Adverse Childhood Experiences of Professional School Counselors as Predictors of Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress

Eric M. Brown, Melanie Burgess, Kristy L. Carlisle, Desmond Franklin Davenport, Michelle W. Brasfield

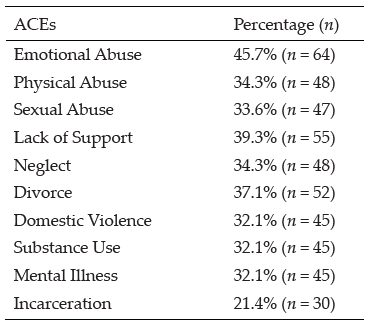

School counselors work closely with students and are often the first point of contact regarding traumatic experiences. It is generally understood that exposure to other individuals’ trauma may lead to a reduction in compassion satisfaction and an increase in secondary traumatic stress, while long-term exposure may result in professional burnout. This study examined the role of school counselors’ (N = 240) own adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as related to compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout. Results indicated that 50% of the professional school counselors in this convenience sample had personal histories of four or more ACEs, which is significantly higher than the general public and passes the threshold for significant risk. Results indicated that the ACEs of school counselors in the present study, as well as some demographic variables, significantly correlated with rates of compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout.

Keywords: school counselors, compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, adverse childhood experiences

As counselors in PK–12 settings, professional school counselors (PSCs) are uniquely positioned to deliver comprehensive school counseling programs that attend to all students’ academic and social/emotional needs (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2019). Providing these comprehensive services may lead to burnout and secondary traumatic stress, which can adversely impact PSCs’ ability to meet students’ academic and social/emotional needs (Mullen & Gutierrez, 2016). Although research has examined various factors that may contribute to burnout such as caseload, lack of administrative support, and tasks unrelated to school counseling (Bardhoshi et al., 2014; Fye, Bergen, & Baltrinic, 2020; Fye, Cook, et al., 2020), few studies have examined whether personal historical factors such as childhood adversity may be related to burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Though self-care is often encouraged in counselor education programs and promoted among practitioners (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014; Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs [CACREP], 2015), we lack knowledge of which PSCs may be more vulnerable to burnout or secondary traumatic stress (Coaston, 2017). Therefore, it is important that we better understand whether a PSC’s own historical experiences of adversity or trauma may make them more susceptible to burnout and secondary traumatic stress, as this may impact their ability to meet students’ needs.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) encompass 10 maladaptive childhood experiences, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, substance abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, divorce, incarcerated family member, household mental illness, and domestic abuse (Crandall et al., 2020; Felitti et al., 1998). Researchers have found that ACEs have the propensity to shape life beyond childhood, often playing a pivotal role in adult development. Several studies have outlined the dangers of multiple ACEs and negative outcomes in adulthood (Crandall et al., 2020; Felitti et al., 1998). Felitti and colleagues’ (1998) seminal study found that ACEs are common, 55.4% of the population having at least one ACE, and 6.2% reporting four or more ACEs. A growing number of subsequent studies have found that ACEs have a dose–response effect, in which a 1-point increase (using a 10-point scale) in one’s ACE score significantly increases the chance of deleterious mental and physical effects in adulthood (Boullier & Blair, 2018; Felitti et al., 1998; Merrick et al., 2017).

Scholars have found that those with four or more ACEs have a 4- to 12-fold increase in deleterious mental and physical outcomes such as depression, anxiety, addiction, and suicide attempts (Crandall et al., 2020; Crandall et al., 2019; Felitti et al., 1998). Researchers have investigated both the dose–response effect and the pervasive nature of ACEs, suggesting that they may be predictive of long-term mental health impacts. Broadly, adults who were exposed to multiple ACEs were more likely to have three or more mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, substance addiction, suicidality, and PTSD (Atzl et al., 2019; Fellitti et al., 1998). This is especially detrimental for minoritized persons, as two large U.S. samples of over 200,000 adults have shown that Black and Latine persons, sexually minoritized individuals, and those coming from lower socioeconomic status (SES) had significantly higher levels of ACEs than White persons, heterosexual individuals, and those coming from middle- to upper-class SES backgrounds (Giano et al., 2020; Merrick et al., 2017). Giano et al. (2020) also found that women had significantly higher rates of ACEs as compared to men. Given that childhood experiences may be a critical determinant of mental health in adulthood, individuals with marginalized identities may be at greater risk for negative long-term mental health outcomes (Giano et al., 2020).

ACEs can also impact job function and satisfaction, financial stability, and increased absences (Anda et al., 2004). Of all the helping professions, researchers note that mental health professionals have some of the highest recorded rates of ACEs (Redford, 2016; Thomas, 2016); however, it is unknown how this relates specifically to the school counseling profession. PSCs serve students in a variety of ways to help students fulfill their academic and social/emotional needs (ASCA, 2019). This ability to provide services may be impacted by professional functioning. The ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors require PSCs to monitor their emotional and physical health while maintaining wellness to ensure effectiveness (ASCA, 2022). However, researchers note that many counselors do not routinely prioritize their own wellness (Coaston, 2017). Therefore, it is important to understand the effect ACEs have on PSCs to ensure that PSCs can meet student needs.

Burnout

Burnout can occur when a PSC feels depleted of their capacity to perform at a high level due to feelings of incompetence, fatigue, or extreme pressures from their work environment (Mullen & Gutierrez, 2016). Due to high student-to-counselor ratios, diminished counselor self-efficacy, job dissatisfaction, and non-counseling duties, PSCs run the risk of experiencing counselor burnout (Holman et al., 2019; Mullen et al., 2017; Rumsey et al., 2020). Bardhoshi et al. (2014) reported organizational factors such as lack of administrator support, the incapability to meet designated annual goals, and non-counseling duties were associated with burnout, whereas Fye, Bergen, and Baltrinic (2020) found that PSCs with fewer years of counseling experience are more prone to burnout.

