May 2, 2025 | Volume 15 - Issue 2

Alexandra Frank, Amanda C. DeDiego, Isabel C. Farrell, Kirby Jones, Amanda C. Tracy

State policies and school district regulation largely shape the roles and responsibilities of school counselors in the United States. The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) provides guidance on recommendations for school counseling practice; however, state policies may not align with guiding principles. Using a rubric informed by the ASCA National Model, we conducted a problem-driven content analysis to explore state policy alignment with the Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess components of the model. Our findings indicate state policy differences between K–8 and 9–12 grade levels and within each rubric component. School counselors and school counselor educators can use these findings to support strategic advocacy efforts aimed at increased clarity around school counselors’ roles and responsibilities.

Keywords: content analysis, advocacy, state policy, school counseling, ASCA National Model

What is a school counselor? The profession has a long history of attempting to answer this question, not always successfully. Role confusion in school counseling was highlighted by Murray (1995) who stated that the roles of school counselors often vary from the printed job description. Murray attributed unclear counseling duties to misunderstandings about school counselors’ roles by stakeholders, such as administrators, parents, and students. Murray also found that differences in legislative definitions of school counseling contributed to role confusion. As an early act of advocacy in school counseling, Murray suggested developing a uniform definition of school counseling, advocating for that definition, and engaging in effective communication strategies among stakeholders as solutions to role confusion. Since this early movement to define school counseling roles, professional groups (e.g., The American School Counselor Association [ASCA]), academic organizations (e.g., School Counselors for MTSS), and professional conferences (e.g., The Evidence-Based School Counseling Conference and ASCA conference) have joined in the efforts to describe school counselor identity and roles. Despite these efforts, school counselors across the United States struggle with the lack of clarity in their roles (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009; Chandler et al., 2018).

School counselors’ impacts on student outcomes are well-documented (O’Connor, 2018). When describing the role and influence of school counselors, researchers point to improved student outcomes, such as decreased student behavior issues (Reback, 2010), increased student achievement (Carrell & Hoekstra, 2014), and increased college-going behavior (Hurwitz & Howell, 2014). School counselors’ roles in supporting student social–emotional health became particularly important when navigating the effects of COVID-19 (McCoy-Speight, 2021). However, Murray’s (1995) concern about legislative differences in defining the role of a school counselor remains. Despite evidence describing positive impacts of school counselors on student outcomes, the school counselor role is often misunderstood and continues to vary from state to state (Carey & Dimmitt, 2012). Recently, state differences were most pronounced in Texas Senate Bill 763 (2023), which proposed to equip chaplains to serve as school counselors, and in Florida’s emphasis on parents as resiliency coaches (Florida Governor’s Press Office, 2023). Additionally, factors such as organizational constraints (Alexander et al., 2022), student–counselor ratios (Kearney et al., 2021), and engagement in non-counseling duties (Blake, 2020; Camelford & Ebrahim, 2017; Chandler et al., 2018) continue to hinder the impact that school counselors can make within their school settings. Intrigued by Murray’s observation regarding the long-standing issues with school counseling roles and duties differing from state to state and recent state initiatives to supplement the role of a school counselor with chaplains or parents (e.g., Texas and Florida), we sought to explore how state-level policies and statutes define school counselor roles and responsibilities and how they align with national recommendations.

Defining School Counseling

Noting the need for a uniform definition of school counseling, we turned to ASCA. Although ASCA is not the only professional organization supporting school counselors, it has the longest history (formed in 1952) and largest membership (approximately 43,000). Additionally, ASCA exists for the explicit purpose of supporting school counselors by “providing professional development, enhancing school counseling programs, and researching effective school counseling practices” (n.d.-a, About ASCA section). ASCA (2023) defines school counseling as a comprehensive, developmental, and preventative support aimed at improving student outcomes. ASCA (n.d.-b) advocates for a united school counseling vision and voice among stakeholders. Despite their efforts, researchers, educational leaders, and state policymakers continue to hold varied perspectives about the definitions, needs, and roles of school counselors. Although ASCA (2019; 2023) clearly delineates appropriate and inappropriate school counseling roles and responsibilities, school counselors often find themselves asked to engage in activities deemed inappropriate by ASCA (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009; Chandler et al., 2018).

School counselors can use collaboration and advocacy to promote a more appropriate use of their time (McConnell et al., 2020) and to mediate feelings of burnout (Holman et al., 2019). Researchers have discussed the importance of advocacy as integral to pre–school counselor training (Havlik et al., 2019), individual school counseling practice (Perry et al., 2020), and system-wide professional unity (Cigrand et al., 2015). However, such efforts are often limited to a single school or district and often do not include state-level advocacy.

The ASCA National Model

To support their mission of improving student outcomes, ASCA (2019) recommends a national model as a framework for school counselors. The ASCA National Model is aligned with school counseling priorities, such as data-informed decision-making, systemic interventions, and developmentally appropriate care considerations. Implementation is associated with both student-facing and school counselor–facing benefits. In an introduction to a special issue on comprehensive school counseling programs, Carey and Dimmitt (2012) described findings across six statewide studies highlighting the relationship between program implementation and positive student outcomes, including improved attendance and decreases in rates of student discipline. Pyne (2011) and more recently Fye and colleagues (2022) demonstrated correlations between program implementation and school counselor job satisfaction. Pyne found that school counselors with administrative support and staff collaboration related to program implementation experienced higher rates of job satisfaction. Fye et al. noted that as implementation of the ASCA National Model increased, role ambiguity decreased and job satisfaction increased.

The ASCA National Model consists of four components: Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess. We outline the model in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Four Components of The ASCA National Model

| Define |

Standards to support school counselors

School counselors are supported in implementation and assessment of a comprehensive school counseling program by existing standards such as the ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors, the ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors, and the ASCA School Counselor Professional Standards & Competencies. |

| Manage |

Effective and efficient implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program

ASCA outlines planning tools to support a program focus, program planning, and appropriate school counseling activities. |

| Deliver |

The actual delivery of a comprehensive school counseling program

School counselors implement developmentally appropriate activities and services to support positive student outcomes. School counselors engage in direct (e.g., instruction, appraisal and advisement, counseling) and indirect (e.g., consultation, collaboration, referrals) student services. ASCA (2019) stipulates that school counselors should spend 80% of their time in direct or indirect student services. School counselors should spend 20% or less of their time on school support activities and/or program planning. |

| Assess |

Data-driven accountability measures to assess the efficacy of program delivery

School counselors are charged with evaluating their program’s efficacy and implementing improvements, based on student needs. School counselors should demonstrate that students are positively impacted because of the counseling program. |

We extend the Assess component to also include research-based examples on factors contributing to a school counselor’s efficacy. Such factors include student–school counselor ratios. For decades, ASCA has advocated for a student–school counselor ratio of 250:1 as well as broader support for school counselor roles (Kearney et al., 2021). Yet, data from the 2021–2022 school year put the average national student–school counselor ratio at 408:1 (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2023). Researchers demonstrate that schools with ASCA-approved ratios experience increased student attendance, higher test scores, and improved graduation rates (e.g., Carey et al., 2012; Carrell & Carrell, 2006; Goodman-Scott et al., 2018; Lapan et al., 2012).

Alternatively, Donohue and colleagues (2022) demonstrated that higher ratios relate to worse outcomes for students. Notably, minoritized students and their school communities often face the brunt of increased student–school counselor ratios (Donohue et al., 2022; Education Trust, 2018). Thus, the ASCA alignment is not only concerned with improved student outcomes but also with the equitable provision of mental health services. Given the role ASCA plays in advocating for and structuring the school counselor’s role and responsibilities, we chose to use the components of the ASCA National Model (2019) as a theoretical framework guiding our study. We have incorporated our theoretical framework throughout, including data collection, data analysis, results, discussion, and implications.

