Feb 7, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 1

Emily Sallee, Abraham Cazares-Cervantes, Kok-Mun Ng

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescents (ages 12–19) in the United States, and more work is needed to shed light on the interpersonal protective factors associated with adolescent suicidality. To address this gap in the empirical literature, we examined the application of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS) to the middle adolescent population. We analyzed survey data using the 2017 Oregon Healthy Teen dataset, which included 10,703 students in 11th grade. Binary logistic regressions were used to examine the extent to which the IPTS constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predicted middle adolescent suicide ideation and attempt. Findings indicate that three of the five proxy items were statistically significant in each model, with consistent mediators for each. These findings have the potential to guide development of appropriate treatment strategies based on the interpersonal constructs of the IPTS for clinicians working with this population.

Keywords: adolescents, suicide ideation, suicide attempt, suicidality, Interpersonal Theory of Suicide

Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide, spanning across all ages, ethnicities, genders, cultures, and religions. In the United States from 2000 to 2015, suicide rates increased 28%, with 44,193 people dying by suicide yearly, equating to about one death every 12 minutes. Nationally, statistics now identify suicide as the second leading cause of death in adolescent populations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2017). Specific to the state of Oregon, over 500 youth between the ages of 10–24 were hospitalized each year because of self-harm, including suicide attempts. In 2017 alone, more than 750 youth were hospitalized and 107 suicides were completed; considering that many ideations and attempts do not result in hospitalization, it is likely that there were more Oregonian youth who had attempted suicide but were never hospitalized, and an even greater number who had contemplated suicide (Oregon Suicide Prevention, n.d.).

Unfortunately, studies on suicide, particularly adolescent suicide, are rarely driven by theory. This results in a lack of integration between research findings and clinical practice (King et al., 2018). Clinicians working with the adolescent population are in need of research- and evidence-based practices ready for implementation. Although the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS; Joiner et al., 2009) was initially developed for and then applied to adult populations, it has the potential to inform clinicians in preventative and intervention efforts in other populations, offering an evidence-based framework to understand and address suicide prevention and intervention. In an earlier study (Sallee et al., 2021), we found evidence to support its use with the early adolescent (ages 11–14) population. The present study utilizes the IPTS as a framework to examine the interpersonal drivers of suicidality among middle adolescents (ages 14–17) in Oregon.

Joiner et al.’s (2009) IPTS offers a theoretical lens to explain suicide ideation and behavior in three dynamic constructs: perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability. The first two are influential in suicidal desire. The dynamicity of the constructs is related to the fluctuation of interpersonal needs and cognitions over time. Together they contribute to significant risk for suicide ideation. Acquired capability is static and believed to develop in response to exposure to provocative, painful, and/or violent experiences, overpowering the human survival need of self-preservation. Acquired capability, in tandem with thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, results in a high risk for suicidal behavior/attempt (King et al., 2018).

This field of research uses terms like suicide ideation, suicidal behavior, suicidology, self-harm, self-injury, and self-inflicted death to describe the thoughts and behaviors of a person ending their own life. The CDC defines suicide ideation within a broader class of behavior called self-directed violence, referring to “behaviors directed at oneself that deliberately results in injury or the potential for injury . . . [it] may be suicidal or non-suicidal in nature” (Stone et al., 2017, p. 7). The intent of suicidal self-directed violence is death, while the intent of non-suicidal self-directed violence is not. A suicide attempt may or may not result in death or other injuries. Because we held a particular interest in adolescent suicide ideation and behavior, its differentiation of lethal intent from non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) led us to leave NSSI ideation and/or behavior out of the scope of the study. However, recent studies addressing IPTS have included self-harm as an indicator of acquired capability (e.g., Barzilay et al., 2019) and should be included in future studies involving this construct.

Suicide ideation and attempt in adolescent populations is a serious public health concern in the United States that is growing in frequency and intensity every year. National statistics suggest that 17.2% of adolescents have experienced or currently experience suicide ideation, and 7.4% of adolescents have made a suicide attempt (CDC, 2017). Despite this growing health concern, most research in this body of work has focused primarily on adult populations (Horton et al., 2016; Stone et al., 2017). Limitations in the extant empirical literature include a lack of emphasis on theory as well as a lack of quantitative research on large samples in non-inpatient treatment settings (Czyz et al., 2015; Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014). In clinical practice, this challenges mental health practitioners’ ability to rely on evidence to serve their clients. Becker et al. (2020) found significant evidence of the applicability of IPTS to a large undergraduate (ages 18–29) population, suggesting that the interpersonal constructs might be applicable to younger non-inpatient groups. Based on the IPTS, this study examined the extent to which a specific set of interpersonal predictors of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belonging were associated with suicide ideation and attempt in a large non-clinical sample of middle adolescents.

Adolescents and Suicidality

Adolescence marks the developmental period between childhood and adulthood, corresponding to the time from pubertal onset to guardian independence. This period is associated with increased risk-taking behaviors as well as increased emotional reactivity, occurring in the context of developmental changes influenced by external and internal factors that elicit and reinforce behaviors. Cognitively, over the course of adolescence, the prefrontal cortex of the brain continues to develop and is responsible for impulse control and delayed gratification in favor of more goal-directed choices and behaviors (Jaworska & MacQueen, 2015). One apparent risk factor for suicide ideation and behavior in adolescents is their impaired decision-making. In addition, this developmental period also accounts for half of all emotional and behavioral disorder diagnoses and the highest rates of suicide with subsequent higher risks for suicidal behavior during their lifetime (Wyman, 2014). Wasserman et al. (2015) metabolized research supporting the theory that most pathological changes occur in childhood and adolescence, suggesting that it is during this developmental time period that prevention and intervention is imperative, as the adolescent years themselves prove to be a risk factor for suicide ideation and behavior.

The typical age of 11th grade students is 16 or 17, and these students are characterized as being in the developmental period known as “middle adolescence.” By this age, puberty is typically completed for both males and females, and adolescents begin setting long-term goals, concurrently becoming more interested in the meaning of life and moral reasoning. They experience an increased drive for independence and increased self-involvement. During the overall developmental stage of adolescence, youth must adjust to their physically and sexually maturing bodies and feelings; define their personal sense of identity and adopt a personal value system; renegotiate their relationships with parents, family, and caregivers; and develop stable and productive peer relationships (Teipel, 2013).

Of relevance to the present study, it is important to note that according to Teipel (2013), adolescents in 11th grade (ages 16–17) experience an increased concern with their appearances and bodies, incorporating a personal sense of masculinity or femininity into their identities and establishing values and preferences of sexual behavior. This period of self-involvement results in high expectations of self and low self-concept, coinciding with an increased drive for peer acceptance and reliance (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2021). Additionally, as the typical adolescent is tasked with gaining autonomy and independence from the nuclear family, they will likely experience periods of sadness as the psychological loss, not so unlike grief, takes place (Teipel, 2013). Adolescents in the 11th grade school environment are preparing for the final year of high school and potentially postsecondary education after graduation, creating unique stressors related to increasing autonomy and independence as they approach the formidable ascent into adulthood.

The IPTS

Theories of suicide have evolved over the past 70 years to reflect research and societal influences and implications, yet they all seem to agree that “perceived disruption of interpersonal relationships may serve as one potential mechanism of the association between child maltreatment and [suicide ideation]” (Miller et al., 2014, p. 999). Durkheim and Simpson (1951) suggested that suicide was the result of social causes like isolation, altruism, and anger/frustration. Behavioral theorists like Lester (1987) believed that suicide was a learned behavior, resulting from adverse childhood experiences and psychosocial environmental factors. Schneidman (1993) thought suicidal behaviors were motivated by the desire to escape emotional pain caused by the lack of socially supportive and nurturing relationships. Joiner’s IPTS focuses on the importance of interpersonal relationships, characterized by the confluence of two negative interpersonal states (i.e., perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness; Miller et al., 2014).

The present study was guided by several gaps in the literature related to the application of the IPTS to adolescent populations. Initially, the IPTS was constructed by Joiner and his colleagues (2009) through studying adults engaging in suicidal behaviors. Since its development, the theory has been studied primarily in its application to adult and college student populations (Horton et al., 2016). The lack of research on the application of the IPTS to non-inpatient adolescents may suggest its incompatibility to the uniqueness of adolescent suicidality; however, Horton et al. (2016) argued that the constructs of the theory are relevant in adolescence regardless of setting and presentation, though they may manifest in slightly different ways based on differences in developmental context. As such, they proposed that perceived burdensomeness in adolescents may manifest as low academic competency or social disconnection and thwarted belongingness may manifest as social isolation from peers or poor family cohesion. Adolescence is also a developmental period when children may begin to engage in health-risk behaviors, are particularly prone to impulsivity because of the immature nature of their prefrontal cortex, and have the increased pressure of peer behavior on their own, as well as a sense of invulnerability to consequences (Horton et al., 2016). Though adolescent suicide–related research based on the IPTS to date remains sparse, the theory’s focus on the dynamic constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness appears attractive in consideration of potential application to preventative and responsive efforts.

Perceived Burdensomeness

Perceived burdensomeness is characterized by self-hatred and the belief that one is a burden to others, including family and friends, leading to the idea that they would be better off without them. It deals with the misperceptions of being a liability for family and intimate peers. As a dynamic interpersonal construct, it responds well to both interpersonal and intrapersonal interventions. However, although perceived burdensomeness responds more slowly to intervention, it may be a more significant predictor of suicide ideation and behavior than thwarted belongingness. There is also research that suggests that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are more enmeshed in adolescents, suggesting that only one of the dynamic interpersonal constructs is necessary to be coupled with acquired capability and lead to suicidal behavior (Chu et al., 2016; Joiner et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2017).

