Sep 7, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 3

E. Heather Thompson, Melodie H. Frick, Shannon Trice-Black

Counselors-in-training face the challenges of balancing academic, professional, and personal obligations. Many counselors-in-training, however, report a lack of instruction regarding personal wellness and prevention of personal counselor burnout. The present study used CQR methodology with 14 counseling graduate students to investigate counselor-in-training perceptions of self-care, burnout, and supervision practices related to promoting counselor resilience. The majority of participants in this study perceived that they experienced some degree of burnout in their experiences as counselors-in-training. Findings from this study highlight the importance of the role of supervision in promoting resilience as a protective factor against burnout among counselors-in-training and provide information for counselor supervisors about wellness and burnout prevention within supervision practice

Keywords: counselors-in-training, wellness, burnout, supervision, resilience

Professional counselors, due to often overwhelming needs of clients and heavy caseloads, are at high risk for burnout. Research indicates that burnout among mental health practitioners is a common phenomenon (Jenaro, Flores, & Arias, 2007). Burnout is often experienced as “a state of physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion caused by long-term involvement in emotionally demanding situations” (Gilliland & James, 2001, p. 610). Self-care and recognition of burnout symptoms are necessary for counselors to effectively care for their clients as well as themselves. Counselors struggling with burnout can experience diminished morale, job dissatisfaction (Koeske & Kelly, 1995), negative self-concept, and loss of concern for clients (Rosenberg & Pace, 2006). Clients working with counselors experiencing burnout are at serious risk, as they may not receive proper care and attention to often severe and complicated problems.

The potential hazards for counselor distress in practicum and internship are many. Counselors-in-training often begin their professional journeys with a certain degree of idealism and unrealistic expectations about their roles. Many assume that hard work and efforts will translate to meaningful work with clients who are eager to change and who are appreciative of the counselor’s efforts (Leiter, 1991). However, clients often have complex problems that are not always easily rectified and which contribute to diminished job-related self-efficacy for beginning counselors (Jenaro et al., 2007). In addition, counselor trainees often experience difficulties as they balance their own personal growth as counselors while working with clients with immense struggles and needs (Skovholt, 2001). Furthermore, elusive measures for success in counseling can undermine a new counselor’s sense of professional competence (Kestnbaum, 1984; Skovholt, Grier, & Hanson, 2001). Client progress is often difficult to concretely monitor and define. The “readiness gap,” or the lack of reciprocity of attentiveness, giving, and responsibility between the counselor-in-training and the client, are an additional job-related stressor that may increase the likelihood of burnout (Kestnbaum, 1984; Skovholt et al., 2001; Truchot, Keirsebilck, & Meyer, 2000).

Counselors-in-training are exposed to emotionally demanding stories (Canfield, 2005) and situations which may come as a surprise to them and challenge their ideas about humanity. The emotional demands of counseling entail “constant empathy and one-way caring” (Skovholt et al., 2001, p. 170) which may further drain a counselor’s reservoir of resilience. Yet, mental health practitioners have a tendency to present themselves as caregivers who are less vulnerable to emotional distress, thereby hindering their ability to focus on their own needs and concerns (Barnett, Baker, Elman, & Schoener, 2007; Sherman, 1996). Counselors who do not recognize and address their diminished capacity when stressed are likely to be operating with impaired professional competence, which violates ethical responsibilities to do no harm.

Counselor supervision is designed to facilitate the ethical, academic, personal, and professional development of counselors-in-training (CACREP, 2009). Bolstering counselor resilience in an effort to prevent burnout is one aspect of facilitating ethical, personal, and professional development. Supervisors who work closely with counselors-in-training during their practicum and internship can promote the hardiness and sustainability of counselors-in-training by helping them learn to self-assess in order to recognize personal needs and assert themselves accordingly. This may include learning to say “no” to the demands that exceed their capacity or learning to actively create and maintain rejuvenating relationships and interests outside of counseling (Skovholt et al., 2001). Supervisors also can teach and model self-care and positive coping strategies for stress, which may influence supervisees’ practice of self-care (Aten, Madson, Rice, & Chamberlain, 2008). In an effort to bolster counselor resilience, supervisors can facilitate counselor self-understanding about overextending oneself to prove professional competency to achieve a sense of self-worth (Rosenburg & Pace, 2006). Supervisors can help counselors-in-training come to terms with the need for immediate positive reinforcement related to work or employment, which is limited in the counseling profession as change rarely occurs quickly (Skovholt et al., 2001). Counselor resiliency also may be bolstered by helping counselors-in-training establish realistic measures of success and focus on the aspects of counseling that they can control such as their knowledge and ability to create strong therapeutic alliances rather than client outcomes. In sum, distressing issues in counseling, warning signs of burnout, and coping strategies for dealing with stress should be discussed and the seeds of self-care should be planted so they may grow and hopefully sustain counselors-in-training over the course of their careers.

Method

The purpose of this exploratory study was to investigate counselor-in-training perceptions of self-care, burnout, and supervision practices related to promoting counselor resilience. The primary research questions that guided this qualitative study included: (a) What are master’s-level counselors-in-training’s perceptions of counselor burnout? (b) What are the perceptions of self-care among master’s-level counselors-in-training? (c) What, if anything, have master’s-level counselors-in-training learned about counselor burnout in their supervision experiences? And (d) what, if anything, have master’s level counselors-in-training learned about self-care in their supervision experiences?

The consensual qualitative research method (CQR) was used to explore the supervision experiences of master’s-level counselors-in-training. CQR works from a constructivist-post-positivist paradigm that uses open-ended semi-structured interviews to collect data from individuals, and reaches consensus on domains, core ideas, and cross-analyses by using a research team and an external auditor (Hill, Knox, Thompson, Williams, Hess, & Ladany, 2005; Ponterotto, 2005). Using the CQR method, the research team examined commonalities and arrived at a consensus of themes within and across participants’ descriptions of the promotion of self-care and burnout prevention within their supervision experiences (Hill et al., 2005; Hill, Thompson, & Nutt Williams, 1997).

Participants

Interviewees. CQR methodologists recommend a sample size of 8–15 participants (Hill et al., 2005). The participants in this sample included 14 individuals; 13 females and 1 male, who were graduate students in master’s-level counseling programs and enrolled in practicum or internship courses. The participants attended one of three universities in the United States (one in the Midwest and two in the Southeast). The sample consisted of 10 participants in school counseling programs and 4 participants in clinical mental health counseling programs. Thirteen participants identified as Caucasian, and one participant identified as Hispanic. The ages of participants ranged from 24 to 52 years of age (mean = 28).

Researchers. An informed understanding of the researchers’ attempt to make meaning of participant narratives about supervision, counselor burnout, and self-care necessitates a discussion of potential biases. This research team consisted of three Caucasian female faculty members from three different graduate-level counseling programs. All three researchers are proficient in supervision practices and passionate about facilitating counselor growth and development through supervision. All members of the research team facilitate individual and group supervision for counselors-in-training in graduate programs. The three researchers adhere to varying degrees of humanistic, feminist, and constructivist theoretical leanings. All members of the research team believe that supervision is an appropriate venue for bolstering both personal and professional protective factors that may serve as buffers against counselor burnout. It also is worth noting that the three members of the research team believed they had experienced varying degrees of burnout over the course of their careers. The researchers acknowledge these shared biases and attempted to maintain objectivity with an awareness of their personal experiences with burnout, approaches to supervision, and beliefs regarding the importance of addressing protective factors, wellness and burnout prevention in supervision. This study also was influenced by an external auditor who is a former counselor educator with more than 20 years of experience in qualitative research methods and supervision practice. As colleagues in the field of counselor education and supervision, the research team and the auditor were able to openly and respectfully discuss their differing perspectives throughout the data analysis process, which permitted them to arrive at consensus without being stifled by power struggles.

Procedures for Data Collection

Criterion sampling was used to select participants in an intentional manner to understand specified counseling students’ experiences in supervision. Criteria for participation in this study included enrollment as a graduate student in a master’s-level counseling program and completion of a practicum experience or participation in a counseling internship in a school or mental health counseling agency. Researchers disseminated information about this study by email to master’s-level students in counseling programs at three different universities. Interested students were instructed to contact, by email or phone, a designated member of the research team, who was not a faculty member at their university. All participants were provided with an oral explanation of informed consent and all participants signed the informed consent documents. All procedures followed those established by the Institutional Review Board of the three universities associated with this study.

Within the research team, researchers were designated to conduct all communication, contact, and interviews with participants not affiliated with their respective universities, in order to foster a confidential and non-coercive environment for the participants. Interviews were conducted on one occasion, in person or via telephone, in a semi-structured format. Participants in both face-to-face and telephone interviews were invited to respond to questions from the standard interview protocol (see Appendix A) about their experiences and perceptions of supervision practices that addressed counselor self-care and burnout prevention. Participants were encouraged to elaborate on their perceptions and experiences in order to foster the emergence of a rich and thorough understanding. The transferability of this study was promoted by the rich, thick descriptions provided by an in-depth look at the experiences and perceptions of this sample of counselors-in-training. Interviews lasted approximately 50–70 minutes. The interview protocol was generated after a thorough review of the literature and lengthy discussions about researcher experiences as a supervisee and a supervisor. Follow-up surveys (see Appendix B) were administered electronically to participants six weeks after the interview to capture additional thoughts and experiences of the participants.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim for data analysis. Transcripts were checked for accuracy by comparing them to the audio-recordings after the transcription process. Participant names were changed to pseudonyms to protect participant anonymity. Participants’ real names and contact information were only used for scheduling purposes. Information linking participants to their pseudonyms was not kept.

Coding of domains. Prior to beginning the data analysis process, researchers generated a general list of broad domain codes based on the interview protocol, a thorough understanding of the extant literature, and a review of the transcripts. Once consensus was achieved, each researcher independently coded blocks of data into each domain code for seven of the 14 cases. Next, as a team, the researchers worked together to generate consensus on the domain codes for the seven cases. The remaining cases were analyzed by pairs of the researchers. The third team member reviewed the work of the pair who generated the domain coding for the remaining seven cases. Throughout the coding process, domains were modified to best capture the data.

