Oct 15, 2014 | Article, Volume 3 - Issue 3

Katie L. Haemmelmann, Mary-Catherine McClain

Research in chronic illness and disability (CID) in college students has demonstrated that students with disabilities encounter more difficulties psychosocially than their nondisabled counterparts. Subsequently, these difficulties impact the ability of these students to successfully adapt. Using the illness intrusiveness model in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the authors propose therapeutic interventions that could be taken with these students to enhance their overall well-being, adaptation and academic success. The authors also provide final thoughts with directions for future research and application.

Keywords: chronic illness, disability, illness intrusiveness model, cognitive behavioral therapy, college students with disabilities

Chronic illness and disability (CID) impact more than 35 million Americans, often interfering with their everyday life (Livneh & Antonak, 1997). The condition is typically accompanied by a prolonged course of treatment, an often uncertain prognosis, constant and intense psychosocial stress, increasing interference with the performance of daily activities and life roles, and conflict with family and friends (Livneh & Antonak, 1997). Approximately 11% of undergraduate students reported having a disability in 2008 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2011) and 88% of colleges are continuing to enroll students with disabilities (The Princeton Review, 2011). In addition to adjusting to the presence of a disability, adjustment to independent living and beginning academic courses at an undergraduate institution can be challenging for someone with a chronic illness or disability.

The severity of the disability and its functional limitations do not always correlate in a uniform pattern with coping and adjustment (Lustig, Rosenthal, Strauser, & Haynes, 2000). Similarly, disability may include permanent and significant changes in an individual’s body appearance, functional capacities, body image and self-concept (Lustig et al., 2000). This variable, typically referred to as psychosocial adaptation, becomes compounded among college students and deserves further investigation. In order to better understand the adaptation process, conceptualize cases, and provide the most effective services to college students with disabilities, it is important for researchers to test comprehensive models specifically designed to aid in the interpretation of illness-induced interference. Similarly, counselors need to understand and implement empirically supported interventions, techniques and related strategies to assist individuals with disabilities in the transition to higher education.

Currently, there is a dearth of information pertaining to the adjustment of young people that can be applied to college students with chronic illness and disabilities. Additionally, theories within the rehabilitation, quality of life, and counseling literature are used to translate theory into practice. After describing the nature of transitions individuals face upon entering college, discussing current legislative policies, and examining identity formation, this article provides an overview of the illness intrusiveness model and theoretical framework for CBT. Next, the article offers strategies for implementing an integrated model, including elements of illness intrusiveness and CBT, with the college population. Treatment strategies and intervention techniques are also described. Finally, accommodations, the importance of social support, and future directions are addressed.

Identity Formation and College Transition

Identity formation typically continues during the late teens and early 20s (Luyckx, Schwartz, Soenens, Vansteenkiste, & Goossens, 2010), which also is the time when youth attend or transition to higher education. During this time, the individual is still a child on one hand, yet an adult on the other hand. According to Wright (1983), this creates an overlapping situation in which the adolescent with the disability is not only struggling with the problematic overlap of “child” and “adult,” but also that of “normal” and “disabled.” This is a complex time filled with instability and uncertainty regarding the years ahead. A synthesized sense of identity can provide beneficial effects on an individual’s adjustment (Luyckx et al., 2010), and a comprehensive sense of self can be facilitated through psychotherapeutic interventions. Also, the process of adaptation is multidimensional, complex and subjective (Smart, 2001). Consequently, a comprehensive framework for assessing and intervening is critical for fostering positive counseling outcomes.

Preparing someone for a career is a task that should not be taken lightly, but given the utmost attention. Career can be defined as the “time extended working out of a purposeful life pattern through work undertaken by the person” (Sampson, Reardon, Peterson, & Lenz, 2004, p. 6).This definition helps clarify the idea that a career is an activity people engage in regularly through a lifetime. Employment opportunities for this population are already limited by job choice (variability), available hours, and reduced salary (Schmidt & Smith, 2007). Also, enhancing potential job opportunities for individuals with disabilities is beneficial, as research has shown that the onset of a disability can negatively influence one’s vocational identity—potentially leading to poor adjustment, limited self-direction and goal setting, and lower career development (Enright, Conyers, & Szymanski, 1996; Skorikov & Vondracek, 2007; Yanchak, Lease, & Strauser, 2005).

According to Kirsh et al. (2009), with the economy becoming increasingly knowledge-based, and as the forces of globalization transform to eliminate entry-level positions, people with limitations in cognitive function may become increasingly marginalized. This is not to say that this population can maintain only entry-level positions, but to reiterate that as there is an increase in students with disabilities attending universities, there is an increase in job requirements, qualifications and performance levels required by all populations. Enhancing education and overall college experience with counseling will assist these students as they acquire new skills to use for the rest of their lives.

Need for Psychotherapeutic Interventions

In the past 20 years, there has been a trend of more persons with disabilities pursing higher education. Based on the National Organization on Disability Harris Survey of Americans with Disabilities conducted in 2000, there was a marked increase in persons with disabilities having graduated from high school (77%) compared to those in 1986 (61%). Based on several legislative and social policies implemented in the 1980s (Canadian Human Rights Act, 1985) and 1990s (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 1997 [IDEA]), an estimated 8–18% of students in higher education are students with disabilities (Sachs & Schreuer, 2011). Furthermore, persons with disabilities entering postsecondary education are making significant progress toward successful completion of their program of studies (Stodden & Whelley, 2004). This is why educators, administrators, and policymakers are working to improve services while also providing accommodations, interventions, and support services in postsecondary settings (Barazandeh, 2005; Brinckerhoff, Shaw, & McGuire, 1992; Dowrick, Anderson, Heyer, & Acosta, 2005; Dutta, Kundu, & Schiro-Geist, 2009; Johnson, 2006; Swanson & Hoskyn, 1998; West et al., 1993). Examples of such accommodations include transportation, separate locations for test taking, access to private study rooms, and extended time on exams.

With the reauthorization of the IDEA in 1997 (PL 94-142), there was an increase of higher expectations upon quality preparation to postsecondary education and employment for persons with intellectual disabilities. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) sought to provide reasonable accommodations to ensure equal access to learning and work environments (Jacob & Hartshorne, 2007). The vocational rehabilitation system exists to provide assistance to individuals with disabilities seeking employment. This can be a good support system for those interested in higher education, but only supports eligible consumers (Gilmore & Bose, 2005). While these recent pieces of legislation have been incredibly beneficial and have encouraged individuals and professionals alike to actively engage in advocacy, they do not specifically address the access or right to counseling as an appropriate accommodation.

As students transition to postsecondary education, fear of the unknown affects not only those transitioning, but the people around them (e.g., professors, administrators or counselors) as they experience a change in roles. Parents, for instance, may want to protect their child from the risks of the larger world, and limit them by choosing self-contained and protected programs (Stodden & Whelley, 2004). This approach may deprive students of the opportunity for further education. With optional counseling specifically designed for those individuals with disabilities transitioning into the next phase of life, this may be reassuring not only for the student, but also for the student’s primary support system. One counseling model to implement in such situations is the illness intrusiveness model.

Illness Intrusiveness Model: Theoretical Framework

The illness intrusiveness model was developed based on the idea that illness-induced interference, in addition to interests and valued activities, compromises one’s psychological well-being—ultimately contributing to emotional distress. It is derived from a variety of sources such as functional losses, treatment side effects, disease and treatment-related lifestyle disruptions, and disease-related anatomical changes (Devins, 2010). The model postulates that when there is a decrease in positively reinforcing outcomes from valued activities and limited personal control (e.g., mood level) to obtain positive outcomes and avoid negative ones, significant adaptive changes and coping demands occur (Devins, 2010).

By examining the five factors of disease—that is (1) treatment requirements, (2) personal control, (3) nature of life outcomes, (4) psychological factors, and (5) social factors—one can inspect the level of participation in valued activities, also known as illness intrusiveness. Illness intrusiveness may serve or act as a mediating variable by which unbiased circumstances of disease and treatment influence psychosocial well-being and emotional distress. Specifically, illness intrusiveness is based not only on the experience of the person, but also the psychological characteristics based on objective and subjective concepts (Roessler, 2004).

