked to indicate that they met the inclusion criteria for participation, including (1) employment as a faculty member, and (2) teaching at least one course at the time of data collection. Participants then responded to a succession of demographic items about their gender, ethnicity, age, academic college, and highest level of education completed. Lastly, respondents indicated their rank and help-seeking history (previous attendance in counseling or no previous attendance in counseling) and if they had referred at least one student to mental health support services.

Mental Distress Response Scale (MDRS)

The MDRS is a screening tool comprised of two subscales (Approach/Encourage and Diminish/Avoid) for measuring university community members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress (Kalkbrenner & Flinn, 2020). The items that mark the Approach/Encourage subscale appraise responses to mental distress that are consistent with providing support and encouragement to a student in mental distress (e.g., “suggest that they go to the health center on campus”). The Diminish/Avoid subscale measures adverse or inactive responses to encountering a student in mental distress (e.g., “try to ignore your concern”). Kalkbrenner and Flinn (2020) found adequate reliability evidence for an attitudinal measure (α > 0.70) and initial validity evidence for the MDRS in two major phases of analyses (exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis [CFA]) with two samples of college students. Kalkbrenner (2019) extended the line of research on the utility of the MDRS for use with community college students and found adequate reliability (α > 0.80) and validity evidence (single and multiple-group confirmatory analysis).

Data Analysis

A CFA based on structural equation modeling was computed using IBM SPSS Amos version 25 to cross-validate scores on the MDRS with a sample of faculty members (research question #1). Using a maximum likelihood estimation method, the following goodness-of-fit indices and thresholds for defining model fit were investigated based on the recommendations of Byrne (2016) and Hooper et al. (2008): Chi square absolute fit index (CMIN, non-significant p-value with an x2/df ratio < 3), comparative fit index (CFI > 0.95), incremental fit index (IFI > 0.95), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI > 0.95), goodness-of-fit index (GFI > 0.95), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.07), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < 0.08). Based on the findings of past investigators (e.g., Kalkbrenner & Sink, 2018) regarding demographic differences in faculty members’ propensity to support college student mental health, a 2 X 2 (gender X help-seeking history) MANOVA was computed to investigate demographic differences in faculty members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress (research question #2). The independent variables included gender (male or female) and help-seeking history (previous attendance in counseling or no previous attendance in counseling). Discriminant analysis was used as the post hoc procedure for significant findings in the MANOVA (Warne, 2014). The researcher examined both main effects and interaction effects and applied Bonferroni adjustments to control for the familywise error rate.

Results

CFA

The researcher ensured that the data set met the necessary assumptions for CFA (Byrne, 2016; Field, 2018). A missing values analysis revealed that less than 5% of data was missing for all MDRS items. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test revealed that the data was missing at random: χ2 (387) = 407.98, p = 0.22. Expectation maximization was used to impute missing values. Outliers were winsorized (Field, 2018) and skewness and kurtosis values for the MDRS items (see Table 1) were largely consistent with a normal distribution (+ 1; Mvududu & Sink, 2013). Inter-item correlations between the 10 items were favorable for CFA, and Mahalanobis d2 indices revealed no extreme multivariate outliers. The researcher ensured that the sample size was sufficient for CFA by following the guidelines provided by Mvududu and Sink (2013), including at least 10 participants per estimated parameter with a sample > 200.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for MDRS Items

| Item Content |

M |

SD |

Skew |

Kurtosis |

| 1. I would stay away from this person |

49.83 |

9.46 |

1.11 |

0.22 |

| 2. Suggest that they go to the health center on campus |

50.15 |

9.48 |

-0.60 |

-0.08 |

| 3. Try to ignore your concern |

49.74 |

9.08 |

1.07 |

1.08 |

| 4. Take them to a party |

49.21 |

3.11 |

0.70 |

0.81 |

| 5. Tell them to “tough it out” because they will feel better over time |

49.73 |

8.94 |

1.32 |

1.26 |

| 6. Suggest that they see a medical doctor on campus |

50.00 |

9.98 |

-0.24 |

-0.06 |

| 7. Avoid this person |

49.70 |

9.02 |

1.80 |

1.33 |

| 8. Suggest that they see a medical doctor in the community |

50.00 |

9.98 |

-0.49 |

-0.10 |

| 9. Warn the person that others are likely to see their mental health issues as a weakness |

49.31 |

7.14 |

1.90 |

1.59 |

| 10. Talk to a counselor about your concern |

50.00 |

9.97 |

-0.83 |

0.15 |

SEKurtosis = 0.15, SESkewness = 0.17.

Note. Values were winsorized and reported as standardized t-scores (M = 50; SD = 10).

