May 22, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 1

Kaprea F. Johnson, Alexandra Gantt-Howrey, Bisola E. Duyile, Lauren B. Robins, Natese Dockery

Career counselors practicing in rural communities must understand and address social determinants of mental health (SDOMH). This conceptual article details the relationships between SDOMH domains and employment and provides evidence-based recommendations for integrating SDOMH into practice through a rural community health and well-being framework. Description of the adaptation of the framework for career counselors in rural communities, SDOMH assessment strategies and tools, and workflow adjustments are included. Conclusions suggest next steps for practice and research.

Keywords: social determinants of mental health, career counselors, rural communities, health and well-being framework, assessment

Career counselors in rural communities address standard employment needs of the population, but they also must be aware of the socioeconomic circumstances that impact their community’s mental health and, in return, employment. Such socioeconomic factors are termed the social determinants of mental health (SDOMH). SDOMH are nonclinical psychosocial and socioeconomic circumstances that contribute to mental health outcomes (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], n.d.). Healthy People 2030, a government initiative to promote health and well-being, describes a five-domain framework of SDOMH which includes: economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (ODPHP, n.d.). Collectively, SDOMH can disrupt overall well-being and have a cyclical relationship with employment. For example, in rural communities, minimal access to public transportation may make sustaining employment difficult, which can then impact health insurance. Without insurance, a person loses access to health care; with unmet health care needs, a person who is unwell and without access to treatment has less opportunity for employment. Thus, understanding and addressing SDOMH is critically important for career counselors working in rural and other underserved communities (Pope, 2011). This conceptual paper will define SDOMH, introduce a theoretical framework for addressing SDOMH, provide evidence-based recommendations for assessment and treatment, and conclude with national resources to support career counselors in rural communities as they incorporate addressing SDOMH into their work.

Rural Communities, Employment, and Career Counselors

The U.S. Census Bureau considers rural communities as a group of people, counties, and housing outside of an urban area. More specifically, the Office of Management and Budget defines rural as areas with an urban core population of fewer than 50,000 people (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2017). After the 2010 Census, it was estimated that approximately 15% of the population lives in rural communities (Health Resources & Services Administration, 2017). Rural communities experience higher rates of unemployment and poverty, and residents are therefore more likely to live below the poverty line (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2014). This is largely rooted in the fact that rural communities experience underdevelopment, economic decline, and neglect (Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016). Economic focus in rural environments typically centers around agriculture, rather than technological advancement (Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016). This contributes in part to a dearth of economic resources and thereby to increased unemployment and poverty and reduced health and well-being outcomes (Bradshaw, 2007; Brassington, 2011; Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016).

According to research conducted by the USDA, the unemployment rate in rural communities steadily declined for approximately 10 years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic; in September of 2019, the rural unemployment rate was 3.5% (Dobis et al., 2021). However, unemployment in rural communities reached 13.6% in April 2020, with unemployment disparately affecting those in more impoverished communities (Dobis et al., 2021). The role and goal of the career counselor is to help individuals in a specific community obtain or retain employment (Landon et al., 2019). For example, career counselors start the counseling process by systematically assessing clients’ needs, qualifications, and job aspirations. They provide career planning services and effective job search strategies. They help with résumé writing, interview preparations, skill development, and training opportunities (Amundson, 1993). Further, career counselors provide case management services by tracking and monitoring their clients’ progress. They record client information, document counseling sessions, track job applications, and survey employment outcomes (Amundson, 1993). Through tailored support, the career counselor works with the client throughout the life span to support the search for and maintaining of employment, while building client resilience and feelings of empowerment along the way.

However, rural communities have limited employment options and self-employment opportunities, which makes the role of the career counselor difficult in rural settings. Individuals in rural communities seeking employment may find it difficult to trust an outside counselor, and they may experience limited or no access to mental health services, health care practitioners, and transportation services, thereby negatively impacting their ability to participate effectively in the employment process (Landon et al., 2019). Career counselors in rural settings must develop a broader range of skills and connections to better serve their clients. These inequities experienced in rural settings reflect SDOMH and are factors which interfere with the role of the career counselor.

Social Determinants of Mental Health and Employment

SDOMH are the nonmedical factors shaped by the unequal distribution of power, privilege, and resources that influence the health outcomes of individuals and communities (World Health Organization, 2014). SDOMH concern the environmental living conditions that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). In the Healthy People 2030 framework, the ODPHP (n.d.) defined social determinants of health (SDOH) through five primary domains: Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context. These five domains are important to understand within the context of employment. In the Economic Stability domain, employment is the most pertinent issue (ODPHP, n.d.), as a lack of employment typically influences both mental and physical health (Norström et al., 2019). A few distinct factors related to economic stability and employment include job security, work environment, monetary factors (e.g., pay), and the demands of the job (ODPHP, n.d.). For example, in rural communities, agriculture is a significant source of employment for individuals. However, this source of income is seemingly unstable, as farming and agriculture are mostly dependent on the season (Liebman, 2010). In the Education Access and Quality domain, enrollment in higher education or holding a higher education degree has been found to have a positive impact on employment, as well as yielding more positive overall health outcomes and optimal well-being (ODPHP, n.d.; USDA, 2017). For adults living in rural communities, unemployment rates are higher for those with lower education attainment, further supporting the connection between education and employment (USDA, 2017). Regarding the Health Care Access and Quality domain—specifically in rural communities—factors such as proximity to hospitals, lack of insurance, and the overall cost of health care can reduce accessibility. Health care, especially higher-quality health care, aids in preventing disease and improving individuals’ quality of life (ODPHP, n.d.). However, inadequate health care leads to higher rates of disease, which have a direct impact on individuals’ ability to sustain employment, due to factors such as missing work because of illness or having to travel further to receive health care (Dueñas et al., 2016).

Ability to travel is also a cause for concern in rural communities and is closely related to the Neighborhood and Built Environment domain. Healthy People 2030 proposed various objectives related to neighborhood and built environment, with one being to increase access to mass transit (ODPHP, n.d.). It is apparent that a lack of reliable transportation is directly tied to unemployment, especially in rural communities due to distance and limited accessibility (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2019). Public transportation carries many noteworthy benefits, such as reducing air pollution, being inexpensive compared to purchasing a car, minimizing the cost of fuel and upkeep for personal vehicles, and increased convenience. Although these positive aspects of public transportation are ideal, individuals living in rural communities may not be able to reap these benefits due to the lack of public transportation in these areas, perhaps also limiting employment options (Shoup & Homa, 2010; U.S. Department of Transportation, 2019).

Lastly, the fifth domain, Social and Community Context, is interrelated with employment, as it tends to have a significant impact on workplace conditions, influences individuals’ overall mental and physical health, and can hinder growth and development (Norström et al., 2019). Additionally, social cohesion and adequate support in communities can be leveraged to locate and obtain employment and other helpful resources; however, this often falls short in rural communities. For example, in rural communities, the inability to secure gainful employment is notably linked to geographical disparities, such as those within the Neighborhood and Built Environment SDOH domain. Examples of such geographic disparities which affect employment include limited or nonexistent options for public transportation, a lack of available local jobs, and a lack of childcare facilities for use by working parents. Rural communities also often experience a lack of resources to improve the employment outlook and overall well-being of their population (Bradshaw, 2007; Dwyer & Sanchez, 2016). In addition, structurally, it has been observed that economic resources tend to cluster or aggregate together. For example, businesses that have been successful in a community invite and attract more businesses, thus pulling resources away from rural communities that might not have such a history of business success. Meanwhile, communities that are left behind experience economic restructuring and delays in receiving new technologies, leading to fewer employment opportunities (Bradshaw, 2007; Landon et al., 2019). Thus, providing employment or vocational services in rural America can be particularly challenging.

