Aug 10, 2022 | Volume 12 - Issue 2

Lacey Ricks, Malti Tuttle, Sara E. Ellison

Quantitative methodology was utilized to assess factors influencing veteran school counselors’ decisions to report suspected child abuse. Veteran school counselors were defined as having 6 or more years of experience working as a school counselor within a public or private school. This study is a focused examination of the responses of veteran school counselors from a larger data set. The results of the analysis revealed that academic setting, number of students within the school, and students’ engagement in the free or reduced lunch program were significantly correlated with higher reporting among veteran school counselors. Moreover, veteran school counselors’ self-efficacy levels were moderately correlated with their decision to report. Highly rated reasons for choosing to report suspected child abuse included professional obligation, following school protocol, and concern for the safety of the child. The highest rated reason for choosing not to report was lack of evidence. Implications for training and advocacy for veteran school counselors are discussed.

Keywords: child abuse, reporting, veteran school counselors, self-efficacy, training

In 2019, approximately 4.4 million reports alleging maltreatment were made to U.S. child protective services (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [HHS] et al., 2021). Of these reports, nearly two thirds were made by professionals who encounter children as a part of their occupation. Child maltreatment is identified as all types of abuse against a child under the age of 18 by a parent, caregiver, or person in a custodial role, and includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect (Fortson et al., 2016). Public health emergencies, such as the continued COVID-19 pandemic, increase the risk for child abuse and neglect due to increased stressors (Swedo et al., 2020). Factors such as financial hardship, exacerbated mental health issues, lack of support, and loneliness may contribute to increased caregiver distress, ultimately resulting in negative outcomes for children and adolescents (Collin-Vézina et al., 2020).

The psychological impact of child abuse and neglect on victims can increase the risk of mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Heim et al., 2010; Klassen & Hickman, 2022). Similarly, trauma experienced in childhood is associated with higher rates of long-term physical health issues when compared to individuals with less trauma; these include cancer (2.4 times more likely to develop), diabetes (3.0 times as likely to develop), and stroke (5.8 times more likely to experience; Bellis et al., 2015). Children who are victims of child abuse and neglect may also experience educational difficulties, low self-esteem, and trouble forming and maintaining relationships (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2019).

Voluntary disclosure of childhood abuse is relatively uncommon; one study found that less than half of adults with histories of abuse reported disclosing the abuse to anyone during childhood, and only 8%–16% of those disclosures resulted in reporting to authorities (McGuire & London, 2020). For this reason, mandated reporting by professionals is an integral piece of child abuse prevention. School counselors, by virtue of their ongoing contact with children, are uniquely positioned to identify and report child abuse (Behun et al., 2019). We recognize that school-based professionals such as teachers, administrators, and other school-based staff are mandated reporters as well. However, for the purpose of this article, we specifically focus on school counselors based on their role, responsibility, and training that best equips them to fulfill this expectation. School counselors have a unique role within the school system and play a critical role in ensuring schools are a safe, caring environment for all students (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2017). School counselors also work to identify the impact of abuse and neglect on students as well as ensure the necessary supports for students are in place (ASCA, 2021).

Ethical and Legal Mandates for Reporting Suspected Child Abuse

Although current estimates for the reporting frequency within schools are not available, it appears likely that high numbers of school counselors encounter the decision to report suspected child abuse each year. In fact, a 2019 survey of 262 school counselors indicated that 1,494 cases of child abuse had been reported by participants over a 12-month period (Ricks et al., 2019). Despite the frequency with which it occurs, reporting can be a distressing part of school counselors’ responsibilities (Remley et al., 2017); this could be because of limited knowledge or competency in reporting procedures, unfamiliarity with the law, or potential repercussions for the child (Bryant, 2009; Bryant & Milsom, 2005; Lambie, 2005). Additionally, laws, definitions, and mandates of child abuse and neglect vary by state; therefore, confusion may arise when school counselors relocate to another area (ASCA, 2021; Hogelin, 2013; Lambie, 2005; Tuttle et al., 2019). School counselors need to identify and familiarize themselves with the unique laws in their state in addition to reviewing federal law and ethical codes.

Federally, school counselors are mandated by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974, Public Law 93-247, to report suspected abuse and neglect to proper authorities (ASCA, 2021). Failure to report suspected abuse could result in civil or criminal liability (Remley et al., 2017; White & Flynt, 2000). ASCA Ethical Standards echo this mandate, directing school counselors to report suspected child abuse and neglect while protecting the privacy of the student (ASCA, 2022a, A.12.a). School counselors should also assist students who have experienced abuse and neglect by connecting them with appropriate services (ASCA, 2022a). Moreover, school counselors should work to create a safe environment free from abuse, bullying, harassment, and other forms of violence for students while promoting autonomy and justice (ASCA, 2022a).

School Counselors as Advocates in Mandated Reporting

Barrett et al. (2011) recognized school counselors as social justice leaders based on their role to advocate for students who are underserved, disadvantaged, maltreated, or living in abusive situations. Child abuse impacts children and adolescents from every race, socioeconomic status, gender, and age (Lambie, 2005; Tillman et al., 2015). School counselors who are trained to provide culturally sustaining school counseling will work with students and families from all demographics to promote student wellness within their comprehensive school counseling program (ASCA, 2021). As leaders within the school, school counselors, and especially veteran school counselors, can work to educate all stakeholders on the implications of child abuse.

School counselors not only are legally positioned to serve as mandated reporters but also ethically positioned to train school personnel in recognizing and identifying child abuse symptoms and in reporting procedures (Hodges & McDonald, 2019). Training of school personnel, such as teachers, to identify and report suspected child abuse is essential because they are also recognized legally as mandated reporters (Hupe & Stevenson, 2019) and they interact with students daily. It is vital that school counselors advocate for ongoing comprehensive training related to child abuse because their knowledge affects many stakeholders in the school setting (ASCA, 2021; Tuttle et al., 2019).

Self-Efficacy Among Veteran School Counselors

Previous literature from this data set highlighted the reporting behaviors of early career school counselors (Ricks et al., 2019), and a framework was developed to assist new professionals in reporting (Tuttle et al., 2019). However, the child abuse reporting behaviors and needs of veteran school counselors are understudied. Therefore, this article focuses on veteran school counselors. For the purpose of this study, veteran school counselors are considered licensed school counselors having 6 or more years of experience. Professional literature has highlighted the unique needs and experiences of novice counselors as compared to veteran school counselors (Buchanan et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2017). One study (Mishak, 2007) examined differences in instructional strategies for early career and veteran school counselors in elementary schools in Iowa. Although that study does not specifically address child abuse reporting, it does highlight differences found among the respondents based on their experience level.

One factor supporting the unique needs of veteran school counselors is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy theory posits that an individual’s expectations of mastery are strongly influenced by personal experience and indirect exposure to a phenomenon (Bandura, 1977, 1997). Veteran school counselors, based on their years of experience in a school setting, are likely to have multiple exposures to child abuse reporting. They may have filed reports themselves, spoken to peers about their reporting experiences, or assisted other professionals in the school with reporting. Bandura (1997) suggested that self-efficacy is supported when individuals not only possess the skill and ability to complete a task, but also have the confidence and motivation to execute it.

Veteran school counselors can receive ongoing training from workshops, university courses, webinars, district training, or other professional organizations that may further impact self-efficacy levels. Previous research has shown that as an individual’s knowledge of child abuse increases, their levels of self-efficacy in recognizing or reporting child abuse also increases (Balkaran, 2015; Jordan et al., 2017). However, little research linking school counselors’ self-efficacy levels to child abuse reporting has been published. Despite the paucity of research on this topic, Ricks et al. (2019) found a moderate relationship between early career school counselors’ self-efficacy and their ability to identify types of abuse. Additionally, Tang (2020) found that school counseling supervision increased school counselor self-efficacy; differences between early career and veteran school counselors were not addressed in Tang’s study. Although the positive correlation found by Tang did not directly address child abuse reporting, assisting students with crisis situations was one of the principal components of the analysis. Even though veteran school counselors have experience serving as mandated reporters, they require ongoing professional development in this area to effectively fulfill their roles as advocates in maintaining the welfare and safety of students (ASCA, 2021; Tuttle et al., 2019). Therefore, we seek to utilize this article as a form of advocacy on behalf of veteran school counselors by providing additional research and literature in the field.