Method

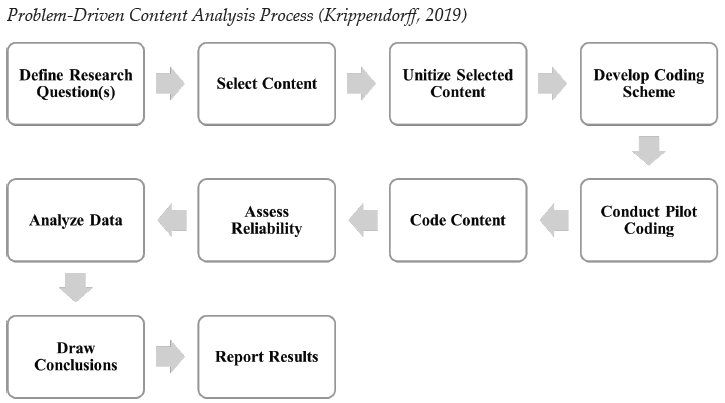

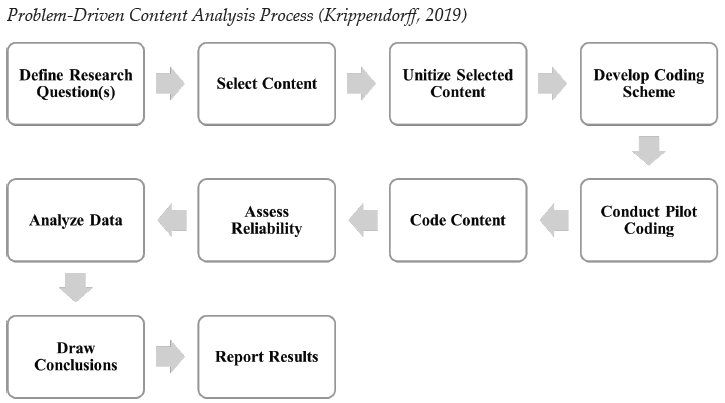

The purpose of our study was to understand how state policies align with the ASCA National Model. We analyzed state policies defining and guiding the practice of school counseling. In any inquiry, the type and characteristics of the data available should dictate the research methods (Flick, 2015). Content analysis allows researchers to identify recurring themes, patterns, and trends (Krippendorff, 2019). By systematically coding and categorizing content, researchers can uncover insights that might not be immediately apparent through casual observation. Additionally, it enables researchers to analyze large volumes of data in a systematic and replicable manner, reducing the impact of personal bias and increasing the reliability of findings. Because of these factors, we found content analysis to be the best method for our inquiry. We chose a subtype of content analysis—problem-driven content analysis (Krippendorff, 2019). Problem-driven content analysis aims to answer a research question. The research question guiding our analysis was: How are state policies aligned or misaligned with the ASCA National Model?

Sample

Using the State Policy Database maintained by the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE; 2023), we pulled current policies from all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (N = 51) that dictate the role of school counselors and school counseling services. As ASCA (n.d.-c) describes, terms used for school counseling services can vary, and although “school counselor” is favorable to “guidance counselor,” both terms may be found. However, in NASBE’s State Policy Database, the category was specifically listed as “counseling, psychological, and social services,” and the subcategory was listed as “school counseling—elementary” and “school counseling—secondary” (NASBE, 2023). We included policies that govern kindergarten through eighth grade (K–8) and ninth through 12th grade (9–12). Data included all policies related to school counseling delivery and certification, with State Policy Databases sorted into policies governing K–8 (n = 156, 47.42%) and 9–12 (n = 173, 52.58%) levels, for a total of 329 policies.

Design

From our research question to data reporting, we followed the problem-driven content analysis steps (see Figure 1). We collected language from the policies, including policy type and policy name, and then determined if school counseling was encouraged, recommended, or not specified as either. We built a spreadsheet to divide, define, and identify the state policies into sampling units. We divided them into originating state, policy type, requirements for having school counselors in schools, policy name, and summary of the policy. Additionally, we separated the data into K–8 and 9–12 education designations.

Figure 1

Problem-Driven Content Analysis Process (Krippendorff, 2019)

The analytical process began with filtering policies for inclusion outlined in our selection criteria. We built a spreadsheet to divide, define, and identify the legislative bills into sampling units. We focused on dividing them into originating state, bill number, year, subcategory, and summary of the bill. After completing the spreadsheet with all the data, Kirby Jones and Amanda C. Tracy tested our coding frame on a sample of text. Although content analysis does not require piloting, Schreier (2012) suggested piloting around 20% of the data to test the reliability of the coding frame. We used 20% of our data (n = 66) to conduct pilot coding.

We approached the data analysis deductively, with the components of the ASCA National Model (2019) acting as our initial codes. Prior to analysis, we created a coding rubric that we used to analyze each state’s school counseling policy (see Table 2). We used the four components of the ASCA National Model as the rubric criteria: Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess. Within each criterion, we developed standards ranging from 1 point to 5 points. We chose point ranges based on the information within each criterion. For example, the Define criterion included three standards for 5 total points. We awarded 1 point if a state required (versus recommended) school counselors in school; we awarded 1 point if a state required school counselors to be licensed and/or certified based on a graduate degree; and we awarded 3 points if a state specifically described all three focus areas of school counseling—academic, college/career, and social/emotional.

Alexandra Frank, Amanda C. DeDiego, and Isabel C. Farrell were involved in creating the rubric and completing initial pilot coding to ensure the usability and utility of the rubric. All team members met throughout the process to ensure workability and fidelity. Following initial testing, each coding pair was trained to appropriately analyze state-level policy data using the rubric. Before finalizing rubric metrics for each state, all team members met again to review metrics and to determine final scores for each state. Importantly, individual state-level rubric scores do not indicate grades, but rather demonstrate evidence of alignment between state-level policy as it is written and the ASCA National Model (2019).

Table 2

Rubric to Evaluate State Policy for Adherence to the ASCA National Model

| Aspects of the ASCA National Model |

|

Define

5 points

|

Manage

1 point |

Deliver

1 point |

Assess

2 points |

|

Required

1 point

|

Education

1 point |

Focus

3 points |

Implementation

1 point |

Use of Time

1 point |

Accountability

1 point |

Ratio

1 point

|

| State has provisions requiring school counselors |

Requires school counselors to be licensed/certified |

Areas of focus include:

(1) academic,

(2) college/career,

(3) social/emotional |

Role includes appropriate school counseling activities |

80% of time spent in direct/indirect services supporting student achievement, attendance, and discipline |

Evaluation of school counselor role included |

Maximum

of 250:1

|

Research Team

Our research team consisted of two counselor educators, two counselor education doctoral students, and one master’s-level counseling student. We began meeting as a research team in summer 2023. Conceptualization, data collection, and analysis occurred throughout the fall, ending in December 2023. Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell continued with edits and writing in 2024. Varying counseling backgrounds (including clinical mental health and school counseling), education settings (e.g., urban, rural, research, teaching), and personal identities were represented. All members are united by a passion for mentorship and advocacy. Additionally, DeDiego and Farrell provided expertise in legislative advocacy and content analysis, and Frank and Tracy provided expertise in school counseling. All members are affiliated with counseling programs accredited by the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell designed the coding frame and trained Jones and Tracy on the coding process. Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell also resolved any coding conflicts. For example, if a state regulation was unclear, Frank, DeDiego, and Farrell met and decided what code would apply. All members of the research team communicated via email, Google Docs, and/or Zoom meetings to build consensus through the data collection and data analysis processes.

