Feb 26, 2021 | Volume 11 - Issue 1

Priscilla Rose Prasath, Peter C. Mather, Christine Suniti Bhat, Justine K. James

This study examined the relationships between psychological capital (PsyCap), coping strategies, and well-being among 609 university students using self-report measures. Results revealed that well-being was significantly lower during COVID-19 compared to before the onset of the pandemic. Multiple linear regression analyses indicated that PsyCap predicted well-being, and structural equation modeling demonstrated the mediating role of coping strategies between PsyCap and well-being. Prior to COVID-19, the PsyCap dimensions of optimism and self-efficacy were significant predictors of well-being. During the pandemic, optimism, hope, and resiliency have been significant predictors of well-being. Adaptive coping strategies were also conducive to well-being. Implications and recommendations for psychoeducation and counseling interventions to promote PsyCap and adaptive coping strategies in university students are presented.

Keywords: university students, psychological capital, well-being, coping strategies, COVID-19

In January 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of a new coronavirus disease, COVID-19, to be a public health emergency of international concern, and the effects continue to be widespread and ongoing. For university students, the pandemic brought about disruptions to life as they knew it. For example, students had to stay home, adapt to online learning, modify internship placements, and/or reconsider graduation plans and jobs. The aim of this study was to understand how the sudden changes and uncertainty resulting from the pandemic affected the well-being of university students during the early period of the pandemic. Specifically, the study addresses coping strategies and psychological capital (PsyCap; F. Luthans et al., 2007) and how they relate to levels of well-being.

University Students and Mental Health

Although mental health distress has been an issue on college campuses prior to the pandemic (Flatt, 2013; Lipson et al., 2019), COVID-19 has and will continue to magnify this phenomenon. Experts are projecting increases in depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide in the United States (Wan, 2020). Johnson (2020) indicated that 35% of students reported increased anxiety associated with a move from face-to-face to online learning in the spring 2020 semester, matching the early phases of the COVID-19 outbreak. Stress associated with adapting to online learning presented particular challenges for students who did not have adequate internet access in their homes (Hoover, 2020).

Researchers have reported that high levels of technology and social media use are associated with depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults (Huckins et al., 2020; Primack et al., 2017; Twenge, 2017). Given the current realities of physical distancing, there are fewer opportunities for traditional-age university students attending primarily residential campuses to maintain social connections, resulting in social fragmentation and isolation. Research has demonstrated that this exacerbates existing mental health concerns among university students (Klussman et al., 2020).

The uncertainties arising from COVID-19 have added to anticipatory anxiety regarding the future (Ray, 2019; Witters & Harter, 2020). From the Great Depression to 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, victims of these life-shattering events have had to deal with their present circumstances and were also left with worries about how life and society would be inexorably altered in the future. University students are dealing with uncertain current realities and futures and may need to bolster their internal resources to face the challenges ahead. In this context, positive coping strategies and PsyCap may be increasingly valuable assets for university students to address the psychological challenges associated with this pandemic and to maintain or enhance their well-being.

Coping Strategies

Coping is often defined as “efforts to prevent or diminish the threat, harm, and loss, or to reduce associated distress” (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010, p. 685). There are many ways to categorize coping responses (e.g., engagement coping and disengagement coping, problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping, accommodative coping and meaning-focused coping, proactive coping). Engagement coping includes problem-focused coping and some forms of emotion-focused coping, such as support seeking, emotion regulation, acceptance, and cognitive restructuring. Disengagement coping includes responses such as avoidance, denial, and wishful thinking, as well as aspects of emotion-focused coping, because it involves an attempt to escape feelings of distress (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010; de la Fuente et al., 2020). Findings on the effectiveness of problem-focused coping strategies versus emotion-focused coping strategies suggest the effectiveness of the particular strategy is contingent on the context, with controllable issues being better addressed through problem-focused strategies, while emotion-focused strategies are more effective with circumstances that cannot be controlled (Finkelstein-Fox & Park, 2019). In general, problem-focused coping strategies, also known as adaptive coping strategies, include planning, active coping, positive reframing, acceptance, and humor (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Other coping strategies, such as denial, self-blame, distraction, and substance use, are more often associated with negative emotions, such as shame, guilt, lower perception of self-efficacy, and psychological distress, rather than making efforts to remediate them (Billings & Moos, 1984). These strategies can be harmful and unhealthy with regard to effectively coping with stressors. Researchers have recommended coping skills training for university students to modify maladaptive coping strategies and enhance pre-existing adaptive coping styles to optimal levels (Madhyastha et al., 2014).

Flourishing: The PERMA Well-Being Model

Positive psychologists have asserted that studies of wellness and flourishing are important in understanding adaptive behaviors and the potential for growth from challenging circumstances (Joseph & Linley, 2008; Seligman, 2011). Flourishing (or well-being) is defined as “a dynamic optimal state of psychosocial functioning that arises from functioning well across multiple psychosocial domains” (Butler & Kern, 2016, p. 2). Seligman (2011) proposed a theory of well-being stipulating that well-being was not simply the absence of mental illness (Keyes, 2002), but also the presence of five pillars with the acronym of PERMA (Seligman, 2002, 2011). The first pillar, positive emotion (P), is the affective component comprising the feelings of joy, hope, pleasure, rapture, happiness, and contentment. Next are engagement (E), the act of being highly interested, absorbed, or focused in daily life activities, and relationships (R), the feelings of being cared about by others and authentically and securely connected to others. The final two pillars are meaning (M), a sense of purpose in life that is derived from something greater than oneself, and accomplishment (A), a persistent drive that helps one progress toward personal goals and provides one with a sense of achievement in life. Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model is one of the most highly regarded models of well-being.

Seligman’s multidimensional model integrates both hedonic and eudaimonic views of well-being, and each of the well-being components is seen to have the following three properties: (a) it contributes to well-being, (b) it is pursued for its own sake, and (c) it is defined and measured independently from the other components (Seligman, 2011). Studies show that all five pillars of well-being in the PERMA model are associated with better academic outcomes in students, such as improved college life adjustment, achievement, and overall life satisfaction (Butler & Kern, 2016; DeWitz et al., 2009; Tansey et al., 2018). Additionally, each pillar of PERMA has been shown to be positively associated with physical health, optimal well-being, and life satisfaction and negatively correlated with depression, fatigue, anxiety, perceived stress, loneliness, and negative emotion (Butler & Kern, 2016). At a time of significant stress, promoting the highest human performance and adaptation not only helps with well-being in the midst of the challenge but also can provide a foundation for future potential for optimal well-being (Joseph & Linley, 2008).

Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

PsyCap is a state-like construct that consists of four dimensions: hope (H), self-efficacy (E), resilience (R), and optimism (O), often referred to by the acronym HERO (F. Luthans et al., 2007). F. Luthans et al. (2007) developed PsyCap from research in positive organizational behavior and positive psychology. PsyCap is defined as an

individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by (1) having confidence (self-efficacy) to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at challenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism) about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering toward goals and, when necessary, redirecting paths to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and (4) when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond (resilience) to attain success. (F. Luthans et al., 2015, p. 2)

Over the past decade, PsyCap has been applied to university student development and mental health. There is robust empirical support suggesting that individuals with higher PsyCap have higher levels of performance (job and academic); satisfaction; engagement; attitudinal, behavioral, and relational outcomes; and physical and psychological health and well-being outcomes. Further, they have negative associations with stress, burnout, negative health outcomes, and undesirable behaviors at the individual, team, and organizational levels (Avey, Reichard, et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2014). Researchers have also examined the mediating role of PsyCap in the relationship between positive emotion and academic performance (Carmona-Halty et al., 2019; Hazan Liran & Miller, 2019; B. C. Luthans et al., 2012; K. W. Luthans et al., 2016); relationships and predictions between PsyCap and mental health in university students (Selvaraj & Bhat, 2018); and relationships between PsyCap, well-being, and coping (Rabenu et al., 2017).