Purpose of the Present Study

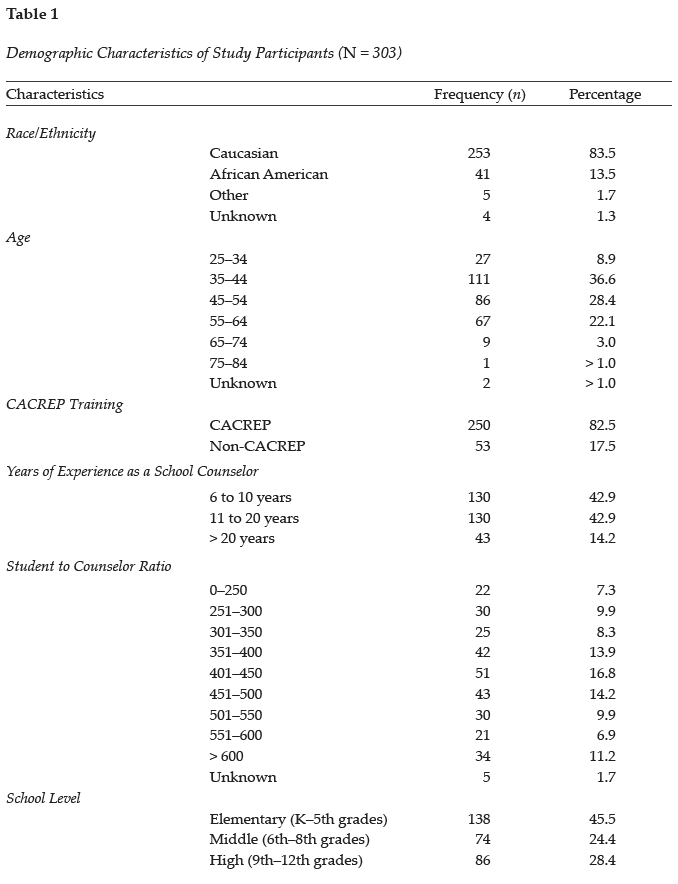

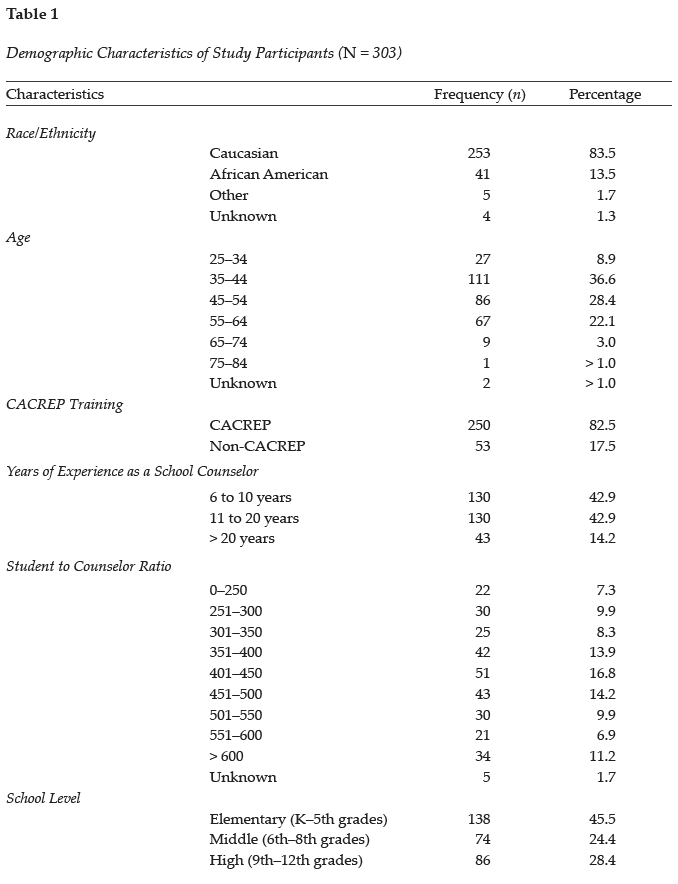

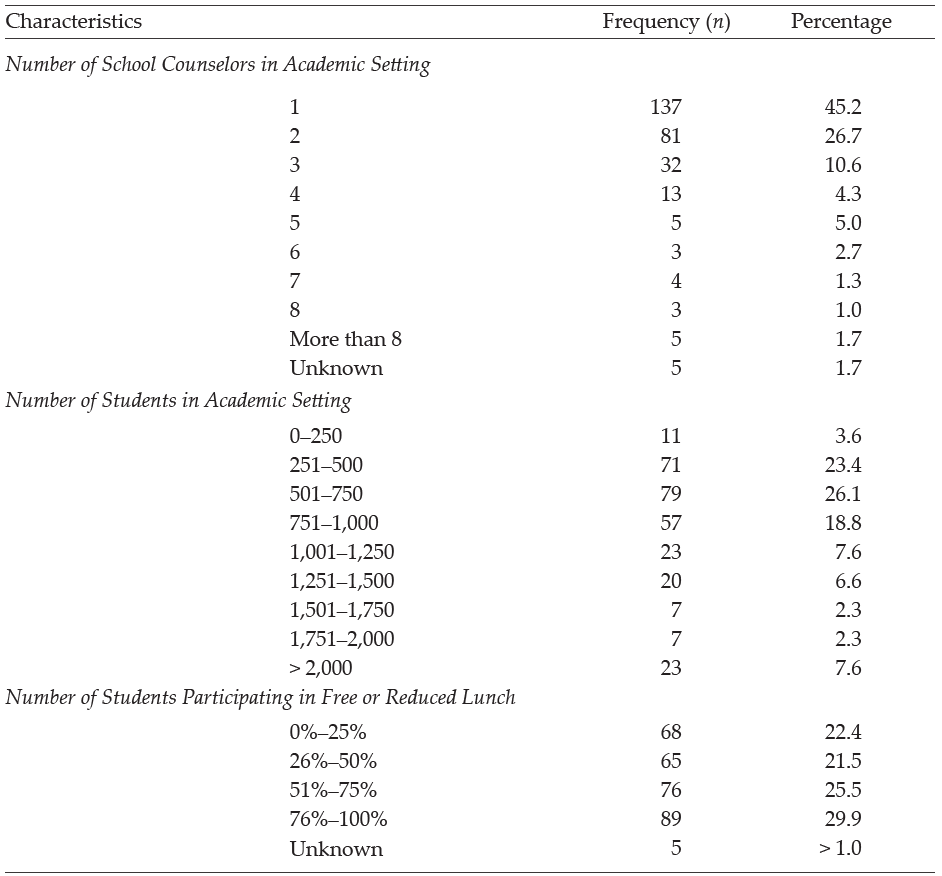

The purpose of this quantitative study is to examine (a) the prevalence of child abuse reporting by veteran school counselors within the school year; (b) the factors affecting veteran school counselors’ decisions to report or not report suspected child abuse; (c) reasons for reporting or not reporting suspected child abuse by veteran school counselors; and (d) veteran school counselors’ self-efficacy levels related to child abuse reporting. Our intent was to build upon an initial larger study to examine veteran school counselors’ knowledge of procedures and experiences with child abuse reporting. The present study is a focused examination of the data collected from veteran school counselors as part of the primary study, which solicited data from school counselors across their careers related to their experiences with child abuse reporting (see Ricks et al., 2019). Demographic variables were collected from participants to assess their impact on child abuse reporting; see Table 1 for a complete list of variables.

Methods

Multiple correlation and regression analyses were conducted to assess factors influencing veteran school counselors’ decisions to report suspected child abuse. After obtaining IRB approval, the authors recruited school counselors in the Southeastern United States (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia). Participants were recruited using a professional school counseling association membership list, a southeastern state counseling association listserv, and social media. Participants were informed that participation in the online study was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were also informed that the survey would take between 10–15 minutes and that the information collected in the survey would remain anonymous.

Participants

A total of 848 surveys were collected from participants. Veteran school counselor data was extracted from the total sample and analyzed to assess the unique experiences of these individuals in child abuse reporting. Veteran school counselors were defined as having 6 or more years of experience working as a school counselor within a public or private school. Four hundred and twenty-eight veteran school counselors began the survey, but data from 125 participants was excluded from the analysis for incomplete responses, resulting in a final sample of 303 participants. Most participants (n = 265, 87.5%) reported being licensed/certified as a school counselor. Some participants may not have possessed a license because of working in the private school sector or working on a provisional basis. See Table 1 for all demographic frequencies and percentages related to participants in the study.

Measures

Three measures were selected and employed as part of the larger study. These included the Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire (Bryant & Milsom, 2005), the School Counselor Self-Efficacy Scale (Bodenhorn & Skaggs, 2005), and the Knowledge of Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire (Ricks et al., 2019). Each measure is described below as previously reported in Ricks et al. (2019).

Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire

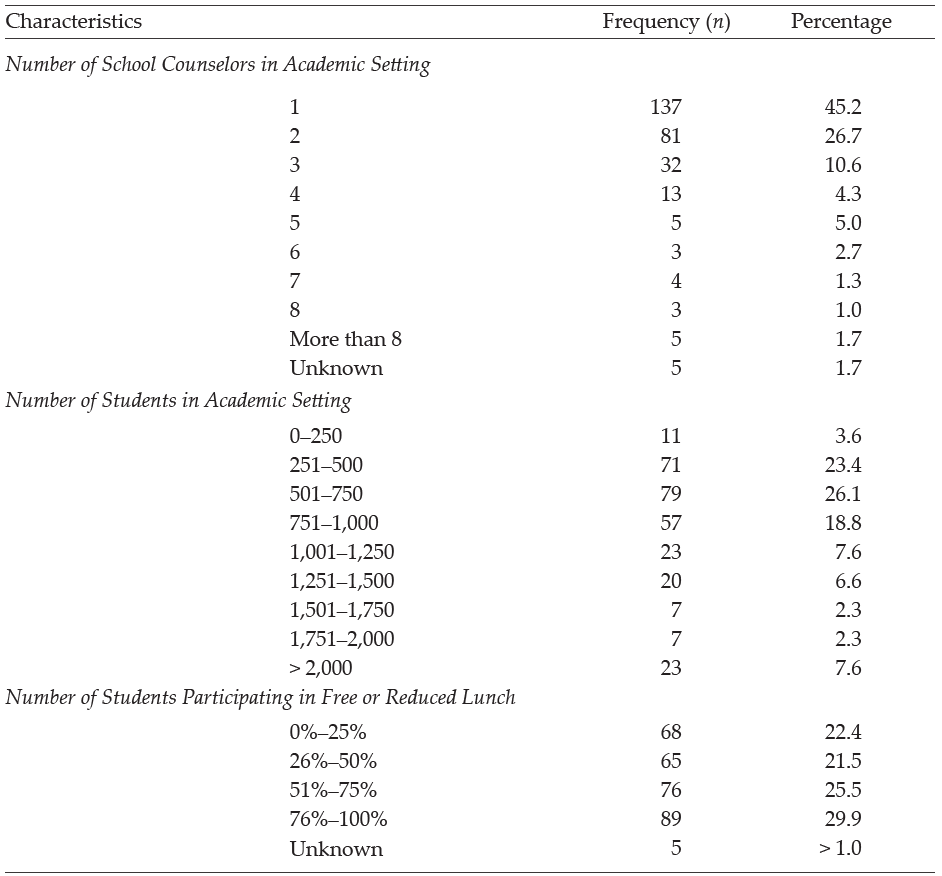

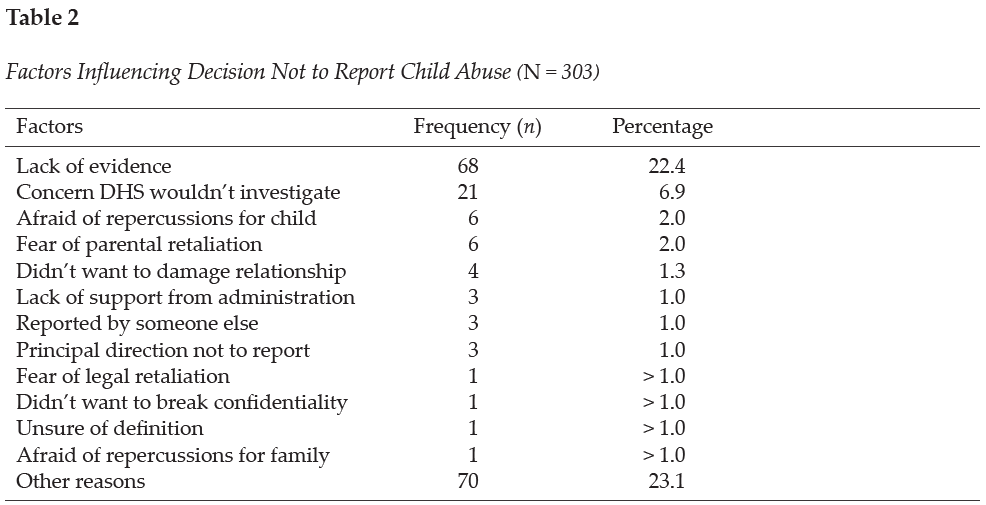

The Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire was developed to assess three domains, including school counselor General Information, Training in Child Abuse Reporting, and Child Abuse Reporting Experience (Bryant & Milsom, 2005). In the first section of the questionnaire, Training in Child Abuse Reporting, participants were asked to list where they obtained their knowledge of child abuse reporting and to assess four different types (physical, sexual, neglect, emotional) of child abuse. In the Child Abuse Reporting Experience section, the participants were asked two questions. The first question asked participants to recall the number of suspected child abuse cases they encountered during the preceding school year and the number of child abuse cases they reported. The next question asked participants how many cases of suspected child abuse they did not report. Participants were also asked in the survey to indicate reasons for choosing not to report suspected child abuse cases based on 12 commonly reported barriers or to list other reasons for not reporting the suspected cases. See Table 2 for a complete list of the common reasons given for not reporting suspected child abuse cases. Internal consistency measures were not obtained for this questionnaire because of the demographic nature of assessing participants’ personal experiences with child abuse reporting.