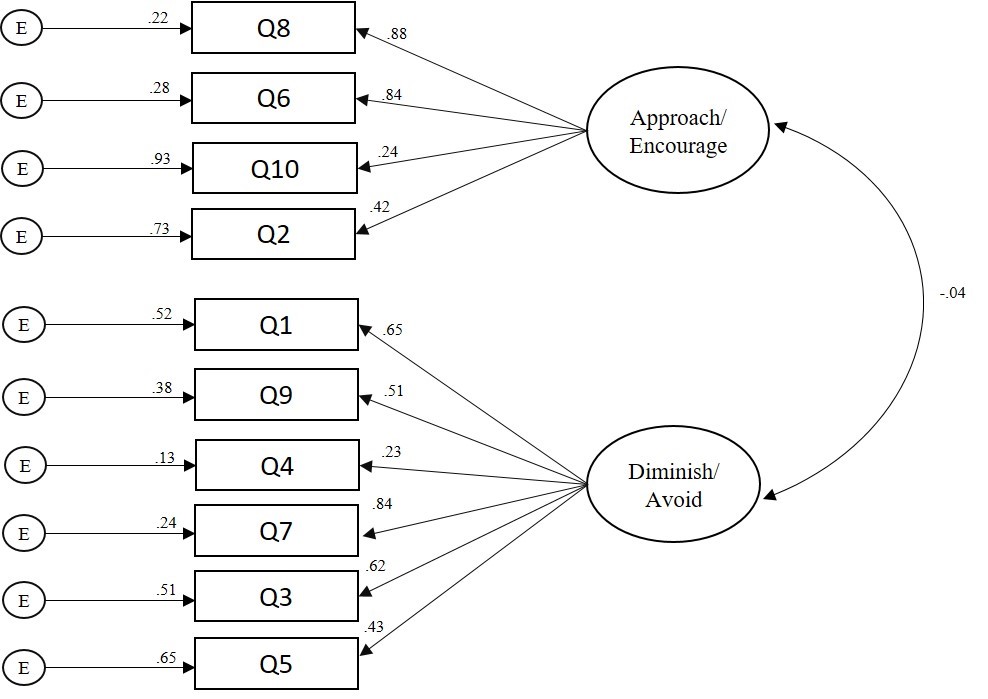

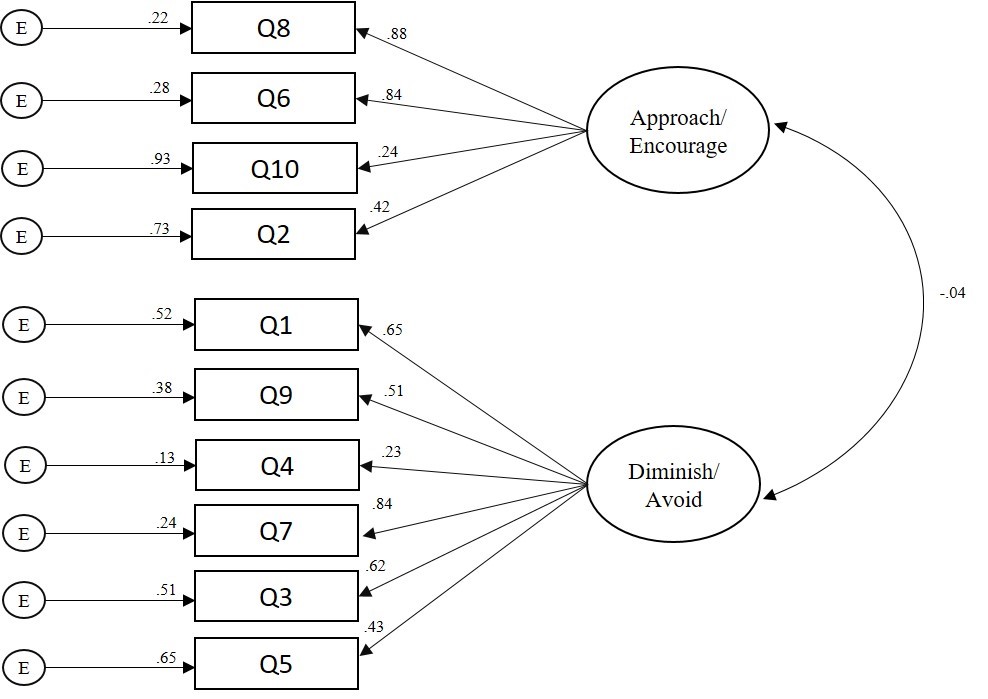

The 10 MDRS items (see Table 1) were entered in the CFA. A strong model fit emerged based on the GFI recommended by Byrne (2016) and Hooper et al. (2008). The CMIN absolute fit index demonstrated no significant differences between the hypothesized model and the data: χ2 (34) = 42.41, p = 0.15, CMIN/df = 1.25. In addition, the CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.96, IFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.03, 90% confidence interval [<.00, .06], and SRMR = 0.05 also demonstrated a strong model fit. Internal consistency reliability analyses (Cronbach’s coefficient alpha) revealed satisfactory reliability coefficients for an attitudinal measure, Diminish/Avoid (α = 0.73) and Approach/Encourage (α = 0.70). In addition, the path model coefficient (-0.04) between factors supported the structural validity of the scales (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Path Diagram for the Mental Distress Response Scale

Note. CFA = confirmatory factor analysis, MDRS = Mental Distress Response Scale.

Multivariate Analysis

A 2 X 2 (gender X help-seeking history) MANOVA was computed to investigate demographic differences in faculty members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress (research question #2). G*Power was used to conduct an a priori power analysis (Faul et al., 2007) and revealed that a minimum sample size of 151 would provide a 95% power estimate, α = .05, with a moderate effect size, F2(v) = 0.063. A significant main effect emerged for gender: F(3, 196) = 8.27, p < 0.001, Wilks’ λ = 0.92, = 0.08. The MANOVA was followed up with a post hoc discriminant analysis based on the recommendations of Warne (2014). The discriminant function significantly discriminated between groups: Wilks’ λ = 0.91, X2 = 18.85, df = 2, p < 0.001. The correlations between the latent factors and discriminant function showed that Diminish/Avoid loaded more strongly on the function (r = 0.98) than Approach/Encourage (r = 0.29), suggesting that Diminish/Avoid contributed the most to group separation in gender. The mean discriminant score on the function was -0.27 for participants who identified as female and 0.37 for participants who identified as male.

Discussion

The results of tests of internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s coefficient alpha), CFA, and correlations between factors supported the psychometric properties of the MDRS with a sample of faculty members. The results of the CFA were promising as GFI demonstrated a strong model fit between the two-dimensional hypothesized MDRS model and a sample of faculty members (research question #1). In particular, based on one of the most conservative and rigorous absolute fit indices, the CMIN (Byrne, 2016; Credé & Harms, 2015), the researchers retained the null hypothesis—there were no significant differences between the hypothesized factor structure of the MDRS and a sample of faculty members. The strong model fit suggests that Approach/Encourage and Diminish/Avoid are two latent variables that comprise faculty members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress. The findings of the CFA add to the extant literature about the utility of the MDRS for use with 4-year university students (Kalkbrenner & Flinn, 2020), community college students (Kalkbrenner, 2019), and now with faculty members.

An investigation of the path model coefficient between subscales (see Figure 1) revealed a small and negative association between factors, which supports the structural validity of the MDRS. In particular, the low and negative relationship between the Approach/Encourage and Diminish/Avoid subscales indicates that the dimensions of the MDRS are measuring discrete dimensions of a related construct. As expected, faculty members who scored higher on the Approach/Encourage subscale tended to score lower on the Diminish/Avoid subscale. However, the low strength of the association between factors suggests that faculty members’ responses to encountering a student in mental distress might not always be linear (e.g., a strong positive approach/encourage response might not always be associated with a strong negative diminish/avoid response). Haines et al. (2017) demonstrated that factors in the environment and temperament of a person showing signs of mental distress were significant predictors of mental health support staff’s perceptions of work safety. It is possible that under one set of circumstances faculty members might have an approach/encourage response to mental distress. However, under a difference set of circumstances, a faculty member might have a diminish/avoid response. For example, the extent to which a faculty member feels threatened or unsafe might mediate their propensity of having diminish/avoid or approach/encourage responses. Future research is needed to evaluate this possibility.

