Mar 26, 2019 | Volume 9 - Issue 1

J. Richelle Joe, M. Ann Shillingford-Butler, Seungbin Oh

In this phenomenological study, the authors explored the lived experiences of 19 African American mothers raising boys and young men to understand how media exposure to community and state violence connects to the physical and mental health of these mothers. Analysis of semi-structured individual interviews revealed six themes: psychological distress, physical manifestations of stress, parenting behaviors, empathic isolation, coping strategies, and strengths. The analysis of the data revealed that these themes were connected such that community and state violence were forces weighing on these mothers, resulting in emotional responses, changes to parenting approaches, physical responses, and empathic isolation, while the mothers’ coping strategies and strengths served as forces to uplift. The authors present the lived experiences of the participants through a discussion of these themes and their implications for counseling African American mothers within the current social–political context.

Keywords: African American mothers, #BlackLivesMatter, community and state violence, media exposure, mental health

During the 2016 Democratic National Convention, seven African American women took the stage in solidarity to shine a light on community and state violence and the need for criminal justice reform (Drabold, 2016; Sebastian, 2016). These women, collectively referred to as the “Mothers of the Movement,” included Lesley McSpadden, Gwen Carr, and Lucy McBath, the mothers of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and Jordan Davis, respectively—young African American males whose deaths were widely publicized as examples of gun violence (community violence) or police use of force (state violence). Sybrina Fulton also was in attendance. The death of her son, Trayvon Martin, in 2012 sparked a modern conversation about violence against African Americans and led to the creation of the #BlackLivesMatter movement (Black Lives Matter, n.d.). During their address to the convention, the “Mothers of the Movement” shared their grief publicly and spoke on behalf of their children, with Fulton emphatically stating: “This isn’t about being politically correct. This is about saving our children” (Drabold, 2016).

Sixty-one years earlier, Mamie Till had similarly allowed the world to see her grief as she wept over the open casket of her 14-year-old son, Emmett, who had been brutally murdered for being a young Black man in the Deep South (CBS News, 2016). Like the death of Trayvon Martin, Emmett Till’s death galvanized the African American community and motivated activists—including Rosa Parks—to participate in the modern civil rights movement (CBS News, 2016). By sharing the intense pain experienced by a mother’s loss of a child to violence, Mamie Till and the “Mothers of the Movement” allowed others to share in their grief.

As written by Sybrina Fulton (2014, para 9) in a letter to Lesley McSpadden, “If they refuse to hear us, we will make them feel us . . . feeling us means feeling our pain; imagining our plight as parents of slain children.” The pain experienced by these mothers was felt. Mothers of Black children extended sympathy and support to these mothers who had lost their children to community or state violence (Stewart, 2017).

One such letter, penned by university professor Melissa Harris-Perry, illustrates the emotional connection felt among women who saw their own children reflected in the faces of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Tamir Rice. According to Harris-Perry (2014, para 8), many Black mothers “felt your anguish through the screen, felt it penetrate our core and break our hearts as we bore witness to your shock and torment.” Statements such as this indicate that the public and violent losses experienced by African American mothers, both past and present, resonate within the African American community and particularly affect other African American mothers, even those who have not experienced such a loss. How African American mothers are affected by bearing witness to the public deaths of African Americans as a result of community and state violence is not fully known. Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate the experiences of African American mothers who have been exposed to state and community violence while raising their sons to understand how this exposure connects to their physical and mental health.

The experiences communicated by the women mentioned above suggest that parenting for these women is in some way unique and shaped by the social and racial contexts in which they live. Research on parenting in general, and parenting stress specifically, has indicated that experiences and context affect the lives of parents in particular ways. Cumulative exposures to life stressors, such as those associated with limited availability of resources, can exacerbate parenting stress, mental strain, or tension related to the role of being a parent (Berry & Jones, 1995; Raphael, Zhang, Liu, & Giardino, 2010). For example, lack of financial resources aggravates parenting stress by draining parents’ emotional resources to respond empathetically to their children. Under high economic strain, parents are more likely to become preoccupied with managing finances (e.g., an overdue bill or loan default) and emotionally less available for their children, which negatively influences child development (Berk, 2013; Conger & Donnellan, 2007). Additionally, parents’ experiences with other daily stressors (e.g., work-related frustrations and burden) influence parenting behaviors and attitudes, which may create stressful home environments for children (Matjasko & Feldman, 2006).

African American mothers in low-income families have reported high rates of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and their PTSD can predict parental distress (Cross et al., 2018). Such parental stress has been inversely related to positive parenting behaviors (Chang et al., 2004), which can result in negative outcomes for children. Stress among African American mothers exists regardless of family structure. Cain and Combs-Orme (2005) found co-caregiving with a spouse, partner, or other family member did not affect maternal stress or parenting behaviors. This research indicates that parental stress is prevalent among African American mothers whether they are single parents or co-parenting.

A contextual factor that may shed light on the experiences of parenting stress among African American mothers is race-based stress (Carter, 2007). According to Greer (2011), the negative, race-related experiences of African Americans are associated with negative psychological outcomes such as anxiety and depression. African American women in particular experience racism within the workplace, health care system, and educational settings (Greer, 2011). Racist microagressions play a key role in the psychological distress of African American women and significantly contribute to increased levels of stress and anxiety (Szymanski & Owens, 2009). Affective costs of racism among this disenfranchised group include depression, anxiety, and somatization (Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2012). Pieterse et al. (2012) reported trauma-like symptoms similar to PTSD among African Americans after prolonged episodes of racism.

Exposure to community and state violence exists as a particular type of race-based stress that strains the psyche of African Americans. Galovski et al. (2016) found that among community members in Ferguson, Missouri, following the killing of Michael Brown by a law enforcement officer, post-traumatic stress and depression were higher among African Americans than their White counterparts. Additionally, direct exposure to violence was not associated with distress, suggesting that media exposure or secondary exposure provided the sufficient context for mental health concerns to exist. Similarly, Bor, Venkataramani, Williams, and Tsai (2018) reported that African American residents in a state where police killings of unarmed African Americans occurred experience worse mental health following each incident. These effects were not evident for White residents in the same state, nor was there a similar effect for unarmed White residents or armed African American residents killed by police. According to Umberson (2017), exposure to violent death within the community is particularly difficult when the loss is that of a loved one. Such a loss within the African American community “launches a lifelong cascade of psychological, social, behavioral, and biological consequences that undermine other relationships, as well as health, over the life course” (Umberson, 2017, p. 407). The continued losses of young African American men to community and state violence present a collective threat and result in a sense of vulnerability within the African American community, as well as potentially contribute to an increase in health disparities among this population because of race-related stress.

African American mothers experience parenting stress as well as race-based stress, yet the extent to which race-based parenting stress exists for them is unknown. Research on African American mothers has explored their levels of stress and the relationship that parental stress has with their parenting behaviors and children’s outcomes (e.g., Cain & Combs-Orme, 2005; Chang et al., 2004; Cross et al., 2018; Kennedy, Bybee, & Greeson, 2014). However, often the research focus is on “at-risk” African American mothers such as adolescent mothers, single mothers, mothers experiencing intimate partner violence, and mothers in low-income households. Additionally, despite the abundance of research with samples of African American mothers, the exploration of their lived experiences as mothers who may be exposed to race-based stress vis-à-vis state and community violence is absent from the literature. Violence resonates through relationships and can be conceptualized as a reproductive health and social justice issue for African American women (Premkumar, Nseyo, & Jackson, 2017). Hence, this study sought to illuminate the experiences of African American women raising sons, allowing them the platform to speak their lived experiences as mothers in the current social and racial context.