School Counselor Self-Efficacy Scale

The School Counselor Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSE) was used to assess school counselors’ self-efficacy and to link their personal attributes to their career performance (Bodenhorn & Skaggs, 2005). Participants completed Likert scale questions to indicate their confidence in performing school counseling tasks for 43 scale items. An example question would ask school counselors to indicate their confidence in advocating for integration of student academic, career, and personal development into the mission of their school. A rating of 1 indicated not confident and a rating of 5 indicated highly confident. The coefficient alpha for the scale score was found to be .95 (Bodenhorn & Skaggs, 2005). The SCSE subscales include five domains: Personal and Social Development (12 items), Leadership and Assessment (9 items), Career and Academic Development (7 items), Collaboration and Consultation (11 items), and Cultural Acceptance (4 items). The correlations of the subscales ranged from .27 to .43.

Knowledge of Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire

The Knowledge of Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire was developed to assess respondents’ knowledge of child abuse reporting and procedures within three areas (Ricks et al., 2019). To develop the survey, the researchers and outside counselor educators reviewed the questionnaire to determine if it clearly measured the constructs. In the first section of the questionnaire, Identifying Types of Abuse, participants’ perceptions of their ability to identify the four different types of child abuse were assessed. To complete this section, participants rated their comfort level using a 4-point Likert scale. A rating of 1 indicated very uncertain and a rating of 4 indicated very certain. The coefficient alpha for the scale score was found to be .902. The Knowledge of Guidelines section assessed participants’ knowledge of the state rules, ASCA Ethical Standards, and child abuse reporting protocol within their current school and district. To complete this section, participants rated their comfort level using a 5-point Likert scale. A rating of 1 indicated not knowledgeable and a rating of 5 indicated extremely knowledgeable. The coefficient alpha for the scale score was found to be .799. Lastly, the Child Abuse Training section assessed where participants received training on general knowledge of child abuse reporting, how to make a referral, and indicators of child abuse. To complete this section, participants selected options from a dropdown menu based on commonly reported agencies or listed an organization not provided. Options included in the survey list were universities or colleges, schools or districts, conferences or workshops, colleagues, journals, professional organizations, or the state department of education.

Data Analysis

SPSS Statistics 27 was used to analyze data within this study. First, a correlation analysis was executed to assess the strength of the relationship across variables. Next, analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to assess the relationship between the number of reported child abuse cases and five demographic variables, which included academic setting (elementary, middle, high); number of students participating in the school’s free or reduced lunch program; number of school counselors working in a school setting; years of experience as a school counselor; and number of students enrolled in a school setting. Lastly, regression analyses were used to determine the relationship between school counselors’ self-efficacy and their decisions to report or not report suspected child abuse cases as well as to assess the relationship between school counselors’ self-efficacy and their certainty in identifying types of abuse.

Results

Suspected and Reported Cases of Abuse

Descriptive statistics generated from the child abuse survey included the participants (N = 303) suspecting 2,289 cases of child abuse during the school year. Scores reported by participants ranged from 0 to 100 (M = 7.71, SD = 10.58). Seven participants omitted this question within the questionnaire. Participants indicated reporting a total of 2,140 cases of suspected child abuse; individual frequency ranged from 0 to 100 (M = 7.21, SD = 10.25). Physical child abuse cases (M = 4.03, SD = 7.12) were reported at a higher rate than cases of neglect (M = 2.72, SD = 5.10), emotional abuse (M = 0.56, SD = 1.52), and sexual abuse (M = 0.57, SD = 1.37).

School Demographics

The relationship between the number of reported child abuse cases and demographic variables was examined using a bivariate correlation. Results indicated a negative correlation between the number of child abuse reports and the academic level of students the school counselor works with (elementary, middle, or high school), r(293) = −.283, p < .001, with elementary school counselors reporting child abuse at a higher rate than high school counselors. An additional negative correlation was found between the number of child abuse reports and the number of school counselors working within the school, r(293) = −.164, p < .001. Results indicated a positive significant relationship between the number of reported child abuse cases and the number of students who participate in the school’s free or reduced lunch program, r(293) = .225, p < .001. Weaker negative relationships were also found between the number of child abuse reports and the participants’ years of experience as a school counselor, r(297) = −.115, p < .05, as well as how many students are enrolled in a school, r(293) = −.127, p < .06. No other significant relationships were found among the variables and reported cases.

An ANOVA was conducted to examine the relationship between the academic level of students (elementary, middle, and high) the participants worked with and the number of child abuse cases reported. Results showed a significant relationship among the variables, f(2, 290) = 13.021, p > .00. A follow-up test was used to evaluate pairwise differences among the means. Results of a Tukey HSD indicated a significant difference between elementary (M = 10.314) and high school (M = 3.58) counselors who reported child abuse. A difference was also found between elementary and middle school (M = 5.86) reporting levels. No other significant differences were found between variables.

An ANOVA was also conducted to evaluate the differences between child abuse reporting and the percentage (0%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75%, 76%–100%) of students who participated in free or reduced lunch. Results showed a significant relationship among the variables, f(3, 289) = 5.22, p = .002. A Tukey HSD post hoc test was used to make a pairwise comparison and statistically significant mean differences were found between the 0%–25% (M = 2.33) group and the 51%–75% (M = 7.78) group. Additionally, a difference was found between the 0%–25% group and the 76%–100% (M = 10.12) group. Lastly, a difference was found between the 26%–50% (M = 6.54) group and the 76%–100% group. No other significant differences were found between the groups.

An ANOVA was conducted to examine the relationship between how many school counselors are working in a school setting and the differences in child abuse reporting. Analysis of the ANOVA found no significant difference (p < .05) between the groups (one counselor, M = 8.26; two counselors, M = 7.81; three counselors, M = 7.69; four counselors, M = 5.00; five counselors, M = 2.80; six counselors, M = 2.25; seven counselors, M = 3.50; eight counselors, M = 2.33; more than eight counselors, M = 2.20), but a downward trend can be seen in the number of cases reported with the increase in the number of school counselors within a school.

Likewise, an ANOVA was used to examine the relationship between years of experience as a school counselor and the differences in child abuse reporting, but no significant difference (p < .05) was found between groups (6 to 10 years, M = 8.58; 11 to 20 years, M = 6.36; above 20 years, M = 5.57); however, a slight trend can be seen with participants who have less experience reporting at higher rates. A larger sample size may have yielded significant results, but additional research is needed in this area.

Lastly, an ANOVA was also executed to assess the differences in child abuse reporting and the number of students enrolled in a school setting. A significant difference was found between schools with more than 2,000 students (M = 3.00) and schools with 251–500 students (M = 8.07) as well as schools with 501–750 students (M = 8.63). This difference suggests school counselors who work in schools with more students tend to report child abuse at a lower rate than those who work in smaller schools. A downward trend can be seen in reporting of cases as student numbers increase (751–1,000 students, M = 7.62; 1,001–1,250 students, M = 7.39; 1,251–1,500 students, M = 6.68; 1,501–1,750 students, M = 6.00; 1,751–2,000 students, M = 2.57), with the exception of the 0–250 students (M = 4.82) school classification. Differences in the sample sizes of classification categories could have impacted significance outcomes. No other significant differences were found between the groups.

