Apr 18, 2017 | Volume 7 - Issue 3

Susannah C. Coaston

Counselors are routinely exposed to painful situations and overwhelming emotions that can, over time, result in burnout. Although counselors routinely promote self-care, many struggle to practice such wellness regularly, putting themselves at increased risk for burning out. Compassion is essential to the helper’s role, as it allows counselors to develop the therapeutic relationship vital for change; however, it is often difficult to direct this compassion inward. Developing an attitude of self-compassion and mindfulness in the context of a self-care plan can create space for an authentic, kind response to the challenges inherent in counseling. This article expands beyond the aspirational aspects of self-compassion and suggests a variety of practices for the mind, body, and spirit, with the intention of supporting the development of an individualized self-care plan for counselors.

Keywords: self-care, self-compassion, burnout, mindfulness, wellness

Wellness, prevention, and human development compose the core of a counselor’s professional identity (Mellin, Hunt, & Nichols, 2011). This fundamental grounding is emphasized within the American Counseling Association’s (ACA) Code of Ethics (ACA, 2014), as well as by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling & Related Education Programs (CACREP; 2016). To fulfill their role in the change process, counselors depend heavily upon compassion, a key component of the therapeutic relationship that—paradoxically—counselors may seldom apply to themselves (Patsiopoulos & Buchanan, 2011). Whereas compassion means being with others in their suffering (Pollack, Pedulla, & Siegel, 2014), self-compassion can be understood as “being touched by and open to one’s own suffering, not avoiding or disconnecting from it, generating the desire to alleviate one’s suffering and to heal oneself with kindness” (Neff, 2003, p. 87). Higher levels of self-compassion can serve as a buffer against burnout (Barnard & Curry, 2011). Therefore, cultivating an attitude of self-compassion may assist counselors in employing self-care practices to refresh, rejuvenate, and recharge their bodies, minds, and souls. The purpose of this manuscript is to reimagine self-care as regular acts of self-compassion that benefit both clients and counselors.

Self-Compassion

Self-compassion, a construct from Buddhist thought, consists of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness, and is characterized by gentleness with oneself when faced with a perceived sense of inadequacy or failure (Neff, 2003). Self-compassion is not based on an evaluation of the self; self-compassion becomes the path to positively relating to oneself (Neff & Costigan, 2014). The concept of self-compassion is consistent with the idea of self-acceptance in the humanistic tradition (Neff, 2003). Carl Rogers (1961) described a successful outcome of psychotherapy as an increase in positive attitudes toward self: “The client not only accepts himself . . . he actually comes to like himself. This is not a bragging or self-assertive liking; it is a rather quiet pleasure in being one’s self” (p. 87). The practice of self-compassion calls for a mindful awareness of emotions, and painful emotions are met with a sense of understanding, connection to our common humanity, and self-kindness (Neff, 2003). Neff and Costigan (2014) described self-compassion’s relationship with pain thusly: “Self-compassion does not avoid pain, but rather embraces it with kindness and goodwill that is rooted in the experience of being fully human” (p. 114). Self-compassion practices have been found to improve psychological functioning in both clinical and non-clinical settings (Neff, Kirkpatrick, & Rude, 2007; Schanche, Stiles, McCullough, Svartberg, & Nielsen, 2011).

Mindfulness is one of the core components of self-compassion and is critical for the awareness of suffering that precedes compassion (Germer & Neff, 2015). Mindfulness is the focusing on the awareness of pain in the present moment, and self-compassion becomes the act of taking that awareness and encouraging kindness toward oneself. The common humanity component of self-compassion becomes one of acknowledgment that, as humans, we are imperfect and make mistakes; recognizing our flawed condition allows for a broader perspective toward our difficulties (Neff, 2003). Adopting such a view of pain reduces the chance of over-identification or getting so wrapped up in one’s emotions that they become exaggerated (Neff & Costigan, 2014). When an individual can recognize pain as a universal occurrence, such a viewpoint then fosters a sense of connection with others who have felt suffering. Pain becomes an uncomfortable but acknowledged part of the human condition. When practicing self-compassion, the self-directed kindness is not done to change the circumstance of suffering, but done because there is suffering. The practitioner asks “What do I need now?” The individual then acts accordingly to provide comfort when experiencing the pain of inadequacy or failure (Germer & Neff, 2015). Learning self-compassion becomes a gift for both clients and the practitioner (Barnett, Baker, Elman, & Schoener, 2007). Making time for one’s self is one way counselors can practice self-care (Patsiopoulos & Buchana, 2011). That self-acceptance can prove vital for counselors, whose work often puts them at a risk for burnout (Yager & Tovar-Blank, 2007).

Counselor Burnout

Burnout is a multidimensional experience consisting of exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy that can result from dissatisfaction with the organizational context of the job position (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Burnout can affect individuals in a variety of ways, with anxiety, irritability, fatigue, withdrawal, and demoralization as major examples (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). Burnout can affect individuals at any point in their career and can hamper productivity and creativity, resulting in a reduction of compassion toward themselves and clients (Grosch & Olsen, 1994). “It is when counseling seems to have little effect that counselors reach despair because their raison d’être for choosing this work—to make a difference in human life—is threatened” (Skovholt, Grier, & Hanson, 2001, p. 171). Caring for others and caring for oneself becomes a difficult balance to achieve for both new and seasoned counselors alike. Carl Rogers (1980) wrote, “I have always been better at caring for and looking after others than I have in caring for myself. But in these later years, I made progress” (p. 80). Self-compassion can serve as a protective factor against such potentially debilitating effects of work-related burnout.

Historically, researchers examined the causes of burnout relating to demographic, personality, or attitudinal differences between individuals (Maslach et al., 2001). Today, burnout is viewed from an organizational standpoint and is concerned with the relationship, or fit, between the person and his or her environment, wherein mismatches can result in burnout over time (Maslach, Leiter, & Jackson, 2012). An individual’s perceptions have a reciprocal relationship with the work environment; how counselors make meaning of their work impacts their satisfaction, commitment, and performance in the workplace (Lindholm, 2003). Counselors experiencing work-related stress and burnout will construct meaning differently and require a tailored self-care plan that reflects their individual assessment of their own fit within their work environment.

Counselor Self-Care

Self-care can be defined as an activity to “refill and refuel oneself in healthy ways” (Gentry, 2002, p. 48). Self-care is vital if we are to remain effective in our role and avoid burnout; however, many counselors do not regularly implement the techniques they recommend to clients in their own lives (O’Halloran & Linton, 2000; Skovholt et al., 2001). Although self-care is widely promoted within the counseling literature, this author contends that inherent in many self-care plans and workplace improvement efforts is the idea that overwhelming work-related stress reflects an inadequacy of the individual. The message in the literature often reflects the view that a counselor’s distress hinges upon inadequate coping resources, poor health practices, or other kinds of personal failing, such as lacking assertiveness or not taking enough time off from work (Bradley, Whisenhunt, Adamson, & Kress, 2013; Killian, 2008; O’Halloran & Linton, 2000). As a result, self-care plans tend to take on the air of a New Year’s resolution, a strategy to get better. This narrow focus reflects the historical view of burnout that focused primarily on its individual dimension, without taking into consideration the organizational, interpersonal, or societal perspectives (Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). When self-care plans are written like self-improvement plans, the opportunities for criticism and judgment abound, particularly for new counselors who struggle with anxiety and self-doubt (Skovholt, 2012). When counselors are suffering, experiencing symptoms of burnout, struggling to maintain healthy professional boundaries (i.e., under- or over-involvement), or feeling as though they are not caring for themselves effectively, shame may cause them to be less likely to seek assistance (Graff, 2008). Some counselors may fear negative repercussions as a result of disclosure, such as being perceived as impaired or having professional competency problems (Rust, Raskin, & Hill, 2013).