Method

The following research question was examined: What are the lived experiences of African American mothers who have been exposed to community and state violence while raising their sons? The research team chose a qualitative approach, specifically phenomenological methodology. As a constructivist approach, phenomenology acknowledges the existence of multiple realities and allows for an understanding of the lived experiences of participants through their own voices. This methodology is congruent with the profession of counseling (Hays & Wood, 2011), and the researchers felt using phenomenology was particularly important given the focus on African American women who experience multiple layers of marginalization at the intersection of race and gender (Crenshaw, 1989).

Participants

Prior to participant recruitment, the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ university approved the study. The participants were recruited via purposive, criterion sampling to gain a sample of African American mothers with at least one son age 25 or younger at the time of the study. Recruitment materials were shared with African American women using direct electronic mail as well as social media. Participants also referred potential participants to the research team for inclusion in the study (snowball sampling). Research team members contacted all participants via direct electronic mail to provide them with details about the study, review the informed consent document, collect demographic information, and schedule the individual interview. Sample size recommendations for qualitative research such as the present study range from six to 12 participants (Creswell, 2013; Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006; Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2007). Hence, the research team sought to recruit 20 participants to account for the possibility of attrition.

In response to recruitment efforts, 22 individuals expressed interest in the study and were initially contacted by the researchers. Two of those individuals were unable to complete an individual interview, and another individual was eliminated because of poor audio recording quality. Hence, data from 19 participants were analyzed for this study. Further recruitment was deemed unnecessary as the sample size exceeded the recommended size and the data analysis reached saturation with data from these 19 participants.

The participants ranged in age from 31 to 61, with a mean age of 44.8. Their sons ranged in age from 2 to 35, though all had at least one son under age 25. All participants were high school graduates, and most had an advanced degree (52.6%). Additionally, most participants lived in two-parent households (52.6%) at the time of the study, earned an annual household income of more than $100,000 (42.1%), and lived in a suburban setting (57.9%). Participant profiles are provided in Table 1.

Data Collection and Analysis

The researchers conducted semi-structured individual interviews with the 19 participants, each lasting 20 to 60 minutes. All interviews were conducted over the phone, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The interview protocol consisted of the following questions: (a) What have your experiences been like being a mother of an African American boy or young man? (b) There have been several violent incidents reported by the media involving African American young men. How do you feel about these incidents? (c) Was there any particular incident that affected you the most? (d) How would you describe your overall mental and physical health? and (e) What would you say are your strengths as a mother? The interviewers provided follow-up questions and clarifying statements to participants when they were deemed necessary or when participants asked for clarification.

Once the interviews were transcribed, the research team analyzed the data in accordance with methods outlined by Moustakas (1994). First, the team immersed themselves in the data by reviewing each transcript individually. They divided the 19 transcripts between the two of them and read through them to become familiar with the data. For each transcript, they identified relevant statements that reflected the participants’ lived experiences (horizontalization) as African American mothers raising boys and young men within the contexts of structural racism and community and state violence. After going through this process individually, the research team met multiple times to review all transcripts and confer about these textural descriptions. The research team identified relevant codes and then synthesized the textural descriptions into themes by examining them for commonalities to distill the meaning expressed by the participants. Verbatim examples were extracted from the transcripts and used to generate a thematic and visual description of the phenomenon being examined. Once the initial data analysis was completed, the researchers conducted member checking by sending each participant their individual transcript as well as the written results section. Participants were asked to comment on the accuracy of their transcripts as well as the alignment of the results with their lived experiences. None of the participants reported any errors or additions to the transcripts, and none provided any additions or corrections to the themes provided in the results.

Table 1. Participant Demographic Information

| Participant |

Age |

Number of Male Children in Home |

Age(s) of Male Children |

Household Composition |

Education |

| 1 |

31 |

1 |

2 |

Multi-generational |

Bachelor’s Degree |

| 2 |

45 |

3 |

15, 20, 27 |

Two-parent |

Master’s Degree |

| 3 |

50 |

1 |

19 |

Two-parent |

Master’s Degree |

| 4 |

42 |

1 |

15 |

Two-parent |

Doctoral Degree |

| 5 |

48 |

1 |

23 |

Two-parent |

Master’s Degree |

| 6 |

43 |

2 |

2, 16, 19 |

Two-parent |

Master’s Degree |

| 7 |

46 |

1 |

16 |

One-parent |

Doctoral Degree |

| 8 |

61 |

1 |

20 |

One-parent |

Some College |

| 9 |

40 |

2 |

2.5, 5 |

Two-parent |

Bachelor’s Degree |

| 10 |

56 |

0 |

19 |

One-parent |

Master’s Degree |

| 11 |

47 |

1 |

18, 26 |

Two-parent |

Bachelor’s Degree |

| 12 |

43 |

1 |

10 |

Two-parent |

Doctoral Degree |

| 13 |

43 |

1 |

18 |

One-parent |

Bachelor’s Degree |

| 14 |

36 |

2 |

2, 7 |

Two-parent |

Bachelor’s Degree |

| 15 |

41 |

1 |

17, 21, 26 |

One-parent |

Doctoral Degree |

| 16 |

45 |

1 |

16 |

One-parent |

Master’s Degree |

| 17 |

42 |

1 |

12 |

Multi-generational |

Bachelor’s Degree |

| 18 |

35 |

1 |

9 |

One-parent |

Some College |

| 19 |

57 |

1 |

22, 35 |

Two-parent |

Bachelor’s Degree |

Trustworthiness and the Research Team

Qualitative research requires credibility, a key element of trustworthiness, such that the research findings accurately reflect the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Reflexivity, wherein researchers critically examine their procedures with respect to power, privilege, and oppression, is a critical element of maintaining research credibility (Hunting, 2014). To safeguard against researcher bias, the researchers worked collaboratively to establish credibility throughout data collection and analysis. The research team consisted of two African American female faculty members at a large Southeastern university. Both were core faculty in the same counselor education program and have experience working as professional school counselors. To address researcher bias, the researchers engaged in bracketing to address the ways in which their experiences influence their approach to research and expectations of the outcomes of the study. Prior to the data collection, they discussed their experiences as African American women who have experienced systemic racism and are aware of state and community violence affecting the African American community. They identified their personal experiences and acknowledged their biases, attempting to put them aside as they conducted the interviews. Throughout the data collection and analysis, they engaged in personal reflection and maintained analytic memos chronicling their reactions and initial thoughts about the data being collected.

Prior to beginning data analysis, the research team met to confirm the analysis procedures to ensure consistency. They analyzed data individually and as a team and determined codes and themes jointly to reduce bias. They also consulted throughout the data analysis process to address questions or concerns regarding the data. They consulted with an outside researcher experienced in qualitative research to get critical feedback on the data analysis process and the research findings (Marshall & Rossman, 2006). This peer review was used as an external check of the research methodology and theoretical interpretation of the data.

Results

Six themes emerged from the data to illustrate the lived experiences of African American mothers who have been exposed to community and state violence while raising their sons: (a) psychological distress, (b) physical manifestations of stress, (c) parenting behaviors, (d) empathic isolation, (e) coping strategies, and (f) strengths. The analysis of the data revealed that these themes were connected such that community and state violence were forces weighing on these mothers, resulting in emotional responses, changes to parenting approaches, physical responses, and empathic isolation, while the mothers’ coping strategies and strengths served as forces to uplift. Below is a discussion of each theme using exemplars from the data to present the experiences of these mothers in their own words.