This model posits that social and psychological factors have a direct effect on life outcomes. Time spent transitioning into college is heavily influenced by social factors, which can create positive or negative experiences in the individual. If the social factors weigh heavily on the individual’s psychological factors in a maladaptive way, the person’s coping abilities and adaptation skills may be compromised and lead to undesirable outcomes. The model also encompasses the idea of locus of control, presented as personal control of self-efficacy (similar to what was described earlier in this article), the idea being that low levels of personal control result in learned helplessness (Roessler, 2004). Furthermore, the theoretical framework hypothesizes that intrusiveness mediates the psychosocial effect of chronic conditions. Indirectly through the effects on intrusiveness, illness and treatment variables are believed to impact subjective well-being (Bettazzonie, Zipursky, Friedland, & Devins, 2008). Incorporation of the illness intrusiveness model can assist professional counselors and clients alike in laying out a clear path of focus (i.e., the five factors of disease; Roessler, 2004) while simultaneously increasing one’s coping and adaptation skills, as well as external allocation of self-efficacy. After describing an assessment tool and following a review of ways in which the illness intrusiveness model has been applied to specific illnesses and populations, the authors provide a rationale for implementing this model among college students with disabilities.

Application of the Illness Intrusiveness Model

Previous research suggests that applying various components of the illness intrusiveness model (e.g., examination of domains) in end-of-stage renal disease clients is effective in objectively measuring varying modes of treatment (e.g., transplantation, dialysis; Devins, et al., 1983). Furthermore, the levels of illness intrusiveness directly affected the psychosocial impact of the condition. Additionally, it was noted that severity levels of hyperhidrosis shared a significant positive correlation with scores on the Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale (IIRS) (Devins et al., 1983). Intrusiveness scores were weakly related to efforts to control the condition (i.e., medications and ointments), which is indicative of the value of knowledge of self-care techniques and action-based knowledge (Roessler, 2004). Empirical support also has pointed to illness intrusiveness as a precipitant for depression and for feeling a loss of control. This has been observed in persons with arthritis, cancer, diabetes and multiple sclerosis (Roessler, 2004). Furthermore, Devins (2010) notes that levels of illness intrusiveness vary according to illness severity, and weigh in differently for valued activities. This is of particular importance when collaborating therapeutically with college students with disabilities, since there are a wide range of disabilities (e.g., learning disabilities, physical disabilities, mental illness) and they vary in severity (e.g., psychiatric symptoms, functional ability). Subsequently, even among college students with disabilities, there is a wide array of differences; one would expect a shift in valued activities based on transitioning (e.g., social support, school involvement) and disability interference.

The illness intrusiveness model is ideal for working with college students with disabilities because it focuses on improving psychosocial adaptation outcomes. Specifically, it stresses the effect of psychological, social and environmental variables on the interpretation of the disease (Roessler, 2004). This is essential knowledge for implementing effective therapeutic interventions for this population, because often the transition into the college atmosphere impacts the interpretation of the individual and the disability. Additionally, the theoretical framework helps to estimate the effect of disease interpretation and the intrusiveness of treatment factors (Roessler, 2004).

As mentioned previously, the college student population typically struggles to form self-identity in terms of a developmental framework, and intrusiveness is presented in this model as both an objective and subjective concept. This is noteworthy since these individuals are still processing their identity, their life goals, and their viewpoints. With a helping professional, they can work collaboratively to change perspectives that may be distorted or need reframing. Finally, the illness intrusiveness model implies that intrusiveness has a direct effect on both personal control and life outcomes (Roessler, 2004). Through prevention or early intervention, college students with disabilities will realize and begin to feel empowered as they recognize their ability to take control of their lives. This can further be reinforced by seeing positive outcomes almost immediately when collaborating with the practitioner. Before discussing how the illness intrusiveness model can be integrated with other treatment approaches and how it can be applied to college students with disabilities, it is useful to provide a brief history of general psychotherapy with disabled persons and core principles of CBT with this population.

History of Counseling with Persons with Disabilities

Over the past several decades, four basic approaches to adjustment services (e.g., work acclimation) have emerged in disability literature. While the approaches are not mutually exclusive, each offers a new viewpoint on adjustment for persons with disabilities and sheds perspective on both the client and practitioner.

The work acclimation approach utilizes the psychological principle that the greater degree to which a current environment resembles a future environment, the more likely an individual would behave in the same manner in the future environmental setting. Programs utilized almost exclusively in work centers were pay incentives, peer and supervisory work pressure, production rate feedback, lead workers, and status-promotion incentives.

The problem-solving approach to adjustment services represents the second model. It begins by obtaining baseline measures of the problem and delineates adjustment services to any treatment and training modalities necessary to ameliorate the problem, thus allowing the student to succeed academically and vocationally. It is within this model that the approach employs behavioral counseling and behavioral modification techniques that can be applied in multiple settings or situations (Couch, 1984). For example, in a university setting, students with disabilities can be seen for brief or extended psychological services, in which baseline and outcome data are used to encourage behavioral modification and monitor intrusiveness.

In the developmental approach, clients are viewed as capable, problem-solving individuals, fully qualified to accept responsibility for life and determine personal direction. They are taught self-responsibility and self-potency, as well as beliefs, values, and skills, all of which will enable them to solve problems, maintain a sense of self-worth, and enhance personal identity.

Finally, the education approach takes on a different perspective and focuses on skill deficits. This helps the client to engage in remedial education, learn about available resources, and conquer tasks. Examples of such tasks include acquiring a driver’s license or earning a college degree (Couch, 1984). A focus on skill deficits blends well with the theoretical origins of CBT. The following section briefly describes the framework of CBT.

