Nov 30, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 4

Joshua D. Smith, Neal D. Gray

This interview is the fourth in the Lifetime Achievement in Counseling Series at TPC that presents an annual interview with a seminal figure who has attained outstanding achievement in counseling over a career. I am honored to present the interview of Liliana Sznaidman, a professional counselor in North Carolina. Ms. Sznaidman is the second practitioner to be interviewed for this annual series. Ms. Sznaidman is a licensed professional counselor and licensed professional counselor supervisor with over 20 years of clinical experience. She is currently the principal owner of a private practice where she provides counseling, clinical supervision, and consultation services. Joshua Smith and Dr. Neal Gray graciously accepted the assignment to interview Ms. Sznaidman. What follows are Ms. Sznaidman’s reflections on her counseling career and its impact on her clients. —J. Scott Hinkle, Editor

Liliana Sznaidman has over 20 years of experience as a licensed professional counselor (LPC) and licensed professional counselor supervisor (LPCS) in North Carolina. She currently owns a private practice where she provides counseling and psychotherapy to adults, couples, and young adult clients. She also provides clinical supervision and consultation services to pre-licensed counselors and other mental health professionals.

Liliana Sznaidman has over 20 years of experience as a licensed professional counselor (LPC) and licensed professional counselor supervisor (LPCS) in North Carolina. She currently owns a private practice where she provides counseling and psychotherapy to adults, couples, and young adult clients. She also provides clinical supervision and consultation services to pre-licensed counselors and other mental health professionals.

Ms. Sznaidman received her master’s degree in counseling at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Prior to her master’s training, she completed a degree in early childhood education in Buenos Aires, Argentina. In addition to her LPC and LPCS, Ms. Sznaidman holds the credentials of National Certified Counselor and Approved Clinical Supervisor. She also has completed post-master’s training in clinical supervision and has received extensive training in psychoanalytic theory and practice.

Before going into private practice, Ms. Sznaidman worked as an outpatient psychotherapist providing family counseling services, and as a bilingual therapist. Ms. Sznaidman has been an advocate and asset to her community. She has conducted and co-facilitated psychoeducational groups in Spanish for Latinx adolescents and assisted in providing case management and referrals. Ms. Sznaidman has demonstrated service to the profession by serving as a field placement supervisor for master’s-level student interns and provided professional presentations to community agencies.

Ms. Sznaidman is a member of several professional organizations, including the Licensed Professional Counselors Association of North Carolina (LPCANC), where she was the president of the board of directors and helped to advocate for the inclusion of LPCs in continuing education opportunities. She also created the first mentoring program in the association. Ms. Sznaidman is an active member of the American Mental Health Counselors Association (AMHCA); the Pro Bono Counseling Network for Durham, Orange, Person, and Chatham Counties; and the Psychoanalytic Center of the Carolinas. Ms. Sznaidman received both the 2009 Distinguished Practitioner Award and the 2013 Alumni Distinguished Service Award from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and was named 2014 Mental Health Counselor of the Year by AMHCA.

In this interview, Ms. Sznaidman shares beneficial insights into her career, her approach to counseling, growth and changes within the counseling profession, her involvement in professional organizations, and the future development of the profession.

- As an LPC and LPCS in North Carolina, what led you to pursue a degree in

counseling compared to other helping professions?

It was in my late high school years when I began to think about engaging in a helping profession due to personal experiences receiving such help and becoming increasingly curious about the human mind.

However, political unrest in my country of origin, Argentina, followed by a couple of moves back and forth to the United States, veered my career in a different direction and affected a delay of my initial plans. It was after I settled more permanently in the United States that a counseling career became a reality.

After examining other specialties within the mental health profession, I decided to pursue professional counseling due to its predominant academic and practice emphasis on the provision of services to clients. Other disciplines seemed to divide their focus between this and macro work in communities, or psychological testing, which was not appealing to me in either the academic or practice realms.

- As a bilingual counselor with clinical interests in diversity and cross-cultural

counseling, what have been your perceptions and observations regarding

multicultural competency in counseling?

I recall taking a multicultural course in graduate school and truly appreciating it, based on how it set the tone for challenging the notion of mainstream cultural values being the guiding principle for helping clients, and erroneous, stereotypical assumptions about other cultures. Yet, it was quite surprising to witness thereafter that more emphasis was not placed on postgraduate continuing education opportunities in multicultural competency.

It seems to me that multiculturalism may be erroneously considered a specialty, particularly in today’s society where cultural differences are embedded in many client–therapist dyads. If we conceptualize multicultural nuances in a more expansive manner, even aspects as subtle as having had an urban upbringing compared to being raised on a farm, it might lead to richer exploration and meaning making in the context of working with clients.

Our profession and the counseling field overall would benefit from incorporating multicultural aspects into virtually every realm of training, rather than considering it a separate and unique body of knowledge. By not doing so, we might shortchange the overall growth of our profession in this area and limit how we serve our clients.

3. As a licensed counselor for over 20 years, what in your opinion are the biggest

changes within the profession? How have these changes impacted your work as a

clinician? Conversely, what are the biggest barriers facing counselors right now?

This is a very good topic to explore because it is easy for professional counselors to forget when there used to be little respect for our profession, despite our graduate training being comparable to that of others in the mental health field. The mental health professional world and the public at large knew very little about our training and our professional license. As a result, employers were quite wary about considering us in their hiring opportunities overall, and particularly while candidates were still accruing full licensure status. Health insurance companies, including those federally or state funded, were not accepting our licensed clinicians on their provider panels.

Being fully aware that the nature of our profession’s historical presence may vary from state to state, I can only speak of it based on my experience practicing in North Carolina. Thanks to the work of a handful of dedicated colleagues, professional counselors gradually but steadily gained acknowledgment by prospective employers and attained full third-party reimbursement status from insurance companies that operate within the state. In North Carolina, we were among the first in the field to institute distinct formal licensing tiers for associate, fully licensed, and supervisory levels. This offers a way to clearly reflect differential levels of training within our profession. However, it is evident that more work needs to be done by our professional associations in educating the public at large about who we are, how we are trained, and what exactly each of these tiered licensure levels means.

Nationally, of course we know that Medicare recognition is the next desired achievement, but we have certainly come a long way as a profession. It behooves us all to look back in gratitude in order to look forward to new horizons. Lastly, I want to say how encouraging it is to see the impetus of several national organizations working together toward a more cohesive licensing nomenclature and criteria, as well as reciprocity across states. Implementing uniformity in licensing standards can only benefit all of us in attaining increased professional recognition throughout the United States.

Witnessing the profession evolve and change throughout the years has been both encouraging and at times concerning. Particularly in private practice, the salient point is the impact of increasing administrative requirements and treatment barriers placed by insurance companies, while compensation for counseling services has remaining unchanged or lowered for over 15 years. Over time, insurers established a fee-for-service model that has resulted in a decline in previously available salaried employment opportunities, giving way to contract-based type arrangements. This model may pose many challenges to new graduates who may not feel fully ready to venture on their own into private practice, while also finding percentage fee-for-service remuneration positions financially unsustainable. At the state level, we also have seen a significant transformation involving the transition of publicly funded county mental health clinics to outsourcing management and provision of all services to large private sector companies. This, too, has impacted the nature of the job market for counselors.

Overall, we have seen an increase in new graduates starting out in private practice immediately after graduation, but for some this might be too soon or too daunting. I think that graduate programs can help pave the way by a two-fold approach: providing students with at least the basics of practice management skills and impressing upon them the importance of ongoing supervision and consultation with peers. It is no secret that private practice can at times feel isolating; thus establishing regular contact with colleagues for support and consultation can make a significant and positive impact.

- I see that you operate from a psychodynamic approach, both as a clinician and as a

supervisor. What does that approach mean to you in each of these roles?