Furthermore, unemployment, poverty, and mental health concerns are inextricably linked. When career counselors uncover and address these factors in rural America, they must consider the surplus of needed services and resources to systemically address interrelated issues. To be intentional, career counselors practicing in rural communities should consider using a theoretical foundation that provides direction for action on the SDOMH which impact their clients’ lives and ability to be gainfully employed. The Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework (Annis et al., 2004) is a framework that would be exceedingly helpful in this pursuit.

Theoretical Framework for Action: Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework

Rural communities make up over 20% of the population and are often classified by a lack of necessary resources, lower levels of education, and persistent economic inequities (Hughes et al., 2019; Mohatt et al., 2006). Although they face many challenges, individuals in rural communities have been found to be resilient, especially when the proper resources are available (Annis et al., 2004). Application of a theoretical framework to practice centered on the unique needs of rural communities is important in addressing SDOMH through career counseling. The Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework (Annis et al., 2004) strategically builds upon community resiliency and identifies economic, social, and environmental factors which are seen as essential components of health in rural communities. This framework also implores career counselors to consider how SDOMH indicators impact the community as a whole as well as individual people. For example, the framework provides specific areas for increased career counselor awareness and action: health, safety and security, economics, education, environment, community infrastructure and processes, recreation, social support and cohesion, and the overall population. These specific areas for rural communities are within the SDOMH domains, but emphasis is placed on recognition of the specific areas within the SDOMH domains that have the greatest impact on the community.

This comprehensive framework centers the needs of rural communities and provides direction for assessing and addressing SDOMH that impact employment and overall well-being. This framework will assist in uncovering employment issues and barriers faced by individuals within rural communities. Using this framework to assess SDOMH conditions (e.g., economic, social, environmental) will aid in developing employment and mental health interventions that are socially conscious and address root causes of unemployment and poor mental health. Overall, this framework provides a model for assessing and addressing SDOMH in rural communities.

Adaptation for Career Counselors

Career counselors in rural communities who wish to use the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework for practice should consider doing the following: (a) increasing their awareness and understanding of SDOMH and the framework, (b) increasing their understanding of the specific community needs outlined by the framework, and (c) assessing the values and needs of the community. However, because the framework is primarily focused on community-level indicators of need, career counselors will need to adapt what they learn about the community to inform their practice with individual community members. The role of the career counselor is multifaceted; thus, career counselors can engage various aspects of their role, such as listener, leader, and evaluator, in their advocacy efforts.

To begin this process of learning about community and individual needs, Annis et al. (2004) suggested the importance of listening. For example, based on the community-level indicators of need, career counselors can assess individual clients for their unmet needs within those specific areas. By understanding how members of the community are experiencing indicators such as health, recreation, social support, transportation, and resources, career counselors will become better equipped to understand and address issues that are impacting their clients’ ability to obtain and maintain employment. Beyond the use of assessments, this framework equips career counselors to broach important conversations about social needs (Andermann, 2016) with their clients, to inform potential connection with community resources. These conversations may include explicit discussion about particular SDOMH challenges (e.g., education, safety, access to affordable childcare), as well as about the client’s sense of belonging, or lack thereof, within their community. These conversations should allow for increased understanding and rapport building through genuine listening and empathy (Annis et al., 2004; Covey, 1989).

Finally, the framework implores career counselors to advocate with and for individuals within their rural community to provide equitable employment opportunities (Crumb et al., 2019). Such advocacy may take place through connection with local rural community leaders, who may have power to alter or increase the distribution of certain resources within the community setting. For example, a career counselor may advocate on behalf of their clients to the local county board of commissioners for increased budget toward affordable transportation access within that county, thereby broadening clients’ access to job opportunities. Advocacy with local leaders outside of government might include collaboration with community college administrators for provision of additional support for working adults and parents who wish to return to school, such as more evening course options, advisor support, or readily available information on scholarships. Again, considering the aforementioned roles career counselors may have (e.g., leader, evaluator), career counselors may also consider further training in program evaluation—or collaboration with those who have such training—to better understand the efficacy of their community partnerships, referrals, and other advocacy-related efforts made toward supporting clients’ SDOMH.

Assessing and Addressing Social Determinants of Mental Health

As noted earlier, SDOMH are inextricably linked to employment, which means career counselors in rural communities must acknowledge these challenges and seek to address these issues with their clients. However, researchers have also highlighted the importance of considering both facilitators and barriers to addressing SDOMH challenges (Browne et al., 2021). In a qualitative case study of staff at a community health center and hospital, participants identified practical facilitators of SDOMH response, including community collaboration and support from leadership, as well as barriers such as time limitations and lack of resources (Browne et al., 2021). As career counselors hold similar client outcome goals as community mental health providers, they can take these findings into consideration when determining how to best respond to clients’ SDOMH challenges through attention to opportunities for collaboration with community leaders (e.g., religious leaders, politicians) and resources within the community (e.g., food banks, health care providers). Another study highlighted the importance of collaboration, partnerships with local agencies, and understanding the role of the counselor in SDOMH response (Johnson & Brookover, 2021; Robins et al., 2022). With these findings in mind, career counselors in rural communities are well positioned to assess for and address SDOMH challenges faced by their clients (Crucil & Amundson, 2017; Tang et al., 2021) through individual-level action (i.e., counseling) and systems-level advocacy action.

Systems-Level Advocacy Through Assessment

To effectively engage in systems-level advocacy, it is important for career counselors to recognize and understand the needs of their rural communities. When using the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework in practice, it is important to complete an assessment of the rural health of one’s community. Ryan-Nicholls and Racher (2004) purport that it is imperative to assess rural health within five categories: health status, health determinants, health behavior, health resources, and health service utilization. Counselors may consider these items when assessing the needs of their clients in rural communities, as these items provide a basis for assessment of other health factors, such as indicators of community health (e.g., environment and lifestyle) and economic well-being, and provide a foundation for systems-level advocacy and planning. This level of action focuses on improving the lives of the entire community through strategic advocacy efforts that improve population health and well-being (Ryan-Nicholls & Racher, 2004). A career counselor engaged at this level might focus their energy on advocating for increased economic development in their rural community, livable wages, universal health care, immigration issues, employment discrimination legislation, and other employment-related issues that impact the community directly or indirectly. Additionally, a career counselor may address client self-advocacy and utilize empowerment approaches to increase the voices of community members and their clients as related to work and employment needs.

In connection with this framework (Annis et al., 2004), career counselors can utilize this broader community-level assessment to inform specific points of advocacy. As an example, Annis et al. (2004) provided a sample form that may be utilized to collect community data on alcohol consumption (p. 79). Upon noting concern from individual clients on alcohol consumption, a career counselor may collaborate with public health professionals, for instance, to collect such data from the local community. Annis et al. encourage consideration of the implications for such findings, as well as opportunities for follow-up. After determining a need in the community for support regarding high alcohol consumption, the career counselor may utilize the framework to consider points of community resilience, including existing supports, attitudes about alcohol consumption, existing resources, and any actions the community is already taking in this area. Overall, assessment through the context suggested by Ryan-Nicholls and Racher (2004) may yield individual and community data to inform action to address SDOMH challenges through Annis et al.’s (2004) framework.