Identity factors such as gender, race, and SES have been examined in relation to burnout (Fye et al., 2022); however, these factors have not been evaluated within the context of PSCs’ own personal historical experiences, such as their ACEs. Fye et al. (2022) examined demographic and organizational factors on a multidimensional model of wellness, revealing that there were no large systemic differences in wellness due to gender and race/ethnicity; however, individual elements of the wellness model were significant. One study has shown that male BIPOC counseling students report higher levels of exhaustion compared to female BIPOC counseling students (Basma et al., 2021).

Secondary Traumatic Stress

As students continue to experience traumatic events happening in and outside of school, PSCs are often immersed in the traumatic experiences of their students. This consistent exposure could have an impact on school counselors professionally. Indirect exposure to trauma stemming from students’ trauma, witnessing others’ trauma, or being exposed to graphic material is considered secondary exposure (Fye, Cook, et al., 2020; Padmanabhanunni, 2020). When PSCs attend to student trauma and become fixated, overwhelmed, or burdened, they can experience burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Rumsey et al., 2020). Yet, similar to Fye, Cook, et al.’s (2020) study on burnout, Rumsey et al. (2020) found that years of school counseling experience is negatively correlated with secondary exposure and secondary traumatic stress. School counselors with more years of experience are less likely to be affected by secondary traumatic stress (Rumsey et al., 2020). As PSCs are often the first point of contact regarding PK–12 students’ mental health in the aftermath of a traumatic event, additional research is needed regarding PSCs’ experiences of secondary traumatic stress. Presently, there is a gap in the literature regarding how demographic factors and PSCs’ own ACEs scores predict positive and negative job-related outcomes; therefore, it would be advantageous to learn how ACEs and demographic factors, such as gender, race, or SES, might influence compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress.

Compassion Satisfaction

Since the original ACEs study, researchers have turned toward identifying protective factors that may mitigate the effects of harmful childhood experiences. Firstly, compassion satisfaction, while studied limitedly, may serve as a protective factor against burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Stamm, 2010). Compassion satisfaction is defined as a psychological benefit derived from working effectively with clients/students to produce meaningful and positive change in their lives (Stamm, 2010). Researchers note the dearth of literature surrounding gender, race/ethnicity, and PSC wellness, as well as systemic gender and race/ethnicity-related barriers to wellness that exist for PSCs (Bryant & Constantine, 2006; Fye et al., 2022). Currently, the relationship between burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction in PSCs with ACEs is unclear.

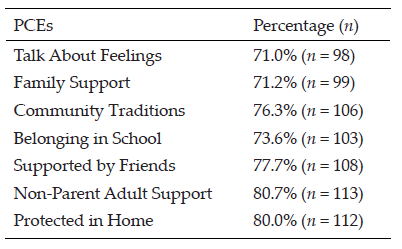

Brown et al. (2022) conducted a study on ACEs, positive childhood experiences (PCEs), and compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress with a diverse national sample of 140 clinical mental health counselors (CMHCs). They found that 43% of participants had four or more ACEs and over 70% had five or more PCEs (Brown et al., 2022). Results from this study found that higher ACEs scores predicted lower compassion satisfaction, but racially minoritized CMHCs, those coming from lower childhood SES, and female CMHCs had higher rates of compassion satisfaction as compared to CMHCs who identified as White, coming from middle- or upper-class SES backgrounds, or male. Furthermore, higher ACEs scores predicted higher rates of burnout, and higher PCEs predicted less burnout (Brown et al., 2022). The relationship between PSCs’ own identity factors (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES) and childhood experiences on job-related outcomes (e.g., compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress) remains unstudied.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of early childhood experiences on the professional quality of life of PSCs. We focused on the rates of ACEs and demographic variables of PSCs and their relationship to burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction. We aimed to answer the following research questions (RQs): 1) What are the mean rates of ACEs, compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress among PSCs? 2) To what extent do PSCs’ ACEs and demographic variables predict compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress? and 3) After separating the participants into two groups (PSCs with three or fewer ACEs and those with four or more ACEs), to what extent do PSCs’ ACEs and demographic variables predict compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress?

Method

Using a cross-sectional, non-experimental correlational design, we reported descriptive statistics (means; RQ 1) and multiple regression models (predictive relationships; RQs 2 and 3). Using G*Power 3.1.9.6, we calculated an a priori power analysis with a .05 alpha level (Cohen, 1988; 1992), a medium effect size for multiple R2 of .09 (Cohen, 1988), and a power of .80 (Cohen, 1992). This power analysis revealed a target number of participants (N = 138).