The Decision to Report

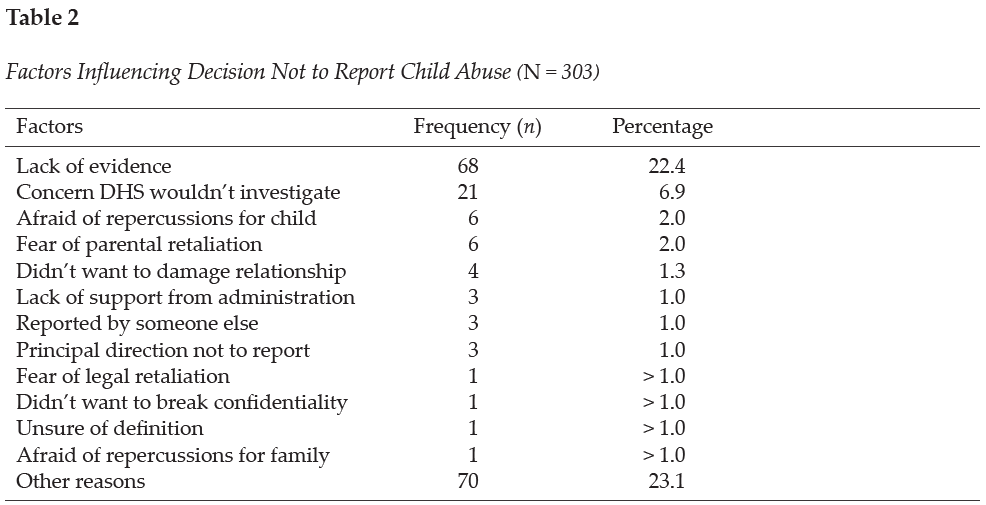

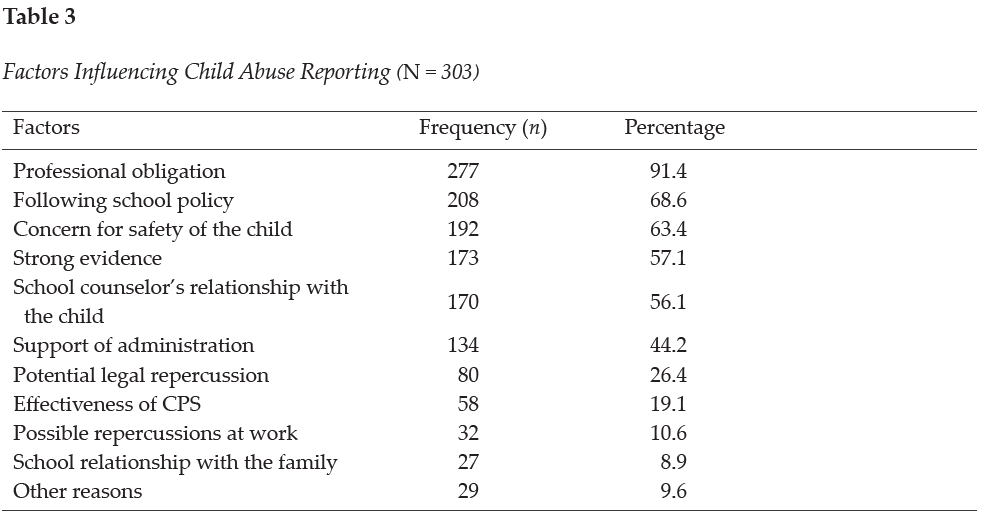

On the Child Abuse Reporting Survey, participants (N = 303) were asked to indicate what factors influenced their decision to report child abuse. Participants indicated the number one factor was following the law (professional obligation; 91.4%, n = 277). Other reasons cited by over half of school counselors included following school policy (68.6%, n = 208), concern for safety of the child (63.4%, n = 192), strong evidence that abuse had occurred (57.1%, n = 173), and the school counselor’s relationship with the child (56.1%, n = 173). See Table 3 for factors influencing child abuse reporting. Further, participants indicated reasons why they chose not to report suspected child abuse. Participants specified inadequate evidence as the primary reason for not reporting suspected child abuse (22.4%, n = 68). Another notable influence included concern that DHS would not investigate the reported case (6.9%, n = 21). See Table 2 for factors influencing the decision not to report child abuse.

Knowledge and Training

On the Knowledge of Child Abuse Reporting Questionnaire, participants were asked to rate how certain they feel about their abilities to identify types of abuse on a 4-point Likert scale with 1 indicating very uncertain and 4 indicating very certain. Participants reported most confidence in their ability to identify physical abuse (M = 3.49, Mdn = 4), followed by neglect (M = 3.30, Mdn = 3), sexual abuse (M = 3.20, Mdn = 3), and emotional abuse (M = 3.06, Mdn = 3). When participants (N = 303) were asked where they gained knowledge about child abuse, most reported receiving training from professional experiences (88.4%, n = 268), mandated reporting training at school (79.5%, n = 241), workshops (72.3%, n = 219), discussion with colleagues (61.4%, n = 186), or literature (58.1%, n = 176). Additionally, participants indicated gaining knowledge from university courses (46.5%, n = 141), media (9.2%, n = 28), or other avenues unlisted in the survey (12.2%, n = 37).

Participants were asked where they received training on how to make a referral for a child abuse case. Most of the school counselors responded that they received the training from a school/district training (87.5%, n = 265), conference/workshop (57.4%, n = 174), or university class (42.9%, n = 130). Other responses included from a colleague (38.9%, n = 118), professional organization (32.7%, n = 99), Department of Education website (20.5%, n = 62), journal (10.9%, n = 33), or other sources (11.2%, n = 34). Lastly, veteran counselors were asked where they received training about the indicators of child abuse. The majority of the respondents reported learning in a school/district training (87.1%, n = 264), conference/workshop (77.9%, n = 236), or university/college course (67.3%, n = 204). Other responses included learning from a professional organization (38%, n = 115), colleague (30%, n = 91), journal (23.4%, n = 71), Department of Education website (21.5%, n = 65), or other sources (9.9%, n = 30).

Veteran school counselors reported that 88.1% (n = 267) of schools/districts provided them with training on local abuse reporting policies. Therefore, 11.9% did not receive training from their local school system. Additionally, 60.1% (n = 182) of the school counselors reported their school/district had a handbook/resource outlining the steps for mandated reporter training within their school system. Consequently, 39.9% of the school counselors reported not having a handbook/resource to reference outlining steps for mandated reporting.

Self-Efficacy and Child Abuse Reporting

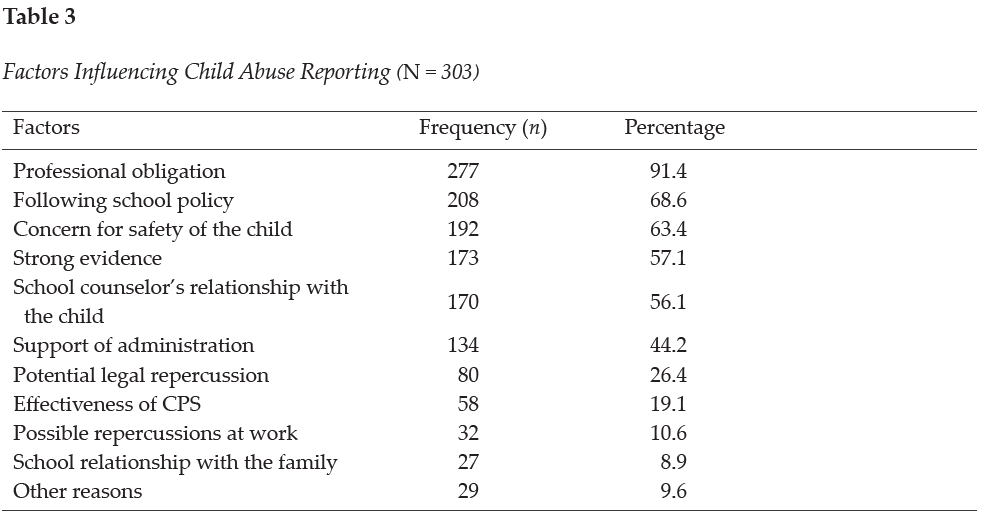

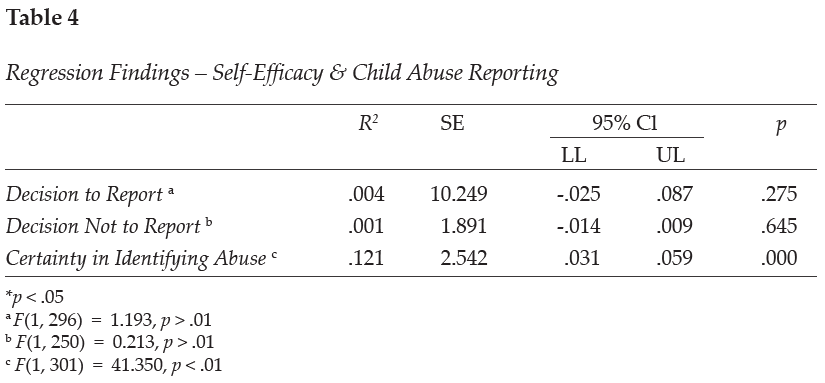

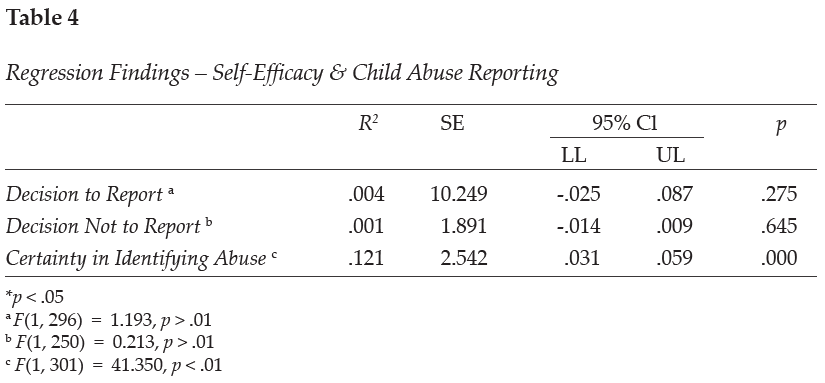

A regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between veteran school counselors’ self-efficacy and three variables, including the number of reported child abuse cases, the decision not to report suspicion of child abuse, and certainty in identifying types of child abuse. Results showed the strength of the relationship between self-efficacy and certainty in identifying types of child abuse was moderately related, F(1, 301) = 41.350, p < .01. Over 12% (r2 = 0.121) of the variance of the school counselors’ self-efficacy level was associated with certainty in identifying child abuse. No other significant results were found among the variables. See Table 4 for the regression analysis related to self-efficacy and child abuse reporting.

Discussion

Given the well-documented negative impact of child abuse on the emotional, physical, and academic well-being of children, it is essential to understand how school counselors are trained to identify and report child abuse. Understanding trends and research in child abuse reporting can help schools prepare school counselors and other staff members. It is imperative for veteran school counselors to receive ongoing training to best serve as advocates for students, maintain relevancy in their roles as mandated reporters by staying current on laws and policies, and further their ability to work within their scope of practice. Ongoing training may also help alleviate difficulties that arise because of terminology differing from state to state and district to district (ASCA, 2021; Hogelin, 2013; Lambie, 2005; Tuttle et al., 2019).

In this study, veteran school counselors’ reporting frequency is shown to differ based on various school demographics. Veteran school counselors were specifically targeted in this analysis to examine their experiences related to child abuse reporting. Although these findings may not show direct causation to child abuse reporting among veteran school counselors, they can help us better understand school and school counselor demographics that need to be evaluated further. The findings can also be used to guide professional development training needed for school counselors as well as additional training needs for counselors-in-training.

Elementary school counselors were found to report child abuse at a higher rate than middle or high school counselors; however, this is anticipated because studies show that younger children experience higher rates of maltreatment than older children (HHS et al., 2021). In fact, rates of maltreatment seem to decrease as age increases. Children who are 6 years old have victimization rates of 9.0 per 1,000 children compared to children who are 16 years of age who have a victimization rate of 5.5 per 1,000 children (HHS et al., 2021). Higher maltreatment levels in younger children may be because of increased caregiver burden (Fortson et al., 2016); as children get older, they are better able to care for themselves and avoid parental confrontation. In addition, older students may be more likely to hide abuse and more astute when dealing with disclosure protocol (Bryant & Milsom, 2005). Knowledge of the signs and symptoms of child abuse and neglect can help school counselors identify children suffering from maltreatment.