Self-care is an ethical imperative (ACA, 2014), because utilizing self-care strategies reduces the likelihood of impairment (ACA, 2010). Issues in a counselor’s personal life, burnout in the workplace, mental or physical disability, or substance abuse can result in impairment (ACA, 2010). Sadly, in a survey completed in 2004, nearly two-thirds of participants knew a counselor that they would identify as impaired (ACA, 2010). Counselors who better manage their self-care needs are more likely to set appropriate boundaries with clients and less likely to use clients to meet their own personal or professional needs (Nielsen, 1988). Self-care education has been integrated into the accreditation standards for counselor training (CACREP, 2016), and there are multiple articles discussing how to incorporate the value of wellness and self-care into counselor education programs (Witmer & Young, 1996; Yager & Tovar-Blank, 2007). For counselor educators and supervisors, monitoring counselors-in-training for possible impairment is an important part of the responsibility of gatekeeping (Frame & Stevens-Smith, 1995). However, despite this attention, both students and practicing professional counselors still struggle to implement self-care (Skovholt et al., 2001; E. Thompson, Frick, & Trice-Black, 2011).

Bradley and colleagues (2013) suggested that many of the self-care suggestions in the literature are too general, focusing mainly on general health practices, such as eating healthily and getting enough sleep, or professional recommendations regarding seeking support from colleagues. A case can be made that a counselor would be better served by employing an overall approach to efforts that are based in a self-compassionate mindset. Therefore, actively seeking awareness of one’s own signs and symptoms that indicate suffering can not only help counselors recognize burnout, it also can provide clues toward the first step in soothing.

Mindfulness represents one possible means of increasing such awareness. Mindfulness allows the practitioner to be present in the moment non-judgmentally (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). To practice self-compassion, a counselor needs to be willing to attend to feelings of discomfort, pain, or suffering and acknowledge the experience without self-recrimination (Germer & Neff, 2015). Consider the experience of having a regular client stop attending sessions and returning calls or abruptly discontinuing services. Although common, the ambiguous loss of a connection with a client can be a source of stress and pain (Skovholt et al., 2001). It also can provide an opportunity. Covey (2010) shared the following quote that is often misattributed to Viktor Frankl: “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom” (p. VI). The space Covey describes is our opportunity to be mindful of the stimulus and choose to offer ourselves compassion in response. Choosing to deny, suppress, or distract to avoid these feelings may cause the counselor to miss the trigger to practice self-care. When such feelings are recognized, the counselor may act compassionately toward himself or herself by normalizing or validating the experience. Within self-compassion, the concept of common humanity becomes crucial to precluding the often-automatic tendency to become self-critical for experiencing discomfort (Neff, 2003). Thoughts such as, “I shouldn’t feel this way,” “Just snap out of it; it’s not so bad,” or “What’s wrong with me?” invalidate the sufferer and may cause the counselor to feel as though self-care is an act of indulgence rather than an essential, self-directed gift of kindness. Expressing kindness through self-care acknowledges that counseling can be both difficult and rewarding, a duality representative of the human condition.

When counselors choose to practice self-care, they enhance themselves and their practice. One participant in a narrative inquiry on self-compassion in counseling stated: “What’s so important about self-compassion? Three words: Avoidance of burnout” (Patsiopoulos & Buchanan, 2011, p. 305). Another participant noted, “When we come from a self-compassionate place, self-care is no longer about these sporadic one-time events that you do when you feel burned out and exhausted. Self-care is something you can do all the time” (Patsiopoulos & Buchanan, 2011, p. 305). The consequence of our job as counselors is working compassionately with suffering, and in doing so we suffer (Figley, 2002).

For someone to develop genuine compassion toward others, first he or she must have a basis upon which to cultivate compassion, and that basis is the ability to connect to one’s own feelings and to care for one’s own welfare. . . . Caring for others requires caring for oneself. (Germer & Neff, 2015, p. 48) Self-care, then, is a vital part of a counselor’s responsibilities to clients and to one’s self.

It is important to remember that counseling can be emotionally demanding for counselors in different ways (O’Halloran & Linton, 2000). Self-compassion encourages remembering the shared human experience (Neff, 2003), as the experience of being a professional counselor can be quite isolating, especially for those working in more independent environments (e.g., school counselors, private practitioners; Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Matthes, 1992). Using mindfulness, counselors can maintain an objective stance that can allow the counselor to view one’s work circumstances with a non-judgmental lens (Newsome, Waldo, & Gruszka, 2012), then act kindly to intervene with a self-care practice that is revitalizing to mind, body, and spirit. Using self-compassion tenets as a guide, self-care plans can be created that are authentic and kind, connect us to the human experience, and reflect a balanced state of self-awareness.

Creating a Self-Compassion–Infused Self-Care Plan

In wellness counseling, optimal functioning of the mind, body, and spirit is the goal for holistic wellness (Myers, Sweeney, & Witmer, 2001). The physical dimension is the most common focus for wellness intervention (Carney, 2007); however, this is quite limiting in a profession that is often sedentary, with long hours and pressure to meet productivity demands (Franco, 2016; Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014; Ohrt, Prosek, Ener, & Lindo, 2015). Maintaining one’s health is important but may not be enough to assuage the emotional demands of a high-touch profession in which a strong professional relationship is combined with the often-conflicting pressures of reimbursement; short-term, diagnosis-focused treatment; and behaviorally based outcomes associated with managed care (Cushman & Gilford, 2000; Freadling & Foss-Kelly, 2014). Developing a collaborative treatment plan is a common practice in counseling; it allows the counselor and the client to determine the possible direction and outcomes for their work together (Kress & Paylo, 2015). In the best case, this plan is individualized, specific, and open to revision when necessary. A good self-care plan can follow the same formula.

What follows are specific suggestions regarding self-care practices that stretch beyond the “should,” the “ought to,” and the New Year’s resolution language. When reading the interventions, consider the question Linder, Miller, and Johnson (2000) suggested for clients when encouraging self-care: “How do you reassure yourself?” (p. 4). The suggestions are organized into mind, body, and spirit; however, these are artificial divisions and some interventions may satisfy in multiple ways.

Interventions for the Mind

Mindfulness is a component of self-compassion, but it can also be used intentionally as a regular practice for self-care. Mindfulness can be described as a dispositional trait, a state of being and a practice (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). The use of mindfulness has been integrated into many facets of counseling practice (I. Thompson, Amatea, & Thompson, 2014). For those attracted to the practice of mindfulness for self-care, non-judgmental awareness can be integrated as a practice (e.g., a set time for engagement in a particular mindfulness exercise) or as a way of being during particular activities within the day. Exercises such as mindful eating, maintaining sensory awareness while washing dishes, or mindful walking can be helpful for those who are looking for brief, everyday opportunities for self-care. Researchers I. Thompson and colleagues (2014) found that higher levels of mindfulness corresponded with lower levels of burnout. Mindfulness has been suggested as a beneficial way to teach self-care in counselor training (Christopher, Christopher, Dunnagan, & Schure, 2006), and also as a way to reduce stress and increase self-compassion in students training to be in helping professions (Newsome et al., 2012). For any number of reasons, not all counselors may find benefit in mindfulness practices; therefore, some may choose methods of self-care that are more mentally invigorating.

Intellectual stimulation in any endeavor is important to maintain engagement, interest, and enjoyment, but such motivation can be particularly helpful when a work position contains routine, mundane, or downright boring tasks. To create a stimulating work life, seasoned professionals find active ways to continue their professional development, which can decrease the boredom that can lead to burnout (Skovholt et al., 2001). Activities for growth and development can include learning something new within counseling or outside the profession, such as learning a new language, or how to make sushi, write code, or play a strategy game such as the ancient board game, Go.

The role of a counselor involves exposure to circumstances of human suffering, painful emotions, and heartbreaking situations, which increases the risk of burnout due to absorption of the clients’ pain (Ruysschaert, 2009). Finding a way to keep and maintain positive memories, cards and notes, compliments or successes—what this author terms warm and fuzzies—either personally or professionally, in a box, folder, jar, or bulletin board, can be a helpful response. Bradley and colleagues (2013) suggested tracking small changes made by clients when discouraged and sharing the progress with co-workers.

Writing can be a powerful intervention in a counseling setting and can benefit both mental and physical health (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999; Riordan, 1996). Counselors can use the medium of writing in a multitude of ways. Whether through journaling, narrative, poetry, musical lyrics, or letters, the act of writing can reduce emotional inhibition (Connolly Baker & Mazza, 2004). Creative writing can be used to access the healing benefits of writing without worry about form or audience (Warren, Morgan, Morris, & Morris, 2010).