Abstracting the core ideas within each domain. Each researcher worked independently to capture the core idea for each domain by re-examining each transcript. Core ideas consisted of concise statements of the data that illuminated the essence of the participant’s expressed perspectives and experiences. As a group, the researchers discussed the wording of core ideas for each case until consensus was achieved.

Cross analysis. The researchers worked independently to identify commonalities of core ideas within domains across cases. Next, as a group, the research team worked to find consensus on the identified categories across cases. Aggregated core ideas were placed into categories and frequency labels were applied to indicate how general, typical, or variant the results were across cases. General frequencies refer to findings that are true for all but one of the cases (Hill et al., 2005). Typical frequencies refer to findings that are present in more than half of the cases. Variant frequencies refer to finding in at least two cases, but less than half.

Audit. An external auditor was invited to question the data analysis process and conclusions. She was not actively engaged in the conceptualization and implementation of this study, which gave the research team the benefit of having an objective perspective. The external auditor reviewed and offered suggestions about the generation of domains and core ideas, and the cross-case categories. Most feedback was given in writing. At times, feedback was discussed via telephone. The research team reviewed all auditor comments, looked for evidence supporting the suggested change, and made adjustments based on team member consensus.

Stability check. For the purpose of determining consistency, two of the 14 transcripts were randomly selected and set aside for cross-case analysis until after the remaining 12 transcripts were analyzed. This process indicated no significant changes in core domains and categories, which suggested consistency among the findings.

Results

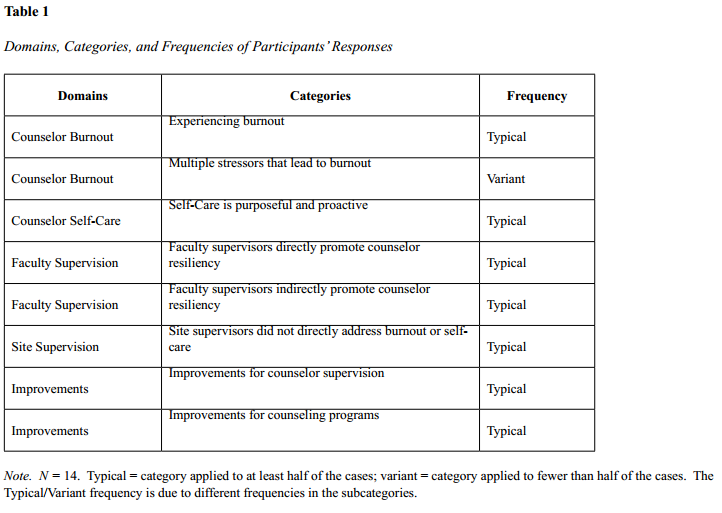

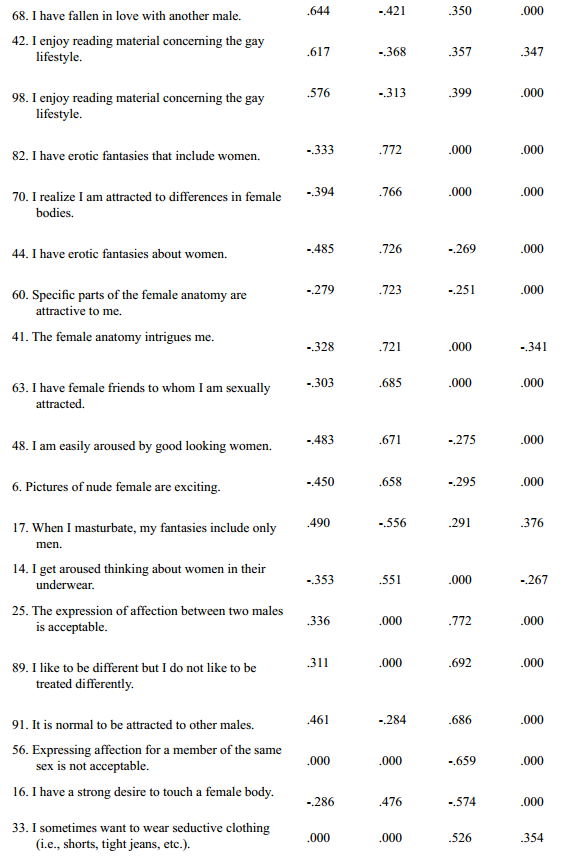

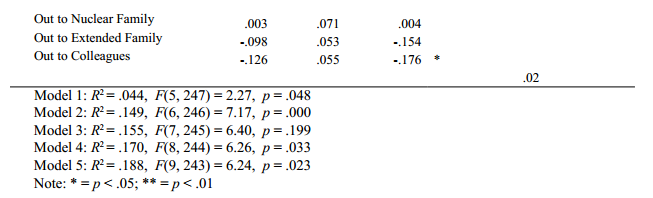

A final consensus identified five domains: counselor burnout, counselor self-care, faculty supervision, site supervision, and improvements (see Table 1). Cross-case categories and subcategories were developed to capture the core ideas. Following CQR procedures (Hill et al., 1997, 2005), a general category represented all or all but one of the cases (n = 13–14); a typical category represented at least half of the cases (n = 7–12); and a variant category represented less than half but more than two of the cases (n = 3 – 6). Categories with fewer than three cases were excluded from further analysis. General categories were not identified from the data.

Counselor Burnout

Experiencing burnout. Most participants reported knowledge of or having experiences with burnout. Participants identified stressors leading to burnout as a loss of enthusiasm and compassion, the struggle to balance school, work, and personal responsibilities and relationships, and difficulty delineating and separating personal and professional boundaries.

Participants described counselor burnout as no longer having compassion or enthusiasm for counseling clients. One participant defined counselor burnout as, “it seems routine or [counselors] feel like they’ve dealt with so many situations over time that they’re just kind of losing some compassion for the field or the profession.” Another participant described counselor burnout as no longer seeing the unique qualities of individuals seen in counseling:

I wouldn’t see [clients] as individuals anymore…and that’s where I get so much of it coming at me, or so many clients coming at me, that they’re no longer an individual they’re just someone that’s sitting in front of me, and when they leave they write me a check….they are not people anymore, they’re clients.

Participants often discussed a continual struggle to balance personal and professional responsibilities. One participant described burnout as foregoing pleasurable activities to focus on work-related tasks:

I can tell when I am starting to get burned out when I am focusing so much on those things that I forgo all of those things that are fun for me. So I am not working out anymore, I am not reading for fun, and I am putting off hanging out with my friends because of my school work. There’s school work that maybe doesn’t have to get done at that moment, but if I don’t work on it I’m going to be thinking about it and not having fun.

Another participant described burnout as having a hard time balancing professional and personal responsibilities stating, “I think I don’t look forward to…working with…people. I’m just kind of glad when they don’t show up. And this kind of sense that I’m losing the battle to keep things in balance.”

Boundary issues were commonly cited by participants. Several participants reported that they struggled to be assertive, set limits, maintain realistic expectations, and not assume personal responsibility for client outcomes. One participant described taking ownership of a client’s outcome and wanting to meet all the needs of her clients:

I believe part of it is internalizing the problem on myself, feeling responsible. Maybe loosing sight of my counseling skills and feeling responsible for the situation. Or feeling helpless. Also, in school counseling there tends to be a larger load of students. And this is frustrating to not meet all the needs that are out there.

Participants reported experiences with burnout and multiple stressors that lead to burnout. Participants defined counselor burnout as a loss of compassion for clients, diminished enthusiasm, difficulty maintaining a life-work balance, and struggles to maintain boundaries.

Counselor Self-Care

Self-care is purposeful and proactive. Participants were asked to describe self-care for counselors and reported that self-care requires purposeful efforts to set time aside to engage in activities outside of work that replenish energy and confidence. Most participants identified having and relying on supportive people, such as family, friends, and significant others to help them cope with stressors. Participants also identified healthy eating and individualized activities such as exercise, reading, meditation, and watching movies as important aspects of their self-care. One participant described self-care as:

Anything that can help you reenergize and refill that bucket that’s being dipped into every day. If that’s going for a walk in the park…so be it. If that’s going to Starbucks…go do it….Or something that makes you feel good about yourself, something that makes you feel confident, or making someone else feel confident….Whatever it is, something that makes you feel good about yourself and knowing that you’re doing what you need to be doing.

Participants reported that self-care requires proactive efforts to consult with supervisors and colleagues; one of the first steps is recognizing when one needs consultation. One participant explained:

I think in our program, [the faculty] were very good about letting us know that if you can’t handle something, refer out, consult. Consult was the theme. And then if you feel you really can’t handle it before you get in over your head, make sure you refer out to someone you feel is qualified.

Participants described self-care as individualized and intentional, and included activities and supportive people outside of school or work settings that replenished their energy levels. Participants also discussed the importance of identifying when counselor self-care is necessary and seeking consultation for difficult client situations.

Faculty Supervision

Faculty supervisors directly promote counselor resiliency. More than half of the participants reported that faculty supervisors directly initiated conversations about self-care. A participant explained, “Every week when we meet for practicum, [the faculty supervisor] is very adamant, ‘is everyone taking care of themselves, is anyone having trouble?’ She is very open to listening to any kind of self-care situation we might have.” Similarly, another participant stated, “Our professors have told us about the importance of self-care and they have tried to help us understand which situations are likely to cause us the most stress and fatigue.” One participant identified preventive measures discussed in supervision:

In supervision, counselor burnout is addressed from the perspective of prevention. We develop personal wellness plans, and discuss how well we live by them during supervision….Self-care is addressed in the same conversation as counselor burnout. In supervision, the mantra is good self-care is vital to avoiding burnout.