Psychological Distress

The participants in this study described the emotions they felt regarding community and state violence, with all of them expressing various levels of fear, anger, heartbrokenness, and exhaustion. Fear or anxiety was most prominent for these mothers, many of whom thought of their own sons when they heard stories about young African American men killed by gun violence at the hands of other citizens or by law enforcement officers. Some felt fear of the unknown, as in Participant 9 who stated, “Like, what will the world do to you?” Many expressed that the fear was persistent, as they seemed to ruminate over such shootings. In Participant 10’s words, “I see the pictures of those young men daily in my mind.” The fear that these mothers described relates directly to their sons in that they have a baseline fear that their son also will become a victim of state violence. Participant 2 described living with “an underpinning of terror,” adding that “my fear is that . . . one of my sons is going to be murdered by a police officer.” In addition to fear, the participants reported feelings of anger and outrage. Participant 5 stated that she considered purchasing a gun, although she did not articulate what she would do with it. For many of the mothers, their anger was closely associated with their experience of motherhood: “Before I had kids, I didn’t realize how angry I already was about the injustice . . . it just (caused) more anger and frustration” (Participant 9).

Feelings of being heartbroken, helpless, and psychologically exhausted emerged clearly from the data. Participants expressed disbelief upon hearing about police shootings of unarmed African American men and a lack of control about what Participant 7 referred to as “a cancer on society.” Participant 1 described the experience of feeling like she had been “hit with a rubber bullet, like, you know there’s no penetration, but it hurts all the same.” A particularly poignant statement from Participant 10 indicated that participants feel helpless and almost hopeless about the possibility that a change is possible: “I don’t even know what our children have to do to convince the world that they are children . . . or even that they are human.” Additionally, the mothers are mentally exhausted by reports of community and state violence against African American young men. Participant 1 described feeling burned out, tired, and “just one tipping point message away from a breakdown.”

Part of this exhaustion seemed to stem from a sense of proximity to the events in the news because of social media and 24-hour news cycles. Participants reported that they felt like the shootings were happening right in front of them, making them more aware of the existence of community and state violence. Some reported feeling numb to the media reports and others stopped watching the news or engaging with social media sites in an attempt to try to disconnect from reports they found overwhelming.

Physical Manifestations of Stress

The mothers in this study described the ways in which the exposure to community and state violence affected them physically. Some reported reactions that sounded like responses to trauma or some anxiety-provoking experience that were manifested in their physical bodies. Participant 1 felt “sick to my stomach . . . heart, you know like adrenaline pumping . . . like a tightness in my chest.” Participant 5 stated that after hearing about a recent police shooting and out of concern for the safety of her son, she “would be physically sick.” Additionally, participants reported a loss of sleep and difficulty relaxing. A response by Participant 14 illustrates the connection that the physical effects have to the psychological effects of community and state violence for these mothers: “I cried as though this was my child that had been killed . . . I was sick to my stomach . . . I had a pit in my stomach . . . and I also . . . became overly concerned about my son.” They were psychologically affected by incidents of state and community violence and those effects manifested physically as well as in their hypervigilance regarding their sons.

Parenting Behaviors

The participants described how their mothering has been shaped by their exposure to community and state violence. They reported being hypervigilant and overprotective in their parenting behaviors in an effort to protect their sons. These parenting behaviors included hovering over their sons, micromanaging their sons’ lives, and attempting to limit their sons’ movements. Participant 5 stated that she wanted to put a camera in her son’s car so that she could have an eye on him when he was driving. Participants described their efforts to keep their sons insulated, such as Participant 13’s statement that “I just try to keep my son as far away from it as I possibly can.” Participant 10 expounded on this behavior in great detail, stating “If I could have, I would have locked him in my house and just kept him there.” The mothers seemed to have a keen awareness that their parenting had become overly protective, and they experienced some ambiguity about it. One mother acknowledged that she parents her son and daughter differently and lamented that she may be limiting his cognitive development. Similarly, Participant 4 expressed concern that being overprotective might affect her son’s social life, yet her concern for his safety outweighed that concern, as evidenced by her statement that, “I don’t want that for him, but at the same time I need him to be alive.”

The participants also stated that they regularly have conversations with their sons about how to behave and present themselves to others. They reported increasing these conversations following incidents of community and state violence in the news. The conversations they have include how to carry themselves in a respectable way in public and how to make wise decisions when outside the home. Specifically, they have talked with their sons about what to do if stopped by the police. The participants described the conversations as ones that go beyond the typical lessons that parents teach their children in that these are conversations shaped by their experiences as African American mothers of African American sons. As Participant 5 stated “we’ve had to say things to them that their White friends don’t have to say.”

Empathic Isolation

In their description of the effects community and state violence have had on their emotions, physical bodies, and parenting, the participants also described an experience that the researchers have called empathic isolation. Participants described receiving little to no empathy from others outside of the home as well as a self-imposed masking of emotions within the home in an effort to protect their sons. The lack of empathy outside of the home seemed to be connected with the perceived White privilege of coworkers and community members. Participant 5 stated of such individuals: “I want you to feel my frustration and my anger”—yet those individuals did not. Participant 3 added that the responses that she heard from others after publicized incidents of community or state violence upset her because they reflected a lack of empathy and understanding. During the trial of George Zimmerman, Participant 10 was hopeful because the jury largely consisted of women. However, she was disappointed by the outcome of the trial and felt that the women on the jury saw Trayvon Martin as a Black male adult rather than a 16-year-old boy. She wondered how and when Black children would be seen as children rather than threats. As a result of this lack of empathy, many of the mothers reported masking their emotions in public spaces. Participant 19 stated, “I have to put on my face in the morning when I go into the workplace that has every ethnicity and just be me, not be that concerned mother.”

Similarly, at home the mothers reported holding their emotions close in an attempt to protect their sons. They expressed concern about their emotions affecting their sons, so they mask their emotions. Participant 18 described having to “put on” for her son, meaning that despite her sadness or concern, she had to “put on that face that everything is okay.” A single mother participant expressed how it is particularly difficult for her to allow herself to fully experience her emotions. She described feeling as though she had no choice but to be strong even in moments in which she feels weak. Both inside and outside of the home, these mothers feel a multitude of emotions, yet they do not feel fully free to express them and receive empathy, either because of the empathic failures of others or because they want to shield their sons and keep pushing forward.

Coping Strategies

Despite the stress they feel as mothers raising African American boys and young men, participants identified multiple ways in which they cope or care for themselves in the face of adversity. Some coping strategies were internal or individual, such as maintaining a positive outlook, engaging in self-care, journaling, and prayer or meditation. Reliance on faith was evident for many participants and for at least one participant was a means to fight oppression and liberate her son (Participant 10). Participants also discussed other ways of coping that had more of an external focus, such as connecting with other African American mothers and looking to their existent social network of family and friends for support. Several participants discussed either current involvement or a desire for future involvement in community activism to address systemic racism. These participants described a type of self-care motivated by a desire to see change and manifested in action to address the systemic racism that affected their lives and the lives of their sons.

Few of the participants (n = 4) reported seeking out and utilizing professional mental health services as a coping strategy. Participants gave multiple reasons for not seeking mental health services, including pragmatic ones, such as not having time or not being able to afford services. Participants also made statements such as “I just deal with it” (Participant 7) and “I feel like I can control it” (Participant 15), which seem to relate to the experience of wearing the mask discussed above with the theme of empathic isolation. Other statements by participants indicated that they have little confidence that counseling would help. Participant 14 stated plainly that there is no use in her seeking counseling if the systems that affect her son are still in existence. Participant 10 focused on what the experience in a counseling session would be like if she were to share her experiences and feelings as an African American mother raising a son. She described the potential exhaustion she would feel as a client, stating, “In terms of talking about the anxiety around racism and concern for my children, I just did not have the energy to seek any kind of help for that.”