Psychoanalytic psychotherapy operates under the premise that through exploration of the unconscious, conflicts take place. It also works by utilizing transference and countertransference in the client–counselor relationship to identify common threads in people’s lives. Analytic therapy is often criticized in part due to the length of treatment intrinsic to this orientation, misconceptions about it being solely rooted on antiquated and outdated theory and practice, as well as the therapist’s role being perceived as less active. However, contrary to many beliefs, there is a significant body of research in its efficacy and long-term sustained gains, in addition to its well-known years of historical practice and evolving theoretical contributions.

In my work with clients, I try to guide them to identify common themes, which when brought to the conscious level, begin to form a cohesive narrative of the person’s life that they may not have previously realized. In supervision, I attempt to help my supervisees identify themes in their clients, while also remaining attentive to what emerges within them in the context of that dyadic relationship. It is meaningful, transforming work that does not focus on presenting symptoms alone, but rather on the underlying roots most often unbeknownst to the client and on affecting long-lasting change for self-fulfilling lives.

- What has been your experience when interacting with national and local counseling

organizations? Do you feel supported by professional organizations and leaders?

Has support changed in the last 20 years?

I was active for many years within professional organizations, including serving on a state chapter association’s board of directors, LPCANC, for approximately five years. The work of these organizations is remarkable, as are their attainments. I think it was fortunate that my graduate program placed so much emphasis on involvement in these organizations. It was discussed in classes, in workshops, and certainly modeled by faculty in the program. I met our regional association leaders for the first time in one such workshop, and that experience truly made an impression on me as a student. The learning, networking, and growth opportunities that this involvement affords us is likely not available in any other aspect of our professional careers and is invaluable.

- Throughout your years of practice, what has been the role of counselor identity,

and has that changed over time?

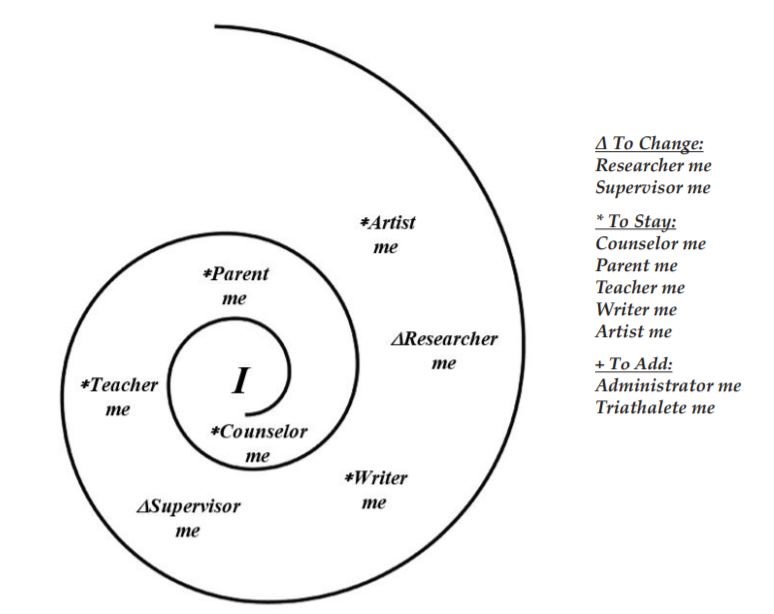

It has been interesting to me to witness my own journey within the profession throughout the years. Certainly, most of us work on getting better at and more experienced in what we are trained to do. It was interesting to me to see this focus and role expand and morph, venturing in different directions, such as advocacy and involvement in professional associations, more intensive clinical training, mentoring and training others via clinical supervision, and combining all of these in my professional life.

- For future counselors, what advice would you have regarding their involvement in

advancement and future development of the profession?

As I mentioned earlier, it was through the work of our dedicated colleagues that we attained the recognitions we now have, and yet more work always needs to be done. It is important that we as a profession make inroads in increasing salaried employment opportunities for our new graduates, as we still witness some hospitals, specific departments, university counseling centers, and the like that do not include professional counselors in their hiring practices. Counselors can certainly enter private practice at any juncture in their career, even while under supervision. Yet, based from my own experience, there is not much better learning than that which takes place when you witness the day-to-day practice of professionals more senior to you. This in my mind translates into full-time employment where excellent role models are available.

Another important aspect of advancing in the profession stems from engaging in lifelong learning and some of the best ways to do so are through continuing education and ongoing supervision. It is not uncommon for new counselors to experience supervision as such a financially burdensome mandate throughout their restricted license period that they tend to discontinue it immediately after full licensure is attained. I see this as depriving themselves of ongoing growth. Clinical supervision can take many different forms and frequency levels after graduation, but it remains an invaluable source of ongoing learning. It has been my own personal choice to remain in some form of clinical supervision throughout the entirety of my 20+ year career thus far, and I have never regretted it.

I would also encourage new counselors to engage in professional associations, volunteering and advocating from the outset. It may seem daunting to have that responsibility on top of learning their way as new professionals. However, it is crucial they know there will most likely be someone in those associations ready to guide them in this endeavor, and as the saying goes, “many hands make light work.”

This concludes the fourth interview for the annual Lifetime Achievement in Counseling Series. TPC is grateful to Joshua D. Smith, NCC, and Dr. Neal D. Gray for providing this interview. Joshua D. Smith is a doctoral student in counselor education and supervision at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Neal D. Gray is a professor and Chair of the School of Counseling and Human Services at Lenoir-Rhyne University. Correspondence can be emailed to Joshua Smith at jsmit643@uncc.edu.

Nov 29, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 4

Ariann Evans Robino

Explanations of compassion fatigue generally consider the client–counselor relationship as the primary source of challenges to wellness. Because of the nature of the current sociopolitical climate and the increased exposure through media, the counseling profession should consider expanding the influences on compassion fatigue related to current events. This article introduces the concept of global compassion fatigue (GCF), a phenomenon that provides an opportunity for counselor self-awareness. Implications for adopting GCF into the counselor impairment literature include understanding how global events impact counselor development and clinical practice as well as the importance of maintaining a wellness lifestyle to protect against its effects. Counselors’ involvement in advocacy and social justice are also explored as contributors to GCF.

Keywords: global compassion fatigue, counselor impairment, advocacy, self-awareness, wellness

Counselors and counselors-in-training (CITs) feel the weight of societal stressors. According to the ACA Code of Ethics, “promoting social justice” (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014, p. 3) is a core value of the counseling profession. Furthermore, because of its impact on the profession, scholars have declared social justice as the fifth force in counseling (Ratts, 2009; Ratts, D’Andrea, & Arredondo, 2004). Representatives from ACA have acted in accordance by addressing the federal government’s recent prohibition of specific language associated with diverse populations (Yep, 2017) as well as releasing a statement of support shortly after the 2016 presidential election calling on all counselors to remain strong in their beliefs and actively assist those in need (Roland, 2016). Similarly, the closing keynote speaker at ACA’s Illuminate Symposium on June 10, 2017, Dr. Cheryl Holcomb-McCoy, encouraged attendees to take action against human rights offenses through vocal opposition in multiple settings, including social media (Meyers, 2017). These positions demonstrate the desired role of counselors to engage in advocacy and activism for global issues.

Natural disasters, threats to civil rights, violence, terrorist attacks, and animal welfare concerns are simply a few of the powerful issues that humans face as highly social and emotional beings. Although advocacy is one avenue of handling the emotional unrest related to these events, the complex nature of counselors’ personal and professional identities presents an invitation to consider these sensitive issues currently faced by society. Professional counselor identity allows counselors to make meaning of their work during these times of strong emotion (Solomon, 2007). Considering how these events affect both counselors’ and CITs’ personal lives and clinical practice produces opportunities for counselor professional development and greater self-awareness. The purpose of this article is to explore global compassion fatigue (GCF), a phenomenon related to the human condition and how global events impact professional counselors and other helpers. This article begins with a review of current counselor impairment concepts as well as the role of wellness in managing these conditions. Then, the reader is introduced to GCF and how a review of the literature supports the examination of this new concept. Next, I provide a detailed conceptualization of the phenomenon and implications for the field. Finally, suggestions for future research are provided.