Within this study on veteran school counselors, a slight trend can be seen with participants with less experience reporting suspected child abuse at a higher rate. Differences of reporting rates by years of experience may be because of higher ego maturity in less experienced school counselors because of more recent training in their graduate programs (Lambie et al., 2011). According to Lambie et al. (2011), ego development predicts an individual’s level of ethical and legal knowledge, which has been found to be higher in counselors-in-training than the average school counselor. Ego development has also been correlated with greater degrees of self-efficacy (Singleton et al., 2021), which can impact school counselors’ actions when making decisions related to child abuse reporting. Tuttle et al. (2019) also emphasized the need for continuous training to increase school counselors’ self-efficacy as mandated reporters, although more research is needed to understand the impact of self-efficacy on school counselor action. These findings highlight the need for continued assessment of training needs for school counselors of various experience levels.

Although age has been associated with varying levels of child abuse victimization, low socioeconomic status within the home environment has also been identified as a high risk factor for child abuse (Bryant, 2009; Bryant & Milsom, 2005; Ricks et al., 2019; Sedlak et al., 2010). Specifically, the higher the percentage of students participating in the school’s free or reduced lunch program, the more child abuse cases the school counselor reported (Bryant, 2009; Bryant & Milsom, 2005; Ricks et al., 2019). Although most children in low-income families do not experience child abuse, one study estimated that 22.5 children per 1,000 in low-income families experience maltreatment as compared to 4.4 per 1,000 in more affluent families (Sedlak et al., 2010). However, it is important to note the disproportionality that exists within child welfare reporting; non-White children and children of low socioeconomic status are reported to child protective services at a higher rate than their peers (Krase, 2015; Luken et al., 2021). School counselors working in low-income schools need to be aware of the increased risk factors of low socioeconomic status as well as the racial and economic disproportionality that occurs within child maltreatment reporting as a result of possible bias. School counselors should work to be aware of potential biases they may hold with regard to over-reporting certain groups of children and under-reporting others (Tillman et al., 2015).

When examining the current practices of veteran school counselors, participants reported professional obligation as the number one reason they reported suspected child abuse. The primary reason given for failing to report suspected abuse was inadequate evidence. These findings are similar to prior research that shows lack of evidence as an influencing factor in school counselors’ decisions not to report suspected abuse (Bryant, 2009; Bryant & Milsom, 2005; Tillman et al., 2015); this is concerning because some cases of abuse may go unreported. As Tuttle et al. (2019) have stated, “the school counselor’s responsibility is to follow legal and ethical obligations as a mandated reporter by reporting all suspected child abuse” (p. 242). Although concern that DHS would not investigate is denoted as an important factor for why school counselors choose not to report, school counselors must recognize they do not have the proper resources or training to lead a child abuse investigation on their own (Tuttle et al., 2019). As a result, school counselors are ethically and legally mandated to report all suspected cases of abuse to the proper authorities defined by their state, school policies, and ethical codes. Failure to report cases could lead to legal ramifications for the school counselor (Remley et al., 2017; White & Flynt, 2000) and continued maltreatment for the student.

School counselors should strive to “understand child abuse and neglect and its impact on children’s social/emotional, physical and mental well-being” (ASCA, 2021, para. 6). Veteran school counselors completing this survey were most confident in their ability to identify physical abuse and less confident in their ability to identify emotional abuse. This finding supports the assertion that types of abuse with visible evidence are more identifiable than other types of abuse such as emotional or sexual abuse (Bryant, 2009; Bryant & Milsom, 2005). Cases of suspected abuse in which a child reports physical abuse are less likely to be reported if there is no evidence of bodily harm (Tillman et al., 2015). Although school counselors report physical abuse as the most easily identifiable type of abuse, child protective services report neglect as the most common type of maltreatment (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2021).

Results from this study show that veteran school counselors reported receiving their knowledge on child abuse from professional experiences and mandated reporter training at their school; comparatively, early career school counselors reported most of their knowledge came from professional experience and university courses (Ricks et al., 2019). Reported differences were also observed between veteran school counselors and early career school counselors in terms of sources of knowledge on how to make a referral and learn about indicators of abuse (Ricks et al., 2019). Differences may exist because of variable school district policies regarding ongoing mandated reporter training frequency and practices.

When assessing training needs, participants indicated that most veteran school counselors do receive training from their school district on how to make a referral, indicators of child abuse, and local abuse reporting procedures. In fact, 25% more veteran school counselors reported receiving training from their district than early career school counselors (Ricks et al., 2019). Additionally, approximately 40% of veteran school counselors reported not having a handbook or resource to reference outlining the mandated reporting protocol for their district/school. This result is slightly lower than that reported in research on early career school counselors showing approximately half of school counselors not having a handbook/resource (Ricks et al., 2019). The lack of access to a set protocol outlined by the district is concerning because of the inconsistencies that exist within protocols across states and school districts. Confusion may arise as to timeliness and manner of reporting as well as to who must make the actual report (Kenny & McEachern, 2002). As compared to novice school counselors, veteran counselors appear to report receiving training and/or a handbook/resources related to child abuse reporting in higher numbers. Discrepancies in reported training may indicate a delay in training provided to new school counselors or that training on child abuse is not occurring annually. Although the majority of veteran school counselors did report receiving some training from their school districts, it is important to have “established protocols [to] help address concerns over quality control, fear of lawsuits, and the protection of staff in reporting cases, as well as ensure that there are effective steps for helping children” (Crosson-Tower, 2003, p. 29).

Previous research (Kenny & McEachern, 2002) has indicated that school counselors with more years of experience report less adequate pre-service training in child abuse reporting and that school counselors with in-service training in the last 12 months are less concerned about the consequences of making a report (Behun et al., 2019). This might be due to recently trained school counselors having greater awareness about current information and procedures, which supports the need for participation in continuous ongoing education on this topic. Although the veteran school counselors surveyed in this study indicated experience in child abuse reporting, continued updates to the law highlight the need for current and well-defined guidelines within each school system. Ongoing training is recommended for all school counselors to ensure they stay informed on updated protocols and research (Kenny & Abreu, 2016; Tuttle et al., 2019).

Results of the data analysis also indicated a moderately significant relationship between veteran school counselor self-efficacy and their certainty identifying types of abuse. These findings echo other research indicating that school counselors’ self-efficacy levels may influence their decisions to report suspected abuse (Ricks et al., 2019; Tuttle et al., 2019). According to Larson and Daniels (1998), counselor self-efficacy beliefs are the main factor contributing to effective counseling action. Given the impact of counselor self-efficacy on effective action, it is important to understand how self-efficacy impacts school counselors’ decision-making processes. Experience and training are two factors that have been found to increase school counselor self-efficacy (Morrison & Lent, 2018). Veteran school counselors, who already have years of experience on their side, may benefit most from additional training opportunities. Increased support should be provided to all school counselors to enhance their counseling self-efficacy (Schiele et al., 2014) and contribute to positive school counseling outcomes.

Implications

Lack of knowledge related to reporting policies has been identified as a key barrier in reporting child abuse (Kenny, 2001; Petersen et al., 2014). School counselors should advocate for standardization in reporting policies. Understanding each state’s unique child abuse prevention statutes can help school counselors best serve their clients (Remley et al., 2017). Given that laws and definitions pertaining to child abuse and neglect vary among states (ASCA, 2021), school counselors should identify collaborative relationships to navigate these legal and ethical parameters. Key collaborations may include those with the school social worker, the school district’s attorney, law enforcement, child protective services, parents/guardians, and community members (Tuttle et al., 2019). Working together, in conjunction with administration and other school stakeholders, school counselors can help establish or update written guidelines and implement ongoing professional development in mandated reporting within their school district. Additionally, developing a positive working relationship with law enforcement and child protective services can help ensure that child abuse cases are reported and documented properly, which can promote positive outcomes for students and families. Moreover, based on the findings from this research study, school counseling certification organizations (i.e., state departments of education/licensure boards) may want to increase or update current training policies for professional school counselors. An area for further study would be examining school districts’ training and protocols for child abuse reporting.

Higher reporting trends in low socioeconomic settings highlight the need for additional mental health services in low-income school districts. School counselors may need more training on the risk factors associated with poverty as well as to be reminded that abuse occurs in all types of families (Bryant, 2009; Tillman et al., 2015). Practicing school counselors working with students living in poverty are often in schools where there are significantly limited resources. School counselors report that “working in schools with high poverty means academic services and the school counseling program itself are limited” (Ricks et al., 2020, p. 61). More research is needed to assess how to support school counselors working in low-income schools; however, school counselors should remain cognizant and demonstrate cultural competency. It is also important for veteran school counselors to continue to assess self-bias as a factor in identifying and reporting suspected child abuse cases (Tillman et al., 2015). Further, it is essential that school counselors emerge as advocates for students in these low socioeconomic settings by pushing for more resources for mental health services as well as changes to policies that negatively impact students’ success. School counselors can work with a task force or advisory committee within the school to examine current practices on child abuse identification and reporting (Temkin et al., 2020). The task force could look for systemic barriers that are impacting students related to child abuse reporting and trauma support; these include current school policies, reporting procedures, teacher and staff training protocols, school counselor professional development, access to mental health services, community resources, direct and indirect school counseling protocols, and other factors impacting student identification and support.

Given the higher number of child abuse cases in the elementary grade levels, more school counselors are needed to adequately identify child abuse and provide services for these students. Despite these needs, the school counselor-to-student ratio varies in each state and is higher in elementary schools (ASCA, 2022b); the national state averages for the school counselor-to-student ratio in grades kindergarten through eighth ranges from 1:419 to 1:1,135 as compared to 1:164 to 1:347 in grades nine through 12 (ASCA, 2022b). Moreover, 20 states currently have no school counseling mandates that require school counselors to be present within the schools (ASCA, 2022c). Of the 30 states that do have mandated counseling, seven do not have mandated counseling for elementary-level students (ASCA, 2022c). School counselors should advocate for more school counselors within their districts and state. Moreover, school administrations and state departments of education should consider hiring additional school counselors to address ongoing mental health needs. Recent research has shown that as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, students may be experiencing no motivation to do schoolwork, difficulty concentrating, concern for falling behind in school, concern for getting sick, or other stress-related factors (Styck et al., 2021), as well as an increased risk for child abuse and neglect (Swedo et al., 2020). Elementary school counselors, who are uniquely trained in child development, can implement prevention and intervention programs to address these ongoing needs (ASCA, 2019). Elementary school counselors are essential in providing early intervention and prevention services for students.

Further research is needed in understanding how self-efficacy impacts school counselors’ decision-making process. The variation of confidence in identifying abuse as well as variance in reporting patterns among school counselors with differing years of experience are indicators that further professional development and training is needed within schools. It is also important to examine how school support can increase school counselors’ self-efficacy levels (Schiele et al., 2014). Current research shows that a school counselor’s level of self-efficacy predicts quality of practice and knowledge of evidence-based practices (Schiele et al., 2014).