Faculty supervisors indirectly promote counselor resiliency. Participants also reported that faculty supervisors indirectly addressed counselor self-care by being flexible and supportive of participants’ efforts with clients. Participants repeatedly expressed appreciation for supervisors who processed cases and provided positive feedback and practical suggestions. One participant explained, “I know that [my supervisor] is advocating for me, on my side, and allowing me to vent, and listening and offering advice if I need it….giving me positive feedback in a very uncomfortable time.”

Further, participants stated they appreciated supervisors who actively created a safe space for personal exploration. One participant explained:

[Supervision] was really a place for us to explore all of ourselves, holistically. The forum existed for us for that purpose. [The supervisors] hold the space for us to explore whatever needs to be explored. That was the great part about internship with the professor I had. He sort of created the space, and we took it. It took him allowing it, and us stepping into the space.

Modeling self-care also is an indirect means of addressing counselor burnout and self-care. Half of the participants reported that their faculty supervisors modeled self-care. For example, faculty supervisors demonstrated boundaries with personal and professional obligations, practiced meditation, performed musically, and exercised. Conversely, participants reported that a few supervisors demonstrated a lack of personal self-care by working overtime, sacrificing time with their families for job obligations, and/or having poor diet and exercise habits.

Participants reported that faculty supervisors directly and indirectly addressed counselor burnout and self-care in supervision. Supervisors who intentionally checked in with the supervisees and used specific techniques such as wellness plans were seen as directly affecting the participants’ perspective on counselor self-care. Supervisors who were present and available, created safe environments for supervision, provided positive feedback and suggestions, and modeled self-care were seen as indirectly addressing counselor self-care. Both direct and indirect means of addressing counselor burnout and self-care were seen as influential by participants.

Site Supervision

Site supervisors did not directly address burnout or self-care. Participants reported that site supervisors rarely initiated conversations about counselor burnout or self-care. One participant reported that counselor burnout was not addressed and as a result she felt a lack of support from the supervisor:

[Site Supervisors] don’t ask about burnout though. Every time I’m bringing it up, the answers I’m getting are ‘well, when you’re in grad school you don’t get a life.’ You know, yeah, I get that, but that’s not really true, so I get a lot of those responses, ‘well, you know, welcome to the club.’

One participant stated that her site supervisor did not specifically address counselor burnout or self-care, stating “I think that is less addressed in a school setting than it is in the mental health field….I think that because we see such a small picture of our students, I think it is not as predominantly addressed.” Some participants, however, reported that their site supervisors indirectly addressed self-care by modeling positive behaviors. One participant stated:

[My site supervisor] has either structured her day or her life in such a way that no one cuts into that time unless she allows it. In that sense, she’s great at modeling what’s important…She just made a choice….She was protective. She made her priorities. Her family was a priority. Her walk was a priority, getting a little activity. Other things, house chores, may have fallen by the wayside. She had a good sense of priorities, I thought. That was good to watch.

In summary, participants reported that counselor burnout and self-care were not directly addressed in site supervision. Indeed, some participants felt a lack of support when feeling overwhelmed by counseling duties, and that school sites may address burnout and self-care less than at mental health sites. At best, self-care was indirectly modeled by site supervisors with positive coping mechanisms.

Improvements for Counselor Supervision and Training

Improvements for counselor supervision. More than half of the participants reported wanting more understanding and empathy from their supervisors. One participant complained:

A lot of my class mates have a lot on their plates, like I do, and our supervisors don’t have as much on their plate as we do. And it seems like they don’t quite get where we are coming from. They are not balancing all the things that we are balancing….a lot of the responses you get demonstrate their lack of understanding.

Another participant suggested:

I think just hearing what the person is saying. If the person is saying, I need a break, just the flexibility. Not to expect miracles, and just remember how it felt when you were in training. Just be relatable to the supervisees and try to understand what they are going through, and their point of view. You don’t have to lower your expectations to understand where we’re at…and to be honest about your expectations…flexible, honest, and understanding. If [supervisors] are those three things, it’ll be great.

Participants also suggested having counselor burnout and self-care more thoroughly addressed in supervision, including more discussions on balancing personal and professional responsibilities, roles, and stressors. One participant explained:

What would be really helpful when the semester first begins is one-on-one time that is direct about ‘how are you approaching this internship in balance with the rest of your life?’ ‘What are any issues that it would be worthwhile for me to know about?’ How sweet for the supervisor to see you as a whole person. And then to put out the invitation: the door’s always open.

Improvements for counselor training programs. More than half of the participants wanted a comprehensive and developmentally appropriate approach to self-care interwoven throughout their counselor training, with actual practice of self-care skills rather than “face talk.” One participant commented:

Acknowledge the reality that a graduate-level program is going to be a challenge, talking about that on the front end….[faculty] can’t just say you need to have self-care and expect [students] to be able to take that to the next level if we don’t learn it in a graduate program….how much better would it be for us to have learned how to manage that while we were in our program and gotten practice and feedback about that, and then that is so important of a skill to transfer and teach to our clients.

Most of the participants suggested the inclusion of concrete approaches to counselor self-care. Participants provided examples such as preparing students for their work as counselors-in-training by giving them an overview of program expectations at the beginning of their programs, and providing students with self-care strategies to deal with the added stressors of graduate school such as handling administrative duties during internship, searching for employment prior to graduation, and preparing for comprehensive exams.

Discussion

Findings from this study highlight the importance of the role of supervision in promoting resilience as a protective factor against burnout among counselors-in-training. The majority of participants in this study perceived that they experienced some degree of burnout in their experiences as counselors-in-training. Participants’ perceptions of experiencing burnout are a particularly meaningful finding because it indicates that these counselors-in-training see themselves as over-taxed during their education and training. If, during their master’s programs, counselors-in-training are creating professional identities based on cognitive schemas for being a counselor, then perhaps these counselors-in-training have developed schemas for counseling that include a loss of compassion for clients, diminished enthusiasm for counseling, a lopsided balance of personal and professional responsibilities, and struggles to maintain boundaries. Counselors-in-training should be aware of these potential pitfalls as these counselors-in-training reported experiencing symptoms of burnout which were rarely addressed in supervision.

In contrast to recent literature, which suggests that counselor burnout is related to overcommitment to client outcomes (Kestnbaum, 1984; Leiter, 1991; Shovholt et al., 2001), many counselor trainees in this study did not perceive that their supervisors directly addressed their degree of personal commitment to their clients’ success in counseling. Similarly, emotional exhaustion is commonly identified as a potential hazard for burnout (Barnett et al., 2007); yet, few participants believed that their supervisors directly inquired about the degree of emotional investment in their clients. Finally, elusive measures of success in counseling are often indicated as a potential factor for burnout (Kestnbaum, 1984; Skovholt, et al., 2001). The vast majority of participants interviewed for this study did not perceive that these elusive measures of success were addressed in their supervision experiences. Supervisors who are interested in thwarting counselor burnout early in the training experiences of counselors may want to consider incorporating conversations about overcommitment to client outcomes, emotional exhaustion, degree of emotional investment, and elusive measures of success into their supervision with counselors-in-training. In an effort to promote more resilient schemas and expectations for counseling work, supervisors can take an active role in helping counselors-in-training understand the importance of awareness and protective factors to protect against a lack of compassion, enthusiasm, life-work balance, and professional boundaries, similar to the way a pilot is aware that a plane crash is possible and therefore employs purposeful and effective methods of prevention and protection.

Participants in this study conceptualized self-care as purposeful behavioral efforts. Proactive behavioral choices such as reaching out to support others are ways that many counselors engage in self-care. However, self-care cannot be solely limited to engagement in specific behaviors. Self-care also should include discussions about cognitive, emotional, and spiritual coping skills. Supervisors can help counselors-in-training create a personal framework for finding meaning in their work in order to promote hardiness, resilience, and the potential for transformation (Carswell, 2011). Because of the nature of counseling, it is necessary for counselors to be open and have the courage to be transformed. Growth and transformation are often perceived as scary and something to be avoided. Yet, growth and transformation can be embraced and understood as part of each counselor’s unique professional and personal process. Supervisors can normalize and validate these experiences and help counselors-in-training narrate their inspirations and incorporate their personal, spiritual, and philosophical frameworks in their counseling. In addition, supervisors can directly address misperceptions about counseling, which often include: “I can fix the problem,” “I am responsible for client outcomes,” “Caring more will make it better,” and “My clients will always appreciate me” (Carswell, 2011). While these approaches to supervision are personal in nature, counselors-in-training in this study reported an appreciation for time spent discussing how the personal informs the professional. This finding is consistent with Bernard & Goodyear’s (1998) model of supervision which emphasizes personal development as an essential part of supervision. Models for personal development in counselor education programs have been proposed by many professionals in the field of counseling (Myers, 1991; Myers & Williard, 2003; Witmer & Granello, 2005).

Counselors-in-training in this study reported an appreciation for supervision experiences in which their supervisors provided direct feedback and positive reinforcement. Counselors-in-training often experience performance anxiety and self-doubt (Aten et al., 2008). In an effort to diminish counselor-in-training anxiety, supervisors may provide additional structure and feedback in the early stages of supervision. Once the counselor-in-training becomes more secure, the supervisor may facilitate a supervisory relationship that promotes supervisee autonomy and higher-level thinking.

The majority of participants interviewed reported a desire for supervisors to place a greater emphasis on life-work balance and learning to cope with stress. These findings suggest the importance of counselor supervisors examining their level of expressed empathy and emphasis on preventive, as well as remedial, measures to ameliorate symptoms and stressors that lead to counselor burnout. Participants expressed a need to be more informed about additional stressors in graduate school such as administrative tasks in internship, preparing for comprehensive exams, and how to search for employment. These findings suggest the need for counselor educators and supervisors to examine how they indoctrinate counselors-in-training into training programs in order to help provide realistic expectations of work and personal sacrifice during graduate school and in the counseling field. Moreover, counselor educators and supervisors should strive to provide ongoing discussions on self-care throughout the program, specifically when students in internship are experiencing expanding roles between school, site placement, and searching for future employment. As mental health professionals, counselor educators and supervisors may also struggle with their own issues of burnout; thus, attentiveness to self-care also is recommended for those who teach and supervise counselors in training.