Theoretical Framework for CBT

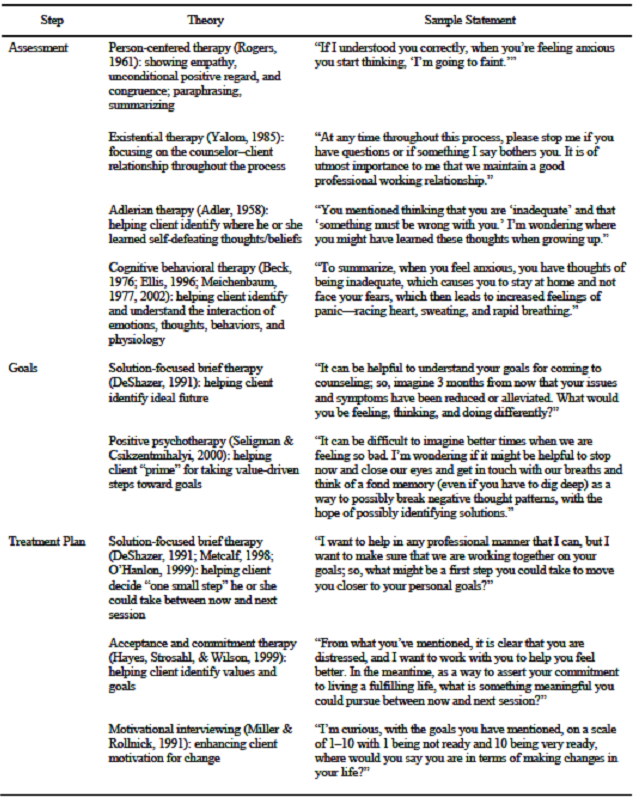

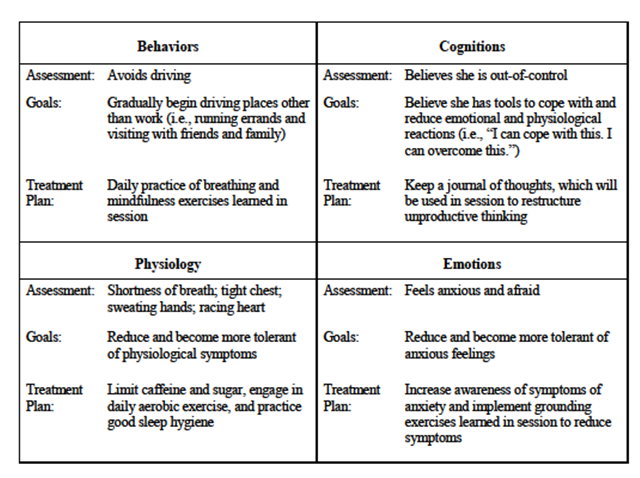

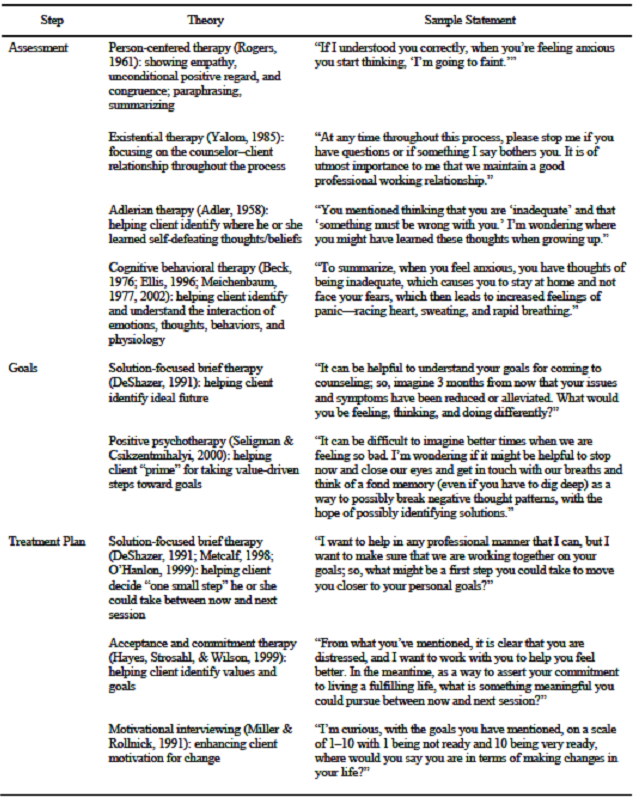

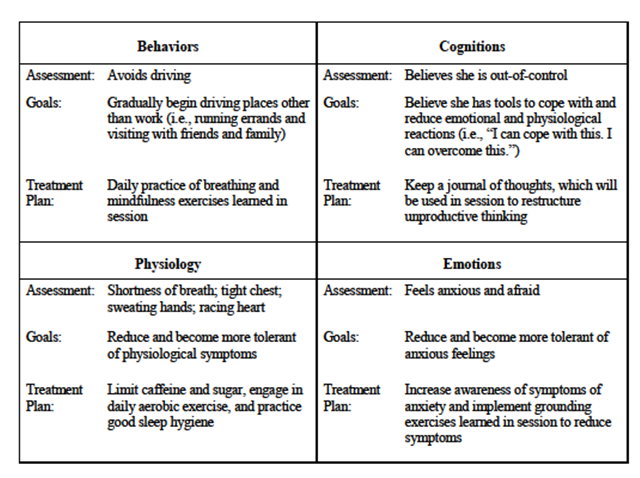

Three main goals set forth in the field of rehabilitation counseling pertain to affective goals, cognitive goals, and behavioral goals (Parker, Szymanski, & Patterson, 2005). This is similar to taking a holistic or ecological approach in the field of counseling. It is important to treat not just specific aspects of individuals, but to treat the individuals as humans in their entirety. Thus, when addressing college students with disabilities, it could be important to integrate the illness intrusiveness model with that of CBT. The model itself enables the counselor to apply cognitive and behavioral interventions in order to reduce illness intrusiveness strategically, which could encourage the client to participate in valued activities, redefine personal goals, and restructure irrational beliefs related to intrusiveness (Roessler, 2004).

Furthermore, the counselor is able to provide knowledge of self-management and self-care skills, which is facilitated by task-focused coping and problem-solving skills, both of which are central constructs from CBT and can lead to a positive impact on illness intrusiveness. Finally, by including personal control or self-efficacy as critical variables in the illness intrusiveness model, and as a way to better understand life outcomes, individuals are supported in impacting their perceived self-control on life outcomes related to educational achievement and overall well-being (Roessler, 2004).

Integrating the Illness Intrusiveness Model and CBT

Prior to discussing techniques and skills that can be utilized within this framework and among this population, the present article discusses the importance of incorporating specific concepts or tasks within the realm of a client’s goals. Examining client outcomes of counseling interventions is necessary in the field of mental health and other related fields to acquire knowledge on effective treatments, obtain financial funds, establish accountability, and achieve long-term positive results. In addition to cognitive behavioral techniques, client variables with this population may impact the outcome of therapy. For example, Ju (1982) discovered that clients having 12 years of education do not seem to benefit from receiving information and exploring feelings. Rather, they tend to benefit from counselors who predominantly listen attentively and focus on the facilitation of client expression and concern. Additionally, clients with more than 12 years of education tend to reap the most benefits from counselors who not only emphasize the processing of information, but also share personal values, opinions and experiences with the client. This has potential treatment implications from the start of counseling, because to be a viable candidate for collegiate studies, the individual has to successfully complete 12 years of prior education (either formally or in an alternative manner). As students attending school will always vary widely in age, this factor should be kept in the forefront of the counselor’s mind.

Rehabilitation counseling has a history of being goal directed and behaviorally oriented as opposed to a psychodynamically oriented treatment (Ju, 1982). Similarly, a defining characteristic of CBT is the proposal that symptoms and dysfunctional behaviors are often cognitively mediated; thus, modifying dysfunctional thinking and beliefs can lead to improvement (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006). By following a psychoeducational model, emphasizing therapy as a learning process that includes acquiring and practicing new skills, learning new ways of thinking, and obtaining more effective ways of coping (Corey, 2005), students with disabilities can benefit from improved adjustment to the college atmosphere.

A central role in CBT is the treatment rationale, which provides clients and counselors with a model of etiology and treatment (Addis & Carpenter, 2000). It is within this framework that the counselor teaches the client to identify, evaluate and change dysfunctional thinking patterns so therapeutic changes in mood and behavior can occur (Padesky & Greenberger, 1995). Additionally, it is imperative to address an individual’s metacognitions, or understanding of self-knowledge, in order to grasp the process of cognition and its outcomes (Hresko & Reid, 1988).

Thomas and Parker (1984) remark on the need for effective counseling with persons with disabilities, identifying the following two main focuses: career and psychosocial issues. This only reiterates the need for therapeutic intervention for this specific population who is trying to further education in order to obtain chosen careers while simultaneously adapting to a new lifestyle and appropriately managing the disabilities. It is by weaving together the major tenets presented in CBT (e.g., thoughts, moods, behaviors, biology, and environment; Padesky & Greenberger, 1995), with the five factors of disease (Roessler, 2004) in the illness intrusiveness model that practitioners will be better able to serve this population. This is not to say that all ten areas will need to be remedied or addressed for each individual seeking treatment. Rather, counselors need to be aware that each individual will have different needs to meet or areas to improve.

Akridge (1981) stated that psychological adjustment is an ongoing process of evaluating the self-in-situation to adaptation. A comprehensive self-assessment in the psychosocial domain is the process of summarizing one’s satisfactions and dissatisfactions within the self and the personally relevant aspects of one’s situation. This could be undertaken within the realm of the therapeutic alliance as the client and counselor are working collaboratively toward agreed-upon goals and a focus on improvement. One could suggest the completion of a prescribed homework assignment addressing the area needing further investigation. The client could then experience an increase in self-confidence through exploring each domain, thus decreasing the impact of intrusiveness.

To begin treatment successfully, the counselor and client need to establish a positive, collaborative working relationship. Aaron Beck emphasized the quality of the therapeutic relationship as basic to the application of cognitive therapy (Corey, 2005). The core therapeutic conditions described by Carl Rogers in his person-centered approach are viewed by cognitive therapists as being necessary, but not sufficient, in producing optimal therapeutic effects (Corey, 2005).

The collaborative relationship is essential because it conveys to clients that they possess important information that must be shared to solve problems. Counselors employ general strategies and treatment models while clients are keepers of all the information about unique experiences—only clients can describe thoughts and moods (Padesky & Greenberger, 1995). This again enables clients to build self-esteem and feelings of self-worth so they begin to feel confident in skills and abilities in areas they may doubt. This in turn impacts the domains of career choice, personal control, life outcomes, and psychological and social factors.

