May 10, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 1

Shainna Ali, John J. S. Harrichand, M. Ann Shillingford, Lea Herbert

Guyana has the highest rate of suicide in the Western Hemisphere. Despite this statistic, a wide gap exists in the literature regarding the exploration of mental wellness in this population. This article shares the first phase in a phenomenological study in which we explored the lived experiences of 30 Guyanese American individuals to understand how mental health is perceived. The analysis of the data revealed that participants initially perceived mental health as negative and then transitioned to a positive perception of mental health. We discuss how these perceptions affect the lived experience of the participants and present recommendations for counselors and counselor educators assisting Guyanese Americans in cultivating mental wellness.

Keywords: Guyanese American, mental health, phenomenological, mental wellness, perceptions

In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported Guyana as having the highest suicide rate in the world (44.2 suicides per 100,000 people; global average is 11.4 per 100,000 people). According to World Population Review (2023), within the Western Hemisphere, even after almost 10 years, Guyana remains the country with the highest rate of suicide—a concerning statistic. Responding to the WHO (2014) report, Arora and Persaud (2020) engaged in research to better understand the barriers Guyanese youth experience in relation to mental health help-seeking and suicide. Their research included 17 adult stakeholders (i.e., teachers, administrative staff, community workers) via focus groups, and 40 high school students who engaged in interviews. Arora and Persaud used a grounded theory approach and found the following themes as barriers to mental health help-seeking in Guyanese youth: shame and stigma about mental illness, fear of negative parental response to mental health help-seeking, and limited awareness and negative beliefs about mental health service. They recommended integrating culturally informed suicide prevention programs in schools and communities. In efforts to extend Arora and Persaud’s findings, we sought to further understand how Guyanese Americans define and experience mental health to better serve them in counseling.

Startled by the statistics presented by the WHO (2014) and Arora and Persaud (2020), we were compelled to focus our attention on this unique immigrant subgroup in the United States. It is important to note that between the WHO’s 2014 report and Aurora and Persaud’s research, no other studies related to Guyanese American suicidality are recorded in the literature. However, two studies on Guyanese American mental health emerged by Hosler and Kammer (2018) and Hosler et al. (2019). Our decision to conduct research on the Guyanese American community was further informed by Forte and colleagues’ (2018) review of immigrant literature in the United States, which stated that “immigrants and ethnic minorities may be at a higher risk for suicidal behavior as compared to the general population” (p. 1). Forte et al. found that immigrants, when compared with individuals in their homeland, were at an increased risk of experiencing mental health challenges like depression and other psychotic disorders. Currently, suicide is listed as the 10th leading cause of death overall in the United States (Heron, 2021). More specifically, within ages 10–34 and 35–44, suicide is the second and fourth leading cause of death, respectively. Heron’s (2021) report, referencing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), highlighted that in the United States, death by suicide (47,511) is 2.5 times higher than homicides (19,141). The prevalence of suicide among Guyanese people within and without the United States warranted further exploration of the experiences of this marginalized group.

The Guyanese American Experience

Comparing all countries with a population of at least 750,000 people, Guyana, a Caribbean nation, is said to have “the biggest share of its native-born population—36.4%—living abroad” due to remoteness and limited opportunities within the country to move from a lower to a higher socioeconomic status (Buchholz, 2022, para. 2). It is estimated that the United States is home to approximately 232,000 Guyanese Americans whose ancestry can be traced back to Guyana (United States Census Bureau, 2019), a country in the northeast of South America, bordered by Brazil, Venezuela, and Suriname. Although approximately 50% of all Guyanese immigrants in the United States reside in New York City alone (Indo-Caribbean Alliance, Inc., 2014), Guyanese people can be found across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (Statimetric, 2022). This draw to the United States, an English-speaking nation, might be linked to the fact that Guyana is the only country in South America that recognizes English as its official language (One World Nations Online, n.d.).

Like most immigrants, Guyanese immigrants travel to the United States seeking a better life and opportunities for themselves and their families. However, the process of transplanting can be bittersweet, in that Guyanese immigrants might be forced to relinquish their identity and customs and embrace American customs through assimilation (Arvelo, 2018; Cavalcanti & Schleef, 2001). For many Guyanese immigrants, being caught between leaving their homeland and beginning life in their adoptive home can lead to a cultural clash, resulting in problematic coping mechanisms (e.g., minimizing/hiding mental health challenges, cultural shedding [adopting American identity and losing cultural heritage]; Arvelo, 2018).

As discussed above, suicide in the Guyanese community is unquestionably a serious concern, but the community faces other challenges in the United States as well. For example, Hosler et al. (2019) found a statistically significant association between discrimination experience and major depressive symptoms in a sample of Guyanese Americans. However, Hosler et al. (2019) also found mean scores on the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS; Williams et al., 1997) were lower (i.e., less discriminatory experiences in everyday life) for Guyanese Americans when compared to other groups (Black, White, and Hispanic) because Guyanese Americans have a more cohesive interpersonal network. It would appear that Guyanese Americans experience lower everyday discrimination because they operate within interpersonal spaces that are more cohesive, yet their discriminatory experiences are positively associated with depression symptoms, which is a source of concern.

Another area of concern among Guyanese Americans is intimate partner violence (IPV), yet research remains lacking (Baboolal, 2016), leading us to draw directly from Guyanese literature. In Guyana, IPV is one of the most prevalent forms of violence (Parekh et al., 2012). As a country, although Guyana endorses the commitment to gender equality, women are the majority only in the tertiary sector (e.g., education, human services, clerical services, and tourism). Nicolas et al. (2021) stated that “domestic duties, marriage, and child-bearing, particularly for women between the ages of 25–29, have hindered their labor force participation” (p. 147). They documented that 1 in 6 Guyanese women, mostly from rural parts of the country, hold the belief that beating one’s wife is necessary (i.e., husbands are justified in beating their wives, resulting in domestic violence being a relevant mental health issue). In fact, suicide is identified as a public health issue for Guyanese women, who use it as a means of coping “with economic despair, poverty, and hopelessness . . . [and] to escape family turmoil, relationship issues, and domestic violence” (Nicolas et al., 2021, p. 148). However, even with access to mental health services increasing in Guyana, seeking out mental health care is uncommon due to stigma, lack of communication, inadequate financial resources, limited providers, and other barriers related to access (Nicolas et al., 2021). Within the U.S. literature, there remains a dearth of information on the experiences of this group as it relates to suicide and IPV. Most likely, this is a result of racial categorization within the United States, where, based on phenotype and racial composite, individuals are often lumped into one category, such as Black. As important as Guyanese literature on IPV is to inform the work of counselors, we believe it is equally important for us to engage in research regarding IPV and other mental health challenges on Guyanese Americans specifically. Learning about Guyanese Americans’ perceptions of mental health may facilitate closing the gap in the utilization of mental health services, warranting the current investigation.

Recognizing the noticeable research gap related to the mental health experiences of Guyanese Americans, we conducted a thorough review of the literature related to mental health and well-being. Through databases such as PsycINFO, ProQuest Central, Web of Science, MEDLINE, and SocINDEX, using the search terms “Guyanese Americans, Health and Wellbeing, Mental Health of Guyanese Americans, Access to Mental Health,” 54 search results were found. However, only two applicable studies were found to address Guyanese Americans’ mental health specifically (Hosler & Kammer, 2018; Hosler et al., 2019). The other search results were either not research manuscripts (i.e., reflections and newspaper articles) or addressed other constructs specific to the Guyanese people (e.g., family, education). The first study by Hosler and Kammer (2018) focused specifically on the health profiles of Guyanese immigrants in Schenectady, New York. This study was conducted with 1,861 residents between the ages of 18–64 years. Guyanese Americans from Schenectady were mostly from a low socioeconomic status, which resulted in them being less likely to have health insurance coverage, an identified place to receive care, and access to cancer screenings. They were also identified as being more likely to engage in alcohol binge drinking—all conditions of significant concern to us, resulting in the present study. In fact, Hosler and Kammer reported that Guyanese Americans are among the lowest group of those insured in the United States when compared with other minority groups such as Black and Latinx groups. Some researchers believe ethnocentric stereotyping, cultural incompetence by professionals, a lack of steady employment, and poor previous interactions with the health care system are barriers Guyanese immigrants experience when accessing medical and mental health services (Arvelo, 2018; Cheng & Robinson, 2013; Jackson et al., 2007).