Trustworthiness

To enhance trustworthiness in this study, we followed the checklist for content analysis developed by Elo et al. (2014), which includes three phases: preparation, organization, and reporting. The preparation phase involves determining the most appropriate data source to address the research question and the appropriate scope of the content and analysis. In this phase, we determined the focus of the project to be policy defining school counselor roles; thus, state-level legislation was the most appropriate data source. Use of the NASBE (2023) database offered a means of limiting scope and focus of the content. Using deductive coding (McKibben et al., 2022), we first developed the rubric coding framework based on the ASCA National Model (2019) and then conducted pilot coding to test the framework.

During the organization phase, the checklist addresses organizing coding and theming strategies. We first conducted pilot coding to establish how to apply the ASCA National Model (2019) to coding legislation. We evaluated the content using the rubric to determine how the legislation aligned with the ASCA National Model. Elo et al. (2014) suggested researchers also determine how much interpretation will be used to analyze the data. The coding framework using the ASCA National Model offers structure to this interpretation. Data were coded separately for trustworthiness by Jones and Tracy. Then we met to compare coding. If there was discrepancy, one of us reviewed the data in order to reach a two-thirds majority for all of the coding. By the end of the process, all coding met the threshold of two-thirds majority agreement.

In the Elo et al. (2014) checklist, the reporting phase addresses how to represent and share the results of the analysis. This includes ensuring that categories used to report findings capture the data well and that results are clear and understandable for targeted audiences. The use of a rubric framework offers a clear method to represent and share results of the analysis process.

Results

Our results highlighted trends in the scope and practice of school counseling across the United States. We organized results by rubric strands (Table 3) and by state, analyzing results for K–8 (Appendix A) and 9–12 (Appendix B). We further describe our results within each strand of the ASCA National Model (2019): Define, Manage, Deliver, and Assess.

Table 3

Summary of Rubric Outcomes by Category

|

K–8 |

9–12 |

|

Yesa |

Nob |

Yesa |

Nob |

| Required |

37 (72.55%) |

14 (27.45%) |

40 (78.73%) |

11 (21.57%) |

| Education |

40 (78.43%) |

11 (21.57%) |

50 (98.04%) |

1 (1.96%) |

| Focus

Academic

College/Career

Social/Emotional |

35 (68.63%)

37 (72.55%)

35 (68.63%) |

16 (31.37%)

14 (27.45%)

16 (31.37%) |

40 (78.43%)

41 (80.39%)

40 (78.43%) |

11 (21.57%)

10 (19.61%)

11 (21.57%) |

| Implementation |

34 (66.67%) |

17 (33.33%) |

36 (70.59%) |

15 (29.41%) |

| Use of Time |

17 (33.33%) |

34 (66.76%) |

10 (19.61%) |

41 (80.39%) |

| Accountability |

21 (41.18%) |

30 (58.82%) |

29 (56.86%) |

22 (43.14%) |

| Ratio |

2 (3.92%) |

49 (96.08%) |

3 (5.88%) |

48 (94.12%) |

aIndicates awarding of a point, as outcome was represented in the policy.

bIndicates no point was awarded, as outcome was not represented in the policy.

