Aug 26, 2025 | Volume 15 - Issue 3

Julie C. Hill, Toni Saia, Marcus Weathers, Jr.

Ableism is often neglected in conversations about oppression and intersectionality within counselor education programs. It is vital to expand our understanding of disability as a social construct shaped by power and oppression, not a medical issue defined by diagnosis. This article is a call to action to combat ableism in counselor education. Actionable recommendations include: (a) encouraging professionals to define and discuss ableism; (b) including disability representation in course materials; (c) engaging in conversations about disability with students; (d) collaborating with, responding to, and supporting disabled people and communities; and (e) reflecting on personal biases to help dismantle ableism within counselor education. Implications for counselor educators highlight the ongoing need for more ableism content within the profession.

Keywords: ableism, disability, counselor education, representation, biases

Disability is rarely examined through intersectionality and critical consciousness, despite its deep connections to race, class, gender, and other social identities (Berne et al., 2018). As the United States becomes increasingly diverse, the need for counselors who can competently address the complex, intersecting needs of disabled people has never been more urgent (Dollarhide et al., 2020). Disabled people are the largest and fastest-growing minority group, with approximately 60 million people reporting some form of disability (Elflein, 2024). Despite this increasing prevalence, ableism, known as the systemic discrimination and exclusion of disabled people, remains persistent in our society. Slesaransky-Poe and García (2014) further discuss ableism as the belief that disability makes someone less deserving of many things, including respect, education, and access within the community.

Ableism and ableist beliefs have profoundly shaped how society perceives and interprets the disability experience. Historically, the medical model has framed disability as an inherent defect within the individual, requiring treatment, rehabilitation, or correction to restore “normal” functioning (Leonardi et al., 2006). This deficit-based perspective, reinforced by legal definitions, has shaped societal attitudes and policies, often prioritizing intervention over community integration. In contrast, the social model of disability shifts the focus from the individual to the broader societal structures, emphasizing how inaccessible environments, exclusionary policies, and ableist attitudes create disabling conditions (Bunbury, 2019; Friedman & Owen, 2017; Shakespeare, 2006). This model asserts that disability is not simply a medical issue, but a social justice concern requiring systemic change to remove barriers and promote full participation. Within counselor education programs, the biopsychosocial model is often taught as a more integrative framework that acknowledges disability as a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Although medical interventions may be necessary for some individuals, this model emphasizes addressing environmental and attitudinal barriers contributing to marginalization. By adopting this holistic approach, counselors can better advocate for equity, inclusion, and meaningful accessibility for all.

This article provides an asset-based framework that views disability as a valuable aspect of diversity rather than a deficit or limitation. This approach recognizes the strengths, perspectives, and contributions that disabled people bring to communities and educational spaces (Olkin, 2002; Perrin, 2019). By embracing disability as an aspect of diversity, this framework challenges societal norms rooted in ableism, which often prioritize conformity and cure over anti-ableism (Bogart & Dunn, 2019). Through this lens of power and oppression, disability is celebrated as a source of innovation, creativity, and cultural richness, encouraging practices that empower disabled individuals to thrive both in the classroom and in the community. To reinforce this shift in thinking to disability as an asset, we use identity-first language, recognizing that many disabled people prefer it as a positive affirmation of their lived experiences and their connection to the disability community (Sharif et al., 2022; Taboas et al., 2023).

Intersectionality and Disability

Scholars recognize intersectionality as an analytical tool to investigate how multiple systems of oppression interact with an individual’s social identities, creating complex social inequities and unique experiences of oppression and privilege for individuals with multiple marginalized identities (Collins & Bilge, 2020; Crenshaw, 1989; Grzanka, 2020; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017; Shin et al., 2017). The topic of disability is often absent in conversations regarding power, oppression, and privilege (Ben-Moshe & Magaña, 2014; Erevelles & Minear, 2010; Frederick & Shifrer, 2018; Mueller et al., 2019; Wolbring & Nasir, 2024) despite the potential for disability to intersect with other marginalized identities (e.g., racial/ethnic identity, gender identity, socioeconomic status, religious and spiritual beliefs, citizenship/immigration status) that lead to intersectionality-based challenges that conflict with the marginalization of being disabled (Wolbring & Nasir, 2024). For example, Lewis and Brown (2018) condemned the lack of accountability in reporting on disability, race, and police violence, which often irresponsibly neglects the coexistence of disability in conversations of experienced violence. Using the framework of intersectionality responsibly in disability discourse within counselor education holds significant potential for the professional development of counselors to work toward unmasking and dismantling ableism.

Challenges and Gaps in Anti-Ableism in Counselor Education and Training

How counselor educators teach about disability is crucial to dismantling ableism, yet history reveals a troubling lack of cultural humility in educational approaches. Cultural humility is a process-oriented approach that continuously emphasizes the counselor’s openness to learn about a client’s culture and invites counselors to consistently incorporate self-reflective activities to enhance their self-awareness (Mosher et al., 2017). Although cultural humility may be well intended, it may also have a harmful impact and fall flat if inherent biases go unrecognized. For example, counselor educators heavily relied on simulation exercises to address disability in the classroom (e.g., having students blindfold themselves for an activity to simulate blindness or having them sit in a wheelchair for a short period). Simulation exercises reinforce a deeply medicalized and reductive view of disability, one rooted in fear, pity, and misconception, ultimately erasing disability as both a culture and an identity (Öksüz & Brubaker, 2020; Shakespeare & Kleine, 2013). Beatrice Wright (1980, as cited in Herbert, 2000), cautioned that simulation experiences evoke fear, aversion, and guilt. These exercises rarely foster meaningful or constructive perspectives on disability. Instead of deepening understanding, these exercises risk reinforcing harmful stereotypes, further marginalizing disabled individuals rather than empowering them. Instead of disability simulations, honor the voices and experiences of disabled individuals through their narratives, such as Being Heumann by Judy Heumann, as well as documentaries and movies like Crip Camp, Patrice, or CODA. Contact with disabled individuals has been shown to reduce stigma against disabled people (Feldner et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2011). Additionally, incorporate analyzing ableism through case studies, readings, or media, followed by a structured discussion.

Topics of multiculturalism and diversity have increased over the years; the same cannot be said for disability (Rivas, 2020). Davis (2011) poignantly asked, “Is this simply neglect, or is there something inherent in the way diversity is considered that makes it impossible to recognize disability as a valid human identity?” (p. 4). More than a decade later, this question remains painfully relevant. Atkins et al. (2023) explored this issue through a study using the Counseling Clients with Disabilities Scale to evaluate professionals’ attitudes, competencies, and preparedness when working with disabled clients. The findings underscore the critical need for education and exposure to disability-related topics in counselor training, demonstrating that such efforts improve competency, reduce biases, and foster more inclusive, equitable, and empowering support. However, disability continues to receive significantly less attention than other cultural and identity groups in professional training and discourse (Deroche et al., 2020).

Furthermore, ableist microaggressions continue to be a concern for disabled individuals. Cook and colleagues (2024) conducted a study looking at microaggressions experienced by disabled individuals and found four categories of microaggressions: minimization, denial of personhood, otherization, and helplessness. They also found that experiencing ableist microaggressions affected participants’ mental health and wellness. Additionally, they found that those with visible disabilities were more likely to experience ableist microaggressions than those with invisible disabilities. Given these findings, counselor educators need to be aware that ableist microaggressions exist, what those microaggressions may sound like, and how they impact disabled clients.