Consistent with the findings of previous researchers (Kalkbrenner & Carlisle, 2019; Kalkbrenner & Sink, 2018), the present investigators found that faculty members who identified as male were more likely to report a diminish/avoid response to encountering a student in mental distress compared to female faculty members. Similarly, Kalkbrenner and Sink (2018) found that male faculty members were less likely to make faculty-to-student referrals to the counseling center, and Kalkbrenner and Carlisle (2019) found that male faculty members were less likely to recognize warning signs of mental distress in college students. Similarly, the multivariate results of the present investigation revealed that male faculty members were more likely to report a diminish/avoid response to encountering a student in mental distress when compared to female faculty members. The synthesized findings of Kalkbrenner and Carlisle (2019), Kalkbrenner and Sink (2018), and the present investigation suggest that faculty members who identify as male might be less likely to recognize and refer a student in mental distress to mental health support services. The MDRS has valuable implications for enhancing the practice of professional counselors in college settings.

Implications for Counseling Practice

Outreach, consultation, and psychoeducation are essential components in the practice of college counselors (Brunner et al., 2014; Golightly et al., 2017). The findings of the present investigation have a number of practical implications for enhancing college counselors’ outreach and psychoeducation work—for example, gatekeeper workshops geared toward promoting faculty-to-student referrals to mental health support resources. The complex and multidimensional nature of college student mental health issues calls for interdisciplinary collaboration between college counselors and professionals in a variety of disciplinary orientations in higher education (Eells & Rockland-Miller, 2011; Hodges et al., 2017). College counselors can take leadership roles in coordinating these collaborative efforts to support college student mental health. In particular, college counselors can work with student affairs officials, higher education administrators, and their constituents, and attend new faculty orientations as well as department meetings to administer the MDRS, establish relationships with faculty, and discuss the benefits of gatekeeper training as well as supporting college student mental health. The results of the MDRS can be used to gain insight into the types of responses that faculty members are likely to have when encountering a student in mental distress. This information can be used to structure the content of gatekeeper training workshops aimed at promoting faculty-to-student referrals to mental health support services. Specifically, college counselors might consider the utility of integrating brief interventions and skills training components into gatekeeper training workshops. Motivational interviewing, for example, is an evidence-based, brief approach to counseling that includes both person-centered and directive underpinnings with utility for increasing clients’ intrinsic motivation to make positive changes in their lives (Iarussi, 2013; Resnicow & McMaster, 2012). Professional counselors who practice in higher education are already using motivational interviewing to promote college student development and mental health (Iarussi, 2013). Although future research is needed, integrating motivational interviewing principles (e.g., expressing empathy, rolling with resistance, developing discrepancies, and supporting self-efficacy; Iarussi, 2013) into gatekeeper training workshops might increase faculty members’ commitment to supporting college student mental health.

The MDRS has the potential to enhance college counselors’ outreach and mental health screening efforts (Golightly et al., 2017). College counselors can incorporate the MDRS into batteries of pretest/posttest measures (e.g., the MDRS with a referral self-efficacy measure) for evaluating the effectiveness of mental health awareness initiatives and gatekeeper training programs for faculty and other members of the campus community. If administered widely, the MDRS might have utility for assessing faculty members’ responses to students in mental distress across time and among various campus ecological systems, providing data to drive the prioritization and allocation of outreach efforts aimed at facilitating and maintaining referral networks for connecting students in mental distress to support services.

The results of the present study have policy implications related to campus violence prevention programming. The sharp increase in campus violence incidents has resulted in several universities implementing threat assessment teams as a harm-prevention measure (Eells & Rockland-Miller, 2011). Threat assessment teams involve an interdisciplinary collaboration of university faculty and staff for the purposes of recognizing and responding to students who are at risk of posing a threat to themselves or to others. College counselors can take leadership roles in establishing and supporting threat assessment teams at their universities. College counselors can administer the MDRS to faculty and staff and use the results as one way to identify potential threat assessment team members. University community members who score higher on the Approach/Encourage scale might be inclined to serve on threat assessment teams because of their propensity to support college student mental health. The brevity (10 questions) and versatility of administration (paper copy or electronically via laptop, smartphone, or tablet) of the MDRS adds to the practicality of the measure. Specifically, it might be practical for college counselors and their constituents to administer the MDRS during new faculty orientations, annual opening programs, or department meetings, or via email to faculty and staff. Results can potentially be used to recruit threat assessment team members.

Our findings indicate that when compared to their female counterparts, male faculty members might be more likely to have a diminish/avoid response when encountering a student in mental distress. College counselors might consider working collaboratively with student affairs professionals to implement gatekeeper training and mental health awareness workshops in academic departments that are comprised of high proportions of male faculty members. It is possible that male faculty members are unaware of how to identify warning signs of mental distress in their students (Kalkbrenner & Carlisle, 2019). College counselors might consider the utility of distributing psychoeducation resources for recognizing students in mental distress to faculty and staff. As just one example, the REDFLAGS model is an acronym of eight red flags or warning signs for identifying students who might be struggling with mental health issues (Kalkbrenner, 2016). Kalkbrenner and Carlisle (2019) demonstrated that the REDFLAGS model is a promising psychoeducational tool, as faculty members’ awareness of the red flags was a significant positive predictor of faculty-to-student referrals to the counseling center. The REDFLAGS model appears to be a practical resource for college counselors that can be distributed to faculty electronically or by paper copy, or posted as a flyer (Kalkbrenner, 2016; Kalkbrenner & Carlisle, 2019).

Limitations and Future Research

The findings of the present study should be considered within the context of the limitations. A number of methodological limitations (e.g., self-report bias and social desirability) can influence the validity of psychometric designs. In addition, the dichotomous nature of the faculty-to-student counseling referral variable (referred or not referred) did not provide data on the frequency of referrals. Future researchers should use a continuous variable (e.g., the number of student referrals to the counseling center in the past 2 years) to appraise faculty-to-student referrals. Future researchers can further test the psychometric properties of the MDRS through cross-validating scores on the measure with additional, unique populations of faculty members from a variety of different geographic and social locations. Invariance testing can be computed to examine the degree to which the MDRS and its dimensions maintain psychometric equivalence across different populations of faculty members. In addition, the criterion validity of the MDRS can be examined by testing the extent to which respondents’ MDRS scores are predictors of their frequency of student referrals to the counseling center and to other resources. Furthermore, future qualitative research is needed to investigate faculty members’ unique experiences around supporting college student mental health.