Individual-Level Action Through Assessment

When a client seeks services from a career counselor, the relationship centers on exploration and evaluation of the client’s education, training, work history, interests, skills, personality, and career goals. Through engaging with the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework, the career counselor might also examine the SDOMH facilitators and barriers that impact a client’s employment goals. To address employment and SDOMH, a career counselor must understand the community-level needs (i.e., systems approach) and the individual needs of their clients; for these goals, one strategy is to use assessments. There are various assessment tools that career counselors may find helpful, including the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE; National Association of Community Health Centers, 2017), an SDOH assessment tool purposed to empower professionals to not only understand their clients more holistically through assessment, but to better meet clients’ needs through the use of such information. The PRAPARE assessment tool includes questions related to four domains: Personal Characteristics, Family and Home, Money and Resources, and Social and Emotional Health. PRAPARE emphasizes the importance of assessing SDOMH needs of clients in order for providers to “define and document the complexity of their patients; transform care with integrated services and community partnerships to meet the needs of their patients; demonstrate the value they bring to patients, communities, and payers; and advocate for change in their communities” (https://prapare.org/). There are several benefits of using the PRAPARE assessment tool, such as it being free of charge, having a website linked to the tool with an “actionable toolkit and resources,’’ and being evidence-based. Barriers to using PRAPARE include that it is a long assessment tool that clients must complete in-office, which may slow workflow.

Another SDOH assessment tool is the WellRx Questionnaire (Page-Reeves et al., 2016). The WellRx Questionnaire is an 11-item screening tool that gathers information on various SDOMH, like food security, access to transportation, employment, and education. Participants are to answer “yes” or “no” to each item on the questionnaire. According to Page-Reeves and colleagues (2016), the WellRx Questionnaire provides a feasible means of assessing patients’ social needs and thereby addressing those needs. Benefits to using the WellRx include that it is free of cost, questions are at a 4th-grade reading level, and it can typically be completed by a client individually without the help of a professional. A potential barrier is that it does not assess a wide range of SDOMH challenges. Lastly, Andermann (2018) conducted a scoping review of social needs screening tools and found that the focus on such screening has increased over time. Andermann suggested that health care workers take advantage of the existing means of assessment, and made a number of specific resource recommendations, such as the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (2019) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2022).

Addressing SDOMH Through Action

Documenting and defining the needs of clients through assessment is the first step in addressing SDOMH. The next step is taking action through an integrated career counseling approach. An integrated approach may include consistent collaboration with other professionals, like medical doctors, nurse practitioners, social workers, probation officers, or case managers. Additionally, scholars like Andermann (2016) suggest integrated efforts such as ensuring social challenges are included in client records and shared with other professionals to best support care. For “particularly isolated and hard-to-reach patients . . . [actions like] assertive outreach, patient tracking and individual case managers” may be helpful (para. 19). Another practical suggestion for beginning to address clients’ SDOMH challenges is adding an SDOMH assessment tool or specific SDOMH questions to an intake form that the client completes independently or during the intake session. Selection of specific questions can be derived from the data that displays community-level needs (e.g., systems-level advocacy through assessment). For example, if a community-level assessment found that public transportation was lacking, then transportation might be an important assessment question on the SDOMH screener.

Another consideration specific for career counselors is that counselors are obligated by their code of ethics to take appropriate action based on assessment results (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014, Section E.2.b.). Appropriate action can include consultation and collaboration with other professionals within and outside of counseling and/or advocacy to address the SDOMH need. After establishing the need through assessment, it is important for the career counselor to support the client in understanding system-level challenges and to work to address SDOMH issues while simultaneously supporting employment needs. For example, a career counselor who determines that their client is struggling with food insecurity might address this issue in several ways. At the individual level, the counselor might print resources for local food pantries, assist the client in applying for SNAP benefits, and counsel the client on resources within the community to access food. They could establish a small food pantry within the office, collaborate with local restaurants to receive pre-packaged food that might otherwise be disposed of, or consult with local food pantries and free food kitchens to establish a mobile pantry and kitchen. At the systems level, a career counselor may build partnerships with local farmers to increase locations where fresh fruits and vegetables are available for little or no cost.

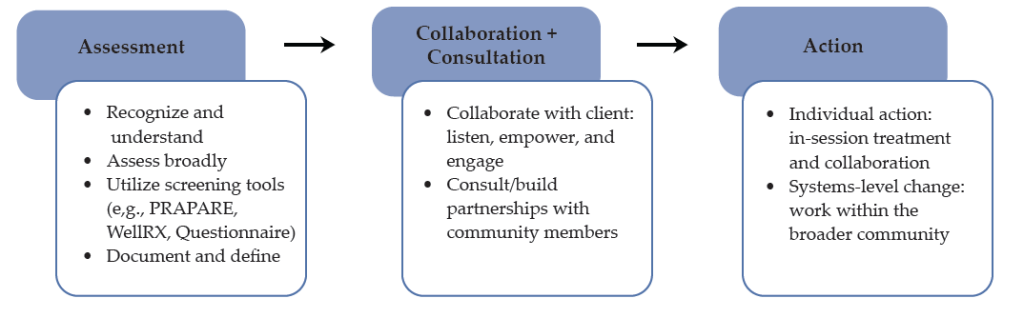

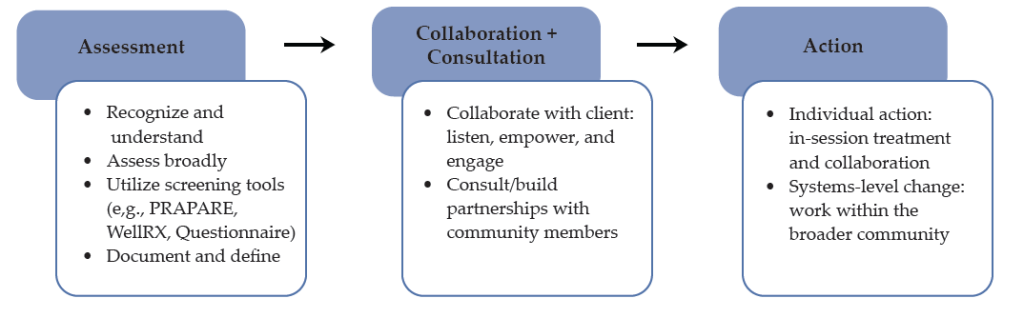

Collaboration and consultation are imperative to addressing the complex needs of clients in rural communities who are both seeking career counseling and challenged by SDOMH issues. For example, as noted earlier, health care access and quality are major disruptors of employment, and addressing these challenges will afford benefits for employment. The career counselor can consider using interprofessional collaboration and telehealth to support the health care needs of their rural clients (Johnson & Mahan, 2020). Interprofessional collaboration is a practice in which health care providers from two or more professional backgrounds interact and practice with the client at the center of care (Prentice et al., 2015). Using telehealth, the distribution of health-related services via telecommunication technologies is a useful strategy to support the health care needs of persons in rural communities. A career counselor can address health care access through telehealth in several ways, including education (e.g., introduce their client to telehealth; assist them in understanding the technology), telehealth (e.g., provide the telecommunication equipment in the office), and collaborative partnership (e.g., use a portion of the career counseling session to assist the client in connecting with health care providers using distance technology). As a collaborative partner in addressing health care access and quality, the career counselor can also use future sessions to follow up with the client on their experience with telehealth and, if needed, assist them in connecting to other health care providers. Figure 1 provides a visual for conceptualizing how career counselors may navigate the SDOMH needs of their clients, from assessment to action.