Understanding Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue research spans the literature of multiple disciplines, including nursing, social work, and counseling (Compton, Todd, & Schoenberg, 2017; Lynch & Lobo, 2012; Sorenson, Bolick, Wright, & Hamilton, 2016). Counselors typically understand compassion fatigue as an event occurring as a result of counselor–client interaction. Charles Figley (1995) first defined the concept of compassion fatigue as “a state of exhaustion and dysfunction—biologically, psychologically, and socially—a result of prolonged exposure to companion stress and all that it evokes” (p. 253) and conceptualized it as a response to the emotional demands of hearing and witnessing stories of pain and suffering. Symptoms of compassion fatigue include re-experiencing the client’s traumatic event, avoidance of reminders of the event and/or feeling numb to those reminders, and persistent arousal (Figley, 1995). Researchers carefully note the differences between compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization, and burnout (Lawson & Venart, 2005; Meadors, Lamson, Swanson, White, & Sira, 2010). Vicarious traumatization, defined as a significant altering of cognitive schemas and a disruption of an individual’s sense of identity, worldview, and meaning, occurs as a result of empathic engagement with the traumatic experiences of a client (McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Vicarious traumatization symptoms involve a more covert change in thought and cognitive schema rather than an observable experiencing of symptomatology (Jenkins & Baird, 2002). Burnout is a process that occurs because of occupational stressors such as high caseloads, low morale, and minimal support (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). It is associated with emotional exhaustion, strain, and overload in addition to a reduction in personal accomplishment and job satisfaction (Maslach, 1982). Counselors are more likely to experience compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization, and burnout when they have a previous history of personal trauma (Baird & Kracen, 2006), high emotional involvement with clients (Adams, Boscarino, & Figley, 2006), fewer perceived coping mechanisms (Baird & Kracen, 2006), and lower self-awareness (P. Clark, 2009). However, the goal of this article is to expand upon the phenomenon of compassion fatigue as distinguished from these other explanations of impairment to understand better how global events outside of the counselor–client dyad impact counselors. Although other impairment concepts hold value and applicability to counselors, compassion fatigue and its relationship to emotional suffering as a result of a desire to help others most closely aligns with the concept presented in this article. When considered in the context of counselors, an awareness of compassion fatigue, its effects, and how to mitigate those effects is vital for client welfare.

Counselor Impairment and Wellness

According to the ACA Code of Ethics, counselors should “monitor themselves for signs of impairment from their own physical, mental, or emotional problems” (ACA, 2014, p. 9). The ACA Code of Ethics dedicates an entire section to counselor impairment (C.2.g.), which states that, in the interest of client protection, counselors should cease providing services while impaired, seek assistance to solve issues of impairment, and assist colleagues and supervisors in recognizing and rectifying their own impairment (ACA, 2014). When counselors are impaired, it can result in significant harm to clients through an interference with the counseling process, trust violations, and ethical breaches (Lawson, Venart, Hazler, & Kottler, 2007). Adopting an alternative lens for viewing the impairment literature presents an opportunity for counselors to monitor themselves and others for potential issues as indicated by the ACA Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014). In addition, the ACA Code of Ethics guides counselors to “engage in self-care activities to maintain and promote their own emotional, physical, mental, and spiritual well-being to meet their professional responsibilities” (ACA, 2014, p. 8). As self-advocacy for wellness can promote better professional practice within the counseling community (Dang & Sangganjanavanich, 2015), counselors are encouraged to avoid and rectify issues of impairment through positive, health-promoting strategies.

Recognizing this area of need within the profession, ACA established the Taskforce on Counselor Wellness and Impairment in 2003 to address the needs of impaired counselors (Lawson & Venart, 2005). The taskforce identified goals for education for counselors on impairment and how to prevent it, securing treatment for impaired counselors, teaching self-care strategies, and advocating within the organization and at both the state and national levels to address issues associated with impairment. Although the taskforce focused on the broader topic of impairment, compassion fatigue remains a component of this experience. The creation, cultivation, and maintenance of a wellness lifestyle is a primary means of addressing and rectifying counselor impairment and compassion fatigue (Lawson & Venart, 2005).

Wellness is defined as “a way of life oriented toward optimal health and well-being in which body, mind, and spirit are integrated by the individual to live life more fully” (Myers, Sweeney, & Witmer, 2000, p. 252). Wellness and prevention are core components of counselors’ professional identities (Mellin, Hunt, & Nichols, 2011). As a result, researchers have studied the benefits of wellness strategies for counselors (Cummins, Massey, & Jones, 2007), counselor educators (Wester, Trepal, & Myers, 2009), and CITs (Yager & Tovar-Blank, 2007). Additionally, Figley (1995) specifically identified poor self-care as a primary risk factor for experiencing compassion fatigue, and Chi Sigma Iota’s (CSI; n.d.) advocacy themes, specifically Theme 6, outline the need for advocacy related to prevention and wellness for clients and counselors (Lee, 2012). The development of a taskforce, the extensive literature associated with compassion fatigue and wellness, and CSI’s identification of wellness as an area of advocacy indicate a clear relationship between counselor experience and counselor practice. Based on previous research, ACA’s stance on counselor self-care, and humans’ innate desire to engage in complex processes to achieve optimal functioning and well-being, it is beneficial for counselors to consider a new phenomenon related to their consistent exposure to global issues through media and social media. Counselors currently conceptualize compassion fatigue as a linear process occurring as a result of the cumulative direct exposure to clients’ distressing experiences. This article presents an expanded perspective on counselor compassion fatigue occurring as a result of exposure to current events and issues. Furthermore, this article offers a language for this experience as well as a conceptualization of the phenomenon.

GCF

I suggest the term global compassion fatigue to describe the process by which an individual experiences extreme preoccupation and tension as a result of concern for those affected by global events without direct exposure to their traumas through clinical intervention. GCF requires examining compassion fatigue outside of client-specific experiences and within a larger context. This invites counselors and CITs to explore how they are human and existing in a conflicted, polarized, and oftentimes troubling world.

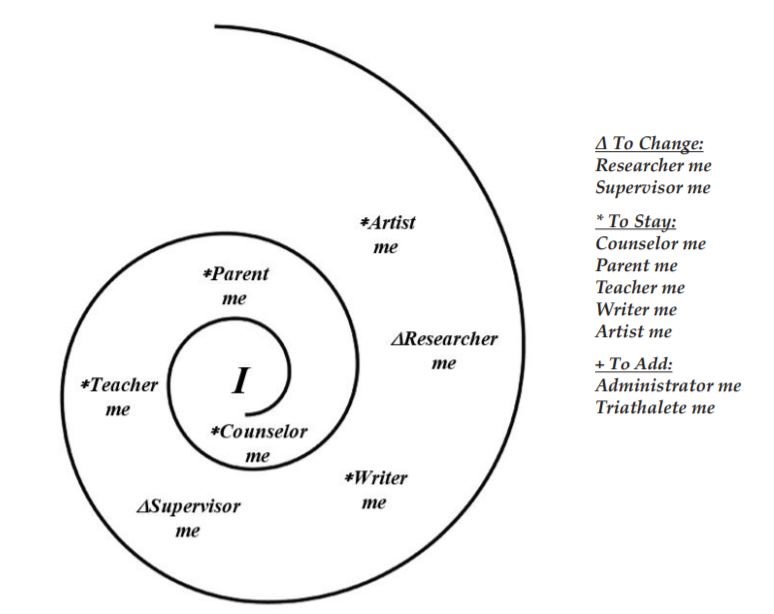

Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of these constructs. After exposure to a traumatic global event, humans experience an acute stress-related psychological response (Holman, Garfin, & Silver, 2013); for counselors this may manifest as GCF because of their foundational helping skills rooted in the ability to feel and exhibit empathy for the issues faced by others (A. J. Clark, 2010). Once this response occurs, counselors can utilize wellness and self-care strategies and engage in social justice advocacy efforts as deterrents to GCF. If they bypass these methods, they might experience the extreme preoccupation and tension that are indicators of GCF. However, counselors can interrupt and manage their GCF by moving to wellness and advocacy strategies.