Limitations

Findings from this study will benefit counselor educators, supervisors, and counselors-in-training; however, some limitations exist. One limitation is the lack of diversity in the sample of participants. The majority of the participants identified as Caucasian females, which is representative of the high number of enrolled females in the counseling programs approached for this study. The purpose for this study, however, was not to generalize to all counselor trainees’ experiences, but rather to shed light on how counselor perceptions of burnout and self-care are being addressed, or not, in counselor supervision.

Participant bias and recall is a second limitation of this study. Recall is affected by a participant’s ability to describe events and may be influenced by emotions or misinterpretations. This limitation was addressed by triangulating sources, including a follow-up questionnaire, reinforcing internal stability with researcher consensus on domains, core ideas, and categories, and by using an auditor to evaluate analysis and prevent researcher biases.

Conclusion

Counselors should be holders of hope for their clients, but one cannot give away what one does not possess (Corey, 2000). Counselors who lack enthusiasm for their work and compassion for their clients are not only missing a critical element of their therapeutic work, but also may cause harm to their clients. Counseling is challenging and can tax even the most “well” counselors. A lack of life-work balance and boundaries can add to the already stressful nature of being a counselor. Discussions in supervision about the potential for emotional exhaustion, the counselor-in-training’s degree of emotional investment in client outcomes, elusive measures of success in counseling, coping skills for managing stress, meaning-making and sources of inspiration, and personalized self-care activities are several ways supervisors can promote counselor resilience and sustainability. Supervisors should discuss the definitions of burnout, how burnout is different from stress, how to identify early signs of burnout, and how to address burnout symptoms in order to promote wellness and prevent burnout in counselors-in-training. Counselor educators and supervisors have the privilege and responsibility of teaching counselors-in-training how to take care of themselves in addition to their clients.

References

Aten, J. D., Madson, M. B., Rice, A., & Chamberlain, A. K. (2008). Postdisaster supervision strategies for promoting supervisee self-care: Lessons learned from hurricane Katrina. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 2(2), 75–82. doi:10.1037/1931-3918.2.2.75

Barnett, J. E., Baker, E. K., Elman, N. S., & Schoener, G. R. (2007). In pursuit of wellness: The self-care imperative. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(6), 603–612. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.603

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (1998). Fundamentals of clinical supervision (2nd ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) (2009). 2009 Standards. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/ doc/2009%20standards %20with20cover.pdf

Canfield, J. (2005). Secondary traumatization, burnout, and vicarious traumatization: A review of the literature as it relates to therapists who treat trauma. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 75(2), 81–102. doi:10.1300 J497v75n02_06

Carswell, K. (2011, March). Lecture on combating compassion fatigue: Strategies for the long haul. Counseling Department, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC.

Corey, G. (2000). Theory and practice of group counseling (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning.

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, S. J., Williams, E. N, Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 23(2), 196–205. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Nutt Williams, E. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25, 517–572. doi:10.1177/ 0011000097254001

Gilliland, B. E., & James, R. K. (2001). Crisis intervention strategies. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole-Thomson Learning.

Jenaro, C., Flores, N., & Arias, B. (2007). Burnout and coping in human service practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 80–87. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.1.80

Koeske, G. F., & Kelly, T. (1995). The impact of overinvolvement on burnout and job satisfaction. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 282–292. doi:10.1037/h0079622

Kestnbaum, J. D. (1984). Expectations for therapeutic growth: One factor in burnout. Social Casework: The Journal of Contemporary Social Work, 65, 374–377.

Leiter, M. (1991). The dream denied: Professional burnout and the constraints of human service organizations. Canadian Psychology, 32(4), 547–558. doi:10.1037/h0079040

Myers, J. E. (1991). Wellness as the paradigm for counseling and development. The possible future. Counselor Education and Supervision, 30, 183–193.

Myers, J. E., & Williard, K. (2003). Integrating spirituality into counselor preparation: A developmental, wellness approach. Counseling and Values, 47, 142–155.

Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 126–136. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196

Rosenberg, T., & Pace, M. (2006). Burnout among mental health professionals: Special considerations for the marriage and family therapist. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 32(1), 87–99. doi:10.1111/j.1752- 0606.2006.tb01590

Sherman, M. D. (1996). Distress and professional impairment due to mental health problems among psychotherapists. Clinical Psychology Review, 16, 299–315. doi:10.1016/0272- 7358(96)00016-5

Skovholt, T. M. (2001). The resilient practitioner: Burnout prevention and self-care strategies for counselors, therapists, teachers, and health professionals. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Skovolt, T. M., Grier, T. L., & Hanson, M. R. (2001). Career counseling for longevity: Self-care and burnout prevention strategies for counselor resilience. Journal of Career Development, 27(3), 167–176. doi:10.1177/089484530102700303

Truchot, D., Keirsebilck, L., & Meyer, S. (2000). Communal orientation may not buffer burnout. Psychological Reports, 86, 872–878. doi:10.2466/PR0.86.3.872-878

Witmer, J. M., & Granello, P. F. (2005). Wellness in counselor education and supervision. In J. E. Myers & T. J. Sweeney (Eds.), Counseling for wellness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 342–361). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

E. Heather Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Counseling Western Carolina University. Melodie H. Frick is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Counseling at West Texas A & M University. Shannon Trice-Black is an Assistant Professor at the College of William and Mary. Correspondence can be addressed to Shannon Trice-Black, College of William and Mary, School of Education, PO Box 8795, Williamsburg, VA, 23187-8795, stblack@wm.edu.

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

1. What do you know about counselor burnout or how would you define counselor burnout?

2. What do you think are possible causes of counselor burnout?

3. As counselors we often are overloaded with administrative duties which may include treatment planning, session notes, and working on treatment teams. What has this experience been like for you?

4. Counseling requires a tremendous amount of empathy which can be emotionally exhausting. What are your experiences with empathy and emotional exhaustion? Can you give a specific example?

5. How do you distinguish between feeling tired and the early signs of burnout?

6. As counselors, we sometimes become overcommitted to clients who are not as ready, motivated, or willing to engage in the counseling process. Not all of our clients will succeed in the way that we want them to. How do you feel when your clients don’t grow in the way you want them to? How has this issue been addressed in supervision?

7. What is your perception of how your supervisors have dealt with stress?

8. How has counselor burnout been addressed in supervision?

prompt: asked about, evaluated, provided reading materials, and how often

9. How have specific issues related to burnout been addressed in supervision such as: (a) over-commitment to clients who seem less motivated to change, (b) emotional exhaustion, and (c) elusive measures of success?

10. How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor burnout?

prompt: asked about, evaluated, provided reading materials, modeled by supervisor

11. What do you know about self-care or how would you define self-care for counselors?

12. What are examples of self-care, specifically ones that you use as counselors-in-training?

13. How has counselor self-care been addressed in supervision?

14. Sometimes we have to say “no.” How would you characterize your ability to say “no?” What have you learned in supervision about setting personal and professional boundaries?

15. What, if any, discussions have you had in supervision about your social, emotional, spiritual, and/or physical wellbeing? What is a specific example?

16. How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor self-care?

prompt: asked about, provided reading materials, modeled by supervisor

17. How could your overall counselor training be improved in addressing counselor burnout and counselor self-care?

Appendix B

Follow-Up Questionnaire

How would you describe counselor burnout?

How has counselor burnout been addressed in supervision?

How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor burnout?

How would you describe self-care for counselors?

How has counselor self-care been addressed in supervision?

How could supervision be improved in addressing counselor self-care?

How could your overall counselor training be improved in addressing counselor burnout and counselor self-care?

Sep 6, 2014 | Article, Volume 1 - Issue 3

Genevieve Weber-Gilmore, Sage Rose, Rebecca Rubinstein

Internalized homophobia, or the acceptance of society’s homophobic and antigay attitudes, has been shown to impact the coming out process for LGB individuals. The current study examined the relationship between levels of outness to family, friends and colleagues and internalized homophobia for 291 lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Results suggest internalized homophobia is a predictor of outness to friends, colleagues, and extended family, but not nuclear family. A discussion of these findings as well as implications for counselors are provided.

Keywords: internalized homophobia, “coming out,” lesbian, gay, bisexual

Lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals (LGB) have been shown to be one of the most stressed population groups in society (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007). Beyond dealing with daily stressors common with their heterosexual counterparts, LGB individuals experience unique stressors such as homophobia, societal discrimination and limited social and institutional supports due to their same-gender sexual orientations. Homophobia is defined as the anxiety, aversion, and discomfort that some individuals experience in response to being around, or thinking about LGB behavior or people (Davies, 1996; Spencer, & Patrick, 2009).

Homophobia is endorsed through the perpetuation of negative stereotypes about LGB behavior and people on both societal and individual levels, and the discrimination and prejudice of LGB people across the lifespan (Bobbe, 2002; Davies, 1996; Spencer & Patrick, 2009). Subtle forms of homophobia and discrimination such as the exclusion of LGB couples in the media and blatant acts of alienation experienced when individuals refuse to rent to LGB people are far too common in the lives of LGB individuals (Neisen, 1990; Smiley, 1997). Other examples of homophobia include unfair treatment by family, friends, and peers; loss of employment or lack of promotions; and observing/hearing people making anti-gay jokes (King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008; Rankin, Weber, Blumenfeld, & Frazer, 2010). These homophobic events greatly affect the lives of LGB individuals such that many LGB individuals hide their sexual orientation from others and feel shame and other negative feelings towards themselves (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT], 2001).