Figure 1

Working to Address Clients’ SDOMH Needs

Lastly, in the work of addressing SDOMH and employment, counselors should be aware of local, state, and national resources. Local and state resources are unique to every state but have similar purposes which include disseminating information on local resources and initiatives and providing public services that address SDOMH (e.g., food banks, public programs). National resources that are accessible to every community include 211 and the “findhelp.org” website. The Federal Communications Commission designated 211 as a national number in the United States that anyone can call for information and referrals to social services and other assistance. The services provided by 211 are confidential and free, available 24/7, and help connect people in the United States to essential community services. Moreover, the “findhelp.org” website is designed to help people search and connect with social care support based on their ZIP Code.

Integrating career counseling and social care support in rural communities is a strategy to facilitate the readiness of clients for work and the sustainability of employment for clients because basic needs are met or being addressed. While every rural community is unique, the foundation of understanding both systemic and individual SDOMH needs—and addressing those needs through strategic partnerships and individual counseling, as well as advocacy—is important in every rural community and to the success of any career counseling endeavor.

Discussion

In rural communities, career counselors hold a significant role. They are tasked with aiding individuals with employment needs; they may often address mental health concerns, and while doing so, it is important for them to be aware of and prepared to address SDOMH. Career counselors can gain more insight into issues related to SDOMH through consultation, collaboration, and advocacy, which should all be a part of the repertoire of a rural career counselor. The use of theoretical frameworks such as the Rural Community Health and Well-Being Framework (Racher et al., 2004) provides direction for career counselors seeking to understand the systemic issues impacting employment access and opportunities in the community, as well as direction for intervention. This framework will assist in identifying and minimizing barriers to employment that may exist within rural communities. More specifically, this framework will help to uncover SDOMH challenges that exist in the community and serve as barriers to well-being and employment and provide direction for advocating for resources necessary for equitable work opportunities and environments. Being that individuals in rural America experience various barriers that have huge impacts on their lives, such a guide for career counselors is essential.

Lastly, addressing SDOMH within career counseling is a social justice issue that counselors should address (ACA, 2014; Crucil & Amundson, 2017; Ratts et al., 2016). The Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC; Ratts et al., 2016) serve as a guide for counselors to address social justice issues and were endorsed by the ACA in 2015. Like the aforementioned framework and empirically based suggestions, the MSJCC includes four areas of competence: counselor self-awareness, client worldview, counseling relationship, and counseling and advocacy interventions. The authors of the MSJCC also implore counselors to consider “attitudes and beliefs, knowledge, skills, and action,” and suggest that competent counselors are aware of the experiences of marginalized clients (Ratts et al., 2016; p. 3). Thus, career counselors’ efforts to assess and address the individual and systems-based SDOMH challenges faced by their clients is social justice work that career counselors are trained and prepared to address.

Implications

Given this review, there are specific implications for career counselors practicing in rural communities, counselor educators training career counselors, and pertinent policy needs.

Practicing Career Counselors

The role of the career counselor often entails identifying employment objectives, goals, and needs for both the job seeker and employer. In addition, the career counselor is responsible for résumé development, teaching job placement and retention skills, providing self-advocacy tips, teaching organizational goal–redefining skills, and many other components (Ysasi et al., 2018). However, providing these services can be difficult when the individuals reside in rural communities because of the SDOMH disparities such as limited available resources, isolation, increased poverty, and decreased educational and employment opportunities (Temkin, 1996).

Therefore, career counselors must actively work to ensure their visibility and accessibility to individuals in rural areas who are seeking employment opportunities. Further, career counselors need to market themselves and their skills to employers and job seekers of rural communities. Consequently, marketing generally entails engaging and developing community partnerships with employers and job seekers, which involves educating individuals unfamiliar with the specific services that career counselors provide. In addition, employers are often interested in services that improve their business (e.g., increase revenue), while job seekers may be searching for skill training to achieve employment goals (Richardson et al., 2010). Therefore, career counselors can enhance service delivery and provide adequate services when they intentionally market their services to the community members.

Furthermore, job insecurity has been linked to mental health concerns like stress and anxiety, financial concerns, and fear of organizational change (Holm & Hovland, 1999). Therefore, career counselors need to be aware of the impact of job insecurity on rural communities and devise strategies to help organizations and workers manage job insecurity. Managing job insecurity of workers in rural organizations could include helping organizations to redefine their present and future goals and commitments made to employees. Organizations could also manage organizational transitions depending on the skills and resources available to affected employees (Holm & Hovland, 1999). Clearly stated organizational objectives, goals, and plans can help employees feel less insecure about their jobs and increase focus on their roles and responsibilities instead of devising means to move out of the community for a better and more secure future. In addition, career counselors in rural communities should be aware of the mental health concerns experienced by employees and job seekers and connect them to available mental health resources.

Counselor Educators

Counselor educators are responsible for the training and development of the next generation of counselors, including career counselors. It will be important for counselor educators to include training on SDOMH, interprofessional collaboration, and telehealth, as these are especially relevant for rural communities ( Johnson & Mahan, 2021; Johnson & Rehfuss, 2021). It is essential to provide adequate time to review and discuss SDOMH in all courses throughout the curriculum (Waters et al., 2022) to ensure the competence of career counselors. To ensure this continuity, counselor educators should advocate for an SDOMH module across the curriculum. This would ensure the inclusion of this content throughout the program, providing ample opportunity for the understanding of SDOMH and how they should be addressed. Career counselors must be prepared to address the complex employment and social health needs with which their clients might present. Without adequate education and training, these will seem much more difficult to address.

Policy

In addressing both SDOMH and employment needs in rural communities, advocating for policy and legislative change is imperative. Lewis et al. (2002) described counselors’ roles in sharing public information as awakening the public to macro-systemic issues related to human dignity and engaging in social/political advocacy, or “influencing public policy in a large, public arena” (p. 2). Thus, career counselors are encouraged to benefit their clients through engaging in advocacy to influence policy at the local, state, and national levels. Similarly, Crucil and Amundson (2017) implore career counselors to engage in the work of influencing politics and policy and suggest awareness as a first step to enacting change through the sharing of information and impacting policy. To develop such awareness, career counselors may begin by reading about SDOMH disparities related specifically to employment issues from reputable sources. For instance, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI; 2014) has published various reports related to such issues, including the informative publication entitled Road to Recovery: Employment and Mental Illness. NAMI (2021) also published a legislative coalition letter written in support of increased SDOH funding to Congress. Career counselors may work to build their own awareness and understanding of the social and political events and influences which impact their clients, building toward eventual action in this realm.

Moreover, regarding policy change, researchers have suggested career counselors should be aware of and actively engaged in policy efforts (Crucil & Amundson, 2017; Watts, 2000). Watts (2000) described public policy considering career development as including four distinct roles: legislation, remuneration, exhortation, and regulation. Watts described these roles in detail and implored career counselors to influence these policy processes by seeking the support of interest groups and communicating with policy makers. Again, career counselors can work individually and within their own communities to increase their awareness and knowledge of policies and their impact. They can work toward influencing policies at the state and national levels to improve the accessibility and existence of important social programs and resources.