Figure 1. Process of GCF. After media exposure to a global event and engaging in an emotional response, counselors can immediately experience GCF. Wellness and advocacy are two methods of either addressing GCF after experiencing it or through prevention to deter the experience.

GCF differs from vicarious traumatization in that it does not denote permanent change in cognitive schema; rather, a counselor can experience GCF transiently and in response to significant global and communal events. Counselors experiencing GCF do so outside of clients’ presenting problems. Although no current counseling literature describes this phenomenon, Stebnicki (2007) proposed the concept of empathy fatigue, which “results from a state of emotional, mental, physical, and occupational exhaustion that occurs as the counselors’ own wounds are continually revisited by their clients’ life stories of chronic illness, disability, trauma, grief and loss” (p. 318). Whereas GCF does bear similarity to empathy fatigue, empathy fatigue remains related to an occurrence resulting from direct clinical exposure (Stebnicki, 2007), and GCF involves counselor introspection unrelated to session content. Relatedly, Bayne and Hays (2017) recently conducted a study to conceptualize the conditions of empathy within the counseling process. They developed an exploratory model of counselor empathy that acknowledges the multidimensionality of the empathic process, including the variables associated with counselor impairment. GCF proposes that counselors’ intense emotional experiences related to global concerns are associated with empathy and a desire to help those directly affected. Current events that may cause a counselor to experience GCF include politics, natural disasters, violence (including mass shootings), terrorist attacks, threats to human rights, and animal abuse.

Compassion fatigue research is the best point of reference when considering the experience of GCF. Compassion fatigue manifests through physical, psychological, spiritual, and social symptoms (Lynch & Lobo, 2012), and counselors experiencing GCF also can exhibit these symptoms. However, counselors must consider the source of their feelings of fatigue. For example, Coetzee and Klopper (2010) noted, “compassion fatigue is caused by the prolonged, intense, and continuous care of patients, use of self, and exposure to stress” (p. 239). I suggest that GCF involves a similar experience, although as a result of continuous concern for other beings, a desire to help recover from or solve the issues affecting those beings, and repeated exposure to current events harming individuals on a large scale. Additionally, ACA’s Advocacy Competencies call for professional counselors to engage in systemic and sociopolitical advocacy on a continuum ranging from the microlevel (i.e., the individual) to the macrolevel (i.e., the public; Lewis, Arnold, House, & Toporek, 2003). Therefore, it is a counselor’s duty to remain aware of systemic, environmental, and political factors impacting clients in addition to immersing themselves in advocacy and mechanisms for change. Such actions may leave counselors susceptible to impairment in response to global issues, although moving from awareness to action also can help prevent or mitigate GCF.

Researchers have explored the effects of distressing events on helping professionals. Early research described the relationship between clergy members’ compassion fatigue and their time spent with trauma victims following the September 11th terrorist attacks (Flannelly, Roberts, & Weaver, 2005). Counselors responding after a natural disaster (Lambert & Lawson, 2013) and trauma counselors (Sansbury, Graves, & Scott, 2015) are populations often researched in the compassion fatigue literature. For example, Day, Lawson, and Burge (2017) reported the results of a qualitative research study exploring compassion fatigue and shared trauma in clinicians providing services after the shootings at Virginia Tech in 2007. Day et al. raised an interesting point between a counselor’s direct and indirect exposure to global events as well as the level of impairment resulting from the experience. Given the possibility that unresolved trauma can cause issues in functioning, direct exposure to an event removes the possibility that a counselor is experiencing GCF. This shared trauma may result in similar symptomatology, but these symptoms are attributed to the commonality of the trauma experience (Figley Institute, 2012).

From a different framework, researchers have explored the experiences of non-counselors when exposed indirectly to traumatic global events. Although many Americans were not in New York at the time of the September 11th attacks, nor were they likely to have known someone associated with the attacks, the stress of the event was felt across the country in the form of trauma symptoms (Schuster et al., 2001). Individuals living in Britain also experienced psychological changes as a result of the vicarious media exposure to these terror attacks on America (Linley, Joseph, Cooper, Harris, & Meyer, 2003). Similarly, college students at a separate university described an increase in acute stress symptoms as they learned about the shootings at Virginia Tech on television (Fallahi & Lesik, 2009). This research indicates that individuals can experience emotional duress in response to indirect exposure to global or national issues. Ultimately, it is important to remember that, despite extensive training and experience, counselors are humans navigating a society that can upset them in various ways. GCF awareness furthers counselor insight and promotes opportunities for evaluating self-care, wellness, and efficacy under these conditions. Such awareness requires an understanding of the role media plays in individuals’ experiencing of traumatic global events.

The Impact of Media

Previous researchers evaluated the impact of television viewing on an individual’s stress symptoms and levels of vicarious exposure (Fallahi & Lesik, 2009; Linley et al., 2003), suggesting that the role of technology can significantly affect a counselor’s ability to create boundaries and step away from the tragic circumstances occurring in the world around them. With 62% of adults obtaining their news from social media sites in 2016, an increase from 49% in 2012 (Gottfried & Shearer, 2016), it is clear that regular social media use can result in high levels of exposure to distressing news content. Additionally, four out of five adults in the United States reported constantly “checking” their cellular phones for emails, text messages, and social media (American Psychological Association, 2017). This same survey also described higher stress levels in the “constant checker” population than those using technology less frequently.

Researchers have discovered a link between emotional well-being and use of television media. Schlenger et al. (2002) found a statistically significant relationship between the levels of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and the numbers of hours spent watching television coverage of the September 11th terrorist attacks when assessing the psychological reactions of 2,273 adults residing in major metropolitan cities in the United States one to two months after the attacks. Fallahi and Lesik (2009) also identified a problematic association between indirect exposure to a tragic event through news media sources and symptoms of acute stress disorder.

Therefore, if a counselor or CIT is particularly sensitive to the content to which they are exposed through the media, they increase their risk of experiencing GCF. Conversely, social media also might provide an opportunity for community and connection in the face of global issues. The idea of community is no longer constrained within the bounds of physical associations; rather, the internet provides access to distant communities and relationships (Gruzd, Wellman, & Takhteyev, 2011). Supporters and activists involved in the Black Lives Matter movement are an example of such a community. Black Lives Matter erupted on social media as a Twitter hashtag created to raise awareness for and demonstrate protest against police brutality on members of the Black community (Petersen-Smith, 2015). Through this online movement, individuals were able to exhibit solidarity and take a stand against racism toward Black people with their use of social media (Schuschke & Tynes, 2016). Similarly, the #MeToo internet-based movement brought attention to women’s rights and sexual violence (Hostler & O’Neil, 2018), and social media platforms also provide a method of addressing the stigma of mental health and addiction (de la Cretaz, 2017).