Strengths

In response to the question about their strengths as mothers, participants identified several internal strengths that shape their parenting as well as the outward behaviors that characterize their motherhood. Among their internal strengths were responsibility, morality, unconditional love and acceptance, integrity, thinking big, being open and honest in communication, being informed and educated, having the ability to see purpose and strengths in their children, flexibility, resourcefulness, and resilience. Participant 10 gave a particularly powerful characterization of her strengths, stating, “I think . . . as African American women to go ahead and be mothers in the world that we live in, it’s a combination of crazy and brave.” With these internal strengths, the mothers reported being active on behalf of their children by giving them as many opportunities as possible, advocating for them when necessary, teaching them skills, building a social support network, and keeping their children as a priority.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of African American mothers who have been exposed to state and community violence while raising their sons to understand how this exposure connects to their physical and mental health. Six themes emerged from the data: psychological distress, physical manifestations of stress, parenting behaviors, empathic isolation, coping strategies, and strengths. From the perspectives of these participants, state and community violence weigh down on them as African American mothers, negatively impacting their psychological and physical health and altering their parenting behaviors. Additionally, the interplay between their psychological distress and the change in their parenting facilitates an experience of empathic isolation, in which these mothers mask their emotions inside their homes so as not to adversely affect their sons, and mask their emotions outside of the home (e.g., in the workplace) as they interact with others who are either incapable or unwilling to provide empathic responses to their experiences. Further, participants identified clear personal strengths and coping strategies, such as devotion to their children and involvement in community activism, which were used to uplift themselves. Interestingly, the coping strategies for most of these women did not include seeking help from a mental health professional, even when they were aware of the psychological distress associated with exposure to community and state violence.

These results are both enlightening and disheartening. African American mothers live with daily fear for their sons of all ages. This fear exists despite most of the participants reporting that their sons had not been directly involved in or exposed to violence. These mothers constantly relive psychological trauma because of media exposure of incidents of community and state violence involving African American boys and young men. The results support sentiments of Galovski et al. (2016) that African American mothers are not concerned with just a few random incidents of violence, but rather are affected by greater, continuous, and systemic experiences of psychological trauma spanning decades. These continued distressing experiences of direct and indirect violence appear to negatively impact the psychological (e.g., anger, fear, outrage) and physiological (e.g., tightness in the chest) well-being of African American mothers and likely exacerbate existing health disparities for this population. Findings support previous research regarding the experience of ongoing race-related PTSD among African American mothers (Pieterse et al., 2012). Still, despite threats to their mental and physical health, African American mothers continue to press through with the hopes of protecting and empowering their sons using a cloak of resilience and buoyancy. Additionally, African American mothers wear a mask of courage and strength to educate their children about racism, resilience, and resistance without revealing their true emotions. DePouw and Matias (2016) highlighted the concept of critical race parenting, whereby parents of color work to educate, advocate, and protect their children from cultural racism. Based on the findings of this study, African American mothers continue to fight for access to safety and equality for their children, while simultaneously attempting to shield their sons from the psychological and physical health effects that community and state violence have on them as mothers.

Implications for Counselors

The results of this study provide insight into the experiences of African American mothers raising sons in the context of #BlackLivesMatter and can inform the work of mental health professionals regarding this population. Given that many African American mothers live with fear or anxiety regarding the safety of their sons, which affects their mental and physical health and parenting behaviors, practitioners might consider culturally sensitive and responsive methods to attract and retain these mothers as clients. An ideal start would be to seek to understand the social and historical context of the experiences of African Americans and the connection with current events of violence and racism. This exploration should be done not within the confines of counseling, but in preparation for building therapeutic rapport. Participants in this study reported possessing little faith that White counselors would understand or believe their experiences. This finding underscores the need for greater cultural competence among White mental health professionals and an increase in the number of available African American counselors to serve African American women. Additionally, work with African American mothers must be strengths-based, building upon the internal and external strengths and resources that exist within the lives of these women. Specifically, the sense of determination encapsulated in the phrase “crazy and brave,” used by one of the participants to describe herself, highlights the resourcefulness of African American mothers to provide for and protect their families. Counselors are encouraged to recognize and enhance such personal assets by highlighting the positive energy that these mothers bring to the therapeutic setting through their stories. Relational cultural theory (RCT) might be an appropriate framework to use in counseling clients like the women in this study. RCT centers the cultural experiences of clients and considers how systems of oppression and marginalization affect individuals and their relationships (Comstock, et al., 2008). The mutual empathy, mutual empowerment, and authenticity that are foundational in RCT can provide a therapeutic environment in which African American mothers can explore their experiences of disconnection, such as the empathic isolation that they described in this study.

Finally, mental health professionals need to consider the importance of social justice advocacy to address the community and state violence that negatively impacts the African American community at large and African American mothers of sons specifically. This, in fact, is an ethical obligation of professional counselors who advocate on multiple levels “to address potential barriers and obstacles that inhibit access and/or the growth and development of clients” (American Counseling Association, 2014, p. 5). The results of this study clearly indicate that community and state violence can be a barrier to optimal physical and mental health of African American mothers. The #BlackLivesMatter movement has created resources for individuals seeking to engage in advocacy and encourage open dialogue around issues of community and state violence (https://blacklivesmatter.com/resources). Specifically, mental health professionals can access and utilize the #BlackLivesMatter toolkits focused on healing justice and action, as well as the toolkit titled #TalkAboutTrayvon. Such resources can be a starting place to gain knowledge and develop a strategy for advocacy.

Limitations and Future Research

This study, although rich in details of the experiences of African American mothers, is not without limitations. Although attempts were made to secure African American mothers from varying sub-groups, the resulting sample yielded mainly educated women from mostly two-parent middle-class families, most of whom were from the Southern region of the United States. A more economically and educationally diverse sample of African American mothers might have yielded differences in experiences. For instance, given that poor communities of color are often over-policed (Alexander, 2010), African American mothers in lower socioeconomic brackets might have discussed direct contact with law enforcement and increased incidents of both community and state violence. Additionally, although many of the participants were married or partnered, the researchers did not explore how their spouses or partners played a role in their experience as African American mothers. Some participants mentioned the fathers of their sons and their perspectives; however, this relational aspect needs further inquiry to fully understand its essence. It was beyond the scope of this study to examine the experiences of African American fathers raising sons in the context of #BlackLivesMatter, yet this is certainly a worthy line of research that would augment the findings of this study.

Despite the lack of heterogeneity in this sample with regards to education and income, and focus on mothers to the exclusion of their spouses, partners, or co-parents, the design of the study provided rich and in-depth data regarding a relatively unexplored yet salient topic among a unique sample. Future research can extend the knowledge base regarding African American mothers by exploring the experiences of mothers who are raising daughters in the current context in which exposure to community and state violence occurs regularly through social media. Often, conversations regarding community and state violence, particularly when police use of excessive force is involved, focus on the experiences of African American boys and men. However, Crenshaw’s (1991) work on intersectionality as well as the #SayHerName movement (2015) reminds us that African American girls and women also are victims of community and state violence. Including mothers raising daughters into this line of research will help uncover the ways in which gender influences motherhood among African Americans when #BlackLivesMatter and #SayHerName intersect. Additionally, future research should include both homogenous and heterogenous focus groups of mothers to explore, compare, and contrast the experiences of mothers of color and White mothers in terms of parental stress, mental health, and physical health. Finally, future research should focus on identifying social determinants of health that counselors, physicians, and other helpers can use to address health disparities that may be exacerbated by ongoing psychological trauma.

Conclusion

The results of this qualitative study highlight the experiences of African American mothers—“crazy and brave” women—determined to protect and provide for their sons while also contending with a lingering fear for their safety within the current social context. State and community violence, now widely broadcasted in media, affect the psychological and physical well-being of these mothers and contribute to hypervigilance in their parenting. As mental health professionals that value the enhancement of human development and the promotion of social justice, counselors have a duty to provide culturally sensitive services to support this population so that they can take off their masks and experience the empathy that is lacking in many aspects of their lives. Additionally, this duty extends beyond the counseling room as counselors serve as social justice advocates in order to address the systemic barriers to mental health and wellness for members of the African American community.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The

New Press.