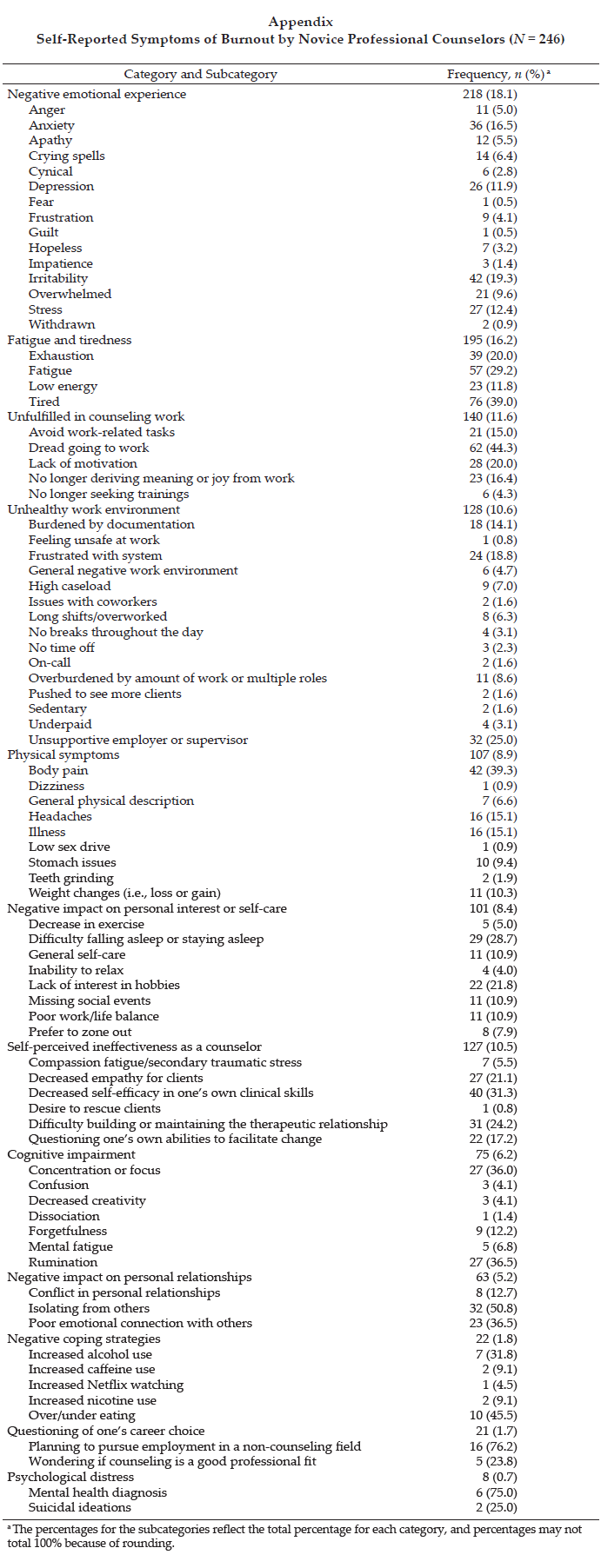

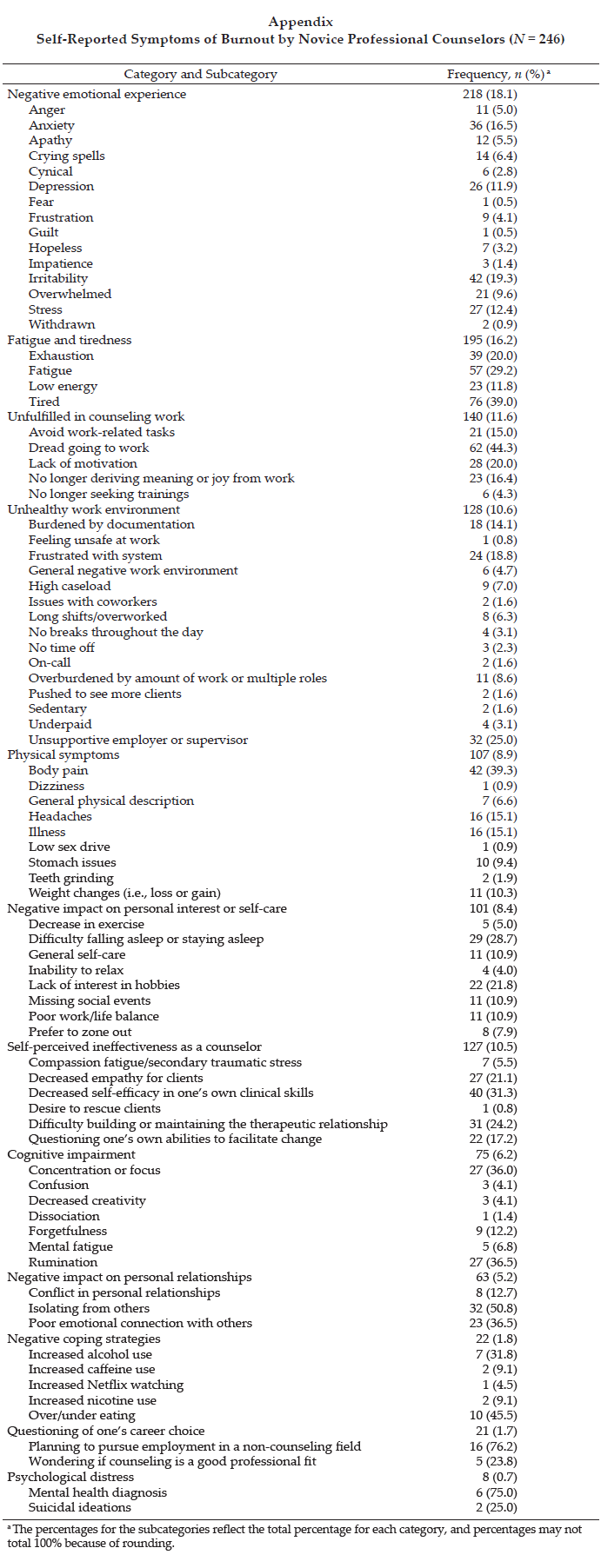

In the state policies, school counselors were designated as required, encouraged, or not specified. For the K–8 level, 72.55% (n = 37) of states required school counselors in schools, 19.61% (n = 10) encouraged the presence of school counselors, and 7.84% (n = 4) of states did not specify a requirement of school counselor presence. At the 9–12 level, 78.73% (n = 40) of states required school counselors in schools, 19.60% (n = 10) encouraged the presence of school counselors, and 1.96% (n = 1) of states did not specify a requirement of school counselor presence.

The category of not specified included policies that were uncodified or policies that did not address the requirement of school counselors at all. The majority of states required school counselors at the K–8 (n = 37, 72.55%) and 9–12 (n = 40, 78.73%) levels. At the K–8 level, one state had a policy that was uncodified (Michigan) and three did not address the requirements of school counselors (i.e., Hawaii, South Dakota, Wyoming). At the 9–12 level, one state had an uncodified policy (Hawaii) and one did not specify a requirement for school counselors (South Dakota). Forty states (80%) for K–8 and 50 states (98.04%) for 9–12 required school counselors to have a license or certification in school counseling. The only state that did not require certification or licensure was Florida. Thirty-five states (70%) for K–8 and 40 states (78.43%) for 9–12 described the role of a school counselor as supporting students’ academic success. Thirty-seven states (72.54%) for K–8 and 41 states (80.39%) for 9–12 described the role of a school counselor as supporting college and career readiness. Finally, 35 states (68.63%) for K–8 and 40 states (78.43%) for 9–12 described the role of a school counselor as supporting students’ social and emotional growth.

Within the Manage aspect of the ASCA National Model (2019), we determined if the state outlined appropriate school counseling activities in alignment with ASCA recommendations in policy or statute (e.g., small groups, counseling, classroom guidance, preventative programs). Thirty-four states (66.67%) for K–8 and 36 states (70.59%) for 9–12 outlined school counseling activities in their policy. For Deliver, only 17 states (33.33%) for K–8 and 10 states (20%) for 9–12 outlined whether or not the majority of school counselors’ time should be spent providing direct and indirect student services.

Moreover, for the Assess category, we evaluated whether the state policy required school counselors to do an evaluation of their role and/or counseling services. Twenty-one states (58.82%) for K–8 and 29 states (56.86%) for 9–12 outlined evaluation requirements. Finally, we evaluated whether the state complied with the ASCA student–school counselor ratio of 250:1. Two states for K–8 (3%; i.e., New Hampshire, Vermont) and three states for 9–12 (5.9%; i.e., Michigan, New Hampshire, Vermont) complied with the recommended ratios. A few states (i.e., Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, Minnesota, Montana) recommended that state districts follow the ASCA 250:1 recommendation, but it was not a requirement; those state ratios exceeded 250:1.

Next, we examined overall trends of compliance by grade level and by state. For K–8, eight states (15.69%) had higher scores of ASCA National Model (2019) compliance (i.e., Arkansas, Maine, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oregon, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Wisconsin) compared to other states in our dataset with a score of 8 out of 9. For 9–12, six states (11.76%) scored 8 out of 9 (i.e., Arkansas, Maine, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Wisconsin). Excluding Hawaii, South Dakota, and Wyoming, because their state policies did not address the requirements of K–8 school counselors, the states with the lowest scores of ASCA National Model compliance, with 1 out of 9 for K–8 were Alabama, Maryland, Missouri, and North Dakota (n = 4, 7.8%). For 9–12 state policy, two states (3.9%)scored 1 out of 9 (i.e., Massachusetts, South Dakota).

Discussion

Given ASCA’s (n.d.-b) advocacy efforts to develop a unified definition of school counseling, there is a need to assess how those advocacy efforts translate to state policy. Although individual state and district policies shed light on existing discrepancies between school counselor roles and responsibilities, our analysis also provides evidence of alignment with the ASCA National Model (2019) in some areas. These results can inform strategic efforts for further alignment. School counselors can use advocacy to support their role and promote responsibilities more aligned with the ASCA National Model (McConnell et al., 2020). We outline our discussion by again utilizing the four components of the ASCA National Model as a conceptual framework.

Define

Our findings suggest that the Define component of the ASCA National Model (2019) is well-represented in state and district policies. Although our results highlight differences in policy governing practice in K–8 and 9–12 schools, for the most part, all state and district policies required or encouraged the presence of a school counselor. Additionally, the vast majority of states required that individuals practicing as school counselors hold the appropriate licensure and/or certification. Similarly, most state and district policies defined a school counselor’s role as contributing to students’ academic, college/career, and/or social/emotional development. Vigilance in advocacy efforts remains important, as language in policy can change with each legislative session. For example, Texas Senate Bill No. 763 (2023) introduced legislation allowing chaplains to serve in student support roles instead of school counselors. The Lone Star State School Counselor Association (2023) quickly took action with a published brief condemning the language in the bill. As a result of advocacy efforts, lawmakers changed the verbiage in the bill to hire chaplains in addition to school counselors, rather than in lieu of them.

Similarly, Florida’s First Lady, Casey DeSantis (Florida Governor’s Press Office, 2023), announced a shift in counseling services to emphasize resiliency and include resiliency coaches—a role in which “moms, dads, and community members will be able to take training covering counseling standards and resiliency education standards” and provide a “first layer of support to students” (para. 8). Although the Florida School Counselor Association emphasizes advocacy efforts, it has not yet published a response to the changes in Florida’s resilience instruction and support plans (Weatherill, 2023). The legislation in Texas and Florida and the response from state-level school counselor associations highlight, once again, the importance of advocacy for creating and maintaining a uniform definition of school counseling.

Manage

Although ASCA clearly defines appropriate and inappropriate school counseling activities, state policy is less specific on codifying the appropriate use of school counselors’ time and resources. Although most states encouraged appropriate school counseling activities, states did not specifically define appropriate school counseling activities or provide protection around school counselors’ time to implement appropriate school counseling activities. Such findings are consistent with the literature (Bardhoshi & Duncan, 2009; Chandler et al., 2018). Florida’s K–8 policy suggests that school counselors should implement a program that suits the school and department, whereas some states’ K–8 policy, such as New Jersey’s, recommends incorporating the ASCA National Model (2019). Several states include uncodified policy addressing the implementation of a school counseling program. However, as such recommendations are not codified into policy, they do not dictate the day-to-day activities of school counselors. Interestingly, new legislation introducing support roles for chaplains and family/community members only bolsters the need to protect school counselors’ time. Texas Senate Bill No. 763 references the need for support, services, and programming. Florida First Lady Casey DeSantis similarly emphasizes the need for support and mentorship. School counselors are trained professionals equipped to support student outcomes (ASCA, 2019). One wonders whether legislative efforts introducing chaplains and family members would be needed if school counselors’ time was protected in ways to better support students with appropriate school counseling duties. Thus, there remains an opportunity for increased advocacy surrounding the implementation of school counseling programs with specific attention on appropriate versus inappropriate school counseling activities.

