Sep 4, 2014 | Author Videos, Volume 1 - Issue 2

Robert C. Reardon, Sara C. Bertoch

Educational counseling has declined as a counseling specialization in the United States, although the need for this intervention persists and is being met by other providers. This article illustrates how career theories such as Holland’s RIASEC theory can inform a revitalized educational counseling practice in secondary and postsecondary settings. The theory suggests that six personality types—Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional—have varying relationships with one another and that they can be associated to the same six environmental areas to assess educational and vocational adjustment. Although educational counseling can be viewed as distinctive from mental health counseling and/or career counseling, modern career theories can inform the practice of educational counseling for the benefit of students and schools.

Keywords: educational counseling, career theory, Holland, secondary education, postsecondary education

In searching for a formal definition of educational counseling, we found only one in the APA Dictionary of Psychology (VandenBos, 2007):

The counseling specialty concerned with providing advice and assistance to students in the development of their educational plans, choice of appropriate courses, and choice of college or technical school. Counseling may also be applied to improve study skills or provide assistance with school-related problems that interfere with performance, for example, learning disabilities. Educational counseling is closely associated with vocational counseling because of the relationship between educational training and occupational choice. (p. 314)

The Counseling Dictionary (Gladding, 2006) does not mention the term “educational counseling” in the following definition of counseling.

The application of mental health, psychological or human development principles, through cognitive, affective, behavioral or systemic interventions, strategies that address wellness, personal growth, or career development, as well as pathology. (Gladding, 2006, p. 37)

A renewed focus on educational counseling may be underway. The American Counseling Association meeting in Pittsburgh in 2010 brought together delegates from 29 major counseling organizations who agreed for the first time on a common definition of counseling. Educational goals were explicitly included in this definition: “Counseling is a professional relationship that empowers diverse individuals, families and groups to accomplish mental health, wellness, education, and career goals” (Breaking News, May 7, 2010).

The purpose of this article is to describe five functions essential for educational counseling (Hutson, 1958) and to use them to illustrate how Holland’s RIASEC theory might inform this counseling practice: (a) choosing a college or school for postsecondary training, (b) selecting an academic program or major, (c) adjusting to the college or academic program, (d) assessing academic performance, and (e) connecting education, career, and life decisions.

Historical Perspective

In tracing what has happened to educational counseling, a brief historical review can be helpful. In the early days of the vocational guidance movement, Brewer (1932) shifted the focus of guidance from vocation and occupation to education and instruction. He went so far as to institutionalize guidance as a professional field by linking the terms education and guidance and even using them synonymously. This could have elevated educational counseling to a more prominent position in the profession, but that did not happen. Brewer and others viewed guidance as limited by the descriptive adjective “vocational” with an emphasis on occupational choice (Shertzer & Stone, 1976), and this resulted in an estrangement between vocational and educational counseling.

Shertzer and Stone (1976) reported that the term “educational guidance” was first used in a doctoral dissertation by Truman L. Kelley at Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1914, and that he used it to describe the help given to students who had questions about choice of studies and school adjustment. Stephens (1970) pointed out that the shift from vocational choice to “guidance as education” ruptured the basic nature of the vocational guidance movement, separating the focus on “vocation” to “education.” Thus, vocational theory became associated with occupational choice and only tangentially related to educational choice, and we view this as leading to the separation of educational guidance and counseling from career theory.

In a comprehensive review of educational guidance literature published from 1933–1956, Hutson (1958) saw the counseling element of the educational guidance program as its most important function. He devoted a chapter to “Counseling for Some Common Problems” in which he identified 10 discrete but overlapping counseling situations. Several elements focused on educational counseling, including choice of subjects and curriculums, college-going (choice of going to college or working; choice of a particular college), and length of stay in school. Each of these problem areas involved counseling related to student psychological and educational characteristics, goals, and decision-making skills. Of relevance to this article, Hutson identified no theory related to educational counseling and cited only the vocational theory of Eli Ginzberg (Ginzberg, Ginsburg, Axelrad, & Herma, 1946) as informing vocational counseling. Theory-based educational counseling had not yet arrived.

The practice of educational counseling has faded from view in contemporary guidance and counseling literature. We conducted a search of journal titles and abstracts within the social sciences area using the term “educational counseling” and our university’s online library database system using Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSA) and PsychInfo. We were interested in how many “hits” for the past 10 years we would find in the following journals: Career Development Quarterly, Journal of Career Assessment, Journal of College Counseling, Journal of College Student Development, Journal of Counseling & Development, and Journal of Counseling Psychology. The search provided a total of seven results with only four falling into one of these six journals.

Advising, Coaching, Brokering

While the field of educational counseling seems to have been in decline for the past 50 years, other specialties have emerged to take its place, including academic advising, academic coaching, and educational brokering.

The field of academic advising has been very active in the past 30 years. Ender, Winston, and Miller (1984) defined developmental academic advising as “a systematic process based on a close student-advisor relationship intended to aid students in achieving educational, career, and personal goals through the utilization of the full range of institutional and community resources” (p. 19). Later, Creamer (2000) defined it as “an educational activity that depends on valid explanations of complex student behaviors and institutional conditions to assist college students in making and executing educational and life plans” (p. 18). While generally careful to distinguish between the terms advising and counseling, the National Academic Advising Association (NACADA; http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/index.htm) has fully embraced most of the educational planning and adjustment issues faced by postsecondary students that heretofore might have been included in the domain of educational counseling.

It is beyond the scope of this article to fully explore the notion of academic coaching, so we will limit our comments to the general field of life and career coaching (Chung & Gfroerer, 2003; Patterson, 2008). In general, proponents view coaching as a service focused on a student’s future goals and the creation of a new life path based on less formal collegial mentoring relationships and a positive, preventive wellness model. Opponents view coaching as practicing counseling without proper training or certification because there are limited professional standards or requirements in the coaching field.

Finally, the educational brokering movement in the 1970s was focused on helping adult learners navigate their way through postsecondary educational experiences (Heffernan, 1981). The educational broker independently assisted learners in the process of exploring, researching, and deciding on educational alternatives available. Some educational brokering proponents (Heffernan, 1981) held the view that an educational counselor employed by a specific institution would be biased and “guide” prospective students into the academic programs offered by the employing organization. Brokers were seen as neutral guides to the full range of educational options available to postsecondary learners.

Modern Career Theories

In this article, we examine the topic of educational counseling and suggest that modern career theories could contribute to a revitalization of this function. These theories, identified and described by Brown (2002), include career contextualist theory (Young, Valach, & Collin, 2002); Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription, compromise, and self-creation (L. Gottfredson, (2002); cognitive information processing theory (Sampson, Reardon, Peterson & Lenz, 2004); life stage/life space theory (Super, Savickas, & Super, 1996); narrative construction theory (Savickas, 2002); person-environment correspondence theory (Dawis, 2002); RIASEC theory (Holland, 1997); and social cognitive career theory (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 2002). We illustrate our idea of how career theory might be useful in educational guidance and counseling programs using Holland’s (1997) RIASEC theory, emphasizing the environmental aspect of the theory.

Thus far, we have identified the function of educational counseling as an early component of the developing field of guidance and counseling, and we have outlined trends that have negated that function more recently. The irony is that the need for educational counseling services remains strong today, but it needs revitalization. We believe that the application of new theory, especially career theory, would be useful in that process and inform practice and research in the field. In this article, we focus on Holland’s RIASEC theory as one theory for accomplishing this revitalization. At the same time, we draw upon some of the basic functions of educational counseling drawn from the literature (Hutson, 1958; VandenBos, 2007).

Holland’s RIASEC Theory

Holland’s theory and the related tools such as the Self-Directed Search (SDS; Holland, 1994) have become familiar icons in the career counseling field. Since the introduction of the SDS in 1972 and its use with over 29 million people worldwide (Psychological Assessment Resources, 2009), its incorporation into the Strong Interest Inventory (Harmon, Hansen, Borgen, & Hammer, 1994) and many other tools, we believe that most counselors feel comfortable and knowledgeable about this system. However, we also believe that the widespread familiarity with the hexagon and SDS is based on incomplete and outdated understandings of Holland’s contributions. For many, the theory is viewed as a simple matching model of three personality types, e.g., the three-letter SDS summary code, and the codes of occupations taken from some source, e.g., O*Net (http://online.onetcenter.org/), Occupations Finder (Holland, 2000).