In order to be successful at the collegiate level, one must possess sufficient organizational skills. When working with students with disabilities, it is important to address this topic and readdress it throughout the psychotherapeutic process. This approach is key to assist clients in learning to control the things they can in regards to homework assignments, readings, and note-taking, so that if something unexpected or overwhelming becomes more pertinent in unpreventable circumstances, clients will be able to recognize that they have done what they can to contain circumstances within their personal control.

This also relates back to the topic of increasing awareness of metacognition and the cognitive processes. For example, a student may begin to recognize trouble learning a particular topic or realize that there is a need to double-check written work. Similarly, a student may know to review all potential answers before choosing one as the correct option and understand the need to write a task down in order to remember it—essentially working to improve study skills (Hresko & Reid, 1988). Another concept or task that needs to be addressed with this population is that of appropriate accommodations within the university.

Accommodations

The Americans with Disabilities Act states that a disability is “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits the individual in one or more major life activities” (Jacob & Hartshorne, 2007, p. 209). In such instances, in order for the students to receive and begin using the resources available within the setting and circumstances of the disability, they most likely will need to provide appropriate documentation. This may be an instance in which the therapist needs to take on a more pragmatic role and point the students to the designated resources so they can begin partaking in services. In addition, this simple task models advocacy for the individual. Once the client has taken the required steps to establish services, the practitioner will need to discuss with the client what kinds of services or accommodations may be needed, not only in the classroom, but also for transportation, living, studying, or choosing a career path. A client may need extra time taking tests, to meet with a class note-taker, or require special transportation or access within living space. Addressing organizational skills, as stated previously, may be a way to lead into the topic of study habits or assistance required in completing homework. Clients with mobility limitations or attention deficits may need instruction in specialized computer programs when required to write their thoughts on paper.

Altering Social Factors

Another task or concept that could be discussed within the counseling sessions is social support outside of the therapeutic alliance. Counselors should discuss with the client what types of support have been used in the past, what has worked, what did not work, and what could be modified. In some cases, clients may rely solely on their family for social support while others may rely on both family and friends. It would be beneficial to discuss the client’s preferred approach, to lay out the necessary steps, and to discuss the practicality of accomplishing the support. Some students may find it helpful to join various clubs or organizations, while others may wish to take part in a support group for persons with disabilities who are experiencing similar struggles. One option may be attending a counseling group offered at a university counseling center in which aspects of CBT and illness intrusiveness are addressed. Regardless of the outlet clients require to reach the most beneficial level of social support, they need a realistic understanding of the work required to reach the goal, a picture of what that process looks like, and a comprehensive understanding of why a good support system is necessary. This process will most likely be an ongoing learning experience for both the counselor and client as appropriate adjustments are made and learning and growth are facilitated.

Corey (2005) stated that the goal of CBT is to challenge the client to confront faulty beliefs with contradictory evidence that is gathered and can be evaluated (e.g., thought record). Another important aspect of CBT is goal setting. Padesky and Greenberger (1995) identified five key points about the importance of goal setting. First, setting goals helps identify what clients want to change, and provides guideposts to track progress. Charting such changes within the realm of the illness intrusiveness model can be done by utilizing the IIRS. This method helps the counselor gather baseline data at the onset of therapy, as well as monitor progress and present problems and symptoms.

Second, breaking general goals into specific goals simplifies the process into step-by-step plans for achieving general goals. Third, prioritizing goals helps the client and practitioner to decide which goals should be addressed first to provide the most beneficial outcome from therapy. Fourth, charting emotional changes helps monitor progress toward reaching goals. One can track changes based on emotional intensity and frequency, as well as specific mood-related symptoms. Finally, if the client is not making progress toward the goals, the counselor should consider breaking goals into even smaller steps, thus addressing the impediment to progress and considering changes in the treatment plan (Padesky & Greenberger, 1995).

One of the many reasons that agreement and clarity in goal setting is important is that regardless of individual differences, therapeutic outcomes are more apt to be positive when the counselor and client move toward the same goals (Ju, 1982). It is important that, when a client with specific disabilities makes progress toward and ultimately accomplishes each goal, reinforcement is applied by the practitioner. Reinforcement should be put into practice with intentionality and only when it promotes the attainment of skills and behaviors that the client needs to meet objectives. This skill needs to be used systematically rather than randomly (Thomas & Parker, 1984).

Other techniques that can be employed during the therapeutic process are that of Socratic questioning and activity scheduling. The first occurs by having the practitioner facilitate the telling and retelling of the story until opportunities for new meaning and story content develop (Corey, 2005). The use of Socratic questioning with students with disabilities enables these clients to realize they possess an understanding of their problems and preconceived notions, thoughts, or beliefs, and can alter them by elaborating and discussing matters further. In sum, the use of one simple technique could have a profound impact on illness intrusiveness factors such as personal control, social and psychological factors, and life outcomes.

Activity scheduling is not only another important aspect of CBT, but also an effective tool for decreasing illness intrusiveness. By engaging the client in planned activities, the client is encouraged to take an active role in life, as well as rediscover activities that may have previously been enjoyed. By discerning likes and dislikes, the client is able to increase personal insight and lower levels of depression. Activity scheduling also enables clients to see that they are capable of not just choosing the level and type of daily activities, but also seeing the big picture in choosing the direction of life outcomes. By realizing that they are able to control these tasks, the clients will also begin to reframe their locus of control from external to internal.

Finally, cognitive behavioral counselors aim to teach clients how to be their own therapist (Corey, 2005). As with any case, the hope is that the client can walk away from counseling and make use of skills acquired throughout the therapy process, applying them in daily living without therapeutic assistance. Whether treatment is permanently terminated or titrated down, the outcome will directly impact illness intrusiveness through treatment factors, feelings of personal control, life outcomes, and psychological and social factors.

While research within this specific population is lacking, the application of CBT among persons with intellectual disabilities has shown varied results. For example, Gustafsson et al. (2009) found weak correlations between behavioral therapy, CBT, and other forms of integrated support, while others (Oathamshaw & Haddock, 2006) showed that persons with intellectual disabilities and psychosis could link events and emotions, and differentiate feelings from behaviors—all skills necessary to engage in CBT. While effectiveness among those with intellectual disabilities may or may not be applicable to other types of disabilities, it is worthy to note that evidence exists. It would be beneficial to add to this evidence by supporting the use of CBT in combination with the illness intrusiveness model among students with disabilities transitioning into postsecondary education. Furthermore, by implementing this treatment modality among all college students with disabilities, researchers and counselors would be able to establish whether this model is effective with specific disabilities, cases in which it may not be as useful, and ways treatment can be modified or enhanced. Utilizing the authors’ presented model, future research could aim to investigate treatment of different types of college students with disabilities (e.g., learning disabilities, psychiatric disabilities, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]) and examine the effectiveness, similarities, differences, or any future directions. Treatment may be implemented in both the individual and group setting, and individual changes should be monitored by means of the IIRS.

Summary

The use of CBT among college students with disabilities transitioning into the college atmosphere could have a vast impact on illness intrusiveness. While, to the current authors’ knowledge, no recent studies have looked at implementing this model and mode of treatment, it would be an area worth investigating. The convergence of an empirically supported model such as the illness intrusiveness model, as well as a theory having a preponderance of empirical evidence such as CBT, would be a solid foundation to begin implementation of therapeutic intervention.

The college student population will have to face many potentially problematic situations when transitioning into the world of continued education. Some struggles that may be encountered when assisting college students in transition who also have disabilities may relate to homework completion, organizational stills, appropriate accommodations (e.g., extended test taking time, use of a note-taker, use of assistive computer technology), transportation and living accommodations, and reliable social support systems. By addressing the above areas of concern, an efficacious treatment could be set into practice in order to adhere to professional and personal standards.