Deliver

ASCA suggests that school counselors should spend 80% of their time in direct/indirect services to support student outcomes. Such efforts are pivotal, as research suggests that school counselors play a key role in supporting student outcomes (e.g., Carey & Dimmitt, 2012; O’Connor, 2018). Researchers indicate that school counselors within a comprehensive school counseling program play an integral role in supporting improved student attendance (Carey & Dimmitt, 2012), graduation rates (Hurwitz & Howell, 2014), and academic performance (Carrell & Hoekstra, 2014). However, few states support student outcomes by codifying a school counselor’s use of time into policy. Idaho’s 9–12 policy instructs school counselors to use most of their time on direct services. While not equivalent to ASCA’s 80%, such efforts represent a start to protecting school counselors’ time and ensuring that school counselors are able to make the impact they are well-trained to in their school settings. Similar to Manage, current legislative efforts only highlight the importance of school counselors spending a majority of their time supporting students through direct services.

Assess

ASCA continues to focus their advocacy efforts on student–school counselor ratios with good reason; our findings indicate that 2% of K–8 state and district policies and 3% of 9–12 policies specifically outlined a 250:1 ratio that aligns with ASCA recommendations. Yet, researchers demonstrate that reduced student–counselor ratios support improved student outcomes (Carey et al., 2012; Carrell & Carrell, 2006; Goodman-Scott et al., 2018; Lapan et al., 2012). Further, minoritized students and their communities often face the negative consequences of increased student–counselor ratios (Donohue et al., 2022). As such, further advocacy around student–school counselor ratios is also needed from an equity perspective. Some states, such as Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, and Montana, recommended ASCA ratios, but as is the case with appropriate versus inappropriate school counseling activities, without policy “teeth” to enforce recommendations, school counselors are often continuing to practice in settings that far exceed ASCA ratios, as is consistent with recent findings (NCES, 2023).

Although many states did not codify policies aligned with the ASCA National Model (2019), several states (North Dakota, New Jersey, Delaware) made reference to the ASCA National Model and recommended alignment. Our analysis supports previous research indicating that advocacy works (Cigrand et al., 2015; Havlik et al., 2019; Holman et al., 2019; McConnell et al., 2020; Perry et al., 2020). Our findings also highlight the value of supporting professional identity through membership in both national organizations and state-level advocacy groups.

Implications

We explored implications for school counselor educators, school counselors, and school counseling advocates. School counselor educators must prepare future school counselors for their roles as advocates. Counselor educators also play an important role in equipping future school counselors with an understanding of the landscape of the profession (McMahon et al., 2009). As such, including state-level policy and district-level conversations in curriculum helps connect counseling students with the evolving policies guiding their work. The rubric created for this research offers a valuable tool to explore state and school district alignment with the ASCA National Model (2019) and demonstrate areas to focus advocacy efforts. Counseling programs often participate in advocacy efforts, such as Hill Day. School counselor educators can use state-level and district-level policy as a springboard to promote specific advocacy efforts with state and local legislation. On a local level, school counselor educators can use our rubric to frame practice conversations for future school counselors to prepare for future conversations with school principals. Finally, school counselor educators can continue engaging in policy-level research to support ongoing school counseling advocacy. School counselor educators can further illuminate the impacts of school counseling policy by describing perspectives of practicing school counselors. School counselor educators can also engage in quantitative research methods to study the relationships between school counselor satisfaction and state policy adherence to the ASCA National Model (2019).

School counselors can use our rubric to analyze alignment of school districts when examining job descriptions during their job searches. School counselors could also use the rubric as part of the evaluation component of a comprehensive school counseling program. From our analysis, it appears most imperative that advocacy efforts focus on school counselors’ use of time and student–counselor ratios. Using data, school counselors can continue to advocate for their role to become more closely aligned to ASCA’s recommendations. Kim et al. (2024) described the “urgent need” (p. 233) for school counselors to engage in outcome research. We hope that our framework provides a tool for school counselors to engage in evaluation and advocacy based on our findings. However, school counselors should not be alone in their advocacy efforts. School counseling advocates, including educational stakeholders, counselors, school counselor educators, and educational policymakers, should continue supporting school counselors by advocating on their behalf at the district, state, and national level.

Future research may focus on the disconnect between state policy and how the districts enact those policies. A content analysis comparing state policy to district rules, regulations, and practices is needed to understand how state policy and district practices align. Finally, although there is frequent legislative advocacy from ASCA, there is a lack of data on state legislators’ knowledge about the ASCA National Model (2019) and ASCA priorities. School counseling researchers can use qualitative methods to interview state legislators, especially after events such as Hill Day, to better detail what legislators understand about the roles and impacts of school counselors.

Limitations

The purpose of content analysis was to discover patterns in large amounts of data through a systematic coding process (Krippendorff, 2019). We are all professional counselors or counselors-in-training with a passion for advocacy. Thus, as with any qualitative work, there is potential for bias in the coding process. Interrater reliability was used to mitigate this risk. There are many factors that impact the practice of school counseling beyond state-level policy. District policies and school leadership vastly impact the ways that state policy is interpreted and enacted in schools. Thus, this content analysis represents only school counseling regulation as described in policy and may not fully represent the day-to-day experiences of school counselors.

Conclusion

Although confusion and role ambiguity muddy the school counseling profession, advocacy efforts and outcome research act as cleansers. By providing a rubric to assess alignment between state policy and the ASCA National Model, we hoped to clarify the current state of school counseling practice and provide a helpful tool for future school counselors, current practitioners, educational leaders, and policymakers.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Alexander, E. R., Savitz-Romer, M., Nicola, T. P., Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., & Carroll, S. (2022). “We are the heartbeat of the school”: How school counselors supported student mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Professional School Counseling, 26(1b). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X221105557

American School Counselor Association. (n.d.-a). About ASCA. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/About-ASCA

American School Counselor Association. (n.d.-b). Advocacy and legislation. https://bit.ly/ASCAadvocacylegislation

American School Counselor Association (n.d.-c). Guidance counselor vs. school counselor. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/c8d97962-905f-4a33-958b-744a770d71c6/Guidance-Counselor-vs-School-Counselor.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2019). ASCA National Model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.).

American School Counselor Association. (2023). The role of the school counselor. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/getmedia/ee8b2e1b-d021-4575-982c-c84402cb2cd2/Role-Statement.pdf

Bardhoshi, G., & Duncan, K. (2009). Rural school principals’ perception of the school counselor’s role. The Rural Educator, 30(3), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v30i3.445

Blake, M. K. (2020). Other duties as assigned: The ambiguous role of the high school counselor. Sociology of Education, 93(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040720932563

Camelford, K. G., & Ebrahim, C. H. (2017). Factors that affect implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program in secondary schools. Vistas Online, 1–10.