ACA has an active social media presence through online pages and forums on their website, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn (ACA, 2017). The ACA Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014) states that counselors will use social media only when it is in the best interest of the client while protecting their identity and well-being (Section H). This is another example in which a position is based on a situation specifically involving the client and counselor. Although researchers have explored the role of social media in counselor education (Tillman, Dinsmore, Chasek, & Hof, 2013) and recommendations have been made for using social media ethically in clinical practice (Giota & Kleftaras, 2014), researchers have yet to explore how social media affects practicing counselors on an emotional level. Adopting GCF into the counselor impairment literature would suggest a need for ACA to also establish recommendations for counselors’ social media use and how excessive exposure to global events can affect their work as counselors.

A New Perspective

As social beings dependent upon one another for survival, humans have an evolutionary and biological drive to feel connected and invested in others. Specifically, humans are interested in the welfare of others on a neurological level (Lieberman, 2013). Counselors and CITs can feel a need to help others based on evolutionary compulsions rooted in social psychology. However, they also can feel this drive to an amplified extent because of their consistent demonstration and use of empathy, a foundational helping skill that allows counselors to “enter the client’s phenomenal world, to experience the client’s world as it were your own without ever losing the ‘as if’ quality” (Rogers, 1961, p. 284). Although all humans are susceptible to experiencing fatigue as a result of high exposure to global issues through media, not all humans work in a helping profession based in the empathic experience. Therefore, similar to the need for counselors to monitor themselves for impairment as a result of direct engagement with clients’ presenting issues, counselors also need to monitor for impairment from global issues. Regardless of continuous exposure to distressing global events, counselors continue to help others on a consistent basis. This indicates a critical need for counselors to understand their relationship to social media and the global events to which they experience an emotional response.

Symptoms of GCF can manifest similarly to traditional compassion fatigue. These symptoms can include emotional and physical exhaustion associated with care for others, desensitization to stories and experiences, poorer quality of care, feelings of depression or anxiety, increased stress, difficulty concentrating, and preoccupation (Figley Institute, 2012). Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the counselor to understand the source of these symptoms. Unlike counselors’ direct work with clients in which there may be greater opportunities to assist in managing or addressing a pain-inducing problem, emotional and cognitive responses to global issues present a different type of challenge. Managing issues in which a person may perceive little control and direct influence can cause responses such as rumination (Nolen-Hoeksma, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008) and fear (Pain & Smith, 2008). Although counselors can experience these feelings regarding clients (Sansbury et al., 2015), there are greater opportunities for direct interaction with the client needing assistance. In most cases, counselors are unable to directly impact the people involved in the global events to which they are continuously exposed through media and social media. Optimal human functioning involves integration of the mind, body, and spirit (Myers et al., 2000). GCF can impact this integration when counselors are unable to live fully through the exhaustion of exposure to global events. Wellness strategies and forms of advocacy can prevent or rectify these experiences. Myers et al. (2000) acknowledged that “global events, whether of natural (e.g., floods, famines) or human (e.g., wars) origin, have an impact on the life forces and life tasks depicted in [wellness models]” (p. 252). In addition, advocacy in the wake of social events can provide feelings of efficacy and social connection (Scott & Maryman, 2016). This new perspective provides implications for the profession of counseling, including recommendations, cultural considerations, and areas of future research.

Implications for Counselors

In a “plugged-in” society, it is possible to become overwhelmed with the daily stream of news and information. Additionally, counselors can be at higher risk of experiencing impairment because of their empathic nature (Figley, 1995) and ethical duty to engage in social justice for causes that improve equity for individuals and groups (ACA, 2014). As leaders and advocates, GCF may be present in counselors’ daily clinical work. Licensed counselors in private practice may not be receiving ongoing supervision (Bernard & Goodyear; 2014); therefore, no external individual is monitoring how they are managing GCF and its effects. Counselors outside of supervision must exercise great care to practice self-awareness and approach others for assistance. Furthermore, counselors in high-volume settings often work with large caseloads that present with complex issues (Belling et al., 2011; Lombardo, 2018), and it may be easy for them to ignore their own needs while addressing the needs of others. Given the critical period of counselor development, GCF also must be considered within the context of counselor education. GCF during the formative period of graduate-level education in counseling can impede overall skill development. As new counselors find themselves more likely to experience compassion fatigue (Figley, 1995), the same may hold true for GCF. GCF may result in a type of developmental stalling in which counseling students feel an “empathy overload.” Such an overload of empathic emotions may impede the student’s transformation into a counselor. This provides implications for counselor education programs to measure students’ responses to emotionally distressing stimuli (O’Brien & Haaga, 2015) of both clinical and global nature as well as openly and unashamedly discuss signs and symptoms of impairment (Merriman, 2015).

I propose that counselors can manage GCF similarly to compassion fatigue because of the possibility of the two phenomena appearing symptomatically similar. However, GCF requires a greater level of self-awareness, recognition, and acceptance in order to address it. Counselors must learn how to distinguish between the two concepts and understand the possibility for overlap. A number of tools used to manage compassion fatigue can be used for GCF. Supervision, personal counseling, and consultation are all avenues of accountability, monitoring, and fidelity to the profession (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014). Although advocacy can be another tangible method of preventing or mitigating GCF, activism can cause emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion (Chen & Gorski, 2015); therefore, advocacy paired with careful attention to wellness can allow counselors to be most effective in helping to address global issues (Roysircar, 2009). Self-care practices and a wellness lifestyle may also act as protective factors to GCF. Myers et al. (2000) noted, “If one’s spirituality is healthy . . . [it] provides a firm foundation and core for the rest of the components of wellness” (p. 258). This indicates counselors developing an optimistic outlook in response to global events creates greater buffering or management of GCF. Similarly, these authors also state that self-direction allows a person to “move smoothly through time and space”

(p. 258). The cumulative pressure of global stressors necessitates firm self-direction to maintain focus in the chaos of present time and space. Wellness is cumulative and enhances longevity for professional practice (Myers et al., 2000). Ultimately, counselors are ethically responsible for ensuring they practice healthy boundaries and work within their competencies (ACA, 2014). An open dialogue with colleagues, self-awareness of strong responses to global events, pursuing systemic change through advocacy, and cultivating personal wellness encourage management of GCF (Robino & Pignato, 2017).

GCF holds particular relevance for counselors of color. Individuals from historically marginalized populations must understand, identify, and address their experiences and the effects of systemic and individualized racism as well as the psychological trauma of oppression and marginalization (Carter, 2007). The number of publicized events that occur in relation to civil rights issues and social justice concerns warrant additional consideration of GCF in specific populations. For example, police brutality against Black males can cause GCF in many counselors, particularly in counselors of color because of the negative psychological health outcomes for communities of color that stem from racism and discrimination (Carter & Forsyth, 2009; Comas-Díaz, 2016). Furthermore, violence (e.g., the Charleston, South Carolina, shooting targeting a specific religious group consisting of people of color and the Charlottesville, Virginia, protests that resulted in the death of a counter-protester) and localized natural disasters (e.g., fires in Tennessee and the Western United States that affected entire communities and hurricanes like Harvey, Irma, and Maria that caused devastation in the Southern United States and Puerto Rico) also increase the risk of GCF in counselors indirectly or somewhat directly exposed to these events. At the time of this writing, the president of the United States has signed an Immigration Executive Order (Executive Order No. 13,769, 2017) that calls for banning residents of certain Middle Eastern countries from entering the United States. In addition, the public expressed outrage at the removal of children from families seeking asylum at the U.S.–Mexico border (Goldstein, 2018). Such traumatic events become a systemic, multi-level public health issue (Magruder, McLaughlin, & Elmore Borbon, 2017) and increase the possibility of GCF among concerned individuals, including counselors and counseling students.