Kirsh et al. (2009) found that “disabled adults are twice as likely to be in a household with lower

incomes, and disabled people of working age are more than twice as likely as nondisabled people to have no employment-related qualifications” (p. 392). This is an essential point when discussing the importance of secondary schooling and continued education for persons with disabilities. If the statistics show that disabled persons are twice as likely as those without disabilities to have no employment-related qualifications, then accommodating them in the transition to the college environment seems appropriate. It makes sense to aid others in engaging and succeeding at their endeavors rather than waiting for them to fail or not assisting in the process at all. Counseling intervention and prevention could benefit those who may be struggling to persevere on their own, and implementation of the illness intrusiveness model in combination with CBT may provide to incoming college students with disabilities the appropriate coping skills to transition adaptively to the next phase of their life.

References

Addis, M. E., & Carpenter, K. M. (2000). The treatment rationale in cognitive behavioral therapy: Psychological mechanisms and clinical guidelines. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 7(2), 147–156. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(00)80025-5

Akridge, R.L. (1981). Psychosocial assessment in rehabilitation. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 12(1), 36–39.

Barazandeh, G. (2005). Attitudes toward disabilities and reasonable accommodation at the university. The UCI Undergraduate Research Journal, 8, 1–12.

Bettazzoni, M., Zipursky, R. B., Friedland, J., & Devins, G. M. (2008). Illness intrusiveness and subjective well-being in schizophrenia. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196, 798–805.

Brinckerhoff, L. C., McGuire, J. M., & Shaw, S. F. (2002). Postsecondary education and transition for students with learning disabilities (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 17–31.

Canadian Human Rights Act (December 15, 2012). Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca

Corey, G. (2005). Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Couch, R. H. (1984). Basic approaches to adjustment services in rehabilitation. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 15, 20–23.

Devins, G. M. (2010). Using the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale to understand health-related quality of life in chronic disease. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68, 591–602.

Devins, G. M., Binik, Y. M., Hutchinson, T. A., Hollomby, D. J., Barré, P. E., & Guttmann, R. D. (1983). The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: Importance of patients’ perceptions of intrusiveness and control. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 13, 327–343.

Dowrick, P.W., Anderson, J., Heyer, K., Acosta, J. (2005). Postsecondary education across the

USA: Experience of adults with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 22, 41–47.

Dutta, A., Kundu, M., & Schiro-Geist, C. (2009). Coordination of postsecondary transition services for students with disabilities. Journal of Rehabilitation, 75(1), 10–17.

Enright, M. S., Conyers, L. M., & Szymanski, E. M. (1996). Career and career-related educational concerns of college students with disabilities. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75, 103–114.

Gilmore, D. S., & Bose, J. (2005). Trends in postsecondary education: Participation within the vocational rehabilitation system. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 22, 33–40.

Gustafsson, C., Öjehagen, A., Hansson, L., Sandlund, M., Nyström, M., Glad, J., … Fredriksson, M. (2009). Effects of psychosocial interventions for people with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems: A survey of systematic reviews. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(3), 281–290. doi:10.1177/1049731508329403

Hresko, W. P., & Reid, D. K. (1988). Five faces of cognition: Theoretical influences on approaches to learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 11, 211–216.

Individuals with Disability Education Act Amendments of 1997 [IDEA]. (1997). Retrieved from http://thomas.loc.gov/home/thomas.php

Jacob, S., & Hartshorne, T. S. (2007). Ethics and law for school psychologists (5thed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Johnson, A. L. (2006). Students with disabilities in postsecondary education: Barriers to Success

and implication to professionals. Vistas Online. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/vistas/vistas-2006

Ju, J. J. (1982). Counselor variables and rehabilitation outcomes: A literature overview. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 13, 28–31.

Kirsh, B., Stergiou-Kita, M., Gewurtz, R., Dawson, D., Krupa, T., Lysaght, R., & Shaw, L. (2009). From margins to mainstream: What do we know about work integration for persons with brain injury, mental illness and intellectual disability? Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation, 32(4), 391–405. doi:10.3233/WOR-2009-0851

Livneh, H., & Antonak, R. F. (1997). Psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

Lustig, D. C., Rosenthal, D. A., Strauser, D. R., & Haynes, K. (2000). The relationship between sense of coherence and adjustment in persons with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 43, 134–141.

Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Goossens, L. (2010). The path from identify commitments to adjustment: Motivational underpinnings and mediating mechanisms. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 52–60.

National Organization on Disability/Louis Harris & Associates, Inc. (2000). Key findings: 2000 N.O.D./Harris survey of Americans with disabilities. Retrieved from National Organization on Disability Web site: http://nod.org/assets/downloads/2000-key-findings.pdf

Oathamshaw, S. C., & Haddock, G. (2006). Do people with intellectual disabilities and psychosis have the cognitive skills required to undertake cognitive behavioural therapy? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19, 35–46.

Padesky, C. A., & Greenberger, D. (1995). Clinician’s guide to mind over mood. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Parker, R. M., Szymanski, E. M., & Patterson, J. B. (2005). Rehabilitation counseling: Basics and beyond (4th ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Roessler, R. T. (2004). The illness intrusiveness model: Rehabilitation implications. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 35, 22–27.

Sachs, D., & Schreuer, N. (2011). Inclusion of students with disabilities in higher education: Performance and participation in student’s experiences. Disability Studies Quarterly, 31(2), 1–19.

Sampson, J. P., Reardon, R. C., Peterson, G. W., & Lenz, J. G. (2004). Career counseling & services: A cognitive information processing approach. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Schmidt, M. A., & Smith, D. L. (2007). Individuals with disabilities perceptions on preparedness for the workforce and factors that limit employment. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation, 28, 13–21.

Skorikov, V. B., & Vondracek, F. W. (2007). Vocational identity. In V. B. Skorikov & W. Patton (Eds.), Career development in childhood and adolescence (pp. 143–168). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense.

Smart, J. (2001). Disability, society, and the individual. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

Stodden, R. A., & Whelley, T. (2004). Postsecondary education and persons with intellectual disabilities: An introduction. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 39, 6–15.

Swanson, H. L., & Hoskyn, M. (1998). Experimental intervention research on students with

learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of treatment outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 68, 277–321.

The Princeton Review (2011, July 1). Many students with disabilities attending college. Retrieved from http://in.princetonreview.com/in/2011/07/many-students-with-disabilities-attending-college.html

Thomas, K. R., & Parker, R. M. (1984). Counseling interventions. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 15, 15–19.

U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics (2011). Fast facts: Students with disabilities. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=60

West, M., Kregel, J., Getzel, E. E., Ming, Z., Ipsen, S. M., & Martin, E. D. (1993). Beyond section 504: Satisfaction and empowerment of students with disabilities in higher education. Exceptional Children, 59, 456–467.

Wright, B. A., (1983). Physical disability—A psychosocial approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Yanchak, K. V., Lease, S. H., & Strauser, D. R. (2005). Relation of disability type and career thoughts to vocational identity. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 48, 130–138.

Katie L. Haemmelmann, NCC, is a predoctoral intern at All Children’s Hospital and the Rothman Center for Pediatric Neuropsychiatry in St. Petersburg, FL. Mary-Catherine McClain is a predoctoral intern at Johns Hopkins University Counseling Center in Baltimore, MD. Correspondence can be addressed to Katie L. Haemmelmann, 3210 Stone Building, 1114 West Call Street, Tallahassee, FL 32306, klh08d@my.fsu.edu.

Oct 15, 2014 | Article, Volume 3 - Issue 3

Kathleen Brown-Rice

The theory of historical trauma was developed to explain the current problems facing many Native Americans. This theory purports that some Native Americans are experiencing historical loss symptoms (e.g., depression, substance dependence, diabetes, dysfunctional parenting, unemployment) as a result of the cross-generational transmission of trauma from historical losses (e.g., loss of population, land, and culture). However, there has been skepticism by mental health professionals about the validity of this concept. The purpose of this article is to systematically examine the theoretical underpinnings of historical trauma among Native Americans. The author seeks to add clarity to this theory to assist professional counselors in understanding how traumas that occurred decades ago continue to impact Native American clients today.

