Nov 12, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Jeffrey M. Warren, Leslie A. Locklear, Nicholas A. Watson

This study explored the relationships between parenting beliefs, authoritative parenting style, and student achievement. Data were gathered from 49 parents who had school-aged children enrolled in grades K–12 regarding the manner in which they parent and their child’s school performance. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients and multiple regression modeling were used to analyze the data. Findings suggested that parent involvement, suspension, and homework completion significantly accounted for the variance explained in grade point average. Authoritativeness was positively and significantly related to both rational and irrational parenting beliefs. Irrational parenting beliefs were positively and significantly related to homework completion. School counselors are encouraged to consider the impact of parenting on student success when developing comprehensive programming.

Keywords: student achievement, homework completion, irrational parenting beliefs, authoritative parenting, school counseling

There are many indicators of success as students matriculate through elementary, middle, and high school. Student success is generally defined by the degree to which students meet or exceed a predetermined set of competencies (York, Gibson, & Rankin, 2015). These competencies are often academic in nature and align with state curriculum. Data collected at numerous points (i.e., formal and informal assessment) throughout an academic year are used to monitor student performance. Student achievement data, including end-of-grade tests and grade point average (GPA), are key determinants of student outcomes such as promotion or retention (Schwerdt, West, & Winters, 2017). Although both are distal data points that measure achievement, GPA is a cumulative measure of student performance based on mental ability, motivation, and personality demonstrated throughout the course of a school year (Imose & Barber, 2015; Spengler, Brunner, Martin, & Lüdtke, 2016).

Numerous factors are related to and impact student achievement. According to Hatch (2014), these factors include discipline referrals, suspension, homework completion, and parental involvement. Research suggests that these factors are good indicators of distal or long-term academic success (Kalenkoski & Pabilonia, 2017; LeFevre & Shaw, 2012; Noltemeyer, Ward, & Mcloughlin, 2015; Roby, 2004). Although it is a challenge to determine student progress based on GPA alone, these variables can be monitored across the school year for a real-time snapshot of student success (Hatch, 2014).

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA; 2012) has suggested that school counselors work to promote student success by operating across three distinct areas or domains: academic, social and emotional, and career development. As such, school counselors play an integral role in developing, delivering, and evaluating programs that promote academic achievement. School counselors are challenged to determine the direct impact of services on student achievement. Student achievement–related data can be measured to understand the impact of school counseling interventions. For example, a study skills curriculum such as SOAR® (SOAR Learning Inc., 2018) may increase homework completion by 20%. School counselors can infer that the intervention will lead to increases in student achievement; literature suggests homework completion is positively correlated with GPA (Kalenkoski & Pabilonia, 2017).

Although school counselors often work directly with students, they also can engage in efforts to promote student achievement through work with parents and families. For example, Ray, Lambie, and Curry (2007) suggested school counselors can offer parenting skills training to promote positive parenting practices. Other authors have advocated to strengthen the partnerships with and involvement of parents, which are factors related to student achievement (Bryan & Henry, 2012; Epstein, 2018). In developing interventions that aim to build partnership and increase involvement, it is important for school counselors to understand the values, assumptions, beliefs, and behaviors of parents (Bryan & Henry, 2012). During the initial stages of partnering with families, school counselors should address any biases and assumptions that may impede the partnership (Warren, 2017). Furthermore, strategies and interventions should be data-driven and aim to promote student achievement (Hatch, 2014). In the current study, researchers examined the relationships between parenting beliefs, authoritative parenting style, and student achievement. School counselors who understand the relationships between these factors are best positioned to meet the needs of all students.

Parenting Beliefs

The beliefs parents maintain are especially pertinent to the overall wellness and success of their children (Warren, 2017). At times, parents may place unreasonable demands on themselves, their children, or the practice of parenting in general. For example, a parent may think, “My child should always do what I say, and I cannot stand it otherwise.” This belief can have a detrimental impact on the parent–child relationship and family unit as well as the psychosocial development of the child (Bernard, 1990).

Rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), developed by Ellis (1962), emphasizes two main types of thoughts pertinent to the beliefs of parents: rational and irrational. Rational thoughts are flexible and preferential in nature. These thoughts lead to healthy emotions and functional behaviors. Alternatively, irrational beliefs are rigid and dogmatic and stem from demands placed on the self, others, and life. “Life should always treat me fairly and it is horrible when it does not,” is an example of an irrational belief. This belief can lead to unhealthy emotions (e.g., anger, depression) and result in unhelpful or dysfunctional behavior.

A central goal of REBT is to advance acceptance of the self, others, and life in general. In turn, individuals are encouraged to abstain from global evaluations or rating the self, others, or life as totally bad. When striving toward acceptance, individuals are happier and more successful in life (Dryden, 2014). Researchers have studied REBT and associated constructs among various populations, including children (Gonzalez et al., 2004; Sapp, 1996; Sapp, Farrell, & Durand, 1995; Warren & Hale, 2016), teachers (Warren & Dowden, 2012; Warren & Gerler, 2013), college students (McCown, Blake, & Keiser, 2012; Warren & Hale, in press), and parents (Terjesen & Kurasaki, 2009; Warren, 2017). Literature suggests a strong correlation between irrational beliefs and dysfunction, regardless of the measure used or sample under investigation.

Findings from Hamamci and Bağci (2017) have suggested that a relationship exists between family functioning and the degree to which parents hold irrational expectations about their children. Emotional support and responsiveness of parents deteriorate with an increase in irrational beliefs. Additionally, child behavior issues are more prevalent when parents think irrationally. Hojjat et al. (2016) found that children are more susceptible to substance abuse when their parents maintain irrational beliefs and unrealistic expectations. Parenting styles that advance unrealistic or irrational academic expectations may stifle academic success and promote the development of irrational beliefs and unhealthy negative emotions (e.g., anxiety) in children (Kufakunesu, 2015).

Parenting Styles

Parenting style is most often used to broadly describe how parents interact with their children. In 1966, Diana Baumrind presented three major parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive. Later, Maccoby and Martin (1983) identified a fourth style of parenting: neglectful. Parenting styles are defined by collections of attitudes and behaviors expressed to children by their parents (Darling & Steinberg, 1993) and are often based upon the degree of demandingness/control and responsiveness. Parents who maintain an authoritarian parenting style are highly demanding, yet emotionally unresponsive, while authoritative parents exude high demands, but are communicative and responsive (Baumrind, 1991). Permissive parents, on the other hand, are responsive, yet lack firm control of their children; neglectful parenting involves a lack of emotional support as well as little control (Pinquart, 2016).

The manner in which parents parent can impact their child’s success in school. Of the four parenting styles described, research findings suggested that models of parenting aligning with the authoritative parenting style are most closely linked to student achievement (Carlo, White, Streit, Knight, & Zeiders, 2018; Castro et al., 2015; Kenney, Lac, Hummer, Grimaldi, & LaBrie, 2015; Masud, Thurasamy, & Ahmad, 2015). Additionally, the impact of parenting style on student success seems to vary little across culture. A meta-analysis conducted by Pinquart and Kauser (2018) suggested that children across the world may benefit academically from authoritative parents. Although a plethora of evidence supporting this relationship exists, a meta-analysis conducted by Pinquart (2016) found a small effect size, suggesting the relationship between authoritative parenting and student achievement is minimal. Regardless, the manner in which parents interact with their children impacts many aspects of child development, including their ability to succeed in school.

Purpose of the Study

This article explores the relationships between parenting beliefs, styles, and student achievement. Ellis, Wolfe, and Moseley (1981) suggested parents’ behaviors stem from their thoughts and emotions. These beliefs impact the manner in which parents interact with their children. For example, parents who hold rigid or extreme beliefs may respond to their children more negatively than parents who maintain a flexible belief system. As such, parenting beliefs may impact parenting style, and therefore the success of students. However, the literature is scant when exploring the relationships between parenting beliefs, parenting style, and student achievement.

In order to work effectively with parents, it is important that school counselors understand parenting beliefs and styles and their impact on student achievement. Several research questions guided this study, including: (a) Is there a relationship between student achievement and parental involvement, homework completion, discipline referrals, and suspensions?; (b) Is authoritative parenting related to student achievement?; and (c) Are parenting beliefs related to student achievement? Based on these research questions and existing literature, the following hypotheses were generated: Hypothesis #1: A significant relationship exists between GPA and student achievement–related variables. Hypothesis #2: Rational, irrational, and global evaluation parenting beliefs are predictive of authoritative parenting. Hypothesis #3: Authoritative parenting is significantly positively related to student achievement. Hypothesis #4: Parenting beliefs are significantly related to student achievement–related variables.

Method

Participants

This study included parents living in the southeastern United States (N = 49) who self-reported having children enrolled in elementary, middle, or high school. Of the participants, 96% (n = 47) were mothers, while 4% (n = 2) were fathers. Regarding race and ethnicity, 45% (n = 22) identified as White, 41% (n = 20) identified as American Indian, 8% (n = 4) identified as African American, and 6% (n = 3) identified as Hispanic/Latino. The mean age of the participants’ children was 11 years old; ages ranged from 5 to 18. All grade levels (K–12) across elementary (n = 28), middle (n = 6), and high school (n = 15) were represented, with second grade represented most frequently.