American Counseling Association. (2014). 2014 ACA code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/

Resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Berk, L. E. (2013). Child development (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Berry, J. O. & Jones, W. H. (1995). The Parental Stress Scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 463–472. doi:10.1177/0265407595123009

Black Lives Matter. (n.d.). Herstory. Retrieved from https://blacklivesmatter.com/about/herstory

Bor, J., Venkataramani, A. S., Williams, D. R., & Tsai, A. C. (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet, 392, 302–310. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9

Cain, D. S., & Combs-Orme, T. (2005). Family structure effects on parenting stress and practices in the African American family. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 32(2), 19–40.

Carter, R. T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 13–105. doi:10.1177/0011000006292033

CBS News. (2016). How Emmett Till’s brutal death “ignited a movement” in America. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/emmett-till-murder-mamie-mobley-america-civil-rights-movement-smithsonian-museum

Chang, Y., Fine, M. A., Ispa, J., Thornburg, K. R., Sharp, E., & Wolfenstein, M. (2004). Understanding parenting stress among young, low-income, African-American, first-time mothers. Early Education and Development, 15, 265–282. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1503_2

Comstock, D. L., Hammer, T. R., Strentzsch, J., Cannon, K., Parsons, J., & Salazar, G., II (2008). Relational-cultural theory: A framework for bridging relational, multicultural, and social justice competencies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86, 279–287. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00510.x

Conger, R. D. & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175–199. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, 139–167.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cross, D., Vance, L. A., Kim, Y. J., Ruchard, A. L., Fox, N., Jovanovic, T., & Bradley, B. (2018). Trauma exposure, PTSD, and parenting in a community sample of low-income, predominantly African American mothers and children. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10, 327–335.

doi:10.1037/tra0000264

DePouw, C., & Matias, C. (2016). Critical race parenting: Understanding scholarship/activism in parenting our children. Educational Studies, 52, 237–259.

Drabold, W. (2016). Meet the mothers of the movement speaking at the Democratic Convention. Retrieved from

http://time.com/4423920/dnc-mothers-movement-speakers

Fulton, S. (2014). Trayvon Martin’s mom: “If they refuse to hear us, we will make them feel us.” Retrieved from http://time.com/3136685/travyon-sybrina-fulton-ferguson

Galovski, T. E., Peterson, Z. D., Beagley, M. C., Strasshofer, D. R., Held, P., & Fletcher, T. D. (2016). Exposure to violence during Ferguson protests: Mental health effects for law enforcement and community members. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29, 283–292. doi:10.1002/jts.22105

Greer, T. M. (2011). Coping strategies as moderators of the relation between individual race-related stress and mental health symptoms for African American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 215—226. doi:10.1177/0361684311399388

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18, 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

Harris-Perry, M. (2014). A letter of sympathy to Michael Brown’s mother. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.com/melissa-harris-perry/letter-sympathy-michael-browns-mother

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counseling research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 288–295. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00091.x

Hunting, G. (2014). Intersectionality-informed qualitative research: A primer. Vancouver, British Columbia: The Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy.

Kennedy, A. C., Bybee, D., & Greeson, M. R. (2014). Examining cumulative victimization, community violence exposure, and stigma as contributors to PTSD symptoms among high-risk young women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 284–294. doi:10.1037/ort0000001

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2006). Designing qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Matjasko, J. L., & Feldman, A. F. (2006). Bringing work home: The emotional experiences of mothers and fathers. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 47–55. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.47

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). A call for qualitative power analyses. Quality & Quantity, 41, 105–121. doi:10.1007/s11135-005-1098-1

Pieterse, A. L., Todd, N. R., Neville, H. A., & Carter, R. T. (2012). Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59, 1–9.

doi:10.1037/a0026208

Premkumar, A., Nseyo, O., & Jackson, A. V. (2017). Connecting police violence with reproductive health. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 129, 153–156. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001731

Raphael, J. L., Zhang, Y., Liu, H., & Giardino, A. P. (2010). Parenting stress in US families: Implications for paediatric healthcare utilization. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36, 216–224.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01052.x

#SayHerName Movement. (2015). #SayHerName: Resisting police brutality against Black women. Retrieved from http://aapf.org/sayhernamereport

Sebastian, M. (2016). Who are the “Mothers of the Movement” speaking at the Democratic National Convention? Retrieved from https://www.elle.com/culture/career-politics/news/a38111/who-are-mothers-of-the-movement-dnc

Stewart, F. R. (2017). The rhetoric of shared grief: An analysis of letters to the family of Michael Brown. Journal of Black Studies, 48, 355–372. doi:10.1177/0021934717696790

Szymanski, D. M., & Owens, G. P. (2009). Group-level coping as a moderator between heterosexism and sexism and psychological distress in sexual minority women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 197–205. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01489.x

Umberson, D. (2017). Black deaths matter: Race, relationship loss, and effects on survivors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 58, 405–420. doi:10.1177/0022146517739317

Richelle Joe, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of Central Florida. M. Ann Shillingford-Butler, NCC, is an associate professor at the University of Central Florida. Seungbin Oh is an assistant professor at Merrimack College. Correspondence can be addressed to Richelle Joe, P.O. Box 161250, Orlando, FL 32816-1250, jacqueline.joe@ucf.edu.

Mar 4, 2019 | Book Reviews

by Jeffrey Magnavita

Formerly merely a tool to enhance office and client management, technology in mental health practice has expanded to offer a breadth of clinical tools. In Using Technology in Mental Health Practice, Jeffrey Magnavita and contributors argue that technology has revolutionized communication, information gathering, and management of professional practice and development. They explore the role of technology as a catalyst for the advancement of clinical research, allowing clinicians to harness information and innovation, improve outcomes, and expand access to mental health treatment. In this text, Magnavita and contributors enumerate the applications of technology in mental health practice across three major domains: Enhancing Access to Care, Technology-Based Treatment, and Professional Development.

The authors assert that technology can enhance access to care by providing information on the current client-centered technology landscape, which contrasts with the former siloed technological landscape. Emerging technology has created a “quantified health” era, shifting this formula to improve access, efficiency, and quality of care by putting the client in the center of their care. This change imbues clients with a sense of empowerment over the clinical decision-making process while fostering a deeper sense of engagement in their own care, facilitating patient compliance. The implementation of technology in the field of mental health has created a shift in which clients are more readily able to contact their clinicians via secure communication apps and clinicians are able to conduct clinical practice more effectively as a result of access to the most up-to-date information instantaneously.

Beyond enhancing access and compliance to mental health care, technology can also contribute to the number and quality of treatments available, as elaborated by Magnavita and his collaborators. They provide an overview of emerging technology-based treatments, which include virtual reality psychotherapy, cranial electrotherapy stimulation, and neurofeedback. They also discuss how clinicians looking to expand their practice can implement these technologies into everyday practice to increase the depth of treatment options. Clinicians can implement these technologies to use real time client feedback to monitor client’s progress, supplement clinical support tools, and expedite and ease practical difficulties.

Furthermore, outside of direct patient benefit, the authors of this text consider how technology may be used to further professional development. For instance, technology has put the collective knowledge of the world at our fingertips via the internet, making research and information infinitely more accessible; this allows for professionals and clinicians alike to channel this information to better their psychotherapy practice and self-development. Such access can also ensure that practitioners are able to keep pace with emerging advances in the field.