Thwarted Belongingness

Thwarted belongingness is a dynamic condition of social disconnection described by the interpersonal state of loneliness in which the psychological need to belong is not met. Of the two dynamic interpersonal constructs within the IPTS that respond to both interpersonal and intrapersonal interventions (thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness), research suggests that thwarted belongingness may be easier to treat and respond more quickly to intervention than perceived burdensomeness (Chu et al., 2016; Joiner et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2017). It has been well established that positive and negative effects of close relationships are particularly formative in the adolescent years, and therein lies the difficult developmental task of establishing strong peer relationships while also maintaining familial bonds (Miller et al., 2014). Relatedly, adolescents with histories of abuse or other maltreatment are at particular risk. It has been shown that low perceived quality of family and peer connectedness and belonging contribute to thwarted belongingness and its dynamic interpersonal state.

Acquired Capability

Acquired capability is a static construct in the IPTS, describing a decrease in or lack of fear about death and an elevated tolerance of physical pain. It is suggested to be developed through repeated exposure to painful and provocative events (Chu et al., 2016; Joiner et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2017). Stewart et al. (2017) characterized it as “the combination of increased pain tolerance and decreased fear of death [that] results in progression from suicide intent to suicidal behavior, culminating in a suicide attempt” (p. 438). This construct’s combination of pain tolerance and fearlessness about death is significant in current conversations around adolescents engaging in violent video games, which could correlate to fearlessness about death but not necessarily pain tolerance (Stewart et al., 2017). Acquired capability as the combination of pain tolerance and fearlessness is also significant to other mental health disorders, including anorexia nervosa, in which risk factors for suicide ideation and behavior are prevalent and are characterized by increased pain tolerance and fearlessness about death.

According to the IPTS, these three constructs are proximal to suicidal behavior. Horton et al. (2016) suggested that “an important strength of the theory is that it explains the lower frequency of more severe levels of suicidality (such as suicide attempt) compared to less severe levels (such as passive suicide ideation)” (p. 1134) because it is the combination of the three constructs that leads to suicidal behavior. The theory also posits that the difference between passive and active suicide ideation is the difference between the presence of one or both of the dynamic interpersonal states of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. In other words, one dynamic interpersonal construct suggests passive ideation, two suggest active ideation, and all three constructs lead to suicidal behavior.

Purpose of the Present Study

Most previous studies that applied the IPTS to suicidal adolescents of this specific age group only addressed inpatient populations (e.g., Czyz et al., 2015; Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014). However, our recent study (Sallee et al., 2021) indicated support for using this theory in understanding suicide ideation and attempts among non-inpatient early adolescents. Specifically, the findings revealed significance in multiple mediators representing the IPTS constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. The significant drivers for suicide ideation included emotional/mental health and feeling sad/hopeless as the proxy items for perceived burdensomeness, and not straight and bullied as the proxy items for thwarted belongingness. Similarly, the significant drivers for suicide attempt included emotional/mental health and feeling sad/hopeless as the proxy items for perceived burdensomeness, and non-binary and bullied as the proxy items for thwarted belongingness. The current study extends the efforts of using the IPTS in studying suicidality among adolescents to an older age range (ages 16–17). Using the theory to examine suicidal behavior among middle adolescents in school settings can potentially extend its utility and inform practitioners who are working with youth in this age group who struggle with suicide ideation and behavior in various settings such as mental health and medical.

Based on the IPTS, the focus of this study was to examine the extent to which the interpersonal constructs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predict adolescent suicide ideation and attempt. In consideration of the aforementioned needs and gaps in this field of study, we formulated two research questions: 1) To what extent do feelings of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predict suicide ideation among 11th grade students (a middle adolescent population) in Oregon? and 2) To what extent do feelings of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predict suicide attempts among 11th grade students (a middle adolescent population) in Oregon? We hypothesized that the two dynamic IPTS constructs would both statistically significantly predict suicide ideation and suicide attempts in this population.

Method

Participants

A dataset of 10,703 participants was selected from the randomized weighted sample of 11,895 students in 11th grade who participated in the 2017 Oregon Healthy Teen (OHT) survey, a comprehensive assessment measuring risk factors and assets shown to impact successful development (Oregon Health Authority [OHA], 2017). This dataset was selected for its representation of middle adolescents at the cusp of a monumental transition in life—finishing K–12 education and embarking on what is to come. Participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 17 years (M = 16.7 years). In terms of gender identity, 48.9% self-identified as female, 45.6% as male, and 5.5% as non-binary/gender nonconforming, which included those who identified as “transgender, gender nonconforming, genderqueer, gender fluid, intersex/intergender, or something else.” Among the participants, 85.9% spoke English at home. The racial/ethnic composition was as follows: 62.9% White, 25% Hispanic/Latino, 3.6% Asian, 2.2% Black or African American, 5.5% other, and 0.8% multiple.

Procedures

We conducted a secondary analysis of archival survey data collected in the 2017 OHT survey. The 2017 OHT study utilized a probability design (i.e., all participants’ datasets had equal chances to be selected for the sample) to minimize possible selection biases and a randomization process (lottery method or computer-generated random list) to minimize sampling error with stratification of school regions. The survey was administered by school officials during one designated school period, utilizing standardized procedures to protect student privacy and facilitate anonymous participation. The researchers obtained IRB approval prior to requesting and receiving the data in SPSS format from the OHA.

The OHT Dataset

The OHT survey has origins in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a biennial national survey developed by the CDC. The 2017 OHT survey, administered to volunteering eighth and 11th grade students with a school response rate of 83% (R. Boyd personal communication, February 22, 2019), was chosen for this study because it explores a variety of health-related items, including suicidality, and has additional items deemed suitable for proxy descriptors of the IPTS constructs. The 11th grade dataset was selected for the study to target this specific developmental period because of its characteristic of impaired decision-making serving as a risk factor for ideation and behavior. Additionally, adolescents who experience suicidality during this age range are at a higher risk of suicide ideation and attempt in subsequent life stages compared to adolescents who did not experience suicidality at this time (Wyman, 2014).

In this study, the dynamic interpersonal constructs of the IPTS—perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness—served as variables predicting the two outcome variables of suicide ideation and suicide behavior/attempt. The third construct of the IPTS, acquired capability, was not included as a predictor variable because of its staticity and ineffective response to intervention. We were also unable to locate items in the OHT survey that could be used as proxy items for acquired capability. The two predictor variables were measured with proxy items in the OHT survey (OHA, 2017). The proxy items for each predictor variable were chosen based on empirical research (Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014; Seelman & Walker, 2018; Zhao et al., 2010). Both outcome variables (suicide ideation and suicide behavior/attempt) were direct questions in the survey, surveyed as follows: 1) “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” (Yes/No), and 2) “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” (0, 1 time, 2 or 3 times, 4 or 5 times, 6 or more times). The second question was recorded to combine any number of times larger than zero, reflecting the response that either the participant had not attempted suicide (0) or had attempted suicide (1).

Instrumentation

As previously noted, the selection of proxy items was based on previous empirical research on suicidality, adolescent suicidality, and the IPTS (Horton et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2014; Seelman & Walker, 2018; Zhao et al., 2010). The proxy items selected for this specific study differed slightly from the researchers’ previous study with a younger population (early adolescents) because of the developmentally appropriate differences in the eighth and 11th grade OHT survey tools.

The first predictor variable (perceived burdensomeness) was measured with two proxy survey items: emotional/mental health and sad/hopeless feelings. Emotional/mental health was chosen as a proxy item for the predictor variable of perceived burdensomeness because of the research connecting mental health challenges to emotional strain in the family setting, suggesting a potential perception of being a burden on loved ones (Miller et al., 2014). The survey item for emotional/mental health read: “Would you say that in general your emotional and mental health . . .” with the answer options including: 1) Excellent, 2) Very good, 3) Good, 4) Fair, and 5) Poor. The proxy item of sad/hopeless feelings was chosen because of its inclusion in the definition of perceived burdensomeness but exclusion from many studies of the IPTS (Horton et al., 2016). The survey item for sad/hopeless feelings read: “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?” with the answer options of simply Yes or No.

The second predictor variable (thwarted belongingness) was measured with three proxy survey items: sexual orientation, sexual identity, and volunteering (inverse). As previously described, thwarted belongingness constitutes the interpersonal state of loneliness and lack of social connection. Sexual orientation and sexual identity were chosen as proxy items for the variable of thwarted belongingness because sexual minority students experience higher rates of bullying and a greater likelihood of suicidal behaviors (Seelman & Walker, 2018); gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents attempt suicide at 2 to 6 times the rate of non–gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents, suggesting that a sexual minority status is in itself a risk factor for suicidal behaviors, and a child identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual and/or as a non-cisgender youth may experience feelings of thwarted belongingness among a peer group (Zhao et al., 2010). The survey item for sexual orientation read: “Do you think of yourself as . . .” with the answer options including: 1) Lesbian or gay; 2) Straight, that is, not lesbian or gay; 3) Bisexual; 4) Something else (Specify); and 5) Don’t know/Not sure. The survey item for sexual identity read: “How do you identify? (Select one or more responses)” with the answer options including: 1) Female, 2) Male, 3) Transgender,

4) Gender nonconforming/Genderqueer, 5) Intersex/Intergender, 6) Something else fits better (Specify), 7) I am not sure of my gender identity, and 8) I do not know what this question is asking. Volunteering (inverse) was chosen because of its suggestion of contributing to society and feeling a sense of belonging and value within the community. The survey item for volunteering read: “I volunteer to help others in my community” with the answer options including: 1) Very much true, 2) Pretty much true, 3) A little true, and 4) Not at all true. Data from this final question was inversely recoded in order to be comparable to the other proxy items.

The CDC utilized existing empirical literature to analyze the self-reported survey data, assessing for cognitive and situational factors that might affect the validity of adolescent self-reporting of behaviors. Through analysis, it was determined that self-reports are in fact affected by both cognitive and situational factors, but the factors do not threaten the validity of self-reports of each behavior equally (Brener et al., 2013).