Aim of the Study and Research Questions

The aim of the current study was to examine the relationships among well-being in university students before and during the onset of COVID-19 with PsyCap and coping strategies. The following research questions guided our work:

- Is there a significant difference in the well-being of university students prior to the onset of COVID-19 (reported retrospectively) and after the onset of COVID-19?

- What is the predictive relationship of PsyCap on well-being prior to the onset of COVID-19 and after the onset of COVID-19?

- Do coping strategies play a mediating role in the relationship between PsyCap and well-being?

Method

Participants

A total of 806 university students from the United States participated in the study. After cleaning the data, 197 surveys were excluded from the data analyses. Of the final 609 participants, 73.7% (n = 449) identified as female, 22% (n = 139) identified as male, and 4.3% (n = 26) identified as non-binary. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 66 (M = 27.36, SD = 9.9). Regarding race/ethnicity, most participants identified as Caucasian (83.6%, n = 509), while the remaining participants identified as African American (5.3%, n = 32), Hispanic or Latina/o (9.5%, n = 58), American Indian (0.8%, n = 5), Asian (3.6%, n = 22), or Other (2.7%, n = 17). Fifty-four percent of the participants were undergraduate students (n = 326), and the remaining 46% were graduate students (n = 283). The majority of the participants were full time students (82%, n = 498) compared to part-time students (18%, n = 111). Sixty-three percent of the students were employed (n = 384) and the remaining 37% were unemployed (n = 225).

Data Collection Procedures

After a thorough review of the literature, three standardized measures were identified for use in the study along with a brief survey for demographic information. Instruments utilized in the study measured psychological capital (Psychological Capital Questionnaire [PCQ-12]; Avey, Avolio et al., 2011), coping (Brief COPE; Carver, 1997), and well-being (PERMA-Profiler; Butler & Kern, 2016). Data were collected online in May and June 2020 using Qualtrics after obtaining approval from the IRBs of our respective universities. An invitation to participate, which included a link to an informed consent form and the survey, was distributed to all university students at two large U.S. public institutions in the Midwest and the South via campus-wide electronic mailing lists. The survey link was also distributed via a national counselor education listserv, and it was shared on the authors’ social media platforms. Participants were asked to complete the well-being assessment twice—first, by responding as they recalled their well-being prior to COVID-19, and second, by responding as they reflected on their well-being during the pandemic.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

A brief questionnaire was used to capture participant information. The questionnaire included items related to age, gender, race/ethnicity, relationship status, education classification, and employment status.

Psychological Capital Questionnaire – Short Version (PCQ-12)

The PCQ-12 (Avey, Avolio et al., 2011), the shortened version of PCQ-24 (F. Luthans et al., 2007), consists of 12 items that measure four HERO dimensions: hope (four items), self-efficacy (three items), resilience (three items), and optimism (two items), together forming the construct of psychological capital (PsyCap). The PCQ-12 utilizes a 6-point Likert scale with response options ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients as a measure of internal consistency of the HERO subscales in the current study were high—hope (α = .86), self-efficacy (α = .86), resilience (α = .73), and optimism (α = .83)—consistent with the previous studies.

Brief COPE Questionnaire

Coping strategies were evaluated using the Brief COPE questionnaire (Carver, 1997), which is a short form (28 items) of the original COPE inventory (Carver et al., 1989). The Brief COPE is a multidimensional inventory used to assess the different ways in which people generally respond to stressful situations. This instrument is used widely in studies with university students (e.g., Madhyastha et al., 2014; Miyazaki et al., 2008). Fourteen conceptually differentiable coping strategies are measured by the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997): active coping, planning, using emotional support, using instrumental support, venting, positive reframing, acceptance, denial, self-blame, humor, religion, self-distraction, substance use, and behavioral disengagement. The 14 subscales may be broadly classified into two types of responses—“adaptive” and “problematic” (Carver, 1997, p. 98). Each subscale is measured by two items and is assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. Thus, in general, internal consistency reliability coefficients tend to be relatively smaller (α = .5 to .9).

PERMA-Profiler

The PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016) is a 23-item self-report measure that assesses the level of well-being across five well-being domains (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment) and additional subscales that measure negative emotion, loneliness, and physical health. Each item is rated on an 11-point scale ranging from never (0) to always (10), or not at all (0) to completely (10). The five pillars of well-being are defined and measured separately but are correlated constructs that together are considered to result in flourishing (Seligman, 2011). A single overall flourishing score provides a global indication of well-being, and at the same time, the domain-specific PERMA scores provide meaningful and practical benefits with regard to the possibility of targeted interventions. The measure demonstrates acceptable reliability, cross-time stability, and evidence for convergent and divergent validity (Butler & Kern, 2016). For the present study, reliability scores were high for four pillars—positive emotion (α = .88), relationships (α = .83), meaning (α = .89), accomplishment (α = .82); high for the subscales of negative emotion (α = .73) and physical health (α = .85); and moderate for the pillar of engagement (α = .65). The overall reliability coefficient of well-being items is very high (α = .94).

Data Analysis Procedure

The data were screened and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, v25). Changes in PERMA elements were calculated by subtracting PERMA scores reported retrospectively by participants before the pandemic from scores reported at the time of data collection during COVID-19, and a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the difference. Point-biserial correlation and Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships of demographic variables, PsyCap, and coping strategies with change in PERMA scores. Multivariate multiple regression was carried out to understand the predictive role of PsyCap on PERMA at two time points (before and during COVID-19). Structural equation modeling in Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS, v23) software was used to test the mediating role of coping strategies on the relationship between PsyCap and change in PERMA scores. Mediation models were carried out with bootstrapping procedure with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Prior to exploring the role of PsyCap and coping strategies on change in well-being due to COVID-19, an initial analysis was conducted to understand the characteristics and relationships of constructs in the study. Correlation analyses (see Table 1) revealed significant and positive correlations between four PsyCap HERO dimensions (i.e., hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism; Avey, Avolio et al., 2011) and the six PERMA elements (i.e., positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment, and physical health; Butler & Kern, 2016). Further, PsyCap HERO dimensions were negatively correlated to negative emotion and loneliness. Age was positively correlated with change in PERMA elements, but not gender. Similarly, approach coping strategies such as active coping, positive reframing, and acceptance (Carver, 1997) were resilient strategies to handle pandemic stress whereas using emotional support and planning showed weaker but significant roles. Similarly, religion also tended to be an adaptive coping strategy during the pandemic. Behavioral disengagement and self-blame (Carver, 1997) were found to be the dominant avoidant coping strategies that were adopted by students, which led to a significant decrease in well-being during the pandemic. Overall, as seen in Table 1, all three variables studied—PsyCap HERO dimensions, eight PERMA elements, and coping strategies—were highly related.

Table 1

Relationship of Demographic Factors, Psychological Capital, and Coping Strategies With Change in PERMA Elements