One reason for the partial understanding of Holland’s theory and applications may be the result of the massive volume of research and literature that has been produced since 1957. Authors (2008) reported 1,609 reference citations from 1953–2007 in 197 different journals which make it extremely difficult to fully understand and utilize this body of work. Moreover, many articles have appeared in education journals not often read by counselors, e.g., Journal of Higher Education, Research in Higher Education, Higher Education, and the Review of Higher Education. It is no small irony that Holland’s early work was undertaken in educational settings examining students undecided about their major, adjustment to college, the nature of academic environments, and the work of the faculty within disciplines. Smart, Feldman, and Ethington (2000) recognized this gap in applying Holland’s work to higher education, and their research collaborators have published over 20 articles seeking to address it.

This article focuses on how college students struggle with varied educational decisions, e.g., undecided about their college major, and then examines the ways in which Holland’s RIASEC theory might be used in educational interventions. We begin with a review of Holland’s theory with respect to personality and environment, and then describe several practical tools based on the theory that might be used in educational counseling.

Personality

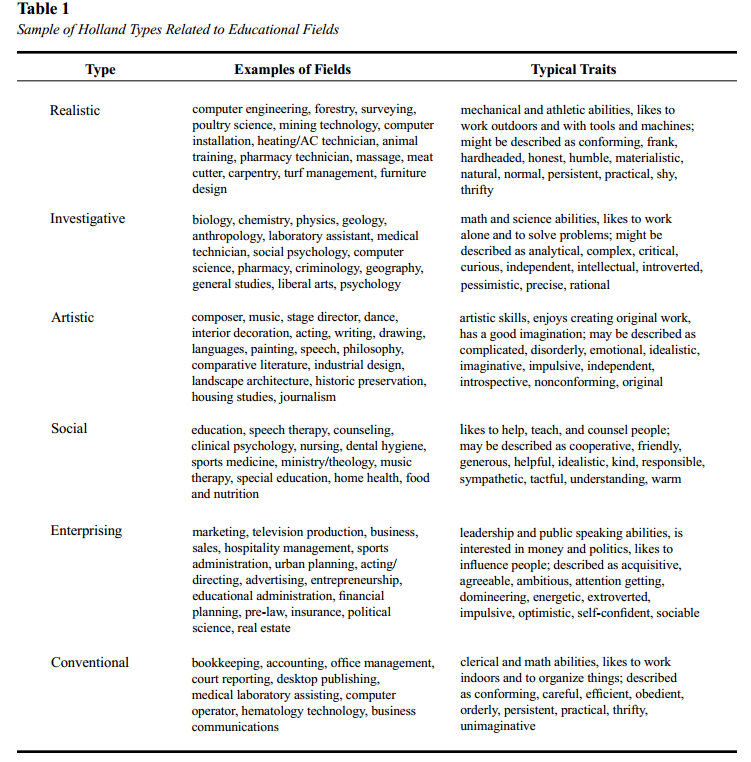

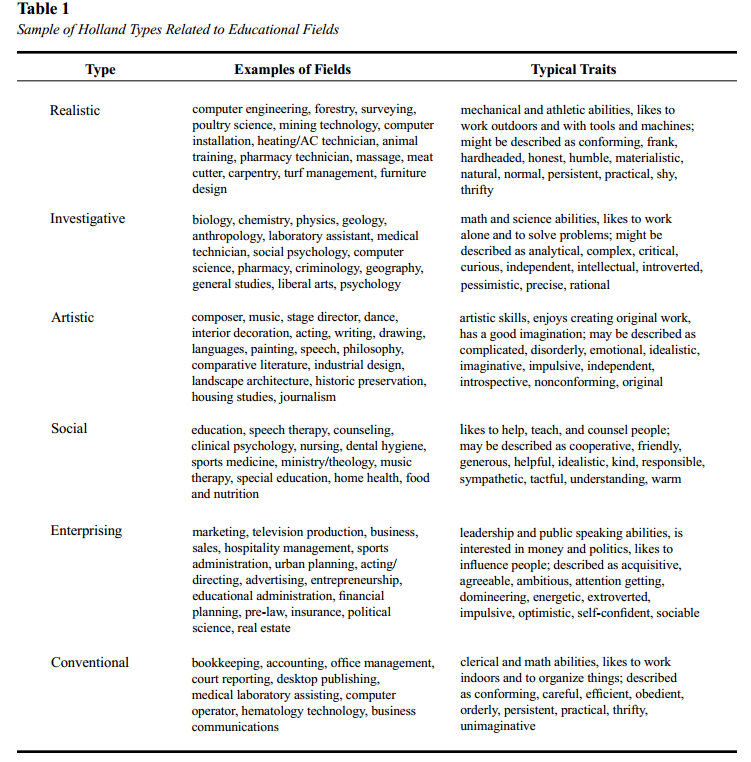

Holland’s typological theory (Holland, 1997) specifies a theoretical connection between personality and environment that makes it possible to use the same RIASEC classification system for both. Many inventories and career assessment tools use the typology to enable individuals to categorize their interests and personal characteristics in terms of combinations of the six types: Realistic (R), Investigative (I), Artistic (A), Social (S), Enterprising (E), or Conventional (C). These six types are briefly defined in relation to educational options in Table 1.

According to RIASEC theory, if a person and an environment have the same or similar codes, e.g., an Investigative person in an Investigative environment, then the person will likely be satisfied and persist in that environment (Holland, 1997). This satisfaction will result from individuals being able to express their personality in an environment that is supportive and includes other persons who have the same or similar personality traits. It should be noted that neither people nor environments are exclusively one type, but rather combinations of all six types. Their dominant type is an approximation of an ideal, modal type.

The profile of the six types can be described in terms of a number of secondary constructs, e.g., the degree of differentiation (flat or uneven profile), consistency (level of similarity of interests or characteristics on the RIASEC hexagon for the first two letters of a three-letter Holland code), or identity (stability characteristics of the type). Each of these factors moderates predictions about the behavior related to the congruence level between a person and an environment. These secondary constructs provide an in-depth schema for understanding a person’s SDS results with diagnostic implications regarding the amount of counselor involvement and skill that may be needed for an intervention (Reardon & Lenz, 1999). Given extended discussion of these ideas in other literature (Reardon & Lenz, 1998), we will not focus on them here but concentrate our attention on the environmental aspects of RIASEC theory in education.

Environments

While the personality aspects of Holland’s theory are widely known, the environmental aspects—especially of college campuses, fields of study, and work positions—are less well understood and appreciated (Gottfredson & Holland, 1996). Holland’s early efforts with the National Merit Scholarship Corporation (NMSC) and the American College Testing Program enabled him to look at colleges and academic disciplines as environments. It is important to note that RIASEC theory had its roots in higher education and later focused on occupations.

Gottfredson and Richards (1999) traced the history of Holland’s efforts to classify educational and occupational environments. Holland initially studied the numbers of incumbents in a particular environment to classify occupations or colleges in terms of RIASEC categories, but he later moved to study the characteristics of the environment independent of the persons in it. College catalogs and descriptions of academic disciplines were among the public records used to study institutional environments. Astin and Holland (1961) developed the Environmental Assessment Technique (EAT) while at the NMSC as a method for measuring college RIASEC environments.

Smart et al. (2000) presented evidence concerning the way academic departments socialize students. They reported that “faculty members in different clusters of academic disciplines create distinctly different academic environments as a consequence of their preference for alternative goals for undergraduate education, their emphasis on alternative teaching goals and student competencies in their respective classes, and their reliance on different approaches to classroom instruction and ways of interacting with students inside and outside their classes” (p. 238). Furthermore, these environments “have a strong socializing influence on change and the stability of students’ abilities and interests—that is, what students do and do not learn or acquire as a consequence of their collegiate experiences” (p. 238). Smart et al. noted that faculty in Investigative, Artistic, Social, and Enterprising disciplines create academic environments in a manner consistent with Holland’s theory, and “the degree to which academic environments are ‘successful’ in their efforts to socialize students to their respective patterns of abilities and interests thus appears to differ considerably, with Artistic and Investigative environments being the most ‘successful’ and the Social and Enterprising environments being less ‘successful’” (p. 146).