Participants

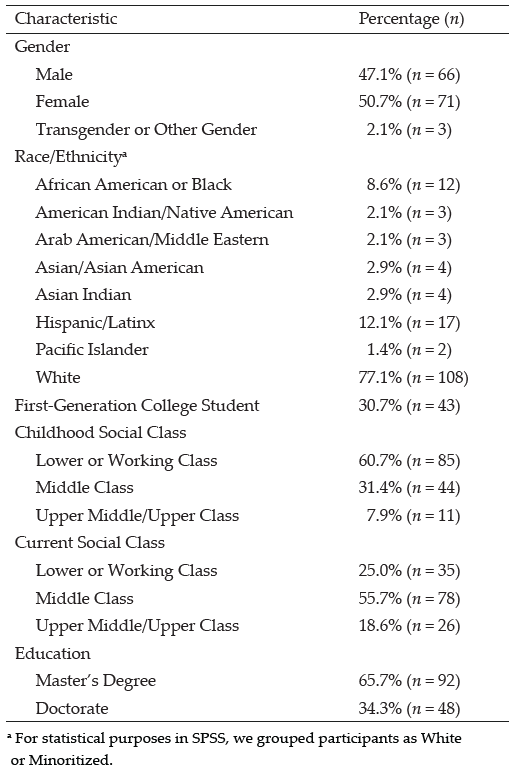

An invitation letter and informed consent document through Qualtrics outlined criteria for school counselors to participate in the study: age 18 and up who work 30 hours or more a week in the field of school counseling. Authors Eric M. Brown, Melanie Burgess, and Kristy L. Carlisle sent Qualtrics invitations to the study through social media, such as X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram. We recruited 240 school counselors who met criteria. We could not calculate a response rate because it was impossible to track responses through social media. The majority (62.9%; n = 151) of participants identified as White. The mean age of the participants in the sample was 35 with a range of 23 to 55. Gender was split almost evenly with 50.8% (n = 122) male and 48.3% (n = 116) female. More than half (60%; n = 144) reported a childhood SES of lower or working class, while only 2.9% (n = 7) reported current lower class, and the majority (56.7%; n = 136) reported current middle class. More demographic information is included in Table 1.

Table 1

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | % (n) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 50.8 (122) |

| Female | 48.3 (22) |

| Transgender or Other Gender | 0.8 (2) |

| Race/Ethnicitya | |

| African American or Black | 7.9 (19) |

| American Indian/Native American | 2.1 (3) |

| Arab American/Middle Eastern | 1.7 (4) |

| Asian/Asian American | 1.7 (4) |

| Asian Indian | 3.3 (8) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 23.3 (56) |

| Pacific Islander | 0.4 (1) |

| White | 62.9 (151) |

| Childhood Socioeconomic Status | |

| Lower or Working Class | 60.0 (144) |

| Middle Class | 33.8 (81) |

| Upper Middle/Upper Class | 5.0 (12) |

Note. N = 240.

a For statistical purposes in SPSS, we grouped PSCs as Minoritized and White.

Instrumentation

In addition to a demographic questionnaire, we used instruments with strong psychometrics to measure ACEs, compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire

Felitti et al. (1998) developed the ACEs Questionnaire to identify instances of abuse and neglect in childhood. The 10-item questionnaire has good test–retest reliability (Dube et al., 2004) and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .78 in one study (Ford et al., 2014) and .90 (Mei et al., 2022) in another. Its structural validity passed invariance tests across demographics, exceeding all thresholds (CFI = .986, TLI = .985, RMSEA = .021, SRMR = .066; Mei et al., 2022). Participants self-report instances of ACEs from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating higher risk for mental and physical ailments and prohibited quality of life. Serious risk is indicated by a score of 4 or higher (Dube et al., 2004).

Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL)

Stamm (2010) created a 30-item questionnaire measuring compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress and reported Cronbach’s alpha scores of .88 for compassion satisfaction, .75 for burnout, and .81 for secondary traumatic stress. Heritage et al. (2018) found good item fit and invariance across demographics in demonstration of construct validity. The ProQOL subscales are described as being low (22 or less), moderate (23–41), or high (42 or higher). Positive feelings about helping ability (compassion satisfaction) are measured with scores of 22 or lower indicating problems. Exhaustion, frustration, and depression (burnout) are measured with scores 42 and higher showing impairment at work. Fear and trauma from work (secondary traumatic stress) are measured with scores 42 and higher indicating fear resulting from work.

As a widely used instrument, recent researchers have offered several critiques, including a four-factor structure with burnout as two latent subscales, traditional burnout and emotional well-being (Sprang & Craig, 2015), or interpreting compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction to be on opposite ends of one spectrum (Geoffrion et al., 2019). Fleckman et al. (2022) used the ProQOL in their sample of PK–12 teachers and did not achieve a sufficient model fit; therefore, they posited that the ProQOL may be more appropriate for human service and mental health professionals compared to educators. Because PSCs are mental health professionals working in education settings, we used the instrument as it was originally designed with the three separate constructs of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress.

Procedure

Our Institutional Review Board approved the current study. Purposeful sample methods included use of a purchased data set of 6,000 counselors’ emails as well as postings on Facebook groups for PSCs. All potential participants received an informed consent document and a Qualtrics link to the three instruments and demographic questionnaire. After data cleaning (i.e., removal of cases with incomplete responses on the instruments) produced 240 usable cases, we computed scores from the instruments and checked assumptions for multiple regression using SPSS 28. Reliability for each instrument showed Cronbach’s alpha score of .86 and an omega score of .87 for the ACEs Questionnaire and .81 Cronbach’s alpha and .82 omega scores for the ProQOL.

Data Analysis and Results

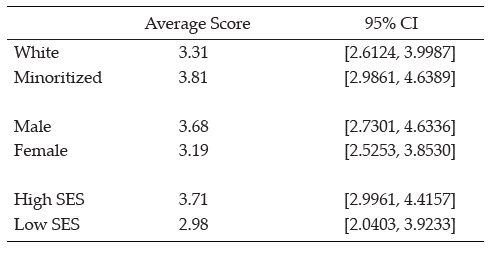

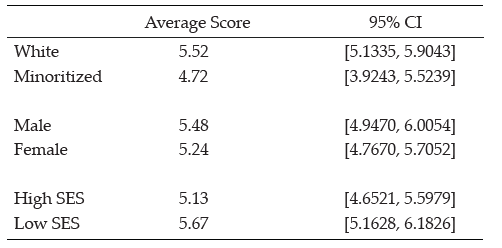

RQ 1 asked for mean scores of ACEs, compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. We calculated a mean ACEs score of 3.68, 95% CI [3.2854, 4.0330] for PSCs, lower than the threshold of 4 and thus just below the range for significant risk. However, 50.42% of participants

(N = 121) reported an ACEs score of 4 or more. Minoritized PSCs had a particularly higher ACEs score (4.9) than White PSCs (2.96). Females had a higher ACEs score (4.14) than males (3.23). Finally, participants with lower childhood SES (low or working) had slightly lower ACEs scores (3.41) than those with higher SES (middle and upper; 3.82 and 5.04). Then we investigated mean scores of PSCs’ compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. For compassion satisfaction, they scored 30.93, 95% CI [30.1798, 31.6785]. When we explored burnout, they scored 27.58, 95% CI [26.2399, 28.2184]. Finally, they showed a mean secondary traumatic stress score of 31.49, 95% CI [30.6610, 32.3223]. PSCs on average have moderate levels of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress.