G*Power 3.1, developed by Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, and Bucher (2007), was utilized during an a priori power analysis. The author conducted the power analysis to ascertain the minimum number of participants needed to reach statistical significance, should it exist among the variables under investigation. With statistical power set at .80 and alpha level set at .05, the analysis produced a minimum sample size of 40. This sample size was large enough to detect a medium effect size

(f2 = .35). As a result, the sample size was sufficient to explain the relationships between the predictor and criterion variables.

Instruments

The parents who participated in this study completed a demographic questionnaire and two surveys. The demographic questionnaire, developed by the first author, captured race/ethnicity and gender of the parent in addition to the level of involvement in their child’s schooling. Student achievement–related questions also were asked to capture the age of the participant’s child, grade level, GPA, homework completion percentage, and number of discipline referrals and suspensions. Participants responded to questions such as, “What percentage of your child’s homework is completed on a weekly basis?” Other surveys utilized in this study include the following.

Parental Authority Questionnaire–Revised (PAQ-R; Reitman, Rhode, Hupp, & Altobello, 2002). The PAQ-R is a 30-item self-report measure of parenting style. The PAQ-R is a revision of the Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAR; Buri, 1991) and is grounded in the work of Baumrind (1971). Three subscales, Authoritarian, Authoritative, and Permissive, comprising 10 items each, assess the degree to which parents exhibit control, demand maturity, and are responsive and communicative with their child. Participants indicate their level of agreement with statements such as, “I tell my children what they should do, but I explain why I want them to do it” using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Findings from a study conducted by Reitman et al. (2002) suggested that the PAQ-R is a reliable measure of authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting styles when considering respondents’ demographic characteristics such as socioeconomic status or race. The Authoritarian (r = .87), Authoritative, (r = .61), and Permissive (r = .67) subscales of the PAQ-R have good test-retest reliability at one month. The Authoritarian (r = .25) and Authoritative (r = .34) subscales were positively correlated with the Communication subscale of the Parent-Child Relationship Inventory (Gerard, 1994), suggesting convergent validity. Across three distinct samples of parents, coefficient alphas ranged from .72 to .76 for Authoritarian, .56 to .77 for Authoritative, and .73 to .74 for Permissive, demonstrating internal consistency (Reitman et al., 2002).

In the current study, only the Authoritative subscale was used. The demographic characteristics of participants in Sample A in a study conducted by Reitman et al. (2002) most closely aligned with the sample in the present study. Factor loadings for Sample A were identical to the Authoritative subscale of the original PAR and therefore used in this study. For the present study, the Authoritative subscale has an internal consistency of .69.

Parent Rational and Irrational Belief Scale (PRIBS; Gavita, David, DiGiuseppe, & DelVecchio, 2011). The PRIBS was used in this study to assess participants’ beliefs related to their child’s behavior and parenting roles. The self-report instrument contains a total of 24 items; four are control items. Three subscales, Rational Beliefs (RB), Irrational Beliefs (IB), and Global Evaluation (GE), comprise the remaining 20 items. The RB subscale contains 10 items and assesses the degree to which preferential and realistic thoughts related to parenting are maintained. The IB subscale includes six items and evaluates the demands parents place on themselves and their child. The GE subscale comprises four items and assesses the degree to which parents globally rate themselves or their children.

A 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) is used to respond to items such as, “My child must absolutely respect and obey me.” Scores on the PRIBS generally range from 39 (very low) to 60 (very high). The PRIBS and its subscales are significantly correlated with other measures of irrationality and negative emotion, including the General Attitudes and Beliefs Scale-Short Form (Lindner, Kirkby, Wertheim, & Birch, 1999) and the Parental Stress Scale (Berry & Jones, 1995). Gavita et al. (2011) suggested the PRIBS is a reliable measure of parent irrationality; test-retest reliability (r = .78) for the full scale was acceptable after two months. Internal consistency for the PRIBS was .73. The coefficient alphas for RB, IB, and GE were .83, .78, and .71, respectively. For the current study, an internal consistency coefficient of .46 was found for the PRIBS. Additionally, coefficient alphas for the subscales are .62 (RB), .80 (IB), and .43 (GE). All PRIBS subscales were used in this study.

Procedure

A review of literature was conducted in an effort to identify the measures for use in this study. Additionally, a brief demographic instrument was developed to obtain relevant parent and child demographic information. Qualtrics survey software was utilized to prepare the survey packet (i.e., informed consent, demographic questionnaire, and surveys) for electronic dissemination. An application to complete the study then was submitted for review to the institutional review board (IRB) at the researchers’ university. Upon IRB approval, the researchers disseminated an electronic message containing a link to the research packet via a graduate counseling student listserv. An email also was distributed to staff who worked in the School of Education at the researchers’ university. The email contained a request for parents of K–12 students to participate in the study; recipients also were asked to forward the email to family, friends, and colleagues. The email was disseminated on three occasions across two weeks. Participants who completed the study were entered into a drawing for a chance to win $50.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

In order to gain a better understanding of the student achievement–related data collected during this study, initial analyses were conducted. Prior to analysis, GPA was calculated using a letter grade–GPA conversion table; parents reported letter grades on the survey. As such, grades of A+, A, and A- equated to GPAs of 4.33, 4.0, and 3.67, respectively. The student achievement–related variables included in the initial analyses were parental involvement, discipline referrals, suspensions, and homework completion.

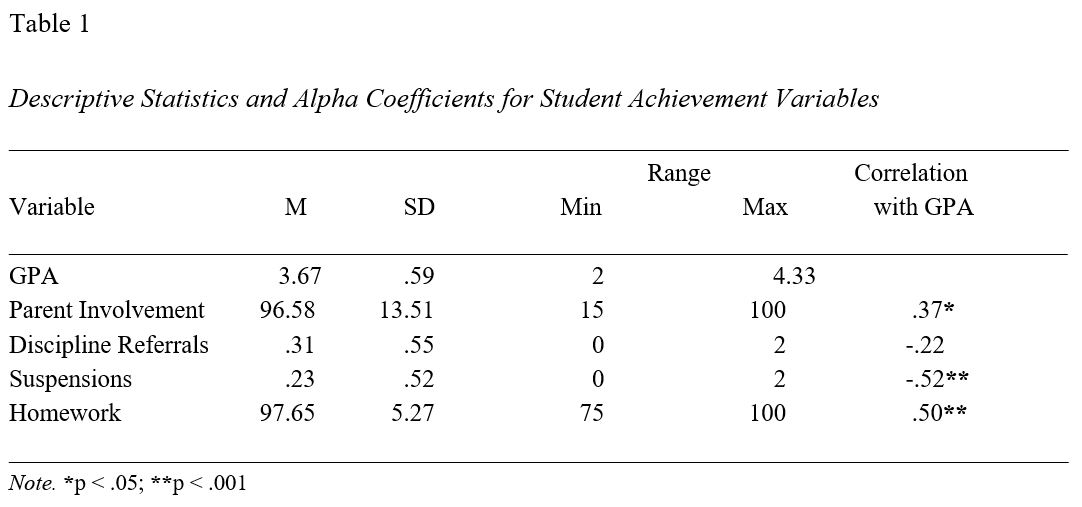

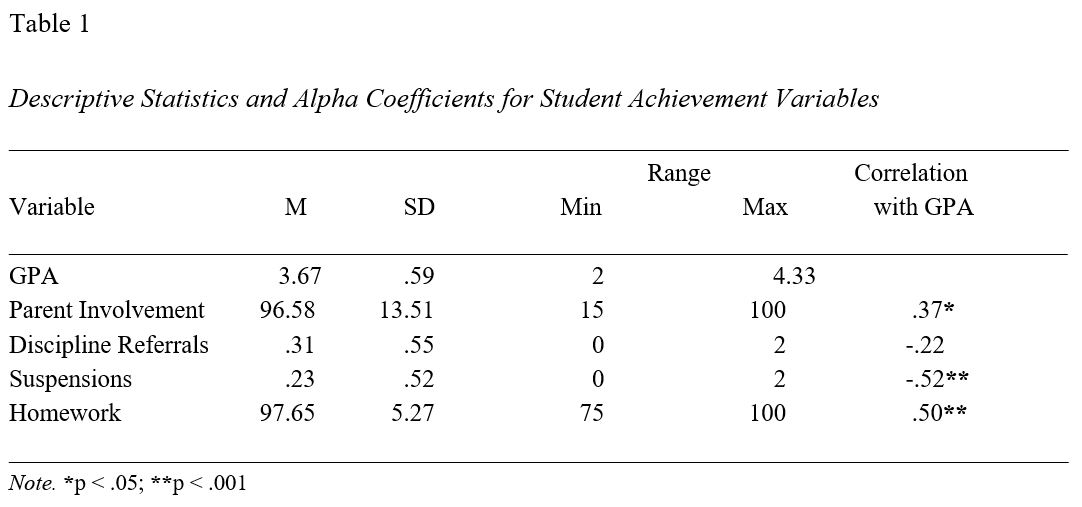

Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients and multiple regression analyses were used to test the hypothesis that GPA is related to and predicted by these student achievement–related variables. The degree of parental involvement and homework completion were positively and significantly related to GPA. Suspensions were negatively and significantly related to GPA. Discipline referrals were not significantly related to GPA. The descriptive statistics and correlations for these variables are offered in Table 1.