These findings suggest that students might best view academic programs in terms of the IASE schema and focus on the kinds of abilities and interests they wish to develop while in college. Such understandings and goal setting could be explored in educational counseling.

Finally, Tracey and Darcy (2002) reported that college students without an intuitive RIASEC schema for organizing information about interests and occupations experience greater career indecision. This finding suggests that the RIASEC hexagon may have a normative benefit regarding the classification of occupations and fields of study. There is increasing evidence that a RIASEC cognitive structure is associated with positive career decision variables (Tracey, 2008). Persons adhering to this structure had stronger career certainty, interest-occupation congruence, and career decision-making self-efficacy at the beginning of a career course than those not using the RIASEC structure. Moreover, teaching this structure in a career course led to increased certainty, congruence, and self-efficacy at the end of the course for those adhering to the model.

Using RIASEC Theory in Educational Counseling

In this section, we discuss the five basic educational counseling functions identified by Hutson (1958), and how Holland’s RIASEC theory might inform this practice. To address these five problems in educational counseling from a RIASEC perspective, it would be important for the counselor to have a basic understanding of Holland’s theory (Holland, 1997). The client might complete the Self-Directed Search (Holland, 1994) and review the Occupations Finder (Holland, 2000), Educational Opportunities Finder (Rosen, Holmberg, & Holland, 1997), and You and Your Career (Holland, 1994) booklets. These materials operationalize and explain the theory in client terms. Armed with this basic information and these tools, the counselor and client can enter into a collaborative relationship to resolve educational problems and make educational decisions.

Choosing a College or School

The number of options for education and training is very large. Choices Planner (Bridges, 2009) was examined for one state and 196 postsecondary schools offering associate, bachelors, and professional (postgraduate) degrees were found. The Choices system makes it possible to use varied criteria for selecting among these options, including five school types, (e.g., public, private), specific miles from a designated ZIP postal code, six regions of the state, five campus or town settings of the school, eight tuition ranges, five affiliations (e.g., women, religious), on-campus housing, and over 30 sports options for men or women. If the student wanted to explore options in additional states the number of options would grow exponentially.

The array of postsecondary schools has very limited options for Realistic and Conventional types, which led Smart et al. (2000) to exclude these areas from their study of baccalaureate level colleges and universities. College level occupations are least frequently associated with the Conventional and Realistic categories, while Investigative and Artistic work are most likely associated with college level employment or the highest level of cognitive ability. Smart et al. found few college majors, faculty, or students in their samples categorized as Realistic or Conventional.

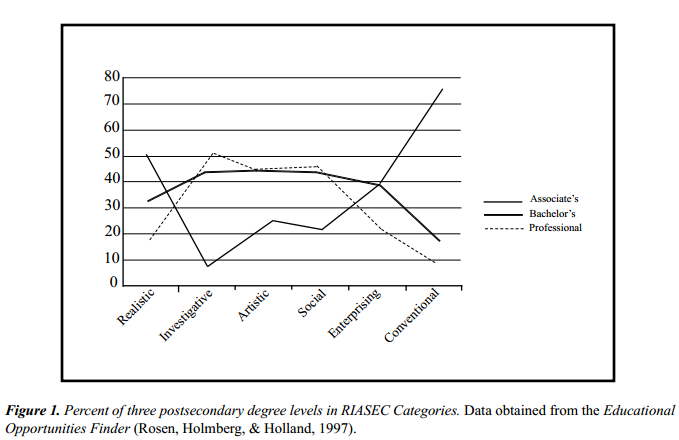

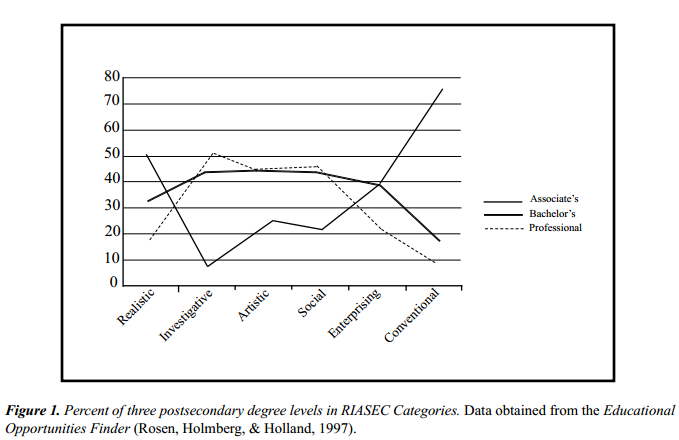

Taking this a step further, the number of associate, bachelors, and professional academic programs listed in the Educational Opportunities Finder (EOF; Rosen et al., 1997) were tabulated in relation to RIASEC categories. Of the 750 postsecondary programs of study listed in the EOF, there were 296 offered at the associate level, 492 at the bachelor’s level, and 645 at the professional level. Because some programs are offered at more than one degree level, the resulting total degree programs listed in the EOF number 1,517. Inspection of Figure 1 shows proportionally more Realistic and Conventional programs are available at the associate degree level in comparison to the other two degrees. Conversely, more professional degrees are offered in the IAS categories. This suggests that vocational technical schools and community colleges would be the types of schools most likely offering programs in these two areas. In this way, RIASEC theory could be used to guide selection of a school.

Authors (1996) documented this phenomenon in their research and reported that the student body at their postsecondary institution was composed predominately of S, E, and I types, creating an SEI-type school. They reported 153 fields of study at the university enrolled 10,439 students with declared majors in the following categories: R, 5%; I, 19%; A, 13%; S, 34%; E, 19%; and C, 10%. This suggests a student body with a profile of SEIACR. Such a student population would find C and R types in a minority.

RIASEC theory can inform the process of choosing a college by providing a conceptual schema of six environments and judging the priority and influence of each in socializing enrolled students. Students with E-type personalities (e.g., interests and skills) might have the best fit in a school that reinforced and prized those traits, and the same would be true for the remaining RIASC environments. In the following sections we will explain more how the environmental aspect of RIASEC theory may be used in educational counseling.

Selecting an Academic Program or Major

The Choices Planner (Bridges, 2009) lists over 780 specific academic programs or fields of study (majors) for students for the selected state. Large universities may have several hundred undergraduate majors and this can be overwhelming to students required to pick one field. Holland’s RIASEC schema can help to make the process of exploring and selecting options less daunting. This section describes some ways this might happen.

First, when students understand the basic elements of RIASEC theory they are armed with a schema for categorizing a great amount of academic information. Table 1 illustrates the operation of this schema in practical terms. Students intent on pursuing a bachelor’s degree can be informed that most college fields of study or disciplines are concentrated in Holland’s Investigative, Artistic, Social, and Enterprising areas (Smart et al., 2000), which reduces hundreds of options to four areas.

Second, the research by Smart et al. (2000) of bachelor’s programs was based on the idea that “faculty create academic environments inclined to require, reinforce, and reward the distinctive patterns of abilities and interests of students in a manner consistent with Holland’s theory” (p. 96). Moreover, “students are not passive participants in the search for academic majors and careers; rather, they actively search for and select academic environments that encourage them to develop further their characteristic interests and abilities and to enter (and be successful in) their chosen career fields” (p. 52). This is an important idea because it puts the power of informed choice in the hands of students as they explore educational options. They can actively select the type of environment in which they desire to spend their time and in which they wish to learn while in college.

Third, Smart et al. (2000) described primary and secondary recruits entering bachelor’s level academic programs. Primary recruits were freshmen entering disciplines directly from secondary school (discussed in this section) and secondary recruits (discussed in the next section) were those who changed their minds after entering college. Based on their research, Smart et al. found that two-thirds of freshmen (primary recruits) initially selected majors in the Social area and remained in that area over four years, while only slightly more than half of the students in the Enterprising area persisted in that area over four years. Students in the Artistic and Investigative areas both persisted over four years at 64%. Overall, about two-thirds of freshmen (primary recruits) persisted in one of the four disciplines initially selected and about 30% changed to another area.