RQ 2 asked about predictive relationships of ACEs, gender, race/ethnicity, and SES on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. Three linear regression models, one for each subscale, all produced significant results. Model 1 ran a regression of compassion satisfaction on ACEs, gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES, explaining 27.7% of the variance in compassion satisfaction, F(5, 225) = 17.214, p < .001. Gender (β = -0.331), race/ethnicity (β = -0.125), and childhood SES (β = 0.180) significantly predicted compassion satisfaction. ACEs showed nonsignificant results in this model. Being female, being racially minoritized, and having higher childhood SES predicted higher compassion satisfaction (see Table 2).

Table 2

Regression Results: Coefficients (compassion satisfaction, burnout, secondary traumatic stress)

| β | Std. Error | Beta | T | Sig | ||

| Compassion Satisfaction (Constant) | 26.298 | 1.682 | — | 15.631 | < .001 | |

| ACE | 0.010 | 0.121 | .006 | 0.086 | = .931 | |

| Gendera | -3.859 | 0.704 | -.331* | -5.483 | < .001* | |

| Raceb | -1.514 | 0.746 | -.125* | -2.029 | = .044* | |

| Childhood SESc

R2 = .277 (p < .001) |

2.149 | 0.711 | .180* | -3.021 | = .003*

|

|

|

Burnout (Constant) |

27.052 |

1.583 |

— |

17.089 |

< .001 |

|

| ACE | 0.176 | 0.114 | .107 | 1.544 | = .124 | |

| Gendera | 1.714 | 0.662 | .169* | 2.588 | = .010* | |

| Raceb | 2.940 | 0.702 | .279* | 4.189 | < .001* | |

| Childhood SESc R2 = .152 (p < .001) |

-0.175

|

0.669 | -.017 | -0.261 | = .795

|

|

|

Secondary Traumatic Stress (Constant) |

28.695 |

2.139 |

— |

13.413 |

< .001 |

|

| ACE | 0.166 | 0.154 | .079 | 1.081 | = .281 | |

| Gendera | -2.068 | 0.895 | -.159* | -2.311 | = .022* | |

| Raceb | 0.502 | 0.948 | .037 | 0.530 | = .597 | |

| Childhood SESc | 2.171 | 0.904 | .163* | 2.401 | = .017* | |

| R2 = .059 (p = .017) | ||||||

Note. ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences; SES = socioeconomic status.

aFor statistical purposes in SPSS, we grouped gender as female, male, and transgender or other gender.

ᵇFor race, we grouped PSCs as Minoritized and White.

cFor Childhood SES, we grouped PSCs as lower or working class, middle-class, or upper middle/upper class.

Model 2 ran a regression of burnout on ACEs, gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES, explaining 15.2% of the variance in compassion satisfaction, F(5, 225) = 8.062, p < .001. Gender (β = 0.169) and race/ethnicity (β = 0.279) significantly predicted burnout. ACEs and childhood SES showed nonsignificant results in this model. Being male and being White predicted higher burnout (see Table 2).

Model 3 ran a regression of secondary traumatic stress on ACEs, gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES, explaining 5.9% of the variance in secondary traumatic stress, F(5, 225) = 2.862, p = .017. Only gender (β = -0.159) and childhood SES (β = 0.163) significantly predicted secondary traumatic stress. ACEs and race/ethnicity showed nonsignificant results in this model. Being female and having higher childhood SES predicted higher secondary traumatic stress (see Table 2).

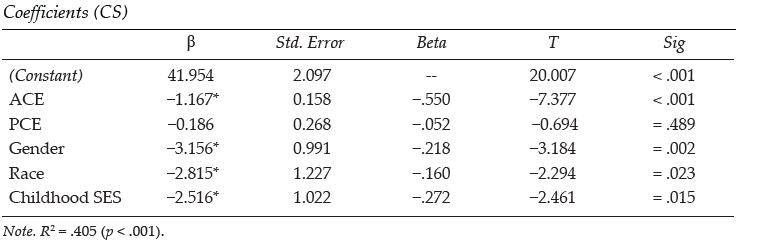

RQ 3 asked about the predictive relationship of ACEs, gender, race/ethnicity, and SES to compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress after dividing the sample into two groups: PSCs with three or fewer ACEs (n = 119) and those with four or more ACEs (n = 121). Three linear regression models for each group all produced significant results. Model 1 ran a regression of compassion satisfaction on ACEs, gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES. For Group 1 (three or fewer ACEs) the model explained 41.7% of the variance in compassion satisfaction, F(5, 109) 15.599, p < .001. Gender (β = -0.369), and childhood SES (β = 0.194) significantly predicted compassion satisfaction. ACEs and race/ethnicity showed nonsignificant results. Being female and having higher childhood SES predicted higher compassion satisfaction for those with three or fewer ACEs. For Group 2 (four or more ACEs), the model explained 26.6% of the variance in compassion satisfaction, F(5, 110) = 7.975, p < .001. Gender (β = -0.277) and race/ethnicity (β = -0.342) significantly predicted compassion satisfaction. ACEs and childhood SES showed nonsignificant results. Being female and being a racially minoritized person predicted higher compassion satisfaction for those with four or more ACEs (see Table 3).