Prior to additional analysis, basic assumptions of multiple regression analysis were tested and satisfied. Standardized residual plots and Q-Q plots were inspected; bivariate correlations also were examined. Next, a multiple regression analysis including parent involvement, suspensions, and homework completion as predictors was conducted with GPA as the criterion variable. Discipline referrals were not included in the regression analysis. A significant regression equation was found: F(3, 45) = 11.539, p < .001. The model with these three predictors explained a significant amount of the variance in GPA (R2 = .435). Significant contributions were made to the model by each of the three predictor variables: parent involvement (β = .284, p < .05), suspensions (β = -.369, p < .05), and homework completion (β = .273, p < .05).

Main Analyses

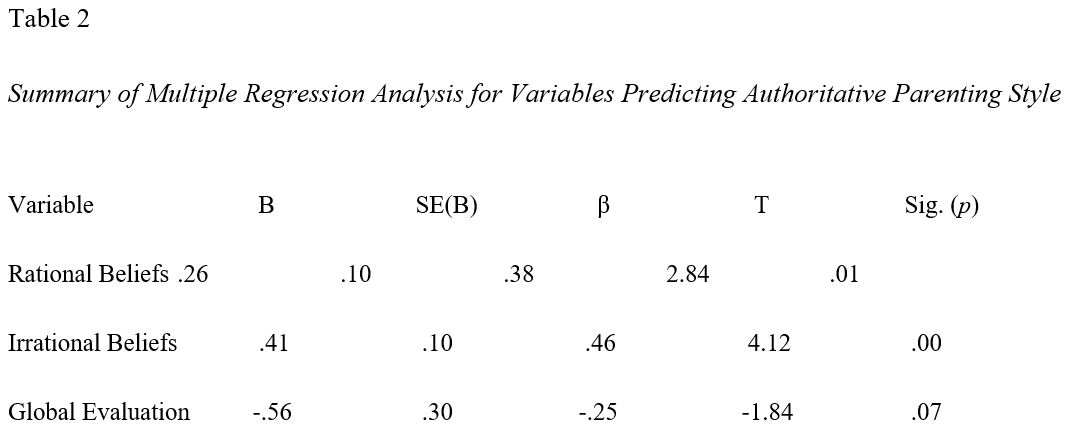

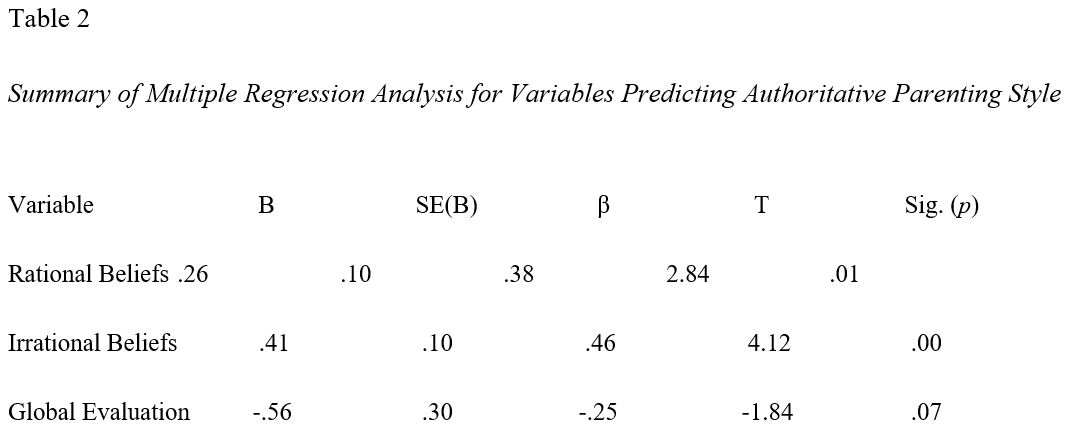

A multiple linear regression was used to test the hypothesis that authoritative parenting is predicted by parenting beliefs. Authoritative parenting served as the criterion variable. RB, IB, and GE were predictor variables. A combination of these predictor variables yielded a significant regression equation: F(3, 38) = 14.536, p < .000. The model explained a significant portion of variance (53%) in authoritative parenting (see Table 2). Additionally, RB (β = .38, p < .05) was positively and significantly related to authoritative parenting. IB (β = .46, p < .001) also was positively and significantly correlated with authoritative parenting. GE did not contribute significantly to the model (β = -.25 p > .05).

A simple linear regression was performed to test the hypothesis that authoritative parenting predicts student achievement. Based on prior research findings that suggest authoritative parenting is related to positive student achievement, authoritative parenting served as a predictor variable; the criterion variable was GPA. Output from the analysis revealed that authoritative parenting did not predict GPA for this sample of parents: F(1, 40) = .642, p > .05.

Finally, the hypothesis that parenting beliefs predict student achievement–related variables was tested using multiple linear regression modeling. IB, RB, and GE were predictor variables and parent involvement, suspension, and homework completion were criterion variables. A combination of these predictor variables yielded a non-significant regression equation when parental involvement was the criterion variable: F(3, 37) = 1.773, p = .169. Suspensions were not predicted by RB, IB, or GE: F(3, 37) = 1.232, p = .312. Finally, a combination of these predictor variables yielded a non-significant regression equation when homework completion was the criterion variable: F(3, 37) = 2.382, p = .085. Although this model did not explain variance in homework completion, IB was positively and significantly related to homework completion: t(39) = 2.34, p = .025; β = .357.

Discussion

The hypotheses put forth based on previous research and literature were supported and refuted in various instances based on the analyses of the data collected. In regard to the first hypothesis, all student achievement–related factors except discipline referrals were significantly related to GPA. This finding is consistent with research that explores the relationships of proximal student achievement–related factors and distal student achievement outcomes. Parental involvement in their child’s schooling, homework completion, and suspensions are predictors of GPA. Each of these variables contributed to the overall model for predicting student achievement. This finding demonstrates the value of parental involvement and homework completion in the success of students. Additionally, the negative impact of suspension on the academic achievement of students is highlighted. This outcome signals the importance of fostering safe and inviting schools and establishing policies that offer alternatives to suspension unless absolutely necessary.

The second hypothesis purported that authoritative parenting is significantly related to RB, IB, and GE. This hypothesis was supported; combined, RB, IB, and GE predicted authoritative parenting. Research findings suggest that authoritative parenting is related to student achievement, so it is counterintuitive that both RB and IB are positively related to authoritativeness. IB typically lead to dysfunction rather than positive outcomes such as student achievement (Terjesen & Kurasaki, 2009). However, according to Reitman et al. (2002) and others, authoritative parents are demanding, yet supportive of their children. The demandingness described in this parenting style may be a derivative of irrational thinking, as evidenced by the significant contribution of IB to the model. As suggested by Bernard (1990), parents who place rigid demands on their children may be less supportive; effective communication also may fluctuate. It is likely that an acceptable balance of demands, free of unrealistic, rigid expectations, coupled with support, is most effective when considering the role of authoritative parenting on student achievement. Excessive or unrealistic demands may lead to increases in student achievement, but at the expense of the parent–child relationship as well as mental health. In turn, these demands may serve as a barrier to home and school success (Terjesen & Kurasaki, 2009; Warren, 2017).

Closely tied to the second hypothesis, the third hypothesis suggested that authoritative parenting is significantly positively related to student achievement. Based on the data set analyzed, this hypothesis was not supported. This finding is inconsistent with previous research, which stated that the authoritative parenting style correlates to positive student achievement. In a meta-analysis conducted by Pinquart (2016), a small effect size was found in the relationship between authoritativeness and student achievement. It is possible that a significant relationship exists, yet was not found in this study because of a small sample size. Alternatively, authoritative parenting was not related to student achievement, a finding contrary to Pinquart (2016). Demographic variables such as race/ethnicity of participants (e.g., 40.8% American Indian) were not accounted for in this study and also may have implications for the findings.