Conclusion

Career counselors in rural communities have a responsibility to acknowledge and address SDOMH challenges that are disproportionately impacting their clients. Collaboration, consultation, counseling framed through the lens of SDOMH, and advocacy appear to be strategies to support the employment needs of individuals and the rural community. Employment services in rural communities must be framed through a socially conscious (e.g., aware of the SDOMH systemic issues), action-oriented (e.g., prepared to engage in advocacy), and resiliency-focused lens that provides tailored individual services while simultaneously addressing systemic issues.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/2014-code-of-ethics-finaladdress.pdf

Amundson, N. E. (1993). Mattering: A foundation for employment counseling and training. Journal of Employment Counseling, 30(4), 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.1993.tb00173.x

Andermann, A. (2016). Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: A framework for health professionals. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188(17–18), E474–E483. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160177

Andermann, A. (2018). Screening for social determinants of health in clinical care: Moving from the margins to the mainstream. Public Health Reviews, 39(1), 1–17.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0094-7

Annis, R. C., Racher, F., & Beattie, M. (Eds.). (2004). Rural community health and well-being: A guide to action. Rural Development Institute. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242551842_Rural_Community_Health_and_Well-Being_A_Guide_to_Action

Bradshaw, T. K. (2007). Theories of poverty and anti-poverty programs in community development. Community Development, 38(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330709490182

Brassington, I. (2011). What’s wrong with the brain drain? Developing World Bioethics, 12(3), 113–120.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8847.2011.00300.x

Browne, J., Mccurley, J. L., Fung, V., Levy, D. E., Clark, C. R., & Thorndike, A. N. (2021). Addressing social determinants of health identified by systematic screening in a Medicaid accountable care organization: A qualitative study. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132721993651

Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care. (2019). Canadian task force on preventive health care.

https://canadiantaskforce.ca

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). CDC 2020 in review. https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=

https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1229-cdc-2020-review.html

Covey, S. (1989). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Restoring the character ethic. Simon & Schuster.

Crucil, C., & Amundson, N. (2017). Throwing a wrench in the work(s): Using multicultural and social justice competency to develop a social justice–oriented employment counseling toolbox. Journal of Employment Counseling, 54(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/joec.12046

Crumb, L., Haskins, N., & Brown, S. (2019). Integrating social justice advocacy into mental health counseling in rural, impoverished American communities. The Professional Counselor, 9(1), 20–34. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1215753.pdf

Dobis, E. A., Krumel, T. P., Jr., Cromartie, J., Conley, K. L., Sanders, A., & Ortiz, R. (2021). Rural America at a glance: 2021 edition. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102576/eib-230.pdf

Dueñas, M., Ojeda, B., Salazar, A., Mico, J. A., & Failde, I. (2016). A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. Journal of Pain Research, 2016(9), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S105892

Dwyer, R. E., & Sanchez, D. (2016). Population distribution and poverty. In M. J. White (Ed.), International handbook of migration and population distribution (pp. 485–504). Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7282-2

Health Resources and Services Administration. (2017). Defining rural population. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html

Holm, S., & Hovland, J. (1999). Waiting for the other shoe to drop: Help for the job-insecure employee. Journal of Employment Counseling, 36(4), 156–166.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.1999.tb01018.x

Hughes, M. C., Gorman, J. M., Ren, Y., Khalid, S., & Clayton, C. (2019). Increasing access to rural mental health care using hybrid care that includes telepsychiatry. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 43(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000110

Johnson, K. F., & Brookover, D. L. (2021). School counselors’ knowledge, actions, and recommendations for addressing social determinants of health with students, families, and in communities. Professional School Counseling, 25(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20985847

Johnson, K. F., & Mahan, L. B. (2020). Interprofessional collaboration and telehealth: Useful strategies for family counselors in rural and underserved areas. The Family Journal, 28(3), 215–224.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720934378

Johnson, K. F., & Rehfuss, M. (2021). Telehealth interprofessional education: Benefits, desires, and concerns of counselor trainees. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 16(1), 15–30.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1751766

Johnson, K. F., & Robins, L. B. (2021). Counselor educators’ experiences and techniques teaching about social-health inequities. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 14(4), 1–25. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol14/iss4/7

Landon, T., Connor, A., McKnight-Lizotte, M., & Peña, J. (2019). Rehabilitation counseling in rural settings: A phenomenological study on barriers and supports. Journal of Rehabilitation, 85(2), 47–57. https://bit.ly/4cvWSoT

Lewis, J., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. L. (2002). ACA advocacy competencies. http://www.counseling.org/Resources/Competencies/Advocacy_Competencies.pdf

Liebman, A. K., & Augustave, W. (2010). Agricultural health and safety: Incorporating the worker perspective. Journal of Agromedicine, 15(3), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924x.2010.486333

Mohatt, D. F., Bradley, M. M., Adams, S. J., & Morris, C. D. (2006). Mental health and rural America: 1994-2005. An overview and annotated bibliography. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED591902

National Alliance on Mental Health. (2014). Road to recovery: Employment and mental illness. https://nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/RoadtoRecovery

National Alliance on Mental Health. (2021, April 8). Letter to congressional leadership. https://www.nami.org/getattachment/c3b797bf-5116-457f-ada9-b6b6f1f6adfb/Letter-to-Congressional-Committee-Leadership-on-So

National Association of Community Health Centers. (2017). PRAPARE. https://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare

Norström, F., Waenerlund, A.-K., Lindholm, L., Nygren, R., Sahlén, K.-G., & Brydsten, A. (2019). Does unemployment contribute to poorer health-related quality of life among Swedish adults? BMC Public Health, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6825-y

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Healthy People 2030: Social determinants of health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

Page-Reeves, J., Kaufman, W., Bleecker, M., Norris, J., McCalmont, K., Ianakieva, V., Ianakieva, D. & Kaufman, A. (2016). Addressing social determinants of health in a clinic setting: The WellRx pilot in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 29(3), 414–418. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150272

Pope, M. (2011). The Career Counseling With Underserved Populations model. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(4), 153–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb01100.x

Prentice, D., Engel, J., Taplay, K., & Stobbe, K. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration: The experience of nursing and medical students’ interprofessional education. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393614560566

Racher, F., Everitt, J., Annis, R., Gfellner, B., Ryan-Nicholls, K., Beattie, M., Gibson, R., & Funk, E. (2004). Rural community health & well-being. In R. Annis, F. Racher, & M. Beattie (Eds.), Rural community health and well-being: A guide to action (pp. 18–37). Rural Development Institute.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Richardson, N., Gosnay, R. M., & Carroll, A. (2010). A quick start guide to social media marketing: High impact low-cost marketing that works. Kogan Page Publishers.

Robins, L. B., Johnson, K. F., Duyile, B., Gantt-Howrey, A., Dockery, N., Robins, S., & Wheeler, N. (2022). Family counselors addressing social determinants of mental health in underserved communities. The Family Journal, 31(2), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807221132799

Ryan-Nicholls, K. D., & Racher, F. E. (2004). Investigating the health of rural communities: Toward framework development. Rural and Remote Health, 4(1), 1–10.

https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.613919155641626

Shoup, L., & Homa, B. (2010). Principles for improving transportation options in rural and small town communities. https://t4america.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/T4-Whitepaper-Rural-and-Small-Town-Communities.pdf

Tang, M., Montgomery, M. L. T., Collins, B., and Jenkins, K. (2021). Integrating career and mental health counseling: Necessity and strategies. Journal of Employment Counseling, 58, 23–35.

https://doi.org/10.1002/joec.12155

Temkin, A. (1996). Creative options for rural employment: A beginning. In N. L. Arnold (Ed.), Self-employment in vocational rehabilitation: Building on lessons from rural America (pp. 61–64). Research and Training Center on Rural Rehabilitation Services.