As a whole, the authors of this text are committed to using technology ethically and legally to advance the field of mental health. They offer insight into how technology can help expand access to care, how clinicians can utilize technology-based treatments, and how technology can assist in continuing professional development. This text delves into illuminating how mental health professionals can use technology to better meet clinical needs and basic steps for incorporating technology-assisted deliberate practice into mental health practice.

The contributors also explore the potential ramifications of such technology in clinical practice, ultimately advocating for its judicious use. This text can serve as a reference for clinicians who are looking for ethical ways to implement technology to advance their practice, or those who already utilize technology in their personal and professional lives to develop their professional careers. It is also a great reference text for clinicians who are looking to start or expand a business. However, Magnavita warns that, given the ever-changing nature of technology, the information provided regarding technological advances in mental health may soon be outdated.

Magnavita, J. J. (Ed.) (2018). Using technology in mental health practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Reviewed by: Nina Davachi, NCC

The Professional Counselor

tpcjournal.nbcc.org

Nov 29, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Joshua D. Smith, Neal D. Gray

This interview is the third in the Lifetime Achievement in Counseling Series at TPC that presents an annual interview with a seminal figure who has attained outstanding achievement in counseling over a career. Many people are deserving of this recognition, but I am happy that Josh Smith and Dr. Neal Gray have interviewed a visionary in the counseling profession. I first became aware of Dr. Capuzzi over 30 years ago when I was reading his vast research and scholarship as I prepared to teach my first classes as a counselor educator. Over the years, I have been amazed at Dr. Capuzzi’s contribution to the profession and his impact on countless educators, clinicians, and supervisors. I appreciate Josh Smith and Neal Gray for accepting my editorial assignment to interview Dr. Capuzzi. What follows are thought-provoking reflections from a counseling icon and leader.

—J. Scott Hinkle, Editor

David Capuzzi, PhD, NCC, LPC, is past President of the American Counseling Association (ACA), and past Chair of both the ACA Foundation and the ACA Insurance Trust. Currently, Dr. Capuzzi is a member of the senior core faculty in community mental health counseling at Walden University and professor emeritus at Portland State University. Previously, he served as an affiliate professor in the Department of Counselor Education, Counseling Psychology, and Rehabilitation Services at Pennsylvania State University, and as Scholar in Residence in counselor education at Johns Hopkins University.

David Capuzzi, PhD, NCC, LPC, is past President of the American Counseling Association (ACA), and past Chair of both the ACA Foundation and the ACA Insurance Trust. Currently, Dr. Capuzzi is a member of the senior core faculty in community mental health counseling at Walden University and professor emeritus at Portland State University. Previously, he served as an affiliate professor in the Department of Counselor Education, Counseling Psychology, and Rehabilitation Services at Pennsylvania State University, and as Scholar in Residence in counselor education at Johns Hopkins University.

From 1980 to 1984, Dr. Capuzzi was editor of The School Counselor. He has authored several textbook chapters and monographs on the topic of preventing adolescent suicide and is coeditor and author with Dr. Larry Golden of Helping Families Help Children: Family Interventions with School-Related Problems (1986) and Preventing Adolescent Suicide (1988). He coauthored and edited with Douglas R. Gross numerous editions of Introduction to Group Work (2010); Counseling and Psychotherapy: Theories and Interventions (2011); Introduction to the Counseling Profession (2013); and Youth at Risk: A Prevention Resource for Counselors, Teachers, and Parents (2019).

In addition to several editions of Foundations of Addictions Counseling with Dr. Mark Stauffer, he and Dr. Stauffer have published Foundations of Couples, Marriage and Family Counseling (2015); Human Growth and Development Across the Life Span: Applications for Counselors (2016); and Counseling and Psychotherapy: Theories and Interventions (2016). Other texts include Approaches to Group Work: A Handbook for Practitioners (2003), Suicide Across the Life Span (2006), and Sexuality Counseling (2002), the last coauthored and edited with Larry Burlew. Additionally, Dr. Capuzzi has authored or coauthored articles in a number of ACA division journals.

A frequent speaker at professional conferences and institutes, Dr. Capuzzi has consulted with a variety of school districts and community agencies interested in initiating prevention and intervention strategies for adolescents at risk for suicide. He has facilitated the development of suicide prevention, crisis management, and postvention programs in communities throughout the United States; provided training on the topics of at-risk youth, grief, and loss; and served as an invited adjunct faculty member at other universities as time permits.

An ACA Fellow, Dr. Capuzzi is the first recipient of ACA’s Kitty Cole Human Rights Award and also is a recipient of the Leona Tyler Award in Oregon. In 2010, he received ACA’s Gilbert and Kathleen Wrenn Award for a Humanitarian and Caring Person. In 2011, he was named to the Distinguished Alumni of the College of Education at Florida State University and, in 2016, he received the Locke/Paisley Mentorship Award from the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision. In 2018 he received the Mary Smith Arnold Anti-Oppression Award from the Counselors for Social Justice, a division of ACA, as well as the U.S. President’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

In this interview, Dr. Capuzzi responded to six questions about his career, his impact on the counseling profession, and his thoughts about the current state and future of the counseling profession.

- Counseling has made substantial progress during the time you have been a member of the profession. In your opinion, what are the three major accomplishments of the profession?

I joined ACA in 1965, when it was known as the American Personnel and Guidance Association, and there was no such thing as counselor licensure. Although there were many excellent master’s and doctoral programs, there also were many that did not require much coursework to practice as a counselor. There were some university programs that only required 15 or so semester credits as part of a master’s degree in education to be able to seek employment as a counselor. Master’s degrees in counseling were one-year programs requiring 36 to 39 semester credits. There was little standardization of coursework requirements until licensure requirements were gradually adopted state by state. Today, all 50 states have counselor licensure, which has been instrumental in the progression of the counseling profession, and I see this as a major accomplishment.

The development of the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) has provided the profession with assurances that graduates of CACREP-accredited programs meet standards that elevate best practices when working with clients. CACREP accreditation has assisted universities by providing them with support for curriculum revision and improvement and impacted the requirements of the state professional counselor licensing boards.

There was little interest or emphasis on the importance of the inclusion of diverse populations, personalities, lifestyles, and cultures through most of the 1980s, even though the United States has always been a melting pot for immigrants from around the world. The affirmation of differences and the richness that diverse points of view add to our country’s tapestry has been slow to develop, and ACA has made major contributions in this area.

- Which of these major accomplishments was the most difficult to achieve for the counseling profession and why?

The acceptance of diverse populations, personalities, lifestyles, and cultures was the most difficult to achieve. Quite often, over the years, members of diverse populations have not been at the forefront of the profession, not because of lack of astuteness or competence, but because they have not been able to assume elected leadership positions. I am thankful that this is changing and affirm that this development is an asset-based characteristic of the counseling profession. I am so thankful that individuals such as Thelma T. Daley, Beverly O’Bryant, Courtland Lee, Marie Wakefield, Patricia Arredondo, Thelma Duffey, Cirecie West-Olatunji, and Marcheta Evans (and others I am probably forgetting to mention) have been willing to run for and serve in the ACA presidency position because their contributions have been stellar and essential to the maturation of the profession of counseling.

- What do you consider to be your major contribution to the development of the counseling profession and why?

I am relatively certain that I was the first ACA President to establish a diversity theme for the year that I was ACA President. My theme for 1986–1987 was Human Rights and Responsibilities: Developing Human Potential, even though colleagues and friends advised me against naming it in this manner as part of my platform for fear I would lose the election. I decided I should identify a diversity agenda as part of my pre-election platform statement because I wanted members to understand what I stood for in advance of the voting process. During my ACA presidency, I contacted all the editors of our counseling journals and requested that they consider developing special editions focused on some aspect of diversity. I think there were 16 special issues of division journals during my year as immediate past president that were diversity focused. Additionally, the opening session of the annual conference focused on diversity and human rights vignettes (presented by actors) to set the tone for the conference.