Warren et al.’s (2010) The Writing Workout is a way to express, validate, and externalize painful emotions. This wellness approach illustrates how creative writing for self-care can cultivate compassion. Narrative writing strategies can allow the writer to change the outcome of a lived experience or reframe a life experience (Connelly Baker & Mazza, 2004). Creating a narrative of an event can help the storyteller organize details and events, reflect and process thoughts and feelings, and derive meaning from experiences (Pennebaker & Seagal, 1999). A creative, mindful writing intervention could be used to examine a clinical situation that may not have gone as the counselor had hoped, or to creatively explore life lessons derived from a clinical encounter. For some clinicians, writing gives voice to emotions too raw to easily speak aloud (Wright, 2003).

Traditional journaling can allow for self-reflection, increased self-awareness, and growth (Lent, 2009; Utley & Garza, 2011). Journal writing can be inherently self-compassionate. Linder et al. (2000) discussed the use of a non-judgmental journaling practice in which there are no wrong words and writers are encouraged to use random sentences and words that do not make sense. Through almost nonsensical form, journaling offers a sense of safety and freedom, while creating a trusting relationship with the journal. Linder et al. (2000) stated, “Journaling finds the meaning in meaninglessness and negates the emptiness through creating writing from the heart. It is an outlet to tell the truth without being judged” (p. 7).

Beyond the traditional journal, counselors may find alternative ways to use journaling for emotional expression, such as use of bullet journaling or a personal blog online. Bullet journaling uses a rapid-logging approach, or a visual code, to represents tasks, events, and notes in a physical notebook (Bullet Journal, 2017). Keeping a bullet journal is a clever way of managing multiple arenas of one’s life in a single place, and the events and notes categories can be particularly helpful in the practice of journaling for self-care. Events are to be written down briefly and objectively despite the degree of emotional content they carry (Bullet Journal, 2017), offering an opportunity to practice the non-reactive skill of mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Once an event has been entered, the counselor can respond mindfully to it by writing at length on the following page. The notes category for bullet journaling consists of ideas, thoughts, or observations (Bullet Journal, 2017), which could include inspirational quotes, eureka moments, or other insights worth reviewing at a later date. The author can use signifiers (i.e., symbols) to create a legend to provide additional context for an event, note, or task. The bullet journal approach for self-expression exemplifies a creative twist on an old concept to better fit the preferences of the writer. Similarly, scrapbook journaling can be used to accommodate the types of expressive media that resonate with the counselor’s personal style or interests (Bradley et al., 2013). Counselors can use photos, poems, song lyrics, and quotes to reflect their emotional state, and then reflect on the emotional patterns or themes that arise. For counselors who prefer to share their thoughts on the Internet, an online blog can be a cost-effective, accessible medium to express oneself emotionally and share thoughts, feelings, and experiences with others (Lent, 2009). Counselors should consider the risks associated with the use of the Internet and maintenance of confidentiality in an online medium in accordance with the ACA Code of Ethics (2014).

Finally, a simple self-care intervention can involve writing oneself a permission slip or prescription for something. This could be the permission to be imperfect, to take a mental health day, or to run through a sprinkler on a hot day. A writing assignment of this sort expresses kindness in providing the very thing that is needed for an emotional recharge. In some cases, this may involve taking a quiet moment to allow one’s mind to wander. This can occur during a warm bath or shower at the end of the day or while savoring a warm cup of coffee or tea in the afternoon. Although mind-wandering can be a threat to effectiveness and productivity when it occurs at inopportune times, taking time for mind-wandering can relieve boredom, stimulate creative thoughts, and facilitate future planning (Smallwood & Schooler, 2015).

Interventions for the Body

Many self-care plans begin and end with a strong concentration on physical self-care, typically involving making nutritional changes and increasing physical activity (Bradley et al., 2013; E. Thompson et al., 2011). These therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLCs) can have a huge impact on health and well-being (Walsh, 2011). Although the mental health benefits of these types of changes are well documented (Walsh, 2011), a myopic focus on physiological wellness may be limiting, and self-care should include a broader range of ways to cope (E. Thompson et al., 2011). For individuals wishing to focus specifically on such changes, using the imagery of caring for oneself as one does a plant may increase self-awareness of bodily self-care needs (Bradley et al., 2013). Considering one’s needs in this metaphorical way may help counselors increase their own self-compassion by considering their unique needs and the changes they are ready and willing to make. A counselor may indicate they require shade from the sun, which could represent reducing over-stimulating environments; good spacing from other plants, indicating healthy boundaries or alone time; and water and nutrients, which may remind the counselor to keep a pitcher of water on the desk and a bag of almonds in a drawer. Externalizing in this way can be particularly helpful when learning self-compassion because often counselors find it easier to care for others than themselves (Patsiopoulos & Buchanan, 2011).

Although exercise has clear mental health benefits (Callaghan, 2004), for some the concept of exercise may lack appeal or may prove difficult to prioritize within a daily work schedule. The use of stretching, walking, or yoga for a short amount of time may be more easily integrated into a hectic schedule. Yoga has been found to be equivalent to exercise in many mental and physical health domains, but not all types of yoga have been found to improve overall physical fitness as compared to more rigorous exercise (Ross & Thomas, 2010). The practice of yoga has been found to increase acceptance of self and others and reduce self-criticism (Valente & Marotta, 2005). Further, the regular practice of yoga can “provide therapists with a discipline capable of fostering a greater sense of self-awareness and helping to develop a lifestyle that is conducive to their own personal growth and the goals of their profession” (Valente & Marotta, 2005, p. 79).

The benefits of movement go beyond improvements in cardiac and musculoskeletal health, while serving to benefit the mind and the spirit. Dance has been used for centuries as a healing practice (Koch, Kunz, Lykou, & Cruz, 2014) and reduces stress, increases stress tolerance, and improves well-being (Bräuninger, 2012). Marich and Howell (2015) developed the practice of dancing mindfulness, which utilizes dance as the medium for practicing meditation. Dancing mindfulness participants report improvement in emotional and spiritual domains, greater acceptance of self, and an increased ability to use mindfulness in everyday life (Marich & Howell, 2015). However, caring for oneself requires more than just nutrition and movement; self-care plans should metaphorically consider the environment.

Skovholt et al. (2001; Skovholt, 2012) uses the concept of a greenhouse to describe the characteristics for a healthy work environment. Plants flourish within a nurturing greenhouse environment. Likewise, counselors thrive within a work environment that is characterized by a sense of autonomy and fairness; growth-promoting and meaningful work; reasonable expectations and remuneration; and trust, support, and respect among colleagues (Skovholt, 2012). The metaphorical work “greenhouse” contains individualized supports and resources that allow for growth and rejuvenation, but can protect the counselor from the harshness that could characterize their work. Examining and adjusting factors that may be under the counselor’s control, such as breaks between clients; scheduling of clients engaged in trauma work; number of assessments, intakes, or group sessions in one day; or other malleable elements can help create a work day that best meets the needs of the counselor. Strategic planning and focused intentionality allows the counselor to engage fully in each client encounter.

Interventions for the Spirit

Religion and spirituality are important factors within the lives of many clients (Cashwell, Bentley, & Bigbee, 2007). Within the United States, 77% of adults identify with some religious faith (Masci & Lipka, 2016). However, the United States is growing in those who identify as spiritual, with 59% of adults reporting a regular “deep sense of ‘spiritual peace and well-being’” (Masci & Lipka, 2016, para. 2). To attend appropriately and fully to clients’ religious and spiritual needs, counselors also need to care for their own spiritual selves.

Humanistic counselors engage fully with clients to create a genuine connection and are most effective as helpers in areas in which they themselves are stronger and more grounded (Baldwin, 2013). Therefore, when addressing the spiritual concerns of a client, counselors need to be aware of where they are on their own spiritual path. Otherwise, there is no assurance their own religious or spiritual concerns will not create an obstacle for their client’s growth (Sori, Biank, & Helmeke, 2006). A counselor’s spiritual concerns can influence the therapeutic alliance in many ways. Influences can include increased reactivity to the spiritual concerns of the client, decreased recognition of how the client values personal spirituality, or inattention to how the client’s spirituality may be a therapeutic resource or contributing factor to distress (Sori et al., 2006). Sori and colleagues (2006) concluded that failure to be aware of spirituality as an aspect of the human condition can create potential boundary issues, limit a counselor’s understanding of the client due to unexamined beliefs rooted in one’s own spiritual background, and result in difficulty managing the emotional uncertainty and pain of clients due to the counselor’s own struggles with faith. Therefore, engaging in reflection, exploration, or a regular spiritual practice can benefit both the counselor and the client.