The low and negative association between the Approach/Encourage and Diminish/Avoid subscales suggests that faculty members might have an approach/encourage response to encountering a student in mental distress under one set of circumstances; however, they might have a diminish/avoid response under a difference set of circumstances. Future investigators might test the extent to which attitudinal variables mediate respondents’ MDRS scores—for example, the extent to which faculty members’ sense of safety predicts their MDRS scores. In addition, given the widespread public perception of individuals living with mental illness as violent and dangerous (Varshney et al., 2016), future researchers might identify demographic and background differences (particularly mental health stigma) among participants’ MDRS scores.

Summary and Conclusion

Mental health outreach and screening are essential components in the practice of college counselors, including training referral agents to recognize and refer students who might be struggling with mental health distress to support services (Golightly et al., 2017). Taken together, the results of the present study indicate that the MDRS and its dimensions were estimated sufficiently with a sample of faculty members. Our findings confirmed the two-dimensional hypothesized model for the types of responses that faculty might have when encountering a student showing signs of mental distress. In particular, the results of a CFA provided support for the MDRS and its dimensions, confirming a two-dimensional construct for the types of responses (approach/encourage and diminish/avoid) that faculty members might have when encountering a student in mental distress. Considering the utility of faculty members as gatekeepers and referral agents (Hodges et al., 2017; Kalkbrenner, 2016), researchers, practitioners, and policymakers may find the MDRS a useful screening tool for identifying the ways in which faculty members are likely to respond when encountering a student in mental distress. Results can be used to inform the content of mental health awareness initiatives and gatekeeper training programs aimed at promoting approach/encourage responses to connect students who need mental health support to the appropriate resources.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Albright, G. & Schwartz, V. (2017). Are campuses ready to support students in distress?: A survey of 65,177 faculty, staff, and students in 100+ colleges and universities. https://www.jedfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Kognito-JED-Are-Campuses-Ready-to-Support-Students-in-Distress.pdf

Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., Kessler, R. C., Liu, H., Mortier, P., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Andrade, L. H., Benjet, C., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., Demyttenaere, K., . . . Bruffaerts, R. (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46, 2955–2970. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001665

Barrett, D. (2014, September 24). Mass shootings on the rise, FBI says. The Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/articles/mass-shootings-on-the-rise-fbi-says-1411574475

Brockelman, K. F., & Scheyett, A. M. (2015). Faculty perceptions of accommodations, strategies, and psychiatric advance directives for university students with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38, 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000143

Brunner, J. L., Wallace, D. L., Reymann, L. S., Sellers, J.-J., & McCabe, A. G. (2014). College counseling today: Contemporary students and how counseling centers meet their needs. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 28, 257–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2014.948770

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Credé, M., & Harms, P. D. (2015). 25 years of higher-order confirmatory factor analysis in the organizational sciences: A critical review and development of reporting recommendations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, 845–872. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2008

Downs, M. F., & Eisenberg, D. (2012). Help seeking and treatment use among suicidal college students. Journal of American College Health, 60, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.619611

Eells, G. T., & Rockland-Miller, H. S. (2011). Assessing and responding to disturbed and disturbing students: Understanding the role of administrative teams in institutions of higher education. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 25, 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2011.532470

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (5th ed.). SAGE.

Futo, J. (2011). Dealing with mental health issues on campus starts with early recognition and intervention. Campus Law Enforcement Journal, 41, 22–23.

Gallagher, R. P. (2015). National survey of college counseling centers 2014. http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/id/eprint/28178

Golightly, T., Thorne, K., Iglesias, A., Huebner, E., Michaelson-Chmelir, T., Yang, J., & Greco, K. (2017). Outreach as intervention: The evolution of outreach and preventive programming on college campuses. Psychological Services, 14, 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000198

Haines, A., Brown, A., McCabe, R., Rogerson, M., & Whittington, R. (2017). Factors impacting perceived safety among staff working on mental health wards. BJPsych Open, 3, 204–211.

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.117.005280

Hodges, S. J., Shelton, K., & King Lyn, M. M. (2017). The college and university counseling manual: Integrating essential services across the campus. Springer.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6, 53–60.

Iarussi, M. M. (2013). Examining how motivational interviewing may foster college student development. Journal of College Counseling, 16(2), 158–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2013.00034.x

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2016). Recognizing and supporting students with mental health disorders: The REDFLAGS Model. Journal of Education and Training, 3, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5296/jet.v3i1.8141

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2019). Peer-to-peer mental health support on community college campuses: Examining the factorial invariance of the Mental Distress Response Scale. Community College Journal of Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2019.1645056

Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Carlisle, K. L. (2019). Faculty members and college counseling: Utility of The REDFLAGS Model. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2019.1621230

Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Flinn, R. F. (2020). Development, validation, and cross-validation of the Mental Distress Reaction Scale (MDRS). Journal of College Student Development.

Kalkbrenner, M. T., & Sink, C. A. (2018). Development and validation of the College Mental Health Perceived Competency Scale. The Professional Counselor, 8, 175–189. https://doi.org/10.15241/mtk.8.2.175

Kleinfield, N. R. (2007, April 22). Before deadly rage, a life consumed by a troubling silence. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/22/us/22vatech.html?pagewanted=all

Lynch, R. J., & Glass, C. R. (2019). The development of the Secondary Trauma in Student Affairs Professionals Scale (STSAP). Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 56, 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2018.1474757

Margrove, K. L., Gustowska, M., & Grove, L. S. (2014). Provision of support for psychological distress by university staff, and receptiveness to mental health training. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38, 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.699518

Mvududu, N. H., & Sink, C. A. (2013). Factor analysis in counseling research and practice. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 4, 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150137813494766

Reetz, D. R., Bershad, C., LeViness, P., & Whitlock, M. (2016). The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors annual survey. https://www.aucccd.org/assets/documents/aucccd%202016%

20monograph%20-%20public.pdf

Resnicow, K., & McMaster, F. (2012). Motivational interviewing: Moving from why to how with autonomy support. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 19.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-19

Reynolds, A. L. (2013). College student concerns: Perceptions of student affairs practitioners. Journal of College Student Development, 54, 98–104. https://doi.org/ 10.1353/csd.2013.0001

Shuchman, M. (2007). Falling through the cracks—Virginia Tech and the restructuring of college mental health services. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp078096

Vanderhart, D., Johnson, K., & Turkewitz, J. (2015, October 2). Oregon shooting at Umpqua College kills 10, sheriff says. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/02/us/oregon-shooting-umpqua-community-college.html?smid=pl-share

Varshney, M., Mahapatra, A., Krishnan, V., Gupta, R., & Deb, K. S. (2016). Violence and mental illness: What is the true story? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 70, 223–225.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-205546

Vieselmeyer, J., Holguin, J., & Mezulis, A. (2017). The role of resilience and gratitude in posttraumatic stress and growth following a campus shooting. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000149

Warne, R. T. (2014). A primer on multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for behavioral scientists. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 19(17), 1–10.