Table 3

Regression Results: Coefficients (compassion satisfaction)

| β | Std. Error | Beta | T | Sig | |

| ACE < 4 (Constant) | 20.214 | 2.846 | — | 7.102 | < .001 |

| ACE | -0.070 | 0.545 | .006 | -0.012 | = .897 |

| Gendera | -5.046 | 1.040 | -.369* | -4.852 | < .001* |

| Raceb | 0.820 | 1.165 | .194 | 2.307 | = .524 |

| Childhood SESc

R2 = .417 (p < .001) |

2.688 | 1.165 | .194* | 2.307 | = .023*

|

|

ACE > 4 (Constant) |

29.897 |

1.990 |

— |

15.024 |

< .001 |

| ACE | 0.286 | 0.228 | .106 | 1.253 | = .213 |

| Gendera | -2.702 | 0.855 | -.277* | -3.161 | = .002* |

| Raceb | -3.296 | 0.821 | -.342* | -4.017 | < .001* |

| Childhood SESc

R2 = .266 (p < .001) |

0.443 | 0.866 | .045 | 0.511 | = .610

|

Note. ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences; SES = socioeconomic status.

aFor statistical purposes in SPSS, we grouped gender as female, male, and transgender or other gender.

ᵇFor race, we grouped PSCs as Minoritized and White.

cFor Childhood SES, we grouped PSCs as lower or working class, middle-class, or upper middle/upper class.

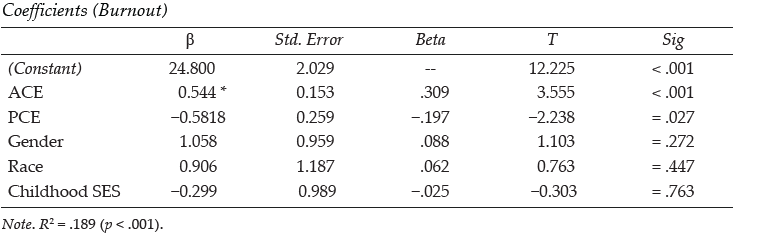

Model 2 ran a regression of burnout on ACEs gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES. For Group 1 (three or fewer ACEs), the model explained 14.5% of the variance in burnout, F(5, 109) = 3.692, p = .004. ACEs (β = 0.249) significantly predicted burnout. Gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES showed nonsignificant results. Having higher ACEs predicted higher burnout. For Group 2 (four or more ACEs), the model explained 35.9% of the variance in burnout, F(5, 110) = 12.336, p < .001. ACEs (β = 0.158), gender (β = 0.277), and race/ethnicity (β = 0.461) significantly predicted burnout. Childhood SES showed nonsignificant results. Having higher ACEs, being male, and being White predicted higher burnout (see Table 4).

Table 4

Regression Results: Coefficients (burnout)

| β | Std. Error | Beta | T | Sig | |

| ACE < 4 (Constant) | 31.882 | 2.448 | — | 13.025 | < .001 |

| ACE | 1.061 | 0.469 | .249* | 2.264 | = .026* |

| Gendera | 0.197 | 0.895 | .020 | 0.220 | = .827 |

| Raceb | -0.806 | 1.104 | -.067 | -0.730 | = .467 |

| Childhood SESc

R2 = .145 (p = .004) |

-1.543 | 1.002 | -.157 | -1.539 | = .127

|

|

ACE > 4 (Constant) |

20.916 |

2.085 |

— |

10.103 |

< .001 |

| ACE | 0.471 | 0.237 | .158* | 1.989 | = .049* |

| Gendera | 2.999 | 0.887 | .277* | 3.382 | = .001* |

| Raceb | 4.939 | 0.852 | .461* | 5.601 | < .001* |

| Childhood SESc

R2 = .359 (p < .001) |

0.877 | 0.899 | .081 | 0.975 | = .332

|

Note. ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences; SES = socioeconomic status.

aFor statistical purposes in SPSS, we grouped gender as female, male, and transgender or other gender.

ᵇFor race, we grouped PSCs as Minoritized and White.

cFor Childhood SES, we grouped PSCs as lower or working class, middle-class, or upper middle/upper class.

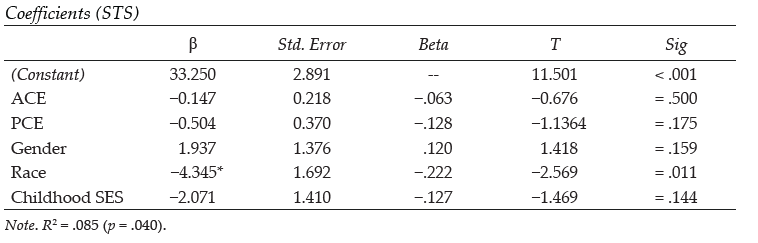

Model 3 ran a regression of secondary traumatic stress on ACEs, gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES. For Group 1 (three or fewer ACEs), the model explained 16.4% of the variance in secondary traumatic stress, F(5, 109) = 4.267, p = .001. Gender (β = -0.303) significantly predicted secondary traumatic stress. ACEs, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES showed nonsignificant results. Being female predicted higher secondary traumatic stress. For Group 2 (four or more ACEs), the model explained 14.5% of the variance in secondary traumatic stress, F(5.110) = 3.745, p = .004. ACEs (β = 0.288) significantly predicted secondary traumatic stress. Gender, race/ethnicity, and childhood SES showed nonsignificant results. Having higher ACEs predicted higher secondary traumatic stress (see Table 5).

Table 5

Regression Results: Coefficients (secondary traumatic stress)

| β | Std. Error | Beta | T | Sig | |

| ACE < 4 (Constant) | 26.661 | 3.813 | — | 6.992 | < .001 |

| ACE | 0.678 | 0.730 | .101 | 0.929 | = .355 |

| Gendera | -4.640 | 1.394 | -.303* | -3.330 | = .001* |

| Raceb | -1.187 | 1.719 | -.062 | -0.691 | = .491 |

| Childhood SESc

R2 = .164 (p = .001) |

1.068 | 1.561 | .069 | 0.684 | = .495

|

|

ACE > 4 (Constant) |

26.189 |

2.378 |

— |

11.015 |

< .001 |

| ACE | 0.858 | 0.273 | .288* | 3.146 | = .002* |

| Gendera | 0.268 | 1.021 | .025 | 0.252 | = .794 |

| Raceb | 0.916 | 0.980 | .086 | 0.934 | = .352 |

| Childhood SESc

R2 = .145 (p = .004) |

1.765 | 1.035 | .163 | 1.705 | = .091

|

Note. ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences; SES = socioeconomic status.

aFor statistical purposes in SPSS, we grouped gender as female, male, and transgender or other gender.