The information gleaned from research by Smart and his colleagues of bachelor’s level programs can help inoculate students for relief of some of the anxiety regarding the selection of an academic program. Rather than simply focusing on the occupations related to a major in making a choice, students can focus on the nature and characteristics of the IASE environments and prioritize them according to their goals, interests, values, and skills. These understandings would also help students search for information about academic programs that provide details about whether or not the way life in the program is consistent or inconsistent with the theoretical RIASEC environment characteristics, e.g., student relationships with professors, classroom activities, nature of learning projects, leadership styles favored.

Adjusting to the College or Academic Program

Faculty in IASE disciplines create specialized academic environments that are shared by the students selecting these majors. The variability in the socialization styles and the effects of the environments on student behaviors and thinking were described by Smart et al. (2000) and are summarized below. Increased understanding of these environmental characteristics is important in educational counseling and for student decisions about preferred fields of study.

Faculty in Investigative environments place primary attention on developing analytical, mathematical, and scientific competencies, with little attention given to character and career development. They rely more than other faculty on formal and structured teaching and learning, they are subject-matter centered, and they have specific course requirements. They focus on examinations and grades. This environment has the highest percentage of primary recruits (e.g., students select it as freshmen).

Faculty in Artistic environments focus on aesthetics and with an emphasis on emotions, sensations, and the mind. The curriculum stresses learning about literature and the arts, as well as becoming a creative thinker. Faculty also emphasize character development, along with student freedom and independence in learning.

Varied instructional strategies are used in these disciplines.

Faculty in Social environments have a strong community orientation characterized by friendliness and warmth. Like the Artistic environment, faculty place value on developing a historical perspective of the field and an emphasis on student values and character development. Unlike the Artistic environment, faculty also place value on humanitarian, teaching, and interpersonal competencies. Colleagueship and student independence and freedom are supported, and informal small group teaching is employed.

The Enterprising environment has a strong orientation to career preparation and status acquisition. Faculty focus on leadership development, the development and use of social power to attain career goals, and striving for common indicators of organizational and career success. Teaching strategies in this environment are very balanced, but faculty like most to work with career-oriented students regarding specialized issues related to organizational and individual achievement.

Once an academic program is selected as a major field of study and the student begins to interact with other students and faculty in the program, more information of a personal nature is acquired which can lead to adjustments that the student will need to make to excel in that environment. For example, when Smart et al. (2000) examined college environments (the percentage of seniors in each of the IASE areas), they found that from 30–50% of the four environments were composed of primary recruits and about half were secondary recruits, e.g., the seniors who had changed their majors. This means that almost half the seniors ended up in an IASE discipline that was different from their initial choice.

Students migrated to and from the four environments in different ways. For example, two-thirds of the seniors in the Artistic environment were secondary recruits from one of the other areas; they did not intend to major in the Artistic area in their freshman year. In addition, about one third of the students migrating into the Social area came from Investigative, Enterprising, or undecided areas. Stated another way, the Social environments appear to be the most accepting and least demanding of the four environments studied by Smart et al. (2000) and Social disciplines seem to have the least impact and the least gains in related interests and abilities. Students moving into the Investigative area were most likely to come from the Enterprising area, and vice versa.

These findings (Smart et al., 2000) reveal the fluid nature of students’ major selections and the heterogeneous nature of the four environments with respect to the students’ initial major preferences. They also provide information regarding the migration of students among the IASE disciplines, and this can inform educational planning for students and counselors about the way in which these four disciplines interact with different types of students.

In summary, Smart et al. (2000) found that congruent students in Investigative, Artistic, and Enterprising environments increased their pattern of self-reported interests and abilities over four years by further developing what was already present in their personality. These three environments also increased the related traits for incongruent students, but the gap between the congruent and incongruent students did not decrease over time. In other words, students in both congruent and incongruent environments made equivalent or parallel changes in self-reported abilities and interests over four years, but students in congruent environments had higher levels of interests and abilities at the end of four years. Investigative and Enterprising environments had the most impact on student characteristics. These findings, if communicated to students in educational counseling, could affect the nature of discussions about students’ educational goals in college.

Assessing Academic Performance

Early in his career, Holland (1957) began to discuss the impact of college on students and how varied personality traits and beliefs other than aptitude were associated with success. Gottfredson (1999) noted that Holland’s early research demonstrated that much of the output from the college experience was related to what students brought into that experience. According to Gottfredson, Holland promoted the idea that college selection practices relying heavily on measures of academic potential resulted in much lost talent, e.g., selection of the top 10% of high school students based only on grades would exclude about 86% of high school class presidents (Enterprising types). The idea that noncognitive traits (e.g., RIASEC personality types) would be important in assessing academic performance is a noteworthy contribution of Holland’s theorizing and research.

Academic success is sometimes measured in terms of persistence on the part of the student or retention on the part of the institution. Other immediate outcome measures might include the grade point average, student satisfaction, awards received, or engagement in program activities, while longer term outcomes might include professional accomplishments, contributions, and recognitions. It should be noted that while all academic programs require cognitive skill and ability, some programs further emphasize interests and abilities related to the RIASEC areas identified in Table 1. These could include creativity, leadership, community service, and the like.

According to RIASEC theory, students in an environment that is highly congruent or matches with their personality will persist in that environment and achieve awards and recognition from the environment. In the process of educational counseling, students should have opportunities to clarify what it means to be in, or move to or out of, an environment that either matches their type or provides an opportunity to develop desired skills and interests. Their achievements and satisfaction would theoretically be related to the quality of the match between their personality and the environmental characteristics.

Connecting Education to Career and Life

Holland’s RIASEC theory provides a relatively simple, effective scheme for thinking about people (e.g., personalities, traits, interests, values, behaviors, attitudes) and their options (e.g., educational programs, occupations, work organizations, leisure activities). Conceptualizing people and options in these six areas can improve personal and career decision making.

Several examples of this strategy are apparent. For example, when students conduct information interviews they might structure questions and make observations about the degree to which the various RIASEC codes are prevalent in the life of the interviewee or characterize the organizational setting. In considering job offers, students might use the RIASEC schema to assess the quality of the fit between their personality and the culture of the organization, or more particularly, the personality of their immediate supervisor.

The UMaps project at the University of Maryland is a good example of applying RIASEC theory to life/career options (Jacoby, Rue, & Allen, 1984). The UMaps program operated out of the Office of Commuter Affairs in the Division of Student Affairs and was designed to help students become aware of diverse campus opportunities, options, and resources related to RIASEC types. Using both large posters displayed on bulletin boards and brochures distributed by advisors, each of the six RIASEC UMaps had a standard layout including areas of study (with office locations and phone numbers), sample career possibilities, internship and volunteer options, and student organizations and activities related to each type. Each map also had a brief description of the RIASEC type and a brief self-assessment related to interests and skills.

As reported earlier, Reardon, Lenz, and Strausberger (1996) used an earlier version of the Educational Opportunities Finder (Rosen et al., 1997) to classify all of the majors at a large university, and then used these data to assess the types of students seeking services in the career center and to design appropriate interventions. For example, it was judged that Realistic and Investigative students might prefer independent career planning using a computer-assisted guidance system, e.g., Choices Planner, rather than an individual counseling session.

Descriptive information about college majors could include the kinds of information summarized by Smart et al. (2000) about course structures, learning style expectations, faculty interests and activities, and program objectives. Other student information materials could list volunteer experiences related to the discipline (if any), introductory classes, sample employment opportunities, and profiles of graduates. Brochures and other descriptive information used in academic advising and educational counseling could be indexed or include information about Holland codes. These examples illustrate the ways in which RIASEC theory applied in educational counseling might be extended to broader life and career decisions.