| Variables |

Mean |

SD |

P |

E |

R |

M |

A |

N |

H |

L |

| Age |

27.36 |

9.91 |

.15** |

.11** |

.14** |

.16** |

.14** |

.01 |

.03 |

-.17** |

| Course Ф |

– |

– |

.19** |

.10* |

.19** |

.16** |

.06 |

-.05 |

.09* |

-.14** |

| Nature of course Ф |

– |

– |

.06 |

.06 |

.12** |

.13** |

.09* |

.03 |

.03 |

-.10** |

| Gender Ф |

– |

– |

-.01 |

-.06 |

.01 |

-.02 |

-.02 |

.02 |

-.02 |

.03 |

| Employment Ф |

– |

– |

-.17** |

-.11** |

-.13** |

-.19** |

-.10* |

.04 |

-.11** |

.11** |

| Self-Efficacy |

13.80 |

3.21 |

.11** |

.13** |

.14** |

.18** |

.16** |

-.05 |

.15** |

-.03 |

| Hope |

18.68 |

3.92 |

.24** |

.26** |

.20** |

.34** |

.40** |

-.17** |

.21** |

-.10* |

| Resilience |

13.41 |

3.08 |

.23** |

.22** |

.20** |

.32** |

.33** |

-.16** |

.15** |

-.13** |

| Optimism |

8.61 |

2.39 |

.21** |

.27** |

.23** |

.32** |

.30** |

-.11** |

.16** |

-.10* |

| Self-Distraction |

6.32 |

1.41 |

-.09* |

.01 |

.03 |

-.02 |

.01 |

.08* |

.02 |

.11** |

| Active Coping |

5.83 |

2.01 |

.24** |

.28** |

.20** |

.28** |

.32** |

-.09* |

.23** |

-.08* |

| Denial |

2.96 |

1.42 |

-.19** |

-.14** |

-.18** |

-.16** |

-.16** |

.24** |

-.16** |

.12** |

| Substance Use |

3.60 |

2.02 |

-.18** |

-.15** |

-.15** |

-.20** |

-.20** |

.11** |

-.09* |

.17** |

| Using Emotional Support |

5.07 |

1.81 |

.12** |

.11** |

.32** |

.18** |

.11** |

.04 |

.10* |

-.02 |

| Using Instrumental Support |

4.35 |

1.70 |

.01 |

.04 |

.20** |

.07 |

.02 |

.10* |

.04 |

.07 |

| Behavioral Disengagement |

3.96 |

2.11 |

-.43** |

-.37** |

-.40** |

-.46** |

-.44** |

.31** |

-.26** |

.27** |

| Venting |

4.58 |

1.54 |

-.24** |

-.16** |

-.08* |

-.17** |

-.16** |

.29** |

-.09* |

.16** |

| Positive Reframing |

5.12 |

1.78 |

.28** |

.27** |

.21** |

.26** |

.25** |

-.15** |

.18** |

-.14** |

| Planning |

5.42 |

1.75 |

.07 |

.12** |

.11** |

.13** |

.11** |

.08 |

.08* |

-.04 |

| Humor |

4.93 |

2.00 |

-.02 |

-.02 |

-.02 |

-.04 |

-.06 |

-.02 |

.02 |

.05 |

| Acceptance |

6.47 |

1.43 |

.33** |

.27** |

.27** |

.34** |

.31** |

-.25** |

.21** |

-.15** |

| Religion |

3.93 |

2.03 |

.21** |

.16** |

.16** |

.22** |

.13** |

-.08 |

.15** |

-.05 |

| Self-Blame |

4.08 |

1.72 |

-.33** |

-.27** |

-.29** |

-.36** |

-.36** |

.29** |

-.22** |

.20** |

Note. P = Positive Emotion, E = Engagement, R = Relationships, M = Meaning, A = Accomplishment, N = Negative Emotion, H = Physical Health, L = Loneliness.

Ф Point-biserial correlation

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Research Question 1

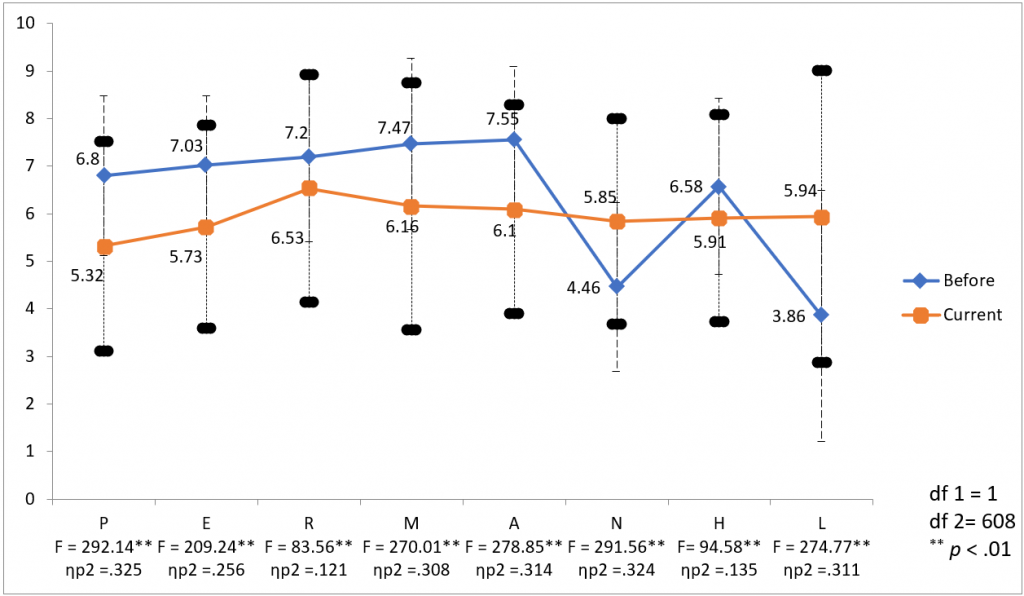

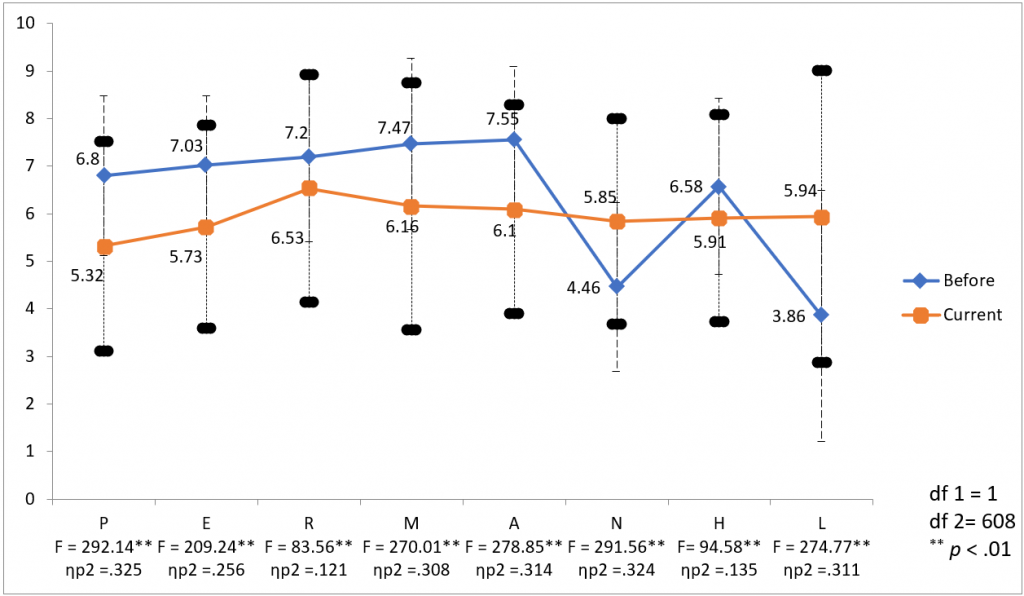

Results of a repeated-measures ANOVA presented in Figure 1 indicate that mean scores of PERMA decreased significantly during COVID-19: λ = .620; F (5,604) = 73.99, p < .001. Partial eta squared was reported as the measure of effect size. The effect size of the change in well-being for PERMA elements was 38%, ηp2 = .380, a high effect size (Cohen, 1988). As expected, negative emotion and loneliness significantly increased during the period of COVID-19, impacting overall well-being in an adverse manner. The average scores of negative emotion and loneliness increased from 4.46 and 3.86 to 5.85 and 5.94, respectively. Physical health significantly reduced from 6.58 to 5.91. The effect size of the change in the scores of individual PERMA elements ranged between 12.1% and 32.5%. Among the PERMA elements, engagement and physical health were least impacted by COVID-19, whereas students’ experiences of positive emotion and negative emotion were the factors that were largely affected.

Figure 1

Changes in the PERMA Prior to the Onset of COVID-19 and After the Onset of COVID-19

Note. P = Positive Emotion, E = Engagement, R = Relationships, M = Meaning, A = Accomplishment, N = Negative Emotion, H = Physical Health, L = Loneliness.