ᵇFor race, we grouped PSCs as Minoritized and White.

cFor Childhood SES, we grouped PSCs as lower or working class, middle-class, or upper middle/upper class.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to establish the average rates of ACEs, compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in PSCs as well as determine the extent to which PSCs’ own ACEs might predict compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in a U.S. sample of school counselors. This study is unique in that it is the first to explore PSCs’ personal historical predictors and their relationship with job-related variables, both establishing the present rates of ACEs while also examining their potential to be risk factors for PSCs. As professional organizations (ASCA, 2022) and previous literature (Padmanabhanunni, 2020) noted the importance of having PSCs monitor their own wellness to ensure that their own trauma does not influence their work, this study provides a deeper understanding of how personal adversity may influence professional responsibilities.

Minoritized PSCs in our convenience sample had significantly more ACEs than White PSCs, which is congruent with previous studies (Giano et al., 2020; Merrick et al., 2017). While Brown et al. (2022) established racial differences in ACEs for CMHCs for its sample, noting that racially minoritized CMHCs had higher ACEs scores than White CMHCs, in this study we established gender differences, in which female PSCs had higher rates of ACEs compared to male PSCs in the present study’s sample. This extends previous literature, which reported ACEs scores in aggregate for pediatric and adult populations (Boullier & Blair, 2018; Merrick et al., 2017). The most striking finding in our study was that 50.42% of PSCs in our convenience sample had four or more ACEs, which was slightly higher than the 43% that Brown et al. (2022) found in CMHCs, and significantly higher than the approximately 6% found in large U.S. and Austrian samples (Felitti et al., 1998; Riedl et al., 2020), suggesting PSCs may have a personal history that includes more ACEs than the general population. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown that those within mental health fields may tend to have higher rates of childhood adversity and trauma (Brown et al., 2022; McKim & Smith-Adcock, 2014; Thomas, 2016). Yet, despite having higher rates of ACEs, participants in our sample reported moderate levels of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress on average, which is supported by previous research and theory related to these constructs, as PSCs’ stress and job satisfaction are mediated by burnout (Mullen et al., 2017).

Our examination of the compassion satisfaction of PSCs showed that as a whole, those who identified as female, racially minoritized persons, and those who came from higher childhood SES were more likely to experience higher compassion satisfaction. For PSCs having three or fewer ACEs, being female and having higher childhood SES predicted higher compassion satisfaction. For PSCs with four or more ACEs, being female and being racially minoritized predicted higher compassion satisfaction. We found these results, which were also congruent with Brown et al.’s (2022) study with CMHCs, to be notable. It may be expected that coming from a higher childhood SES would result in higher compassion satisfaction as higher SES may be a protective factor. Yet, female and racially minoritized PSCs reporting higher rates of compassion satisfaction despite having higher ACEs scores on average is worth noting, as this builds upon recent findings that BIPOC PSCs have elevated essential wellness

(i.e., meaning and purpose) compared to White PSCs (Fye et al., 2022).

In terms of who is more likely to suffer from burnout, in the total sample, we found that being male and being White predicted higher levels of burnout compared to PSCs who identified as being female and racially minoritized. Previous literature has shown that years of experience is negatively correlated with burnout (Fye, Cook, et al., 2020); however, our data extends this to other demographic variables. For those with fewer than three ACEs, having higher ACEs predicted higher burnout, suggesting that regardless of the ACEs threshold, as the number of ACEs increases, PSCs are more susceptible to burnout. For those with four or more ACEs, having higher rates of ACEs, being male, and being White predicted higher burnout scores. This lends further support to research showing that male counseling graduate students experience heightened levels of exhaustion compared to their female peers (Basma et al., 2021). Considering the higher rates of ACEs in the female and racially minoritized groups, it is notable that these two groups of PSCs experienced burnout less than male and White counselors.

Implications for School Counselors and Counselor Education

The results of the present study contribute to scholarship regarding PSC wellness, highlighting potential identity-related and personal historical predictors of positive and negative job-related outcomes that can impact PSCs and their work with students. These results are noteworthy for practicing school counselors, as well as counselor education programs dedicated to the continued health and longevity of the school counseling profession. Given that our sample was split in half, with PSCs self-reporting above and below the threshold for ACEs, we acknowledge that this may be reflective of those presently working in the field. This split presents two distinct profiles for PSCs, those who have ACEs scores above the threshold of four or more, and those who had ACEs scores of three or fewer. Regardless of profile, any increase in ACEs score puts a PSC at risk for being more susceptible to burnout. In monitoring their wellness, PSCs can reflect on how these risk factors could subsequently impact their professional functioning. Similarly, counselor educators can build reflective practices into their programs to increase pre-service school counselors’ self-awareness regarding their wellness.

PSCs-in-training need to be made aware of the effects of ACEs, not only due to the effects on students, but also the effects they may have on their own professional well-being. Counselor educators and supervisors may advise PSCs-in-training to seek counseling to process their ACEs prior to entering the field fully after graduation. There are several evidence-based counseling modalities that aid in the processing of trauma and acute stress (e.g., EMDR, cognitive process therapy, STAIR Narrative Therapy). Though childhood adversity is not synonymous with trauma, the high rates of ACEs of counselors as evidenced in this study and that of Brown and colleagues (2022) indicate that trauma-informed education may be necessary. The 2024 CACREP standards (CACREP, 2023) say relatively little regarding requirements to educate about trauma, yet it will be important for counselor educators to equip counselors-in-training with knowledge concerning both how to care for traumatized students and also to care for themselves.