The final hypothesis indicated that parenting beliefs are significantly related to student achievement–related variables; this hypothesis was partially supported. Although parenting beliefs were not predictive of parental involvement or suspensions, IB were significantly related to homework completion. Students who consistently complete their homework appear to have parents who maintain IB. Although homework completion is important and leads to academic achievement (Kalenkoski & Pabilonia, 2017), according to REBT, irrational thinking is unproductive and leads to unhealthy negative emotion and dysfunctional behaviors (Dryden, 2014). In some instances, it is possible that parents model unhelpful psychosocial processes (e.g., irrational thinking, anger, yelling) when facilitating the completion of their child’s homework. This may lead to rifts in the parent–child relationship and a general disdain for doing homework, especially that which is difficult or challenging. As such, it is important for parents to set realistic, high expectations for homework completion. These expectations should be based on the child’s strengths and weaknesses, clearly communicated, and consistently followed. Parents are encouraged to hold their children accountable without placing demands on themselves, their child, or the homework process in general (Warren, 2017).

Overall the data from this study presented interesting findings related to authoritative parenting style, beliefs, and student achievement. Certain factors such as homework completion and parental involvement were positively related to GPA; school suspension had a negative impact on GPA. Although these findings are not novel, consideration for the relationships between authoritativeness, parent beliefs, and student achievement in this investigation is noteworthy. Although homework completion was positively related to GPA, it also was correlated with IB. In combination, these findings provide an interesting perspective on the ways in which authoritativeness is related to parenting beliefs, which, in turn, appear to influence homework completion, a key determinant of positive distal student achievement outcomes. Although limitations exist, this study can help to facilitate the development of additional research and offers practical implications for school counselors.

Limitations

As suggested, there are several limitations of this study. When considering the generalizability of these results and potential implications for practice, readers should account for the method of data collection and the sample used in this study. First, data were gathered using self-report measures. Because of the nature of the questions asked on the survey, parents participating in this study may have provided socially desirable responses rather than indicating their actual parenting beliefs and behaviors. Additionally, the sample size was small, yet it was sufficiently sized to detect moderate effects. A convenience sample was used and likely is not representative of the general population. Students and faculty affiliated with a university listserv were contacted and asked to participate and disseminate the study information to their family and friends. A larger sample size would have increased the generalizability of these results and yielded greater power, including the ability to detect smaller effect sizes among the variables.

Future Research

Research investigating parenting styles, beliefs, and student achievement variables such as discipline referrals, suspension, and homework completion is sparse. This study offers a foundation for future empirical and action-based research in this area. Researchers initially are encouraged to replicate this study using a larger, more representative sample of parents with school-aged children. Replication may shed additional light on the strengths of the relationships of the variables explored in this study. Given the achievement gap, including the disproportionate suspension rates that exist in K–12 schools among students of color, it is especially important for researchers to explore the impact of parenting styles and beliefs on the achievement of students from historically underrepresented backgrounds. The American Indian population, specifically, is largely absent in research that explores factors of K–12 student success, yet over 500,000 American Indian students are enrolled in schools across the nation (Snyder, de Brey, & Dillow, 2018). This lack of research is a barrier for school counselors and other educators who seek to better support and understand American Indian families and students. Research that explores these relationships within and across specific racial/ethnic groups, including African American, Hispanic/Latino, and American Indian, can serve as a catalyst for school counselors to enhance service delivery and meet the needs of all students.

Researchers also are encouraged to explore the effects of targeted parenting interventions, such as rational emotive-social behavioral (RE-SB) consultation (Warren, 2017) on parenting and student achievement. School counselors can implement large group, small group, or individual RE-SB consultation with parents to address IB and promote student success (Warren, 2017). School counselors, in collaboration with researchers, can play a central role in the development, delivery, and evaluation of parenting interventions that aim to promote student success; these efforts also can further establish evidence-based practice in school counseling.

Implications for School Counselors

According to the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2012), school counselors play an integral role in supporting the academic, social-emotional, and career development of all students through work with various stakeholders, including students, teachers, and parents. The findings of this study offer insight into the connection between parenting and student success. Operating in the academic domain, school counselors can deliver direct and indirect services to support the success of all students. The recommendations provided below serve to guide school counselors in identifying and delivering targeted programming that yields positive student outcomes.

A broad strategy for promoting academic success involves the establishment of a comprehensive school counseling program that includes interventions that aim to increase homework completion, decrease suspension rates, and increase parental involvement. As the findings of this study suggest, these factors have a direct impact on student achievement. Therefore, school counselors should leverage their roles as leaders, advocates, and consultants to ensure students are adequately supported by parents and positioned by their teachers to meet the daily expectations of school.

As educational leaders, school counselors are encouraged to engage parents, teachers, administrators, and students in ongoing, critical discussion about the relationships between student achievement–related factors and GPA. Classroom guidance, staff development sessions, and parent workshops are viable opportunities to disseminate this information and engage stakeholders. School counselors can involve teachers and administrators in discussions surrounding classroom and school policies and procedures that impact homework completion, suspension, and parent involvement. Leveraging student and school data during these conversations are more likely to lead to classroom and school policy revisions that accommodate all students and their families. When school counselors collaborate with teachers and administrators, innovative strategies and support structures to promote homework completion and alternatives to suspension will emerge.

School counselors also can use the findings of this study to increase their awareness of the values and beliefs of parents. Used within the context of culture, these findings can offer school counselors additional insights that may be useful when working with parents. For instance, when working with American Indian families, school counselors should consider how customs and traditions impact the manner in which parents engage with their children (Castagno & Brayboy, 2008). By understanding the culture of students and families while considering parenting styles and beliefs, school counselors can partner with parents in intentional ways in an effort to promote student achievement. It is especially important to consider strategies to engage parents who may experience barriers to visiting school. School counselors can seek community resources and partnerships that can be leveraged to increase parental involvement. Using asset mapping as promoted by Griffin and Farris (2010), school counselors can help parents connect to school via the workplace, church, or community centers.

School counselors are encouraged to work closely with parents to establish programming that best supports parents’ efforts to help their children succeed. RE-SB consultation, as described by Warren (2017), is a viable service to educate parents about parenting styles and the impact of their thoughts on emotions and behaviors. For example, school counselors can hold a workshop for parents during a PTA event to promote rational thinking. “Rational reminders” disseminated via the school’s social media account also can be useful for parents not familiar with REBT who are attempting to set realistic expectations and provide optimal support to their children. Interventions such as these can increase parents’ self-awareness of the influence they have on their children and lead to positive student outcomes.

Finally, school counselors should explore strategies that foster social-emotional development for all students and especially those with little parental support. Establishing support systems among students can increase their academic success (Sedlacek, 2017). Mentoring programs that resemble or simulate the parent–child relationship and model rational thinking may yield academic success, given the findings of this study. School counselors also can develop programming that aligns with non-cognitive factors as promoted by Warren and Hale (2016). Students who have a positive self-concept, realistically appraise themselves, are involved in the community, take on leadership roles, have experience in a specific field, and have a support network are better positioned to succeed in school and in life (Sedlacek, 2017). These efforts may position students for school success by neutralizing or reducing the negative impact a lack of parental involvement has on achievement.

Conclusion

School counselors play a critical role in today’s schools. Serving as leaders, advocates, collaborators, and consultants with an aim of promoting student success, school counselors work with many stakeholders, including teachers, administrators, and students and their parents. This study sheds light on the impact of suspension, homework completion, and parental involvement on student achievement. The relationships between parent beliefs and authoritativeness and student achievement also are explored. The authors hope the findings of this study foster awareness and lead school counselors to further consider the impact parents have on student achievement. An understanding of parenting style and beliefs and their impact on student achievement affords school counselors the opportunity to develop targeted programs that increase parent involvement, strengthen the school–parent partnership, and promote academic success.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2012). ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs

(3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37, 887–907. doi:10.2307/1126611

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4, 1–103.

doi:10.1037/h0030372

Baumrind, D. (1991). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In P. A. Cowan & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Advances in Family Research Series. Family Transitions (pp. 111–163). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bernard, M. E. (1990). Rational-emotive therapy with children and adolescents: Treatment strategies. School Psychology Review, 19, 294–303.

Berry, J. O., & Jones, W. H. (1995). The parental stress scale: Initial psychometric evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 463–472. doi:10.1177/0265407595123009

Bryan, J., & Henry, L. (2012). A model for building school–family–community partnerships: Principles and process. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 408–420. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00052.x

Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57, 110–119.

doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13

Carlo, G., White, R. M., Streit, C., Knight, G. P., & Zeiders, K. H. (2018). Longitudinal relations among

parenting styles, prosocial behaviors, and academic outcomes in U.S. Mexican adolescents. Child

Development, 89, 577–592. doi:10.1111/cdev.12761

Castagno, A. E., & Brayboy, B. M. J. (2008). Culturally responsive schooling for Indigenous youth: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78, 941–993. doi:10.3102/0034654308323036

Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

Dryden, W. (2014). Rational emotive behaviour therapy: Distinctive features. London, UK: Routledge.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy: A new and comprehensive method of treating human disturbance.

Secaucus, NJ: Citadel.

Ellis, A., Wolfe, J. L., & Moseley, S. (1981). How to raise an emotionally healthy, happy child. Carlsbad, CA: Borden.