Research Question 2

The predictive role of PsyCap on well-being at two time points (before and after the onset of COVID-19) was analyzed using multivariate multiple regression (see Table 2). Coefficients of determination for models predicting well-being from PsyCap dimensions ranged from 4% to 28%. Before the onset of COVID-19, 23% of the variance in well-being was explained by the PsyCap dimensions (R2 = .23, p < .001), with self-efficacy and optimism as the most significant predictors of well-being. However, during the pandemic, the covariance of the PsyCap dimensions with well-being increased to 39% (R2 = .39, p < .01). Interestingly, after the onset of the pandemic, the predictor role of certain PsyCap dimensions shifted. For example, optimism became the strongest predictor of overall well-being and hope emerged as a predictor of engagement, meaning, accomplishment, and physical health during the pandemic. The predictive role of hope was negligible before COVID-19. The predictive role of resilience on positive emotion, accomplishment, negative emotion, and loneliness also became significant during COVID-19. Self-efficacy was a consistent predictor of PERMA elements before COVID-19. But during COVID-19, the relevance of self-efficacy in predicting PERMA elements was limited to controllable factors—relationships, meaning, and physical health—and the predictive role of self-efficacy overall was no longer significant (see Table 2).

Table 2

Predicting PERMA Elements From Psychological Capital Prior to the Onset of COVID-19 and After the Onset of COVID-19

|

PERMA |

Self-Efficacy |

Hope |

Resilience |

Optimism |

Adj. R2 |

F |

| Before COVID-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive Emotion |

.10* |

-.06 |

-.01 |

.44** |

.19 |

37.66** |

| Engagement |

.10* |

.06 |

.01 |

.11* |

.05 |

8.80** |

| Relationships |

.10* |

.07 |

-.09 |

.29** |

.12 |

21.33** |

| Meaning |

.21** |

.06 |

-.03 |

.38** |

.28 |

58.68** |

| Accomplishment |

.24** |

.06 |

.04 |

.13* |

.14 |

25.62** |

| Negative Emotion |

-.13** |

.10 |

-.05 |

-.29** |

.11 |

18.97** |

| Physical Health |

.16** |

.08 |

-.04 |

.12* |

.07 |

12.16** |

| Loneliness |

-.10* |

0 |

-.01 |

-.19** |

.04 |

7.36** |

| Well-Being |

.19** |

.04 |

-.02 |

.35** |

.23 |

45.41** |

| During COVID-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Positive Emotion |

.04 |

.09 |

.10* |

.41** |

.30 |

67.05** |

| Engagement |

.02 |

.21** |

.05 |

.26** |

.21 |

40.86** |

| Relationships |

.09* |

.1 |

-.01 |

.33** |

.19 |

36.72** |

| Meaning |

.11** |

.18** |

.09 |

.38** |

.39 |

99.93** |

| Accomplishment |

.05 |

.37** |

.14** |

.17** |

.39 |

96.96** |

| Negative Emotion |

-.03 |

-.07 |

-.13* |

-.23** |

.14 |

26.80** |

| Physical Health |

.16** |

.19** |

-.03 |

.14** |

.15 |

27.25** |

| Loneliness |

-.04 |

.01 |

-.11* |

-.20** |

.08 |

13.34** |

| Well-Being |

.07 |

.22** |

.08 |

.37** |

.39 |

97.48** |

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Research Question 3

Structural equation modeling was used to examine whether coping strategies mediate PsyCap’s effect on well-being. Coping strategies that predicted change in PERMA were used for mediation analysis. Indirect effects describing pathways from PsyCap factors to PERMA factors through identified coping strategies were tested for mediating roles. Results indicated that PsyCap affected well-being both directly and indirectly through coping strategies. Optimism had a significant indirect effect on change in well-being compared to hope and resilience (see Table 3). Among adaptive coping strategies, active coping, positive reframing, and using emotional support mediated the relationship between optimism and overall well-being. Interestingly, using emotional support also showed a similar mediating link between resilience and PERMA, but not for the factors of loneliness and negative emotion. On the other hand, self-blame and behavioral disengagement were two problematic coping strategies that mediated the relationship between optimism and all PERMA elements. Specifically, we found coping through self-blame playing a mediating role between PERMA factors and two of the HERO dimensions—resilience and hope.

Table 3

Indirect Effect of Psychological Capital on PERMA Factors Through Coping Strategies (Mediators)

| PsyCap |

Standardized Beta (ß, Indirect effect) |

| L |

H |

N |

A |

M |

R |

E |

P |

| Active Coping Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.016* |

.043** |

-.017* |

.06** |

.052** |

.037** |

.052** |

.044** |

|

Resilience |

-.005 |

.014 |

-.006 |

.02 |

.017 |

.012 |

.017 |

.015 |

|

Hope |

-.007 |

.018 |

-.007 |

.025 |

.022 |

.015 |

.022 |

.018 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.009 |

.025 |

-.01 |

.034 |

.03 |

.021 |

.03 |

.025 |

| Positive Reframing Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.047** |

.06** |

-.05** |

.085** |

.088** |

.07** |

.094** |

.096** |

|

Resilience |

-.005 |

.007 |

-.006 |

.01 |

.01 |

.008 |

.011 |

.011 |

|

Hope |

.003 |

-.003 |

.003 |

-.005 |

-.005 |

-.004 |

-.005 |

-.005 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.005 |

.006 |

-.005 |

.009 |

.009 |

.007 |

.01 |

.01 |

| Using Emotional Support Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.007 |

.02* |

.012 |

.03* |

.049** |

.086** |

.029* |

.032** |

|

Resilience |

.003 |

-.012 |

-.005 |

-.013* |

-.021* |

-.037* |

-.012* |

-.014* |

|

Hope |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.001 |

.006 |

.002 |

.006 |

.01 |

.018 |

.006 |

.007 |

| Self-Blame Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.038** |

.043** |

-.056** |

.07** |

.07** |

.056** |

.054** |

.065** |

|

Resilience |

-.03** |

.034** |

-.044** |

.055** |

.055** |

.044** |

.042** |

.051** |

|

Hope |

-.023* |

.025* |

-.033* |

.042* |

.041* |

.033* |

.032* |

.038** |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.005 |

.006 |

-.007 |

.009 |

.009 |

.007 |

.007 |

.008 |

| Behavioral Disengagement Ф |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optimism |

-.07** |

.067** |

-.081** |

.113** |

.118** |

.104** |

.097** |

.112** |

|

Resilience |

-.02 |

.02 |

-.023 |

.033 |

.034 |

.03 |

.028 |

.033 |

|

Hope |

-.032 |

.03 |

-.036 |

.051 |

.053 |

.047 |

.044 |

.051 |

|

Self-Efficacy |

-.009 |

.009 |

-.011 |

.015 |

.016 |

.014 |

.013 |

.015 |

Note. Coping strategies with insignificant mediating role are not included in the table. P = Positive Emotion,

E = Engagement, R = Relationships, M = Meaning, A = Accomplishment, N = Negative Emotion, H = Physical Health,

L = Loneliness.

Ф Mediator coping strategies.

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Discussion

The current study investigated the PERMA model of well-being (Seligman, 2011) with university students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the relationships between PsyCap (F. Luthans et al., 2007), coping strategies, and well-being of university students. We examined whether the COVID-19 context shaped the efficacy of particular strategies to promote well-being. Findings are discussed in three areas: reduction in well-being related to COVID-19, shift in predictive roles of PsyCap HERO dimensions, and coping strategies as a mediator.

Reduction in Well-Being Related to COVID-19

Well-being scores across all PERMA elements, including physical health, were lower than those reported retrospectively prior to the pandemic. Such a decline in well-being following a pandemic is consistent with previous occurrences of public health crises or natural disasters (Deaton, 2012). Participants reported higher levels of negative emotion and loneliness after the onset of COVID-19, and a decrease in positive emotion. It is this balance of positive and negative emotions that contributes to life satisfaction (Diener & Larsen, 1993), and our findings support the notion that fostering particular positive psychological states (PsyCap), as well as engaging in related coping strategies, promotes well-being in the context of this large-scale crisis.