Concerns exist about the extent to which counselor education programs cover disability content; there is also a need to examine instructors’ preparedness for covering such content. In a survey of counselor educators in programs accredited by the Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP), 36% of the faculty surveyed believed their program was ineffective at addressing disability topics and that programs did not address disability and ableism to the extent necessary to produce competent professionals. Only 10.6% felt their program to be “very effective” in this content area, with the belief that their students were only somewhat prepared to work with disabled people (Feather & Carlson, 2019). Notably, these oversights in education translate into inadequacy in practice. A sample of mental health professionals who all reported working with disabled clients indicated the least amount of perceived disability competence in skills, the second least competence in knowledge, and the most competence in awareness (Strike et al., 2004). Faculty self-assessment of their ability to teach disability-related content was strongly linked to their prior work or personal experience with disability. This highlights the importance of integrating exposure to and training on disability-related concepts throughout core areas (Pierce, 2024). Although separated by a decade, these studies can be tied to a unifying, persistent issue: the lack of disability competence in counseling and counselor education spaces.

The 2024 CACREP standards call for an infusion of disability competencies into counseling curricula (CACREP, 2023), meaning that counselor educators and counselors-in-training must reimagine the available literature to provide adequate professional development and growth. Pierce (2024) advised that disability competence areas be focused on the following topics: accessibility, able privilege, disability culture, and disability justice. We must seek to dismantle ableism by infusing disability into curricula in an authentic manner that highlights the societal values and attitudes in which multiple forms of oppression work in tandem to create unique, intersectional experiences for disabled people.

Training Recommendations for Counselor Education Programs

The authors aim to ensure counselor educators have tangible strategies to dismantle ableism and teach their students to do the same. Counselor educators and counselors-in-training must look inward and rid themselves of negative attitudes and biases to eradicate ableism. Part of this process includes the critical skill of self-reflection and examining and understanding biased and ableist beliefs held by individuals and perpetuated by society. Until that happens, counselors will continue to do a disservice to disabled people (Friedman, 2023). For students who have never interacted with disabled people or thought about ableism, these conversations and strategies have the very real possibility of making them uncomfortable. Discomfort is okay. Disabled people often feel awkward or out of place every day because of ableism. It is not our job as counselor educators to make students comfortable; it is our job to make them competent, informed, and ethical professionals.

The following are five tangible strategies to thoughtfully and intentionally dismantle ableism. These strategies are purposefully broad and aim to expose counseling professionals and those in training to an intersectional perspective of disability that acknowledges disability as a valid aspect of diversity, identity, and culture. Rather than siloing these discussions to disability-related training, these strategies belong in all settings within counseling. Counseling professionals must include ableism in the conversations happening in places where they learn and work to shift the way they think, view, respond to, and construct disability. To begin, counselor education programs should consider hosting a workshop or seminar focused on ableism by disabled people to ensure that all students and faculty are on the same page and are using the same terminology. Once this has been established, ableism and disability content and knowledge should be incorporated into lectures, assignments, discussions, and exams across the counselor education curriculum. Further information on this integration is described in the first strategy below.

Define Ableism

One of the factors that further perpetuates ableism is the lack of clarity on what ableism is and how it intersects with other forms of oppression. Counselor educators must share definitions of ableism that center on the perspective of the disabled community. Talia Lewis (2022) provided a working definition of ableism that disabled Black/negatively racialized communities developed:

A system of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, excellence, and fitness. These constructed ideas are deeply rooted in eugenics, anti-Blackness, misogyny, colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism. This systemic oppression leads to people and society determining people’s value based on their culture, age, language, appearance, religion, birth or living place, “health/wellness,” and/or their ability to satisfactorily re/produce, “excel,” and “behave.” You do not have to be disabled to experience ableism. (para. 4–6)

This definition expands on the definition provided earlier of ableism as the systemic discrimination and exclusion of disabled people. It rejects the notion that ableism can be dismantled or separated from other forms of oppression (e.g., racism, sexism, and other systems of oppression). Within counseling curricula, we often use the term intersectionality, but it is impossible to address intersectionality with our students if we do not thoughtfully include ableism. We should challenge the idea that disability is a monolithic experience as we seek to build a more complex, interconnected, and whole understanding of disability (Mingus, 2011).

It is also essential to acknowledge internalized ableism, which is ableism directed inward when a disabled person consciously or unconsciously believes in the harmful messages they hear about disability. They project negative feelings onto themselves. They start to believe and internalize the message that society labels disability as inferior. They begin to accept the stereotypes. Internalized ableism occurs when individuals are so heavily influenced by stereotypes, misconceptions, and discrimination against disabled people that they start to think that their disabilities make them inferior (Presutti, 2021). For example, a disabled student may not participate in class because they believe their contributions are inferior compared to their nondisabled peers, or a disabled client may experience feeling undeserving, undesirable, and burdensome.

To effectively implement this awareness, ask students to define ableism in their own words. Coming up with their definition of ableism encourages critical thinking and allows the counselor educator to gauge students’ existing understanding. Then, introduce the Lewis (2022) definitions above to provide a more comprehensive framework. To reinforce these concepts, incorporate case studies illustrating real-world examples of ableism. Analyzing these cases in class discussions or group activities will help students identify ableist structures, challenge assumptions, and explore solutions for creating more welcoming environments. Counselors can examine ableism in societal contexts by viewing movies or television shows that feature disabled characters and analyzing how ableism is portrayed in media. Because of societal barriers to access and the taboos surrounding discussions of disability, the entertainment and news media serve as a key source for many people to form opinions about disability and disabled individuals. Unfortunately, these portrayals are limited and often spread misinformation and harmful stereotypes (Pierce, 2024). One way to help combat this could be by watching a movie or show together as a class and then having a discussion or having students watch on their own and write a short reflection followed by a class discussion. Some suggested movies include Crip Camp, Murderball, The Temple Grandin Story, Patrice, and Out of My Mind. Some suggested television shows include Speechless, Love on the Spectrum, Special, Raising Dion, Atypical, and The Healing Powers of Dude.

Include Disability Representation in Course Content

The phrase “representation matters” also applies to disability. Counselor educators should include disability and discussions of the impact of systemic ableism throughout course content, not only in a single lecture or reading on the course syllabus. Decisions about course content send powerful messages about what the counselor educator, the program, and the broader counseling profession prioritize and value. Including or excluding specific topics reflects the educator’s perspective and shapes future counselors’ professional identity and competencies. When disability is overlooked or inadequately addressed, it signals to students that it is not a central concern in counseling practice, which reinforces systemic gaps in knowledge, awareness, and advocacy. To counter this erasure and to ensure meaningful representation, intentionally incorporate guest speakers, videos, readings, memoirs, and research that center on the perspectives of disabled people. This gives students an authentic and multifaceted understanding of disability beyond theoretical discussions. Consider integrating a book or memoir that centers a disabled perspective alongside the course textbook to bridge the gap between academic content and real-life experiences. This approach not only deepens students’ engagement but also challenges ableist assumptions by highlighting the lived realities, resilience, and contributions of disabled people.