The second study of Guyanese immigrants was conducted by Hosler et al. (2019) and explored everyday discrimination experiences and depressive symptoms in relation to urban Black, Hispanic, and White adults. This study included 180 Guyanese Americans (i.e., both citizens by birth and naturalized citizens/immigrants), all 18 years and older, from Schenectady, New York. The researchers found a significant independent association between the EDS score and major depressive symptoms for Guyanese Americans, suggesting that discrimination experiences might be an important social cause for depression within this community. Based on the reported challenges faced by Guyanese Americans, as well as our desire to contribute meaningfully to the extant body of literature on the Guyanese American community, we conducted a phenomenological inquiry. More specifically, we sought to better understand the lived experiences of Guyanese Americans pertaining to mental health (i.e., definitions, beliefs, practices), and how they access and incorporate mental health resources to mitigate the known mental health risks of this population in the United States, in the hopes of creating tailored methods for culturally responsive care.

Method

Because limited mental health research exists on this unique community, the present study, which is part of a larger research endeavor, sought to explore Guyanese Americans’ lived experiences with mental health. To lay the foundation of understanding, the present study focused on Guyanese Americans’ perceptions of mental health. Phenomenology, a constructivist approach, recognizes the existence of multiple realities and provides an understanding of participants’ lived experiences using their own voices (Haskins et al., 2022). We selected transcendental phenomenology (Moustakas, 1994) as the appropriate methodology for answering our research questions, as it is congruent with the counseling profession’s similar objective of understanding the human being. Akin to the practice of counseling, transcendental phenomenology emphasizes methods of the researcher to best set aside the potential clouds caused by bias in an effort to allow the explored phenomenon to surface. Transcendental phenomenology aligns with one of the core professional values in the American Counseling Association’s Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014), that of supporting “the worth, dignity, potential, and uniqueness of people within their social and cultural contexts” (p. 3). It also aligns with Ratts et al.’s (2015) Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC), specifically understanding the client’s worldview domain. Our focus on Guyanese Americans, an understudied minority group in the United States (Hosler & Kammer, 2018) originating from a country that has been identified as having the world’s highest suicide rate (WHO, 2014), led us to select this method so that we could maintain cognizance of our surroundings, hold respect for the population, and examine participants’ experiences (Haskins et al., 2022; Hays & Singh, 2012; Hays & Wood, 2011).

Participants

Before participants were recruited for the study, IRB approval was obtained from the university with whom Shainna Ali, M. Ann Shillingford, and Lea Herbert are affiliated. Purposive criterion sampling was used to recruit participants, leading to a sample of adults who self-identified as Guyanese American (i.e., either immigrated to the United States themselves or had at least one parent who was born in Guyana). Recruitment materials were shared with Guyanese Americans using counseling listservs (i.e., ACA–AMCD Connect and CESNET) and social media platforms (i.e., LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram). Members of the research team contacted all participants using email to share details regarding the study and the informed consent document, collect demographic data, and schedule individual interviews. According to qualitative research, sample size recommendations range from six to 12 participants (Creswell, 2013; Guest et al., 2006; Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2007). Hence, we sought to recruit 15–20 participants to account for the possibility of attrition.

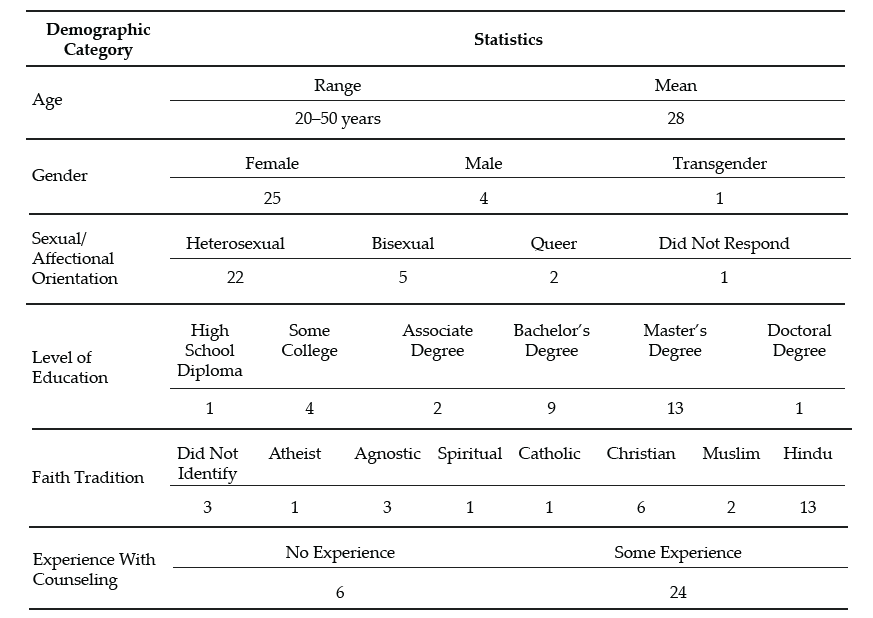

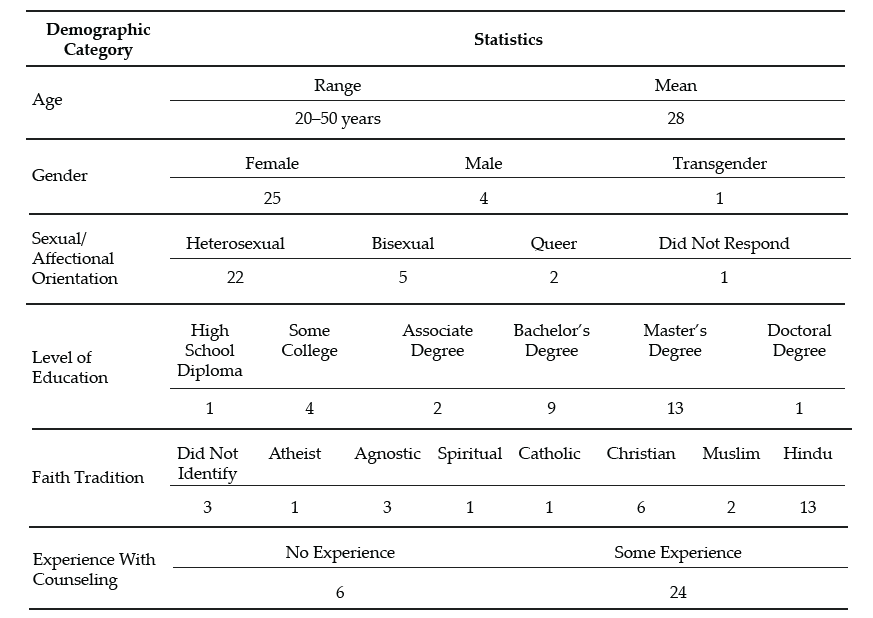

Our recruitment efforts yielded 73 individuals who expressed interest in the study, 60 of whom met all inclusion criteria and were initially contacted. Forty-three individuals were unable to complete an individual interview due to scheduling conflicts; hence, we secured a total of 30 participants who completed the study. Of this number, 17 participated in individual interviews and a total of 23 individuals participated in a one-time focus group to further clarify data from the individual interviews. It should be noted that 10 of the 23 focus group participants also participated in the individual interview. Further recruitment was deemed unnecessary, as the data analysis reached saturation with data from the individual interviews and focus group. We present demographic data on all participants who engaged in the study, both individual interviews and the focus group (N = 30), in Table 1.