Shift in Predictive Roles of PsyCap HERO Dimensions

Consistent with prior research (Avey, Reichard et al., 2011; F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017; Youssef-Morgan & Luthans, 2015), we found that PsyCap predicted well-being. PsyCap’s positive psychological resources (HERO dimensions) may enable students to have a “positive appraisal of circumstances” (F. Luthans et al., 2007, p. 550) by providing mechanisms for reframing and reinterpreting potentially negative or neutral situations. There was however an interesting shift in the predictive role of PsyCap dimensions before and after the onset of COVID-19. Prior to COVID-19, self-efficacy and optimism were the two major psychological resources that predicted university student well-being. However, after COVID-19, self-efficacy did not present as a predictor of well-being in this study. Although the reason for this result is uncertain, it is conceivable that attending to an uncertain future (i.e., hope) and recovering from immediate losses (i.e., resilience) became more salient, and one’s self-efficacy in managing normal, everyday challenges receded in importance. Indeed, optimism and hope each uniquely predict a major proportion of variance of the change in well-being and may together help students to face an uncertain future (M. W. Gallagher & Lopez, 2009). Resilience, the ability to recover from setbacks when pathways are blocked (Masten, 2001), had a predictive role on positive emotion and accomplishment in this study.

Coping Strategies as a Mediator

While PsyCap directly relates to well-being and coping strategies relate to well-being, our findings indicated that coping strategies also played a significant mediating role in the relationship between PsyCap and well-being. Specifically, adaptive coping strategies played a significant role in enhancing the positive effects of PsyCap on well-being. Adaptive coping strategies—such as active coping, acceptance, using emotional support, and positive reframing—were found to better aid in predicting well-being. In this study, accepting the realities, using alternative affirmative explanations, seeking social support for meeting emotional needs, and engaging in active problem-focused coping behaviors seem to be the most helpful ways to counter the negative effects of the pandemic on well-being. Conversely, when individuals employed problematic coping strategies such as behavioral disengagement and self-blame (Carver, 1997), the negative impacts were much stronger than the positive effect of adaptive coping strategies.

Implications for Counselors

Given findings of the relationship between PsyCap and well-being in the current study, as well as in prior research (F. Luthans et al., 2006; F. Luthans et al., 2015; McGonigal, 2015), counselors may wish to focus on developing PsyCap to help university students flourish both during the pandemic and in a post-pandemic world. Two significant challenges to counseling professionals on college campuses are the lack of resources to adequately respond to mental health concerns among students and the stigma associated with accessing services (R. P. Gallagher, 2014; Michaels et al., 2015). Thus, efficient interventions that are not likely to trigger stigma responses are helpful in this context. Several researchers have found that relatively short training in PsyCap interventions, including web-based platforms (Dello Russo & Stoykova, 2015; Demerouti et al., 2011; Ertosun et al., 2015; B. C. Luthans et al., 2012, 2013) have been effective. Recently, the use of positive psychology smartphone apps such as Happify and resilience-building video games such as SuperBetter have been suggested and tested as motivational tools, especially with younger adults, to foster sustained and continued engagement with PsyCap development (F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017; McGonigal, 2015). These are potential areas of practice for college counselors and counselors serving university students.

Interventions that are described as well-being approaches rather than those that highlight pathologies are less stigmatizing (Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010; Umucu et al., 2020) than traditional deficit-based therapeutic approaches. There are a number of research-based approaches offered in the field of positive psychology to guide mental health professionals to facilitate development of PsyCap and other important well-being correlates. These include approaches to building positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2009); coping strategies, which were found in this study to boost well-being (Jardin et al., 2018; Lyubomirsky, 2008); and effective goal pursuits (F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017). One of the distinguishing characteristics of PsyCap is its malleability and openness to change and development (Avey, Reichard et al., 2011; F. Luthans et al., 2006). Thus, there is potential for counselors to develop well-being promotion initiatives for students on university campuses targeting PsyCap and its constituting positive psychological HERO resources with the end goal of strengthening well-being (Avey, Avolio et al., 2011; F. Luthans et al., 2015; F. Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017).

Strategies and programming to develop wellness can be delivered in one-on-one sessions with students, as well as in group settings, and may have either a prevention or intervention focus. They could also be adapted to provide services online. A variety of free online assessments are also available for use by counselors, including tools that measure well-being, positive psychological resources, and character strengths of university students in addition to existing assessment batteries. By administering the PERMA-Profiler to university students, counselors could identify and understand what dimension of well-being should be further developed (Umucu et al., 2020). With each PERMA element individually rendering to flourishing mental health, specific targeted positive psychology interventions might be offered as domain-specific interventions.

Counselors could help university students benefit from attending to, appreciating, and attaining life’s positives (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009) and from enhancing the strength and frequency of employing positive coping strategies through targeted psychoeducational or counseling interventions. Teaching university students active coping strategies, such as positive reframing and how to access emotional support, could help them cope with adverse situations. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2006) indicated that practicing gratitude helps people to cope with negative situations because it enables them to view such situations through a more positive lens. Among university students, healthy coping strategies could buffer them from some of the unique challenges associated with acculturating and adjusting to college experiences (Jardin et al., 2018), especially during a pandemic.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The findings of this study should be considered in light of certain limitations. Foremost among these is that data were collected using self-report measures, and in the case of the PERMA-Profiler, data were collected using the retrospective recall of participants as they considered their well-being prior to the onset of COVID-19. Retrospective recall may be inaccurate (Gilbert, 2007) with participants under- or overestimating their well-being. Given the ongoing repercussions of the pandemic, we recommend continued and longitudinal studies on well-being, coping strategies, and PsyCap. Additionally, data collection methods and sample demographics would likely limit generalizability. We utilized a correlational cross-sectional study design; therefore, although PsyCap was predictive of change in well-being before and during COVID-19, neither causation nor directionality can be assumed. In future, researchers may wish to investigate whether PsyCap predicts longitudinal changes in well-being in the COVID-19 context.

A further consideration is that the PERMA model of well-being (Seligman, 2011) may not be associated with similar outcomes for people of other cultures and backgrounds during COVID-19. Future researchers examining well-being in university students in different regions of the country or internationally may wish to further investigate the applicability of the PERMA model as a measure of university students’ well-being during the pandemic. Finally, the moderate Cronbach’s alpha reliability scores of < .70 (Field, 2013) for the subscales of the Brief COPE inventory and the engagement subscale of the PERMA-Profiler are of concern, which has also been expressed by prior researchers (Goodman et al., 2018; Iasiello et al., 2017). Future researchers should consider issues of internal consistency as they choose scales and interpret results.

Conclusion

To conclude, the present findings contribute to existing literature on PsyCap and well-being, using the PERMA model of well-being (Seligman, 2011) among university students in the United States in the context of COVID-19. Key findings are that the optimism, hope, and resilience dimensions of PsyCap are significant predictors of well-being, explaining a large amount of variance, with adaptive coping being conducive to flourishing. Further, the present findings highlight the importance of examining the relationships between each element of well-being and with each HERO dimension. Both individual counseling and group-based programming focused on PsyCap and positive coping strategies could support the well-being of university students as they experience ongoing stressors related to the pandemic or as they face other setbacks.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., & Luthans, F. (2011). Experimentally analyzing the impact of leader positivity on follower positivity and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(2), 282–294.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.02.004

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20070

Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1984). Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 877–891. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.877

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Carmona-Halty, M., Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2019). Good relationships, good performance: The mediating role of psychological capital: A three-wave study among students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00306

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 679–704.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

de la Fuente, J., Lahortiga-Ramos, F., Laspra-Solis, C., Maestro-Martin, C., Alustiza, I., Auba, E., & Martin-Lanas, R. (2020). A structural equation model of achievement emotions, coping strategies and engagement-burnout in undergraduate students: A possible underlying mechanism in facets of perfectionism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062106

Deaton, A. (2012). The financial crisis and the well-being of Americans: 2011 OEP Hicks lecture. Oxford Economic Papers, 64(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpr051

Dello Russo, S., & Stoykova, P. (2015). Psychological capital intervention (PCI): A replication and extension. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 26(3), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21212

Demerouti, E., van Eeuwijk, E., Snelder, M., & Wild, U. (2011). Assessing the effects of a “personal effectiveness” training on psychological capital, assertiveness and self-awareness using self-other agreement. The Career Development International, 16(1), 60–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431111107810

DeWitz, S. J., Woolsey, M. L., & Walsh, W. B. (2009). College student retention: An exploration of the relationship between self-efficacy beliefs and purpose in life among university students. Journal of College Student Development, 50(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0049

Diener, E., & Larsen, R. J. (1993). The experience of emotional wellbeing. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 405–415). Guilford.