Engage in Conversation About Disability With Students

Disability is not a bad word. Counselor educators must instill this simple yet profound truth in students. Euphemisms like differently abled, handicapable, or special needs perpetuate ableism when used in place of the term disability, implying that disability is something shameful or in need of softening; they do more harm than good. Counselor educators must allow students the opportunity to engage in discussion about disability to challenge the idea that disability is taboo and move into a space where students can appreciate that disability is a natural part of life. Counselor educators must foster a safe and supportive learning community that allows students to engage in dialogue and discussion about their beliefs and experiences that have shaped their beliefs, and examine how those beliefs led to the development or perpetuation of ableist ideas and microaggressions. This allows students to learn, grow, and reshape their beliefs and understanding together. This quote sums it up best: “Disabled people are reclaiming our identities, our community, and our pride. We will no longer accept euphemisms that fracture our sense of unity as a culture: #SaytheWord” (Andrews et al., 2019, p. 6). To empower students to #SayTheWord in both classroom discussions and professional practice, dedicate time, especially during the first weeks of class, to explicitly affirm that disability is not a bad word. Normalize its use by providing historical context, sharing first-person perspectives, and emphasizing the importance of language in shaping attitudes. By reinforcing disability as an act of recognition rather than avoidance, you help students develop confidence in using identity-affirming language and challenging the stigma often associated with the term.

Collaborate, Respond, and Support Disabled People

Counselor educators, counselors, and counselors-in-training should seek opportunities to listen to, respond to, support, and collaborate with disabled counselors and other disabled scholars. Thoughtful collaborations allow for authentic exposure and conversation that support the unlearning of ableist beliefs. This approach is consistent with the disability rights mantra “nothing about us without us” (Charlton, 1998, p. 3), which implies that no change can occur without the direct input of disabled individuals. One opportunity for collaboration includes professional conferences and attending presentations by disabled academics and professionals. Other opportunities for collaboration include working with and supporting local disabled business owners and seeking out organizations such as independent living centers to bring in disabled speakers to share their lived experience and interactions with ableism and microaggressions. Be sure to compensate these individuals for their time so that the work of collaboration is mutually beneficial to all parties.

Disabled people are the experts of their experiences, not professionals. This statement is not synonymous with implementing a client-centered or person-centered approach. Instead, the focus of this statement is to make sure counselors have the tools to trust, support, uplift, and dismantle ableism with disabled clients. If it starts in the classroom, counselors-in-training will be better prepared in practice and life outside of work. As professionals know, trust in the counselor-client relationship is essential for the disabled community. It often develops when individuals feel heard, trusted, and validated, rather than being second-guessed or minimized, especially as they share about the external and internal ableism they face daily. Lund (2022) recommended consulting with both disabled psychologists and trainees to bring a “critical insider-professional perspective” (p. 582) to the profession. By consulting and bringing these disabled professionals in for training or speaking about personal experiences, we can ensure that disabled voices are heard and recognized.

Another way to amplify disabled voices is through the teaching of disability justice. The Disability Justice framework affirms that every person’s body holds inherent value, power, and uniqueness. It recognizes that identity is shaped by the interconnected influences of ability, race, gender, sexuality, class, nationality, religion, and other factors. It stresses the importance of viewing these influences together rather than separately. From this perspective, the fight for a just society must be grounded in these intertwined identities while also acknowledging Berne et al.’s (2018) critical insight that the current global system is “incompatible with life” (para. 13). Central principles of disability justice, such as centering leadership by those most impacted, fostering interdependence, ensuring collective access, building cross-disability solidarity, and pursuing collective liberation, prioritize intersectionality and cross-movement collaboration to guarantee that no one is excluded or left behind. (Pierce, 2024).

Helping students understand and internalize these ideas and principles should lead to the development of more aware and anti-ableist counselors in several ways. Rather than viewing client struggles as isolated or purely personal issues, understand that many forms of suffering, especially those faced by disabled people and people with intersecting marginalized identities, are rooted in larger social, economic, and political systems that devalue certain lives. For example, ableism, racism, and capitalism often create conditions that threaten people’s survival, whether through limited access to health care, environmental injustice, or social exclusion.

Counselors-in-training should be attuned to how multiple aspects of identity (such as disability, race, gender, and class) interact to shape each client’s lived experience. This approach moves counseling away from a one-size-fits-all perspective and helps address the unique, layered barriers that clients face. Traditional counseling and counselor preparation often focus on assisting clients to adapt to oppressive systems. The Disability Justice perspective instead calls for counselors-in-training to see their role as also advocating for systemic change, working toward environments and policies that are actually supportive of all people’s well-being. Rather than idealizing independence, disability justice values interdependence and community care. Counselors and counselors-in-training can foster this by helping clients build supportive networks and by modeling collaborative, relational approaches in practice.

Regularly Reflect on Personal Biases and Be Open to Feedback

Counselor educators often ask counselors-in-training to reflect on their own biases in terms of race, gender, and sexual orientation. However, ableism and disability are often forgotten or left out of those conversations. It is essential for these conversations about bias to include disability so that everyone has opportunities to explore and discuss their own potential biases. Embedding disability representation in the classroom allows everyone to see how they respond to disabled people, especially when that representation is in the form of case studies and client role-play. Then, everyone, including supervisors, can constructively receive feedback from a trusted figure and can change or improve their reactions and responses if necessary. Furthermore, counselor educators and counselors-in-training can keep reflective journals, seek supervision or peer discussions, and review case notes with an anti-ableist lens, which can help identify areas for growth. Additionally, counselor educators should actively solicit feedback from the disability community, welcoming their perspectives without defensiveness. When possible, attend training led by disabled professionals and the disabled community to reinforce a commitment to continuous learning and accountability.

Implications for Counselor Educators

Counselor educators are responsible for training counselors to work with all types of clients, including disabled clients. Counselors will encounter disabled clients, no matter the setting that they are working in. Disability can impact anyone and does not discriminate across gender, race, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, or geographic location. Disability is the one minority group that anyone can become a part of at any time in their life. Most people will age into disability as they get older (Shapiro, 1994). Counselor educators need to be sure that counselors are confronting and dismantling their own ableism and ableist beliefs and that they understand that they may need to assist clients in processing their own experiences with ableism in society and interactions with others. One self-assessment for self-reflection and insight is the Systematic Ableism Scale (SAS; Friedman, 2023). The SAS has four underlying themes: individualism, recognition of continuing discrimination, empathy for disabled people, and excessive demands. The SAS is a tool that can be used to help understand how contradicting disability ideologies manifest in modern society to determine how best to counteract them. By using this assessment as a self-evaluation tool, both students and counselor educators can identify where their beliefs may be problematic or ableist and then set goals to address and improve in those areas.

We recommend that counselors intentionally occupy spaces where discussions on disability advocacy are occurring. Universities are often regarded as a primary source of knowledge production, but a common misconception is that the people themselves produce the knowledge. The reality is that not all disability content is produced by disabled individuals or organizations. Thus, we encourage counselor educators to expand access to knowledge about disability by seeking spaces outside the institution that share insider perspectives on the disability experience and organizations dedicated to empowering disabled communities. This may involve engaging with informal educational organizations such as Sins Invalid, AXIS Dance Company, and Krip Hop Nation or getting involved with formal professional organizations such as APA Division 22, the American Rehabilitation Counseling Association, or the National Rehabilitation Counseling Association. Some strategies that can be used to advocate for and in support of disabled clients include client-centered advocacy, understanding disability as a cultural identity, and building knowledge of the disability rights movement, ableism, and intersectionality, as well as integrating disability-inclusive language, avoiding ableist assumptions, and incorporating clients’ lived experiences into treatment (Chapin et al., 2018; Smart, 2015; Smith et al., 2011).