Michael T. Kalkbrenner, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at New Mexico State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Michael Kalkbrenner, 1220 Stewart St., OH202B, NMSU, Las Cruces, NM 88001, mkalk001@nmsu.edu.

Mar 9, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 1

Kathryn Marburger, Sheri Pickover

Providing treatment to survivors of human trafficking requires mental health professionals to understand complex layers of multiple traumas. These layers include an understanding of how trafficking occurs; what gender, ages, sexual orientations, life circumstances, and ethnicities are most at risk to be trafficked; the lasting impact of trafficking on human development, mental health, and family relationships; and the stigma victims face from their own families, communities, and mental health providers. These survivors suffer from physical ailments and post-traumatic stress disorder, and they are at high risk for developing comorbid disorders such as depression and addiction disorders. Integrated treatment options to alleviate these concerns, including cognitive behavioral therapy, trauma-focused therapy, ecologically focused therapy, and family therapy, are presented.

Keywords: human trafficking, trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, addiction disorder, sexual orientation

Human trafficking is often referred to as modern-day slavery and is found in every corner of the globe (Cecchet & Thoburn, 2014; Department of Homeland Security [DHS], n.d.; Gerassi, 2015; Hardy et al., 2013; Hodge, 2014; Litam, 2017; Polaris, n.d.-b; Sanchez & Stark, 2014; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017). The United Nations defines trafficking as:

the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or

use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or

of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the

consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. (Office of the

High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2000, article 3, para. 1)

The International Labour Office (2017) has estimated that 40.3 million people are victims of modern-day slavery throughout the world. This means that one person in every 1,000 is being victimized through modern-day slavery. Offering high rewards with minimal risk, human trafficking is a profitable and fast-growing criminal enterprise. Human trafficking profits surpass illegal arms trafficking and are second only to drug trafficking (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014; Greer & Davidson Dyle, 2014; UNICEF USA, 2017). The International Labour Office (2014) has estimated that the profits from human trafficking are $150 billion a year, of which $99 billion comes from sexual exploitation.

The DHS reported that the crime of human trafficking is often hidden in plain sight in both legal and illegal industries; victims can be any gender, sexual orientation, age, and nationality, including documented or undocumented immigrants (DHS, n.d.; Rothman et al., 2017). However, statistics on human trafficking within the United States are lacking (DHS, n.d.; Gerassi, 2015; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Varma et al., 2015), and a uniform system of collecting data to identify victims currently does not exist, which increases the difficulty of obtaining accurate data (Gerassi, 2015; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017). Additional factors that contribute to the underreporting of human trafficking include legal and social services that are not readily accessible to victims, fear of punishment from traffickers, and fear or distrust of law enforcement. Moreover, some victims may not even recognize themselves as being the victims of human trafficking (De Chesnay, 2013; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017).

Human trafficking is a crime that inflicts complex layers of trauma on victims and survivors. The goal of this article is to provide mental health professionals with a systemic view of this crime from various perspectives so that they can implement wraparound-focused treatment plans. The perspectives adopted include how individuals become trafficked, sociocultural factors, the impact on the victims’ development and mental health, family relationships, and the stigma victims face from communities and their families. Having knowledge of these complex factors will allow mental health professionals to devise trauma-sensitive approaches to treat survivors of human trafficking. For the purpose of this paper, the term victims refers to individuals who are actively under the control of the trafficker, and the term survivors refers to individuals who are no longer being exploited.

Sexual exploitation and forced labor are two of the most common forms of human trafficking (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014; De Chesnay, 2013; Greer & Davidson Dyle, 2014; Hodge, 2014; Martinez & Kelle, 2013; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; U.S. Department of State, 2017). Human Rights First (2017) reported that 19% of human trafficking victims are trafficked for sex, and yet sex trafficking accounts for 66% of trafficking profits worldwide. Sex trafficking includes a wide variety of traditionally accepted forms of labor, including commercial sex, exotic dancing, and pornography. It is a form of oppression placing men, women, and children throughout the world at risk of sexual exploitation (Litam, 2017; Polaris, n.d.-a; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017).

Traffickers treat victims’ bodies as resources to be used and repeatedly sold for money or goods such as pornography, cigarettes, drugs, clothing, and shelter (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014; Greer & Davidson Dyle, 2014; Litam, 2017; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Sanchez & Stark, 2014). International trafficking often receives more attention; however, most trafficking occurs domestically within the same country (Martinez & Kelle, 2013; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017). Furthermore, trafficking does not have to include crossing a state line, nor does it necessarily involve moving locations (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014). Domestic minor sex trafficking is flourishing in every region, state, and community in the United States (Countryman-Roswurm & Bolin, 2014), with Midwestern cities showing increased rates of recruitment; such cities have access to several highways to transport victims to destination cities, including Detroit, Chicago, and Las Vegas, where demand for sexual exploitation is highest (Litam, 2017).

Sex trafficking has been linked not only to escort and massage services, strip clubs, and pornography, but also to major sporting events, entertainment venues, truck stops, business meetings, and conventions (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014; Hardy et al., 2013; Litam, 2017). As long as demand exists, the opportunity for traffickers to sell victims is limitless. The internet increases the convenience and reduces the risk for traffickers and consumers. For instance, although Backpage.com was shut down by the U.S. government in 2017 for participating in and profiting from sex trafficking advertisements, and other websites like Craigslist began to censor and remove sex advertisements (Anthony et al., 2017; Leary, 2018; Peterson et al., 2019), numerous websites are used by traffickers not only to lure victims but also to advertise and sell to consumers. These websites include Eros.com, Bedpage.com, and social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Tinder, and Grindr (Jordan et al., 2013; Litam, 2017; Moore et al., 2017; O’Brien, 2018). The physical and psychological abuse victims experience from both traffickers and consumers leaves victims traumatized (Graham et al., 2019; Greer & Davidson Dyle, 2014; Litam, 2017; Moore et al., 2017; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017).