Few people know that my early years living in a mining town in Western Pennsylvania provided the backdrop for my interest in diversity and its importance. Many immigrants from other countries settled in Western Pennsylvania, and I spent the first 10 years of my life hearing three or four languages being spoken daily (newcomers could get jobs in the mines and mills, prior to learning much English, and therefore support their families). When my family left the region and moved south, I was surprised to learn that the America I experienced early in life was not typical of the rest of our country. I also was shocked when some of my classmates told me their parents wanted them to check to make sure I was not Jewish (if I was, they could not be my friends), and I was questioned about why I looked so different. When I asked what that meant I was told that most people they knew were tall, blond, and tanned. This early set of life experiences made an indelible impression, precipitated my ACA theme for 1986–87, and has stayed with me to this day.

- What three challenges to the counseling profession as it exists today concern you most, and what needs to change for these three concerns to be successfully resolved?

First, there is a lack of grassroots input to the ACA President and membership of the ACA Governing Council. During recent years, the membership in the state branches and divisions of ACA has declined and there has not been the amount of input and suggestions for agenda items at meetings of the Governing Council as in the past. For a variety of reasons and from time to time, ACA staff and leaders have not always been able to garner needed input and suggestions. Every effort needs to be made to reach out to grassroots members and identify and affirm their concerns based on the philosophy that the role of an elected leader or ACA staff member is to serve the wishes of those who are depending on their leadership.

Second, there is a lack of membership growth in ACA. In 1986, there were 55,000 members of ACA and our battle cry was “60,000—yes we can.” Currently, the association still has about the same number of members. I think grassroots members need to be re-engaged and encouraged to participate in local projects as well as ACA leadership and governance so that interest and involvement, and subsequently membership, can be reinvigorated.

Lastly, the composition of the Governing Council needs changing. Currently, there are more members of ACA who do not belong to ACA divisions than members who do belong to divisions. Yet, the composition of the Governing Council is still based on a model developed several decades ago when divisional membership was very strong and those seated “around the table,” so to speak, were primarily divisional representatives. Now that the composition of the membership has changed, I think there should be a large proportion of seated representatives for the membership at large. Granted, divisions would still need to be represented and seated, but possibly several divisions could be represented by a single member of the Governing Council if collaboration could occur.

- Assuming some challenges will get resolved and others will not, what do you think the counseling profession will look like 20 years from now?

I believe a revised governance structure of ACA, including membership on the Governing Council, will emerge. Perhaps the structure comprised of state branches, regions, and divisions will no longer exist as we now know it, and another way of organizing to insure input and renewed interest in grassroots participation will replace it to increase ACA membership numbers. The continued development of licensure portability and reciprocity across states could enhance the unification of the profession and encourage more interdisciplinary collaboration.

Accreditation and CACREP standards will continue, but hopefully with more tolerance and affirmation options for adult learners seeking specialization options. Currently, there is not much leeway in decision making regarding coursework. Also related, the increased acceptance of online counselor education programs will occur, as well as more clearly articulated requirements and expectations for online counseling.

Lastly, there is increased interest in the importance of advocacy and social justice on the part of ACA and its members. Universal acceptance and affirmation of the importance of diverse populations, personalities, lifestyles, and cultures as they contribute, not only to the profession, but also to the fabric and strength of democracy in the United States, will continue to be at the forefront of what we do.

- If you were advising current counseling leaders, what advice would you give them about moving the counseling profession forward?

First, never forget that your role is to listen to those who elected or appointed you, because your role is to serve members of the counseling profession and advocate for their best interests. Second, even though those elected to represent divisions on the Governing Council have the responsibility to articulate and explain the wishes of their division, in the end, the outcome of decisions made by the Governing Council must reflect what is best for ACA and the counseling profession. Third, although it is always appropriate for those serving in elected positions within ACA to put forward their ideas for changes, initiatives, or innovations, it is never reasonable to expect such agendas to be adopted unless they truly reflect the interests and wishes of those being served through the leadership position.

This concludes the third interview for the annual Lifetime Achievement in Counseling Series. TPC is grateful to Joshua Smith, NCC, and Dr. Neal Gray for providing this interview. Joshua Smith is a doctoral student in counselor education and supervision at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Neal D. Gray is a professor and Chair of the School of Counseling at Lenoir-Rhyne University. Correspondence can be emailed to Joshua Smith at jsmit643@uncc.edu.

Nov 29, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Michael T. Kalkbrenner, Edward S. Neukrug