Higher levels of stress are common among LGB individuals who feel they have to hide their sexual orientation from others (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007) or have negative feelings towards themselves based on their same-gender sexual attractions (Weber, 2008). The acceptance of society’s homophobic and anti-gay attitudes about LGB sexual orientations is known as internalized homophobia. Low self-esteem and low self-acceptance; shame; guilt; depression and anxiety; feelings of inadequacy and rejection; verbal and physical abuse by family, partners, and/or peers; homelessness; prostitution; substance use and abuse; and suicide are some of the common feelings or behaviors that are associated with internalized homophobia (CSAT, 2001; Diamond & Wilsnack, 1978; Grossman, 1996; Lewis, Saghir, & Robins, 1982; Ross & Rosser, 1996; Saghir & Robins, 1973; Spencer, & Patrick, 2009; Stall & Wiley, 1988; Stein & Cabaj, 1996). According to Bobbe (2002), the negative feelings and behaviors associated with internalized homophobia can have a more painful and disruptive influence on the health of LGB individuals than external, overt forms of oppression such as prejudice and discrimination.

Homophobia and internalized homophobia have been shown to impact the coming out process for LGB individuals. “Coming out” is a shortened term for “coming out of the closet” (Hunter, 2007, p. 41). As LGB individuals begin to disclose their sexual orientation to others, or “come out,” they often experience a series of stages that include but are not limited to an initial awareness of being different, grieving, feelings of inner conflict, and an established sexual minority identity with long-term relationships. This is a developmental process that involves a person’s awareness and acknowledgement of same-gender oriented thoughts and feelings while accepting being LGB as a positive stage of being (Browning, Reynolds, & Dworkin, 1991; Kus, 1990; McGregor et al., 2001; Ridge, Plummer, & Peasley, 2006). The process of forming an LGB identity or “coming out” is a challenging process as it involves adopting a non-traditional sexual identity, restructuring one’s self-concept, and changing one’s relationship with society (Reynolds & Hanjorgiris, 2000; Ridge, Plummer, & Peasley, 2006).

Coming out for bisexual individuals is a “more ambiguous status” (Hunter, 2007, p. 53) as it is complicated by marginalization from both the straight and gay communities. This marginalization usually includes same-gender oriented friends urging bisexual individuals to adopt a gay lifestyle and heterosexually-oriented friends pressuring them to conform to heterosexual standards (Smiley, 1997). Although it is common for research on bisexual individuals to be lumped with lesbians and gay men (Hoang, Holloway, & Mendoza, 2011), Knous (2005) proposed a series of steps that individuals who identify as bisexual might take in disclosing and ultimately embracing their sexual identity. The first step is to be attracted or to participate in sexual activity with someone of either gender. The second step is to become labeled as bisexual either by themselves or by society. The third step is to be participatory in the bisexual community through personal or group pride. Bisexual individuals still experience stigma similar to their lesbian, gay, or heterosexual counterparts (Knous, 2005), and respond in similar ways: they might “pass” as either gay or straight, an act intended to hide one’s same-gender attractions (Herek, 1996); disclose their bisexual identity; or join support groups to fight the stigma (Knous, 2005).

Multiple researchers have described average chronological ages at which experiences related to coming out occur, which were summarized by Hunter (2007). Lesbians and bisexual women first experience awareness of same-gender attraction between the ages of ten and eleven years; gay and bisexual males between the ages of nine and thirteen years. Gay male youths on average experience their first sexual experiences a few years later between the ages of thirteen and sixteen years, while lesbian youths experiment around twenty years of age. First disclosures of sexual orientation happen between the ages of sixteen and nineteen for lesbian youths, and sixteen and twenty for gay male youths. Regardless of the age of disclosure, negative responses to being lesbian, gay, or bisexual still occur, and this “tempers the motivation of persons…in terms of making disclosures” (Hunter, 2007, p. 84). This may explain the three main patterns of sexual identity in individuals who are moving towards identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Braun, 2006). These patterns include consistently identifying as gay or lesbian, transitioning from bisexual to gay or lesbian, and consistently identifying as bisexual. Youths who were engaged in transitional identities continued to change their behavior and orientation to match their new identity. The process of acceptance of one’s sexual identity, committing to that identity, and integrating that identity into one’s life is something that does not end after adolescence, but continues into adulthood (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Braun, 2006).

The process of coming out could be a major source of stress for LGB individuals (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007). Some disclosures could cause harm in the lives of LGB individuals such as family crisis, dismissal from the household, loss of custody of children, loss of friends, or mistreatment in the workplace (Hunter, 2007; Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003). Yet, not coming out to others means LGB individuals must maintain personal, emotional, and social distance from those to whom they remain closeted in order to “protect the secrecy” of their “core identity” (Brown, 1988, p. 67).

A number of studies have explored the unique challenges associated with the coming out process for LGB individuals. A study by Flowers and Buston (2001) investigated “passing” as heterosexual, or assuming the identity of a heterosexual individual while hiding behaviors associated with an LGBT identity. In their study, Flowers and Buston examined the retrospective accounts of gay identity development for 20 gay men. Living a lie was identified as a common theme in their interviews such that many men continued to assume a heterosexual identity as a response to a non-accepting homophobic society. This lie was not something that was simply stated; rather, it had to be created and maintained “all the time” (p. 58, Flowers & Buston), and only temporarily eased the participants’ feelings of isolation and identity confusion (Flowers & Buston). Shapiro, Rios, & Stewart (2010) support the findings of Flowers and Buston. In this study that explored narrative accounts of sexual minority identity development among lesbians, cultural norms that failed to acknowledge the existence of non-normative sexual identities were identified and discussed. Such neglect of LGB identities required personal silence on the part of the respondents, which helped them avoid the negative consequences of coming out such as feelings of danger and discomfort as well as punishment.

Paul and Frieden (2008) examined the process of integration of gay identity and self-acceptance among gay men. Participants described societal homophobia and heterosexism as “powerful barriers” to self-acceptance, and validation and acceptance from others as helpful supports in the acceptance of themselves. Respondents indicated that they felt emotional pain or crisis when they began to develop a same-gender sexual identity and received negative messages about that identity. They feared that loved ones would not be accepting, and often denied that they were gay, both to themselves and to others.

A study by Rowen and Malcolm (2002) examined internalized homophobia and its relationship to sexual minority identity formation, self-esteem, and self-concept among 86 gay men. Results indicated that higher levels of internalized homophobia were associated in less developed gay male identities. In addition, gay men who felt more uncomfortable with their sexual orientations were more likely to experience guilt over their same-gender sexual behavior. Internalized homophobia also was found to be related to lower levels of self-esteem and self-concept in terms of physical appearance and emotional stability.

There are a diverse range of personal variables such as “personality characteristics, overall psychological health, religious beliefs, and negative or traumatic experiences regarding one’s sexual orientation” (Hunter, 2007, p. 94) that impact to whom LGB individuals disclose their same-gender sexual orientation. Some same-gender oriented individuals are closeted entirely and hide their sexual orientations from others for fear of their reactions (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007). Others will only come out to selected people (e.g., friends, family, colleagues, teachers, medical providers) rather than everyone at once. Several will come out completely and become very involved in the LGB community by attending LGB events and venues.

In general, disclosures are most often first made to friends of LGB people who are considered to be somewhat affirming of one’s same-gender sexual orientation (Hunter, 2007). According to Cain (1991), coming out to friends can bring two friends closer together, confirm an already close relationship, or cause a strain between previously close friends. Results from a study by D’Augelli and Hershberger (2002) revealed that 73% of lesbian and gay youths first told a friend about their same-gender sexual attractions. Other research suggested that bisexual men and women are also more likely to disclose to their friends than to family members and work colleagues (Hunter, 2007). These friends are usually across sexual identities and often with individuals who are heterosexual, and less with other bisexuals (Galupo, 2006).

Regardless of the outcome, the notion that disclosure to friends differs from disclosure to family members allows for LGB individuals to “select friends who are supportive or drop those unlikely to accept the revelation, something they cannot do in their parental or sibling relationships” (Cain, 1991, p. 349). LGB individuals do not always disclose their LGB sexual orientations to family members for fear of consequences such as “…anything from a dismissal of their feelings to an actual dismissal from the household” (Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001, p. 104). Disclosures to parents elicit much anxiety for LGB individuals as there are limited ways to predict how parents will respond (Hunter, 2007). Many LGB individuals fear losing familial support after disclosing to family members (Carpineto et. al, 2008; D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2005). According to Shapiro, Rios, & Stewart (2010), when LGB individuals have identified the family as a source of conflict, these individuals considered their parental figures to be unsupportive of their sexual identity. This conflict leads to an increase in tension within the family. According to Savin-Williams and Ream (2003), 90% of college men reported that coming out to their parents was a “somewhat” to “extremely” challenging event for them (p. 429).

Siblings have been described as more accepting of their LGB sibling’s disclosure, and if there is rejection it is usually less stressful than rejection by the parents (Cain, 1991). Lesbian wives do not often disclose to their husbands for fear of consequences (i.e., violence, custody battles), but men who come out as bisexual following their marriage to a woman tell her soon after he accepts his bisexual identity (Hunter, 2007). No data on gay men and their disclosure to their wives could be located. It also is not uncommon for LGB parents to keep their same-gender sexual orientations from their children for fear of losing custody or inflicting harm on their children (Hunter, 2007).

There are positives and negatives to coming out at work and to work colleagues (Hunter, 2007), and therefore there are varying levels of disclosure among LGB individuals. Research suggests that LGB individuals who are more open at work experience higher levels of job satisfaction and commitment to the workplace (Day & Shoenrade, 1997; Griffith & Hebl, 2002; King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008). Some LGB individuals may feel “honest, empowered and connected” after disclosure at work, and able to speak more freely about their personal lives and romantic relationships (Hunter, 2007, p. 127). Organizations that have written non-discrimination policies, are actively affirmative, and offer trainings that incorporate LGB issues usually impact whether lesbian and gay individuals come out in the workplace (Griffith & Hebl, 2002). It is unfortunate, however, that there is little legal protection for LGB individuals based on sexual orientation in most workplaces (Hunter, 2007). The possible harm (i.e., ridicule, ostracism, job loss) of disclosing at work without legal protection, and in some cases even with legal protection, causes many LGB individuals to stay closeted at work. Although keeping one’s LGB sexual orientation a secret might create fewer problems with regard to stigma, discrimination, and discreditability, living “a double life” can be personally and professionally “costly” (Hunter, 2007, p. 126). Hunter further summarized the limited professional literature on outness in the workplace and reported that more than two-thirds of lesbian and gay individuals think coming out in the workplace would create problems and challenges for them, while one-third believed disclosure would hurt their career progression (i.e., not being hired, not being promoted, not receiving personal or professional support). Fears of and personal experiences with harassment and heterosexism in the workplace also could negatively impact one’s psychological and physical well-being and thus one’s decision to disclose to work colleagues.