Table 1

Participant Demographic Data

Note. This table provides a breakdown of the demographic characteristics of Guyanese American participants (N = 30).

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants engaged in a semi-structured interview lasting 30–60 minutes, conducted by Ali and Shillingford. Interviews were conducted via Zoom, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The interview protocol consisted of three primary questions, and sub-questions were used to clarify responses: 1) How do you define mental health?; 2) Who in your life has had experiences with mental health?; and 3) What experiences have you had with mental health? Prior to conducting our study, we included in our IRB documentation that data collection of individual interviews would follow saturation guidelines and that a focus group could be used for further data illumination. Following initial data analysis, we found it necessary to conduct a 1-hour follow-up focus group via Zoom to probe deeper into the data and to allow participants to clarify concepts related to emerging themes. Upon the first round of analysis, it was noted that several participants experienced a shift in perceptions regarding mental health. Focus group probes explored whether participants noticed this shift, what may have contributed to this shift, and when the shift occurred.

After all focus group and individual interviews were transcribed, we used guidelines outlined by Moustakas (1994) to analyze the data. First, we immersed ourselves in the data, reviewing each transcript individually. The transcripts were then divided equally among the four researchers, who read through each to become familiar with the data. With each transcript, we identified relevant statements reflecting participants’ lived experiences (horizontalization) as Guyanese Americans within the contexts of mental health beliefs and experiences.

Following this process, we met multiple times to review all transcripts and confer about the textural descriptions. We identified relevant codes, then synthesized the textural descriptions into themes based on commonalities, distilling the meaning expressed by participants. Then we engaged in reduction and elimination via consensus coding. This process included reading and rereading transcripts together, which followed an iterative process of reviewing the text and code, coding, rereading, and recoding, before determining which thematic content was a new horizon or new dimension of the phenomenon.

After all transcripts were analyzed following this reduction process, clustering and thematizing occurred (i.e., thematic content was clustered into core themes based on participant experiences; Hays & Singh, 2012; Moustakas, 1994). We extracted verbatim examples from the transcripts to generate a thematic and visual description of the phenomenon being examined. After completing the initial data analysis, we conducted member checking by sending each participant their individual transcript as well as the written results section. Participants were requested to provide feedback on the accuracy of their transcripts. Additionally, following the focus group and elucidation of themes all participants were offered an opportunity to member check and clarify the degree to which the results aligned with their lived experiences. The participants did not report any errors; however, clarification was offered by one participant.

Trustworthiness and Positionality

Trustworthiness is a key element of qualitative research in which the research findings accurately reflect the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). A critical element of maintaining research credibility is through reflexivity, wherein researchers critically examine procedures employed in relation to power, privilege, and oppression (Hunting, 2014). To safeguard against researcher bias, we worked collaboratively to establish and maintain credibility throughout data collection and analysis processes. Our research team consisted of one Indo-Guyanese American female faculty member, one Afro-Guyanese American female doctoral student, one Black female faculty member, and one Indo-Chinese-Guyanese Canadian male faculty member. All three faculty members belong to CACREP-accredited counselor education programs, and all four researchers have clinical experience working with diverse populations.

To address researcher bias, we engaged in bracketing to minimize the ways in which our experiences influence our approach to research and expectations of the outcomes of the study. Prior to data collection, we discussed our experiences in relation to Guyana, mental health in the Guyanese American community, and our roles as mental health leaders and advocates. We identified our personal experiences, acknowledged our biases, and attempted to bracket while conducting the interviews and focus group. Throughout the data collection and analysis processes, we participated in personal reflection and kept analytic memos documenting our reactions and initial thoughts about the data collected.

Before analyzing the data, we met to confirm analysis procedures, ensuring consistency. We initially analyzed data individually, then determined codes and themes as a team to reduce bias. Throughout the data analysis process, we consulted with each other, addressing questions or concerns related to the data. We also consulted with an outside researcher experienced in qualitative research to obtain critical feedback on the data analysis process and the research findings (Marshall & Rossman, 2006). Our consultant served as an external check of the research methodology and theoretical interpretation of the data.

Findings

The results of the analysis increase understanding of the lived mental health experiences of Guyanese Americans by elucidating perceptions of mental health (Creswell, 2013). All participants shared their beliefs about mental health and the direct and indirect experiences that informed their conceptualization. Three themes surfaced. The first two showed a clear divide in the data: 1) mental health being perceived as negative, stigmatized, elusive, and intimidating; and 2) mental health being perceived as positive, important, helpful, and empowering. It is important to note that these primary themes were not representative of two subsets of participants, and this extracted another theme, which centered on the tendency of participants’ beliefs to transition from negative to positive views of mental health.

The Perception of Mental Health as Negative

When exploring obstacles, subthemes emerged in which hindrances to mental health were acknowledged to exist across three levels: individual, familial, and sociocultural. In parallel, these three subthemes were echoed in the exploration of factors that participants acknowledged have contributed to their mental wellness. The following section explores the primary themes in detail by highlighting the participants’ voices in describing their lived experiences.

Mental Health Concerns Are a Sign of Weakness

All participants in the individual interviews shared that they originally believed that mental health developed out of weakness. This belief was often attributed to minimizing remarks from family members. Oftentimes these comments were paired with other suggestions of how to ameliorate symptoms such as praying more, working harder, or contributing to physical health (e.g., drinking tea). Sharon shared:

It was just like, oh no, you just need to read a book or you just need to go and do something and take your mind off of however it is you’re feeling, like there’s no reason for you to be sad, you have a roof over your head and you’re going to school and you’re doing all of these things, it doesn’t matter. There’s no reason for you to be sad or feel any type of way about anything because we provide everything for you.

Several participants noted that investment in physical wellness was preferable to mental wellness, although physical health was not genuinely prioritized. Participants shared personal and observed maladaptive coping with poor eating habits (i.e., quality and quantity) and excessive substance abuse, namely alcohol. Some participants shared that these tactics were used to manage mental health symptoms or avoidance. Christine shared, “When you’re struggling with things . . . you have nowhere to go to with them except alcohol and the bottom of a rum bottle.” Many participants recognized that coping with alcohol is normalized within the culture. Further, the commonality of these methods normalized consumption and have caused additional issues (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, alcoholism). Arjun noted:

We all have relatives that are kind of stuck on the whole drinking issue. We know a lot of them. They get together with their friends and they “lime,” as we like to call it. They drink in groups and they “gyaff,” they have fun. But it’s a completely different story when they’re by themselves and they’re drinking.

Mental Health Is Taboo

A general consensus was that all participants in the study once believed that mental health was not important and that mental health problems were shameful and not to be discussed. This consistent trend was one of the reasons that we opted to further understand responses through a focus group. Therefore, a direct probe was offered to the focus group participants to explore if they believed discussing mental health was taboo. When delving deeper into these perceptions, participants noted that these thoughts were informed by the beliefs of others and upheld in the wider cultural paradigm. All participants reported that, generally, mental health should not be talked about in order to save face and be respectful. Because mental health issues were seen to be synonymous with weakness, sharing about mental health was equated with the risk of bringing shame to oneself or to one’s family. For example, Chandra shared that “Guyanese people don’t want a kid that’s broken or a little off.” Hence, if someone opts to discuss their mental illness, it is to be done carefully, or secretly.