Spirituality in counseling has been defined as “the capacity and tendency present in all human beings to find and construct meaning about life and existence and to move toward personal growth, responsibility, and relationship with others” (Myers & Williard, 2003, p. 149). This definition conceptualizes spirituality as a central component of wellness that shapes one’s functioning physically, psychologically, and emotionally, not as separate parts of the whole being (Myers & Williard, 2003). Valente and Marotta (2005) asserted that a healthy spiritual life can be emotionally nourishing and keep burnout at bay. Further, greater self-awareness of one’s spirituality may allow practitioners to be more present with their own suffering and that of their clients. Chandler, Miner Holden, and Kolander (1992) stated that attending to spiritual health when making personal change toward wellness will increase the likelihood of self-transformation and greater balance in life. Because there are many expressions of spirituality, individuals wishing to incorporate spirituality into their self-care plan should consider choosing activities that align with personal goals and are consistent with their values (Cashwell et al., 2007).

A spiritual self-care practice can create an inner refuge (Linder et al., 2000) that can offer sanctuary for a counselor when overwhelmed by personal or professional suffering (Sori et al., 2006). Particularly for those in the exploration phase of their own spirituality, but beneficial for all, conducting a moral inventory can assess how individuals are living in accordance with personal beliefs and values (Sori, et al., 2006). Following the moral inventory, a counselor may create a short list of principles to live by (i.e., a distilled list of values consistent with religious and spiritual ideas that are particularly personally valuable; V. Pope, personal communication, August, 2016). Individual research or joining a spiritual community can be helpful for education, support, and guidance in learning more about a particular religious or spiritual tradition (Cashwell et al., 2007). Some religious traditions, such as Seventh-Day Adventists, offer guidelines for physical and mental exercises, as well as nutritional advice that can be translated into intentional counselor self-care practices. Seventh-Day Adventists have a strong focus on wellness and advocate a vegetarian diet and avoidance of tobacco, alcohol, and mind-altering substances (General Conference of Seventh-Day Adventist World Church, 2016). Further, self-reflection may be regularly incorporated into rituals associated with an important time of year such as Lent or the Days of Awe.

For many, prayer can be a powerful practice for connecting with a higher power. Prayer is an integral part of a variety of spiritual traditions and has been associated with a variety of improvements in health and well-being (Granello, 2013). Spending time in communion with a higher power can be integrated into a regular routine for the purpose of self-care. Meditation also can be a spiritual practice and has a long history of applications and associations with health improvement (Granello, 2013). Broadly speaking, there are two types of meditation: concentration, which involves focusing attention (e.g., repeating a mantra, counting, or attending to one’s breath), and mindfulness, which non-judgmentally expands attention to thoughts, sensations, or emotions present at the time (Ivanovski & Malhi, 2007). These quiet practices can allow the participant moments of silence to achieve various ends, such as relaxation, acceptance, or centering.

Connecting with the earth or nature also can be a practice of spiritual self-care. Grounding exercises such as massage, Tai Chi, or gardening can be helpful to encourage a reconnection with the body and the earth (Chandler, et al., 1992). Furthermore, spending time in nature has been found to be rejuvenating both mentally and spiritually (Reese & Myers, 2012).

Engaging in a creative, expressive art activity for the purposes of spiritual practice and healing can be incredibly powerful to heal mind, body, and soul (Lane, 2005). Novelist John Updike has said, “What art offers is space—a certain breathing room for the spirit” (Demakis, 2012, p. 23). Art can come in many forms. Expressive arts can be a powerful tool of self-expression (Snyder, 1997; Wikström, 2005) and provide many options that can easily be used as self-care interventions. Sometimes the inner critic, need for approval, fear of failure, or a fear of the unknown can create barriers to exploring one’s creative energy (N. Rogers, 1993). Maintaining a self-compassionate attitude can allow counselors to create a safe environment to practice self-care free of judgment.

Use of dance, music, art, photography, and other media can be used intentionally for holistic healing. Through the use of clay, paint, charcoal, or other media, the creator can become in touch with feelings, gain insight, release energy, and discover alternative spiritual dimensions of the self, as well as experience another level of consciousness (N. Rogers, 1993). Music has been found to be both therapeutic and transcendental (Knight & Rickard, 2001; Lipe, 2002; Yob, 2010). There are various ways to incorporate music into a self-care plan depending on interest, access, and preference. In many cultures, music and spirituality are integrally linked (Frame & Williams, 1996). Listening to a favorite hymn, gospel music, or other type of liturgical music can be one way to revitalize the spirit during the workday. Relaxing music has been found to prevent physiological responses to stress and subjective experience of anxiety in one study of undergraduates (Knight & Rickard, 2001). Singing is another way of expressing thoughts and feelings, and for some it can provide a vehicle for self-actualization, connection to a higher power, and self-expression (Chong, 2010). After a long day, singing in the office, in the car, or while cooking dinner can be particularly cathartic.

Conclusion

Counselors are routinely exposed to painful situations, traumatic circumstances, and overwhelming emotions. Consequently, they could benefit from creating a safe place for vulnerability, especially when emotionally overwrought after a long day or a particularly difficult counseling session. To thrive as a counselor, self-care is essential, yet many struggle to care for themselves as they care for their clients. To best achieve holistic wellness, counselors must incorporate interventions for the body, mind, and spirit. Counselors can apply self-compassion principles to the creation of an individualized self-care plan, one that functions to rejuvenate flagging professional commitment and soothe potentially debilitating stress. By cultivating an attitude of self-compassion, counselors may be more attentive to their own needs, reducing the risk of developing burnout and benefitting both clients and themselves. These counselors also may be more effective in assisting clients with overcoming their own barriers to self-care. Similarly, counselors who serve as educators or supervisors can model such principles and routinely ask students and supervisees, “What do you need now?” to increase awareness and the practice of tuning in. Consequently, the self-compassionate counselor learns to create a self-care plan that becomes a balm for burnout.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest or funding contributions for the development of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2010). American Counseling Association’s Task Force on Counselor Wellness and Impairment. Retrieved from http://www.creating-joy.com/taskforce/tf_history.htm

American Counseling Association. (2014). 2014 ACA code of ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author. Retrieved from https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Baldwin, M. (2013). Interview with Carl Rogers on the use of the self in therapy. In M. Baldwin (Ed.), The use of self in therapy (3rd ed., pp. 28–35). New York, NY: Routledge.

Barnard, L. K., & Curry, J. F. (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15, 289–303. doi:10.1007/s11089-011-0377-0

Barnett, J. E., Baker, E. K., Elman, N. S., & Schoener, G. R. (2007). In pursuit of wellness: The self-care imperative. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 603–612. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.603

Bradley, N., Whisenhunt, J., Adamson, N., & Kress, V. E. (2013). Creative approaches for promoting counselor self-care. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 8, 456–469. doi:10.1080/15401383.2013.844656

Bräuninger, I. (2012). Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: A randomized controlled trial (RCT). The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39, 443–450. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2012.07.002

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 211–237. doi:10.1080/10478400701598298

Bullet Journal. (2017). Getting started. Retrieved from http://bulletjournal.com/get-started/

Callaghan, P. (2004). Exercise: A neglected intervention in mental health care? Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 11, 476–483. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00751.x

Carney, J. V. (2007). Humanistic wellness services for community mental health providers. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46, 154–171. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00033.x

Cashwell, C. S., Bentley, D. P., & Bigbee, A. (2007). Spirituality and counselor wellness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46, 66–81. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00026.x

Chandler, C. K., Holden, J. M., & Kolander, C. A. (1992). Counseling for spiritual wellness: Theory and practice. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71, 168–175. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb02193.x