Limitations

Although measures were used to reduce confounding variables, limitations exist in the methodological design of the study that could impact the validity of the findings. Firstly, this study obtained a sample size from a limited geographic area (Southeastern United States). Secondly, self-reported data was used. Although participants were informed their answers would remain anonymous, they may have answered based on what they perceived as acceptable and appropriate. School counselors may not be inclined to admit they did not report suspected child abuse for fear of legal or ethical violations. Likewise, selective memory may impact participants’ ability to effectively recall events that happened over a year ago. Additionally, many of the participants were White; responses from participants of color were limited. Further research with a more diverse sample would be beneficial to gain a comprehensive understanding of school counselors’ self-efficacy in identifying and reporting child abuse.

Conclusion

School counselors are mandated to report suspected child abuse and neglect cases to authorities and are key school personnel in early detection and recognition of abuse (ASCA, 2021). In this study, differing school demographics were associated with varying reporting practices among veteran school counselors. Continued professional development training, by virtue of its ability to increase veteran school counselors’ self-efficacy and knowledge of identification and reporting protocols, represents a promising possible pathway to improving outcomes among maltreated children.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2017). The school counselor and academic development. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Academic-Development

American School Counselor Association. (2019). The essential role of elementary school counselors. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/1691fcb1-2dbf-49fc-9629-278610aedeaa/Why-Elem.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2021). The school counselor and child abuse and neglect prevention. https://schoolcounselor.org/Standards-Positions/Position-Statements/ASCA-Position-Statements/The-School-Counselor-and-Child-Abuse-and-Neglect-P

American School Counselor Association. (2022a). ASCA ethical standards for school counselors. https://www.school

counselor.org/About-School-Counseling/Ethical-Legal-Responsibilities/ASCA-Ethical-Standards-for-School-Counselors-(1)

American School Counselor Association. (2022b). School counselor roles & ratios. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/About-School-Counseling/School-Counselor-Roles-Ratios

American School Counselor Association. (2022c). State school counseling mandates & legislation. https://www.school

counselor.org/About-School-Counseling/State-Requirements-Programs/State-School-Counseling-Man

dates-Legislation

Balkaran, S. (2015). Impact of child abuse education on parent’s self-efficacy: An experimental study. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies, 1432.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2),

191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Barrett, K. M., Lester, S. V., & Durham, J. C. (2011). Child maltreatment and the advocacy role of professional school counselors. Journal for Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, 3(2), 86–103.

https://doi.org/10.33043/JSACP.3.2.86-103

Behun, R. J., Cerrito, J. A., Delmonico, D. L., & Kolbert, J. B. (2019). The influence of personal and professional characteristics on school counselors’ recognition and reporting of child sexual abuse. Journal of School Counseling, 17(13), 1–34.

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Hardcastle, K. A., Perkins, C., & Lowey, H. (2015). Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: A national survey. Journal of Public Health, 37(3), 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdu065

Bodenhorn, N., & Skaggs, G. (2005). Development of the school counselor self-efficacy scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 38(1), 14–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2005.11909766

Bryant, J. K. (2009). School counselors and child abuse reporting: A national survey. Professional School Counseling, 12(5), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0901200501

Bryant, J., & Milsom, A. (2005). Child abuse reporting by school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 9(1), 63–71.

Buchanan, D. K., Mynatt, B. S., & Woodside, M. (2017). Novice school counselors’ experience in classroom management. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.7729/91.1146

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/long_term_consequences.pdf

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2021). Child maltreatment 2019: Summary of key findings. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/canstats

Collin-Vézina, D., Brend, D., & Beeman, I. (2020). When it counts the most: Trauma-informed care and the

COVID-19 global pandemic. Developmental Child Welfare, 2(3), 172–179.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2516103220942530

Crosson-Tower, C. (2003). The role of educators in preventing and responding to child abuse and neglect. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, Office on Child Abuse and Neglect. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/educator.pdf

Fortson, B. L., Klevens, J., Merrick, M. T., Gilbert, L. K., & Alexander, S. P. (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/can-prevention-technical-package.pdf

Heim, C., Shugart, M., Craighead, W. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2010). Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(7), 671–690. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20494

Hodges, L. I., & McDonald, K. (2019). An organized approach: Reporting child abuse. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory, & Research, 46(1–2), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2019.1673093

Hogelin, J. M. (2013). To prevent and to protect: The reporting of child abuse by educators. Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal, 2013(2), 225–252. https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj/vol2013/iss2/3

Hupe, T. M., & Stevenson, M. C. (2019). Teachers’ intentions to report suspected child abuse: The influence of compassion fatigue. Journal of Child Custody, 16(4), 364–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/15379418.2019.1663334

Johnson, G., Nelson, J., & Henriksen, R. (2017). Mentoring novice school counselors: A grounded theory. In G. R. Walz & J. Bleuer (Eds.), Ideas and research you can use: VISTAS 2017 (pp. 1–16). Counseling Outfitters.

Jordan, K. S., MacKay, P., & Woods, S. J. (2017). Child maltreatment: Optimizing recognition and reporting by school nurses. NASN School Nurse, 32(3), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942602X16675932

Kenny, M. C. (2001). Child abuse reporting: Teachers’ perceived deterrents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 25(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145(00)00218-0

Kenny, M. C, & Abreu, R. L. (2016). Mandatory reporting of child maltreatment for counselors: An innovative training program. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 2(2), 112–124.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2016.1228770

Kenny, M. C., & McEachern, A. G. (2002). Reporting suspected child abuse: A pilot comparison of middle and high school counselors and principals. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 11(2), 59–75.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v11n02_04

Klassen, S. L., & Hickman, D. L. (2022). Reporting child abuse and neglect on K-12 campuses. In A. M. Powell (Ed.), Best practices for trauma-informed school counseling. IGI Global.

https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-9785-9.ch010

Krase, K. S. (2015). Child maltreatment reporting by educational personnel: Implications for racial disproportionality in the child welfare system. Children & Schools, 37(2), 89–99.

https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdv005

Lambie, G. W. (2005). Child abuse and neglect: A practical guide for professional school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 8(3), 249–258. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42732466

Lambie, G. W., Ieva, K. P., Mullen, P. R., & Hayes, B. G. (2011). Ego development, ethical decision-making, and legal and ethical knowledge in school counselors. Journal of Adult Development, 18(1), 50–59.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-010-9105-8

Larson, L. M., & Daniels, J. A. (1998). Review of the counseling self-efficacy literature. The Counseling Psychologist, 26(2), 179–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000098262001

Luken, A., Nair, R., & Fix, R. L. (2021). On racial disparities in child abuse reports: Exploratory mapping the 2018 NCANDS. Child Maltreatment, 26(3), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211001926

McGuire, K., & London, K. (2020). A retrospective approach to examining child abuse disclosure. Child Abuse and Neglect, 99, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104263

Mishak, D. A. (2007). An investigation of early career and veteran Iowa elementary school counselors and their classroom guidance programs (Order No. 3265967). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304858653).

Morrison, M. A., & Lent, R. W. (2018). The working alliance, beliefs about the supervisor, and counseling self-efficacy: Applying the relational efficacy model to counselor supervision. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(4), 512–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000267

Petersen, A. C., Joseph, J., & Feit, M. (Eds.). (2014). New directions in child abuse and neglect research. The National Academies Press.

Remley, T. P., Jr., Rock, D. W., & Reed, R. M. (2017). Ethical and legal issues in school counseling (4th ed.). American School Counselor Association.

Ricks, L., Carney, J., & Lanier, B. (2020). Attributes, attitudes, and perceived self-efficacy levels of school counselors toward poverty. Georgia School Counselors Association Journal, 27, 51–68.

Ricks, L., Tuttle, M., Land, C., & Chibbaro, J. (2019). Trends and influential factors in child abuse reporting: Implications for early career school counselors. Journal of School Counseling, 17(16). http://www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v17n16.pdf

Schiele, B. E., Weist, M. D., Youngstrom, E. A., Stephan, S. H., & Lever, N. A. (2014). Counseling self-efficacy, quality of services and knowledge of evidence-based practices in school mental health. The Professional Counselor, 4(5), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.15241/bes.4.5.467

Sedlak, A. J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Petta, I., McPherson, K., Greene, A., & Li, S. (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4): Report to Congress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/nis4_report_congress_full_pdf_jan2010.pdf

Singleton, O., Newlon, M., Fossas, A., Sharma, B., Cook-Greuter, S. R., & Lazar, S. W. (2021). Brain structure and functional connectivity correlate with psychosocial development in contemplative practitioners and controls. Brain Sciences, 11(6), 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060728

Styck, K. M., Malecki, C. K., Ogg, J., & Demaray, M. K. (2021). Measuring COVID-19-related stress among 4th through 12th grade students. School Psychology Review, 50(4), 530–545.

https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1857658

Swedo, E., Idaikkadar, N., Lemmis, R., Dias, T., Radhakrishnan, L., Stein, Z., Chen, M., Agathis, N., & Holland, K. (2020). Trends in U.S. emergency department visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect among children and adolescents aged <18 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–September 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(49), 1841–1847. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6949al

Tang, A. (2020). The impact of school counseling supervision on practicing school counselors’ self-efficacy in building a comprehensive school counseling program. Professional School Counseling, 23(1).

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20947723

Temkin, D., Harper, K., Stratford, B., Sacks, V., Rodriguez, Y., & Bartlett, J. D. (2020). Moving policy toward a whole school, whole community, whole child approach to support children who have experienced trauma. The Journal of School Health, 90(12), 940–947. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12957

Tillman, K. S., Prazak, M. D., Burrier, L., Miller, S., Benezra, M., & Lynch, L. (2015). Factors influencing school counselors’ suspecting and reporting of childhood physical abuse: Investigating child, parent, school, and abuse characteristics. Professional School Counseling, 19(1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.103

Tuttle, M., Ricks, L., & Taylor, M. (2019). A child abuse reporting framework for early career school counselors. The Professional Counselor, 9(3), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.15241/mt.9.3.238

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2021). Child maltreatment 2019. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/cm2019.pdf

White, J., & Flynt, M. (2000). The school counselor’s role in prevention and remediation of child abuse. In J. Wittmer (Ed.), Managing your school counseling program: K-12 developmental strategies (pp. 149–160). Educational Media.