Most participants shared that typically, when divulging their symptoms, they went to an elder, often a parent, grandparent, or elder sibling, in an effort to keep concerns within the family system. However, many participants noted being minimized or dismissed when sharing their concerns with family members. Ramona explained her feeling that her family

is really strong about, like, don’t be selfish. And I wonder if they would categorize it under that. Like if you’re taking up too much space or time or whatever, you’re trying to center the attention on you or whatever, so that’s a self-serving thing.

A generational rule of discourse emerged from the data. Though the tendency was to keep mental health discussions within the family system, it was also atypical for a younger member to address observed issues with an elder. Several participants noted that this hidden guideline kept informed younger generations from being able to utilize their recognition of warning signs to help the given person and the family system. Arjun shared that as he’s gotten older and has learned more about mental health, he has acquired the courage to address the problems he sees with elders, including his uncle:

I said, “Uncle, what’s wrong?” And he said, “No, nothing is wrong.” But he was crying, you could see tears were streaked on his face, but he wouldn’t talk about it—he wouldn’t say anything. It’s not only one time I saw him, it’s multiple times that I’ve seen him when he has been drinking by himself, that he kind of has the same face all the time. Prior to the times that I asked him, I kind of looked at him and I kind of walked away the first couple of times. Because I was kind of like, this is not something that looked like I should butt in, as a child especially. When you’re younger, your parents tell you, “Mind your business.” Or they say, “You’re not an adult, go with the kids.” So . . . the first couple of times I saw him, I kind of avoided it.

Others Are Not To Be Trusted

Some participants noted that beyond the purpose of family protection, caution to mental health discourse was also due to lack of trust of others. Christine explained: “We had a counseling center on campus, but I was like, ‘Oh, I can’t go talk to anybody,’ because that’s what I was raised with. You don’t talk to strangers about your problems. I had to keep everything inside.” Nevertheless, some families encouraged talking to a religious leader to assist the individual in enhancing devotion and reducing mental health symptoms. Still, regarding professional mental health services, many participants believed, at least at one time, that such services are not helpful, providers are not to be trusted, assistance of that nature is for other (e.g., White) people, and succumbing to that level of desperation is a sign of weakness. When sharing about mistrust in professional mental health assistance, misconceptions and stereotypes surfaced. Ramesh shared:

Oh boy. I have to be honest with you, I feel counseling is, I’ll speak to a shrink and they’ll prescribe drugs to me, like Ritalin or . . . I was like, you know what, I’m better than that. I’m probably totally wrong about it, but that’s just the perception that I have. I’ll be laying on the couch and I’m going to speak into someone and then they’re going to prescribe drugs to me. I don’t want that. I can try to figure this out on myself by talking and trying to do things—positive behavior.

Mental Health Perceived as Positive

All participants in the individual interviews acknowledged a shift in their perceptions of mental health. Their newfound conceptualization included a holistic view of wellness in which mental wellness was seen as an important component to overall well-being and quality of life. In this newer perception, participants acknowledged the ability to consider more variables influencing mental health than they recognized in the past. For example, many participants noted a link between mind and body, versus the previously held notion that physical health is more important than mental health. A few participants noted that mental health can be influenced by genetics, while some noted that it could be influenced by personality, and others noted that it can be influenced by people and the surrounding environment.

All participants, from both the individual interviews and focus group, concurred that everyone feels mental health effects; furthermore, showing signs of a problem is not attributed to weakness. Moreover, because mental health affects everyone, a widespread belief emerged that we all have the responsibility to foster our mental wellness. Additionally, participants shared several examples of what naturally ensued without investing in strategies for mental health such as challenges with emotional regulation, coping, relationships, and worsening mental health problems.

The Transition Between Negative and Positive Perceptions

The transition between old and new conceptualizations of mental health was informed by direct and indirect experiences. All participants shared a transition in beliefs in the individual interviews, and this was explored in the focus group for further clarification. Most participants shared that their personal mental health history informed a change in their beliefs. Many of these participants noted the influence of their healing process, most notably seeking professional help. All participants, from both the individual interviews and the focus group, shared at least one example of learning about mental health by observing another person’s experience. For example, Jessie shared, “Unfortunately, I came from a home of domestic violence . . . I was around maybe six, my dad was bipolar . . . [and] he was just a wife beater. That is probably when I can recall [learning] of mental health.” Another example of learning about mental health from others is captured in Reginald’s comment:

[As] an only child . . . my parents took it upon themselves to [teach me]. . . . It wasn’t like, “Okay, sit down. Let me tell you why these things are.” It was just we’ll be talking about somebody else or going over something that happened and then they’ll explain why, but never directly for me. It was always about other people’s kids.

Many of these individuals emphasized the belief that by paying attention to others, you can learn what is helpful and unhelpful for mental health. Oftentimes this was in their own family; however, extended family and community members were also highlighted. Moreover, a few participants shared their recognition that living with someone who is struggling with their mental health may negatively impact personal wellness (e.g., be triggering). Beyond the family system, some participants noted that exposure to other cultures and perceptions of mental health informed a conceptualization of mental wellness. Seeta shared:

I had friends of other religions or like no religions. And then we would talk about a lot of different things. Like I would ask them questions like, “Oh, so how do things work in your house? Do your parents talk about your God or whatever?” And they’re like, “No.” And I’m like, “So where do your emotions come from?” And they’re like, “Well, you know, we just feel them. Some days I feel angry and some days I feel sad, some days I feel happy.” And I’m just like, “Okay, this is interesting.”

From the quote, it might appear that one’s emotions are in some way connected with God or another higher power; however, this is not something that was observed with other participants of our study. It was more common for participants to share stories of their families using religion as the solution to mental health concerns. For example, Yolanda shared:

My grandmother came when I turned 16 and she kept trying to tell my mom I was showing signs of depression. And my mom was like, “No, she’s like that all the time, like, that’s just how she is.” And my grandma was like, “That’s not normal. You should get her checked out.” And my mom kept saying, “No” and kept denying it. And then my grandma said, “You have to do something.” And then my mom replied, “Oh, I’m going to pray for her.”

In addition to personal experiences and observations of others, participants noted that improved mental health awareness and education prompted them to think critically about their mental health schemas. Ramesh shared:

My education, I always feel like this is what saved me in the end, because I was able to be around other people to know better and to come back home and be like, “Excuse me, this is not how we do things. This is not how we say things. I don’t know what it was like in Guyana.”

Some participants associated this with growing older, and others noted their personal initiative to improve mental health knowledge by following mental health pages on social media, taking a related class, and for some, becoming a part of the mental health field themselves. From this vantage point, many participants were able to equate their previously held notions with beliefs embedded in the culture such as generational rules of respect, gender differences, and the impact of colonialism. Participants, despite their gender differences, noted that within the cultural framework, the rule that mental health should not be discussed is disproportionately applicable to males. Participants shared that this is often due to the perception that it is important for men to be strong, and again, mental illness is a symptom of weakness. This was also linked to the breadwinner role and the pressure to provide for the family. However, this was only noted to have detrimental effects, as anger issues, IPV, and alcoholism were noted to arise out of this rule. Some participants noted that the survival aspect of colonialism may have contributed to the lack of privilege to focus on mental health. In addition, the history of colonialism in Guyana (i.e. slavery, indentured labor) could have informed the lack of trust in professional services.

The change in mental health conceptualization was noted to have benefits beyond the participants themselves. Some participants remarked that the shift in perception was recognized in the wider generation. Ramona reflected:

I will say that a lot of folks from my generation have been a lot more like, “Go to therapy. We should be taking care of our thoughts and our feelings or emotions.” That’s important to you in the same way that if you tore a ligament that you would need to get surgery or do whatever.