Summary and Implications

This article illustrates how the educational counseling function has become estranged or lost in traditional counseling practice in secondary and postsecondary settings. While educational counseling can be viewed as distinctive from mental health counseling and/or career counseling, modern career theories can inform the practice of educational counseling for the benefit of students and schools. Holland’s RIASEC career theory, especially the extensive research on educational environments conducted by Smart and his associates (2000) and reported in more than six different journals, was used to illustrate this idea.

Educational counselors using RIASEC theory need to be fully informed about the theory, the research that supports it, the instruments that are based upon it, and the counseling techniques that could be derived from it. Such theory-driven practice might represent a new paradigm in educational counseling. Holland’s (1997) theory, like other career theories, has the most power when the extremes of wealth, social class, genetic traits, and health are not in effect. In other words, career theory probably works best in educational counseling for students in general rather than those at the extremes of any personal trait or situation.

RIASEC theory can be useful in educational counseling by specifying the kinds of conditions and traits associated with difficulties in educational decision making. Authors (1998, 1999) and Holland, Gottfredson, and Nafziger (1975) indicated that persons with poor diagnostic signs on the Self-Directed Search, e.g., lack of congruence between expressed and assessed summary codes, low differentiation, low consistency, low coherence among aspirations, low profile elevation, and a high point code in the Realistic or Conventional area, were likely candidates for more intensive counseling interventions. This is a special province of educational counselors because of their professional counselor training as opposed to the standard training for academic advisors or coaches. Students with high Artistic codes also may be problematic because of their preference for a non-rational approach to decision making (Holland et al., 1975). Persons with such diagnostic signs will likely need more time and professional, individualized counselor assistance in career problem solving and decision making.

Smart et al.’s (2000) research reveals some of the variations in academic departments and suggests implications for college and university organizational systems. It is important for counselors and other staff to inform students about the impact of majors and academic disciplines on the development of student interests and skills. At present, advisors make students aware of many aspects of a major, e.g., required courses, prerequisites, entrance requirements, and the occupations most closely aligned with the major. Providing additional information based on the research findings by Smart et al. regarding the way academic environments socialize or affect students pursuing that major will make students better “consumers” of majors or “shoppers” of academic programs.

References

Astin, A. W., & Holland, J. L. (1961). The Environmental Assessment Technique: A way to measure college environments. Journal of Educational Psychology, 52, 308–316.

Breaking News: 20/20 Delegates Reach Consensus Definition of Counseling. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/20-20/index.aspx, May 7, 2010.

Brewer, J. (1932). Education as guidance. New York, NY: Macmillian.

Bridges.com Co. (2009). Choices [Computer software]. Oroville, WA: Author.

Brown, D. (Ed.). (2002). Career choice and development (4th. ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chung, Y. B., & Gfroerer, M. C. A. (2003). Career coaching: Practice, training, professional, and ethical issues. Career Development Quarterly, 52, 141–152.

Creamer, D. G. (2000). Use of theory in academic advising. In V. N. Gordon & W. R. Habley (Eds.), Academic advising: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 18–34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Dawis, R. V. (2002). Person-environment-correspondence theory. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 427–464). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ender, S. C., Winston, Jr., R. B., & Miller, T. K. (1984). Academic advising reconsidered. In R. B. Winston, Jr., T. K. Miller, S. C. Ender, & T. J. Grites (Eds.), Developmental academic advising: Addressing students’ educational, career, and personal needs (pp. 3–34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ginzberg, E., Ginsburg, S., Axelrad, S., & Herma, J. L. (1946). Occupational choice. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gladding, S. T. (2006). The counseling dictionary: Concise definitions of frequently used terms (2nd. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Gottfredson, G. D. (1999). John L. Holland’s contributions to vocational psychology: A review and evaluation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 15–40.

Gottfredson, G. D., & Holland, J. L. (1996) The dictionary of Holland occupational codes. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2002). Gottfredson’s theory of circumscription, compromise, and self- creation. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 85–148). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Gottfredson, L. S., & Richards, J. M., Jr. (1999). The meaning and measurement of environments in Holland’s theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 57–73.

Harmon, L. W., Hansen, J. C., Borgen, F. H., & Hammer, A. L. (1994). Strong Interest Inventory: Applications and technical guide. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Heffernan, J. M. (1981). Educational and career services for adults. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices (3rd. ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (2000). Occupations finder. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (1994). The Self-Directed Search. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J. L. (1957). Undergraduate origins of American Scientists. Science, 126, 433–437.

Holland, J. L. (1994). You and your career. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Holland, J., Gottfredson, G., & Nafziger, D. (1975). Testing the validity of some theoretical signs of vocational decision-making ability. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22, 411–422.

Hutson, P. W. (1958). The guidance function in education. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Jacoby, B., Rue, P., & Allen, K. (1984). U-Maps: A person-environment approach to helping students make critical choices. Personnel & Guidance Journal, 62, 426–28.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. 2002). Social cognitive career theory. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th. ed., pp. 255–311). San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass.

Patterson, J. (2008). Counseling vs. life coaching. Counseling Today, 5(6), 32–37.

Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. (2009). PAR catalog of professional testing resources, 32(4), 235–247.

Reardon, R. C., & Lenz, J. L. (1999). Holland’s theory and career assessment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55, 102–113.

Reardon, R. C., & Lenz, J. L. (1998). The Self-Directed Search and related Holland career materials: A practitioner’s guide. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Reardon, R. C., Lenz, J. L., & Strausberger, S. (1996). Integrating theory, practice, and research with the Self-Directed Search: Computer Version (Form R). Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 28, 211–218.

Rosen, D., Holmberg, K, & Holland, J. L. (1997). The educational opportunities finder. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Ruff, E. A., Reardon, R. C., & Bertoch, S. C. (2008, June). Holland’s RIASEC theory and\applications: Exploring a comprehensive bibliography. Career Convergence, http://209.235.208.145/cgibin/WebSuite/tcsAssnWebSuite.pl?Action=DisplayNewsDetails&RecordID=1164&Sections=3&IncludeDropped=0&NoTemplate=1&AssnID=NCDA&DBCode=130285.

Sampson, J. P., Jr., Reardon, R. C., Peterson, G. W., & Lenz, J. L. (2004). Career counseling and services: A cognitive information processing approach. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth-Brooks/Cole.

Savickas, M. (2002). Career construction: A developmental theory of vocational behavior. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th ed., pp.149–205). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Shertzer, B., & Stone, S. C. (1976). Fundamentals of guidance (3rd. ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Smart, J. C., Feldman, K. A., & Ethington, C. A. (2000). Academic disciplines: Holland’s theory and the study of college students and faculty. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Stephens, J. (1970). Social reform and the origins of vocational guidance. Washington, DC: NVGA.

Super, D. E., Savickas, M. L., & Super, C. M. (1996). The life-span, life-space approach to careers. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associates, Career choice and development (3rd ed., pp. 121–170). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Tracey, T. J. G. (2008). Adherence to RIASEC structure as a key career decision construct. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 146–157.

Tracey, T. J. G., & Darcy, M. (2002). An idiothetic examination of vocational interests and their relation to career decidedness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 420–427.

VandenBos, G. R. (Ed.). 2007). APA dictionary of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Young, R., Valach, L., & Collin, A. (2002). A contextualist explanation of career. In D. Brown & Associates, Career choice and development (4th. ed., pp. 206–254). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Robert C. Reardon, NCC, is Professor Emeritus and Sara C. Bertoch, NCC, is a career advisor, both at the Career Center at Florida State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Robert C. Reardon, Florida State University Career Center,

PO Box 3064162, Tallahassee, FL, 32306, rreardon@fsu.edu.

Apr 7, 2014 | Author Videos, Volume 4 - Issue 1

Thomas A. Field

Abstract: Based on emerging findings from neuroscience, the counseling professional can consider a different approach to research-informed practice, by integrating left- and right-brain processing in client care. This new model is commensurate with counseling’s historical lineage of valuing the counseling relationship as the core ingredient of effective counseling.