The foundation for a competent and qualified counselor begins with their training. This training can be formal education or ongoing professional development. For those responsible for educating counselors-in-training, laying the foundation for anti-ableism practices begins in the classroom. A universal design for learning (UDL) framework, developed by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST, 2018), aims to create accessible material and inclusive environments that are usable for all people by intentionally incorporating multiple representations of content to enhance student expression of learning and increase a variety of opportunities for engagement with the learning environment (Black et al., 2015; Dolmage, 2017; Fornauf & Erickson, 2020). UDL principles support anti-ableist practice by encouraging an ongoing partnership between students and instructors that facilitates consistent and practical feedback to promote student belongingness (Hennessey & Koch, 2007; Oswald et al., 2018). Promoting belonging and acceptance in counselor education programs requires intentional strategies that foster inclusivity, respect for diversity, and a strong sense of community. Effective techniques include: 1) Use inclusive curriculum design. Integrate diverse perspectives throughout the curriculum, with special attention paid to marginalized voices, such as disabled voices. 2) Use culturally responsive pedagogy. This includes employing a range of instructional methods to cater to diverse learning styles. Use trauma-informed practices by creating a learning environment that is sensitive to trauma, both past and present. 3) Implement community-building activities such as structuring programs around cohorts and encouraging the formation of affinity groups and peer support groups. 4) Encourage active dialogue and reflection around tough conversations such as diversity, ableism, inequality, and marginalization. This can be done both in person and online via discussion boards. Faculty can also encourage students to explore their thoughts, reflections, and experiences around issues of identity, belonging, and ableism in a reflective journal. 5) Collect feedback to guide continuous improvement. Faculty can assess students’ experiences with inclusion and ableism through climate surveys.

Additionally, the adoption of multiple methods for delivering information in alternate formats and continuous assessment of student progress reduces barriers to student engagement and expression in the learning environment, which in turn systematically challenges normative ableist practice that values a one-size-fits-all perspective that often neglects disabled thought and existence in pedagogical practices (Oswald et al., 2018). UDL strategies to disrupt ableist thought and practices may include using closed captioning on visual multimedia content (e.g., videos, PowerPoint presentations), incorporating movement breaks, creating interactive activities (e.g., role-play activities, gamification, debates on critical topics), and receiving feedback on instruction.

Hill and Delgado (2023) discussed the importance of including disability coursework and content across multiple domains to effectively address ableism in counselor education programs. Building upon their work, we suggest that the following key types of coursework and content be included. At a minimum, disability content should be integrated into the core CACREP curriculum areas: professional counseling orientation and ethical practice, social and cultural foundations, lifespan development, career development, counseling practice, group counseling, assessment and diagnosis, and research and program evaluation (CACREP, 2023).

Foundational Disability Studies

Students should explore and understand how ableism developed and its systemic nature, especially in the current political climate (Campbell, 2009; Dolmage, 2017). Additionally, students can learn about models of disability: medical, sociopolitical, functional, religious, moral, and biopsychosocial (Engel, 1977; Shakespeare, 2006; Smart, 2015). Students must also understand the concept of intersectionality, which examines how disability interacts with race, gender, sexuality, and socioeconomic status (Erevelles & Minear, 2010; Garland-Thompson, 2005).

Ethics and Multicultural Competence

Students should understand the intersection of disability and ethics by being able to apply the ACA Code of Ethics to disability issues (Chapin et al., 2018; Feather & Carlson, 2019). In either an ethics class or a multicultural class, students must learn about crucial disability-related legislation, such as the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. In the multicultural class, students need to understand disability cultural competence and receive training on disability as a cultural identity and recognizing ableism as a form of oppression (Feldner et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2011). Additionally, in the multicultural class, students should be taught about biases and microaggressions, as well as how to identify and address ableist language and behavior.

Counseling Skills and Practice

In a counseling skills class, students must learn accessible counseling techniques, such as modifying approaches for different abilities (e.g., sensory, cognitive, mobility). Students should also be presented with case studies involving disabled clients, with an emphasis on strengths-based and person-centered approaches. Additionally, students ought to receive supervision and advocacy training on how to support and advocate for clients with disabilities in clinical settings. Counselor educators can use the strategies listed here in the classroom and in practice.

Directions for Future Research

Two of the three authors of this article are disabled and bring lived experience to their teaching, writing, research, and engagement with the nondisabled world. This real-world experience informs the strategies presented and has been applied in both classroom and professional settings. However, these approaches have not yet been empirically tested through formal research. Future research could focus on empirically validating these strategies through qualitative or quantitative studies, particularly in evaluating confidence when working with disabled clients before and after implementing these strategies. Strategies include incorporating disability knowledge into the counselor education curriculum coursework (Hill & Delgado, 2023), using critical pedagogy and disability justice frameworks when teaching (Dolmage, 2017; Erevelles & Minear, 2010), providing experiential learning and opportunities for contact with disabled individuals (Smith et al., 2011), giving disability-related education and training for faculty and supervisors (Feldner et al., 2022), and encouraging the development of allyship and advocacy skills (Feldner et al., 2022; Goodman et al., 2004). Additional studies are also needed to examine ableism and confidence in teaching anti-ableist concepts and disability-related competencies by counselor educators. Finally, scales or measures to assess ableism, specifically in counselor education, could be created and validated.

Conclusion

These strategies do not aim to be an all-encompassing, definitive, or exhaustive checklist, as there are many ways to dismantle ableism. These strategies are a starting point, a reminder, a point of reflection, or an opportunity to affirm current strategies. Significantly, these strategies extend beyond counseling and are relevant across various educational and professional settings, from K–12 classrooms to higher education, social work, health care, and beyond. Wherever you land, we invite you to continue learning, growing, and committing to change with us. Alice Wong (2020) proclaimed, “There is so much that able-bodied people could learn from the wisdom that often comes with disability. However, space needs to be made. Hands need to reach out. People need to be lifted up” (p. 17). Together, we can extend our hands, challenge systemic barriers, and work to dismantle ableism in counseling settings and across all aspects of society.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

References

Andrews, E. E., Forber-Pratt, A. J., Mona, L. R., Lund, E. M., Pilarski, C. R., & Balter, R. (2019). #SaytheWord: A disability culture commentary on the erasure of “disability.” Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000258

Atkins, K. M., Bell, T., Roy-White, T., & Page, M. (2023). Recognizing ableism and practicing disability humility: Conceptualizing disability across the lifespan. Adultspan Journal, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.33470/2161-0029.1151

Ben-Moshe, L., & Magaña, S. (2014). An introduction to race, gender, and disability: Intersectionality, disability studies, and families of color. Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 2(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.5406/womgenfamcol.2.2.0105

Berne, P., Morales, A. L., Langstaff, D., & Invalid, S. (2018). Ten principles of disability justice. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46(1–2), 227–230. https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2018.0003

Black, R. D., Weinberg, L. A., & Brodwin, M. G. (2015). Universal design for learning and instruction: Perspectives of students with disabilities in higher education. Exceptionality Education International, 25(2), 1–26.

Bogart, K. R., & Dunn, D. S. (2019). Ableism special issue introduction. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 650–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12354

Bunbury, S. (2019). Unconscious bias and the medical model: How the social model may hold the key to transformative thinking about disability discrimination. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 19(1), 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1358229118820742

Campbell, F. K. (2009). Contours of ableism: The production of disability and abledness. Palgrave Macmillan.

CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 3.0. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Chapin, M., McCarthy, H., Shaw, L., Bradham-Cousar, M., Chapman, R., Nosek, M., Peterson, S., Yilmaz, Z., & Ysasi, N. (2018). Disability-related counseling competencies. American Rehabilitation Counseling Association. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/arca-disability-related-counseling-competencies-v51519.pdf?sfvrsn=984f4bd0_1

Charlton, J. I. (1998). Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. California University Press.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Cook, J. M., Deroche, M. D., & Ong, L. Z. (2024). A qualitative analysis of ableist microaggressions. The Professional Counselor, 14(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/10.15241/jmc.14.1.64

Council for the Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2023). 2024 CACREP standards. https://www.cacrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2024-Standards-Combined-Version-4.11.2024.pdf

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf

Davis, L. J. (2011, September 25). Why is disability missing from the discourse on diversity? The Chronicle of Higher Education, 25, 38–40. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-is-disability-missing-from-the-discourse-on-diversity

Deroche, M. D., Herlihy, B., & Lyons, M. L. (2020). Counselor trainee self-perceived disability competence: Implications for training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 59(3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12183

Dollarhide, C. T., Rogols, J. T., Garcia, G. L., Ismail, B. I., Langenfeld, M., Walker, T. L., Wolfe, T., George, K., McCord, L., & Aras, Y. (2020). Professional development in social justice: Analysis of American Counseling Association conference programming. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12298

Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9708722

Elflein, J. (2024, November 19). Topic: Disability in the U.S. – Statistics & facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/4380/disability-in-the-us

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Erevelles, N., & Minear, A. (2010). Unspeakable offenses: Untangling race and disability in discourses of intersectionality. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 4(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2010.11

Feather, K. A., & Carlson, R. G. (2019). An initial investigation of individual instructors’ self-perceived competence and incorporation of disability content into CACREP-accredited programs: Rethinking training in counselor education. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 47(1), 19–36.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12118

Feldner, H. A., Evans, H. D., Chamblin, K., Ellis, L. M., Harniss, M. K., Lee, D., & Woiak, J. (2022). Infusing disability equity within rehabilitation education and practice: A qualitative study of lived experiences of ableism, allyship, and healthcare partnership. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3, 947592.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.9397845

Fornauf, B. S., & Erickson, J. D. (2020). Toward an inclusive pedagogy through universal design for learning in higher education: A review of the literature. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2), 183–199. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1273677.pdf

Frederick, A., & Shifrer, D. (2018). Race and disability: From analogy to intersectionality. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 5(2), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649218783480

Friedman, C. (2023). Explicit and implicit: Ableism of disability professionals. Disability and Health Journal, 16(4), 101482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2023.101482

Friedman, C., & Owen, A. L. (2017). Defining disability: Understandings of and attitudes towards ableism and disability. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(1).

Garland-Thomson, R. (2005). Feminist disability studies. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30(2), 1557–1587. https://doi.org/10.1086/423352

Goodman, L. A., Liang, B., Helms, J. E., Latta, R. E., Sparks, E., & Weintraub, S. R. (2004). Training counseling psychologists as social justice agents: Feminist and multicultural principles in action. The Counseling Psychologist, 32(6), 793–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000004268802

Grzanka, P. R. (2020). From buzzword to critical psychology: An invitation to take intersectionality seriously. Women & Therapy, 43(3–4), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2020.1729473

Hennessey, M. L., & Koch, L. (2007). Universal design for instruction in rehabilitation counselor education. Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education, 21(3), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1891/088970107805059689

Herbert, J. T. (2000). Simulation as a learning method to facilitate disability awareness. Journal of Experiential Education, 23(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590002300102

Hill, J. C., & Delgado, H. (2023). Incorporating disability knowledge and content into the counselor education curriculum. ACES Teaching Practice Briefs, 21(2), 18–31. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388758290_Incorporating_Disability_Knowledge_and_Content_into_the_Counselor_Education_Curriculum

Leonardi, M., Bickenbach, J., Ustun, T. B., Kostanjsek, N., & Chatterji, S. (2006). The definition of disability: What is in a name? The Lancet, 368(9543), 1219–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69498-1

Lewis, T. A. (2022, January 1). Working definition of ableism—January 2022 update. https://www.talilalewis.com/blog/working-definition-of-ableism-january-2022-update

Lewis, T. A., & Brown, L. X. Z. (2018). Accountable reporting on disability, race & police violence: A community response to the “Ruderman Foundation paper on the media coverage of use of force and disability.” https://www.talilalewis.com/blog/archives/06-2018

Lund, E. M. (2022). Valuing the insider-professional perspective of disability: A call for rehabilitation psychologists to support disabled psychologists and trainees across the profession. Rehabilitation Psychology, 67(4), 582–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000452

Mingus, M. (2010, February 12). Changing the framework: Disability justice. Leaving Evidence. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/02/12/changing-the-framework-disability-justice

Moradi, B., & Grzanka, P. R. (2017). Using intersectionality responsibly: Toward critical epistemology, structural analysis, and social justice activism. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(5), 500–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000203

Mosher, D. K., Hook, J. N., Captari, L. E., Davis, D. E., DeBlaere, C., & Owen, J. (2017). Cultural humility: A therapeutic framework for engaging diverse clients. Practice Innovations, 2(4), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000055

Mueller, C. O., Forber-Pratt, A. J., & Sriken, J. (2019). Disability: Missing from the conversation of violence. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12339

Öksüz, E., & Brubaker, M. D. (2020). Deconstructing disability training in counseling: A critical examination and call to the profession. Journal of Counselor Leadership and Advocacy, 7(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/2326716X.2020.1820407

Olkin, R. (2002). Could you hold the door for me? Including disability in diversity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.130

Oswald, G. R., Adams, R. D. N., & Hiles, J. A. (2018). Universal design for learning in rehabilitation education: Meeting the needs for equal access to electronic course resources and online learning. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 49(1), 19–22.

Perrin, P. B. (2019). Diversity and social justice in disability: The heart and soul of rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000278

Pierce, K. L. (2024). Bridging the gap between intentions and impact: Understanding disability culture to support disability justice. The Professional Counselor, 13(4), 486–495. https://doi.org/10.15241/klp.13.4.486

Rivas, M. (2020). Disability in counselor education: Perspectives from the United States. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 42, 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-020-09404-y

Shakespeare, T. (2006). The social model of disability. In L. J. Davis (Ed.), The Disability Studies Reader (2nd ed.; pp. 197–204). Routledge. https://disabilitystudies.nl/sites/default/files/beeld/onderwijs/lennard_davis_the_disability_studies_reader_secbookzz-org_0.pdf

Shakespeare, T., & Kleine, I. (2013). Educating health professionals about disability: A review of interventions. Health and Social Care Education, 2(2), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.11120/hsce.2013.00026

Shapiro, J. P. (1994). No pity: People with disabilities forging a new civil rights movement. Three Rivers Press.

Sharif, A., McCall, A. L., & Bolante, K. R. (2022). Should I say “disabled people” or “people with disabilities”? Language preferences of disabled people between identity- and person-first language. ASSETS ’22: Proceedings of the 24th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3517428.3544813

Shin, R. Q., Welch, J. C., Kaya, A. E., Yeung, J. G., Obana, C., Sharma, R., Vernay, C. N., & Yee, S. (2017). The intersectionality framework and identity intersections in the Journal of Counseling Psychology and The Counseling Psychologist: A content analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(5), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000204

Slesaransky-Poe, G., & García, A. M. (2014). The social construction of difference. In D. Lawrence-Brown, M. Shapon-Shevin, & N. Erevelles (Eds.), Condition critical: Key principles for equitable and inclusive education (pp. 66–85). Teachers College, New York.