Within the newfound conceptualization of mental wellness emerged a vow of social responsibility. All participants, from both the individual interviews and the focus group, shared their intention to help others, and some even noted it as their duty. Ways to help others included advocating for mental health awareness, access, and education; helping to challenge unhelpful cultural beliefs; breaking generational cycles; and protecting others from experiencing similar struggles (e.g., child, sibling).

Discussion

The findings from this study are enlightening, and some are the first to be documented through research, even if they were observed in practice. Initial perceptions of all participants, from both the individual interviews and the focus group, were that mental health is a taboo topic and seeking mental health services is bad. These perceptions stemmed from fear, mistrust, and limited awareness of the benefits of mental health services. This is consistent with findings from Arora and Persaud (2020), who surmised that Guyanese individuals hold negative views of mental health that significantly impact their help-seeking. Furthermore, the findings point to strong familial and sociocultural influences, such as beliefs about mental health, that swayed individual perceptions of mental health, which is in keeping with recent literature on affirming cultural strengths and incorporating familial identity in working with clients of Guyanese descent (Groh et al., 2018; Nicolas et al., 2021).

Discussing issues related to mental health was viewed as a sign of weakness, which translated to help-seeking being a taboo. It would appear that the stigma associated with mental health remains a common experience for Guyanese Americans, and when coupled with limited communication, insufficient funding, and lack of providers, we can see how Nicolas et al. (2021) found this to be concerning. Cultural clash, ethnocentric stereotyping, and cultural incompetency may also be responsible for Guyanese Americans being distrustful of the health care system, leading them to engage in maladaptive behaviors (i.e., avoidance, use of substances, IPV) and not receive the mental health attention and care they need (Arvelo, 2018; Cheng & Robinson, 2013; Jackson et al., 2007).

It appears that even in the face of discrimination and experiences of mental health challenges like alcoholism, depression (Hosler & Kammer, 2018), and IPV (Parekh et al., 2012), leaning on the support of the community serves to buffer against mental health challenges for Guyanese Americans. It also seems that changing mental health perceptions from negative to positive was significantly related to mental health literacy and exposure to other systems such as school, work, and community (i.e., cross-cultural exchange).

Findings that were not previously documented in the literature suggest that an integrated view of wellness enabled participants to augment their negative abstractions of mental health care. These findings serve as an indication that among Guyanese Americans, although mental health has been perceived as negative, weak, and a taboo, the narrative is beginning to shift to make space for mental health awareness, education, access, and functioning, thereby creating unique implications for counselors seeking to meet the needs of this immigrant subgroup.

Implications

In combination with prior literature, the results of this study provide a rationale for mental health counselors, marriage and family counselors, school counselors, and counselor educators to inspire dialogue to foster mental wellness. Based on the findings from this study, when working with Guyanese Americans, counselors should focus on three key strategies to support Guyanese American clients: (a) mental health awareness, (b) mental health education, and (c) mental health experience.

Mental Health Awareness

Participants in this study initially held limited views and awareness of the signs and symptoms of mental health. When awareness was heightened through various means, they were more open to exploring the benefits of services. Counselors can be instrumental in creating awareness by first raising their own awareness pertaining to cultural stigma and its influence on Guyanese Americans’ mental health. For example, unwillingness to attend counseling sessions may be linked to the culturally held perception that discussing mental health, especially beyond the core family system, is taboo. In acknowledging this, counselors can raise awareness of confidentiality, which can be seen as an alignment with the cultural notion that talking about mental health is taboo when it means talking to anyone, and the role of the counselor can be highlighted as a professional collaboration versus communal gossip. Counselors need to be mindful of the collectivistic nature of Guyanese American culture, which causes personal and familial illnesses alike to be perceived as personal problems. Rather than dismiss a client’s concerns about mental health, a counselor can benefit from exploring how the family members’ symptoms, perceptions about mental health, and willingness to adhere to treatment influence the client’s symptoms, perceptions, and commitment to counseling. Further, collectivism spans beyond the protective family system. On one hand, this community orientation can be used to explore a broad range of support, yet on the other hand, depending on the client’s experience, this may also be a widened range of societal pressure (e.g., judgment, criticism, shame).

Mental Health Education

Increased understanding of mental health appeared to have led participants to seek services and resources to increase their mental health literacy, with the hope of improving their well-being. Counselors and counselor educators can be instrumental in offering Guyanese Americans mental health education. To begin, all mental health professionals should demonstrate a posture of cultural humility when engaged in psychoeducation on mental health and wellness for this population. In order to raise awareness through education, mental health professionals are encouraged to model trust, respect, sensitivity, compassion, and a nonjudgmental stance. Within session, counselors should be prepared to offer information regarding early signs of mental illness, compounding factors (e.g., alcohol, suicidal ideation, domestic violence), obstacles (e.g., stigma), and resources. Additionally, counselors may need to offer psychoeducation on the family system, roles, dynamics, beliefs, experiences, and generational patterns that can influence individual mental health. In the event that a family member with mental health problems is unwilling to seek assistance, helping the client to better understand the diagnosis and cope personally can be empowering. Finally, to employ the collectivistic nature of Guyanese American culture, stigma can be confronted, and mental health education can be effectively offered by providing group counseling within this population. Group counseling can offer a variety of therapeutic factors that can benefit Guyanese Americans such as universality, hope, and corrective recapitulation of the primary family group (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005).

Beyond the counseling office, counselors and counselor educators should consider collaborating with culturally supportive organizations. Workshops and information sessions can be tailored to explore and address cultural, religious, ethnic, and generational differences in addition to offering mental health resources (e.g., signs, symptoms, treatment). Several of the participants in our study shared that access to psychology courses in school helped to improve their knowledge about mental health. In addition to these classes continuing to be offered, accessibility to such courses should be expanded. Schools and universities may benefit from offering workshops and other informational sessions to support mental health. Beyond information being offered, a follow-up may be beneficial by linking school or campus counselors in order to connect an improvement in awareness and education to action, change, and health.

Several participants shared that because of a lack of access to mental health education, their knowledge was attained through social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok. Although the quality of mental health education was not assessed in the present study, the lack of regulation on social platforms could perpetuate misleading, confusing, and stigmatizing misinformation surrounding mental health. Counselor educators should consider their roles beyond the classroom. In addition to empowering counselor trainees to utilize the suggestions above to foster awareness and education, counselor educators can offer responsive and succinct information via social media. Whereas social media is not an appropriate platform for tailored education or services, brief information can be offered to bridge the gap between awareness, education, and access.

Mental Health Experience

Growth in awareness and knowledge around mental health resulted in participants intentionally engaging in positive experiences as a way of resisting past harmful and hurtful practices and generational patterns, reauthoring a new narrative of hope and healing. Being wellness-focused, counselors are uniquely positioned to support this community by facilitating positive experiences impacting overall mental health and well-being.

Counselors can honor clients from this community by creating safe spaces for them to share their narratives without judgment. Counselors can foster healing communities through group counseling, where clients collaboratively share each other’s mental burdens and celebrate successes (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). Counselors can honor collectivism by encouraging clients to participate in support groups in addition to personal counseling. Counselors and counselor educators can enhance the approachability of counselors by improving their visibility in the community. Examples include a community counselor being involved in outreach with a local cultural center, a school counselor offering mentorship with student clubs, a college counselor guest-speaking at a Guyanese American student organization meeting, or a counselor educator offering tailored workshops for the community.

In addition to the aforementioned implications, we believe that in order for counselors to bridge generational gaps in counselor distrust, counselors must acknowledge the lack of representation of diversity within the profession of counseling, the predominance of Western and European cultural and psychologist-centered curriculum, and lapses in poor bioethics and power dynamics among counselors and marginalized communities (Singh et al., 2020). Next, the specific intersectional impacts suggest counselors must adapt a multicultural orientation and illuminate cultural sensitivity. When a clinician enacts cultural sensitivity in session, clients can examine their perceptions of illness and center their multiple identities (Davis et al., 2018).