The emergence of this concept paves the way for a broad range of research avenues. First, I recommend the study of GCF in counselor education programs. With CITs particularly sensitive to the nuances of the counseling profession (Bernard & Goodyear, 2014), the critical period of graduate education requires an examination into how GCF can affect counselor development. Second, the management of GCF calls for greater practice of self-care and exercising of insight. For example, researchers could explore the use of mindfulness and reflexivity in assessing how to treat counselors impacted by global events. Additionally, future research could explore the relationship of counselors’ social media use and GCF experiences. Statistics indicating the increase of social media as a news source (Gottfried & Shearer, 2016) raise questions of how counselors are impacted by their own internet activity. Researchers also could investigate counselor advocacy on social media. Although this article proposes that counselors may experience frustrations that contribute to GCF as a result of social media exposure to distressing global events, Dr. Holcomb-McCoy described social media as a tool for advocacy (Meyers, 2017), which may help in mitigating GCF. Such studies may assist counselors in delineating between GCF and other phenomena of impairment.

Finally, greater research is needed to assess and measure GCF. No accurate measurement yet exists for the phenomenon of GCF. Compassion fatigue measurements assess the negative aspects of helping others through direct contact (Figley, 1996). For GCF, this does not address the negative aspects of compassion for indirect exposure to global events. The Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R; Weiss, 2007) measures the subjective distress associated with a traumatic event. However, the IES-R measures symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Although it captures the experience of an external global event, it does not capture the transient, yet profound, emotional experience of GCF. The answer to assessing GCF may lie in the development of an instrument that combines compassion fatigue assessments and the IES-R to measure GCF symptoms as it relates to global events.

Conclusion

This article introduces the concept of GCF into the counseling literature. By expanding the literature on other explanations of impairment, we broaden opportunities for self-awareness and professional development. Previously researched impairment concepts require an expansion into this new perspective by incorporating the effects of exposure to current events. This new phenomenon also contributes to counselor wellness research and the importance of maintaining a healthy wellness lifestyle as a deterrent to GCF. Adopting this concept and language into the literature on impairment and wellness encourages further consideration of counselor health, counselors’ management of distressing global events, and how this may impact both counselors and clients as humans.

As counselors become competent in their roles as advocates for social justice, their involvement in critical global events necessitates attention to the cumulative toll such a role may entail. In addition, consistent exposure to emotionally debilitating global events through social media places counselors in a peculiar position in which they must balance their need to remain informed of events and their need to remain healthy and well. Counselors carry the extra responsibility of remaining present and empathic with their clients while also protecting the empathy they experience for the world around them. Counselors’ marginalized and impacted cultural identities also factor into their experiences of GCF. In this regard, wellness becomes not simply an ethical duty, but also a professional imperative in the interest of both counselor and client welfare.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Adams, R. E., Boscarino, J. A., & Figley, C. R. (2006). Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: A validation study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 103–108.

doi:10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

American Counseling Association. (2017). Press room. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/about-us/about-aca/press-room

American Psychological Association. (2017). Stress in America: Coping with change. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2017/technology-social-media.pdf

Baird, K., & Kracen, A. C. (2006). Vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress: A research synthesis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 19, 181–188. doi:10.1080/09515070600811899

Bayne, H. B., & Hays, D. G. (2017). Examining conditions for empathy in counseling: An exploratory model. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 56, 32–52. doi:10.1002/johc.12043

Belling, R., Whittock, M., McLaren, S., Burns, T., Catty, J., Jones, I. R., . . . the ECHO Group. (2011). Achieving continuity of care: Facilitators and barriers in community mental health teams. Implementation Science, 6, 23–29. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-23

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (2014). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Carter, R. T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 13–105. doi:10.1177/0011000006292033

Carter, R. T., & Forsyth, J. M. (2009). A guide to the forensic assessment of race-based traumatic stress reactions. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 37, 28–40.

Chen, C. W., & Gorski, P. C. (2015). Burnout in social justice and human rights activists: Symptoms, causes, and implications. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 7, 366–390. doi:10.1093/jhuman/huv011

Chi Sigma Iota. (n.d.). Theme F: Prevention/wellness. Retrieved from http://www.csi-net.org/?Advocacy_Theme_F

Clark, A. J. (2010). Empathy: An integral model in the counseling process. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 348–356. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00032.x

Clark, P. (2009). Resiliency in the practicing marriage and family therapist. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 35, 231–247. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00108.x

Coetzee, S. K., & Klopper, H. C. (2010). Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing and Health Science, 12, 235–243. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00526.x

Comas-Díaz, L. (2016). Racial trauma recovery: A race-informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. In A. N. Alvarez, C. T. H. Liang, & H. A. Neville (Eds.), The cost of racism for people of color: Contextualizing experiences of discrimination (pp. 249–272). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Compton, L., Todd, S., & Schoenberg, C. (2017). Compassion fatigue and satisfaction among Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) providers: A study on risk and mitigating factors. Virginia Counselors Journal, 35, 20–27.

Cummins, P. N., Massey, L., & Jones, A. (2007). Keeping ourselves well: Strategies for promoting and maintaining counselor wellness. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 46, 35–49. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00024.x

Dang, Y., & Sangganjanavanich, V. F. (2015). Promoting counselor professional and personal well-being through advocacy. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 2, 1–13. doi:10.1080/2326716X.2015.1007179

Day, K .W., Lawson, G., & Burge, P. (2017). Clinicians’ experiences of shared trauma after the shootings at Virginia Tech. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95, 269–278. doi:10.1002/jcad.12141

de la Cretaz, B. (2017, April 21). The Voices Project is fighting addiction & stigma through social media. Retrieved from https://www.thefix.com/voices-project-fighting-addiction-stigma-through-social-media

Exec. Order No. 13,769, 3 C.F.R. 8977-8982 (2017).

Fallahi, C. R., & Lesik, S. A. (2009). The effect of vicarious exposure to the recent massacre at Virginia Tech. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1, 220–230. doi:10.1037/a0015052

Figley, C. R. (Ed.). (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel.

Figley, C. R. (1996). Review of the Compassion Fatigue Self-Test. In B. H. Stamm (Ed.), Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation (pp. 127–130). Baltimore, MD: Sidran Press.

Figley Institute. (2012). Basics of compassion fatigue. Retrieved from http://www.figleyinstitute.com/documents/Workbook_AMEDD_SanAntonio_2012July20_RevAugust2013.pdf

Flannelly, K. J., Roberts, S. B., & Weaver, A. J. (2005). Correlates of compassion fatigue and burnout in chaplains and other clergy who responded to the September 11th attacks in New York City. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 59, 213–224. doi:10.1177/154230500505900304

Giota, K. G., & Kleftaras, G. (2014). Social media and counseling: Opportunities, risks, and ethical considerations. International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business, and Industrial Engineering, 8, 2378–2380.

Goldstein, J. M. (2018, May 26). As ICE separates children from parents at the border, public outrage grows. Retrieved from https://thinkprogress.org/as-ice-separates-children-from-parents-at-the-border-public-outrage-grows-c624e69cd43f/

Gottfried, J., & Shearer, E. (2016, May 26). News use across social media platforms 2016. Retrieved from www.jour

nalism.org/2016/05/26/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2016/

Gruzd, A., Wellman, B., & Takhteyev, Y. (2011). Imagining Twitter as an imagined community. American Behavioral Scientist, 55, 1294–1318. doi:10.1177/0002764211409378

Holman, E. A., Garfin, D. R., & Silver, R. C. (2013). Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston Marathon bombings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 93–98.

doi:10.1073/pnas.1316265110

Hostler, M. J., & O’Neil, M. (2018, April 17). Reframing sexual violence: From #MeToo to Time’s Up. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/reframing_sexual_violence_from_metoo_to_times_up

Jenkins, S. R., & Baird, S. (2002). Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma: A validational study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15, 423–432. doi:10.1023/A:1020193526843

Lambert, S. F., & Lawson, G. (2013). Resilience of professional counselors following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91, 261–268. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00094.x

Lawson, G., & Venart, B. (2005). Preventing counselor impairment: Vulnerability, wellness, and resilience. In VISTAS: Compelling perspectives on counseling. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/Resources/Library/VISTAS/

vistas05/Vistas05.art53.pdf

Lawson, G., Venart, E., Hazler, R. J., & Kottler, J. A. (2007). Toward a culture of counselor wellness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 46, 5–19. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00022.x

Lee, C. C. (2012). Social justice as the fifth force in counseling. In C. Y. Chang, C. A. Barrio Minton, A. L. Dixon, J. E. Myers, & T. J. Sweeney (Eds.), Professional counseling excellence through leadership and advocacy (pp. 109–120). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Lewis, J. A., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. L. (2003). ACA advocacy competencies. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/resources/competencies/advocacy_competencies.pdf

Lieberman, M. D. (2013). Social: Why our brains are wired to connect. New York, NY: Crown.