A major study based on the utilization of The National Lesbian Health Care Survey (NLHCS; Bradford, Ryan, & Rothblum, 1993) examined the degrees of outness and to whom disclosures were made for a national sample of 1,925 lesbians. The results of this study support the aforementioned identification of whom LGB individuals come out to more often as they move through the process of forming a sexual minority identity. Researchers found that although the majority of lesbians (88%) were out to all gay and lesbian individuals who they knew, much smaller numbers were out to all family members (27%), heterosexual friends (28%), and co-workers (17%). Furthermore, many participants reported not coming out to any family members (19%) or co-workers (29%). Correlations between degree of outness and fears as a lesbian were also analyzed and results showed a negative relationship such that lesbians who were less out to family, heterosexual friends, and co-workers had more fear of exposure as a lesbian. Correlations were strongest among outness to heterosexual friends and co-workers. No other studies that specifically examined the relationship between level of outness and internalized homophobia could be located. Therefore, this important relationship remains underexplored.

In summary, LGB individuals have been described as an at-risk group based on the high level of homophobia on both societal and individual levels. Such experiences with homophobia impact the way LGB individuals view themselves, particularly how they define their sexual minority identities which have been historically marginalized and stigmatized. Consequently, negative views of self result from the internalization of society’s negative attitudes towards LGB individuals. Internalized homophobia has been documented as a potential disruption to the coming out process as it impacts an LGB individual’s decision to be closeted completely, come out to selected individuals, or come out to all (Cabaj, 1997). Disclosure or non-disclosure to family, friends, and colleagues and how it is impacted by internalized homophobia warrants attention from researchers as it has significant implications in the lives of LGB individuals.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the present study was to gain a better understanding of the relationship between levels of outness to family, friends and colleagues and internalized homophobia. Conducting research on risk factors that negatively impact the coming out process, such as internalized homophobia, will generate knowledge that will help reduce the stress unique to LGB individuals. Such research also will increase the provision of quality and effective support to cope with stress for this historically underserved population group (Iwasaki & Ristock, 2007).

We hypothesized that internalized homophobia would predict whether one comes out to all family (nuclear and extended family), friends, and colleagues. Internalized homophobia and concerns about coming out contributes to an LGB individual’s reluctance to enter the ‘scene’ or culture which is related to their sexual identity (Ridge, Plummer, & Peasley, 2006). In fact, internalized homophobia has prevented some LGB individuals from never finding their true selves, creating a further disconnection from their true identities. Based on this finding as well as others, we propose that LGB individuals with high levels of internalized homophobia would be less likely to come out as LGB to all family (nuclear and extended family), friends and colleagues. If issues related to internalized homophobia, a well-documented risk factor for stress among LGB individuals, are addressed, improvement in the mental health and overall quality of life for LGB individuals can occur (Wagner et al., 1996).

Method

Participants

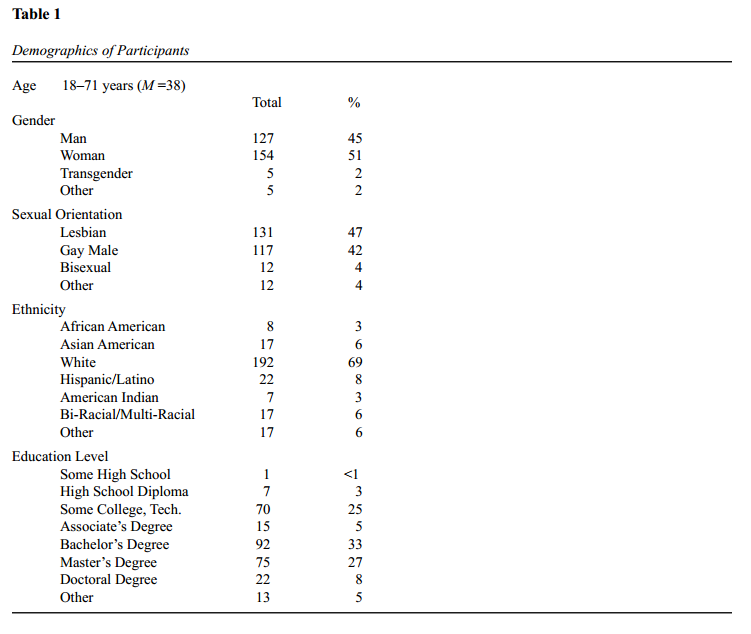

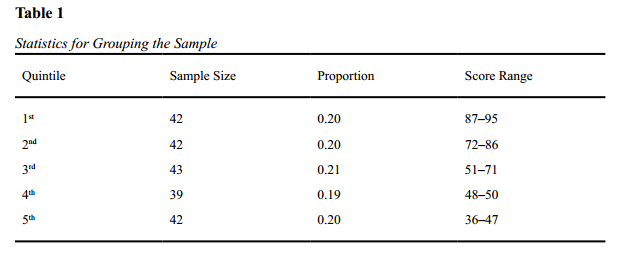

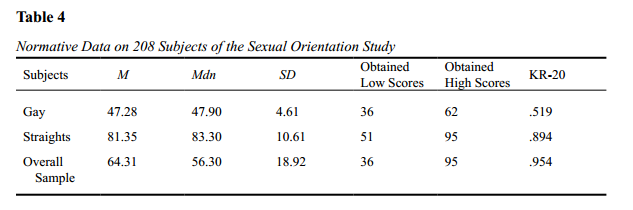

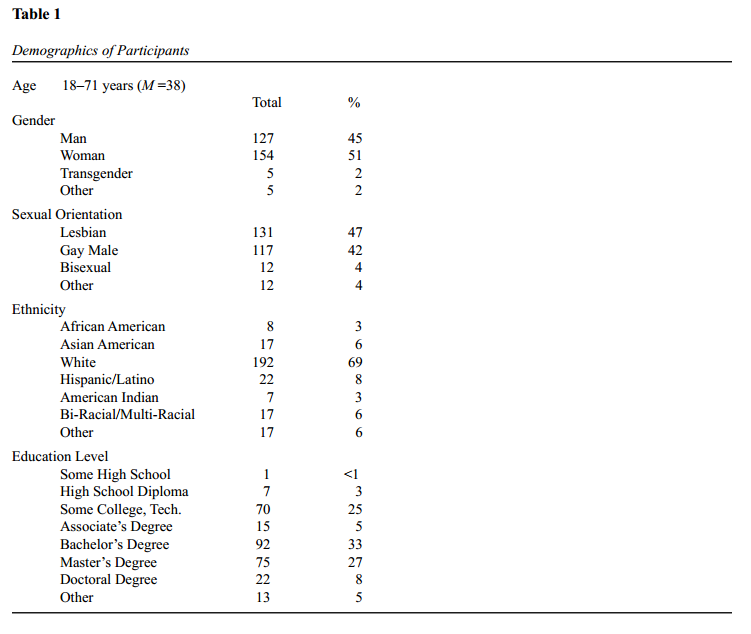

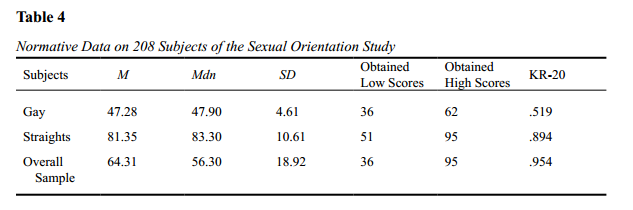

Two hundred ninety individuals between the ages of 18 and 71 responded to our study. Forty-seven percent (n = 131) of respondents identified as lesbian, 42% (n = 117) as gay, and 4% (n = 12) as bisexual. More than half of the respondents identified their gender identity as woman (51%, n = 154), 45% (n=127) as man, 2% (n = 5) as transgender, and 2% (n = 5) as “other.” Seventy-three percent (n = 204) had an associate’s degree or higher, and 69% (n=192) identified as White (see Table 1 for complete demographics). Due to the small number of transgender respondents, we did not examine their experiences by gender identity. We do recognize, however, the unique interaction between gender identity and sexual identity, and encourage future research in this area.

Materials

Levels of Outness. The questions used in this study that assessed level of outness of participants were adapted with permission from a survey developed by Rankin (2003). These questions are part of a larger campus climate survey that is used nationally to assess campus climate for community members. This set of questions showed high internal consistency (α = .80). Using a varimax rotation, items load as one factor and account for 65% of the variance.

Internalized Homophobia Scale (IHP; Martin & Dean, 1987). The Internalized Homophobia Scale is a 9-item measure adapted for self-report. Previous research has indicated that the self-administered version of the IHP scale has acceptable internal consistency and correlated as expected with relevant measures (Herek & Glunt, 1995). Items are administered with a 5-point response scale, ranging from disagree strongly to agree strongly. Reliability coefficients for this scale are typically higher for men (α = .83) then women (α = .71).

Procedure

An online survey was created through PsychData, a Web-based company that conducts Internet-based research in the social sciences. Participants were invited through email advertisements to general and multicultural LGBT list-servs. Personal networks also were utilized. Participants were made aware of the intentions of the survey and the topics they would encounter. Participation was anonymous and all respondents reviewed and gave informed consent before initiating the study. (Appropriate IRB approval was obtained).