Epstein, J. L. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. New York, NY: Routledge.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Bucher, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146

Gavita, O. A., David, D., DiGiuseppe, R., & DelVecchio, T. (2011). The development and validation of the Parent Rational and Irrational Beliefs Scale. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2305–2311. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.449

Gerard, A. B. (1994). Parent-child relationship inventory. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Gonzalez, J. E., Nelson, J. R., Gutkin, T. B., Saunders, A., Galloway, A., & Shwery, C. S. (2004). Rational emotive therapy with children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 12, 222–235. doi:10.1177/10634266040120040301

Griffin, D., & Farris, A. (2010). School counselors and collaboration: Finding resources through community asset mapping. Professional School Counseling, 13, 248–256. doi:10.1177/2156759X1001300501

Hamamci, Z., & Bağci, C. (2017). Analyzing the relationship between parent’s irrational beliefs and their children’s behavioral problems and family function. Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences, 16, 733–740. doi:10.21547/jss.292722

Hatch, T. (2014). The use of data in school counseling: Hatching results for students, programs, and the profession. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Hojjat, S. K., Golmakanie, E., Khalili, M. N., Smaili, H., Hamidi, M., & Akaberi, A. (2016). Personality traits and irrational beliefs in parents of substance-dependent adolescents: A comparative study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 25, 340–347. doi:10.1080/1067828X.2015.1012612

Imose, R., & Barber, L. K. (2015). Using undergraduate grade point average as a selection tool: A synthesis of the literature. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 18, 1–11. doi:10.1037/mgr0000025

Kalenkoski, C. M., & Pabilonia, S. W. (2017). Does high school homework increase academic achievement? Education Economics, 25, 45–59. doi:10.1080/09645292.2016.1178213

Kenney, S. R., Lac, A., Hummer, J. F., Grimaldi, E. M., & LaBrie, J. W. (2015). Pathways of parenting style on adolescents’ college adjustment, academic achievement, and alcohol risk. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 17, 186–203. doi:10.1177/1521025115578232

Kufakunesu, M. (2015). The influence of irrational beliefs on the mathematics achievement of secondary school learners in Zimbabwe. Retrieved from University of South Africa Institutional Repository (http://hdl.handle.net/10500/20072).

LeFevre, A. L., & Shaw, T. V. (2012). Latino parent involvement and school success: Longitudinal effects of formal and informal support. Education and Urban Society, 44, 707–723. doi:10.1177/0013124511406719

Lindner, H., Kirkby, R., Wertheim, E., & Birch, P. (1999). A brief assessment of irrational thinking: The

shortened General Attitude and Belief Scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23, 651–663.

doi:10.1023/A:1018741009293

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In E.

M. Hetherington (Ed.), Mussen Manual of Child Psychology (Vol. 4, 4th ed., pp. 1–102). New York, NY:

Wiley.

Masud, H., Thurasamy, R., & Ahmad, M. S. (2015). Parenting styles and academic achievement of young adolescents: A systematic literature review. Quality & Quantity, 49, 2411–2433.

doi:10.1007/s11135-014-0120-x

McCown, B., Blake, I. K., & Keiser, R. (2012). Content analyses of the beliefs of academic procrastinators.

Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 30, 213–222. doi:10.1007/s10942-012-0148-6

Noltemeyer, A. L., Ward, R. M., & Mcloughlin, C. (2015). Relationship between school suspension and student outcomes: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 44, 224–240. doi:10.17105/spr-14-0008.1

Pinquart, M. (2016). Associations of parenting styles and dimensions with academic achievement in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 475–493. doi:10.1007/s10648-015-9338-y

Pinquart, M., & Kauser, R. (2018). Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24, 75–100. doi:10.1037/cdp0000149

Ray, S. L., Lambie, G., & Curry, J. (2007). Building caring schools: Implications for professional school counselors. Journal of School Counseling, 5(14). Retrieved from http://jsc.montana.edu/articles/v5n14.pdf

Reitman, D., Rhode, P. C., Hupp, S. D. A., & Altobello, C. (2002). Development and validation of the Parental Authority Questionnaire–Revised. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 24(2), 119–127. doi:10.1023/A:1015344909518

Roby, D. E. (2004). Research on school attendance and student achievement: A study of Ohio schools. Educational Research Quarterly, 28, 3–14.

Sapp, M. (1996). Irrational beliefs that can lead to academic failure for African American middle school students who are academically at-risk. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 14, 123–134. doi:10.1007/BF02238186

Sapp, M., Farrell, W., & Durand, H. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral therapy: Applications for African American middle school at-risk students. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 22(2), 169–177.

Schwerdt, G., West, M. R., & Winters, M. A. (2017). The effects of test-based retention on student outcomes over time: Regression discontinuity evidence from Florida. Journal of Public Economics, 152, 154–169. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.06.004

Sedlacek, W. E. (2017). Measuring noncognitive variables: Improving admissions, success and retention for underrepresented students. Herndon, VA: Stylus.

Snyder, T. D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S. A. (2018). Digest of Education Statistics 2016 (NCES 2017-094). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

SOAR Learning Inc. (2018). SOAR® Learning & Soft Skills Curriculum for College & Career Readiness. Retrieved from https://studyskills.com

Spengler, M., Brunner, M., Martin, R., & Lüdtke, O. (2016). The role of personality in predicting (change in) students’ academic success across four years of secondary school. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 32, 95–103. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000330

Terjesen, M. D., & Kurasaki, R. (2009). Rational emotive behavior therapy: Applications for working with parents and teachers. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 26, 3–14. doi:10.1590/S0103-166X2009000100001

Warren, J. M. (2017). School consultation for student success: A cognitive behavioral approach. New York, NY: Springer.

Warren, J. M., & Dowden, A. R. (2012). Elementary school teachers’ beliefs and emotions: Implications for school counselors and counselor educators. Journal of School Counseling, 10(19). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ981200.pdf

Warren, J. M., & Gerler, E. R., Jr. (2013). Effects of school counselors’ cognitive behavioral consultation on irrational and efficacy beliefs of elementary school teachers. The Professional Counselor, 3, 6–15. doi:10.15241/jmw.3.1.6

Warren, J. M., & Hale, R. W. (2016). Fostering non-cognitive development of underrepresented students through rational emotive behavior therapy: Recommendations for school counselor practice. The Professional Counselor, 6, 89–106. doi:10.15241/jw.6.1.89

Warren, J. M., & Hale, R. W. (in press). Predicting grit and resilience: Exploring college students’ academic rational beliefs. Journal of College Counseling.

York, T. T., Gibson, C., & Rankin, S. (2015). Defining and measuring academic success. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 20(5), 1–20.

Jeffrey M. Warren, NCC, is an associate professor and Chair of the Counseling Department at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Leslie A. Locklear is the FATE Director at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Nicholas A. Watson is a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Correspondence can be addressed to Jeffrey Warren, 1 University Drive, Pembroke, NC 28372, jeffrey.warren@uncp.edu.

Nov 10, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 4

Zachary D. Bloom, Victoria A. McNeil, Paulina Flasch, Faith Sanders

Empathy plays an integral role in the facilitation of therapeutic relationships and promotion of positive client outcomes. Researchers and scholars agree that some components of empathy might be dispositional in nature and that empathy can be developed through empathy training. However, although empathy is an essential part of the counseling process, literature reviewing the development of counseling students’ empathy is limited. Thus, we examined empathy and sympathy scores in counselors-in-training (CITs) in comparison to students from other academic disciplines (N = 868) to determine if CITs possess greater levels of empathy than their non-counseling academic peers. We conducted a MANOVA and failed to identify differences in levels of empathy or sympathy across participants regardless of academic discipline, potentially indicating that counselor education programs might be missing opportunities to further develop empathy in their CITs. We call for counselor education training programs to promote empathy development in their CITs.

Keywords: empathy, sympathy, counselor education, counselors-in-training, therapeutic relationships

Empathy is considered an essential component of the human experience as it relates to how individuals socially and emotionally connect to one another (Goleman, 1995; Szalavitz & Perry, 2010). Although empathy can be difficult to define (Konrath, O’Brien, & Hsing, 2011; Spreng, McKinnon, Mar, & Levine, 2009), within the counseling profession there is agreement that empathy includes both cognitive and affective components (Clark, 2004; Davis, 1980, 1983). When discussing the difference between affective and cognitive empathy, Vossen, Piotrowski, and Valkenburg (2015) described that “whereas the affective component pertains to the experience of another person’s emotional state, the cognitive component refers to the comprehension of another person’s emotions” (p. 66). Regardless of specific nuances among researchers’ definitions of empathy, most appear to agree that “empathy-related responding is believed to influence whether or not, as well as whom, individuals help or hurt” (Eisenberg, Eggum, & Di Giunta, 2010, p. 144). Furthermore, empathy can be viewed as a motivating factor of altruistic behavior (Batson & Shaw, 1991) and is essential to clients’ experiences of care (Flasch et al., in press). As such, empathy is foundational to interpersonal relationships (Siegel, 2010; Szalavitz & Perry, 2010), including the relationships facilitated in a counseling setting (Norcross, 2011; Rogers, 1957).