Keywords: counseling, neuroscience, evidence-based, effectiveness, right-hemisphere, intuition

During the past decade, the field of counseling has considered the notion of identifying effective counseling practices. In 2005, the American Counseling Association’s (ACA) Code of Ethics included a recommendation to use therapies that “have an empirical or scientific foundation” (C.6.e). The Journal of Counseling & Development introduced a new journal feature in 2007, entitled “Best Practices.” In 2009, the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) modified their Standards for addiction counseling (I.3., p. 22), clinical mental health counseling (I.3., p. 34), and marriage, couple, and family counseling (I.3., p. 39) to require that the student “knows evidence-based treatments” (EBTs; p. 5). In the September 2012 edition of Counseling Today, Dr. Bradley Erford, the current ACA President, asserted the following in his monthly column:

If professional counselors use the best available research-based approaches to help clients and students, then counselor effectiveness, client satisfaction and third-party insurer satisfaction all improve. When professional counselors provide effective services, it also helps our professional advocacy and lobbying efforts with federal, state, and local politicians and bureaucrats, and leads to more counseling jobs and higher pay scales.(p. 5)

Erford argues that counselors must use research to inform practice—the public, insurance companies, and clients demand it. Yet until recently, only one approach to research-informed practice has been available to the counseling profession—namely the EBT movement that originated in the field of psychology. Many techniques and theories exist outside of the EBT movement, in addition to other models for best practices such as the common factors movement (Duncan, Miller, Wampold, & Hubble, 2010). Counselors may feel confused about which model to follow. An approach to research-informed practice that is more commensurate with the counseling profession’s values and identity is the application of research evidence from neuroscience to inform counseling interventions.

Current Direction: The Left-Brain Pathway

The left side of the brain is responsible for rational, logical, and abstract cognition and conscious knowledge. Neuroscientists such as Allan Schore (2012) have suggested that activities associated with the left hemisphere (LH) currently dominate mental health services. This is evidenced by the current reliance upon psychopharmacology over counseling services, the manualization of counseling, a reductionist and idealistic view of “evidence-based practice,” and a lack of respect for the counseling relationship in client outcomes despite a large body of evidence. McGilchrist (2009) takes this argument further: if left unchecked, the modern world will increase its reliance upon the LH compared to the than right hemisphere (RH), with disastrous consequences. A “left-brain world” would lead to increased bureaucracy, a focus on quantity and efficiency over quality, and a valuing of technology over human interaction, and uniformity over individualization. While this dystopia has not been fully realized yet, one could argue that the field’s current reductionist and cookie-cutter approach to mental health services and reliance on quantitative over qualitative research all point in one direction.

To understand the importance of the association between the LH and the current mental health system, the author reviews the history of the counseling effectiveness movement, along with the counseling profession’s gradual adherence to this left-brain movement.

The History of “Effectiveness”

It is hard to know when the term effectiveness was first used in counseling circles. A long history of competition exists between different theoretical schools that sought to find evidence for the efficacy of their theory and discredit (or at least, disprove) all pretenders. Eventually, in 1995, the American Psychological Association (APA) defined effectiveness by identifying counseling interventions that were considered to have adequate research support (Task Force for Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures, 1995). The criteria for delineation were narrow: at least two randomized controlled studies or multiple pre-and post- individual studies, and the existence of a treatment manual. This model of efficacy was based on the Federal Drug Administration’s (FDA) criteria for what constituted acceptable research evidence for a new medication’s efficacy. The field of psychology was concerned at the time about medications being considered the “first line of treatment” for mental disorders instead of counseling and psychotherapy, thus wanting to provide empirical evidence for counseling efficacy that could be used for political and financial leverage in the marketplace (LaRoche & Christopher, 2009). Various terms were used for this movement: psychological treatments, empirically validated treatments, empirically supported treatments, and EBT. This movement soon became synonymous with the definition of effectiveness in counseling and psychotherapy.

Criticisms abounded throughout the mental health services community. It became apparent that these interventions were difficult to implement, or else that practitioners were resistant (Becker, Stice, Shaw, & Woda, 2009). Criticisms focused on the inadequate representation of certain demographic and minority groups, the disregard for the predominance of co-occurring disorders within client populations, the exclusionary definition of “research evidence,” and the lack of consideration for clinical expertise and judgment (Bernal & Scharró-del-Rio, 2001; LaRoche & Christopher, 2009).

Training programs in the mental health services field have also been resistant to training students in EBTs. Weissman et al. (2006) found that only 28.1% of psychiatry preparation programs and 9.8% of social work preparation programs required both didactic instruction and clinical supervision in EBT use. In clinical psychology preparation programs, 16.5% (PhD) and 11.5% (PsyD) required didactic instruction and clinical supervision in EBTs. This is a low rate, considering that the inclusion of training in psychological treatments is required for APA doctoral program accreditation (Chambless, 1999). No data are currently available on the percentage of counselor education programs that require both didactic instruction and clinical supervision in EBT use. However, one could argue that the 2009 CACREP Standards mandate instruction and supervision in the use of EBTs. If counselors do not find another path, counselor education may adhere to the training model of psychology, requiring a greater emphasis on teaching techniques rather than relational skills, and inflexibly following standards of practice rather than individualized instruction. Counselor education may become a left-brain discipline.

Counseling Approaches and the Left-Brain

Counselors are already using EBTs in practice settings. Field, Farnsworth, and Nielsen (2011) conducted a small unpublished national pilot study in the use of EBTs by National Certified Counselors (NCCs; n = 76). Demographics were consistent with the most recent demographical survey of NCCs (National Board of Certified Counselors, 2000). The majority of participants reported utilizing EBTs within the past year (69.4%), and the number of EBTs utilized was surprisingly high (M = 9.17, SD = 6.94, SEM = 0.97) for those who utilized EBTs. Furthermore, of those who used EBTs, only 6% (n = 3) did not report using a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Although this was a small pilot study, and thus results cannot be wholly generalized to the counselor population, initial findings seem to indicate that EBT utilization may be practically synonymous with CBT utilization. This is alarming, since research has shown that when psychotherapies are directly compared to one another, studies in which CBT is claimed to be more beneficial than other treatments subsequently achieved comparative outcomes (e.g., Wampold, Minami, Baskin, & Tierney, 2002). The apparent “fit” between CBT and the EBT movement can be elucidated when considering that following a manualized protocol and using conscious verbal analysis (CBT) are both LH functions, and studies have found a link between CBT and activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the LH (Siegle, Steinhauer, Friedman, Thompson, & Thase, 2011). Put simply, CBT activates the LH, and the EBT movement values LH over RH processing.

It could be argued that the emergence of the EBT movement has propelled CBT into first place among interventions used in practice settings. Structured interventions that can be easily manualized and measured such as CBT seem to correspond with strict and rigid guidelines for empiricism compared to therapies that are more abstract and unstructured (e.g., humanistic-existential and relational forms of counseling). The dominance of CBT may only solidify following the initiation of EBT training within graduate programs. Yet even Aaron T. Beck, the founder of cognitive therapy, asserted that “you can’t do cognitive therapy from a manual any more than you can do surgery from a manual” (Carey, 2004, p. F06). In other words, the purely LH approach of rigidly following a treatment manual is not sufficient for effective counseling practice.

The Right-Brain Pathway

The right side of the brain is associated with unconscious social and emotional learning, and includes intuition, empathy, creativity, and flexibility. Some may argue that counseling has always been associated with RH processes (J. Presbury, personal communication, November 25, 2012). There are signs that the field of counseling is moving toward the valuing of RH processes during interventions, evidenced by the empirical respect attributed to the therapeutic relationship (e.g., Magnavita, 2006; Norcross & Wampold, 2011; Orlinsky, Ronnestad, & Willutzki, 2004), and the admission that EBTs are unsuccessful if applied rigidly. The APA Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006) intoned that “sensitivity and flexibility in the administration of therapeutic interventions produces better outcomes than rigid application of…principles” (p. 278). A purely LH counseling approach may be overly rigid, problematic since counselor rigidity has been found to impair the counselor-client relationship (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2001).