Data Analysis

This study addresses what impact the predictor variables of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness have on the outcome variables of suicide ideation and suicide attempt in this particular adolescent population. The selected proxy items had variable answer options (ranging from binary choice to a 7-point Likert scale), so each proxy item for the predictor variables was individually entered with the intention of disaggregating to assess whether or not different combinations of the variables are better predictors of the outcome variables.

The two outcome variables were surveyed as follows: (a) suicide ideation (“During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”) and (b) suicide attempt (“During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”; OHA, 2017). The second question was recoded to allow both questions to be assessed on a binary scale (no/yes), with no equaling 0 and yes equaling 1.

With binary scaled data for the outcome variables, we decided to utilize a binomial logistic regression statistical test to assess the research questions. Additionally, each predictor variable was separately analyzed in order to isolate each outcome variable and consider how the predictor variables influenced each other.

In sum, we examined the descriptive statistics of the survey, created variables based on the selected proxy survey items, and tested the assumptions for utilizing a binomial logistic regression statistical test. Finally, we executed two logistic regression models to determine the relationships between the predictor variables and the two outcome variables—suicide ideation and suicide attempt.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Although 11,868 students in the 11th grade completed the 2017 OHT survey, data from only 10,703 students were included in the analysis because of recording and data collection errors on those excluded from the analyses, due to missing or incomplete data. Therefore, the descriptive statistics of the study variables reported in the table reflect the data of the 10,703 students applicable for use in the logistic regression model of this study. Given the large sample size, we utilized a p-value threshold of less than 0.01.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable |

M or %a |

SD (if applicable) |

| Emotional/Mental Health |

2.92 |

1.22 |

| Felt Sad/Hopeless (Yes) |

1.68 |

0.47 |

| Not Straight |

17.0% |

N/A |

| Non-Binary |

5.5% |

N/A |

| Volunteer |

2.38 |

0.99 |

| Consider Suicide |

18.0% |

N/A |

| Attempt Suicide |

6.6% |

N/A |

a Some variables were reported as means, and some variables were reported as percentages.

Results

A binomial logistic regression was conducted to quantify the effects of the individual proxy items measuring the predictor variables of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness on students experiencing suicide ideation (Research Question 1). All five proxy items were entered into the model for the outcome variable. During the data screening process, two proxy items were eliminated (i.e., non-binary, volunteer), as they did not indicate significant results. Regression results indicated the overall model of the three remaining predictors (emotional/mental health, felt sad/hopeless, not straight) was statistically reliable in distinguishing between 11th grade students who did not experience suicide ideation and those who did (Nagelkerke R2 = .413; p < .001). As such, the suicide ideation model was deemed statistically significant—X2(5) = 3104.194—with an overall positive predictive value of 85.5%.

Of the two proxy items for the perceived burdensomeness variable, both proved to be statistically significant (Table 2). Specifically, increased poor emotional/mental health was related to the increased likelihood and occurrence of suicide ideation. Additionally, participants who reported feeling sad or hopeless for at least 2 weeks were over twice as likely to experience suicide ideation than those who did not report feeling sad or hopeless. Of the three proxy items for the thwarted belongingness variable, only one proved to be statistically significant: Students who reported as not straight were more than twice as likely to experience suicide ideation as students who reported as straight.

Table 2

Logistic Regression Predicting Likelihood of Suicide Ideation

| Variable |

B |

SE |

Wald |

df |

p |

Odds |

| Perceived Burdensomeness |

| Emotional/Mental Health |

0.775 |

.033 |

535.821 |

1 |

< .001 |

2.170 |

| Felt Sad/Hopeless |

−1.694 |

.069 |

609.681 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.184 |

| Thwarted Belongingness |

| Not Straight |

0.705 |

.072 |

95.460 |

1 |

< .001 |

2.025 |

| Non-Binary |

0.149 |

.120 |

1.546 |

1 |

.214 |

1.160 |

| Volunteer |

−0.03 |

.031 |

0.949 |

1 |

.330 |

0.970 |

| Constant |

−1.716 |

.189 |

82.107 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.180 |

Similarly, a binomial logistic regression test was conducted to determine the effects of the proxy items measuring the predictor variables of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness on suicide attempt (Research Question 2). Again, all five items were entered into the model for the outcome variable of suicide attempt. During the data screening process, two proxy items were eliminated (i.e., non-binary, volunteer), as they did not indicate significant results. Regression results indicated that the overall model of the three remaining predictors (emotional/mental health, felt sad/hopeless, not straight) was statistically reliable in distinguishing between 11th grade students who did not attempt suicide and those who did (Nagelkerke R2 = .271; p < .001). The suicide attempt model was deemed statistically significant—X2(5) = 1182.692—with an overall positive predictive value of 93.4%. Both proxy items for the perceived burdensomeness variable proved to be statistically significant (Table 3).

Based on the overall regression analyses, increased poor emotional/mental health was related to the increased likelihood and occurrence of suicide attempt; however, students who reported feeling sad or hopeless for at least 2 weeks were nearly twice as likely to attempt suicide than students who did not report feeling sad or hopeless. Of the three proxy items for the thwarted belongingness variable, only one proved to be statistically significant (Table 3). Students who reported as not straight were nearly twice as likely as students who reported as straight to attempt suicide.

Table 3

Logistic Regression Predicting Likelihood of Suicide Attempt

| Variable |

B |

SE |

Wald |

df |

p |

Odds |

| Perceived Burdensomeness |

| Emotional/Mental Health |

0.599 |

.49 |

149.806 |

1 |

< .001 |

1.820 |

| Felt Sad/Helpless |

−1.856 |

.119 |

242.389 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.156 |

| Thwarted Belongingness |

| Not Straight |

0.533 |

.094 |

31.895 |

1 |

< .001 |

1.704 |

| Non-Binary |

0.055 |

.143 |

0.149 |

1 |

.700 |

1.057 |

| Volunteer |

−0.029 |

.042 |

0.490 |

1 |

.484 |

0.971 |

| Constant |

−2.222 |

.296 |

56.368 |

1 |

< .001 |

0.108 |

These results indicated that there were significant similarities between the predictors of suicide ideation and suicide attempt, supporting our hypotheses. The proxy items that comprised perceived burdensomeness (poor emotional health [odds = 1.820] and feeling sad/hopeless [odds = 6.410]) in conjunction with the proxy item that comprised thwarted belongingness (not straight [odds = 1.704]) all factored into increased likelihood of suicide ideation and suicide attempt. In other words, the mediators of suicide ideation were similar to the mediators of suicide attempt.

Discussion

In discussing the results of the study, it is important to first contextualize the descriptive statistics, as we were studying and applying results to adolescent students in Oregon. The dataset reports 18% of the participants as experiencing suicide ideation, which equates to 1,927 students in the 11th grade. This statistic for suicide ideation is a little higher than the national percentage of 17.2% (CDC, 2017). The dataset also reports 6.6% of the participants as attempting suicide, which equates to 703 students in the 11th grade. This statistic for suicide attempt is a little lower than the national 7.4% (CDC, 2017). In terms of our dataset, Oregon 11th graders were slightly higher than expected for suicide ideation and slightly lower than expected for suicide attempt.

Results from our binomial logistic regression analyses uncovered a model supporting our hypothesis that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness would significantly predict suicide ideation and attempt in 11th grade students. Further, both variables representing perceived burdensomeness were statistically significant for both suicide ideation and attempt, as was one of the three proxy variables representing thwarted belongingness. These findings align with the IPTS, proposing that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are not only important predictors of suicidal behaviors, but are significant elements for both ideation and attempt (with the addition of acquired capability for attempt; Horton et al., 2016; King et al., 2018).

Though not a predetermined hypothesis, it seems reasonable to expect that there would be fewer predictors of suicide attempt, condensed from the predictors of suicide ideation, but that is not the case in our findings. It begs the question: What variables drove students in this population from ideation to attempt? According to the data, 18% of the 11th graders experienced suicide ideation, but only 6.6% reported being driven to attempt suicide. The IPTS would suggest that the missing component was a measure of acquired capability that moves a person from ideation to attempt (Joiner et al., 2009). According to the IPTS (Joiner et al., 2009), experiencing perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness without acquired capability leads to suicide ideation, but the presence of acquired capability is needed to result in suicide attempt. This will be discussed further as a limitation of this study.

These results corroborate previous literature on adolescence and suicidality. Horton et al. (2016) described adolescent perceived burdensomeness as social disconnection and adolescent thwarted belongingness as social isolation from peers. As previously described, with regard to poor emotional/mental health and feeling sad/hopeless, Jaworska and MacQueen (2015) highlighted the increased reactivity of adolescence, and Wyman (2014) indicated that half of the diagnoses of emotional and behavioral disorders take place during this age period (highlighting the importance of mental health clinicians being aware of these findings). With regard to not being straight, this time period also includes establishing values and preferences for sexual behavior and affective orientation (Teipel, 2013). These results also corroborate our previous findings on the application of the IPTS to early adolescents (ages 13–14), suggesting similar significant mediators for both suicide ideation (perceived burdensomeness: emotional/mental health, feeling sad/hopeless; thwarted belongingness: not straight, bullied) and suicide attempt (perceived burdensomeness: emotional/mental health, feeling sad/hopeless; thwarted belongingness: non-binary, bullied; Sallee et al., 2021).

Relative to the literature on suicidality and its role in our selection of proxy items within the OHT survey, research on the connection between poor emotional/mental health and emotional strain in the family setting supports our findings of its significance within the predictor variable of perceived burdensomeness (Miller et al., 2014). The significance of feeling sad/hopeless is supported by previous research discussing its inclusion in the definition of perceived burdensomeness itself (Horton et al., 2016). Sexual minority students experience higher rates of suicidal behaviors, attempting suicide at rates of 2 to 6 times that of straight adolescents (Seelman & Walker, 2018; Zhao et al., 2010). Our findings support this body of research in the significance of being not straight in relation to mental health wellness.