Keywords: historical trauma, Native Americans, American Indian, historical losses, cross-generational trauma, historical loss symptoms

Compared with all other racial groups, non-Hispanic Native American adults are at greater risk of experiencing feelings of psychological distress and more likely to have poorer overall physical and mental health and unmet medical and psychological needs (Barnes, Adams, & Powell-Griner, 2010). Suicide rates for Native American adults and youth are higher than the national average, with suicide being the second leading cause of death for Native Americans from 10–34 years of age (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2007). Given that there are approximately 566 federally recognized tribes located in 35 states, and 60% of Native Americans in the United States reside in urban areas (Indian Health Services, 2009), there is much diversity within the Native American population. Therefore, it is difficult to make overall generalizations regarding this population (Gone, 2009), and it is important to not stereotype all Native American people. Still, Native American individuals are reported as having the lowest income, least education, and highest poverty level of any group—minority or majority—in the United States (Denny, Holtzman, Goins, & Croft, 2005) and the lowest life expectancy of any other population in the United States (CDC, 2010).

To explain why some Native American individuals are subjected to substantial difficulties, Brave Heart and Debruyn (1998) utilized the literature on Jewish Holocaust survivors and their decedents and pioneered the concept of historical trauma. The current problems facing the Native American people may be the result of “a legacy of chronic trauma and unresolved grief across generations” enacted on them by the European dominant culture (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998, p. 60). The primary feature of historical trauma is that the trauma is transferred to subsequent generations through biological, psychological, environmental, and social means, resulting in a cross-generational cycle of trauma (Sotero, 2006). The theory of historical trauma has been considered clinically applicable to Native American individuals by counselors, psychologists, and psychiatrists (Brave Heart, Chase, Elkins, & Altschul, 2011; Goodkind, LaNoue, Lee, Freeland, & Freund, 2012; Myhra, 2011). However, there has been uncertainty about the validity of this theory due to the ambiguity of some of the concepts with little empirical evidence (Evans-Campbell, 2008; Gone, 2009). Specifically, there has been a lack of research about how the past atrocities suffered by the Native American people are connected with the current problems in the Native American community. The intent of this article is to examine the theoretical framework of historical trauma and apply recent research regarding the impact of trauma on an individual’s physiological functioning and cross-generational transmission of trauma. Through this analysis, the author seeks to assist professional counselors in their clinical practice and future research.

Core Concepts of Historical Trauma

Sotero (2006) provided a conceptual framework of historical trauma that includes three successive phases. The first phase entails the dominant culture perpetrating mass traumas on a population, resulting in cultural, familial, societal and economic devastation for the population. The second phase occurs when the original generation of the population responds to the trauma showing biological, societal and psychological symptoms. The final phase is when the initial responses to trauma are conveyed to successive generations through environmental and psychological factors, and prejudice and discrimination. Based on the theory, Native Americans were subjected to traumas that are defined in specific historical losses of population, land, family and culture. These traumas resulted in historical loss symptoms related to social-environmental and psychological functioning that continue today (Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, & Chen, 2004).

Historical Losses

For the last 500 years, individuals from the dominant European cultures have engaged in behaviors that have resulted in the purposeful and systematic destruction of the Native American people (Plous, 2003). Native Americans have been subjected to traumas that have resulted in specific historical losses. These losses include loss of people, loss of land, and loss of family and culture (Brave Heart & Debruyn, 1998; Garrett & Pichette, 2000; Whitbeck et al., 2004).

The population of Native Americans in North America decreased by 95% from the time Columbus came to America in 1492 and the establishment of the United States in 1776 (Plous, 2003). This decline can be explained by two main factors: the intentional killing of Native Americans and the exposure of Native Americans to European diseases (Trusty, Looby, & Sandhu, 2002). The majority of the Native American population died due to its lack of resistance to “diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria, measles, and cholera” that Europeans brought to North America (Trusty et al., 2002, p. 7). While some of the exposure to these illnesses was unintentional on the part of the Europeans, it has been documented that many times the Native American people were purposely subjected to these diseases. In 1763, for instance, Lord Jeffrey Amherst ordered his subordinates to introduce smallpox to the Native American people through blankets offered to them (Plous, 2003).

This loss of population further impacted the Native American community due to the lack of public acknowledgment of these deaths by the dominant culture and the denial of Native Americans to properly mourn their losses. Mourning practices were disrupted when an 1883 federal law prohibited Native Americans from practicing traditional ceremonies (Brave Heart, Chase, Elkins, & Altschul, 2011). This law remained in effect until 1978, when the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was enacted. This disenfranchised grief has resulted in the Native American people not being able to display traditional grief practices (Brave Heart et al., 2011; Sotero, 2006). As a result, subsequent generations have been left with feelings of shame, powerlessness and subordination (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998).

The taking of Native American lands was a primary agenda for the majority of the United States government officials in the 19th century (Duran, 2006; Sue & Sue, 2012). President Andrew Jackson approved the Indian Removal Act of 1830, initiating the use of treaties in exchange for Native American land east of the Mississippi River and forcing the relocation of as many as 100,000 Native Americans (Plous, 2003). The motivation for the confiscation of the lands was often driven by economics (e.g., Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868; Trusty et al., 2002). By 1876, the U.S. government had obtained the majority of Native American land and the Native American people were forced to either live on reservations or relocate to urban areas (Brave Heart & Debruyn, 1998; Trusty et al., 2002). Reservations, for the most part, were not the best lands for agriculture and hunting. Further, being relocated to urban areas removed Native American people from all the lives they were familiar with. Leaving their domestic lands led to a decline in socioeconomic status as Native American men were not able to provide for their families, and the families became dependent on goods provided by the U.S. government (Brave Heart & Debruyn, 1998). These relocations resulted in the death of thousands of Native Americans and the disruption of families.

The agenda throughout the majority of history by U.S. government agencies, churches, and other organizations was to encroach on the Native American population and lands, leading to a disruption to the Native American culture for the preponderance of the Native population (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Garrett & Pichette, 2000). Principally, the intent was to force the Native American people to fully assimilate to the dominant European-American culture and completely abandon their own culture. In 1871 the U.S. congress declared Native Americans wards of the U.S. government, and the U.S. government’s goal became to civilize Native Americans and assimilate them to the dominant White culture (Trusty et al., 2002). Government and church-run boarding schools would take Native American children from their families at the age of 4 or 5 and not allow any contact with their Native American relations for a minimum of 8 years (Brave Heart & Debruyn, 1998; Garrett & Pichette, 2000). In the boarding schools, Native American children had their hair cut and were dressed like European American children; additionally, all sacred items were taken from them and they were forbidden to use their Native language or practice traditional rituals and religions (Brave Heart & Debruyn, 1998; Garrett & Pichette, 2000). Many children were abused physically and sexually and developed a variety of problematic coping strategies (e.g., learned helplessness, manipulative tendencies, compulsive gambling, alcohol and drug use, suicide, denial, and scapegoating other Native American children) (Brave Heart & Debruyn, 1998; Garrett & Pichette, 2000). Such circumstances led many Native Americans to not engage in traditional ways and religious practices, which led to a loss of ethnic identity (Garrett & Pichette, 2000). The removal of children from their families is considered one of the most devastating traumas that occurred to the Native American people because it resulted in the disruption of the family structure, forced assimilation of children, and a disruption in the Native American community. This situation is considered the crucial precursor to many of the existing problems for some Native Americans (Brave Heart & Debruyn, 1998; Duran & Duran, 1995).

Historical Loss Symptoms

The second core concept of the theory of historical trauma relates to the current social-environmental, psychological and physiological distress in Native American communities, in that these difficulties are a direct result of the historical losses this population has suffered. Specifically, these traumatic historical losses result in historical loss symptoms.

Societal-environmental concerns. Domestic violence and physical and sexual assault are three-and-a-half times higher than the national average in Native American communities; however, this number may be low, as many assaults are not reported (Sue & Sue, 2012). Cole (2006) proposed that the breakdown in Native American families due to the forced removal of Native American children can be seen as the reason for the high number of child abuse and domestic violence incidents reported in these families. Additionally, Native American children are one of the most overrepresented groups in the care of child protective services (Hill, 2008). Further, fewer Native Americans have a high school education than the total U.S. population; an even smaller percentage has obtained a bachelor’s degree: 11% compared with 24% of the total population. Almost 26% of Native Americans live in poverty compared to 12% for the entire U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006). Native Americans residing on reservations have double the unemployment rate compared to the rest of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2006).