Clinical Judgment vs. Intuition

In 2006, the APA issued a new definition of evidence-based practice, derived largely from the definition provided in 2001 by the Institute of Medicine (APA, 2006). Evidence-based practice was redefined as consisting of three elements: research evidence, clinical judgment, and client contextual variables (APA, 2006; Institute of Medicine, 2001). Yet the APA’s revised definition of evidence-based practice still privileged LH processing. Whereas clinical judgment can be defined as the application of rational and analytical reasoning when working with clients (LH function), clinical intuition can be described as the attunement to unconscious and implicit knowledge when working with clients, and has been associated with activation in areas of the RH (Bolte & Goschke, 2005). Often difficult to articulate, intuition has been commonly described as “the unthought known,” a “gut feeling,” and “a working hypothesis” (Bollas, 1987). Lieberman (2000) defined clinical intuition as “the subjective experience associated with the use of knowledge gained through implicit learning” (p. 109). It is now known that effective counseling requires both conscious reasoning and unconscious intuition—in other words, the integration of the LH and RH of the brain. As the famous attachment theorist John Bowlby (1991) once wrote, “clearly the best therapy is done by the therapist who is naturally intuitive and also guided by the appropriate theory” (p. 16).

Studies on counselor development have found that experienced counselors tend to rely more on intuition than manualized protocols (Rønnestad & Skovolt, 2003; Stoltenberg, McNeill, & Delworth, 1998). As any experienced practitioner can attest, counselors tend to learn intuitive skills such as timing and word choice with experience. Welling (2005) wrote, “no therapist can reasonably deny following hunches, experiencing sudden insights, choosing directions without really knowing why, or having uncanny feelings that turn out to be of great importance for therapy” (p. 19). Volz and von Cramon (2008) concluded that the counselor’s intuition is often reliable and accurate during the counseling process. The difference between novice and experienced counselors can be understood as a difference in amount of accumulated experiences from prior client encounters within the unconscious, which informs intuitive clinical judgments (Schore, 2012). Less-experienced counselors are prone to make more inaccurate intuitive clinical decisions given their lesser clinical experience and, therefore, their less sculpted unconscious intuition.

Creativity vs. Replication

Creativity in the counseling process allows clinicians to individualize treatment, and consider the client’s contextual values during decision making (APA, 2006). This is the third part of the APA’s definition of evidence-based practice. Creativity has also been associated with the RH (Grabner, Fink, & Neubauer, 2007), and occurs when counselors are attuned to implicit memories. Creativity occurs when counselors trust their unconscious, where novel ideas are generated, based on environmental cues. Creativity is typically an emergent and unconscious process, unfolding in the immediacy of the counseling room. Counselors often cannot fully prepare for what the client brings to the session. Every session therefore requires some degree of creativity by the counselor, whose flexible response to the interpersonal contact with the client is crucial to establishing a deep and sustained therapeutic bond. For this reason, there is no existing evidence-based protocol for nonverbal body language or affective response by the counselor; these behaviors and responses are highly individualized and contextual, and thus cannot be manualized. Without creativity, the counselor is reduced to the role of technician, administering treatments in a consistent yet rote and rigid manner. The manualization of counseling naturally limits the creative process and RH processing for both counselor and client. While studies are needed, it is possible that a rigid LH approach to the counseling process would restrict rather than enhance the creative capacities of counselor and client, and neglect the client’s natural problem-solving ability (Bohart & Tallman, 2010).

To take a purely LH approach to counseling is to negate the importance of unconscious intuition and clinical experience in counselor effectiveness. Shrinking clinical expertise to merely conscious decision making is reductionist and misses a large body of evidence suggesting that unconscious information also guides clinical decisions. It is entirely possible that many clinical decisions are based more on RH than LH processes. For example, some counselors have experienced moments with clients when they instinctively know the diagnosis or what problem a client is experiencing, without formally checking off symptoms from diagnostic criteria. Counselor educators and supervisors can help trainees to hone unconscious intuition by asking questions such as the following: What is your gut feeling about this client? What prior clinical experiences may have led you to that conclusion? What unconscious decisions have you made that you were satisfied with? What unconscious information are you ignoring or suppressing.

The Centrality of the Counseling Relationship

The importance of RH processing extends to the counseling relationship, which is considered to have a central role in client outcomes. In 2001, the APA formed a Task Force on Evidence-Based Therapy Relationships, concluding in 2011 that the counseling relationship was central to client outcomes to an equivalent or greater extent as the treatment method, and “efforts to promulgate best practices or evidence-based practices (EBPs) without including the relationship are seriously incomplete and potentially misleading” (Norcross & Wampold, 2011, p. 98). Fifty years of research support the centrality of the counseling relationship in client outcomes (Orlinsky et al., 2004). Magnavita (2006) concluded, “the quality of the therapeutic relationship is probably the most robust aspect of therapeutic outcome” (p. 888). By the end of the 1990s, counseling was beginning to move toward a two-person interpersonal model in place of a one-person intrapersonal model for conceptualizing client problems and planning treatment (Cozolino, 2010). Some have argued that identifying and utilizing specialized treatments for certain disorders is therefore misleading, since research studies have consistently found that the “confounding variable” of the therapeutic relationship is the primary factor for counseling efficacy (Norcross & Wampold, 2011).

During counselor-client interactions, the level of intersubjective attunement and engagement strongly influences the quality of this interpersonal contact. As Bromberg (2006) wrote, when counselors try to “know” their clients instead of “understand” their clients through their engagement in the shared intersubjective field of the here and now, “an act of recognition (not understanding) takes place in which words and thoughts come to symbolize experience instead of substitute for it” (p. 11). When this moment of meeting occurs, the client can safely contact, describe, and regulate inner experience. During the client’s heightened emotional states, the counselor can model healthy emotional regulation for the client. This secure holding environment enables clients to experience and cope with their own dysregulated emotions and thus serves as a corrective emotional experience. Because the LH is specialized to manage “ordinary and familiar circumstances” while the RH is specialized to manage emotional arousal and interpersonal interactions (MacNeilage, Rogers, & Vallortigara, 2009), many if not most counseling interventions enhance RH processing for both counselor and client.

Neuroscience supports the integration of both the LH and RH in interactions between counselor and client. The counseling relationship is informed by linguistic content and auditory input (LH function), in addition to visual-facial input, tactile input, proprioceptive input (the body’s movement in space), nonverbal gestures, and body language (RH function). Whereas the LH is involved in conscious processing of language, the RH is responsible for a large amount of social and emotional behavior that occurs during the counseling relationship, such as the moment of contact between counselor and client (Stern, 2004), attention to the external environment (Raz, 2004), empathic resonance of both linguistic content and nonverbal behavior (Keenan, Rubio, Racipoppi, Johnson, & Barnacz, 2005), mental creativity (Asari, Konishi, Jimura, Chikazoe, Nakamura, & Miyashita, 2008), social learning (Cozolino, 2010), emotional words (Kuchinke, Jacobs, Võ, Conrad, Grubich, & Herrmann, 2006), and emotional arousal (MacNeilage et al., 2009). Clearly, all of these RH functions are crucial to the development of a strong counseling relationship. One cannot establish an effective counseling relationship by merely attending to verbal content (LH); a strong counseling relationship requires the integration of both LH and RH processes. Approximately 60% of communication is nonverbal (Burgoon, 1985), which is a RH function (Benowitz, Bear, Rosenthal, Mesulam, Zaidel, & Sperry, 1983). Since so much of counseling is nonverbal and unspoken, yet “known” to the counselor, the practice can be better understood as a communication cure rather than a talking cure (Schore, 2012).

Proposed Direction: Integration of Left- and Right-Brain Pathways

A balance needs to be struck between the extreme polarities of creative vs. structured and repetitive approaches, individualization vs. fidelity to manuals, flexibility vs. rigidity, unconscious vs. conscious, emotions vs. cognitions, and RH vs. LH. Radical adherence to either polarity is less effective. At one polarity, fidelity to a structured, rigid, conscious, LH-activating manualized treatment would lack the flexibility and individualization necessary to establish a strong counseling relationship. At the other extreme, fidelity to a purely spontaneous, flexible, unconscious and RH-activating individualized approach would result in the impossibility of research evidence and thus be unproven. This has been a criticism of some theoretical approaches, such as psychoanalysis (Modell, 2012). Counselors can avoid rigidly following treatment manuals, and avoid completely spontaneous approaches that lack research evidence. According to emerging evidence from neuroscience, an integrated approach to client care seems necessary for effective counseling practice (Schore, 2012). The RH and LH seem equally important to human functioning and survival. These often function in tandem with one another. For example, both hemispheres are integral to problem solving; the RH generates solutions, while the LH decides on a single solution to best fit a problem (Cozolino, 2010).