Carey, J., & Dimmitt, C. (2012). School counseling and student outcomes: Summary of six statewide studies. Professional School Counseling, 16(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600204

Carey, J., Harrington, K., Martin, I. M., & Hoffman, D. (2012). A statewide evaluation of the outcomes of the implementation of ASCA National Model school counseling programs in rural and suburban Nebraska high schools. Professional School Counseling, 16(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600203

Carrell, S. E., & Carrell, S. A. (2006). Do lower student to counselor ratios reduce school disciplinary problems? The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 5(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2202/1538-0645.1463

Carrell, S. E., & Hoekstra, M. (2014). Are school counselors an effective education input? Economics Letters, 125(1), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.07.020

Chandler, J. W., Burnham, J. J., Riechel, M. E. K., Dahir, C. A., Stone, C. B., Oliver, D. F., Davis, A. P., & Bledsoe, K. G. (2018). Assessing the counseling and non-counseling roles of school counselors. Journal of School Counseling, 16(7), n7. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1182095.pdf

Cigrand, D. L., Havlik, S. G., Malott, K. M., & Jones, S. G. (2015). School counselors united in professional advocacy: A systems model. Journal of School Counseling, 13(8), n8. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1066331.pdf

Donohue, P., Parzych, J. L., Chiu, M. M., Goldberg, K., & Nguyen, K. (2022). The impacts of school counselor ratios on student outcomes: A multistate study. Professional School Counseling, 26(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X221137283

Education Trust. (2018). Funding gaps: An analysis of school funding equity across the U.S. and within each state.

https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/FundingGapReport_2018_FINAL.pdf

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633

Flick, U. (2015). Qualitative Inquiry—2.0 at 20? Developments, trends, and challenges for the politics of research. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(7), 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415583296

Florida Governor’s Press Office. (2023, March 22). First lady Casey DeSantis announces next steps in Florida’s first-in-the-nation approach to create a culture of resiliency and incentivize parental involvement in schools [Press release]. https://www.flgov.com/eog/news/press/2023/first-lady-casey-desantis-announces-next-steps-floridas-first-nation-approach

Fye, H. J., Schumacker, R. E., Rainey, J. S., & Guillot Miller, L. (2022). ASCA National Model implementation predicting school counselors’ job satisfaction with role stress mediating variables. Journal of Employment Counseling, 59(3), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/joec.12181

Goodman-Scott, E., Sink, C. A., Cholewa, B. E., & Burgess, M. (2018). An ecological view of school counselor ratios and student academic outcomes: A national investigation. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(4), 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12221

Havlik, S. A., Malott, K., Yee, T., DeRosato, M., & Crawford, E. (2019). School counselor training in professional advocacy: The role of the counselor educator. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 6(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2018.1564710

Holman, L. F., Nelson, J., & Watts, R. (2019). Organizational variables contributing to school counselor burnout: An opportunity for leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and systemic change. The Professional Counselor, 9(2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.15241/lfh.9.2.126

Hurwitz, M., & Howell, J. (2014). Estimating causal impacts of school counselors with regression discontinuity designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00159.x

Kearney, C., Akos, P., Domina, T., & Young, Z. (2021). Student-to-school counselor ratios: A meta-analytic review of the evidence. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(4), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12394

Kim, H., Molina, C. E., Watkinson, J. S., Leigh-Osroosh, K. T., & Li, D. (2024). Theory-informed school counseling: Increasing efficacy through prevention-focused practice and outcome research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 102(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12507

Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N. C., Stanley, B., & Pierce, M. E. (2012). Missouri professional school counselors: Ratios matter, especially in high-poverty schools. Professional School Counseling, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600207

Lone Star State School Counselor Association. (2023). SB 763 and Texas school counselors. https://www.lonestarstateschoolcounselor.org/news_issues

McConnell, K. R., Geesa, R. L., Mayes, R. D., & Elam, N. P. (2020). Improving school counselor efficacy through principal-counselor collaboration: A comprehensive literature review. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 32(2). https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1063&context=mwer

McCoy-Speight, A. (2021). The school counselor’s role in a post-COVID-19 era. In I. Fayed & J. Cummings (Eds.), Teaching in the post COVID-19 era (pp. 697–706). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74088-7_68

McKibben, W. B., Cade, R., Purgason, L. L., & Wahesh, E. (2022). How to conduct a deductive content analysis in counseling research. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 13(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2020.1846992

McMahon, H. G., Mason, E. C. M., & Paisley, P. O. (2009). School counselor educators as educational leaders promoting systemic change. Professional School Counseling, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0901300207

Murray, B. A. (1995). Validating the role of the school counselor. The School Counselor, 43(1), 5–9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23901422

National Association of State Boards of Education. (2023). State policy database. https://statepolicies.nasbe.org

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). National teacher and principal survey. Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ntps

O’Connor, P. J. (2018). How school counselors make a world of difference. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(7), 35–39.

https://kappanonline.org/oconnor-school-counselors-make-world-difference

Perry, J., Parikh, S., Vazquez, M., Saunders, R., Bolin, S., & Dameron, M. L. (2020). School counselor self-efficacy in advocating for self: How prepared are we? Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 13(4), 5. https://research.library.kutztown.edu/jcps/vol13/iss4/5

Pyne, J. R. (2011). Comprehensive school counseling programs, job satisfaction, and the ASCA National Model. Professional School Counseling, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X1101500202

Reback, R. (2010). Schools’ mental health services and young children’s emotions, behavior, and learning. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(4), 698–725. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20528

S.B. 763, 88th Cong. (2023). https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=88R&Bill=SB763

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529682571

Weatherill, A. (2023). Florida Department of Education update. Florida Department of Education. https://www.myflfamilies.com/sites/default/files/2023-11/DOE%20Update-DCF%20committee%20meeting%206-28-23.pdf

Appendix A

Breakdown of State Rubric Scores for ASCA Alignment for K–8 Schools

|

Define

(5 points)

|

Manage

(1 point) |

Deliver

(1 point) |

Assess

(2 points) |

State Score

(9 points) |

|

Required

(1 point)

|

Education

(1 point) |

Focus

(3 points) |

Implementation

(1 point) |

Use of Time

(1 point) |

Accountability

(1 point) |

Ratio

(1 point) |

Total |

| AL |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| AK |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

| AZ |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| AR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| CA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| CO |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| CT |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| DE |

1 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| DC |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| FL |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| GA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| HI |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| ID |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| IL |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| IN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| IA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| KA |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| KY |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| LA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| ME |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| MD |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| MA |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| MI |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| MN |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| MI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| MO |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| MT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| NE |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| NV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| NH |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

| NJ |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| NM |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NY |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NC |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| ND |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| OH |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| OK |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| OR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| PA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| RI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| SC |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| SD |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| TN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| TX |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| UT |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| VT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

| VA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| WA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| WV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WY |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

37 |

40 |

107 |

34 |

17 |

21 |

2 |

– |

Note. Categories refer to the ASCA National Model (2019).

Appendix B

Breakdown of State Rubric Scores for ASCA Alignment for 9–12 Schools

|

Define

(5 points)

|

Manage

(1 point) |

Deliver

(1 point) |

Assess

(2 points) |

State Score

(9 points) |

|

Required

(1 point)

|

Education

(1 point) |

Focus

(3 points) |

Implementation

(1 point) |

Use of Time

(1 point) |

Accountability

(1 point) |

Ratio

(1 point) |

Total |

| AL |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| AK |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| AZ |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| AR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| CA |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| CO |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| CT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| DE |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| DC |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| FL |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| GA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| HI |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| ID |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| IL |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| IN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| IA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| KA |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| KY |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| LA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| ME |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| MD |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| MA |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| MI |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

| MN |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| MI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| MO |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| MT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| NE |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| NV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NH |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

| NJ |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| NM |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NY |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| NC |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| ND |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| OH |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| OK |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| OR |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

| PA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| RI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

| SC |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| SD |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| TN |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| TX |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| UT |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| VT |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

| VA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| WA |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

| WV |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WI |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

8 |

| WY |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| Total |

40 |

50 |

121 |

36 |

10 |

29 |

3 |

– |

Note. Categories refer to the ASCA National Model (2019).