The Victims of Trafficking

One out of every four victims of human trafficking is a child (International Labour Office, 2017), and these children are often found in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, and runaway and homeless youth shelters (Moore et al., 2017; U.S. Department of State, 2017). In 2016, it was estimated that one out of six runaways was a victim of sex trafficking and 86% had been in foster care or social services when they ran away (Polaris, n.d.-a). Runaway youth are usually approached by traffickers within 48 hours of living on the street (Jordan et al., 2013). Traffickers recruit runaway or homeless children into trafficking rings, exposing them to extreme forms of abuse that result in many being killed from the violence inflicted or from diseases acquired through sexual abuse (Litam, 2017).

Sex trafficking is prevalent throughout the world, affecting men, women, children, families, and communities. Individuals also are trafficked for various other purposes, including domestic service, agricultural work, commercial fishing, the textile industry, construction, mining, factory work, and petty crime (U.S. Department of State, 2017; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017). Although men have been confirmed to be victims in all areas of trafficking, they are disproportionately subjected to forced labor, whereas women and children account for the majority of sexually exploited victims (International Labour Office, 2017). Although trafficking occurs in all parts of the world and can affect anyone, several factors increase the risk of trafficking, including gang activity, a history of childhood abuse, and poverty. Substance abuse also plays a key role (De Chesnay, 2013; Moore et al., 2017; O’Brien, 2018).

Addiction

Substance abuse within families is a risk factor for children becoming the victims of trafficking (Hardy et al., 2013; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017). Parents or other family members with an addiction can force youth into sexual exploitation, selling or trading them to support their drug addiction (De Chesnay, 2013; Litam, 2017). Traffickers often force substance use on victims in order to control and sexually exploit them (De Chesnay, 2013; Gerassi, 2015; Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Litam, 2017; Moore et al., 2017). Substance abuse also may be a way for trafficking victims to cope with the abuse they endure (Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017).

Trafficking victims who engage in substance abuse usually experience detrimental personal outcomes, including an increased likelihood of engaging in high-risk behaviors (i.e., unprotected sex), infection from needles, and overdosing (Gerassi, 2015; Zimmerman et al., 2011). They often commit drug-related crimes for their trafficker and are therefore at risk of arrest and conviction for prostitution and drug offenses (Litam, 2017; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Zimmerman et al., 2011). Arrests, drug charges, substance abuse, and violent clients can trap trafficking victims in a vicious circle of re-traumatization by their traffickers, their potentially abusive consumers, and the criminal justice system (Gerassi, 2015; Zimmerman et al., 2011).

Impact on Physical and Mental Health

A concern for children who fall prey to sex trafficking is the impact these experiences have on their development. Not only are victims affected by educational deprivation, but trafficking also causes serious harm to their psychological, spiritual, and emotional development (Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Rafferty, 2008; Sanchez & Stark, 2014). Child victims suffer from an increased risk of several emotional problems such as guilt, shame, anxiety, hopelessness, and loss of self-esteem (Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Rafferty, 2008). Some of the mental health consequences for child victims include depression, dissociation, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), eating disorders, somatization, poor attachment, antisocial behaviors, substance use disorders, self-harm, and suicidality (Kiss et al., 2015; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Rafferty, 2008). Furthermore, because of the exposure to the violence and sexual assault linked to trafficking, child victims have been found to be at higher risk of sexually transmitted infections, reproductive health problems from unsafe abortions, fractures, genital lacerations, malnutrition, and dental problems (Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017).

Trafficking poses significant risk to child victims’ long-term mental health. Survivors trafficked in childhood report a high prevalence of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD. These mental health problems also affect adult victims (Hom & Woods, 2013; Oram et al., 2016). Among women who have survived trafficking, there are increased rates of anxiety and stress disorders, disassociation, depression, personality disorders, low self-esteem, suicidal ideation, and poor interpersonal relationships (Sanchez & Stark, 2014). Additionally, somatic symptoms such as headaches, fainting, and memory problems are commonly reported among women who are victims of trafficking (Oram et al., 2016). A high prevalence of sexually transmitted infections has been reported in both men and women (Hom & Woods, 2013; Oram et al., 2016; Sanchez & Stark, 2014). Borschmann et al. (2017) found high rates of self-harm among adult victims of human trafficking.

Pregnancy is a common occurrence for trafficked women (Bick et al., 2017; Gerassi, 2015; Hom & Woods, 2013; Oram et al., 2016; Sanchez & Stark, 2014). Several barriers to maternity services have been identified for pregnant victims, including traffickers preventing women from seeking care and the victims feeling reluctant because they might not have valid documents (Bick et al., 2017). Additionally, children and family members are often used by traffickers to threaten and coerce victims, which further isolates victims and distances them from their families (Hardy et al., 2013; Hodge, 2014; Juabsamai & Taylor, 2018; Sanchez & Stark, 2014).

Sex trafficking often involves the exploitation of victims by force, and the brutal nature of the crime can cause complex mental health problems for victims (Gerassi, 2015; Greer & Davidson Dyle, 2014; Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Litam, 2017). Victims endure high levels of trauma, and survivors show increased rates of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and substance use disorders (Gerassi, 2015). The goal of traffickers is to physically and psychologically break victims down into subservience (Hodge, 2014). Not only are victims forced to engage in humiliating sexual acts and use substances, but traffickers also use recurrent beatings, rape, and even murder as tactics to control their victims (De Chesnay, 2013; Gerassi, 2015; Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Litam, 2017). Victims may believe that the traffickers have their best interests in mind and develop significant bonds with their traffickers, similar to Stockholm syndrome, and may be reluctant to escape (De Chesnay, 2013; Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Litam, 2017). In addition, victims of sexual exploitation have not only endured physical and emotional abuse from their traffickers, but there also is a strong correlation with childhood abuse (Gerassi, 2015; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017). However, issues of physical and mental health tend to be exacerbated by issues of economic deprivation and racial inequality. These factors may act as a catalyst for putting individuals more at risk of human trafficking (Greer, 2013).

Multicultural Considerations

Sex traffickers often target vulnerable individuals, including runaway and homeless youth; victims of domestic abuse or sexual assault; victims of war; and individuals who experience social discrimination, including gender, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequality (Anthony et al., 2017; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017). For example, LGBTQ homeless youth account for 20% of the homeless youth population in the United States, yet 58.7% of homeless LGBTQ youth are victims of sex trafficking (Martinez & Kelle, 2013). Martinez and Kelle (2013) further noted that this figure is significantly higher than the 33.4% of the heterosexual homeless youth. Furthermore, LGBTQ youth are more than seven times more likely to experience acts of violence than their cisgender peers (Anthony et al., 2017). Trafficking often affects victims of poverty. Studies of sexual exploitation and domestic sex trafficking also have reported higher rates of violence against women of color, especially African American women, and undocumented immigrants (Gerassi, 2015; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017).