Results

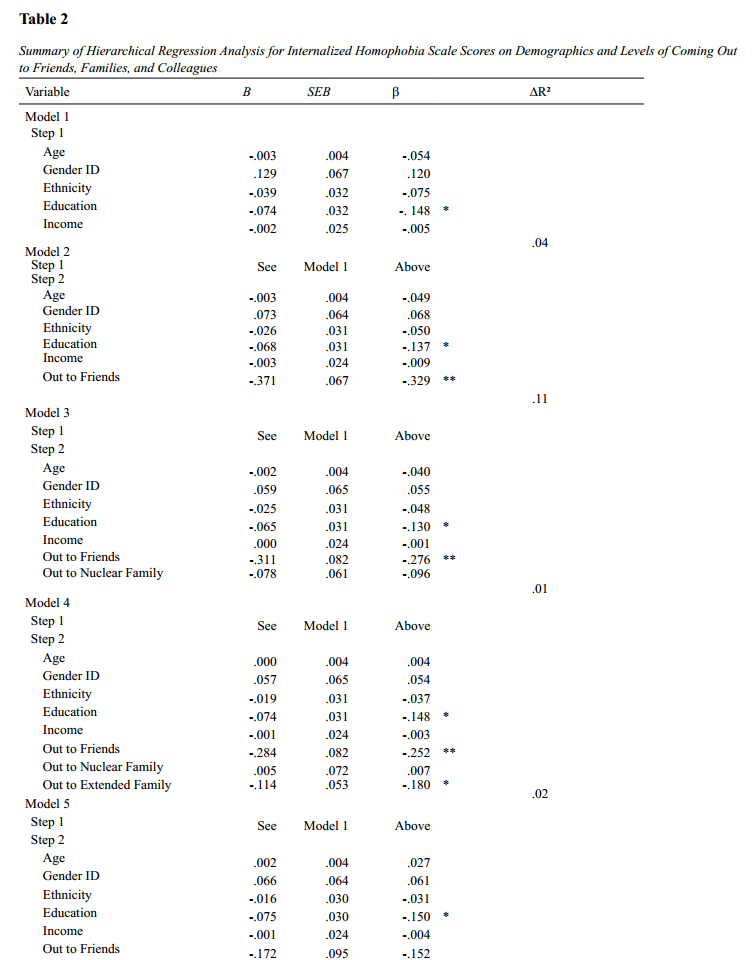

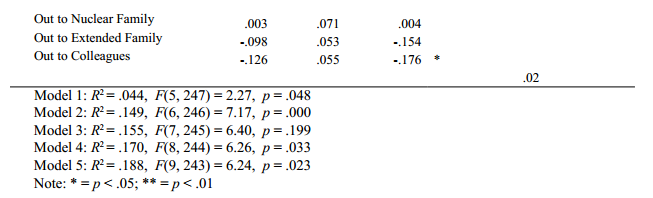

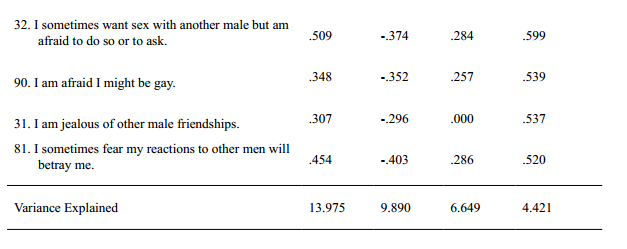

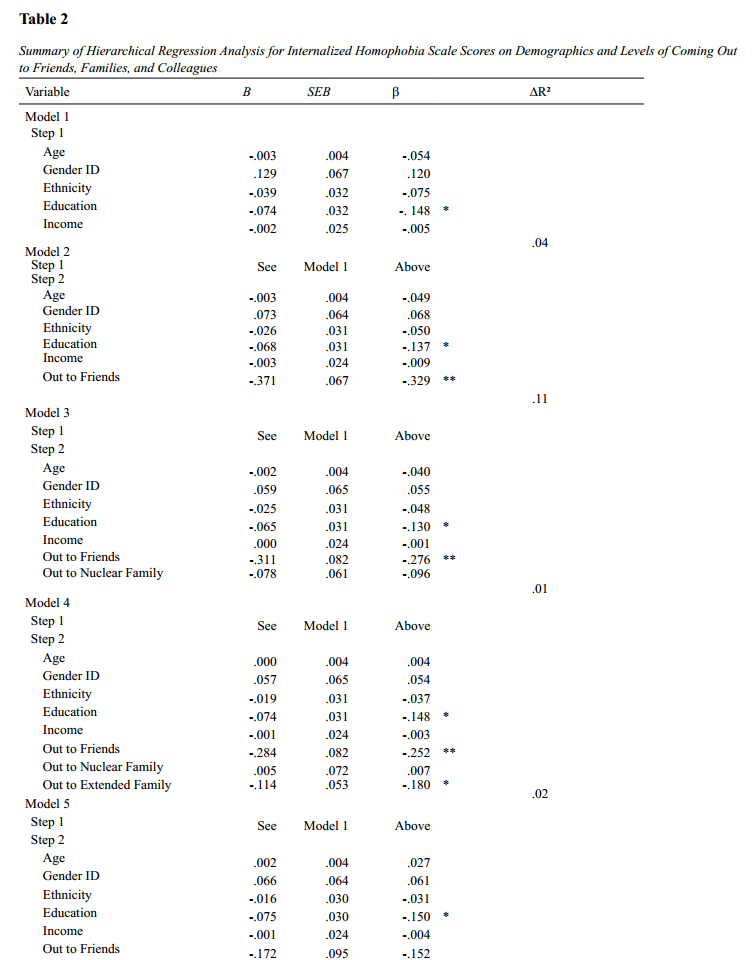

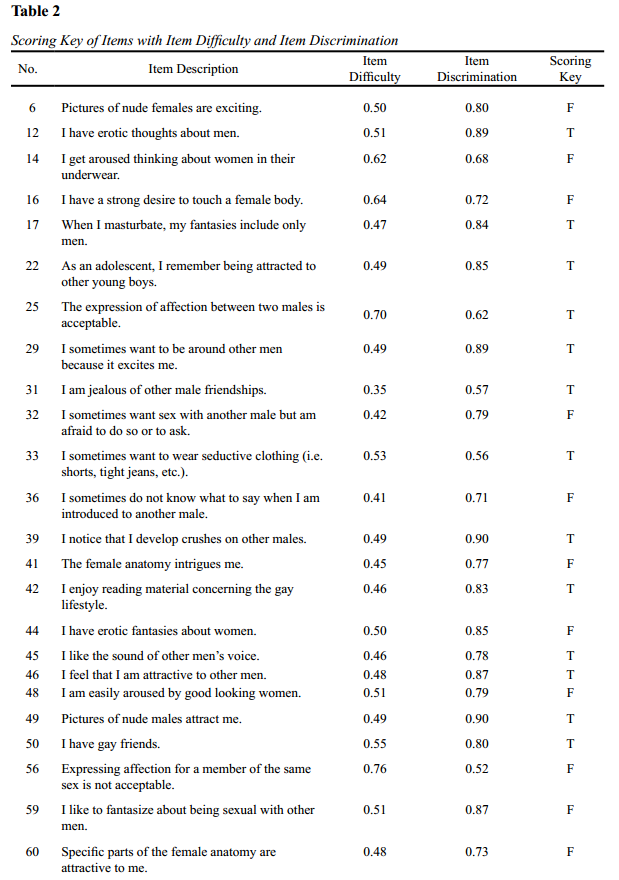

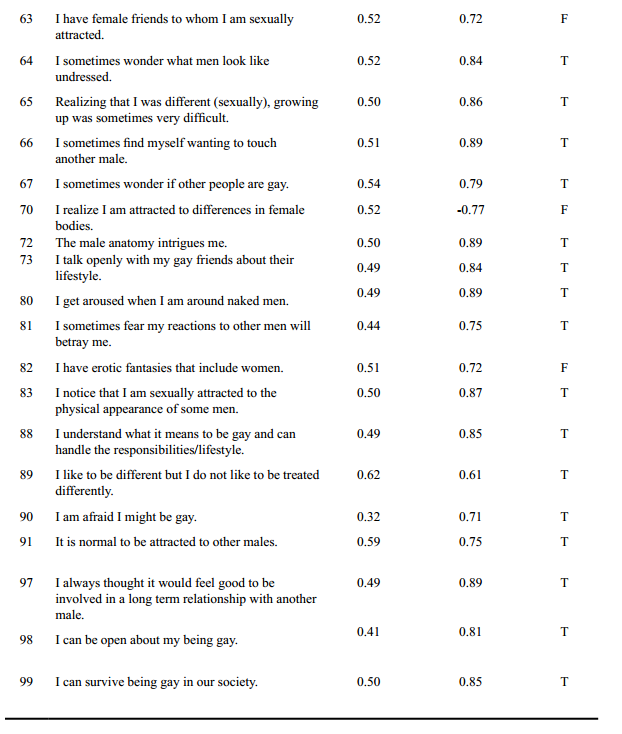

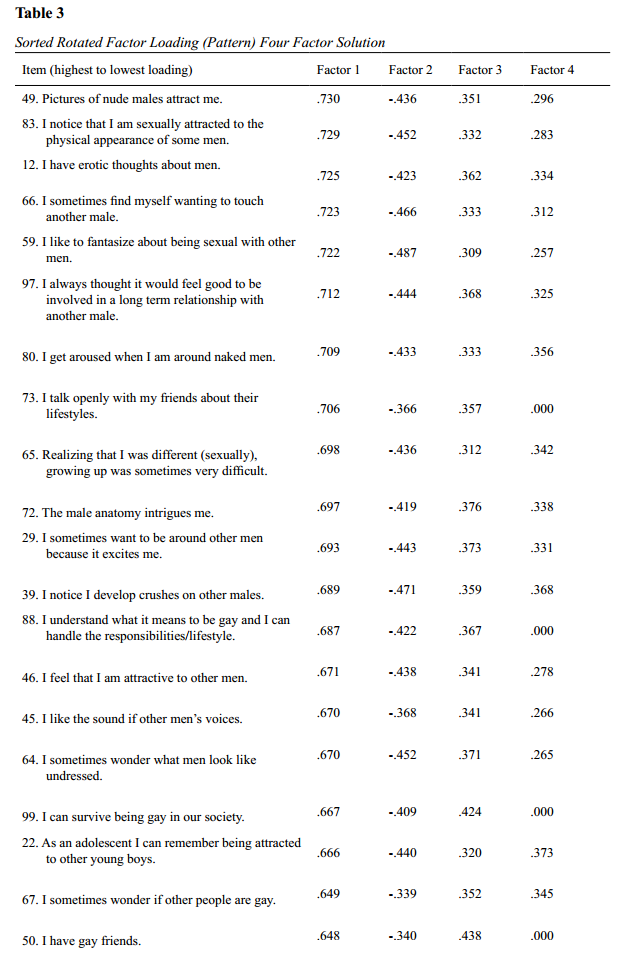

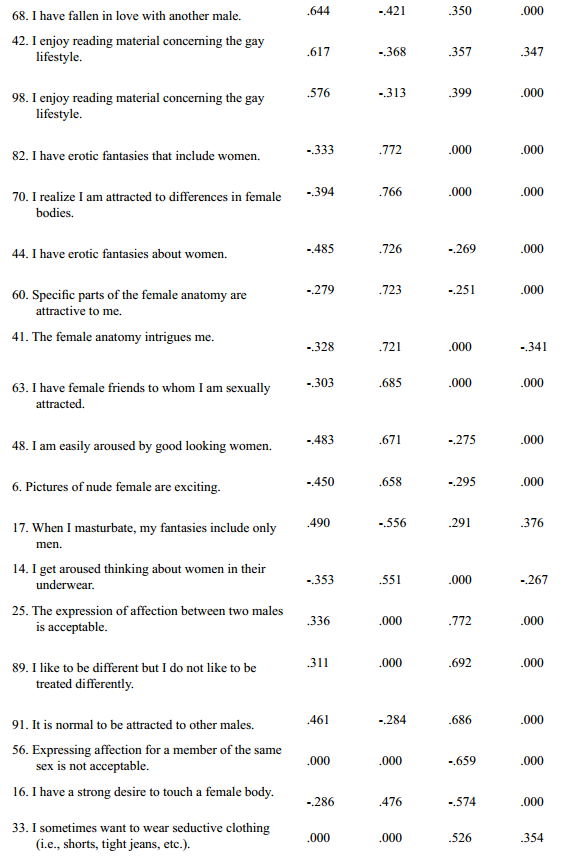

A set of regression procedures were conducted to examine how “coming out” to friends, family, and colleagues predicted scores on the Internalized Homophobia Scale (IHP). Table 2 shows the complete regression summaries. Model 1 regressed demographic variables: age, self-identified gender, ethnicity, education level and reported income. This model accounted for 4% of the overall variance with education level contributing most to the prediction of IHP scores (β = -.15, p < .05). This model was used in each of the following hierarchical models as a first step to control for demographics to examine the prediction value of each “coming out” variable.

Model 2 emerged as a significant model. Coming “out to friends” was added as a second step to the model and accounted for an additional 11% of the variance after controlling for demographics. According to the standardized regression coefficients, this variable provided a significant contribution to the prediction of IHP scores (see Table 2). Model 3 did not emerge as a significant model. By including coming “out to nuclear family” only an addition 1% of the total variance was accounted for. Within the third model, coming “out to friends” remained the largest contributor to the prediction of internalized homophobia (β = -.28, p < .05).

Model 4 and Model 5 emerged as significant models. In Model 4, the second step added coming “out to extended family” and contributed 2% to the total variance. Standardized regression coefficients indicated coming “out to friends” and “out to extended family members” were the strongest contributors to the model. By adding “out to colleagues” to the second step of the fifth model, an additional 2% of the variance was accounted for beyond demographics. “Out to colleagues” contributed the most to the predication of internalized homophobia beyond demographic differences, coming out to friends, coming out to nuclear family, and coming out to extended family (β = -.18, p < .05). Model 5 accounted for almost 19% of the total variance.

Discussion

The findings from our study suggest internalized homophobia impacts whether one is out to friends, colleagues, and extended family, but not to nuclear family. These findings are surprising as we hypothesized internalized homophobia would impact whether one is out to all family members (nuclear and extended), friends, and colleagues. Specifically, we hypothesized that higher internalized homophobia would lessen the likelihood that LGB individuals disclose as lesbian, gay, or bisexual to all family (nuclear and extended), friends, and colleagues. This assumption was based on the professional literature that underscored the fact that experiences in an anti-gay society can lead LGB individuals to internalize prejudicial messages and have negative views of self, and the potential consequences of coming out to family (family crisis), friends (disconnection and loss of friends), and work colleagues (dismissal and mistreatment; Hunter, 2007; Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003).

Education level also was a strong predictor of internalized homophobia for the sample in this study. Education level may be influential because individuals who are more “in the know” may accept that internalized homophobia is a barrier to self-acceptance and therefore an issue worth addressing and resolving. Further, coming out to friends and colleagues contributed strongly to internalized homophobia which may be a result of the experiences of LGB individuals in an anti-gay society and the possibility that friends and colleagues represent non-affirming members of our society. Therefore, the greater the discomfort with one’s same gender sexual identity, the less likely a LGB individual will come out to friends or co-workers for fear of negative consequences.

Although Hunter (2007) posited that LGB people most often come out to friends first, our study underscores a unique relationship between internalized homophobia and coming out to friends in that respondents with higher internalized homophobia were less out to friends. Findings from the National Lesbian Health Care Survey (NLHCS; Bradford, Ryan, & Rothblum, 1993) support this finding from our study. Correlations from the NLHCS suggest lesbians with higher internalized homophobia feared exposure as a lesbian to heterosexual friends. Furthermore, 88% of lesbians from the NLHCS were out to other LGB individuals, but only 28% were out to heterosexual friends. Perhaps respondents in our study who had higher internalized homophobia had similar fears regarding disclosure to heterosexual friends, particularly those who were non-affirming of LGB sexual identities. Furthermore, based on the results of our study and the professional literature, it is possible to assert that respondents from our study who had lower internalized homophobia were more comfortable coming out to friends who were affirming of LGB sexual identities.