Alexandra Frank, PhD, NCC, is an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Amanda C. DeDiego, PhD, NCC, ACS, BC-TMH, LPC, is an associate professor at the University of Wyoming. Isabel C. Farrell, PhD, NCC, LPC, is an associate professor at Wake Forest University. Kirby Jones, MA, LCMHCA, is a licensed counselor at Camel City Counseling. Amanda C. Tracy, MS, NCC, PPC, is a doctoral candidate at the University of Wyoming. Correspondence may be addressed to Alexandra Frank, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, School of Professional Studies, 651 McCallie Ave, Room 105D, Chattanooga, TN 37403, Alexandra-Frank@utc.edu.

Oct 31, 2023 | Volume 13 - Issue 3

Byeolbee Um, Lindsay Woodbridge, Susannah M. Wood

This content analysis examined articles on international counseling students published in selected counseling journals between 2006 and 2021. Results of this study provide an overview of 18 articles, including publication trends, methodological designs, and content areas. We identified three major themes from multiple categories, including professional practices and development, diverse challenges, and personal and social resources. Implications for counseling researchers and counselor education programs to increase understanding and support for international counseling students are provided.

Keywords: international counseling students, counseling journals, content analysis, publication trends, counseling researchers

International counseling students (ICSs) can be defined as individuals from outside the United States who seek professional training by enrolling in counselor education programs in the United States. After graduation, they often keep contributing to the counseling field as professional counselors or counselor educators, either in the United States or their home countries (Behl et al., 2017). In 2021, non-resident international students accounted for 1.02% of master’s students and 3.81% of doctoral students in counseling programs accredited by the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP; 2022). However, because these percentages do not include international students who have resident alien status in the United States (Karaman et al., 2018), the actual numbers of international students in counseling programs may be higher. Despite the underestimated number of ICSs in CACREP-accredited programs, Ng (2006) found that at least one international student was enrolled in 41% of CACREP-accredited programs, which suggested that many counselor education programs already had some degree of global cultural diversity. Considering that the number of ICSs in the United States has risen within a few decades (CACREP, 2022; Ng, 2006), additional research is needed on this population and how best to prepare them for professional practice.

Research on International Students in Counseling Programs

While in training, ICSs, like domestic students, experience pressure to perform across academic, practical, and personal contexts (Thompson et al., 2011). However, ICSs face the additional challenges of adapting to a new culture and practicing counseling in that culture (Ju et al., 2020; Kuo et al., 2021; Ng & Smith, 2009). These challenges stem from having varying levels of experience using English in an academic context, adapting to new sociocultural and interpersonal patterns, and navigating key clinical factors of counselor education such as supervision and therapeutic relationships (Jang et al., 2014; C. Li et al., 2018; Y. Mori et al., 2009). Researchers have found that ICSs perceive more barriers and concerns regarding their training, such as academic problems and role ambiguity in supervision (Akkurt et al., 2018; Ng & Smith, 2009).

Regarding the experiences of ICSs, researchers have paid scholarly attention to the concept of acculturation, which is the assimilation process an individual experiences in response to the psychological, social, and cultural forces they are exposed to in a new dominant culture (C. Li et al., 2018; Ng & Smith, 2012). According to counseling studies, ICSs’ levels of acculturation and acculturative stress were associated with several variables related to their professional development, including counseling self-efficacy, language anxiety, and diverse academic and life needs (Behl et al., 2017; Interiano-Shiverdecker et al., 2019; C. Li et al., 2018). For example, Interiano-Shiverdecker et al. (2019) found that two domains of acculturation—ethnic identity and individualistic values—were positively associated with counseling self-efficacy for international counseling master’s students. Researchers have also uncovered the potential issues ICSs can experience related to a lack of acculturation: Behl et al. (2017) found that students’ acculturative stress was positively associated with their academic, social, cultural, and language needs.

With goals of uncovering effective coping strategies and identifying characteristics of high-quality training environments, researchers have investigated the personal and academic experiences of ICSs (Lau & Ng, 2012; Nilsson & Wang, 2008; Park et al., 2017; Woo et al., 2015). Woo and colleagues (2015) identified several coping tools of ICSs. These tools included self-directed strategies such as engaging in reflection and keeping up with the latest literature, support from mentors, and networking among international students and graduates (Woo et al., 2015). Researchers have attended to strategies that support ICSs’ development of cultural competence and commitment to social justice (Delgado-Romero & Wu, 2010; Karaman et al., 2018; Ng & Smith, 2012). For example, Delgado-Romero and Wu (2010) piloted a social justice group intervention with six Asian ICS participants and found the intervention to be a useful way to empower students and enhance their critical consciousness about inequity.

Supervision has been another area of focus in ICS research. Through interviews and surveys of ICSs, researchers have identified supervision strategies that support ICSs’ developing cultural competence, professional development, and self-efficacy (Mori et al., 2009; Ng & Smith, 2012; Park et al., 2017). A shared theme across these studies is the importance of clear communication. Findings of two studies (Mori et al., 2009; Ng & Smith, 2012) support supervisors engaging ICS supervisees in communication about critical topics such as cultural differences and the purpose and expectations of supervision. Based on a consensual qualitative analysis of interviews with 10 ICS participants, Park et al. (2017) recommended that programs and supervisors make sure to share basic information about systems of counseling, health care, and social welfare in the United States.

Necessity of ICS Research

Across academic units, there has been a growing attention to international graduate students (Anandavalli et al., 2021; Vakkai et al., 2020). Given the increasing representation of international students in counseling programs, researchers have called for academic and practical strategies to support ICSs’ success in training (Lertora & Croffie, 2020; Woo et al., 2015). These calls are aligned with the values of professional counseling organizations. Specifically, the American Counseling Association (ACA; 2014) endorsed respect for diversity and multiculturalism as elements of counselor competence. This value is reflected in the ACA Code of Ethics, including Standard F.11.b, which urges counselor educators to value a diverse student body in counseling programs. Similarly, the CACREP standards have identified counseling programs as responsible for working to include “a diverse group of students and to create and support an inclusive learning community” (CACREP, 2015, p. 6). Because counselors must have a profound comprehension of and commitment to diversity, experiences with multiculturalism during professional training programs are essential (O’Hara et al., 2021; Ratts et al., 2016). In this vein, the presence of international students in counseling programs can be beneficial for both domestic and international students by enhancing trainees’ understanding of diversity and multicultural counseling competencies (Behl et al., 2017; Luo & Jamieson-Drake, 2013). Given that there is a substantially increasing need for addressing multiculturalism, diversity, and social justice in the counseling profession, counseling programs’ efforts to recruit various minority student groups, including ICSs, will contribute to not only counselor training but also client outcomes in the long term.

However, despite the importance of the topic, researchers have consistently indicated that research on ICSs has been quite limited (Behl et al., 2017; Lau et al., 2019). In counseling research, there is a history of researchers using content analysis to provide a comprehensive overview of topics that are underrepresented but have growing importance. For example, Singh and Shelton (2011) published a content analysis of qualitative research related to counseling lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer clients. Involving the summarization of findings from a body of literature into a few key categories or content areas (Stemler, 2001), content analysis is a useful methodology for expanding the field’s knowledge and understanding of the topic. Considering ICSs’ unique challenges and their potential contributions to enriching diversity in counseling programs and in the profession (Park et al., 2017), a comprehensive understanding of the current ICS literature is needed. This content analysis can identify how the research on ICSs has progressed and what remains unexplored or underexplored, which can provide meaningful implications for researchers interested in conducting ICS research in the future.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to identify major findings in literature recently published on ICSs in the United States and to draw useful implications for counseling researchers and counseling programs seeking to better understand and support international students in counseling programs. Our content analysis, which focused on ICS research published between 2006 and 2021 in selected counseling journals, was driven by the following research questions: 1) What are the publication trends in ICS research, such as prevalence, publication outlets, authorship, methodological design, and sample size and characteristics?; and 2) What is the content of the ICS research published in counseling journals? Based on the findings, this study aimed to suggest recommendations for counseling researchers to fill the scholarly gap in ICS research and for counselor education programs to provide more effective training experiences to their international trainees.