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations that arose from the research process are important to mention. All interviews were conducted virtually. Although secured virtual platforms such as Zoom are considered acceptable for research, lack of face-to-face interviewing may have excluded subtle visual cues and induced video-conferencing fatigue (Spataro, 2020). Though researchers made great attempts to increase participant comfort and review the informed consent before the interview process, it is also plausible that respondents may have censored their responses out of concern for potential breach in confidentiality. A majority of respondents are college-educated, female, first generation, and of Indo-Guyanese descent; hence, the results may not be representative of all Guyanese Americans. Additionally, aligned with phenomenological methods of exploring lived experiences, research prompts were general. Recognizing the concerning statistics surrounding suicide (WHO, 2014), a future study exploring suicidality could be beneficial. Future research might seek to explore a more diverse pool of participants, including diversity in gender, age, ethnicity, and number of years in the United States. To build on the findings from the present study, future studies should explore what factors contribute to Guyanese American mental health as well as what variables may hinder mental wellness. It may also be beneficial to include research from the perspective of children and parents to further understand the influence of family systems and cross-generational norms.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the crucial need to address the mental health literacy of Guyanese Americans. The findings illuminate Guyanese Americans’ perceptions of mental health, including the transition from negative to positive perceptions and its potential influences. Efforts should be made to promote awareness, education, and experience related to mental health awareness for Guyanese Americans. Supporting mental health may help to reduce alarming rates of mental illness in Guyanese Americans and may also have the potential to influence related groups such as Guyanese, American, and Caribbean individuals. Counselors and counselor educators have the potential to play a significant role in supporting these clients by being cognizant and informed about cultural considerations.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Arora, P. G., & Persaud, S. (2020). Suicide among Guyanese youth: Barriers to mental health help-seeking and recommendations for suicide prevention. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 8(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2019.1578313

Arvelo, S. D. (2018). Biculturalism: The lived experience of first- and second-generation Guyanese immigrants in the United States (Order No. 10749930) [Doctoral dissertation, Chicago School of Professional Psychology]. ProQuest One Academic. (2027471070).

Baboolal, A. A. (2016). Indo-Caribbean immigrant perspectives on intimate partner violence. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 11(2), 159–176. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336926774_Indo-Caribbean_Immigrant_Perspectives_on_Intimate_Partner_Violence

Buchholz, K. (2022, November 11). The world’s biggest diasporas [Infographic]. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katharinabuchholz/2022/11/11/the-worlds-biggest-diasporas-infographic/?sh=4185fd634bde

Cavalcanti, H. B., & Schleef, D. (2001). Cultural loss and the American dream: The immigrant experience in Barry Levinson’s Avalon. Journal of American and Comparative Cultures, 24(3–4), 11–22.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-4726.2001.2403_11.x

Cheng, T. C., & Robinson, M. A. (2013). Factors leading African Americans and Black Caribbeans to use social work services for treating mental and substance use disorders. Health & Social Work, 38(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlt005

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Davis, D. E., DeBlaere, C., Owen, J., Hook, J. N., Rivera, D. P., Choe, E., Van Tongeren, D. R., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Placeres, V. (2018). The multicultural orientation framework: A narrative review. Psychotherapy, 55(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000160

Forte, A., Trobia, F., Gualtieri, F., Lamis, D. A., Cardamone, G., Giallonardo, V., Fiorillo, A., Girardi, P., & Pompili, M. (2018). Suicide risk among immigrants and ethnic minorities: A literature overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071438

Groh, C. J., Anthony, M., & Gash, J. (2018). The aftermath of suicide: A qualitative study with Guyanese families. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(3), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.01.007

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Haskins, N. H., Parker, J., Hughes, K. L., & Walker, U. (2022). Phenomenological research. In S. V. Flynn (Ed.), Research design for the behavioral sciences: An applied approach (pp. 299–325). Springer.

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford.

Hays, D. G., & Wood, C. (2011). Infusing qualitative traditions in counseling research designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(3), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00091.x

Heron, M. (2021). Deaths: Leading causes for 2019. National Vital Statistics Reports, 70(9), 1–113. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:107021

Hosler, A. S., & Kammer, J. R. (2018). A comprehensive health profile of Guyanese immigrants aged 18–64 in Schenectady, New York. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(4), 972–980.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0613-5

Hosler, A. S., Kammer, J. R., & Cong, X. (2019). Everyday discrimination experience and depressive symptoms in urban Black, Guyanese, Hispanic, and White adults. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 25(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390318814620

Hunting, G. (2014). Intersectionality-informed qualitative research: A primer. The Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy. https://nanopdf.com/download/intersectionality-informed-qualitative-research-a-primer-gemma-hunting_pdf

Indo-Caribbean Alliance, Inc. (2014, February 3). Population analysis of Guyanese and Trinidadians in NYC.

https://www.indocaribbean.org/blog/population-analysis-of-guyanese-and-trinidadians-in-nyc

Jackson, J. S., Neighbors, H. W., Torres, M., Martin, L. A., Williams, D., & Baser, R. (2007). Use of mental health services and subjective satisfaction with treatment among Black Caribbean immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 60–67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1716231/

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2006). Designing qualitative research (4th ed.). SAGE.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. SAGE.

Nicolas, G., Dudley-Grant, G. R., Maxie-Moreman, A., Liddell-Quintyn, E., Baussan, J., Janac, N., & McKenny, M. (2021). Psychotherapy with Caribbean women: Examples from USVI, Haiti, and Guyana. Women & Therapy, 44(1–2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2020.1775993

One World Nations Online. (n.d.). Guyana. https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/guyana.htm

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). A call for qualitative power analyses. Quality & Quantity, 41, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-005-1098-1

Parekh, K. P., Russ, S., Amsalem, D. A., Rambaran, N., Langston, S., & Wright, S. W. (2012). Prevalence of intimate partner violence in patients presenting with traumatic injuries to a Guyanese emergency department. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 5(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1865-1380-5-23

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies. American Counseling Association. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf

Singh, A. A., Appling, B., & Trepal, H. (2020). Using the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies to decolonize counseling practice: The important roles of theory, power, and action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12321

Spataro, J. (2020). The future of work—the good, the challenging & the unknown. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/blog/2020/07/08/future-work-good-challenging-unknown/

Statimetric. (2022). Distribution of Guyanese people in the US. https://www.statimetric.com/us-ethnicity/Guyanese

United States Census Bureau. (2019). People reporting ancestry: American community survey. http://bit.ly/42RazKC

Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351.

https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539700200305

World Health Organization. (2014). First WHO report on suicide prevention. https://www.who.int/news/item/04-09-2014-first-who-report-on-suicide-prevention

World Population Review. (2023). Suicide rate by country 2023. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/suicide-rate-by-country

Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. (2005). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (5th ed.). Basic Books.

Shainna Ali, PhD, NCC, ACS, LMHC, is the owner of Integrated Counseling Solutions. John J. S. Harrichand, PhD, NCC, ACS, CCMHC, CCTP, LMHC, LPC-S, is an assistant professor at The University of Texas at San Antonio. M. Ann Shillingford, PhD, is an associate professor at the University of Central Florida. Lea Herbert is a doctoral student at the University of Central Florida. Correspondence may be addressed to Shainna Ali, 3222 Corrine Drive, Orlando, FL 32803, hello@drshainna.com.