The other proxy predictors examined—being non-binary and volunteering—were not statistically predictive of suicidal behavior. This may be due in part to the developmental tasks and goals characteristic of the period of middle adolescence, or the proxy items themselves may not be significant indicators of the predictor variables in the study, or the wrong indicators were chosen or were conceptualized inaccurately. If that is the case, there would be concerns regarding the construct validity of these indicators and subsequent measures, and because that cannot be proven otherwise, it is a considerable limitation to the study. If the developmental tasks and goals of middle adolescence provide the most insight into the insignificance of being non-binary and volunteering, it is important to consider the developmental period of self-involvement resulting in high expectations of self in combination with low self-concept, impacting an increased drive for peer acceptance (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2021). Eleventh grade students are also preparing for their final year of high school and making plans for what their lives will look like after graduation, requiring a high degree of autonomy and independence. It is interesting to consider the insignificant predictors through this developmental lens. Although 11th grade students are seeking peer acceptance, being non-binary may not be a driver because of developing autonomy and independence.

We consider how the findings of this study might relate to research indicating a higher rate of suicide for sexual/gender minorities compared to youth from historically well-represented communities (Teipel, 2013), but perhaps disaggregating sexual/gender minority and focusing on non-binary youth in particular may impact that conversation. Volunteering could prove to be a protective factor but drive for peer acceptance and reliance on peers may determine whether or not a student in the 11th grade chooses to volunteer as opposed to self-motivation or fulfillment.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Several limitations must be considered when evaluating the findings of this study. First, because of their correlational nature, we were unable to draw any causal conclusions from the results. Relatedly, the results from this study, despite being based on a large sample, described 11th grade students in Oregon who elected to take the survey and had a complete dataset necessary for analysis; the sample was one of convenience, and the extraction of missing datasets impacted the researchers’ ability to gauge the sample’s ability to represent the whole population. As such, generalization of the results to the larger population of adolescents is limited.

Additionally, the data was taken retrospectively from a survey managed by a state government agency; it would have been preferable for us to have input on the questions included in the 2017 OHT survey. Instead, we were forced to select best-fit proxy items that might or might not have been most representative of the predictor variables. Relatedly, and as previously mentioned, there is cause to question the construct validity of these measures, particularly because the selected proxy items do not correlate to other measures of thwarted belongingness in particular. Because we relied on the 2017 OHT survey data, the models for examining the IPTS constructs were incomplete. Lastly, there is a lack of data about unique stressors experienced by students of color related to their social locations, particularly valuable because 25% of the participants were Hispanic/Latino.

Based on our results, despite the limitations previously discussed, there are a variety of avenues for further research on this topic. The first avenue would be to analyze similar data from another state survey or the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey. This would allow researchers to compare results with this study in order to offer more supported generalization to the adolescent population. Another avenue would be to revisit this dataset and theory to consider how they might apply to other behaviors of the adolescent population, such as NSSI and school violence. Further research could revisit this study by creating a survey that would more fully target the interpersonal constructs of the IPTS or create a qualitative or mixed-methods study incorporating additional data sources to examine more in-depth the suicide-related factors and experiences during adolescence.

Another avenue for future research may be to examine additional prospective mediators that may predict the evolution from ideation to attempt because our results presented the exact same predictors for both. Finally, a valuable possibility for future research would be to study factors that might differentially affect students of color and adolescents from sexual minority groups.

Implications

This particular study offers valuable support for the application of the IPTS in working with middle adolescents as well as useful implications for targeting specific interpersonal needs when working with this population. Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may be significant construct predictors of suicide ideation and attempt in adolescents according to the findings. Implications for clinical mental health counselors and other professionals working with this population support the importance of taking a systemic and unique approach to working with adolescents and their families that prioritizes and addresses these specific interpersonal needs individually and collectively.

Specific interventions addressing adolescent interpersonal needs of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness include an array of clinical practices, such as using a suicide screener as part of intake assessments or well-child checks that include items related to these two constructs. Existing suicide intervention modalities need to incorporate and/or integrate the constructs of the IPTS, utilizing counseling goals and interventions that specifically target belongingness and personal value. Further, clinicians must have a basic understanding of the developmental tasks of this period to attend to an adolescent’s stable and productive peer relationships, adoption of personal value systems, and renegotiation of relationships with parents/caregivers, realizing that this transitional stage is also characterized by feelings of grief and loss (Teipel, 2013).

Group counseling is an effective and efficient modality through which a mental health professional can bring together a number of adolescents and facilitate sessions normalizing these developmental tasks and associated feelings. Mental health literacy and bibliotherapy can be used in combination with group counseling, as research has demonstrated their effectiveness on providing structure in the group process, educating adolescents, and fostering connections among the group (Mumbauer & Kelchner, 2017). Groups can also offer parents and caregivers a safe space to navigate family complexities around adolescent suicidality and learn ways to promote a sense of belonging and reduce feelings of burdensomeness among adolescents.

Broader systemic outreach can involve community mental health providers and other professionals collaborating with school stakeholders to offer services such as parent workshops and educator professional development opportunities on understanding suicidality and evidence-based prevention, intervention, and postvention. Partnering with school stakeholders can include consulting on systemic interventions and programming, such as individual student behavior plans, IEPs, and 504 plans, in addition to school- or grade-wide postsecondary transition activities. These consultation and collaboration efforts are often interdependent, in the sense that clinical professionals gain referrals from school stakeholders, and school stakeholders help inform the work of clinical professionals with their adolescent clients.

Through engaging parents, families, school personnel, and their adolescent clients, clinical mental health counselors can work holistically to prevent and intervene in suicidal behaviors by targeting fulfillment and development of interpersonal needs. These findings may have the potential to inform laws and policies through legislative efforts to address adolescent suicide. Clinical mental health counselors have a professional obligation to utilize outcome data to advocate for systemic change to impact clients (Montague et al., 2016), and in this context they may also draw on these findings to provide information to society to assist in advocacy efforts and extend recommendations to professionals working with this population.

Conclusion

The findings of our study support the application of the IPTS in understanding suicidality among middle adolescents, particularly in the ideation model, and are significant in several ways. First, the IPTS has the potential to inform therapeutic interventions in clinical settings, as well as parents and social institutions (e.g., schools and youth development centers), on how best to support youth who experience suicidality. Another focus of our study was on interpersonal factors that are dynamic, rather than static risk factors that may not necessarily be venues for intervention and change for clinicians (e.g., family factors). Third, adolescent clients engaging in suicide ideation and behaviors require interventions that are unique from their adult counterparts and often require environmental and familial interventions as well as individual. Lastly, our findings may serve to provide information to society to assist in advocacy efforts and recommendations for serving adolescent populations within all systems, including laws and policies to address adolescent suicide. Overall, the findings of our study underscore the uniqueness and complexity of this developmental period of adolescence and the importance of theory- and research-based practices. We hope that our findings will inform mental health clinicians, educators, school counselors, parents, and policymakers in their efforts to meet adolescent mental health needs.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2021). Facts for families guide. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/Layout/FFF_Guide-01.aspx

Barzilay, S., Apter, A., Snir, A., Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., Sarchiapone, M., Hadlaczky, G., Balazs, J., Kereszteny, A., Brunner, R., Kaess, M., Bobes, J., Saiz, P. A., Cosman, D., Haring, C., Banzer, R., McMahon, E., Keeley, H., Kahn, J.-P., . . . Wasserman, D. (2019). A longitudinal examination of the interpersonal theory of suicide and effects of school-based suicide prevention interventions in a multinational study of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13119

Becker, S. P., Foster, J. A., & Luebbe, A. M. (2020). A test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1010/j/jad.2019.09.005

Brener, N. D., Kann, L., Shanklin, S., Kinchen, S., Eaton, D. K., Hawkins, J., & Flint, K. H. (2013, March 1). Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System—2013. Recommendations and Reports, 62(1), 1–23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6201a1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behaviors. National YRBS: 1991–2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2017_suicide_trend_yrbs.pdf

Chu, C., Rogers, M. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2016). Cross-sectional and temporal association between non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation in young adults: The explanatory roles of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Psychiatry Research, 246, 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.061

Czyz, E. K., Berona, J., & King, C. A. (2015). A prospective examination of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among psychiatric adolescent inpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12125

Durkheim, É. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology. Free Press.

Horton, S. E., Hughes, J. L., King, J. D., Kennard, B. D., Westers, N. J., Mayes, T. L., & Stewart, S. M. (2016). Preliminary examination of the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an adolescent clinical sample, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0109-5

Jaworska, N., & MacQueen, G. (2015). Adolescence as a unique developmental period. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 40(5), 291–293. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.150268

Joiner, T. E., Ribeiro, J. D., & Silva, C. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their co-occurrence as viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 342–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412454873

Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association.