Research suggests that LGB individuals who are more open at work experience higher levels of job satisfaction, commitment to the workplace, the fostering of a healthy identity, and the encouragement of employers to promote a diverse workplace (Day & Shoenrade, 1997; Griffith & Hebl, 2002; King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008). While there are positive aspects of research surrounding coming out at work, research also suggests that more than two-thirds of LGB people think coming out to the workplace would create problems (i.e., not being hired, not being promoted, not receiving support and mentorship necessary for professional development, or loss of job; Hunter, 2007). The context in which an individual comes out at work is much more important than the situational factors which lead them to come out (King, Reilly, & Hebl, 2008). Consequently, many LGB individuals stay closeted at work in anticipation of rejection, which is often based on a lack of legal protection or personal experiences with an anti-gay organizational climate.

Our study uncovered a strong relationship between internalized homophobia and level of outness at work. In fact, outness to colleagues was the largest predictor of internalized homophobia above and beyond all other variables analyzed in this study. Based on this finding, we defend previously cited research that LGB individuals are more likely to be out and experience less internalized homophobia when they have had positive experiences with coming out in the past, or when their organizations are gay-friendly, include written non-discrimination policies and advocate on behalf of LGB people (i.e., offer trainings and workshops that incorporate LGB issues; Griffith & Hebl, 2002). Friskopp and Silverstein (1995) concur with our findings by suggesting those who disclosed at work were not only more comfortable with their sexual identity, but also had many previous disclosures with heterosexual friends and relatives. In the same respect, LGB individuals who enter and remain in a workplace where heterosexism and homophobia are pervasive may never come out to co-workers or may be very selective about to whom they come out (Hunter, 2007). They might decide to pass to divide their work life and personal life, and avoid discrimination at all costs (DeJordy, 2008). Passing, while helpful in the organizational environment, can be harmful to the individual because it reduces an individual’s authenticity of one’s behavior, lowers one’s self-esteem, and denies or suppresses an individual’s LGB identity.

Results from the NLHCS (Bradford, Ryan, & Rothblum, 1993) support Hunter (2007) and our research: lesbians who were less out to co-workers had more fear of exposure as lesbian. For some LGB individuals, “just the thought of disclosure at work typically creates considerable anxiety” (Hunter, 2007, p. 124). This might be true for the participants in our study.

Finally, our hypothesis that internalized homophobia will predict outness to all family members, including nuclear and extended, was partially supported by our results. In particular, internalized homophobia was not a predictor of outness to nuclear family, but was a predictor of outness to extended family.

The fact that internalized homophobia did not predict outness to nuclear family was surprising considering the high degree of difficulty and anxiety associated with coming out to parents, the anticipated rejection by the nuclear family, and the fact that many LGB individuals remain closeted to family members indefinitely or until later in life (Hunter, 2007). Paul and Frieden (2008) contend that negative social messages about LGB sexual identities, particularly those made by family, friends, and religious organizations, increases the challenge of self-acceptance as LGB. With a lack of self-acceptance coupled with “fears related to a potential loss of relationship with specific family members,” LGB individuals might refrain from disclosing their sexual minority identities (Paul & Frieden, 2008, p. 43). It could be assumed that internalized homophobia would affect the act of coming out to family, particularly nuclear family, since “there is no predicting” how parents will react, and disclosure could cause “great turmoil in the home” (Hunter, 2007, p. 95.). Based on the aforementioned assumption, our initial hypothesis would stand. This conception, however, was not supported by the results of our study as internalized homophobia predicted outness to extended family and not nuclear family. It appears that the disclosures or lack of disclosures to nuclear family by participants in our study were not influenced by internalized homophobia. Future research that explores factors that impact disclosure to nuclear family is warranted in order to more fully understand this relationship.

Implications for Counseling

This study presents many implications for counselors. First, experiences with internalized homophobia can impact the lives of LGB individuals, particularly the coming out process.