Rogers (1957) intuitively understood the necessity of empathy in a counseling relationship, which has been verified by the understanding of the physiology of the brain (Badenoch, 2008; Decety & Ickes, 2009; Siegel, 2010) and validated in the counseling literature (Elliott, Bohart, Watson, & Greenberg, 2011). In a clinical context, empathy can be described as both a personal characteristic and a clinical skill (Clark, 2010; Elliott et al., 2011; Rogers, 1957) that contributes to positive client outcomes (Norcross, 2011; Watson, Steckley, & McMullen, 2014). For example, empathy has been identified as a factor that leads to changes in clients’ attachment styles, treatment of self (Watson et al., 2014), and self-esteem development (McWhirter, Besett-Alesch, Horibata, & Gat, 2002). Moreover, researchers regularly identify empathy as a fundamental component of helpful responses to clients’ experiences (Beder, 2004; Flasch et al., in press; Kirchberg, Neimeyer, & James, 1998).

Although empathy is lauded and encouraged in the counseling profession, empathy development is not necessarily an explicit focus or even a mandated component of clinical training programs. The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2016) identifies diverse training standards for content knowledge and practice among master’s-level and doctoral-level counselors-in-training (CITs), but does not mention the word empathy in its manual for counseling programs. One of the reasons for this could be that empathy is often understood and taught as a microskill (e.g., reflection of feeling and meaning) rather than as its own construct (Bayne & Jangha, 2016). Yet empathy is more than a component of a skillset, and CITs might benefit from a programmatic development of empathy to enhance their work with future clients (DePue & Lambie, 2014).

The application of empathy, or a counselor’s use of empathy-based responses in a therapeutic relationship, requires skill and practice (Barrett-Lennard, 1986; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). Clark (2010) cautioned, for example, that counselors’ empathic responses need to be congruent with the client’s experience, and that the misapplication of sympathetic responses as empathic responses can interfere in the counseling relationship. In regard to sympathy, Eisenberg and colleagues (2010) explained, “sympathy, like empathy, involves an understanding of another’s emotion and includes an emotional response, but it consists of feelings of sorrow or concern for the distressed or needy other rather than merely feeling the same emotion” (p. 145). Thus, researchers call for counselor educators to do more than increase CITs’ affective or cognitive understanding of another’s experience, and to assist them in differentiating between empathic responses and sympathetic responses in order to better convey empathic understanding and relating (Bloom & Lambie, in press; Clark, 2010).

With the understanding that a counselor’s misuse of sympathetic responses might interrupt a therapeutic dialogue and that empathy is vital to the therapeutic alliance, researchers call for counselor educators to promote empathy development in CITs (Bloom & Lambie, in press; DePue & Lambie, 2014). Although there is evidence that some aspects of empathy are dispositional in nature (Badenoch, 2008; Konrath et al., 2011), which might make the counseling profession a strong fit for empathic individuals, empathy training in counseling programs can increase students’ levels of empathy (Ivey, 1971). However, the specific empathy-promoting components of empathy training are less understood (Teding van Berkhout & Malouff, 2016). Overall, empathy is an essential component of the counseling relationship, counselor competency, and the promotion of client outcomes (DePue & Lambie, 2014; Norcross, 2011). However, little is known about the training aspect of empathy and whether or not counselor training programs are effective in enhancing empathy or reducing sympathy among CITs. Thus, the following question guided this research investigation: Are CITs’ levels of empathy or sympathy different from their academic peers? Specifically, do CITs possess greater levels of empathy or sympathy than students from other academic majors?

Empathy in Counseling

Researchers have established continuous support for the importance of the therapeutic relationship in the facilitation of positive client outcomes (Lambert & Bergin, 1994; Norcross, 2011; Norcross & Lambert, 2011). In fact, the therapeutic relationship is predictive of positive client outcomes (Connors, Carroll, DiClemente, Longabaugh, & Donovan, 1997; Krupnick et al., 1996), accounting for about 30% of the variance (Lambert & Barley, 2001). That is, clients who perceive the counseling relationship to be meaningful will have more positive treatment outcomes (Bell, Hagedorn, & Robinson, 2016; Norcross & Lambert, 2011). One of the key factors in the establishment of a strong therapeutic relationship is a counselor’s ability to experience and communicate empathy. Researchers estimate that empathy alone may account for as much as 7–10% of overall treatment outcomes (Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, & Watson, 2002; Sachse & Elliott, 2002), making it an important construct to foster in counselors.

Despite the importance of empathy in the counseling process, much of the literature on empathy training in counseling is outdated. Thus, little is known about the training aspect of empathy; that is, how is empathy taught to and learned by counselors? Nevertheless, early scholars (Barrett-Lennard, 1986; Ivey, 1971; Ivey, Normington, Miller, Morrill, & Haase, 1968; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967) posited that counselor empathy is a clinical skill that may be practiced and learned, and there is supporting evidence that empathy training may be efficacious.

In one seminal study, Truax and Lister (1971) conducted a 40-hour empathy training program with 12 counselor participants and identified statistically significant increases in participants’ levels of empathy. In their investigation, the researchers employed methods in which (a) the facilitator modeled empathy, warmth, and genuineness throughout the training program; (b) therapeutic groups were used to integrate empathy skills with personal values; and (c) researchers coded three of participants’ 4-minute counseling clips using scales of accurate empathy and non-possessive warmth (Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). Despite identifying statistically significant changes in participants’ scores of empathy, it is necessary to note that participants who initially demonstrated low levels of empathy remained lower than participants who initially scored high on the empathy measures. In a later study modeled after the Truax and Lister study, Silva (2001) utilized a combination of didactic, experiential, and practice components in her empathy training program, and found that counselor trainee participants (N = 45) improved their overall empathy scores on Truax’s Accurate Empathy Scale (Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). These findings contribute to the idea that empathy increases as a result of empathy training.

More recent researchers (Lam, Kolomitro, & Alamparambil, 2011; Ridley, Kelly, & Mollen, 2011) have identified the most common methods in empathy training programs as experiential training, didactic (lecture), skills training, and other mixed methods such as role play and reflection. In their meta-analysis, Teding van Berkhout and Malouff (2016) examined the effect of empathy training programs across various populations (e.g., university students, health professionals, patients, other adults, teens, and children) using the training methods identified above. The researchers investigated the effect of cognitive, affective, and behavioral empathy training and found a statistically significant medium effect size overall (g ranged from 0.51 to 0.73). The effect size was larger in health professionals and university students compared to other groups such as teenagers and adult community members. Though empathy increased as a result of empathy training studies, the specific mechanisms that facilitated positive outcomes remain largely unknown.

Although research indicates that empathy training can be effective, specific empathy-fostering skills are still not fully understood. Programmatically, empathy is taught to counselors within basic counseling skills (Bayne & Jangha, 2016), specifically because empathy is believed to lie in the accurate reflection of feeling and meaning (Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). But scholars argue that there is more to empathy than the verbal communication of understanding (Davis, 1980; Vossen et al., 2015). For example, in a more recent study, DePue and Lambie (2014) reported that counselor trainees’ scores on the Empathic Concern subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1980) increased as a result of engaging in counseling practicum experience under live supervision in a university-based clinical counseling and research center. In their study, the researchers did not actively engage in empathy training. Rather, they measured counseling students’ pre- and post-scores on an empathy measure as a result of students’ engagement in supervised counseling work to foster general counseling skills. Implications of these findings mirror those described by Teding van Berkhout and Malouff (2016), namely that it is difficult to identify specific empathy-promoting mechanisms. In other words, it appears that empathy training, when employed, produces successful outcomes in CITs. However, counseling students’ empathy also increases in the absence of specific empathy-promoting programs. This begs the question: Are counseling programs successfully training their counselors to be empathic, and is there a difference between CITs’ empathy or sympathy levels compared to students in other academic majors? Thus, the purpose of the present study was to (a) examine differences in empathy (i.e., affective empathy and cognitive empathy) and sympathy levels among emerging adult college students, and (b) determine whether CITs had different levels of empathy and sympathy when compared to their academic peers.

Methods

Participants

We identified master’s-level CITs as the population of interest in this investigation. We intended to compare CITs to other graduate and undergraduate college student populations. Thus, we utilized a convenience sample from a larger data set that included emerging adult college students between the ages of 18 and 29 who were enrolled in at least one undergraduate- or graduate-level course at nine colleges and universities throughout the United States. Participants were included regardless of demographic variables (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity).