Limitations

This study is limited by the nature of survey research such as self-reporting bias and inability to assess all factors that may be influencing the relationship, specifically external factors that previous studies have explored. It is important to note that this study did not examine organizational factors that previous research has shown to be impactful regarding PSCs’ burnout, such as school counselor caseload, PSCs’ supportive relationships (e.g., supervision, mentorship), and the role of school climate (Holman et al., 2019; Mullen et al., 2017; Rumsey et al., 2020). Research has indicated that years of experience (Rumsey et al., 2020) and organizational variables (e.g., non-counseling duties, role ambiguity, supervisor support; Fye, Bergen, & Baltrinic, 2020; Holman et al., 2019) are mitigating factors in PSCs’ experience of secondary traumatic stress. Qualitative research may provide a richer understanding of the phenomena of these outcomes for school counselors. For example, why do PSCs with higher childhood SES have higher levels of secondary traumatic stress?

Splitting the sample in half (PSCs with three or fewer ACEs and PSCs with four or more) produced two groups (n = 119 and n = 121), which individually did not meet our required power analysis (N = 138). While we believe in the potential of the results to shed light on the issue of PSCs’ compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress, further research may confirm or elaborate upon the findings. Furthermore, because the sample in the current study did not match previous samples’ reporting rate of reported ACEs scores (e.g., Felitti et al., 1998; Riedl et al., 2020), this study may be replicated on a different sample to contribute to trends in ACEs scores among the PSC population.

A significant limitation to our study included our lack of racially minoritized counselors. As a result, we combined racially minoritized counselors and compared them to White counselors, which limited our ability to distinguish between the unique strengths and struggles that may exist within a given racial group. More research needs to be conducted on counselors from various ethnic and cultural groups both within the U.S. and globally. It would be helpful to know what protective factors may exist for school counselors from racially or ethnically marginalized backgrounds around the world. We believe that the results of this study should not draw attention away from numerous studies that have shown that systemic and organizational factors such as school work environment and school counselor caseload have a significant impact on the professional resilience of PSCs (Bardhoshi et al., 2014; Holman et al., 2019; Mullen et al., 2017; Rumsey et al., 2020). The results of this study do not suggest that the problem of burnout is solely or primarily a result of the personal history of PSCs.

Future Research

Exploring more demographic variables, personal variables, and work characteristics may be beneficial in understanding the relationship between these factors and the presence of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. In addition to investigating the aforementioned variables, future research may focus on an experimental pre-/post-test design providing a group of school counselors training regarding secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and wellness practices. This may be particularly helpful for those who have experienced four or more ACEs due to the research that childhood trauma is linked to poor health in adulthood (Anda et al., 2002, 2004; Dube et al., 2004; Frewen et al., 2019; Gondek et al., 2021; Merrick et al., 2017; Mwachofi et al., 2020). Future research may also include an examination of PSCs’ rates of ACEs and the types of schools served. For example, scholars may examine whether PSCs with higher ACEs tend to work in schools where the rates of ACEs are higher for children. Furthermore, considering the timing of the current study with data collection occurring prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, assessing the roles of the pandemic, current economic uncertainty, and ongoing racial injustices on these variables would be informative as to how they may be related.

Conclusion

We sought to examine the rates of ACEs of PSCs and learn whether ACEs are correlated with higher rates of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. We found that an unusually high rate of PSCs in our sample had four or more ACEs and are therefore susceptible to factors such as burnout and secondary traumatic stress. As a result of these findings, we believe that in conjunction with calls for structural change to PSCs’ work environment (e.g., student caseload), greater attention needs to be given to ways that PSCs’ own history may factor into their susceptibility to burnout and secondary traumatic stress.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/ethics

American School Counselor Association. (2019). ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs.

American School Counselor Association. (2022). ASCA ethical standards for school counselors.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/44f30280-ffe8-4b41-9ad8-f15909c3d164/EthicalStandards.pdf

Anda, R. F., Fleisher, V. I., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., Whitfield, C. L., Dube, S. R., & Williamson, D. F. (2004). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and indicators of impaired adult worker performance. The Permanente Journal, 8(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/03-089

Anda, R. F., Whitfield, C. L., Felitti, V. J., Chapman, D., Edwards, V. J., Dube, S. R., & Williamson, D. F. (2002). Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric Services, 53(8), 1001–1009. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001

Atzl, V. M., Narayan, A. J., Rivera, L. M., & Lieberman, A. F. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and prenatal mental health: Type of ACEs and age of maltreatment onset. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(3), 304–314. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30802085

Bardhoshi, G., Schweinle, A., & Duncan, K. (2014). Understanding the impact of school factors on school counselor burnout: A mixed-methods study. The Professional Counselor, 4(5), 426–443. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1063202.pdf

Basma, D., DeDiego, A. C., & Dafoe, E. (2021). Examining wellness, burnout, and discrimination among BIPOC counseling students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 49(2), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12207

Boullier, M., & Blair, M. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics and Child Health, 28(3), 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2017.12.008

Brown, E. M., Carlisle, K. L., Burgess, M., Clark, J., & Hutcheon, A. (2022). Adverse and positive childhood experiences of clinical mental health counselors as predictors of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. The Professional Counselor, 12(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.15241/emb.12.1.49

Bryant, R. M., & Constantine, M. G. (2006). Multiple role balance, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction in women school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 9(4), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.5330/prsc.9.4.31ht45132278x818

Coaston, S. C. (2017). Self-care through self-compassion: A balm for burnout. The Professional Counselor, 7(3), 285–297. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1165683.pdf

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). 2016 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/2024-Standards-Combined-Version-6.27.23.pdf