Chong, H. J. (2010). Do we all enjoy singing? A content analysis of non-vocalists’ attitudes toward singing. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37, 120–124. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2010.01.001

Christopher, J. C., Christopher, S. E., Dunnagan, T., & Schure, M. (2006). Teaching self-care through mindfulness practices: The application of yoga, meditation, and qigong to counselor training. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 46, 494–509. doi:10.1177/0022167806290215

Connolly Baker, K., & Mazza, N. (2004). The healing power of writing: Applying the expressive/creative component of poetry therapy. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 17, 141–154. doi:10.1080/08893670412331311352

Council for Accreditation of Counseling & Related Educational Programs. (2016). 2016 CACREP standards. Alexandria, VA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Covey, S. R. (2010). Foreword. In A. Pattakos (Ed.), Prisoners of our thoughts: Viktor Frankl’s principles for discovering meaning in life and work (2nd ed., pp. V–XI). Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cushman, P., & Gilford, P. (2000). Will managed care change our way of being? American Psychologist, 55, 985–996. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.55.9.985

Demakis, J. (2012). The ultimate book of quotations. Seattle, WA: CreateSpace.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 1433–1441. doi:10.1002/jclp.10090

Frame, M. W., & Stevens-Smith, P. (1995). Out of harm’s way: Enhancing monitoring and dismissal processes in counselor education programs. Counselor Education and Supervision, 35, 118–129. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.1995.tb00216.x

Frame, M. W., & Williams, C. B. (1996). Counseling African Americans: Integrating spirituality in therapy. Counseling and Values, 41, 16–28. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.1996.tb00859.x

Franco, G. E. (2016). Productivity standards: Do they result in less productive and satisfied therapists? The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 19, 91–106. doi:10.1037/mgr0000041

Freadling, A. H., & Foss-Kelly, L. L. (2014). New counselors’ experiences of community health centers. Counselor Education and Supervision, 53, 219–232. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2014.00059.x

General Conference of Seventh-Day Adventist World Church. (2016). Living a healthful life. Retrieved from https://www.adventist.org/en/vitality/health

Gentry, J. E. (2002). Compassion fatigue: A crucible of transformation. Journal of Trauma Practice, 1(3–4), 37–61. doi:10.1300/J189v01n03_03

Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2015). Cultivating self-compassion in trauma survivors. In V. M. Follette, J. Briere, D. Rozelle, J. W. Hopper, & D. I. Rome (Eds.), Mindfulness-oriented interventions for trauma: Integrating contemplative practices (pp. 43–58). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Graff, G. (2008). Shame in supervision. Issues in Psychoanalytic Psychology, 30, 79–94.

Granello, P. F. (2013). Wellness counseling. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Grosch, W. N. & Olsen, D. C. (1994). When helping starts to hurt: A new look at burnout among psychotherapists. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Ivanovski, B., & Malhi, G. S. (2007). The psychological and neurophysiological concomitants of mindfulness forms of meditation. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 19, 76–91. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5215.2007.00175.x

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Killian, K. D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Traumatology, 14(2), 32–44. doi:10.1177/1534765608319083

Knight, W. E., & Rickard, N. S. (2001). Relaxing music prevents stress-induced increases in subjective anxiety, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate in healthy males and females. Journal of Music Therapy, 38, 254–272. doi:10.1093/jmt/38.4.254

Koch, S., Kunz, T., Lykou, S., & Cruz, R. (2014). Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41, 46–64.

doi:10.1016/j.aip.2013.10.004

Kress, V. E., & Paylo, M. J. (2015). Treating those with mental disorders: A comprehensive approach to case conceptualization and treatment. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Lane, M. R. (2005). Creativity and spirituality in nursing: Implementing art in healing. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19, 122–125.

Lent, J. (2009). Journaling enters the 21st century: The use of therapeutic blogs in counseling. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 4, 67–73. doi:10.1080/15401380802705391

Linder, S., Miller, G., & Johnson, P. (2000, March). Counseling and spirituality: The use of emptiness and the importance of timing. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Counseling Association, Washington, DC.

Lindholm, J. A. (2003). Perceived organizational fit: Nurturing the minds, hearts, and personal ambitions of university faculty. The Review of Higher Education, 27, 125–149. doi:10.1353/rhe.2003.0040

Lipe, A. W. (2002). Beyond therapy: Music, spirituality, and health in human experience: A review of literature. Journal of Music Therapy, 39, 209–240. doi:10.1093/jmt/39.3.209

Marich, J., & Howell, T. (2015). Dancing mindfulness: A phenomenological investigation of the emerging practice. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing, 11, 346–356. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2015.07.001

Masci, D., & Lipka, M. (2016, January 21). Americans may be getting less religious, but feelings of spirituality are on the rise. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/21/americans-spirituality

Maslach, C., Leiter, M. P., & Jackson, S. E. (2012). Making a significant difference with burnout interventions: Researcher and practitioner collaboration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 296–300. doi:10.1002/job.784

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Matthes, W. A. (1992). Induction of counselors into the profession. The School Counselor, 39, 245–250.

Mellin, E. A., Hunt, B., & Nichols, L. M. (2011). Counselor professional identity: Findings and implications for counseling and interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89, 140–147. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00071.x

Myers, J. E., Sweeney, T. J., & Witmer, J. M. (2001). Optimization of behavior: Promotion of wellness. In D. C. Locke, J. E. Myers, & E. L. Herr (Eds.), The handbook of counseling (pp. 641–652). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Myers, J. E., & Williard, K. (2003). Integrating spirituality into counselor preparation: A developmental, wellness approach. Counseling and Values, 47, 142–155. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.2003.tb00231.x

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–101. doi:10.1080/15298860390129863

Neff, K. D., & Costigan, A. P. (2014). Self-compassion, wellbeing, and happiness. Psychologie in Österreich, 2(3), 114–119. Retrieved from http://self-compassion.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/Neff&Costigan.pdf

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning.

Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 139–154. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

Newsome, S., Waldo, M., & Gruszka, C. (2012). Mindfulness group work: Preventing stress and increasing self-compassion among helping professionals in training. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 37, 297–311. doi:10.1080/01933922.2012.690832

Nielsen, L. A. (1988). Substance abuse, shame and professional boundaries and ethics: Disentangling the issues. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 4, 109–137. doi:10.1300/J020v04n02_08

O’Halloran, T. M., & Linton, J. M. (2000). Stress on the job: Self-care resources for counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 22, 354–364.

Ohrt, J. H., Prosek, E. A., Ener, E., & Lindo, N. (2015). The effects of a group supervision intervention to promote wellness and prevent burnout. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 54, 41–58.

doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2015.00063.x

Patsiopoulos, A. T., & Buchanan, M. J. (2011). The practice of self-compassion in counseling: A narrative inquiry. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42, 301–307. doi:10.1037/a0024482

Pennebaker, J. W., & Seagal, J. D. (1999). Forming a story: The health benefits of narrative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 1243–1254. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1243::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N

Pollack, S. M., Pedulla, T., & Siegel, R. D. (2014). Sitting together: Essential skills for mindfulness-based psychotherapy. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Reese, R. F., & Myers, J. E. (2012). EcoWellness: The missing factor in holistic wellness models. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 400–406. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00050.x

Riordan, R. J. (1996). Scriptotherapy: Therapeutic writing as a counseling adjunct. Journal of Counseling and Development, 74, 263–269. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1996.tb01863.x

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of being. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Rogers, N. (1993). The creative connection: Expressive arts as healing. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

Ross, A., & Thomas, S. (2010). The health benefits of yoga and exercise: A review of comparison studies. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16, 3–12. doi:10.1089=acm.2009.0044

Rust, J. P., Raskin, J. D., & Hill, M. S. (2013). Problems of professional competence among counselor trainees: Programmatic issues and guidelines. Counselor Education and Supervision, 52, 30–42.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00026.x

Ruysschaert, N. (2009). (Self) hypnosis in the prevention of burnout and compassion fatigue for caregivers: Theory and induction. Contemporary Hypnosis, 26, 159–172. doi:10.1002/ch.382

Schanche, E., Stiles, T. C., McCullough, L., Svartberg, M., & Nielsen, G. H. (2011). The relationship between activating affects, inhibitory affects, and self-compassion in patients with Cluster C personality disorders. Psychotherapy, 48, 293–303. doi:10.1037/a0022012

Schaufeli, W., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study & practice: A critical analysis. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis.