Smart, J. (2015). Disability, society, and the individual (3rd ed.). ProEd, Inc.

Smith, W. T., Roth, J. J., Okoro, O., Kimberlin, C., & Odedina, F. T. (2011). Disability in cultural competency pharmacy education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 75(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe75226

Taboas, A., Doepke, K., & Zimmerman, C. (2023). Preferences for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism, 27(2), 565–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221130845

Strike, D. L., Skovholt, T. M., & Hummel, T. J. (2004). Mental health professionals’ disability competence: Measuring self-awareness, perceived knowledge, and perceived skills. Rehabilitation Psychology, 49(4), 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.49.4.321

Wolbring, G., & Nasir, L. (2024). Intersectionality of disabled people through a disability studies, ability-based studies, and intersectional pedagogy lens: A survey and a scoping review. Societies, 14(9), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14090176

Wong, A. (Ed.). (2020). Disability visibility: First-person stories from the twenty-first century. Vintage.

Julie C. Hill, PhD, NCC, BC-TMH, LPC, CRC, is an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas. Toni Saia, PhD, CRC, is an associate professor at San Diego State University. Marcus Weathers, Jr., PhD, CRC, LPC-IT, is an assistant professor at Mississippi State University. Correspondence may be addressed to Julie C. Hill, 751 W. Maple St., Fayetteville, AR 72701, jch029@uark.edu.

Sep 13, 2024 | Volume 14 - Issue 2

Sapna B. Chopra, Rebekah Smart, Yuying Tsong, Olga L. Mejía, Eric W. Price

This mixed methods program evaluation study was designed to assist faculty in better understanding students’ multicultural and social justice training experiences, with the goal of improving program curriculum and instruction. It also offers a model for counselor educators to assess student experiences and to make changes that center social justice. A total of 139 first-semester students and advanced practicum students responded to an online survey. The Consensual Qualitative Research-Modified (CQR-M) method was used to analyze brief written narratives. The Multicultural Counseling Competence and Training Survey (MCCTS) and the Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment Survey (ACSA) were used to triangulate the qualitative data. Qualitative findings revealed student growth in awareness, knowledge, skills, and action, particularly for advanced students, with many students reporting a desire for more social justice instruction. Some students of color reported microaggressions and concerns that training centers White students. Quantitative analyses generally supported the qualitative findings and showed advanced students reporting higher multicultural and advocacy competencies compared to beginning students. Implications for counselor education are discussed.

Keywords: social justice, program evaluation, training, multicultural counseling, counselor education

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the long-standing inequities it brought to light, many universities began examining the ways that injustice unfolds within their institutions (Mull, 2020). Arredondo et al. (2020) noted that counseling and counselor education continue to uphold white supremacy and center the experiences of White people within theories, training, and research. White supremacy culture promotes Whiteness as the norm and standard, intersects with and reinforces other forms of oppression, and shows up in institutions in both overt and covert ways, such as emphasis on individualism, avoidance of conflict, and prioritizing White comfort (Okun, 2021). Arredondo et al. (2020) called for counselor educators to engage in social justice advocacy and to unpack covert White supremacy in training programs. The present study investigated the multicultural and social justice training experiences of students in a Western United States counseling program so that counseling faculty can be empowered to uncover biases and better integrate social justice in the curriculum.

Counselor education programs are products of the larger sociopolitical environment and dominant patriarchal, cis-heteronormative, Eurocentric culture that often fails to “challenge the hegemonic views that marginalize groups of people” which “perpetuate deficit-based ideologies” (Goodman et al., 2015, p. 148). For example, the focus on the individual in traditional counseling theories can reinforce oppression by failing to address the role of systemic oppression in a client’s distress (Singh et al., 2020). Counseling theory textbooks usually provide an ancillary section at the end of each chapter focusing on multicultural issues (Cross & Reinhardt, 2017). White supremacy culture is so ubiquitous that it is typically invisible to those immersed within it (DiAngelo, 2018). It is not surprising then that counseling is often viewed as a White, middle-class endeavor, and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) clients frequently perceive that they should leave their cultural identities and experiences outside the counseling session (Turner, 2018). Counselor educators have been encouraged to reflect on how Eurocentric curricula and pedagogy may marginalize students and seek liberatory teaching practices that promote critical consciousness (Sharma & Hipolito-Delgado, 2021).

Students’ Perceptions of Their Growth, Learning Process, and Critiques of Their Training

Studies of mostly White graduate students show gains in expanding awareness of their own biases and privilege, knowledge about other cultures and experiences of oppression, as well as the importance of empowering and advocating for clients (Beer et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2015; Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019; Singh et al., 2010). Others indicated the benefits of integrating feminist principles in treatment (Hoover & Morrow, 2016; Singh et al., 2010). Consciousness-raising and self-reflection were key parts of multicultural and social justice learning (Collins et al., 2015; Hoover & Morrow, 2016), and could be emotionally challenging. Indeed, Goodman et al. (2018) identified a theme of internal grappling reflecting students’ experiences of intellectual and emotional struggle; others noted students’ experiences of overwhelm and isolation (Singh et al., 2010), as well as resistance, such as withdrawing or dismissing information that challenged their existing belief system (Seward, 2019). Researchers have also documented student complaints about their social justice training; for example, that social justice is not well integrated or that there was inadequate coverage of skills and action (Collins et al., 2015). Kozan and Blustein (2018) found that even among programs that espouse social justice, there was a lack of training in macro level advocacy skills. Barriers to engaging in advocacy included: lack of time (Field et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2010), emotional exhaustion stemming from observations of the harms caused by systemic inequities (Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019), and ill-informed supervisors (Sanabria & DeLorenzi, 2019).

The studies reviewed thus relied on samples of mainly White, cisgender, heterosexual women. Some noted that education on social justice is often centered on helping White students expand their awareness (Haskins & Singh, 2015). In one study focused on challenges faced by students of color, participants expressed frustration with the lack of diversity among their professors, classmates, and curriculum (Seward, 2019). Participants also experienced marginalization and disconnection when professors and students made offensive or culturally uninformed comments and when course content focused on teaching students with privileged identities. Students from marginalized communities also face isolation in academic settings and sometimes question the multicultural competence of their professors (Haskins & Singh, 2015), which in turn contributes to the underrepresentation of students of color in counseling and psychology (Arney et al., 2019).

The Present Study

Counselor educators must critically examine their curriculum, course materials, and overall learning climate for students (Haskins & Singh, 2015). Listening to students’ experiences and perceptions of their training offers faculty an opportunity to model cultural humility, gain useful feedback, and make necessary changes. Given the increased recognition of racial trauma and societal inequities, it is critical that counseling programs engage with students of diverse backgrounds as they seek to shift their pedagogy. Historically, academic institutions have responded to student demands with performative action rather than meaningful change (Zetzer, 2021). This mixed methods study is part of a larger process of counseling faculty working to invite student feedback and question internalized assumptions and biases in order to implement real change. The goal of program evaluation is to investigate strengths and weaknesses in order to improve the program (Royse et al., 2010). According to the 2024 Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) standards, program evaluation is essential to assess and improve the program (CACREP, 2023). Thus, the purpose of this program evaluation study was to understand students’ self-assessment and experiences with the counseling program’s curriculum in the area of multicultural and social justice advocacy, with the overarching goal of program curriculum and instruction improvement. This article offers counselor educators a model of how to assess program effectiveness in multicultural and social justice teaching and practical suggestions based on the findings. The research questions were: What are beginning and advanced students’ self-perceptions regarding their multicultural and social justice advocacy competencies? What are beginning and advanced students’ perceptions of the multicultural and social justice advocacy competencies training they are receiving in their program?