Crandall, A., Broadbent, E., Stanfill, M., Magnusson, B. M., Novilla, M. L. B., Hanson, C. L., & Barnes, M. D. (2020). The influence of adverse and advantageous childhood experiences during adolescence on young adult health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 108, e104644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104644

Crandall, A., Miller, J. R., Cheung, A., Novilla, L. K., Glade, R., Novilla, M. L. B., Magnusson, B. M., Leavitt, B. L., Barnes, M. D., & Hanson, C. L. (2019). ACEs and counter-ACEs: How positive and negative childhood experiences influence adult health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, e104089.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104089

Dube, S. R., Williamson, D. F., Thompson, T., Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2004). Assessing the reliability of retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences among adult HMO members attending a primary care clinic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(7), 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.009

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Fleckman, J., M., Petrovic, L., Simon, K., Peele, H., Baker, C. N., Overstreet, S., & New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. (2022). Compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout: A mixed methods analysis in a sample of public-school educators working in marginalized communities. School Mental Health, 14, 933–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09515-4

Ford, D. C., Merrick, M. T., Parks, S. E., Breiding, M. J., Gilbert, L. K., Edwards, V. J., Dhingra, S. S., Barile, J. P., & Thompson, W. W. (2014). Examination of the factorial structure of adverse childhood experiences and recommendations for three subscale scores. Psychology of Violence, 4(4), 432–444.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037723

Frewen, P., Zhu, J., & Lanius, R. (2019). Lifetime traumatic stressors and adverse childhood experiences uniquely predict concurrent PTSD, complex PTSD, and dissociative subtype of PTSD symptoms whereas recent adult non-traumatic stressors do not: Results from an online survey study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1606625

Fye, H. J., Bergen, S., & Baltrinic, E. R. (2020). Exploring the relationship between school counselors’ perceived ASCA National Model implementation, supervision satisfaction, and burnout. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12299

Fye, H. J., Cook, R. M., Baltrinic, E. R., & Baylin, A. (2020). Examining individual and organizational factors of school counselor burnout. The Professional Counselor, 10(2), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.15241/hjf.10.2.235

Fye, H. J., Cook, R. M., & Baylin, A. (2022). Exploring individual and organizational predictors of school counselor wellness. Professional School Counseling, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X211067959

Geoffrion, S., Lamothe, J., Morizot, J., & Giguère, C. (2019). Construct validity of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale in a sample of child protection workers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32, 566–576. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22410

Giano, Z., Wheeler, D. L., & Hubach, R. D. (2020). The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health, 20, 1327. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09411-z

Gondek, D., Patalay, P., & Lacey, R. E. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and multiple mental health outcomes through adulthood: A prospective birth cohort study. Social Science & Medicine-Mental Health, 1, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100013

Heritage, B., Rees, C. S., & Hegney, D. G. (2018). The ProQOL-21: A revised version of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale based on Rasch analysis. PLoS ONE, 13(2), e0193478. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193478

Holman, L. F., Nelson, J., & Watts, R. (2019). Organizational variables contributing to school counselor burnout: An opportunity for leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and systemic change. The Professional Counselor, 9(2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.15241/lfh.9.2.126

McKim, L. L., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2014). Trauma counsellors’ quality of life. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36(1), 58–69. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s10447-013-9190-z

Mei, X., Li, J., Li, Z.-S., Huang, S., Li, L.-L., Huang, Y.-H., & Lui, J. (2022). Psychometric evaluation of an adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) measurement tool: An equitable assessment or reinforcing biases? Health & Justice, 10, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-022-00198-2

Merrick, M. T., Ports, K. A., Ford, D. C., Afifi, T. O., Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2017). Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.chiabu.2017.03.016

Mullen, P. R., Blount, A. J., Lambie, G. W., & Chae, N. (2017). School counselors’ perceived stress, burnout, and job satisfaction. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18782468

Mullen, P. R., & Gutierrez, D. (2016). Burnout, stress, and direct student services among school counselors. The Professional Counselor, 6(4), 344–359. https://doi.org/10.15241/pm.6.4.344

Mwachofi, A., Imai, S., & Bell, R. A. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in adulthood: Evidence from North Carolina. Journal of Affective Disorders, 267, 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.021

Padmanabhanunni, A. (2020). Caring does not always cost: The role of fortitude in the association between personal trauma exposure and professional quality of life among lay trauma counselors. Traumatology, 26(4), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000262

Redford, J. (Director). (2016). Resilience: The biology of stress and the science of hope [Film]. KPJR Films.

Riedl, D., Lampe, A., Exenberger, S., Nolte, T., Trawöger, I., & Beck, T. (2020). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and associated physical and mental health problems amongst hospital patients: Results from a cross-sectional study. General Hospital Psychiatry, 64, 80–86.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.005

Rumsey, A. D., McCullough, R., & Chang, C. Y. (2020). Understanding the secondary exposure to trauma and professional quality of life of school counselors. Professional School Counseling¸ 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20973643

Sprang, G., & Craig, C. (2015). An inter-battery exploratory factor analysis of primary and secondary traumatic stress: Determining a best practice approach to assessment. Best Practices in Mental Health, 11(1), 1–13. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1679872314?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise manual for the professional quality of life scale (ProQOL). https://proqol.org/proqol-manual

Thomas, J. T. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences among MSW students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 36(3), 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2016.1182609

Yildirim, İ. (2008). Relationships between burnout, sources of social support and sociodemographic variables. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 36(5), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.5.603

Eric M. Brown, PhD, LPC, is an assistant professor at the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine at Boston University. Melanie Burgess, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Memphis. Kristy L. Carlisle, PhD, is an assistant professor at Old Dominion University. Desmond Franklin Davenport, MS, is a doctoral student at the University of Memphis. Michelle W. Brasfield, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Memphis. Correspondence may be addressed to Eric M. Brown, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, 72 E. Concord St., Boston, MA 02118, ebrown1@bu.edu.