Ertosun, Ö. G., Erdil, O., Deniz, N., & Alpkan, L. (2015). Positive psychological capital development: A field study by the Solomon four group design. International Business Research, 8(10), 102–111.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v8n10p102

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. SAGE.

Finkelstein-Fox, L., & Park, C. L. (2019). Control-coping goodness-of-fit and chronic illness: A systematic review of the literature. Health Psychology Review, 13(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2018.1560229

Flatt, A. K. (2013). A suffering generation: Six factors contributing to the mental health crisis in North American higher education. College Quarterly, 16(1).

Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity: Groundbreaking research reveals how to embrace the hidden strength of positive emotions, overcome negativity, and thrive. Crown.

Gallagher, M. W., & Lopez, S. J. (2009). Positive expectancies and mental health: Identifying the unique contributions of hope and optimism. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 548–556.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903157166

Gallagher, R. P. (2014). National Survey of College Counseling Centers 2014. International Association of Counseling Services, Inc. http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/28178

Gilbert, D. (2007). Stumbling on happiness. Random House.

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., & Kauffman, S. B. (2018). Measuring well-being: A comparison of subjective well-being and PERMA. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(4), 321–332.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1388434

Hazan Liran, B., & Miller, P. (2019). The role of psychological capital in academic adjustment among university students. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 20(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9933-3

Hoover, E. (2020). Distanced learning. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/distanced-learning

Huckins, J. F., DaSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E. I.,

Meyer, M. L., Wagner, D. D., Holtzheimer, P. E., & Campbell, A. T. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e20185.

https://doi.org/10.2196/20185

Hunt, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008

Iasiello, M., Bartholomaeus, J., Jarden, A., & Kelly, G. (2017). Measuring PERMA+ in South Australia, the State of Wellbeing: A comparison with national and international norms. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 1(2), 53–72.

Jardin, C., Mayorga, N. A., Bakhshaie, J., Garey, L., Viana, A. G., Sharp, C., Cardoso, J. B., & Zvolensky, M. J.

(2018). Clarifying the relation of acculturative stress and anxiety/depressive symptoms: The role of anxiety sensitivity among Hispanic college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000175

Johnson, R. (2020). Students stressed out due to coronavirus, new survey finds. Best Colleges (April 20, 2020).

https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/coronavirus-survey

Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (Eds.). (2008). Trauma, recovery, and growth: Positive psychological perspectives on posttraumatic stress. Wiley.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Klussman, K., Nichols, A. L., Langer, J., & Curtin, N. (2020). Connection and disconnection as predictors of mental health and wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i2.855

Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60–63.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800332

Luthans, B. C., Luthans, K. W., & Avey, J. B. (2013). Building the leaders of tomorrow: The development of academic psychological capital. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(2), 191–199.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051813517003

Luthans, B. C., Luthans, K. W., & Jensen, S. M. (2012). The impact of business school students’ psychological capital on academic performance. The Journal of Education for Business, 87(5), 253–259.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.609844

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M., & Combs, G. M. (2006). Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(3), 387–393.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.373

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 339–366.

Luthans, F., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2015). Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford University Press.

Luthans, K. W., Luthans, B. C., & Palmer, N. F. (2016). A positive approach to management education: The relationship between academic PsyCap and student engagement. Journal of Management Development, 35(9), 1098–1118. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-06-2015-0091

Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). The how of happiness: A scientific approach to getting the life you want. Penguin.

Madhyastha, S., Latha, K. S., & Kamath, A. (2014). Stress, coping and gender differences in third year medical students. Journal of Health Management, 16(2), 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063414526124

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227

McGonigal, J. (2015). SuperBetter: A revolutionary approach to getting stronger, happier, braver and more resilient. Penguin Press.

Michaels, P. J., Corrigan, P. W., Kanodia, N., Buchholz, B., & Abelson, S. (2015). Mental health priorities: Stigma elimination and community advocacy in college settings. Journal of College Student Development, 56(8), 872–875. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2015.0088

Miyazaki, Y., Bodenhorn, N., Zalaquett, C., & Ng, K.-M. (2008). Factorial structure of Brief COPE for international students attending U.S. colleges. College Student Journal, 42(3), 795-806.

Newman, A., Ucbasaran, D., Zhu, F., & Hirst, G. (2014). Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(S1), S120–S138. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1916

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E, Colditz, J. B., & Everette James, A. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among U.S. young adults. Computer Human Behavior, 69, 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.013

Rabenu, E., Yaniv, E., & Elizur, D. (2017). The relationship between psychological capital, coping with stress, well-being, and performance. Current Psychology, 36(4), 875–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9477-4

Ray, J. (2019). Americans’ stress, worry and anger intensified in 2018. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/249098/americans-stress-worry-anger-intensified-2018.aspx

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Simon & Schuster.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon & Schuster.

Selvaraj, P. R., & Bhat, C. S. (2018). Predicting the mental health of college students with psychological capital. Journal of Mental Health, 27(3), 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1469738

Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510676

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

Tansey, T. N., Smedema, S., Umucu, E., Iwanaga, K., Wu, J.-R., Cardoso, E. D. S., & Strauser, D. (2018). Assessing college life adjustment of students with disabilities: Application of the PERMA framework. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 61(3), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355217702136

Twenge, J. M. (2017). iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood—and what that means for the rest of us. Atria Books.

Umucu, E., Wu, J.-R., Sanchez, J., Brooks, J. M., Chiu, C.-Y., Tu, W.-M., & Chan, F. (2020). Psychometric validation of the PERMA-profiler as a well-being measure for student veterans. Journal of American College Health, 68(3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1546182

Wan, W. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic is pushing America into a mental health crisis. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/05/04/mental-health-coronavirus

Witters, D., & Harter, J. (2020). Worry and stress fuel record drop in U.S. life satisfaction. Gallup.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/310250/worry-stress-fuel-record-drop-life-satisfaction.aspx

Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Luthans, F. (2015). Psychological capital and well-being. Stress Health, 31(3), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2623

Priscilla Rose Prasath, PhD, MBA, LPC (TX), is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Peter C. Mather, PhD, is a professor and department chair at Ohio University. Christine Suniti Bhat, PhD, LPC, LSC (OH), is a professor and the interim director of the George E. Hill Center for Counseling & Research at Ohio University. Justine K. James, PhD, is an assistant professor at University College in Kerala, India. Correspondence may be addressed to Priscilla Rose Prasath, 501 W. Cesar E. Chavez Boulevard, Durango Building, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78207, priscilla.prasath@utsa.edu.

Sep 1, 2018 | Volume 8 - Issue 3

Nayoung Kim, Glenn W. Lambie

To prevent school counselors from experiencing feelings of burnout, identifying relevant factors is important. The purpose of this article is to review studies investigating the constructs of burnout and occupational stress in school counseling samples. Eighteen published research articles fit the inclusion criteria for this review. The researchers identified external and internal variables relating to school counselor burnout, as well as protective and risk factors. The review identified that school counselors’ higher level of burnout correlated with having non-counseling duties, being assigned large caseloads, working in schools that did not meet adequate yearly progress (AYP) status, experiencing a lack of supervision, possessing greater emotion-oriented stress coping scores, providing fewer direct student services, and having greater perceived stress. In contrast, feelings of burnout among school counselors were mitigated when counselors received supervision, possessed higher task-oriented stress coping strategies, scored at higher levels of ego maturity, reported greater occupational support at their schools, had greater grit scores, and worked in schools that met AYP.