Linley, P. A., Joseph, S., Cooper, R., Harris, S., & Meyer, C. (2003). Positive and negative changes following vicarious exposure to the September 11 terrorist attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 481–485. doi:10.1023/A:1025710528209

Lombardo, C. (2018, February 26). With hundreds of students, school counselors just try to ‘stay afloat’. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2018/02/26/587377711/with-hundreds-of-students-school-counselors-just-try-to-stay-afloat

Lynch, S. H., & Lobo, M. L. (2012). Compassion fatigue in family caregivers: A Wilsonian concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68, 2125–2134. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05985.x

Magruder, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., & Elmore Borbon, D. L. (2017). Trauma is a public health issue. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 81, 1375338. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1375338

Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout: The cost of caring. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205

McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3, 131–149.

doi:10.1007/BF00975140

Meadors, P., Lamson, A., Swanson, M., White, M., & Sira, N. (2010). Secondary traumatization in pediatric healthcare providers: Compassion fatigue, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying, 60(2), 103–128. doi:10.2190/OM.60.2.a

Mellin, E. A., Hunt, B., & Nichols, L. M. (2011). Counselor professional identity: Findings and implications for counseling and interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 140–147. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00071.x

Merriman, J. (2015). Enhancing counselor supervision through compassion fatigue education. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93, 370–378. doi:10.1002/jcad.12035

Meyers, L. (2017, June 12). Illuminate closing: Less talk, more action. Counseling Today, Online Exclusives. Retrieved from https://ct.counseling.org/2017/06/illuminate-closing-less-talk-action/

Myers, J. E., Sweeney, T. J., & Witmer, J. M. (2000). The Wheel of Wellness counseling for wellness: A holistic

model for treatment planning. Journal of Counseling & Development, 78, 251–266.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb01906.x

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

O’Brien, J. L., & Haaga, D. A. F. (2015). Empathic accuracy and compassion fatigue among therapist trainees. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46, 414–420. doi:10.1037/pro0000037

Pain, R., & Smith, S. J. (Eds.). (2008). Fear: Critical geopolitics and everyday life. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Petersen-Smith, K. (2015). Black Lives Matter: A new movement takes shape. International Socialist Review, 96. Retrieved from http://isreview.org/issue/96/black-lives-matter

Ratts, M. J. (2009). Social justice counseling: Toward the development of a “fifth force” among counseling paradigms. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 48(2), 160–172.

doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2009.tb00076.x

Ratts, M. J., D’Andrea, M., & Arredondo, P. (2004). Social justice counseling: “Fifth force” in the field. Counseling Today, 47, 28–30.

Robino, A., & Pignato, L. (2017, February). Global compassion fatigue: An ethical duty for awareness and action. Paper presented at the Virginia Association for Counselor Education and Supervision (VACES) Conference, Norfolk, VA.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Roland, C. B. (2016, November 10). ACA president issues post-election statement of support. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/news/updates/2016/11/10/aca-president-issues-post-election-statement-of-support

Roysircar, G. (2009). The big picture of advocacy: Counselor, heal society and thyself. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87, 288–294. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00109.x

Sansbury, B. S., Graves, K., & Scott, W. (2015). Managing traumatic stress responses among clinicians: Individual and organizational tools for self-care. Trauma, 17(2), 114–122. doi:10.1177/1460408614551978

Schlenger, W. E., Caddell, J. M., Ebert, L., Jordan, B. K., Rourke, K. M., Wilson, D., . . . Kulka, R. A. (2002). Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: Findings from the national study of Americans’ reactions to September 11. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 581–588. doi:10.1001/jama.288.5.581

Schuschke, J., & Tynes, B. M. (2016). Online community empowerment, emotional connection, and armed love in the Black Lives Matter Movement. In S. Y. Tettegah (Ed.), Emotions, technology, and social media (pp. 25–47). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Schuster, M. A., Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Collins, R. L., Marshall, G. N., Elliott, M. N., . . . Berry, S. H. (2001). A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The New England Journal of Medicine, 345, 1507–1512. doi:10.1056/NEJM200111153452024

Scott, J. T., & Maryman, J. (2016). Using social media as a tool to complement advocacy efforts. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 7(1S), 1–22. doi:10.7728/0701201603

Solomon, J. (2007). Metaphors at work: Identity and meaning in professional life. Retrieved from http://thegoodproje

ct.org/pdf/JSolomon-Metaphors-at-Work-Manuscript-Nov-2007.pdf

Sorenson, C., Bolick, B., Wright, K., & Hamilton, R. (2016). Understanding compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A review of current literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 48, 456–465. doi:10.1111/jnu.12229

Stebnicki, M. A. (2007). Empathy fatigue: Healing the mind, body, and spirit of professional counselors. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 10, 317–338. doi:10.1080/15487760701680570

Tillman, D. R., Dinsmore, J. A., Chasek, C. L., & Hof, D. D. (2013). The use of social media in counselor education. In Ideas and Research you can use: VISTAS 2013. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/the-use-of-social-media-in-counselor-education.pdf?sfvrsn=370433a5_10

Weiss, D. S. (2007). The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. Retrieved from http://www.emdrhap.org/co

ntent/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/VIII-E_Impact_of_Events_Scale_Revised.pdf

Wester, K. L., Trepal, H. C., & Myers, J. E. (2009). Wellness of counselor educators: An initial look. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 48, 91–109. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2009.tb00070.x

Yager, G. G., & Tovar-Blank, Z. G. (2007). Wellness and counselor education. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 46(2), 142–153. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00032.x

Yep, R. (2017, December 21). ACA weighs in on wording restrictions at the Centers for Disease Control [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/news/aca-blogs/aca-government-affairs-blog/aca-government-affairs-blog/2017/12/20/aca-weighs-in-on-wording-restrictions-at-the-centers-for-disease-control

Ariann Evans Robino, NCC, is an assistant professor at Nova Southeastern University. Correspondence can be addressed to Ariann Robino, 3301 College Avenue, Maltz Building, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314, arobino@nova.edu.

Nov 28, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 4

Nesime Can, Joshua C. Watson

Scholars have described compassion fatigue as the result of chronic exposure to clients’ suffering and traumatic stories. Counselors can struggle when they experience compassion fatigue because of various reasons. As such, an exploration of factors predictive of compassion fatigue may help counselors and supervisors buffer adverse effects. Utilizing a hierarchical linear regression analysis, we examined the association between wellness, resilience, supervisory working alliance, empathy, and compassion fatigue among 86 counselors-in-training (CITs). The research findings revealed that resilience and wellness were significant predictors of compassion fatigue among CITs, whereas empathy and supervisory working alliance were not. Based on our findings, counselor educators might consider enhancing their current training programs by including discussion topics about wellness and resilience, while supervisors consider practicing wellness and resilience strategies in supervision and developing interventions designed to prevent compassion fatigue.