Lacey Ricks, PhD, NCC, NCSC, is an associate professor at Liberty University. Malti Tuttle, PhD, NCC, NCSC, LPC, is an associate professor at Auburn University. Sara E. Ellison, MS, NCC, LAPC, is a doctoral student at Auburn University. Correspondence may be addressed to Lacey Ricks, 1971 University Blvd, Lynchburg, VA 24515, lricks1@liberty.edu.

Aug 20, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 3

Alison M. Boughn, Daniel A. DeCino

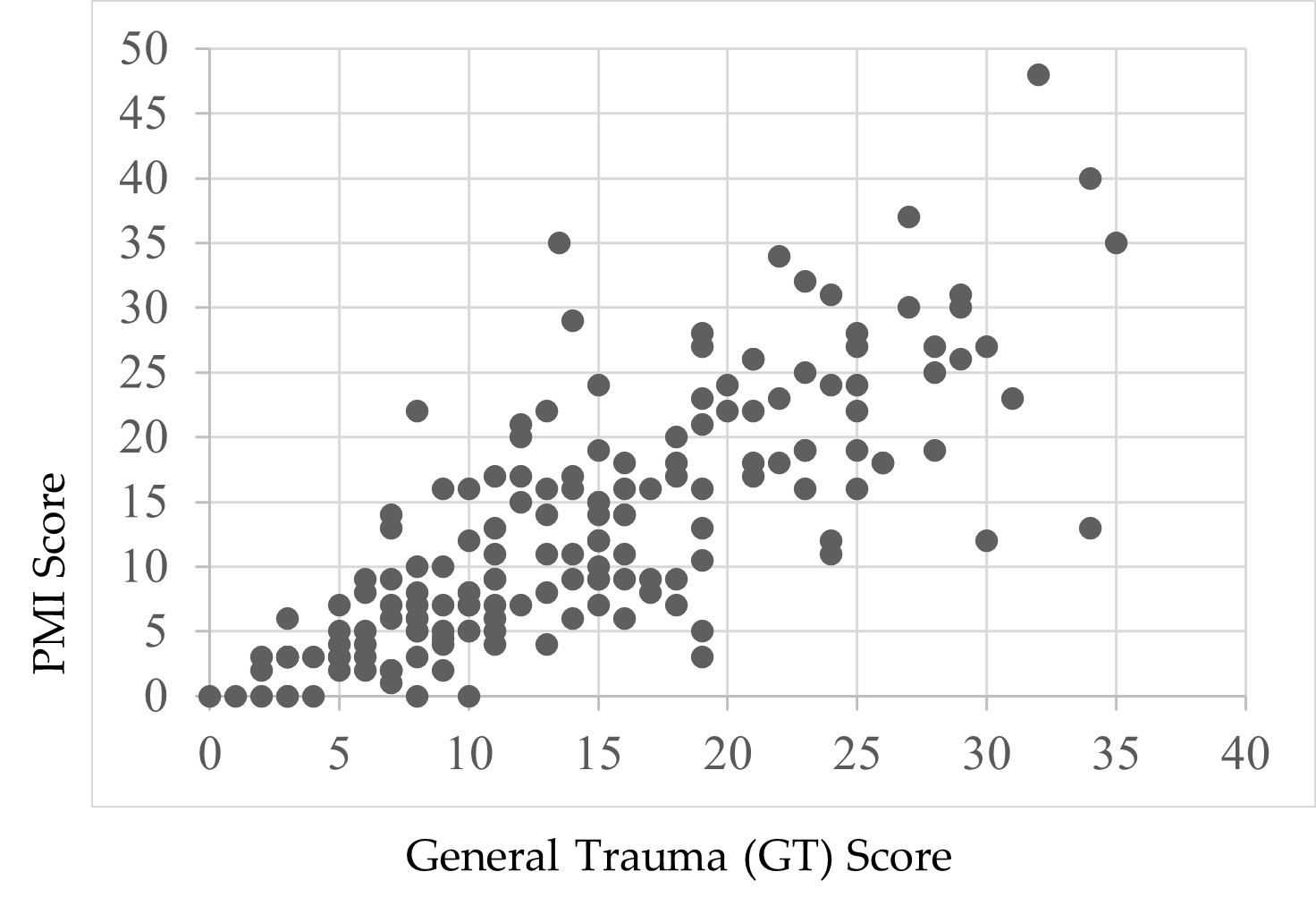

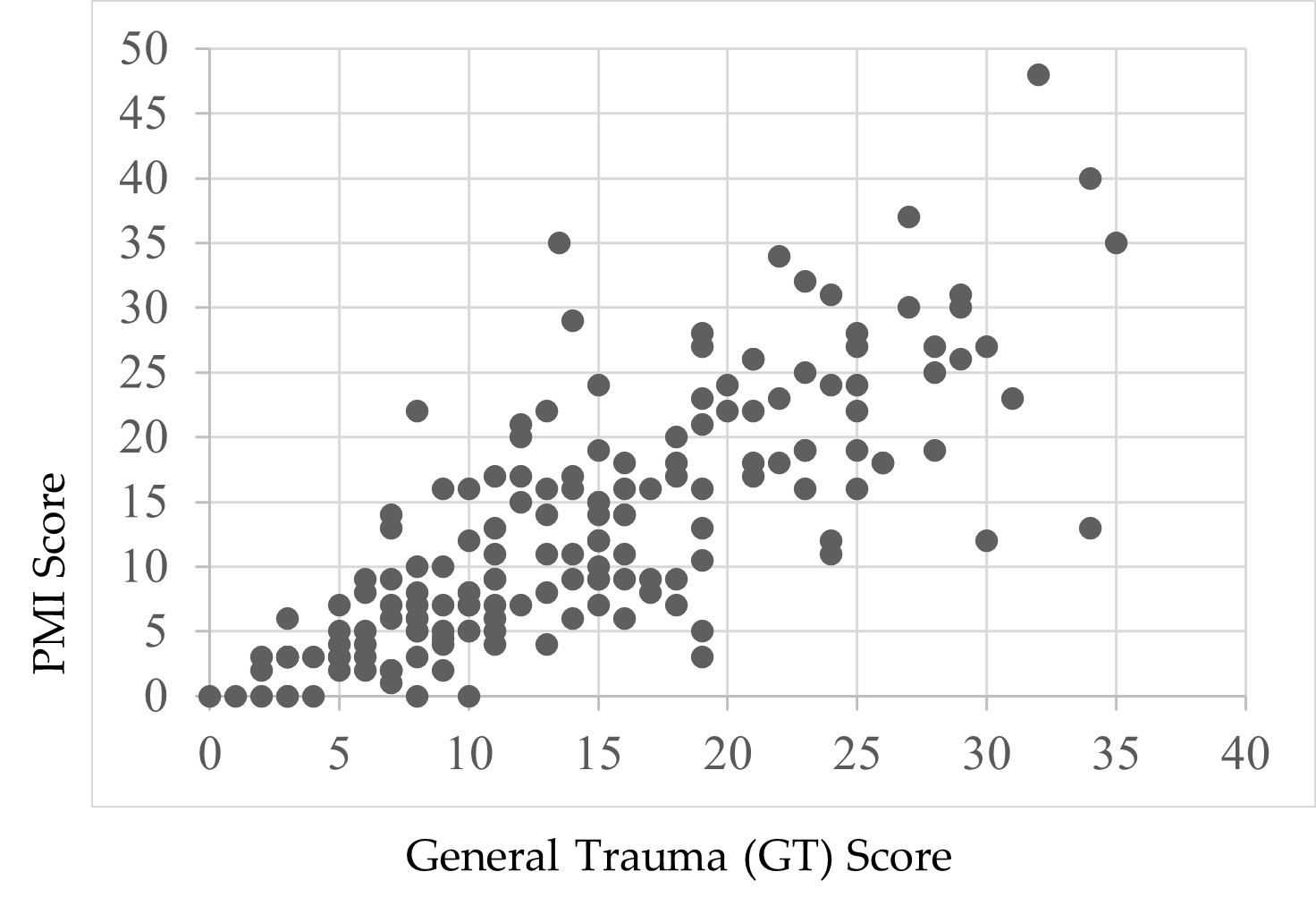

This article introduces the development and implementation of the Psychological Maltreatment Inventory (PMI) assessment with child respondents receiving services because of an open child abuse and/or neglect case in the Midwest (N = 166). Sixteen items were selected based on the literature, subject matter expert refinement, and readability assessments. Results indicate the PMI has high reliability (α = .91). There was no evidence the PMI total score was influenced by demographic characteristics. A positive relationship was discovered between PMI scores and general trauma symptom scores on the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children Screening Form (TSCC-SF; r = .78, p = .01). Evidence from this study demonstrates the need to refine the PMI for continued use with children. Implications for future research include identification of psychological maltreatment in isolation, further testing and refinement of the PMI, and exploring the potential relationship between psychological maltreatment and suicidal ideation.

Keywords: psychological maltreatment, child abuse, neglect, assessment, trauma

In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC; 2012) reported that the total cost of child maltreatment (CM) in 2008, including psychological maltreatment (PM), was $124 billion. Fang et al. (2012) estimated the lifetime burden of CM in 2008 was as high as $585 billion. The CDC (2012) characterized CM as rivaling “other high profile public health problems” (para. 1). By 2015, the National Institutes of Health reported the total cost of CM, based on substantiated incidents, was reported to be $428 billion, a 345% increase in just 7 years; the true cost was predictably much higher (Peterson et al., 2018). Using the sensitivity analysis done by Fang et al. (2012), the lifetime burden of CM in 2015 may have been as high as $2 trillion. If these trends continue unabated, the United States could expect a total cost for CM, including PM, of $5.1 trillion by 2030, with a total lifetime cost of $24 trillion. More concerning, this increase would not account for any impact from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mental health first responders and child protection professionals may encounter PM regularly in their careers (Klika & Conte, 2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2018). PM experiences are defined as inappropriate emotional and psychological acts (e.g., excessive yelling, threatening language or behavior) and/or lack of appropriate acts (e.g., saying I love you) used by perpetrators of abuse and neglect to gain organizational control of their victims (American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children [APSAC], 2019; Klika & Conte, 2017; Slep et al., 2015). Victims may experience negative societal perceptions (i.e., stigma), fear of retribution from caregivers or guardians, or misdiagnosis by professional helpers (Iwaniec, 2006; López et al., 2015). They often face adverse consequences that last their entire lifetime (Spinazzola et al., 2014; Tyrka et al., 2013; Vachon et al., 2015; van der Kolk, 2014; van Harmelen et al., 2010; Zimmerman & Mercy, 2010). PM can be difficult to identify because it leaves no readily visible trace of injury (e.g., bruises, cuts, or broken bones), making it complicated to substantiate that a crime has occurred (Ahern et al., 2014; López et al., 2015). Retrospective data outlines evaluation processes for PM identification in adulthood; however, childhood PM lacks a single definition and remains difficult to assess (Tonmyr et al., 2011). These complexities in identifying PM in children may prevent mental health professionals from intervening early, providing crucial care, and referring victims for psychological health services (Marshall, 2012; Spinazzola et al., 2014). The Psychological Maltreatment Inventory (PMI) is the first instrument of its kind to address these deficits.