May 10, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 1

Warren Wright, Jennifer Hatchett Stover, Kathleen Brown-Rice

Racial trauma has become a common topic of discussion in professional counseling. This concept is also known as race-based traumatic stress, and it addresses how racially motivated incidents impede emotional and mental health for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). Research about this topic and strategies to reduce its impact are substantial in the field of psychology. However, little research about racial trauma has been published in the counseling literature. The intent of this paper is to provide an in-depth perspective of racial trauma and its impact on BIPOC to enhance professional counselors’ understanding. Strategies for professional counselors to integrate into their clinical practice are provided. In addition, implications for counselor supervisors and educators are also provided.

Keywords: racial trauma, BIPOC, counseling, professional counselors, clinical practice

The impact of racism on the psychological, emotional, and physical well-being of those subjected to it is no secret. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) has declared racism as a public health issue and threat to the health of minoritized individuals. Similarly, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (2019) reported that 5,155 people were targets of racially motivated hate crimes in 2018: 47.1% of the victims identified as Black/African American, 13% as Hispanic/Latino, 4.1% as American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 3.4% as Asian. Daily experiences of racism for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) can lead to an increase in health complications and mental health disparities (French et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2019). Hemmings and Evans (2018) noted that because of racism, BIPOC communities have limited access to resources, which impacts their quality of education and health care. Thus, racially marginalized communities are susceptible to chronic illnesses and mental health concerns such as diabetes, heart disease, depression, and suicide (Hemmings & Evans, 2018). Furthermore, researchers have found that exposure to racism and discrimination increases levels of stress in the body and can lead to chronic illnesses such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and gastrointestinal issues for people of color (Bernier et al., 2021; Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2015), therefore adversely impacting the livelihood and overall well-being of BIPOC communities.

Racism-related stressors can lead to race-based traumatic stress, also known as racial trauma (Carter, 2007; Comas-Díaz et al., 2019). Racial trauma and race-based traumatic stress occur when there is an experience of direct or indirect racism that leads to psychological and emotional injury for BIPOC. Examples include experiencing microaggressions in the workplace (Sue et al., 2019), witnessing an unarmed Black person being killed by law enforcement (Williams et al., 2018), and being physically attacked because others believe a person’s racialized group is the cause of a global pandemic (e.g., Asian American and Pacific Islanders [AAPIs]; Litam, 2020). There is a substantial amount of literature in the field of psychology related to racism, race-based traumatic stress, and racial trauma (Adames et al., 2023; Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2006; Carter, 2007; Comas-Díaz et al., 2019; French et al., 2020; Helms et al., 2010; Mosley et al., 2021). However, there is little to no research in the counseling profession related to racial trauma. Therefore, this article provides an overview of racial trauma and implications for the counseling profession.

Race-Based Traumatic Stress and Racial Trauma

Racial trauma is the collective stress experienced by BIPOC directly or indirectly due to continuous racially motivated incidents of microaggressions, exclusion, discrimination, and sociopolitical events that create psychological and emotional harm (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019; Comas-Díaz et al., 2019). Race-based traumatic stress is one of the most common interchangeable terms for racial trauma and refers to the stress response and emotional injury that occur after experiencing a racist encounter (Carter, 2007; Williams et al., 2018). Carter (2007), along with other researchers (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019; Helms et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2007, 2016), examined the experiences of BIPOC and the accompanying psychological stress when they experience racism-related incidents. Constant exposure to racially motivated incidents can create and lead to an overwhelming emotional stress response for BIPOC. Bryant-Davis and Ocampo (2005), Hemmings and Evans (2018), and Litam (2020) discussed how racist incidents of physical assaults, verbal attacks, and threats to one’s safety impact a person’s sense of self and can cause a person to present with symptoms of trauma.

It is imperative to note that experiencing racism and presentation of trauma symptoms are not all life threatening. Therefore, racial trauma differs from the traditional diagnosable PTSD criteria as stated in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Although it is not explicitly stated in the DSM-5, racial trauma encompasses racism-related stressors associated with one’s membership in a racialized social group, historical trauma, and continuous exposure to racism-related violence. Consequently, conceptualizing and diagnosing a client that presents to counseling with trauma symptomology that does not fit the criteria for the PTSD diagnosis can be confusing for mental health professionals. Therefore, it is important for professional mental health counselors to be prepared to assess and treat clients who present to counseling with trauma symptomology related to racist incidents.

Impact of Racism and Racial Trauma

Racial trauma could impact a person’s sense of self, pride in culture, and identity (Brown-Rice, 2013; Skewes & Blume, 2019). Skewes and Blume (2019) found that assimilation, exploitation, and forced relocation led to the loss of spiritual and cultural practices for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities. Additionally, Brown-Rice (2013) stated that loss of cultural traditions and native practices creates a sense of confusion and hopelessness for Native American adults. Thus, racialized trauma can lead to a separation of cultural identity and practices. Similarly, Chavez-Dueñas and colleagues (2019) found that racial trauma has increased psychological distress for Latinx immigrant communities because of anti-immigration policies, opposition to assimilation into the American culture, and fear of deportation. Furthermore, racial trauma can lead to psychological concerns such as anxiety, depression, emotional dysregulation, and suicidal ideation (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2020; Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005; Comas-Díaz et al., 2019; French et al., 2020; Hemmings & Evans, 2018). Additionally, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2020) found suicide rates for minoritized communities have increased. Moreover, racial discrimination has been positively correlated with suicidal ideation among African American young adults (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2020).

Racism is consistently prevalent within American schools and continues to be an issue of concern experienced by BIPOC students (Kohli et al., 2017; Merlin, 2017). The experience of trauma coupled with racism and discriminatory practices in education has shown to impart racial disparities among BIPOC students in the areas of academic achievement, employment, and participation in the criminal justice system (Lebron et al., 2015). Black students are underrepresented in advanced courses, are less likely to be college ready, and spend less time in the classroom because of disciplinary practices (United Negro College Fund, 2020). According to a report on school discipline by the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (2018), Black students only account for 18% of preschool enrollment, yet they make up 42% of total suspensions and 3 times more expulsions than their White peers. In addition, Black students are more than twice as likely to be referred to law enforcement and subject to arrest for school-based incidents when compared to their peers (United Negro College Fund, 2020). Furthermore, not only are Black students underrepresented in advanced courses, but they are overrepresented in special education programs and more likely to be identified with a disability (Harper, 2017). Therefore, it is imperative for professional mental health counselors to understand how racial trauma could impact the mental health and well-being of individuals at distinct phases of life span development (e.g., children, college students, etc.).

Currently, racial trauma has been exacerbated by the recent COVID-19 pandemic plaguing the United States and other parts of the world. Liu and Modir (2020) and Fortuna et al. (2020) highlighted the lived experiences within BIPOC communities regarding living in low-income neighborhoods, denial of access to care, and being disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 virus. Black Americans accounted for 34% of confirmed cases in the United States, followed by Latinos at 20%–25% of cases (Fortuna et al., 2020). This demonstrates that health disparities coupled with racism could impact the physical well-being of BIPOC. Racism-related stress impacts the emotional and physical health of BIPOC communities. This includes sense of self (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019), culture identity (Skewes & Blume, 2019), and overall wellness (Litam, 2020). Healing racial trauma requires professional mental health counselors working with BIPOC individuals to consider sociocultural factors such as systemic racism, oppression of marginalized communities, and cultural trauma.

Implications for Professional Counselors

The counseling profession highlights the importance of assessment competency as stated in the American Counseling Association (ACA) Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014; e.g., Standard E.5.c: Historical and Social Prejudices in the Diagnosis of Pathology) and the 2016 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP, 2015) Standards (e.g., Assessment and Testing). In addition, the 2016 CACREP standards emphasized the importance of social and cultural diversity, highlighting strategies and techniques to identify and eliminate barriers of oppression and discrimination (CACREP, 2015). Because racial trauma is invasive and harmful for BIPOC individuals and communities, understanding its impact on psychological and emotional well-being is imperative for all mental health professionals in their respective roles. Thus, counselors must be prepared to provide culturally responsive care to BIPOC individuals who have experienced racism-related trauma.