Skovholt, T. M. (2012). The counselor’s resilient self. Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Journal, 4(38), 137–146. Retrieved from http://www.pegem.net/dosyalar/dokuman/138861-20140125102831-1.pdf

Skovholt, T. M., Grier, T. L., & Hanson, M. R. (2001). Career counseling for longevity: Self-care and burnout prevention strategies for counselor resilience. Journal of Career Development, 27, 167–176. doi:10.1023/A:1007830908587

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331

Snyder, B. A. (1997). Expressive art therapy techniques: Healing the soul through creativity. Journal of Humanistic Education & Development, 36, 74–82. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4683.1997.tb00375.x

Sori, C. F., Biank, N., & Helmeke, K. B. (2006). Spiritual self-care of the therapist. In K. B. Helmeke & C. F. Sori (Eds.), The therapist’s notebook for integrating spirituality in counseling: Homework, handouts, and activities for use in psychotherapy (Vol. 1, pp. 3–18). Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Press.

Thompson, E. H., Frick, M. H., & Trice-Black, S. (2011). Counselor-in-training perceptions of supervision practices related to self-care and burnout. The Professional Counselor, 1, 152–162. doi:10.15241/eht.1.3.152

Thompson, I., Amatea, E., & Thompson, E. (2014). Personal and contextual predictors of mental health counselors’ compassion fatigue and burnout. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36, 58–77. doi:10.17744/mehc.36.1.p61m73373m4617r3

Utley, A., & Garza, Y. (2011). The therapeutic use of journaling with adolescents. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 6, 29–41. doi:10.1080/15401383.2011.557312

Valente, V., & Marotta, A. (2005). The impact of yoga on the professional and personal life of the psychotherapist. Contemporary Family Therapy, 27, 65–80. doi:10.1007/s10591-004-1971-4

Walsh, R. (2011). Lifestyle and mental health. American Psychologist, 66, 579–592. doi:10.1037/a0021769

Warren, J., Morgan, M. M., Morris, L.-N. B., & Morris, T. M. (2010). Breathing words slowly: Creative writing and counselor self-care—The writing workout. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 5, 109–124.

doi:10.1080/15401383.2010.485074

Wikström, B. M. (2005). Communicating via expressive arts: The natural medium of self-expression for hospitalized children. Pediatric Nursing, 31, 480–485.

Witmer, J. M., & Young, M. E. (1996). Preventing counselor impairment: A wellness approach. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 34, 141–155. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4683.1996.tb00338.x

Wright, J. K. (2003). Writing for protection: Reflective practice as a counsellor. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 16, 191–198. doi:10.1080/0889367042000197376

Yager, G. G., & Tovar-Blank, Z. G. (2007). Wellness and counselor education. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 46, 142–153. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2007.tb00032.x

Yob, I. M. (2010). Why is music a language of spirituality? Philosophy of Music Education Review, 18, 145–151. doi:10.2979/pme.2010.18.2.145

Susannah C. Coaston is an assistant professor at Northern Kentucky University. Correspondence can be addressed to Susannah Coaston, 1 Nunn Drive, MEP 203C, Highland Heights, KY 41099, coastons1@nku.edu.

Oct 15, 2016 | Article, Volume 6 - Issue 4

Patrick R. Mullen, Daniel Gutierrez

The burnout and stress experienced by school counselors is likely to have a negative influence on the services they provide to students, but there is little research exploring the relationship among these variables. Therefore, we report findings from our study that examined the relationship between practicing school counselors’ (N = 926) reported levels of burnout, perceived stress and their facilitation of direct student services. The findings indicated that school counselor participants’ burnout had a negative contribution to the direct student services they facilitated. In addition, school counselors’ perceived stress demonstrated a statistically significant correlation with burnout but did not contribute to their facilitation of direct student services. We believe these findings bring attention to school counselors’ need to assess and manage their stress and burnout that if left unchecked may lead to fewer services for students. We recommend that future research further explore the relationship between stress, burnout and programmatic service delivery to support and expand upon the findings in this investigation.

Keywords: burnout, stress, school counselors, student services, service delivery

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA; 2012) recommends that school counselors enhance the personal, social, academic and career development of all students through the organization and facilitation of comprehensive programmatic counseling services. Delivery of student services is part of a larger framework articulated by ASCA’s National Model (2012) that also includes management, accountability and foundation components of school counseling programs. However, ASCA notes that school counselors should “spend 80 percent or more of their time in direct and indirect services to students” (ASCA, 2012, p. xii). ASCA defines indirect student services as services that are in support of students and involve interactions (e.g., referrals, consultations, collaborations and leadership) with stakeholders other than the student (e.g., parents, teachers and community members). On the other hand, direct student services are interactions that occur face-to-face and involve the facilitation of curriculum (e.g., classroom guidance lessons), individual student planning and responsive services (e.g., individual, group and crisis counseling). In either case, ASCA charges school counselors with prioritizing the delivery of student services.

As a part of their work, school counselors often incur high levels of stress that may result from multiple job responsibilities, role ambiguity, high caseloads, limited resources for coping and limited clinical supervision (DeMato & Curcio, 2004; Lambie, 2007; McCarthy, Kerne, Calfa, Lambert, & Guzmán, 2010). In addition, burnout can result from the ongoing experience of stress (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993; Maslach, 2003; Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998) and can result in diminished or lower quality rendered services (Lawson & Venart, 2005; Maslach, 2003). While research on burnout is common in the school counseling literature (Butler & Constantine, 2005; Lambie, 2007; Wachter, Clemens, & Lewis, 2008; Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006), studies have not focused on the relationship between burnout and school counselors’ service delivery. Yet, burnout has the potential to produce negative consequences for the work rendered by school counselors and could result in fewer services for students (Lambie, 2007; Lawson & Venart, 2005; Maslach, 2003). Therefore, the purpose of this research was to examine the contribution of school counselors’ levels of burnout and stress to their delivery of direct student services.

School Counselors and the Delivery of Student Services

Research on school counselors’ delivery of student services has produced positive findings. In a meta-analysis that included 117 experimental studies, Whiston, Tai, Rahardja, and Eder (2011) identified that, in general, school counseling services have a positive influence on students’ problem-solving and school behavior. Furthermore, in schools where school counselors completed higher levels of student services focused on improving academic success, personal and social development, and career and college readiness, students experienced a variety of positive outcomes, such as increased sense of belongingness, increased attendance, fewer hassles with other students, and less bullying (Dimmitt & Wilkerson, 2012). Moreover, researchers have shown that the higher occurrence of school counselor-facilitated services is beneficial for students’ educational experience and academic outcomes (Carey & Dimmitt, 2012; Lapan, Gysbers, & Petroski, 2001; Wilkerson, Pérusse, & Hughes, 2013). Overall, the services conducted by school counselors have a positive impact on student success. As such, research investigating the factors related to higher incidence of school counselors’ direct student services could provide significant educational benefits to schools.

Researchers have examined a variety of topics that relate to increased student services. Clemens, Milsom, and Cashwell (2009) found that if school counselors had a good relationship with their principal and were engaged in higher levels of advocacy, they were likely to have increased implementation of programmatic counseling services. Another study concluded that school counselors’ values were not associated with the occurrence of service delivery, but researchers did find counselors with higher levels of leadership practices also delivered more school counseling services (Shillingford & Lambie, 2010). Other factors related to increased levels of school counselors’ service delivery are increased job satisfaction (Baggerly & Osborn, 2006; Pyne, 2011) and higher self-efficacy (Ernst, 2012; Mullen & Lambie, 2016). These studies provided notable contributions to the literature; however, at this time no known studies have examined the relationship among school counselors’ burnout, perceived stress and direct student services.