Participants were recruited from three sources: online survey distribution (n = 448; 51.6%), face-to-face data collection (n = 361; 41.6%), and email solicitation (n = 34; 3.9%). In total, 10,157 potential participants had access to participate in the investigation by online survey distribution through the psychology department at a large Southeastern university; however, the automated system limited responses to 999 participants. We and our contacts (i.e., faculty at other institutions) distributed an additional 800 physical data collection packets to potential participants, and 105 additional potential participants were solicited by email. Overall, 1,713 data packets were completed, resulting in a sample of 1,598 participants after data cleaning. However, in order to conduct the analyses for this study, it was necessary to limit our sample to groups of approximately equal sizes (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). Therefore, we were limited to the use of a subsample of 868 participants. Our sample appeared similar to other samples included in investigations exploring empathy with emerging adult college students (e.g., White, heterosexual, female; Konrath et al., 2011).

The participants included in this investigation were enrolled in one of six majors and programs of study, including Athletic Training/Health Sciences (n = 115; 13.2%); Biology/Biomedical Sciences/Preclinical Health Sciences (n = 167; 19.2%); Communication (n = 163; 18.8%); Counseling (n = 153; 17.6%); Nursing (n = 128; 14.7%); and Psychology (n = 142; 16.4%). It is necessary to note that students self-identified their major rather than selecting it from a preexisting prompt. Therefore, the researchers examined responses and categorized similar responses to one uniform title. For example, responses of psych were included with psychology. Further, in order to attain homogeneity among group sizes, we included multiple tracks within one program. For example, counseling included participants enrolled in either clinical mental health counseling (n = 115), marriage and family counseling (n = 24), or school counseling (n = 14) tracks. Table 1 presents additional demographic information (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, graduate-level status). It is necessary to note that, because of the constraints of the dataset, counseling students consisted of master’s-level graduate students, whereas all other groups consisted of undergraduate students.

Table 1

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic |

|

n

|

Total %

|

|

| Age |

18–19 |

460

|

52.4

|

|

|

20–21 |

155

|

17.9

|

|

|

22–23 |

130

|

15.0

|

|

|

24–25 |

58

|

6.7

|

|

|

26–27 |

36

|

4.1

|

|

|

28–29 |

27

|

3.1

|

|

| Gender |

Female |

692

|

79.7

|

|

|

Male |

167

|

19.2

|

|

|

Other |

8

|

0.9

|

|

| Racial |

Caucasian |

624

|

71.9

|

|

| Background |

African American/African/Black |

101

|

11.6

|

|

|

Biracial/Multiracial |

65

|

7.5

|

|

|

Asian/Asian American |

40

|

4.6

|

|

|

Native American |

3

|

0.3

|

|

|

Other |

25

|

2.9

|

|

| Ethnicity |

Hispanic |

172

|

19.8

|

|

|

Non-Hispanic |

689

|

79.4

|

|

| Academic |

Undergraduate |

709

|

81.7

|

|

| Enrollment |

Graduate |

152

|

17.5

|

|

|

Other |

5

|

0.6

|

|

| Academic Major |

Athletic Training/Health Sciences |

115

|

13.2

|

|

|

Biology/Biomedical Sciences/Preclinical Health Sciences |

167

|

19.2

|

|

|

Counseling |

153

|

17.6

|

|

|

Communication |

163

|

18.8

|

|

|

Nursing |

128

|

14.7

|

|

|

Psychology |

142

|

16.4

|

|

Note. N

= 868.

Procedure

The data utilized in this study were collected as part of a larger study that was approved by the authors’ institutional review board (IRB) as well as additional university IRBs where data was collected, as requested. We followed the Tailored Design Method (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2009), a series of recommendations for conducting survey research to increase participant motivation and decrease attrition, throughout the data collection process for both web-based survey and face-to-face administration. Participants received informed consent, assuring potential participants that their responses would be confidential and their anonymity would be protected. We also made the survey convenient and accessible to potential participants by making it available either in person or online, and by avoiding the use of technical language (Dillman et al., 2009).

We received approval from the authors of the Adolescent Measure of Empathy and Sympathy (AMES; Vossen et al., 2015; personal communication with H. G. M. Vossen, July 10, 2015) to use the instrument and converted the data collection packet (e.g., demographic questionnaire, AMES) into Qualtrics (2013) for survey distribution. We solicited feedback from 10 colleagues regarding the legibility and parsimony of the physical data collection packets and the accuracy of the survey links. We implemented all recommendations and changes (e.g., clarifying directions on the demographic questionnaire) prior to data collection.

All completed data collection packets were assigned a unique ID, and we entered the data into the IBM SPSS software package for Windows, Version 22. No identifying information was collected (e.g., participants’ names). Having collected data both in person and online via web-based survey, we applied rigorous data collection procedures to increase response rates, reduce attrition, and to mitigate the potential influence of external confounding factors that might contribute to measurement error.

Data Instrumentation

Demographics profile. We included a general demographic questionnaire to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the participants in our study. We included items related to various demographic variables (e.g., age, race, ethnicity). Regarding participants’ identified academic program, participants were prompted to respond to an open-ended question asking “What is your major area of study?”

AMES. Multiple assessments exist to measure empathy (e.g., the IRI, Davis, 1980, 1983; The Basic Empathy Scale [BES], Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006), but each is limited by several shortcomings (Carré, Stefaniak, D’Ambrosio, Bensalah, & Besche-Richard, 2013). First, many scales measure empathy as a single construct without distinguishing cognitive empathy from affective empathy (Vossen et al., 2015). Moreover, the wording used in most scales is ambiguous, such as items from other assessments that use words like “swept up” or “touched by” (Vossen et al., 2015), and few scales differentiate empathy from sympathy. Therefore, Vossen and colleagues designed the AMES as an empathy assessment that addresses problems related to ambiguous wording and differentiates empathy from sympathy.

The AMES is a 12-item empathy assessment with three factors: (a) Cognitive Empathy, (b) Affective Empathy, and (c) Sympathy. Each factor consists of four items rated on a 5-point Likert scale with ratings of 1 (never), 2 (almost never), 3 (sometimes), 4 (often), and 5 (always). Higher AMES scores indicate greater levels of cognitive empathy (e.g., “I can tell when someone acts happy, when they actually are not”), affective empathy (e.g., “When my friend is sad, I become sad too”), and sympathy (e.g., “I feel concerned for other people who are sick”). The AMES was developed in two studies with Dutch adolescents (Vossen et al., 2015). The researchers identified a 3-factor model with acceptable to good internal consistency per factor: (a) Cognitive Empathy (α = 0.86), (b) Affective Empathy (α = 0.75), and (c) Sympathy (α = 0.76). Further, Vossen et al. (2015) established evidence of strong test-retest reliability, construct validity, and discriminant validity when using the AMES to measure scores of empathy and sympathy with their samples. Despite being normed with samples of Dutch adolescents, Vossen and colleagues suggested the AMES might be an effective measure of empathy and sympathy with alternate samples as well.

Bloom and Lambie (in press) examined the factor structure and internal consistency of the AMES with a sample of emerging adult college students in the United States (N = 1,598) and identified a 3-factor model fitted to nine items that demonstrated strong psychometric properties and accounted for over 60% of the variance explained (Hair et al., 2010). The modified 3-factor model included the same three factors as the original AMES. Therefore, we followed Bloom and Lambie’s modifications for our use of the instrument.

Data Screening

Before running the main analysis on the variables of interest, we assessed the data for meeting the assumptions necessary to conduct a one-way between-subjects MANOVA. First, we conducted a series of tests to evaluate the presence of patterns in missing data and determined that data were missing completely at random (MCAR) and ignorable (e.g., < 5%; Kline, 2011). Because of the robust size of these data (e.g., > 20 observations per cell) and the minimal amount of missing data, we determined listwise deletion to be best practice to conduct a MANOVA and to maintain fidelity to the data (Hair et al., 2010; Osborne, 2013).

Next, we utilized histograms, Q-Q plots, and boxplots to assess for normality and identified non-normal data patterns. However, MANOVA is considered “robust” to violations of normality with a sample size of at least 20 in each cell (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Thus, with our smallest cell size possessing a sample size of 115, we considered our data robust to this violation. Following this, we assumed our data violated the assumption for multivariate normality. However, Hair et al. (2010) stated “violations of this assumption have little impact with larger sample sizes” (p. 366) and cautioned that our data might have problems achieving a non-significant score for Box’s M Test. Indeed, our data violated the assumption of homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices (p < .01). However, this was not a concern with these data because “a violation of this assumption has minimal impact if the groups are of approximately equal size (i.e., largest group size ÷ smallest group size < 1.5)” (Hair et al., 2010, p. 365).

It is necessary to note that MANOVA is sensitive to outlier values. To mitigate against the negative effects of extreme scores, we removed values (n = 3) with standardized z-scores greater than +4 or less than -4 (Hair et al., 2010). This resulted in a final sample size of 868 participants.

We also utilized scatterplots to detect the patterns of non-linear relationships between the dependent variables and failed to identify evidence of non-linearity. Therefore, we proceeded with the assumption that our data shared linear relationships. We also evaluated the data for multicollinearity. Participants’ scores of Affective Empathy shared statistically significant and appropriate relationships with their scores of Cognitive Empathy (r = .24) and Sympathy (r = .43). Similarly, participants’ scores of Cognitive Empathy were appropriately related to their scores of Sympathy (r = .36; p < .01). Overall, we determined these data to be appropriate to conduct a MANOVA. Table 2 presents participants’ scores by academic discipline.