United States Census Bureau. (2014). 2010-2014 ACS 5-year estimates. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2014/5-year.html

United States Department of Agriculture. (2014). Rural America at a glance: 2014 edition. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=42897

United States Department of Agriculture. (2017). Rural education at a glance, 2017 edition. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/83078/eib-171.pdf

United States Preventive Services Taskforce. (2022). US preventative services taskforce. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf

U.S. Department of Transportation. (2019). Rural public transportation systems. https://www.transportation.gov/mission/health/Rural-Public-Transportation-Systems

Waters, J. M., Gantt, A., Worth, A., Duyile, B., Johnson, K. F., & Mariotto, D. (2022). Motivated but challenged: Counselor educators’ experiences teaching about social determinants of health. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 15(2), 1–30. https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol15/iss2/6

Watts, A. G. (2000). Career development and public policy. Journal of Employment Counseling, 37(2), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2000.tb00824.x

World Health Organization. (2014). Social determinants of mental health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112828/9789241506809_eng.pdf

Ysasi, N. A., Tiro, L., Sprong, M. E., & Kim, B. J. (2018). Marketing vocational rehabilitation services in rural communities. In D. A. Harley, N. A. Ysasi, M. L. Bishop, & A. R. Fleming (Eds.), Disability and vocational rehabilitation in rural settings: Challenges to service delivery (pp. 545–552). Springer.

Kaprea F. Johnson, PhD, LPC, is a professor and Associate Vice Provost for Faculty Development & Recognition at The Ohio State University. Alexandra Gantt-Howrey, PhD, LPC (ID), is an assistant professor at Idaho State University. Bisola E. Duyile, PhD, LPC, CRC, is an assistant professor at Montclair State University. Lauren B. Robins, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor and distance learning coordinator at Old Dominion University. Natese Dockery, MS, NCC, LPC, CSAM, is a licensed professional counselor and doctoral student. Correspondence may be addressed to Kaprea F. Johnson, The Ohio State University, 1945 N. High Street, Columbus, OH 43210, johnson.9545@osu.edu.

May 22, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 1

William B. Lane, Jr., Timothy J. Hakenewerth, Camille D. Frank, Tessa B. Davis-Price, David M. Kleist, Steven J. Moody

Interpretative phenomenological analysis was used to explore the simultaneous supervision experiences of counselors-in-training. Simultaneous supervision is when a supervisee receives clinical supervision from multiple supervisors. Sometimes this supervision includes a university supervisor and a site supervisor. Other times this supervision occurs when a student has multiple sites in one semester and receives supervision at each site. Counselors-in-training described their experiences with simultaneous supervision during the course of their education. Four superordinate themes emerged: making sense of multiple perspectives, orchestrating the process, supervisory relationship dynamics, and personal dispositions and characteristics. Results indicated that counselors-in-training experienced compounded benefits and challenges. Implications for supervisors, supervisees, and counselor education programs are provided.

Keywords: clinical supervision, simultaneous supervision, counselors-in-training, interpretative phenomenological analysis, counselor education

Supervision is a key component of counselor education in programs accredited by the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2015) and an ethical requirement in the ACA Code of Ethics (American Counseling Association, 2014). Supervision of counselors-in-training (CITs) serves the purpose of guiding counselor development, gatekeeping, and, ultimately, ensuring competent client care (Borders et al., 2014). For the present study, we defined simultaneous supervision as a pre-licensure CIT receiving weekly individual or triadic supervision from more than one supervisor over the same time period. At the time of the study, the 2016 CACREP standards required that internship and practicum students receive individual and/or triadic supervision averaging 1 hour per week throughout their clinical experience (Standards 3.L. & 3.H.). Some CITs may gain field experience at multiple clinical sites requiring individual site supervision at each site. Many programs require students to engage in faculty advising meetings (Choate & Granello, 2006), which may take a form analogous to formal supervision. Additionally, supervisees may have clinical supervision, focused on supervisee development and client welfare, as well as administrative supervision, focused on functionality and logistics within an agency; these roles may be fulfilled by the same person or at times by two separate supervisors (Kreider, 2014; Tromski-Klingshirn & Davis, 2007). Consequently, although simultaneous supervision is not required in and of itself, it often occurs in counselor education practice.

Supervision Foundations

Counseling supervision research has increased significantly in the last few decades (Borders et al., 2014). Borders and colleagues (2014) developed best practices for effective supervision, including emphasis on the supervision contract, social justice considerations, ethical guidelines, documentation management, and relational dynamics. Previous research has overwhelmingly demonstrated that a strong supervisory alliance is the bedrock of effective supervision (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). Sterner (2009) further studied the supervisory relationship as a mediator for supervisee work satisfaction and stress. Lambie and colleagues (2018) developed a CIT clinical evaluation to be used in supervision, with strength in assessing personal dispositions in addition to clinical skills. A review of the supervision literature revealed that a strong supervisory relationship based in goal congruence, empathic rapport, and transparent feedback processes (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019; Borders et al., 2014; Sterner, 2009) generate mutual growth between supervisor and supervisee, enhancing clinical work. Additionally, CACREP mandates that faculty and site supervisors foster CIT professional counselor identity through the supervisory process (Borders, 2006; CACREP, 2015).

Counselor development is also a crucial factor in clinical supervision. An entire category of supervision models centralizes the professional development of supervisees in their approach (Bernard & Goodyear, 2019). One of the most widely known models, the Integrative Developmental Model, plots learning, emotion, and cognitive factors across multiple stages of therapist development (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010). By focusing on overarching themes of self–other awareness, autonomy, and motivation, the Integrative Developmental Model (Stoltenberg & McNeill, 2010) illuminates how supervisees fluctuate and grow in their anxiety, self-efficacy, reliance on structure, and independence. All these factors may have substantial impact when considering the complexity that simultaneous supervision brings. Furthermore, professional dispositions of openness to feedback and flexibility and adaptability (Lambie et al., 2018) may have additional developmental implications when considering the complexity of simultaneous supervision.

Ethics similarly serve as a foundation of supervisory experiences. Multiple standards and principles of the ACA Code of Ethics (2014) may be complicated by simultaneous supervision and require special attention. Veracity may be of particular interest given the commonality of supervisee nondisclosure (Kreider, 2014), multiplied by the added number of supervisors in one time period. Furthermore, specific standards in Section D: Relationships With Other Professionals may be implicated by obligations in working with multiple professionals; multiple standards in Section F: Supervision, Training, and Teaching may be indicated because of the convergence of both teaching and clinical supervision in counselor training programs; and, finally, reconciling the additional complexities of simultaneous supervision not explicitly identified elsewhere in the 2014 Code of Ethics may elicit a need to carefully consider Section I: Resolving Ethical Issues. With more parties involved, greater nuance would be expected in ethical decision-making.