King, J. D., Horton, S. E., Hughes, J. L, Eaddy, M., Kennard, B. D., Emslie, G. J., & Stewart, S. M. (2018, June). The interpersonal–psychological theory of suicide in adolescents: A preliminary report of changes following treatment. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(3), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12352

Lester, D. (1987). Murders and suicide: Are they polar opposites? Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 5(1), 49–60.

https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2370050106

Miller, A. B., Adams, L. M., Esposito-Smythers, C., Thompson, R., & Proctor, L. J. (2014). Parents and friendships: A longitudinal examination of interpersonal mediators of the relationship between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Research, 220(3), 998–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.10.009

Montague, K. T., Cassidy, R. R., & Liles, R. G. (2016). Counselor training in suicide assessment, prevention, and management. In G. R. Walz & J. C. Bleuer (Eds). Ideas and research you can use: VISTAS 2016. https://bit.ly/Vistas2016

Mumbauer, J., & Kelchner, V. (2017). Promoting mental health literacy through bibliotherapy in school-based settings. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.85

Oregon Health Authority. (2017). Oregon Healthy Teens Survey. https://bit.ly/OHTsurvey2017

Oregon Suicide Prevention. (n.d.). Youth. https://www.oregonsuicideprevention.org/community/youth

Sallee, E., Ng, K.-M., & Cazares-Cervantes, A. (2021). Interpersonal predictors of suicide ideation and attempt among early adolescents. Professional School Counseling, 25(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X211018653

Schneidman, D. (1993). 1993 health care reforms at the state level: An update. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, 78(12), 17–22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10130176

Seelman, K. L, & Walker, M. B. (2018). Do anti-bullying laws reduce in-school victimization, fear-based absenteeism, and suicidality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 2301–2319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0904-8

Stewart, S. M., Eaddy, M., Horton, S. E., Hughes, J., & Kennard, B. (2017). The validity of the interpersonal theory of suicide in adolescence: A review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1020542

Stone, D., Holland, K., Bartholow, B., Crosby, A., Davis, S., & Wilkins, N. (2017). Preventing suicide: A technical package of policy, programs, and practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicidetechnicalpackage.pdf

Teipel, K. (2013, June). Understanding adolescence: Seeing through a developmental lens. State Adolescent Health Resource Center. http://www.amchp.org/programsandtopics/AdolescentHealth/projects/Documents

/SAHRC%20AYADevelopment%20MiddleAdolescence.pdf

Wasserman, D., Hoven, C. W., Wasserman, C., Wall, M., Eisenberg, R., Hadlaczky, G., Kelleher, I., Sarchiapone, M., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Corcoran, P., Cosman, D., Guillemin, F., Haring, C., Iosue, M., Kaess, M., Kahn, J.-P., . . . Carli, V. (2015). School-based suicide prevention programmes: The SEYLE cluster-randomized, controlled trial. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1536–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61213-7

Wyman, P. A. (2014). Developmental approach to prevent adolescent suicides: Research pathways to effective upstream preventative interventions. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 47(3S2), S251–S256. https://doi.org/10.1016/ampere.2014.05.039

Zhao, Y., Montoro, R., Igartua, K., & Thombs, B. D. (2010). Suicidal ideation and attempt among adolescents reporting “unsure” sexual identity or heterosexual identity plus same-sex attraction or behavior: Forgotten groups? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(2), 104–113.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2009.11.003

Emily Sallee, PhD, BC-TMH, LSC, PCLC, is an assistant professor at the University of Montana. Abraham Cazares-Cervantes, PhD, LSC, is an assistant clinical professor at Oregon State University. Kok-Mun Ng, PhD, NCC, ACS, LPC, is a professor at Oregon State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Emily Sallee, 32 Campus Drive #335, Missoula, MT 59834, emily.sallee@umontana.edu.

Aug 18, 2020 | Volume 10 - Issue 3

Melissa Sitton, Tina Du Rocher Schudlich, Christina Byrne, Chase M. Ochrach, Seneca E. A. Erwin

A family systems framework guided our investigation of self-injurious behavior (SIB) in adolescents. As part of a larger study, we collected data examining SIB and family functioning from 29 adolescents (Mage = 15.66) and their caregivers. These adolescents with traits of borderline personality disorder were seeking counseling from community-based practitioners specializing in dialectical behavior therapy. Our primary aim was to better understand the family environment of these adolescents. A second aim was to elucidate interrelations among family communication, roles, problem-solving, affective involvement, affective responsiveness, behavioral control, and conflict and SIB. We found a high rate of SIB among adolescent participants. There was significant congruence between adolescent and caregiver reports of the family environment, with families demonstrating unhealthy levels of functioning in several indicators of family environment. The latent variable of family functioning significantly predicted nonsuicidal and ambivalent SIB. Counselors working with adolescents should consider family functioning when assessing risk for SIB.

Keywords: self-injurious behavior, adolescents, family systems, borderline personality disorder, family functioning

Although emotion dysregulation and unstable personal relationships are common for adolescents, those with symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD) often report more extreme experiences (A. L. Miller et al., 2008). BPD is characterized by impaired or unstable emotional and social functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals with BPD—especially adolescents—may experience impairments in daily functioning as well as within interpersonal relationships (Chanen et al., 2007).

Linehan’s (1993) biosocial theory proposed that BPD can result from an individual’s biological predisposition toward emotion dysregulation and a social environment that amplifies this vulnerability. Given that adolescents spend a substantial amount of time with their family, it is important to examine an adolescent’s familial environment to understand the etiology of BPD symptoms; such examination requires a framework like family systems theory, which emphasizes the relationships between family members rather than focusing on the individual members themselves (Goldenberg & Goldenberg, 2013); this includes family communication, roles, problem-solving, affective involvement, affective responsiveness, and behavioral control (I. W. Miller et al., 2000).

Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB)

Regrettably, it is common for adolescents with BPD to engage in SIB (Kaess et al., 2014). SIB is an umbrella term for all purposeful, self-inflicted acts of bodily harm, whether the intent is suicidal, nonsuicidal (i.e., nonsuicidal self-injury), or ambivalent (i.e., neither strictly suicidal nor nonsuicidal). In fact, SIB is one diagnostic criteria for BPD in adolescents and adults.

Although originally developed to explain the etiology of BPD, the biosocial theory has been applied to the development of SIB as well (Crowell et al., 2009). Countless studies have examined the role of emotion dysregulation and affective reinforcement in SIB, but it is important to also consider the influence of social variables. Indeed, in their four-function model, Nock and Prinstein (2004, 2005) suggested that both affective and social variables can positively and negatively reinforce nonsuicidal SIB. Similarly, Joiner’s (2005) interpersonal theory of suicidal SIB posited that social variables (particularly thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) drive the desire for suicide. Thus, although there are clear links between affective variables and SIB, social variables are also relevant. For adolescents, an important social variable related to SIB is family environment. From the family systems approach, adolescent SIB is best understood when rooted in the context of family environment. As Levenkron (1998) suggested, “the ways in which all the family members relate to each other… [is] the fuel that drives [SIB]” (pp. 125–126).

Although limited in number, some previous studies have examined family environment and SIB in adolescents. For example, Halstead et al. (2014) found that SIB was related to dysfunctional family environments. Studies have also found relationships between adolescent SIB and familial communication (Halstead et al., 2014; Latina et al., 2015) and conflict (Huang et al., 2017). Additionally, Adrian et al. (2011) demonstrated a link between stress and failure to meet expectations of familial roles. To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined SIB and familial problem-solving, affective involvement, affective responsiveness, and behavioral control. However, studies have linked SIB to an individual’s lack of problem-solving skills (Walker et al., 2017), ability to regulate affective responses (Adrian et al., 2011), and behavioral control related to impulsivity and compulsivity (Hamza et al., 2015).

Current Study

Despite the clear influence of family members on SIB (Halstead et al., 2014) and the significant amount of time adolescents tend to spend with family members, more research is needed to evaluate family environment in relation to SIB. Specifically, we investigated the families of treatment-seeking adolescents with traits of BPD who engage in SIB. Our objectives were to: (a) assess family environment using multiple indicators of family functioning, (b) assess SIB in these treatment-seeking adolescents, including SIB done with suicidal intent, nonsuicidal intent, and ambivalence toward life, and (c) evaluate family functioning as a statistical predictor of lifetime SIB.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We used data from a larger ongoing, unpublished study on dialectical behavior therapy. In the larger study, participants were adolescents and young adults who sought counseling from community-based clinicians specializing in dialectical behavior therapy. Participants sought counseling for symptoms of BPD, particularly SIB. The counselors recruited participants for the research study by explaining voluntary research participation during their standard intake process for new clients at the clinic. The counselors also obtained informed consent for research from the participants. The counselors collaborated with researchers at a local university for this larger study, and the university’s IRB approved the study.

For the current study, we used the existing pretest data from the adolescents only (N = 29; Mage = 15.66, SDage = 1.34, age range = 13–18). A majority of the adolescent sample (82.8%; n = 24) reported no previous experience with counseling. This sample was predominately Caucasian (82.8%; n = 24) and most adolescents identified as female (89.7%; n = 26).

Caregiver participants (N = 29) were involved in the adolescents’ treatment and the accompanying research study. Most caregiver participants were the biological mother (81.5%; n = 22) or adoptive mother (7.4%; n = 2). However, a few adolescents were accompanied by an extended family member (7.4%; n = 2) or their biological father (3.7%; n = 1). A majority of adolescents reported that at least one of their caregivers had attended some (22.2%; n = 6) or all (29.6%; n = 8) of college, or some (3.7%; n = 1) or all (29.6%; n = 8) of graduate school.

Most adolescents reported they currently lived with both biological parents (58.6%; n = 17) or at least one biological parent (31.0%; n = 9), though some lived with non-biological parents or caregivers (10.3%; n = 3). Most adolescents (86.2%; n = 25) also reported having at least one sibling; 58.6% of adolescents (n = 17) reported having at least one biological brother, 37.9% had at least one biological sister (n = 11), and 24.1% had a half- or step-sibling (n = 7). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests demonstrated that adolescents did not differ in total SIB based on family characteristics (e.g., number of siblings, number of employed caregivers; all values of p > .05).

Measures

Family Functioning

The Family Assessment Device (FAD; Epstein et al., 1983) is a 53-item measure with a 4-point Likert scale used to rate agreement with statements about how the adolescents’ family members interact and relate to each other (e.g., “After our family tries to solve a problem, we usually discuss whether it worked or not”). Both adolescents and caregivers completed the FAD. Subscales of the FAD assess six dimensions of family functioning, including family problem-solving, roles, communication, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, and behavioral control. The scores for each subscale are averaged, with higher scores indicating worse functioning and more problems within families. The FAD has good test-retest reliability and construct validity (I. W. Miller et al., 1985). In this study, the reliability of the FAD was excellent for both samples (Cronbach’s alpha = .95 for adolescents and .96 for caregivers).

The Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Prinz et al., 1979) assesses self-reported familial interactions within the past two weeks. The CBQ has both an adolescent and a caregiver version; both versions consist of 20 true/false items. Scores can range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more conflict between caregiver and adolescent. Studies have shown that CBQ scores delineated between distressed and non-distressed families (Robin & Foster, 1989). The CBQ has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Rallis et al., 2015; Robin & Foster, 1989), as well as construct validity (Prinz et al., 1979). In the current study, the reliability of the CBQ was excellent for both samples (Cronbach’s alpha = .88 for adolescents and .92 for caregivers).

Self-Injurious Behavior (SIB)

We used the Lifetime Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (LSASI; Linehan & Comtois, 1996) to assess participants’ history of SIB, including frequency, method, and intent. Using 20 items, the LSASI asks participants to report the dates of the most recent and most severe SIB, as well as their lifetime frequency of 11 different methods of SIB with suicidal intent, without suicidal intent, and with ambivalence. Participants also report the total frequency of each SIB method (combining suicidal, nonsuicidal, and ambivalent), and the number of times medical treatment was received for the SIB method. Higher scores indicate more SIB in the past. In the current study, reliability across all SIB intent types (four variables: suicidal SIB, nonsuicidal SIB, ambivalent SIB, and total SIB) was .65. Because the LSASI was designed for clinical use rather than research, to our knowledge there are no existing studies demonstrating the reliability or validity of the LSASI. Notably, this measure was already in use at the counseling clinic, and the decision to use it for this research study was counselor-driven.

Data Analysis

As part of our preliminary analyses, we first tested all variables for the assumptions of analysis. Specifically, when examining the skew and kurtosis of the composite variables, we used ± 2 as our acceptable range of values. Following advice from Tabachnick and Fidell (2019), we transformed variables that did not meet our criteria for normality.

To better understand family functioning, we conducted descriptive analyses for all seven predictive variables (problem-solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavioral control, and conflict) separately for adolescent and caregiver scores. We assessed the degree of healthy family functioning using I. W. Miller et al.’s (1985) suggested cut-off scores, which can be used to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy family environments. We also conducted paired sample t-tests to compare the adolescent and caregiver reports of family functioning.

Next, we tested the fit of our theoretical model of family functioning using structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood as the method of estimation. We used multiple fit indices to assess the model fit. Specifically, the chi-square statistic assesses absolute model fit, demonstrating good fit when not statistically significant. The chi-square test can also be used to compare the relative fit of two models. Additionally, comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) are all indicators of model fit, with 0.95 or higher, 0.05 or lower, and 0.08 or lower indicating good fit, respectively (for more information on SEM fit indices, see Hooper et al., 2008). Notably, Iacobucci (2010) suggested that researchers can use SEM and establish good model fit even with small samples.

We also conducted descriptive analyses of the participants’ self-reported SIB. We left these variables raw (untransformed) to evaluate how participants viewed their own SIB. We examined the specific SIB methods that participants reported using (e.g., cutting, burning) as well as three outcome variables (suicidal SIB, nonsuicidal SIB, and ambivalent SIB; all transformed because of issues with skew and kurtosis).

Lastly, we used SEM to predict SIB with the proposed model of family functioning. Given our small sample size, we conducted this analysis separately for suicidal SIB, nonsuicidal SIB, and ambivalent SIB. We set alpha at .05 for each model; given the small sample size, we did not apply corrections to the alpha for the multiple analyses.

Results

We used SPSS 24.0 and Amos 24 to analyze our data. Because this study was primarily descriptive, we conducted multiple analyses to better understand the family environment of treatment-seeking adolescents, experiences of SIB for adolescents, and the role of family environment in adolescent engagement in SIB.

Family Characteristics and Functioning

Means, standard deviations, and range of scores for the family functioning variables are shown in Table 1. With the exception of the caregiver reports on affective responsiveness and behavioral control, both adolescent and caregiver reports on every subscale of the FAD fell above the McMaster clinical cut-off (see Table 1) described by I. W. Miller et al.’s (1985) cut-off scores, indicating on average all of the families demonstrated unhealthy functioning. It is worth noting that adolescents and their caregivers reported similar levels in five of the seven indicators of family functioning from the FAD and CBQ (e.g., there was no statistical difference between the two reports, all values of p > .05). As shown in Table 1, adolescent and caregiver reports only statistically differed for behavioral control (t[28] = 4.23, p < .001) and communication (t[28] = 2.96, p = .006). Specifically, adolescents reported higher levels of both behavioral control and communication; these high levels are considered indicative of unhealthy or distressed families (I. W. Miller et al., 1985).

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Group Comparisons of Family Functioning Variables as Reported by Adolescents and Caregivers

| Variable |

|

Adolescent |

Caregiver |

|

|

|

Cut-Off |

M |

SD |

Range |

M |

SD |

Range |

t(28) |

p |

| Problem-solving |

2.2 |

2.58 |

0.65 |

1.00–3.80 |

2.29 |

0.57 |

1.40–3.80 |

1.88 |

.071 |

| Communication |

2.2 |

2.56 |

0.37 |

1.83–3.17 |

2.30 |

0.37 |

1.50–3.00 |

2.96 |

.006 |

| Roles |

2.3 |

2.58 |

0.37 |

1.75–3.38 |

2.45 |

0.37 |

1.75–3.38 |

1.57 |

.128 |

| Affective Resp. |

2.2 |

2.34 |

0.68 |

1.00–4.00 |

2.12 |

0.62 |

1.00–3.67 |

1.48 |

.151 |

| Affective Inv. |

2.1 |

2.37 |

0.28 |

1.71–3.00 |

2.44 |

0.23 |

1.86–3.00 |

– 1.61 |

.118 |

| Behav. Control |

1.9 |

2.12 |

0.44 |

1.00–3.11 |

1.77 |

0.41 |

1.00–2.78 |

4.23 |

< .001 |

| Conflict |

— |

9.60 |

4.83 |

0.00–18.00 |

10.05 |

5.67 |

1.00–20.00 |

– 0.46 |

.649 |

Note. Cut-Off = McMaster Cut-Off score; Affective Resp. = Affective responsiveness; Affective Inv. = Affective involvement; Behav. Control = Behavioral control.

We used SEM to test the fit of our theory-driven, congeneric model of family functioning using seven subscales from each source (14 variables; seven for adolescents and seven for caregivers, with the error terms of each subscale correlated between the two sources) to predict family functioning as reported by each source (two latent variables; one for adolescents and one for caregivers). The absolute fit of the model was marginal: χ2(69) = 104.39, p = .004, CFI = 0.79, RMSEA = 0.14, SRMR = 0.14.

In order to reduce variables in our theoretical model, we averaged adolescent and caregiver reports for problem-solving, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, and conflict because these did not statistically differ (all values of p > .05). However, we kept the two reports as separate predictors for communication and behavioral control. This left us with nine predictor variables for subsequent analysis (five averaged predictors and four single-source predictors).