Finally, individuals with intellectual disabilities are at risk because of an unfamiliarity with sexual activities and an inability to understand the nature of sexual abuse and exploitation (Reid, 2018). As a result, such individuals are at a higher risk of becoming victims of trafficking (Greer & Davidson Dyle, 2014; Hodge, 2014; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Reid, 2018).

Returning Home

Women who have been victims of trafficking have often been found to come from abusive households (Gerassi, 2015; Hom & Woods, 2013; O’Brien, 2018; Oram et al., 2016). As a result, once victims are free from their traffickers, they have often been found to not only lack social support but also lack basic needs such as shelter and financial support (Hom & Woods, 2013; Le, 2017; Oram et al., 2016). Reconciliation with supportive family often plays a key role for trafficking survivors; however, because of stigma, some victims are met with shame and judgment from their families and are not welcomed (Hom & Woods, 2013; Juabsamai & Taylor, 2018; McCarthy, 2018; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017).

Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for victims to be exploited by someone they know and love. Oftentimes a trafficker is a family member, intimate partner, friend, or acquaintance (Gerassi, 2015; Hardy et al., 2013; Hom & Woods, 2013; Le, 2017; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Moore et al., 2017), which further complicates survivors’ ability to establish trusting relationships. Moreover, law enforcement may charge adult victims with prostitution. Not only is the victim caught in legal limbo, but they are re-victimized by law enforcement (Sanchez & Stark, 2014). Finally, female survivors who socialize with men after being freed from their traffickers have reported being triggered with memories of their abusive experiences, further affecting their ability to develop healthy, stable relationships and social support (Hom & Woods, 2013).

Victims of human trafficking have often been robbed of their identities, had their self-esteem demolished, and already experienced physical and psychological abuse before they became victims of human traffickers. Once they leave their traffickers, survivors have a variety of immediate, short-, and long-term needs that must be addressed to help promote resiliency while they are reintegrating into the community (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014; Graham et al., 2019; Hom & Woods, 2013; Le, 2017; McCarthy, 2018; O’Brien, 2018; Twigg, 2017). Immediate needs include ensuring safety; finding medical care, food, shelter, clothing, and counseling; and acquiring identification, language interpretation services, and legal and immigration assistance (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014; Graham et al., 2019; Hom & Woods, 2013; McCarthy, 2018; Polaris, n.d.-a; Twigg, 2017). Education, employment, and establishing friendships have been identified as vital ongoing needs to successfully alleviate stress while reintegrating into the community (Hom & Woods, 2013; McCarthy, 2018; O’Brien, 2018; Polaris, n.d.-a; Twigg, 2017). However, it is important to note that survivors are often met with substantial challenges while seeking basic services. For instance, many programs may be underfunded or ill-equipped to handle the high demand for services (Polaris, n.d.-a). This reaffirms the crucial need to meet survivors with empathetic and nonjudgmental attitudes to help prevent re-victimization and a return to traffickers (Anthony et al., 2018; Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; McCarthy, 2018).

Family support can provide survivors with significant protection while reintegrating into the community. Reconnecting with family typically increases the likelihood of a sustainable return process (McCarthy, 2018; Twigg, 2017). However, reconciliation might require a careful approach, as the process can be met with difficulties, including stigma, dysfunctional family environments, or the family’s direct involvement with the victim’s trafficking (Le, 2017; McCarthy, 2018; Twigg, 2017; Zimmerman & Kiss, 2017). In some cases, shame within a cultural context is a prohibitive factor for many to return to their families because of the association with prostitution or having been trafficked (Hom & Woods, 2013). As a result, it is necessary to provide comprehensive, culturally sensitive interventions for trafficking survivors (Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Le, 2017; McCarthy, 2018). Family continues to be essential to survivors’ sense of identity, and, upon return, cultural beliefs and values that previously formed their self-concept remain influential to survivors (Le, 2017). Many women have noted that marriage and children play an integral role in successfully reintegrating into their community and gaining acceptance from family members (McCarthy, 2018). However, issues of economic deprivation and racial inequality act as a barrier to successful community reintegration and put an individual at higher risk for trafficking (Greer, 2013).

This brief literature review has confirmed that victims of human trafficking suffer from a wide array of mental health concerns, including PTSD, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, and from stigma associated with being victims of human trafficking. Mental health treatment should address these complex concerns and provide for comprehensive assessment and treatment planning.

Treatment Challenges

Working with trafficked clients poses a series of challenges for counselors because an intervention modality specific to sex-trafficked survivors has yet to be developed (Hopper et al., 2018; Jordan et al., 2013). Treatments are borrowed from evidence-based interventions initially developed for PTSD, domestic violence, and captivity, and a holistic approach is essential (De Chesnay, 2013; Hom & Woods, 2013; Jordan et al., 2013). Four essential practices for providers include ensuring safety and confidentiality, engagement of trauma-informed care, performing a comprehensive needs assessment, and delivery of comprehensive case management that coordinates physical and mental health and legal services. As a result of the multiple traumas trafficking victims endure, the path to restoring wellness is often long and complex, requiring additional time and patience from mental health counselors (Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013).

Mental health counselors should conduct a needs assessment to identify the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of trafficking survivors (Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013). Survivors are often in need of medical treatment, as traffickers do not bother with preventative care or what they may consider minor treatment and only allow victims to seek treatment when a condition interferes with earning money (De Chesnay, 2013). Similarly, survivors are often resistant to seek help from mental health providers because of fear of physical violence or threats of retaliation from their traffickers if they disclose their circumstances (De Chesnay, 2013; Hodge, 2014; Litam, 2017). Survivor-centered approaches are recommended initially to acknowledge and validate the survivor’s experience, give the survivor control, and build a sense of safety and trust (Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Twigg, 2017).

However, after months or years of abuse, trafficking survivors often need a wide array of services to meet their distinctive needs (Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; McCarthy, 2018; Polaris, n.d.-a). The U.S. government has enacted several policies to help victims of trafficking, including the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, which allows victims who have been trafficked from abroad to be issued visas, enabling them to reside in the United States (Davy, 2016; Hodge, 2014). Survivors need to be met with nonjudgmental attitudes, acceptance, understanding, and genuine concern, and they should be slowly encouraged to take on risks associated with leaving their traffickers (Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; McCarthy, 2018). Providing survivors with emotional support and encouragement opposes the isolated world created by their trafficker. Survivors have explained that street outreach programs can play an essential role in establishing contact, allowing victims to become aware of the resources available and begin breaking down the sense of isolation (Hom & Woods, 2013). Additionally, it is vital to empower survivors so that they can understand they are in control (Anthony et al., 2018; Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Twigg, 2017). Research on resiliency has found creativity, humor, flexibility, and movement are important factors in improving self-esteem, prosocial behaviors, and hope among traumatized individuals (Litam, 2017).