Much of the foundational research and reviewed contextual factors have either focused specifically on sole supervision or do not differentiate between sole and simultaneous supervision. When considering best supervision practices, the phenomenon of simultaneous supervision presents distinct practical concerns. Exploration is needed to better understand how supervisees might navigate different but related supervisory relationships, how goals and tasks can be congruent across separate supervisory experiences, and how supervisees would make meaning of multiple sources of feedback. Despite the apparent use of simultaneous supervision in counselor education programs, few researchers have explored these dynamic concerns.

Multiple Supervisors and Multiple Roles

Early researchers began to conceptualize the challenges and strengths inherent in simultaneous supervision in both counseling (Davis & Arvey, 1978) and clinical psychology (Dodds, 1986; Duryee et al., 1996; Nestler, 1990), with mixed results overall. Nestler (1990) identified the difficulties in receiving contradictory feedback from multiple supervisors, reflective of fundamental differences in the supervisors’ approaches. Dodds (1986) similarly identified multiple potential stressors in having concurrent supervisors at agency and training settings. Dodds argued that although the general goals to teach and serve clients overlapped, each had inherent differences in their primary institutional goals and structures. Duryee and colleagues (1996) described a beneficial view of simultaneous supervision, in which supervisees overcome conflicts with site supervisors via support and empowerment from academic program coordinators. Davis and Arvey (1978) presented a case study in which supervisees, in a raw comparison, more highly favored the dual supervision overall. These findings highlight the dynamics that occur in the context of simultaneous supervision and connect with recent findings.

Recent researchers have focused on dual-role supervision, defined as one individual supervisor serving as both a clinical and administrative supervisor to one or more supervisees (Kreider, 2014). Kreider (2014) investigated supervisee self-disclosure as related to three factors: supervisor role (dual role or single role), supervisor training level, and supervisor disclosure. Level of supervisor disclosure was found to be significant in explaining differences in supervisee self-disclosure and was hypothesized as a mitigating factor in supervisor role differences (Kreider, 2014). Tromski-Klingshirn and Davis (2007) surveyed the challenges and benefits unique to dual-role supervision for post-degree supervisees. Most supervisees reported neutral to positive outcomes from a dual-role supervisor, but a minority of supervisees noted power dynamics and fear of disclosure as primarily problematic (Tromski-Klingshirn & Davis, 2007), similar to the earlier hypotheses of Nestler (1990) and Dodds (1986). The small amount of existing research solidifies the prevalence of simultaneous supervision and the challenges and benefits for the supervisees. A missing link emerges in understanding how CITs come to understand their experience in simultaneous supervision from a qualitative perspective.

The distinct focused phenomenon of simultaneous supervision is limited in counseling literature. The few conceptual examinations of simultaneous supervision in the mental health literature have indicated confusion and role ambiguity (Nestler, 1990), while at other times simultaneous supervision has been noted to improve comprehensive learning (Duryee et al., 1996). Our study addresses the gap in the literature regarding current simultaneous supervision in counselor education utilizing qualitative analysis.

Method

Given the limited research on simultaneous supervision and its prevalence within the profession, we decided to explore this phenomenon qualitatively. Our research question was “What is the experience of CITs receiving simultaneous supervision from multiple supervisors?” We used interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to explore this question because of its utility with counseling research, grounded methods of analysis, and emphasis on both contextual individual experiences with the phenomenon and general themes (Miller et al., 2018).

Research Team

At the time of the study, the research team consisted of four doctoral students—William B. Lane, Jr., Timothy J. Hakenewerth, Camille D. Frank, and Tessa B. Davis-Price—who each had previous experience with simultaneous supervision as supervisees and supervisors. The team’s perspective of this phenomenon from both roles informed their interest in and analysis of the phenomenon. The fifth member of the team, David M. Kleist, was our doctoral faculty research advisor. The sixth author, Steven J. Moody, provided support in the writing process.

Participants and Procedure

Our participants were four CITs from CACREP-accredited graduate programs accruing internship hours. Smith et al. (2009) suggested seeking three to six participants for IPA, as this allows researchers to explore the phenomenon with individual participants at a deeper level. All four participants specialized in either addiction, school, or clinical mental health counseling, and identified as White, female CITs ranging from 23 to 37 years old. Additionally, each participant reported receiving supervision from at least two supervisors to include university-affiliated supervisors and site supervisors. Each participant came from a different university representing the Rocky Mountain and North Central regions of the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision. To protect confidentiality, each participant selected a pseudonym for the study.

After securing approval from our university’s review board, we recruited participants through purposive convenience sampling. We posted a recruitment email to the CESNET listserv, an informational listserv for counselor educators and supervisors. This listserv was selected as an initial step of convenience sampling to increase the potential to reach a broad range of counseling programs. Nine individuals responded to the call to participate in the research by taking a participant screening survey that helped us determine suitability for the study. After removing individuals from research consideration because of potential dual relationships, nonresponse, or not meeting inclusion criteria, four individuals were selected as participants. We further planned to engage in serial interviewing to gain richer details of the phenomenon and achieve greater depth with the four participants (Murray et al., 2009; Read, 2018). Prior to data collection, the researchers completed a brief phone screening with each participant to review the interview protocol and explain the phenomenological approach guiding the questions. A $40 gift card was provided as a research incentive to participants. Our selection criteria included (a) being a master’s student within a CACREP counseling program, (b) currently accruing internship hours, and (c) receiving simultaneous supervision. We selected participants in internship only because homogenous sampling helps produce applicable results for a given demographical experience (Smith et al., 2009).

Data Collection

Consistent with the recommendations of Smith et al. (2009), we conducted two semi-structured interviews with each participant lasting between 45–90 minutes. We utilized the online videoconferencing platform Zoom to conduct and record the interviews. First-round interviews consisted of four open-ended questions (see Appendix) that allowed participants to explore the experience of simultaneous supervision in detail (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014). These questions were open-ended to allow participants to explore the how of the phenomenon (Miller et al., 2018). The final interview questions were developed through initial generation based off research and personal experiences with the phenomenon, refinement in consultation with the research advisor, and interview piloting with volunteer students who did not participate in the study. Research participants were asked about their overall experience with having multiple supervisors, benefits and detriments of simultaneous supervision, and the meaning they made as a result of experiencing simultaneous supervision. Second-round interview questions were developed based on participant responses to first-round interview questions. After two rounds of interviews and analysis, we conducted a final member check to confirm themes. All participants expressed that the developed themes were illustrative of their lived experiences with simultaneous supervision.

Data Analysis

We followed IPA’s 6-step analysis process as outlined by Smith et al. (2009) and added a seventh step with the use of the U-heuristic analysis for group research teams (Koltz et al., 2010). Our process consisted of first coding and contextualizing the data individually, followed by group analysis, triangulated with the fifth author, Kleist, as research advisor. We completed this process for each participant and then analyzed themes across participants as suggested by Smith et al. We reached consensus that four superordinate themes emerged with 11 subthemes across the two rounds of interviews. All participants endorsed agreement with the themes from their experiences in simultaneous supervision during the member check process.

Trustworthiness

We integrated Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) framework in conducting multiple procedures for establishing trustworthiness and credibility. We demonstrated prolonged engagement and persistent observation through consistent coding meetings over the span of 1 year. Additionally, we adapted the U-heuristic analysis process during data analysis to analyze data individually and collectively to strengthen the credibility of our findings (Koltz et al., 2010). Finally, after we developed the themes, we triangulated the results with participants via a member check, ensuring the individual and group themes matched their idiographic experiences.