Method

Content analysis is a useful methodology to expand our knowledge and understanding of the field through an overview of the current literature (Stemler, 2001). This approach makes it possible to effectively summarize a large amount of data using a few categories or content areas. In counseling research, content analysis has been used to provide an overview of a profession that is underrepresented but with growing importance (e.g., LGBTQ; Singh & Shelton, 2011), which is aligned with the aim of this study. This study employed both quantitative and qualitative content analysis to provide an overview of ICS research. Quantitative content analysis refers to analyzing the data in mathematical ways and applying predetermined categories that do not derive from the data (Forman & Damschroder, 2007). After reviewing existing content analysis articles in the counseling field, Byeolbee Um and Susannah M. Wood determined the scope of our quantitative analysis as: (a) journal and authorship, (b) research design, (c) participant characteristics, and (d) data collection methods.

Research Team

The research team consisted of two doctoral candidates and one full professor, all of whom were affiliated with the same CACREP-accredited counselor education and supervision program at a Midwestern university. Um and Lindsay Woodbridge were doctoral candidates in counselor education and supervision when conducting this research project and are currently counselor educators. Um is an international scholar from an East Asian country. She has drawn on her experiences in quantitative and qualitative courses and research projects to engage in research of marginalized counseling students, including ICSs. Woodbridge is a domestic scholar who has taken classes and collaborated with international student peers and worked with international students in instructional and clinical capacities. She has taken quantitative and qualitative research courses and completed several research projects. The first and second authors met regularly to establish the scope of the investigation, collect data, and form a consensus on coding emerging categories and sorting them into themes. Wood, an experienced researcher and instructor, has worked as a counselor educator for more than 15 years. She has worked with international students in teaching, supervision, advising, and mentoring capacities. She audited the research process, reviewed emergent categories and themes, and provided constructive feedback at each phase of the study.

Data Collection

To identify a full list of ICS studies that satisfy the scope of this study, Um and Woodbridge independently performed electronic searches using research databases including EBSCO, PsycINFO, and ERIC. Because ICSs have attracted scholarly attention relatively recently and because Ng’s (2006) study that estimated the number of ICSs in CACREP-accredited programs was the first published research on ICSs in counselor education programs, we set 2006 as the initial year of our search. We used the following search criteria to identify candidate articles: (a) published between 2006 and 2021 in ACA division, branch, and state journals and major journals under the auspices of professional counseling organizations; (b) containing one or more of the following keywords: international students, international counseling students, international counseling trainees, international counseling programs, counselor education; and (c) involving original empirical findings from ICSs in the United States.

We conducted an extensive search of ICS research across various journals in the counselor education field and identified ICS articles from several ACA-related journals, including Counselor Education and Supervision (CES), Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development (JMCD), The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision (JCPS), The Journal for Specialists in Group Work (JSGW), and the Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research (JPC). Additionally, we found ICS articles from the International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling (IJAC) and the Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy (JCLA), which are associated with the International Association for Counselling and Chi Sigma Iota, respectively. Although they are not under the broader umbrella of ACA, these journals have contributed to enriching scholarship in the counseling field.

After the initial searches, Um and Woodbridge made a preliminary list of the articles identified based on the search results. Subsequently, they re-screened the articles independently. Among the 27 identified articles, we excluded five conceptual papers, three articles that examined counselors’ or counselor educators’ experiences after graduation, and one article about ICSs in Turkey. Consequently, the final data consisted of 18 articles published by seven selected counseling journals.

Data Analysis

The research team analyzed content areas of the ICS research as an extension of qualitative content analysis, which requires performing the systematical coding and identifying categories/themes (Cho & Lee, 2014). We followed a series of steps suggested by Downe-Wamboldt (1992), which included selecting the unit of analysis, developing and modifying categories, and coding data. Several methods were used to ensure the trustworthiness of this content analysis study (Kyngäs et al., 2020). For credibility, Um and Woodbridge conducted multiple rounds of review on determining an adequate unit of analysis and tracked all discussions and modifications in great detail. For dependability, we calculated interrater reliability coefficients and Wood provided feedback about the results. Um also secured confirmability by utilizing audit trails, which described the specific steps and reflections of the project. Finally, to support transferability, we carefully examined other content analysis articles, reflected core aspects in the current study, and depicted the research process transparently.

Coding Protocol

After completing the quantitative content analysis, we conducted the qualitative content analysis as Downe-Wamboldt (1992) suggested. In so doing, we applied the inductive category development process suggested by Mayring (2000), which features a systematic categorization process of identifying tentative categories, coding units, and extracting themes from established categories. Specifically, after discussing the research question and levels of abstraction for categories, Um and Woodbridge determined the preliminary categories based on the text of the 18 ICS articles. We practiced coding the data using two articles and then performed independent coding of the remaining articles. Using a constructivist approach, we agreed to add additional categories as needed. Subsequently, the categories were revised until we reached a consensus. In the final step, established categories were sorted into three themes to identify the latent meaning of qualitative materials (Cho & Lee, 2014; Forman & Damschroder, 2007). Regarding validity, the congruence between existing conceptual themes and results of data coding secures external validity, which is regarded as the purpose of content analysis (Downe-Wamboldt, 1992).

Interrater Reliability

We used various indices of interrater reliability to assess the overall congruence between the researchers who performed the qualitative analysis and ensure trustworthiness. In this study, we used the kappa statistic (κ) suggested by Cohen (1960), which shows the extent of consensus among raters for selecting an article or coding texts (Stemler, 2001). Cohen’s kappa has been used extensively across various academic fields to measure the degree of agreement between raters. More specifically, the kappa statistic was calculated in two phases: 1) after screening articles and 2) after coding the texts according to the categories. The kappa results between Um and Woodbridge were .68 for screening articles and .71 for coding the text, both of which are considered substantial (.61–.80; Stemler, 2004).

Results

Results of Quantitative Content Analysis

Based on our electronic search, we identified a total of 18 ICS articles published between 2006 and 2021 in seven selected counseling journals, including three ACA division journals, one ACA state-branch journal, one ACES regional journal, and two journals from professional counseling associations (see Table 1). Specifically, two articles were published in CES, three in JMCD, one in JCPS, one in JSGW, three in JPC, seven in IJAC, and one in JCLA. Across the 18 ICS articles, a total of 35 researchers were identified as authors or co-authors with six authoring more than one article. According to researchers’ positionality statements in qualitative articles, eight researchers reported that they were previous or current ICSs in the United States. The institutional affiliations of researchers include 22 U.S. universities and two international universities, with three institutional affiliations appearing more than once across the studies.

Table 1

Summary of International Counseling Student Research in Selected Counseling Journals Between 2006 and 2021

| Journal and Author |

Research Design |

Participants |

Data Collection |

Topic |

| Counselor Education and Supervision (CES) |

Behl et al.

(2017) |

Quantitative

(Pearson product-moment correlations) |

38 counseling master’s and doctoral students |

Online survey |

Stress related to acculturation and students’ language, academic, social, and cultural needs |

D. Li & Liu

(2020) |

Qualitative (Phenomenology) |

11 doctoral students |

Semi-structured interview |

ICSs’ experiences with teaching preparation |

| Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development (JMCD) |

Kuo et al.

(2021) |

Qualitative (Consensual

qualitative research) |

13 doctoral students |

Semi-structured interview |