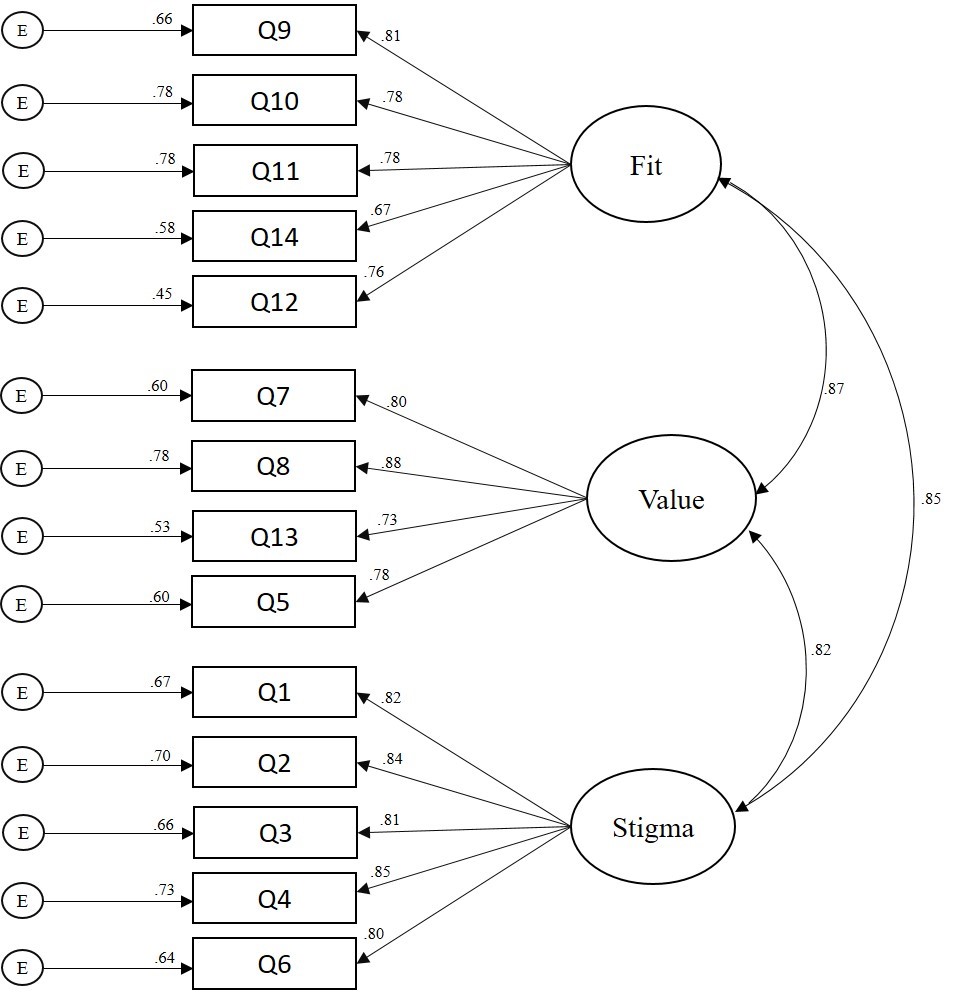

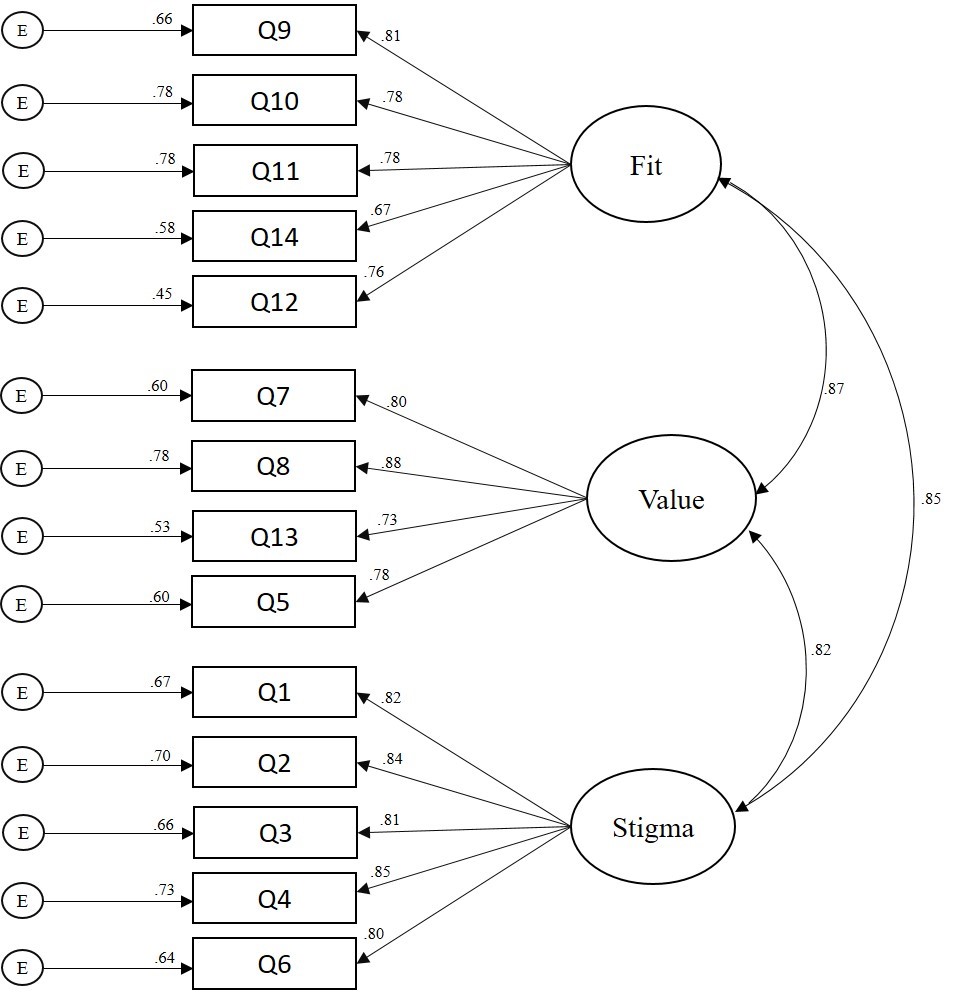

The primary aim of this study was to cross-validate the Revised Fit, Stigma, & Value (FSV) Scale, a questionnaire for measuring barriers to counseling, using a stratified random sample of adults in the United States. Researchers also investigated the percentage of adults living in the United States that had previously attended counseling and examined demographic differences in participants’ sensitivity to barriers to counseling. The results of a confirmatory factor analysis supported the factorial validity of the three-dimensional FSV model. Results also revealed that close to one-third of adults in the United States have attended counseling, with women attending counseling at higher rates (35%) than men (28%). Implications for practice, including how professional counselors, counseling agencies, and counseling professional organizations can use the FSV Scale to appraise and reduce barriers to counseling among prospective clients are discussed.

Keywords: barriers to counseling, FSV Scale, confirmatory factor analysis, attendance in counseling, factorial validity

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health disorders are widespread, with over 300 million people struggling with depressive disorders, 260 million living with anxiety disorders, and hundreds of millions having any of a number of other mental health disorders (WHO, 2017, 2018). The symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders can be dire and include hopelessness, sadness, sleep disturbances, motivational impairment, relationship difficulties, and suicide in the most severe cases (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Worldwide, one in four individuals will be impacted by a mental health disorder in their lifetime, which leads to over a trillion dollars in lost job productivity each year (WHO, 2018). In the United States, approximately one in five adults has a diagnosable mental illness each year, and about 20% of children and teens will develop a mental disorder that is disabling (Centers for Disease Control, 2018).

Substantial increases in mental health distress among the U.S. and global populations have impacted the clinical practice of counseling practitioners who work in a wide range of settings, including schools, social service agencies, and colleges (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017; Twenge, Joiner, Rogers, & Martin, 2017). Identifying the percentage of adults in the United States who attend counseling, as well as the reasons why many do not, can help counselors develop strategies that can make counseling more inviting and, ultimately, relieve struggles that people face. Although perceived stigma and not having health insurance have been associated with reticence to seek counseling (Han, Hedden, Lipari, Copello, & Kroutil, 2014; Norcross, 2010; University of Phoenix, 2013), the literature on barriers to counseling among people in the United States is sparse. Appraising barriers to counseling using a psychometrically sound instrument is the first step toward counteracting such barriers and making counseling more inviting for prospective clients. Evaluating barriers to counseling, with special attention to cultural differences, has the potential to help understand differences in attendance to counseling and can help develop mechanisms that promote counseling for all individuals. This is particularly important as research has shown that there are differences in help-seeking behavior as a function of gender identity and ethnicity (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, Narrow, Grant, & Hasin, 2008).

Attendance in Counseling by Gender and Ethnicity

Previous investigations on attendance in counseling indicated that 15–38% of adults in the United States had sought counseling at some point in their lives (Han et al., 2014; University of Phoenix, 2013), with discrepancies in counselor-seeking behavior found as a function of gender and ethnicity (Han et al., 2014; Lindinger-Sternart, 2015). For instance, women are more likely to seek counseling compared to men (Abrams, 2014; J. Kim, 2017). In addition, individuals who identify as White tend to seek personal counseling at higher rates compared to those who identify with other ethnic backgrounds (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Seidler, Rice, River, Oliffe, & Dhillon, 2017). Parent, Hammer, Bradstreet, Schwartz, and Jobe (2018) examined the intersection of gender, race, ethnicity, and poverty with help-seeking behavior and found the income-to-poverty ratio to be positively related to help-seeking for White males and negatively associated for African American males. In other words, as White males gained in income, they were more likely to seek counseling, whereas the opposite was true for males who identified as African American (Parent et al., 2018).

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment and Attendance in Counseling

Despite the fact that large numbers of individuals in the United States and worldwide will develop a mental disorder in their lifetime, two-thirds of them will avoid or do not have access to mental health treatment (WHO, 2018). In wealthier countries, there is one mental health worker per 2,000 people (WHO, 2015); however, in poorer countries, this drops to 1 in 100,000, and such disparities need to be addressed (Hinkle, 2014; WHO, 2015). Although the lack of attendance in counseling and related services in poorer countries is explained by lack of services, in the United States and other wealthy countries, the availability of mental health services is relatively high, and the lack of attendance is usually explained by other reasons (Neukrug, Kalkbrenner, & Griffith, 2017; WHO, 2015). Research on the lack of attendance in counseling by the general public shows adults in the United States might be reticent to seek counseling because of perceived stigma, financial burden, lack of health insurance, uncertainty about how to find a counselor, and suspicion that counseling will not be helpful (Han et al., 2014; Norcross, 2010; University of Phoenix, 2013).

Appraising Barriers to Counseling