Keywords: burnout, occupational stress, school counselors, non-counseling duties, coping strategies

There are multiple definitions of burnout (e.g., Burke & Richardson, 2000; Stalker & Harvey, 2002); however, the primary consistent aspect of burnout is that it is a psychological phenomenon associated with job-related stress (Maslach, 2017). Burnout occurs when professionals are unable to meet their own needs, as well as their clients’ needs, in a high-pressure environment (Maslach, 2017). Freudenberger (1990) identified common symptoms of burnout, including negative changes in individuals’ (a) attitudes and decision making; (b) physiological states; (c) mental, emotional, and behavioral health; and (d) occupational motivation. Burnout has significant consequences, including compromised physical health, increased risk of mental health disorders (e.g., depression, substance abuse), poor job performance, absenteeism, occupational attrition, and low self-esteem (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Burnout can also cause symptoms such as fatigue, exhaustion, and insomnia (Armon, Shirom, Shapira, & Melamed, 2008).

Burnout in School Counseling

Morse, Salyers, Rollins, Monroe-DeVita, and Pfahler (2012) identified that 21% to 67% of mental health professionals reported experiencing high levels of burnout, possibly because of dealing with high client caseloads (Ducharme, Knudsen, & Roman, 2007) or overall job effectiveness (Stalker & Harvey, 2002). In addition, Oddie and Ousley (2007) found that 21% to 48% of mental health workers reported experiencing high levels of emotional exhaustion. School counselors specifically are at risk for experiencing feelings of burnout because of their multiple job demands, including paperwork, parent conferences, school-wide testing, large caseloads, and requests from administrators (McCarthy & Lambert, 2008), and other factors such as role ambiguity and limited occupational support (Young & Lambie, 2007). The school counseling job environment, where “the demands of the work are high, but the resources to meet those demands are low” (Maslach & Goldberg, 1998, pp. 63–64), increases susceptibility to experiencing feelings of burnout (e.g., average student-to-counselor ratio being 491-to-1; National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). Stephan (2005) found that within a national sample of school counselors, 66% of middle school counselors scored at moderate to high levels of emotional exhaustion. Further, Wachter (2006) found that 20% of the school counselors in her investigation (N = 132) experienced feelings of burnout; 16% scored at moderate levels of burnout, and 4% scored at severe levels of burnout. Thus, many school counselors experience feelings of burnout that may influence their ability to provide ethical and effective counseling services to the students they serve.

School counselors may experience chronic fatigue, depersonalization, or feelings of hopelessness and leave their jobs because of the rigidity of school systems and limited support (Young & Lambie, 2007). In fact, counselors experiencing significant feelings of burnout provide reduced quality of service to their clientele because burnout relates to lower productivity, turnover intention, and a lowered level of job commitment (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Because of the importance of preventing the burnout phenomenon, the American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA; 2016) ethical standards note that school counselors are responsible for maintaining their health, both physically and emotionally, and caring for their wellness to ensure their effective practice. The American Counseling Association’s (2014) ethical standards also state that school counselors have an ethical responsibility to monitor their feelings of burnout and remediate when their feelings potentially influence their ability to provide quality services to their stakeholders. To monitor burnout, counselors need to understand the symptoms of burnout and prevent it from happening, while maintaining their psychological well-being.

School counselors face challenges with their significant job demands (McCarthy, Van Horn Kerne, Calfa, Lambert, & Guzmán, 2010), such as large caseloads (Lambie, 2007) and extreme amounts of non-counseling duties (Moyer, 2011). In fact, school counselors report job stress and dissatisfaction when they are required to complete non-counseling duties, hindering their ability to work with their students (McCarthy et al., 2010). Examples of non-counseling duties include clerical tasks, such as scheduling students for classes; fair share, such as coordinating the standardized testing program; and administrative duties, such as substitute teaching (Scarborough, 2005). School counselors with large caseloads and high student-to-counselor ratios are more likely to experience increased feelings of burnout (Bardhoshi, Schweinle, & Duncan, 2014). Although ASCA (2015) recommends a student-to-counselor ratio of 250-to-1, the U.S. average student-to-counselor ratio is almost double the recommended proportion (491-to-1; National Center for Education Statistics, 2016).

Insufficient resources for school counselors and negative job perception increase their likelihood of experiencing feelings of burnout. Lower levels of principal support and lack of clinical supervision raise school counselors’ occupational stress (Bardhoshi et al., 2014; Moyer, 2011). For instance, school counselors with higher levels of role ambiguity are likely to experience burnout (Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). School counselors experience role ambiguity when their responsibilities or the expected level of performance is not clearly identified (Coll & Freeman, 1997). As a result, school counselors report increased levels of stress (Culbreth, Scarborough, Banks-Johnson, & Solomon, 2005), leading to burnout and attrition from the profession (Wilkerson & Bellini, 2006). ASCA (2016) dictated that school counselors’ responsibilities include providing counseling services to students to support their development, which distinguishes them from other school personnel. With the importance of preventing burnout in school counseling, the purpose of this review is twofold: (a) to present identified factors influencing school counselors’ levels of burnout and (b) to offer strategies to assist school counselors in mitigating the feelings of burnout.

Research Examining Burnout in School Counseling

We began by conducting a formal search of electronic databases—PsycINFO, ERIC (EBSCOhost), and Academic Search Premiere—relating to school counselor burnout. The search term burnout was first used to analyze the research trend in the field. Both the search terms burnout and school counselors OR school counseling were used to collect any articles on the topic of school counselor burnout published between 2000 and 2018. An additional search was conducted with the terms occupational stress and school counselors OR school counseling to identify potential studies related to the topic in the same type of literature.

The following inclusion criteria were applied for our review: (a) investigations of school counselor burnout and occupational stress, (b) sample participants were school counselors in the United States, (c) the primary topic of the investigation was burnout and/or occupational stress, (d) articles were written in English, (e) articles were published in refereed journals, and (f) articles were published between 2000 and 2018. In addition, our review excluded literature reviews, editorials, and rejoinders. The abstracts of the articles meeting the criteria were examined and confirmed in order to be included in our review.

Our literature search based on the inclusion criteria produced 51 articles. As not all articles from the search satisfied the criteria, the articles were reviewed manually to evaluate whether they met the criteria, resulting in 35 articles not meeting criteria (e.g., conceptual articles, studies related to teachers) and 16 articles meeting all criteria. An additional literature search yielded two more studies meeting the inclusion criteria, identifying 18 studies in total. None of the identified research articles examined prevention or treatment interventions for burnout in school counselors. The 18 investigations had school counselor burnout or occupational stress as the constructs of interest. The research findings identified the positive relationships between school counselors’ burnout or occupational stress scores and the following factors: (a) non-counseling duties, (b) large caseloads, (c) not meeting adequate yearly progress (AYP) status (i.e., the expected amount of students’ academic growth per year based on the No Child Left Behind mandate [Minnesota House of Representatives, 2003]), (d) lack of supervision, (e) emotion-oriented stress coping scores, (f) grit, and (g) perceived stress.

Fourteen out of 18 articles provided information related to school counselor burnout (see Table 1 for quantitative studies and Table 2 for qualitative studies), and the other four studies investigated school counselors’ occupational stress (see Table 3). Occupational stress refers to the strain a person experiences when the perceived stress in a workplace outweighs their ability to cope (Decker & Borgen, 1993). Quantitative research methods were employed in 15 of the investigations, two used mixed-methods, and one study utilized a qualitative approach. For all 18 articles, the participants were current school counselors, and the number of participants ranged from 3 to 926. Effect sizes were categorized depending on the analysis into three groups (i.e., small, medium, and large) based on the effect size matrix from Sink and Stroh (2006), offering a better understanding of the results. Specifically, the effect size from independent samples t-test (2 groups; Cohen’s d) is interpreted as small for 0.2, medium for 0.5, and large for 0.8. For the effect size of other analyses listed in this review, including paired-samples t-tests (η2), multiple regression (R2), and analysis of variance (ANOVA; η2), 0.01 is considered as small, 0.06 as medium, and 0.14 as large.