Stress and Burnout Among School Counselors

Stress is a significant issue that relates to the impairment of work performance (Salas, Driskell, & Hughes, 1996) and is a likely problem for school counselors. The construct of stress has a rich history in scientific literature dating back to the 1930s (Cannon, 1935; Selye, 1936). Selye (1980) articulated one of the first broad definitions of stress by defining it as the “nonspecific results of any demand upon the body” (p. vii). Over time, various authors developed an assortment of definitions (Ivancevich & Matteson, 1980; Janis & Mann, 1977; McGrath, 1976), but Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) definition of stress is common among scholars (Driskell & Salas, 1996; Lazarus, 2006). In their Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined stress as a “particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her wellbeing” (p. 19). Lazarus and Folkman conceptualized that stress results from an imbalance between one’s perception of demands or threats and their ability to cope with the perceived demands or threats. Consequently, one’s appraisal of demands and their assessment of their coping ability becomes a critical issue in relationship to whether or not the demand will trigger a stress response.

McCarthy et al. (2010) applied Lazarus and Folkman’s model of stress (1984) to school counselors using an instrument that measures the demands and resources experienced by school counselors called the Classroom Appraisal of Resources and Demands–School Counselor Version (McCarthy & Lambert, 2008). McCarthy et al. (2010) found that school counselors who reported challenging demands as a part of their job also had higher levels of stress. This finding is troubling considering that school counselors oftentimes encounter ambiguous job duties, inconsistent job roles and conflicts in their job expectations (Burnham & Jackson, 2000; Culbreth, Scarborough, Banks-Johnson, & Solomon, 2005; Lambie, 2007; Scarborough & Culbreth, 2008). An additional concern is that stress occurring over an extended period of time can lead to emotional and physical health problems (Sapolsky, 2004) along with increased likelihood of leaving the profession (DeMato & Curcio, 2004). Fortunately, prior research reveals that school counselors have reported low stress levels (McCarthy et al., 2010; Rayle, 2006). Still, research on school counselors’ stress and its effects on the services they provide is important.

An additional factor that we believe may have an impact on direct student services is burnout. Burnout was first recognized in the 1970s (Freudenberger, 1974; Maslach, 1976) and is considered to have significant consequences for counseling professionals (Butler & Constantine, 2005; Lambie, 2007; Lawson, 2007; Lee et al., 2007). The topic of burnout is common in the literature across many disciplines (Schaufeli, Leiter, & Maslach, 2009) and has been given particular attention in school counseling research (Butler & Constantine, 2005; Lambie, 2007; Wachter et al., 2008; Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). Freudenberger (1974, 1986) suggested that burnout results from depleted energy and the feelings of being overwhelmed that emerge from the exposure to diverse issues related to helping others, which over time affects one’s attitude, perception and judgment. Pines and Maslach (1978) described burnout as an ailment “of physical and emotional exhaustion, involving the development of negative self-concept, negative job attitude, and loss of concern and feelings for clients” (p. 234). In 1981, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) was developed as a method to measure one’s experience of burnout in the helping and human service field (Maslach & Jackson, 1981).

More recently, Lee et al. (2007) expanded the measurement of burnout and presented the construct of counselor burnout, which they defined as “the failure to perform clinical tasks appropriately because of personal discouragement, apathy to symptom stress, and emotional/physical harm” (p. 143). Within their model, Lee and associates found that counselor burnout includes the constructs of exhaustion, negative work environment, devaluing clients, incompetence and deterioration in personal life. These constructs correlate with the factors measured by the MBI (Maslach & Jackson, 1981), but provide a definition consistent with the work of school counselors (Gnilka, Karpinski, & Smith, 2015).

Many researchers have explored factors related to school counselor burnout. Overall, scholars have found that school counselors report low levels of burnout (Butler & Constantine, 2005; Gnilka et al., 2015; Lambie, 2007; Wachter et al., 2008; Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). Nonetheless, researchers also reported that higher collective self-esteem is associated with a higher sense of personal accomplishment and lower emotional exhaustion (Butler & Constantine, 2005), whereas higher levels of ego development are associated with higher personal accomplishment (Lambie, 2007). Moreover, Wilkerson and Bellini (2006) discovered that school counselors who handle stressors with emotion-focused coping are at a higher risk of experiencing burnout symptoms, and Wilkerson (2009) established that school counselors’ emotion-focused coping increases their likelihood of experiencing symptoms of burnout. Yet, there is no research on the connection between school counselors’ burnout and the direct student services they provide despite a high likelihood that burnout is the cause of fewer and deteriorated services for students (Maslach, 2003).

The purpose of this study was to build upon existing literature regarding school counselors’ stress, burnout and their facilitation of direct student services. The guiding research questions were: (a) Do practicing school counselors’ levels of burnout and perceived stress contribute to their levels of service delivery? and (b) Do practicing school counselors’ levels of stress correlate with their burnout? Consequently, the following research hypotheses were examined: (a) School counselors’ degree of burnout and perceived stress contributes to their facilitation of direct student services, and (b) School counselors’ degree of perceived stress correlates positively with their level of burnout.

Method

Procedures

To answer the research questions associated with this study, we employed a cross-sectional research design (Gall, Gall, & Borg, 2007). Furthermore, this study utilized online survey data collection procedures. Prior to any data collection, we received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the first author’s university. During the first step in the data collection process, we retrieved the name and e-mail address of every school counselor listed in the ASCA online directory of membership. Next, we generated a simple random sample of school counselors. Then, we sent the sample selected from the ASCA online directory a series of three e-mails that aligned with tailored design method (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2009) recommendations for survey research. Each e-mail contained a brief description of the survey and a link to the online survey managed by Qualtrics (2013). If a participant wished to take the survey, he or she was directed to the Web site that posted the explanation of the study. If they agreed to participate, they would move forward and complete the survey. Participants were screened as to whether they were practicing school counselors or not (e.g., student, counselor educator or retired). Of the 6,500 participants sampled, 41 indicated they were not a practicing school counselor. In addition, 312 e-mails were not working at the time of the survey. Out of the 6,147 practicing school counselors surveyed, 1,304 (21.21% visit response rate) visited the survey Web site and 926 completed the survey in its entirety, which resulted in a 15.06% useable response rate. The response rate received for this study is high in comparison to studies using similar methods (e.g., 14%, Harris, 2013; 11.4%, Mullen, Lambie & Conley, 2014).

Participant Characteristics

Participants (N = 926) were practicing school counselors in private, public and charter K–12 educational settings from across the United States. The mean age was 43.27 (SD = 10.03) and included 816 (88.1%) female and 110 (11.9%) male respondents. The participants’ ethnicity included 50 (5.4%) African Americans, 5 (.5%) Asian Americans, 29 (3.1%) Hispanic Americans, 11 (1.2%) Multiracial, 2 (.2%) Native Americans, 4 (.4%) Pacific Islanders, 811 (87.6%) European Americans, and 13 (1.5%) participants who identified their ethnicity as “Other.” On average, participants had 10.97 (SD = 6.92) years of experience and 401.45 (SD = 262.05) students on their caseload. The geographical location of the participants’ work setting favored suburban (n = 434, 46.9%) and rural communities (n = 321, 34.7%) with fewer school counselors working in urban settings (n = 171, 18.5%). Most participants reported that they worked in the high school grade levels (n = 317, 34.2%) closely followed by elementary (n = 270, 29.2%) and middle school or junior high school (n = 203, 21.9%) grade levels, with 136 (14.7%) respondents working in another grade level format (e.g., grades K–12, K–8, or 6–12).

Measures

This study used the (a) Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI; Lee et al., 2007), (b) the School Counselor Activity Rating Scale (SCARS; Scarborough, 2005), and (c) the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Participants also completed a researcher-created demographics form regarding their personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender and ethnicity) and work-related characteristics (e.g., location type, grade level, caseload, experience as a school counselor and percentage of time they directly work with students).

CBI. The CBI (Lee et al., 2007) is a 20-item self-report measure that examines counselor burnout across five domains. The domains that make up the CBI include: (a) exhaustion, (b) incompetence, (c) negative work environment, (d) devaluing client, and (e) deterioration in personal life. The CBI makes use of a 5-point Likert rating scale that ranges from 1 (never true) to 5 (always true) and examines emotional states and behaviors representative of burnout. Some sample items include “I feel exhausted due to my work as a counselor” (exhaustion), “I feel I am an incompetent counselor” (incompetence), “I feel negative energy from my supervisor” (negative work environment), “I have little empathy for my clients” (devaluing client), and “I feel I have poor boundaries between work and my personal life” (deterioration in personal life). Lee et al. (2007) demonstrated the construct validity of the CBI through an exploratory factor analysis that identified a five-factor solution in addition to a confirmatory factor analysis that supported the five-factor model with an adequate fit to the data.