Conclusion

Counseling effectiveness requires the integration of both right- and left-brain processing. Effective counseling is determined not only by what the counselor does or says; it is determined also by the quality of the counselor’s interaction with the client (Bromberg, 2006). In a two-person relational system, the interaction between counselor and client is at the core of effective counseling. The neuroscience literature suggests that hemispheric processing for both counselor and client is bidirectional. The counselor’s RH-to-RH attunement to the client’s subjective experience in the here-and-now encounter of the counseling room informs unconscious intuition and creativity for both counselor and client.

The counselor develops an implicit understanding of the client’s inner world and generates clinical intuitions that guide the counselor’s decision making. The client is provided with a RH-to-RH holding environment from which deep emotions and sectioned-off past experiences can be explored, and creativity is sparked by the need to respond to the uniqueness of the counseling environment. In cases when clients seem to benefit from interventions that target LH processing, the counselor’s often intuitive and unconscious adjustment is a result of the RH-to-RH interaction between counselor and client. Integrating LH interventions may provide a helpful structure to address client problems and facilitate RH processing when the counselor and client both expect change to occur and demonstrate belief in the chosen intervention, which further strengthens the therapeutic bond (Frank & Frank, 1991).

Prior to incorporating a manualized protocol, counselors can therefore establish rapport and attend to the therapeutic alliance and counseling relationship. This attention to RH processing provides a foundation from which the structure of a LH-activating, manualized treatment can be provided, thus mitigating potential ruptures to the therapeutic relationship that occur when counselors abruptly or rigidly apply treatment manuals in a rote fashion. In this manner, both LH and RH processing is enhanced, which is crucial to successful counseling outcomes.

Taking such an approach would integrate the left and right brain in counselor practice. By incorporating research evidence from neuroscience, counselors have a new model for research-informed counseling practice that fits the historical lineage of prizing the counseling relationship as the core ingredient in therapeutic change. While it is not easy to value both structure and spontaneity, or uniformity and individuality, achieving this balance will result in practice behaviors that are more commensurate with the counseling profession’s values and identity.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The author reported no conflict of interest or funding contributions for the development of this manuscript.

References

Ackerman, S. J., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2001). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques negatively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy, 38, 171–185. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.38.2.171

American Counseling Association. (2005). ACA code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. The American Psychologist, 61, 271–285.

Asari, T., Konishi, S., Jimura, K., Chikazoe, J., Nakamura, N., & Miyashita, Y. (2008). Right temporopolar activation associated with unique perception. NeuroImage, 41, 145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.01.002

Carey, B. (2004, June 8). Pills or talk? If you’re confused, no wonder. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2004/06/08/health/pills-or-talk-if-you-re-confused-no-wonder.html?pagewanted=2

Becker, C. B., Stice, E., Shaw, H., & Woda, S. (2009). Use of empirically supported interventions for psychopathology: Can the participatory approach move us beyond the research-to-practice gap? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.02.007

Benowitz, L. I., Bear, D. M., Rosenthal, R., Mesulam, M-M., Zaidel, E., & Sperry, R. W. (1983). Hemispheric specialization in nonverbal communication. Cortex, 19, 5–11.

Bernal, G., & Scharró-del-Rio, M. R. (2001). Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328

Bohart, A. C., & Tallman, K. (2010). Clients: The neglected common factor of psychotherapy. In B. L. Duncan, S. D. Miller, B. E. Wampold, & M. A. Hubble (Eds.), The heart & soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bollas, C. (1987). The shadow of the object: Psychoanalysis of the unthought known. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Bolte, A., & Goschke, T. (2005). On the speed of intuition: Intuitive judgments of semantic coherence under different response deadlines. Memory & Cognition, 33, 1248–1255. doi: 10.3758/BF03193226

Bowlby, J. (1991, Autumn). The role of the psychotherapist’s personal resources in the therapeutic situation. Tavistock Gazette.

Bromberg, P. M. (2006). Awakening the dreamer: Clinical journeys. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

Burgoon, J. K. (1985). Nonverbal signals. In M. L. Knapp & C. R. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal communication (pp. 344–390). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chambless, D. L. (1999). Empirically supported treatments—What now? Applied Preventative Psychology, 8, 281–284. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80043-5

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. 2009 Standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org

Cozolino, L. (2010). The neuroscience of psychotherapy: Healing the social brain (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Norton.

Duncan, B. L., Miller, S. D., Wampold, B. E,. & Hubble, M. A. (Eds.). (2010). The heart and soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Erford, B. T. (2012, September). Where’s the beef?! Counseling Today, 55(3), 5.

Field, T. A., Farnsworth, E. B., & Nielsen, S. K. (2011). Do counselors use evidenced-based treatments? Results from a national pilot survey. Unpublished manuscript.

Frank, J. D., & Frank, J. B. (1991). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press.

Grabner, R. H., Fink, A., & Neubauer, A. C. (2007). Brain correlates of self-related originality of ideas: Evidence from event-related power and phase-locking changes in the EEG. Behavioral Neuroscience, 121, 224–230. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.224

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: The new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Keenan, J. P., Rubio, J., Racioppi, C., Johnson, A., & Barnacz, A. (2005). The right hemisphere and the dark side of consciousness. Cortex, 41, 695–704. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70286-7

Kuchinke, L., Jacobs, A. M., Võ, M. L.-H., Conrad, M., Grubich, C., & Herrmann, M. (2006). Modulation of prefrontal cortex activation by emotional words in recognition memory. NeuroReport, 17, 1037–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000221838.27879.fe

La Roche, M. J., & Christopher, M. S. (2009). Changing paradigms from empirically supported treatment to evidence-based practice: A cultural perspective. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 396–402. doi: 10.1037/a0015240

Lieberman, M. D. (2000). Intuition: A social neuroscience approach. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 109–137. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.109

MacNeilage, P. F., Rogers, L., & Vallortigara, G. (2009, June). Origins of the left and right brain. Scientific American, 301, 160–167.

Magnavita, J. J. (2006). In search of the unifying principles of psychotherapy: Conceptual, empirical, and clinical convergence. American Psychologist, 61, 882–892. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.882

McGilchrist, I. (2009). The master and his emissary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Modell, A. H. (2012). Science confirms psychoanalytic theory: Commentary on Howard Shrevin’s paper. Psychoanalytic Review, 99, 511–551.

National Board of Certified Counselors. (2000). Gracefully aging at NBCC. The National Certified Counselor, 17(1), 1–2.

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). Evidence-based therapy relationships: Research conclusions and clinical practices. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 98-102. doi: 10.1037/a0022161

Orlinsky, D. E., Ronnestad, M. H., & Willutzki, U. (2004). Fifty years of psychotherapy process-outcome research: Continuity and change. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Raz, A. (2004). Anatomy of attentional networks. Anatomical Records, 281B, 21–36.

Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovolt, T. M. (2003). The journey of the counselor and therapist: Research findings and perspectives on professional development. Journal of Career Development, 30(1), 5–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1025173508081

Schore, A. N. (2012). The science of the art of psychotherapy. New York, NY: Norton.

Siegle, G. J., Steinhauer, S. R., Friedman, E. S., Thompson, W. S., & Thase, M. E. (2011). Remission prognosis for cognitive therapy for recurrent depression using the pupil: Utility and neural correlates. Biological Psychiatry, 69, 726–733.

Stern, D. N. (2004). The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. New York: Norton.

Stoltenberg, C. D., McNeill, B. W., & Delworth, U. (1998). IDM: An integrated developmental model for supervising counselors and therapists. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.