Keywords: compassion fatigue, counselors-in-training, wellness, resilience, supervisory working alliance

Balancing self-care and client care can be a challenge for many counselors. When counselors neglect self-care, they can become vulnerable to several issues, including increased anxiety, distress, burnout, and compassion fatigue (Ray, Wong, White, & Heaslip, 2013). Counselors might be especially prone to experiencing compassion fatigue because they repeatedly hear traumatic stories and clients’ suffering in sessions (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016). This phenomenon is likely pronounced among counselors-in-training (CITs), as lack of experience, skillset, knowledge, and support can lead to struggles when working with clients (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016). Coupled with the increased anxiety, distress, and disappointment, CITs can experience compassion fatigue early in their career development, which can lead to exhaustion, disengagement, and a decline in therapeutic effectiveness (Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013). At this developmental stage, negative experiences can lead to feelings of doubt and a lack of confidence among CITs and potentially lead to career dissatisfaction. Therefore, it is essential and necessary to better understand the predictive factors of compassion fatigue among CITs to prevent its early onset.

Compassion Fatigue in Counseling

Counselors listening to their clients’ fear, pain, and suffering can feel similar emotions. Figley (1995) defined this experience as compassion fatigue; it also can be defined as the cost of caring (Figley, 2002). Whether working in mental health agencies, schools, or hospital settings, counselors experience compassion fatigue because of exposure to large caseloads, painful stories, and lack of support and resources (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016). Despite this exposure, counselors are expected to place their personal feelings aside and provide the best treatment possible in response to the presenting issues and needs of their clients (Figley, 2002; Ray et al., 2013; Turgoose, Glover, Barker, & Maddox, 2017). Maintaining this sense of detached professionalism has its costs, as a number of counselors find themselves at risk for experiencing physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion, as well as feelings of helplessness, isolation, and confusion—a situation collectively referred to as compassion fatigue (Eastwood & Ecklund, 2008; Thompson, Amatea, & Thompson, 2014).

Merriman (2015b) stated that ongoing compassion fatigue negatively impacts counselors’ health as well as their relationships with others. Additionally, compassion fatigue can lead to a lack of empathy toward clients, decrease in motivation, and performance drop in effectiveness, making even the smallest tasks seem overwhelming (Merriman, 2015b). When this occurs, counselors can project their anger on others, develop trust issues, and experience feelings of loneliness (Harr, 2013). Therefore, the demands of the counseling profession can affect many counselors’ wellness and potentially could hurt the quality of client care provided (Lawson, Venart, Hazler, & Kottler, 2007; Merriman, 2015a). Further, counselors experiencing compassion fatigue might have difficulties making effective clinical decisions and potentially be at risk for harming clients (Eastwood & Ecklund, 2008). Consequently, scholars appear to agree that compassion fatigue is an occupational hazard that mental health care professionals need to address (Figley, 2002; Merriman, 2015a).

Factors Associated With Compassion Fatigue

Many researchers have studied the relationships between compassion fatigue and various constructs, such as empathy, gender, mindfulness, support, and wellness (e.g., Beaumont, Durkin, Martin, & Carson, 2016; Caringi et al., 2016; Ray et al., 2013; Sprang, Clark, & Whitt-Woosley, 2007; Turgoose et al., 2017). Researchers conducted most of these studies among novice and veteran mental health professionals. Scant research among CITs exists. Our research attempts to fill this gap by exploring factors affecting CITs given their unique position as both students and emerging professionals. The following review of the literature supports the inclusion of predictor variables used in this study.

Empathy and Compassion Fatigue

One of the most widely studied concepts across various cultures is empathy, as it has been determined to be one of the major precipitants of compassion fatigue (Figley, 1995). However, findings in the literature regarding the association between compassion fatigue and empathy remain mixed (e.g., MacRitchie & Leibowitz, 2010; O’Brien & Haaga, 2015; Wagaman, Geiger, Shockley, & Segal, 2015). For instance, O’Brien and Haaga (2015) compared trait empathy and empathic accuracy with compassion fatigue after showing a videotaped trauma self-disclosure among therapist trainees (a combined group of advanced and novice graduate students) and non-therapists. The results indicated that there was no significant association between participants’ levels of compassion fatigue and empathy scores. However, MacRitchie and Leibowitz (2010) found a significant relationship between compassion fatigue and empathy after exploring the relation of these variables on trauma workers whose clients were survivors of violent crimes. The mixed results of these previous studies suggest further research is needed to understand better the relationship between empathy and compassion fatigue and how this relationship impacts counseling practice.

Supervisory Working Alliance and Compassion Fatigue

Although reviewed literature addressed studies suggesting supervision and support are related factors to compassion fatigue, research on this relationship is still insufficient. Kapoulitsas and Corcoran (2015) conducted a study and found that a positive supervisory relationship has a significant role in developing resilience and reducing compassion fatigue among counselors. Knight (2010) also found that students uncomfortable talking with their supervisor reported a higher risk for developing compassion fatigue. Additionally, organizational support appears to reduce compassion fatigue, whereas an absence of support increases practitioners’ and interns’ risk of developing compassion fatigue symptoms (Bride, Jones, & MacMaster, 2007). Given the intense need for support and guidance CITs need during their initial work with clients, it is expected that those students who do not actively work with their supervisors can struggle and be more vulnerable for compassion fatigue.

Wellness, Resilience, and Compassion Fatigue

Although counselors are encouraged to practice self-care activities to continue to enhance personal well-being (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Coaston, 2017; H. L. Smith, Robinson, & Young, 2008), not all CITs can balance caring for self and others. When CITs do not receive training in the protective factors for compassion fatigue, they risk becoming more vulnerable to violating the ACA code of ethics (Merriman, 2015a; Merriman, 2015b). Kapoulitsas and Corcoran (2015) and Skovholt and Trotter-Mathison (2016) highlighted the importance of resilience and self-care activities as protective factors for compassion fatigue. Wood et al. (2017) evaluated the effectiveness of a mobile application called Provider Resilience to reduce compassion fatigue scores of mental health professionals. After a month of utilization, the results indicated that the application was effective in reducing compassion fatigue. Additionally, Lawson and Myers (2011) conducted a study with professional counselors to examine counselor wellness about compassion fatigue and found a negative correlation between total wellness scores and compassion fatigue scores. As CITs balance academic, family, and work demands, the probability of decreased wellness and a corresponding increase in compassion fatigue exists.

Compassion Fatigue Among CITs

Most CITs are often unable to master all counselor competencies (Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013), and therefore they might not know how to deal with possible stressors and the emotional burden of their work (Star, 2013). Although they are learning counseling skills to provide the best care possible to clients, CITs may find themselves working with seriously troubled or traumatized clients without obtaining quality supervision and support (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2016). Lack of skills and resources increases the likelihood of CITs developing compassion fatigue (Merriman, 2015b). However, there is a lack of focus in compassion fatigue education on preparing CITs to manage compassion fatigue symptoms (Merriman, 2015a). Although scholars have examined compassion fatigue among counselors, there is still a dearth of studies investigating the level of compassion fatigue among CITs and addressing its protective factors within this population (Beaumont et al., 2016; Blount, Bjornsen, & Moore, 2018; Thompson et al., 2014). Subsequently, further research is needed to understand better potential protective factors that can be enhanced to offset the negative impact of compassion fatigue on CITs and the counseling process. Thus, with this study, we aimed at assessing the relationship between resilience, wellness, supervisory working alliance, empathy, and compassion fatigue among CITs in the United States. To accomplish this goal, we sought to answer the following research questions: (1) What is the prevalence of compassion fatigue among CITs? and (2) Do empathy, supervisory working alliance, resilience, and wellness significantly predict levels of compassion fatigue among CITs?

Method

Participants