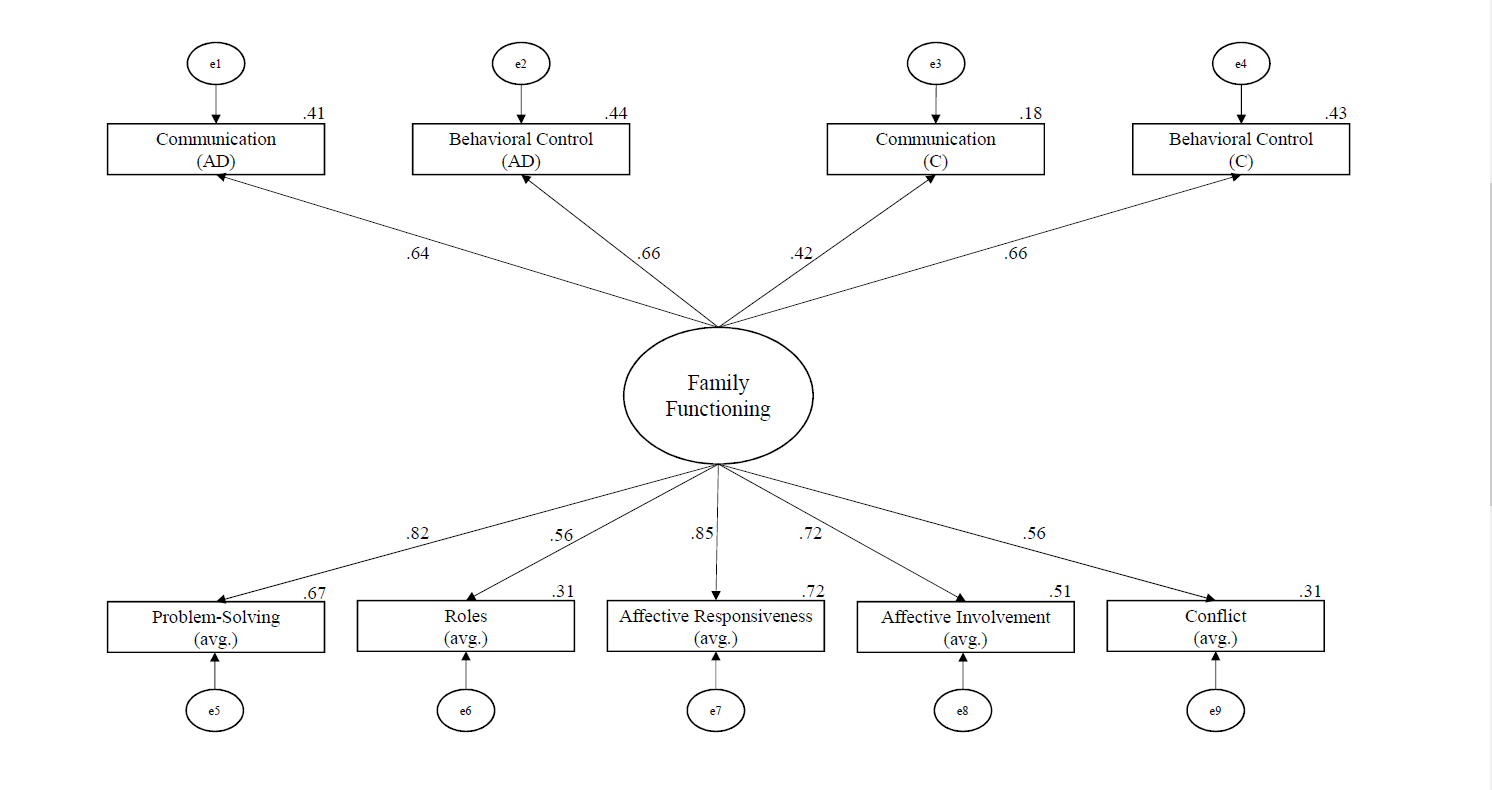

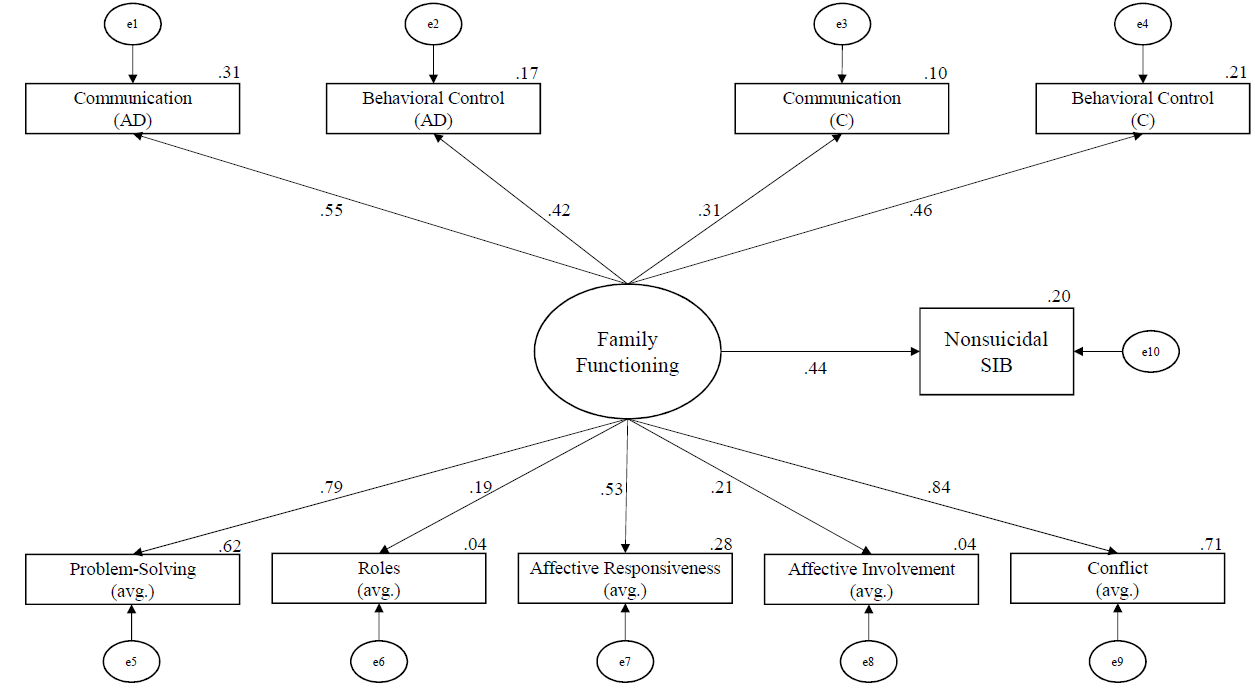

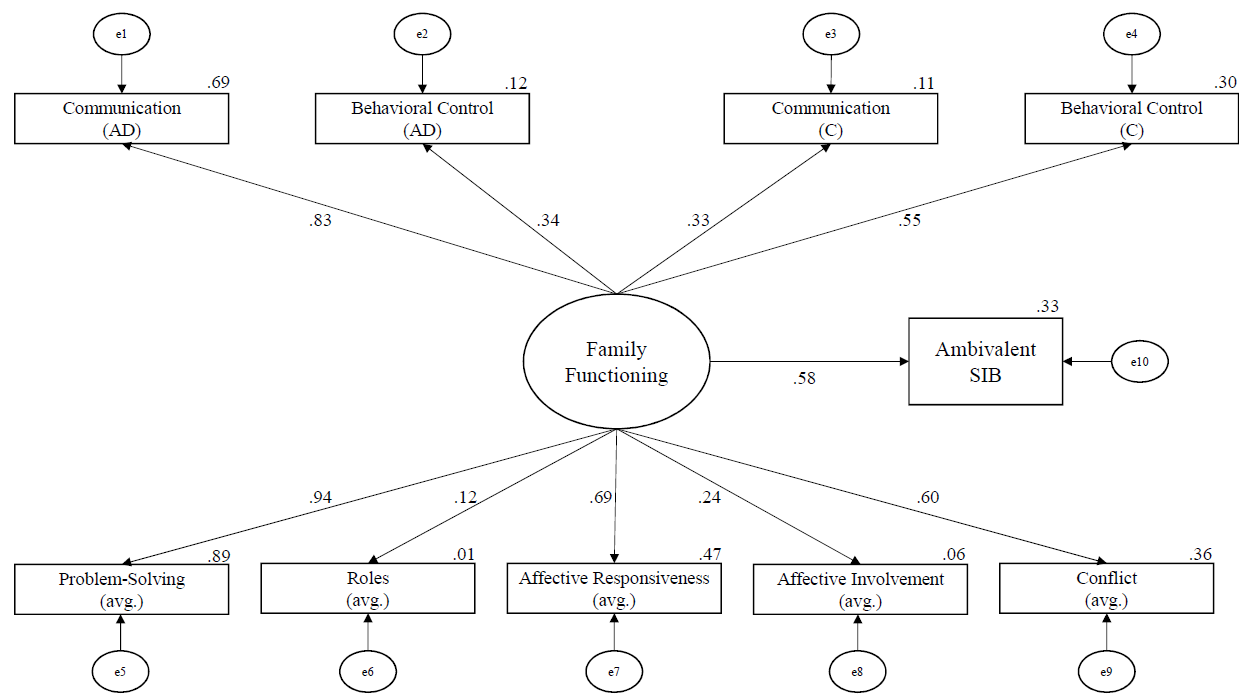

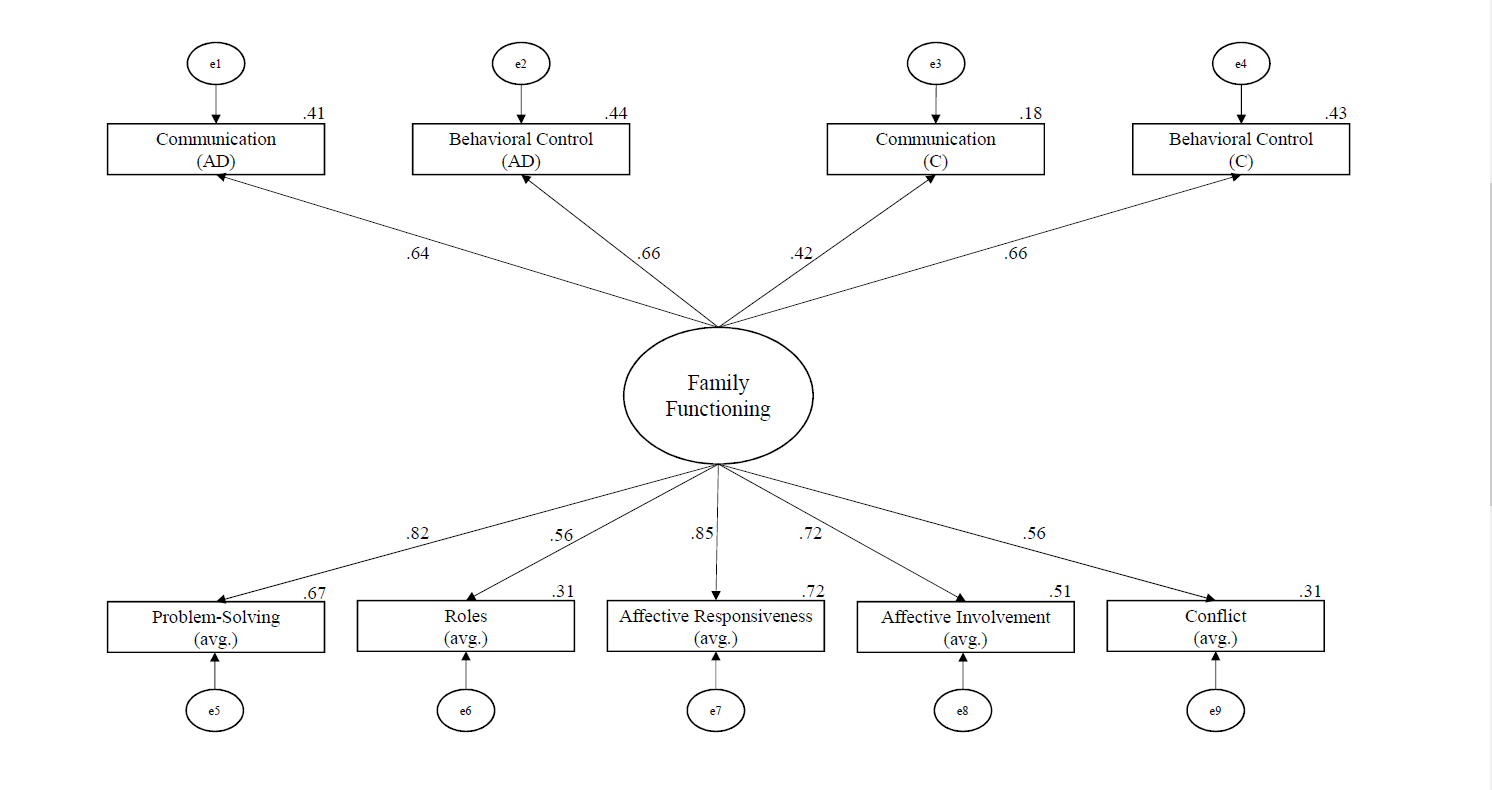

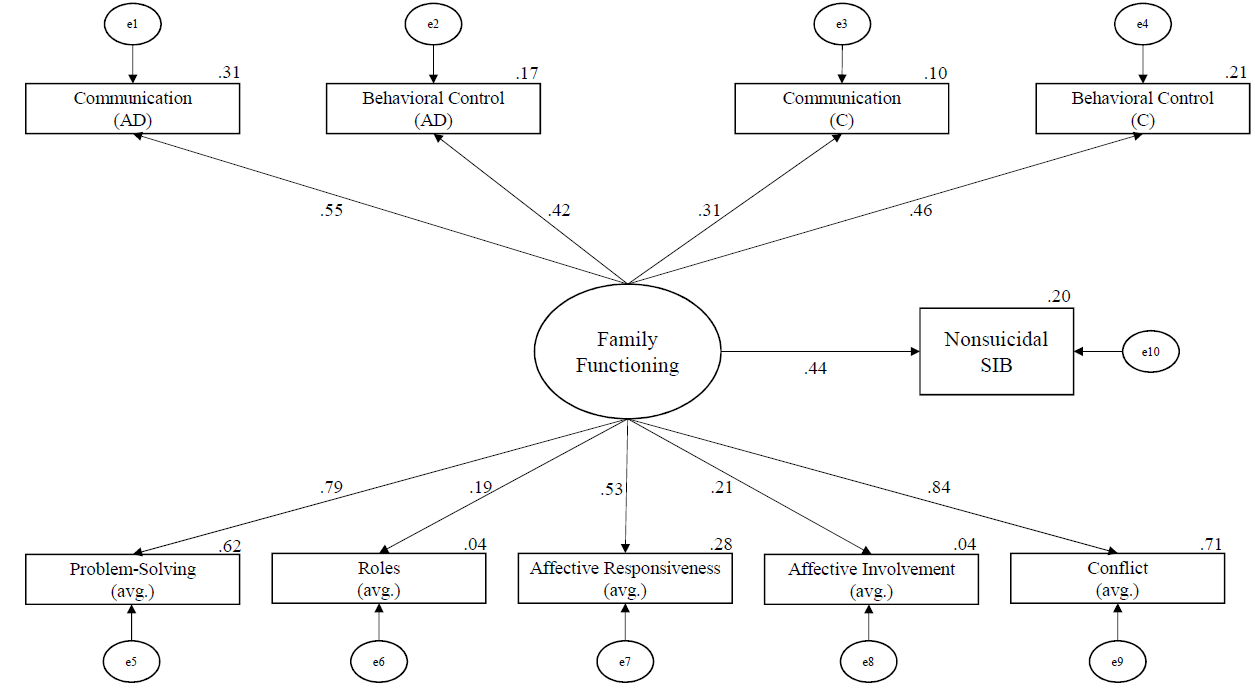

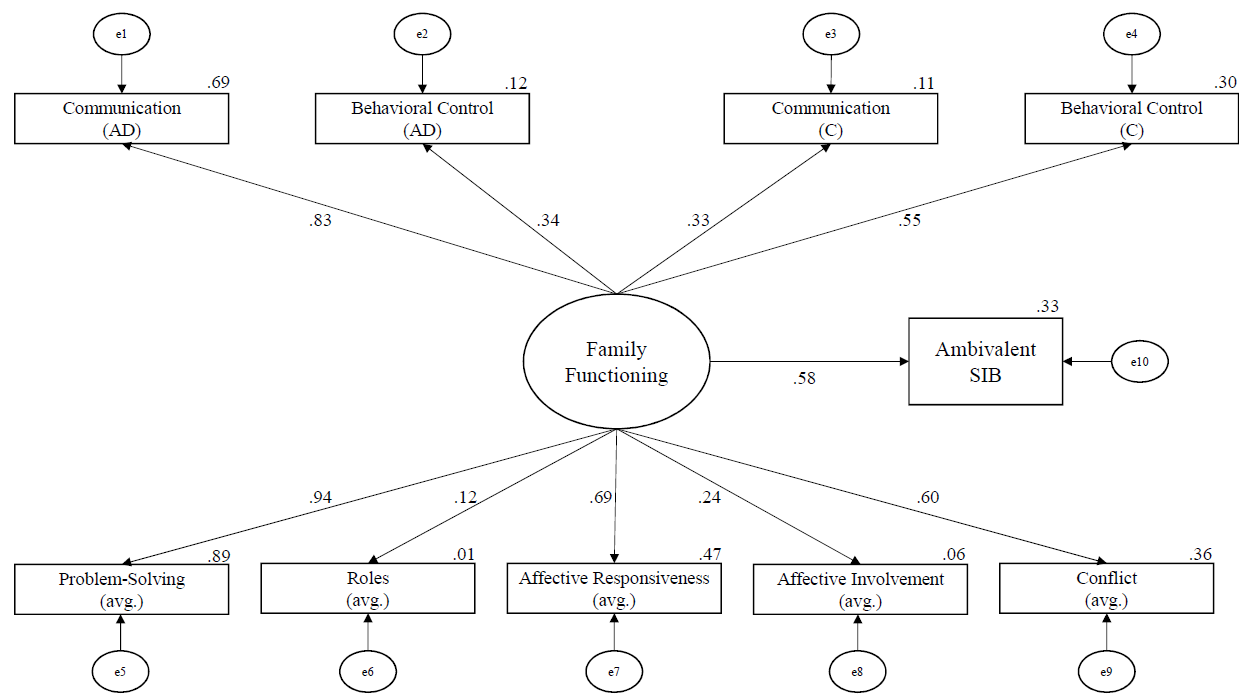

Next, we used SEM to test the fit of the simplified model with the nine observed variables and one latent variable of family functioning. We found that the absolute model fit of this simplified model was acceptable overall. Specifically, the fit indices mostly indicated good fit (χ2[27] = 33.11, p = .194, CFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.08), though one fit index suggested poor fit (RMSEA = 0.09). Differences in the chi-squares of our two models showed the simplified model was statistically better than the initial model: χ2(42) = 71.28, p = .003. Thus, we selected the simplified model as the final model of family functioning (see Figure 1). See Table 2 for descriptive analyses of the nine predictors in the final model. All variables were positively related to family functioning. The strongest predictors of family functioning in this model were affective responsiveness (average of adolescent and caregiver report; β = .85, B = 1.04, SE B = 0.21, p < .001, R2 = .72), affective involvement (averaged; β = .72, B = 0.88, SE B = 0.22, p < .001, R2 = .51), and problem-solving (averaged; β = .82, R2 = .67; this was the constrained parameter used to identify the regression model).

Figure 1

The Output Structural Regression Model of Family Functioning Developed Using SEM

Note. The large circle represents a latent variable, boxes are measured variables, small circles (with “e”) are error terms, and solid lines show regression paths. The numbers on paths are the standardized path coefficients, and the offset values on endogenous variables are the R² effect sizes. (AD) = adolescent report; (C) = caregiver report; (avg.) = averaged score of adolescent and caregiver report.

Table 2

Descriptive Analyses of Predictors of Family Functioning