Table 2

AMES Scores by Academic Major

|

Scale

|

Mean (M)

|

SD

|

Range

|

| Athletic Training |

|

|

|

|

Affective Empathy

|

3.20

|

0.80

|

4.00 |

|

Cognitive Empathy

|

3.80

|

0.62

|

3.33 |

|

Sympathy

|

4.34

|

0.55

|

2.67 |

| Biomedical Sciences |

|

|

|

|

Affective Empathy

|

3.12

|

0.76

|

4.00 |

|

Cognitive Empathy

|

3.66

|

0.59

|

3.00 |

|

Sympathy

|

4.30

|

0.61

|

2.00 |

| Communication |

|

|

|

|

Affective Empathy

|

3.18

|

0.87

|

4.00 |

|

Cognitive Empathy

|

3.80

|

0.62

|

2.67 |

|

Sympathy

|

4.27

|

0.69

|

3.00 |

| Counseling |

|

|

|

|

Affective Empathy

|

3.32

|

0.60

|

3.33 |

|

Cognitive Empathy

|

3.83

|

0.48

|

4.00 |

|

Sympathy

|

4.32

|

0.54

|

2.00 |

| Nursing |

|

|

|

|

Affective Empathy

|

3.37

|

0.71

|

3.67 |

|

Cognitive Empathy

|

3.80

|

0.59

|

2.67 |

|

Sympathy

|

4.46

|

0.49

|

2.00 |

| Psychology |

|

|

|

|

Affective Empathy

|

3.28

|

0.78

|

4.00 |

|

Cognitive Empathy

|

3.86

|

0.59

|

2.67 |

|

Sympathy

|

4.35

|

0.65

|

2.67 |

Note. N

= 868.

Results

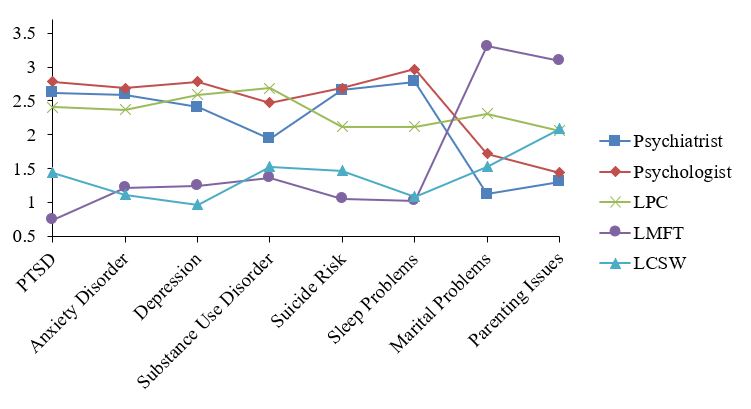

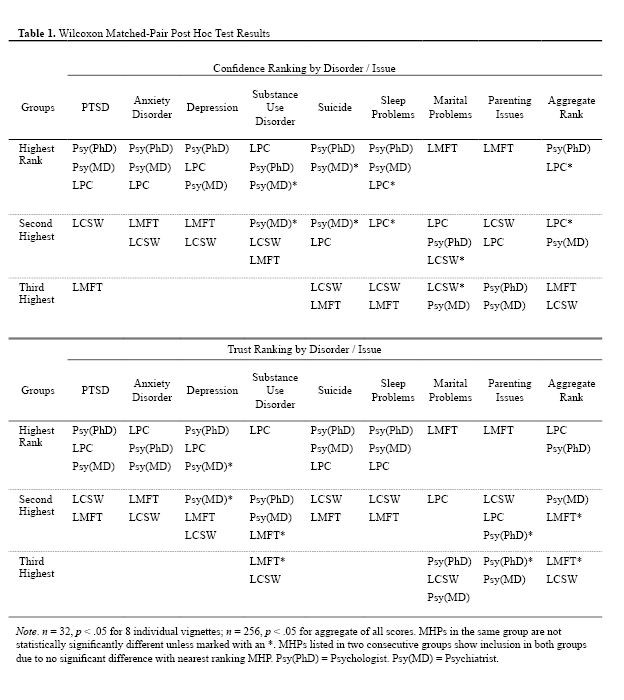

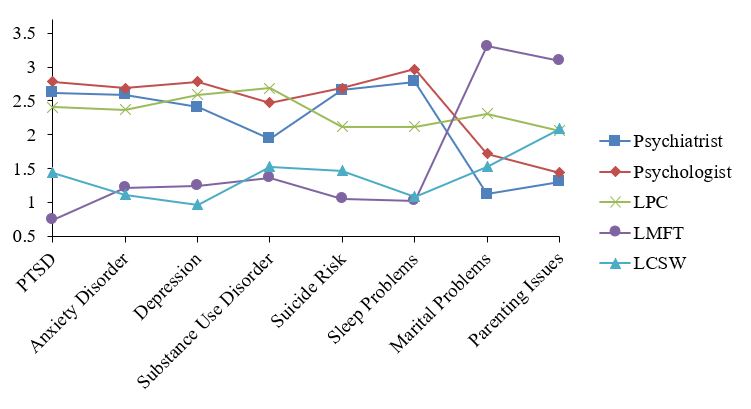

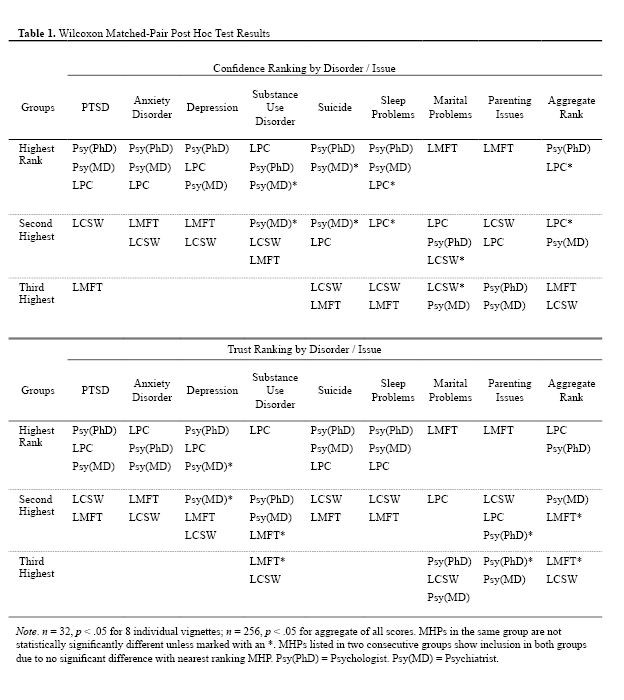

Participants’ scores on the AMES were used to measure participants’ levels of empathy and sympathy. Descriptive statistics were used to compare empathy and sympathy levels between counseling students and emerging college students from other disciplines. CITs recorded the second highest levels of affective empathy (M = 3.32, SD = .60) and cognitive empathy (M = 3.83, SD = 0.48), and the fourth highest levels of sympathy (M = 4.32, SD = 0.54) when compared to students from other disciplines. Nursing students demonstrated the highest levels of affective empathy (M = 3.37, SD = .71) and sympathy (M = 4.46, SD = .49), and psychology students recorded the highest levels of cognitive empathy (M = 3.86, SD = 0.59) when compared to students from other disciplines. The internal consistency values for each empathy and sympathy subscale on the AMES were as follows: Cognitive Empathy (α = 0.86), Affective Empathy (α = 0.75), and Sympathy (α = 0.76).

We performed a MANOVA to examine differences in empathy and sympathy in emerging adult college students by academic major, including counseling. Three dependent variables were included: affective empathy, cognitive empathy, and sympathy. The predictor for the MANOVA was the 6-level categorical “academic major” variable. The criterion variables for the MANOVA were the levels of affective empathy (M = 3.24, SD = .76), cognitive empathy (M = 3.80, SD = .58), and sympathy

(M = 4.34, SD = .60), respectively. The multivariate effect of major was statistically non-significant:

p = .062, Wilks’s lambda = .972, F (15, 2374.483) = 1.615, η2 = .009. Furthermore, the univariate F scores for affective empathy (p = .139), cognitive empathy (p = .074), and sympathy (p = .113) were statistically non-significant. That is, there was no difference in levels of affective empathy, cognitive empathy, or sympathy based on academic major, including counseling. Thus, these data indicated that CITs were no more empathic or sympathetic than students in other majors, as measured by the AMES.

We also examined these data for differences in affective empathy, cognitive empathy, and sympathy based on data collection method and educational level. However, we failed to identify a statistically significant difference between groups in empathy or sympathy based on data collection method

(e.g., online survey distribution, face-to-face data collection, email solicitation) or by educational level (e.g., master’s level or undergraduate status). Thus, these data indicate that data collection methods and participants’ educational level did not influence our results.

Discussion