Licensed Professional Mental Health Counselors

Assessing for racial trauma is of utmost importance when conceptualizing and creating a treatment plan for BIPOC clients. It is imperative for counselors to become familiar with assessments and clinical interventions to inform their approach to treating racial trauma. Williams and colleagues (2018) proposed the UConn Racial/Ethnic Stress and Trauma Survey (UnRESTS) to assist mental health professionals in their case conceptualizations and treatment planning when racial trauma is present in BIPOC individuals. The UnRESTS is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview that is beneficial in case conceptualization to determine the multiple experiences of racism for the client. The interview comprises 6 sections: introduction of the interview, racial and ethnic identity development, experiences of direct overt racism, experiences of racism by loved ones, experiences of vicarious racism, and experiences of covert racism (Williams et al., 2018). Even though this survey is like the DSM-5 Cultural Formulations Interview (APA, 2013) and helps the counselor determine if the client’s symptomology fits criteria for PTSD, it should not be the only assessment tool used to determine a diagnosis of PTSD. Additionally, this interview tends to be lengthy in time; therefore, counselors should consider completing this interview within the first and second sessions. This assessment along with other clinical approaches could be beneficial to understanding the traumatic responses of clients impacted by racism.

Several BIPOC scholars have offered models, theories, and frameworks to heal racial trauma (Adames et al., 2023; Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2006; French et al., 2020; Mosley et al., 2021). Counselors must position themselves to consider approaches that go beyond Eurocentric theories and models when addressing and treating racial trauma. These include being critical of sociopolitical structures, awareness of one’s own racial identity, and comfort level when broaching the topic of racism and racial trauma (Adames et al., 2023; Thrower et al., 2020). For instance, Bryant-Davis and Ocampo (2006) provided a foundation for treating racial trauma in a safe environment. Their therapeutic approach included acknowledgment, grieving/mourning loss, analyzing internalized shame and racism, and centering coping and resistance strategies. Supporting clients to name oppressive systems, process their experiences of racist incidents, and deconstruct self-blame narratives because of racism fosters liberation and healing for BIPOC clients who have experienced racism-related stress and trauma (Adames et al., 2023). Thus, counselors must be empathetic and take initiative in helping BIPOC clients shift the focus on harm from self-blame to external oppressive factors. This promotes a strong sense of self and healthy living for BIPOC clients.

Similarly, models offered by Chavez-Dueñas et al. (2019), French et al. (2020), Mosley et al. (2021), and Adames et al. (2023) center the well-being and collective power of BIPOC communities. For example, critical consciousness, Black Psychology, Liberation Psychology, and trauma-informed care influenced these approaches to address racism-related stress and trauma. Subsequently, French and colleagues’ (2020) Radical Healing Framework centers justice and overall wellness for BIPOC communities. This is the intentional practice of going beyond just coping with racism to focus on healing wherein a client can thrive by connecting to community and engaging in resistance against racism-related stressors (French et al., 2020). Thus, helping clients to engage in activism and utilize microinterventions to disarm and address microaggressions can empower clients (Mosley et al., 2021; Sue et al., 2019). Microinterventions help equip clients with tools they can implement to assert boundaries and communicate disagreement with microaggressions (Litam, 2020; Sue et al., 2019). However, counselors must remember that safety is a priority when supporting clients in confronting perpetrators of racism-related trauma (Litam, 2020). Therefore, role-plays in counseling sessions could provide the space and time to strategize when it is and is not appropriate to confront perpetrators of microaggressions.

Utilizing these approaches with clients fosters validation and affirmation of their experiences. Failure to acknowledge and attend to the symptoms and experiences of racism-related stress and trauma can maintain psychological distress for BIPOC clients (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019). Furthermore, helping clients process the positive messages they received about their racial identity throughout their life can reinforce these approaches (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019). Thus, counselors should use a strength-based approach when supporting BIPOC clients in healing from racism-related stress and trauma. In addition, consultation with colleagues, supervisors, and counselor educators can provide support and a space to implement best practices to provide the most effective care for BIPOC individuals who have experienced racial trauma, rendering positive mental health outcomes.

Professional School Counselors

Professional school counselors should demonstrate cultural competence and serve as essential stakeholders in identifying and supporting clients impacted by trauma (ACA, 2014; American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2016; Parikh-Foxx et al., 2020). ASCA specifies these responsibilities and obligations in their ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors (ASCA, 2022). These principles serve as a framework in which professional values, norms, and behaviors are referenced. Further, school counselors can help to identify, respond to, and prevent incidents of racism and bias, as well as become resources to help promote systemic change and advocate for social justice within the educational setting (ASCA, 2020). However, ASCA (2021) recognizes the lack of racial literacy and the inherent gaps between racial equity and equality within education, petitioning for school counselors to continually pursue cultural competency and work toward mitigating the negative effects of racism and bias. Subsequently, ASCA guidelines encourage school counselors to examine their own biases and consult with community professionals to engage in immersive experiences and provide support to students and families who have experienced racial trauma or have been negatively impacted by racism (ASCA, 2021; Atkins & Oglesby, 2019; Levy & Adjapong, 2020).

As facilitators of change, school counselors can help to create environments that are safe and inclusive for both students and educators. One approach is to discuss issues of racial trauma using trauma-informed and restorative practices (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2018). Trauma-informed practices take on a phenomenological approach, seeking to identify, understand, and address the meaning behind student behaviors and experiences (Steane, 2019). Additionally, restorative practices not only provide an alternative to harsh disciplinary practices, but also create spaces for individuals to share their own perspectives without fear of judgement or ridicule, while being open to listening and validating the values, experiences, and perspectives of others (NCTSN, 2018; United Negro College Fund, 2020). Moreover, Anderson and Stevenson (2019) posited the concept of racial socialization, which is the intentional communication about the system of racism, racial identity, and experiences between parents and their children and others within the family system with similar racial and ethnic identities. Racial socialization aids in the development of a positive sense of self and cultural identity as mitigating forces to racial trauma. Further, the Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory (RECAST) helps families and youth prepare for, discuss, and respond to racially stressful experiences appropriately (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019). Thus, this can also prepare students to strategize how to respond to incidents of racism in the school environment.

It is evident that incidents of school-based racism are perpetuated by several factors and continue to negatively impact student performance and affect the health and well-being of BIPOC students (Kohli et al., 2017). The implementation of culturally responsive pedagogy can be used to mitigate this impact, increase academic success, and help students maintain cultural integrity (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Lebron et al., 2015). Counseling professionals can support this effort by engaging in training and professional development to understand racism and its impact on culturally diverse students and by facilitating necessary discussions that help to equip stakeholders with tools to adequately address discrimination, racism, and race-based trauma (NCTSN, 2018; Pietrantoni, 2017).

Counselor Supervisors

The ACA Code of Ethics (2014; e.g., Section F: Supervision, Teaching, and Training) highlights the importance of counselor supervision for the development of counselors seeking licensure as independent mental health practitioners. Additionally, counselor supervision enhances a supervisee’s knowledge, skills, and ability to work with diverse clients (ACA, 2014). Therefore, counselor supervisors and their supervisees should be aware of racial trauma and the effects it could have on BIPOC clients. Pieterse (2018) posited guidelines and considerations for supervisors to follow when attending to racial trauma concerns in clinical supervision. Specifically, supervisors must be reflective of their own racial identity, understand how to assess for racial trauma, and implement effective clinical interventions for their supervisees’ clients impacted by racial trauma (Pieterse, 2018).