We bridled our personal experiences with simultaneous supervision throughout the research process. Bridling recognizes that researchers have had close personal experiences with the phenomenon and that bias is best managed by recognition rather than elimination (Stutey et al., 2020). The four principal investigators, Lane, Hakenewerth, Frank, and Davis-Price, individually engaged in memo writing, discussed personal reactions to the data, and participated in group discussions regarding meaning-making of the phenomenon with Kleist serving as research advisor.

Results

Our data analysis produced four superordinate themes identified across all cases. These themes were (a) making sense of multiple perspectives, (b) orchestrating the process, (c) supervisory relationship dynamics, and (d) personal dispositions and characteristics. In the sections that follow, each theme is described in further detail and exemplar quotes are given to support their development.

Making Sense of Multiple Perspectives

Making sense of multiple perspectives was defined as the receipt and conceptualization of supervisory feedback from multiple supervisors during the same academic semester. Supervisees identified their supervisors as having differing professional orientations. At times, these differing backgrounds led to supervisors providing differing opinions for the same client.

Participants used metaphors to make meaning of the distinct offerings of their supervisors’ feedback. An example of capturing multiple perspectives was one participant, Emma, utilizing the ancient Indian parable of “The Blind Men and the Elephant” (Saxe, 1868): “The point of the story is all the world religions might have a piece of the picture of God, you know. And so between all of us [clinicians and supervisors] together, maybe we have a perspective of truth.” Through retelling of the Indian fable, this participant was able to vividly capture her personal perspective of differing viewpoints through an integrative lens as opposed to a conflict of ideas. Within this superordinate theme, the two subthemes of supervisee framing and safety net vs. minefield emerged.

Supervisee Framing

Supervisee framing focused on the participant’s personal view of hearing multiple perspectives from supervisors within simultaneous supervision. Some participants described hearing varying perspectives as being helpful and valuable, providing support, and increasing confidence. They typically framed the idea of receiving various feedback as a way to gain ideas and then make their own informed decisions. Molly shared this positive perspective when she stated, “I like coming to [my differing supervisors] with different issues I have with different clients because I feel like they both have valuable experience, but in different ways.” In contrast, Hailey identified multiple perspectives as being “really difficult,” and Diana noted they were “more frustrating than beneficial” and confusing. Similarly, Hailey stated, “My supervisors are all very different, so they give me different feedback, and a lot of times it conflicts with what the other one has said.” The supervisee’s framing of discrepant feedback impacted their overall perceptions with simultaneous supervision. Supervisees either valued or were confused by the feedback. Generally, participants spoke of times when multiple perspectives were beneficial and difficult, but it appeared all participants were left with the task of making sense of multiple perspectives while receiving simultaneous supervision.

Safety Net vs. Minefield

Making sense of multiple perspectives was described as creating a safety net of support, while others found the experience to be a minefield that increased confusion, ambiguity, and isolation. Emma and Molly characterized their experience as providing support in an often overwhelming profession. Molly articulated, “I feel like if I didn’t have that good support, that good foundation, I don’t think I could do it because it’s just so much.” She later added, “I feel like getting those different perspectives, getting that support, getting those encouragers is beneficial because I don’t feel as overwhelmed, even though it’s overwhelming.”

Participants also perceived their simultaneous supervision as a minefield wherein they believed they were in double binds. Hailey reflected on an experience when her supervisors contradicted each other and expressed, “It just sucked because I was doing what my supervisor told me to do and suggested I do, and then I was told everything I did was wrong.” Diana echoed that discrepant feedback felt like a constant dilemma needing to be managed “carefully.” In reflecting on contradicting supervision, Diana said, “It’s hard because everybody has their own thing. . . . You just kind of have to appease everyone.” In the face of conflict, it was easier to placate than resolve. Participants’ cognitive framing was a major element of the phenomenon. Whereas making sense of multiple perspectives focused on the cognitive elements of receiving feedback from different supervisors, the next theme focused on the behavioral elements.

Orchestrating the Process

Another theme that emerged in our data analysis was that of supervisees orchestrating the process of simultaneous supervision. This theme revolved around action-oriented steps in supervision. The essence of this theme was captured when Hailey acknowledged the need for “checking her motives” on what she shared with different supervisors. She asked herself, “Am I sharing this with this [supervisor] because I feel like they’re going to answer in the way that I feel like . . . they should answer, because it’s easier for me?” Hailey acknowledged the difficulty in this, countering with, “Or am I just going to them because it’s that person that I’m supposed to see?” Hailey recognized that having options when it came to approaching supervisors meant that disclosure needed to be intentional rather than straightforward as it is when CITs only have one choice. Participants were aware of their process as they picked and chose what to share with whom, through seeking out a preferred supervisor and through managing the practical aspects of having multiple supervisors. The subthemes of picking and choosing, seeking a preferred perspective, and managing practical considerations were a part of orchestrating the process.

Picking and Choosing

The subtheme of picking and choosing emerged in how our participants described what they would share in supervision and the course of action taken in their counseling practice. This subtheme was labeled as an in vivo code, derived from Hailey’s quote: “So I definitely pick and choose what I talk to about each one. Because—this sounds terrible—but I respect the one [supervisor] more.” Hailey also described feelings of vulnerability and self-efficacy from week to week, related to her reactions from feedback: “I knew after having such a hard supervision last week showing tape, I was like, ‘I cannot be super vulnerable right now. I need to choose something that’s more surface level.’” Molly experienced picking and choosing as a means of proactively managing the repetitive nature of supervision: “I think just bringing different things to different supervisors is really helpful, and not constantly talking about the same client or the same situation, because that gets obnoxious and repetitive, and you’re gonna get a hundred different opinions.”

After receiving feedback, participants had varying perspectives on how to integrate and transfer constructs into action. Some participants viewed discrepant feedback as mutually exclusive, whereas others had a more integrative perspective. Molly expressed frustration in choosing between differing feedback from multiple supervisors: “Sometimes I don’t really know which I should go with, which I should choose, and which would be best for the client. . . . It’s like a double-edged sword, like it’s good at some points, but then bad at others.” Diana, who expressed similar frustration in choosing between perspectives, relieved this tension by resolving that, “I have to live with myself at the end of the day, so as long as it’s not unethical, I don’t worry about it too much. And as far as the stuff that I’m told that needs to be done, I do what I can.” Other participants espoused a much more integrative perspective. Emma stated, “I think the thing I like the best about it is actually when [my supervisors] have different advice . . . because then I feel like between the two, I can kind of find what I really like.” All participants spoke about selecting what to share with supervisors and choosing how to integrate feedback into action.

Seeking a Preferred Perspective

Coinciding with picking and choosing, participants also sought a preferred perspective in the process of receiving simultaneous supervision and orchestrating the process. Some reported the decision to go to one supervisor over another was situationally based and determined by clinical skill or specialty of the supervisor. Diana captured this as follows, “Well, I can have a conversation with either. I just get very different answers. If it’s the technical stuff of what has to be done—her. If it’s ‘how would you approach the situation?’ I do tend to talk to him.” Diana also likened seeking a preferred perspective to a child searching for a desired answer: “It’s like, who do I want to talk to? It’s almost like, talk to the person you want for the answer you want. It’s like, ‘Well, if Mom doesn’t have the right answer, go talk to Dad.’”

Managing Practical Considerations