Gnilka et al. (2015) found support for the five-factor structure of the CBI (Lee et al., 2007) with school counseling using confirmatory factor analysis, which supports the CBI as an appropriate measure for school counselor burnout. Lee et al. (2007) established convergent validity for the CBI based upon the correlations between the subscales on the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (Maslach & Jackson, 198l) and the CBI. In prior research, the Cronbach’s alphas of the CBI subscales indicated good internal consistency (Streiner, 2003) with score ranges of .80 to .86 for exhaustion, .73 to .81 for incompetence, .83 to .85 for negative work environment, .61 to .83 for devaluing client, and .67 to .84 for deterioration in personal life (Lee et al., 2007; Lee, Cho, Kissinger, & Ogle, 2010; Puig et al., 2012). The internal consistency coefficients of the CBI in this investigation also were good (Streiner, 2003) with Cronbach’s alphas of .87 for exhaustion, .79 for incompetence, .84 for negative work environment, .79 for devaluing client, and .81 for deterioration in personal life.

SCARS. The SCARS (Scarborough, 2005) is a 48-item verbal frequency measure that examines the occurrence that school counselors actually perform and prefer to perform components of the ASCA National Model (2012). The SCARS measures school counselors’ ratings of activities based on the four levels of interventions articulated by ASCA (1999) and the ASCA National Model (2003). Unfortunately, a more recent version of the SCARS that articulates the new ASCA National Model (2012) does not exist. Nevertheless, this study utilized two SCARS scales (counseling and curriculum) that measure the incidence of direct student services. To the benefit of this investigation, the direct services measured on the SCARS have not changed in the new edition of the ASCA National Model (2003, 2012). Similar to Shillingford and Lambie (2010) and Mullen and Lambie (2016), this investigation utilized the actual scale, but not the prefer scale, on the SCARS (Scarborough, 2005) because this study sought to examine the frequency that school counselors delivered direct student services, not their preferences and not the difference between their preference and actuality. The subscales that measure direct student services used in this study included the counseling (e.g., group and individual counseling interventions; 10 items) and curriculum (e.g., classroom guidance interventions; 8 items) subscales, whereas the coordination, consultation and other activities scales were not used because they measure indirect activities.

The SCARS (Scarborough, 2005) assesses the frequency of school counselor service delivery with a 5-point Likert rating scale that ranges from 1 (I never do this) to 5 (I routinely do this). Scores on the SCARS can be total scores or mean scores. Some sample items from the counseling subscale are “Counsel with students regarding school behavior” and “Provide small group counseling for academic issues.” Some sample items from the curriculum subscale are “Conduct classroom lessons addressing career development and the world of work” and “Conduct classroom lessons on conflict resolution.” Scarborough (2005) examined the validity by investigating the variances in score on the actual scale based on participant grade level and found that participants’ grade level had a statistically significant effect across the scales with small to large effect sizes (e.g., ranging from .11 to .68[ω2]), which supported the convergent validity of the SCARS. Additionally, construct validity was supported using factor analysis. In prior research using the SCARS, the internal consistency of the counseling and curriculum scales was strong with Cronbach’s alphas of .93 for the curriculum actual scale and .85 for the counseling actual scale (Scarborough, 2005). The internal consistency coefficients of the SCARS actual subscales in this investigation were good (Streiner, 2003) with Cronbach’s alphas of .77 for the counseling scale and .93 for the curriculum scale.

PSS. The PSS (Cohen et al., 1983) is a 10-item self-report measure that examines the participants’ appraisal of stress by asking about feelings and thoughts during the past month. The PSS uses a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) and includes four positively stated items that are reverse coded. Some sample items include, “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things?” (reverse coded), and “In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?” The PSS has been shown to have acceptable internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .84 to .91 (Chao, 2011; Cohen et al., 1983; Daire, Dominguez, Carlson, & Case-Pease, 2014). The internal consistency coefficient of the PSS in this study also was acceptable (Streiner, 2003) with a Cronbach’s alpha of .88.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

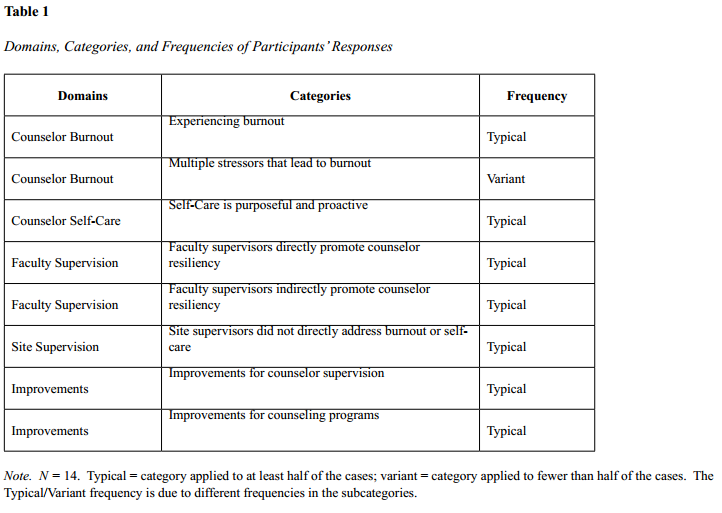

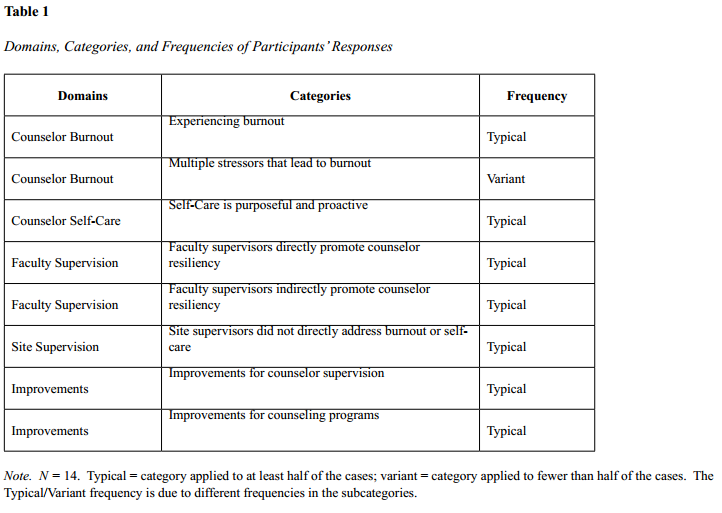

Initial screening of the data included the search for outliers (e.g., data points three or more standard deviations from the mean) using converted z-scores (Osborne, 2012), which resulted in identifying 21 cases that had at least one variable with an extreme outlier. To accommodate for these outliers, the researchers utilized a Windorized mean based on adjacent data points (Barnett & Lewis, 1994; Osborne & Overbay, 2004). Next, the assumptions associated with structural equation modeling (SEM) were tested (e.g., normality and multicollinearity; Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Multicollinearity was not present with these data; however, the data violated the assumption of normality of a single composite variable (e.g., devaluing clients scale on the CBI). Researchers conducted descriptive analyses of the data using the statistical software SPSS. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations and correlations for the study variables.

Model Testing

This correlational investigation utilized a two-step SEM method (Kline, 2011) to examine the research hypothesis employing AMOS (version 20) software. The first step included a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to inspect the measurement model of burnout and its fit with the data. Then, a structural model was developed based on the measurement model. The measurement model and structural model were appraised using model fit indices, standardized residual covariances, standardized factorial loadings and standardized regression estimates (Byrne, 2010; Kline, 2011). Modifications to the models were made as needed (Kline, 2011). Both the measurement and the structural models employed the use of maximum likelihood estimation technique despite the presence of non-normality based on recommendations from the literature (Curran, West, & Finch, 1996; Hu, Bentler, & Kano, 1992; Lei & Lomax 2005; Olsson, Foss, Troye, & Howell, 2000).