Psychological concerns. Native Americans have the highest weekly alcohol consumption of any ethnic group (Chartier & Caetano, 2010). Native American adults reported that in the last 30 days, 44% used alcohol, 31% engaged in binge drinking, and 11% used an illicit drug (National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2010). Many Native American adolescents have co-occurring disorders related to substance abuse and mental health disorders (Abbott, 2006). Abuse of alcohol by Native individuals may be related to low self-esteem, loss of cultural identity, lack of positive role models, history of abuse and neglect, self-medication due to feelings of hopelessness, and loss of family and tribal connections (Sue & Sue, 2012).

Statistics indicate that a proportionally high level of Native Americans have mood disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; CDC, 2007; Dickerson & Johnson, 2012). Suicide rates among Native Americans are 3.2 times higher than the national average (CDC, 2007). For males ages 15–19, Native American suicide rates were 32.7 per 100,000, compared to non-Hispanic White (14.2), Black (7.4), Hispanic (9.9), and Asian or Pacific Islander (8.5) [CDC, 2007]. Studies have shown family disruptions and loss of ethnic identity places Native American adolescents at higher risk for alcoholism, depression and suicide (May, Van Winkle, Williams, McFeeley, DeBruyn, & Serma, 2002). It has been found that an increase in the number of suicides corresponds to a lack of linkage between the adolescents and their cultural past and their ability to relate their past to their current situation and the future (Chandler, Lalonde, Sokol, & Hallet, 2003).

Physiological concerns. The life expectancy at birth for the Native American population is 2.4 years less than that of all U.S. populations combined (CDC, 2010). Further, Native American individuals are overrepresented in the areas of heart disease, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and injuries with, diabetes being more prevalent with this population than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States (Barnes et al., 2010). Only 28% of Native Americans under the age of 65 have health insurance (CDC, 2010).

The majority (60%) of Native Americans receive behavioral and medical health services from Indian Health Services (IHS, 2013a). IHS was established and funded by the U.S. government in 1955 to uphold treaty obligations to provide healthcare services to members of federally recognized Native American tribes (Jones, 2006). Three branches of service exist within IHS: (a) an independent, federally operated direct care system, (b) tribal operated health care services, and (c) urban Indian health care services (Sequist, Cullen, & Acton, 2011). However, according to the IHS (2009), the Native American people “have long experienced lower health status when compared with other Americans.” This is substantiated by the IHS (2013a) report that $2,741 is spent per IHS recipient in comparison to $7,239 for the general population; of that, less than 10% of these funds were utilized for mental health and substance abuse treatment in 2010 even though the rates of mental health and substance abuse issues are prominent. This disparity in medical and behavioral health services is due to “inadequate education, disproportionate poverty, discrimination in the delivery of health services, and cultural differences” (IHS, 2013b). Further, Barnes and colleagues (2010) reported that the inequality may not only be related to the above factors, but epigenetic and behavioral influences. There may be environmental factors that alter the way genes are expressed (Francis, 2009) and behavioral patterns that further negatively influence the situation. In order to gain a better understanding of relationship epigenetic component, it is important to recognize how trauma impacts a person’s physical as well as mental functioning.

The Impact of Trauma on Physiological Functioning

“Traumatic experiences cause traumatic stress, which disrupts homeostasis” in the body (Solomon & Heide, 2005, p. 52). People who have experienced traumatic events have higher rates than the general population for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and gastrointestinal disorders (Kendall-Tackett, 2009). Specifically, trauma affects the functioning of the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system (Solomon & Heide, 2005). When the body is experiencing stress, it needs oxygen and glucose in order to fight or flee from the perceived danger. The brain then sends a message to the adrenal glands telling, them to release epinephrine (Kendall-Tackett, 2009). Epinephrine increases the amount of sugar in the blood stream, increases the heart rate and raises blood pressure. The brain also sends a signal to the pituitary gland to stimulate the adrenal cortex to produce cortisol that keeps the blood sugar high in order to give the body energy to be able to escape the stressor (Solomon & Heide, 2005). This physiological response to stress is created for a short-term remedy. Additionally, it has been found that in people who have experienced a prior trauma, their bodies react quicker to new stressors and thus cortisol and epinephrine are released at a faster rate (Kendall-Tackett, 2009).

Amygdala and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

Experiencing trauma can impact a person’s neurological functioning. After a traumatic event, many people have an overactive amygdala (Brohawn, Offringa, Pfaff, Hughes, & Shin, 2010). This hyperactivation of the amygdala “may be responsible for symptoms of hyperarousal in PTSD, including exaggerated startle responses, irritability, anger outbursts, and general hypervigilance,” and may be the reason for a person re-experiencing the event due to a trauma reminder (Weiss, 2007, p. 116). After the original trauma takes place, any perceived external threat that reminds the body of the original trauma (e.g., sound, face, smell, gesture) will cause the body, through the amygdala, to automatically respond to the perceived threat by producing epinephrine and cortisol (Weiss, 2007). This biological response happens without the person consciously being aware of it. It has been found that “emotionally arousing stimuli are generally better remembered than emotionally neutral stimuli, and the amygdala is responsible for this emotional memory enhancement” (Koenigs & Grafman, 2009, p. 546). The amygdala is responsible for giving emotional meaning to the external stimuli; however, the hippocampus provides contextual meaning to the stimuli (Brohawn et al., 2010).

Ganzel, Casey, Glover, Voss, and Temple (2007) examined whether trauma exposure has long-term effects on the brain and behavior in healthy individuals. These researchers compared a group of people who lived within 1.5 miles of the World Trade Center on 9/11 (Ground Zero) and a group of people who lived 200 miles away from Ground Zero. More than three years after the events of 9/11, both groups were shown pictures of fearful and calm faces; the amygdala activation of the group members was measured utilizing functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI; Ganzel et al., 2007). The results indicated that the group that resided closer to Ground Zero had heightened amygdala reactivity when shown images of people in fear.

In another study, researchers utilized fMRI to examine amygdala and hippocampus activation in 18 trauma-exposed non-PTSD control subjects and 18 individuals with PTSD (Brohawn et al., 2010). The results of this study indicated that there was hyperactive amygdala activation when negative emotional stimuli were introduced to the PTSD group. Additionally, when a person is exposed to traumatic events during development, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis can be altered, which may increase susceptibility to disease, including PTSD and other mood and anxiety disorders (Gillespie, Phifer, Bradley, & Ressler, 2009). The HPA axis is the part of the neuroendocrine system that controls reactions to stress as well as regulates digestion, the immune system, mood and emotions, and sexuality. This overactivation of the amygdala and HPA axis due to re-experiencing the initial trauma sends the message to the adrenal glands to release epinephrine and cortisol (Kendall-Tackett, 2009; Solomon & Heide, 2005). Current research has shown that the continual release of cortisol due to exposure to recurrent stressors, particularly during development, can cause the HPA axis to shutdown, which results in low cortisol levels (Neigh, Gillespie, & Nemeroff, 2009). Therefore, chronic exposure to stressors can relate to either a hypo- or hyper-stress response in the HPA axis.

This impact on the HPA axis functioning may explain why researchers have found a relationship between PTSD and physical illnesses. Weisberg et al. (2003) performed a study of 502 adults; 17% had no history of trauma, 46% had a history of trauma but no PTSD, and 37% were diagnosed with PTSD. The researchers found that individuals with PTSD reported a significantly larger number of current and lifetime medical conditions than did other participants, including anemia, arthritis, asthma, back pain, diabetes, eczema, kidney disease, lung disease, and ulcers (Schnurr & Green, 2004; Weisberg et al., 2003). Specifically, a multiple regression indicated that PTSD was a stronger predictor of medical difficulties than physical injury, lifestyle factors, or comorbid depression (Weisberg et al., 2003). A study of veterans found that those participants with PTSD were more likely to have the medical conditions of osteoarthritis, diabetes, heart disease, comorbid depression, and obesity (David, Woodward, Esquenazi, & Mellman, 2004). Additionally, Goodwin and Davidson (2005) conducted a survey study of over 5,500 subjects and found that there was an association between a diagnosis of diabetes and having PTSD.