Evidence-Based Treatment

Counselors working with trafficking survivors should be equipped to use several trauma-sensitive interventions to assist with the individual needs of each survivor (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2014; De Chesnay, 2013; Hardy et al., 2013; Hodge, 2014; Hom & Woods, 2013; Litam, 2017; Miller-Perrin & Wurtele, 2017; Twigg, 2017). Trauma-sensitive interventions recognize safety as the foundation for working with individuals to end self-harm, develop trusting relationships, overcome obstacles, leave dangerous situations, and promote wellness (Hopper et al., 2018). Although it may be painful for trafficking survivors to verbalize their traumatic experiences, creative therapies offer alternative methods of communication and expression (De Chesnay, 2013; Litam, 2017).

Although evidence-based practices for treating sex-trafficking survivors are not widespread, counseling techniques exist that have been shown to be effective with child sex abuse victims, including trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy (De Chesnay, 2013; Twigg, 2017). Similarly, participating in group counseling can empower survivors of sex trafficking and provide them with an opportunity to share their experiences, generating a sense of community and support (Hopper et al., 2018). Peer support has been noted to be a vital component of intervention, both as a motivating factor to remain in treatment and as help in the prevention of survivors returning to their traffickers (De Chesnay, 2013; Litam, 2017; Twigg, 2017). Furthermore, discussing stigmatized topics within group settings can help reduce shame, as it is common for trafficked survivors to feel that no one else has gone through similar situations (Hickle & Roe-Sepowitz, 2014; Litam, 2017). Having a setting to address the shame can help survivors recognize the commonality of their experiences and build support (Countryman-Roswurm & Bolin, 2014; Litam, 2017).

Family Therapy

As human trafficking affects individuals, families, and communities, it is necessary to adopt treatment models that engage families and communities as well as individual-based treatment models. Twigg (2017) found that survivors require and benefit from therapeutic support in order to achieve successful family and community reunification. However, like individual treatment, family therapy models specific to human trafficking survivors do not exist, but current family therapy models developed around trauma could be adapted for use with human trafficking survivors. Apsche et al. (2008) developed Family Mode Deactivation Therapy, a cognitive behavior family therapy model for use with youth and families in residential treatment that uses ongoing assessment and community skill development to reduce the behavioral symptoms associated with trauma. The researchers found this model reduced recidivism more effectively than a non–family-based approach. Hughes (2017) developed an attachment-focused family treatment for children who have experienced developmental trauma. This two-phase treatment provides therapy to a caregiver first, then transitions to joint sessions to reframe the trauma experience.

Similarly, using ecologically based family therapy with individuals involved in sex trafficking has been found to improve outcomes for sobriety and depression (Murnan et al., 2018). Agani et al. (2010) recommended the use of the linking human systems community resilience model, which is based on transgenerational and ecosystemic structural family therapies. This model focuses on identifying the strengths of community and family members, bringing them together to encourage their competency and using community leaders to solve problems. Other novel approaches to working with survivors of crime include the Family Group Project, which involves group therapy aimed at recreating a family environment to re-integrate survivors into the community (Allen et al., 2015).

A Survivor’s Story

Research provides one perspective on the plight of human trafficking victims and survivors, but a first-person account provides insight to the worldview of an actual survivor. One of the authors met with a human trafficking advocate in order to gain further perspective on the needs of survivors. The advocate, who requested that the author provide no identifying information beyond her gender, disclosed during the interview that she was a survivor who had been trafficked by her husband. Her trafficker had been blackmailing a John, a term commonly used for an exploitive consumer. She was arrested during a raid and remained in jail for 3 months because she refused to say anything. She explained that it took her a year to build up the strength and courage to testify in court because her trafficker blackmailed her. He threatened to tell her family about the exploitative acts and substance use, which he forced her to engage in. He would say, “Do you really want your family to know what you have been up to?” However, once her family was notified of her predicament, she reported that her family members provided emotional support. She explained that it was through their support she was able to come forward and testify.

Although she came forward and testified against her trafficker, she was not viewed as a victim, and she was charged with prostitution. As she explained, advocates are trying to change the legislation and work with police in her local area so that human trafficking victims are not charged with crimes. For instance, not only was she charged with prostitution, but she also had to pay the John $3,000, the money her trafficker had stolen from him. Despite never having seen the money, she was ordered to repay it and was placed on a repayment schedule. Even more disheartening, her trafficker made a plea deal and did not have to repay any money and the charges of trafficking were dropped. All these events provide an example of how the legal system can re-victimize a survivor. Although she had been the victim of trafficking, which stigmatized her, she also was told that she owed money to someone her trafficker had stolen from, thus re-victimizing her.

The charge of prostitution remained on her record and became something she had to explain to potential employers. With the support of her family and by attending therapy, she was able to rebuild her life. She had a bachelor’s degree in social work when she met her ex-husband and was able to obtain her limited license. She decided to pursue a master’s degree and was once again faced with the challenge of disclosing the charge on her record and reliving the trauma of explaining what happened. The first university she applied to denied her application, and this placed her in a deep depression; however, she was accepted at another university and after graduating became an advocate for survivors of human trafficking. She also shared that although it took time to be able to trust someone again, she has established an intimate relationship and will soon be married.

Conclusion

Counselors treating a human trafficking survivor need to develop a wide-ranging view of assessment, treatment, case management, support, advocacy, and termination from counseling. Human trafficking survivors suffer from a complex variety of developmental, mental health, and social issues that require counselors to not only engage the individual in treatment, but also to act as an advocate against stigma within their family and the community.

The myriad of issues faced by these individuals, from navigating the criminal justice system, coping with multiple layers of physical and emotional trauma, overcoming substance abuse, overcoming family and community alienation, coping with dual stigmas of human trafficking and mental health diagnoses, to finally reintegrating into daily work and life, require counselors to be vigilant in the assessment process. Counselors need to consider assessment an ongoing extensive process that should occur throughout every session and focus not just on mental health needs, but also on physical health and basic needs, and career support. Counselors will need to assess risk of the individual returning to the trafficker and have referrals ready to help the client stay safe. Human trafficking survivors will need a counselor able to quickly identify short-term crisis needs during long-term treatment.