| Variable |

M |

SD |

| Problem-Solving |

2.43 |

0.44 |

| Roles |

2.51 |

0.29 |

| Affective Responsiveness |

2.23 |

0.51 |

| Affective Involvement |

2.40 |

0.23 |

| Conflict |

9.82 |

4.56 |

| Communication (AD) |

2.56 |

0.37 |

| Communication (C) |

2.30 |

0.37 |

| Behavioral Control (AD) |

2.12 |

0.44 |

| Behavioral Control (C) |

1.77 |

0.41 |

Note. (AD) = adolescent report; (C) = caregiver report.

Adolescent Engagement in SIB

All adolescents reported engaging in SIB in their lifetime, and the average lifetime frequency of SIB was 438.72 (SD = 1,216.65, range = 1–6,079; transformed to address normality: M = 4.41, SD = 1.80). Specifically, most participants reported engaging in nonsuicidal SIB (n = 26) and using it with higher frequency than SIB with other intent (i.e., suicidal or ambivalent SIB), with a lifetime average of 340.16 (SD = 975.22, range = 0–4,565; transformed: M = 3.49, SD = 2.25). Many adolescents also reported engaging in ambivalent SIB (n = 18), with moderate average frequency rates (M = 22.28, SD = 52.02, range = 0–248; transformed: M = 1.62, SD = 1.69). Lastly, fewer adolescents reported engaging in suicidal SIB (n = 18), with the lowest average lifetime frequency (M = 7.34, SD = 25.03, range = 0–136; transformed: M = 0.97, SD = 0.95). See Table 3 for descriptive information on SIB methods (e.g., cutting) used by adolescents in our sample. On average, participants used 3.78 (SD = 2.15) methods of SIB in their lifetime.

Table 3

Descriptive Statistics for All Self-Injurious Behavior Completed in One’s Lifetime (N = 29)

| Variable |

n |

Ma |

SDa |

Rangea |

n of Severe Cases |

| Cutting |

27 |

179.55 |

330.42 |

0–1,500 |

7 |

| Hitting head/body |

16 |

240.90 |

730.59 |

0–3,000 |

0 |

| Overdosing |

13 |

1.88 |

3.59 |

0–15 |

7 |

| Burning |

13 |

6.12 |

14.99 |

0–60 |

1 |

| Strangling/hanging |

8 |

2.18 |

6.42 |

0–30 |

0 |

| Stabbing/puncturing |

8 |

0.80 |

1.64 |

0–7 |