Integrating Historical Trauma Theory

As evidenced above, the traumas inflicted on the Native American people (historical losses) are well documented and the literature provides significant information regarding the current psychological, environmental-societal, and physiological problems facing the Native American people (historical loss symptoms). The literature also supports the conceptualization of a relationship between experiencing trauma and the brain remembering the trauma when confronted by an emotional meaning stimulus (Brohawn et al., 2010; Weiss, 2007). Further, a relationship between PTSD and physiological functioning has been found (David et al., 2004; Weisberg et al., 2003). Therefore, it can be surmised that, given the substantial historical traumas Native Americans have experienced, they would be at greater risk of developing physical and emotional concerns related to re-experiencing these traumas. However, the question remains whether some Native American people are being confronted by emotionally significant stimuli in the present day that causes them to reflect about the historical traumas that occurred many generations ago.

In answer to this question, Whitbeck and colleagues (2004) developed the Historical Loss Scale and the Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale. Whitbeck et al. (2004) surveyed Native American adult parents of children for their perceptions of historical events. These participants were generations removed from many of the historical traumas that had been inflicted on the Native American people. However, 36% had daily thoughts about the loss of traditional language in their community and 34% experienced daily thoughts about the loss of culture (Whitbeck et al., 2004). Additionally, 24% reported feeling angry regarding historical losses, and 49% provided they had disturbing thoughts related to these losses. Almost half (46%) of the participants had daily thoughts about alcohol dependency and its impact on their community. Further, 22% of the respondents indicated they felt discomfort with White people, and 35% were distrustful of the intentions of the dominant White culture due to the historical losses the Native American people had suffered (Whitbeck et al, 2004).

Ehlers, Gizer, Gilder, Ellingson, & Yehuda (2013) utilized the Historical Loss Scale and Historical Loss Associated Symptoms Scale to survey 306 Native American adults. The majority of the participants thought about historical losses at least occasionally and these thoughts caused them distress. In particular, how frequent a person thought about historical losses was linked with not being married, high degrees of Native heritage and cultural identification. When comparing the Whitbeck et al. (2004) and Ehlers et al. (2013) studies, about the same percentage of participants thought about the losses several times a day; however, respondents reported less daily and weekly thoughts of historical losses in the Ehlers et al. (2013) results. The differences between the two studies could be a result of “the extent of historical losses suffered by each individual Native community, the impact of current trauma, levels of acculturation, population norms about historical losses, and population admixture” (Ehlers et al., 2013, p. 6). Therefore, it is important to recognize there are differences in how historical losses are impacting Native American communities.

The above findings may clarify one reason why some populations in the Native American community are suffering from such severe emotional, physical and social-environmental consequences related to past traumas. Specifically, their bodies’ ability to deal with stress has been overwhelmed by the reoccurring thoughts related to historical losses they have suffered. However, it is important not to make generalizations and to remember not all of the Native American people have been experiencing severe historical loss symptoms (Evans-Campbell, 2008). These within-group differences in the Native American population would explain the variances in rates of disease, child abuse and neglect, violence, suicide, unemployment, familial disruption, and poverty between tribal affiliations.

Another important consideration is an individual’s perception of being discriminated against. Perceived discrimination has been associated with negative health consequences (Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, Landrine, Klein, & Sticklor, 2011). In particular, Capezza, Zlotnick, Kohn, Vicente, and Saldivia (2012) administered structured diagnostic assessments for major depressive disorder (MDD) and PTSD and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) to 2,839 participants in Concepción and Talcahuano, Chile. These researchers found that controlling for demographic variables and previous trauma, participants who reported discrimination in the preceding six months were significantly more likely to participate in risky alcohol use, illegal drug use, and be diagnosed with MDD and PTSD than respondents not reporting discrimination.

Another study examined the relationships between neglect and abuse, PTSD symptoms, ethnicity-specific factors (e.g., ethnic orientation, ethnic identity, perceived discrimination), and alcohol and drug problems within adolescent girls (Gray & Montgomery, 2012). These researchers found that abuse and neglect were correlated to alcohol and drug problems, but only in relation with PTSD symptoms. It also was found that greater perceived discrimination was related with an increased influence of abuse and neglect on PTSD symptoms (Gray & Montgomery, 2012). Given the generations of persecution, discrimination, and oppression suffered by the Native American people (Brave Heart et al., 2011), it is reasonable that perceived discrimination could be an aggravating factor.

Cross-Generational Trauma Transmission

As a result of the loss of people, land, and culture, a systematic transmission of trauma to subsequent generations occurred that has resulted in historical loss symptoms for many Native American individuals (Brave Heart et al., 2011; Whitbeck et al., 2004). Specifically, the traumatic events suffered during previous generations creates a pathway that results in the current generation being at an increased risk of experiencing mental and physical distress that leaves them unable to gain strength from their indigenous culture or utilize their natural familial and tribal support system (Big Foot & Braden, 2007). Therefore, the next step in investigating the theory of historical trauma is to understand how the generational transmission of trauma transpires. Significant research has been completed on the cross-generational transmission of trauma regarding Holocaust victims and their descendants (Doucet & Rovers, 2010; Jacobs, 2011; Neigh et al., 2009; Yehuda, Schmeidler, Wainberg, Binder-Brynes, & Duvdevani, 1998).

Based upon this research, three means by which trauma is transmitted to subsequent generations have been identified: (a) children identifying with their parents’ suffering, (b) children being influenced by the style of communication caregivers use to describe the trauma, and (c) children being influenced by particular parenting styles (Doucet & Rovers, 2010). Parental identification is a form of vicarious learning in which the child identifies with trauma and takes on the historical loss symptoms. Lichenstein and Annas (2000) found there is a relationship between a parent having a fear and children developing the same fear due to vicarious learning. This seems to be substantiated by Myhra’s (2011) findings that all 13 participants in a qualitative study examining the relationship between substance use and historical trauma in Native American adults believed that historical trauma was key to their elders’ dysfunctional behavior—in particular, substance abuse. One participant characterized it as “monkey see, monkey do,” in that she was following her family’s pattern of abusing substances and being involved in abusive interpersonal relationships (Myhra, 2011, p. 26). However, it is important to mention that participants also expressed a great respect and admiration for their elders due to their strength and resiliency.

Lichenstein and Annas (2000) also examined if the way parents relayed information to children regarding a stimulus impacted the development of a fear or phobia in the children. The researchers found that there was a relationship between children developing a fear or phobia when parents engaged in negative talk with children regarding the stimulus. In the Native American culture, information and history is often passed down from generation to generation in a narrative summary. Given that the atrocities that were inflicted on the Native American people were substantive, it seems understandable that transmission of historical loss symptoms could occur via this pathway to the children. In fact, Myhra (2011) found that Native American participants connected “the impact of elders’ stories of historical trauma and loss, and their own traumatic experiences, to intrusive thoughts about these ordeals and to fear that trauma will continue for future generations” (p. 25).

Parenting style also can be impacted as a result of trauma. Walker (1999), in completing an extensive literature review of this subject, found that parenting can be impacted as a result of the parental exposure to trauma. First, parents may have difficulty with trust and intimacy as a result of their experiences of being victimized. Therefore, it may be a challenge for them to develop a healthy attachment with their children. Second, many adults who have been subjected to abuse and neglect may in turn unintentionally enter into a cycle of violence with their own children (Walker, 1999). Due to the forced removal of Native children from their homes and tribal communities, the familial structure was interrupted and many suffered extreme abuse and neglect (Cole, 2006). Therefore, subsequent generations of Native Americans may have not been able to develop healthy parenting styles and inadvertently continued a cycle of violence and abuse. A relationship between a parent’s diagnosis of PTSD and abuse and neglect of children also has been found. Children of Holocaust survivors diagnosed with PTSD report more neglect and emotional abuse than demographically similar children of parents who were not diagnosed with PTSD (Neigh et al., 2009; Yehuda, Bierer, Schmeidler, Aferiat, Breslau, & Dolan, 2000). The reasons why Native American children stand overrepresented in the U.S. foster care system (Hill, 2008) may be related to the abuse suffered by many Native Americans while in boarding schools and the high number of Native Americans displaying PTSD symptoms.