Child Psychological Maltreatment

Although broadly conceptualized, child PM experiences are described as literal acts, events, or experiences that create current or future symptoms that can affect a victim without immediate physical evidence (López et al., 2015). Others have extended child PM to include continued patterns of severe events that impede a child from securing basic psychological needs and convey to the child that they are worthless, flawed, or unwanted (APSAC, 2019). Unfortunately, these broad concepts lack the specificity to guide legal and mental health interventions (Ahern et al., 2014). Furthermore, legal definitions of child PM vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and state to state (Spinazzola et al., 2014). The lack of consistent definitions and quantifiable measures of child PM may create barriers for prosecutors and other helping professionals within the legal system as well as a limited understanding of PM in evidence-based research (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; APSAC, 2019; Klika & Conte, 2017). These challenges are exacerbated by comorbidity with other forms of maltreatment.

Co-Occurring Forms of Maltreatment

According to DHHS (2018), child PM is rarely documented as occurring in isolation compared to other forms of maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect). Rather, researchers have found PM typically coexists with other forms of maltreatment (DHHS, 2018; Iwaniec, 2006; Marshall, 2012). Klika and Conte (2017) reported that perpetrators who use physical abuse, inappropriate language, and isolation facilitate conditions for PM to coexist with other forms of abuse. Van Harmelen et al. (2011) argued that neglectful acts constitute evidence of PM (e.g., seclusion; withholding medical attention; denying or limiting food, water, shelter, and other basic needs).

Consequences of PM Experienced in Childhood

Mills et al. (2013) and Greenfield and Marks (2010) noted PM experiences in early childhood might manifest in physical growth delays and require access to long-term care throughout a victim’s lifetime. Children who have experienced PM may suffer from behaviors that delay or prevent meeting developmental milestones, achieving academic success in school, engaging in healthy peer relationships, maintaining physical health and well-being, forming appropriate sexual relationships as adults, and enjoying satisfying daily living experiences (Glaser, 2002; Maguire et al., 2015). Neurological and cognitive effects of PM in childhood impact children as they transition into adulthood, including abnormalities in the amygdala and hippocampus (Tyrka at al., 2013). Brown et al. (2019) found that adults who reported experiences of CM had higher rates of negative responses to everyday stress, a larger constellation of unproductive coping skills, and earlier mortality rates (Brown et al., 2019; Felitti et al., 1998). Furthermore, adults with childhood PM experiences reported higher rates of substance abuse than those compared to control groups (Felitti et al., 1998).

Trauma-Related Symptomology. Researchers speculate that children exposed to maltreatment and crises, especially those that come without warning, are at greater risk for developing a host of trauma-related symptoms (Spinazzola et al., 2014). Developmentally, children lack the ability to process and contextualize their lived experiences. Van Harmelen et al. (2010) discovered that adults who experienced child PM had decreased prefrontal cortex mass compared to those without evidence of PM. Similarly, Field et al. (2017) found those unable to process traumatic events produced higher levels of stress hormones (i.e., cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine); these hormones are produced from the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) regions in the brain. Some researchers speculate that elevated levels of certain hormones and hyperactive regions within the brain signal the body’s biological attempt to reduce the negative impact of PM through the fight-flight-freeze response (Porges, 2011; van der Kolk, 2014).

Purpose of Present Study

At the time of this research, there were few formal measures using child self-report to assess how children experience PM. We developed the PMI as an initial quantifiable measure of child PM for children and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 17, as modeled by Tonmyr and colleagues (2011). The PMI was developed in multiple stages, including 1) a review of the literature, 2) a content validity survey with subject matter experts (SMEs), 3) a pilot study (N = 21), and 4) a large sample study (N = 166). An additional instrument, the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children Screening Form (TSCC-SF; Briere & Wherry, 2016), was utilized in conjunction with the PMI to explore occurrences of general trauma symptoms among respondents. The following four research questions were investigated:

- How do respondent demographics relate to PM?

- What is the rate of PM experience with respondents who are presently involved in an open CM case?

- What is the co-occurrence of PM among various forms of CM allegations?

- What is the relationship between the frequency of reported PM experiences and the frequency of general trauma symptoms?

Method

Study 1: PMI Item Development and Pilot

Following the steps of scale construction (Heppner et al., 2016), the initial version of the PMI used current literature and definitions from facilities nationwide that provide care for children who have experienced maltreatment and who are engaged with court systems, mental health agencies, or social services. Our lead researcher, Alison M. Boughn, developed a list of 20 items using category identifications from Glaser (2002) and APSAC (2019). Items were also created using Slep et al.’s (2015) proposed inclusion language for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic codes and codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 11th edition (ICD-11) definition criteria (APA, 2013). Both Boughn and Daniel A. DeCino, our other researcher, reviewed items for consistency with the research literature and removed four redundant items. The final 16 items were reevaluated for readability for future child respondents using a web-based, age range–appropriate readability checker (Readable, n.d.) and were then presented to local SMEs in a content validity survey to determine which would be considered essential for children to report as part of a child PM assessment.

Expert Validation

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) serving as SMEs completed an online content validity survey created by Boughn. The survey was distributed by a Child Advocacy Center (CAC) manager to the MDT. Boughn used the survey results to validate the PMI’s item content relevance. Twenty respondents from the following professions completed the survey: mental health (n = 6), social services (n = 6), law enforcement (n = 3), and legal services (n = 5). The content validity ratio (CVR) was then calculated for the 16 proposed items.

Results. The content validity survey scale used a 3-point Likert-type scale: 0 = not necessary; 1 = useful, but not essential; and 2 = essential. A minimum of 15 of the 20 SMEs (75% of the sample), or a CVR ≥ .5, was required to deem an item essential (Lawshe, 1975). The significance level for each item’s content validity was set at α = .05 (Ayre & Scally, 2014). After conducting Lawshe’s (1975) CVR and applying the ratio correction developed by Ayre and Scally (2014), it was determined that eight items were essential: Item 2 (CVR = .7), Item 3 (CVR = .9), Item 4 (CVR = .6), Item 6 (CVR = .6), Item 7 (CVR = .8), Item 10 (CVR = .6), Item 15 (CVR = .5), and Item 16 (CVR = .6).

Upon further evaluation, and in an effort to ensure that the PMI items served the needs of interdisciplinary professionals, some items were rated essential for specific professions; these items still met the CVR requirements (CVR = 1) for the smaller within-group sample. These four items were unanimously endorsed by SMEs for a particular profession as essential: Item 5 (CVR Social Services = 1; CVR Law Enforcement = 1), Item 11 (CVR Law Enforcement = 1), Item 13 (CVR Law Enforcement = 1), and Item 14 (CVR Law Enforcement = 1).

Finally, an evaluation of the remaining four items was completed to explore if items were useful, but not essential. Using the minimum CVR ≥ .5, it was determined that these items should remain on the PMI: Item 1 (CVR = .9), Item 8 (CVR = .8), Item 9 (CVR = .9), and Item 12 (CVR = .9). The use of Siegle’s (2017) Reliability Calculator determined the Cronbach’s α level for the PMI to be 0.83, indicating adequate internal consistency. Additionally, a split-half (odd-even) correlation was completed with the Spearman-Brown adjustment of 0.88, indicating high reliability (Siegle, 2017).

Pilot Summary

The focus of the pilot study was to ensure effective implementation of the proposed research protocol following each respondent’s appointment at the CAC research site. The pilot was implemented to ensure research procedures did not interfere with typical appointments and standard procedures at the CAC. Participation in the PMI pilot was voluntary and no compensation was provided for respondents.

Sample. The study used a purposeful sample of children at a local, nationally accredited CAC in the Midwest; both the child and the child’s legal guardian agreed to participate. Because of the expected integration of PM with other forms of abuse, this population was selected to help create an understanding of how PM is experienced specifically with co-occurring cases of maltreatment. Respondents were children who (a) had an open CM case with social services and/or law enforcement, (b) were scheduled for an appointment at the CAC, and (c) were between the ages of 8 and 17.

Measures. The two measures implemented in this study were the developing PMI and the TSCC-SF. At the time of data collection, CAC staff implemented the TSCC-SF as a screening tool for referral services during CAC victim appointments. To ensure the research process did not interfere with chain-of-custody procedures, collected investigative testimony, or physical evidence that was obtained, the PMI was administered only after all normally scheduled CAC procedures were followed during appointments.

PMI. The current version of the PMI is a self-report measure that consists of 16 items on a 4-point Likert-type scale that mirrors the language of the TSCC-SF (0 = never to 3 = almost all the time). Respondents typically needed 5 minutes complete the PMI. Sample items from the PMI included questions like: “How often have you been told or made to feel like you are not important or unlovable?” The full instrument is not provided for use in this publication to ensure the PMI is not misused, as refinement of the PMI is still in progress.

TSCC-SF. In addition to the PMI, Boughn gathered data from the TSCC-SF (Briere & Wherry, 2016) because of its widespread use among clinicians to efficiently assess for sexual concerns, suicidal ideation frequency, and general trauma symptoms such as post-traumatic stress, depression, anger, disassociation, and anxiety (Wherry et al., 2013). The TSCC-SF measures a respondent’s frequency of perceived experiences and has been successfully implemented with children as young as 8 years old (Briere, 1996). The 20-item form uses a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = never to 3 = almost all the time) composed of general trauma and sexual concerns subscales. The TSCC-SF has demonstrated high internal consistency and alpha values in the good to excellent ranges; it also has high intercorrelations between sexual concerns and other general trauma scales (Wherry & Dunlop, 2018).

Procedures. Respondents were recruited during their scheduled CAC appointment time. Each investigating agency (law enforcement or social services) scheduled a CAC appointment in accordance with an open maltreatment case. At the beginning of each respondent’s appointment, Boughn provided them with an introduction and description of the study. This included the IRB approvals from the hospital and university, an explanation of the informed consent and protected health information (PHI) authorization, and assent forms. Respondents aged 12 and older were asked to read and review the informed consent document with their legal guardian; respondents aged from 8 to 11 were provided an additional assent document to read. Respondents were informed they could stop the study at any time. After each respondent and legal guardian consented, respondents proceeded with their CAC appointment.