Table 1

Summary of Quantitative/Mixed Studies Related to Professional School Counselor (PSC) Burnout

| Study |

Sample |

Variables |

Findings |

| Bain, Rueda, Mata-Villarreal, & Mundy (2011) |

PSCs in rural districts of South Texas

(N = 27)

Convenient Sampling |

Mental health awareness, the amount of time spent on academic advising

|

Feelings of burnout were reported by the majority of the PSCs (89%) in the study and many of them spent the greatest amount of time on administrative duties and the least on counseling. |

| Bardhoshi, Schweinle, & Duncan (2014) |

PSCs

(N = 212)

Random Sampling |

Non-counselor duties, school factors, five subscales of the CBI |

Non-counseling duties and school factors were associated with PSC burnout. Non-counseling duties explained the variance of the three burnout subscales: Exhaustion (11%; medium effect size), NWE (6%; medium effect size), and DPL (8%; medium effect size). Non-counseling duties and other factors (e.g., caseload, principal support) explained the variance of the four burnout subscales: Exhaustion (21%; large effect size), Incompetence (9%; medium effect size), NWE (49%; large effect size), and DPL (17%; large effect size). |

| Butler & Constantine (2005) |

PSCs

(N = 533)

Random Sampling |

Collective self-esteem, burnout, demographics |

Collective self-esteem explained 3% of the variance of PSC burnout (small effect size). In particular, PRCS (2%) and PUCS (1%) accounted for PA (both small effect sizes), and IICS explained 1% of feelings of DP and PA (both small effect sizes). Higher collective self-esteem was associated with lower PSC burnout. PSCs working in urban settings tended to have higher levels of burnout than the counterparts in other environmental settings. PSCs with experience of 20–29 years reported higher levels of burnout than the counterparts with 0–9 years of experience. PSCs with experience of 30 or more years reported higher levels of burnout than those with less experience. |

| Gnilka, Karpinski, & Smith (2015) |

PSCs

(N = 269)

Convenient Sampling |

Five subscales on the CBI |

Effect size differences were found between PSCs and other professionals in the counseling fields (Exhaustion, d = .26, small effect size; DC, d = -.50, medium effect size). Effect size differences were noted between PSCs and sexual offender and sexual abuse therapists (Exhaustion, d = .27, small effect size; DPL, d = -.23, small effect size; DC, d = -.82, large effect size). |

| Lambie (2007) |

PSCs

(N = 218)

Random Sampling

|

Ego maturity, three subscales on the MBI-HSS

|

PSCs with greater levels of ego maturity tended to have a higher level of PA than those with lower ego maturity. Ego maturity predicted PA (3.3%; small effect size). Occupational support and the subscales of burnout were correlated. Reported occupational support predicted EE (16%; large effect size), DP (12%; medium effect size), and PA (7.2%; medium effect size). |

| Limberg, Lambie, & Robinson (2016-2017) |

PSCs

(N = 437)

Random Sampling/

Purposive Sampling |

Altruistic motivation, altruistic behavior, burnout |

PSCs with greater levels of altruism had lower levels of EE and higher feelings of PA. PSC altruism explained 31.36% of the variance in EE (large effect size), and 29.16% of the variance in PA (large effect size). Self-Efficacy accounted for 14.4% of the variance in EE (large effect size) and 9% of the variance in PA (medium effect size). |

| Moyer (2011) |

PSCs

(N = 382)

Convenient Sampling |

Non-guidance activities, supervision, student-to-counselor ratios, five subscales of the CBI |

Non-guidance–related duties and clinical supervision were significant predictors of PSC burnout. Non-guidance duties (7.3%; medium effect size) and supervision (9%; medium effect size) predicted burnout.

|

| Mullen, Blount, Lambie, & Chae (2017) |

PSCs

(N = 750)

Random Sampling |

Perceived stress, burnout, job satisfaction |

Perceived stress predicted burnout positively (large effect size) and job satisfaction negatively (large effect size). Perceived stress and burnout predicted job satisfaction (large effect size). Burnout mediated the relationship between perceived stress and job satisfaction. |

| Mullen & Crowe (2018) |

PSCs

(N = 330)

Convenient Sampling |

Grit, stress, burnout |

Grit was negatively related to burnout (small effect size) and stress (small to medium effect size). |

| Mullen & Gutierrez (2016)

|

PSCs

(N = 926)

Random Sampling

|

Burnout, perceived stress, direct student services

|

Burnout attributed to direct counseling activities (12%; medium effect size), direct curriculum activities (5%; small to medium effect size), and percentage of time at work providing direct services to students (6%; medium effect size). |

| Wachter, Clemens, & Lewis (2008) |

PSCs

(N = 249)

Random Sampling |

Demographics, stakeholder involvement, lifestyle themes, burnout |

Burnout and lifestyle themes were associated. Perfectionism subscale was negatively related to burnout, and the Self-Esteem subscale was positively related to PSC burnout. About 15.1% of the variance in burnout was accounted for by the lifestyle themes of Self-Esteem and Perfectionism (large effect size). |

| Wilkerson & Bellini (2006)

|

PSCs in northeastern U.S.

(N = 78)

Systematic Random Sampling

|

Demographics, intrapersonal, and organizational factors; three subscales on the MBI-ES |

Demographic (age, counseling experience, supervision, and student/counselor ratio), intrapersonal, and organizational factors significantly accounted for the amount of the variance in each subscale of burnout, including EE (45%; large effect size), DP (30%; large effect size), and PA (42%; large effect size). |

| Wilkerson (2009)

|

PSCs

(N = 198)

Random Sampling |

Demographic and organizational stressors and individual coping strategies; three subscales on the MBI-ES |

Demographic factors (years of experience and student/counselor ratio), organizational stress, and coping styles explained the variance of each subscale of burnout including EE (49%; large effect size), DP (27%; large effect size), and PA (36%; large effect size).

|

Table 2

Summary of Qualitative/Mixed Studies Related to Professional School Counselor Burnout

| Study |

Sample |

Topic |

Identified Themes |

| Bain, Rueda, Mata-Villarreal, & Mundy (2011) |

PSCs in rural districts of South Texas (N = 27)

Convenient Sampling |

Helpful ways to better provide mental health services at school |

Having access to additional staff and additional education and awareness in terms of helpful ways to provide mental health services at their school. |

| Bardhoshi, Schweinle, & Duncan (2014) |

PSCs

(N = 252)

Random Sampling |

a) Their experience of burnout

b) The meaning of performing non-counseling duties |

a) Lack of time, budgetary constraints, lack of resources, lack of organizational support, etc.

b) Adverse personal/professional effects, a reality of the job, reframing the duties within the context of the job. |

| Sheffield & Baker (2005) |

Female PSCs

(N = 3)

Purposive Sampling |

Burnout experience |

Important beliefs, burnout feelings, burnout attitude, (lack of) collegial support. |

Table 3

Summary of Quantitative Studies Related to Professional School Counselor Occupational Stress

| Study |

Sample |

Variables |

Findings |

| Bryant & Constantine (2006) |

Female PSCs

(N = 133)

Random Sampling |

Role balance, job satisfaction, satisfaction with life, demographics |

Multiple role balance ability and job satisfaction positively predicted overall life satisfaction. Role balance and job satisfaction explained the variance of life satisfaction (41%; large effect size). |

| Culbreth, Scarborough, Banks-Johnson, & Solomon (2005) |

PSCs

(N = 512)Stratified Random Sampling |

Role conflict, role ambiguity, role incongruence, demographics |

Perceived match between the job expectations and actual experiences predicted role-related job stress, including role conflict (7.6%; medium effect size); role incongruence (19.7%; large effect size); and role ambiguity (8.3%; medium effect size). |

| McCarthy, Van Horn Kerne, Calfa, Lambert, & Guzmán (2010) |

PSCs in Texas

(N = 227) Convenient Sampling |

Demographics, job stress, resources and demands |