Method

We employed a mixed method, embedded design in which the quantitative data offered a supportive and secondary role to the qualitative results (Creswell et al., 2003). Qualitative and mixed methods research designs are particularly useful in program evaluation (Royse et al., 2010). Mixed method approaches also offer value in research that centers social justice advocacy, as the integration of diverse methodological techniques within a single study fosters the understanding of multiple perspectives and facilitates a deeper comprehension of intricate issues (Ponterotto et al., 2013). We used an online survey to collect written narratives (qualitative) and survey data (quantitative) from two counseling courses: a beginning counseling course in the first semester (beginning students), and an advanced practicum course, taken by those who had completed at least part of their year-long practicum (advanced students).

Participants

Participants were counseling students enrolled in a CACREP-accredited program at a large West Coast public university in the United States that is both a federally designated Hispanic-serving institution and an Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander–serving institution. Responses were collected from two courses, which included 94 beginning students (84% response rate) and 62 advanced students (71% response rate). Twelve percent of the advanced practicum students also completed the survey when they were first-semester (beginning) students. The mean age of the 139 participants was 27.7 (SD = 7.11), ranging from 20 to 58 years. Racial identifications were 40.3% White, 33.1% Latinx, 14.4% Asian, 7.2% Biracial or Multiracial, 2.9% Black, 0.7% Middle Eastern, 0.7% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 0.7% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The majority identified as women (82.0%), followed by 14.4% as men, and 2.9% as nonbinary/queer. Students self-identified as heterosexual (71.2%), bisexual (11.5%), lesbian/gay (6.5%), queer (4.3%), pansexual (1.4%), and about 1% each as asexual, heteroflexible, and unsure. About 19.4% of students were enrolled in a bilingual/bicultural (Spanish/Latinx) emphasis within the program.

Procedure

After receiving university IRB approval, graduate students enrolled in the first-semester beginning counseling course (fall 2018 and 2019) or the advanced practicum course (summer 2019 and 2020) were asked to complete an online survey through Qualtrics with both quantitative measures and open-ended questions as part of their preparation for class discussion. Students were informed that this homework would not be graded and was not intended to “test” their knowledge but rather would serve as an opportunity to reflect on their experience of the program’s multicultural and social justice training. Students were also given the option to participate in the current study by giving permission for their answers to be used. Those who consented were asked to continue to complete the demographic questionnaire. In accordance with the American Counseling Association Code of Ethics (2014), students were informed that there would be no repercussions for not participating. A faculty member outside the counseling program managed the collection of and access to the raw data in order to protect the identities of the students and ensure that their participation or lack of participation in the study could not affect their grade for the course or standing in the program. All students, regardless of participation status, were given the option to enter an opportunity drawing for a small cash prize ($20 for data collection in 2018 and 2019, $25 for 2020) through a separate link not connected to their survey responses.

Data Collection

We collected brief written qualitative data and responses to two quantitative measures from both beginning and advanced students.

Qualitative Data

The faculty developed open-ended questions that would elicit student feedback on their multicultural and social justice training. Prior to beginning the counseling program, first-semester students were asked two questions about their experiences and impressions: How would you describe your knowledge about and interest in multiculturalism/diversity and social justice from a personal and/or academic perspective? and How would you describe your initial impressions or experience of the focus on multicultural and social justice in the program so far? They were also asked, if it was relevant, to include their experience in the Latinx counseling emphasis program component. Advanced students, who were seeing clients, were asked the same questions and also asked to: Consider/describe how this experience of multiculturalism and social justice in the program may impact you personally and professionally (particularly in work with clients) in the future.

Quantitative Data

Two instruments were selected to quantitatively assess students’ perceptions of their own multicultural and advocacy competencies. The Multicultural Counseling Competence and Training Survey (MCCTS; Holcomb-McCoy & Myers, 1999) is designed to assess counselors’ perceptions of their multicultural competence and the effectiveness of their training. The survey contains 32 statements for which participants answer on a 4-point Likert scale (not competent, somewhat competent, competent, extremely competent). Sample items include: “I can discuss family therapy from a cultural/ethnic perspective” and “I am able to discuss how my culture has influenced the way I think.” The reliability coefficients for each of the five components of the MCCTS ranged from .66 to .92: Multicultural Knowledge (.92), Multicultural Awareness (.92), Definitions of Terms (.79), Knowledge of Racial Identity Development Theories (.66), and Multicultural Skills (.91; Holcomb-McCoy & Myers, 1999). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .75 to .96.

The Advocacy Competencies Self-Assessment Survey (ACSA; Ratts & Ford, 2010) assesses for competency and effectiveness across six domains: (a) client/student empowerment, (b) community collaboration, (c) public information, (d) client/student advocacy, (e) systems advocacy, and (f) social/political advocacy. It contains 30 statements that ask participants to respond with “almost always,” “sometimes,” or “almost never.” Sample questions include “I help clients identify external barriers that affect their development” and “I lobby legislators and policy makers to create social change.” Although Ratts and Ford (2010) did not provide psychometrics of the original ACSA, it was validated with mental health counselors (Bvunzawabaya, 2012), suggesting an adequate internal consistency for the overall measure, but not the specific domains. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .69 to.79 for the six domains, and .94 for the overall scale. For the purposes of this study, we were not interested in specific domains and used the overall scale to assess students’ overall social justice/advocacy competencies.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Data Analysis

To analyze the qualitative data, we used Consensual Qualitative Research-Modified (CQR-M; Spangler et al., 2012), which was based on Hill et al.’s (2005) CQR but modified for larger numbers of participants with briefer responses. In contrast to the in-depth analysis of a small number of interviews, CQR-M was ideal for our data, which consisted of brief written responses from 139 participants. CQR-M involves a consensus process rather than interrater reliability among judges, who discuss and code the narratives, and relies on a bottom-up approach, in which categories

(i.e., themes) are derived directly from the data rather than using a pre-existing thematic structure. Frequencies (i.e., how many participants were represented in each category) are then calculated. We analyzed the beginning and advanced students’ responses separately, as the questions were adjusted for their time spent in the program.

After immersing themselves in the data, the first two authors, Sapna B. Chopra and Rebekah Smart, met to outline a preliminary coding structure, then met repeatedly to revise the coding into more abstract categories and subcategories. The computer program NVivo was used to organize the coding process and determine frequencies. After all data were coded, the fifth author, Eric W. Price, served as auditor and provided feedback on the overall coding structure. Both the consensus process and use of an auditor are helpful in countering biases and preconceptions. Brief quantitative data, as used in this study, can be used effectively as a means of triangulation (Spangler et al., 2012).

Quantitative Data Analysis

To examine for significant differences in the self-perceptions of multicultural competencies and advocacy competencies between White and BIPOC students as well as between beginning and advanced students, a two-way (2×2) ANOVA was conducted with the overall MCCT as the criterion variable and student levels (beginning, advanced) and race (White, BIPOC) as the two independent variables. In addition, two (5×2) multivariate analyses of variances (MANOVAs) were conducted with the five factors of multicultural competencies (knowledge, awareness, definition of terms, racial identity, and skills) as criterion variables and with student levels (beginning, advanced) and student races (White, BIPOC) as independent variables in each analysis. Data for beginning and advanced students were analyzed separately to assess whether time in the counseling program helped to expand their interest and commitment to social justice.

Research Team

We were intentional in examining our own social identities and potential biases throughout the research process. Chopra is a second-generation South Asian American, heterosexual, cisgender woman. Smart is a White European American, heterosexual, cisgender woman. Yuying Tsong identifies as a genderqueer first-generation Taiwanese and Chinese American immigrant. Olga L. Mejía is an Indigenous-identified Mexican immigrant, bisexual, cisgender woman. Price is a White, gay, cisgender male. All have experience as counselor educators and in qualitative research methods, and all have been actively engaged in decolonizing their syllabi and incorporating multicultural and social justice into their pedagogy.

Results

The research process was guided by the overarching question: What are beginning and advanced counseling students’ perceptions of their multicultural and social justice competencies and training and how can their feedback be used to improve their counselor education program? We explore the qualitative findings first, as the primary data for the study, followed by the quantitative data.

Qualitative Findings for Beginning Counseling Students

Two higher-order categories emerged from the beginning students’ narratives: developing competencies and learning process so far.

Developing Competencies

Students’ descriptions of the competencies they were developing included themes of awareness, knowledge, and skills and action. Some students entered the program with an already heightened awareness, while others were making new discoveries. Awareness included subthemes of humility (24.5%), awareness of own privilege (6.4%), and awareness of bias (3.2%). “There’s a lot to learn” was a typical sentiment, particularly from White students. One White female student wrote: “I definitely need more and I believe that open discussions, even hard ones would be some of the best ways to go about this.” A large group expressed knowledge of oppression and systemic inequities (33%); a smaller group referenced intersectionality (3.2%). Within skills and action, some students expressed specific intentions in allyship (11.7%); a number of students expressed commitment to social action but felt unsure how to engage in social justice (11.7%).

Learning Process So Far

Central themes in this category were support for growth, concerns in training, and internal challenges. Some students felt excited and supported, while some were cautiously optimistic or concerned. Support for growth was a strong theme that reflected excited and enthusiastic to learn (22.3%); appreciation for the Latinx emphasis (18.1%); and receiving support from professors and program (17.0%). For example, one Mexican student in the Latinx emphasis who noted that mental health was rarely discussed in her family shared: “For me to see that there is a program that teaches students how to communicate to individuals who are unsure of what counseling is about, gave me a sense of happiness and relief.”

A few students were adopting a wait-and-see attitude and expressed some concerns about their training. Although the percentage for these subthemes is low, they provide an important experience that we want to amplify. This theme had multiple subthemes. The subtheme concerns from students of color included centering White students (3.2%), microaggressions (3.2%), and lack of representation (1.1%). A student who identified as a Mexican immigrant shared experiences of microaggressions, including classmates using a hurtful derogatory phrase referring to immigrants with no comment from the professor until the student raised the issue. Concerns in training also included the subtheme concerns with how material is presented in classes (7.0%). For some, the concern related to the potential for harm in classes in which White and BIPOC students were encouraged to process issues of privilege and oppression. For example, one Asian Pacific Islander student wrote that although they appreciated the emphasis on social justice, “Time always runs out and I believe it’s careless and dangerous to cut off these types of conversations in a rushed manner.” A small minority seemed to suggest a backlash to the emphasis on social justice, stating that the content was presented in ways that were too “politically correct,” “biased,” or “repetitive.”

Multiple subthemes emerged from the theme of internal challenges. Both BIPOC and White students shared feeling afraid to speak up (5.3%). BIPOC students expressed struggling with confidence or wanting to avoid conflict, while White students’ fear of speaking up was also connected to discomfort and uncertainty as a White person (2.1%). A small minority of White students did not express explicit discomfort but seemed to engage in a color-blind strategy, as indicated in the theme of people are people (2.1%): “I find people are people, regardless of any differences, and love hearing the good and bad about everybody’s experiences.” Some students of color expressed limited knowledge about cultures other than one’s own (4.3%). For example, an Asian American student stated that they had gravitated to “those who were most similar to me” growing up. Lastly, a few students shared feeling overwhelmed and exhausted (3.2%).

Qualitative Findings for Advanced Counseling Students

Four higher-order themes emerged: competencies in process, multiculturalism and diversity in the program, social justice in the program, and the learning process.

Competencies in Process

Similar to beginning students, advanced students described growing self-awareness, knowledge and awareness of others, skills, and action. Their disclosures often related to clinical work, now that they had been seeing clients. Self-awareness included strong subthemes of: humility and desire to keep learning (25.8%); increased open-mindedness, acceptance of others, and compassion (22.6%); awareness of personal privilege and oppression (17.7%); awareness of personal bias and value systems (17.7%); and awareness of personal cultural identity (14.5%). One Mexican American student wrote: “I have also gained an increased awareness of how my prejudices can impact my work with clients and learned about how to check-in with myself.”

Knowledge and awareness of others had subthemes of privilege and oppression (19.4%) and increased knowledge of culture (14.5%), with awareness of the potential impact on clients. The advanced students also had more to say about skills, which included subthemes of diversity considerations in conceptualization (29%), and in treatment (12.9%), and cultural conversations in the therapy room (21%). One White student wrote: “I have been able to have difficult conversations that once were unheard of. I have also been able to bring culture, ethnicity, and oppression into the room so that my clients can feel understood and safe.” Within the theme of action, 52% wrote about their commitment to social justice and intention to advocate. Although this strongest subtheme suggested action was still more aspirational than currently enacted, a smaller group also wrote about the experiences that they have already had with client advocacy (12.9%), community and/or political action (12.9%), and unspecified action (11.3%).

Multiculturalism and Diversity in the Program

Many students (44%) indicated that they appreciated that multicultural issues were integrated or addressed well within the program. However, with more time spent in the program, 26% felt that there was more nuance, depth, or scope needed. Some wanted more attention to specific issues, such as disability, gender identity, and religion/spirituality. One Asian American student wrote that the focus had been “basic and surface-level,” adding “I feel like it has also generally catered to the protection of White feelings and voices, which is inherently complicit in the system of White supremacy, especially in higher ed.” Others (9.7%) said more training in clinical application was needed.

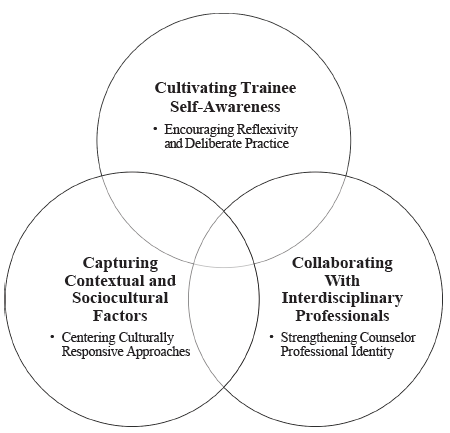

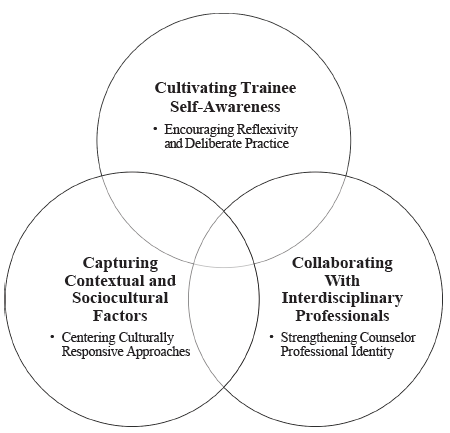

Social Justice in the Program